INTRODUCTION

Pregnant and postpartum women with pulmonary conditions represent a unique and complex population group, with some respiratory disorders occurring frequently in this population. For instance, asthma, the most commonly diagnosed respiratory condition in pregnancy, occurs in up to 13% of pregnant women.1–3 Sleep-disordered breathing, although infrequently diagnosed and coded in the pregnant population,4,5 is identified in 9% of low-risk pregnancies screened for the disorder, but in up to 70% of pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and small for gestational age.6–8

Several pulmonary conditions may be first diagnosed during pregnancy (eg, obstructive sleep apnea and pulmonary embolism) or may be exacerbated by pregnancy (eg, asthma and pulmonary hypertension). Respiratory conditions such as pulmonary sepsis, pulmonary embolism, or pulmonary edema are a frequent cause of severe maternal morbidity9,10 and an important contributor to maternal mortality.9 Furthermore, pulmonary diseases are associated with a higher risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, including low birth weight, preterm birth, and neonatal mortality.1,5,11–14 Understanding the impact of pulmonary diseases on pregnancy and the impact of pregnancy on the natural course of pulmonary diseases is, therefore, essential for pulmonary care providers.

Physiologic changes in pregnancy and fetal considerations may lead to modifications in investigative approaches and treatment modalities. Indeed, a nuanced approach is required when interpreting certain laboratory values and imaging findings altered by pregnancy physiology, and these pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic changes should be accounted for when prescribing in pregnancy.15,16 In addition, fetal safety must be taken into consideration when planning for radiologic testing and choosing from available therapeutic options, without compromising the care of the mother.

Thus, a review of general principles to apply when caring for pregnant and postpartum women is of paramount importance to avoid the pitfalls related to substandard maternal care owing a lack of pregnancy-specific considerations and fear of fetal harm. We hereby propose an overview of pregnancy physiology as well as imaging and medication prescription in pregnancy and highlight the need for periodic preconception counseling in reproductive age women.

PULMONARY PHYSIOLOGY IN PREGNANCY

Pregnancy is associated with changes in respiratory physiology that involve the nasopharynx, the lungs, and the chest wall, and often result from hormonal alterations and increasing abdominal distention.

Upper Airway

Mucosa in both the nasopharynx and oropharynx undergoes histologic changes that include increased phagocytic activity, increased mucopolysaccharides, leakage of plasma into the stroma, and glandular hyperactivity.17,18 These changes likely occur in response to estrogen, progesterone, placental growth factor, and interleukins, as well as in response to an effect on histamine receptors.17,19 The histologic changes translate into a mucosa that is edematous and friable, impacting the ease of intubation and nasogastric tube insertion, and increasing the risk of epistaxis.20 In addition, one-fifth of pregnant women develop gestational rhinitis, a diagnosis characterized by nasal congestion that resolves soon after delivery.19

Apart from nasal congestion, other upper airway changes are relevant to the pathogenesis of sleep-disordered breathing, including a decrease in the oropharyngeal junction area and the mean pharyngeal area in pregnant women compared with nonpregnant women.21 Mallampati scores have also been shown to increase during pregnancy22 and 34% more women have Mallampati grade 4 in late pregnancy compared with early pregnancy.22

Chest Wall and Diaphragm

The chest wall undergoes changes during pregnancy as well. Owing to increases in the abdominal component of the chest wall by the third trimester, chest wall volume increases by 4.46 L.23 Chest wall compliance decreases late in pregnancy as a result of increasing uterine size and possibly an increase in breast size, although lung compliance does not change.24,25

In addition, the subcostal angle of the thorax (the angle of the lower ribs at the level of the xiphoid process), increases along with the anterior–posterior and mediolateral measurements and cross-sectional area of the rib cage. However, the total volume of the rib cage remains constant.23 The widening of the subcostal angle occurring early in pregnancy cannot be entirely explained by the enlarging uterus. Accordingly, these changes may partly occur owing to the hormone relaxin, which is known to cause relaxation of the pelvic ligaments in pregnancy as well as remodeling in bones and muscle26–28 and may also cause relaxation of the lower rib cage ligaments.18

The diaphragm moves cranially 1.5 to 4.0 cm during pregnancy.23 Despite the cranial shift of abdominal contents, the thickness of the diaphragm and the excursion of the diaphragmatic dome remain similar to nulliparous women over the course of pregnancy.23 The muscle function of the respiratory system remains normal.29

Lung Function

Spirometry does not change significantly over the course of pregnancy. The forced expiratory volume in 1 second, peak expiratory flow, and the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity remain within normal values throughout pregnancy.30–32 Although studies vary, with some suggesting an increase in forced vital capacity,33 there is likely no significant change in forced vital capacity during pregnancy.31,32,34

Elevation of the diaphragm, decreased outward recoil of the chest wall, and decreased downward tension of the abdomen during pregnancy lead to a 14% to 27% decrease (400–1000 mL) in functional residual capacity (FRC) between the postpartum period and the third trimester, with the percent change varying according to technique.32,35 This decreased in the FRC is exacerbated further in the supine position.18,36 There is also a decrease in expiratory reserve volume of approximately 200 mL29,30,34,35 and a small to nonsignificant decrease in the residual volume.29,30 Total lung capacity, which is a function of FRC and inspiratory capacity, remains the same throughout pregnancy because inspiratory capacity increases at a rate proportional to the decreasing FRC.30,37 Closing capacity, which provides an assessment of small airway closure, is lower during pregnancy compared with the postpartum period.21 There is no change in static lung recoil pressure and lung compliance.30,34,38 The diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide, also known as the transfer factor, is highest in the first trimester and decreases to a lowest mean value between 24 to 27 weeks of gestation before increasing again postpartum.39 Despite the presence of factors that typically increase airway resistance, such as upper airway edema and a decreased FRC, airflow rates remain the same during pregnancy likely owing to hormonally mediated dilatory effects on bronchial smooth muscle late in pregnancy.36,37

