Abstract

Comorbid psychiatric disorders in adults with ADHD are important because these comorbidities might complicate the diagnosis of ADHD and also worsen the prognosis. However, the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in adult ADHD varies according to the diagnostic tools used and the characteristics of target populations. The purpose of this review was to describe the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in adults with ADHD compared with adults without ADHD. Thirty-two studies published before August 2022 were identified and classified according to diagnosis of other psychiatric disorder in those with ADHD. The most frequent comorbid psychiatric disorder in the ADHD group was substance use disorder (SUD), followed by mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders. The prevalence of these four disorders was higher in the ADHD group, whether or not subjects were diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders. In addition, the diversity of ADHD diagnostic tools was observed. This also might have affected the variability in prevalence of comorbidities. Standardization of ADHD diagnostic tools is necessary in the future.

Introduction

ADHD(attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) is a common psychiatric disorder presenting persistent inattention and/or with hyperactivity/impulsivity [1], which is associated with considerable problems in personal, social, and occupational areas [2]. While ADHD is well studied in children, it is recently being studied in adults as well. According to a previous meta-analysis, 65% of children who were diagnosed with ADHD have persistent ADHD symptoms in adulthood [3]. In addition, the prevalence of ADHD in adults is known to reach 2.5% [4], which is moderate compared to its prevalence in children, which is about 5% [5].

Although comorbid psychiatric disorders are common in both adults and children, the comorbidity rate is higher in adults; as many as 80% of adults with ADHD are reported to have at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder [6–8]. In clinical adult ADHD samples, substance use disorder (SUD), mood disorder, anxiety disorder, and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) are the most common comorbid disorders [9, 10], and these mental disorders can adversely affect patient prognosis. Furthermore, research revealed that comorbid psychiatric disorders cause considerable functional impairment in individuals with ADHD and place a great burden on society [11].

For this reason, several cross-sectional studies have been conducted on various populations including clinical and general settings over 30 years to evaluate the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric conditions in adults with ADHD. However, the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders varied according to characteristics of the subjects, including country, race, gender, and other socioeconomic characteristics as well as the screening or diagnostic tools applied [10, 12]. Moreover, since ADHD has been recognized in adults, diagnostic tools for adult ADHD and its comorbid disorders have changed over time [13], and the interest in clinical diagnoses and optimal treatments in adults with ADHD has also increased [14]. These factors might have contributed to the divergent prevalence rate of ADHD and comorbid disorders in adults.

However, to the best of our knowledge, despite the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders documented in previous studies in the adult ADHD subjects [10, 11, 15, 16] and their importance in the clinical field, no systematic literature review has specifically compared the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders between adults with and without ADHD. Considering the high prevalence of adult ADHD and its impact on quality of life, a perspective on frequent comorbid psychiatric disorders would be helpful for individuals with ADHD and clinicians. Thus, the aim of our study was to ascertain the difference in the prevalence rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders between adults with and without ADHD including both clinical and general populations.

Methods

Study search and data sources

The methodology of the present review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [17]. Following PRISMA guideline, we conducted research based on PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome). The target population was adults with diagnosed ADHD. We compared the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders between ADHD and non-ADHD patients. We searched electronic libraries of PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycNET, and Google Scholar for publications regarding the epidemiology and prevalence rate of comorbidities of adult ADHD published from 1 January 1990 to 1 August 2022. The initial search was conducted by two authors (WSC, YSW) using the following terms: Prevalence AND (ADHD OR ADD OR Attention Deficit) AND Adult AND (comorbidity OR comorbid) in titles or abstracts. Each database was updated as appropriate when preparing this submission for publication. Full electronic search strategies are provided in the S1 Text.

Study selection

First, articles obtained from the initial search were de-duplicated by EndNote 20. Then, inclusion/exclusion screening was performed by lead authors (WSC, YSW) based on exclusion criteria of non-relevant articles (e.g., did not focus on adult patients or did not include psychiatric comorbidity data), non-English articles, full text not available, abstract-only papers, and articles that were not peer-reviewed. We included all types of research except a systematic review or meta-analysis defined by title and method. The initial inclusion/exclusion review was based on titles and abstracts; if the relevance of the article was unclear, a full-text review was performed to determine the eligibility of each study. After this initial process, the full texts of all included articles were retrieved to evaluate our detailed eligibility criteria. Articles were included in the study if they 1) used samples of adult populations aged 18 years or older, 2) defined clear ADHD and non-ADHD groups by clinically diagnoses or using any diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)) or tools for screening/diagnosing ADHD in adults (e.g., ASRS (Adult ADHD Self-report Scale)), 3) defined the prevalence rate of comorbid psychiatric disorders using any diagnostic tools for each psychiatric disorder (e.g. SCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV)), and 4) directly compared ADHD and non- ADHD groups using statistical analysis. Any discrepancy between the two lead authors during study selection was resolved through discussion, and other authors were consulted if necessary. The inclusion consistency between the two authors was 94.1% (32/34).

Data collection process

Microsoft Excel was used to develop a data extraction spreadsheet, and all included full-text articles were reviewed by both researchers (WSC, YSW), who also conducted the initial data search and study selection process. The extracted data were reviewed for consistency, and any queries that arose were resolved by discussion among the researchers. The lead author decided whether to include/exclude data by reviewing the specific articles.

Measurements

Because there are various methods for diagnosing ADHD and psychiatric disorders in adults, we extracted the following variables from the articles ultimately included: 1) data describing the study characteristics, such as year of publication, country, or study design; 2) data describing the target population, like sample size, age range or mean age/SD, or gender composition; 3) diagnostic tools for adult ADHD and comorbid psychiatric disorders, whether clinical diagnosis was performed, and the diagnostic criteria for ADHD/psychiatric comorbidity; 4) study results including the prevalence rate of ADHD in the target population, prevalence rate of each psychiatric comorbidity in each ADHD and non-ADHD group, and any statistically significant comparable variables including odd ratios(ORs) with 95% confidence intervals or chi-square (χ2) test variables.

Classification of studies

Based on several studies targeting nation-wide psychiatric comorbidities [18–20], assuming that the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders is higher in groups of psychiatric patients, we decided to divide the study populations into general population group studies and clinical group studies. A clinical group study was defined as one in which the study population included patients who had previously been clinically diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder or had visited/been admitted either voluntarily or involuntarily to a hospital for treatment. A general group study was defined as that in which the whole study population was not diagnosed with any psychiatric disorders before the start of each study.

In addition, considering the specificity that the prevalence of ADHD among incarcerated people was five to 10 times higher than that of the general population [21], and that the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among inmates was higher than that of the general population [22], we classified data of incarcerated patients separately from other population groups. The incarcerated group study was defined as a study that only included incarcerated participants.

Results

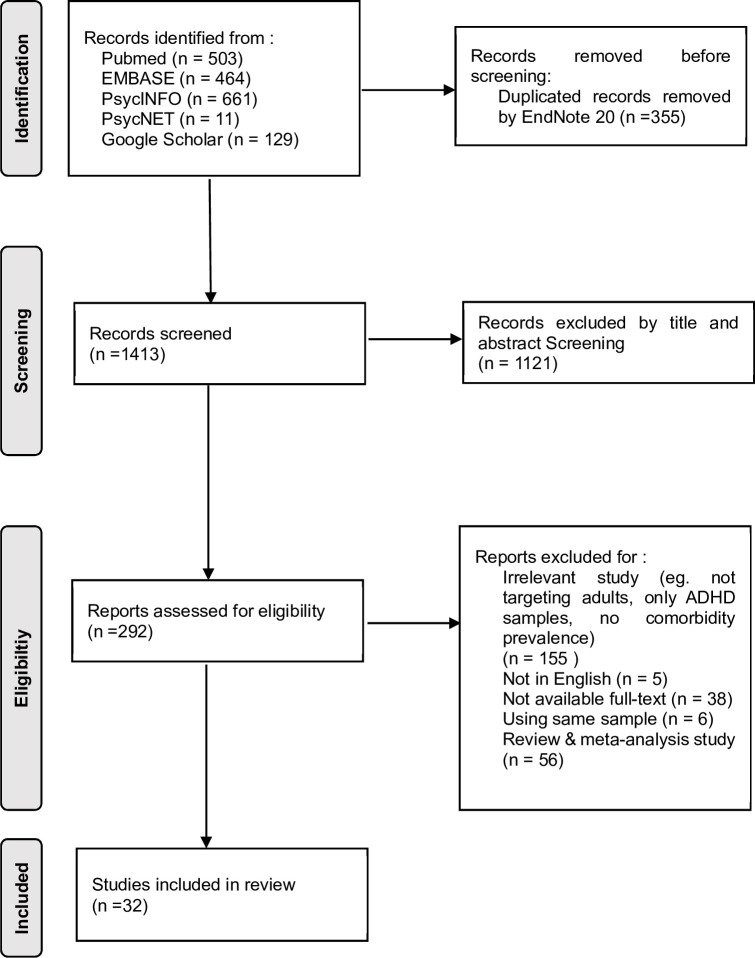

In total, 1768 articles were identified by the search method described above, and 335 duplicates were removed. After the duplicates were excluded, an additional 1121 articles were excluded by screening titles and abstracts. The remaining 292 articles were read in full and included in the analysis if they met the inclusion criteria of our study. Based on our study criteria, 260 articles were excluded for reasons noted in Fig 1. Thus, 32 studies comparing the prevalence rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders between ADHD and non-ADHD adult subjects were selected for systematic review.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Flow diagram of the manual screening process for eligible literature.

