Abstract

Purpose

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals, and LB women specifically, have an increased risk for psychiatric morbidity, theorized to result from stigma-based discrimination. To date, no study has investigated the mental health disparities between LGB and heterosexual AQ1individuals in a large cross-national population-based comparison. The current study addresses this gap by examining differences between LGB and heterosexual participants in 13 cross-national surveys, and by exploring whether these disparities were associated with country-level LGBT acceptance. Since lower social support has been suggested as a mediator of sexual orientation-based differences in psychiatric morbidity, our secondary aim was to examine whether mental health disparities were partially explained by general social support from family and friends.

Methods

Twelve-month prevalence of DSM-IV anxiety, mood, eating, disruptive behavior, and substance disorders was assessed with the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview in a general population sample across 13 countries as part of the World Mental Health Surveys. Participants were 46,889 adults (19,887 males; 807 LGB-identified).

Results

Male and female LGB participants were more likely to report any 12-month disorder (OR 2.2, p < 0.001 and OR 2.7, p < 0.001, respectively) and most individual disorders than heterosexual participants. We found no evidence for an association between country-level LGBT acceptance and rates of psychiatric morbidity between LGB and heterosexualAQ2 participants. However, among LB women, the increased risk for mental disorders was partially explained by lower general openness with family, although most of the increased risk remained unexplained.

Conclusion

These results provide cross-national evidence for an association between sexual minority status and psychiatric morbidity, and highlight that for women, but not men, this association was partially mediated by perceived openness with family. Future research into individual-level and cross-national sexual minority stressors is needed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00127-022-02320-z.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Health status disparities, Mental disorders, Cross-national, Sexual orientation

Introduction

Lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) individuals are at an increased risk for mental health issues as compared to heterosexual individuals [1–7]. For example, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders are at least 1.5 times more likely to occur in LGB individuals than in heterosexual individuals [2, 3, 6, 8]. Among LGB individuals, gender differences in psychiatric morbidity have also been documented: compared to heterosexual participants, gay and bisexual (GB) men have been found to experience a higher risk for mood disorders [4, 5], while lesbian and bisexual (LB) women appear to be more adversely affected by substance-related issues [2, 3, 5]. Overall, the risk for LGB individuals to be diagnosed with at least one disorder in the last 12 months appears to be twice as high as compared to heterosexual individuals [5]. In addition, among sexual minorities, bisexual individuals have been found to have especially high risks for experiencing adverse mental health outcomes [9].

Notably, these mental health disparities between LGB and heterosexual individuals have been well documented by national studies [4, 5, 7, 8, 10–12], which have predominantly focused on Australian [10, 11], European [4, 5, 7], and North-American [8, 11] contexts. However, differences in socio-structural factors, such as the social acceptance of LGB individuals, have been found to be related to country-level effects on health [13, 14] and happiness [15] among sexual minority individuals. Similarly, there is evidence of cross-national [16, 17], and within-US state-level effects on psychiatric morbidity among sexual minority individuals [18, 19]. However, because of cross-national differences in the prevalence of mental disorders generally, it is unclear if cross-national differences in mental health outcomes among LGB individuals are actually specific to LGB individuals or simply reflect more general differences in the prevalence of mental disorders across countries. Some cross-national evidence for disparities in mental health outcomes (specifically depression, anxiety disorders, and alcohol use disorders) between LGB and heterosexual individuals also comes from meta-analyses [20, 21]. However, studies assessing mental health disparities between LGB and heterosexual individuals across a broad range of mental disorders in a cross-national sample, including Western and non-Western countries, are lacking [21].

Minority stress and social support as a mediator

In addition to societal stressors related to their stigmatized sexual orientation, there is consistent evidence linking the elevated rates of psychiatric morbidity among LGB individuals to the experience of individual-level stressors (e.g. sexuality-based violence, as well as internalized societal stigma) [22–26]. In addition to having a cumulative effect on psychiatric morbidity [23, 27], it has been suggested that minority stress may result in elevated emotion dysregulation, interpersonal issues, and cognitive processes that ultimately increase LGB people’s risk for psychopathology [27]. According to Hatzenbuehler’s psychological mediation framework, sexual minority individuals may experience poorer social relationships as a consequence of social rejection and isolation due to their sexual minority status [28], which in return might reduce their resources to cope with general life stressors.

Indeed, compared to heterosexual individuals, sexual minorities have been found to report lower perceived social support in general [11, 29] and to report less social support from family as compared to friends [11]. In line with the psychological mediation framework, higher social support has been found to result in better coping and resilience among sexual minority individuals [29, 30]. Specifically, support from family as compared to friends appears to be an important predictor of the mental health of LGB individuals [31]. Conversely, there is some evidence that lower social support may mediate the adverse effects of minority stress on health generally [32], and mental health specifically [33, 34]. In addition, there are some findings that suggest that social support may mediate the relationship between sexual minority status and psychiatric morbidity among young men, but not women [28].

Current study

The primary aim of the current study was to contribute to this literature by examining global mental health disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. The WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative (WHMS) consists of a cross-national dataset that includes a comprehensive set of mental disorders. As such, it offers a unique opportunity to study disparities in mental health outcomes based on sexual orientation in the largest cross-national general population sample investigating the most comprehensive set of disorders to date. Based on previous national population studies, we expected LGB individuals to be more likely to report adverse mental health outcomes across multiple disorder groups as compared to heterosexual individuals. In addition, we explored the association between country-level social acceptance and the increased risk for mental disorders among LGB individuals compared to heterosexual individuals. The second aim of this study was to investigate the role of social support as a potential mediating factor for mental health issues among LGB individuals.

Methods

Sample

Data came from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys [35]. Translated versions of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 [36] were administered in 29 surveys across the world through stratified multistage clustered area probability household sampling between 2001 and 2012 (average response rate 69.5%, range 45.9–97.2%) based on Census area data, with the exact recruitment and data collection procedures varying somewhat by country [37]. Adults from the non-institutionalized population were selected to generate population-representative samples (for an overview of the individual country sub-samples see Supplemental Table 1). A total of 13 surveys assessing sexual orientation were included in the current study. All surveys within the World Mental Health Survey Initiative are commonly presented by country income group; surveys were grouped into a low/middle-income country group (Colombia, Colombia (Medellin), Mexico, Peru, and Romania) and a high-income country group (Argentina, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Portugal, Spain (Murcia), United States). Country income categories were based on the World Bank criteria at the time of each survey [38].

Table1.

