Abstract

Fidaxomicin (Fdx) is widely used to treat Clostridioides difficile (Cdiff) infections (CDIs), but the molecular basis of its narrow-spectrum activity in the human gut microbiome remains enigmatic. CDIs are a leading cause of nosocomial deaths. Fdx, which inhibits RNA polymerase (RNAP), targets Cdiff with minimal effects on gut commensals, reducing CDI recurrence. Here, we present the cryo-electron microscopy structure of Cdiff RNAP in complex with Fdx, allowing us to identify a crucial Fdx-binding determinant of Cdiff RNAP that is absent in most gut microbiota like Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes. By combining structural, biochemical, genetic, and bioinformatic analyses, we establish that a single RNAP residue is a sensitizing element for Fdx narrow-spectrum activity. Our results provide a blueprint for targeted drug design against an important human pathogen.

Clostridioides difficile (Cdiff) is a gram-positive, spore-forming, and toxin-producing intestinal bacterium that infects the human gut and causes lethal diarrhea (Cdiff infections or CDIs). With the alarming increase in infections caused by highly pathogenic variants, Cdiff has been designated an “urgent threat” by CDC1. Broad-spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin and metronidazole are used to treat CDIs, but these antibiotics decimate the normal gut microbiome, paradoxically priming the gastrointestinal tract to become more prone to CDI recurrences2,3 (Fig.1a). In 2011, the macrocyclic antibiotic fidaxomicin (Fdx; Fig. 1b) became available to treat CDI. Fdx selectively targets Cdiff but does not effectively kill crucial gut commensals such as Bacteroidetes4, abundant microbes in the human gut microbiome that protects against Cdiff colonization5,6. Fdx targets the multisubunit bacterial RNA polymerase (RNAP, subunit composition α2ββ′ω), which transcribes DNA to RNA in a complex and highly regulated process. However, no structure is available for Clostridial RNAP. Studies using Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and Escherichia coli (Eco) RNAPs show that Fdx functions by inhibiting initiation of transcription7–10. RNAP forms two mobile pincers that surround DNA11,12 and Fdx inhibits initiation by jamming the pincers in an “open” state, preventing one pincer, the clamp, from closing on the DNA. This doorstop-like jamming results in failures both to melt promoter DNA and to secure the DNA in the enzyme’s active-site cleft. Although the general architecture of RNAP is similar for all cellular organisms, differences in the primary subunit sequences, peripheral subunits, or lineage-specific insertions that occur in bacterial RNAP13 could explain Fdx sensitivity. For example, Mtb RNAP is much more sensitive to Fdx than Eco RNAP7, and the essential transcription factor RbpA sensitizes Mtb to Fdx even further7. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration or IC50 is 0.2 μM for Mtb RNAP with full-length RbpA, 7 μM for Mtb RNAP lacking the RbpA–Fdx contacts, and 53 μM for Eco RNAP (Extended Data Table 1)7. However, Cdiff lacks RbpA leaving the molecular basis of Cdiff sensitivity unresolved.

Fig. 1. Fidaxomicin is a narrow-spectrum antimicrobial that inhibits RNAP.

a, Diagram illustrating how fidaxomicin specifically targets Cdiff without affecting gut commensals and thus reduces recurrence (upper circles). For CDI patients treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics (lower circles), the abundance of gut commensals drops simultaneously with Cdiff resulting in high rates of Cdiff recurrence. b, Chemical structure of Fdx. c, Cryo-EM structure of Cdiff EσA in complex with Fdx. The EσA model is colored by subunits according to the key, and the 3.26 Å cryo-EM map is represented in a white transparent surface. The cryo-EM density for Fdx is shown in the inset as a green transparent surface.

The pathogenicity and limited genetic tools for Cdiff complicate using Cdiff directly for structural and mechanistic studies of RNAP, with a single report of endogenous Cdiff RNAP purification yielding small amounts of enzyme with suboptimal activity14. To enable studies of Cdiff RNAP, we created a recombinant system in Eco that yields milligram quantities of Cdiff core RNAP (E) and also enables rapid mutagenesis (see methods and supplement). Cdiff housekeeping σΑ factor was also expressed in Eco, purified, and combined with core Cdiff RNAP to produce the holoenzyme (EσA). The purity, activity, and yield of EσA were suitable for structural and biochemical studies (Extended Data Fig. 1a, 1b and 1c).

To visualize the binding of Fdx to its clinical target, we used single particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to solve the structure of Cdiff EσA in complex with Fdx. We obtained a cryo-EM map representing a single structural class comprising Cdiff EσA and bound Fdx at 3.3 Å nominal resolution, with a local resolution of ~2.7–3 Å around the Fdx-binding pocket (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3, Extended Data Table 2)15. The structure reveals key features of the Cdiff EσA and provides the first view of a Clostridial EσA.

Cdiff RNAP contains a lineage-specific insert in the β lobe domain that resembles one found in RNAP from Bacillus subtilis (Bsub, a Firmicute like Cdiff), but distinct from the better-characterized inserts in Eco RNAP16–18. The Firmicute β insert corresponds to βi5 identified by sequence analysis13 and consists of two copies of the β-β’ module 2 (BBM2) protein fold whereas the β lobe insert in Eco RNAP occurs at a different position and corresponds to βi4 (Extended Data Fig. 4). Our structure revealed Cdiff βi5 (4–5 Å; Extended Data Fig. 3) at a position similar to Bsub βi5 17 but the Cdiff insert is larger (121 amino acids vs 99 amino acids in Bsub) (Extended Data Fig. 4). The function of the Firmicute βi5 is unknown and awaits further study but is unlikely to impact Fdx binding (located ~70 Å away) or activity.

Cdiff σA possesses all conserved regions of σ, which were located in the Cdiff EσA structure at locations similar to those seen for other bacterial housekeeping σ-factors (Extended Data Fig.5)7,19,20. Cryo-EM density was not visible for most of σ region 1 (residues 1–115 of the 150 residues in Cdiff region 1), as also seen with other bacterial holoenzymes characterized structurally7,20,21. Cdiff σA lacks the non-conserved region (NCR) insert between regions and 1 and 2 found in some other bacteria like Eco (Extended Data Fig. 5)16.

As seen in other RNAPs7,8,22, Fdx appears to stabilize the clamp pincer in an open state, but the Cdiff clamp is twisted slightly toward Fdx relative to the Mtb EσA structure with Fdx (Fig.2a). Opening and closing of RNAP’s pincers are required for transcription initiation11,22. Fdx binds Mtb RNAP at a hinge between two RNAP pincers (the β′ clamp and β lobe pincers), thus physically jamming the hinge and locking RNAP in an open conformation that is unable to form a stable initiation complex8,9. Fdx occupies the same location in the Cdiff EσA–Fdx structure, indicating that the hinge-jamming mechanism is widely conserved. However, the slight twisting of the Cdiff β′ clamp pincer relative to that observed in Fdx-bound Mtb RNAP (Fig. 2a) increases clamp–Fdx contacts (see below).

Fig. 2. Fdx binding and inhibition of the Cdiff EσA.

a, Clamp differences between Cdiff and Mtb RNAP. The Cdiff RNAP clamp (pink) is twisted (5.8°) towards Fdx compared with the Mtb RNAP–Fdx clamp (yellow) (PDB ID: 6BZO). The actinobacterial specific insert in the clamp is partially cropped. The clamp residues, β′K314 and β′M319, that interact with Fdx (shown in green spheres) in Cdiff but not Mtb RNAP are shown as red spheres. The zinc in the ZBD is shown as a blue sphere. b, The interactions between Fdx and Cdiff RNAP are shown. Hydrogen-bonding interactions are shown as black dashed lines. The cation-π interaction of β′R89 is shown with a red dashed line. Arches represent hydrophobic interactions. RNAP residues are colored corresponding to subunits: cyan (β) and pink (β′). The Fdx-contacting residues that are not present in the Mtb EσA–Fdx structure (pdb 6BZO) are marked with red circles. c, The sequence of the native Cdiff ribosomal RNAP rrnC promoter used in the in vitro transcription assay in d. The –10 and –35 promoter elements are shaded in purple and green, respectively. The abortive transcription reaction used to test Fdx effects is indicated below the sequence (*, [α-32P]GTP used to label the abortive product GpUpG). d, Fdx inhibits Cdiff EσA and Mtb RbpA-EσA similarly and ~100 times more effectively than Eco Eσ70. Error bars are standard deviations (SD) of three independent replicates (for some points, SD was smaller than the data symbols).

