Abstract

Paid caregivers (e.g., home health aides, home care workers) provide essential care to people with dementia living at home; this study explored family caregiver perspectives on the role and impact of paid caregivers in home-based dementia care. We conducted semi-structured interviews with family caregivers (n=15) of people with advanced dementia who received long-term paid care at home in New York between October 2020 and December 2020. We found that given the vulnerability resulting from advanced dementia, family caregivers prioritized finding the “right” paid caregivers and valued continuity in the individual providing care. The stable paid care that resulted improved outcomes for both the person with advanced dementia (e.g., eating better) and their family (e.g., ability to work). Those advocating for high quality, person-centered dementia care should partner with policymakers and home care agencies to promote the stability of well-matched paid caregivers for people with advanced dementia living at home.

Background

Many people with dementia wish to remain living in their homes, rather than move to an institution, even as cognition and function worsen (“2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures,” 2021; Harrison et al., 2019; Samus et al., 2018). While family caregivers provide the bulk of care required for people with dementia to remain safely at home, in the United States half of people with advanced dementia living at home also receive long-term support from paid caregivers like home health aides or personal care attendants (Reckrey et al., 2020). When present, paid caregivers deliver about 40% of the total care hours received (i.e., on average 50 hours of paid care and 68 hours of family care per week) (Reckrey et al., 2020). Consequently, paid and family caregivers work together within the larger health care and long-term care systems to support the home-based care of people with dementia living at home (Reckrey et al., 2021; Reckrey et al., 2020).

While research examines the paid caregiving workforce in general (Spetz et al., 2019; Stone et al., 2013), paid caregivers are rarely studied in relation to the individuals they care for or the families with whom they share care. The role of paid care in the unique setting of home-based dementia care is underexplored. This may be due in part to the fragmentation of paid care delivery in the United States, which makes systematic study of the impact of paid care challenging. Long-term paid care is funded by a patchwork of payers (e.g., Medicaid, long-term care insurance, private pay by people with dementia and/or their families) and access to this care often depends not only on care needs, but also on state Medicaid policies, financial resources, and local availability of workers (Kaye, 2014; Kaye et al., 2010). Furthermore, paid caregivers themselves often earn poverty-level wages, which contribute to high levels of job turnover and workforce instability (Spetz et al., 2019).

Yet evidence suggests that paid caregivers support not only the function, but also the physical and mental health of those they care for (Franzosa et al., 2019; Reckrey, Tsui, et al., 2019; Sterling et al., 2018). Given the high care needs of people with advanced dementia, the impact of paid care on this group is likely significant and additional information about paid caregivers’ roles is essential in order to guide person-centered dementia care plans. Furthermore, family caregivers frequently express the need for additional assistance (e.g., respite care) as they take on the challenging task of caring for family members with dementia (Kasper et al., 2015; Strommen et al., 2020) and paid caregivers may be an important source of support to families (Reckrey et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic revealed how paid care is essential for some of the most vulnerable older adults in the United States and provides an important context in which to understand how paid caregivers contribute to overall care (Reckrey, 2020; Savla et al., 2021).

In order to maximize the potentially positive impact of paid caregivers in home-based dementia care, it is important to identify what contributes to high quality care from the perspective of those experiencing and managing this care (Reckrey et al., 2022). In this study, we interviewed family caregivers of people with advanced dementia living at home in order to understand their perspectives about the role of paid caregivers in home-based dementia care and the impact of that care on people with advanced dementia and their families.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted qualitative interviews with family caregivers of people with advanced dementia living at home between October 2020 and December 2020.

Setting and Participants

Family caregivers were recruited via the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors program, a large home-based primary care program that cares for homebound individuals in New York City (Ornstein et al., 2011). Physicians were asked to identify 5–10 of their patients who had: 1) moderate or severe dementia defined as 2 or 3 on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (Hughes et al., 1982), 2) a primary family caregiver age 18 or older who spoke either English or Spanish, and 3) a paid caregiver defined as a paid (non-family) individual providing ongoing care at home. We then used a random number generator to identify which individuals from this pool to approach. With permission from their primary care physician, we sent two letters to the person with advanced dementia’s primary family caregiver that introduced the study and gave the family caregiver the option to opt out. We then called the primary family caregiver about an interview. All study protocols were approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board and participants provided verbal informed consent prior to the interviews.

