Abstract

Background

While of predominant abundance across vertebrate genomes and significant biological implications, the relevance of short tandem repeats (STRs) (also known as microsatellites) to speciation remains largely elusive and attributed to random coincidence for the most part. Here we collected data on the whole-genome abundance of mono-, di-, and trinucleotide STRs in nine species, encompassing rodents and primates, including rat, mouse, olive baboon, gelada, macaque, gorilla, chimpanzee, bonobo, and human. The collected data were used to analyze hierarchical clustering of the STR abundances in the selected species.

Results

We found massive differential STR abundances between the rodent and primate orders. In addition, while numerous STRs had random abundance across the nine selected species, the global abundance conformed to three consistent < clusters>, as follows: <rat, mouse>, <gelada, macaque, olive baboon>, and <gorilla, chimpanzee, bonobo, human>, which coincided with the phylogenetic distances of the selected species (p < 4E-05). Exceptionally, in the trinucleotide STR compartment, human was significantly distant from all other species.

Conclusion

Based on hierarchical clustering, we propose that the global abundance of STRs is non-random in rodents and primates, and probably had a determining impact on the speciation of the two orders. We also propose the STRs and STR lengths, which predominantly conformed to the phylogeny of the selected species, exemplified by (t)10, (ct)6, and (taa4). Phylogenetic and experimental platforms are warranted to further examine the observed patterns and the biological mechanisms associated with those STRs.

Keywords: Global, Short tandem repeat, Abundance, Non-random, Rodent, Primate, Hierarchical clustering

Introduction

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. Several models and theories have been proposed for this highly complicated process, including gene regulatory networks, community ecology, and mating preferences (for a review see [1]). Natural selection may be considered a major outcome associated with, and linking the above propositions. With an exceptionally high degree of polymorphism and plasticity, short tandem repeats (STRs) (also known as microsatellites/simple sequence repeats) may be a spectacular source of variation required for speciation and evolution [2–6]. The impact of STRs on speciation is supported by their various functional implications in gene expression, alternative splicing, and translation [4, 7–13].

STRs are a source of rapid and continuous morphological evolution[14], for example, in the evolution of facial length in mammals[15]. These highly evolving genetic elements may also be ideal responsive elements to fluctuating selective pressures. A role in evolutionary selection and adaptation is consistent with deep evolutionary conservation of some STRs, as “tuning knobs”, including several in genes with neurological and neurodevelopmental function[16].

While a limited number of studies indicate that purifying selection and drift can shape the structure of STRs at the inter- and intra-species levels [17–22], the global abundance of STRs at the crossroads of speciation remains largely unknown.

Mononucleotide and dinucleotide STRs are the most common categories of STRs in the vertebrate genomes[23, 24]. In addition to their association with frameshifts in coding sequences and pathological [25] and possibly evolutionary consequences, recent evidence indicates surprising functions for the mononucleotide STRs, such as their proposed role in translation initiation site selection[12, 26]. Several groups have found evidence on the involvement of a number of dinucleotide STRs in gene regulation, speciation, and evolution[4, 23, 27–30]. Trinucleotide STRs are frequently linked to human neurological disorders, most of which are specific to this species[31, 32].

Here, we analyzed the global hierarchical clustering of all types of mono-, di-, and trinucleotide STRs in nine mammalian species, encompassing primates and rodents, Those species belong to the superordinal group of Euarchontoglires [33], and form three distinct and unambiguous phylogenetic < clusters>. The aim of this analysis was to examine whether the global abundance of STRs in the selected species conforms to the phylogenetic < clusters > of the selected species, or not.

Materials and methods

Species and whole-genome sequences

The UCSC genome browser (https://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu) was used to download and analyze the latest genome assemblies of nine species as follows (genome sizes are indicated following each species): rat (Rattus norvegicus): 2,647,915,728, mouse (Mus musculus): 2,728,222,451, gelada (Theropithecus gelada): 2,889,630,685, olive baboon (Papio anubis): 2,869,821,163, macaque (Macaca mulatta): 2,946,843,737, gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla): 3,063,362,754, chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes): 3,050,398,082, bonobo (Pan paniscus): 3,203,531,224, and human (Homo sapiens): 3,099,706,404. Those species encompassed rodents: rat and mouse, Old World monkeys: gelada, olive baboon, macaque, and great apes: gorilla, bonobo, chimpanzee, human.

Extraction of STRs from genomic sequences

The whole-genome abundance of mononucleotide STRs of ≥ 10-repeats, dinucleotide STRs of ≥ 6-repeats, and trinucleotide STRs of ≥ 4-repeats were studied in the nine selected species. To that end, we designed a software package in Java (https://github.com/arabfard/Java_STR_Finder). All possibilities of mononucleotide motifs, consisting of A, C, T, and G, all possibilities of dinucleotide motifs, consisting of AC, AG, AT, CA, CG, CT, GA, GC, GT, TA, TC, and TG, and all possibilities of trinucleotide motifs, consisting of AAC, AAT, AAG, ACA, ACC, ACT, ACG, ATA, ATC, ATT, ATG, AGA, AGC, AGT, AGG, CAA, CAC, CAT, CAG, CCA, CCT, CCG, CTA, CTC, CTT, CTG, CGA, CGC, CGT, CGG, TAA, TAC, TAT, TAG, TCA, TCC, TCT, TCG, TTA, TTC, TTG, TGA, TGC, TGT, TGG, GAA, GAC, GAT, GAG, GCA, GCC, GCT, GCG, GTA, GTC, GTT, GTG, GGA, GGC, and GGT were analyzed.