Fdx contacts six key structural components of Cdiff RNAP: β clamp, β′ switch region 2 (SW2), β switch region 3 (SW3), β switch region 4 (SW4), β′ zinc-binding-domain (ZBD), and β′ lid (Figs. 2b and 3). We compared the Fdx-binding determinants in Cdiff RNAP to those previously determined in Mtb RNAP7,8. Most of the interactions between Fdx and RNAP were conserved between the two species (Extended Data Fig. 6, Extended Data Table 3). In Cdiff RNAP (Mtb numbering in parentheses), Fdx formed direct hydrogen bonds or salt bridges with four residues βR1121 (K1101), β′K84 (R84), β′K86 (K86), and β′R326 (R412) and two water-mediated hydrogen bonds with β′D237 (E323) and σH294 (Q434). (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 6, and Extended Data Table 3). Fdx binding is also stabilized by a cation-π interaction between the β′R89 and the Fdx macrolide core C3–C5 double bond in both Mtb and Cdiff RNAPs. Cdiff RNAP residues known to confer Fdx-resistance when mutated (βV1143G, βV1143D, βV1143F, β′D237Y and βQ1074K23,24) were located within 5 Å of Fdx (Extended Data Fig. 6).

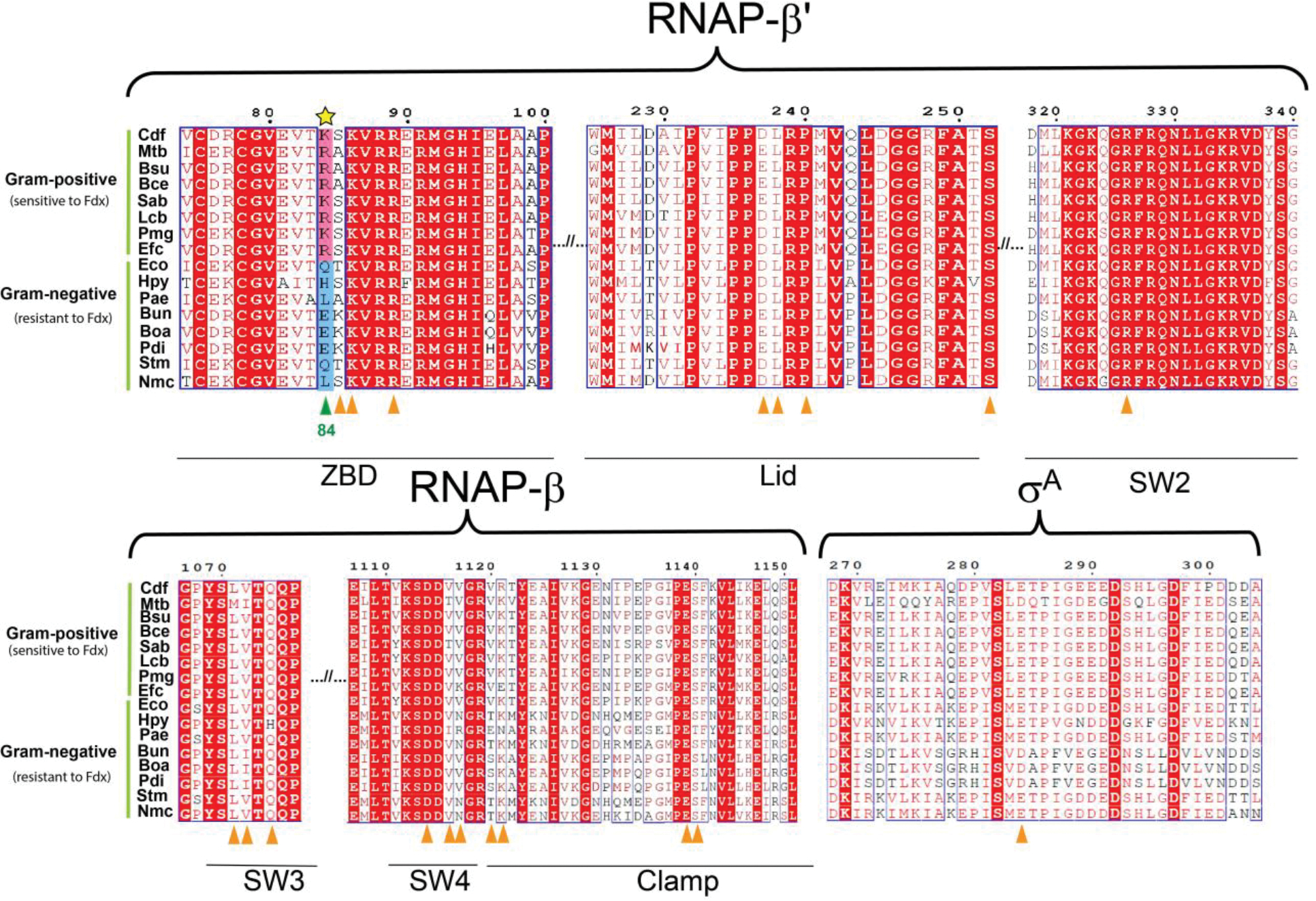

Fig. 3. Analysis of Fdx-interacting residues across bacterial lineages.

Cdiff RNAP EσA–Fdx is shown as a molecular surface for orientation (left inset). The boxed region is magnified on the right with RNAP subunits shown as α-carbon backbone worms, Fdx-interacting residues conserved between Mtb and Cdiff shown as side-chain sticks, and Fdx (green) shown as sticks. Non-carbon atoms are red (oxygen) and blue (nitrogen). The Mtb–Cdiff-conserved, Fdx-interacting residues shown in the cartoon structure are labeled under the sequence logos. Amino acids that make hydrophilic interactions with Fdx are labeled on the structure. Representative bacterial species with published Fdx MICs were used to make the logos25. See Extended Data Fig. 9 for detailed sequence alignments. Most Fdx-interacting residues are conserved except residues corresponding to Cdiff β′S85 and the sensitizer (yellow star corresponding to Cdiff β’K84).

Of particular interest, β′K84 in Cdiff RNAP forms a salt bridge with the oxygen on the phenolic group of Fdx (due to the acidity of phenol) whereas the corresponding residue (β′R84) in Mtb forms a cation-π interaction with the aromatic ring of the Fdx homodichloroorsellinic acid moiety (Fig. 2b). We propose that these coulombic interactions by β′K84 (β′R84) sensitize both RNAPs to tight Fdx binding (see comparison of individual residues in Cdiff and Mtb RNAPs that bind Fdx; Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7, Extended Data Table 3). Mtb RbpA, an essential transcriptional regulator in mycobacteria, lowers the IC50 of Fdx by a factor of 35 via Fdx contacts with two RbpA residues in the N-terminal region7. Cdiff RNAP lacks a RbpA homolog, but we observed four hydrophobic interactions between Fdx and Cdiff RNAP (with βT1073, β′M319, β′K314, and σL283) and one water-mediated hydrogen bonding interaction with σH294 that are not present with the corresponding Mtb RNAP residues (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig.6, Extended Data Table 3). Some of these new interactions (β′M319 and β′K314 in the clamp) with Fdx are created by the relatively increased rotation of the Cdiff RNAP clamp towards Fdx (Fig. 2a).

Gram-negative bacteria are more resistant to Fdx than gram-positive bacteria25–27. This dichotomy could reflect differences in membrane and cell-wall morphology, differences in RNAPs, or both. To compare the activity of Fdx against Cdiff and Mtb RNAP, we performed abortive transcription assays using purified RNAPs and the native Cdiff rrnC ribosomal RNA promoter (Fig. 2c)14. The IC50s of Fdx for Cdiff RNAP EσA (~0.2 μM) and Mtb EσA including RbpA (~0.3 μM) are similar, consistent with our structural observations (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 6). These IC50s are two orders of magnitude lower than that for E. coli σ70-holoenzyme (Eσ70) on the same DNA template (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 8), suggesting that the differences in RNAPs contribute significantly to the differences in MICs between Cdiff (a gram-positive) and gram-negative bacteria. This observation suggests that the Fdx-binding residues identified in Mtb and Cdiff RNAPs can be used as a reference to predict Fdx potency in other bacterial species, including gut commensals25.

