Abstract

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is an MRI technique for imaging the mechanical properties of brain in vivo, and has shown differences in properties between neuroanatomical regions and sensitivity to aging, neurological disorders, and normal brain function. Past MRE studies investigating these properties have typically assumed the brain is mechanically isotropic, though the aligned fibers of white matter suggest an anisotropic material model should be considered for more accurate parameter estimation. Here we used a transversely isotropic, nonlinear inversion algorithm (TI-NLI) and multiexcitation MRE to estimate the anisotropic material parameters of individual white matter tracts in healthy young adults. We found significant differences between individual tracts for three recovered anisotropic parameters: substrate shear stiffness, μ (range: 2.57 – 3.02 kPa), shear anisotropy, ϕ (range: −0.026 – 0.164), and tensile anisotropy, ζ (range: 0.559 – 1.049). Additionally, we demonstrated the repeatability of these parameter estimates in terms of lower variability of repeated measures in a single subject relative to variability in our sample population. Further, we observed significant differences in anisotropic mechanical properties between segments of the corpus callosum (genu, body, and splenium), which is expected based on differences in axonal microstructure. This study shows the ability of MRE with TI-NLI to estimate anisotropic mechanical properties of white matter and presents reference properties for tracts throughout the healthy brain.

Keywords: Magnetic Resonance Elastography, Brain, Stiffness, Anisotropy, White Matter

1. Introduction:

Imaging methods which are sensitive to the health and structural integrity of white matter (WM) tissue are important for characterizing many neuropathological conditions, including multiple sclerosis [1] and traumatic brain injury [2,3]. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) has shown promise in assessing changes to the microstructural integrity of brain tissue through quantification of its viscoelastic mechanical properties [4,5]. Past MRE studies have found non-specific softening of brain tissue in multiple sclerosis [1,6,7], Alzheimer’s disease [8,9], and Parkinson’s disease [10], indicating a loss of structural integrity in neurodegeneration. However, softening is also reported in normal aging [11–13], which limits MRE as a diagnostic imaging modality. In vivo brain MRE studies often assume brain parenchyma is mechanically isotropic in order to simplify the inversion algorithm and property estimation, even though WM tracts exhibit direction-dependent mechanical properties due to their bundles of aligned axons, and thus, isotropic MRE methods can introduce uncertainty in WM regions from model-data mismatch [14]. Therefore, anisotropic inversion methods are likely to be necessary to estimate the properties of WM tracts accurately and recover material parameters sufficient to discriminate normal aging processes from neurodegenerative diseases. Accordingly, the spectrum of properties estimated in anisotropic MRE models may separate and distinguish the wide range of conditions which appear to cause the tissue softening estimated with isotropic approaches.

Anisotropic MRE inversion methods reported to date vary their underlying anisotropic material models and the corresponding number of descriptive material parameters [15–20]. A three-parameter material model that describes white matter as a nearly incompressible, transversely isotropic (NITI) material within the space of a single voxel involves parameters that incorporate both shear and tensile anisotropy, or the ratios of shear modulus and Young’s modulus parallel and perpendicular to the fiber direction [21–23]. It balances accurate modeling of the mechanical behavior of materials with aligned fiber tracts (i.e. WM) [24], with minimal increase in the number of property parameters required for estimation from MRE displacement maps. However, estimating these parameters requires displacement data from mechanical waves having different propagation and polarization directions [25], which is difficult to achieve with sufficient SNR from a single MRE scan. To address this, we have previously implemented multi-excitation MRE in which two drivers, placed in perpendicular orientations, produce mechanical waves in sequential acquisitions sufficient to generate the wave pattern differences necessary to capture the directionally-dependent material properties of WM [14,26].

Estimating the spatial distribution of anisotropic mechanical properties accurately in WM tracts requires an inversion algorithm that accounts for material heterogeneity. WM is strongly heterogeneous comprising large tracts that differ in mechanical properties [27] as well as fiber direction. McGarry, et al. [28] developed a transversely isotropic nonlinear inversion (TI-NLI) to recover heterogenous anisotropic parameters, and demonstrated accurate estimation of NITI anisotropic property parameter fields when combined with multi-excitation MRE data [29]. Incorporating both anisotropy and heterogeneity in the mechanical model during inversion reduces model-data mismatch and improves property estimates in regions containing WM tracts. Johnson, et al. [27] estimated properties of WM tracts with MRE, though that study utilized an isotropic model and the reported parameter values do not capture direction-dependent material behavior. Local properties have also been reported in cerebral lobes [30] and subcortical gray matter structures [31], which have shown regional sensitivity to aging [32,33], neurological disease [34–36], and cognitive function [37,38]. Understanding the anisotropic properties of WM tracts may further improve the utility of MRE in these applications.

In this study, we measured the anisotropic mechanical properties of individual WM tracts in vivo using multi-excitation MRE with TI-NLI. To collect the multi-excitation data required, we used a custom designed passive driver combined with the standard pillow driver common in brain MRE. We examined the repeatability of anisotropic parameter estimates from MRE data collected with this custom multi-excitation driver coupled with TI-NLI. We estimated the average anisotropic material parameters of gray and white matter in a sample of healthy, young adults, and in individual white matter tracts, such as the corpus callosum and the corona radiata. We further analyzed the heterogeneity in material properties between individual regions of the corpus callosum to examine potential relationships with underlying axonal microstructure.

2. Methods

Seventeen healthy participants (7/10 M/F; 22–30 years old) provided informed, written consent to participate in the study approved by our Institutional Review Board. Each participant completed an imaging session on a Siemens 3T Prisma MRI scanner with a 20-channel head coil. One subject completed the protocol ten times to quantify repeatability of the outcome measures.

2.1. Data Acquisition:

The protocol included multi-excitation MRE scans with excitation in both left-right (LR) and anterior-posterior (AP) directions. We designed a secondary actuator to generate LR actuation [39,40] with the goal of improved reliability and stability of applied vibrations relative to previous approaches, for example as described in Anderson, et al. [14] and Smith, et al. [26]. The custom LR actuator includes two flexible bottles attached to the head coil using custom 3D printed pieces, shown in Figure 1. These bottles contacted the sides of the head near the temples – one was connected to an active pneumatic driver and the second acted as a support; both were adjustable for different head sizes. This design provides greater coupling between actuator and skull and improves stability over previous approaches by being anchored to the head coil and adjustable to fit each participant. In multi-excitation MRE, vibrations are applied separately with the LR actuator in addition to the typical pillow driver for AP excitation via an active pneumatic driver (Resoundant, Inc., Rochester, MN), with each vibration being applied during a separate scan. All vibrations were applied at 50 Hz.