The written program calculated based on perfect (pure) STRs. The algorithm started from an initial point, which was the first nucleotide of each genome, and iteratively repeated a series of steps during walking on the genome, nucleotide by nucleotide. In the first step, it investigated a window frame of 2*N, where 2 was the definition of tandem repeats i.e., two identical continuous sequences, and N was the length of the STR core. If the first half of the sequence inside the window was not equal to the second half, the algorithm moved one nucleotide forward. If equal, the algorithm checked the nucleotides, and this process continued until all identical continuous nucleotides, which were the same as the core were found. The final selected sequence- M*N- was introduced as a new STR, which had a core with a length of N and M repeats. All steps were repeated to find new STRs from the end of the previous STR. We repeated the algorithm for different values of N (N was between 1 and 3 in each genome to detected mono, di, and trinucleotide STRs).

Whole-genome STR data aggregation, abundance, and hierarchical cluster analysis across species

Whole-genome chromosome-by-chromosome data were aggregated and analyzed in the nine species. STR abundances across the selected species were obtained and depicted by boxplot diagrams and hierarchical clustering, using boxplot and hclust packages[34] in R, respectively. Boxplots illustrate abundance differences among segments across the selected species, and hierarchical clustering plots demonstrate the level of similarity and differences across the obtained abundances. The input data to these packages were numerical arrays . Each array consisted of a number of columns, each column corresponding to the STR abundance in different chromosomes. It should be noted that the focus of our analysis was to evaluate the global abundance of STRs across those species, regardless of the homologous regions.

Statistical analysis

The STR abundances across the nine selected species were compared by repeated measurements analysis, using one and two-way ANOVA tests. These analyses were confirmed by nonparametric tests.

Results

Global abundance of mono, di, and trinucleotide STRs coincides with the phylogenetic distance of the nine selected species

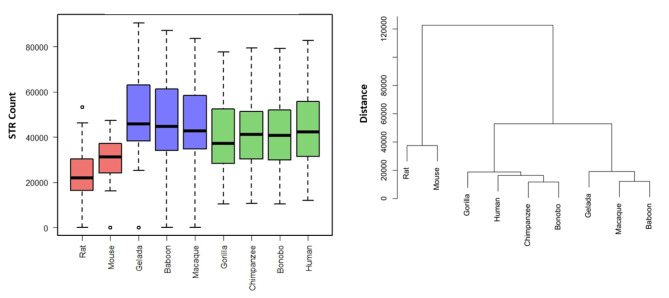

Whole-genome data was collected on the abundance of mononucleotide STRs across the nine species (Table 1). We found massive expansion of the mononucleotide STR compartment in all primate species versus rat and mouse. Hierarchical clustering yielded three < clusters > as follows: <rat, mouse>, <gelada, olive baboon, macaque>, and < gorilla, chimpanzee, bonobo, human>, which coincided with the phylogenetic distance of the nine selected species (P = 6.3E-09) (Fig. 1) namely < rodents>, <Old World monkeys>, and < great apes>.

Table 1.

Mononucleotide STR abundance across the nine selected species

| Chromosome/Species | Rat | Mouse | Gelada | Baboon | Macaque | Gorilla | Chimpanzee | Bonobo | Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53,318 | 47,294 | 90,549 | 87,241 | 83,595 | 77,718 | 79,390 | 79,173 | 82,820 |

| 2(A) | 46,221 | 45,636 | 71,588 | 67,963 | 64,609 | 35,908 | 35,897 | 34,400 | 78,550 |

| 2(B) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40,245 | 39,968 | 39,837 | 0 |

| 3 | 36,364 | 38,493 | 70,736 | 68,688 | 65,836 | 62,398 | 62,713 | 64,472 | 64,027 |

| 4 | 34,818 | 39,019 | 62,831 | 60,726 | 57,817 | 54,896 | 54,855 | 53,287 | 56,495 |

| 5 | 36,532 | 38,805 | 66,164 | 64,101 | 61,533 | 60,436 | 48,944 | 54,142 | 56,538 |

| 6 | 28,617 | 35,751 | 63,104 | 61,642 | 59,150 | 53,872 | 53,769 | 53,420 | 55,185 |

| 7(A) | 29,411 | 33,649 | 25,699 | 65,267 | 63,438 | 50,898 | 53,882 | 50,792 | 56,257 |

| 7(B) | 0 | 0 | 42,663 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 27,353 | 31,938 | 50,576 | 48,446 | 46,757 | 43,593 | 44,212 | 43,618 | 45,220 |

| 9 | 23,532 | 31,142 | 50,050 | 47,879 | 46,910 | 36,797 | 38,035 | 37,493 | 41,744 |

| 10 | 31,065 | 34,138 | 41,475 | 39,012 | 37,477 | 44,166 | 44,562 | 44,416 | 46,075 |

| 11 | 17,071 | 33,869 | 54,287 | 54,284 | 51,654 | 37,218 | 41,059 | 40,757 | 42,217 |

| 12 | 15,101 | 29,325 | 42,675 | 35,365 | 42,793 | 46,865 | 47,576 | 47,481 | 48,483 |