Prevalence of heterosexual, gay/bisexual, and lesbian/bisexual, and associated demographics

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | GB | Heterosexual | LB | |

| (N = 19,530) | (N = 357) | (N = 26,552) | (N = 450) | |

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | |

| Education status | ||||

| Low | 14.4 (0.34) | 11.1 (2.31) | 18.2 (0.35) | 18.7 (2.48) |

| Low-average | 21.2 (0.41) | 16.7 (2.24) | 24.8 (0.38) | 23.9 (2.68) |

| High-average | 39.3 (0.48) | 31.2 (2.99) | 31.6 (0.44) | 31.3 (2.87) |

| High | 25 (0.47) | 41.1 (3.26) | 25.4 (0.44) | 26.1 (2.62) |

| X2 = 26.7 p ≤ 0.001 | X2 = 3.1 p = 0.378 | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently married | 65.1 (0.48) | 31.8 (3.08) | 61.1 (0.44) | 42.4 (3.01) |

| Previously married | 8.4 (0.23) | 9 (1.65) | 18.3 (0.34) | 15.7 (2.01) |

| Never married | 26.5 (0.47) | 59.2 (3.07) | 20.6 (0.37) | 41.9 (3.07) |

| X2 = 71.7 p ≤ 0.001 | X2 = 56.6 p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 72.9 (0.44) | 74.9 (2.84) | 53.8 (0.46) | 62.6 (3.2) |

| Student | 4.7 (0.24) | 3.2 (1.14) | 4.4 (0.21) | 7.3 (1.94) |

| Homemaker | 1.8 (0.14) | 2.4 (0.8) | 21.2 (0.39) | 15.7 (2.23) |

| Retired | 13.4 (0.3) | 12.5 (2.27) | 15.2 (0.34) | 6.1 (1.39) |

| Other | 7.2 (0.27) | 7 (1.38) | 5.5 (0.21) | 8.2 (1.4) |

| X2 = 12.1 p = 0.017 | X2 = 11.4 p = 0.022 | |||

| Income statusa | ||||

| Low | 22.4 (0.43) | 18 (2.61) | 28.5 (0.47) | 29.1 (3) |

| Low-average | 23.5 (0.43) | 19 (2.66) | 25.9 (0.4) | 21.4 (2.68) |

| High-average | 28 (0.45) | 24.8 (2.78) | 24.6 (0.4) | 28.4 (2.85) |

| High | 26.2 (0.48) | 38.2 (3.11) | 21.1 (0.39) | 21 (2.38) |

| X2 = 18.4 p ≤ 0.001 | X2 = 4.4 p = 0.218 | |||

| Age (mean, SD) | ||||

| 43.5 (0.17) | 41.5 (1.04) | 44.8 (0.16) | 41.1 (1.07) | |

| t = − 2.3 p = 0.022 | t = − 5.1 p ≤ 0.001 | |||

α = 0.005; aFor Income Status, the sample size was reduced (male: heterosexual = 18,664, GB = 344; female: heterosexual = 25,637, LB = 445)

To reduce participant burden, the CIDI was administered in two parts. All participants completed Part I, assessing core mental disorders. Part II, assessing other disorders and correlates, was administered to all participants with any lifetime Part I diagnosis and a probability subsample of other Part I participants. Part II respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection. Trained lay interviewers administered surveys face-to-face at all survey sites. Translation, back-translation, harmonization, and quality control procedures were similarly standardized at all participating sites [39]. In accordance with the respective Ethics Review boards, verbal or written informed consent was obtained. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Measures

Socio-demographics

The variables assessed were gender, age, marital status (married, never married, or previously married), employment status, current income (categorized into country-specific quartiles of gross income per family member in a household), and highest level of education (categorized into country-specific quartiles).

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation was assessed using a single item (“Which of the following best describes your sexual orientation?”) in the part II sample, with the exception of Argentina and New Zealand, where it was assessed in part I. Participants who identified as something other than the answer options listed (“heterosexual or straight”, “homosexual or gay”, or “bisexual”), who were not sure or did not know, as well as those who refused to answer the question or had a missing value were excluded from the sample; females who indicated 'homosexual' will be referred to as ‘lesbian’. In all countries except Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand, participants who reported that they had never had sexual intercourse were not presented with the sexual orientation question, unless they indicated that they had biological children.

Mental disorders

Analyses were conducted with 12-month CIDI DSM-IV diagnoses. We included the following mental disorders: mood disorders (major depressive disorder [MDD], dysthymia, bipolar disorder I/II/subthreshold), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]), behavioral disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], ODD/CD (oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, combined into a single variable due to low prevalence), intermittent explosive disorder [IED]), substance use disorders (alcohol and drug abuse and dependence), and eating disorders (bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, combined into a single variable).

Social support quality

Social support quality was separately assessed for family and friends using a two-item measure. Participants reported both the frequency of contact (“How often do you talk on the phone or get together with [relatives/friends]?”; “less than once a month”, “about once a month”, “a few times a month”, “a few times a week”, or “most every day”) as well as their general openness to talk to either family or friends about their worries (“How much can you open up to your [relatives/friends] if you need to talk about your worries?”; “not at all”, “a little”, “some”, or “a lot”,). Participants who answered “don’t know” or refused to answer any of the questions, as well as participants with missing values were removed from the sample for the moderation analysis. Social support quality was assessed in a subset of eleven countries (Argentina, Australia, Colombia, Colombia (Medellin), Japan, Mexico, Northern Ireland, Peru, Romania, Spain (Murcia), United States). Notably, the openness item assessed openness with relatives or friends in general, and not specifically related to sexual minority status as the aim of this paper was to assess differences between heterosexual and LGB individuals.

Social acceptance

Data on social acceptance were taken from the LGBT Global Acceptance Index [40] which summarizes societal acceptance based on surveys across 141 different countries from 1981 until 2014. For each of the 13 countries included in this study, the value that most closely corresponded to the year that the survey was conducted was selected.

Analyses

We first examined the prevalence of sexual orientation sub-group to provide readers with an overview of the specific characteristics of the sample as it related to the current study. To this end, we also tested how sociodemographic variables were associated with sexual orientation using linear regression for continuous variables and multinomial logistic regression for categorical variables.

First aim

We used logistic regression to test the association between sexual orientation and 12-month mental disorders separately by gender. The decision to conduct gender-stratified analyses was determined a priori based on a review of the literature, which has suggested important gender differences in the associations between sexual orientation and mental disorders [2, 3, 5]. In addition, we used logistic regression to test the association between sexual orientation and 12-month mental disorders comparing LG participants and bisexual participants to heterosexual participants, as well as bisexual participants to LG participants, while controlling for gender. The size of sexual orientation sub-groups did not allow us to conduct this comparison as a gender-stratified analysis. Although our main analyses were completed in the full sample of countries, we additionally performed logistic regressions to test the association between sexual orientation and having at least one 12-month mental disorder separately for each country.