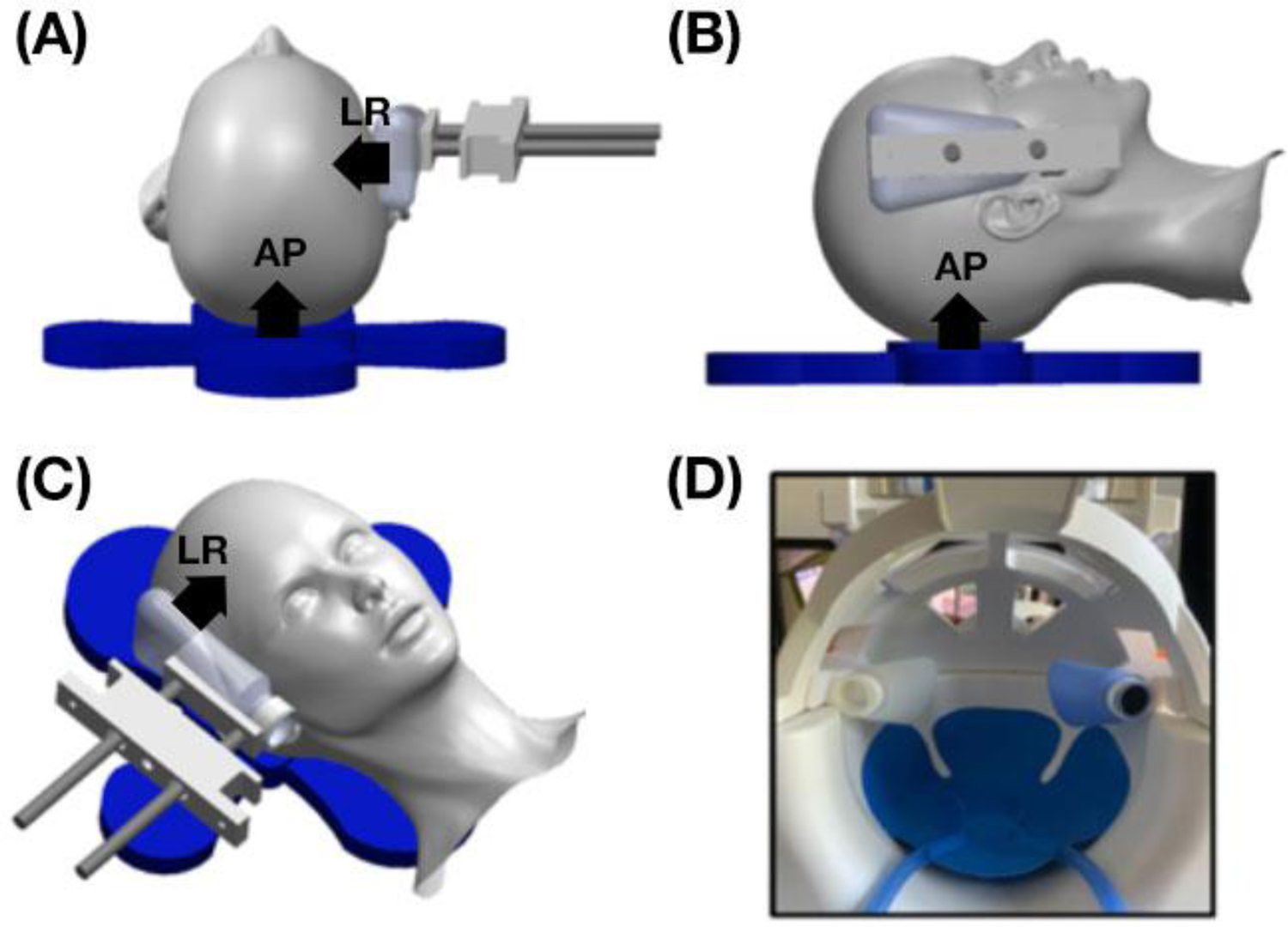

Figure 1:

Schematic of the multi-excitation actuator design which includes a pillow driver for anterior-posterior excitation and a custom 3D printed left-right actuator. A picture of the drivers inside the 20-channel head coil is also shown. The design allows the actuator to rest against the side of the subject’s head and is adjustable for different head sizes. Actuator directions (AP and LR) are indicated by arrows in (A)-(C).

Each of the two MRE acquisitions with either LR or AP excitation used a 3D multiband, multishot spiral sequence [41] to encode full vector displacement fields in the brain. Imaging parameters included: 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm3 isotropic resolution; field-of-view = 240 × 240 mm2; 64 slices; repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 2240/76 ms.

Additional scans in the MRI protocol included diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) acquisitions to estimate fiber direction and a T1-weighted anatomical image to localize WM tracts. The DTI acquisitions used a simultaneous multislice EPI sequence with the following parameters: field-of-view = 240 × 210 mm2; 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm2 resolution; 92 slices; TR/TE = 3520/95.2 ms; b-values = 1500 & 3000 s/mm2; directions = 128. The two DTI scans were acquired with opposite phase encoding direction – one in the anterior-posterior direction and the other in the posterior-anterior direction – which were combined to correct for distortions by applying TOPUP in FSL [42]. We used FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT) [43] to register the DTI images to MRE space, and the diffusion gradient directions for each image were rotated according to this registration to correct for motion in DTI data [44]. These data were processed using the FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox (FDT) from FMRIB’s Software Library (FSL) [45] to extract fractional anisotropy (FA) and primary eigenvector (V1). T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired with an MPRAGE sequence having the following parameters: field-of-view = 256 × 256 mm2; slices = 176; TR/TE/inversion time (TI) = 2300/2.32/900 ms; 0.9 × 0.9 × 0.9 mm3 isotropic resolution.

2.2. Transversely Isotropic Nonlinear Inversion

Shear wave displacement fields were calculated by subtracting MRE phase images obtained with opposite-polarity motion encoding gradients, unwrapping phase with FSL PRELUDE, and temporally Fourier filtering to isolate the harmonic component of interest. We then used both AP and LR wave motion fields and the primary eigenvector from DTI, which is assumed to be the fiber direction defining material symmetry, to estimate a single set of anisotropic material parameters with TI-NLI, as illustrated schematically in Figure 2. The latter returns spatial maps of three NITI model parameters describing the mechanical behavior of viscoelastic, fiber-reinforced tissue: the complex-valued substrate shear modulus (G = G2), real-valued shear anisotropy (ϕ = G1/G2 − 1), and real-valued tensile anisotropy (ζ = E1/E2 – 1). Here, shear modulus is denoted by G while Young’s modulus is denoted by E, with subscript 1 indicating the direction of fiber orientation, or the direction normal to the plane of isotropy, while subscript 2 indicates the direction orthogonal to the fiber within the plane of isotropy. In a coordinate system where the fiber is in the x1 direction in standard Voigt notation, the relationship between the components of the rank 2 symmetric stress tensor, σ, and strain tensor, ϵ, is given by

| (7) |

The components of the elasticity matrix are expressed in Eqs. (8–13),

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Here, κ represents the bulk modulus, which describes “isotropic compressibility” and is set to a large value to obtain near incompressibility. The model accommodates slow (“pure shear) and fast (“quasi-shear”) shear waves, predicted and observed in transversely isotropic materials [23,46], as well as the very fast acoustic (longitudinal, or compression) wave.

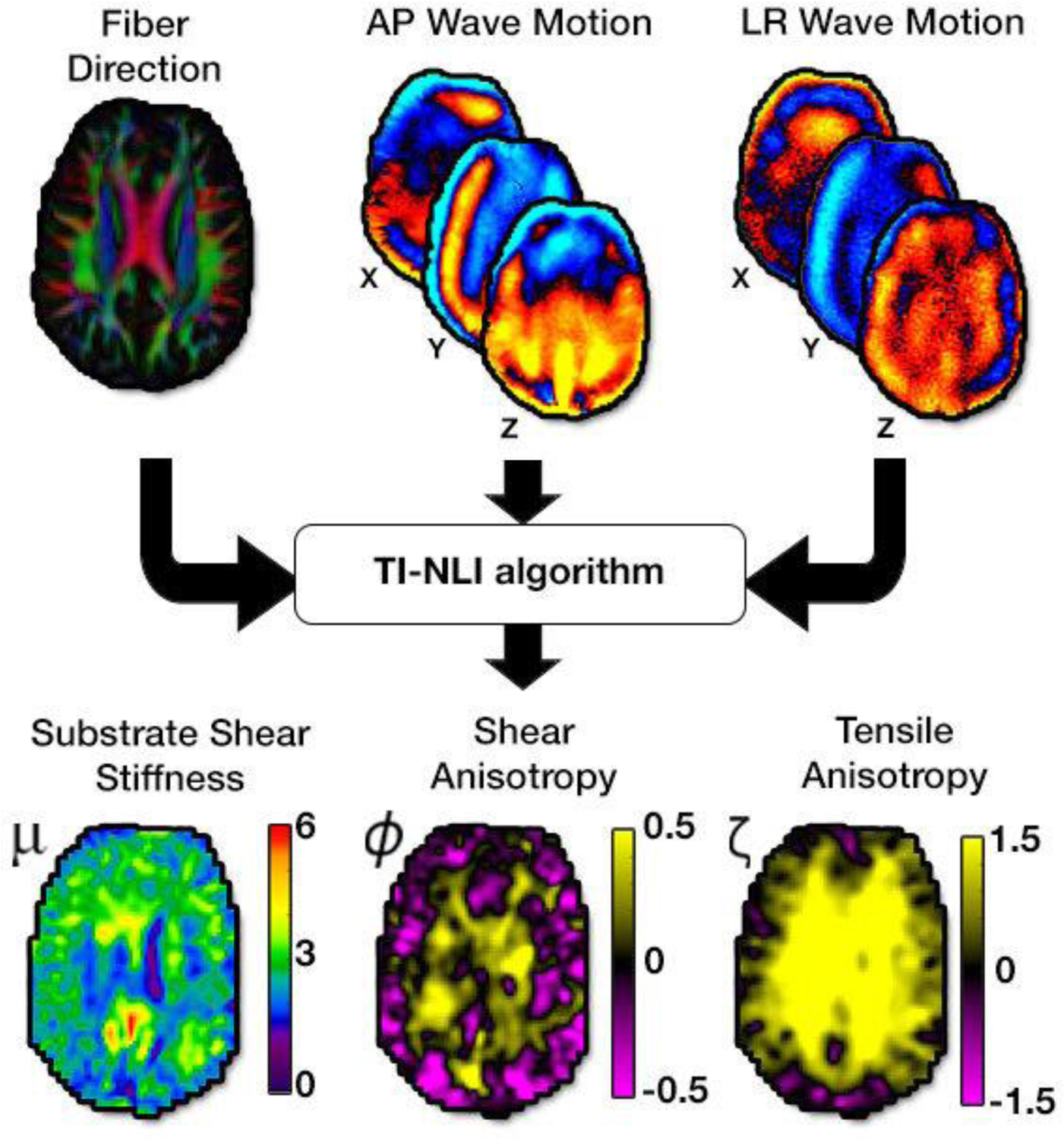

Figure 2:

MRE (AP and LR wave motion) and DTI (fiber direction from first eigenvector) images are input data to the transversely isotropic, nonlinear inversion algorithm (TI-NLI) to estimate the three anisotropic parameters: substrate shear modulus, μ, shear anisotropy, ϕ, and tensile anisotropy, ζ.

