Abstract

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy has become a promising structural biology tool to resolve complex and dynamic biological mechanisms in-vitro and in-cell. Here, we focus on the advantages of continuous wave (CW) and pulsed EPR distance measurements to resolve transcription processes and protein-DNA interaction. The wide range of spin-labeling approaches that can be used to follow structural changes in both protein and DNA render EPR a powerful method to study protein-DNA interactions and structure–function relationships in other macromolecular complexes. EPR-derived data goes well beyond static structural information and thus serves as the method of choice if dynamic insight is needed. Herein, we describe the conceptual details of the theory and the methodology and illustrate the use of EPR to study the protein-DNA interaction of the copper-sensitive transcription factor, CueR.

Keywords: EPR spectroscopy, CW-EPR, DEER, Protein-DNA interaction, CueR

Metalloregulator proteins

Metalloregulator proteins regulate the metal concentration in bacterial cells by controlling the transcription rate of metal-responsive genes (Tottey et al. 2005; Wladron et al. 2009; Robinson and Winge 2010). On the one hand, metal ions are essential in small concentrations for the survival of the cell. For example, they serve as cofactors for oxidation–reduction reactions and as structural centers to stabilize proteins. However, an excess of metal ions can lead to cytotoxicity and cell death by the catalysis of reactive oxygen species (Weekley and He 2017; Fleming and Burrows 2020; Hofmann et al. 2021). To maintain proper cytoplasmic metal ion concentrations, also known as metal homeostasis, nature exploits a range of metal binding proteins, with one example being metal ion transcription factors. These proteins have extremely high-affinity metal coordination sites with sensitivity to free metal ions in the range of 10−15–10−21 M, which corresponds to sensitivity to nearly one ion per cell. Upon coordination of the metal ion, downstream remediation processes, most principally the activation or repression of gene transcription, occur to express proteins that minimize metal ion toxicity. The function of these metal transcription factors is dependent on the ability of metal ions to drive changes in the structure and/or dynamics of both protein and DNA to ultimately regulate metal homeostasis within the organism (Tottey et al. 2005).

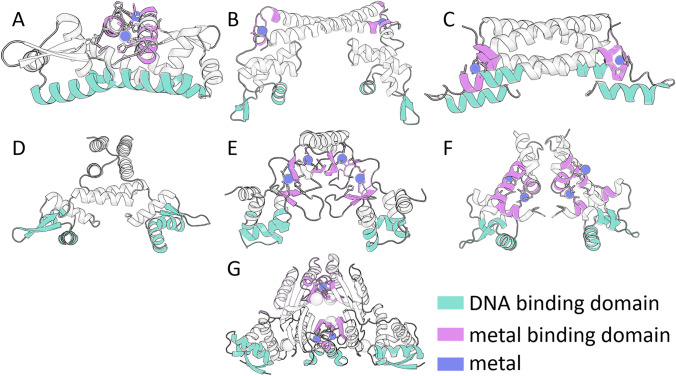

As of today, seven major families of metalloregulators have been reported in bacteria: ArsR, MerR, CsoR, CopY, Fur, Dtx1, and NikR. These regulate six biologically essential transition metals, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn, in addition to the heavy metal ions, Ag, Au, Cd, and Hg (Outten and O'Halloran 2001; Cavet et al. 2002; Changla et al. 2003; Giedroc and Arunkumar 2007). Figure 1 shows the crystal structures of proteins in each of the families. Most of the metal-sensitive transcription factors adopt the secondary structure of a winged helix domain to bind DNA. Others employ an α-helical bundle or a ribbon-helix-helix structure to interact with DNA.

Fig. 1.

Structures of transcription factors and metal binding domains. One representative structure from each metalloregulator family is depicted in cartoon representation. (A) ArsR: CzrA (PDB-ID: 1r1v), (B) MerR: CueR (PDB-ID: 1q07), (C) CsoR: CsoR (PDB-ID: 2hh7), (D) CopY: CopY (model), (E) Fur: Fur (PDB-ID: 4rb1), (F) Dtx1: DtxR (PDB-ID: 1f5t), (G) NikR: NikR (PDB-ID: 2HZV). Cartoon D does not have highlighted metal binding sites because there is no holo-structure available. Nevertheless, metal binding sites in the form of cysteine residues are predicted to be found on the C-terminal end. DNA binding domains are colored in cyan, metal binding domains are colored in pink, and metals are represented as spheres in violet. The protein structures were constructed and colored using Pymol (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.3.3 Schrödinger, LLC)

These protein families differ not only in structure but also in the mode by which the metal regulation is controlled. The ArsR, CsoR, and CopY family of metalloregulators repress transcription by coordinating with the promoter. Upon coordination of the specific metal ion, they dissociate from the promoter region and allow transcription to occur. The proteins in the Fur, DtxR, and NikR family turn off the expression of uptake systems in response to metal excess by using the metal ion as a co-repressor. The proteins of the MerR family activate transcription by allosterically changing the structure of the DNA promoter upon metal coordination (Giedroc and Arunkumar 2007; Philips et al. 2015).

Therefore, it is apparent that the coordination of the metal ions drives conformational changes in proteins to impact regulation. Understanding the mechanisms of action of these metal-sensitive transcription factors is essential to the understanding of how bacteria maintain such complex metal homeostasis, as well as to the development of novel antibiotics that can selectively cause metal dyshomeostasis in bacteria.

Over the last few years, we have successfully studied the transcription mechanism of E. coli CueR, a copper transcription factor of the MerR family, primarily using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Herein, we will describe the EPR methodology and benefits of EPR over other biophysical techniques. We will then demonstrate how EPR resolved details of the CueR transcription mechanism both in conformations and dynamics.

EPR methodology

The measurement of the structure of a protein-DNA complex is highly challenging. The Protein Data Bank contains only a few thousand structures of proteins complexed with DNA for both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. Most of these structures were measured by X-ray diffraction or solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The lack of structural information is a major bottleneck, given that in prokaryotic systems alone, there exist about 18,000 transcription factors.

These limitations that prevent the advancement of structural studies in such systems can be overcome by EPR spectroscopy. This technique has become a promising tool to study conformational and dynamical changes in transcription factors (Ruthstein et al. 2013; Sameach et al. 2017; Tangprasertchai et al. 2017; Warren et al. 2018; Schmidt et al. 2018; Sameach et al. 2019). EPR can report on solution state structure and dynamics of biomolecules without the need for isotopic labeling as required by NMR spectroscopy. In addition, the use of EPR spectroscopy does not require crystallization and is not limited to the size of biomolecules, unlike NMR spectroscopy. However, EPR spectroscopy requires the presence of an unpaired electron spin, and thus, most biological samples require site-directed spin labeling at the site of interest (Meron et al. 2022).

Site-directed spin labeling

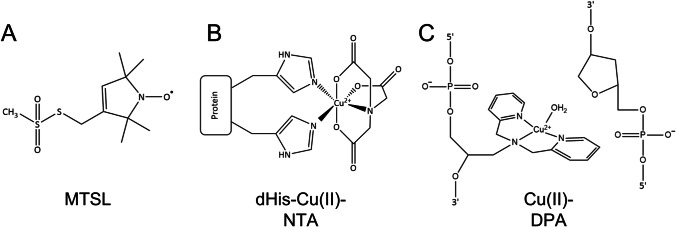

Site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) is a powerful technique to introduce a moiety containing an unpaired electron spin into biological systems which are typically diamagnetic. In this method, a specific site on the biomolecule is targeted to incorporate an unpaired electron, thus creating a spin label. The most commonly used spin labels are based on the nitroxide radical, which has an electron spin of ½ and a nuclear spin of the 14 N atom of 1. The most used spin label, known as methanothiosulfonate (MTSL), is chemically attached to thiol groups of cysteine residues (Fig. 2A) (Hubbell et al. 1998; Columbus 2002). This method usually requires mutants which omit all native cysteine residues and the introduction of one or several cysteine residues by point mutations. Cysteine has also been used as a method to attach a linker that contains paramagnetic metal ions such as Cu(II), Mn(II), and Gd(III) (Cunningham et al. 2015a; Giannoulis et al. 2020; Giannoulis et al. 2021). This metal-labeling strategy has been found to be most impactful for in-cell measurements using Gd(III) labels (Qi et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2017; Dalaloyan et al. 2019).

Fig. 2.