Of the 32 studies comparing the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorder between subjects with and without adult ADHD, according to our classification criteria, 11 studies involved general populations, 18 studies included psychiatric populations, and three studies focused on incarcerated populations. One of the three studies dealing with incarcerated populations involved only female inmates [23], and the other one study involved only male inmates [24].

Diagnostic tools of included studies

In this review, 12 diagnostic tools including clinical diagnostic criteria like DSM or ICD(International Classification of Disease), were used to evaluate adult ADHD. In addition, five diagnostic tools were mainly used for comorbid psychiatric disorders. The most used evaluation tool for adult ADHD was Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) [25, 26], which was used in 12 studies. Five studies used the ASRS alone to evaluate ADHD in adults, and the rest of the studies used more than one tool to evaluate ADHD. The next most frequently used evaluation tools were Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV(CAADID) [27] and the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) [28].

Prevalence of mood disorders

Nineteen studies provided data comparing the prevalence of mood disorders (including depressive disorders and bipolar disorders) between ADHD patients and non-ADHD individuals [6, 16, 29–45]. In the general populations, the prevalence of any depressive disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 1.2% [16] to 12.5% [35], compared to 8.6% [36] to 55% [6] in the ADHD group. In clinical populations, the prevalence of any depressive disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 5.8% [32] to 39.6% [34], compared to 15.4% [32] to 39.7% [44] in the ADHD group. In the general population, the prevalence of any bipolar disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 0.2% [35] to 3.6% [16] compared to 4.48% [42] to 35.3% [16] in the ADHD group. In clinical populations, the prevalence of any bipolar disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 2.0% [37] to 19.5% [40], compared to 7.4% [34] to 80.0.% [29] in the ADHD group. There were no differences reported in the prevalence of mood disorders between ADHD and non-ADHD groups in the incarcerated population studies. Detailed information from each study is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Studies comparing the prevalence of mood disorders between non-ADHD and ADHD subjects.

| Author | Year, | Country | N | % of male | Age | Assessment of ADHD | Assessment of comorbid psychiatric disorder | Design | Sample | Prev.of ADHD(%) (non-ADHD/ADHD) |

Findings comparing non-ADHD and ADHD and prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders | non-ADHD, n (%) vs ADHD, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General sample | ||||||||||||

| Solberg et al [43] | 2018 | Norway | 1,701,206 | 51.2% | 18≤ | ADHD medication at adult or ADHD diagnosis registered |

ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | General sample | 2.4% (40,103/1,661,103) | Bipolar Disorder | Women 13,183 (1.6%) vs 2,290 (12.9%) Men 9,009 (1.1%) vs 1,981 (8.9%) |

| Major depressive disorder | Women 61,880 (7.6%) vs 5,138 (28.8%) Men 33,733 (4.0%) vs 4,516 (20.3%) |

|||||||||||

| Chen et al [31] | 2018 | Norway | 5,551,807 | 50.81% | 18–64 | ICD-9: 314; ICD-10: F90 diagnosis | ICD | Cross-sectional study | General sample | 1.1% (61,129/5,490,678) | Depression | PR = 9.01 (8.92–9.10) |

| Bipolar Disorder | PR = 19.96 (19.48–20.43) | |||||||||||

| Hesson and Fowler [35] | 2018 | Canada | 16,957 | NA | 20–64 | Self-report of ADHD (diagnosed by a health professional) | WHO-CIDI modified for the needs of CCHS-MH |

Case-control study | General sample -national mental health survey |

2.9% (NA) | 12-month Major depressive disorder |

61 (12.5%) vs 113 (23.3%) χ2 = 59.94 |

| 12-month Bipolar disorder |

1 (0.2%) vs 20 (4.1%) χ2 = 17.73 | |||||||||||

| Yoshimasu et al [16] | 2016 | US | 5,718 | NA | Mean age ADHD 30.2 (SD 1.9) Non-ADHD controls 30.2 (SD 2.0) |

Childhood-identified ADHD with M.I.N.I (+) | M.I.N.I | Case-control study | General population–Birth cohort sample | NA, (68/335) | Hypomanic episode—current or past | 12 (3.6%) vs 24 (35.3%) OR adj 16.5 [7.2, 37.4] |

| Dysthymia | 4 (1.2%) vs 11 (16.2%) OR adj 19.0 [5.4, 66.1] | |||||||||||

| MDD | 9 (2.7%) vs 19 (27.9%) OR adj 15.2 [6.2, 37.4] | |||||||||||

| Park et al [39] | 2011 | South Korea | 6,081 | ADHD+ 59.4% ADHD- 50.5% |

18–59 | ASRS-S v 1.1 (+) | K-CIDI (Korean Ver. of CIDI) | Epidemiological study | General sample | 1.1% (69/6,012) | Any mood disorder | 6.0% vs 27.1% OR 6.44 [3.70–11.19] |

| Major depressive disorder | 5.5% vs 17.4% OR = 4.00[2.10–7.63] | |||||||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.2% vs 8.6% OR 29.94 [10.71–83.66] | |||||||||||

| Miller et al [38] | 2007 | US | 363 | 51.0% | 18–37 | K–SADS & structured interview | SCID–I, SCID-II | Case-control study | General sample - Recruited ADHD vs control group |

NA, (152/211) | Mood disorder | NA, χ2 = 23.70 |

| Sobanski et al [6] | 2007 | Germany | 140 | 54.3% | Mean age ADHD+ 36.8 (SD 9.0) ADHD- 39.8 (SD 10.0) |

WURS-K & BADDS | SCID-I | Case-control study | General sample -referred ADHD vs control group |

NA, (70/70) | Affective disorders total | 18 (25.7%) vs 44 (60.7%) χ2 = 18.462 |

| Major depressive episodes | 17 (24.3%) vs 40 (55%) χ2 = 15.010 | |||||||||||

| Kessler et al [36] | 2006 | US | 3,199 | NA | 18–44 | DIS-IV for childhood pathology & ACDS v 1.2 (ADHD-RS) | CIDI | Epidemiological study | General sample–national survey | 2.6% (NA) | Major depressive disorder | 7.8%vs 8.6% 4.2 OR 2.7[1.5–4.9] |

| Dysthymia | 1.9% vs 12.8% OR 7.5 [3.8–15] | |||||||||||

| Bipolar | 3.1% vs 19.4% OR 7.5 [4.6–12.0] | |||||||||||

| Any mood disorder | 11.1% vs 38.3% OR 5.0 [3.0–8.2] | |||||||||||

| Secnik et al [42] | 2005 | US | 4,504 | 64.3% | 18≤ | ICD-9 | ICD-9 | Case-control study | General sample–HPM database | (2,252/2,252) | Bipolar disorder | 0.58% vs 4.48% |

| Depression | 2.93% vs 17.10% | |||||||||||

| Clinical sample | ||||||||||||

| Woon and Zakaria [45] | 2019 | Malaysia | 120 | 94.2% | 18–65 | CAADID | M.I.N.I | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample | 15.8% (101/19) | Manic/hypomanic episode, lifetime | 8 (7.9%) vs 8 (42.1%) |

| Roncero et al [41] | 2019 | Spain | 726 | 72.5% | 18≤ | ASRS (14≤) | DSM-IV-TR | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–treatment seeking AUD patients | 21.1% (573/153) | Mood disorder | 24.5% vs 49% χ2 = 32.87, OR 2.95 [2.2, 4.3] |

| Leung and Chan [37] | 2017 | Hong Kong | 254 | 28.7% | 18–64 | ASRS-v1.1 Symptom Checklist≥17 & SDS ≥5 (Screening) + DIVA 2.0 (Diagnosis) | DSM-5 | Cross-sectional cohort study | Psychiatric sample–clinical outpatients | 19.3% (49/205) | Bipolar disorder | 2.0% vs 15.0% OR = 8.87 (1.83–42.9) (ADHD-combined type vs Non-ADHD) |

| Gorlin et al [34] | 2016 | US | 1,134 | 42% | Mean age 39.7 (SD 14.4) | DSM-IV based semi-structured clinical interview | SCID | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample—clinical outpatients | 18.0% (204/903) | Major depressive disorder | 39.6% vs 29.4% OR = 0. 69 (0.49–0.96) |

| Bipolar disorder | 3.4% vs 7.4% OR = 2.14 (1.09–4.02) | |||||||||||

| Fatséas et al [33] | 2016 | France | 217 | 66.4% | 18–65 | CAADID | DSM-IV for SUD SCIDII for BPD M.I.N.I. for others |

