Abstract

Introduction

The worldwide rising number of joint replacements results in increasing revision surgery including a relevant portion of septic loosening accompanied by bone deficiencies. Loading of allogeneic bone with antibiotics provides high local antibiotic concentrations and might eradicate bacteria which appear resistant to systemic antibiotic application. Hydrophobic palmitic acid was shown to be a suitable carrier for antibiotics and prevents biofilm.

Methods

Cancellous bone derived from 6 to 7 months old piglets was used for a standardized in vitro impaction bone grafting model according to previous studies. The specimens were either thermodisinfected or remained native and palmitic acid with one third and two third partial weight were added and compared with control. Shear force at the interface prosthesis to cement and between cement and bone was measured. The relative micromovements were measured with 6 inductive sensors with a resolution of 0.1 μm at three different measuring heights up to a maximum movement of 150 μm between cement and bone. Taking into account the corresponding applied torque the measured values were normalized in μm/Nm. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS Statistics® Version 26.0 IBM.

Results

Smallest movement was measured for thermodisinfected cancellous bone and a not significant decrease of shear force resistance with addition of palmitic acid was found since supplementing native cancellous bone reduced shear force resistance significantly depending on the weight percentage of palmitic acid.

Conclusion

Supplementation of porcine cancellous bone with palmitic acid did not significantly reduce shear force resistance of thermodisinfected bone since adding palmitic acid to native bone decreased it significantly depending on the volume added. Palmitic acid seems to be a suitable coating for allogeneic cancellous bone to deliver high local antibiotic concentrations and thermodisinfected cancellous bone might be able to store larger volumes of palmitic acid than native bone without relevant influence on shear force resistance.

Keywords: Femoral impaction bone grafting, Native cancellous bone, Thermodisinfected bone antibiotic carrier, Shear force, Palmitic acid, Biofilm, Periprosthetic infection

1. Introduction

Bone defects are a relevant complication of revision surgery for infected joint replacements and the costs related to increasing number of septic revision surgery of arthroplasties are significant.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Impaction bone grafting might restore bone defects alternatively to large implants and achieve good long term results.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Revisions of joint replacements bear an increased risk of infection and local application of antibiotics is not established for cementless revisions since loading cement with antibiotics is a standard procedure in septic revision surgery.1,9,13,14,18, 19, 20 Local application of antibiotics can be provided by carrier substances with different release kinetic like PMMA cement and ceramic phosphates or allogeneic bone.1,13,18,21,22 Addition of antibiotic carrier to impacted bone graft releasing high local antibiotic concentrations seems beneficial for revision surgery of joint replacements in infectious disease especially caused by multiresistant bacteria.1,13,19,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Higher local antibiotic concentrations might eradicate bacteria being resistant against lower concentrations achieved by systemic application.13,18,19,21,22,25 The carrier substance should improve mechanic stability of bone graft and promote osseous integration.1,19,21,22,28, 29, 30, 31 The porous structure of cancellous bone provides a high loading capacity for antibiotics and palmitic acid (PA) provides an immediate release since the hydrophobic properties impede local adhesions of proteins and therefore prevent formation of biofilm.13,21,22,25,27 Supplementation of allogeneic bone with carrier particles and bone bank processing should alter mechanic properties of impacted bone.1,2,10, 11, 12,15, 16, 17,31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Bone bank procedures reduce fat and water content of cancellous bone influencing loading capacity for hydrophobic substances.7,10,29,32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Primary stability of impaction bone grafting depends on the operative technique and the quality of bone grafts.10,15, 16, 17,23,31,33,37,40, 41, 42 The set up of the impaction bone grafting model was related to previous studies.24,43

PA has not revealed any side effects regarding ISO 10993 and in its fluid phase it might cover an extensive share of the complete volume of cancellous bone without disturbing impaction behavior. 25 , 27 The completely soluble hydrophobic carrier PA has been shown to provide higher local concentrations of antibiotics than systemic application and seems beneficial to prevent biofilm formation. 21, 22, 23 , 25 , 27 The influence of different content of PA on the impaction behavior and mechanical stability should be examined to gain information on the possible loading capacity of native and thermodisinfected allogeneic bone since differences might be caused by different fat content.