Site-directed spin-labeling approaches used in this research. (A) MTSL labeling for proteins, (B) dHis-Cu(II)-NTA labeling for proteins, (C) Cu(II)-DPA labeling for DNA

In order to provide an orthogonal handle for protein labeling, Saxena and co-workers have developed a methodology for spin labeling with Cu(II) to native side chains on a protein (Fig. 2B). In this approach, the Cu(II) ion is coordinated to the protein by a strategically placed double histidine (dHis) mutation. The dHis mutations are created at solvent-exposed sites at positions i and i + 4 for α-helices and i and i + 2 for β-sheets (Arnold and Haymore 1991; Todd et al. 1991; Higaki et al. 1992; Jung et al. 1995; Voss et al. 1995; Nicoll et al. 2006; Cunningham et al. 2015b). These placements generate known Cu(II) binding sites. The nonspecific binding of Cu(II) elsewhere in the protein is prevented by the introduction of the Cu(II) ion as a complex with iminodiacetic acid (IDA) (Cunningham et al. 2015b; Lawless et al. 2017a) or nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) (Cunningham et al. 2015b; Ghosh et al. 2018). Labeling a dHis-mutated protein with the Cu(II) complex is remarkably easy, only requiring the solution to be incubated at ca 4 °C for 30 min (Gamble Jarvi et al. 2020a). Since stoichiometric amounts of the label are used, there is typically no need for post-labeling purification. The method can be implemented in a wide variety of buffers (Gamble Jarvi et al. 2020a) over a range of pH values and appears to be resistant to the presence of other metal ions (Wort et al. 2021a, b). In addition, dHis labeling does not require the use of thiols for labeling, and therefore, there is no need for a Cys-null protein mutant. Other benefits of the dHis-Cu(II) motif can be illustrated by EPR distance measurements, which will be described in the following section. Since the Cu(II) position is significantly restricted by bidentate coordination to the protein side chain, the resultant distances are remarkably precise, with a distance distribution width that is five times narrower than that of a nitroxide spin label (Cunningham et al. 2015b; Gamble Jarvi et al. 2021).

The Saxena group has also recently developed a methodology for using Cu(II) ions to label DNA (Lawless et al. 2017b; Ghosh et al. 2020a). In this method, a 2,2’-dipicolylamine (DPA) phosphoramidite is easily incorporated into any DNA nucleotide during initial DNA synthesis, and a Cu(II) ion chelates to the DPA (Fig. 2C). The opposing strand of DNA uses a commercially available abasic sugar-phosphate site called dSpacer. The label is positioned within the DNA duplex for a direct and accurate report on backbone helical distance without the need for any additional modeling. It is often beneficial to compare experimental distance distributions to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to understand the atomistic details of the experimentally derived conformations. Therefore, force field parameters for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been developed for both the dHis-Cu(II) spin label and the Cu(II) DNA label, and it has been shown that distance distributions generated from MD agree well with those from the experiment (Lawless 2017c; Bogetti et al. 2020; Ghosh et al. 2020b).

EPR distance measurements

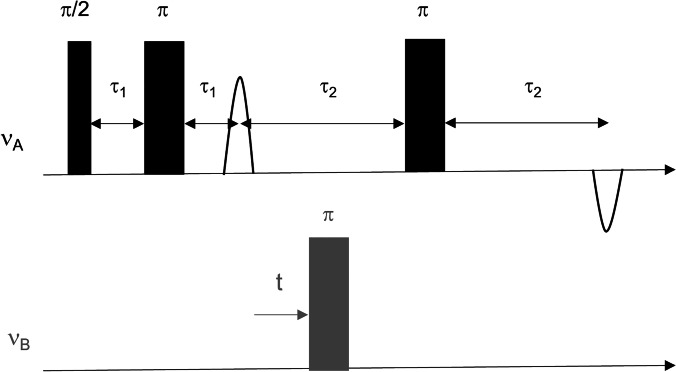

EPR spectroscopy is one of the few methods that can precisely measure distances in the range of 1.5–8.0 nm in biological systems (Schiemann et al. 2021), although longer distance measurements have been achieved by protein deuteration (Ward et al. 2010; Schmidt et al. 2016; Endeward et al. 2022). The most popular experiment is the four-pulse DEER/PELDOR experiment (Fig. 3). In the DEER experiment, the distance-dependent magnetic dipolar interaction between two or more unpaired electron spins is probed, and the resulting signal modulates with the frequency of the dipolar interaction. This analysis of the time domain signal leads to the measurement of the full distance distribution in the ensemble measurement.

Fig. 3.

Four-pulse DEER sequence, operating at two microwave frequencies (A represents the observer frequency, and B represents the pump frequency)

Consider a pair of two coupled electron spins, A and B. DEER is a two-frequency method, where spin A is observed at one frequency and spin B is excited at a different frequency. The experiment involves four microwave pulses, three at the observer frequency and one at the excitation, or pump, frequency. In the absence of the pump pulse, the echo sequence would lead to refocusing of all interactions that cause inhomogeneous line broadening, including electron–electron coupling. Only homogeneous broadening, due to relaxation processes and nuclear modulations, is not refocused. When the pump π pulse is applied at time t and inverts the B spin, the local magnetic field at the A spin exerted by the B spin changes by the dipolar coupling frequency. This results in a phase change of the refocused echo, which is observed as a modulation in the signal. The A spin gains an additional phase ϕ=ωeet, where wee is the coupling between A and B spins. Accordingly, the echo amplitude is modulated with cos(ωeet))Schiemann et al. 2021).

θAB is the angle between the static field, B0, and the interspin distance vector connecting the two spins.

βe is the Bohr magneton, gA and gB are the g-values of the A and B spins, rAB is the interspin distance between the A and B spins, and m0 is the permeability of free space. When A and B are nitroxide spin labels,

The spin echo signal is given by

where λ is the fraction of B spins excited by the pump pulse, often named the geometrical factor.

For an anisotropic disordered system with a homogeneous distribution of spins, the dipolar time evolution is averaged to a mono-exponential decay, which depends on the spin concentration (C), according to the following equation:

In solution, the DEER signal is a combination of the homogeneous background signal due to the weakly coupled spins and the signal from close interacting spins in the same biological macromolecule.

For an ensemble of spins, the general form of the DEER signal, V(t), is expressed as (Maryasov et al. 1998)

where P(r) is the DEER distance probability distribution, λ is the modulation depth, r is the distance between two spins, k is a constant which contains the g-values of the two spins, and θ is the angle between the interspin distance vector and the applied magnetic field. This form of the equation includes orientational effects as , which is known as the geometrical factor. This factor is dependent on the relative orientations of the two principal axis systems (PAS) of the g-tensors of the two spins. It describes the probability of exciting θ and is defined as

where mI is the nuclear quantum number of spin I, kxa is the ratio of the resonance frequency of the spins excited by the observer pulse to the observer frequency, kxb is the same ratio but for the pump pulse and pump frequency, φia and φib are the flip angles of the first and second spins, respectively, by the ith pulse, and δωi is the inhomogeneous broadening of the observer or pump pulses. If all orientations of the molecules are properly sampled, the geometrical factor is equal to sin(θ).

Cu(II) distance measurements

In the case of nitroxide spin labels, the interplay of the g and hyperfine anisotropies and the flexibility of the MTSL side chain typically randomizes the relative orientation between the spin labels. The effect of the orientation on the DEER signal is typically negligible in this instance, and the distance measurements can be obtained by a single experiment with the pump pulse positioned at the field of highest intensity at either X- or Q-band.

On the other, Cu(II) is characterized by a broad absorption EPR spectrum, and a typical microwave pulse of 24–40 ns can only excite a small portion of the possible θAB angles. Therefore, in principle, both the electron–electron dipolar frequency, ωee, and the geometrical factor, λ, depend on the position and the orientation of the magnetic field with respect to the interspin distance vector.

There has been much work done to rigorously understand these effects for the Cu(II) labels by using a combination of force field development, MD simulations, and quantum mechanical calculations (Bogetti et al. 2020; Gamble Jarvi et al. 2020b). For dHis, the Cu(II) position is highly localized; however, the coordination of Cu(II) to the imidazole-nitrogen in the Histidine side-chain is fairly elastic. Therefore, there is a variation in the length and angles of the bonds that chelate Cu(II) to the dHis motif. This variation leads to large distribution in the direction of the g-tensor (and more specifically, g||). This orientation variation is remarkably important in mitigating the effects of orientational selectivity, and such effects are minimal at X-band (Bogetti et al. 2020; Gamble Jarvi et al. 2021). On the other hand, orientational effects are possible at Q-band for rigid proteins and have been exploited to measure the relative orientations between secondary structure elements (Gamble Jarvi et al. 2019). More recently (Bogetti et al. 2022), a careful examination of excitation has produced a protocol for DEER measurements at Q-band wherein data acquisition at only three fields is sufficient for accurately measuring the distance distribution, even for modest pulse considerations. More improvements are anticipated by the use of arbitrary waveform generators.

For the case of Cu(II)-DPA DNA label, the moiety containing Cu(II) is attached to the DNA backbone using two rotatable bonds. The resulting fluctuations of the bonds are effective at washing out orientational effects, and distances can be measured by data acquisition at one field at either X- or Q-band (Bogetti et al. 2022).

Although DEER is the most used technique to measure distances using Cu(II) labels, other methods such as double quantum coherence (DQC) and relaxation-induced dipolar modulation enhancement (RIDME) spectroscopies have also been implemented on Cu(II) (Ruthstein et al. 2013; Ji et al. 2014; Ruthstein et al. 2015; Giannoulis et al. 2018; Russell et al. 2021). In particular, the use of dHis-Cu(II) and RIDME is an attractive methodology to measure distances at ca. 100 nM protein constants (Ackermann et al. 2022) as well as equilibrium constants.