Data Collection

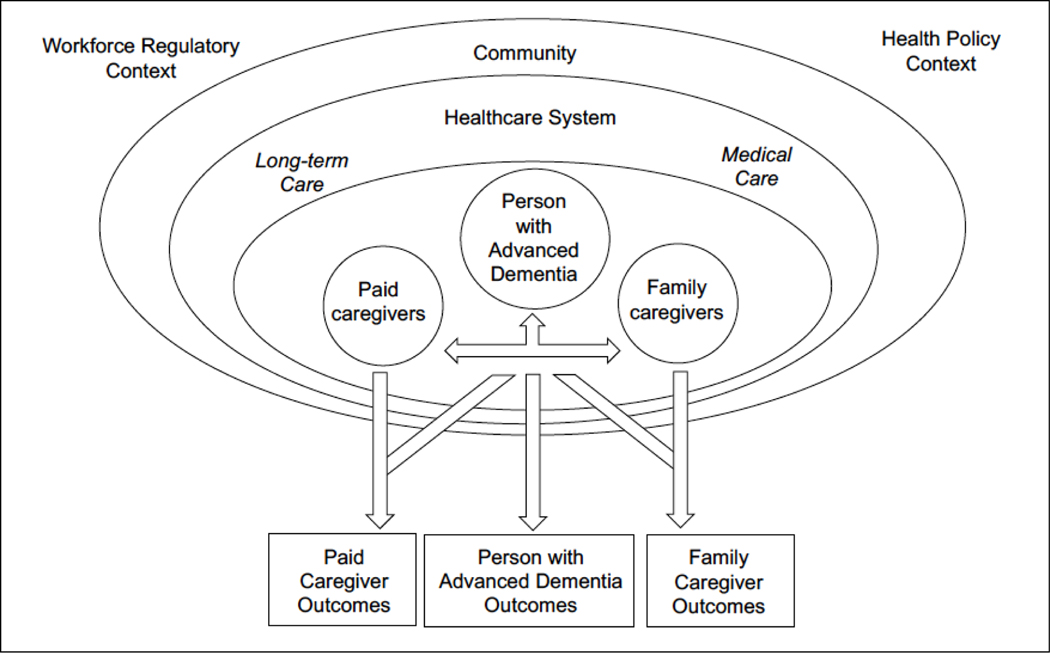

The interdisciplinary research team had expertise in paid caregiving (JR, DR, EF), family caregiving (JR, KO), dementia (JR, KO), and home-based care (JR, DR, EF). Our approach was based on our established conceptual framework (Figure 1) of the role of paid caregivers in the home-based dementia care team. Paid and family caregivers work together as a team to care for a person with advanced dementia within a larger healthcare system, community, regulatory, and policy context; the function of that team impacts not only the person with advanced dementia, but also their paid and family caregivers (Franzosa & Tsui, 2021; Kemp et al., 2013; Reckrey et al., 2021). Drawing from this conceptual framework and a thorough review of the literature, the team developed an interview guide (Appendix 1) that specifically explored the role and impact of paid care. We began by asking about sociodemographic, functional, and caregiving characteristics for both the person with dementia and the family caregiver. Because interviews occurred at a time of significant local COVID transmission, family caregivers were first asked to describe changes to their family member’s paid care during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were then asked to reflect on paid caregiving more generally, with specific questions about the impact of paid care on both the person with dementia and on family caregivers. The interview guide was piloted for content and clarity with a family caregiver not enrolled in the study, and was refined following the first several interviews.

Figure 1: Collaboration Within the Home-Based Dementia Care Team Influences Outcomes for People with Advanced Dementia and Their Paid and Family Caregivers*.

*Adapted from Reckrey et al (2021). Paid Caregivers in the Community-Based Dementia Care Team: Do Family Caregivers Benefit? Clinical Therapeutics.

Interviews were conducted by either JR (English) and SP (English and Spanish) via telephone or via HIPAA-compliant Zoom depending on the participant’s preference. Interviewers completed an exit memo capturing emerging themes after each interview. Interviews lasted on average 43 minutes (range 28 minutes to 80 minutes) and were recorded and professionally translated and/or transcribed immediately following each interview. All transcripts were reviewed by JR and SP as they became available and interviews were continued until additional interviews yielded minimal significant new information related to the research questions.

Analysis

Data were analyzed in an iterative process using thematic analysis with a combined inductive and deductive approach (Nowell et al., 2017) that drew from our conceptual framework (Figure 1). Members of the research team (JR, SP, and DW) independently reviewed several interview transcripts along with the exit memos and created a preliminary coding scheme that included both a priori codes based on the central questions in our interview guide and emergent codes derived from the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Ritchie et al., 2014). The codebook was revised as codes were applied to the interviews. Two members of the research team (JR and DW) independently applied the final coding framework to the transcripts uploaded in Dedoose qualitative software; discordance in coding was discussed until consensus was achieved (Lincoln & Guba, 1986). The team then met to review coded data, review exit memos, and explore themes and how they were interrelated.

Results

We interviewed 15 family caregivers of people with advanced dementia living at home; 6 family caregivers who were approached for interviews declined to participate with most citing a lack of time. People with dementia were on average nearly 90 years old and the majority were female (87%), Hispanic or Latino/a (67%), and had had Medicaid-funded home care with paid caregivers who worked through an agency (87%). Only two individuals paid privately for care. 73% of people with advanced dementia received 24–7, live-in paid care. The remaining 4 received between 10–12 hours of paid care daily. On average, people with advanced dementia were cared for by 3 paid caregivers (range 1–6). Family caregivers were on average 60 years old and the majority were female (87%), Hispanic or Latino/a (60%), and the children of the person with advanced dementia (60%). While only 1/3 lived with the person with advanced dementia and 60% worked outside the home for pay, nearly all (87%) had been providing care for more than 5 years (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of People with Advanced Dementia and their Family Caregivers

| People with Advanced Dementia (n=15) | |

| Age, mean (range) | 89 (76–104) |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (87%) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a, n (%) | 10 (67%) |

| Medicaid, n (%) | 13 (87%) |

| Years since first dementia diagnosis, mean (range) | 8.3 (3–20) |

| Dependent in all ADLs, n (%) | 13 (87%) |

| 24/7 Paid Care, n (%) | 11 (73%) |

| Number of paid caregivers, mean (range) | 3 (1–6) |

| Family Caregivers (n=15) | |

| Age, mean (range) | 61 (37–76) |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (87%) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a, n (%) | 9 (60%) |

