Abstract

In chemical biology research, various fluorescent probes have been developed and used to visualize target proteins or molecules in living cells and tissues, yet there are limitations to this technology, such as the limited number of colors that can be detected simultaneously. Recently, Raman spectroscopy has been applied in chemical biology to overcome such limitations. Raman spectroscopy detects the molecular vibrations reflecting the structures and chemical conditions of molecules in a sample and was originally used to directly visualize the chemical responses of endogenous molecules. However, our initial research to develop “Raman tags” opens a new avenue for the application of Raman spectroscopy in chemical biology. In this Perspective, we first introduce the label-free Raman imaging of biomolecules, illustrating the biological applications of Raman spectroscopy. Next, we highlight the application of Raman imaging of small molecules using Raman tags for chemical biology research. Finally, we discuss the development and potential of Raman probes, which represent the next-generation probes in chemical biology.

1. Introduction

Advances in genome decoding and genetic engineering technology have led to significant advances in life science research.1,2 However, to understand the complex regulatory mechanism of life, in addition to genes and proteins, a comprehensive understanding of the functions and dynamic transformation of small biomolecules, such as lipids, amino acids, sugars, cofactors, and various other metabolites, is essential. For example, some amino acids and oxidized lipids are known to act as important neurotransmitters and local hormones.3,4 The chemical modification of proteins and nucleic acids also plays an important role in controlling physiological functions.5 In addition to endogenous molecules, exogenous small molecules including natural products, pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and environmental pollutants can also modulate various biological functions by interacting with biomolecules. To better elucidate such chemical events in cells, chemical biological approaches using bioactive small molecules and chemical methods are important. Indeed, in the development of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals, it is necessary to understand diseases at the molecular level as well as the molecular mechanisms of action of the candidate drug.

In life science research, owing to its high sensitivity and excellent spatial resolution, fluorescence imaging is used to determine the localization and dynamics of biomolecules. Fluorescent proteins, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP), have an active role in the detection of specific proteins in live cells or in vivo;6 however, the fusion of a large fluorescent protein may produce artificial results due to the loss of individual protein functions and interactive effects between proteins. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using DNA conjugated with fluorescent dyes has been used to detect specific DNA and RNA,7 and the detection of specific proteins using fluorescently labeled antibodies is also commonly used for imaging tissue and fixed cells. In addition, various chemical probes designed to sense specific molecules including reactive oxygen species (ROS), metal ions such as Ca2+, the physical environment, and enzymatic activity are indispensable tools for chemical biology research. Fluorescent dyes have also been used to help understand the functions of small bioactive molecules. However, fluorescent dyes are large, and their introduction often results in the loss or alteration of biological functions. Photobleaching and low multiplexing levels due to the broad fluorescent spectra are also limitations of fluorescent imaging.8

Recently, vibrational spectroscopy, particularly Raman spectroscopy, has played an important role in motivating new technological developments in chemical biology. Raman spectroscopy utilizes optical effects that directly reflect the structures and chemical conditions of molecules in a sample, allowing the direct visualization of the chemical responses of molecules in living cells and tissues. In addition, Raman spectroscopy can extend the molecular toolkit for chemical biology research because it does not rely on the fluorescence capabilities of molecules. For example, Raman tags, which can be distinguished from endogenous molecules by molecular vibrations, have been used to visualize small molecules in living cells, taking advantage of their smaller size compared to bulky fluorophores. Indeed, the concept of functional labeling in fluorescence imaging has been transferred to Raman microscopy and new imaging techniques, such as drug, metabolic, and super multiplex imaging, which provide information not otherwise available using conventional fluorescence techniques.

Recent developments in Raman imaging technology have stimulated pioneering Raman-based chemical biology. Raman imaging techniques have successfully introduced vibrational spectroscopy into biological and medical research, and chemical biology can also expand its capabilities by utilizing molecular designs for spectroscopic approaches. The key development in Raman imaging techniques is the improvement of imaging speed and detection sensitivity. For example, while the small Raman scattering cross-section has hindered its application in microscopic imaging, advances in laser- and photon-detection technologies have drastically improved imaging speeds; spatial-multiplex detection techniques using line- or multiple-foci illumination allow hyperspectral Raman imaging at speeds a few hundred times faster than conventional confocal Raman microspectrometry based on single-point illumination.9,10 Ultrashort pulse lasers have further facilitated the use of coherent Raman scattering for microscopic imaging, such as coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) and stimulated Raman scattering (SRS).11,12 CARS and SRS can selectively and efficiently excite vibrational states through a stimulated Raman scattering process and can enhance signals by 5 to 6 orders of magnitude compared to spontaneous Raman scattering. These techniques enable the efficient image analysis of biological samples and are highly compatible with conventional optical imaging techniques used in biology and medicine.

In this Perspective, first, recent examples of label-free Raman imaging of cells and tissues are discussed. Next, the imaging of small molecules using small Raman tags are reviewed along with their applications in chemical biology. The development of Raman probes is also discussed, and, finally, future prospects for these technologies are highlighted.

2. Label-Free Raman Imaging and Analysis of Biomaterials

Raman microscopy can detect molecular information at each measurement position of a sample without labeling, and Raman spectra and their component peaks provide information on the molecular structure at the measurement position. In contrast to fluorescence microscopy that can observe specific proteins or nucleic acids using labeling techniques, Raman microscopy recognizes groups of biomolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, without labeling and provides information about molecular components in a sample, which complements conventional imaging techniques. In addition, Raman microscopy benefits from the use of a near-infrared (NIR) laser as the light source (e.g., in coherent Raman microscopy), which allows the observation of intracellular molecules with little influence from autofluorescence in biological samples. Recent advances in the image-acquisition capabilities of Raman microscopy have drastically increased the utility of Raman spectra for analyzing complex biological samples.

2.1. Raman Microscopy

As noted in section 1, Raman microscopy has several imaging modalities that can be used for biological imaging. These imaging methods typically detect spontaneous and coherent Raman scattering to obtain the spatial distribution of the target molecule in the sample. Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of these imaging methods. Spontaneous Raman microscopy, commonly called Raman microscopy, uses a light source at a single wavelength to excite Raman scattering and obtain the molecular vibrations of the sample as a Raman spectrum (Figure 1a and b). While detecting the Raman spectrum with a spectrophotometer, the illumination position is scanned to obtain the Raman scattering distribution in the field of view (Figure 1b), and the Raman image is reconstructed from the obtained data as the intensity distribution of the Raman peak of interest (Figure 1c). Spontaneous Raman imaging can acquire vibrational information on a sample over a wide spectral region (500–3000 cm–1), covering the fingerprint region (500–1800 cm–1) where most biomolecules exhibit vibrations and in the high-wavenumber region (2800–3000 cm–1) where CH2 and CH3 stretching modes are exhibited. Due to the small cross-section of Raman scattering, the exposure time required for imaging is long, limiting its application to imaging biological phenomena without large time variations. To increase image acquisition speed, parallel detection of Raman spectra from many different points in the sample is commonly used.9,10 Raman scattering can be enhanced by a few to several orders of magnitude by resonance with electrical excitation (resonant Raman scattering) or collective oscillation of electrons in metallic nanostructures (surface-enhanced Raman scattering; SERS) as shown in Figure 1a. These techniques are effective in increasing sensitivity and imaging speed when sample conditions are suitable.

Figure 1.

(a) Energy level diagram showing Raman scattering, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), and resonant Raman scattering. E0, E1, and Vn show the electronic ground state, an electronic excited state, and vibrational excited states, respectively. Raman scattering can be enhanced by several orders of magnitude when the excitation energy matches the energy difference between the electronic ground and the excited state. (b) Raman spectrum induced by laser light focused on a sample during Raman microscopy. (c) Spatial distribution of Raman spectra, also referred to as hyperspectral Raman images, where Raman images are obtained as distributions of Raman peak intensities. (d) Energy level diagram of stimulated Raman scattering (SRS), electronic preresonant stimulated Raman scattering (eprSRS), and coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS). (e) SRS microscopy detects the energy exchange between the pump and probe beams via the vibrational excitation state as stimulated Raman gain (probe beam) or loss (pump beam) to reconstruct a Raman image. CARS microscopy uses CARS signals emitted from the sample as the image contrast.