Another important consideration for Cu(II) distance measurements is that the phase memory relaxation time of Cu(II), which is typically 3–4 μs, along with limited spectral excitation, lead to challenges for distance measurement beyond ca. 4.4 nm. Recent work has shown that with the introduction of deuterated solvents and cryoprotectants, the phase memory time can be significantly lengthened due to the reduction in the electron-nuclear dipolar interactions (Casto et al. 2021). Such solvent deuteration provides a reliable method to measure Cu(II)-Cu(II) distances up to ca 7 nm. If the protein molecule itself is also deuterated, measurable distances can reach up to 9 nm. Deuteration is a straightforward technique to increase the sensitivity and surpass the previous limitations of Cu(II).

Analysis of distance EPR measurements

There are several programs that can analyze orientation-independent data to extract the distance distribution. Examples are DeerLab (Fabregas Ibanez et al. 2020), DEERNet (Worswick et al. 2018), and DeerAnalysis (Jeschke 2006). The DEER time domain can be converted into a distance distribution using a variety of models, such as gaussian model distribution and Tikhonov regularization. Each model requires the subtraction of the contribution of the background signal, which can introduce user bias. Therefore, the community is increasingly moving to the use of a single-step method which accounts both for the distance distribution and the background signal (Stein et al. 2015; Worswick et al. 2018; Fabregas Ibanez et al. 2020). There are also programs available to extract the distance distribution for cases of orientational selectivity (Yang et al. 2010a, b).

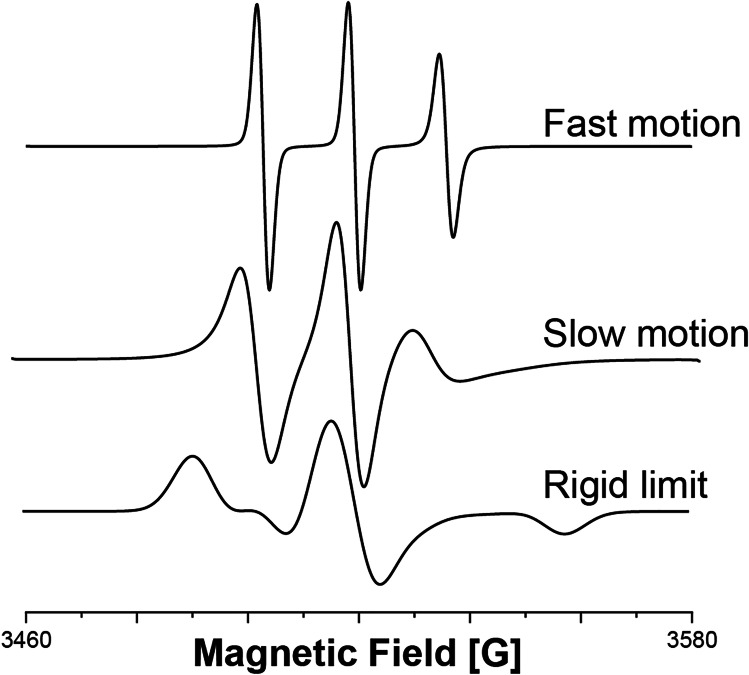

CW-EPR to measure protein dynamics

Continuous wave (CW)-EPR detects the electron Zeeman interaction between the unpaired electron and an applied magnetic field and hyperfine interactions between the electron spin and the nuclear spin. Room temperature (RT) CW-EPR experiments can measure the dynamics of the paramagnetic site. Resolving the backbone dynamics is useful because the small-scale site-specific flexibility of the backbone may play a larger role in molecular processes like protein-DNA interactions or ligand binding. The characteristics of the EPR spectra that are examined for spin-labeled systems are the line shape, linewidth, hyperfine values, and g-values, which each depend on the strength of the interaction of the spin label with its environment.

At X-band frequency (~ 9.5 GHz), we hierarchically differentiate between three types of motion (Fig. 4): (a) fast motion, (b) slow motion, and (c) rigid limit. In the fast motion region (less than ns timescale), CW-EPR spectra are characterized by the number of peaks and the intensity of the peaks. The rigid limit type spectrum is obtained when the motion of the spin label is restricted and the timescale of motion is greater than µs. At the rigid limit, CW-EPR can provide information about the coordination geometry of the unpaired electron. The most interesting region is the slow-motion region which involves motions with timescales between ns and µs. In this region, the line shape of the EPR spectrum is influenced by slight changes in the dynamics of the spin label, and a chemical or biological reaction can be followed in situ. The theory for the slow-tumbling region was described by Freed et al. (Budil et al. 1996).

Fig. 4.

CW-EPR simulations of nitroxide with different dynamics: fast motion (10−10 s), slow motion (10−8 s), and rigid limit (10−6 s)

CW-EPR of nitroxide spin labels

The nitroxide CW-EPR spectrum is characterized by the electron spin of ½ and the hyperfine splitting due to the interaction with the 14N nuclear spin of 1. For a highly dynamic system, the three allowed electron spin energy level transitions result in three peaks in the nitroxide spectrum (Fig. 4). The position of the peaks and spacing between each peak are characteristic of the dynamics of the system.

To quantitatively understand the backbone dynamics of a system, parameters such as rotational correlation times (τc) and ordering potentials can be compared between spectra. For nitroxide labels, the correlation time can be estimated from the height of the peaks and the linewidth of the central peak according to the following equation (Morrisett 1976):

where ΔH0 is the peak-to-peak line width of the MI = 0 component (the central peak) in Gauss, and h(− 1), h(0), and h(1) are the peak-to-peak heights of the MI = 1, 0, − 1 lines, respectively.

The CW-EPR spectra of nitroxide-labeled biomolecules are also sensitive to the polarity of the environment of the spin label, where the isotropic hyperfine value, Aiso, is proportional to the spin density on the nitrogen of the nitroxide group. When the solvent polarity is high, the spin density on the nitrogen is high as well, resulting in a higher Aiso value. However, when the polarity of the solvent is low, the hydrogen bonds with the nitroxide are weaker, which results in lower spin density on the nitrogen and a smaller Aiso value (Ruthstein et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2008).

Simulations of slow-motion region spectra of nitroxide spin labels

The partial averaging of EPR spectra by molecular motion or spin dynamics can produce overly complicated and irregular line shapes that require detailed spectral simulation to extract the desired information. The simulation theory developed by Freed et al. (Budil et al. 1996) is implemented in the nonlinear-least-squares (NLSL) slow motion program, as well as in EasySpin, using “chili” analysis (Stoll and Schweiger 2006).

The typical approach to generate simulations of slow-motion EPR spectra is to first determine the magnetic parameters from the rigid-limit spectrum by acquiring CW-EPR measurement at temperatures below 120 K. These parameters, which include the Euler angles described below, are fixed in the subsequent simulations. After the magnetic parameters are determined, the dynamics and ordering parameters are varied in the fitting procedure. The parameters of the simulations for nitroxide labels are described below.

Magnetic and structural parameters: The programs model the reorientation of one electron in a single nucleus system (typically a nitroxide) that is described by (a) the electron Zeeman interaction, including an orientation-dependent g-factor, (b) the electron-nuclear hyperfine interaction tensor, A, and (c) the isotropic nuclear Zeeman interaction.

To account for all orientation effects, several different coordinate systems are employed: (a) the magnetic tensor frame (Xmag, Ymag, Zmag) fixed on the molecule (by convention, the z-axis is along the p-orbital (or N–O p orbital for nitroxides), and the x-axis is along the N–O bond); (b) the rotational diffusion tensor frame (Xdiff, Ydiff, Zdiff), which is fixed on the backbone of the molecule where the nitroxide ring is connected; (c) the director frame (Xdir, Ydir, Zdir), which is taken to be along the symmetry of the restoring potential when an ordered material is concerned; (d) the laboratory frame (Xlab, Ylab, Zlab), which is determined by the external magnetic field along Z.

The relationships among these coordinate systems are specified by different sets of Euler angles. For nitroxide radicals, when neglecting the small deviation from axial symmetry of the hyperfine tensor and the small g-anisotropy, the transformation from the tensor frame to the diffusion frame can be described by a single angle β, which is referred to as the diffusion tilt angle. When the restoring potential has axial symmetry, only one angle θ is needed for the transformation from the diffusion frame to the director frame and one angle ψ from the director frame to the laboratory frame. This is summarized as follows:

Dynamics parameters: The spectral calculation incorporates several different models for rotational diffusion, including (a) Brownian rotational diffusion; (b) non-Brownian diffusion, including different types of jump-diffusion models; (c) anisotropic viscosity for motion in oriented fluids; and (d) discrete jump motion for hopping among a set of symmetry-related sites. For nitroxide spin-labeled soluble proteins, the Brownian diffusion model with axial symmetric rotational diffusion tensor, R, is adopted most often and defines two rotational diffusion rate constants, RII and R⊥.