| 13 | 21,673 | 29,496 | 40,602 | 39,101 | 38,022 | 27,902 | 28,481 | 28,479 | 29,430 |

| 14 | 21,835 | 28,835 | 45,820 | 44,693 | 42,677 | 30,311 | 30,659 | 30,595 | 31,460 |

| 15 | 20,351 | 25,753 | 43,334 | 41,671 | 40,009 | 28,611 | 29,752 | 29,049 | 31,402 |

| 16 | 15,958 | 24,139 | 41,211 | 39,781 | 37,693 | 29,268 | 31,121 | 28,460 | 34,364 |

| 17 | 18,458 | 24,234 | 32,308 | 31,285 | 30,378 | 29,884 | 36,791 | 37,010 | 38,947 |

| 18 | 16,651 | 22,580 | 25,310 | 24,850 | 23,551 | 22,556 | 22,428 | 22,236 | 23,130 |

| 19 | 14,266 | 16,221 | 35,819 | 32,702 | 30,470 | 23,832 | 31,405 | 30,614 | 32,423 |

| 20 | 14,475 | 0 | 34,962 | 32,965 | 32,095 | 20,654 | 22,106 | 31,034 | 21,961 |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,462 | 10,633 | 10,467 | 12,050 |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13,778 | 14,816 | 13,904 | 16,014 |

| X | 25,983 | 40,547 | 52,836 | 49,013 | 47,590 | 43,138 | 43,302 | 41,656 | 46,178 |

| Sum | 549,053 | 650,864 | 1,084,599 | 1,036,675 | 1,004,054 | 925,406 | 946,356 | 946,792 | 990,970 |

Fig. 1.

Whole-genome mononucleotide STR abundance in the nine selected species. Global incremented pattern was observed in the primate species versus rodents (left graph). The overall hierarchical clustering yielded three <clusters>, which conformed to <rodents>, <Old World monkeys>, and <great apes> (right graph).

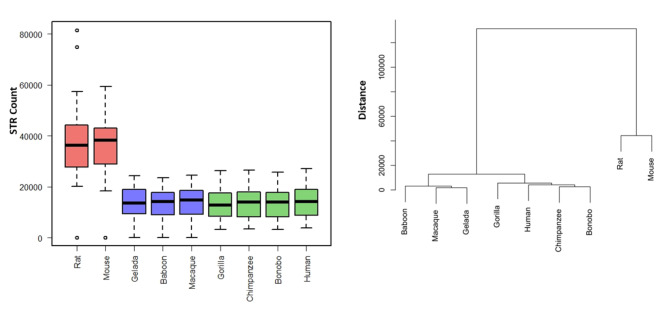

The whole-genome STR abundances from aggregated chromosome-by-chromosome analysis in the dinucleotide category (Table 2) was decremented in primates versus rodents. Similar to the mononucleotide STR compartment, the dinucleotide STR compartment conformed to the genetic distance among the three < clusters > of species (P = 7.1E-08) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Dinucleotide STR abundance across the nine selected species

| Chromosome/Species | Rat | Mouse | Gelada | Baboon | Macaque | Gorilla | Chimpanzee | Bonobo | Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 81,509 | 59,425 | 24,335 | 23,427 | 24,462 | 23,105 | 23,708 | 23,583 | 24,657 |

| 2(A) | 74,837 | 53,096 | 21,315 | 20,302 | 21,225 | 11,820 | 11,960 | 11,391 | 26,989 |

| 2(B) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,494 | 14,555 | 14,334 | 0 |

| 3 | 53,642 | 45,464 | 20,710 | 19,973 | 20,552 | 20,939 | 21,179 | 21,039 | 21,633 |

| 4 | 57,299 | 44,963 | 19,364 | 18,592 | 19,038 | 21,536 | 21,182 | 20,503 | 21,773 |

| 5 | 52,269 | 48,069 | 22,020 | 21,275 | 22,147 | 17,099 | 17,831 | 19,606 | 20,385 |

| 6 | 44,993 | 45,325 | 19,921 | 19,397 | 20,070 | 18,575 | 18,391 | 18,196 | 18,995 |

| 7(A) | 43,219 | 40,052 | 5832 | 16,963 | 17,870 | 15,988 | 16,727 | 16,130 | 17,275 |

| 7(B) | 0 | 0 | 11,934 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 43,242 | 41,103 | 15,903 | 15,390 | 16,164 | 15,837 | 15,875 | 15,718 | 16,245 |

| 9 | 37,463 | 39,005 | 14,733 | 14,183 | 14,857 | 11,704 | 11,935 | 11,661 | 13,080 |

| 10 | 40,260 | 40,998 | 10,136 | 9432 | 9855 | 14,051 | 14,306 | 14,032 | 14,799 |

| 11 | 27,685 | 38,212 | 14,360 | 14,487 | 15,187 | 12,678 | 13,988 | 13,842 | 14,189 |

| 12 | 22,084 | 35,361 | 13,478 | 14,325 | 14,685 | 14,385 | 14,559 | 14,588 | 14,757 |

| 13 | 38,331 | 35,159 | 11,839 | 11,292 | 11,797 | 11,071 | 11,258 | 11,135 | 11,406 |