Cross-sectional cohort study | Psychiatric sample–addiction clinical outpatients | 23.0% (50/167) | Current mood disorders | 36.8% vs 54.0% 0.030 |

| van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen et al [44] | 2014 | Australia, Belgium, France, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, US (IASP study) (37) | 1,205 | ADHD– 73.1%ADHD + 75.6% | 18–65 | CAADID | MINI Plus SCID-II |

Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample—treatment-seeking SUD patients | 13.9% (168/1,037) | Current Depression—alcohol | 15.3% vs 39.7% OR 4.1 [2.1–7.8] |

| Current (hypo)mania | 4.1% vs 14.9% OR 4.3 [2.1–8.7] | |||||||||||

| Duran et al [32] | 2014 | Turkey | 246 | NA | 18–60 | WURS score >36 & Turgay’s Adult ADD/ADHD Evaluation Scale |

SCID-I-CV, SCID-II | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample—clinical outpatients | 15.9% (39/207) | Dysthymic Disorder | 12 (5.8%) vs 6 (15.4%) χ2 = 25.81 |

| Perugi et al [40] | 2013 | Italy | 96 | 59.4% | 18–65 | ASRS v 1.1 (+), & prior age 7 with ADHD sx | DSM-IV | Cross-sectional observation study | Psychiatric sample—Bipolar I, II disorder diagnosed | 19.8% (19/77) | BD I mixed state | 14 (18.2%) vs 10 (52.6%) χ2 = 9.6 |

| BD I mania | 13 (16.9%) vs 0 (0%) χ2 = 3.7 |

|||||||||||

| BD I remission | 15 (19.5%) vs 0 (0%) χ2 = 0.1 |

|||||||||||

| Ceraudo et al [29] | 2012 | Italy | 119 | 68.1% | Mean age ADHD+ 35.10 (SD 7.66) ADHD- 34.74 (SD 8.46) |

ASRS-S v 1.1 (+) | DCTC (Diagnostic, Clinical and Therapeutic Checklist) | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample – SUD outpatients |

18.35% (20/89) | Bipolar Disorder | 38 (43.2%) vs 16 (80.0%) χ2 = 8.84 |

| Mixed/Manic | 15 (16.9%) vs 8 (40.0%) χ2 = 3.29 | |||||||||||

| Olsson et al [30] | 2022 | Sweden | 804 | 67.3% | 18≤ | ICD-10 or prescription of ADHD medication | ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–psychiatric emergency patient with NSSI | 11.6% (711/93) | Depression | 218 (31%) vs 12 (13%), χ2 = 12.7 |

OR: Odd Ratio, PR: Prevalence Ratio, NA: Not available (not identified in article)

SUD: Substance Use Disorder, AUD: Alcohol use disorder, BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder BD I: Bipolar I disorder, WHO-CIDI: World Health Organization version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CCHS-MH: Community Health Survey–Mental Health, M.I.N.I: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, ASRS-S: Adult Self-Report Scale-Screener, ASRS: Adult Self-Report Scale, CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview, K-SADS: Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, SCID-I: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, SCID-I-CV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version, SCID-II: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders, WURS: Wender Utah Rating Scale, WURS-k: German short form of the Wender Utah rating scale, BADDS: Brown attention deficit disorder scale, DIS-IV: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, ACDS: Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale, ASHD-RS: ADHD Rating Scale, CAADID: Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV, ISAP: International ADHD in Substance use disorder Prevalence, NSSI: Nonsuicidal self-injury

Prevalence of anxiety and related disorders

Sixteen studies provided data comparing the prevalence of anxiety disorders including obsessive-compulsive disorder, somatoform disorders and trauma/stress-related disorders between ADHD patients and non-ADHD individuals [12, 16, 31, 34–36, 38, 39, 41–43, 45–49]. In general population, the prevalence of any anxiety disorders in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 0.5% [39] to 9.5% [36] compared to 4.3% [39] to 47.1% [36] in ADHD group. In clinical populations, the prevalence of any anxiety disorders in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 5.4% [46] to 40% [49] compared to 3.9% [34] to 84% [49] in the ADHD group. Only one study of incarcerated populations showed a difference in the prevalence of social phobia between non-ADHD and ADHD individuals [47]. Detailed information from each study is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Studies comparing the prevalence of anxiety and related disorder between non-ADHD and ADHD subjects.

| Author | Year | Country | N | % of male | Age | Assessment of ADHD | Assessment of comorbid psychiatric disorder | Design | Sample | Prev. of ADHD(%) (non-ADHD/ADHD) | Findings comparing non-ADHD and ADHD and prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders | non-ADHD, n (%) vs ADHD, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General sample | ||||||||||||

| Solberg et al [43] | 2018 | Norway | 1,701,206 | 51.2% | 18≤ | ADHD medication at adult or ADHD diagnosis registered |

ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | General sample | 2.4% (40,103/1,661,103) | Anxiety Disorders | Women 54,479 (6.7%) vs 4,676 (26.3%) Men 28,364 (3.3%) vs 4,054 (18.2%) |

| Chen et al [31] | 2018 | Norway | 5,551,807 | 50.81% | 18–64 | ICD-9: 314; ICD-10: F90 diagnosis | ICD | cross-sectional study | General sample | 1.1% (61,129/5,490,678) | Anxiety | PR = 9.12 (9.04–9.21) |

| Hesson and Fowler [35] | 2018 | Canada | 16,957 | NA | 20–64 | Self-report of ADHD (diagnosed by a health professional) | WHO-CIDI modified for the needs of CCHS-MH | Case-control study | General sample -national mental health survey |

2.9% (NA) | Generalized anxiety disorder | 15 (3.1%) vs 73 (15.1%) χ2 = 42.30 |

| Yoshimasu et al [16] | 2016 | US | 5,718 | NA | Mean age ADHD 30.2 (SD 1.9) Non-ADHD controls 30.2 (SD 2.0) |

Childhood-identified ADHD with M.I.N.I (+) | M.I.N.I. | Case-control study | General population– Birth cohort sample |

NA, (68/335) | PTSD | 3 (0.9%) vs 6 (8.8%) OR adj. 10.0 [2.9, 35.0] |

| Social phobia-current | 4 (1.2%) vs 10 (14.7%) OR adj 12.8 [4.2, 39.4] | |||||||||||

| OCD | 8 (2.4%) vs 14 (20.6%) OR adj 8.0 [3.3, 19.2] |

|||||||||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 30 (9.0%) vs 22 (32.4%) OR adj 4.7 [2.4, 9.0] | |||||||||||

| Panic disorder–lifetime | 17 (5.1) vs 9 (13.2) OR adj 2.6 [1.1, 6.2] | |||||||||||

| Park et al [39] | 2011 | South Korea | 6,081 | ADHD+ 59.4% ADHD- 50.5% |

18–59 | ASRS-S v 1.1 (+) | K-CIDI (Korean Ver. of CIDI) | Epidemiological study | General sample | 1.1% (69/6,012) | Any anxiety disorder | 6.3% vs 25.7% OR 5.46 [3.11–9.57] |

| OCD | 0.6% vs 4.3% OR 8.26 [2.51–27.26] |

|||||||||||

| PTSD | 1.2% vs 7.2% OR 8.13[3.26–20.32] |

|||||||||||

| Social phobia | 0.5% vs 11.4% OR 7.57 [1.92–29.83] |

|||||||||||

| Specific phobia | 3.9% vs 11.4% OR 3.31 [1.52–7.18] |

|||||||||||

| Somatoform disorder | 1.1% vs 4.3% OR 4.30 [1.22–15.12] |

|||||||||||

| Miller et al [38] | 2007 | US | 363 | 51.0% | 18–37 | K–SADS & structured interview | SCID–I, SCID-II | Case-control study | General sample- Recruited ADHD vs control group |