2. Methods

2.1. Source and preparation of bone for in vitro femoral impaction model

The cancellous bone derived from 120 femoral heads of 6–7 months old piglets with a weight of 90 kg (LahnFleisch GmbH & Co. KG, Wetzlar, Germany) within 12 h after slaughter. Soft tissue was removed from the proximal part of the porcine femura using a scalpel following a horizontal osteotomy with an oscillating saw (Multitalent FMT 250SL, C.&E. Fein GmbH, Schwäbisch Gmünd-Bargau, Germany) between the minor and greater trochanter. One half of the cancellous bone remained native and the other half was randomized assigned to the bone bank procedure thermodisinfection.30 Immediately after preparation the porcine bone was stored at −20 °C. 42 femura derived from 18-months old cattle (LahnFleisch GmbH & Co. KG, Wetzlar, Germany) with a weight between 550 kg and 650 kg were provided within 12 h after slaughter. The bovine femura used for the impaction were also cleaned from soft tissue. The average length following proximal horizontal metaphyseal osteotomy was 34 cm and the diameter at the junction between diaphysis and proximal metaphysis was 6 cm. The bovine femora were also stored at −20 °C. Before further processing equivalent to previous studies the porcine native cancellous bone was thawed in normal saline solution 21 ± 1 °C for 3 h and the bovine femora were left in room temperature of 21 °C for 16 h.24,43

2.2. Mixture of PA with cancellous bone

After heating at 63 °C palmitic acid 98% (Distribution GmbH, Hamburg, Germany, Type 1698, Lot number: B2777 IMLIF) was added to native and thermodisinfected bone chips with a partial weight of one third and two thirds. Therefore 184.8 g PA was mixed with 560 g native cancellous bone chips after 16 h at room temperature and 391.38 g PA was added to 1186 g thermodisinfected bone chips and the procedure was comparable for 66% PA (native:1150 g plus 759 g; thermodisinfected:1020 g plus 673 g). The cancellous bone chips were doused with the fluid and mixing achieved a homogenous mixture within 30 s prior hardening of PA.

2.3. Effectiveness of Gentamicinpalmitate at room and body temperature

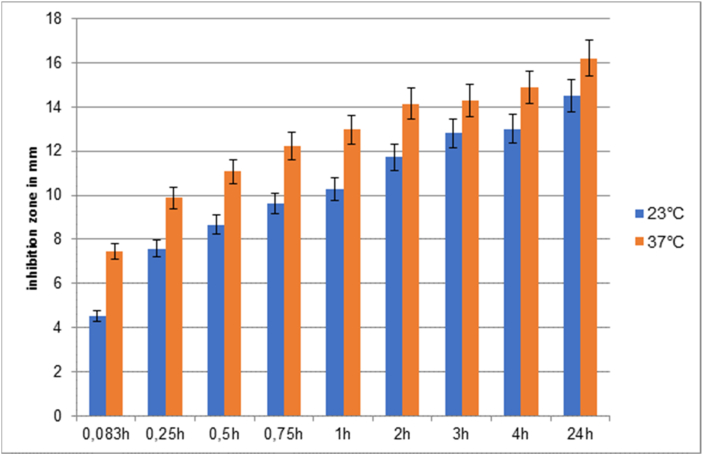

Gentamicinpalmitate (GP) is prepared by inverse salt exchange. The sulphate ions of Gentamicin sulphate are replaced by palmitic acid anions and flat discs (diameter 15.6 mm) were coated with GP (1 mg/cm2) which was employed as an alcoholic solution.25,27 The effectiveness of GP was tested by inhibition zone test at 21 °C and 37 °C (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

GP coated discs: Inhibition zones in mm of Staphylococcus aureus with incubation at 23 °C (blue column) and 37° (red column).