We next used our Mtb and Cdiff RNAP–Fdx structures to predict the interactions responsible for the narrow spectrum activity of Fdx. Using sequence alignments of β′ and β from bacterial species with reported Fdx MICs25,27 (Extended Data Fig. 9), we found that the Fdx-binding residues identified in Mtb and Cdiff RNAP are mostly conserved among these divergent bacteria, except for the aforementioned β′K84 (β′R84 in Mtb) and β′S85 (β′A85 in Mtb). β′K84 and S85 are located in the ZBD. β′K84 forms a salt bridge with the likely ionized Fdx O13 whereas S85 Cβ forms a nonpolar interaction with the Fdx C32 methyl group (Figs. 1b, 3 and Extended Data Fig. 6, Extended Data Table 3). We focused on β′K84 because all species contain a Cβ at position 85 whereas position 84 displays an intriguingly divergent pattern among gut commensal bacteria (Extended Data Fig. 9). For gram-positive bacteria, which are hypersensitive to Fdx (MIC<0.125 μg/mL), the β′K84 position is always positively charged (K or R). However, for gram-negative bacteria, which are resistant to Fdx (MIC >32 μg/mL), β′K84 is replaced by a neutral residue (Q in Eco or L in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Neisseria meningitidis; Extended Data Fig. 9). Notably, in Bacteroidetes, which are highly resistant to Fdx (MIC >32 μg/mL, e.g., Bacteroides uniformis, Bacteroides ovatus, and Bacteroides distasonis), β′K84 is replaced by negatively charged glutamic acid (E). In an analysis of common species present in the human gut microbiota (Extended Data Table 4)28,29, β′K84 is replaced by E in Bacteroidetes (the most abundant bacteria30,31) and by neutral residues (Q, T, or S) in Proteobacteria (Figs. 4a, Extended Data Fig.10). We thus refer to β′K84 as the Fdx sensitizer and propose it is crucial for tight Fdx binding in two ways: first, by forming a salt bridge (a proton-mediated ionic interaction) between the positively charged ε-amino group of β′K84 and a negatively charged phenolic oxygen of Fdx; and second, by rigidifying the α-helix of the ZBD and thus facilitating backbone hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding interactions with downstream residues S85 (A85 in Mtb) and K86 (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 4. The sensitizer position (β′K84 in Cdiff RNAP) explains Fdx narrow-spectrum activity in the gut microbiota.

a, Sequence logos for the Fdx-interaction region of the β′ZBD is highly conserved among the four most common bacterial phyla in the human microbiota: Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria, except for the sensitizer position and C-adjacent residue (β′K84 and S85 in Cdiff RNAP). The logos were derived using 66 representative species in the human microbiota28,29 (Extended Data Fig. 10, Extended Data Table 4). b, Fdx effects on abortive transcription reveal that the β′K84E substitution increases resistance 10-fold, whereas β′K84Q and β′K84R have much lesser effects. c, Transcription assays with Eco Eσ70 show the β′Q94K substitution in Eco RNAP reduces Fdx IC50 by a factor of ~20 relative to the WT enzyme. d, Zone-of-inhibition assays with WT and β′R84E B. subtilis demonstrate that an R84-to-E change increases Fdx-resistance and establish this residue as a sensitizing determinant in vivo. The mutant (right) displayed reduced zones of inhibition relative to the WT (left) bacteria for Fdx but not for a control (spectinomycin; Spec). e, Zone-of-inhibition assays show that the β′Q94K substitution sensitizes E. coli to Fdx in the presence of the outer-membrane-weakening compound SPR741 (45 μM). E. coli WT (left) was not inhibited by high concentrations of Fdx (3mM), whereas the β′Q94K cells (right) gave inhibited zones at 250 μM.

We hypothesized that variation in the Fdx sensitizer plays a key role in determining the potency of Fdx activity on RNAP from different clades. To test this hypothesis, we constructed substitutions β′K84E, β′K84Q, and β′K84R in Cdiff RNAP and β′Q94K in Eco RNAP and then compared their inhibition by Fdx using the Cdiff rrnC abortive initiation assay (Figs. 4b, 4c, Extended Data Fig. 11). Fdx inhibits Cdiff wild-type (WT), β′K84Q, and β′K84R RNAPs at similar sub-μM concentrations. However, inhibition of Cdiff β′K84E RNAP requires a ten-fold higher concentration of Fdx than WT, indicating greater resistance to Fdx (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 11a). This result is consistent with our hypothesis that the negatively charged carboxyl group on the side chain of β′K84E repels the negative oxygen of Fdx and disrupts the polar interaction, whereas the β′K84Q must be less disruptive to Cdiff RNAP–Fdx interaction possibly because the glutamine is capable of forming a hydrogen bond with Fdx.

To test the effect of positive versus neutral charge at the Fdx sensitizer in the context of an RNAP that is relatively Fdx-resistant, we compared WT and β′Q94K Eco RNAPs. The Eco β′Q94K substitution creates a positive charge at the position and dramatically increases sensitivity to Fdx (the IC50 decreased by a factor of 20; Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 11b). This result indicates that the lack of positive charge at the sensitizer position is indeed a crucial contributor to resistance to Fdx in Proteobacteria and posed an interesting discrepancy with the lack of effect of the Cdiff β′K84Q substitution. We hypothesize that other differences between Cdiff and Eco RNAP such as the relative flexibilities of the ZBD and clamp allow Cdiff RNAP, but not Eco RNAP, to sustain stronger interactions when the key position is neutral (Q). However, when a negative charge (E) is present at the sensitizer position, the repulsion between the carboxylic side chain (present in Bacteroidetes) and the Fdx phenolic oxygen leads to Fdx-resistance.

To test whether the Fdx sensitizer is crucial for Fdx susceptibility in vivo, we introduced a point mutation (R84E) within the native rpoC gene of B. subtilis. B. subtilis belongs to the same phylum (Firmicutes) as Cdiff. Like Cdiff and Mtb, it has a positively charged residue (R) at the sensitizer position but is a genetically tractable model. The B. subtilis WT strain was readily inhibited by 10 μM Fdx whereas the rpoC-R84E mutant required higher concentrations (100 μM and above) for similar inhibition (Fig. 4d). Notably, at 500 μM Fdx, the inhibition zone for rpoC-R84E mutant remained significantly smaller than that for B. subtilis WT whereas a control (spectinomycin) that does not target RNAP gave equivalent-sized zones. We conclude that the Fdx-sensitizing residue in RNAP, K84 in Cdiff and R84 in B. subtilis, is a significant determinant of Fdx susceptibility in Firmicutes.

Similarly, to interrogate gram-negative bacteria lacking positive charge at the sensitizer position, we tested whether a β′Q94K substitution could endow Fdx sensitivity to E. coli in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 12a; see Methods). Given that the gram-negative outer membrane is a known barrier to Fdx, we sought to test whether Fdx resistance depends on the outer membrane barrier alone, the non-positively charged sensitizer residue on RNAP, or both using a well-characterized outer membrane weakener, SPR741 (related to the natural antibiotic colistin produced by a Firmicute)32,33. Neither SPR741 nor Fdx alone had large effects on E. coli (Extended Data Fig. 12b). However, clear zones of inhibition were observed for the rpoC-Q94K mutant only at Fdx concentrations from 0.25 mM to 3 mM in the presence of SPR741 but not for E. coli WT strain, even at the highest Fdx concentration (Fig. 4e). Although the extent to which outer membrane weakeners may be present in the gut microbiome is unknown, we note that colistin is just one of many natural antibiotics produced by competing microbes and that medicinal antibiotics are often administered in combination. We conclude that both the outer membrane and the lack of positive charge at the sensitizer position of RNAP contribute to Fdx resistance in a gram-negative bacteria under conditions likely to be relevant to the gut microbiome. Conversely, a positively-charged sensitizer (as found in Cdiff and Mtb) is crucial for conferring Fdx sensitivity. Hence our studies allow the rational optimization of Fdx, depending on the target pathogen. For example, one might be able to substitute the phenolic oxygen with a stronger acid to treat gram-positive pathogens or with a basic group to treat gram-negative pathogens.