NA, (152/211) | Anxiety disorder | χ2 = 8.81 |

| Kessler et al [36] | 2006 | US | 3,199 | NA | 18–44 | DIS-IV for childhood pathology & ACDS v 1.2 (ADHD-RS) | CIDI | Epidemiologic study | General sample–national survey | 2.6% (NA) | GAD | 2.6% vs 8.0% OR 3.2 [1.5–6.9] |

| PTSD | 3.3% vs 11.9% OR 3.9 [2.1–7.3] |

|||||||||||

| Panic disorder | 3.1% vs 8.9% OR 3.0 [1.6–75.9] | |||||||||||

| Agoraphobia | 0.7% vs 4.0% OR 5.5 [1.6–18.5] | |||||||||||

| Specific phobia | 9.5% vs 22.7% OR 2.8 [1.7–4.6] | |||||||||||

| Social Phobia | 7.8% vs 29.3% OR 4.9 [3.1–7.6] | |||||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 19.5% vs 47.1% OR 3.7 [2.4–5.5] | |||||||||||

| Secnik et al [42] | 2005 | US | 4,504 | 64.3% | 18≤ | ICD-9 | ICD-9 | Case-control study | General sample–HPM database | NA (2,252/2,252) | Anxiety disorder | 3.46% vs 13.77% |

| Clinical sample | ||||||||||||

| El Ayoubi et al [49] | 2020 | France | 551 | 83.8% | 18≤ | Both ASRS-S v1.1(+) and WURS (26≤) | PCL-5 for PTSD | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric inpatients with AUD | 19.8% (442/109) | PTSD | 179 (40%) vs 91 (84%) χ2 = 64.7 |

| Woon and Zakaria [45] | 2019 | Malaysia | 120 | 94.2% | 18–65 | CAADID | M.I.N.I | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample -Forensic ward inpatient | 15.8% (101/19) | Generalized anxiety disorder | 20 (19.8%) vs 9 (47.4%) |

| Roncero et al [41] | 2019 | Spain | 726 | 72.5% | 18≤ | ASRS (14≤) | DSM-IV-TR | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric patients–treatment seeking AUD patients | 21.1% (573/153) | Anxiety disorder | 10.5% vs 25.8% χ2 = 23.5 OR 2.95 [1.88, 4.64] |

| Reyes et al [48] | 2019 | US | 472 | 64.6% | 18–80 | PRISM | PRISM | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–inpatient & outpatient with DSM-IV-TR AUD diagnosis | 6.36% (30/442) | Anxiety disorders, current | 95 (21.5%) vs 14 (46.7%) |

| Gorlin et al [34] | 2016 | US | 1,134 | 42% | Mean age 39.7 (SD 14.4) | DSM-IV based semi-structured clinical interview | SCID | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample-clinical outpatient | 18.0% (204/903) | Social phobia | 28.7% vs 38.2% OR = 1.46 (1.05–2.01) |

| Any adjustment disorder | 9.4% vs 3.9% OR = 0.41 (0.18–0.82) |

|||||||||||

| Retz et al [12] | 2016 | Germany | 163 | 86.5% | Mean age 40.2 (SD 9.4) | DSM-5 & WURS-k ≥ 30 | ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–GD dx according to ICD-10 | 25.2% (41-current ADHD/122) | Stress and adjustment disorders | 14 (8.6%) vs 7 (17.1%) χ2 = 5.70 |

| Karaahmet et al [46] | 2013 | Turkey | 90 | 53.3% | 18≤ | Turgay’s Adult ADD/ADHD Evaluation Inventory & WURS |

SCID-I | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample- Bipolar disorder diagnosed | 23.3% (21/69) | OCD | 6 (10.7%) vs 4 (19.0%) |

| Panic disorder | 3 (5.4%) vs 5 (23.8%) | |||||||||||

| Incarcerated sample | ||||||||||||

| Moore et al [47] | 2016 | Australia | 88 | 76% | 18–72 | ASRS-S (+) & M.I.N.I plus (+) | M.I.N.I plus, PDQ-4, SCID-II | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample | 17.0% (15/73) | Social phobia | 15.1% vs 46.7% OR = 4.39 [1.10, 17.56] |

OR: Odd Ratio, NA: Not available (not identified in article)

PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder, OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder, AUD: Alcohol used disorder, GD: Gambling disorder WHO-CIDI: World Health Organization version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CCHS-MH: Community Health Survey–Mental Health, M.I.N.I: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, ASRS-S: Adult Self-Report Scale-Screener, ASRS: Adult Self-Report Scale, CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview, K-SADS: Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, SCID-I: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, SCID-II: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders, WURS: Wender Utah Rating Scale, WURS-k: German short form of the Wender Utah rating scale, PRISM: Psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorders, PDQ-4: Personality disorder diagnostic questionnaire for the DSM-IV

Prevalence of substance use disorders and gambling disorder

Twenty-two studies provided data comparing the prevalence of substance use disorders (including addiction to alcohol, opioids, stimulants, cannabis, anxiolytics, and nicotine) and gambling disorders between ADHD and non-ADHD individuals [6, 12, 16, 23, 24, 31–33, 35–42, 45, 47, 48, 50–52]. In general populations, the prevalence of any substance use disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 0% [6] to 16.6% [39] compared to 2.3% [35] to 41.2% [16] in the ADHD group. In clinical populations, the prevalence of any substance use disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated to be 2.0% [45] to 72.2% [41] compared to 10.0% [48] to 82.9% [41] in the ADHD group. Two studies compared the prevalence of gambling disorder between ADHD and non-ADHD patients, and there was one study for each general/psychiatric population group, showing a statistically significant difference in prevalence [37, 39]. Two studies of incarcerated populations showed differences in the prevalence of benzodiazepine use disorder [47] and drug dependence [23]. Detailed information from each study is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Studies comparing the prevalence of substance use disorder and gambling disorder between non-ADHD and ADHD subjects.

| Author, | Year | Country | N | % of male | Age | Assessment of ADHD | Assessment of comorbid psychiatric disorder | Design | Sample | Prev.of ADHD(%) (non-ADHD/ADHD) | Findings comparing non-ADHD and ADHD and prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders | non-ADHD, n (%) vs ADHD, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General sample | ||||||||||||

| Cipollone et al [51] | 2020 | US | 18,913 | 88.3% | Mean age 28.72 in non-ADHD, 28.56 in ADHD |

ASRS-S (+) | CIDI & CIDI-SAM | Cross -sectional study (All army study) | General sample–Military sample | 6.6% (17,674/1,239) | Previous 30-days SUD diagnosis | 714 (4.04%) vs 211 (17.03%) χ2 = 515.36 |

| Lifetime SUD diagnosis | 2,639 (14.93%) vs 503 (40.60%) χ2 = 780.16 | |||||||||||

| Alcohol use (type 2—Five or more drinks per day- heavy drinking) | 2,064 (12.04%) vs 305 (25.10%) χ2 = 172.07 | |||||||||||

| Capusan et al [50] | 2019 | Sweden | 18,167 | 40.08% | 20–45 | DSM-IV criteria | SCID-I | Population-based epidemiological study | General population- Swedish Twin Registry | 8.8% (1,598/16,569) | Alcohol abuse | OR = 1.88 [1.44, 2.46] |

| Alcohol dependence | OR = 3.58 [2.86, 4.49] | |||||||||||

| Stimulants | OR = 2.45 [1.79, 3.35] | |||||||||||

| Opiates | OR = 1.97 [1.65, 2.36] | |||||||||||

| Cannabis Illicit drug use |

OR = 2.19 [1.80, 2.68] OR = 2.27 [1.86, 2.76] |

|||||||||||

| Poly-substance use | OR = 2.54[2.00, 3.23] | |||||||||||

| Poly-substance use including alcohol | OR = 2.78 [2.21, 3.50] | |||||||||||

| Chen et al [31] | 2018 | Norway | 5,551,807 | 50.81% | 18–64 | ICD-9: 314; ICD-10: F90 diagnosis | ICD | cross-sectional study | General sample | 1.1% (61,129/5,490,678) | SUD | PR = 9.74 (9.62–9.86) |

| Hesson and Fowler [35] | 2018 | Canada | 16,957 | NA | 20–64 | Self-report of ADHD (diagnosed by a health professional) | WHO-CIDI modified for the needs of CCHS-MH | Case-control study | General sample -national mental health survey | 2.9% (NA) | 12-month Alcohol dependence |

8 (1.7%) vs 27 (5.6%) χ2 = 10.83 .001 |

| Cannabis abuse | 3 (0.6%) vs 13 (2.7%) χ2 = 6.376 .012 | |||||||||||

| Cannabis dependence | 3 (0.6%) vs 11 (2.3%) χ2 = 4.605 .032 | |||||||||||

| Other drug dependence | 3 (0.6%) vs 17 (3.5%) χ2 = 10.01 .002 | |||||||||||

| Yoshimasu et al [16] | 2016 | US | 5,718 | NA | Mean age ADHD 30.2 (SD 1.9) Non-ADHD controls 30.2 (SD 2.0) |

Childhood-identified ADHD with M.I.N.I (+) | M.I.N.I. | Case-control study | General population– Birth cohort sample |