Second aim

To assess possible mediation of the association between sexual orientation and psychiatric morbidity by social support, we employed a hierarchical regression approach [28]. First, we repeated a logistic regression analysis with sexual orientation as a predictor and mental disorder as an outcome in the subsample with information on all variables involved in the possible mediation (i.e. sexual orientation, mental disorder, and social support; Model 1). Second, we performed four ordinal logistic regressions with sexual orientation as a predictor and each of the four indicators of social support (contact frequency and general openness with family and friends) as an outcome (Model-set 2). Third, we performed a logistic regression analysis with sexual orientation and all four indicators of social support as predictors and mental disorder as an outcome (Model 3). All models were performed separately by gender. From these three (sets of) models, we calculated the indirect effect of each social support indicator and the total indirect effect by summing the four indirect effects. Estimates of the statistical significance of indirect effects were estimated in 10,000 bootstrap samples using Rao, Wu, and Yue’s bootstrap weighting method for complex surveys as implemented in SAS [41]. Due to concerns about model convergence problems in at least some of the bootstrap samples (which were smaller than the original sample) for uncommon disorders or disorder groups, we examined possible mediation only for any mental disorder and for > 1 mental disorder.

All analyses controlled for the country of origin of the participant. Because the data were clustered and weighted, standard errors were estimated using the design-based Taylor series method implemented in SAS [42]. Statistical significance for all analyses was evaluated at an adjusted α of 0.005, to account for the large number of tests employed in the analysis. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4.

Results

Sample descriptives

Of the initial 48,250 participants (female = 27,882, male = 20,368), 1361 were omitted from the sample, due to reporting their sexual orientation as “something else” (N = 180), because they were not sure about their sexual orientation or did not provide a response (N = 345), or because they indicated never having had intercourse (N = 836, see Supplemental Table 2).

The full sample demographics can be found in Table 1. Out of 46,889 participants (male = 42.4%, female = 57.6%), 0.8% reported being gay/bisexual (N = 357) and 1.0% reported being lesbian/bisexual (N = 450). More women identified as bisexual (women = 0.9%, men = 0.4%), while more men identified as exclusively same-sex attracted (women = 0.7%, men = 1.0%; see Supplemental Table 3). LGB participants were younger and were less frequently married (currently or in the past) compared to heterosexual participants. There were no differences in employment status among LGB and heterosexual participants; however, GB but not LB participants reported higher educational and income levels than heterosexual participants.

Sexual orientation and mental disorders by gender

Women

Compared to heterosexual women, LB women were significantly more likely to report at least one 12-month disorder (OR 2.2, p < 0.001), as well as more than one 12-month disorder (OR 3.3, p < 0.001). Among LB women, we found increased prevalence rates for all disorder groups (OR 2.2–4.9, p ≤ 0.001). LB women were also more likely to report each specific disorder (OR 2.2–9.4, p < 0.001), except for specific phobia (OR 1.7, p = 0.007) and ADD (OR 2.0, p = 0.116; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of 12-month mental disorders among participants with heterosexual or lesbian/gay and bisexual attraction in all countries

| Disorder | Female | Male | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | Lesbian/bisexual | OR (95% CI) | p value | Heterosexual | Gay/bisexual | OR (95% CI) | p value | |||||

| N | % (SE) | N | % (SE) | N | % (SE) | N | % (SE) | |||||

| Major depressive episode (non-hierarchical) | 2640 | 7.3 (0.2) | 87 | 15.9 (2) | 2.5* (1.9–3.4) | < 0.001 | 1091 | 4.2 (0.2) | 49 | 11.3 (1.9) | 2.8* (1.9–4.1) | < 0.001 |

| Dysthymia (non-hierarchical) | 707 | 1.9 (0.1) | 27 | 4.6 (1) | 2.5* (1.5–4.0) | < 0.001 | 282 | 1.2 (0.1) | 13 | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.3–4.7) | 0.008 |

| Bipolar disorder (broad) | 642 | 1.8 (0.1) | 33 | 6.7 (1.5) | 4.0* (2.4–6.6) | < 0.001 | 433 | 1.7 (0.1) | 23 | 4.9 (1.2) | 2.7* (1.6–4.5) | < 0.001 |

| Any mood disorder | 2973 | 8.2 (0.2) | 100 | 19.3 (2.3) | 2.8* (2.1–3.7) | < 0.001 | 1348 | 5.2 (0.2) | 60 | 14 (2.0) | 2.8* (2.0–3.9) | < 0.001 |

| Agoraphobia (with or without panic) | 483 | 1.2 (0.1) | 19 | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.1* (1.7–5.3) | < 0.001 | 171 | 0.7 (0.1) | 10 | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.7* (1.2–6.1) | 0.02 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1196 | 3.4 (0.1) | 42 | 7.4 (1.6) | 2.2* (1.4–3.4) | < 0.001 | 479 | 1.9 (0.1) | 19 | 3.8 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 0.027 |

| Panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) | 625 | 1.7 (0.1) | 30 | 5.6 (1.4) | 3.1* (1.8–5.4) | < 0.001 | 253 | 1.0 (0.1) | 15 | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.1* (1.7–5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1069 | 3.4 (0.1) | 55 | 11.2 (1.7) | 3.2* (2.3–4.5) | < 0.001 | 298 | 1.4 (0.1) | 16 | 4.6 (1.2) | 3.1* (1.7–5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Specific phobia | 2769 | 9.4 (0.2) | 63 | 14 (2.2) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.007 | 896 | 4.1 (0.2) | 33 | 9.7 (2.1) | 2.3* (1.4–3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Social phobia | 1521 | 4.4 (0.1) | 52 | 11.1 (2) | 2.6* (1.7–3.9) | < 0.001 | 802 | 3.1 (0.1) | 39 | 11.7 (2.1) | 3.7* (2.4–5.7) | < 0.001 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 5863 | 16.9 (0.3) | 166 | 29.7 (2.6) | 2.2* (1.7–2.8) | < 0.001 | 2498 | 9.7 (0.3) | 103 | 25.3 (2.6) | 3.0* (2.2–4.1) | < 0.001 |

| Any eating disorder | 268 | 1.4 (0.1) | 13 | 7.8 (2.5) | 4.9* (2.4–9.9) | < 0.001 | 88 | 0.6 (0.1) | 6 | 2.1 (1.0) | 3.2 (1.1–8.9) | 0.028 |

| Attention deficit disorder | 143 | 0.9 (0.1) | 6 | 4.7 (2) | 2.0 (0.8–4.7) | 0.116 | 124 | 1.2 (0.1) | 4 | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.2 (0.4–3.4) | 0.749 |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 337 | 1.8 (0.1) | 12 | 4.2 (1.1) | 2.3* (1.4–3.8) | < 0.001 | 322 | 2.6 (0.2) | 10 | 3.7 (1.2) | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) | 0.506 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder | 70 | 0.4 (0.1) | 2 | 5.4 (2.2) | 6.6* (2.5–17.3) | < 0.001 | 92 | 0.9 (0.1) | 2 | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.1–3.8) | 0.699 |