In summary, our high-resolution structure of Cdiff RNAP EσA reveals features that are likely to be specific to Clostridia and, to some extent Firmicutes and gram-positive bacteria. Analysis of this structure, in combination with bioinformatics and structure-guided functional assays, revealed a “sensitizing” determinant for Fdx, which turns out to be a single amino-acid residue in the ZBD of the RNAP β’ subunit. This work sheds light on how Fdx selectively targets Cdiff versus beneficial gut commensals like Bacteroidetes. Although wide-spectrum antibiotics are broadly effective therapies, our results highlight the advantages of narrow-spectrum antibiotics to treat intestinal infections and likely other bacterial infections. Treatment by narrow-spectrum antibiotics would reduce widespread antibiotic resistance and reduce the side effects caused by the collateral eradication of the beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiome. Using a similar approach to that applied here, further elucidation of diverse bacterial RNAP structures and mechanisms can provide a blueprint for designer antibiotics that leverage natural microbial competition to combat pathogens more effectively.

Methods

Reagents and Materials

Antibiotics and chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Thermo-Fisher unless noted otherwise. SPR741 was purchased from Med Chem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). [α-32P]-GTP was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. GpU was from TriLink Biotechnologies. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. PCR amplification was performed using Q5 or OneTaq DNA polymerases (New England Biolabs). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were supplied by New England Biolabs. DNA sequencing was performed by Functional Biosciences ((Madison, WI, USA).

Protein Expression and Purification.

Cdiff σA

The Cdiff σA gene (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) entry: CD630_14550) was amplified from Cdiff 630 chromosomal DNA and cloned between NcoI and NheI sites of pET28a plasmid. A His10 tag with a Rhinovirus 3C protease recognition site was added to the N-terminus end of the σA gene to facilitate purification. Escherichia coli BL21(λDE3) cells were transformed with this plasmid and were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) overnight at 16 °C. The protein was affinity purified on a Ni2+-column (HiTrap IMAC HP, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The column was washed with 20 column volumes of wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM imidazole, and 1 mM dithiothreitol) to remove contaminating proteins, and the His-tagged protein was eluted with wash buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was cleaved with Rhinovirus 3C protease overnight, the cleaved complex was loaded onto a second Ni2+ column, and the flow-through was collected and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200, GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl, and 5 mM DTT. The eluted Cdiff σA were subsequently concentrated and stored in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.3 M NaCl, and 5 mM DTT at –80°C.

Cdiff RNAP

The Cdiff RNAP overexpression plasmid was constructed in multiple steps. First, the Cdiff 630 rpoA (KEGG: CD630_00980), rpoZ (KEGG: CD630_25871), rpoB (KEGG: CD630_00660), and rpoC (KEGG: CD630_00670) genes were codon-optimized for Eco using Gene Designer (ATUM, Inc.) and codon frequencies reported by Welch et al34. A strong ribosome-binding site (RBS) was designed for each gene using the Salis RBS design tools (https://www.denovodna.com/software/)35. DNA fragments containing the rpoA, rpoZ, rpoB and rpoC genes and the RBSs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and assembled into pET21 (Novagen) by Gibson assembly (NEB HiFi). To ensure 1:1 stoichiometry and inhibit assembly with the host Eco subunits, β and β′ were fused using a polypeptide linker (LARHGGSGA), a method previously used for overexpression of Mtb RNAP36. A His10 tag preceded by a Rhinovirus 3C protease cleavable site were added to the C-terminus of rpoC to facilitate purification, resulting in plasmid pXC026. The plasmids encoding Cdiff RNAP mutants (rpoC-K84E, K84R, and K84Q) were constructed by Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (NEB Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit Quick Protocol using pXC026 as the template. Overexpression of Cdiff RNAP yielded high levels of proteolysis and inclusion bodies in the conventional BL21 λDE3 strain. Yields of soluble, intact Cdiff RNAP were increased in E. coli B834(λDE3), a strain reported to overproduce intact Bacillus subtilis RNAP37. Cdiff core RNAP was co-overexpressed in E.coli B834(λDE3) (Novagen) overnight at 16°C for ∼16 h after induction with 0.3 mM IPTG in LB medium with 50 μg Kanamycin (Kan)/mL. The cell pellet was resuspended in the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X), Thermo Fisher), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cells were lysed by continuous flow through a French press (Avestin) and spun twice at 11,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C. DNA and RNAP were precipitated from the supernatant by gradual addition with mixing of polyethyleneimine (PEI) to 0.6% w/v final concentration. After centrifugation at 11,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C, the PEI pellets were washed three times with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.25 M NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, and 5% (v/v) glycerol, and the RNAP was then eluted three times with a solution of the same composition but with 1 M NaCl. The RNAP was precipitated overnight with gentle stiring at 4 °C after gradual addition of ammonium sulfate to 35% (w/v) final concentration. After centrifugation at 11,000 × g, 25 min, 4 °C, the RNAP was resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and subjected to Ni2+-affinity chromatography purification. The column was washed with 20 column volumes of wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM imidazole, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) to remove contaminating proteins, and eluted with wash buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was cleaved with Rhinovirus 3C protease overnight. The cleaved protein was loaded onto a second Ni2+ column, and the flow-through was collected, concentrated, dialyzed overnight in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl, and 1 mM DTT, and then stored at –80°C.

In vitro Transcription Assays

The Cdiff rrnC DNA template (see below for sequences) was PCR amplified from genomic DNA of Cdiff 630, phenol extracted, diluted to 200 nM in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), and stored at −20°C. Transcription assays were performed in 20 μL reactions as described previously38. Briefly, 50 nM of Cdiff or Eco WT or mutant RNAP EσA was combined in transcription buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.9, 170 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5 μg bovine serum albumin/mL and 0.1 mM EDTA) with different concentrations of Fdx (0.01–500 μM; final reaction volumes after addition of DNA and NTPs were 20 μL). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min to allow for the antibiotic to bind. The dsDNA fragment containing the Cdiff rrnC promoter (GenBank: CP010905.2) was added (10 nM final) to each tube and the samples were incubated for an additional 15 min at 37 °C to allow the formation of the RNAP open complex. Dinucleotide (GpU, 20 μM) was added and incubation was continued for 10 min. Transcription was initiated by addition of [α-32P]GTP to a final concentration of 20 μM (3.1 Ci/mmol), allowed to proceed for 10 min at 37 °C, and stopped by the addition of 20 μL of 2X stop buffer (90 mM Tris-borate buffer pH 8.3, 8 M urea, 30 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol). The samples were heated at 95 °C for 1 min and then loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel [20% Acrylamide/Bis acrylamide (19:1), 6 M urea, and 45 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.3, 1.25 mM Na2EDTA]. Transcription products were visualized by phosphorimaging using a Typhoon FLA 9000 (GE Healthcare) and quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). Quantified values were plotted in PRISM and the IC50 was calculated from three independent data sets. The full sequences of the fragments (initiation sites in lowercase, –35 and –10 elements in bold) used for transcription are as follows:

rrnC (sequences used as PCR primers are underlined):

AATAGCTTGTATTAAAGCAGTTAAAATGCATTAATATAGGCTATTTTTATTTTGACAAAAAAATATTTAAAATAAAAGTTAAAAAGTTGTTGACTTAGAATAATATAGATGATATTATATATGAgtgCCCAAAAGGAGCACCAAAATAAGACAAAAGAACTTTGAAAATTAAACAGTA

Preparation of WT Cdiff EσA for cryo-EM

The RNAP core was incubated with 15 molar excess of σA for 15 min at 37 °C and 45 min at 4 °C. The complex was then purified over a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) in gel filtration buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM K-glutamate, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM DTT). The eluted RNAP EσA was concentrated to 6 mg/mL (14 μM) by centrifugal filtration (Amicon Ultra). EσA was mixed with 100 μM final concentration of Fdx (10 mM stock solution in DMSO) and incubated for 15 minutes at 4 °C.