| 14 | 31,923 | 36,644 | 13,605 | 13,243 | 13,885 | 9549 | 9465 | 9386 | 9798 |

| 15 | 31,768 | 30,662 | 12,078 | 11,661 | 12,014 | 8014 | 8226 | 8143 | 8607 |

| 16 | 28,704 | 29,521 | 8228 | 8064 | 8206 | 7814 | 8268 | 7553 | 8947 |

| 17 | 30,312 | 28,209 | 11,002 | 10,457 | 10,942 | 10,456 | 8056 | 8006 | 8355 |

| 18 | 27,797 | 27,263 | 8548 | 8349 | 8591 | 8629 | 8597 | 8497 | 8750 |

| 19 | 21,794 | 18,350 | 5994 | 5493 | 5395 | 4774 | 6081 | 5865 | 6220 |

| 20 | 20,191 | 0 | 8334 | 7902 | 8345 | 6379 | 7106 | 6623 | 6612 |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4092 | 4154 | 4123 | 4884 |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3209 | 3442 | 3183 | 3746 |

| X | 36,246 | 38,470 | 18,303 | 16,787 | 17,659 | 17,922 | 18,193 | 17,078 | 18,952 |

| Sum | 845,568 | 775,351 | 311,972 | 300,994 | 312,946 | 304,120 | 309,042 | 304,215 | 321,054 |

Fig. 2.

Whole-genome dinucleotide STR abundance in the nine selected species. Global decremented patterns were observed in all primate species versus mouse and rat (left gragh). The global pattern conformed to the three <clusters> across the nine species and their phylogenetic distance (right graph)

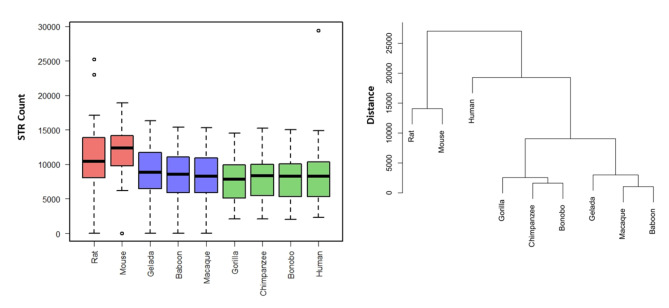

There was global shrinkage of the trinucleotide STR compartment in primates versus rodents (P = 3.8E-05) (Table 3; Fig. 3). Remarkably, human stood out among all other species in the trinucleotide STR compartment.

Table 3.

Trinucleotide STR abundance across the nine selected species

| Chromosome/Species | Rat | Mouse | Gelada | Baboon | Macaque | Gorilla | Chimpanzee | Bonobo | Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25,234 | 18,913 | 16,307 | 15,350 | 15,341 | 14,540 | 15,219 | 15,054 | 14,882 |

| 2(A) | 22,996 | 17,856 | 13,005 | 12,341 | 11,998 | 6800 | 6842 | 6537 | 14,521 |

| 2(B) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7545 | 7764 | 7822 | 0 |

| 3 | 16,869 | 15,022 | 12,749 | 12,518 | 11,938 | 11,473 | 11,744 | 11,637 | 11,631 |

| 4 | 17,088 | 15,204 | 11,921 | 11,154 | 10,960 | 11,116 | 11,228 | 10,685 | 11,144 |

| 5 | 16,339 | 15,469 | 13,001 | 12,514 | 12,112 | 10,581 | 9665 | 10,640 | 10,649 |

| 6 | 13,495 | 14,332 | 12,150 | 11,743 | 11,380 | 10,364 | 10,504 | 10,445 | 29,430 |

| 7(A) | 14,317 | 13,760 | 3937 | 10,991 | 10,871 | 9342 | 10,117 | 9744 | 9995 |

| 7(B) | 0 | 0 | 7552 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 12,701 | 13,518 | 10,032 | 9524 | 9682 | 8752 | 9096 | 8645 | 8890 |

| 9 | 11,646 | 12,378 | 9295 | 8755 | 8659 | 6898 | 7328 | 7157 | 7580 |

| 10 | 12,552 | 13,968 | 7297 | 6728 | 6786 | 8096 | 8350 | 8245 | 8295 |

| 11 | 7987 | 13,232 | 9615 | 9578 | 9403 | 7801 | 8668 | 8458 | 8352 |

| 12 | 6060 | 11,817 | 7742 | 8297 | 8029 | 8905 | 9218 | 9051 | 9127 |

| 13 | 10,852 | 11,634 | 7266 | 6823 | 6860 | 5273 | 5479 | 5452 | 5391 |

| 14 | 10,325 | 11,865 | 8869 | 8583 | 8253 | 5473 | 5771 | 5785 | 5706 |

| 15 | 10,075 | 10,693 | 7727 | 7339 | 7152 | 4869 | 5168 | 5082 | 5297 |

| 16 | 8476 | 9527 | 6228 | 5837 | 5801 | 5738 | 6007 | 5623 | 6402 |

| 17 | 9502 | 10,045 | 5908 | 5737 | 5684 | 5666 | 5859 | 5914 | 6091 |

| 18 | 8124 | 9154 | 4738 | 4645 | 4603 | 4722 | 4625 | 4584 | 4566 |

| 19 | 6984 | 6190 | 5432 | 4643 | 4664 | 3807 | 5438 | 5230 | 5101 |

| 20 | 6445 | 0 | 6655 | 6016 | 5945 | 4072 | 4472 | 4155 | 4130 |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2051 | 2092 | 2028 | 2304 |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2721 | 2825 | 2601 | 2915 |

| X | 10,411 | 13,783 | 11,449 | 10,609 | 10,666 | 9547 | 9838 | 9140 | 10,062 |

| Sum | 258,478 | 258,360 | 198,875 | 189,725 | 186,787 | 176,152 | 183,317 | 179,714 | 202,461 |

Fig. 3.