| Any disruptive behavior disorder | 445 | 2.9 (0.2) | 18 | 13.5 (3.2) | 2.3* (1.4–3.9) | 0.001 | 410 | 4.0 (0.3) | 11 | 5.6 (1.8) | 1 (0.5–1.9) | 0.927 |

| Alcohol abuse | 377 | 1.3 (0.1) | 19 | 3.9 (1.2) | 2.9* (1.6–5.3) | < 0.001 | 840 | 3.8 (0.2) | 18 | 4.3 (1.2) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.827 |

| Alcohol dependence | 198 | 0.6 (0.1) | 20 | 3.9 (1.0) | 6.1* (3.4–11.1) | < 0.001 | 419 | 1.8 (0.1) | 18 | 3.8 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.1–3.6) | 0.023 |

| Drug abuse | 128 | 0.4 (0.0) | 15 | 3.1 (0.9) | 6.9* (3.7–12.8) | < 0.001 | 282 | 1.3 (0.1) | 13 | 3.1 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.1–4.0) | 0.019 |

| Drug dependence | 85 | 0.3 (0.0) | 13 | 2.5 (0.8) | 9.4* (4.8–18.4) | < 0.001 | 161 | 0.8 (0.1) | 10 | 2.4 (0.9) | 3.0* (1.4–6.5) | 0.004 |

| Any substance use disorder | 525 | 1.7 (0.1) | 36 | 6.8 (1.4) | 3.7* (2.4–5.8) | < 0.001 | 1155 | 5.2 (0.2) | 36 | 8.7 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | 0.022 |

| Any disorder | 7001 | 20.4 (0.3) | 193 | 35.1 (2.7) | 2.2* (1.8–2.8) | < 0.001 | 3727 | 15.3 (0.4) | 140 | 34.2 (3.1) | 2.7* (2.0–3.6) | < 0.001 |

| > 1 disorder | 3056 | 8.3 (0.2) | 122 | 22.1 (2.1) | 3.3* (2.5–4.2) | < 0.001 | 1605 | 6.3 (0.2) | 71 | 16.6 (2.3) | 2.6* (1.9–3.7) | < 0.001 |

*< 0.005

Men

Compared to heterosexual men, GB men were more likely to report at least one 12-month disorder (OR 2.7, p < 0.001) or more than one 12-month disorder (OR 2.6, p < 0.001; see Table 2). Specifically, compared to heterosexual men, GB men were more likely to report mood disorders (OR 2.8, p < 0.001) and anxiety disorders (OR 3.0, p < 0.001), but they were not significantly more likely to have increased prevalence for any other disorder group (OR 1.0–3.2, p = 0.022–0.927; see Table 2). Among GB men, we also found increased prevalence rates for most specific mood and anxiety disorders (OR 2.3–3.7, p < 0.001), except for dysthymia, agoraphobia, and GAD (OR 1.8–2.7, p ≥ 0.008). We did not find elevated prevalence rates for any of the specific disruptive behavior disorders or substance use disorders (OR 0.07–21, p = 0.019–0.749), with the exception of drug dependence (OR 3.0, p = 0.004).

Prevalence of mental disorders by sexual orientation

Compared to heterosexual participants, both LG and bisexual participants were significantly more likely to report at least one 12-month disorder as well as more than one 12-month disorder (OR 2.1–2.5, p < 0.001; see Table 3). Specifically, both LG and bisexual participants were more likely to report mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders than heterosexual participants (OR 2.0–5.3, p ≤ 0.004). Bisexual, but not LG, participants additionally were more likely to report substance use disorders (OR 3.7, p < 0.001). There were no differences for 12-month disruptive behavior disorders. While bisexual participants, as compared to LG participants, showed somewhat elevated risks for reporting each of the disorder groups, as well as for reporting at least one or more than one disorder, these differences were not significant (OR 1.3–2.2, p = 0.009–0.535).

Table 3.

Prevalence of 12-month mental disorders among participants with heterosexual or lesbian/gay or bisexual attraction in all countries

| Disorder | Heterosexual | Lesbian/gay | Bisexual | LG (ref heterosexual) | Bisexual (ref heterosexual) | Bisexual (ref LG) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (SE) | N | % (SE) | N | % (SE) | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Any mood disorder | 4321 | 6.8 (0.2) | 79 | 15.4 (2.0) | 81 | 18.7 (2.5) | 2.4* | (1.8–3.3) | < 0.001 | 3.2* | (2.4–4.4) | < 0.001 | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) | 0.213 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 8361 | 13.4 (0.2) | 127 | 24.3 (2.2) | 142 | 32.3 (3.2) | 2.0* | (1.6–2.6) | < 0.001 | 3.3* | (2.4–4.4) | < 0.001 | 1.6 | (1.1–2.4) | 0.018 |

| Any eating disorder | 356 | 1.0 (0.1) | 8 | 4.4 (1.9) | 11 | 6.7 (2.3) | 3.7* | (1.5–9.0) | 0.004 | 5.3* | (2.5–11.1) | < 0.001 | 1.4 | (0.5–4.4) | 0.525 |

| Any disruptive behavior disorder | 855 | 3.5 (0.2) | 14 | 7.3 (1.7) | 15 | 11.8 (3.2) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.2) | 0.324 | 2 | (1.1–3.4) | 0.015 | 1.5 | (0.7–3.2) | 0.291 |

| Any substance use disorder | 1680 | 3.4 (0.1) | 34 | 6.8 (1.3) | 38 | 8.8 (1.7) | 1.7 | (1.1–2.5) | 0.023 | 3.7* | (2.4–5.6) | < 0.001 | 2.2 | (1.2–4.1) | 0.009 |

| Any disorder | 10,728 | 18.0 (0.3) | 172 | 33.0 (2.5) | 161 | 36.9 (3.3) | 2.1* | (1.7–2.7) | < 0.001 | 2.9* | (2.2–3.9) | < 0.001 | 1.4 | (1.0–2.0) | 0.08 |

| > 1 disorder | 4661 | 7.3 (0.2) | 94 | 18.4 (2.1) | 99 | 21.2 (2.6) | 2.5* | (1.9–3.4) | < 0.001 | 3.7* | (2.8–5.0) | < 0.001 | 1.5 | (1.0–2.2) | 0.077 |