Cryo-EM grid preparation

Before freezing cryo-EM grids, octyl β-D-glucopyranoside was added to the samples to a final concentration of 0.1%8. C-flat holey carbon grids (CF-1.2/1.3–4Au, Protochips, Morrisville, NC) were glow-discharged for 20 s before the application of 3.5 μL of the samples. Using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific Electron Microscopy, Hillsboro, OR), grids were blotted and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane with 100% chamber humidity at 22 °C.

Cryo-EM data acquisition and processing

Structural biology software was accessed through the SBGrid consortium39. Cdiff EσA with Fdx grids were imaged using a 300 keV Titan Krios (Thermo Fisher Scientific Electron Microscopy) equipped with a K3 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA). Dose-fractionated movies were recorded in counting mode using Leginon at a nominal pixel size of 1.083 Å/px (micrograph dimensions of 5,760 × 4,092 px) over a nominal defocus range of −1 μm to −2.5 μm40. Movies were recorded in “counting mode” (native K3 camera binning 2) with a dose rate of 30 electrons/physical pixel/s over a total exposure of 2 s (50 subframes of 0.04 s) to give a total dose of ~51 e-/Å^2. A total of 6,930 movies were collected. Dose-fractionated movies were gain-normalized, drift-corrected, summed, and dose-weighted using MotionCor241. The contrast transfer function was estimated for each summed image using Patch CTF module in cryoSPARC v2.15.042. cryoSPARC Blob Picker was used to pick particles (no template was supplied). A total of 2,502,242 particles were picked and extracted from the dose-weighted images in cryoSPARC using a box size of 256 pixels. Particles were sorted using cryoSPARC 2D classification (number of classes, N=50), resulting in 2,415,902 curated particles. Initial models (Ref 1: RNAP, Ref 2: decoy 1, Ref 3: decoy 2) were generated using cryoSPARC Ab initio Reconstruction42 on a subset of 81,734 particles. Particles were further curated using Ref 1-3 as 3D templates for cryoSPARC Heterogeneous Refinement (N=6), resulting in the following: class1 (Ref 1), 464,460 particles; class2 (Ref 1), 641,091 particles; class3 (Ref 2), 296,508 particles; class4 (Ref 2), 296,203 particles; class5 (Ref 3), 390,575 particles; class6 (Ref 3), 327,065 particles. Particles from class1 and class2 were combined and further curated with another round of Heterogeneous Refinement (N=6), resulting in the following: class1 (Ref 1), 262,185 particles; class2 (Ref 1), 394,040 particles; class3 (Ref 2), 110,023 particles; class4 (Ref 2), 110,743 particles; class5 (Ref 3), 104,013 particles; class6 (Ref 3), 124,547 particles. Curated particles from class 2 were refined using cryoSPARC Non-uniform Refinement 42 and then further processed using RELION 3.1-beta Bayesian Polishing43. Per-particle CTFs were estimated for the polished particles using cryoSPARC Homogeneous Refinement with global and local CTF refinement enable42. These particles were further curated using cryoSPARC Heterogeneous Refinement (N=3), resulting in the following: class1 (Ref 1), 85,470 particles; class2 (Ref 1), 231,310 particles; class3 (Ref 1), 77,250 particles. Particles from class2 were selected for a subsequent cryoSPARC Heterogeneous Refinement (N=3), resulting in the following: class1 (Ref 1), 19,282 particles; class2 (Ref 1), 182,390 particles; class3 (Ref 1), 29,638 particles. Particles in class2 were refined using cryoSPARC Non-uniform Refinement44 resulting in final 3D reconstruction containing 182,390 particles with nominal resolution of 3.26 Å. Local resolution calculations were generated using blocres and blocfilt from the Bsoft package45.

Model building and refinement

A homology model for Cdiff EσA was derived using SWISS-MODEL46 and PDBs: 5VI520 for αI and αII; 6BZO7 for β, β’, and σA; and 6FLQ47 for ω. The homology model was manually fit into the cryo-EM density maps using Chimera48 and rigid-body and real-space refined using Phenix49. A model of Fdx was used from the previous structure PDB ID: 6BZO to place in the cryo-EM map7. Rigid body refinement for rigid domains of RNAP was performed in PHENIX. The model was then manually adjusted in Coot50 and followed by all-atom and B-factor refinement with Ramachandran and secondary structure restraints in PHENIX. The BBM2 modules were built using AlphaFold2 model51. The refined model was ‘shaken’ by introducing random shifts to the atomic coordinates with RMSD of 0.163 Å in phenix.pdbtools49. The shaken model was refined into half-map1 and FSCs were calculated between the refined shaken model and half-map1 (FSChalf1 or work), half-map2 (FSChalf2 or free, not used for refinement), and combined (full) maps using phenix.mtriage52. Unmasked log files were plotted in PRISM and the FSC-0.5 was calculated for the full map.

Reporting summary:

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data and materials availability:

Cryo-EM maps and atomic models have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Database (EMDB accession codes 23210) and the Protein Database (PDB accession codes 7L7B). Unique materials are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Construction of E. coli and B. subtilis mutant strain:

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the E. coli rpoC IPTG-inducible expression plasmid pRL66253 using Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit Quick Protocol) to construct pRL662-Q94K. Plasmids pRL662 and pRL662-Q94K were each transformed into the temperature-sensitive strain RL602 (rpoC(Am) supD43,74(Ts))54, which is unable to produce RNAP and grow at ≥39 °C.

To introduce the rpoC-R84E mutation into B. subtilis, a CRISPR-Cas9 method55was used to produce strain RL3914. Upstream and downstream fragments (1 kb each) flanking the point mutation site were PCR amplified and then combined with the guide RNA segment (5′-AGTTTGTGACCGCTGCGGAGTCGAAGTAACA-3′) using annealed, complementary oligonucleotides (IDT) in a plasmid backbone from pJW557 (gift of Dr. Jue Wang, UW-Madison) as described55. The resulting plasmid, pXC052, was then transformed into RL3915 (an E. coli recA+ strain) for multimerization. Multimerized pXC052 was obtained by conventional plasmid miniprep, and transformed into B. subtilis 168, and incubated at 30 °C overnight on LB plate with 100 μg/ml spectinomycin added. Single colonies were picked the next day and cured of plasmid by growth at 45°C for 24 hours on LB plate. The genomic rpoC-R84E point mutation was verified by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Fdx inhibition assay on agar plates:

Fdx zone-of-inhibition assays for both E. coli and B. subtilis were performed on agar plates using the soft-agar overlay technique56. Single colonies of E. coli RL602/pRL662 and RL602/pRL662-Q94K strains were inoculated into LB broth (5 mL) containing 100 μg ampicillin/mL plus 0.3 mM IPTG (to induce expression of rpoC) and incubated at 42 °C degree with shaking to apparent OD600 of 0.4–0.6. Approximately 0.05 OD600 units of cells were then mixed with 4 mL soft overlay agar (0.4 %) at 55 °C, poured onto an LB 1.5% agar plate containing 100 μg ampicillin/mL and 0.5 mM IPTG (to maintain rpoC expression), and allowed to solidify at 25 °C. Test compounds in DMSO or H2O (3 μL) were then spotted onto solidified overlay agar and the plates were incubated overnight at 42 °C before scoring the zones of inhibition. For the B. subtilis168 (WT) and rpoC-R84E strains, the cell cultures and bottom agar did not contain antibiotic or IPTG and the plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C before scoring. Fdx, Rif, and SPR741 were prepared in 100% DMSO. Spec and Kan were prepared in H2O.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Overexpression and purification of Cdiff RNAP.

a, pXC026, overexpression plasmid for the Cdiff rpoA, rpoZ, rpoB, and rpoC genes (encoding the α, ω, β, and β′ subunits of Cdiff RNAP, respectively). The β and β′ subunits were fused with an inter-subunit 10-amino-acid (aa) linker (LARHVGGSGA) and a C-terminal Rhinovirus 3C protease-cleavable His10 tag. b, (Top) Size-exclusion chromatography profile for the assembled Cdiff RNAP EσA. (Bottom) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of individual fractions from major peaks. RNAP subunits are labeled on the right of the gel. Cdiff RNAP for biochemistry and structural biology was taken from pooled fractions of the second peak. c, Abortive transcription assay with Cdiff core and EσA using the Cdiff rrnC promoter as DNA template. The transcriptional activity of Cdiff EσA was inhibited with increasing concentrations of Fdx. Lane 1, Cdiff RNAP core; lane 2, Cdiff EσA; lane 3, Cdiff EσA with 0.2 μM Fdx added; lane 4, Cdiff EσA with 2 μM Fdx added.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Cryo-EM processing pipeline.