TI-NLI is a finite element-based optimization algorithm that involves solving two discrete problems: a “forward problem” and an “inverse problem” [47]. The forward problem calculates expected displacement fields from an estimated set of material properties. The inverse problem then updates the unknown mechanical property distribution based upon the differences between the calculated displacement fields from the forward problem and the actual acquired displacement fields. In this way, TI-NLI estimates the complex-valued substrate shear modulus, G = G′ + G″, where G′ and G″ are the substrate storage and loss modulus, respectively. Here we report the substrate shear stiffness, [4], which reflects the square of the wave speed in a viscoelastic material and is commonly reported in the MRE literature. In this model, with real-valued ϕ and ζ, the damping ratio is isotropic, defined by ξ = G″/2G′ [28].

2.3. Analysis:

We determined the average anisotropic properties in gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM), as well as in several individual white matter tracts. Segmentation of GM and WM from the T1-weighted images was performed with FSL FAST (FMRIB’s Automated Segmentation Tool) and registered to MRE space using FLIRT [43]. We generated masks of individual WM tracts including the corpus callosum (CC), corona radiata (CR), superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), forceps major (FM1), and forceps minor (FM2) using two WM atlases in MNI space [48,49]. Each tract region was registered to MRE space using FSL FLIRT and thresholded with DTI FA values above 35% to create binary masks. Additionally, we examined the three major parts of the CC – the genu, body, and splenium – to investigate heterogeneity within an individual tract.

We determined whether anisotropic properties differed between ROIs. Differences in each of μ, ϕ, and ζ between global WM and gray matter (GM) were tested using paired t-tests. Whether WM tracts differed in anisotropic properties was tested using repeated measures ANOVAs with post-hoc Tukey tests (with correction for multiple comparisons) to determine if differences between individual pairs of tracts were statistically significant. We additionally examined repeatability of extracted properties via ten measurements in a single volunteer, and compared variability from repeated measures with the variability in the overall sample population for each of μ, ϕ, and ζ. We tested whether these variabilities were significantly different across all WM tract ROIs with a paired t-test for each parameter. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP statistical software v.16.0