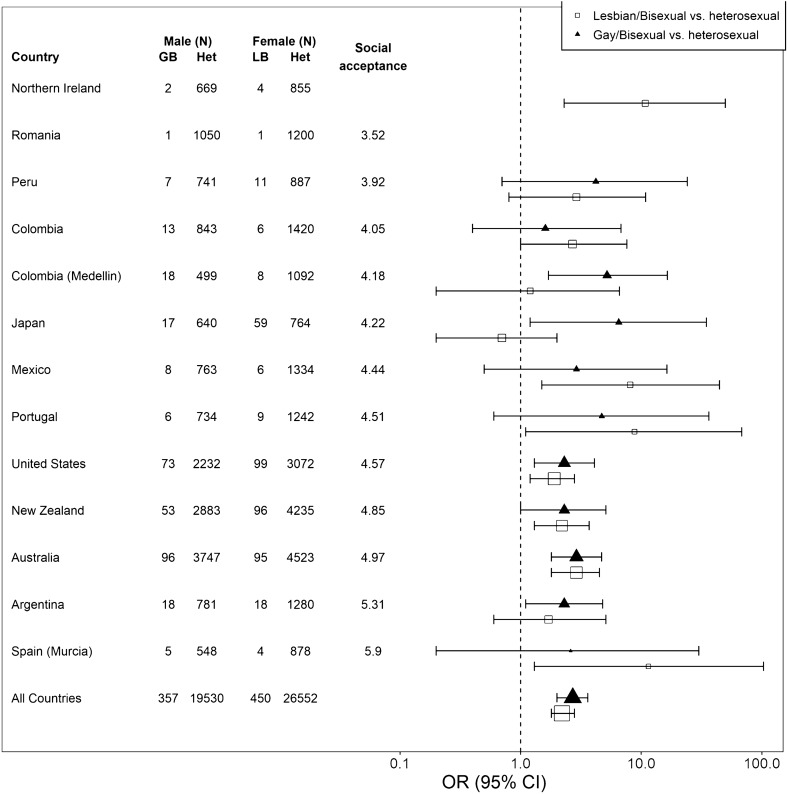

Country-level social acceptance and mental health

Figure 1 shows the risk for reporting at least one 12-month disorder among GB or LB participants as compared to heterosexual participants by country. Countries are ranked by their increasing country-level social acceptance scores, illustrating that the relative risk for LB and GB participants to report at least one 12-month disorder did not appear to be associated with country-level LGB social acceptance.

Fig. 1.

Association between likelidhood of reporting at least one 12-month disorder and country-level social acceptance, by sexual orientation. The social acceptance score for Northern Ireland was omitted, because the index only included an estimate for Great Britain as a whole and Northern Ireland was not included in this estimate. There were zero cases with a 12-month mental disorder among the (very small) sample for GB participants in Northern Ireland and both GB and LB participants in Romania

Mediation by social support

The full results of the mediation analysis in women and men are provided in Supplemental Tables 4–7. The results for Model 1 (sexual orientation predicting mental disorder) were very similar to those discussed before and hence are not discussed here.

Women

With regard to Model-set 2 (the association between sexual orientation and social support), we found that LB women were significantly less likely to report high levels of contact frequency (OR 0.6, p = 0.004) and high general openness with their family (OR 0.5, p < 0.001) than heterosexual women (see Table 4). However, there were no differences between LB and heterosexual women in frequency of contact and general openness with friends (OR 1.1, p = 0.720, and OR 0.8, p = 0.120, respectively).

Table 4.

Differences in the distribution of scores on openness and contact frequency with family and friends by sexual orientation, separately by gender

| Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Friends | Family | Friends | |||||

| Heterosexual | GB | Heterosexual | GB | Heterosexual | LB | Heterosexual | LB | |

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | |

| Openness (N) | 9302 | 166 | 9298 | 166 | 13,258 | 204 | 13,218 | 206 |

| Not at all | 16.71 (0.55) | 21.33 (4.59) | 19.68 (0.6) | 11.82 (3.23) | 13.92 (0.49) | 22.31 (4.08) | 20 (0.54) | 11.51 (3.03) |

| A little | 17.98 (0.52) | 17.82 (3.09) | 19.98 (0.6) | 11.45 (3.04) | 13.56 (0.43) | 17.84 (4.17) | 16.21 (0.45) | 28.71 (4.95) |

| Some | 26.46 (0.57) | 16.25 (3.64) | 29.27 (0.64) | 27.01 (4.3) | 24.51 (0.61) | 25.81 (3.2) | 25.69 (0.52) | 26.90 (3.87) |

| A lot | 38.86 (0.74) | 44.60 (4.96) | 31.08 (0.73) | 49.71 (5.56) | 48.01 (0.67) | 34.04 (4.1) | 38.10 (0.7) | 32.88 (4.27) |

| OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.6–1.4, p value = 0.771 | OR 2.0*, 95% CI 1.3–3.1, p value ≤ 0.001 | OR 0.5*, 95% CI 0.4–0.7, p value ≤ 0.001 | OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.6–1.1, p value = 0.120 | |||||

| Contact frequency (N) | 9307 | 167 | 9312 | 167 | 13,245 | 206 | 13,197 | 206 |

| Most every day | 19.47 (0.58) | 20.57 (4.03) | 21.14 (0.54) | 28.36 (4.68) | 30.05 (0.72) | 19.67 (2.86) | 20.02 (0.51) | 19.38 (4.13) |

| Few times a week | 29.73 (0.64) | 33.23 (5.35) | 31.12 (0.68) | 34.48 (5.35) | 29.29 (0.62) | 20.77 (3.7) | 27.80 (0.56) | 30.51 (4.11) |

| Few times a month | 20.26 (0.53) | 17.26 (3.65) | 19.43 (0.58) | 13.70 (3.04) | 16.67 (0.45) | 25.07 (4.17) | 19.80 (0.49) | 23.40 (3.69) |

| Once a month | 10.54 (0.42) | 11.43 (2.99) | 9.98 (0.39) | 9.98 (2.42) | 8.83 (0.34) | 11.73 (2.7) | 9.30 (0.33) | 12.03 (2.91) |

| Less than once a month | 20 (0.57) | 17.51 (3.86) | 18.32 (0.58) | 13.48 (3.13) | 15.16 (0.47) | 22.76 (4.12) | 23.08 (0.58) | 14.68 (2.61) |

| OR 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.8, p value = 0.248 | OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.0–2.2, p value = 0.026 | OR 0.6*, 95% CI 0.5–0.9 p value = 0.004 | OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8–1.4, p value = 0.720 | |||||

In Model 3, including sexual orientation and the social support indicators as predictors, lower openness with family was significantly associated with having at least one (OR 0.8, p < 0.001) or more than one 12-month disorder (OR 0.8, p < 0.001). Additionally, a lower frequency of contact with friends was significantly associated with having more than one 12-month disorder (OR 0.9, p < 0.001). For at least one 12-month mental disorder, there was a significant indirect effect of openness with family (ab estimate 0.129, 99.5% bootstrap percentile interval 0.036–0.250) and a significant total indirect effect of all social support indicators (total ab estimate 0.141, 99.5% bootstrap percentile interval 0.036–0.266, proportion mediated 19.0%). Results were similar for more than one 12-month disorder: there was a significant indirect effect of openness with family (ab estimate 0.172, 99.5% bootstrap percentile interval 0.047–0.330) and a significant total indirect effect of all social support indicators (total ab estimate 0.205, 99.5% bootstrap percentile interval 0.053–0.368, proportion mediated 16.9%).