Orientational potential: The tendency of the spin label to order is modeled by a restoring potential that is defined relative to the director axes. In general, it is written as a series of spherical harmonics of .

are dimensionless coefficients. In the case of axial orientational potential, U(θ) becomes

Practically, the orientational potential is reflected by an order parameter:

where P(θ) is the orientational distribution function:

KB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature.

CW-EPR of Cu(II) spin labels

The line shape of Cu(II) is characterized by an axial symmetry of the g-tensor (electron spin ½) with hyperfine splitting from the nuclear spin of 3/2. Since Cu(II) is an axially symmetric system, the and values are defined as

where are the parallel and perpendicular components of the g- and hyperfine tensors.

The rigid limit spectrum of Cu(II) can report on protein labeling (Gamble Jarvi et al. 2020a; Gamble Jarvi et al. 2021). The chelation of Cu(II) to dHis leads to distinct changes in the A|| which are clear markers of chelation (Gamble Jarvi et al. 2020a; Gamble Jarvi et al. 2021). In addition, there have also been recent developments in the use of dHis-Cu(II) to measure site-specific dynamics in proteins (Singewald et al. 2020; Singewald et al. 2022). These works have shown that Cu(II) CW-EPR can resolve dynamical changes of both α-helices and β-sheet structures. These developments are important because nitroxide CW-EPR line shapes of nitroxides are difficult to interpret in terms of β-sheet backbone dynamics due to the inherent flexibility of the nitroxide spin label and the influence of neighboring sidechains on the label. In addition, Cu(II) labeling appears to be sensitive to even small changes in dynamics due to the large anisotropy of the g-tensor of Cu(II) compared to nitroxides.

The use of EPR spectroscopy in resolving the transcription mechanism of E. coli CueR

Both pulsed EPR distance measurements and RT CW-EPR experiments are needed to obtain an overall picture of a biological system. In our work, we used EPR methods to study the E. coli CueR protein, which belongs to the MerR family of metal-sensing transcription regulators (Outten et al. 2000; Stoyanov et al. 2001; Martell et al. 2015). MerR family proteins exist in most bacterial species, and the metalloproteins have similar overall structure and sequence among species (Outten et al. 2000; Stoyanov et al. 2001; Newberry and Brennan 2004; Tottey et al. 2005). Hence, understanding a specific mechanism of one protein in this family allows for the deduction of a mechanism that can be applied to the majority of the metalloregulators of the entire MerR family (O'Halloran et al. 1989; Hobman 2007).

Figure 5 shows the crystal structure of CueR. CueR is a homodimer, and each monomer has an ααααββαα secondary structure (Changla et al. 2003). The first four helices, labeled α1 to α4 in Fig. 5, comprise the N-terminal DNA binding domain, and α5 and α6 comprise the C-terminal domain. The turn between the two sets of α5 and α6 helices forms the native metal binding site by a linear dithiol bridge with C112 and C120 residues.

Fig. 5.

Holo-CueR bound to DNA (PDB-ID: 4wlw). The protein is represented as a cartoon and colored in white. Spin-labeled sites G11C, M101C, and L60H_G64H are colored in blue, pink, and violet, respectively. G11’C, M101’C, and L60’H; G64’H represent the dimeric sites on the protein. Copper is colored orange according to the elemental color. (A) The complex from top view, (B) front perspective, and (C) side view including numbering of α helices

CueR can be found in many gram-negative bacteria (Hofmann et al. 2021) with sequence identity between 40 and 60% among species, suggesting that homologs hold a similar structure. However, CueR is responsible for the transcription of different proteins in different bacterial species. There is a direct correlation between the degree of pathogenicity and the number of proteins that CueR regulates in bacteria. For example, in the antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, CueR regulates at least five proteins, whereas in the less pathogenic E. coli, CueR regulates two proteins, CopA and CueO (Outten et al. 2000; Changla et al. 2003). CopA (Stoyanov et al. 2001) is known to scavenge Cu(I) from the cytosol and exports the ion to the periplasm, while CueO, a cytoplasmic protein, oxidizes Cu(I) to a less toxic Cu(II) form (Grass and Rensing 2001). There is a need for a greater understanding of how both high-sequence homology and distinct regulation mechanisms can exist in the same family of proteins.

Previously, structural measurements suggested that CueR coordinates to specific promoter regions as a function of Cu(I) concentrations, which leads to a specific conformation of both CueR and DNA, which eventually leads to transcription (Outten et al. 2000; Andoy et al. 2009). However, the crystal structures of the active (CueR-Ag(I)-DNA complex) and repressed states of CueR (CueR-DNA complex) were found to be similar (Philips et al. 2015), where the main structural difference between these complexes was located within the DNA conformation. Using single-molecule fluorescent resonance energy transfer (smFRET) measurements, Chen’s group has shown that CueR can exist in four different states in solution: apo-CueR, holo-CueR, apo-CueR bound to DNA, and holo-CueR bound to DNA (Joshi et al. 2012). This work also proposed that either changes in structure or structural fluctuations of CueR and DNA assist in the transcription process. However, the smFRET experiments were performed on only one labeled position in the DNA and the CueR protein and thus could not offer a clear model of the overall structural changes that underlie transcriptional regulation. In addition, the work relied on existing structural knowledge to translate information on kinetics into a mechanistic picture. Intriguingly, smFRET measurements also suggested that two complexes of Cu(I)-CueR-DNA-RNAp can be formed, where only one initiates transcription and the other does not and was termed the “dead-end” complex (Martell et al. 2015).

To resolve the CueR transcription mechanism and the role of Cu(I) in initiating transcription, the system must be measured in solution instead of as a static structure, and the role of concentration of both Cu(I) as well as protein must be systematically examined. In the next sections, both DEER distance measurements and CW-EPR were performed on the CueR-DNA-Cu(I) system to monitor the conformational flexibility and dynamics of the protein and DNA in solution upon coordinating Cu(I).

Conformational changes of E. coli CueR at various states during transcription

We utilized the benefits of pulsed EPR spectroscopy to reveal the conformational changes that CueR assumes upon DNA and Cu(I) binding (Sameach et al. 2017). Using the nitroxide labeling strategy, we generated several mutations: G11C which is between a1 and α2, G57C which is between α3 and α4, and M101C which is on α5. We then site-directedly spin labeled the various mutants with MTSL. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra confirmed that these point mutations did not alter the secondary structure of the protein. Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA) and pull-down experiments confirmed that both the wild-type (WT) CueR and the spin-labeled mutants bind the promoter.

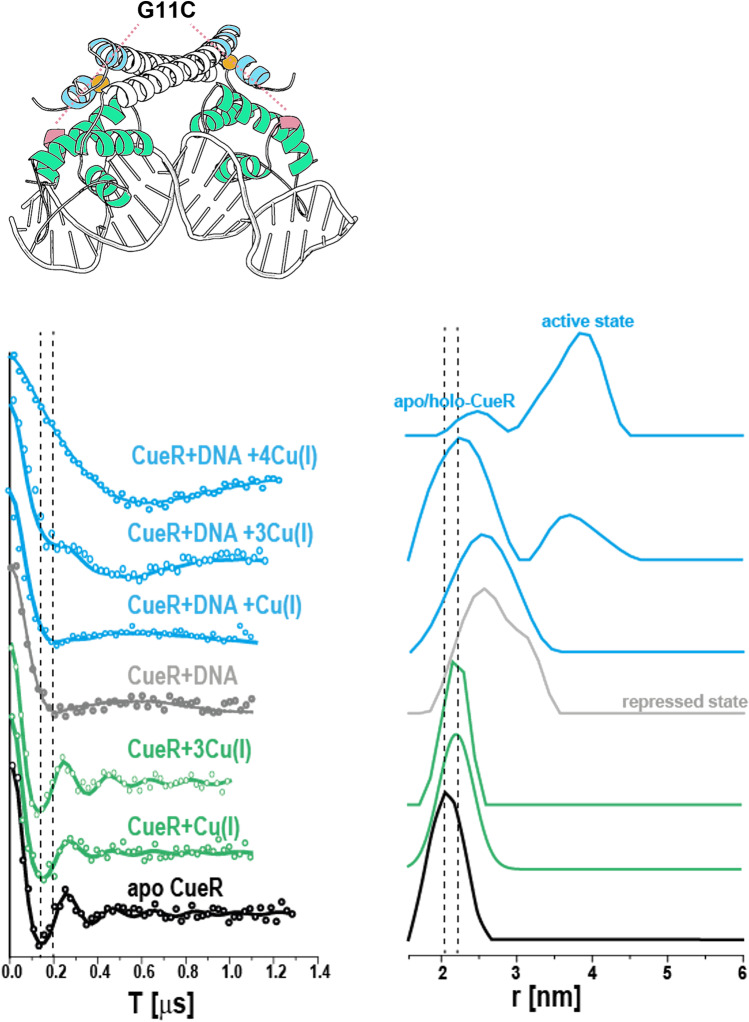

We performed DEER experiments on spin-labeled CueR in the presence and absence of Cu(I) and DNA. For all mutants, changes in the distance distribution were detected between the apo-CueR state and the active CueR state (in the presence of Cu(I) and DNA), indicating that CueR undergoes conformational changes upon Cu(I) and DNA binding. The largest change was detected for the G11C mutant located in the DNA binding domain (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