NA, (68/335) | Alcohol dependence/abuse | 51 (15.2%) vs 28 (41.2%) OR adj 3.6 [2.0, 6.7] |

| Substance dependence/abuse | 22 (6.6%) vs 18 (26.5%) OR adj 4.4 [2.1, 9.1] | |||||||||||

| Park et al [39] | 2011 | South Korea | 6,081 | ADHD+ 59.4%ADHD- 50.5% |

18–59 | ASRS-S v 1.1 (+) | K-CIDI (Korean Ver. Of CIDI) | Epidemiological study | General sample | (69/6,012) | Alcohol abuse/dependence | 16.6% vs 30.4% OR 1.97 [1.14–3.38] |

| Nicotine dependence | 7.7% vs 20.3% OR 2.81 [1.50–5.29] |

|||||||||||

| Pathological gambling | 0.7% vs 1.4% OR 8.43 [2.63–26.96] |

|||||||||||

| Miller et al [38] | 2007 | US | 363 | 51.0% | 18–37 | K–SADS & structured interview | SCID–I, SCID-II | Case-control study | General sample- Recruited ADHD vs control group |

NA, (152/211) | Any ADHD | SUD χ2 = 9.22 |

| Sobanski et al [6] | 2007 | Germany | 140 | 54.3% | Mean age ADHD+ 36.8 (SD 9.0) ADHD- 39.8 (SD 10.0) |

WURS-K & BADDS | SCID-I | Case-control study | General sample -referred ADHD vs control group |

NA, (70/70) | Substance related disorders total | 5 (7.1%) vs 21 (30.0%) χ2 = 12.397 |

| Substances total | 2 (2.9%) vs 20 (28.5%) χ2 = 17.806 | |||||||||||

| Substance abuse | 2 (2.9%) vs 12 (17.1%) χ2 = 8.104 | |||||||||||

| Substance dependence | 0 (0%) vs 8 (11.4%) χ2 = 8.612 | |||||||||||

| Kessler et al [36] | 2006 | US | 3,199 | NA | 18–44 | DIS-IV for childhood pathology & ACDS v 1.2 (ADHD-RS) | CIDI | Epidemiologic study | General sample–national survey | 2.6% (NA) | Drug dependence | 0.1% vs 4.4% OR 7.9 [2.3–27.3] |

| Any substance disorder | 5.6% vs 15.2% OR 3.0 [1.4–6.5] | |||||||||||

| Secnik et al [42] | 2005 | US | 4,504 | 64.3% | 18≤ | ICD-9 | ICD-9 | Case-control study | General sample–HPM database | NA, (2,252/2,252) | Drug or alcohol abuse | 1.87% vs 5.11% |

| Clinical sample | ||||||||||||

| Valsecchi et al [52] | 2021 | Italy | 590 | 47.2% | 18–70 | ASRS-S v1.1 (+) and DIVA 2.0 both(+) | M.I.N.I Plus | cross-sectional observational study | Psychiatric outpatients | 5.12% (590/44) | Substance abuse, lifetime | 15.1% vs 29.6% χ2 = 6.34 |

| Substance abuse, actual | 6.6% vs 25.0% χ2 = 19.06 | |||||||||||

| Substance use, lifetime | 30.5% vs 54.6% χ2 = 10.84 .001 | |||||||||||

| Substance use, actual | 8.3% vs 29.6% χ2 = 20.93 .000 | |||||||||||

| Woon and Zakaria [45] | 2019 | Malaysia | 120 | 94.2% | 18–65 | CAADID | M.I.N.I | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample -Forensic ward inpatient | 15.8% (101/19) | Alcohol abuse | 2 (2.0%) vs 3 (15.8%) 0.028 |

| Roncero et al [41] | 2019 | Spain | 726 | 72.5% | 18≤ | ASRS (14≤) | DSM-IV-TR | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric patients–treatment seeking AUD patients | 21.1% (573/153) | Cannabis dependence | 18% vs 30.9% χ2 = 12.3 OR 2.04 [1.36, 3.06] |

| Cocaine dependence | 24.6% vs 53.3% χ2 = 46.5 OR 3.5 [2.41, 5.07] | |||||||||||

| Smoking dependence | 72.2% vs 82.9% χ2 = 6.9 OR 1.86 [1.16, 2.98] | |||||||||||

| Reyes et al [48] | 2019 | US | 472 | 64.6% | 18–80 | PRISM | PRISM | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–inpatient & outpatient with DSM-IV-TR AUD diagnosis | 6.36% (30/442) | Cannabis abuse, Current | 41 (9.3%) vs 8 (26.7%) |

| Amphetamine abuse, current | 17 (3.9%) vs 4 (13.3%) | |||||||||||

| Opioid abuse, current | 9 (2.0%) vs 3 (10.0%) | |||||||||||

| Leung and Chan [37] | 2017 | Hong Kong | 254 | 28.7% | 18–64 | ASRS-v1.1 ≥17 & SDS ≥5(Screening) + DIVA 2.0 (Diagnosis) | DSM-5 | cross-sectional cohort study | Psychiatric sample–clinical outpatients | 19.3% (49/205) | Chronic alcohol use | (2.4% vs 8.2%) |

| Problematic gambling | (1% vs 2%) | |||||||||||

| Active substance use | (3.9% vs. 8.2%) | |||||||||||

| Retz et al [12] | 2016 | Germany | 163 | 86.5% | Mean age 40.2 (SD 9.4) | DSM-5 & WURS-k ≥ 30 | ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–GD dx according to ICD-10 | 25.2% (41-current ADHD/122) | Substance use disorders | 4’50 (30.7%) vs 19 (46.3%) χ2 = 6.50 |

| Fatséas et al [33] | 2016 | France | 217 | 66.4% | 18–65 | CAADID | DSM-IV for SUD SCID-II for BPD M.I.N.I for others |

Cross-sectional cohort study | Psychiatric sample–addiction outpatient clinic | 23.0% (50/167) | Cannabis dependence | 25.9% vs 58.0% |

| Duran et al [32] | 2014 | Turkey | 246 | NA | 18–60 | WURS score >36 & Turgay’s Adult ADD/ADHD Evaluation Scale |

SCID-I-CV, SCID-II | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample - outpatient visit patient |

15.9% (39/207) | Other Substance Abuse | 12 (5.8%) vs 7 (18.0%) χ2 = 28.81 |

| Perugi et al [40] | 2013 | Italy | 96 | 59.4% | 18–65 | ASRS v 1.1 (+), & prior age 7 with ADHD sx | DSM-IV | Cross-sectional observation study | Psychiatric sample- Bipolar I, II disorder diagnosed | 19.8% (19/77) | Alcohol | 7 (9.1%) vs 5 (26.3%) χ2 = 4.1 |

| Substance use disorder | 14 (18.2%) vs 8 (42.1%) χ2 = 7.1 | |||||||||||

| Incarcerated sample | ||||||||||||

| Moore et al [47] | 2016 | Australia | 88 | 76% | 18–72 | ASRS-S (+) & M.I.N.I plus (+) | M.I.N.I plus, PDQ-4, SCID-II | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample | 17.0% (15/73) | Benzodiazepine dependence (lifetime) | 13.7% vs 53.3 OR = 5.30 ([1.30, 21.72]) |

| Konstenius et al [23] | 2015 | Sweden | 96 | 0% | Mean age 39.7 | ASRS-S(+) & CAADID | M.I.N.I | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample- only women | 29% (16/40) | Drug dependence | 58% vs 100% |

| Capuzzi et al [24] | 2022 | Italy | 108 | 100% | 18–65 | WURS-25 & ASRS V1.1 | DSM-5 | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample- only men | 32.4% (35/73) | Cannabis use disorder | 40 (54.8%) vs 25 (71.4%) |

| Cocaine use disorder | 47 (64.4%) vs 32 (91.4%) | |||||||||||

OR: Odd Ratio, PR: Prevalence Ratio, NA: Not available (not identified in article)

SUD: Substance Use Disorder, AUD: Alcohol use disorder, GD: Gambling disorder CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CIDI-SAM: CIDI-Substance Abuse Module, SCID-I: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, WHO-CIDI: World Health Organization version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, M.I.N.I: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, CAADID: Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV, ASRS-S: Adult Self-Report Scale-Screener, ASRS: Adult Self-Report Scale, BADDS: Brown attention deficit disorder scale, PRISM: Psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorders SDS: Sheehan Disability Scale, DIVA: Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults, WURS: Wender Utah Rating Scale, WURS-k: German short form of the Wender Utah rating scale, PDQ-4: Personality disorder diagnostic questionnaire for the DSM-IV, SCID-I-CV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version

Prevalence of personality disorders

Fourteen studies provided data comparing the prevalence of personality disorders (including borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder) between ADHD and non-ADHD individuals [12, 16, 23, 24, 30, 33, 34, 38, 41–44, 47, 53]. In general populations, the prevalence of any personality disorders in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 0% [42] to 3.9% [16] compared to 0.31% [42] to 33.8% [16] in the ADHD group. In clinical populations, the prevalence of any personality disorder in the non-ADHD group was estimated at 6.6% [33] to 34.4% [12] compared to 21.9% [34] to 65.95% [12] in the ADHD group. Two studies of incarcerated populations showed differences in the prevalence of borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. The prevalence of antisocial personality disorder was higher in the ADHD group in both studies [23, 47], and the prevalence of borderline personality disorder was higher in one study [47]. Detailed information from each study is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Studies comparing the prevalence of personality disorder between non-ADHD and ADHD subjects.