Men

In model 2, GB men reported significantly higher general openness with friends than heterosexual men (OR 2.0, p < 0.001; see Table 4). However, there were no significant differences between GB men and heterosexual men in general openness with family (OR 0.9, p = 0.771), or frequency of contact with either family or friends (OR 1.2, p = 0.248, and OR 1.5, p = 0.026, respectively). In Model 3, including sexual orientation and the social support indicators as predictors, lower openness with family was significantly associated with having at least one (OR 0.8, p < 0.001) or more than one 12-month disorder (OR 0.8, p < 0.001). Additionally, lower frequency of contact with family (OR 0.9, p = 0.002) and higher frequency of contact with friends (OR 1.1, p = 0.003) were also significantly associated with having at least one mental disorder. However, there were no significant indirect effects, indicating no evidence for mediation.

Discussion

The findings from this large general population-based study provide cross-national evidence for the disparities in psychiatric morbidity between LGB and heterosexual individuals. Our results are consistent with those reported in national population-based studies [4, 5, 7, 11] and cross-national meta-analyses [20]. We extended these findings by illustrating that this increased risk is a cross-national issue that is present across a range of disorders (particularly for LB women), and further provided additional evidence partially supporting the psychological mediation framework [27].

Cross-national disparities in psychiatric morbidity

In line with our first aim, our findings add to previous studies documenting the higher likelihood for both LGB women and men to report mood and anxiety disorders compared to heterosexual participants [5, 7, 10]. Furthermore, we found that LB women but not GB men were more likely to report a 12-month substance use disorder compared to heterosexual participants, consistent with previous national studies [2, 3]. The exception to this finding was drug dependence, which was more likely among both sexual minority women and men compared to heterosexual participants. We also found that LB women, but not GB men, showed clearly increased risks for disruptive behavior disorders. Overall, we found a heightened risk for LGB individuals of any gender to report at least one disorder in the past year [5]. In contrast to previous, smaller national studies that found either no difference [5] or elevated risks for comorbidity only among GB men [4]; we found that both GB men and LB women were more likely to report more than one 12-month disorder compared to heterosexual participants. Contrasting previous studies [9], we did not find significant differences in the risk for psychiatric morbidity between LG and bisexual participants, despite the fact that bisexual participants showed elevated rates of psychiatric morbidity compared to LG participants. One possible explanation for this might have been the small size of sexual orientation sub-groups.

While only exploratory and limited by the relatively small number of surveys included, our exploratory analysis suggests no clear relationship between country-level social acceptance and risk for psychiatric morbidity. Instead, an individual’s sexual minority status appears to be a stable risk factor for psychiatric morbidity across countries. This finding is counter to both our expectations and to the literature suggesting a relationship between state-level LGB climate and improved mental health [19, 28]. However, increasing social acceptance of sexual minorities might result in LGB-specific discrimination becoming more subtle rather than disappearing, as Sandfort and colleagues have suggested [5]. To address this, future cross-national research on the relationship between sexual minority stress and psychiatric morbidity should assess both country-level acceptance as well as person-level experiences of discrimination.

Influence of social support quality

Regarding our second aim, the exploratory mediation analysis found that, among LB women, lower levels of social support partially accounted for the relationship between sexual minority status and the heightened risk for reporting at least one or more than one 12-month disorder. This effect was primarily related to lower openness with family, and we found no evidence for a similar effect among men. These findings are partially consistent with the idea that sexual orientation-based stigmatization may lead to lower social support quality, making sexual minority individuals less resilient to life stressors [27, 28, 32, 34, 43]. Importantly, differences in the mediating role of social processes among LGB participants are in line with some studies that have shown stronger mediating effects among sexual minority women compared to men [44] but are inconsistent with those finding a mediating effect of social support only among sexual minority men [28]. It is noteworthy that, we found only small and inconsistent differences in the quality of social support between heterosexual and LGB individuals, contrasting previous research [11, 29, 34]. Future research should investigate potential differential mechanisms between sexual minority women and men in the mediating role of social support.

Strengths and limitations

The current study has multiple strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first cross-national study assessing mental health disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals, highlighting that the adverse effect of minority stress experienced by LGB individuals is a global issue. In addition, using the CIDI, a validated and reliable interview, we were able to assess a wide spectrum of disorders. Moreover, participants for our study were sampled from the general population, thus preventing the biased estimates that can arise from sampling from organizations and groups within the LGB community [45].

This study also has several limitations. First, responses were collected between 2001 and 2012, meaning that recent social and legal changes (e.g. marriage equality) are not reflected in the data. However, differences in prevalence rates of mental disorders between LGB and heterosexual participants reported in our study were similar to that of more recent studies [6, 10]. Indeed, Sandfort and colleagues [5] have suggested that increasing social acceptance of sexual minorities might result in LGB-specific discrimination becoming more subtle rather than disappearing, which may explain the persistence of disparities in psychiatric morbidity between LGB and heterosexual individuals despite societal change.

Furthermore, the overall small size of the LGB sample suggests underreporting of sexual minority participants, particularly in low/middle-income countries, where only about 0.5% of the population identified as LGB. This might be related to several methodological characteristics. First, participants might have been less likely to disclose potentially socially undesirable information (e.g. sexual minority status) in an interview compared to computer-assisted administration [46]. Second, in most countries, only participants who reported having had sexual intercourse (or having biological children) were asked about their sexual orientation; sexual minority participants may be less likely to have had sexual intercourse or may not regard same-sex sexual activity as being sexual intercourse. Taken together, this means that self-identified LGB participants may not be fully representative of all LGB people, especially in low/middle-income countries. Notably, it is possible that participants who did not disclose their sexual minority status might systematically differ in their risk of reporting psychiatric morbidity than those who did, leading to a potential underestimation of global mental health disparities. In addition, it is possible that those participants who were able to open up about their sexual minority status also experienced higher levels of general social support. Especially among GB men, this might have obscured a potential mediating effect of social support on mental health outcomes.