3. Results

3.1. Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of White Matter Tracts

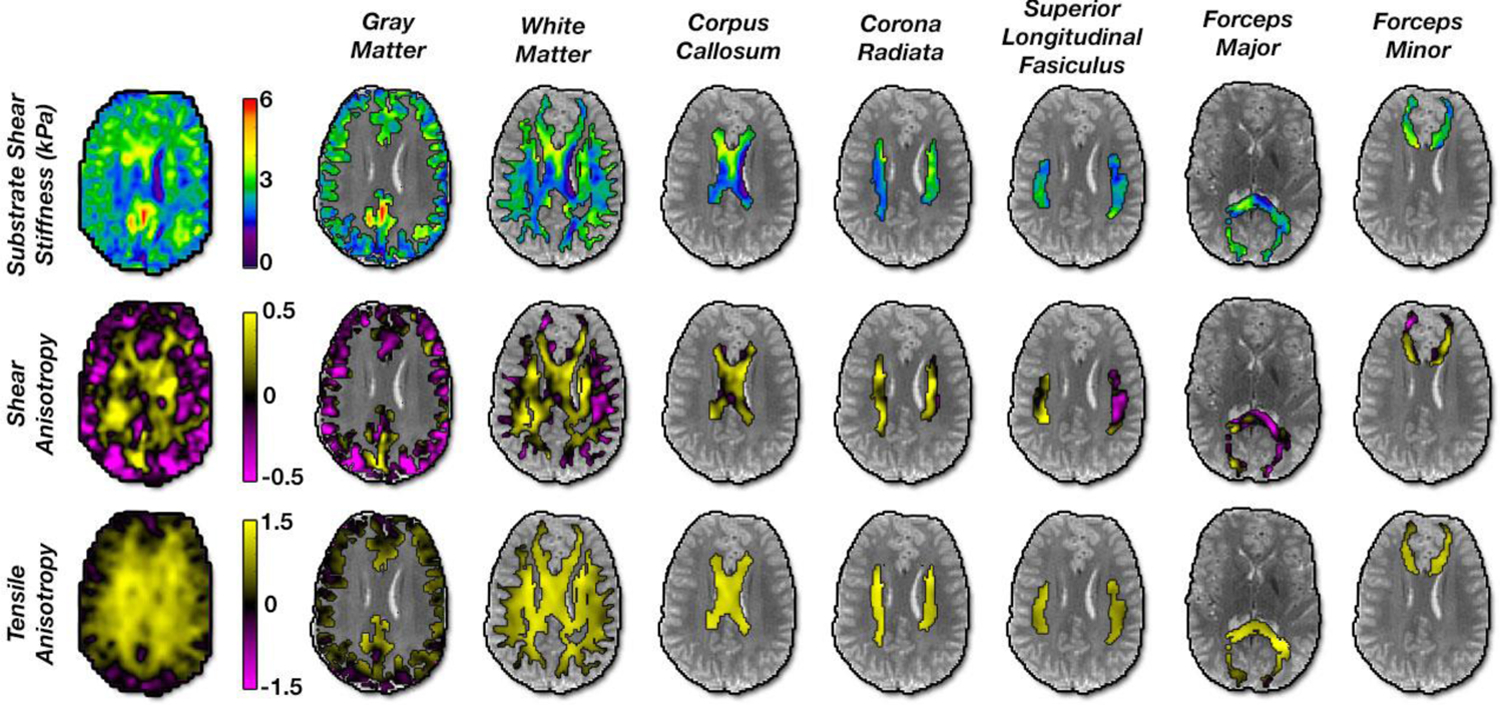

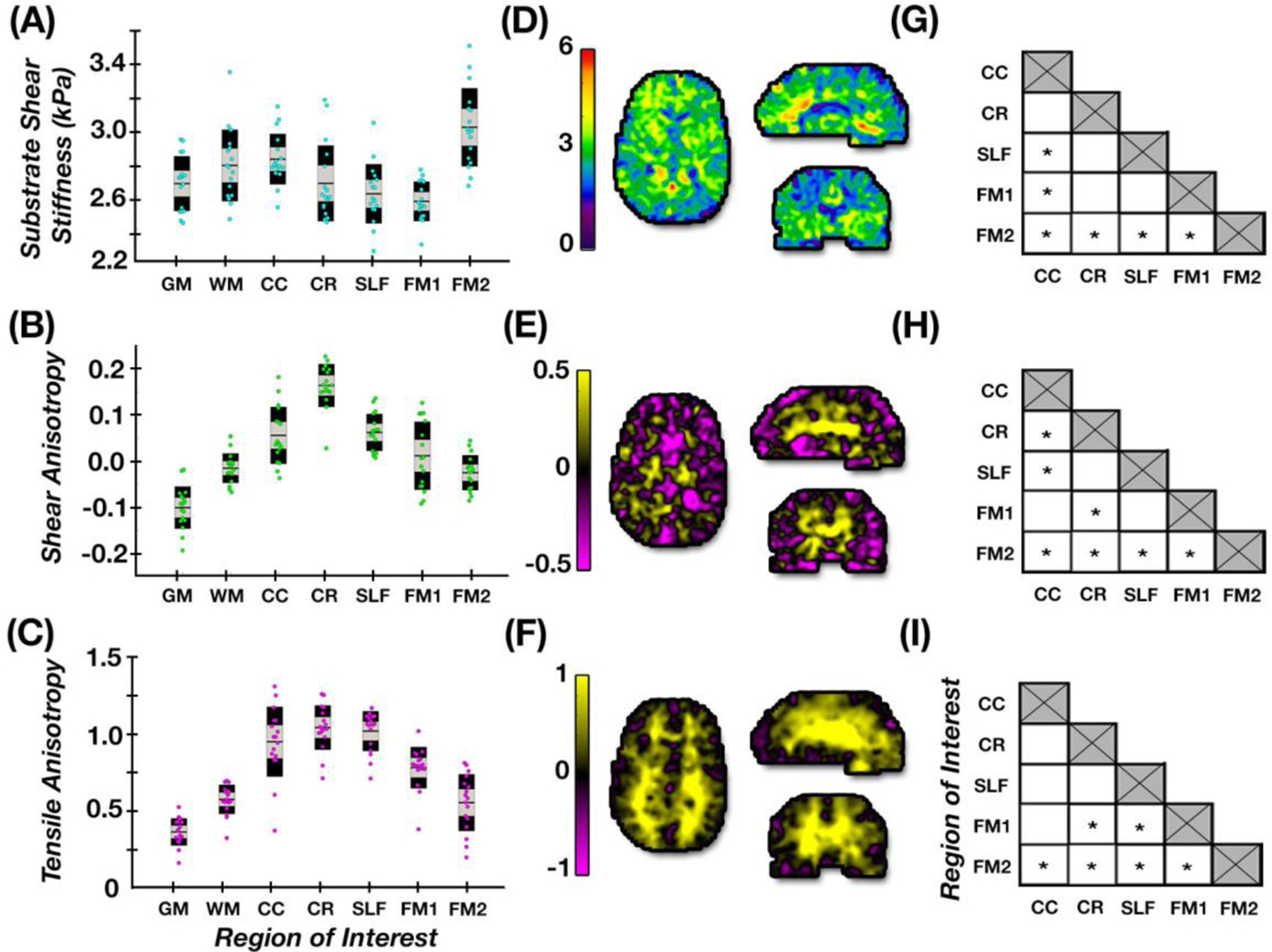

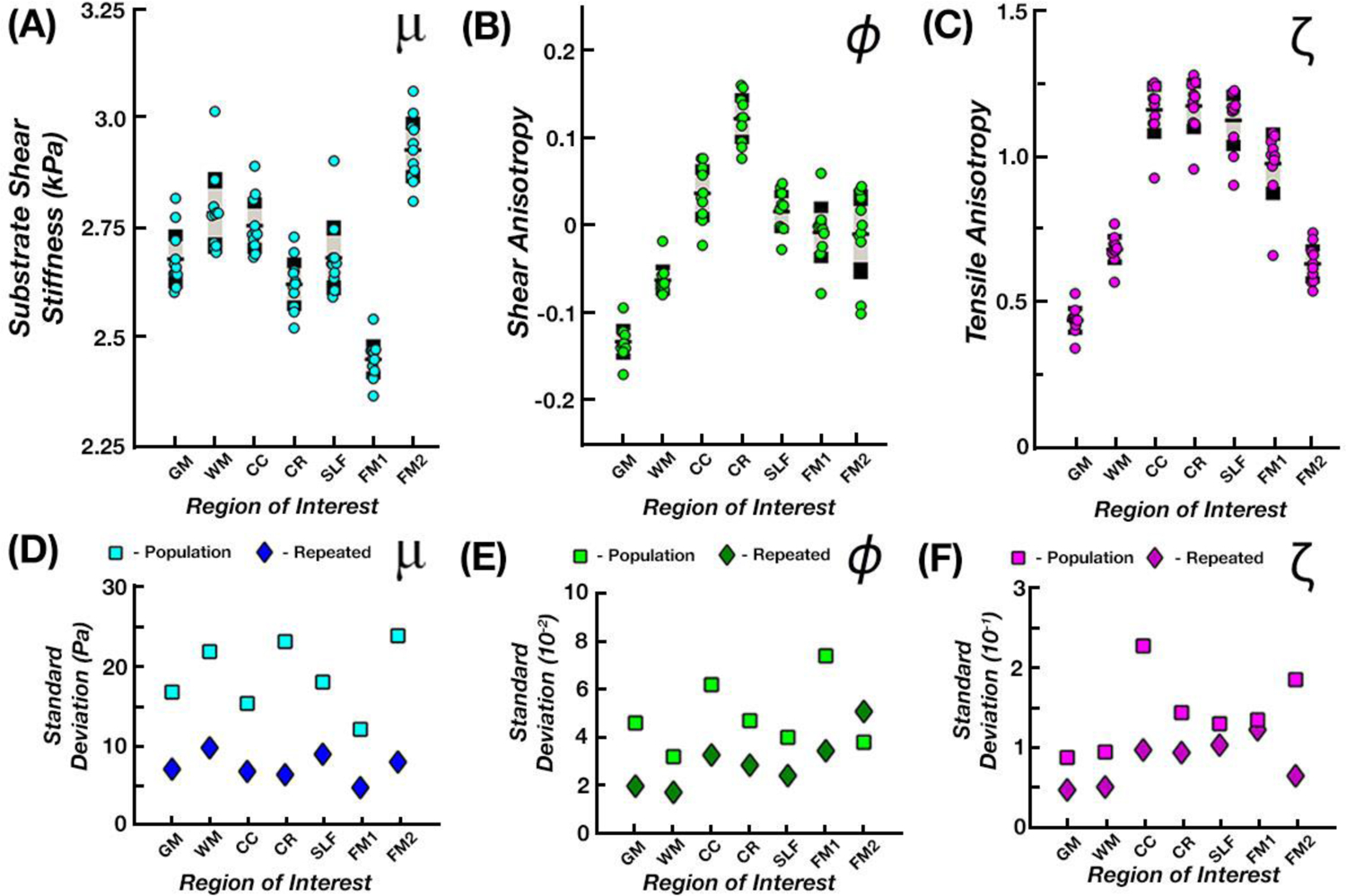

Figure 3 illustrates estimated anisotropic parameters – μ, ϕ, and ζ – and their distribution in selected ROIs: GM, WM, and the individual WM tracts of the CC, CR, SLF, and forceps major and minor. Figure 4 presents estimates of μ, ϕ, and ζ in our population of young adults in each of these ROIs. The overall WM region exhibited an average ϕ = −0.016 ± 0.032 and average ζ = 0.580 ± 0.095, which were significantly greater than gray matter (p < 0.05), where ϕ = −0.101 ± 0.046 and ζ = 0.367 ± 0.088. Individual white matter tracts demonstrated mostly positive shear anisotropy, with ϕ ranging from −0.026 to 0.164, and positive tensile anisotropy, with ζ ranging from 0.559 to 1.049. Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed each of the parameters significantly differed between WM tracts (p < 0.05). CR exhibited the largest anisotropy parameters, while forceps minor exhibited the smallest. Baseline shear modulus (μ) values for individual tracts ranged from 2.57 to 3.02 kPa. Figure 4 also shows how each tract differs from the others for each property, with significant differences likely indicating differences in tract microstructure. In particular, the forceps major had significant differences in all properties relative to the other WM tracts.

Figure 3:

Maps of estimated anisotropic parameters in the human brain in a representative slice for each ROI used in this study: gray matter, white matter, corpus callosum, corona radiata, superior longitudinal fasciculus, forceps major, and forceps minor.

Figure 4:

(A-C) Average parameter estimates for each brain ROI in healthy young adults; (D–F) representative axial, sagittal, and coronal slices of each property; (G-I) differences between individual tracts properties with significant differences denoted by * (p < 0.05).

3.2. Measurement Repeatability

Figure 5 presents the repeatability of the anisotropic parameter estimates in one subject scanned ten times. The μ, ϕ, and ζ parameter estimates were relatively stable with μ standard deviations ranging from 0.05 to 0.10 kPa, ϕ standard deviations ranging from 0.017 to 0.051, and ζ standard deviation ranging from 0.048 to 0.123. Across the three parameters, μ appears to be the most repeatable of the three measures. The variability of properties in the repeated measures were significantly lower than the variability in the population sample (p < 0.05), where μ standard deviations ranged from 0.12 to 0.24 kPa, ϕ standard deviations ranged from 0.032 to 0.074, and ζ standard deviations ranged from 0.088 to 0.227. Comparison of these variabilities is presented in Table 2.

Figure 5:

(A-C) Average parameter estimates for the single subject repeated data set were obtained within each ROI and examined to analyze repeatability. (D-F) Variability measures (standard deviation) of the repeated data set are plotted against those from the entire population (repeated data denoted by the darker symbol color).