| Author | Year | Country | N | Male; % | Age | Assessment of ADHD | Assessment of comorbid psychiatric disorder | Design | Sample | Prev.of ADHD(%) (non-ADHD/ADHD) | Findings comparing non-ADHD and ADHD and prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders | non-ADHD, n (%) vs ADHD, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General sample | ||||||||||||

| Solberg et al [43] | 2018 | Norway | 1,701,206 | 51.2% | 18≤ | ADHD medication at adult or ADHD diagnosis registered | ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | General sample | 2.4% (40,103/1,661,103) | Personality disorder | Women 14,079 (1.7%) vs 2,428 (13.6%) Men 8909 (1.1%) vs 2030 (9.1%) |

| Yoshimasu et al [16] | 2016 | US | 5,718 | NA | Mean age ADHD 30.2 (SD 1.9) Non-ADHD controls 30.2 (SD 2.0) |

Childhood-identified ADHD with M.I.N.I (+) | M.I.N.I. | Case-control study | General population– Birth cohort sample |

NA, (68/335) | Antisocial personality disorder | 13 (3.9%) vs 23 (33.8%) OR adj 12.2 [5.3, 27.9] |

| Miller et al [38] | 2007 | US | 363 | 51.0% | 18–37 | K–SADS & structured interview | SCID–I, SCID-II | Case-control study | General sample- Recruited ADHD vs control group |

NA, (152/211) | ASPD (Any ADHD) | χ2 = 7.32 |

| Secnik et al [42] | 2005 | US | 4504 | 64.3% | 18≤ | ICD-9 | ICD-9 | Case-control study | General sample–HPM database | NA, (2,252/2,252) | Antisocial disorder Oppositional disorder |

0% vs 0.31% 0.04% vs 0.53% |

| Clinical sample | ||||||||||||

| Sánchez-García et al [53] | 2021, | Puerto-rico, Hungary, Australia | 402 | 79.6% | 18–65 | CAADID | M.I.N.I Plus | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric inpatients & outpatients with SUD | 35.75% (257/143) | ASPD BPD |

25.41% vs 53.90% OR 3.26 [2.09, 5.08] 20.82% vs 57.45% OR 5.48 [3.40, 8.83] |

| Roncero et al [41] | 2019 | Spain | 726 | 72.5% | 18≤ | ASRS (14≤) | DSM-IV-TR | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric patients–treatment seeking AUD patients | 21.1% (573/153) | Any personality disorder | 14.8% vs 37.4% χ2 = 38.17 .0001 OR 3.45 [2.29, 5.17] |

| Gorlin et al [34] | 2016, | US | 1,134 | 42% | Mean age 39.7 (SD 14.4) | DSM-IV based semi-structured clinical interview | SCID | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample-clinical outpatient | 18.0% (204/903) | Borderline personality disorder | 7.6% vs 21.9% OR = 3.11 (2.02–4.76) |

| Retz et al [12] | 2016 | Germany | 163 | 86.5% | Mean age 40.2 (SD 9.4) | DSM-5 & WURS-k ≥ 30 | ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–GD dx according to ICD-10 | 25.2% (41-current ADHD/122) | Personality disorders Cluster B |

56 (34.4%) vs 27 (65.9%) χ2 = 26.84 11 (6.7%) vs 7 (17.1%) χ2 = 30.49 |

| Fatséas et al [33] | 2016 | France | 217 | 66.4% | 18–65 | CAADID | DSM-IV for SUD SCID-II for BPD M.I.N.I for others |

Cross-sectional cohort study | Psychiatric sample–addiction outpatient clinic | 23.0% (50/167) | Antisocial personality disorder Borderline personality disorder |

6.6% vs 26.0% 13.0% vs 34.7% |

| van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen et al [44] | 2014 | Australia, Belgium, France, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, US (IASP study) (37) | 18–65 | CAADID | M.I.N.I Plus SCID-II |

Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample- treatment-seeking SUD patients | 13.9% (168/1,037) | ASPD BPD |

17.0% vs 51.8% OR 2.8 [1.8–4.2] -alcohol 8.2% vs 34.5% OR 7.0 [3.1–15.6] -drugs 16.7% vs 29.0% OR 3.4 [1.8–6.4] |

||

| Olsson et al [30] | 2022 | Sweden | 804 | 67.3% | 18≤ | ICD-10 or prescription of ADHD medication | ICD-10 | Cross-sectional study | Psychiatric sample–psychiatric emergency patient with NSSI | 11.6% (711/93) | Personality disorder | 142 (20%) vs 28 (30), χ2 = 5.07 |

| Incarcerated sample | ||||||||||||

| Moore et al [47] | 2016 | Australia | 88 | 76% | 18–72 | ASRS-S (+) & MINI plus (+) | M.I.N.I plus, PDQ-4, SCID-II | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample | 17.0% (15/73) | BPD ASPD |

13.7% vs 60.0% OR = 7.34 ([1.72, 31.37]) 27.4% vs 93.3% OR = 26.00 ([2.58, 262.30]) |

| Konstenius et al [23] | 2015 | Sweden | 96 | 0% | Mean age 39.7 | ASRS-S (+) & CAADID | M.I.N.I | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample- only women | 29% (16/40) | ASPD | 30% vs 81% |

| Capuzzi et al [24] | 2022 | Italy | 108 | 100% | 18–65 | WURS-25 & ASRS V1.1 | DSM-5 | Cross-sectional study | Incarcerated sample- only men | 32.4% (35/73) | Personality disorders | 26 (35.6%) vs 21 (60.0%) |

OR: Odd Ratio, NA: Not available (not identified in article)

SUD: Substance Use Disorder, AUD: Alcohol use disorder, GD: Gambling disorder BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder, ASPD: Antisocial personality disorder

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, M.I.N.I: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, ASRS-S: Adult Self-Report Scale-Screener, ASRS: Adult Self-Report Scale, CAADID: Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV, WURS-k: German short form of the Wender Utah rating scale, K-SADS: Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, PDQ-4: Personality disorder diagnostic questionnaire for the DSM-IV

HPM: Health and Productivity Management

ISAP: International ADHD in Substance use disorder Prevalence

Discussion

In our systematic review, we included 32 studies conducted over 16 years dealing with the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities between adults with and without ADHD. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review comparing the prevalence of comprehensive comorbid psychiatric disorders between adults with and without ADHD and including both general and clinical populations. Articles published from 2006 to 2022 were included in this review. This might because the interest in adult ADHD had increased based on the results of longitudinal follow-up studies on children and adolescents with ADHD [54, 55].

The studies included in this review most commonly used ASRS as a diagnostic tool for adult ADHD (12 of 32), followed by CADDID and WURS. As a self-report scale, due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness, ASRS can be preferred by ADHD investigators. However, the variability in the evaluation tools for adult ADHD is thought to be due to the lack of established diagnostic criteria [56]. Many psychiatric disorders are diagnosed based on observation of an assessor and complaint of a patient. The lack of standardized diagnostic tools can lead to over-diagnosis or under-diagnosis of psychiatric disorders [57, 58] and can cause inconsistency in diagnosis, which complicates comparison studies [59, 60]. Heterogeneity of diagnostic tools observed in this study not only prevented meta-analysis, but also might affect the variability in the reported prevalence of adult ADHD.

In addition, the prevalence of ADHD in adults varied from 1.1% [39] to 8.8% [50] in general population samples and from 5.12% [52] to 35.75% [53] in psychiatric population samples. A previous systematic review of ADHD prevalence in and adult psychiatric population shows a similar range, from 6.9% to 38.75% [61]. In this previous study [61], the authors assumed that this variation might be due to the diversity of diagnostic methods and the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the studies. Similarly, in our study, the aforementioned variability of diagnostic methodologies for ADHD might have affected this various range of prevalence. In a general population, the estimated mean prevalence rate of ADHD in adults was 2.8% in a previous study [15]. Except in two studies included in our review, targeting special populations of army soldiers [51] and twins of Sweden [50], which had higher than estimated prevalence, the range of ADHD prevalence in the general population was 1.1% to 2.9% in our study, similar to that previously observed [11, 56].