DEER time domain signals and corresponding distance distribution functions for a CueR G11C mutant in the presence and absence of DNA and under different concentrations of Cu(I). The data reveal clear differences between the various conformational states of the protein: apo-CueR (black curves), holo-CueR (CueR + Cu(I), green curves), repressed state (CueR + DNA, gray curves), and active states (CueR + DNA + Cu(I), blue curves). Reproduced from (Sameach et al. 2017) with permission from Elsevier

To understand the independent effects of Cu(I) on the CueR structure, we acquired DEER signals for the G11C mutant in the absence of DNA at increasing Cu(I) concentrations. For apo-CueR, the distance distribution was 2.1 ± 0.3 nm (mean ± s.d). Upon addition of Cu(I), from one or three equivalents of Cu(I) per CueR monomer did not lead to much change in the distance distribution. However, the addition of DNA alone to the CueR solution resulted in a broad distance distribution of 2.0–3.5 nm. The broad distribution may be due to either increased flexibility of CueR upon DNA binding or the presence of two species, free CueR and CueR bound to DNA. We then explored the effect of Cu(I) concentration on CueR structure in the presence of DNA. The addition of one equivalent of Cu(I) to the CueR-DNA complex preserved the conformational states observed in the apo-CueR-DNA complex. However, in the presence of three equivalents of Cu(I), an additional conformational state emerged, with a most probable distance of 3.8 ± 0.5 nm. In the presence of four equivalents of Cu(I), the population of the 3.8 nm distance increased.

These DEER results suggest that there are distinct conformations of apo- and active-CueR states. However, the broad distance distributions of the active-CueR states indicate that there are multiple conformational states which could not be resolved with nitroxide spin-labeling due to the flexibility of the side chain.

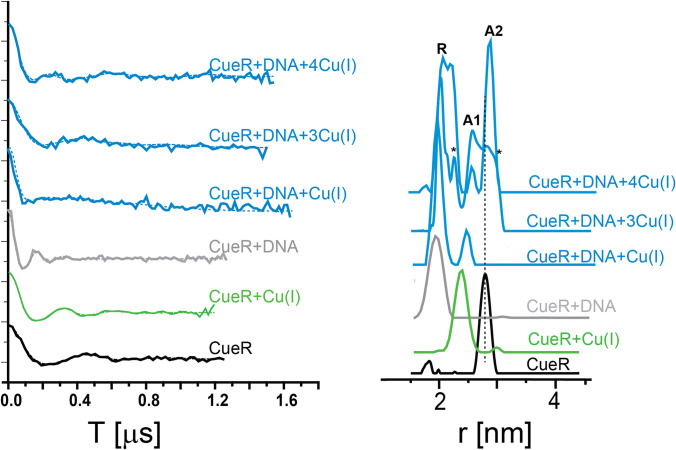

To advance our understanding of the different active-state conformations, we used the dHis-Cu(II) labeling approach (Fig. 2B). Compared to MTSL, a 4–5 times narrower distance distribution is typically obtained with the dHis-Cu(II) methodology, increasing the resolution of different and narrow conformational states. We generated an L60H/G64H double histidine mutant in CueR, which is located on the α4 helix and connects the Cu(I) binding domain to the DNA binding domain (Sameach et al. 2019). Figure 7 shows the DEER signals and corresponding distance distributions of the CueR L60H/L64H mutant as a function of Cu(I) and DNA binding. The experiments were carried out at fixed observer and pump frequencies for a precise comparison at the g⊥ region. At this region with Q-band DEER measurements, a range of 500 G around g⊥ does not show orientational dependency which is likely due to the conformational flexibility of the CueR loop region. The data was analyzed with Tikhonov regularization, where the x-axis in the distance distribution was corrected based on Cu(II) g-values.

Fig. 7.

DEER time domain signals and corresponding distance distribution functions for a CueR L60H/G64H mutant, in the presence and absence of DNA and under different concentrations of Cu(I). A1 and A2 represent the two active states of the protein (CueR + DNA + Cu(I). R represents the repressed state (CueR + DNA). Reproduced from (Sameach et al. 2019) with permission from Wiley

In the apo-state, the distance distribution detected was 2.7 ± 0.1 nm (mean ± s.d). The addition of Cu(I) to the solution changed the distribution to 2.4 ± 0.2 nm. The addition of DNA to apo-CueR (repressed state) resulted in a distribution centered at 2.0 nm with a standard deviation ± 0.2 nm. Adding one equivalent of Cu(I) to a CueR-DNA solution resulted in a bimodal distance distribution with distances centered at 2.0 ± 0.1 nm, which is similar to the repressed state, and at 2.5 ± 0.1 nm. When adding more Cu(I) to the solution, the population of the 2.5 nm distance increased, and an additional distance of 2.8 ± 0.1 nm appeared. We assigned the 2.5 nm and 2.8 nm distribution to two different active conformational states and named them A1 and A2, respectively.

The DEER data from both MTSL and dHis-Cu(II) labeling allowed the deduction of the conformations of apo-CueR and the two active states of CueR. To model these conformational states, we used the elastic network model (ENM) implemented in the Multiscale Modelling of Macromolecular Systems (MMM) software (Jeschke 2018). The crystal structure of Cu(I)-CueR (PDB 1q05) was used as input for the modeling. Figure 8 shows the obtained structures for the three different states of CueR. The models indicate that in the active states, the two DNA binding domains of CueR dimer are getting closer to each other, which supports the idea that the promoter region bends upon CueR binding. Notably, the DNA binding domain of the A1 active state is a bit more compressed than the A2 state.

Fig. 8.

Elastic network models (ENM) – computed structural models for A1 (green) and A2 (pink) active states and apo-state, considering both MTSL and dHis-Cu(II)-NTA DEER constraints: (A) apo-CueR, (B) A1 holo-CueR, (C) A2 holo-CueR, and (D) structural alignment of A1 and A2