Table 2:

Standard deviations of the three anisotropic parameters, μ, ϕ, and ζ, between the population and repeated subject data sets.

| Subject Group |

GM | WM | CC | CR | SLF | F. Major | F. Minor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ (kPa) | Population | 0.167 | 0.218 | 0.153 | 0.231 | 0.180 | 0.120 | 0.238 |

| Repeated | 0.070 | 0.097 | 0.067 | 0.063 | 0.089 | 0.047 | 0.079 | |

| ϕ | Population | 0.046 | 0.032 | 0.062 | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.074 | 0.380 |

| Repeated | 0.020 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.035 | 0.051 | |

| ζ | Population | 0.088 | 0.095 | 0.227 | 0.144 | 0.13 | 0.135 | 0.185 |

| Repeated | 0.048 | 0.051 | 0.100 | 0.094 | 0.103 | 0.122 | 0.660 |

3.3. Tract Heterogeneity

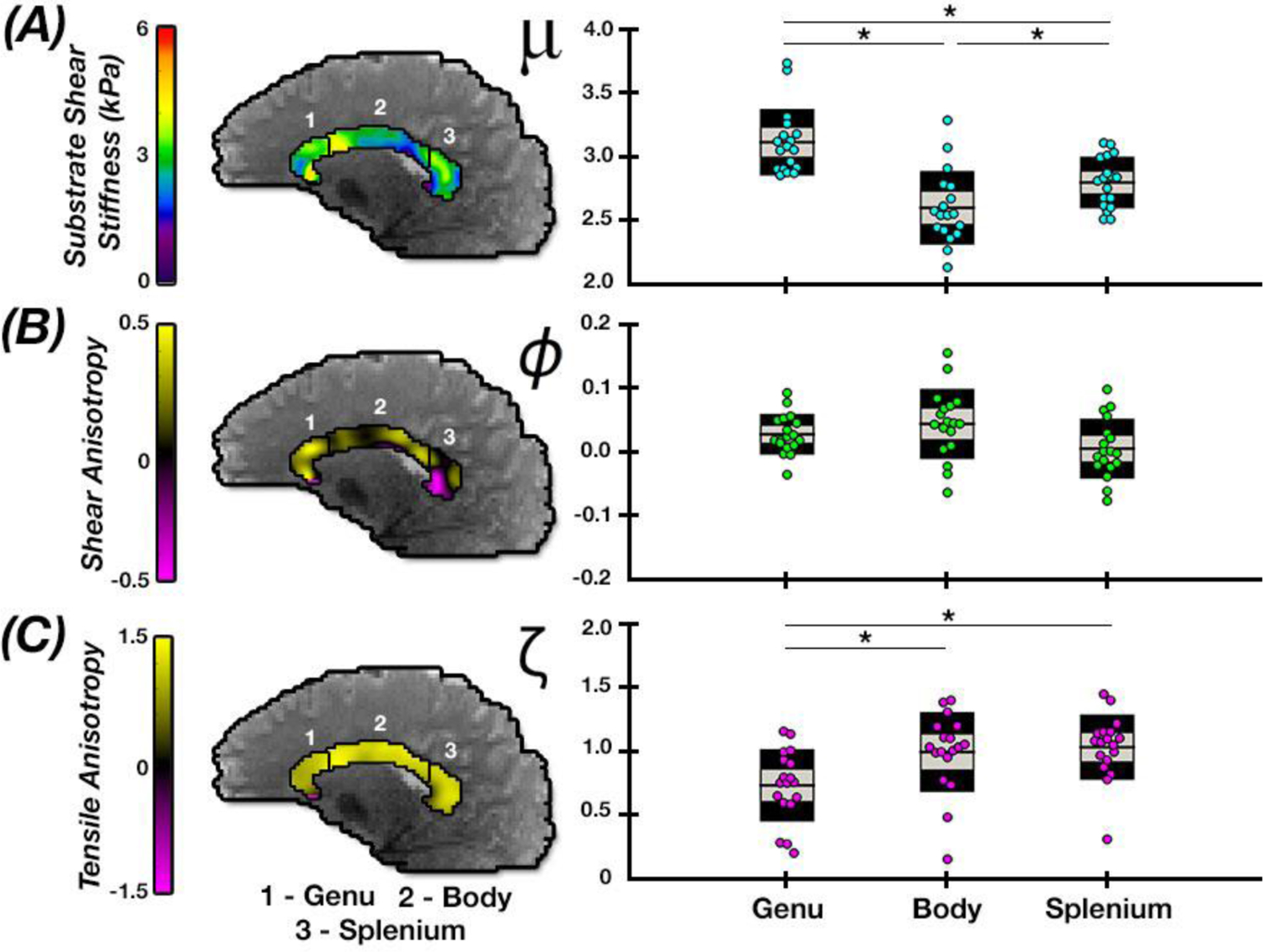

Figure 6 shows anisotropic properties of subregions of the CC including the genu, body, and splenium to illustrate sensitivity of TI-NLI to microstructural differences that exist within a single tract. We found significant differences (p < 0.05) between all three subtracts for μ, ranging from the highest stiffness in the genu (3.09 kPa) to the lowest in the body (2.60 kPa). While no significant variation occurred in ϕ between tracts, we found significant differences (p < 0.05) in ζ, including between the genu (0.70) and body (1.03) and between genu and the splenium (1.09).

Figure 6:

Comparison of anisotropic parameter estimates in subregions of the corpus callosum: genu, body, and splenium. Significant differences in properties between regions denoted by * (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this work, we quantified the anisotropic properties of individual WM tracts within the healthy human brain using multi-excitation MRE and TI-NLI. We identified significant differences in anisotropic parameters, μ, ϕ, and ζ, between tracts, and found the method is sensitive to expected microstructural differences throughout WM. We also illustrated the robust nature of these measurements through calculations of parameter repeatability at the tract level. Additionally, we demonstrated the capacity of TI-NLI to capture heterogeneity within WM tracts through analyses of the corpus callosum.

Using ten data sets collected from a single subject, we quantified repeatability of TI-NLI property estimates that incorporate displacement data from the custom pneumatic multi-excitation actuator. Though previous experiments have been performed with an actuator that generated LR excitations, these data produced less repeatable results [14], likely due to unreliable contact between the actuator and the skull. With our improved multi-excitation MRE yielding improved data quality and richness with which to represent the NITI material model [26], we produced repeatable measures of anisotropic parameters from TI-NLI. Overall, the repeatability of these measurements compared favorably with those found in WM with isotropic MRE previously reported by Johnson, et al. [27]. This result suggests the reduced model-data mismatch achieved by using a more appropriate WM model offsets the added computational complexity of a two-fold increase in the number of recovered parameters (four parameters in TI-NLI: storage modulus, loss modulus, shear anisotropy, tensile anisotropy) compared to isotropic approaches (two parameters: storage modulus and loss modulus).

Analysis of technique repeatability was performed by evaluating standard deviations of ROI parameter averages in the repeated measures from a single-subject data set. However, other studies evaluating repeatability of MRE measures use coefficient of variation (CV), which reports standard deviation relative to the mean in a group of samples. CV of μ measures reported in this study was highly repeatable with a range of 1.9 – 3.3%. The value is similar to other studies that analyzed repeatability of MRE isotropic shear stiffness within different regions of the brain, including cerebral lobes reported by Murphy, et al. (1.1 – 4.4%) [30], subcortical gray matter structures reported by Johnson, et al. (1.4 – 7.1%) [31], and hippocampal subfields reported by Delgorio, et al. (3.8 – 7.4%) [11]. CV is not an appropriate measure for evaluating the anisotropy parameters of NITI since the interpretation of CV should not significantly change by adding a numerical constant to the equation (this results in a relative change in variance though not actual variance itself [50]). As the definitions of both ϕ and ζ include subtraction of a constant, we instead reported just the standard deviation alone. When comparing variability in the repeated measures relative to variability in our sample of healthy young adults, we found significantly lower variation in the repeated subject data than across subjects. From this analysis, we conclude our measures likely reflect true tract properties rather than random measurement error, an outcome which is supported further by the significantly different parameters between tracts across all subjects. Additionally, through analyses of realistic simulated data sets, the TI-NLI method has previously provided accurate estimations of μ, ϕ and ζ, supporting the accuracy of the measurements found in this study [28,29].