Coherent Raman microscopy uses light at two different frequencies to enhance the Raman signal through stimulated Raman-scattering effects. Coherent Raman microscopy excites vibrational modes corresponding to the difference in frequency between the two lasers, and the excitation efficiency is typically enhanced by a factor of 105 to 106 compared to spontaneous Raman scattering. Coherent Raman scattering microscopy has different imaging modes, such as CARS and SRS, distinguished by how the stimulated vibrational modes are detected (Figure 1d and e). CARS and SRS are similar in their sensitivity but exhibit different characteristics in the generation of the background signal (i.e., nonresonant four-wave mixing for CARS and cross-phase modulation for SRS).11,12 Coherent Raman microscopy is useful for the high-speed imaging of specific vibrational modes, while it requires a laser frequency sweep (or equivalent techniques) to detect the Raman spectrum of the sample. In addition, coherent Raman microscopy has the advantages of a high penetration depth and low excitation of sample autofluorescence, enabling tissue imaging using NIR lasers. To enhance the signal further, electronic preresonance (EPR)—where a pump beam with energy slightly lower than that of electronic excitation is used—is utilized in stimulated Raman scattering. These enhancement techniques are particularly useful when combined with a Raman probe, as described in section 4.2.

2.2. Imaging Intracellular Structures

When imaging biological samples, Raman microscopy can broadly identify molecular species, such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, and their spatial distributions in a sample.13 For example, Figure 2a shows a Raman spectrum obtained from the cytosol of a living HeLa cell irradiated by 532 nm laser.14 The sharp peaks in the spectrum indicate Raman scattering from the different vibrational modes of the molecules in the cells. As shown in Figure 2b, plotting the spatial distribution of the peak intensities can construct Raman images of the cells, which provides information on molecular species at the measurement positions.9,15,16 In particular, the vibrational modes of CH2 and CH3 in the cell provide stronger signals at high wavenumber regions (2800–3000 cm–1), which has been successfully applied to visualize lipid storage,17 lipid phase separation,18 axonal myelin,19 and tissue structures including the liver,20 brain,21 and skin.22 Raman spectra reflect the molecular composition at the measured positions, providing information that can separate the components of a sample, such as organelles and cells in tissues. In addition to Raman peak mapping, multivariate analysis techniques, such as multiple curve resolution23 and independent component analysis,24 can be used to visualize nuclei, lipid droplets, and cell bodies separately, providing morphological information on the sample without labeling.25−28

Figure 2.

(a) A Raman spectrum of cytosol in a living HeLa cell. Adapted with permission from ref (14). Copyright 2013 Elsevier. (b) Raman images reconstructed by plotting the spatial distributions of Raman peak intensities. (c) Time-lapse Raman imaging of vibrational modes in cytochromes, and CH2 and CH3, during the apoptosis of HeLa cells. Adapted with permission from ref (32). Copyright 2012 National Academy of Sciences. (d) Time-lapse observation of osteoblast differentiation. The Raman spectrum and images were obtained by slit-scanning Raman microscopy equipped with a continuous-wave laser oscillating at 532 nm. Adapted with permission from ref (51). Copyright 2015 Nature Publishing Group.

2.3. Resonant Raman Scattering and Redox State Detection

Resonant Raman scattering, which is observed in molecules that absorb incident light, enhances the Raman scattering signal by several orders of magnitude owing to the resonance effect, allowing a more specific visualization of intracellular molecules. Well-known biomolecules that exhibit resonant Raman scattering upon visible light irradiation include heme proteins,29 flavins,30 and carotenoids.31 When used in Raman imaging, porphyrins in heme proteins are useful in cell and tissue imaging with cytochrome, myoglobin, and hemoglobin to clarify the contrast of mitochondria and blood vessels, and to specifically identify those molecules in cells and tissues (Figure 2c).32−34 Furthermore, the sensitivity of resonant Raman scattering to the redox state of hemoproteins allows the label-free detection of cellular and mitochondrial dysfunctions.35,36 This technique has demonstrated the simultaneous observation of the uptake of anticancer drugs and their effect on the oxidation of mitochondrial cytochromes.37 It has been also reported that the deregulation of the electron transport chain of mitochondria in cancer cells can be detected by detecting redox-sensitive Raman bands.38 The oxidized and spin marker band of heme structures in cytochrome P450 has been utilized to visualize enzymatic activity under drug administration in hepatocytes.39 As a tissue diagnostic application, this technique has been used in the evaluation of myocardial infarction, where the resonance Raman scattering of heme protein was used to separate infarcted and noninfarcted tissues.34 Carotenoids also exhibit resonance Raman scattering and provide strong contrast for imaging different cell types and tissues including as biofilm,40 the corpus luteum,41 and the retina.42 As discussed in section 4.2, signal enhancement due to resonance effects has been effectively used in the molecular design of highly sensitive Raman probes.43

2.4. Separating Cell Species and States

Raman spectra can be used to identify cell types because spectral shapes represent the balance of molecular species at each position in a sample. The identification of cancer cells and tissues is one of the valuable applications of this technique, which has been demonstrated for various types of cancers.44 Taking advantage of the label-free approach, intensive studies are underway for intraoperational rapid diagnosis.45,46 Raman microscopy is also expected to describe the dynamic changes in intracellular chemical compositions during cell differentiation or reprogramming, which has been demonstrated using embryonic stem (ES) cells,47,48 induced pluripotent stem (iPS)49,50 cells, and osteoblasts (Figure 2d).51 In these experiments, the gradual changes in the chemical composition during the modulation of cellular states were visualized based on the multivariate analysis of Raman spectra measured at different time points as the cell state changes. Because of the capability of label-free detection of cellular states, Raman microscopy is expected to be an effective technique for the evaluation and quality control of cells for use in regenerative medicine and drug development.52 Similar approaches have also been demonstrated to discriminate cell responses under immune stimulations.53,54

However, although Raman spectra can separate cell states, the biological background detected in Raman measurements is not easily identified. Recently, transcriptome and Raman microscopy have been combined to investigate the correlation between Raman spectra and gene expression in cells,55−57 which paves the way for the use of Raman microscopy as a reliable tool for understanding living systems and the omics-equivalent analysis of live cells and tissues. The combination with flow cytometry is one of the expected implementations of Raman microscopy for biological and medical applications, where cells can be sorted based on their characteristics and functions without labeling, providing various applications using live cells.58−60

3. Raman Imaging Using Small Tags

3.1. Raman Tags

The ability to detect and image biomolecules without labeling is a major advantage of Raman spectroscopy. On the other hand, cells contain many biomolecules and show extremely complicated Raman spectra in which the signals of innumerable molecules overlap. Therefore, identifying the signal of a particular molecule is extremely difficult unless it has a unique Raman signature and is present in a large quantity. This problem can be solved by introducing a small Raman tag into the molecule of interest. For example, the Raman spectrum of the HeLa cell shown in Figure 3a has a window—the so-called silent region (1800–2800 cm–1)—in which no strong signals are derived from endogenous biomolecules. Thus, functional groups with strong signals in this region can be detected and identified as candidates for Raman tags. Among the functional groups with signals in the silent region, deuterium (−C–D stretching vibration), alkyne (−C≡C– stretching vibration), and nitrile (−C≡N stretching vibration) are mainly used as Raman tags because of their chemical stability, bioorthogonality, small size, and synthetic availability (Figure 3b). Deuterium is ideal in terms of the minimum perturbation of bioactivity. Almost all biomolecules have C–H bonds, and the simple replacement of hydrogen with a stable isotope has little effect on its affinity to the target biomolecules.61 However, the Raman signal of C–D stretching vibrations is very weak; therefore, to create an image of the distribution of small molecules, many deuterium atoms must be introduced into the molecule. Currently, the most widely used Raman tags are alkynes because these exhibit sharp and strong signals. Raman imaging based on nitrile signals has also been reported, but examples are rather limited compared to alkynes. B–H and azide (−N3) stretching vibrations can also be used as Raman tags, although only a few examples have been reported. There are many other functional groups whose signals are expected to appear in the cellular silent region, but most of them are highly reactive and incompatible with the biological environment (e.g., ketene, isocyanide, diazonium, carbodiimide, isocyanate, and isothiocyanate). To visualize the uptake and metabolic activity of a specific molecule, various biomolecules with Raman tags have been developed.

Figure 3.