The respiratory rate does not change during pregnancy, yet minute ventilation increases by up to 30% to 50% owing to an increase in tidal volumes.31,34,40,41 Compared with nonpregnant women, in whom the tidal volume is mostly a function of diaphragmatic movement, the tidal volume in pregnant women is determined by both diaphragmatic movement and intercostal accessory muscle use.20,35 Hyperventilation in pregnancy occurs in response to increased levels of progesterone, the increased metabolic rate, and increased CO2 production. Progesterone increases the sensitivity to CO2; stimulates regions in the brain responsible for controlling ventilation such as the medulla oblongata, thalamus, and hypothalamus; and increases the peripheral ventilatory response to hypoxia via stimulation of the carotid body.42,43 Estrogen may act synergistically with progesterone, possibly potentiating some of these effects.44 The results of studies examining dead space ventilation in pregnancy have been conflicting. Although physiologic dead space is expected to decrease in pregnancy owing to increases in cardiac output and perfusion of lung apices, dead space ventilation may in fact increase, maintaining a similar dead space to tidal volume ratio to the nonpregnant population.41,45 There is an increase in dead space ventilation, likely owing to an increase in alveolar dead space rather than anatomic dead space, although the mechanism for this change is unclear.18,41 Hyperventilation related to pregnancy leads to decreased Paco2 levels and increased Pao2 levels, with a resulting mild respiratory alkalosis that is renally compensated.30,45

The clinical implications of respiratory physiologic changes include a less patent upper airway, increasing the risk for sleep-disordered breathing, nasal congestion, epistaxis, and a more difficult airway intubation. Changes in upper airways, hormone levels, and gastroesophageal reflux may increase the risk of asthma exacerbations in pregnancy. Immunologic changes may increase the risk46 and the severity of viral infections,47,48 and possibly impact the natural history of inflammatory conditions. The anatomic chest wall changes and the increased oxygen demands may increase the risk for ventilatory insufficiency in patients at risk.

CARDIAC PHYSIOLOGY IN PREGNANCY

Blood Volume

Blood volume increases rapidly around 6 weeks of gestation49 and, in the third trimester, blood volume peaks between 4800 mL in singleton pregnancies and 5800 mL in twin pregnancies, accounting for a 50% increase.50 Red blood cell mass increases by 17% to 40% in response to hormonal influences on erythropoiesis by progesterone, placental chorionic somatomammotropin, and possibly prolactin.51 A simultaneous increase in plasma volume outpaces the increase in red cell mass, thus resulting in lower hemoglobin concentrations, termed physiologic anemia of pregnancy.

Hemodynamics

The heart rate increases gradually over the course of pregnancy, before returning to baseline, 14 to 17 weeks postpartum.52 Cardiac output increases by 30% to 47% over the course of pregnancy, with the most substantial increase early in the first trimester before peaking between 25 and 32 weeks of gestation.53–57 In twin pregnancies, cardiac output is 20% higher as compared with singleton pregnancies.58 Early in gestation, cardiac output is mostly influenced by an increase in stroke volume, whereas later in gestation, the heart rate is the primary driver of increased cardiac output, because the stroke volume remains constant or slightly decreased in the third trimester.56,57 Cardiac output is also influenced by body position—cardiac output decreases in the supine position owing to decreased venous return, which is most decreased in the third trimester.59

Although there is no change in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and central venous pressure, systemic vascular resistance and pulmonary vascular resistance decrease.60 The mean arterial blood pressure decreases early in pregnancy then increases again during the third trimester and postpartum period.52,61

Oxygen uptake and CO2 output increase in the first 8 to 11 weeks of pregnancy and continue to increase over the rest of the pregnancy to a peak of 20% to 30% above baseline near term.20,51,62 In early pregnancy, the increase in oxygen consumption is balanced with an increase in cardiac output to meet the demands during the critical period of organogenesis. Later in pregnancy, oxygen consumption outpaces the increase in cardiac output, resulting in a widening in the arteriovenous oxygen levels. Although total red cell mass increases during pregnancy leading to an increase in oxygen-carrying capacity, the arterial O2 content is actually lower owing to physiologic anemia.40

Thus, cardiovascular physiologic changes may lead to a worsening in hemodynamics in patients with pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, or valvular heart disease. Changes in blood volume, in conjunction with alterations in the balance of oncotic and hydrostatic pressures, increase the risk of pulmonary edema in pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

CHANGES IN PHYSIOLOGY DURING LABOR AND DELIVERY

Physiologic changes within the respiratory and cardiovascular systems during pregnancy are then followed by another series of rapid and significant changes during labor, delivery, and the postpartum period.

Respiratory Physiology during Labor and Delivery

There is dramatic variability in tidal volumes (330–2250 mL) and minute ventilation (7–90 L/min) during labor and delivery.63 Hyperventilation is common during labor and delivery, likely as a result of pain; narcotic analgesics have been shown to decrease hyperventilation during labor and delivery.18,63

Cardiovascular Physiology during Labor and Delivery

Cardiac output increases substantially as a result of both an increase in stroke volume and heart rate during labor, 30% to 50% above baseline at term and 50% above baseline during labor.64,65 This increase in cardiac output is potentiated by an increase in catecholamines and by cyclic autotransfusions from uterine contractions.66,67 In the early postpartum period, there is a further increase in cardiac output of 60% to 80% compared with prelabor levels from an increase in preload with approximately 500 mL of blood owing to release of aortocaval compression by the gravid uterus, diversion away from uteroplacental vascular bed, and mobilization of extracellular fluid.18,51,57,68

Understanding the physiologic changes during labor and delivery can assist clinicians in planning for this event. Most women with mild to moderate respiratory insufficiency tolerate pregnancy and labor and delivery well, with certain modifications. The additional strain on the respiratory system during labor and delivery may place women at a higher risk from increased intrathoracic pressures, hyperventilation, respiratory muscle fatigue, or ventilatory insufficiency. Thus, discussions with the anesthesiology team regarding specific airway intubation strategies or anesthetic considerations in women with sleep-disordered breathing, women with restrictive physiology, or women with significant airway obstruction, for instance, with deliberate plans for the event, is essential. Similarly, the strain on the cardiovascular system and sympathetic activation may increase the risk of cardiovascular complications. The risk of complications can be mitigated with careful planning in collaboration with the obstetric and anesthesiology teams to adapt delivery and pain management strategies while optimizing cardiac output.