Flow chart showing the image-processing pipeline for the cryo-EM data of Cdiff EσA/Fdx complexes, starting with 6,930 dose-fractionated movies collected on a 300-keV Titan Krios (FEI) equipped with a K3 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan). Movies were frame-aligned and summed using MotionCor239. CTF estimation for each micrograph was calculated with cryoSPARC240. A representative micrograph is shown following processing by MotionCor239. Particles were auto-picked from each micrograph with cryoSPARC240 Blob Picker and then sorted by 2D classification using cryoSPARC2 to assess quality. The selected classes from the 2D classification are shown. After picking and cleaning by 2D classification, the dataset contained 2,415,902 particles. A subset of particles was used to generate an ab initio templates in cryoSPARC2 and 3D heterogeneous refinement was performed with these templates using cryoSPARC240. One major, high-resolution class emerged, which was polished using RELION41 and further cleaned with two more 3D heterogenous refinements. The final 182,390 particles were refined using cryoSPARC Non-Uniform refinement42.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Cryo-EM analysis.

a, Top left, the 3.26 Å-resolution cryo-EM density map of Cdiff EσA/Fdx. Top right, a cross-section of the structure, showing the Fdx. Bottom, same views as above, but colored by local resolution, The boxed region is magnified and displayed as an inset. Density for Fdx is outlined in red15. b, Gold-standard FSC plots of the Cdiff EσA/Fdx complex from cryoSPARC40. The dotted line represents the gold-standard 0.143 FSC cutoff which indicates a nominal resolution of 3.26 Å. c, Angular distribution calculated in cryoSPARC for Cdiff EσA /Fdx particle projections. Heat map shows number of particles for each viewing angle (less = blue, more = red)40. d, Cross-validation FSC plots for map-to-model fitting were calculated between the refined structure of Cdiff EσA/Fdx and the half-map used for refinement (work, red), the other half-map (free, blue), and the full map (black). The dotted black line represents the 0.5 FSC cutoff determined for the full map49.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Differences between Cdiff and other bacterial RNAPs.

The lineage-specific β inserts are shown for Cdiff RNAP in dark blue, Eco RNAP in red16 (PDB ID:4LK1), Bsub RNAP in green17 (PDB ID:6ZCA). The Fdx is shown in green spheres, and the active site Mg2+ is shown as a yellow sphere. Superimposition of the RNAPs from each organism was performed in PyMOL. Only the Cdiff EσA is shown.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Differences in σA–Fdx contacts between Cdiff and Mtb and σA sequence alignment.

a, Conserved regions of Cdiff σA compared to Mtb σA and Eco σ70. Mtb σA has a much shorter σA NCR than Eco σ70, but the residues in the short Mtb NCR that contact RbpA are not present in either Cdiff or Eco50. Mtb RbpA contacts Fdx whereas Cdiff σA makes more contacts to Fdx than does Mtb σA. Black arrows indicate RpbA- σA contacts whereas colored arrows indicate Fdx contacts to σA and RpbA, which includes one shared contact between Mtb and Cdiff σA (red arrow). b, Amino acid-sequence alignment of σA for diverse representatives of bacteria species. Identical residues are highlighted in yellow. Gaps are indicated by dashed lines. Conserved σ regions are labeled underneath the alignment. The three letter species code is as follows: Cdf, Clostridioides difficile; Bsu, Bacillus subtilis; Bun, Bacteroides uniformis; Eco, Escherichia coli; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Fdx binding residues in Mtb RbpA-EσA and Cdiff EσA.

Ligplot51 was used to determine contacts between Fdx and Mtb RbpA-EσA (left) and Cdiff EσA (right). Cyan sphere, H2O; green dashed line, hydrogen bond or salt bridge; red arc, van der Waals interactions; red dashed line, cation-π interactions. Note that in ligplot of the Cdiff EσA/Fdx interactions, V1143 (discussed in the text as one of the residues when mutated cause Fdx-resistance) did not make the distance cutoff (4.5 Å) as it was located 4.7 Å away from Fdx. The RNAP β, β’ and σA residues are in cyan, pink, and orange respectively. The two Mtb RbpA residues (E17, R10) that interact with Fdx are colored in purple and indicated in the text. The Fdx-interacting residues that do not have corresponding interactions between Cdiff and Mtb are highlighted in red circles.

Extended Data Fig. 7. The cryo-EM density map of residues interacting with Fdx.

Coloring of the residues is consistent with RNAP subunits coloring in Fig. 3, the stick model and cryo-EM densities are color-coded as follows: Pink: β-subunit, cyan: β′- subunit, and orange: σA. Water molecules are shown as red spheres. The residues that form hydrogen bonds (black dotted line) with Fdx are labeled.

Extended Data Fig. 8. In vitro abortive transcription assays used to determine Fdx IC50 of Cdiff and Mtb EσAand EcoEσ70 related to Fig. 2d.

Abortive 32P-RNA products (GpUpG) synthesized on Cdiff rrnC promoter were quantified in the presence of increasing concentrations of Fdx. For each EσA (or Eσ70), three independent experiments were performed and analyzed on the same gel.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Comparative sequence alignment of key structural components of RNAPs that interact with Fdx between Fdx-resistant and sensitive bacteria.

The Fdx interacting regions are labeled on the top of sequence alignment. Locations of residues contacting Fdx in both Cdiff and Mtb are labeled by triangles underneath sequences. For gram-positive bacteria that are sensitive to Fdx, the corresponding residue at Cdiff β′K84 is either K or R, which is highlighted in pink background. For gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to Fdx, the residue at β′K84 is neutral Q, L, or negative E, which is highlighted in blue background. Conserved residues are shown as white letters on a red background, and similar residues are shown as red letters in blue boxes. Cdf, Clostridioides difficile; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Bsu, Bacillus subtilis; Bce, Bacillus cereus, Sab, Staphylococcus aureus; Lcb, Lactobacillus casei; Pmg, Peptococcus magna; Efc, Enterococcus faecium; Eco, Escherichia coli; Hpy, Helicobacter pylori; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Bun, Bacteroides uniformis; Boa, Bacteroides ovatus; Pdi, Parabacteroides distasonis; Stm, Salmonella Choleraesuis; Nmc, Neisseria meningitidis.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Phylogenetic tree demonstrating the clade-specific distribution of the identity of the Fdx-sensitizer.

The tree displays the identity of the amino acid corresponding to position β′K84 of Cdiff in the most common species from human gut microbiota. Bacterial species were largely picked from 28 and 29. The tree was built from 66 small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences by using RaxML52 and iTol53. Species with experimentally confirmed resistance (MIC > 32 μg/mL) and sensitivity (MIC < 0.125 μg/mL) to Fdx are marked with solid and open orange circle respectively25. The amino acid sequence at β′K84 position for corresponding bacteria phyla is denoted by capital letters. The detailed bacterial species are listed in Extended Dada Table 4.

Extended Data Fig. 11. In vitro abortive transcription assays measuring Fdx IC50 on Cdiff and Eco WT and mutant holo enzymes. a, Transcription assays for Cdiff WT, β′K94E and β′K84Q EσAs related to Fig. 4b.