| Child of Person with Dementia, n (%) | 9 (60%) |

| Providing care for 5+ years, n (%) | 13 (87%) |

| Lives with Patient, n (%) | 5 (33%) |

| Works Outside the home for Pay, n (%) | 9 (60%) |

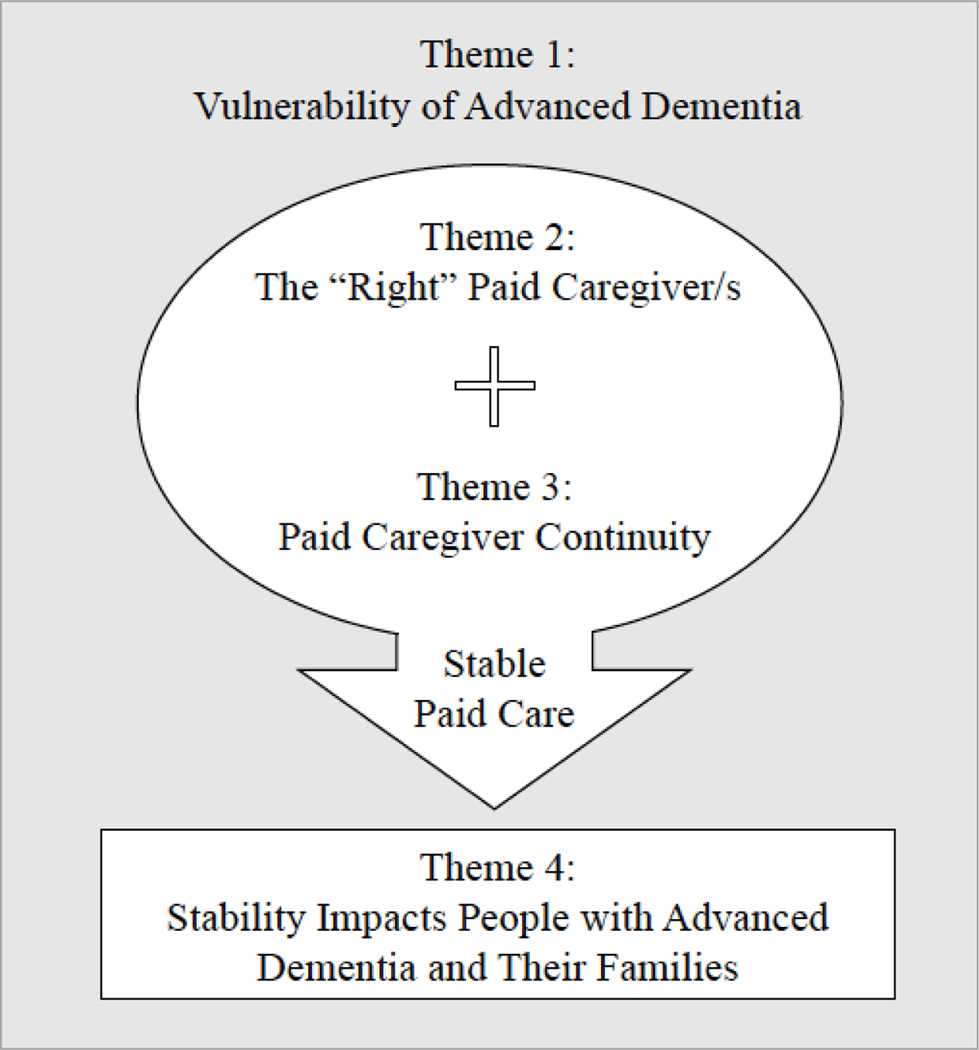

We identified 4 major themes about the role and impact of paid caregivers in home-based dementia care. These themes and their interrelationships are presented in Figure 2. In brief, family caregivers described their family members with advanced dementia as vulnerable (Theme 1: Vulnerability of Advanced Dementia). Given this, finding the “right” paid caregiver was an essential and often-difficult process (Theme 2: The ‘Right’ Paid Caregiver). Once in place, family caregivers prioritized consistent care routines and the continuity of this individual paid caregiver (Theme 3: Paid Caregiver Continuity). The stability and trust that resulted were what enabled paid caregivers to make a positive impact on both people with advanced dementia and their family caregivers (Theme 4: Stability Impacts People with Advanced Dementia and Their Families). Each of these themes are reviewed in detail below.

Figure 2: The Role and Impact of Paid Caregivers in Home-Based Dementia Care.

Theme 1: Vulnerability of Advanced Dementia

Family caregivers described how dementia rendered their family members particularly vulnerable and how they needed to be vigilant to make sure their family members received good care (Table 2). Given this vulnerability, family caregivers expressed the need for a paid caregiver who could provide individualized, person-centered care to the person with advanced dementia. Family caregivers viewed paid caregivers as having an expansive role: “I think a lot of the time people [with advanced dementia] are scared that they’re not remembering things…. I think a home attendant knows how to handle them, gives them comfort, reassures them that everything is going to be okay, helps them out, keeps them from harm” (Caregiver 11). Care included both physical care (e.g., changing diapers and/or spoon feeding the person with dementia) and relational care (e.g., calming the person with dementia when they became upset, emotionally engaging with the person with dementia). Family members emphasized that each person with advanced dementia’s care needs were unique and care needed to be person-centered. One daughter explained, “When the home aide first came in, she said ‘You don’t have to tell me how to do my work. I’ve been doing this 11 years.’ Sorry, but every case is different. You know what I mean? I don’t care if you were there 50 years. Every case is different.” (Caregiver 2).

