Abstract

Anti-asthmatic medication makes the oral habitat susceptible to opportunistic infections like Candida, causing oral candidiasis. This study aimed to estimate salivary Candida Albicans in asthmatic patients taking anti-asthmatics medication. A prospective study was performed at the Oral Pathology and Microbiology Department of S.B. Patil Dental College and Hospital, Bidar, Karnataka, India, between June 2018 to November 2018. The research comprised a total of 100 individuals, 50 of whom were asthmatics, and 50 healthy controls who were age and sex-matched to the asthmatics. Saliva was collected for 5–10 minutes in a sterile container, and samples were transferred to the laboratory in cold chain conditions. Serial dilution was prepared for the saliva samples, and 50:1 standard dilution was inoculated on SAD (Sabouraud Dextrose Agar) culture media by lawn culture method. Some part of the culture plate was inoculated with Candida organisms. 32 people had candida growth, and 18 individuals did not have any candidal development at all. 18 people were in the 400 CFU/ml group, and 32 individuals were in the 401 CFU/ml group, respectively. It was 0.000 in the 400 colony forming unit/milliliter group, and 27200 in the 401 CFU/ml group, with 0.00 being the median. There was a notable difference between study and control groups in terms of colony forming unit per milliliter (P=0.000). The growth of Candida in asthmatics patients is very high compared to healthy people. Anti-asthmatic medication makes the oral habitat prone to attack from opportunistic infections like oral candidiasis.

Keywords: asthma, anti-asthmatic medication, Candida albicans, Sabouraud Dextrose Agar

INTRODUCTION

Asthma has grown as a significant public health issue in recent years, impacting more than 339 million people all over the world, as per World Health Organization [1]. Over the past decade, the prevalence of pediatric chronic illnesses has increased exponentially in developing countries like India, Africa, and Brazil, making it one of the most prevalent chronic diseases among children, adults and the elderly [2]. Every systemic illness that affects children, particularly during their formative years, has broad consequences [3]. Most of the research has discovered a link between anti-asthmatic medication and the negative impact on oral hygiene, causing decreased salivary flow, xerostomia, difficulty in mastication, dry mucosa, decreased salivary enzymes (IgA, lactoferrin, salivary amylase and lysozyme) resulting in increased dental caries, periodontal damage, in both children and adults with asthma [4]. Dental caries continue to be the powerful cause of tooth erosion in every age group, exacerbating the debilitating effects on both function and appearance [5].

Medications for short-term asthma relief include bronchodilators, anticholinergic drugs and systemic corticosteroids, and long-term control medication includes anti-inflammatory agents, long-acting bronchodilators, leukotriene modifiers and anticholinergic drugs [6]. These medications are mostly administered via inhalation, which may be accomplished using different inhalers or nebulizers [7]. A drug used in these forms will have its effect for a prolonged period, making the oral cavity more inclined to the mucosal insult from these compounds [8]. As in asthma, these medicines, which suppress the immune system and deliver the medicine directly, bring undesirable changes in oral bioflora and support the development of opportunistic infections like Candida [9]. Candida may grow to unusually high levels in these individuals by the following mechanism:

Neutrophils which are the first line of defense, normally kill about 40% of candida growth. However, in asthmatic patients, this activity is diminished along with the reduction in the myeloperoxidase hydrogen halide system due to the immune suppression of the corticosteroids in anti-asthmatic medicines. Other mechanisms of defense diminished are macrophage leukocytes interferon-gamma [10]. These medications significantly reduce local immunity and thus promote the pathogenicity of oral candidiasis. In most of these investigations, the levels of Candida infection were shown to be inversely linked to the flow of saliva [11, 12].

Therefore, assessing Candida albicans (C. Albicans) count in response to disease and treatment is very important as this can inform patients about the side effects of medication and emphasize the necessity for oral health care, which will increase the quality of life. This research aimed to evaluate the effect of anti-asthmatic medication on the prevalence of Candida in asthmatics patients. This understanding could enable health workers to educate the patients about the side effects of medications and highlight the requirement for oral health care.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A prospective study was performed in the Oral Pathology and Microbiology Department at S.B. Patil Dental College and Hospital, Bidar, Karnataka, India, from June 2018 to November 2018. Following the patient's informed consent, a thorough medical history was obtained. The research included 100 individuals, 50 of whom were asthmatics and 50 healthy controls who were age and sex-matched to the asthmatics. The mean age of participants was 35.5 years, with 34 females and 16 males participating in each group.