(a) Raman spectrum of a living HeLa cell. Representative signals of biomolecules are indicated. Color bars indicate the general areas of signals of representative Raman tags. (b) Relative Raman intensities of the hexanoic acid derivatives. Raman spectra of deuterated, alkynylated, and azido hexanoic acid mixed with 6-cyanohexanoic acid (1:1 molar ratio). Adapted with permission from ref (92). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

3.1.1. Deuterium-Tag Raman Imaging of Biomolecules

Historically, Raman scattering has been used to study lipids and biological membranes, and deuterated lipids have been used to analyze their conformation and phase separation.62,63 Lipid droplets rich in triglycerides and cholesteryl esters are easily observed in living cells using Raman imaging techniques based on the strong C–H stretching signal of the fatty acid side chains. To visualize uptake and localization of a specific fatty acid, deuterated fatty acids are widely used.64 For example, in 2005, van Manen et al.65 reported a confocal Raman image of neutrophil treated with 5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-octa-deuterated arachidonic acid (AA-d8), in which enrichment of the exogenously added AA-d8 in lipid droplets was clearly observed. Xie et al.66,67 also used their modern CARS and SRS microscopes for imaging of live cells and Caenorhabditis elegans treated with deuterated fatty acids. Deuterated cholesterol and deuterated choline have also been used for visualizing specific components of lipids in live cells.68,69

As the C–D bond is more resistant to cleavage than the C–H bond owing to the kinetic isotope effect, it is likely that the observed metabolism of fully deuterated fatty acids will be converted to its ester forms rather than its oxidized metabolites. Unsaturated fatty acids deuterated at the bis-allylic positions are known to be less susceptible to enzymatic and chemical oxidation.70 Recently, we found that deuterated gamma-linolenic acid (GLA-d4) with deuterium atoms at the bis-allylic position showed selective cytotoxicity to tumor cells, whereas GLA itself is toxic to both normal and tumor cells. This suggests that toxicity to normal cells depends on metabolic and/or chemical reactions at the bis-allylic position, whereas a different mechanism likely exists for tumor cell-selective cytotoxicity. Thus, Raman imaging analysis of all deuterated GLA (GLA-d29)-treated tumor cells and normal cells was performed (Figure 4a), which showed that the tumor cells took up GLA-d29 continuously, even after 48 h, and accumulated in the lipid droplets (Figure 4b). In contrast, in the case of normal cells, uptake and accumulation of GLA-d29 were limited, and as GLA content increased in the lipid droplets, the content of native lipids seemed to be decreased. This suggested that the difference in lipid droplet-related metabolism between tumor and normal cells might be responsible for the tumor-selective cytotoxicity of GLA-d29.71

Figure 4.

(a) Structure of GLA-d29 and a comparison of Raman images of GLA-d29 and lipid droplets in tumor and normal cells treated with 100 μM GLA-d29 for 48 h. The Raman signals at 2115 cm–1 and 3015 cm–1 were assigned to the red and green channels, respectively. (b) Average Raman spectra in the lipid droplet region of five tumor and normal cells treated with 100 μM GLA-d29. Adapted with permission from ref (71). Copyright 2021 Royal Society of Chemistry.

The Raman imaging method is applicable not only to monitor the fate of fatty acids but also other lipid-containing vesicles.72 As a pharmacological application, the uptake and intracellular fate of a liposomal drug carrier composed of 1,2-distearoyl-d70-sn-glysero-3-phosphocholine with or without cell penetrating TAT peptide modification were analyzed by Raman imaging.73

Recently, fully deuterated glucose (Glc-d7) has been used for the assessment of lipogenic activity at the single-cell level. Fully deuterated glucose is metabolized to deuterated acetyl-CoA through the TCA cycle, further converted to fatty acids, and then accumulated in lipid droplets as triglycerides, which can be directly analyzed using Raman imaging.74 Different lipogenesis activities have been observed in different strains of bacteria and mammalian cells, and the technique can be used in antibiotic and anticancer susceptibility tests.75,76 Increased de novo lipogenesis has also been observed in cancer cells. Glu-d7 can be converted into lipids and various other biomolecules, and its conversion to glycogen has been visualized using SRS.77

Deuterated amino acids, such as Phe-d5, Tyr-d4, Leu-d10, Ile-d10, Val-d8, Arg-d7, Lys-d8, and Met-d3, have also been employed to probe protein synthesis in live cells,78,79 tissues, and organisms.80 Metabolic activity phenotyping using a combination of deuterated amino acids and fatty acids has also revealed different metabolic profiles of different cells with or without treatment with various drugs.81 The ultimate method of using deuterium atoms as a Raman tag for metabolic analysis involves the supplementation of heavy water (D2O) to cells, tissues, and organisms. In 2014, Wagner et al.82 demonstrated that the incorporation of deuterium into lipids and other macromolecules from D2O in active microbial cells can be visualized using Raman spectroscopy. In 2018, Min et al.83 expanded this method to mammalian cells, C. elegans, zebrafish, and mice. Thus, advanced Raman spectral analysis enables the selective imaging of newly synthesized lipids, proteins, and DNA. The D2O method has also been applied to study the effects of antimicrobial and anticancer drugs.84,85

3.1.2. Alkyne-Tag Raman Imaging (ATRI) of Biomolecules

Alkynes have been widely used as bioorthogonal tags in chemical biology research in combination with click chemistry (Cu-mediated cycloaddition with azide).86 For imaging, a tiny terminal alkyne (−C≡CH) is introduced into metabolic precursors, such as nucleic acids and amino acids, and the alkyne-modified probe is incubated with cells.87−89 Alkynes are small enough that alkyne-modified molecules are recognized by various metabolic enzymes without any problems and incorporated into DNA, RNA, proteins, and glycans. After fixation of the cells and washing out the excess probe, the newly synthesized DNA/RNA, proteins, and glycans in cells or tissues can be visualized by introducing a fluorophore via a click reaction. However, the click reaction requires toxic copper salts with poor cell permeability, making its application in live cell imaging challenging, and removal of excess fluorescent reagent is essential. Thus, imaging is only available for molecules that are metabolically incorporated into biomacromolecules or form covalent bonds with them.

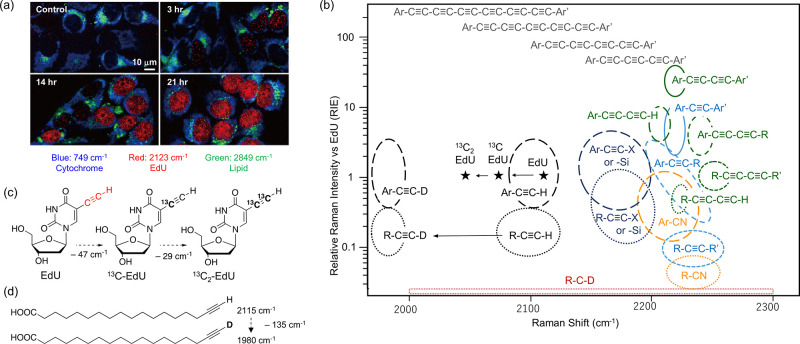

In 2011, for the first time, we proposed and demonstrated that alkynes are ideal tags for live-cell Raman imaging, successfully imaging 5-ethynyldeoxyuridine (EdU) using a line-scan spontaneous Raman microscope.90,91 Time-course Raman images showed EdU uptake according to the proliferation of HeLa cells (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) Time-course imaging of live HeLa cells treated with EdU. Images constructed based on signals of cytochrome (blue), EdU (red), and lipid (green) are overlaid. Adapted with permission from ref (90). Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society. (b) Structure-Raman shift/intensity relationship of various types of alkynes, nitriles, and deuterated compounds. The vertical axis shows relative Raman intensity versus EdU (RIE) on a logarithmic scale. (c) Structures and Raman shift changes of EdU and its 13C analogs. (d) Structures and Raman shift of 17-octadecynoic acid and its d-alkyne analog.

To further examine the potential of alkyne-tag Raman imaging (ATRI), we also examined the basic structure–Raman shift/intensity relationship and revealed that the Raman shifts of alkyne signals largely vary depending on the structure,92 and the intensity of Raman signals also varies depending on the structure. Because the absolute value changes depending on the measurement conditions and instrument, we used EdU in our experiments, which has been previously used in live-cell imaging, as a reference compound (= 1). Figure 5b schematically shows the range of Raman shifts and relative Raman intensities vs EdU (RIE) for various alkynes as well as nitriles and deuterium. The signals of the terminal alkynes (R–C≡CH) appeared in the low-wavenumber region (2080–2130 cm–1), while the signals of the internal alkynes (R–C≡C–R′) appeared in the high-wavenumber region (2200–2260 cm–1). Halogen- or silyl-substituted alkynes (R–C≡C–X or R–C≡C–SiMe3) showed signals in the intermediate region (2150–2200 cm–1). Along with the sharp signal of the alkyne with a narrow width, variation of the Raman shift (depending on the structure) makes the simultaneous imaging of multiple molecules possible by selecting an appropriate combination of alkyne tags.

Generally, conjugation to aromatic

rings increases intensity (R–C≡C–R′

< Ar–C≡C–R < Ar–C≡C–Ar);

therefore, for the imaging of a molecule with an aromatic ring, the

introduction of an alkyne tag to the aromatic ring is possible if

this does not affect biological activity. Notably, the conjugated

diyne shows one sharp peak, and its intensity is strong enough for

imaging, even without conjugation with an aromatic ring (R–C≡C–C≡C–R  Ar–C≡C–R). This is

an excellent tag for aliphatic compounds. Conjugation with an aromatic

ring further increases the Raman intensity, and bisarylbutadiyne (BADY,

Ar–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′) shows the

highest RIE value among the molecules we tested.