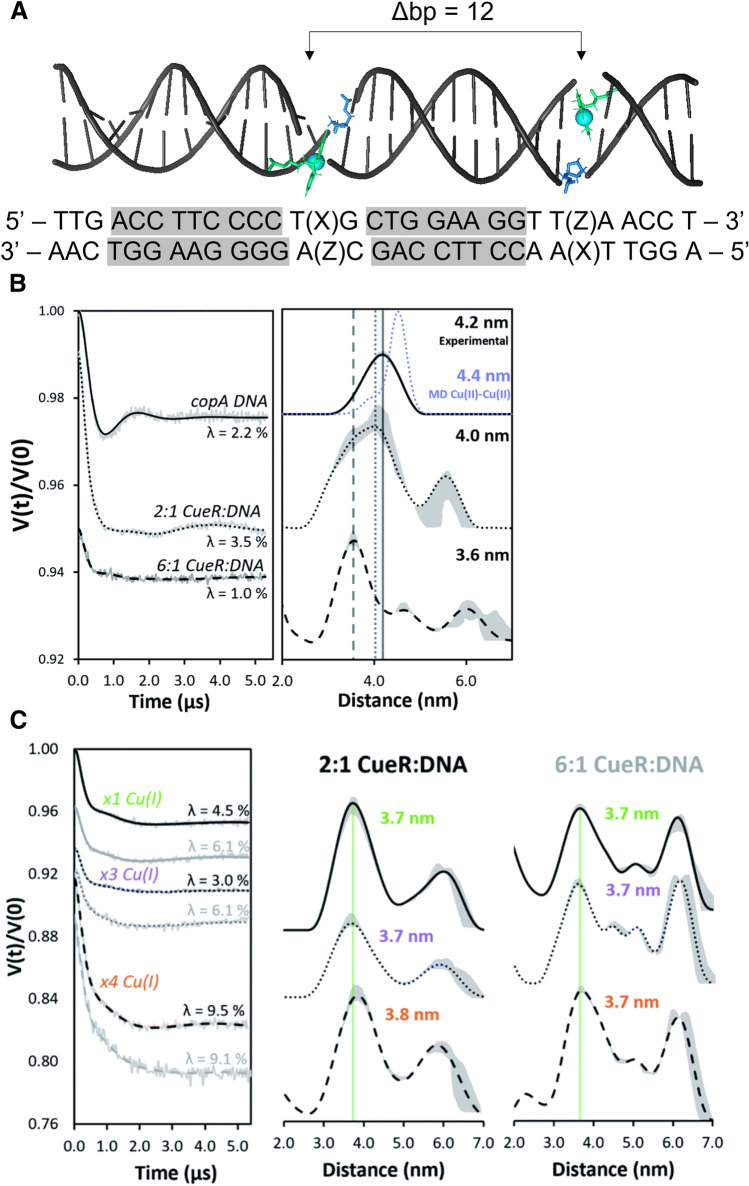

Conformational changes of the promoter at various states during transcription

To better understand the interaction between CueR and the promoter region, we performed DEER measurements on spin-labeled DNA as a function of CueR and Cu(I) binding (Casto et al. 2022). Figure 9A shows the copA DNA sequence used for the EPR measurements. The nucleotides that are involved in the interaction with the CueR protein are highlighted in gray. Each DNA strand included a 2,2-dipicolylamine (DPA) phosphoramidite moiety capable of chelating Cu(II), and these were separated by 12 base pairs (bp). The DEER measurements were performed in the g⊥ region. For this label, orientational selectivity effects are negligible even at Q-band (Ghosh et al. 2020a, b). The data were analyzed with ComparativeDeerAnalyzer consensus distance distributions utilizing DEERNet and automated Tikhonov regularization fitting. DEER measurements on the DNA produced a distance distribution centered at 4.2 nm (see Fig. 9) which was anticipated for a 12 bp separation of typical B-DNA. When adding CueR into the solution, an interesting phenomenon occurred. In the presence of 2:1 CueR:DNA, the most probable distance obtained is 4.0 nm, which is similar to that observed in free DNA. However, in the presence of excess CueR (at a ratio of 6:1 CueR:DNA), the most probable distance decreased to 3.6 nm, suggesting a bending of the DNA. This indicates that a high concentration of CueR promotes the bending of the DNA, even in the absence of Cu(I) ions. This observation was unexpected from prior structural measurements and highlights the importance of solution EPR methodology. In the presence of Cu(I) ions, there were negligible differences in the DEER distance distributions between the 2:1 CueR:DNA and 6:1 CueR:DNA samples. Importantly, the presence of Cu(I) ions facilitated the bending of the DNA, supported by the 3.6 nm distance, without the need for high CueR concentrations.

Fig. 9.

(A) The copA promoter DNA sequence with Cu(II)-DPA labeled sites separated by 12 base pairs (bp). The gray regions of the sequence represent sites that directly interact with CueR. (B) DEER time domain signals and corresponding distance distribution functions for copA DNA labeled with Cu(II)-DPA without Cu(I) bound and (C) with Cu(I) bound. Reproduced from (Casto et al. 2022)

The overall DEER data suggest that Cu(I) has a significant role both in the conformational changes of CueR as well as in the DNA bending.

Dynamical changes of E. coli CueR at various states during transcription

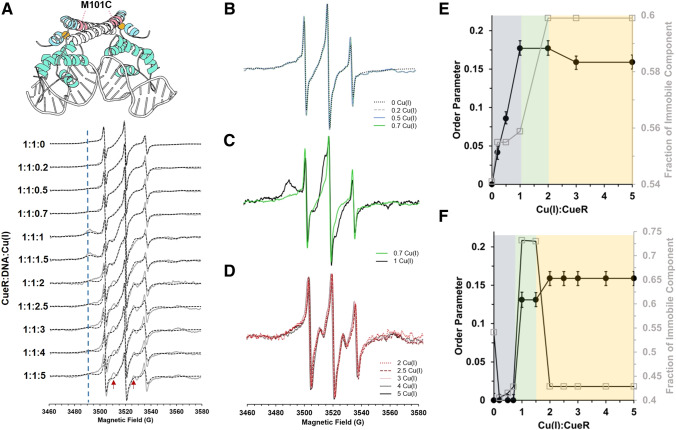

To further explore the role of Cu(I) in CueR transcription initiation, we performed RT CW-EPR experiments on various spin-labeled CueR mutants. Each of the three mutants was measured as a function of different Cu(I) ion concentrations in both the absence and presence of DNA (Yakobov et al. 2022). The three mutants were M101C, located in the α5 helix next to the Cu(I) binding site, G57C, located on a loop between α3 and α4 helices, and A16C, located in the α2 helix at the DNA binding site. The spectra suggest only minor changes in DNA binding (Yakobov et al. 2022).

However, when Cu(I) is added to the M101C and A16C mutants in the absence and presence of DNA, clear changes in the line shapes were detected. The spectra were simulated using two components, one highly mobile and the other less mobile (Fig. 10). The most interesting effect was detected for the CueR_M101C mutant, near the Cu(I) binding site. Simulations of the spectra using slow motional theory (Budil et al. 1996) as implemented in EasySpin suggests that near the Cu(I) binding site and in the absence of DNA, an increase in the order parameter is detected as a function of Cu(I) concentration. At higher copper concentrations, a slight decrease in order parameters and thus an increase in dynamics were measured. In the presence of DNA, we also observed a Cu(I) concentration-dependent change in the order parameter. In a ratio of 0–1 equivalents of Cu(I):CueR, changes in the CW-EPR spectra were negligible. However, in a ratio of 1–2 equivalents of Cu(I):CueR, a higher order parameter was detected near the Cu(I) binding site (Fig. 10), indicative of slower dynamics. At higher copper concentrations, a slight increase in order parameters was observed.

Fig. 10.

(A) RT CW-EPR spectra (solid gray lines) for CueR M101C mutant in the presence of DNA as a function of different Cu(I) concentrations. Dashed black lines represent the fitted spectra. The blue dashed line indicates the broadening that corresponds to the immobile component at 3490 G. The red arrows mark signals originating from an increase in the order parameter for the immobile component. (B) RT CW-EPR spectra for four different Cu(I) concentrations in the range of 0–0.7 vs. CueR monomer concentration. (C) RT CW-EPR spectra for 1:1:0.7 and 1:1:1 Cu(I):CueR:DNA ratio. (D) RT CW-EPR spectra for Cu(I) concentrations in the range of 2–5 vs. CueR monomer concentration. (E) Plots of the order parameter as a function of Cu(I) concentration in the absence and (F) presence of DNA. Reproduced from (Yakobov et al. 2022)

For the CueR_A16C mutant, near the DNA binding site, an overall increase in dynamics measured as a change in τc was observed as a function of Cu(I) coordination in both the absence and presence of DNA. Overall, the CW-EPR measurements and simulations support changes in dynamics at both Cu(I) and DNA binding sites as a function of copper concentrations, shedding light on the transcription mechanism.

The use of CW-EPR to follow dynamical changes led to an understanding that one of the active states is less dynamic and has a more rigid structure. This state is detected when 1–2 Cu(I) ions are bound to a CueR monomer, suggesting that this is the active state that ultimately leads to transcription initiation. The addition of more Cu(I) to the solution increases the dynamics of CueR slightly, leading to a weaker interaction between the CueR and the DNA. Figure 11 shows the overall mechanism of Cu(I) coordination and DNA binding to CueR. The four different states are (1) free DNA and apo-CueR, (2) DNA interacting with apo-CueR (repressed state), (3) free DNA and holo-CueR, and (4) DNA interacting with holo-CueR (active state). These different states are in equilibrium and thus simultaneously present in solution. The EPR data allowed for a qualitative analysis of changes in dynamics between these different states (Yakobov et al. 2022). Differences in dynamics are colored from violet to cyan, where violet represents lower dynamics and cyan represents higher dynamics. It became apparent that the dynamics of the DNA binding domain are heavily influenced by copper binding nearly 3 nm away. However, the binding of DNA resulted in a minor decrease in dynamics within the copper-binding site. These findings indicate that the influence of the copper-binding domain on the DNA binding domain is stronger than vice versa, revealing a unidirectional allosterically driven transcription mechanism of CueR.

Fig. 11.

Allostery-driven changes in dynamics of CueR. Qualitative changes in dynamics of CueR upon DNA or Cu(I) binding. CueR is shown in cartoon representation and colored according to the dynamics of the DNA and Cu(I) binding domains. Low dynamics are represented as violet, and high dynamics are represented as cyan. Four different states were assessed: apo-CueR and free DNA, apo-CueR bound to DNA (repressed state), holo-CueR and free DNA, holo-CueR bound to DNA (active state)

Summary and outlook

Here, we demonstrated that EPR spectroscopy provides important information of unprecedented resolution on the mechanism of action of transcription factors and can report on different conformations and dynamical changes during the transcription process. EPR spectroscopy is advantageous as a biophysical tool because these measurements are.

performed in solution,

independent of protein or system size,

applicable to macromolecular complexes of protein, DNA, and RNA,

sensitive to minuscule conformational changes,

sensitive to differences in dynamics of a specific state, and

capable of monitoring structural and dynamic information simultaneously.

We present here a case study on E. coli CueR, a bacterial metalloregulator. Using DEER constraints, we were able to distinguish between the apo-state and two conformations of the active states. Moreover, we shed light on allosteric changes in two domains of the transcription regulator. Dynamic data obtained from EPR measurements provided the necessary information to complement the static structures provided by RCSB PDB. Finally, the conformational and dynamic information provide additional restraints for computational modeling, allowing the creation of accurate models of complex processes present in any living organism. Thus, the described here methodology fills the gap between static models and the dynamic behavior of complex machineries required for cell survival.