Inclusion criteria: asthmatic individuals taking medicine for 3–5 years, between 20 to 55 years old.

Exclusion criteria: patients with removable prostheses or who have been taking antibiotics for a long time. In addition, patients who were immunocompromised, smokers, or with chronic diseases were also excluded from the study.

Collection of samples and microbiological testing

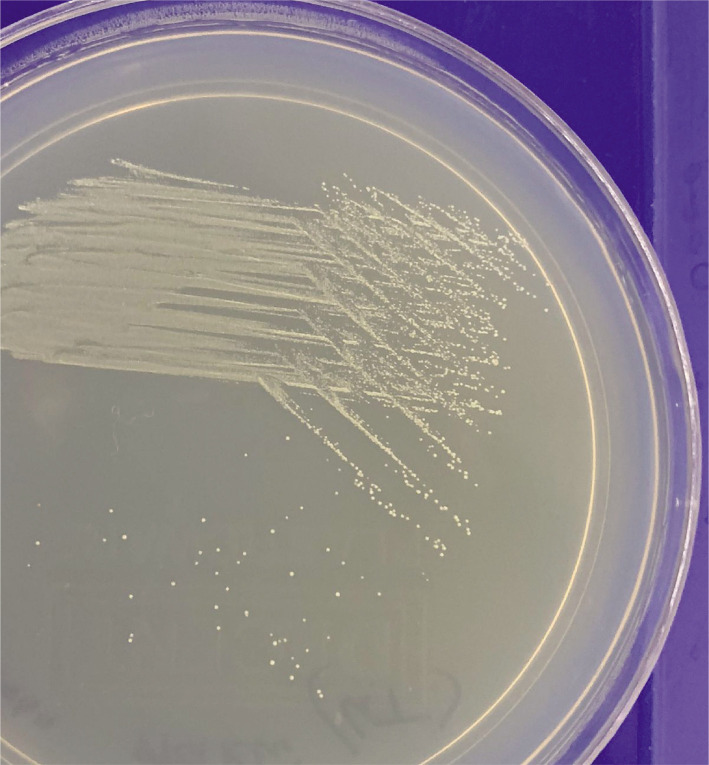

Saliva was collected for 5–10 minutes in a sterile container, and samples were instantly transferred to the laboratory in cold chain conditions. Serial dilution was prepared for the saliva samples, and 50:1 standard dilution was inoculated on SAD (Sabouraud Dextrose Agar) culture media by lawn culture method. Some parts of the culture plate were inoculated with Candida organisms. This plate was incubated at 37.0℃ overnight under an aerobic environment, according to the manufacturer. A morphological examination of Candida colonies was performed after incubation (Figure 1), and a germ tube test was performed to establish the presence of Candida Albicans. Colony counting was carried out with a computerized colony counter. Colony count was calculated as the number of bacteria (CFU) per milliliter or gram of sample by dividing the number of colonies by the dilution factor. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 25.0.

Figure 1.

Parts of the culture plate exhibiting growth of Candida organisms.

RESULTS

Patients with 400 CFU/ml were carriers of Candida, while cases with >400 CFU/ml were considered pathogenic for Candida yeast. Table 1 shows the counts of the salivary Candida albicans in CFU/milliliter. 32 people had candida growth, whereas 18 individuals did not have any candidal development at all. None of the participants in the control group had any signs of candidal development.

Table 1.

The prevalence of C. Albicans in both groups.

| Candida albicans no growth | Candida albicans growth | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 50 | Nil | 50 |

| Cases | 18 | 32 | 50 |

As shown in Table 2, the evaluation of salivary Candida albicans counts in CFU/milliliter differed across the patients. A total of 18 people were in the 400 CFU/ml group, and 32 individuals were in the 401 CFU/ml group, respectively. It was 0.000 in the 400 CFU/ml group, and 27200 in the 401 CFU/ml group, with 0.00 being the median. Table 2 shows a notable difference between study and control group in terms of colony forming unit per milliliter (P=0.000). Table 3 shows a notable difference between both groups regarding colony forming unit per milliliter (P=0.000).