Ar–C≡C–R). This is

an excellent tag for aliphatic compounds. Conjugation with an aromatic

ring further increases the Raman intensity, and bisarylbutadiyne (BADY,

Ar–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′) shows the

highest RIE value among the molecules we tested.

Min et al.93 also synthesized a series of conjugated polyyne derivatives and demonstrated that the intensity of the Raman signal increased as the number of conjugated alkynes increased (Ar–C≡C–Ar′ < Ar–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′ < Ar–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′ < Ar–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′ < Ar–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′ < Ar–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–C≡C–Ar′). Interestingly, an approximately 40 cm–1 decrease of the wavenumber was observed as the alkyne number increased (bis-aryl hexatriyne, 2183 cm–1; bis-aryl octatetrayne, 2141 cm–1; bis-aryl-decapentayne, 2100 cm–1; bis-aryl dodecahexayne, 2066 cm–1). This collection of alkyne tags was further expanded by introducing isotopes. The replacement of one or two carbon atom(s) in the alkynes with the stable isotope 13C significantly changed its Raman shift, and the isotope-labeled alkynes could be used as distinct tags (Figure 5c). The Raman shift of alkyne stretching is dependent on the mass of two carbon atoms, and replacement by a heavy 13C atom is estimated to decrease the wavenumber based on Hooke’s law and density functional theory (DFT) calculations.94 The singly and doubly 13C-labeled EdU showed much lower frequencies (13C-EdU, 2077 cm–1; 13C2-EdU, 2048 cm–1) than the nonlabeled EdU (2125 cm–1). Imaging of cells treated simultaneously with 13C2-5-ethynyluridine (13C2-EU), 13C-EdU, and 17-octadecynoic acid has also been successfully demonstrated.94 Furthermore, by fine-tuning the structures of the bis-aryl polyynes with the introduction of 13C and a substituent on the aromatic ring, Raman tags with 20 distinct Raman frequencies, called the “Carbon rainbow” or “Carbow”, were synthesized.93 These Carbow tags were successfully applied in the supermultiplex imaging of cells as well as optical barcording.93

Recently, we found that much larger Raman shift changes (ca. 135 cm–1) are observed following the replacement of the hydrogen of terminal alkyne to deuterium (−C≡C–D), with the signal of the D-alkyne appearing at 1974–1985 cm–1. Although it is not possible to discriminate between 17-octadecynoic acid and EdU (because the Raman shifts of these molecules are almost the same), their simultaneous imaging is possible using D-labeled 17-octdecynoic acid (Figure 5d). The different behaviors of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids have also been visualized using D-labeled 17-octadecynoic acid and 17-Yne oleic acid.95

Raman imaging of various alkyne-tagged biomolecules has been reported (Figure 6). For example, SRS imaging of various alkyne-tagged metabolic precursors, EdU, EU, l-homopropargylglycine, propargyl choline, and 17-octadecynoic acid, has been used to visualize de novo synthesis of DNA, RNA, proteins, phospholipids, and triglycerides in live cells and C. elegans(96) as well as rat tissue.97 SRS imaging of peracetylated N-(4-pentynoyl)mannosamine (Ac4ManAl), which is expected to be converted into sialylated glycans, has also been reported in addition to other metabolic precursors.98,99 Glucose uptake activity in living cells and tissues was also successfully visualized using 3-O-propargyl-d-glucose (3-OPG).100

Figure 6.

Alkyne-tagged biomolecules (nucleic acid, amino acid, sugar, and lipid).

13C-labeled 3-OPG shows a distinct Raman signal compared to Glc-d7, which can be used as a lipogenesis probe. For example, cells with different glucose metabolic activities have been successfully discriminated based on ratiometric two-color SRS imaging using this approach.101 Recently, an alkyne-tagged sucrose analog was also synthesized, and its uptake to plant cells was monitored using SRS.102 In addition to these metabolic precursors, phenyl-diyne-tagged cholesterol (PhDY-Chol) has been used to visualize compartments of cholesterol storage in live C. elegans.103

As the Raman signal intensity of alkyne-tagged molecules is proportional to their concentration, it is also possible to quantify them in cells based on a calibration curve. The efficiencies of cell uptake of diyne-tagged ubiquinone derivatives (AltQs) with hydrophobic side chains of different lengths were estimated by quantifying the Raman signals.92 ATRI can also be used for the analysis of lipid phase separation, with the enrichment of diyne-tagged sphingomyelin (diyne-SM) in the lipid raft-like structure of an artificial membrane successfully visualized.104,105

3.1.3. Other Raman Tags

The nitrile shows a sharp peak in the cellular silent region, but its intensity is not very strong (Figure 3b). Thus, nitrile was first used as a tag in combination with metal nanoparticles to increase the signal via surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). In 2007, Tay and Pezacki et al.106 described the Raman imaging of ketone-modified cell-surface receptors on engineered HeLa cells using silver nanoparticles coated with a hydrazine derivative and a benzonitrile tag. Subsequently, Tian and Chen et al.98 succeeded in the SERS imaging of cell-surface sialylated glycans tagged with nitrile and azide using gold nanoparticles coated with phenylboronic acid, which preferentially formed esters with sialic acid and maintained sialylated glycans in close proximity to the surface of nanoparticles. With this SERS system, the same authors successfully detected cell-surface sialylated glycans derived from peracetylated N-(4-d3-acetyl)mannosamine based on the C–D signal. Azide-tagged cell surface proteins and glycans have also been successfully detected using SERS-active substrates.107 More recently, Raman imaging of mercaptoundecahydrododecaborane (BSH)-modified cholesterol (BSH-Chol) accumulated in HeLa cells was reported.108 In this research, although the signal of the B–H bond was much weaker than that of alkyne, BSH-Chol with 11 B–H bonds was successfully detected in the test cells.

3.2. Raman Imaging of Small Bioactive Molecules

In addition to the analysis of metabolic precursors of biomolecules, Raman imaging can provide valuable information on small bioactive molecules, such as natural products and drug candidates. Indeed, understanding the intracellular localization of molecules and their interactions with biomolecules including proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids is essential for the elucidation of molecular-level mechanisms of action. In drug development, monitoring the uptake and distribution of drug candidates in target cells/tissues is also required.

Although fluorescent imaging has been widely used, labeling of small molecules with large fluorophores normally changes their physical and biological properties, which is a significant limitation. Imaging methods using radioisotopes, magnetic resonance, and mass spectrometry are also available; however, these methods do not have sufficient spatial resolution to determine the subcellular distribution of small molecules. Thus, the Raman imaging of nonlabeled small molecules could be a promising approach. Indeed, recent advances in Raman microscopy and data analysis methods have made it possible to visualize the subcellular distribution of anticancer drugs,109−113 and recently, penicillin G in fungal cells was successfully imaged.114

Some drugs have intrinsic Raman tags such as alkynes and nitriles. Erlotinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has an alkyne in its structure, and its Raman imaging in colon cancer cells based on a strong alkyne signal was reported by Gerwert et al.115 Further detailed analysis of the Raman spectra revealed that erlotinib was metabolized to its demethylated form in the studied cells. This is an example of the potential of Raman microscopy for the detection of drug metabolism. We also reported live cell imaging of the mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP), using nitrile as an intrinsic Raman tag. The nitrile signals of the protonated and deprotonated forms are distinct, and their imaging clearly showed that FCCP exists as a deprotonated form in cytosol and as a protonated form in lipid droplets, indicating the potential of structure-based imaging as a sensor of the local environment.116 El-Mashtoly et al.117 reported the Raman imaging of another anticancer drug, neratinib, with an intrinsic nitrile group, with imaging based on the nitrile signal indicating its accumulation in lysosomes. In addition, these authors elucidated the structures of neratinib metabolites based on a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) of the Raman data, DFT calculation, and LC-MS analysis. Recently, Brunton et al.118 also reported the SRS imaging of ponatinib, another alkyne-containing anticancer drug, and stronger lysosomal trapping of this basic molecule was observed in drug-resistant cells compared to nonresistant cells. In addition to these studies, examples of the Raman-based imaging of bioactive molecules with external and intrinsic Raman tags are increasing.119

Coronatine is a virulence factor produced by pathogenic bacteria that promotes infection in two ways—by inhibiting stomatal closure and inducing stomatal reopening. The former is reportedly mediated by the nuclear proteins COI1 and JAZ, but the regulatory mechanism of the latter is unknown (Figure 7a). We synthesized a diyne-tagged coronatine derivative (diyne-COR) and found that this molecule induced stomatal reopening in a COI1-JAZ-independent manner. Raman imaging of the diyne-tagged coronatine in living guard cells clearly showed its specific localization in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).120 The involvement of the ethylene-signaling system at the ER in the stomatal reopening activity of coronatine was further clarified.121 To our knowledge, this is the first example demonstrating the contribution of alkyne-tag Raman imaging to understanding the mechanisms of action of natural products.