The Cdiff rrnC promoter (Fig. 2c) was used as a template. b, Transcription assays for Eco WT and β’Q94K Eσ70s related to Fig. 4c. The same Cdiff rrnC promoter was used. For each RNAP, three independent experiments were performed and analyzed on the same gel.

Extended Data Fig.12. In vivo assays on agar plates for E. coli WT and Q94K mutant strains.

a. Temperature-sensitive strain RL602 was transformed with control plasmid pRL662 encoding no rpoC, WT rpoC and mutant rpoC-Q94K. Strains were grown overnight at 40 °C. Bacteria containing plasmids expressing rpoC WT and Q94K grew well while the empty plasmid does not cell support growth. b. Antibiotic inhibition assays using E. coli rpoC WT and mutant strains from panel (a). Antibiotics in 3 μL DMSO (Fdx, SPR741, and Rif) or water (Kan) were pipetted onto overlay soft agar containing the bacteria (see Methods). SPR741 did not inhibit cell growth but increased the potency of Rif and Fdx, suggesting that it increased antibiotic diffusion into the cells. Rif (± SPR741) and Kan, an antibiotic targeting ribosomes rather than RNAP and not affected by SPR741, equally inhibited the WT and mutant Q94K strains. In contrast, Fdx potently inhibited only the mutant strain, establishing that the Q94E mutation conferred specific sensitivity to Fdx.

Extended Data Table 1.

Antimicrobial efficiency of Fdx on various species.

Extended Data Table 2.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics

|

Cdiff EσA + Fdx PDB 7L7B |

|

|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | |

| Magnification | 81,000 |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 |

| Electron exposure (e-/Å2) | 51 |

| Defocus range (μm) | 0.8–2.7 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.083 |

| Symmetry imposed | C1 |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 2,502,242 |

| Final particle images (no.) | 182,390 |

| Map resolution (Å) FSC threshold 0.143 |

3.26 |

| Map resolution range (Å) | 2.8–6.6 |

| Refinement | |

| Initial models used (PDB code) | 6BZO |

| Model resolution range (Å) | 2.7–5.5 |

| Map sharpening B factor (A2) | 89.9 |

| Model composition | |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 24,713 |

| Protein residues | 3125 |

| Ligands | 4 (Fdx, Mg2+, 2 Zn2+) |

| B factors (A2) | |

| Protein | 131.24 |

| Ligands | 112.25 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (o) | 0.703 |

| Validation | |

| MolProbity score | 3.23 |

| Clashscore | 29.04 |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 10.34 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 91.19 |

| Allowed (%) | 8.81 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 |

Extended Data Table 3.

Complete list of Fdx interacting residues in Cdiff and Mtb RNAP EσA and comparison for those in Eco, B. ovatus, and B. uniformis

| Region | M. tuberculosis | C. difficile | E. coli | B. ovatus | B. uniformis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| SW3 | β-M1051 √ | β-L1071 √ | L | L | L |

|

| |||||

| SW3 | β-I1052 √ | β-V1072 √ | I | I | I |

|

| |||||

| SW3 | β-Q1054 √ | β-Q1074 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| SW4 | β-D1094 √ | β-D1114 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| SW4 | β-T1096 √ | β-V1116 √ | V | V | V |

|

| |||||

| SW4 | β-V1097 √ | β-V1117 √ | N | V | V |

|

| |||||

| Clamp | β-V1100 √ | β-V1120 √ | T | S | S |

|

| |||||

| Clamp | β-K1101 √ | β-R1121 √ | K | K | K |

|

| |||||

| Clamp | β-E1119 √ | β-E1139 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| Clamp | β-S1120 √ | β-S1140 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| ZBD | β’-R84=HOH √ | β’-K84 √ | Q | E | E |

|

| |||||

| ZBD | β’-A85 √ | β’-S85 √ | T | K | K |

|

| |||||

| ZBD | β’-K86 √ | β’-K86 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| ZBD | β’-R89 √ | β’-R89 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| Lid | β’-E323 √ | β’-D237=HOH √ | D | E | E |

|

| |||||

| Lid | β’-L324 √ | β’-L238 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| Lid | β’-P326 √ | β’-P240 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| Lid | β’-S338 √ | β’-S252 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| SW2 | β’-R412 √ | β’-R326 √ | * | * | * |

|

| |||||

| σ-linker | σ-D424 √ | σ-E284 √ | E | D | D |

|

| |||||

| RbpA | R-R10 √ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| R-E17=HOH √ | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

|

| |||||

| SW3 | β -T1053 X | β-T1073 √ | * | * | * |

| Clamp | β’-K400(rotamer) X | β’-K314 | * | * | * |

| Clamp | β’-D404=HOH√ | β’-D318 X | * | * | * |

| SW2 | β’-L405 X | β’-M319 √ | M | S | S |

| SW2 | β’-Q415=HOH√ | β’-Q329 X | * | * | * |

| σ-linker | σ-L423 X | σ-L283 √ | M | V | V |

| σ-linker | σ-Q434 X | √σ-H294=HOH √ | H | S | S |

| σ-linker | σ-V445 √ | √σ-P305 X | E | P | P |

√- van der wall/hydrophobic √- Salt-bridge or H bond √- cation-pi X no corresponding interactions

identical residues; grey, similar residues; magenta, distinguished residues

Extended Data Table 4. List of 66 common bacterial species in human gut profile, related to Fig. 4a.

MICs, when reported, are listed. N/A means Not Applicable due to the absence of published values.

| Species | Phylum | AA at β’K84 | Published MIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides vulgatus | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides uniformis | Bacteroidetes | E | 32 μg/mL25 |

| Bacteroides sp. | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides xylanisolvens | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides ovatus | Bacteroidetes | E | 32 μg/ml25 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides dorei | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Parabacteroides distasonis | Bacteroidetes | E | 32 μg/ml25 |

| Parabacteroides merdae | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides caccae | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides stercoris | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides cellulosilyticus | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides eggerthii | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides plebeius | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides coprocola | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides coprophilus | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Bacteroidetes | E | > 32 μg/ml25 |

| Alistipes putredinis | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Parabacteroides johnsonii | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Prevotella copri | Bacteroidetes | E | N/A |

| Anaerotruncus colihominis | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Blautia hansenii | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Blautia obeum | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Butyrivibrio crossotus | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Catenibacterium mitsuokai | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Intestinibacter bartlettii | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Clostridium bolteae | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Clostridium leptum | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Clostridium methylpentosum | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Clostridium scindens | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Clostridium sp. | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Clostridium nexile | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Clostridium asparagiforme | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Clostridium bartlettii | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Coprococcus comes | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Coprococcus eutactus | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Dorea formicigenerans | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Dorea longicatena | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Firmicutes | R | 4 μg/mL25 |

| Eubacterium(Holdemanella) biforme | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Eubacterium hallii | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Eubacterium rectale | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Eubacterium siraeum | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Eubacterium ventriosum | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Holdemania filiformis | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Lactobacillus casei | Firmicutes | R | 1 μg/mL25 |

| Mollicutes bacterium | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Roseburia intestinalis | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Ruminococcus bromii | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Ruminococcus gnavus | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Ruminococcus lactaris | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Ruminococcus sp | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Ruminococcus torques | Firmicutes | K | N/A |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Subdoligranulum variabile | Firmicutes | R | N/A |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Actinobacteria | K | N/A |

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum | Actinobacteria | K | N/A |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Actinobacteria | K | N/A |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum | Actinobacteria | K | N/A |

| Gordonibacter pamelaeae | Actinobacteria | R | N/A |

| Escherichia coli | Proteobacteria | Q | >32 μg/mL25 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Proteobacteria | Q | >32 μg/mL25 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | Proteobacteria | Q | 64 μg/mL25 |

| Helicobacter bilis | Proteobacteria | T | N/A |

| Helicobacter canadensis | Proteobacteria | S | N/A |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Seth Darst for helpful discussions during this study, Rachel Mooney for providing σ 70 protein for transcription assays, Jue Wang for providing plasmid pJW557, and Megan Young and Jin Yang for guidance in B. subtilis genetics. We thank Mark Ebrahim, Johanna Sotiris, and Honkit Ng at The Rockefeller University Evelyn Gruss Lipper Cryo-electron Microscopy Resource Center. Some of this work was performed at the Simons Electron Microscopy Center and National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy located at the New York Structural Biology Center, supported by grants from the Simons Foundation (SF349247), NYSTAR, the Agouron Institute (F00316), and the NIH (GM103310, OD019994). We thank Ed Eng and Kashyap Maruthi for collecting cryo-EM data. This research was supported by grants from the NIH to R.L. (GM38660) and E.A.C. (GM114450).