Table 2:

The Role of Paid Caregivers in Home-Based Dementia Care

| Theme 1: Vulnerability of Advanced Dementia |

| “You worry a great deal because you are entrusting your parent that you love a great deal to a total stranger… Now, a regular person can really tell you, ‘Okay, this person pushed me’ or whatever, but a person with dementia who can’t tell you that something happened-- that’s a lot of worry for me.” (Caregiver 20, daughter) |

| “You have to check that [security] camera because… you’re going to go at work and not be at peace, not knowing what’s going to happen with your mom. Is she being fed? Is she being changed her diapers?” (Caregiver 18, daughter) |

| “You have to be vigilant… [When the paid caregivers first started] I acted like I was dumb, but I paid attention. I talked with them and with my uncle… I was trying to understand what they said when I wasn’t around.” (Caregiver 14, niece) |

| Theme 2: The “Right” Paid Caregiver/s |

| I think I probably had, during that [initial] time, at least 10 or 15 different people… I didn’t have the greatest experience with a lot of people…. and so finally, I settled down on one person who is very good and knows about this. Her mother had a similar problem of dementia so she knew exactly what was going on and she’s doing an excellent job” (Caregiver 3, husband). |

| We were having where workers came in and worked with him and didn’t want to stay because he woke up at night… so we had a transition of people, different workers coming and going for a time and that’s very disruptive… We just were very fortunate that we finally got two people that they’re so diligent with their work. They care, they come in, and they do their job. They work well with us. They work well with my dad” (Caregiver 20, daughter) |

| “I called [the agency] up and… I said, ‘You know what? It’s not working out for all the hours. I’d like the woman from 2:00 to 6:00, Monday through Friday with your agency, but can I go to another agency [for the other shifts]?’ He says, ‘Of course, you can…’ I went to another agency in Brooklyn. They found me a Haitian person that I’m very happy with now.” (Caregiver 9, daughter) |

| Theme 3: Paid Caregiver Continuity |

| “[The person with dementia is] more confused or they’re more agitated when you have a variety of different people coming through… They’re more confused, and they’re more agitated… it’s like resetting constantly. They get agitated and confused and then you don’t know whether it’s the medicine that’s making them confused and agitated or whether it’s just that they’re not in sync with the new person. Again, it works a lot better when you have somebody, stable people who are good and a good fit.” (Caregiver 20, Daughter) |

| “There are things that [people with dementia] have to follow-- a routine-- because that’s another thing we want to do… The worst thing you can do is change things for them consistently or constantly. You have one person come and do this, that way and the other, it’s very confusing for them. The more you can maintain a routine, the better for the patient or the person that you’re caring for because they’re in a groove. You have to adjust to their groove.” (Caregiver 5, Son) |

| “That somebody new would have to come in and I couldn’t be there to-- like my mother, anybody new would scare her. She would be uncomfortable. So I was concerned that a new person may have to come in and how do I deal with this during COVID?” (Caregiver 11, Daughter) |

Theme 2: The “Right” Paid Caregiver/s

Given the vulnerability of advanced dementia and the need for comprehensive, person-centered care, finding the “right” paid caregiver was extremely important for family caregivers. The majority described wanting a paid caregiver who would treat the person with advanced dementia like a member of their own family. However, finding this “right” person was often a long and difficult process of trial and error as family caregivers looked for a good match to meet the needs of both the person with advanced dementia and the family (Table 2). Family caregivers described being at different points of this process of finding the “right” paid caregiver. While many expressed deep gratitude for their family members’ paid caregivers, one son had nearly given up on finding a paid caregiver who meet both his mother’s physical care and relational care needs. He said, “What they do is they keep the house clean, they keep her clean, and they cook for her. That’s basically all that’s included, so nothing more…. if the ladies are watching something, a lot of times, they’re watching something on their cellphone, so they’re there, but they’re not really there” (Caregiver 5).

In addition, most people with advanced dementia had multiple paid caregivers to meet their round-the-clock needs. Several family caregivers who were interviewed described that while they had one well-matched paid caregiver in place, they were still looking for others to cover additional shifts and even coordinated across multiple agencies to find “good” caregivers. When new paid caregivers started, long-time paid caregivers sometimes assumed an enhanced training and supervisory role in care. One daughter described telling a new paid caregiver, “Listen to the aide that’s been there a long time because she knows how to maneuver mama” (Caregiver 1). One family caregiver even deferred decisions about hiring and firing new people to her aunt’s long-time, privately paid caregiver: “[The paid caregiver] fired somebody. She told me that there were things that were going on that she was not comfortable with, and I relied on her to ask the person not to come back” (Caregiver 21).