Return to Baseline

Pregnancy-related physiologic changes return to baseline over variable timeframes during the postpartum period. In the upper airway, pregnancy rhinitis resolves within 2 weeks of delivery.19

By 24 weeks postpartum, the chest wall returns to baseline; however, the subcostal angle remains 20% larger than at baseline.29 Decompression of the diaphragm and lungs after delivery results in normalization of static lung volumes.18 FRC, which is a function of expiratory reserve volume and residual volume, increases along with expiratory reserve volume in the postpartum period compared with the third trimester of pregnancy.35 Although studies disagree on whether the forced vital capacity increases or remains constant during pregnancy, one study found increases in forced vital capacity that persisted at 6 months postpartum and suggest that changes in the forced vital capacity may be permanent in parous women as compared with nulliparous women.33

In the cardiovascular system, after the significant increase in cardiac output during labor and delivery, cardiac output quickly decreased postpartum65 and returns to the prepregnancy level 2 weeks after delivery.68 Left ventricular wall thickness, which increases along with left ventricular mass during pregnancy,53 is often back to baseline by 24 weeks after delivery.20

RADIOLOGIC TESTING IN PREGNANT WOMEN WITH PULMONARY DISEASES

In a study of 3.5 million pregnancies in the United States and Ontario, Canada, the use of ionizing radiation during the course of pregnancy has increased nearly 4-fold in the United States and 2-fold in Ontario, between 1996 and 2016.69 Although the use of most chest imaging modalities is mostly justifiable in pregnant women for the right indications, understanding the use of imaging studies in pregnancy is key.

Fetal Adverse Effects with Pulmonary Diagnostic Imaging

Two types of fetal adverse effects can arise from ionizing radiation. First, deterministic effects from damage to cell tissue may bear fetal consequences at a given radiation dose threshold.70 These teratogenic effects depend on the dose and gestational age at the time of radiation, and no teratogenicity has been reported with doses of less than 50 mGy, which is well above the current radiation doses used for most routine diagnostic radiologic chest examinations (Table 1).70–72 In the first 2 weeks after conception, fetal loss can occur with exposure to high doses of radiation.71,72 The majority of teratogenic effects take place between 2 and 15 weeks after fertilization.71,73 During organogenesis, between 2 and 8 weeks after conception, congenital skeletal, ocular, and genital anomalies, as well as growth restriction, have been observed.10 Between 8 and 15 weeks after conception, microcephaly and severe intellectual disability have also been reported.72 A low risk of severe intellectual disability may persist between 16 and 25 weeks after conception.72

Table 1.

Estimated ionizing radiation doses per chest imaging

| Type of Examination | Estimated Fetal Dose (mGy) |

|---|---|

| Chest radiograph | 0.0005–0.01 |

| Chest CT scan or CT pulmonary angiography | 0.01–0.66 |

| Low-dose perfusion scintigraphy | 0.1–0.5 |

| Perfusion/ventilation scan | 0.32–0.74 |

Second, stochastic effects from damage to as little as a single cell, can have fetal consequences in the absence of any predictable threshold.70 These effects include oncogenicity with the induction of cancer in childhood and hereditary diseases in future generations.70 The oncogenic risk after exposure to radiation is thought to be proportional to the radiation dose received and is estimated to be significant when occurring after 3 to 4 weeks of fertilization as opposed to before implantation.70 Beyond the first month after conception, oncogenesis does not seem to be influenced by gestational age at the time of radiation.70 In terms of risk estimation, childhood cancer may be doubled with a dose of 25 mGy, as reflected by an increase in absolute excess childhood cancer risk of 1 in 13,000 per mGy in the UK.70 Overall, the lifetime risk of malignancy per 20 mGy of radiation is estimated at 40 per 5000 infants, representing a cumulative incidence of about 0.8%.71 Accordingly, more than 99% of infants are expected to be as healthy as other children after exposure to medically required diagnostic testing during pregnancy.71

Using alternative diagnostic modalities, when feasible, and optimizing the radiation dose via several techniques can minimize fetal risk. Scattered radiations from imaging outside of the abdomen and pelvis represent very low doses and thus negligible fetal risk (see Table 1).71 Measures to minimize the radiation dose received by the fetus include limiting the number of images captured and restricting radiation to the area of interest, as well as improvements in imaging equipment.71 For nuclear medicine procedures, decreased administered activity accompanied by increased radiopharmaceutical excretion, as well as increased scanner efficiency and image reconstitution techniques can further optimize this risk.71 In general terms, most diagnostic chest imaging modalities are justifiable in pregnancy. The involvement of a medical physicist and the radiology department to implement protocol modifications and minimize radiation exposure allow for diagnostic procedures to be performed safely, without delaying or withholding care from this population.

Although iodine-based contrast agents can cross the placental barrier, they have not been associated with teratogenic or oncogenetic effects.71,72,74 Moreover, the theoretic risk of contrast-induced neonatal hypothyroidism has been dismantled by several studies, which included a total of more than 480 neonates of mothers who had received intravenous iodinated contrast for computed tomography (CT) scan testing.75–77 With thyroid testing being part of routine newborn screening in many countries, no additional neonatal measures need to be routinely undertaken after delivery. However, given that pregnancy physiology impacts stroke volume and plasma volume, the dose or protocol of contrast agents may need to be modified to optimize enhancement.

Choosing between Chest Imaging Modalities to Rule Out Pulmonary Embolism

Although both CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) and ventilation perfusion (VQ) scans deliver minimal doses of radiation to the fetus (see Table 1), CTPA delivers a higher dose of radiation to the proliferating breast tissue than does a VQ scan (20–35 mGy for CTPA vs 0.28 mGy for a VQ scan).78 Despite this finding, in a population-based study with longitudinal follow-up, neither a CT scan of the chest nor a VQ scan led to a detectable short-term excess risk of maternal breast cancer.79 In addition, in a systematic review, both imaging modalities were associated with low false-negative rates and comparable nondiagnostic testing rates.80 However, nondiagnostic CTPA testing rates may be considerably decreased by using a protocol adapted to the hemodynamic effects of pregnancy.80 Thus, from a maternal and fetal standpoint, both imaging modalities are reasonable options to rule out pulmonary embolism. VQ single photon emission CT (VQ-SPECT) imaging is another potential diagnostic modality that is thought to have superior diagnostic accuracy to planar VQ scintigraphy in the general population.81 This imaging modality has not been adopted widely. VQ-SPECT scan use has been reported in pregnancy in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism and may offer some advantages. VQ-SPECT scans seem to have the same diagnostic yield as CTPA; however, they are associated with a lower radiation dose to the maternal breasts.82 Because the estimated fetal dose differs by the proximity of the fetus to the radiation source in imaging studies such as CT scans, a recent study found that, in the first and second trimesters, the radiation dose was lower to the fetus when using CTPA compared with a VQ-SPECT scan, but higher in the third trimester for CTPA.83