Table 2.

Estimation of C. Albicans in the study group.

| N | Median | Mean rank | U | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤400 CFU/ml | 18 | 0.00 | 7.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ≥400 CFU/ml | 32 | 2700 | 22.69 | - | - |

Table 3.

Comparison of C. Albicans in both groups.

| N | Median | Mean rank | U | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤400 CFU/ml (18) | 0.00 | 7.29 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| ≥401 CFU/ml (32) | 2700 | 22.69 | - | - |

| Cases (50) | 133.0 | 39.55 | 122.0 | 0.00 |

| Control (50) | 0.00 | 20.50 | - | - |

Table 4 shows the relationship between the duration of the illness and the salivary Candida albicans counts in colony forming units per milliliter of saliva. The duration of asthma was split into three groups: three, four, and five years. 19 people (38%) were taking medicine for three years, 19 people (38%) for four years, and 12 people (24%) for five years. There was no statistically significant relationship between duration of illness and colony forming units per milliliter of Candida albicans counts (P=0.07).

Table 4.

Differences between the duration of disease and Candida Albicans (CFU/ml).

| Duration of disease | CFU/ml ≤400/ml (%)=18 | CFU/ml ≥401/ml (%)=32 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 years | 6 (31.58) | 13 (68.42) | 19 (100) |

| 4 years | 5 (26.32) | 14(73.68) | 19 (100) |

| 5 years | 7 (58.33) | 5 (41.67) | 12 (100) |

The relationship between doses of anti-asthmatic medicine and salivary Candida albicans counts was measured in CFU/ml of saliva. In this research, patients were given anti-asthmatic medicine in doses of 100, 250, or 500 mg, depending on their condition (P=0.17). There was no significant relationship between colony forming unit/ml and antihistamine drugs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Differences between doses of antihistamine medication and Candida Albicans (CFU/ml).

| Doses | CFU/ml ≤400/ml (%)=18 | CFU/ml ≥401/ml (%)=32 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 mg | 9 (40.91) | 13 (59.09) | 22 (100) |

| 250 mg | 8 (40) | 12 (60) | 20 (100) |

| 500 mg | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (100) |

Chi-square test, P=0.17.

Table 6 presents the relationship between disease severity and salivary C. Albicans counts in CFU/ml. Patients exhibited mild moderate or severe patterns of the disease. There was no significant association between C. Albicans count CFU/ml and severity of disease.

Table 6.

Differences between severity of disease and C. Albicans.

| Severity of disease | ≤400/ml (%) | ≥401/ml (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | 10 (43.48) | 13 (56.52) | 23 (100) |

| Moderate | 5 (25) | 15 (75) | 20 (100) |

| Severe | 3 (42.86) | 4 (57.14) | 7 (100) |

Chi-square test, P=0.23.

DISCUSSION

The presence of Candida species in healthy adults with normal salivary gland function has been shown in many investigations. According to several studies, up to 40% of individuals with good dental hygiene have positive C. Albicans counts [13].

C. Albicans is a very common infectious organism in asthma patients. Nebulization is the best method for delivering the drugs, and we can compare the colony forming unit per milliliter in adult patients in the same age group in which nebulization was not used [7].

50 people diagnosed with asthma who were taking medication and met the previously stated criteria and 50 healthy matched individuals were included in this study. The CFU/ml of Candida albicans in saliva was determined in the patients and controls using conventional techniques on Saliva Diagnostic Assay. Thirty-two (64%) of the participants had candida growth, whereas 18 (36%) had no candidal development, suggesting that asthmatics on medication had a microfloral change that facilitated candidal growth compared to healthy persons in the study. The colony forming unit was measured in asthmatics patients, and a 1000 medium value was obtained.

A remarkable difference was found between the case and control groups. As a result, among asthmatics with candida growth, there were 32 people with salivary Candida counts of ≥401 CFU/ml (≥401 CFU/ml were considered pathogenic) [14, 15]. All of the results above suggest that the prevalence of Candida albicans among asthmatics who use anti-asthmatic medicines such as corticosteroids and β2 agonists has risen. In addition, asthmatics had a colony forming unit count comparable to that of infective candidiasis, i.e., 401 CFU/ml of saliva, while healthy individuals did not.