Theme 3: Paid Caregiver Continuity

Once in place, family caregivers described the importance of retaining the “right” paid caregiver so that rapport could develop over time. A granddaughter explained, “[My grandmother] has, actually, told this woman that she loves her…. I think she really does. This woman has been changing her diapers and feeding her now for quite some time, and the aide also has told me, she says, ‘I love your grandma.’ So, they have their connection that [occurs] after all these years” (Caregiver 4). Many described that this bond developed and persisted even in the most advanced stages of dementia and witnessing it helped families be confident their family member was in good hands.

Family caregivers described many ways that paid caregiver continuity was important for their family member with advanced dementia (Table 2). Several contrasted this to what happened when a regular, long-time paid caregiver was away; during these times, family caregivers were on guard and often opted to supervise covering paid caregiver in-person. As one caregiver described, “Every time [the regular paid caregivers] take days off and someone new comes in, I am there the minute they come through the door to meet them because I want them to know who I am. I want them to know that I’m watching. I’m aware. And if they have questions for me and to let them know what my mom needs, what’s important for her, her medications, all that stuff” (Caregiver 12).

Theme 4: Stability Impacts People with Advanced Dementia and Their Families

Given the significant care burden of families of providing care to people with advanced dementia, several family caregivers described how much simply having any paid care at all changed their lives. A daughter described what it was like for her son before her father had paid care:

“Prior to the homecare… My father would call [my son] and say, ‘I’m hungry’ at 2:00 [PM]… and [my son] would constantly go every day and see him and check on him… Then he got a job … which was a very good job, but where he couldn’t leave until 6:00 [PM]. My son left his job and resigned. I was telling him, ‘Why did you do that… you needed to stay in that great job!’… and [my son] was like, ‘Because when grandpa will call me and say ‘I’m hungry’ at 11:00, I’m telling him ‘I can’t feed you. I can’t bring any food until 6:00 PM… It will break my heart” (Caregiver 20).

Another daughter said, “[My mother] wasn’t getting help right away. Every day or every other day, during my lunch hour, I would come to my mother’s house from my office, bathe her, and feed her. It was a year. It was a hard year. I remember that first year. I remember the first time that she had 24-hour care was the first night I had slept a whole night in a year” (Caregiver 12).

Yet more often, the benefits of receiving paid care were realized only when the person with advanced dementia received stable care from the “right”, consistent paid caregivers. These benefits were for both the person with advanced dementia and for the family caregivers (Table 3). The most commonly described benefits of stable paid caregiving for people with advanced dementia were related to affect, behavior, and eating. Family caregivers perceived that people with advanced dementia were happier, calmer, and ate better when attended to by the “right” paid caregivers. When family caregivers could trust that their family members were being well cared for, they felt less stress. Many then felt able to work outside of the home and engage more meaningfully with other parts of their life (e.g., spending time with grandchildren, traveling).

Table 3:

The Impact of Paid Caregivers in Home-Based Dementia Care

| Theme 4: Stability Impacts on People with Advanced Dementia and Their Families | ||

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | Benefits to People with Advanced Dementia | Benefits to Family Caregivers |

| Caregiver 20, Daughter | He’s much more tranquil and even when he gets agitated, [the paid caregivers] know how to work with him. He immediately calms down… They work with him differently, and it’s stable. The stability helps a lot because it’s more routine. They know what they already know: what he likes to eat, his mannerisms, and what gets him upset. | It impacts your life in every social aspect, in [every] financial aspect, in every way…. you’re trying to juggle it all and eventually you get exhausted, you break down. And then that doesn’t help the senior at all because now they don’t have the people that they need to be able to be there for them. So, yes, the home attendant really relieves that pressure. |

| Caregiver 21, Cousin | She eats better, sleeps better, she’s cooperative…. and the ladies, they sing with her because the thing that calms her down the most is [when] they sing and dance with her…. She has a good life with them. | [The paid caregivers] are security. They let me sleep at night. They provide stability. I could not possibly do it without them. She would be in a facility. We could not take care of her without them-- impossible. |

| Caregiver 18, Daughter | I feel [my mother] would notice [her paid caregiver] and light up…. She knew who she was and she was so happy to hear her. And that’s great when you see that. | I felt confident enough that I could leave and that my mother was going to be well here. If I didn’t have that service - well, the two that I have here, which like I said before, we’ve created a bond-- I don’t know what I would’ve done [without them]. I think I would have to leave my job. |

| Caregiver 9, Daughter | When [the paid caregivers] come in, she smiles. [My mother] was like, “I remember you,” from her eyes. You can see that she remembers them. The fact that she allows them to feed her in the morning, that means she trusts them. | You as a caregiver, you won’t get to rest. It could give you depression. Sometimes, I thought I was going to have a nervous breakdown from lack of sleep and just overthinking everything. When it clicks, it clicks well, but when it doesn’t click, it’s like the worst feeling in the world. |

| Caregiver 12, Daughter | Besides taking care of [my mother], feeding her, bathing her, and clothing her, [the paid caregivers] do all that, they sustain her… They sit with her. They talk to her. They laugh with her… I don’t know what more to say except that they just do I think what they would do for their own mother. You know what I mean? They’re doing what they would do for their own parent. | I feel just a sense of peace because [my mother] is being taken care of by two women…. They allow us, as a family, to have our own lives and to be able to keep going. It makes us better people, because I remember in the beginning, I was so frustrated with my mother… I was so angry because I was so tired… I had a lot of resentment. I felt like I was taking it out on [my mother], like I was mean to her. I hated myself for that. |

Discussion

Family caregivers perceived multiple and inter-related benefits when people with advanced dementia had stable care; stable care resulted when paid caregivers were well-matched to the unique needs of both the person with advanced dementia and their family and there was continuity in the individuals providing care. While we began by asking family caregivers about their experiences with paid care in the COVID-19 pandemic, conversations quickly became more expansive as family caregivers expressed how the vulnerability of advanced dementia (rather than any specific COVID-related concerns) drove how they worked with their family member’s paid caregivers in the home. These findings underscore the important role that paid caregivers can play in home-based dementia care and suggest ways to maximize the positive impact of paid caregivers on the people with advanced dementia they care for and the families with whom they share care.