The lack of ionizing radiation with MRI is an advantage compared with other imaging modalities. MRI has been used for fetal imaging without an apparent negative impact.84 Although an MRI does not expose fetuses to ionizing radiation, the safety of gadolinium-based contrast media has not been well-established. Owing to its high molecular weight, only a small fraction of this contrast medium is believed to pass from maternal blood to fetal tissue.85 However, the total duration of fetal exposure to the media is not known because gadolinium excreted into amniotic fluid eventually reenters the fetal circulation.72,85 In a case series of 26 women who received either periconceptional or first trimester gadolinium-based contrast media with an MRI examination, 23 had a term delivery, 2 had a miscarriage, and 1 patient underwent elective abortion.86 Among women with term delivery, 1 patient had a baby with an intracranial hemangioma.86 Owing to this small sample size, firm conclusions could not be drawn. The largest population-based study on adverse effects from gadolinium contrast media included more than 1 million pregnancies in the province of Ontario in Canada.87 The adjusted risk ratio for a composite of stillbirths and neonatal death among women exposed to gadolinium was 3.70 (95% confidence interval, 1.55–8.85) when compared with women unexposed to any MRI testing.87 Moreover, despite no increased risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in the newborn, investigators found a slightly higher risk of rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin conditions in newborns exposed in utero (hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.09–1.69).87 It remains possible that poorer fetal outcomes may have been, in fact, due to residual confounding by indication from the underlying clinical condition leading to imaging by gadolinium-enhanced MRI.88 In light of these results and an absence of better safety data, gadolinium contrast should only be given when truly warranted by maternal indications and is expected to change management, and after appropriate counseling.71,72 Similar to any management decision in pregnancy, a risk assessment of the use of a diagnostic or therapeutic modality examining the risk of the untreated or poorly managed disease against the risk of the procedure or treatment helps to guide clinical management decisions. If used, only gadolinium-based contrast agents associated with the lowest risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis should be administered.75

PRESCRIBING FOR THE PREGNANT AND THE BREASTFEEDING WOMAN

Prescribing in Pregnancy

Prescribing medications in pregnant and lactating women poses a unique challenge for clinicians. Concerns include the potential toxicity of drugs to the fetus and breastfeeding infant, and alterations in pharmacokinetics that may require changes in dosing.89 Despite studies showing an increase in medication use in pregnancy in the United Stgates,90 there is a significant lack of clinical trials and limited understanding of effects of medications on the long-term health of infants and mothers.91 As a result, discontinuing a medication in pregnancy may seem like the safest course. However, untreated or undertreated conditions most often pose a greater risk to the pregnant woman and her baby than medication use.

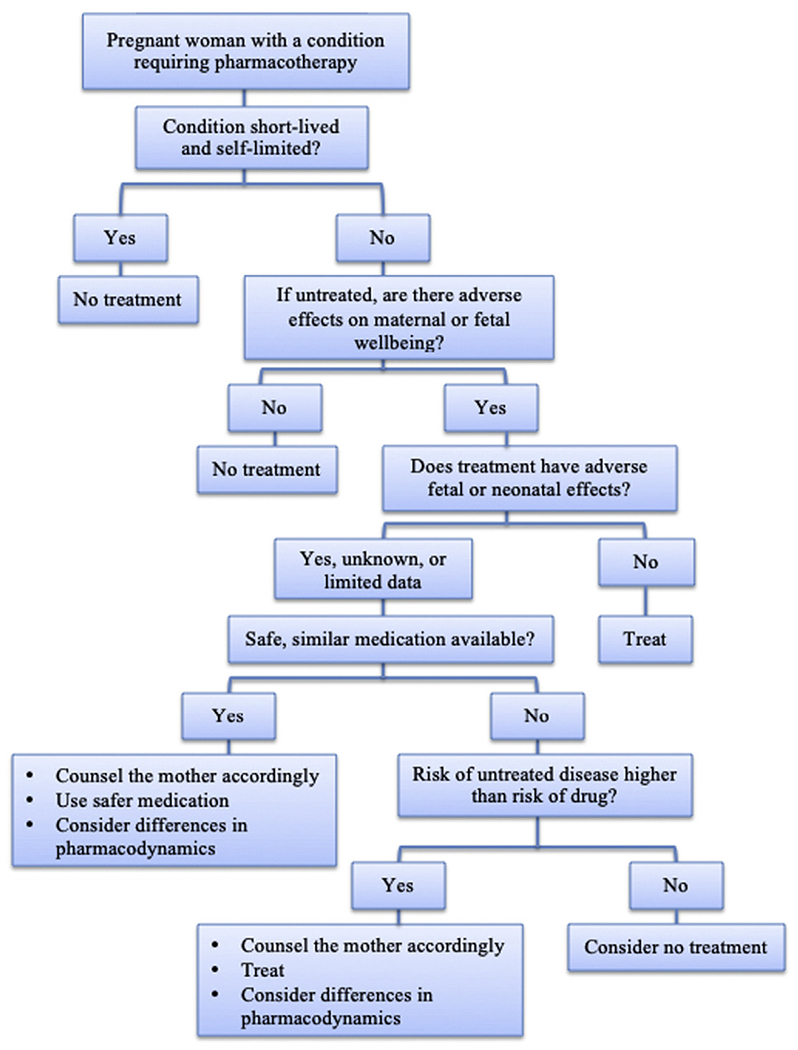

Faced with this dilemma, many clinicians have heavily relied on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug categories for pregnancy (ABCDX). However, in 2015, the FDA retired this system. After a lengthy process of review, the FDA concluded that the letter categories were flawed for several reasons: (1) they were almost exclusively derived from animal data, (2) they were perceived as a simple gradient of risk that failed to differentiate severity and range of adverse outcomes, (3) they failed to address the importance of dose, route, and gestational timing, and (4) they did not consider the indication for the drug or have a mechanism that weighs the risk of the drug against the risk of the untreated condition. In addition, there was no requirement for updating the categories. The conclusion of the FDA was that the pregnancy categories were often misinterpreted and misused. In 2015, the ABCDX categories were replaced by the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule.92 This new ruling requires narrative text that will provide prescribers with relevant information for critical decision-making when treating pregnant or lactating women. The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule includes a more complete statement of the known risks based on the best available data. The new format will encourage the consideration of the untreated disease, will present animal data in the context of human exposure, and explicitly state when human data are available and when no data are available. The new rule includes 3 categories: (1) pregnancy including labor and birth, (2) lactation, and (3) females and males of reproductive potential. The goal of the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule is to provide prescribers with relevant information for decision-making when treating pregnant or lactating women. In all cases of prescribing in pregnancy, the clinician must weigh the potential risk of medication with the risk of untreated disease (Fig. 1). A shared decision-making approach is important. Clinicians must provide women with accurate safety information about medication use in pregnancy, but also be sensitive to the patients and families’ concerns about risk of medication use in pregnancy.