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.(https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf, 2019).

- 2.Louie TJ et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 364, 422–431, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910812 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford T, Huesgen E & Danziger L Fidaxomicin: a novel macrocyclic antibiotic for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Health Syst Pharm 69, 933–943, doi: 10.2146/ajhp110371 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louie TJ, Emery J, Krulicki W, Byrne B & Mah M OPT-80 eliminates Clostridium difficile and is sparing of bacteroides species during treatment of C. difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53, 261–263, doi: 10.1128/AAC.01443-07 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YJ et al. Protective Factors in the Intestinal Microbiome Against Clostridium difficile Infection in Recipients of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J Infect Dis 215, 1117–1123, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix011 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent C & Manges AR Antimicrobial Use, Human Gut Microbiota and Clostridium difficile Colonization and Infection. Antibiotics (Basel) 4, 230–253, doi: 10.3390/antibiotics4030230 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyaci H et al. Fidaxomicin jams Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase motions needed for initiation via RbpA contacts. Elife 7, doi: 10.7554/eLife.34823 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin W et al. Structural Basis of Transcription Inhibition by Fidaxomicin (Lipiarmycin A3). Mol Cell 70, 60–71 e15, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.026 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morichaud Z, Chaloin L & Brodolin K Regions 1.2 and 3.2 of the RNA Polymerase sigma Subunit Promote DNA Melting and Attenuate Action of the Antibiotic Lipiarmycin. J Mol Biol 428, 463–476, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.017 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tupin A, Gualtieri M, Leonetti JP & Brodolin K The transcription inhibitor lipiarmycin blocks DNA fitting into the RNA polymerase catalytic site. EMBO J 29, 2527–2537, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.135 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyaci H, Chen J, Jansen R, Darst SA & Campbell EA Structures of an RNA polymerase promoter melting intermediate elucidate DNA unwinding. Nature 565, 382–385, doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0840-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Boyaci H & Campbell EA Diverse and unified mechanisms of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 19, 95–109, doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00450-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane WJ & Darst SA Molecular evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases: sequence analysis. J Mol Biol 395, 671–685, doi:S0022-2836(09)01321-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.062 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mani N, Dupuy B & Sonenshein AL Isolation of RNA polymerase from Clostridium difficile and characterization of glutamate dehydrogenase and rRNA gene promoters in vitro and in vivo. J Bacteriol 188, 96–102, doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.96-102.2006 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardone G, Heymann JB & Steven AC One number does not fit all: mapping local variations in resolution in cryo-EM reconstructions. J Struct Biol 184, 226–236, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.08.002 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae B et al. Phage T7 Gp2 inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase involves misappropriation of sigma70 domain 1.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 19772–19777, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314576110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pei HH et al. The delta subunit and NTPase HelD institute a two-pronged mechanism for RNA polymerase recycling. Nat Commun 11, 6418, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20159-3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang C et al. The bacterial multidrug resistance regulator BmrR distorts promoter DNA to activate transcription. Nat Commun 11, 6284, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20134-y (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell EA et al. Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol Cell 9, 527–539, doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00470-7 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubin EA et al. Structure and function of the mycobacterial transcription initiation complex with the essential regulator RbpA. Elife 6, doi: 10.7554/eLife.22520 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J et al. 6S RNA Mimics B-Form DNA to Regulate Escherichia coli RNA Polymerase. Mol Cell 68, 388–397 e386, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.006 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feklistov A et al. RNA polymerase motions during promoter melting. Science 356, 863–866, doi: 10.1126/science.aam7858 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babakhani F, Seddon J & Sears P Comparative microbiological studies of transcription inhibitors fidaxomicin and the rifamycins in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 2934–2937, doi: 10.1128/AAC.02572-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuehne SA et al. Characterization of the impact of rpoB mutations on the in vitro and in vivo competitive fitness of Clostridium difficile and susceptibility to fidaxomicin. J Antimicrob Chemother 73, 973–980, doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx486 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein EJ, Babakhani F & Citron DM Antimicrobial activities of fidaxomicin. Clin Infect Dis 55 Suppl 2, S143–148, doi: 10.1093/cid/cis339 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurabachew M et al. Lipiarmycin targets RNA polymerase and has good activity against multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 62, 713–719, doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn269 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava A et al. New target for inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase: ‘switch region’. Curr Opin Microbiol 14, 532–543, doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.030 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forster SC et al. A human gut bacterial genome and culture collection for improved metagenomic analyses. Nat Biotechnol 37, 186–192, doi: 10.1038/s41587-018-0009-7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin J et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65, doi: 10.1038/nature08821 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wexler AG & Goodman AL An insider’s perspective: Bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat Microbiol 2, 17026, doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.26 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King CH et al. Baseline human gut microbiota profile in healthy people and standard reporting template. PLoS One 14, e0206484, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206484 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbett D et al. Potentiation of Antibiotic Activity by a Novel Cationic Peptide: Potency and Spectrum of Activity of SPR741. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61, doi: 10.1128/AAC.00200-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaara M et al. A novel polymyxin derivative that lacks the fatty acid tail and carries only three positive charges has strong synergism with agents excluded by the intact outer membrane. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54, 3341–3346, doi: 10.1128/AAC.01439-09 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 34.Welch M et al. Design parameters to control synthetic gene expression in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 4, e7002, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007002 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salis HM, Mirsky EA & Voigt CA Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol 27, 946–950, doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czyz A, Mooney RA, Iaconi A & Landick R Mycobacterial RNA polymerase requires a U-tract at intrinsic terminators and is aided by NusG at suboptimal terminators. Mbio 5, e00931, doi: 10.1128/mBio.00931-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X & Lewis PJ Overproduction and purification of recombinant Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. Protein Expr Purif 59, 86–93, doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.01.006 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis E, Chen J, Leon K, Darst SA & Campbell EA Mycobacterial RNA polymerase forms unstable open promoter complexes that are stabilized by CarD. Nucleic Acids Res 43, 433–445, doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1231 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morin A et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. Elife 2, e01456, doi: 10.7554/eLife.01456 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suloway C et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J Struct Biol 151, 41–60, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng SQ et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods 14, 331–332, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ & Brubaker MA cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14, 290–296, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zivanov J et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife 7, doi: 10.7554/eLife.42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punjani A, Zhang H & Fleet DJ Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat Methods 17, 1214–1221, doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-00990-8 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heymann JB & Belnap DM Bsoft: image processing and molecular modeling for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 157, 3–18, doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.006 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterhouse A et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 46, W296–W303, doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo X et al. Structural Basis for NusA Stabilized Transcriptional Pausing. Mol Cell 69, 816–827 e814, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.008 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettersen EF et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612, doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Afonine PV et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544, doi: 10.1107/S2059798318006551 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501, doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jumper J et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589, doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Afonine PV et al. New tools for the analysis and validation of cryo-EM maps and atomic models. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 814–840, doi: 10.1107/S2059798318009324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toulokhonov I, Zhang J, Palangat M & Landick R A central role of the RNA polymerase trigger loop in active-site rearrangement during transcriptional pausing. Mol Cell 27, 406–419, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.008 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weilbaecher R, Hebron C, Feng G & Landick R Termination-altering amino acid substitutions in the beta’ subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase identify regions involved in RNA chain elongation. Genes Dev 8, 2913–2927, doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2913 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burby PE & Simmons LA CRISPR/Cas9 Editing of the Bacillus subtilis Genome. Bio Protoc 7, doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hockett KL & Baltrus DA Use of the Soft-agar Overlay Technique to Screen for Bacterially Produced Inhibitory Compounds. J Vis Exp, doi: 10.3791/55064 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.