Abbreviations

- EPR

Electron paramagnetic resonance

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- CW

Continuous wave

- SDSL

Site-directed spin-labeling

- MTSL

Methanethiosulfonate spin-label

- DEER

Double electron–electron resonance

- sm-FRET

Single-molecule fluorescent resonance energy transfer

- PAS

Principal axis system

- WT

Wild type

- EMSA

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay

- CD

Circular dichroism

- RT

Room temperature

Funding

SR and SS acknowledge the support from the National Science Foundation-Binational Science Foundation (NSF-BSF, NSF no. MCB-2006154, BSF no. 2019723) and BSF support 2018029.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We got copyright permission to publish Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. Figures 9 and 10 are published as CC BY. All other figures are original for this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

S. Saxena, Email: sksaxena@pitt.edu

S. Ruthstein, Email: Sharon.ruthstein@biu.ac.Il

References

- Ackermann K, Wort JL, Bode BE. Pulse dipolar EPR for determining nanomolar binding affinities. Chem Commun. 2022;58:8790–8793. doi: 10.1039/d2cc02360a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andoy NM, Sarkar SK, Wang Q, Panda D, Benitez JJ, Kalininskiy A, Chen P. Single-molecule study of metalloregulator CueR-DNA interactions using engineered holiday junctions. Biophys J. 2009;97:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold FH, Haymore BL. Engineered metal-binding proteins: purification to protein folding. Science. 1991;252:1796–1797. doi: 10.1126/science.1648261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogetti X, Ghosh S, Gamble Jarvi A, Wang J, Saxena S. Molecular dynamics simulations based on newly developed force field parameters for Cu(2+) spin labels provide insights into double-histidine-based double electron-electron resonance. J Phys Chem B. 2020;124:2788–2797. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogetti X, Hasanbasri Z, Hunter HR, Saxena S. An optimal acquisition scheme for Q-band EPR distance measurements using Cu(2+)-based protein labels. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2022;24:14727–14739. doi: 10.1039/D2CP01032A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budil DE, Lee S, Saxena S, Freed JH. Nonlinear-least-squares analysis of slow-motion EPR spectra in one and two dimensions using a modified Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. J Magn Reson Ser A. 1996;120:155–189. doi: 10.1006/jmra.1996.0113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casto J, Mandato A, Saxena S. dHis-troying barriers: deuteration provides a pathway to increase sensitivity and accessible distances for Cu(2+) Labels. J Phys Chem Lett. 2021;12:4681–4685. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casto J, Mandato A, Hofmann L, Yakobov I, Ghosh S, Ruthstein S, Saxena S. Cu(II)-based DNA labeling identifies the structural link between transcriptional activation and termination in a metalloregulator. Chem Sci. 2022;13:1693–1697. doi: 10.1039/D1SC06563G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavet JS, Meng W, Pennella MA, Appelhoff RJ, Giedroc DP, Robinson NJ. A Nickel-coblat-sensing ArsR-SmtB family repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38441–38448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changla A, Chen K, Holschen J, Outten CE, O'Halloran TV, Mondragon A. Molecular basis of metal-ion selectivity and zeptomolar sensitivity by CueR. Science. 2003;301:1383–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1085950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Tang CY, Chuang WT, Lee JJ, Tsai YL, Chan JCC, Lin CY, Liu YC, Cheng SF. A facile route to synthesizing functionalized mesoporous SBA-15 materials with platelet morphology and short mesochannels. Chem Mater. 2008;20:3906–3916. doi: 10.1021/cm703500c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Columbus L, Hubbell WL. A new spin on protein dynamics. Trends in Biochem Sci. 2002;27:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TF, Shannon MD, Putterman MR, Arachchige RJ, Sengupta I, Gao M, Jaroniec CP, Saxena S. Cysteine-specific Cu2+ chelating tags used as paramagnetic probes in double electron electron resonance. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:2839–2843. doi: 10.1021/jp5103143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TF, Putterman MR, Desai A, Horne WS, Saxena S. The double-histidine Cu(2)(+)-binding motif: a highly rigid, site-specific spin probe for electron spin resonance distance measurements. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:6330–6334. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalaloyan A, Martorana A, Barak Y, Gataulin D, Reuveny E, Howe A, Elbaum M, Albeck S, Unger T, Frydman V, Abdelkader EH, Otting G, Goldfarb D. Tracking conformational changes in calmodulin in vitro, in cell extract, and in cells by electron paramagnetic resonance distance measurements. ChemPhysChem. 2019;20:1860–1868. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201900341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endeward B, Hu Y, Bai G, Liu G, Prisner TF, Fang X. Long-range distance determination in fully deuterated RNA with pulsed EPR spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2022;121:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabregas Ibanez L, Jeschke G, Stoll S. DeerLab: a comprehensive software package for analyzing dipolar electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy data. Magn Reson (Gott) 2020;1:209–224. doi: 10.5194/mr-1-209-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AM, Burrows CJ. On the irrelevancy of hydroxyl radical to DNA damage from oxidative stress and implications for epigenetics. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:6524–6528. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00579g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble Jarvi A, Cunningham TF, Saxena S. Efficient localization of a native metal ion within a protein by Cu(2+)-based EPR distance measurements. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2019;21:10238–10243. doi: 10.1039/c8cp07143h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble Jarvi A, Casto J, Saxena S. Buffer effects on site directed Cu(2+)-labeling using the double histidine motif. J Magn Reson. 2020;320:106848. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2020.106848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble Jarvi A, Sargun A, Bogetti X, Wang J, Achim C, Saxena S. Development of Cu(2+)-based distance methods and force field parameters for the determination of PNA conformations and dynamics by EPR and MD simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2020;124:7544–7556. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c05509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble Jarvi A, Bogetti X, Singewald K, Ghosh S, Saxena S. Going the dHis-tance: site-directed Cu(2+) labeling of proteins and nucleic acids. Acc Chem Res. 2021;54:1481–1491. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Lawless MJ, Rule GS, Saxena S. The Cu(2+)-nitrilotriacetic acid complex improves loading of alpha-helical double histidine site for precise distance measurements by pulsed ESR. J Magn Reson. 2018;286:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Lawless MJ, Brubaker HJ, Singewald K, Kurpiewski MR, Jen-Jacobson L, Saxena S. Cu2+-based distance measurements by pulsed EPR provide distance constraints for DNA backbone conformations in solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Casto J, Bogetti X, Arora C, Wang J, Saxena S. Orientation and dynamics of Cu(2+) based DNA labels from force field parameterized MD elucidates the relationship between EPR distance constraints and DNA backbone distances. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2020;22:26707–26719. doi: 10.1039/D0CP05016D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoulis A, Motion CL, Oranges M, Buhl M, Smith GM, Bode BE. Orientation selection in high-field RIDME and PELDOR experiments involving low-spin Co(II) ions. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018;20:2151–2154. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07248a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoulis A, Feintuch A, Barak Y, Mazal H, Albeck S, Unger T, Yang F, Su XC, Goldfarb D. Two closed ATP- and ADP-dependent conformations in yeast Hsp90 chaperone detected by Mn(II) EPR spectroscopic techniques. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:395–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916030116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoulis A, Ben-Ishay Y, Goldfarb D. Characteristics of Gd(III) spin labels for the study of protein conformations. Methods Enzymol. 2021;651:235–290. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2021.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedroc DP, Arunkumar AI (2007) Metal sensor proteins: nature's metalloregulated allosteric switches. Dalton Trans 3107-3120. 10.1039/b706769k [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grass G, Rensing C. CueO is a multi-copper oxidase that confers copper tolerance in escherichia coli. BioChem BioPhys Res Commun. 2001;286:902–908. doi: 10.1039/d0cp05016d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki JN, Fletterick RJ, Craik CS. Engineered metalloregulation in enzymes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1992;17:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobman JL. MerR family transcription activators: similar designs, different specialities. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1275–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann L, Hirsch M, Ruthstein S. Advances in understanding of the copper homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2050. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell WL, Gross A, Langen R, Lietzow MA. Recent advances in site-directed spin labeling of proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:649–656. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke G. DeerAnalysis2006 –A comprehensive software package for analyzing pulsed ELDOR Data. Appl Magn Reson. 2006;30:473–498. doi: 10.1007/BF03166213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke G. MMM: A toolbox for integrative structure modeling. Protein Sci. 2018;27:76–85. doi: 10.1002/pro.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji M, Ruthstein S, Saxena S. Paramagnetic metal ions in pulsed ESR distance distribution measurements. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:688–695. doi: 10.1021/ar400245z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi CP, Panda D, Martell DJ, Andoy NM, Chen TY, Gaballa A, Helmann JD, Chen P. Direct substitution and assisted dossociation pathways for turning off transcription by a MerR-family metalloregulator. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2012;109:15121–15126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208508109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K, Voss J, He M, Hubbell WL, Kaback HR. Engineering a metal binding site within a polytopic membrane protein, the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochem. 1995;34:6272–6277. doi: 10.1021/bi00019a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless MJ, Ghosh S, Cunningham TF, Shimshi A, Saxena S. On the use of the Cu(2+)-iminodiacetic acid complex for double histidine based distance measurements by pulsed ESR. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2017;19:20959–20967. doi: 10.1039/c7cp02564e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless MJ, Sarver J, Saxena S. Nucleotide-independent copper(II)-based distance measurements in DNA by pulsed ESR spectroscopy. Ange Chem In Ed. 2017;56:2115–2117. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell DJ, Joshi CP, Gaballa A, Santiago AG, Chen TY, Jung W, Helmann JD, Chen P. Metalloregulator CueR biases RNA polymerase's kinetic sampling of dead-end or open complex to repress or activate transcription. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2015;112:13467–13472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515231112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryasov AG, Tsvetkov YD, Raap J. Weakly coupled radical pairs in solids: ELDOR in ESE structure studies. Appl Magn Reson. 1998;14:101–113. doi: 10.1007/BF03162010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisett JD. Spin labeling, theory and apllications. London: Academic Press, Inc.; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Meron S, Shenberger Y, Ruthstein S. The advantages of EPR spectroscopy in exploring diamagnetic metal ion binding and transfer mechanisms in biological systems. Magnetochemistry. 2022;8:3. doi: 10.3390/magnetochemistry8010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newberry KJ, Brennan RG. The structural mechanism for transcription activation by MerR family member multidrug transporter activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20356–20362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll AJ, Miller DJ, Futterer K, Ravelli R, Allemann RK (2006) Designed high affinity Cu2+-binding alpha-helical foldamer. 10.1021/ja061513u [DOI] [PubMed]