Fig. 1.

Approach to pharmacotherapy for the pregnant and breastfeeding woman. (Adapted from Miller, M. A., Mehta, N., Clark-Bilodeau, C., & Bourjeily, G. (2020). Sleep Pharmacotherapy for Common Sleep Disorders in Pregnancy and Lactation. Chest, 157(1), 184–197.With permission.)

Useful online resources for information on drugs in pregnancy include Reprotox93 and MotherToBaby.94

Prescribing in Breastfeeding Women

A large body of medical literature has long established that human milk is the best nutrition for infants. Exclusive breastfeeding for a minimum of 6 months provides many short- and long-term benefits to the mother and her infant.95 However, women are often advised to discontinue breastfeeding when medications are prescribed. Although nearly all medications transfer into human milk to some degree, it is almost always in very low amounts and is unlikely to result in a clinically relevant dose to the infant. The American Academy of Pediatrics advises that “most drugs likely to be prescribed to the nursing mother should have no effect on milk supply or on infant well-being.”96

Factors that influence risk to the breastfed infant include the concentration of drug in the breastmilk, as well as the bioavailability, lipid solubility, and protein binding of the drug.97 The mother’s plasma level is the most important factor impacting the level of the drug in breastmilk. The concentration in breastmilk will increase and decrease as a function of the maternal plasma level. A few drugs may be trapped in the breastmilk owing to the low pH of human milk. Drugs with a high pKa (such as barbiturates) are generally avoided if an alternative drug is available. Iodines are pumped into breastmilk in a similar way that iodine is pumped into the thyroid.98

Once a drug has entered the breastmilk and has been ingested by the infant, the bioavailability of the drug plays a significant role in determining the final dose in the infant. Drugs may be destroyed by proteolytic enzymes and acids in the infant’s gut or fail to be absorbed through the gut wall or rapidly picked up by the liver, all of which generally leads to a decreased effect of the drug on the infant.

Drugs with high lipid solubility transfer into milk in higher concentrations. For example, central nervous system–active drugs nearly always have the unique characteristics required to enter milk. Although significant levels can be expected in milk, they are nearly always still subclinical.

Protein binding also plays a role in transfer into breastmilk. It is the unbound portion of the drug that transfers; therefore, drugs with high maternal protein binding (warfarin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) have low milk levels.

In addition to the characteristics of the drug, the timing of the exposure and infant characteristic play a role in decisions about drug use during breastfeeding. During the first 72 hours postpartum, large gaps between mammary alveolar cells allow most drugs to transfer easily into breastmilk. By the end of the first week postpartum, prolactin levels increase and cause the alveolar cells to swell, closing the intracellular gaps and reducing transfer. Although drugs may penetrate at higher levels during the early colostrum production period, the minimal volume of colostrum produced means the absolute dose transferred is generally quite low. Infant characteristics such as age and health status should also be considered. A premature or medically unstable infant may be susceptible to even low doses of a medication.99

Helpful references for medications in breastfeeding include Thomas Hale’s Medication and Mother’s Milk100 and the Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed), a free online database from the National Library of Medicine.101

PRECONCEPTION COUNSELING

Aside from caring for women with lung disease during pregnancy, preparing women with chronic lung disease for a successful pregnancy is just as important. An American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion piece defined the goal of prepregnancy care as one that decreased the risk of adverse health effects for the woman, the fetus, and the neonate by working with the patient to optimize her health, provide education about a healthy pregnancy, and address modifiable risk factors.102 Because the health of an individual varies throughout their lifespan, preconception counseling needs to occur multiple times during the course of a woman’s reproductive years. Women should be counseled to seek care ideally before they attempt to get pregnant, and as soon as they find out they are pregnant. This effort will aid in devising a monitoring plan for the course of pregnancy and the postpartum period.

A multinational survey on family planning for women of childbearing age has shown that medical specialists often fail to adequately communicate with and support women with chronic conditions, citing suboptimal communication between specialists, leading to inconsistent advice and information.103

Preconception counseling is a key feature of the care of a woman of reproductive age with chronic lung disease. Reproductive age women with chronic lung disease who are sexually active, have a partner, and those who have children need to have conversations regarding the possibility of a pregnancy and the implications of pregnancy.104 Because nearly one-half of all pregnancies are unplanned and given that control of chronic lung disease may vary over the years, these conversations need to occur repeatedly throughout the reproductive years. A significant relay of information is necessary when it comes to meeting the challenges related to pregnancy and parenting. The aim of preconception counseling would be to assist in planning an optimal timing of pregnancy and to improve management before conception and throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period.105 Women may prefer preconception conversations to happen in the presence of a partner.

Preconception counseling in women with chronic illnesses should focus on the importance of avoiding unplanned pregnancies and the potential maternal and fetal risks associated with such pregnancies.102 Counseling on and routinely visiting birth control methods with these women can help to prevent unplanned pregnancies. In general, women with active disease and disease that is poorly controlled should practice effective birth control until the condition is better controlled.

Risk assessment includes the examination of the risk of the chronic disease on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes, as well as the risks of the pregnancy on the chronic condition.106 Understanding and counseling patients on the risk of worsening of certain common conditions such as asthma or sleep apnea, or rare conditions such as pulmonary hypertension or lymphangioleiomyomatosis during pregnancy can paint a clearer picture of expectations for the pregnant woman and assist her in making informed decisions about management and medication choices.102 In other circumstances, reviewing the risk of recurrence of a condition such as venous thromboembolism and the implications of that risk such as the use of subcutaneous injections for the duration of pregnancy and a planned labor and delivery help to set the appropriate expectations with patients and their families. Because pregnancy physiology may modify or worsen certain preexisting conditions, women must be made aware that the frequency of monitoring, testing, and follow-up visits will likely increase in pregnancy as well. For instance, women with cystic fibrosis or asthma likely need more frequent monitoring during the course of pregnancy, although no specific guidelines exist for the use of pulmonary function testing in pregnancy. In contrast, women need to be informed of the risk of a treated or untreated chronic condition on the health of the pregnancy and the fetus and newborn. This understanding of risk can guide decision-making regarding therapy choices.