Family caregivers viewed their family members with advanced dementia as vulnerable and voiced the importance of finding the “right” paid caregiver matched to the person with advanced dementia and family’s unique needs. While it is widely accepted in the dementia-care community that dementia care should be person-centered and cultivate the important interpersonal relationships that support people with dementia, this is not the standard of care in the homecare industry in the United States. Despite evidence to the contrary (Franzosa et al., 2019; Reckrey, Tsui, et al., 2019), paid caregivers are often viewed as interchangeable workers who complete a discrete set of personal care tasks outlined in a standardized plan of care. They receive minimal training and are rarely given information about their clients before they are sent into the home (Franzosa et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2013; Sterling et al., 2018).

Our findings suggest this approach is insufficient for the care of people with dementia in general and for people with advanced dementia in particular, who become less able to self-direct care over time. As a result, there is growing interest in training programs for paid caregivers that specifically provide dementia-care training and may or may not result in additional certifications or advanced-aide designations (Goh et al., 2018; Polacsek et al., 2020). Our findings suggest that such trainings should focus not only on physical care but also relational care needs and emphasize the unique personhood of those with dementia; they should be a standard part of paid caregiver training.

Our study confirms previous findings that the challenges coordinating care in the home make finding the “right” paid caregiver especially important (Shaw et al., 2020). The family caregivers in our study described this fit as not simply about cultural or language concordance or particular skill set, but a matter of well-matched personality and approach. Specifically, family caregivers looked to find paid caregivers who treat the person with advanced dementia with respect and kindness and hoped paid caregivers would act as trusted extensions of the person with advanced dementia’s own family. For families of people cared for by Medicaid-funded paid caregivers, this process seemed to happen largely by trial and error: families coordinated with home care agencies to have new paid caregivers assigned until the “right” match was found. Agencies might do more to facilitate good matches by eliciting bidirectional feedback that allows both people with dementia and/or their family caregivers as well as paid caregivers to assess how care is working. This process would need to explicitly acknowledge that the process of building trusting relationships takes time (Reckrey, Geduldig, et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2021; Woodward et al., 2004).

Once a well-matched paid caregiver was in place, family caregivers prized continuity of the individual providing care. A large body of health services research suggest that provider continuity (i.e, consistency in the individual doctor, nurse, physical therapist, or other provider providing health care services) is important for patient outcomes (Amjad et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2011; Saultz & Lochner, 2005). While the impact of paid caregiver continuity has not been formally evaluated, it is not surprising that family caregivers of people with advanced dementia found this important. Attentive, team-based dementia care is essential to avoid many of the worst complications of dementia (e.g., aspiration, pressure ulcers) and consistent routines may help people with dementia thrive (“2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures,” 2021; Fazio et al., 2018).

Continuity in a well-matched paid caregiver created stability in paid dementia care and this in turn made it possible for paid caregivers to have a meaningful, positive impact on both the person with advanced dementia and their family caregivers. Stability should be prioritized in the home-based long-term care of people with advanced dementia, but additional work is needed in order to understand how to operationalize, monitor, and support stability in paid care. In order to do this, focus on understanding and supporting the paid care workforce is essential. In the fragmented United States’ long-term care system, turnover of paid caregivers is common and paid caregivers may experience significant instability in their own lives as they balance other family and social responsibilities while working low-wage jobs (Buch, 2013; Stone et al., 2017). From the perspective of people with dementia and their family, this may impact both chances of finding the “right” paid caregiver as well as the continuity of that individual.

Compensating paid caregivers a living wage is an essential first step to support the paid caregiving workforce (Weller et al., 2020), especially given the large numbers of individuals leaving the field in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic (Graham, 2022; Scales, 2021). Additionally, investments in team-based trainings for paid caregivers and the health care workers they collaborate with could have the dual benefits of increasing knowledge and competencies related to dementia care and improving workforce retention (Stone & Bryant, 2019). Finally, additional attention needs to be paid to how paid care matters for people with dementia and their families. Emerging payment models like Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans that explicitly link medical care with long-term care (Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs)) may help promote integration of paid caregivers in healthcare teams by incentivizing medical care providers to consider the ways that factors like paid caregiver stability impact patient outcomes.