We also grouped bisexual and lesbian/gay individuals together for the mediation analyses. This is an issue, as studies have shown that aggregating sexual minority groups can obscure differences in particular sub-groups [47]. Finally, the mediation analysis was based on cross-sectional data, so we have no information about the temporal ordering of events. Although it is reasonable to presume that sexual orientation preceded current social support and 12-month mental health problems, we cannot exclude the possibility that mental disorders actually caused a decrease in social support (among LB women), rather than social support mediating the effect of sexual orientation on mental disorders [44].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides further evidence for an association between sexual minority status and a wide range of psychiatric disorders from a large cross-national sample. Our results are in line with findings from national studies and stress the increased risk for psychiatric disorders among LGB individuals. We found that the increased risk for a psychiatric disorder in the past year for LGB individuals was partially mediated by perceived openness with family among women, but not men. To fully understand the relationship between minority stress and psychiatric morbidity in sexual minority individuals, future studies should consider gender differences in the influence of social support.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative is supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the United States Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the World Health Organization, other sponsoring organizations, agencies, or governments. The Argentina survey—Estudio Argentino de Epidemiología en Salud Mental (EASM)—was supported by a grant from the Argentinian Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud de la Nación)—(Grant Number 2002-17270/13-5). The 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The Mental Health Study Medellín—Colombia was carried out and supported jointly by the Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health (CES University) and the Secretary of Health of Medellín. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013, H25-SEISHIN-IPPAN-006) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. The Northern Ireland Study of Mental Health was funded by the Health & Social Care Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency. The Peruvian World Mental Health Study was funded by the National Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Peru. The Portuguese Mental Health Study was carried out by the Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, NOVA University of Lisbon, with collaboration of the Portuguese Catholic University, and was funded by Champalimaud Foundation, Gulbenkian Foundation, Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and Ministry of Health. The Romania WMH study projects "Policies in Mental Health Area" and "National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use" were carried out by National School of Public Health & Health Services Management (former National Institute for Research & Development in Health), with technical support of Metro Media Transilvania, the National Institute of Statistics-National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC, Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands and were funded by Ministry of Public Health (former Ministry of Health) with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL. The Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain—Murcia (PEGASUS-Murcia) Project has been financed by the Regional Health Authorities of Murcia (Servicio Murciano de Salud and Consejería de Sanidad y Política Social) and Fundación para la Formación e Investigación Sanitarias (FFIS) of Murcia. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. A complete list of all within-country and cross-national WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh.

The WHO World Mental Health Survey collaborators are Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, MD, PhD; Ali Al-Hamzawi, MD; Jordi Alonso, MD, PhD; Laura Helena Andrade, MD, PhD; Lukoye Atwoli, MD, PhD; Corina Benjet, PhD; Guilherme Borges, ScD; Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD; Ronny Bruffaerts, PhD; Brendan Bunting, PhD; Jose Miguel Caldas-de-Almeida, MD, PhD; Graça Cardoso, MD, PhD; Somnath Chatterji, MD; Alfredo H. Cia, MD; Louisa Degenhardt, PhD; Koen Demyttenaere, MD, PhD; Silvia Florescu, MD, PhD; Giovanni de Girolamo, MD; Oye Gureje, MD, DSc, FRCPsych; Josep Maria Haro, MD, PhD; Meredith Harris, PhD; Hristo Hinkov, MD, PhD; Chi-yi Hu, MD, PhD; Peter de Jonge, PhD; Aimee Nasser Karam, PhD; Elie G. Karam, MD; Norito Kawakami, MD, DMSc; Ronald C. Kessler, PhD; Andrzej Kiejna, MD, PhD; Viviane Kovess-Masfety, MD, PhD; Sing Lee, MB, BS; Jean-Pierre Lepine, MD; John McGrath, MD, PhD; Maria Elena Medina-Mora, PhD; Zeina Mneimneh, PhD; Jacek Moskalewicz, PhD; Fernando Navarro-Mateu, MD, PhD; Marina Piazza, MPH, ScD; Jose Posada-Villa, MD; Kate M. Scott, PhD; Tim Slade, PhD; Juan Carlos Stagnaro, MD, PhD; Dan J. Stein, FRCPC, PhD; Margreet ten Have, PhD; Yolanda Torres, MPH, Dra.HC; Maria Carmen Viana, MD, PhD; Daniel V. Vigo, MD, DrPH; Harvey Whiteford, MBBS, PhD; David R. Williams, MPH, PhD; Bogdan Wojtyniak, ScD.

Author contributions

Concept and design: PJ, RCK, YAV, LB, JHG. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: JHG, PJ. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: JHG, YAV. Obtained funding: JA, GB, BB, GC, PJ, SF, OG, ELK, NK, RCK, FN-M, JP-V, JCS, YT. Supervision: PJ, RCK.

Availability of data and materials

Access to the cross-national World Mental Health (WMH) data is governed by the organizations funding and responsible for survey data collection in each country. These organizations made data available to the WMH consortium through restricted data sharing agreements that do not allow us to release the data to third parties. The exception is that the U.S. data are available for secondary analysis via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/00527.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

In the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler was a consultant for Datastat, Inc., Holmusk, RallyPoint Networks, Inc., and Sage Therapeutics. He has stock options in Mirah, PYM, and Roga Sciences. Dr. Navarro-Mateu reports non-financial support from Otsuka outside the submitted work. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Footnotes

The members of WHO World Mental Health Survey collaborators are listed in acknowledgements.

Contributor Information

Jan-Ole H. Gmelin, Email: j.h.gmelin@rug.nl

Ymkje Anna De Vries, Email: y.a.de.vries@rug.nl.

Laura Baams, Email: l.baams@rug.nl.

Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Email: aguilargaxiola@UCDAVIS.EDU.

Jordi Alonso, Email: Jalonso@IMIM.ES.

Guilherme Borges, Email: guilhermelgborges@gmail.com.

Brendan Bunting, Email: bp.bunting@ulster.ac.uk.

Graca Cardoso, Email: gracacardoso@gmail.com.

Silvia Florescu, Email: florescu.silvia@gmail.com.

Oye Gureje, Email: oye_gureje@yahoo.com.

Elie G. Karam, Email: egkaram@idraac.org

Norito Kawakami, Email: norito@m.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Sing Lee, Email: singlee@cuhk.edu.hk.

Zeina Mneimneh, Email: zeinam@umich.edu.

Fernando Navarro-Mateu, Email: fernando.navarro@carm.es.

José Posada-Villa, Email: jposada@unicolmayor.edu.co.

Charlene Rapsey, Email: charlene.rapsey@otago.ac.nz.

Tim Slade, Email: timothy.slade@sydney.edu.au.

Juan Carlos Stagnaro, Email: jcstagnaro@gmail.com.

Yolanda Torres, Email: ytorres@CES.EDU.CO.

Ronald C. Kessler, Email: Kessler@hcp.med.harvard.edu

Peter de Jonge, Email: peter.de.jonge@rug.nl.