Another aim of preconception counseling is to review the risk of medications prescribed to control or treat a chronic condition.102,107 Ideally, women would enter pregnancy on medications that are nonteratogenic. However, this scenario may not occur for various reasons. Given the status of pregnancy drug trials and the systematic exclusion of pregnant women from many interventional trials, many drugs remain poorly examined for safety and efficacy in pregnancy. Indeed, in 2011 and 2012, pregnant women were excluded from 95% of phase IV interventional industry-sponsored trials.108 Further, 98% of the 172 drugs approved in the United States between 2000 and 2010 lacked data or had insufficient data to determine the risk of developmental toxicity in humans.109 For this reason, many first-line medications may not be the safest alternative in pregnancy.110 To complicate matters further, nearly 85% of all couples will get pregnant within 1 year if they have regular sex and do not use contraceptive methods111; however, the time span from intention to conception varies by couple. Hence, deciding on the optimal timing to withdraw a medication that is treating and keeping a chronic condition optimally controlled in anticipation of pregnancy may be challenging.

Genetic counseling should also be considered in women with a respiratory genetic disorder so that proper evaluation be performed and the expectant mother and her family are informed about potential risk of transmission of the disorder and clarify expectations, as well as the implications for the management at the time of delivery and in neonatal to adult life.

Women with respiratory diseases anticipating or planning pregnancy should also receive general recommendations regarding lifestyle changes that could improve their overall health.102 Smoking is associated with a higher risk of infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, growth restriction, and preterm birth, among other complications.112 Most animal studies suggest that electronic cigarette smoking is associated with potential danger to the developing fetus primarily because nicotine consumption has multiple effects on the immune system, neural development, lung function, and cardiac function.113,114 Hookah smoking, also known as waterpipe smoking, has been associated with adverse obstetric outcomes such as low birth-weight,115–117 low Apgar scores,117,118 and pulmonary complications at birth. Smoking cessation before pregnancy would be ideal and likely yields the greatest benefits to the fetus.119 However, smoking cessation at any time during pregnancy still bears significant benefits.120 In addition to obesity-related pulmonary complications, women with obesity have an increased risk of pregnancy-related complications, including higher rates of gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, macrosomia, venous thromboembolism, and congenital anomalies.121 Because weight loss is not recommended during pregnancy, women with obesity should be advised to seek weight management recommendations before conception.

SUMMARY

The management of pregnant women with chronic lung diseases should be performed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a pulmonologist, an obstetric medicine physician, and a specialist obstetrician in high-risk conditions, with open communications with the primary care physician, as well as an anesthesiologist in later pregnancy. Involving the patient and her family in the decision-making is key to setting expectations and clarifying the intensity and frequency of monitoring.

KEY POINTS.

Respiratory conditions are common in pregnancy and may contribute to significant maternal morbidity.

Pregnancy is associated with dynamic and profound physiologic changes that impact disease presentation, outcomes, and management.

Most chest diagnostic studies are justified in pregnancy with nuances.

Pharmacotherapy needs to weigh the impact of the untreated condition on the health of the mother and her unborn child against the risk of a medication.

Preconception counseling is a key component of the care of reproductive age women and needs to be performed periodically during a woman’s reproductive years.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

Withholding diagnostic studies or therapeutic interventions in pregnant women may be more harmful than administering them.

Preconception counseling may be an opportunity to plan a future pregnancy and optimize the care of women during pregnancy.

Funding:

Dr G. Bourjeily has received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) R01HL130702 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) R01HD078515.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clifton VL, Engel P, Smith R, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancies complicated by asthma in an Australian population. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;49:619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon HL, Triche EW, Belanger K, et al. The epidemiology of asthma during pregnancy: prevalence, diagnosis, and symptoms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006;26:29–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendola P, Laughon SK, Männistö TI, et al. Obstetric complications among US women with asthma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:127.e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bin YS, Cistulli PA, Ford JB. Population-based study of sleep apnea in pregnancy and maternal and infant outcomes. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12:871–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourjeily G, Danilack VA, Bublitz MH, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in pregnancy is associated with adverse maternal outcomes: a national cohort. Sleep Med 2017;38:50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bublitz MH, Monteiro JF, Caraganis A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in gestational diabetes: a pilot study of the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Clin Sleep Med 2018;14: 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung AM, Wilson DL, Lappas M, et al. Effects of maternal obstructive sleep apnoea on fetal growth: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e68057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reutrakul S, Zaidi N, Wroblewski K, et al. Interactions between pregnancy, obstructive sleep apnea, and gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:4195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm [Accessed September 8, 2020].