2.4. Femoral impaction procedure in vitro

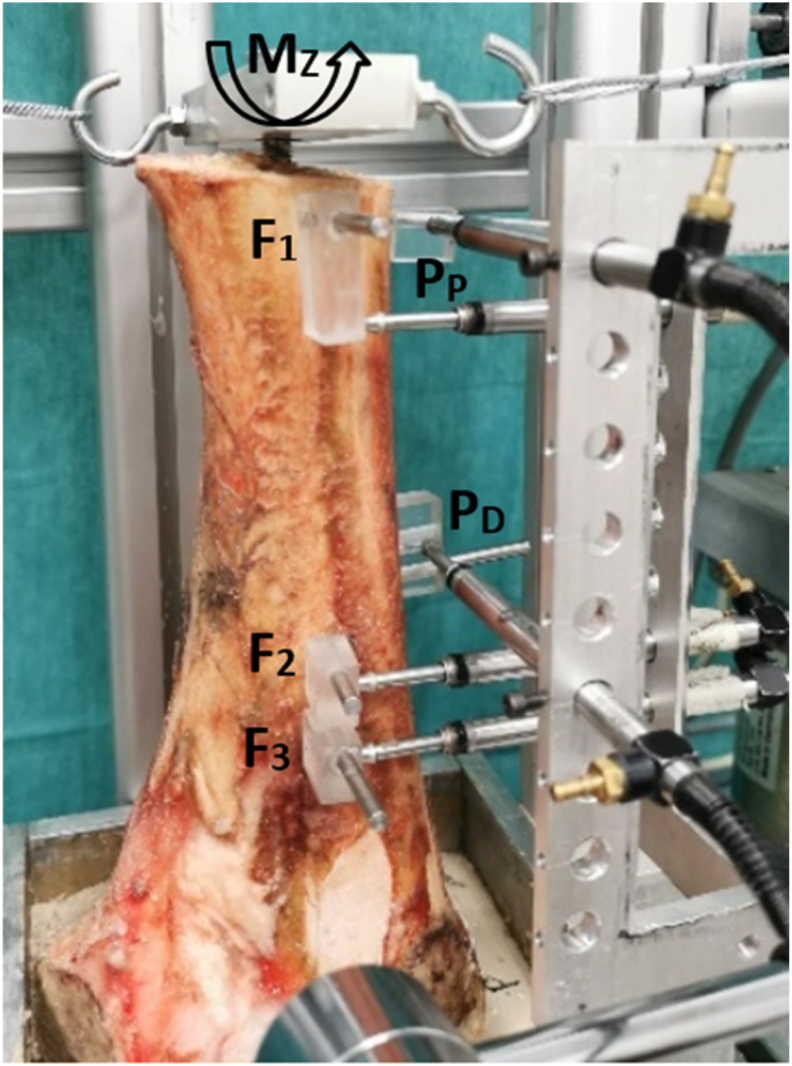

After laser controlled fixation of the femur in a mounting device the impaction of bone chips into the femur was performed according to previous studies (Fig. 2).24,43

Fig. 2.

Left: Cancellous bone chips filled medullary cavity of femur before impaction; Right: After impaction of bone chips coated with 33% partial weigth of palmitic acid.

2.5. Cementation

Cementation was done with Palacos® R and Palamix® vacuum mixing technique of 200 mbar within 30 s (Heraeus Medical GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) according to recommendations of the manufacturer. The implant imitating a femoral shaft was constructed with a length of 125 mm, a distal diameter of 11 mm and a proximal diameter of 13.9 mm. It was cleaned with 70% 2-propanolol and guide wire controlled fixation to the impactor provided a reproducible vertical and centralized penetration of the endoprosthesis into the cement. Continous pressure was applied until the implant reached the proximal edge of the femur.

2.6. Measurement of torsional micromovement

Points of measurement for micromovement were chosen according to a previous study.43 The models were measured after 16 h of thawing. Two measurement points PP and PD were located at the prostheses and three points F1–F3 at the femur. For fixation of the measurement pins at the prosthesis first the cortical bone was drilled with an 8 mm drill followed by a 2 mm drill into the cement mantle. The corresponding femur points were drilled with a1.9 mm drill. After cleaning of the drill holes the pins were fixed with cyanacrylat (Klebfix, Adolf Würth GmbH & Co. KG, Künzelsau, Germany). The procedure of fixation was similar for the cortical bone of the femur. Stability of the pins was tested 5 min after application of the glue.

Cycling torsional torques (MZ) were applied and relative micromovements between bone and prosthesis-cement compound were recorded.44 The relative movements were measured simultanously by six orthoganally to the measurement pins aligned inductive sensors with a resolution of 0.1 μm each (P2010, Mahr GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) at three different measuring heights up to a maximum movement of 150 μm between prosthesis-cement compound and bone. Taking into account the corresponding maximum applied torque the measured values were then normalized in μm/Nm. The relative micromovement at the measurement point rm1 and rm2 resulted from the difference between these movements. With these normalized relative movements a maximum torsional load in Nm can be approximated using simple division of the maximum interfacial motion of 150 μm and the recorded relative micromovements (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Measurement of relative micromovement of femur specimens with defined corresponding points.44

2.7. Statistical analysis

Seven specimens of each native and processed bone group were calculated based on a previous study.43 Statistical analysis was done with SPSS (Version 28, SPSS Inc. Chicago IL). A generalized linear model (GLM) and the LSD Post-Hoc-Test for pairwise comparison were employed. Due to multiple testing a Bonferroni adjustment was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Impaction procedure

The number of impactions was different between the native bone and the mixture with 33% and 66% partial weight of PA and revealed an increase with higher weight percentage of PA (Table 1). Impaction of thermodisinfected bone also showed increasing number of impactions related to higher partial weight of PA since the number of impactions appeared les s compared with the native bone (Table 1). The impaction of pure thermodisinfected bone revealed the lowest number of impaction on average since the maximum number of impactions was measured for native cancellous bone mixed with 33% partial weight of PA.

Table 1.