As is common in qualitative projects, the generalizability of this study is limited by the population studied (i.e., largely Hispanic or Latino/a with significant functional impairment, predominantly female) and the care setting (i.e., a dense urban area in the United States with generous state Medicaid funding of long-term paid care in the home). Future work should evaluate if the themes of our study remain as salient for different populations (e.g., patients and caregivers from other regions, racial/ethnic backgrounds) and specifically if and how stability in Medicaid-funded paid care differs from privately funded paid care. In addition, given that people with advanced dementia in our study had both high levels of paid care and were enrolled in home-based primary care, the experiences and perspectives of their family caregivers may not reflect the experiences of those with minimal or poorly coordinated care. Yet because of this, the family caregivers interviewed can be considered key informants who are able to speak meaningfully about what may contribute to high-quality paid care in advanced dementia. Moreover, as the locus of long-term care continues to shift from institutions to communities, high levels of paid care like those observed in our study will likely be necessary to support the home-based care of people with advanced dementia.

As the number of people with dementia living at home grows, paid caregivers will play an increasingly vital role in supporting the health and well-being of people with advanced dementia and their families. Advocates for high quality, person-centered home-based dementia care can no longer overlook the important role that paid caregivers can and do play within the dementia care team and should work with policy makers to promote stable paid care for people with advanced dementia living at home.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds:

Paid caregivers are rarely studied in relation to the individuals they care for or the families with whom they share care.

The impact of paid care on people with advanced dementia living at home and their families is underexplored.

Applications of study findings:

Additional training and bidirectional feedback may help paid caregivers of people with advanced dementia work more effectively with families to provide person-centered dementia care at home.

Given the importance of stable caring relationships among people with advanced dementia and their paid and family caregivers, efforts to support the stability of the paid caregiving workforce may improve outcomes for both people with advanced dementia and their families.

Funding:

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (K23AG066930 to JR).

Research Ethics:

All study protocols were approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board (ID STUDY-19–01206).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. (2021). Alzheimers Dement, 17(3), 327–406. 10.1002/alz.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amjad H, Carmichael D, Austin AM, Chang CH, & Bynum JP (2016). Continuity of Care and Health Care Utilization in Older Adults With Dementia in Fee-for-Service Medicare. JAMA Intern Med, 176(9), 1371–1378. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch ED (2013). Senses of care: Embodying inequality and sustaining personhood in the home care of older adults in Chicago. Am Ethnol, 40(4), 637–650. 10.1111/amet.12044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/SpecialNeedsPlans/D-SNPs

- Fazio S, Pace D, Maslow K, Zimmerman S, & Kallmyer B. (2018). Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Practice Recommendations. Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S1–S9. 10.1093/geront/gnx182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzosa E, & Tsui EK (2021). “Family Members Do Give Hard Times”: Home Health Aides’ Perceptions of Worker–Family Dynamics in the Home Care Setting. In Aging and the Family: Understanding Changes in Structural and Relationship Dynamics. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Franzosa E, Tsui EK, & Baron S. (2018). Home Health Aides’ Perceptions of Quality Care: Goals, Challenges, and Implications for a Rapidly Changing Industry. New Solut, 27(4), 629–647. 10.1177/1048291117740818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzosa E, Tsui EK, & Baron S. (2019). “Who’s Caring for Us?”: Understanding and Addressing the Effects of Emotional Labor on Home Health Aides’ Well-being. Gerontologist, 59(6), 1055–1064. 10.1093/geront/gny099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1967). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Goh AMY, Gaffy E, Hallam B, & Dow B. (2018). An update on dementia training programmes in home and community care. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 31(5), 417–423. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. (2022). Pandemic-Fueled Shortage of Home Health Workers Strand Patients Without Necessary Care. Retrieved April 7, 2022 from https://khn.org/news/article/pandemic-fueled-home-health-care-shortages-strand-patients/