Whole-genome trinucleotide STR abundance in the nine selected species. While global decremented patterns were observed in primates versus rodents (left graph), human stood out in this category, in comparison to all other species (right graph)

Differential abundance patterns of various STRs and STR lengths across rodents and primates

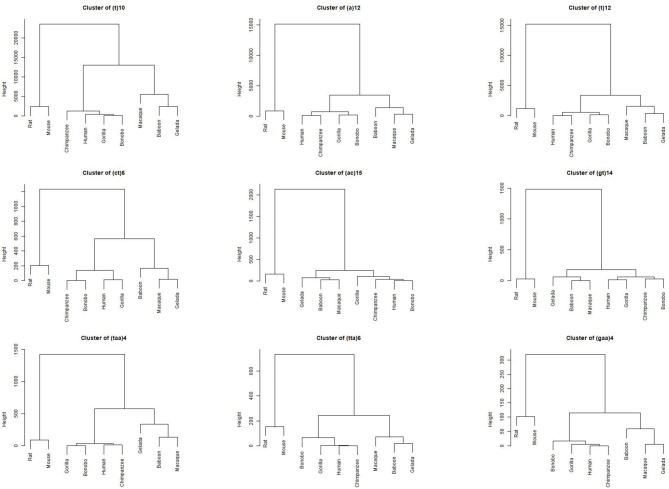

Numerous STRs and STR lengths across the mono, di, and trinucleotide STR categories conformed to the phylogenetic distances of the nine selected species, for example, in the instance of T/A mononucleotides of 10, 11, and 12 repeats, which were the most abundant STRs across all nine species (Fig. 4). In another example, (ct)6 and (taa)4 conformed to the phylogeny of the studied species in the di and trinucleotide STR categories, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Example of STRs and STR lengths, abundance of which coincided with the phylogeny of the nine selected species. Three STRs are depicted as examples for each of mono, di, and trinucleotide categories. Data from all studied STRs are available at: https://figshare.com/articles/figure/STR_Clustering/17054972

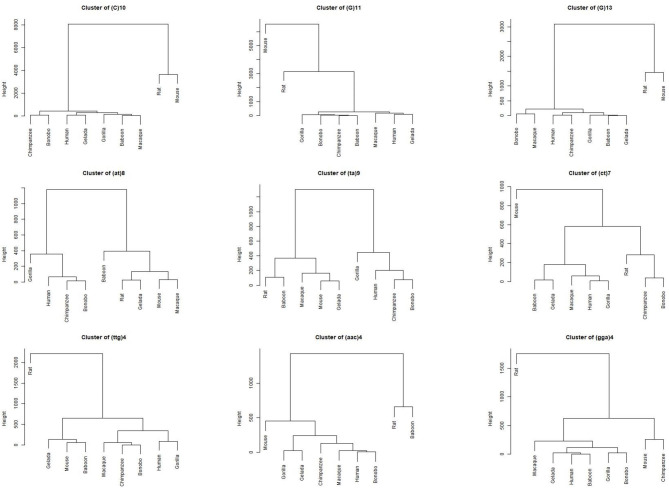

On the other hand, numerous STRs did not follow perfect phylogenetic patterns, such as (C)10, (at)8, and (ttg)4 (Fig. 5). Hierarchical clusters of all studied STRs across the three categories are available at: https://figshare.com/articles/figure/STR_Clustering/17054972.

Fig. 5.

Example of STRs and STR lengths, abundance of which appeared to be predominantly random across the nine selected species. Three STRs are depicted as examples for each of mono, di, and trinucleotide categories. Data from all studied STRs are available at: https://figshare.com/articles/figure/STR_Clustering/17054972

Discussion

While the mechanisms underlying speciation are extremely complicated and largely based on theories and models, the impact of genetics seems to be significant in respect of adaptation, gene flow, and natural selection. In fact, natural selection may be a central converging point of the evolutionary propositions for speciation. However, the various mechanisms involved in speciation have different impact on natural selection, and it is the net effect which may ultimately result in the emergence of a new species.

As one of the most abundant genetic elements in various animal genomes, it is largely unknown whether at the crossroads of speciation, STRs evolved as a result of purifying selection, genetic drift, and/or in a directional manner.

Here, we selected multiple species across rodents and primates, and investigated the clustering patterns of all possible types and lengths of mononucleotides, dinucleotide, and trinucleotide STRs on the whole-genome scale in those species. Hierarchical clustering yielded clusters that predominantly conformed to the phylogenetic distances of the selected species. Hierarchical clustering is an unsupervised clustering method that is used to group data. This algorithm is unsupervised because it uses random, unlabeled datasets. As the number of clusters increases, the accuracy of the hierarchical clustering algorithm improves.