Overview of the number of impaction strokes of the test series.

| Group | native | thermo | 33% native | 33% thermo | 66% native | 66% thermo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strokes/Mean | 36.7 | 40.1 | 64.4 | 19.1 | 30.0 | 37.7 |

| SD | 11.5 | 11.0 | 19.4 | 7.9 | 18.3 | 13.6 |

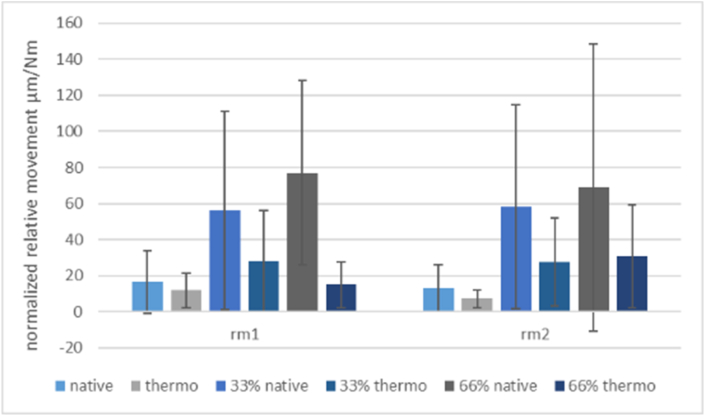

3.2. Relative micromovement of the implant at different sites

The smallest relative micromovement was measured for thermodisinfected cancellous bone without PA at the distal point of measurement since no significant difference between native and thermodisinfected bone was found (Table 2, Table 3).

Table 2.

Relative micromotion (μm/Nm) as mean values with corresponding standard deviation (SD) at the matching measurement heights rm1 (proximal) and rm2 (distal) and taking into account the respective treatment and addition of PA. Small superscript letters indicate significant differences compared in pairs.

| Group | native | thermo | 33% native | 33% thermo | 66% native | 66% thermo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rm1 max Load [Nm] | 9.1 | 12.6 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 10.0 |

| rm2 max Load [Nm] | 11.5 | 20.5 | 2.6 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 4.9 |

Table 3.

Approximated maximum torsional load (Nm) taking into account a maximum interface movement of 150 μm between prosthesis-cement compound and bone for all groups.

| Group | native | thermo | 33% native | 33% thermo | 66% native | 66% thermo | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rm1 | 16.50 | 11.90 | 56.20 | 28.04 | 77.06 | 14.96 | a = 0.022 |

| [μm/Nm] | ±17.57a | ±9.49 | ±55.02 | ±27.88 | ±50.95a,b | ±12.74b | b = 0.011 |

| rm2 | 13.09 | 7.32 | 58.10 | 27.47 | 69.09 | 30.87 | a = 0.029 |

| [μm/Nm] | ±12.85a | ±4.90 | ±56.61 | ±24.41 | ±79.59a | ±28.55 |

More movement at the proximal point of measurement was shown for most specimens. Adding PA to thermodisinfected bone increased the movement distally more than proximally and this effect was pronounced for native bone. Adding 66% partial weight PA to thermodisinfected bone did not significantly increase the movement at the distal point since the relative movement decreased proximal. The increase of the movement was higher for native bone and significant difference appeared between native and thermodisinfected bone proximal after adding 66% PA (Table 2, Table 3). The two points o f measurement at the implant did not show any significant change correlated with different contents of PA except for native bone compared with its loading of 66% percentage weight PA for proximal and distal point of measurement regarding comparison in pairs (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Representation of the relative micromovements at the measurement point locations (rm1 = proximal; rm2 = distal) considering the individual groups.

Fig. 5.

Representation of the relative micromovements of the individual groups considering the measuring point (rm1 = proximal; rm2 = distal).

3.3. Influence of PA on rotational stability

The relative micromovement of native bone increased with partial weight of 33% PA and this appeared significant with 66% weight percentage of native bone (Table 2). No significant difference was found between thermodisinfected and native cancellous bone regarding relative micromovement (Table 3). The addition of PA showed an overall significant effect on all specimens (p = 0.002) related to increase of relative micromovement. The average micromovement of all specimens containing 33% PA was not significantly increased for the native and the thermodisinfected cancellous bone. No further increase of the micromovement was shown for addition of 66% volume of PA to thermodisinfected bone since a significant increase was found for native bone (Table 2, Table 3). The maximum load of thermodisinfected bone appeared less effected by addition of PA since the values were around double of native cancellous bone (Table 2, Table 3).

3.4. Inhibition zone tests

The release of gentamicin from GP during 24 h is increased at body temperature (37 °C) compared with room temperature (23 °C). The antimicrobial inhibitory effect against Staphylococcus aureus at body temperature is enhanced within the first 5 min after application since 39.2% more gentamicin was released and that difference decreased to 10.4% after 24 h (Fig. 1).

3.5. Mechanic behavior of native versus thermodisinfected cancellous bone

More impaction impulses were necessary for the native cancellous bone and a further increase of this number was related to increasing content of PA for native and thermodisinfected bone. Most impulses (n = 64) were necessary for native bone mixed with 66% PA since the number measured (n = 37) for the mixture with thermodisinfected bone and the smallest number was found for thermodisinfected cancellous bone (n = 19) combined without PA. The thermodisinfected cancellous bone showed a smaller relative micromovement than native bone both without addition of PA since difference between both types of bones was reduced with combination of PA. Micromotion was found smaller for native and thermodisinfected bone at the tip of the endoprosthesis than at the proximal point. Overall impacted thermodisinfected could achieve more shear force resistance than native bone since the difference was not significant (Table 3).