The most frequent comorbid psychiatric disorder in the ADHD group was SUD, its prevalence ranging from 2.3% and 41.2% in the general population and between 10.0% and 82.9% in the clinical population; two of three studies showed significant prevalence difference between ADHD and non-ADHD subjects. This finding correlates with a previous meta-analysis that reported that almost one out of every four adolescent and adult patients with SUD presents with ADHD [62, 63], which supports SUD as one of the most frequent comorbid psychiatric conditions in adult ADHD. There are some theoretical opinions of shared key characteristics and pathophysiology between ADHD and SUD, like dopaminergic dysregulation of motivational and reward systems, or reduced frontal function including executive functions and response inhibition [64, 65]. In addition, considering that childhood ADHD is a prominent risk factor for substance misuse and development of SUD due to the most frequent comorbidities in childhood ADHD, like conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder [66], untreated and preserved ADHD in adults might have influenced the cross-sectional difference of prevalence rate between ADHD and non- ADHD patients.

Mood disorders, including depressive disorders and bipolar disorders, were also frequently observed comorbid psychiatric disorders in ADHD subjects compared to non-ADHD subjects. The estimated prevalence of depressive disorders in the ADHD group ranged from 8.6% to 55% in the general population and 15.4% to 39.7% in the clinical population. Also, the prevalence of bipolar disorder in the ADHD group was estimated at 4.45% to 35.3% in the general population and 7.4% to 80.8% in the clinical population. For depression, previous studies have also shown a higher prevalence of depressive disorders in young adults with ADHD compared to non-ADHD subjects as well as higher risk of suicidal behavior [67, 68]. This can be explained by a previous cross-sectional study showing the association between ADHD symptoms and depressive symptoms in young adults as identified by low hedonic responsivity [69]. In addition, according to biologic aspects of depression and ADHD, the two disorders might share similar pathophysiologic regions of the brain including decreased activity in the prefrontal [70, 71], amygdala, and hippocampus regions [72–74]. Furthermore, 10 studies showed a higher prevalence of bipolar disorder, including current hypomania diagnosed by SCID-II, in ADHD subjects than in non-ADHD subjects. Considering that the worldwide prevalence rate of bipolar disorder is estimated as 1–3% [75, 76], which was similar to that of the non-ADHD general population in our study, the prevalence of bipolar disorder in the ADHD group was greater than 3% in all 10 studies. This finding correlated with previous studies reporting reciprocal high comorbidity rates between ADHD and bipolar disorder, which suggests possible shared genetic effects or diagnostic overlap between the two disorders [77].

In anxiety disorder, almost two of three studies showed a higher prevalence in the ADHD group than the non-ADHD group. The prevalence rate in the ADHD group was estimated to range from 4.3% to 47.1% in the general population and from 3.9% to 84% in the clinical population. Only one study of a clinical population dealing with psychiatric outpatients in the US [34] showed a higher prevalence of adjustment disorder in the non-ADHD group. These findings correlate with previous studies that revealed a high prevalence of anxiety in the adult ADHD population [78, 79]. ADHD seems to show different characteristics from anxiety, namely fearlessness and impulsivity. Therefore, various theories have been suggested to explain this phenomenon using developmental or biologic aspects in children and adolescents [80]. Similarly, in adults, as far as we know, the two disorders have been related to several common neuroanatomical regions like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or the anterior cingulate cortex, which are critically involved with the executive function control network [10]. In addition, considering a previous study about increased risk of accidents in ADHD over the lifespan [81], traumatic events might have influenced the higher prevalence of anxiety disorders. From a developmental viewpoint, as in depressive disorders, this frequently higher prevalence of anxiety disorder might represent the social and relational difficulties induced by ADHD.

The estimated prevalence of personality disorders in the ADHD group was ranged from 0.31% to 33.8% in the general population and from 21.9% to 65.95% in the clinical population. Previous studies have reported that personality disorders, mostly cluster B or C personality disorders, are present in almost 50% of adults with ADHD [82]. The association between ADHD and personality disorders might be mediated by the symptomatic dimensions of ADHD such as emotional dysregulation and oppositional symptoms [83]. In our review, most studies showed a higher prevalence of cluster B personality disorders in ADHD than in non-ADHD groups. Specifically, in the clinical population, more than 20% of adult ADHD subjects were estimated to have comorbid cluster B personality disorder including borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. Additionally, most clinical population studies included patients diagnosed with substance use disorders, which correlates with previous observational studies of young male adults with ADHD that revealed associations of antisocial personality disorder with ADHD [84].