The WHO World Mental Health Survey collaborators:

Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Ali Al-Hamzawi, Jordi Alonso, Laura Helena Andrade, Lukoye Atwoli, Corina Benjet, Guilherme Borges, Evelyn J. Bromet, Ronny Bruffaerts, Brendan Bunting, Jose Miguel Caldas-de-Almeida, Graça Cardoso, Somnath Chatterji, Alfredo H. Cia, Louisa Degenhardt, Koen Demyttenaere, Silvia Florescu, Giovanni de Girolamo, Oye Gureje, Josep Maria Haro, Meredith Harris, Hristo Hinkov, Chi-yi Hu, Peter de Jonge, Aimee Nasser Karam, Elie G. Karam, Norito Kawakami, Ronald C. Kessler, Andrzej Kiejna, Viviane Kovess-Masfety, Sing Lee, Jean-Pierre Lepine, John McGrath, Maria Elena Medina-Mora, Zeina Mneimneh, Jacek Moskalewicz, Fernando Navarro-Mateu, Marina Piazza, Jose Posada-Villa, Kate M. Scott, Tim Slade, Juan Carlos Stagnaro, Dan J. Stein, Margreet ten Have, Yolanda Torres, Maria Carmen Viana, Daniel V. Vigo, Harvey Whiteford, David R. Williams, and Bogdan Wojtyniak

References

- 1.Kidd SA, Howison M, Pilling M, et al. Severe mental illness in LGBT Populations: a scoping review. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:779–783. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plöderl M, Tremblay P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry Abingdon Engl. 2015;27:367–385. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandfort TGM, de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Schnabel P. Same-sex sexual behavior and psychiatric disorders: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:85–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandfort TGM, de Graaf R, ten Have M, et al. Same-sex sexuality and psychiatric disorders in the second Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS-2) LGBT Health. 2014;1:292–301. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semlyen J, King M, Varney J, Hagger-Johnson G. Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low wellbeing: combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty A, McManus S, Brugha TS, et al. Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198:143–148. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan RCH, Operario D, Mak WWS. Bisexual individuals are at greater risk of poor mental health than lesbians and gay men: the mediating role of sexual identity stress at multiple levels. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns RA, Butterworth P, Jorm AF. The long-term mental health risk associated with non-heterosexual orientation. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27:74–83. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eres R, Postolovski N, Thielking M, Lim MH. Loneliness, mental health, and social health indicators in LGBTQIA+ Australians. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1037/ort0000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hickson F, et al. Hidden from health: structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and HIV across 38 countries in the European MSM Internet Survey. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29:1239–1246. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Star A, Branstrom R. Acceptance of sexual minorities, discrimination, social capital and health and well-being: a cross-European study among members of same-sex and opposite-sex couples. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:812. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pachankis JE, Bränström R. Hidden from happiness: structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:403–415. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miedema SS, Haardorfer R, Keyes CLM, Yount KM. Does socio-structural context matter? A multilevel test of sexual minority stigma and depressive symptoms in four Asia-Pacific countries. J Health Soc Behav. 2019;60:416–433. doi: 10.1177/0022146519877003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gato J, Barrientos J, Tasker F, et al. Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health among LGBTQ plus young adults: a cross-cultural comparison across six nations. J Homosex. 2021;68:612–630. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA. The protective effects of social/contextual factors on psychiatric morbidity in LGB populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1071–1080. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis NM. Mental health in sexual minorities: recent indicators, trends, and their relationships to place in North America and Europe. Health Place. 2009;15:1029–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittgens C, Fischer MM, Buspavanich P, et al. Mental health in people with minority sexual orientations: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145:357–372. doi: 10.1111/acps.13405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer IH, Frost DM. Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities; pp. 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis JR, Glunt EK. Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. J Gay Lesbian Med Assn. 1998;2:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Xuan Z. Social networks and risk for depressive symptoms in a national sample of sexual minority youth. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger EA, Upchurch DM. Sexual orientation, social support, and mental health resilience in a US National sample of adults. Behav Med. 2020 doi: 10.1080/08964289.2020.1825922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattler FA, Wagner U, Christiansen H. Effects of minority stress, group-level coping, and social support on mental health of German gay men. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snapp SD, Watson RJ, Russell ST, et al. Social support networks for LGBT young adults: low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Fam Relat Interdiscip J Appl Fam Stud. 2015;64:420–430. doi: 10.1111/fare.12124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams SL, Mann AK, Fredrick EG. Proximal minority stress, psychosocial resources, and health in sexual minorities. J Soc Issues. 2017;73:529–544. doi: 10.1111/josi.12230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Button DM, O’Connell D, Gealt R. Sexual minority youth victimization and social support: the intersection of sexuality, gender, race, and victimization. J Homosex. 2012;59:18–43. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.614903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehlke SJ, Braitman AL, Dawson CA, et al. Sexual minority stress and social support explain the association between sexual identity with physical and mental health problems among young lesbian and bisexual women. Sex Roles J Res. 2020;83:370–381. doi: 10.1007/s11199-019-01117-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC, Haro JM, Heeringa SG, et al. The world health organization world mental health survey initiative. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15:161–166. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00004395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heeringa S, Wells J, Hubbard F, et al. Sample designs and sampling procedures. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, et al., editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.The World Bank (2009) Data and Statistics. http://go.worldbank.org/D7SN0B8YU0

- 39.Pennell BE, Mneimneh ZN, Bowers AG et al (2008) Implementation of the World Mental Health Surveys. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB (eds) The WHO world mental health surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 33–57

- 40.Flores AR, Park A (2018) Polarized progress. Social acceptance of LGBT people in 141 countries, 1981 to 2014

- 41.Rao JNK, Wu CFJ, Yue K. Some recent work on resampling methods for complex surveys. Surv Methodol. 1992;18:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolter K. Introduction to variance estimation. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Star A, Pachankis JE, Bränström R. Sexual orientation openness and depression symptoms: a population-based study. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2019;6:369–381. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Argyriou A, Goldsmith KA, Rimes KA. Mediators of the disparities in depression between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals: a systematic review. Arch Sex Behav. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01862-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuyper L, Fernee H, Keuzenkamp S. A comparative analysis of a community and general sample of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:683–693. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vereecken CA, Maes L. Comparison of a computer-administered and paper-and-pencil-administered questionnaire on health and lifestyle behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matthews DD, Blosnich JR, Farmer GW, Adams BJ. Operational definitions of sexual orientation and estimates of adolescent health risk behaviors. LGBT Health. 2014;1:42–49. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Access to the cross-national World Mental Health (WMH) data is governed by the organizations funding and responsible for survey data collection in each country. These organizations made data available to the WMH consortium through restricted data sharing agreements that do not allow us to release the data to third parties. The exception is that the U.S. data are available for secondary analysis via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/00527.