When examining the average anisotropic parameter values for each tract and comparing gray and white matter estimates, we found our properties agreed approximately with previous in vivo and ex vivo measurements. Additionally, we observed that substrate shear stiffness of white matter was substantially lower than shear stiffness estimated from an isotropic material model, as shown in Johnson, et al. [27], who measured WM shear stiffness at 3.30 ± 0.35 kPa compared to 2.79 ± 0.22 kPa of substrate shear stiffness measured in this study. Comparison of individual tracts including the CC (3.45 kPa vs. 2.83 kPa current) and CR (3.72 kPa vs. 2.68 kPa current) also followed this trend as two regions with high levels of anisotropy within WM. These differences in stiffness estimates are likely due to use of the isotropic model in previous works because isotropic estimates of fibrous WM tracts recover an average of stiffnesses parallel and perpendicular to the tract, weighted by the proportions of wave energy in slow and fast shear waves. The anisotropic model recovers a lower substrate shear modulus, and faster waves along the fibers are reflected by ϕ,ζ > 0. We note that shear anisotropy alone is not sufficient to describe this difference between parameter measures, and tensile anisotropy also affects shear wavelength depending on wave propagation and polarization directions [25]. Estimated stiffness of GM by Johnson, et al, of 2.40 kPa [27] was similar to our estimated substrate stiffness of 2.69 kPa, which is expected given the more isotropic nature of GM.

The degree of shear anisotropy in WM has been debated and discussed in the literature [51]. Here, we found low levels of shear anisotropy in the overall WM and in individual WM tracts, which agrees overall with other MRE studies. Schmidt, et al. [52] found shear anisotropy in the white matter of the porcine brain to be approximately 25–35% through ex vivo MRE analysis and approximately 10–15% using dynamic shear testing. Similarly, Feng, et al. [22] analyzed ex vivo lamb brain samples using dynamic shear testing and measured a higher WM shear anisotropy of approximately 40%. While these previous findings are consistent with the work reported here in terms of identifying WM shear anisotropy of a similar magnitude, differences may be attributed to use of ex vivo samples collected at frequencies of 100–300 Hz for MRE and 20–30 Hz for dynamic shear testing, while our study was performed in vivo and at 50 Hz.

Tensile anisotropy, on the other hand, is a parameter less commonly studied in WM. In addition to shear anisotropy found in the tissue, Budday, et al. [51] estimated low levels of tensile anisotropy (~5–10%) in ex-vivo tissue during tension, though not nearly at the levels found in our study (~96%). Alternatively, Velardi, et al. [53] found high tensile anisotropy of 1.77 (~177%) recorded during ex vivo evaluation of the CC. The relatively strong tensile anisotropy, when compared to shear anisotropy, may arise from differences in how the axons and the surrounding extra-axonal matrix of the WM respond to loading during shear wave propagation. The bundles of axons and their myelin sheaths form a mechanically complex system that becomes even more complicated when including the various astrocyte and oligodendrocyte populations [54]. Higher anisotropy in tension than in shear may be explained by relatively stiff myelinated axonal fibers acting as a reinforcement structure when stretched axially (in the direction of fiber alignment). In tension, strains in the fibers and surrounding matrix must be equal. However, in shear deformations involving displacements either parallel or perpendicular to aligned fibers, the fibers need not deform as much as the connective matrix. The behavior of the tissue in shear is thus not determined solely, or even primarily, by fiber mechanical properties, but by interactions of the fibers with surrounding matrix. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in WM may in fact reinforce the tissue in deformations involving displacements perpendicular to the fibers, thereby increasing substrate shear stiffness and reducing the overall shear anisotropy of the tissue.

Most MRE studies incorporating anisotropic inversion methods focus primarily on the shear components of anisotropy, μ and ϕ [16,18]. These investigations thus inherently assume existence of only slow shear waves in MRE displacement data and neglect the effects of fast shear waves which involve fiber stretching. Sensitivity to noise in recovering tensile anisotropy has been cited as a motivation for using a simplified model [18]. However, given that both slow and fast shear waves have been observed in transversely isotropic tissue-mimicking phantoms [55] and simulations, including tensile anisotropy as a parameter appears to be necessary when estimating the anisotropic viscoelastic parameters of fibrous tissues, even if the shear anisotropy is relatively small. In the current approach, excluding ζ in these analyses likely leads to increases in model-data mismatch, and thus, additional uncertainty and overestimation in other parameters, along with the missed opportunity to examine a potentially useful biomarker.

Brain tissue is known to be heterogenous in composition with WM comprising axons, astrocytes, myelin, and various extracellular matrix components. In addition, myelinated axonal fibers, the likely basis of mechanical anisotropy in WM, have been shown to vary in size, with different amounts of these fibers being present within regions of individual tracts, such as the CC [56,57]. High levels of heterogeneity in WM axon properties have been recorded with respect to axon diameter, axon density, and inter-axon distance. Large diameter axons potentially possess a higher structural stiffness than thinner axons; and therefore, the distribution of these thin and thick axons within the tissue likely affects its mechanical response. The three CC subtracts – genu, body, and splenium – have revealed different ratios of thin and thick axons, which also correlates with levels of myelination in the tissue [56]. Within the CC tracts, we found heterogeneity in the anisotropic parameters between multiple regions of the tract, including the genu, the body, and the splenium. In the genu, we found the highest estimates of μ and lowest estimates of ζ, while the body exhibited the lowest estimates of μ and highest estimates of ζ. Johnson, et al, found the genu to have the lowest stiffness of the CC tracts using isotropic MRE a similar analysis [27], while we found the genu to have the highest substrate shear stiffness. This discrepancy is likely due to the low anisotropy in the genu compared to the body and splenium, which can appear as higher apparent isotropic stiffness.

The heterogeneity exhibited between these regions of the CC may exist because of variation in the microstructure of the CC, primarily the axon diameter distribution [56–58]. Average axon thickness in the CC is lowest within the genu and highest within the body [59], consistent with our estimates of ζ in these tracts. The potential relationship between tensile anisotropy and average axon thickness indicates an increased structural rigidity caused by thicker axons, which possess relatively thin myelin sheaths, and therefore a smaller area fraction of myelin to axon within the tissue [60]. Additionally, myelin content may have a positive relationship with μ, as an increase in myelin indicates larger density of oligodendrocytes, thereby creating a more rigid structure perpendicular to axonal direction. Future work is needed to confirm relationships between anisotropic mechanical properties and WM tract microstructure, but these trends suggest anisotropic MRE is sufficiently sensitive to detect variations in tissue microstructure.

Though we have shown in this study that multi-excitation MRE and TI-NLI are effective tools for calculating the anisotropic mechanical properties of white matter, there are several limitations to this study. In multi-excitation MRE, two excitations are acquired separately and are susceptible to small subject movements and data, even with co-registration, which may affect the accuracy and repeatability of the estimated parameters in TI-NLI. Additionally, using the assumption of an NITI material model, TI-NLI uses only a single fiber direction at any voxel, which does have the ability to model crossing fibers in white matter, leading to model-data mismatch in these areas. Model-data mismatch may also be the source of relatively small negative anisotropy observed regions in gray matter regions where the DTI eigenvector is noisy and may not reflect mechanical directionality. While TI-NLI has been validated through a series of realistic simulations [28,29], studies on ex vivo tissue or comparisons with other mechanical tests have not yet been performed. Finally, it is not yet known if anisotropic mechanical properties from MRE are related to metrics from diffusion MRI, which should be investigated in future studies with larger sample sizes.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we used multi-excitation MRE to acquire full-field displacement data during shear wave propagation in the human brain, and used TI-NLI to estimate spatial maps of the anisotropic viscoelastic material parameters in a NITI constitutive model. We observed a substrate shear stiffness that was slightly lower than the measured isotropic shear stiffness in prior studies, along with modest shear anisotropy, ϕ, in agreement with past findings. Importantly, the study also considered tensile anisotropy, ζ, as a parameter when representing WM in MRE; the tensile anisotropy in healthy brain appeared to be substantially higher than its shear anisotropy. One of the primary limitations of the current method is parameter estimation in GM and the consequences for parameter estimates in neighboring WM. Due to the microstructure of GM, the NITI model with a dominant “fiber direction” may not appropriately describe the tissue behavior, or may be difficult to determine from DTI data given the low FA in GM; this may underlie estimates of negative shear and tensile anisotropy in GM, as well as at the boundaries of WM. Future studies will investigate the use of multi-excitation MRE and TI-NLI to examine anisotropic mechanical properties of WM in aging, neurological disease, and traumatic brain injury.