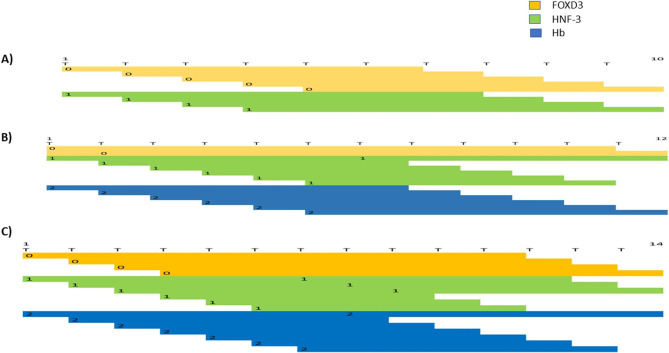

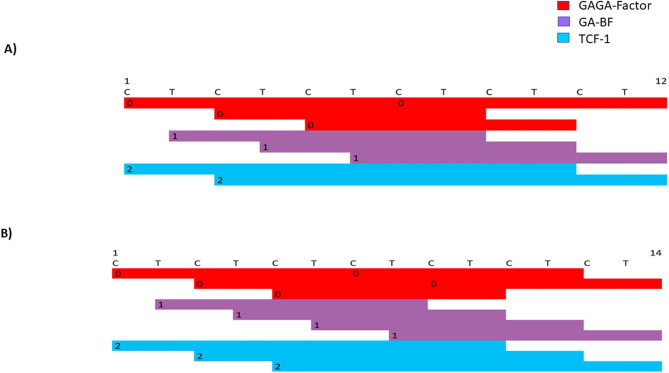

Our findings may be of significance in a number of aspects. Firstly, there were significant differential abundances separating rodents from primates, for example, massive decremented abundance of dinucleotide and trinucleotide STRs in primates versus the rodent species, and massive incremented abundance of mononucleotide STRs in primates versus rodents. Secondly, the three major < clusters > obtained from global hierarchical cluster analysis matched the phylogeny of the three < clusters > of species, i.e., <rodents>, <Old World monkeys>, and < great apes>. It is possible that there are mathematical channels/thresholds required for the abundance of STRs in various orders. This is in line with the hypothesis that STRs function as scaffolds for biological computers[35]. In addition, our data indicate that various STRs and STR lengths behave differently with respect to their colossal abundance. Not all the studied STRs conformed to the phylogenetic distances of the nine selected species. We hypothesize that those which did, had a link with the speciation of those species, whereas those which did not, apparently followed random patterns for the most part. The potential effect of STRs in non-genic regions is largely unknown. However, when located at genic regions, various STRs and repeat lengths can potentially recruit transcription factors (TFs), which differ in qualitative and quantitative terms (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3) [36]. Those various TF sets may differentially regulate expression of the relevant genes during the process of evolution. For example, T-blocks of 10, 12, and 14-repeats recruit various combinations of FOXD3, HNF-3, and Hb (Fig. 6). Interestingly, (T)10 and (T)12 were among the mononucleotide STRs, which conformed to the phylogenetic distance of the nine species (Fig. 4), and (t)14 did not (https://figshare.com/articles/figure/STR_Clustering/17054972). The concept of various TF sets stands for other STRs as well. For example, (ct)6 conforms to the phylogenetic clusters, and recruits a number of TFs, whereas (ct)7, which does not conform to those clusters, recruits quantitatively different set of those TFs (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Potential recruitment of qualitatively and quantitatively different TFs to various lengths of (T)-repeats. (T)10 (A) and (T)12 (B) conformed to the phylogenetic < clusters>, whereas (T)14 (C) did not. Differential recruitment of TFs may differentially regulate the relevant genes in evolutionary processes

Fig. 7.

Potential differential TF recruitments to various lengths of (ct)6 A) and (ct)7 B). Those two lengths result in alternative quantitative binding of three TFs. (ct)6 conformed and (ct)7 did not conform to the phylogenetic < clusters>

Mononucleotide STRs impact various processes, such as gene expression, translation alterations, and frameshifts of various proteins, which may have evolutionary and pathological consequences[12, 25]. They can overlap with G4 structures, many of which associate with evolutionary consequences[37].

In a number of instances, dinucleotide STRs located in the protein-coding gene core promoters have been subject to contraction in the process of human and non-human primate evolution[38]. A number of those STRs are identical in formula in primates versus non-primates, and the genes linked to those STRs are involved in characteristics that have diverged primates from other mammals, such as craniofacial development, neurogenesis, and spine morphogenesis. Structural variants are enriched near genes that diverged in expression across great apes[39], and genes with STRs in their regulatory regions are more divergent in expression than genes with fixed or no STRs[40]. STR variants are likely to have epistatic interactions, which can have significant consequences in complex traits, in human as well as model organisms[6, 41].

Trinucleotide STRs are predominantly focused on in human because of their link with several neurological disorders[42–45]. We found an exceptional global hierarchical distance between human and all other species in that compartment. In view of the fact that most of the phenotypes attributed to trinucleotide STRs are human-specific in nature, it is conceivable that their evolution is also significantly distant from all other species studied.

The observed abundances were independent of the genome sizes of the selected species. For example in the instances of di- and trinucleotide STRs, we observed higher abundances in rodents versus primates despite the smaller genome sizes of the former. These findings are in line with the previous reports of lack of relationship between genome size and abundance of STRs[46, 47].

It should be noted that this is a pilot study based on hierarchical clustering, and future studies are warranted to further examine our hypothesis, using phylogenetic platforms and additional orders and species. Functional studies are also warranted to examine the biological impact of the relevant STRs.