- Harrison KL, Ritchie CS, Patel K, Hunt LJ, Covinsky KE, Yaffe K, & Smith AK (2019). Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults with Moderately Severe Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc, 67(9), 1907–1912. 10.1111/jgs.16054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, & Martin RL (1982). A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry, 140, 566–572. 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, & Wolff JL (2015). The Disproportionate Impact Of Dementia On Family And Unpaid Caregiving To Older Adults. Health Aff (Millwood), 34(10), 1642–1649. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye HS (2014). Toward a model long-term services and supports system: state policy elements. Gerontologist, 54(5), 754–761. 10.1093/geront/gnu013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye HS, Harrington C, & LaPlante MP (2010). Long-term care: who gets it, who provides it, who pays, and how much? Health Aff (Millwood), 29(1), 11–21. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CM, Morgan JC, & Jason KJ (2013). Home care workers: interstate differences in training requirements and their implications for quality. J Appl Gerontol, 32(7), 804–832. 10.1177/0733464812437371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, & Perkins MM (2013). Convoys of care: theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. J Aging Stud, 27(1), 15–29. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1986). But Is It Rigorous? Trustworthiness and Authenticity in Naturalistic Evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 30, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, & Moules NJ (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein K, Hernandez CR, DeCherrie LV, & Soriano TA (2011). The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program: meeting the needs of the urban homebound population. Care Manag J, 12(4), 159–163. 10.1891/1521-0987.12.4.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacsek M, Goh A, Malta S, Hallam B, Gahan L, Cooper C, Low LF, Livingston G, Panayiotou A, Loi S, Omori M, Savvas S, Batchelor F, Ames D, Doyle C, Scherer S, & Dow B. (2020). ‘I know they are not trained in dementia’: Addressing the need for specialist dementia training for home care workers. Health Soc Care Community, 28(2), 475–484. 10.1111/hsc.12880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey JM (2020). COVID-19 Confirms It: Paid Caregivers Are Essential Members of the Healthcare Team. J Am Geriatr Soc, 68(8), 1679–1680. 10.1111/jgs.16566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey JM, Boerner K, Franzosa E, Bollens-Lund E, & Ornstein KA (2021). Paid Caregivers in the Community-Based Dementia Care Team: Do Family Caregivers Benefit? Clin Ther. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reckrey JM, Geduldig ET, Lindquist LA, Morrison RS, Boerner K, Federman AD, & Brody AA (2019). Paid Caregiver Communication With Homebound Older Adults, Their Families, and the Health Care Team. Gerontologist. 10.1093/geront/gnz067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reckrey JM, Morrison RS, Boerner K, Szanton SL, Bollens-Lund E, Leff B, & Ornstein KA (2020). Living in the Community With Dementia: Who Receives Paid Care? J Am Geriatr Soc, 68(1), 186–191. 10.1111/jgs.16215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey JM, Tsui EK, Morrison RS, Geduldig ET, Stone RI, Ornstein KA, & Federman AD (2019). Beyond Functional Support: The Range Of Health-Related Tasks Performed In The Home By Paid Caregivers In New York. Health Aff (Millwood), 38(6), 927–933. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey JM, Watman D, Tsui EK, Franzosa E, Perez S, Fabius CD, & Ornstein KA (2022). “I Am the Home Care Agency”: The Dementia Family Caregiver Experience Managing Paid Care in the Home. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(3). 10.3390/ijerph19031311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, & Ormston R. (2014). Qualitative research practice : a guide for social science students and researchers (Second edition. ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Burgdorf JG, Kramer C, & Chase JD (2021). Family Caregivers’ Conceptions of Trust in Home Health Care Providers. Res Gerontol Nurs, 14(4), 200–210. 10.3928/19404921-20210526-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Rosati RJ, Rosenfeld P, & Marren JM (2011). Continuity in home health care: is consistency in nursing personnel associated with better patient outcomes? J Healthc Qual, 33(6), 33–39. 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samus QM, Black BS, Bovenkamp D, Buckley M, Callahan C, Davis K, Gitlin LN, Hodgson N, Johnston D, Kales HC, Karel M, Kenney JJ, Ling SM, Panchal M, Reuland M, Willink A, & Lyketsos CG (2018). Home is where the future is: The BrightFocus Foundation consensus panel on dementia care. Alzheimers Dement, 14(1), 104–114. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saultz JW, & Lochner J. (2005). Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med, 3(2), 159–166. 10.1370/afm.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savla J, Roberto KA, Blieszner R, McCann BR, Hoyt E, & Knight AL (2021). Dementia Caregiving During the “Stay-at-Home” Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 76(4), e241–e245. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales K. (2021). It Is Time to Resolve the Direct Care Workforce Crisis in Long-Term Care. Gerontologist, 61(4), 497–504. 10.1093/geront/gnaa116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw AL, Riffin CA, Shalev A, Kaur H, & Sterling MR (2020). Family Caregiver Perspectives on Benefits and Challenges of Caring for Older Adults With Paid Caregivers. J Appl Gerontol, 733464820959559. 10.1177/0733464820959559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spetz J, Stone RI, Chapman SA, & Bryant N. (2019). Home And Community-Based Workforce For Patients With Serious Illness Requires Support To Meet Growing Needs. Health Aff (Millwood), 38(6), 902–909. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling MR, Silva AF, Leung PBK, Shaw AL, Tsui EK, Jones CD, Robbins L, Escamilla Y, Lee A, Wiggins F, Sadler F, Shapiro MF, Charlson ME, Kern LM, & Safford MM (2018). “It’s Like They Forget That the Word ‘Health’ Is in ‘Home Health Aide’“: Understanding the Perspectives of Home Care Workers Who Care for Adults With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc, 7(23), e010134. 10.1161/JAHA.118.010134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, Sutton JP, Bryant N, Adams A, & Squillace M. (2013). The home health workforce: a distinction between worker categories. Home Health Care Serv Q, 32(4), 218–233. 10.1080/01621424.2013.851049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, Bryant NS, Hermer L, & Squillace MR (2017). Predictors of Intent to Leave the Job Among Home Health Workers: Analysis of the National Home Health Aide Survey. Gerontologist, 57(5), 890–899. 10.1093/geront/gnw075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI, & Bryant NS (2019). The Future of the Home Care Workforce: Training and Supporting Aides as Members of Home-Based Care Teams. J Am Geriatr Soc, 67(S2), S444–S448. 10.1111/jgs.15846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strommen J, Fuller H, Sanders GF, & Elliott DM (2020). Challenges Faced by Family Caregivers: Multiple Perspectives on Eldercare. J Appl Gerontol, 39(4), 347–356. 10.1177/0733464818813466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller C, Almeida B, Cohen M, & Stone R. (2020). Making Care Work Pay: How Paying at Least a Living Wage to Direct Care Workers Could Benefit Care Recipients, Workers, and Communities. https://www.ltsscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Making-Care-Work-Pay-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Woodward CA, Abelson J, Tedford S, & Hutchison B. (2004). What is important to continuity in home care?. Perspectives of key stakeholders. Soc Sci Med, 58(1), 177–192. 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00161-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.