Table 1:

Means and standard deviations of the three anisotropic parameters, μ, ϕ, and ζ, for each of seven ROIs across the entire population sample.

| GM | WM | CC | CR | SLF | FM1 | FM2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ (kPa) | 2.68 ± 0.17 | 2.79 ± 0.22 | 2.83 ± 0.15 | 2.68 ± 0.23 | 2.62 ± 0.18 | 2.57 ± 0.12 | 3.02 ± 0.24 |

| ϕ | −0.101 ± 0.046 | −0.016 ± 0.032 | 0.056 ± 0.062 | 0.164 ± 0.047 | 0.062 ± 0.040 | 0.011 ± 0.074 | −0.026 ± 0.038 |

| ζ | 0.367 ± 0.088 | 0.580 ± 0.095 | 0.956 ± 0.227 | 1.049 ± 0.144 | 1.025 ± 0.130 | 0.787 ± 0.135 | 0.559 ± 0.185 |

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided National Institutes of Health grants R01-EB027577 and R01-AG058853 and National Science Foundation grant CMMI-1727412.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Bibliography

- [1].Streitberger K-J, Sack I, Krefting D, Pfüller C, Braun J, Paul F, and Wuerfel J, 2012, “Brain Viscoelasticity Alteration in Chronic-Progressive Multiple Sclerosis,” PLoS One, 7(1), p. e29888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mesfin FB, and Taylor RS, 2018, Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI), StatPearls Publishing. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aoki Y, Inokuchi R, Gunshin M, Yahagi N, and Suwa H, 2012, “Diffusion Tensor Imaging Studies of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Meta-Analysis,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 83(9), pp. 870–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Manduca A, Oliphant TEE, Dresner MAA, Mahowald JLL, Kruse SAA, Amromin E, Felmlee JPP, Greenleaf JFF, and Ehman RLL, 2001, “Magnetic Resonance Elastography: Non-Invasive Mapping of Tissue Elasticity,” Med. Image Anal, 5(4), pp. 237–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mariappan YK, Glaser KJ, and Ehman RL, 2010, “Magnetic Resonance Elastography: A Review,” Clin. Anat, 23(5), pp. 497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sandroff BM, Johnson CL, and Motl RW, 2017, “Exercise Training Effects on Memory and Hippocampal Viscoelasticity in Multiple Sclerosis: A Novel Application of Magnetic Resonance Elastography,” Neuroradiology, 59(1), pp. 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wuerfel J, Paul F, Beierbach B, Hamhaber U, Klatt D, Papazoglou S, Zipp F, Martus P, Braun J, and Sack I, 2010, “MR-Elastography Reveals Degradation of Tissue Integrity in Multiple Sclerosis,” Neuroimage, 49(3), pp. 2520–2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murphy MC, Curran GL, Glaser KJ, Rossman PJ, Huston J, Poduslo JF, Jack CR, Felmlee JP, and Ehman RL, 2012, “Magnetic Resonance Elastography of the Brain in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Initial Results,” Magn. Reson. Imaging, 30(4), pp. 535–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Murphy MC, Huston J, Jack CR, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Felmlee JP, and Ehman RL, 2011, “Decreased Brain Stiffness in Alzheimer’s Disease Determined by Magnetic Resonance Elastography,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 34(3), pp. 494–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lipp A, Trbojevic R, Paul F, Fehlner A, Hirsch S, Scheel M, Noack C, Braun J, and Sack I, 2013, “Cerebral Magnetic Resonance Elastography in Supranuclear Palsy and Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease,” NeuroImage Clin, 3, pp. 381–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Delgorio PL, Hiscox LV, Daugherty AM, Sanjana F, Pohlig RT, Ellison JM, Martens CR, Schwarb H, McGarry MDJ, and Johnson CL, 2021, “Effect of Aging on the Viscoelastic Properties of Hippocampal Subfields Assessed with High-Resolution MR Elastography,” Cereb. Cortex, pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hiscox LV, Schwarb H, McGarry MDJ, and Johnson CL, 2021, “Aging Brain Mechanics: Progress and Promise of Magnetic Resonance Elastography,” Neuroimage, 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sack I, Streitberger KJ, Krefting D, Paul F, and Braun J, 2011, “The Influence of Physiological Aging and Atrophy on Brain Viscoelastic Properties in Humans,” PLoS One, 6(9), p. e23451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Anderson AT, Van Houten EEW, McGarry MDJ, Paulsen KD, Holtrop JL, Sutton BP, Georgiadis JG, and Johnson CL, 2016, “Observation of Direction-Dependent Mechanical Properties in the Human Brain with Multi-Excitation MR Elastography,” J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater, 59, pp. 538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sinkus R, Tanter M, Catheline S, Lorenzen J, Kuhl C, Sondermann E, and Fink M, 2005, “Imaging Anisotropic and Viscous Properties of Breast Tissue by Magnetic Resonance-Elastography,” Magn. Reson. Med, 53(2), pp. 372–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Green MA, Geng G, Qin E, Sinkus R, Gandevia SC, and Bilston LE, 2013, “Measuring Anisotropic Muscle Stiffness Properties Using Elastography,” NMR Biomed., 26(11), pp. 1387–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Romano A, Scheel M, Hirsch S, Braun J, and Sack I, 2012, “In Vivo Waveguide Elastography of White Matter Tracts in the Human Brain,” Magn. Reson. Med, 68(5), pp. 1410–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Babaei B, Fovargue D, Lloyd RA, Miller R, Jugé L, Kaplan M, Sinkus R, Nordsletten DA, and Bilston LE, 2021, “Magnetic Resonance Elastography Reconstruction for Anisotropic Tissues,” Med. Image Anal, 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Miller R, Kolipaka A, Nash MP, and Young AA, 2018, “Estimation of Transversely Isotropic Material Properties from Magnetic Resonance Elastography Using the Optimised Virtual Fields Method,” Int. j. numer. method. biomed. eng, 34(6), p. e2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Qin EC, Sinkus R, Geng G, Cheng S, Green M, Rae CD, and Bilston LE, 2013, “Combining MR Elastography and Diffusion Tensor Imaging for the Assessment of Anisotropic Mechanical Properties: A Phantom Study,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 37(1), pp. 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tweten DJDJ, Okamoto RJ, Schmidt JL, Garbow JR, and Bayly PV, 2015, “Estimation of Material Parameters from Slow and Fast Shear Waves in an Incompressible, Transversely Isotropic Material,” J. Biomech, 48(15), pp. 4002–4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Feng Y, Okamoto RJ, Namani R, Genin GM, and Bayly PV, 2013, “Measurements of Mechanical Anisotropy in Brain Tissue and Implications for Transversely Isotropic Material Models of White Matter,” J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater, 23, pp. 117–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schmidt JL, Tweten DJ, Benegal AN, Walker CH, Portnoi TE, Okamoto RJ, Garbow JR, and Bayly PV, 2016, “Magnetic Resonance Elastography of Slow and Fast Shear Waves Illuminates Differences in Shear and Tensile Moduli in Anisotropic Tissue,” J. Biomech, 49(7), pp. 1042–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Feng Y, Qiu S, Xia X, Ji S, and Lee C-H, 2017, “A Computational Study of Invariant I5 in a Nearly Incompressible Transversely Isotropic Model for White Matter,” J. Biomech, 57, pp. 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tweten DJ, Okamoto RJ, and Bayly PV, 2017, “Requirements for Accurate Estimation of Anisotropic Material Parameters by Magnetic Resonance Elastography: A Computational Study,” Magn. Reson. Med, 78(6), pp. 2360–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith DR, Guertler CA, Okamoto RJ, Romano AJ, Bayly PV, and Johnson CL, 2020, “Multi-Excitation Magnetic Resonance Elastography of the Brain: Wave Propagation in Anisotropic White Matter,” J. Biomech. Eng, 142(7), pp. 