Limitations

There are several limiting factors in this review. As mentioned previously, there is significant heterogeneity across studies diagnosing both ADHD and comorbid psychiatric disorders. This prohibited meta-analysis. Furthermore, except for two international studies [44, 53], the included studies were conducted in high-income regions like Europe or North America. In a previous epidemiologic study investigating cross-national ADHD prevalence in adults [15], the prevalence differed by country income, with higher rates observed in higher-income countries. This difference in prevalence among countries affects the degree of interest in the disease, which might be why the included studies were mainly conducted in Europe and North America. In addition, we did not differentiate patients according to ADHD or comorbid psychiatric disorder treatment status, which might also have affected the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders. Of the included studies, most explored the prevalence cross-sectionally, so we could not infer a correlation or antecedent relationship between ADHD and comorbidities. Only limited estimates of the associations between ADHD and comorbidities can be provided by our review at the study level. Additionally, we did not assess the risk of bias in each study. To include as many studies as possible to reflect broad and various studies of different countries, populations, and comorbid psychiatric disorders, we omitted the risk of bias assessment. Also, there was no pre-registration for our systematic literature review. These points are limitations to this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings indicate a higher prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in ADHD subjects compared to non-ADHD subjects, whether they were previously diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders or not. Furthermore, our results suggest a complex association between the multiple comorbidities of ADHD. Given that ADHD is often unrecognized and under-diagnosed in adults, screening for ADHD might be beneficial for patients presenting multiple psychopathologies including substance abuse, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. In the future, research on standardization of ADHD diagnosis in adults and its comorbid psychopathologies will be required to distinguish adult ADHD from comorbid psychiatric disorders, and to enable comparison among study conditions. This standardization will aid in differential diagnosis and allow provision of earlier treatment in adult ADHD. In addition, research on the neurobiological and developmental bases of ADHD and its comorbid psychiatric disorders should continue to improve the understanding of the connectivity and associations between various comorbid psychiatric disorders and ADHD in adults.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Young S, Kahle J, Woods AG, et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med. 2012;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):159–65. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500471X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros Á, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobanski E, Brüggemann D, Alm B, Kern S, Deschner M, Schubert T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and functional impairment in a clinically referred sample of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(7):371–7. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0712-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faraone SV, Biederman J. Neurobiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(10):951–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00240-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo J-C, Jon D-I, Shim S-H, Sung H-M, Woo YS, Hong J, et al. Prevalence and Comorbidities of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Among Adults and Children/Adolescents in Korea. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2022;20(1):126–34. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2022.20.1.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens T, Norman D, Lapey KA, et al. Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1792–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, Fallu A, Klassen LJ. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1463-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fayyad J, de Graaf R, Kessler R, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Demyttenaere K, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:402–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retz W, Ringling J, Retz-Junginger P, Vogelgesang M, Rösler M. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with gambling disorder. J Neural Transm. 2016;123(8):1013–9. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1566-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kooij JJS, Bijlenga D, Salerno L, Jaeschke R, Bitter I, Balázs J, et al. Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56:14–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raman SR, Man KKC, Bahmanyar S, Berard A, Bilder S, Boukhris T, et al. Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: a retrospective observational study using population-based databases. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(10):824–35. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30293-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Adamowski T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9(1):47–65. doi: 10.1007/s12402-016-0208-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimasu K, Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Weaver AL, et al. Adults With Persistent ADHD: Gender and Psychiatric Comorbidities—A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. J Atten Disord. 2016;22(6):535–46. doi: 10.1177/1087054716676342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews G, Slade T, Issakidis C. Deconstructing current comorbidity: data from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:306–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.4.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(12):587–95. doi: 10.1007/s001270050098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Holtz Y, Benros ME, Dalsgaard S, de Jonge P, et al. Exploring Comorbidity Within Mental Disorders Among a Danish National Population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):259–70. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young S, Moss D, Sedgwick O, Fridman M, Hodgkins P. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in incarcerated populations. Psychol Med. 2015;45(2):247–58. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fazel S, Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(5):364–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konstenius M, Larsson H, Lundholm L, Philips B, van de Glind G, Jayaram-Lindström N, et al. An epidemiological study of ADHD, substance use, and comorbid problems in incarcerated women in Sweden. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(1):44–52. doi: 10.1177/1087054712451126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capuzzi E, Capellazzi M, Caldiroli A, Cova F, Auxilia AM, Rubelli P, et al. Screening for ADHD Symptoms among Criminal Offenders: Exploring the Association with Clinical Features. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(2). doi: 10.3390/healthcare10020180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler L, Kessler RC, Spencer T. Adult ADHD self-report scale-v1. 1 (ASRS-v1. 1) symptom checklist. New York, NY: World Health Organization. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–56. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein J, Johnson DE, Conners CK. Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV™. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):885–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceraudo G, Toni C, Vannucchi G, Rizzato S, Casalini F, Dell’Osso L, et al. Is substance use disorder with comorbid adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder a distinct clinical phenotype? Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 2012;14(3):71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsson P, Wiktorsson S, Strömsten LM, Salander Renberg E, Runeson B, Waern M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults who present with self-harm: a comparative 6-month follow-up study. BMC psychiatry. 2022;22(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, Hartman CA, Haavik J, Harro J, Klungsøyr K, Hegvik TA, et al. Common psychiatric and metabolic comorbidity of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duran S, Nurhan F, Ali K, Bilici M, ÇAliskan M. ADHD in Adult Psychiatric Outpatients: Prevalence and Comorbidity: Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2014;25(2):84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fatséas M, Hurmic H, Serre F, Debrabant R, Daulouède J-P, Denis C, et al. Addiction severity pattern associated with adult and childhood Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in patients with addictions. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246:656–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorlin EI, Dalrymple K, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Diagnostic profiles of adult psychiatric outpatients with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;70:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hesson J, Fowler K. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported ADD/ADHD in a large national sample of Canadian adults. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(2):191–200. doi: 10.1177/1087054715573992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung VMC, Chan LF. A cross-sectional cohort study of prevalence, co-morbidities, and correlates of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among adult patients admitted to the Li Ka Shing psychiatric outpatient clinic, Hong Kong. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2017;27(2):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller TW, Nigg JT, Faraone SV. Axis I and II comorbidity in adults with ADHD. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(3):519–28. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park S, Cho MJ, Chang SM, Jeon HJ, Cho S-J, Kim B-S, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidities of adult ADHD symptoms in Korea: Results of the Korean epidemiologic catchment area study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(2–3):378–83. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perugi G, Ceraudo G, Vannucchi G, Rizzato S, Toni C, Dell’Osso L. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms in Italian bipolar adult patients: A preliminary report. J Affect Disord. 2013;149(1–3):430–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roncero C, Ortega L, Pérez-Pazos J, Lligoña A, Abad AC, Gual A, et al. Psychiatric Comorbidity in Treatment-Seeking Alcohol Dependence Patients With and Without ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(12):1497–504. doi: 10.1177/1087054715598841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Secnik K, Swensen A, Lage MJ. Comorbidities and Costs of Adult Patients Diagnosed with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(1):93–102. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523010-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solberg BS, Halmøy A, Engeland A, Igland J, Haavik J, Klungsøyr K. Gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity: A population‐based study of 40 000 adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(3):176–86. doi: 10.1111/acps.12845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Emmerik‐van Oortmerssen K, van de Glind G, Koeter MWJ, Allsop S, Auriacombe M, Barta C, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in treatment‐seeking substance use disorder patients with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of the IASP study. Addiction. 2014;109(2):262–72. doi: 10.1111/add.12370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woon LSC, Zakaria H. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a Malaysian forensic mental hospital: A cross-sectional study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2019;29(4):118–23. doi: 10.12809/eaap1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karaahmet E, Konuk N, Dalkilic A, Saracli O, Atasoy N, Kurçer MA, et al. The comorbidity of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in bipolar disorder patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(5):549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore E, Sunjic S, Kaye S, Archer V, Indig D. Adult ADHD Among NSW Prisoners: Prevalence and Psychiatric Comorbidity. J Attent Disord. 2016;20(11):958–67. doi: 10.1177/1087054713506263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reyes MM, Schneekloth TD, Hitschfeld MJ, Karpyak VM. Impact of sex and ADHD status on psychiatric comorbidity in treatment-seeking alcoholics. J Attent Disord. 2019;23(12):1505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El Ayoubi H, Brunault P, Barrault S, Maugé D, Baudin G, Ballon N, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Is Highly Comorbid With Adult ADHD in Alcohol Use Disorder Inpatients. J Attent Disord. 2020:1087054720903363. doi: 10.1177/1087054720903363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capusan AJ, Bendtsen P, Marteinsdottir I, Larsson H. Comorbidity of Adult ADHD and Its Subtypes With Substance Use Disorder in a Large Population-Based Epidemiological Study. J Attent Disord. 2019;23(12):1416–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cipollone G, Gehrman P, Manni C, Pallucchini A, Maremmani AGI, Palagini L, et al. Exploring the role of caffeine use in adult-ADHD symptom severity of US army soldiers. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11):1–10. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valsecchi P, Nibbio G, Rosa J, Tamussi E, Turrina C, Sacchetti E, et al. Adult ADHD: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates in a Sample of Italian Psychiatric Outpatients. J Attent Disord. 2021;25(4):530–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sánchez-García NC, González RA, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Van Den Brink W, Luderer M, Blankers M, et al. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Increases Nicotine Addiction Severity in Adults Seeking Treatment for Substance Use Disorders: The Role of Personality Disorders. Eur Addict Res. 2020;26(4–5):191–200. doi: 10.1159/000508545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Taylor A, Sienna M, Williamson S, Fine C. Diagnostic continuity between child and adolescent ADHD: findings from a longitudinal clinical sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(3):305–13. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV. Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):816–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.04009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zimmerman M. A Review of 20 Years of Research on Overdiagnosis and Underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71–9. doi: 10.1177/0706743715625935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newson JJ, Hunter D, Thiagarajan TC. The heterogeneity of mental health assessment. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:76. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wisco BE, Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Kilpatrick D, Resnick HS, Badour CL, et al. The impact of proposed changes to ICD-11 on estimates of PTSD prevalence and comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linden M, Muschalla B. Standardized diagnostic interviews, criteria, and algorithms for mental disorders: garbage in, garbage out Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(6):535–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerhand S, Saville CW. ADHD prevalence in the psychiatric population. International Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2021.1914663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Burg D, Crunelle CL, Matthys F, van den Brink W. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with comorbid substance use disorder and adult attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder: a review of recent publications. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(4). doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen K, van de Glind G, van den Brink W, Smit F, Crunelle CL, Swets M, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in substance use disorder patients: A meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma A, Couture J. A Review of the Pathophysiology, Etiology, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Ann Pharmacother. 2013;48(2):209–25. doi: 10.1177/1060028013510699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. Imaging studies on the role of dopamine in cocaine reinforcement and addiction in humans. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(4):337–45. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J. Childhood Psychiatric Disorders as Risk Factor for Subsequent Substance Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):556–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fitzgerald C, Dalsgaard S, Nordentoft M, Erlangsen A. Suicidal behaviour among persons with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(4):615–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Babinski DE, Neely KA, Ba DM, Liu G. Depression and suicidal behavior in young adult men and women with ADHD: evidence from claims data. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):0–. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m13130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meinzer MC, Pettit JW, Leventhal AM, Hill RM. Explaining the Covariance Between Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Depressive Symptoms: The Role of Hedonic Responsivity. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(10):1111–21. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arnsten AFT. The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. J Pediatr. 2009;154(5):I–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Treadway MT, Waskom ML, Dillon DG, Holmes AJ, Park MTM, Chakravarty MM, et al. Illness progression, recent stress, and morphometry of hippocampal subfields and medial prefrontal cortex in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(3):285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perlov E, Philipsen A, Tebartz van Elst L, Ebert D, Henning J, Maier S, et al. Hippocampus and amygdala morphology in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33(6):509–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frodl T, Stauber J, Schaaff N, Koutsouleris N, Scheuerecker J, Ewers M, et al. Amygdala reduction in patients with ADHD compared with major depression and healthy volunteers. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(2):111–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Onnink AMH, Zwiers MP, Hoogman M, Mostert JC, Kan CC, Buitelaar J, et al. Brain alterations in adult ADHD: Effects of gender, treatment and comorbid depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(3):397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RMA, Petukhova M, et al. Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He J-P, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–51. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schiweck C, Arteaga-Henriquez G, Aichholzer M, Edwin Thanarajah S, Vargas-Cáceres S, Matura S, et al. Comorbidity of ADHD and adult bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;124:100–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Piñeiro-Dieguez B, Balanzá-Martínez V, García-García P, Soler-López B. Psychiatric Comorbidity at the Time of Diagnosis in Adults With ADHD: The CAT Study. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(12):1066–75. doi: 10.1177/1087054713518240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reimherr FW, Marchant BK, Strong RE, Hedges DW, Adler L, Spencer TJ, et al. Emotional Dysregulation in Adult ADHD and Response to Atomoxetine. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(2):125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schatz DB, Rostain AL. ADHD with comorbid anxiety: a review of the current literature. J Attent Disord. 2006;10(2):141–9. doi: 10.1177/1087054706286698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brunkhorst-Kanaan N, Libutzki B, Reif A, Larsson H, McNeill RV, Kittel-Schneider S. ADHD and accidents over the life span—A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;125:582–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]