- 10.Rojas-Suarez J, Bello-Munoz C, Paternina-Caicedo A, et al. Maternal mortality secondary to acute respiratory failure in Colombia: a population-based analysis. Lung 2015;193:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle TJ, Goodin K, Hamilton JJ. Maternal and neonatal outcomes among pregnant women with 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) illness in Florida, 2009-2010: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e79040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sliwa K, van Hagen IM, Budts W, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: data from the Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18:1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bublitz MH, Bourjeily G. Sleep disordered breathing in pregnancy and adverse maternal outcomes-a true story? US Respir Pulm Dis 2017;2:19–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourjeily G, Danilack VA, Bublitz MH, et al. Maternal obstructive sleep apnea and neonatal birth outcomes in a population based sample. Sleep Med 2020;66:233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberger SE, Weiss ST, Cohen WR, et al. Pregnancy and the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980; 121:559–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourjeily G, Levinson A. Pulmonary disease and critical illness in pregnancy. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2017;38:121–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philpott CM, Conboy P, Al-Azzawi F, et al. Nasal physiological changes during pregnancy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2004;29:343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Respiratory physiology in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med 2011;32:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellegard EK. The etiology and management of pregnancy rhinitis. Am J Respir Med 2003;2:469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crapo RO. Normal cardiopulmonary physiology during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1996;39:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izci B, Vennelle M, Liston WA, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and upper airway size in pregnancy and post-partum. Eur Respir J 2006;27:321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilkington S, Carli F, Dakin MJ, et al. Increase in Mallampati score during pregnancy. Br J Anaesth 1995;74:638–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LoMauro A, Aliverti A, Frykholm P, et al. Adaptation of lung, chest wall, and respiratory muscles during pregnancy: preparing for birth. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2019;127:1640–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx GF, Murthy PK, Orkin LR. Static compliance before and after vaginal delivery. Br J Anaesth 1970;42:1100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell LA, Klocke RA. Implications for the pregnant patient. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163: 1051–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacLennan AH. The role of relaxin in human reproduction. Clin Reprod Fertil 1983;2:77–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unemori EN, Amento EP. Relaxin modulates synthesis and secretion of procollagenase and collagen by human dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 1990;265:10681–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehghan F, Haerian BS, Muniandy S, et al. The effect of relaxin on the musculoskeletal system. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24:e220–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Contreras G, Gutierrez M, Beroiza T, et al. Ventilatory drive and respiratory muscle function in pregnancy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen D, Webb KA, Davies GA, et al. Mechanical ventilatory constraints during incremental cycle exercise in human pregnancy: implications for respiratory sensation. J Physiol 2008;586:4735–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolarzyk E, Szot WM, Lyszczarz J. Lung function and breathing regulation parameters during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2005;272:53–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Rio F, Pino-Garcia JM, Serrano S, et al. Comparison of helium dilution and plethysmographic lung volumes in pregnant women. Eur Respir J 1997;10:2371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grindheim G, Toska K, Estensen ME, et al. Changes in pulmonary function during pregnancy: a longitudinal cohort study. BJOG 2012; 119: 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAuliffe F, Kametas N, Costello J, et al. Respiratory function in singleton and twin pregnancy. BJOG 2002;109:765–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilroy RJ, Mangura BT, Lavietes MH. Rib cage and abdominal volume displacements during breathing in pregnancy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;137: 668–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourjeily G, Mazer J, Levinson A. Chapter 97: pulmonary disorders and pregnancy. In: Grippi MA, Elias JA, Fishman JA, et al. , editors. Fishman’s pulmonary diseases and disorders. 5th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015. p. 1479–96. [Google Scholar]

- 37.LoMauro A, Aliverti A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy: physiology masterclass. Breathe (Sheff) 2015;11:297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gee JB, Packer BS, Millen JE, et al. Pulmonary mechanics during pregnancy. J Clin Invest 1967;46: 945–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milne JA, Mills RJ, Coutts JR, et al. The effect of human pregnancy on the pulmonary transfer factor for carbon monoxide as measured by the single-breath method. Clin Sci Mol Med 1977;53:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bobrowski RA. Pulmonary physiology in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010;53:285–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pernoll ML, Metcalfe J, Kovach PA, et al. Ventilation during rest and exercise in pregnancy and postpartum. Respir Physiol 1975;25:295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen D, Wolfe LA, Slatkovska L, et al. Effects of human pregnancy on the ventilatory chemoreflex response to carbon dioxide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005;288:R1369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bayliss DA, Millhorn DE. Central neural mechanisms of progesterone action: application to the respiratory system. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1992; 73:393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hannhart B, Pickett CK, Moore LG. Effects of estrogen and progesterone on carotid body neural output responsiveness to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1990;68:1909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Templeton A, Kelman GR. Maternal blood-gases, PAo2–Pao2), physiological shunt and VD/VT in normal pregnancy. Br J Anaesth 1976;48:1001–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esmonde TF, Herdman G, Anderson G. Chicken-pox pneumonia: an association with pregnancy. Thorax 1989;44:812–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosby LG, Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in pregnancy: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:10–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA 2010;303:1517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hytten FE, Paintin DB. Increase in plasma volume during normal pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1963;70:402–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pritchard JA. Changes in the blood volume during pregnancy and delivery. Anesthesiology 1965;26:393–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouzounian JG, Elkayam U. Physiologic changes during normal pregnancy and delivery. Cardiol Clin 2012;30:317–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahendru AA, Everett TR, Wilkinson IB, et al. A longitudinal study of maternal cardiovascular function from preconception to the postpartum period. J Hypertens 2014;32:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mabie WC, DiSessa TG, Crocker LG, et al. A longitudinal study of cardiac output in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 170: 849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vered Z, Poler SM, Gibson P, et al. Noninvasive detection of the morphologic and hemodynamic changes during normal pregnancy. Clin Cardiol 1991;14:327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bader RA, Bader ME, Rose DF, et al. Hemodynamics at rest and during exercise in normal pregnancy as studies by cardiac catheterization. J Clin Invest 1955;34:1524–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robson SC, Hunter S, Boys RJ, et al. Serial study of factors influencing changes in cardiac output during human pregnancy. Am J Physiol 1989;256: H1060–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanghavi M, Rutherford JD. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Circulation 2014;130:1003–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kametas NA, McAuliffe F, Krampl E, et al. Maternal cardiac function in twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:806–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeomans ER, Gilstrap LC 3rd. Physiologic changes in pregnancy and their impact on critical care. Crit Care Med 2005;33:S256–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark SL, Cotton DB, Lee W, et al. Central hemodynamic assessment of normal term pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:1439–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rebelo F, Farias DR, Mendes RH, et al. Blood pressure variation throughout pregnancy according to early gestational BMI: a Brazilian cohort. Arq Bras Cardiol 2015;104:284–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gazioglu K, Kaltreider NL, Rosen M, et al. Pulmonary function during pregnancy in normal women and in patients with cardiopulmonary disease. Thorax 1970;25:445–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cole PV, Nainby-Luxmoore RC. Respiratory volumes in labour. Br Med J 1962;1:1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fujitani S, Baldisseri MR. Hemodynamic assessment in a pregnant and peripartum patient. Crit Care Med 2005;33:S354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robson SC, Dunlop W, Boys RJ, et al. Cardiac output during labour. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:1169–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee W, Rokey R, Miller J, et al. Maternal hemodynamic effects of uterine contractions by M-mode and pulsed-Doppler echocardiography. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:974–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nisell H, Hjemdahl P, Linde B. Cardiovascular responses to circulating catecholamines in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Clin Physiol 1985;5:479–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hunter S, Robson SC. Adaptation of the maternal heart in pregnancy. Br Heart J 1992;68:540–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kwan ML, Miglioretti DL, Marlow EC, et al. Trends in medical imaging during pregnancy in the United States and Ontario, Canada, 1996 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e197249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Health Protection Agency, The Royal College of Radiologists and the Royal College of Radiographers. Protection of pregnant patients during diagnostic medical exposures to ionising radiation: Health Protection Agency, Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards. 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/advisory_bodies/impact_measurement_taskforce/meetings/prevalence_survey/imaging_regnant_hpa.pdf [Accessed October 12, 2020].