Figure 7.

(a) Use of alkyne-tag Raman imaging (ATRI) for clarifying the stomata-reopening mechanism of coronatine. Adapted with permission from ref (120). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society. (b) Alkyne-tag SERS imaging of cathepsin inhibitor (Alt-AOMK) uptake. Adapted with permission from ref (126). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

SRS imaging of diyne-tagged ferrostatin has also been reported, which is an antioxidant-type inhibitor of ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death that involves lipid peroxidation.122 In this work, the distribution of diyne-tagged ferrostatin to lysosomes, mitochondria, and ER was observed, with the authors speculating that ER is the site of ferrostatin action based on a range of experiments. More recently, examples of alkyne-tagged bioactive molecules have been increasing.123−125

In contrast to SRS, spontaneous Raman spectroscopy normally requires a much longer acquisition time, and it is difficult to monitor fast drug uptake. Recently, we solved this problem by combining an alkyne tag with SERS (Figure 7b). Because alkynes are expected to have a high affinity for transition metals, an ethynyl group was introduced to the cathepsin inhibitor (Alt-AOMK), and a strong SERS signal was confirmed in the presence of gold nanoparticles. Subsequently, gold nanoparticles were introduced into the lysosomes of live cells by endocytosis, and time-lapse 3D imaging of Alt-AOMK was performed. The quantitative evaluation of the uptake speed at the single-cell level using digital SERS counting was also performed under different conditions, demonstrating the potential of alkyne-tag SERS microscopy.126 Alkyne-tag SERS imaging has also been successfully applied to the serotonin reuptake inhibitor S-citalopram in brain slices.127

4. Probes for Raman Imaging

Based on the development of Raman tags, various Raman probes have been developed to selectively visualize specific organelles, proteins, enzymatic activities, and intracellular environments, such as pH, ion concentration, and redox state (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Examples of the application of Raman probes for cell analysis.

4.1. Organelle Markers

Currently, various fluorescent organelle markers are available, and their organelle-targeting functional groups can be used to design Raman organelle markers. Various Raman tags have been developed and applied with high sensitivity. We first developed a mitochondrial marker, MitoBADY, with a bisarylbutadiyne (BADY) structure as the tag and a triphenyl phosphonium structure as a mitochondria-targeting group.128 Min et al.93 developed mitochondria (Carbow2141 Mito), lysosome (Carbow2141 Lyso), plasma membrane (Carbow2141 PM), endoplasmic reticulum (Carbow2226 ER), and lipid droplet (Carbow2201 LD) markers using polyyne tags. Luo et al.129 reported that poly(deca-4,6-diynedioic acid) (PDDA) has a strong Raman intensity (up to ∼104 RIE) and can be used as an alkyne tag. In this case, PDDAs with lysosome-, mitochondria-, and nucleus-targeting molecules were demonstrated to act as excellent organelle markers in live cell SRS imaging. Recently, photoactivatable Raman organelle markers have been developed using diaryl cyclopropenones as masked Raman reporters, yielding diaryl alkynes with 405 nm light illumination.130 Using these photoactivatable Raman reporters, several organelle markers were prepared, and pulse-chase SRS imaging was successfully performed to track the movements of specific organelles.

Azobenezne-based resonant Raman reporters were also developed.131 Azobenzene is known to have an intrinsic nonradiative decay process that suppresses fluorescence, which disturbs the detection of resonance Raman scattering. It was shown that the absorption of azobenzene could be tuned by introducing substituents, and azobenzene with cyano and amino groups at the p-position of each benzene ring was found to have significant absorption at 532 nm, which is a commonly used wavelength for Raman microscopy. A strong enhancement in the Raman signal at 1375 cm–1 (ν Cph–N) was also observed, and Raman imaging of the plasma membrane and mitochondria was successfully performed by introducing organelle-targeting structures. The lysosome marker BBQ650-Lyso has also been developed, which shows strong resonant Raman effects at an excitation wavelength of 633 nm.132 Furthermore, a detailed study on the structure–Raman intensity relationship of various azobenzene derivatives is provided by Tang et al.133 This work showed that conjugation of the appropriate azobenzene structure to the bisaryl-polyyne enhances the RIE of the alkyne signal.

4.2. Raman Probes for Immunostaining

Immunostaining with fluorophore-modified antibodies has been widely used in biological research. In principle, multicolor immunostaining can be performed using antibodies with various Raman tags. However, the insufficient brightness of regular Raman tags is a problem that must be overcome. Because the size of antibodies is quite large, relatively large Raman tags can be used. For example, SERS imaging of cell-surface antigens using metal nanoparticles modified with Raman reporters conjugated with antibodies has been examined,134,135 and various SERS probes have been developed to date.136,137 However, image resolution is typically low, and accessibility to intracellular proteins could be a problem because of the relatively large particle size. Dai et al.138 described immunostaining of cell-surface proteins using single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNT) with strong resonant Raman scattering signals using a 785 nm laser. They conjugated 12C-SWNT and its isotopomer 13C-SWNT, with Raman signals at 1590 and 1544 cm–1 for the anti-Her2 antibody (Herceptin) and anti-Her1 antibody (Erbitux), respectively. Crucially, these two Raman-tagged antibodies successfully discriminated cells expressing each protein.

Although resonant Raman scattering is a powerful method for achieving strong signals, its usefulness is limited. If ordinary dyes other than azobenzenes are used, the fluorescent background interferes with the observation of the Raman signals. In 2017, Min et al.43 found that both a high-sensitivity and low-electronic-resonance background could be realized by SRS under electronic preresonance conditions (eprSRS). The same research group subsequently developed a series of nitrile and alkyne-containing pyronin-based dyes (MARS dyes).43,139 These dyes displayed strong Raman signals in the cellular silent region, achieving identification of different types of nerve cells by simultaneous immunostaining of tubulin, myelin basic protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Various polymers containing high-density Raman tags, such as alkyne, deuterium, and nitrile, have also been developed, some of which have been applied to cell imaging by conjugating with nucleic acid aptamers and targeting peptides.140 Recently, Raman-active nanoparticles (Rdots) with ultrabrightness and compact sizes (∼20 nm) have been described,141 which are easily prepared by a simple swelling-diffusion method from polystyrene nanoparticles and Carbow dye without the formation of covalent bonds. Rdots show an RIE of over 104, which is bright enough for immunostaining. Multiplexed live-cell imaging using antibodies with Rdots has also been demonstrated using SRS microscopy.142

4.3. Raman Probes for Enzymatic Activity

In addition to immunostaining probes that detect the presence of specific proteins, Raman probes that can monitor enzymatic activity have also been reported. In 2018, Li et al.143 reported the use of SERS probes for imaging assays of endonuclease activity in live cells. They designed alloyed Au/Ag nanoparticles modified with phenylacetylene and diphenyl acetylene-tagged single-stranded DNA, which showed two distinct SERS signals (1983 and 2212 cm–1) derived from each alkyne. After cleavage of the DNA by endonuclease, the SERS signal of diphenylacetylene released from the nanoparticle diminished, and the activation of the endonuclease in cells by treatment with an apoptosis-inducing agent was clearly demonstrated by ratiometric analysis. The same group also reported a similar SERS probe for caspase-3, in which a peptide containing the cleavage sequence was used instead of DNA.144 In this case, caspase-3 activation in live cells and tissues was demonstrated by ratiometric imaging analysis.

In 2020, Kamiya et al.145 developed activatable Raman probes based on several different principles. They identified a xanthene derivative bearing a nitrile group at position 9 (9CN-JCP) as a suitable scaffold dye and designed probes in which the molecular absorption shifted from the electronic nonresonance region to the electronic preresonance region before and after the enzyme reaction, resulting in the SRS signal turning on from off. They developed probes for three different aminopeptidases and glycosidases with isotope-edited dye (9CN-JCP, 2217 cm–1; 9C15N-JCP, 2190 cm–1; 913CN-JCP, 2166 cm–1; and 913C15N-JCP, 2137 cm–1), and simultaneous imaging of the activities of the four enzymes in live cells was successfully performed.