- O'Halloran TV, Frantz B, Shin MK, Ralston DM, Wright JG. The MerR heavy metal receptor mediates positive activation in a topologically novel transcription complex. Cell. 1989;56:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90990-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten CE, O'Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling Zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten FW, Outten CE, Hale JA, O'Halloran TV. Transcriptional activation of an Escherichia coli copper efflux regulon by the chromosomal Mer homologue CueR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31024–31029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips SJ, Canalizo-Hernandez M, Yildirim I, Schatz GC, Mondragon A, O'Halloran TV. Allosteric transcriptional regulation via changes in the overall topology of the core promoter. Science. 2015;349:877–881. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Gross A, Jeschke G, Godt A, Drescher M. Gd(III)-PyMTA label is suitable for in-cell EPR. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:15366–15378. doi: 10.1021/ja508274d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NJ, Winge DR. Copper Metallochaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:537–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell H, Stewart R, Prior C, Oganesyan VS, Gaule TG, Lovett JE. DEER and RIDME measurements of the nitroxide-spin labelled copper-bound amine oxidase homodimer from arthrobacter globiformis. Appl Magn Reson. 2021;52:995–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00723-021-01321-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthstein S, Frydman V, Kababya S, Landau M, Goldfarb D. Study of the formation of the mesoporous material SBA-15 by EPR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:1739–1748. doi: 10.1021/jp021964a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthstein S, Ji M, Mehta P, Jen-Jacobson L, Saxena S. Sensitive Cu2+-Cu2+ distance measurements in a protein-DNA complex by double-quantum coherence ESR. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:6227–6230. doi: 10.1021/jp4037149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthstein S, Ji M, Shin BK, Saxena S. A simple double quantum coherence ESR sequence that minimizes nuclear modulations in Cu(2+)-ion based distance measurements. J Magn Reson. 2015;257:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameach H, Narunsky H, Azoulay Ginsburg S, Moskovitz Y, Zehavi Y, Jueven-Gershon T, Ben-Tal N, Ruthstein S. Structural and dynamics characterization of the MerR family metalloregulator CueR in its respression and activation states. Structure. 2017;25:988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameach H, Ghosh S, Gevorkyan-Airapetov L, Saxena S, Ruthstein S. EPR spectroscopy detects various active state conformations of the transcriptional regulator CueR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:3053–3056. doi: 10.1002/anie.201810656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiemann O, Heubach CA, Abdullin D, Ackermann K, Azarkh M, Bagryanskaya EG, Drescher M, Endeward B, Freed JH, Galazzo L, Goldfarb D, Hett T, Hofer LE, Ibanez LF, Hustedt EJ, Kucher S, Kuprov I, Lovett JE, Meyer A, Ruthstein S, Saxena S, Stoll S, Timmel CR, Di Valentin M, Mchaourab HS, Prisner TF, Bode BE, Bordignon E, Bennati M, Jeschke G. Benchmark test and guidelines for DEER/PELDOR experiments on nitroxide-labeled biomolecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:17875–17890. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c07371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Walti MA, Baber JL, Hustedt EJ, Clore GM. Long distance measurements up to 160 A in the GroEL tetradecamer using Q-Band DEER EPR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:15905–15909. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Tian L, Clore GM. Probing conformational states of the finger and thumb subdomains of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase using double electron-electron resonance electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochem. 2018;57:489–493. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singewald K, Bogetti X, Sinha K, Rule GS, Saxena S. Double histidine based EPR measurements at physiological temperatures permit site-specific elucidation of hidden dynamics in enzymes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59:23040–23044. doi: 10.1002/anie.202009982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singewald K, Wilkinson JA, Hasanbasri Z, Saxena S. Beyond structure: Deciphering site-specific dynamics in proteins from double histidine-based EPR measurements. Protein Sci. 2022;31:e4359. doi: 10.1002/pro.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RA, Beth AH, Hustedt EJ. A straightforward approach to the analysis of double electron-electron resonance data. Methods Enzymol. 2015;563:531–567. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S, Schweiger A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov JV, Hobman JL, Brown NL. CueR (YbbI) of Escherichia coli is a MerR family regulator controlling expression of the copper exporter CopA. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:502–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangprasertchai NS, Di Felice R, Zhang X, Slaymaker IM, Vazquez Reyes C, Jiang W, Rohs R, Qin PZ. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated DNA unwinding detected using site-directed spin labeling. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:1489–1493. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RJ, Van Dam ME, Casimiro D, Haymore BL, Arnold FH. Cu(II)-binding properties of a cytochrome c with a synthetic metal-binding site: His-X3-His in an alpha-helix. Proteins. 1991;10:156–161. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottey S, Harvie DR, Robinson NJ. Understanding how cells allocate metals using metal sensors and metallochaperone. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:775–783. doi: 10.1021/ar030011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss J, Salwinski L, Kaback HR, Hubbell WL. A method for distance determination in proteins using a designed metal ion binding site and site-directed spin labeling: evaluation with T4 lysozyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:12295–12299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Bowman A, Sozudogru E, El-Mkami H, Owen-Hughes T, Norman DG. EPR distance measurements in deuterated proteins. J Magn Reson. 2010;207:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren GM, Stein RA, McHaourab HS, Eichman BF. Movement of the RecG Motor Domain upon DNA Binding Is Required for Efficient Fork Reversal. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3049. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekley CM, He C. Developing drugs targeting transition metal homeostasis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;37:6–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wladron KJ, Rutherford JC, Ford D, Robinson NJ. Metalloproteins and metal sensing. Nature. 2009;460:823–830. doi: 10.1038/nature08300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worswick SG, Spencer JA, Jeschke G, Kupro I. Deep neural network processing of DEER data. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaat5218. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wort JL, Ackermann K, Norman DG, Bode BE. A general model to optimise Cu(II) labelling efficiency of double-histidine motifs for pulse dipolar EPR applications. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021;23:3810–3819. doi: 10.1039/D0CP06196D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wort JL, Arya S, Ackermann K, Stewart AJ, Bode BE. Pulse dipolar EPR reveals double-histidine motif Cu(II)-NTA spin-labeling robustness against competitor ions. J Phys Chem Lett. 2021;12:2815–2819. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakobov I, Mandato A, Hofmann L, Singewald K, Shenberger Y, Gevorkyan-Airapetov L, Saxena S, Ruthstein S. Allostery-driven changes in dynamics regulate the activation of bacterial copper transcription factor. Protein Sci. 2022;31:e4309. doi: 10.1002/pro.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Ji M, Saxena S. Practical aspects of copper ion-based double electron electron resonance distance measurements. Appl Magn Reson. 2010;39:487–500. doi: 10.1007/s00723-010-0181-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Kise D, Saxena S. An approach towards the measurement of nanometer range distances based on Cu2+ ions and ESR. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:6165–6174. doi: 10.1021/jp911637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Yang F, Gong YJ, Chen JL, Goldfarb D, Su XC. A reactive, rigid Gd(III) labeling tag for in-cell EPR distance measurements in proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:2914–2918. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]