- 71.American College of Radiology, Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. Manual on contrast media. version 10.3 2017. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual [Accessed October 12, 2020].

- 72.Committee Opinion No. 723: guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gjelsteen AC, Ching BH, Meyermann MW, et al. CT, MRI, PET, PET/CT, and ultrasound in the evaluation of obstetric and gynecologic patients. Surg Clin North Am 2008;88:361–90, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Puac P, Rodriguez A, Vallejo C, et al. Safety of contrast material use during pregnancy and lactation. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2017;25:787–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bourjeily G, Chalhoub M, Phornphutkul C, et al. Neonatal thyroid function: effect of a single exposure to iodinated contrast medium in utero. Radiology 2010;256:744–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kochi MH, Kaloudis EV, Ahmed W, et al. Effect of in utero exposure of iodinated intravenous contrast on neonatal thyroid function. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2012;36:165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rajaram S, Exley CE, Fairlie F, et al. Effect of antenatal iodinated contrast agent on neonatal thyroid function. Br J Radiol 2012;85:e238–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan WS, Rey E, Kent NE, et al. Venous thromboembolism and antithrombotic therapy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2014;36:527–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burton KR, Park AL, Fralick M, et al. Risk of early-onset breast cancer among women exposed to thoracic computed tomography in pregnancy or early postpartum. J Thromb Haemost 2018;16: 876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ridge CA, Mhuircheartaigh JN, Dodd JD, et al. Pulmonary CT angiography protocol adapted to the hemodynamic effects of pregnancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:1058–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gutte H, Mortensen J, Jensen CV, et al. Comparison of V/Q SPECT and planar V/Q lung scintigraphy in diagnosing acute pulmonary embolism. Nucl Med Commun 2010;31:82–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gruning T, Mingo RE, Gosling MG, et al. Diagnosing venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Br J Radiol 2016;89:20160021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rafat Motavalli L, Hoseinian Azghadi E, Miri Hakimabad H, et al. Pulmonary embolism in pregnant patients: assessing organ dose to pregnant phantom and its fetus during lung imaging. Med Phys 2017;44:6038–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document for safe MR practices: 2007. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:1447–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Webb JA, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, et al. The use of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media during pregnancy and lactation. Eur Radiol 2005;15: 1234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Santis M, Straface G, Cavaliere AF, et al. Gadolinium periconceptional exposure: pregnancy and neonatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Bharatha A, et al. Association between MRI exposure during pregnancy and fetal and childhood outcomes. JAMA 2016;316: 952–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Potts J, Lisonkova S, Murphy DT, et al. Gadolinium magnetic resonance imaging during pregnancy associated with adverse neonatal and post-neonatal outcomes. J Pediatr 2017;180:291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koren G, Pariente G. Pregnancy- associated changes in pharmacokinetics and their clinical implications. Pharm Res 2018;35:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976-2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:51.e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Illamola SM, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Costantine MM, et al. Inclusion of pregnant and breastfeeding women in research - efforts and initiatives. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:215–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.US Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling 2014. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/90279/download [Accessed October 14, 2020]. [PubMed]

- 93.Reproductive Toxicology Center. Available at: www.reprotox.org [Accessed October 20, 2020].

- 94.MotherToBaby. Available at: https://mothertobaby.org [Accessed October 20, 2020].

- 95.Bartick MC, Schwarz EB, Green BD, et al. Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:e12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 2001;108:776–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016; 100:42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mattsson S, Johansson L, Leide Svegborn S, et al. Annex D. Recommendations on breast-feeding interruptions. ICRP publication 128 In: Clement CH, Hamada N, editors. Annals of the ICRP. Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals: a compendium of current information related to frequently used substances: the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 2015. p. 7–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Newton ER, Hale TW. Drugs in breast milk. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015;58:868–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hale TW. Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk (TM) 2021: a manual of lactational pharmacology. New York: Springer Pub Co Inc; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 101.National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/ [Accessed October 14, 2020].

- 102.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762: prepregnancy counseling. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chakravarty E, Clowse ME, Pushparajah DS, et al. Family planning and pregnancy issues for women with systemic inflammatory diseases: patient and physician perspectives. BMJ Open 2014;4: e004081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wexler ID, Johannesson M, Edenborough FP, et al. Pregnancy and chronic progressive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175: 300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Skogsdal Y, Fadl H, Cao Y, et al. An intervention in contraceptive counseling increased the knowledge about fertility and awareness of preconception health-a randomized controlled trial. Ups J Med Sci 2019;124:203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care–United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR preconception care work group and the select panel on preconception care. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lanik AD. Preconception counseling. Prim Care 2012;39:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shields KE, Lyerly AD. Exclusion of pregnant women from industry-sponsored clinical trials. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:1077–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Adam MP, Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2011;157c:175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cox M, Whittle MJ, Byrne A, et al. Prepregnancy counselling: experience from 1,075 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:873–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Trussell J, Wynn LL. Reducing unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception 2008; 77:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Einarson A, Riordan S. Smoking in pregnancy and lactation: a review of risks and cessation strategies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Whittington JR, Simmons PM, Phillips AM, et al. The use of electronic cigarettes in pregnancy: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2018;73: 544–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Glover M, Phillips CV. Potential effects of using non-combustible tobacco and nicotine products during pregnancy: a systematic review. Harm Reduct J 2020; 17:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tamim H, Yunis KA, Chemaitelly H, et al. Effect of narghile and cigarette smoking on newborn birth-weight. BJOG 2008;115:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bachir R, Chaaya M. Maternal smoking: determinants and associated morbidity in two areas in Lebanon. Matern Child Health J 2008;12:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nuwayhid IA, Yamout B, Azar G, et al. Narghile (hubble-bubble) smoking, low birth weight, and other pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rachidi S, Awada S, Al-Hajje A, et al. Risky substance exposure during pregnancy: a pilot study from Lebanese mothers. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2013;5:123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Murin S, Rafii R, Bilello K. Smoking and smoking cessation in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med 2011;32: 75–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xaverius PK, O’Reilly Z, Li A, et al. Smoking cessation and pregnancy: timing of cessation reduces or eliminates the effect on low birth weight. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:1434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Poston L, Caleyachetty R, Cnattingius S, et al. Preconceptional and maternal obesity: epidemiology and health consequences. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:1025–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Committee Opinion No. 723 summary: guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:933–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Leung AN, Bull TM, Jaeschke R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline: evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:1200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]