4. Discussion

Local applications of antibiotics might avoid systemic side effects and achieve higher local concentrations of antibiotics since bacteria resistant to systemic therapy might be sensitive to many times higher local antibiotic concentrations and systemic application does not seem to improve outcome.3,13,19,21,22,45,46 Prevention of biofilm is important to reduce the risk of infection of arthroplasties and coating with PA might be a suitable carrier for antibiotics.13,19,21,22,25,46 PA is biocompatible according to ISO 10933 and releases gentamicin before formation of biofilm since antibiotic activity will last several weeks and hydrophobic PA attached to allogeneic bone seems appropriate to prevent biofilm formation itself.13,19,21,22,25,27 No relevant alteration of the state of aggregation should be assumed at 37 °C compared with tests performed at room temperature (Fig. 1).25,27

Antibiotic loading of the allogeneic bone seems favorable for biologic reconstruction of bone defects in septic revisions of arthroplasties.13,18, 19, 20, 21, 22,25 Fresh autogenous bone remains the gold standard since native allogeneic bone grafts bears a higher risk of infection transfer than thermodisinfected bone.11,12,15,30 Several carrier substances might be considered which provide different release kinetics of antibiotics and according to exothermic reaction of PMMA cement some antibiotics are being inactivated.13,18,23,24,26,27 Ceramic calcium phosphates and allogeneic bone transplants might achieve incorporation into the host bone since PMMA cement should be surrounded by fibrous tissue.1,22,24,26,28,41 Adding hydroxyapatite to allograft bone revealed different influence on mechanic stability.11,41,47,48 Acetabular cup translation was reduced with increasing content of ceramic phosphate particles and cement penetration was influenced by hydroxyapatite supplementation.47 Different clinical results of femoral impaction bone grafting regarding mixture of allograft bone with ceramic phosphates were reported.11,41,47,48 Ceramic particles showed a different deformation behavior with almost no viscoelastic behavior since allogeneic bone contains a physiologic collagen structure.36 Therefore application of allogeneic bone might be beneficial.

Different number of impaction strokes for native and thermodisinfected cancellous had been shown in previous studies since a significant correlation with mechanic properties did not appear (Table 1).24,48 Different degrees of impaction for processed bone including higher impaction than for native bone were described and no significant mechanic difference between native and processed bone was shown.25,36, 37, 38 We found reduced number of impactions for thermodisinfected bone since adding of PA revealed a minimal increase. That effect was pronounced for native bone since no significant differences between both groups were found. Adding ceramic phosphate particles to native and thermodisinfected bone had shown a comparable effect indicating different impaction behavior of native and thermodisinfected bone.24,28,43 This study showed no significant difference of shear force resistance between pure native and thermodisinfected cancellous bone comparable with previous studies.24,28 Increased stiffness and compactness was found for processed compared with native cancellous bone.33,34,37,49 Further reduction of height of processed cancellous bone correlated with improvement of mechanic properties including an increase of rotational stiffness since mechanic properties of thermodisinfected cancellous bone were found slightly reduced.32, 33, 34,37,49 According to previous studies shear force resistance remained higher at the distal point of measurement after adding PA indicating the reproducibility of the in vitro model (Fig. 5).24,28,43

Different results regarding the influence of water and fat content on the impaction and on shear force resistance of cancellous bone have been reported since the size of the bone chips had an influence on the impaction behavior.29, 30, 31,35,36,50 Thermodisinfection should influence mechanic behavior by reduction of fat since the ideal content of fat for impaction is not known.24,29,50 A small and not significant reduction of shear force resistance after loading thermodisinfected bone with PA was measured since presence of fat has been found necessary for improvement of impaction regarding adhesion behavior (Table 2).50 This should be related to the bone bank procedure thermodisinfection which removes fat from the allogeinic bone. Deviating loading native bone with PA revealed increased relative micromovement which appeared significant with two thirds partial weight. An increasing content of PA revealed a more pronounced negative influence on shear stress resistance of native cancellous bone compared with thermodisinfected bone. PA also seems to affect adhesion of particles during impaction. Adhesions properties might influence distribution of cement and affect adherence of proteins.25,27,28,49 Therefore hydrophob properties of PA might be useful to prevent formation of biofilm on implants independently from the antibiotic release.25,27

It can be assumed that addition of PA of at least 33% partial weigth of cancellous bone should decrease shear stress resistance. According to the small number of specimens this does not appear significant. A dose dependent influence on shear force resistance can be assumed which reaches a significant level for native bone supplemented with two third partial weight of PA indicating a different storage capacity for hydrophob substances compared with thermodisinfected bone. Thermodisinfected bone seems to provide more loading capacity for PA than native bone until relevant impairment of shear force resistance appears since thermodisinfected bone contains less fat as a result of the specific bone bank procedure (Table 2, Table 3).24,28,30 Higher shear force resistance of thermodisinfected compared with native bone should indicate the relevance of reduction of fat from the bone graft.50 Supplementing less than 30% PA partial weight seems feasible since that should be sufficient to provide necessary concentration of antibiotics.13,19,21,22,25,27