4.4. Raman Sensors

Several small-molecule Raman probes have recently been developed for sensing endogenous biomolecules and ions. Min et al.146 reported a hydrogen sulfide (H2S) sensor equipped with an azide as a reactive site, a bisarylbutadiyne (BADY) as a Raman reporter, and a mitochondria-targeting triphenyl phosphonium group. The reduction of azide to amino groups by H2S causes a change in the alkyne Raman signal, and the SRS ratiometric images show a change in H2S levels in live cells. Faulds, Graham, and Tomkinson et al.147 designed a series of Raman pH sensors based on the BADY structure. They prepared various BADY derivatives with acidic groups, such as phenolic OH, and/or basic groups, such as NH2, and the Raman shifts of the protonated and deprotonated forms were measured for each molecule. They estimated intracellular pH using SRS ratiometric images of the signals derived from the protonated and deprotonated forms. Fine-tuning of the pKa is also possible by the introduction of additional fluorine atom(s) to the probe molecules, and an appropriate probe molecule can be selected depending on the pH range of interest. This group also prepared a mitochondria-targeting pH sensor, Mitokyne, which can detect subtle changes in mitochondrial pH. Subsequently, mitochondrial dynamics during mitophagy were monitored in a time-resolved manner using Mitokyne with subcellular spatial resolution.148 Various other Raman sensors for specific molecules and ions could be developed based on their known reactivity.149,150

5. Future Perspectives

In comparison with fluorescence imaging, the main advantage of Raman imaging is the large number of tags or probes that can be detected simultaneously. When labeling small bioactive compounds, fluorescent dyes often affect biological activity; however, small Raman tags can be introduced without affecting bioactivity, and the bioactive compounds in living cells can be visualized. In contrast, the detection sensitivity of Raman imaging is much lower than that of fluorescence imaging. Improving the sensitivity of Raman measurements is one of the most critical issues for wider application in biological and medical contexts. Although SRS and CARS microscopies successfully increase the Raman scattering signal, they simultaneously generate a nonresonant background signal that does not reflect the vibration of the target. Because of this, the lowest detectable concentration of molecules is limited to a few hundred micromolar to a few millimolar. This value is similar to that observed in spontaneous Raman scattering microscopy. Therefore, in SRS/CARS microscopy, reducing the amount of background light that is nonresonant to molecular vibrations is a priority for improving sensitivity. So far, techniques using laser frequency modulation151 and long-pulsed laser light for stimulated emission152 have been proposed. However, the improvement in sensitivity achieved is only a few times greater than that of conventional techniques. The use of SERS, which is observed on metal surfaces, has attracted attention as a technique to improve the sensitivity of detecting low-concentration molecules. Although SERS improves the signal drastically (typically 104 to 106 times), the enhancement is very sensitive to the surface condition of the metal. Therefore, intensity fluctuations and drift in the Raman peaks typically occur, which makes quantitative measurement and interpretation of spectra difficult.153 SERS can be used for applications where these issues are relatively unaffected, such as the observation of small molecules tagged with alkynes, as described in section 3.2(126)

In addition to imaging, we have successfully applied Raman spectroscopy to chemical proteomics. In chemical biology research, alkyne tags are used for the analysis of target proteins labeled with bioactive compounds in combination with a click reaction; the target protein is labeled with an alkyne-tagged compound, and the click reaction can install various tags such as biotin. Using the biotin tag, the target protein is purified, digested into peptides, and finally identified by MS/MS analysis. However, the identification of labeled sites is sometimes difficult because of the large structure of the introduced tag, which affects the physical properties of labeled peptides and disturbs detection by the MS analysis. To overcome this problem, we established alkyne-tag Raman screening (ATRaS) for the direct detection of alkyne-labeled peptides.154 In this method, we can detect alkyne-labeled peptides with a detection limit of almost 100 fmol, which has enabled the identification of the cathepsin B labeled site using the alkyne-tagged inhibitor Alt-AOMK. To improve the Raman signal of alkyne tags, we applied SERS with silver nanoparticles to form a stable silver acetylide. We also developed a Raman plate reader using a multifocus detection system. In this system, we were able to obtain 192 Raman spectra simultaneously and within a few seconds.155 In combination with ATRaS, a Raman plate reader is expected to realize a comprehensive analysis of the binding sites of alkyne-tagged compounds. In addition, this Raman plate reader has also been used to detect drug polymorphisms, with other applications expected in the future.

The development of new Raman probes and analytical methods should further expand the potential of Raman spectroscopy for chemical biology research. For example, recently, Wei et al. reported a new method for Raman imaging-based local environment sensing via hydrogen–deuterium exchange (HDX) of the terminal alkyne tag.156 This work demonstrates that UV-induced thymidine dimer formation can be detected by alkyne-HDX from EdU-labeled cells.