It is worth noting that, despite the high CFU counts, which suggest candidal infection, none of the patients presented with symptoms of oral candidiasis throughout the study. This may indicate that the infection was subclinical or microbiotic shift occurred, allowing greater candidal development to occur without causing symptoms. Several comparable studies have been conducted, all of which suggest and corroborate the findings mentioned above that asthmatics who use inhaled anti-asthmatic medication are more susceptible to candida infection, and treatment is necessary to improve the quality of life [16, 17].

This discovery has been interpreted differently, including the interaction between illness, medicine, and the host [18]. Candidal development is facilitated by bronchial asthma, and patients with asthma who have restricted salivary flow are more prone to mouth breathing [19]. Asthmatics who breathe via their mouths for extended periods develop xerostomia and a changed microbial ecology in their oral cavity, which increases the growth of Candida organisms. Inhibition of the host factor by anti-asthmatic medication results in increased candida growth. The control of the asthmatic condition is achieved primarily through medications that fall into two categories: β2-agonists (β2-agonists), which promote bronchial relaxation, and corticosteroids, which suppress the immune system [20].

In contrast to previous studies, the current research found less evidence of candidal carriage in healthy people. Cohen et al. [21] discovered that yeast was present in the oropharynx of healthy participants at a rate of 35%. In their research, Hanan et al. [22] discovered that oral candidiasis occurs at a rate of 30 to 45% in healthy individuals. According to Zaremba et al. [23], who performed a research on the oral carriage of Candida in healthy people, the prevalence rate was 63.1%. Healthy individuals with C. Albicans in their oral cavity were approximately 3–48% of the total population [24]. In addition to geographic differences, the type and size of the sample chosen and the technique of sample collection are factors that should be addressed. Examples of such variables include the sample size, the individual tested, the sampling technique used, and the estimates of Candida species prevalence as human commensals may differ significantly [25, 26].

Regarding asthmatic patients, the researchers looked at the relationship between the length of asthma, the severity of illness, and drug dose. There was no statistically significant relationship between associated factors and the C. Albicans population. Asthmatic patients are more prone to candidal infection, the seriousness of diseases, and drug dosage, and it is viable that medications expand the patient's susceptibility to candida growth.

CONCLUSION

The growth of Candida in asthmatics patients is very high compared to healthy people. Anti-asthmatic medication makes the oral habitat prone to attack from opportunistic infections like Candida causing oral candidiasis. Therefore, assessing C. Albicans count in response to disease and its treatment is mandatory. This understanding enables health workers to draw strategies to educate the patients about the side effects of medication and highlight the requirement for oral health care. More studies with a larger sample size are needed as such research throws light on the preventive measures to be adopted, such as orienting the patients for frequently mouth rinsing, using spacer devices, promoting topical antimycotics (nystatin) application, using sialagogue medication in patients with low salivary rate, chewing sugar-free gums, gargling with amphotericin diluted 1:50 solution, low cariogenic diet and advocating less dosage ICS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the S.B. Patil Dental College and Hospital (SBPCH/2018/150).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Authorship

MA contributed to the concept of the study, review and methodology. AS contributed to the concept of the study, review and methodology. SK contributed to data collection, statistics and results. NS contributed to the concept of the study and the discussion. RF contributed to the discussion section. SMA contributed to the review, results and discussion.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Asthma. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma.