Thermodisinfected cancellous bone should provide more loading capacity for a hydrophob carrier substance for antibiotics since supplementing with different partial weight of PA showed less decrease of shear force resistance compared with native cancellous porcine bone. No significant reduction of shear force resistance was found for thermodisinfected bone since a gradual decrease was measured with more addition of PA. The impairment of shear force resistance after addition of PA appeared pronounced for native bone. A different impaction behavior of native and processed cancellous bone was shown since shear force resistance of impacted thermodisinfected bone appeared higher than for native bone.24,28,33,34,37 Therefore the influence of supplemented material on shear force resistance can be expected differently.24,43,50 The ideal volume of PA to be added to allogeneic bone without relevant disturbance of mechanic properties needs further examination and should be expected below 30% partial weight since a not significant reduction of shear force resistance could be shown. A higher partial weight loading of PA might be suitable if the release of the antibiotic appears more important than mechanic stability of the impacted bone depending on the bone defect.

Thermodisinfected cancellous bone seems preferable as a carrier of local application of antibiotics regarding a hydrophob substance. In vivo studies should be necessary to evaluate the antibiotic activity against different numbers from various bacteria and the osseous integration of the allogeneic bone graft. Adding one third partial weight PA revealed less reduction of shear force resistance for thermodisinfected than for native bone since the absolute value of reduction was evident for both bone grafts. Therefore the ideal volume for addition of PA for antibiotic therapy without relevant impairment of mechanic properties needs further examinations and should be less than 30% weigth percentage. The localization of transplantation needs to be considered since the requirements for mechanic properties might be different. Bone infections independent of arthroplasties should be treated similar and in those cases mechanic properties of bone graft might be less important. Coating of the implants with PA containing antibiotics might be another option to prevent or reduce risk of infection.

4.1. 4.1. Limitations

The current study is based on a limited number of specimens since heterogeneity of bone material is reflected by considerable standard deviations affecting significance level. A significant decrease of shear force resistance related to mixture of cancellous bone and PA might be expected with more specimens. The correlation of the precise volume of supplemented PA and mechanic parameter was not feasible. The exact volume of PA providing the necessary antibiotic capacity without relevant impairment of mechanic properties needs further investigation and more specimens should provide significant results since three dimensional computertomographic analysis for distribution of PA and bone graft seems useful. The different state of aggregation of PA during impaction at body temperature has to be considered.

5. Conclusion

Palmitic acid seems to be a suitable carrier substance for antibiotics since no significant decrease of shear force resistance was shown after loading of thermodisinfected impacted porcine cancellous bone. A pronounced dose dependent reduction of shear force resistance was shown for supplementing native bone with PA since no difference was found between native and thermodisinfected bone. Higher shear stress resistance at the distal compared with the proximal point of measurement remained in presence of PA for native and processed bone. High initial release of gentamicin from PA and effectiveness of antibacterial treatment have been shown and further studies should define the necessary volume of PA for a most effective antibiotic treatment without disturbance of mechanic properties of impacted bone. According to the bone bank procedure thermodisinfected bone should provide more loading capacity for a hydrophob carrier substance for antibiotics than native cancellous bone without significant reduction of shear force resistance. The volume of supplemented PA might be adjusted to the desired mechanic properties of the bone graft.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-profit sectors.

Authors contribution

Christian Fölsch: Conceptualization, Methodology, Original draft preparation, Reviewing, Writing original draft and Editing. Sebastian Preu: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal analysis. Carlos Alfonso Fonseca Ulloa: Software, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation. Klaus Dieter Kühn: Writing and Review. Markus Rickert: Project administration, Review. Alexander Jahnke: Methodology, Supervision, Review, Project administration, Validation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data measured and calculated in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr. K.D. Kühn for providing Palamix® and Palacos® R + G 40.