To expand the observation targets of biomedical studies, Raman imaging techniques with improved spatial resolution and the capability of deep-tissue imaging are expected in the near future. In fluorescence microscopy, super-resolution microscopy, which increases the spatial resolution of observation beyond the diffraction limit of light, and 3D imaging techniques, which can observe the deep parts of a sample, are widely used, and some of these techniques are also available for Raman microscopy. For example, to improve the spatial resolution of Raman imaging, techniques using structured illumination,157 image scanning,158 higher-order nonlinear response,159−161 sample expansion,162 and stimulated emission depletion163 have been reported. However, the signal volume typically decreases as the spatial resolution is improved, and sensitivity issues become more pronounced. Therefore, the practical use of these techniques is currently limited, and it is necessary to develop these technologies together with sensitivity improvements. For the observation of deep biological structures, techniques utilizing the transparency of tissue clearing162,164 and side illumination, such as light-sheet illumination,165−167 have been proposed. The fusion of these techniques with Raman technology is expected to reveal the role of molecules in various biological events in greater detail than has been previously possible.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the JST ERATO Sodeoka Live Cell Chemistry Project, JST CREST (Grant Number JPMJCR1925), and AMED-CREST, AMED (Grant Number JP17gm0710004). We would like to thank Dr. Jun Ando (RIKEN) for obtaining the data for Figure 2b.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Gibbs R. A. The Human Genome Project Changed Everything. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 575–576. 10.1038/s41576-020-0275-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adli M. The CRISPR Tool Kit for Genome Editing and Beyond. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1911. 10.1038/s41467-018-04252-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff O. A. C. GABA and Glutamate in the Human Brain. Neuroscientist 2002, 8, 562–573. 10.1177/1073858402238515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C. D. Prostaglandins and Leukotrienes: Advances in Eicosanoid Biology. Science 2001, 294, 1871–1875. 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein B. E.; Meissner A.; Lander E. S. The Mammalian Epigenome. Cell 2007, 128, 669–681. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudakov D. M.; Matz M. V.; Lukyanov S.; Lukyanov K. A. Fluorescent Proteins and Their Applications in Imaging Living Cells and Tissues. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1103–1163. 10.1152/physrev.00038.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levsky J. M.; Singer R. H. Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization: Past, Present and Future. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 2833–2838. 10.1242/jcs.00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis L. D.; Raines R. T. Bright Building Blocks for Chemical Biology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 855–866. 10.1021/cb500078u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada K.; Fujita K.; Smith N. I.; Kobayashi M.; Inouye Y.; Kawata S. Raman Microscopy for Dynamic Molecular Imaging of Living Cells. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008, 13, 044027. 10.1117/1.2952192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno M.; Hamaguchi H. Multifocus Confocal Raman Microspectroscopy for Fast Multimode Vibrational Imaging of Living Cells. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 4096–4098. 10.1364/OL.35.004096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Zhang D.; Cheng J.-X. Coherent Raman Scattering Microscopy in Biology and Medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 17, 415–445. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071114-040554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. H.; Fu D. Cellular Imaging Using Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91 (15), 9333–9342. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey P. R.Biochemical Applications of Raman and Resonance Raman Spectroscopies; Academic Press, 1982. 10.1016/B978-0-12-159650-7.X5001-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palonpon A. F.; Sodeoka M.; Fujita K. Molecular Imaging of Live Cells by Raman Microscopy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 708–715. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunbajakava N.; Lenferink A.; Kraan Y.; Volokhina E.; Vrensen G.; Greve J.; Otto C. Nonresonant Confocal Raman Imaging of DNA and Protein Distribution in Apoptotic Cells. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 3968–3981. 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-S.; Karashima T.; Yamamoto M.; Hamaguchi H. Molecular-Level Investigation of the Structure, Transformation, and Bioactivity of Single Living Fission Yeast Cells by Time- and Space-Resolved Raman Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 10009–10019. 10.1021/bi050179w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerer T.; Axäng C.; Brackmann C.; Hillertz P.; Pilon M.; Enejder A. Monitoring of Lipid Storage in Caenorhabditis Elegans Using Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 14658–14663. 10.1073/pnas.0703594104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmad-Rohen A.; Regan D.; Masia F.; McPhee C.; Pope I.; Langbein W.; Borri P. Quantitative Label-Free Imaging of Lipid Domains in Single Bilayers by Hyperspectral Coherent Raman Scattering. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 14657–14666. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c03179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Fu Y.; Zickmund P.; Shi R.; Cheng J. X. Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Imaging of Axonal Myelin in Live Spinal Tissues. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 581–591. 10.1529/biophysj.105.061911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. M.; Chen H. C.; Chang W. T.; Jhan J. W.; Lin H. L.; Liau I. Quantitative Assessment of Hepatic Fat of Intact Liver Tissues with Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 1496–1504. 10.1021/ac8026838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. L.; Xu X.; Kesari S.; Xie X. S.; Wong S. T. C.; Young G. S. Chemically-Selective Imaging of Brain Structures with CARS Microscopy. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 12076. 10.1364/OE.15.012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. L.; Potma E. O.; Puoris’haag M.; Côté D.; Lin C. P.; Xie X. S. Chemical Imaging of Tissue in Vivo with Video-Rate Coherent Anti-Strokes Raman Scattering Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 16807–16812. 10.1073/pnas.0508282102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel I. I.; Trevisan J.; Evans G.; Llabjani V.; Martin-Hirsch P. L.; Stringfellow H. F.; Martin F. L. High Contrast Images of Uterine Tissue Derived Using Raman Microspectroscopy with the Empty Modelling Approach of Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares. Analyst 2011, 136, 4950–4959. 10.1039/c1an15717e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrabie V.; Gobinet C.; Piot O.; Tfayli A.; Bernard P.; Huez R.; Manfait M. Independent Component Analysis of Raman Spectra: Application on Paraffin-Embedded Skin Biopsies. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2007, 2, 40–50. 10.1016/j.bspc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D.; Lu F. K.; Zhang X.; Freudiger C.; Pernik D. R.; Holtom G.; Xie X. S. Quantitative Chemical Imaging with Multiplex Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3623–3626. 10.1021/ja210081h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki Y.; Umemura W.; Otsuka Y.; Satoh S.; Hashimoto H.; Sumimura K.; Nishizawa N.; Fukui K.; Itoh K. High-Speed Molecular Spectral Imaging of Tissue with Stimulated Raman Scattering. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 845–851. 10.1038/nphoton.2012.263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ando M.; Hamaguchi H. Molecular Component Distribution Imaging of Living Cells by Multivariate Curve Resolution Analysis of Space-Resolved Raman Spectra. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 011016. 10.1117/1.JBO.19.1.011016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp C. H.; Lee Y. J.; Heddleston J. M.; Hartshorn C. M.; Walker A. R. H.; Rich J. N.; Lathia J. D.; Cicerone M. T. High-Speed Coherent Raman Fingerprint Imaging of Biological Tissues. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 627–634. 10.1038/nphoton.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro T. G.; Strekas T. C. Resonance Raman Spectra of Heme Proteins. Effects of Oxidation and Spin State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 338–345. 10.1021/ja00809a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta P. K.; Spencer R.; Walsh C.; Spiro T. G. Resonance Raman and Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Spectra of Flavin Derivatives. Vibrational Assignments and the Zwitterionic Structure of 8-Methylamino-Riboflavin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1980, 623, 77–83. 10.1016/0005-2795(80)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin J. C. Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Carotenoids and Carotenoid-Containing Systems. Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 785–792. 10.1351/pac198557050785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M.; Smith N. I.; Palonpon A. F.; Endo H.; Kawata S.; Sodeoka M.; Fujita K. Label-Free Raman Observation of Cytochrome c Dynamics during Apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 28–32. 10.1073/pnas.1107524108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazhe N. A.; Treiman M.; Brazhe A. R.; Find N. L.; Maksimov G. V.; Sosnovtseva O. V. Mapping of Redox State of Mitochondrial Cytochromes in Live Cardiomyocytes Using Raman Microspectroscopy. PLoS One 2012, 7, e41990 10.1371/journal.pone.0041990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T.; Minamikawa T.; Harada Y.; Yamaoka Y.; Tanaka H.; Yaku H.; Takamatsu T. Label-Free Evaluation of Myocardial Infarct in Surgically Excised Ventricular Myocardium by Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14671. 10.1038/s41598-018-33025-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T.; Chiu L. Da; Kanda H.; Kawagoe H.; Ozawa T.; Nakamura M.; Nishida K.; Fujita K.; Fujikado T. Using Redox-Sensitive Mitochondrial Cytochrome Raman Bands for Label-Free Detection of Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Analyst 2019, 144, 2531–2540. 10.1039/C8AN02213E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Liu J.; Tian L.; Zhang Q.; Guan Y.; Chen L.; Liu G.; Yu H. Q.; Tian Y.; Huang Q. Raman Micro-Spectroscopy Monitoring of Cytochrome c Redox State in: Candida utilis during Cell Death under Low-Temperature Plasma-Induced Oxidative Stress. Analyst 2020, 145, 3922–3930. 10.1039/D0AN00507J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Liao H.; Bando K.; Nawa Y.; Fujita S.; Fujita K. Label-Free Monitoring of Drug-Induced Cytotoxicity and Its Molecular Fingerprint by Live-Cell Raman and Autofluorescence Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 10019–10026. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramczyk H.; Brozek-Pluska B.; Kopeć M. Double Face of Cytochrome c in Cancers by Raman Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2120. 10.1038/s41598-022-04803-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Nawa Y.; Ishida S.; Kanda Y.; Fujita S.; Fujita K. Label-Free Chemical Imaging of Cytochrome P450 Activity by Raman Microscopy. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 778. 10.1038/s42003-022-03713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiue H.; Sasaki M.; Yoshikawa Y.; Toyofuku M.; Shigeto S. Raman Spectroscopic Signatures of Carotenoids and Polyenes Enable Label-Free Visualization of Microbial Distributions within Pink Biofilms. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7704. 