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Johnson CL, McGarry MDJ, Gharibans AA, Weaver JB, Paulsen KD, Wang H, Olivero WC, Sutton BP, and Georgiadis JG, 2013, “Local Mechanical Properties of White Matter Structures in the Human Brain,” Neuroimage, 79, pp. 145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McGarry M, Van Houten E, Guertler C, Okamoto R, Smith D, Sowinski D, Johnson C, Bayly P, Weaver J, and Paulsen K, 2021, “A Heterogenous, Time Harmonic, Nearly Incompressible Transverse Isotropic Finite Element Brain Simulation Platform for MR Elastography,” Phys. Med. Biol, 66(5), p. 055029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McGarry MDJ, Van Houten EEW, Sowinski D, Jyoti D, Smith D, Caban-Rivera DA, McIlvain G, Bayly P, Johnson CL, Weaver JB, and Paulsen K, 2021, “Mapping Heterogenous Anisotropic Tissue Mechanical Properties with Transverse Isotropic Nonlinear Inversion MR Elastography.,” “In Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Murphy MC, Huston J, Jack CR, Glaser KJ, Senjem ML, Chen J, Manduca A, Felmlee JP, and Ehman RL, 2013, “Measuring the Characteristic Topography of Brain Stiffness with Magnetic Resonance Elastography,” PLoS One, 8(12), p. e81668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Johnson CL, Schwarb H, D.J. McGarry M, Anderson AT, Huesmann GR, Sutton BP, and Cohen NJ, 2016, “Viscoelasticity of Subcortical Gray Matter Structures,” Hum. Brain Mapp, 37(12), pp. 4221–4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hiscox LV, Johnson CL, McGarry MDJ, Perrins M, Littlejohn A, van Beek EJR, Roberts N, and Starr JM, 2018, “High-Resolution Magnetic Resonance Elastography Reveals Differences in Subcortical Gray Matter Viscoelasticity between Young and Healthy Older Adults,” Neurobiol. Aging, 65, pp. 158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Arani A, Murphy MC, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Lake DS, Kruse SA, Jack CR, Ehman RL, and Huston J, 2015, “Measuring the Effects of Aging and Sex on Regional Brain Stiffness with MR Elastography in Healthy Older Adults,” Neuroimage, 111, pp. 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Murphy MC, Jones DT, Jack CR, Glaser KJ, Senjem ML, Manduca A, Felmlee JP, Carter RE, Ehman RL, and Huston J, 2015, “Regional Brain Stiffness Changes across the Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum,” NeuroImage. Clin, 10, pp. 283–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gerischer LM, Fehlner A, Köbe T, Prehn K, Antonenko D, Grittner U, Braun J, Sack I, and Flöel A, 2018, “Combining Viscoelasticity, Diffusivity and Volume of the Hippocampus for the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Neuroimage (Amst)., 18, p. 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Huesmann GR, Schwarb H, Smith DR, Pohlig RT, Anderson AT, McGarry MDJ, Paulsen KD, Wszalek TM, Sutton BP, and Johnson CL, 2020, “Hippocampal Stiffness in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Measured with MR Elastography: Preliminary Comparison with Healthy Participants,” NeuroImage. Clin, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schwarb H, Johnson CL, McGarry MDJ, and Cohen NJ, 2016, “Medial Temporal Lobe Viscoelasticity and Relational Memory Performance,” Neuroimage, 132, pp. 534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hiscox LV, Johnson CL, McGarry MDJ, Schwarb H, van Beek EJR, Roberts N, and Starr JM, 2020, “Hippocampal Viscoelasticity and Episodic Memory Performance in Healthy Older Adults Examined with Magnetic Resonance Elastography,” Brain Imaging Behav, 14(1), pp. 175–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Caban-Rivera DA, Smith DR, Okamoto RJ, McGarry MDJ, Williams LT, Guertler CA, McIlvain G, Sowinski D, Van Houten EEW, Paulsen KD, Bayly PV, and Johnson CL, 2021, “Multi-Excitation Actuator Design for Anisotropic Brain MRE,” Internation Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kailash K, Rifkin J, Ireland J, Okamoto R, and Bayly P, 2019, “Design And Evaluation Of A Lateral Head Excitation Device For MR Elastography Of The Brain,” Biomedical Engineering Society Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Johnson CL, Holtrop JL, Anderson AT, and Sutton BP, 2016, “Brain MR Elastography with Multiband Excitation and Nonlinear Motion-Induced Phase Error Correction,” 24th Annu. Meet. Interational Soc. Magn. Reson. Med Singapore, p. p 1951. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Andersson JLR, Skare S, and Ashburner J, 2003, “How to Correct Susceptibility Distortions in Spin-Echo Echo-Planar Images: Application to Diffusion Tensor Imaging,” Neuroimage, 20(2), pp. 870–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, and Matthews PM, 2004, “Advances in Functional and Structural MR Image Analysis and Implementation as FSL,” Neuroimage, 23 Suppl 1(SUPPL. 1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Leemans A, and Jones DK, 2009, “The B-Matrix Must Be Rotated When Correcting for Subject Motion in DTI Data,” Magn. Reson. Med, 61(6), pp. 1336–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJJ, Woolrich MW, and Smith SM, 2012, “Fsl.,” Neuroimage, 62(2), pp. 782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rouze NC, Wang MH, Palmeri ML, and Nightingale KR, 2013, “Finite Element Modeling of Impulsive Excitation and Shear Wave Propagation in an Incompressible, Transversely Isotropic Medium,” J. Biomech, 46(16), pp. 2761–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McGarry MDJ, Van Houten EEW, Johnson CL, Georgiadis JG, Sutton BP, Weaver JB, and Paulsen KD, 2012, “Multiresolution MR Elastography Using Nonlinear Inversion,” Med. Phys, 39(10), pp. 6388–6396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, Jiang L, Li X, Akhter K, Hua K, Faria AV, Mahmood A, Woods R, Toga AW, Pike GB, Neto PR, Evans A, Zhang J, Huang H, Miller MI, van Zijl P, and Mazziotta J, 2008, “Stereotaxic White Matter Atlas Based on Diffusion Tensor Imaging in an ICBM Template,” Neuroimage, 40(2), pp. 570–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hua K, Zhang J, Wakana S, Jiang H, Li X, Reich DS, Calabresi PA, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PCM, and Mori S, 2008, “Tract Probability Maps in Stereotaxic Spaces: Analyses of White Matter Anatomy and Tract-Specific Quantification,” Neuroimage, 39(1), p. 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Brown CE, 1998, “Coefficient of Variation,” Appl. Multivar. Stat. Geohydrology Relat. Sci, pp. 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Budday S, Sommer G, Birkl C, Langkammer C, Haybaeck J, Kohnert J, Bauer M, Paulsen F, Steinmann P, Kuhl E, and Holzapfel GA, 2017, “Mechanical Characterization of Human Brain Tissue,” Acta Biomater, 48, pp. 319–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schmidt JL, Tweten DJ, Badachhape AA, Reiter AJ, Okamoto RJ, Garbow JR, and Bayly PV, 2018, “Measurement of Anisotropic Mechanical Properties in Porcine Brain White Matter Ex Vivo Using Magnetic Resonance Elastography,” J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater, 79, pp. 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Velardi F, Fraternali F, and Angelillo M, 2006, “Anisotropic Constitutive Equations and Experimental Tensile Behavior of Brain Tissue,” Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol, 5(1), pp. 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Stassart RM, Möbius W, Nave KA, and Edgar JM, 2018, “The Axon-Myelin Unit in Development and Degenerative Disease,” Front. Neurosci, 12(JUL), p. 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bayly PV, and Garbow JR, 2018, “Pre-Clinical MR Elastography: Principles, Techniques, and Applications,” J. Magn. Reson, 291, pp. 73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Aboitiz F, Scheibel AB, Fisher RS, and Zaidel E, 1992, “Individual Differences in Brain Asymmetries and Fiber Composition in the Human Corpus Callosum,” Brain Res, 598(1–2), pp. 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Aboitiz F, Rodríguez E, Olivares R, and Zaidel E, 1996, “Age-Related Changes in Fibre Composition of the Human Corpus Callosum: Sex Differences.,” Neuroreport, 7(11), pp. 1761–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Aboitiz F, and Montiel J, 2003, “One Hundred Million Years of Interhemispheric Communication: The History of the Corpus Callosum,” Brazilian J. Med. Biol. Res, 36(4), pp. 409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lynn JD, Anand C, Arshad M, Homayouni R, Rosenberg DR, Ofen N, Raz N, and Stanley JA, 2021, “Microstructure of Human Corpus Callosum across the Lifespan: Regional Variations in Axon Caliber, Density, and Myelin Content,” Cereb. Cortex, 31(2), pp. 1032–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Paus T, and Toro R, 2009, “Could Sex Differences in White Matter Be Explained by g Ratio?,” Front. Neuroanat, 3(SEP), p. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Björnholm L, Nikkinen J, Kiviniemi V, Nordström T, Niemelä S, Drakesmith M, Evans JC, Pike GB, Veijola J, and Paus T, 2017, “Structural Properties of the Human Corpus Callosum: Multimodal Assessment and Sex Differences,” Neuroimage, 152, pp. 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]