- 2.Bhalla K, Nehra D, Nanda S, Verma R, et al. Prevalence of bronchial asthma and its associated risk factors in school-going adolescents in Tier-III North Indian City. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018 Nov-Dec;7(6):1452–1457. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_117_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher JM, Green JC, Neidell MJ. J Health Econ. 2010 May;29(3):377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakiri H, Bahije L, Fawzi R. The effects of the asthma and its treatments on oral health of children: A case control study. Pediatr Dent Care. 2016;1(4):120. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chellaih P, Sivadas G, Chintu S, Vedam VV, et al. Effect of anti-asthmatic drugs on dental health: A comparative study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016 Oct;8(Suppl 1):S77–S80. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.19197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas MS, Parolia A, Kundabala M, Vikram M. Asthma and oral health: a review. Aust Dent J. 2010 Jun;55(2):128–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budtz-Jorgensen E. Candida-associated denture stomatitis and angular cheilitis. In: Samaramayake LP, MacFarlane TW, editors. Oral candidiasis. Lond on: Butt er worth Publ; 1990. pp. 156–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navazesh M, Wood GJ, Brightman VJ. Relationship between salivary flow rates and Candida albicans counts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995 Sep;80(3):284–8. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bairappan S, Puranik MP, R SK. Impact of asthma and its medication on salivary characteristics and oral health in adolescents: A cross-sectional comparative study. Spec Care Dentist. 2020 May;40(3):227–237. doi: 10.1111/scd.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enilari O, Sinha S. The Global Impact of Asthma in Adult Populations. Ann Glob Health. 2019 Jan 22;85(1):2. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adeloye D, Chan KY, Rudan I, Campbell H. An estimate of asthma prevalence in Africa: a systematic analysis. Croat Med J. 2013 Dec;54(6):519–31. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2013.54.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezende G, Dos Santos NML, Stein C, Hilgert JB, Faustino-Silva DD. Asthma and oral changes in children: Associated factors in a community of southern Brazil. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019 Jul;29(4):456–463. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ArendorfTM Walker DM. The prevalence and intra-oral distribution of Candida albicans in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(80)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein JB, Pearsall NN, Truelove EL. Quantitative relationships between Candida albicans in saliva and the clinical status of human subjects. J Clin Microbiol. 1980 Sep;12(3):475–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.3.475-476.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balan P, B Gogineni S, Kumari NS, Shetty V, et al. Candida Carriage Rate and Growth Characteristics of Saliva in Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Case-Control Study. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2015 Fall;9(4):274–9. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2015.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukushima C, Matsuse H, Tomari S, Obase Y, et al. Oral candidiasis associated with inhaled corticosteroid use: Comparison of fluticasone and beclomethasone. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003 Jun;90(6):646–51. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61870-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullaoglu S, Turktas H, Kokturk N, Tuncer C, et al. Esophageal candidiasis and Candida colonization in asthma patients on inhaled steroids. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007 Sep-Oct;28(5):544–9. doi: 10.2500/aap2007.28.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell H, Gibson PG. Inhaled corticosteroid doses in asthma: An evidence-based approach. Med J Aust. 2003;178(5):223–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima C, Matsuse H, Saeki S, Kawano T, et al. Salivary IgA and oral candidiasis in asthmatic patients treated with inhaled corticosteroid. J Asthma. 2005 Sep;42(7):601–4. doi: 10.1080/02770900500216259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scully C, Kabir M, Samaranayake LP. Candida and oral candidosis: A review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1994;5(2):125–57. doi: 10.1177/10454411940050020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen R, Roth FJ, Delgado E, Ahearn DG, Kalser MH. Fungal flora of the normal human small and large intestine. N Engl J Med. 1969 Mar 20;280(12):638–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196903202801204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Abeid HM, Abu-Elteen KH, Elkarmi AZ, Hamad MA. Isolation and characterization of Candida spp. In Jordanian cancer patients: Prevalence, pathogenic determinants, and antifungal sensitivity. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaremba ML, Daniluk T, Rozkiewicz D, Cylwik-Rokicka D, et al. Incidence rate of Candida species in the oral cavity of middle-aged and elderly subjects. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(Suppl 1):233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samaranayake LP, MacFarlane TW. Hypothesis: On the role of dietary carbohydrates in the pathogenesis of oral candidosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;27:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1985.tb01627.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dignani MC, Solomkin J, Anaisse EJ. Candida Textbook of Clinical Mycology. In: Anaissie EJ Mc, Ginnis MR, Pfaller MA, editors. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. pp. 195–239. Ch. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantheti LP, Reddy B, Ravikumar S, Anuradha CH, et al. Isolation, identification, and carriage of Candida species in PHLAs and their correlation with immunological status in cases with and without HAART. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012 Jan;16(1):38–44. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.92971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]