References

- 1.Aulakh T.S., Jayasekera N., Kuiper J.H., Richardson J.B. Long-term clinical outcomes following the use of synthetic hydroxyapatite and bone graft in impaction in revision hip arthroplasty. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1732–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colo E., Rijnen W.H., Schreurs B.W. The biological approach in acetabular revision surgery: impaction bone grafting and a cemented cup. Hip Int. 2015;25(4):361–367. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frommelt L. Use of antibiotics in bones: prophylaxis and current treatment standards. Orthopä. 2018;47(1):24–29. doi: 10.1007/s00132-017-3508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Rey E., Saldana L., Garcia-Cimbrelo E. Impaction bone grafting in hip re-revision surgery. Bone Joint Lett J. 2021;103-B(3):492–499. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B3.BJJ-2020-1228.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okafor C., Hodgkinson B., Nghiem S., Vertullo C., Byrnes J. Cost of septic and aseptic revision total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. 2021;22:706. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quayle J., Barakat A., Klasan A., et al. Management of peri-prosthetic joint infection and severe bone loss after total hip arthroplasty using long-stemmed cemented custom-made articulating spacer (CUMARS) BMC Musculoskelet. 2021;22(1):358. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudert M., Holzapfel B.M., von Rottkay E., Holzapfel D.E., Noeth U. Impaction bone grafting for the reconstruction of large bone defects in revision knee arthroplasty. Oper OrthopTraumatol. 2015;27:35–46. doi: 10.1007/s00064-014-0330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Windhager R., Hobusch G.M., Matzner M. Allogeneic transplants for biologic reconstruction of bone defects. Orthopä. 2017;46(8):656–664. doi: 10.1007/s00132-017-3452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaiyakit P., Meknavin S., Hongku N., Onklin I. Debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention combined with direct intraarticular antibiotic infusion in patients with acute hematogenous periprosthetic joint infection of the knee. BMC Musculoskelet. 2021;22(1):557–563. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04451-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gie G.A., Linder L., Ling R.S., Simon J.P., Slooff T.J., Timperley A.J. Impacted cancellous allografts and cement for revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75-B:14–21. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B1.8421012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliday B.R., English H.W., Timperley A.J., Gie G.A., Ling R.S. Femoral impaction grafting with cement in revision total hip replacement: evolution of the technique and results. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-B:809–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howie D.W., Callary S.A., McGee M.A., Russell N.C., Solomon L.B. Reduced femoral component subsidence with improved impaction grafting at revision hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(12):3314–3321. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1484-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kittinger C., Marth E., Windhager R., et al. Antimicrobial activity of gentamicin palmitate against high concentrations of Staphylococcus aureus. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22(6):1447–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei P.F., Hu R.Y., Hu Y.H. Bone defects in revision total knee arthroplasty and management. Orthop Surg. 2019;11(1):15–24. doi: 10.1111/os.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slooff T.J., Huiskes R., van Horn J., Lemmens A.J. Bone grafting in total hip replacement for acetabular protrusion. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:593–596. doi: 10.3109/17453678408992402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waddell B.S., Della Valle A.G. Reconstruction of non-contained acetabular defects with impaction grafting, a reinforcement mesh and a cemented polyethylene acetabular component. Bone Joint Lett J. 2017;99-B(1 Supple A):25–30. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0322.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson M.J., Hook S., Whitehouse S.L., Timperley A.J., Gie G.A. Femoral impaction bone grafting in revision hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint Lett J. 2016;98-B(12):1611–1619. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B12.37414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bormann N., Schwabe P., Smith M.D., Wildemann B. Analysis of parameters influencing the release of antibiotics mixed with bone grafting material using reliable mixing procedure. Bone. 2014;59:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coraca-Huber D.C., Ammann C.G., Nogler M., et al. Lyophilized allogeneic bone tissue as an antibiotic carrier. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016;17:629–642. doi: 10.1007/s10561-016-9582-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leta T., Lygre S., Schrama J., et al. Outcome of revision surgery for infection after total knee arthroplasty. Results of 3 surgical strategies. JBJS Reviews. 2019;7(6):e4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fölsch C., Federmann M., Kühn K.D., et al. Coating with a novel gentamicinpalmitate formulation prevents implant-associated ostemyelitis induced by methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Int Orthop. 2015;39:981–988. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fölsch C., Federmann M., Lakemeier S., et al. Systemic antibiotic therapy does not significantly improve outcome in a rat model of implant associated osteomyelitis induced by Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(4):585–592. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornu O., Schubert t, Libouton X., et al. Particle size influence in an impaction bone grafting model. Comparison of fresh-frozen and freeze dried allografts. J Biomech. 2009;42:2238–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fölsch C., Jahnke A., Gross A., et al. Influence of thermodisinfection on impaction of cancellous bone. An in vitro model of femoral impaction bone grafting. Orthopä. 2018;47(1):39–51. doi: 10.1007/s00132-017-3509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kühn K.D., Brünke J. Effectiveness of novel gentamycinpalmitate coating on biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Int J Nano Biomaterials (IJNBM) 2010;3(1):107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis C.S., Supronowicz P.R., Zhukauskas R.M., Gill E., Cobb R.R. Local antibiotic delivery with demineralized bone matrix. Cell Tissue Bank. 2012;13(1):119–127. doi: 10.1007/s10561-010-9236-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogt S., Kühn K.D., Gopp U., Schnabelrauch M. Resorbable antibiotic coatings for bone substitutes and implantable devices. Mater Sci Eng Tech. 2005;36(12):814–819. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fölsch C., Kellotat A., Rickert M., et al. Effect of thermodisinfection on mechanic parameters of cancellous bone. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016;17(3):427–437. doi: 10.1007/s10561-016-9567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fosse L., Ronningen H., Benum R., Sanven R.B. Influence of water and fat content on compressive stiffness properties of impacted morsellized bone. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:15–22. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruss A., Seibold M., Benedix F., et al. Validation of the ‘‘Marburg bone bank system’’for thermodisinfection of allogeneic femoral head transplants using selected bacteria, fungi and spores. Biologicals. 2003;31 doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2003.08.002. 287–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Putzer D., Coraca-Huber D., Wurm A., Schmoelz W., Nogler M. The mechanical stability of allografts after. cleaning process: comparison of two preparation methods. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1642–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bankes M.J.K., Allen P.W., Aldam C.H. Results of impaction grafting in revision hip arthroplasty at two to seven years using fresh and irradiated allograft bone. Hip Int. 2003;13:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornu O., Boquet J., Nonclerq O. Synergetic effect of freeze-drying and gamma irradiation on the mechanical properties of human cancellous bone. Cell Tissue Bank. 2011;12(4):281–288. doi: 10.1007/s10561-010-9209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornu O., Libouton X., Naets B., et al. Freeze-dried irradiated bone brittleness improves compactness in an impaction bone grafting model. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(3):309–314. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunlop D.G., Brewster N.T., Madabhushi S.P.G., Usmani A.S., Pankaj P., Howie C.R. Techniques to improve the shear strength of impacted bone graft. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;B-85(4):639–646. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fosse L., Muller S., Ronningen H., Irgens F., Benum P. Viscoelastic modeling of impacted morsellised bone accurately describes unloading behaviour: an experimental study of stiffness moduli and recoil properties. J Biomech. 2006;39:2295–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fosse L., Ronningen H., Benum P., Lydersen S., Sandven R.B. Factors affecting stiffness properties in impacted morsellized bone used in revision hip surgery: an experimental in vitro study. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2006;78:423–431. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujishiro T., Nishikawa T., Niikura T., et al. Impaction bone grafting with hydroxyapatite: increased femoral component stability in experiments using Sawbones. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:550–554. doi: 10.1080/17453670510041556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munro N.A., Downing M.R., Meakin J.R., Lee A.J., Ashcroft G.P. A hydroxyapatite graft substitute reduces subsidence in a femoral impaction grafting model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:246–252. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238828.65434.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putzer D., Mayr E., Haid C., Reinthaler A., Nogler M. Impaction bone grafting. A laboratory comparison of two methods. J Bone Joint Surg. 2011;93-B(8):1049–1053. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.26819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Haaren E.H., Smit T.H., Phipps K., Wuisman P.I.J.M., Blunn G., Heyligers I.C. Tricalcium-phosphate and hydroxapatite bone-graft extender for use in impaction grafting revision surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87-B:267–271. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b2.14749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gittings D.J., Dattilo J.R., Hardaker W., Sheth N.P. Evaluation and treatment of femoral osteolysis following total hip arthroplasty. JBJS Reviews. 2017;5(8):e9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.16.00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fölsch C., Sahm P., Fonseca Ulloa C.A., et al. Effect of synthetic bone replacement material of different size on shear stress resistance within impacted native and thermodisinfected cancellous bone: an in vitro femoral impaction bone grafting model. Cell Tissue Bank. 2021;22(4):651–664. doi: 10.1007/s10561-021-09924-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jahnke A., Ghandourah S., Fonseca Ulloah C.A., et al. Comparison of short stems vs straight hip stems: a biomechanical analysis of the primary torsional stability. J Biomech Eng. 2020 doi: 10.1115/1.4047659. ; doi 10(1115/1): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Overstreet D., McLaren A., Calara F., Vernon B., McLemore R. Local gentamicin delivery from resorbable viscous hydrogels is therapeutically effective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3935-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudelli B.A., Giglio P.N., de Carvalho V.C., et al. Bacteria drug resistance profile affects knee and hip periprosthetic joint infection outcome with debridement, antibiotics and implant revision. BMC Musculoskelet. 2020;21:574–579. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolder S.B.T., Verdonschot N., Schreurs B.W., Buma P. The initial stability of cemented acetabular cups can be augmented by mixing morsellized bone grafts wit tricalciumphosphate/hydroxyapatite particles in bone impaction grafting. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):1056–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verdonshot N., van Hal C.T., Schreurs B.W., Buma P., Huiskes R., Slooff T.J. Time-dependent mechanical properties of HA/TCP particles in relation to morsellized bone grafts for use in impaction grafting. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58(5):599–604. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oakley J., Kuiper J.H. Factors affecting the cohesion of impaction bone graft. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88-B:828–831. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B6.17278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKenna P.B., Leahy J.J., Masterson E.L., McGloughlin T.M. Optimizing the fat and water content of impaction bone allograft. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(2):243–248. doi: 10.1002/jor.22213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data measured and calculated in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.