Conclusion

We propose that the global abundance of STRs is non-random across rodents and primates. We also propose the STRs and STR lengths, which predominantly conformed to the phylogenetic distances of those species, such as (t)10, (ct)6, and (taa4). Additional species encompassing other orders and phylogenetic platforms are warranted to further examine this proposition.

Limitations

This research was a pilot study based on hierarchical clustering of the collected data in a number of mammalian species. Phylogenetic platforms and additional orders of species are warranted to further examine our hypothesis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- STR

Short tandem repeat

- TF

Transcription factor

Authors’ contributions

MA performed and coordinated the bioinformatics analyses. MS performed the biostatistics analysis. YHN, IA, and AMAM contributed to data collection. KK contributed to coordination. MO conceived and supervised the project, and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Raw data are available at: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Trends/15073329 and https://figshare.com/articles/figure/STR_Clustering/17054972.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gavrilets S. Models of speciation: where are we now? J Hered. 2014;105(S1):743–55. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esu045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohammadparast S, Bayat H, Biglarian A, Ohadi M. Exceptional expansion and conservation of a CT-repeat complex in the core promoter of PAXBP1 in primates. Am J Primatol. 2014;76(8):747–56. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushehri A, Barez MRM, Mansouri SK, Biglarian A, Ohadi M. Genome-wide identification of human-and primate-specific core promoter short tandem repeats. Gene. 2016;587(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikkhah M, Rezazadeh M, Khorshid HRK, Biglarian A, Ohadi M. An exceptionally long CA-repeat in the core promoter of SCGB2B2 links with the evolution of apes and Old World monkeys. Gene. 2016;576(1):109–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinar WB, Lalun VO, Reitan T, Jakobsen KS, Butenko MA. Length variation in short tandem repeats affects gene expression in natural populations of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2021;33(7):2221–34. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Press MO, Carlson KD, Queitsch C. The overdue promise of short tandem repeat variation for heritability. Trends Genet. 2014;30(11):504–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakubosky D, D’Antonio M, Bonder MJ, Smail C, Donovan MKR, Greenwald WWY, Matsui H, D’Antonio-Chronowska A, Stegle O, Smith EN. Properties of structural variants and short tandem repeats associated with gene expression and complex traits. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16482-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valipour E, Kowsari A, Bayat H, Banan M, Kazeminasab S, Mohammadparast S, Ohadi M. Polymorphic core promoter GA-repeats alter gene expression of the early embryonic developmental genes. Gene. 2013;531(2):175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranathunge C, Wheeler GL, Chimahusky ME, Perkins AD, Pramod S, Welch ME. Transcribed microsatellite allele lengths are often correlated with gene expression in natural sunflower populations. Molecular Ecology 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Press MO, Hall AN, Morton EA, Queitsch C. Substitutions are boring: Some arguments about parallel mutations and high mutation rates. Trends Genet. 2019;35(4):253–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fotsing SF, Margoliash J, Wang C, Saini S, Yanicky R, Shleizer-Burko S, Goren A, Gymrek M. The impact of short tandem repeat variation on gene expression. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1652–9. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0521-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arabfard M, Kavousi K, Delbari A, Ohadi M. Link between short tandem repeats and translation initiation site selection. Hum Genomics. 2018;12(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s40246-018-0181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap K, Mukhina S, Zhang G, Tan JSC, Ong HS, Makeyev EV. A short tandem repeat-enriched RNA assembles a nuclear compartment to control alternative splicing and promote cell survival. Mol Cell. 2018;72(3):525–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fondon JW, Garner HR: Molecular origins of rapid and continuous morphological evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101(52):18058–18063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wren JD, Forgacs E, Fondon Iii JW, Pertsemlidis A, Cheng SY, Gallardo T, Williams RS, Shohet RV, Minna JD, Garner HR. Repeat polymorphisms within gene regions: phenotypic and evolutionary implications. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(2):345–56. doi: 10.1086/303013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King DG. Evolution of simple sequence repeats as mutable sites. Tandem Repeat Polymorphisms 2012:10–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Srivastava S, Avvaru AK, Sowpati DT, Mishra RK. Patterns of microsatellite distribution across eukaryotic genomes. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5516-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlova A, Gan HM, Lee YP, Austin CM, Gilligan DM, Lintermans M, Sunnucks P. Purifying selection and genetic drift shaped Pleistocene evolution of the mitochondrial genome in an endangered Australian freshwater fish. Heredity. 2017;118(5):466–76. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2016.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorde PE, Søvik G, Westgaard JI, Albretsen J, André C, Hvingel C, Johansen T, Sandvik AD, Kingsley M, Jørstad KE. Genetically distinct populations of northern shrimp, Pandalus borealis, in the North Atlantic: adaptation to different temperatures as an isolation factor. Mol Ecol. 2015;24(8):1742–57. doi: 10.1111/mec.13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legrand D, Chenel T, Campagne C, Lachaise D, Cariou ML. Inter-island divergence within Drosophila mauritiana, a species of the D. simulans complex: Past history and/or speciation in progress? Mol Ecol. 2011;20(13):2787–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun G, McGarvey ST, Bayoumi R, Mulligan CJ, Barrantes R, Raskin S, Zhong Y, Akey J, Chakraborty R, Deka R. Global genetic variation at nine short tandem repeat loci and implications on forensic genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11(1):39–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abe H, Gemmell NJ. Evolutionary footprints of short tandem repeats in avian promoters. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep19421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W: Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Fan H, Chu J-Y. A brief review of short tandem repeat mutation. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2007;5(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mo HY, Lee JH, Kim MS, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Frameshift Mutations and Loss of Expression of CLCA4 Gene are Frequent in Colorectal Cancers With Microsatellite Instability. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphology. 2020;28(7):489. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maddi AMA, Kavousi K, Arabfard M, Ohadi H, Ohadi M. Tandem repeats ubiquitously flank and contribute to translation initiation sites. BMC Genomic Data. 2022;23(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12863-022-01075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corney BPA, Widnall CL, Rees DJ, Davies JS, Crunelli V, Carter DA. Regulatory architecture of the neuronal Cacng2/Tarpγ2 gene promoter: multiple repressive domains, a polymorphic regulatory short tandem repeat, and bidirectional organization with co-regulated lncRNAs. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;67(2):282–94. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1208-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emamalizadeh B, Movafagh A, Darvish H, Kazeminasab S, Andarva M, Namdar-Aligoodarzi P, Ohadi M. The human RIT2 core promoter short tandem repeat predominant allele is species-specific in length: a selective advantage for human evolution? Mol Genet Genomics. 2017;292(3):611–7. doi: 10.1007/s00438-017-1294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haasl RJ, Johnson RC, Payseur BA. The effects of microsatellite selection on linked sequence diversity. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6(7):1843–61. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yim J-J, Adams AA, Kim JH, Holland SM. Evolution of an intronic microsatellite polymorphism in Toll-like receptor 2 among primates. Immunogenetics. 2006;58(9):740–5. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Annear DJ, Vandeweyer G, Elinck E, Sanchis-Juan A, French CE, Raymond L, Kooy RF. Abundancy of polymorphic CGG repeats in the human genome suggest a broad involvement in neurological disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82050-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang H, Kirkness EF, Lippert C, Biggs WH, Fabani M, Guzman E, Ramakrishnan S, Lavrenko V, Kakaradov B, Hou C. Profiling of short-tandem-repeat disease alleles in 12,632 human whole genomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(5):700–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar V, Hallström BM, Janke A. Coalescent-based genome analyses resolve the early branches of the euarchontoglires. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murtagh F, Legendre P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? J Classif. 2014;31(3):274–95. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbert A: Simple Repeats as Building Blocks for Genetic Computers. Trends in Genetics 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Farré D, Roset R, Huerta M, Adsuara JE, Roselló L, Albà MM, Messeguer X. Identification of patterns in biological sequences at the ALGGEN server: PROMO and MALGEN. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3651–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawaya S, Bagshaw A, Buschiazzo E, Kumar P, Chowdhury S, Black MA, Gemmell N. Microsatellite tandem repeats are abundant in human promoters and are associated with regulatory elements. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e54710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohadi M, Valipour E, Ghadimi-Haddadan S, Namdar‐Aligoodarzi P, Bagheri A, Kowsari A, Rezazadeh M, Darvish H, Kazeminasab S. Core promoter short tandem repeats as evolutionary switch codes for primate speciation. Am J Primatol. 2015;77(1):34–43. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kronenberg ZN, Fiddes IT, Gordon D, Murali S, Cantsilieris S, Meyerson OS, Underwood JG, Nelson BJ, Chaisson MJP, Dougherty ML. High-resolution comparative analysis of great ape genomes. Science 2018, 360(6393). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Sonay TB, Carvalho T, Robinson MD, Greminger MP, Krützen M, Comas D, Highnam G, Mittelman D, Sharp A, Marques-Bonet T. Tandem repeat variation in human and great ape populations and its impact on gene expression divergence. Genome Res. 2015;25(11):1591–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.190868.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bagshaw ATM, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Gemmell NJ, Kennedy MA. Microsatellite polymorphisms associated with human behavioural and psychological phenotypes including a gene-environment interaction. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0374-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundblom J, Niemelä V, Ghazarian M, Strand A-S, Bergdahl IA, Jansson J-H, Söderberg S, Stattin E-L. High frequency of intermediary alleles in the HTT gene in Northern Sweden-The Swedish Huntingtin Alleles and Phenotype (SHAPE) study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66643-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker EK, Arpone M, Kraan C, Bui M, Rogers C, Field M, Bretherton L, Ling L, Ure A, Cohen J. FMR1 mRNA from full mutation alleles is associated with ABC-C FX scores in males with fragile X syndrome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68465-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou X, Wang C, Ding D, Chen Z, Peng Y, Peng H, Hou X, Wang P, Ye W, Li T. Analysis of (CAG) n expansion in ATXN1, ATXN2 and ATXN3 in Chinese patients with multiple system atrophy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Q, Yang M, Sørensen KK, Madsen CS, Boesen JT, An Y, Peng SH, Wei Y, Wang Q, Jensen KJ. A brain-targeting lipidated peptide for neutralizing RNA-mediated toxicity in Polyglutamine Diseases. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11695-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neff BD, Gross MR. Microsatellite evolution in vertebrates: inference from AC dinucleotide repeats. Evolution. 2001;55(9):1717–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park JY, An Y-R, An C-M, Kang J-H, Kim EM, Kim H, Cho S, Kim J. Evolutionary constraints over microsatellite abundance in larger mammals as a potential mechanism against carcinogenic burden. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/srep25246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data are available at: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Trends/15073329 and https://figshare.com/articles/figure/STR_Clustering/17054972.