10.1038/s41598-020-64737-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikan S.; Sands H. S.; Rodway R. G.; Batchelder D. N. Raman spectroscopy and imaging of beta-carotene in live corpus luteum cells. Anim Reprod Sci. 2002, 71, 249–266. 10.1016/S0378-4320(02)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; George E. W.; Rognon G. T.; Gorusupudi A.; Ranganathan A.; Chang F. Y.; Shi L.; Frederick J. M.; Bernstein P. S. Imaging lutein and zeaxanthin in the human retina with confocal resonance Raman microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 12352–12358. 10.1073/pnas.1922793117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Chen Z.; Shi L.; Long R.; Anzalone A. V.; Zhang L.; Hu F.; Yuste R.; Cornish V. W.; Min W. Super-Multiplex Vibrational Imaging. Nature 2017, 544, 465–470. 10.1038/nature22051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auner G. W.; Koya S. K.; Huang C.; Broadbent B.; Trexler M.; Auner Z.; Elias A.; Mehne K. C.; Brusatori M. A. Applications of Raman Spectroscopy in Cancer Diagnosis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 691–717. 10.1007/s10555-018-9770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard T. J. E.; Shore A.; Stone N. Raman Spectroscopy for Rapid Intra-Operative Margin Analysis of Surgically Excised Tumour Specimens. Analyst 2019, 144, 6479–6496. 10.1039/C9AN01163C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jermyn M.; Mok K.; Mercier J.; Desroches J.; Pichette J.; Saint-Arnaud K.; Bernstein L.; Guiot M.-C.; Petrecca K.; Leblond F. Intraoperative Brain Cancer Detection with Raman Spectroscopy in Humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 274ra19. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura T.; Chiu L.; Fujita K.; Kawata S.; Watanabe T. M.; Yanagida T.; Fujita H. Visualizing Cell State Transition Using Raman Spectroscopy. PLoS One 2014, 9, e84478 10.1371/journal.pone.0084478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghita A.; Pascut F. C.; Sottile V.; Denning C.; Notingher I. Applications of Raman Micro-Spectroscopy to Stem Cell Technology: Label-Free Molecular Discrimination and Monitoring Cell Differentiation. EPJ. Technol. Instrum. 2015, 2, 6. 10.1140/epjti/s40485-015-0016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germond A.; Panina Y.; Shiga M.; Niioka H.; Watanabe T. M. Following Embryonic Stem Cells, Their Differentiated Progeny, and Cell-State Changes During IPS Reprogramming by Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 14915–14923. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. C.; Xu J.; Brinkhof B.; Wang H.; Cui Z.; Huang W. E.; Ye H. A Single-Cell Raman-Based Platform to Identify Developmental Stages of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 18412–18423. 10.1073/pnas.2001906117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto A.; Yamaguchi Y.; Chiu L.; Morimoto C.; Fujita K.; Takedachi M.; Kawata S.; Murakami S.; Tamiya E. Time-Lapse Raman Imaging of Osteoblast Differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12529. 10.1038/srep12529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan S.; Schulze H. G.; Vardaki M. Z.; Blades M. W.; Piret J. M.; Turner R. F. B. Applications of Raman Spectroscopy in the Development of Cell Therapies: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Analyst 2020, 145, 2070–2105. 10.1039/C9AN01811E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura T.; Chiu L.; Fujita K.; Machiyama H.; Yamaguchi T.; Watanabe T. M.; Fujita H. Non-Label Immune Cell State Prediction Using Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37562. 10.1038/srep37562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavillon N.; Hobro A. J.; Akira S.; Smith N. I. Noninvasive Detection of Macrophage Activation with Single-Cell Resolution through Machine Learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E2676-E2685 10.1073/pnas.1711872115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germond A.; Ichimura T.; Horinouchi T.; Fujita H.; Furusawa C.; Watanabe T. M. Raman Spectral Signature Reflects Transcriptomic Features of Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia Coli. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 85. 10.1038/s42003-018-0093-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi-Kirschvink K. J.; Nakaoka H.; Oda A.; Kamei K.-i. F.; Nosho K.; Fukushima H.; Kanesaki Y.; Yajima S.; Masaki H.; Ohta K.; Wakamoto Y. Linear Regression Links Transcriptomic Data and Cellular Raman Spectra. Cell Syst. 2018, 7, 104–117. 10.1016/j.cels.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Reste P.-J.; Pilalis E.; Aubry M.; McMahon M.; Cano L.; Etcheverry A.; Chatziioannou A.; Chevet E.; Fautrel A. Integration of Raman Spectra with Transcriptome Data in Glioblastoma Multiforme Defines Tumour Subtypes and Predicts Patient Outcome. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 10846–10856. 10.1111/jcmm.16902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y.; Kobayashi K.; Wakisaka Y.; Deng D.; Tanaka S.; Huang C. J.; Lei C.; Sun C. W.; Liu H.; Fujiwaki Y.; Lee S.; Isozaki A.; Kasai Y.; Hayakawa T.; Sakuma S.; Arai F.; Koizumi K.; Tezuka H.; Inaba M.; Hiraki K.; Ito T.; Hase M.; Matsusaka S.; Shiba K.; Suga K.; Nishikawa M.; Jona M.; Yatomi Y.; Yalikun Y.; Tanaka Y.; Sugimura T.; Nitta N.; Goda K.; Ozeki Y. Label-Free Chemical Imaging Flow Cytometry by High-Speed Multicolor Stimulated Raman Scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 15842–15848. 10.1073/pnas.1902322116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K. C.; Li J.; Zhang C.; Tan Y.; Cheng J. X. Multiplex Stimulated Raman Scattering Imaging Cytometry Reveals Lipid-Rich Protrusions in Cancer Cells under Stress Condition. iScience 2020, 23, 100953. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta N.; Iino T.; Isozaki A.; Yamagishi M.; Kitahama Y.; Sakuma S.; Suzuki Y.; Tezuka H.; Oikawa M.; Arai F.; Asai T.; Deng D.; Fukuzawa H.; Hase M.; Hasunuma T.; Hayakawa T.; Hiraki K.; Hiramatsu K.; Hoshino Y.; Inaba M.; Inoue Y.; Ito T.; Kajikawa M.; Karakawa H.; Kasai Y.; Kato Y.; Kobayashi H.; Lei C.; Matsusaka S.; Mikami H.; Nakagawa A.; Numata K.; Ota T.; Sekiya T.; Shiba K.; Shirasaki Y.; Suzuki N.; Tanaka S.; Ueno S.; Watarai H.; Yamano T.; Yazawa M.; Yonamine Y.; Di Carlo D.; Hosokawa Y.; Uemura S.; Sugimura T.; Ozeki Y.; Goda K. Raman Image-Activated Cell Sorting. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3452. 10.1038/s41467-020-17285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant T. G. Using Deuterium in Drug Discovery: Leaving the Label in the Drug. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3595–3611. 10.1021/jm4007998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber B. P.; Yager P.; Peticolas W. L. Deuterated Phospholipids as Nonperturbing Components for Raman Studies of Biomembranes. Biophys. J. 1978, 22, 191–207. 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potma E. O.; Xie X. S. Direct Visualization of Lipid Phase Segregation in Single Lipid Bilayers with Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy. ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 77–79. 10.1002/cphc.200400390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtom G. R.; Thrall B. D.; Chin B. Y.; Wiley H. S.; Colson S. D. Achieving Molecular Selectivity in Imaging Using Multiphoton Raman Spectroscopy Techniques. Traffic 2001, 2, 781–788. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen H. J.; Kraan Y. M.; Roos D.; Otto C. Single-Cell Raman and Fluorescence Microscopy Reveal the Association of Lipid Bodies with Phagosomes in Leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 10159–10164. 10.1073/pnas.0502746102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X. S.; Yu J.; Yang W. Y. Living Cells as Test Tubes. Science 2006, 312, 228–230. 10.1126/science.1127566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D.; Yu Y.; Folick A.; Currie E.; Farese R. V.; Tsai T.-H. H.; Xie X. S.; Wang M. C. In Vivo Metabolic Fingerprinting of Neutral Lipids with Hyperspectral Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8820–8828. 10.1021/ja504199s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus C.; Krafft C.; Dietzek B.; Brehm B. R.; Lorkowski S.; Popp J. Noninvasive Imaging of Intracellular Lipid Metabolism in Macrophages by Raman Microscopy in Combination with Stable Isotopic Labeling. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8549–8556. 10.1021/ac3012347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F.; Wei L.; Zheng C.; Shen Y.; Min W. Live-Cell Vibrational Imaging of Choline Metabolites by Stimulated Raman Scattering Coupled with Isotope-Based Metabolic Labeling. Analyst 2014, 139, 2312–2317. 10.1039/C3AN02281A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratil A. R.; Shchepinov M. S.; Dennis E. A. Lipidomics Reveals Dramatic Physiological Kinetic Isotope Effects during the Enzymatic Oxygenation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Ex Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 235–243. 10.1021/jacs.7b09493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodo K.; Sato A.; Tamura Y.; Egoshi S.; Fujiwara K.; Oonuma K.; Nakao S.; Terayama N.; Sodeoka M. Synthesis of Deuterated γ-Linolenic Acid and Application for Biological Studies: Metabolic Tuning and Raman Imaging. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2180–2183. 10.1039/D0CC07824G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiebing C.; Schmölz L.; Wallert M.; Matthäus C.; Lorkowski S.; Popp J. Raman Imaging of Macrophages Incubated with Triglyceride-Enriched OxLDL Visualizes Translocation of Lipids between Endocytic Vesicles and Lipid Droplets. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 876–883. 10.1194/jlr.M071688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus C.; Kale A.; Chernenko T.; Torchilin V.; Diem M. New Ways of Imaging Uptake and Intracellular Fate of Liposomal Drug Carrier Systems inside Individual Cells, Based on Raman Microscopy. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2008, 5, 287–293. 10.1021/mp7001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Cheng J.-X. Direct Visualization of de Novo Lipogenesis in Single Living Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 6807. 10.1038/srep06807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W.; Karanja C. W.; Abutaleb N. S.; Younis W.; Zhang X.; Seleem M. N.; Cheng J.-X. Antibiotic Susceptibility Determination within One Cell Cycle at Single-Bacterium Level by Stimulated Raman Metabolic Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3737–3743. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J.; Su Y.; Qian C.; Yuan D.; Miao K.; Lee D.; Ng A. H. C.; Wijker R. S.; Ribas A.; Levine R. D.; Heath J. R.; Wei L. Raman-Guided Subcellular Pharmaco-Metabolomics for Metastatic Melanoma Cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4830. 10.1038/s41467-020-18376-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.; Du J.; Yu R.; Su Y.; Heath J. R.; Wei L. Visualizing Subcellular Enrichment of Glycogen in Live Cancer Cells by Stimulated Raman Scattering. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 13182–13191. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen H.-J. J.; Lenferink A.; Otto C. Noninvasive Imaging of Protein Metabolic Labeling in Single Human Cells Using Stable Isotopes and Raman Microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 9576–9582. 10.1021/ac801841y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Yu Y.; Shen Y.; Wang M. C.; Min W. Vibrational Imaging of Newly Synthesized Proteins in Live Cells by Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 11226–11231. 10.1073/pnas.1303768110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Shen Y.; Xu F.; Hu F.; Harrington J. K.; Targoff K. L.; Min W. Imaging Complex Protein Metabolism in Live Organisms by Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy with Isotope Labeling. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 901–908. 10.1021/cb500787b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Chen C.; Xiong H.; Ji J.; Min W. Metabolic Activity Phenotyping of Single Cells with Multiplexed Vibrational Probes. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 9603–9612. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]