In PNAS, Peters et al. (1) reevaluate various archaeological reports of chicken remains found at more than 600 sites in 89 countries. The identified chicken bones unearthed in central Thailand were dated to 1650–1250 BC, providing direct evidence for the recent domestication of chickens. While we appreciate the integration of multiple analyses to reveal Asian agricultural civilization, we have concerns regarding the origins of domestic chickens.

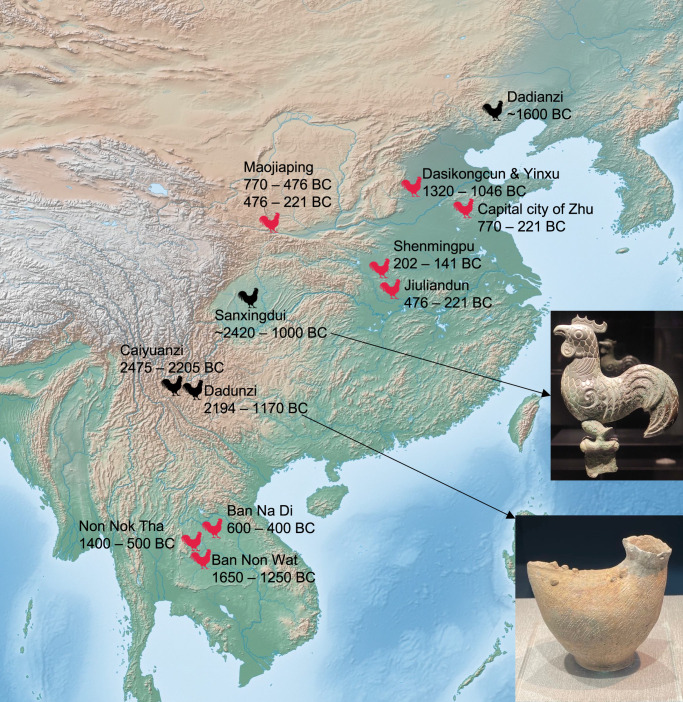

Although seven archaeological sites dated within the 1320–141 BC range in central and northern China were identified with chicken remains (Fig. 1), several important sites in China were not reevaluated by Peters et al. (1). Notably, the Inner Mongolian Dadianzi site (around 1600 BC) (Fig. 1), known to contain chicken, dog, and pig bones (2), was not referenced. More importantly, archeological sites in southwestern China (especially Yunnan), inferred as a partial region of the chicken domestication center based on genomic analysis (3), were excluded, suggesting that a key piece of the chicken domestication puzzle is missing. Chicken bones have also been excavated from Neolithic sites at Caiyuanzi (2475–2205 BC) (4) and Dadunzi (2194–1170 BC) (5) in Yunnan (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Furthermore, chicken-like pottery has been found at the Dadunzi site and exhibits characteristics similar to hens rather than red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) (Fig. 1). A complete bronze cock-like statue has also been discovered at the Sanxingdui site in Sichuan (around 2420–1000 BC) (Fig. 1). These artifacts indicate likely contact between humans and chickens.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of chicken remains and chicken-like artifacts. Archaeological sites reevaluated by Peters et al. (1) are noted in red, and newly referenced sites are in black (see Table 1 for detailed information). Time scales are indicated for archaeological sites. Dasikongcun and Yinxu sites are close and noted in one label. Different tombs of the Maojiaping site are also shown as one label. Lower-bound time scale (1150–1000 BC) for Sanxingdui site was retrieved from an online report (13 June 2022) (https://www.sxd.cn/#/news/messageImg/935?name=news). Photos of bronze cock and chicken-like pottery were taken by J.-L.H. at Sanxingdui Museum and M.-S.P. at Yunnan Provincial Museum, respectively. Map was obtained from the Natural Earth public domain map dataset (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/).

Table 1.

Chicken remains and chicken-like artifacts found in southwestern China

| Site | Location | Material | Notes | Site age | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caiyuanzi | Yongren, Yunnan | Bone | Not figured | 4290 ± 135 BP | (4) |

| Dadunzi* | Yuanmou, Yunnan | Bone and pottery | Tarsometatarsus not figured | 3210 ± 90 BP | (5) |

| 4,139–3928 BP | (6) | ||||

| 4144–3880 BP | (6) | ||||

| Sanxingdui | Guanghan, Sichuan | Bronze cock | 4260 ± 110 BP | (8) | |

| 3990 ± 80 BP | (9) | ||||

| 3765 ± 80 BP | (10) |

*Dadunzi site is discussed in ref. 7.

Peters et al. (1) simplify the time scales for chicken remains into lower limits in their figure 2. However, such an approach should be treated with caution, given that most chicken remains were not directly dated and that there are limitations and uncertainties in predepositional/postdepositional processes (1). Clearly, the time scales for sites with chicken remains and chicken-like artifacts across East and Southeast Asia overlapped, at least partially, between 1600 and 1200 BC (Fig. 1), suggesting an early dispersal of chickens. Thus, the domestication of chickens likely predates archaeological evidence from central Thailand (1650–1250 BC). Indeed, the appearance of millet and rice farming in southwestern China occurred earlier than that in Southeast Asia (6). Southwestern China is also home to the red junglefowl subspecies G. gallus spadiceus (the main ancestor of domestic chicken) and G. gallus jabouillei (1, 3). Therefore, contact between ancient agriculturalists and red junglefowl is expected to have occurred earlier than in Southeast Asian regions, such as Thailand.

In addition, Peters et al. (1) propose that the domestication of chickens was associated with bamboo-growing habitat. However, such a conclusion should be made with caution, as the cited field study was restricted to the Kanchanaburi Province in Thailand during February and March 1963. Apparently, contact between humans and red junglefowl occurred in various habitats on the edges of jungles. Expanded international collaboration, especially with archaeologists and zoologists from China and Southeast Asia, is warranted to improve our understanding of the early origins and dispersal of chickens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Feng Gao from the Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Jing Yuan from the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, for confirming and discussing relevant data. This work was supported by grants from the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2019QZKK050 to M.-S.P.) and the Chinese government’s contribution to CAAS-ILRI Joint Laboratory on Livestock and Forage Genetic Resources in Beijing (2022-YWF-ZX-02 to J.-L.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Peters J., et al. , The biocultural origins and dispersal of domestic chickens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2121978119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan J., Zooarchaeological study on the domestic animals in ancient China. Quaternary Sci. 30, 298–306 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M. S., et al. , 863 genomes reveal the origin and domestication of chicken. Cell Res. 30, 693–701 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Yunnan Archaeological Team of the Institute of Archaeology CASS, Chengdu Municipal Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Museum of Chuxiong Autonomous Prefecture, Yongren Country Cultural Center, Excavation of the Caiyuanzi and Mopandi sites in Yongren, Yunnan, in 2001. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 2, 263–296, 325–328 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Yunnan Provincial Museum, The Neolithic site at Ta-Tun-Tzǔ in Yuan-Mou County, Yunnan Province. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 1, 43–72, 169–178 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Y., Dong G., Yang X., Chen F., A review on the spread of prehistoric agriculture from southern China to mainland Southeast Asia. Sci. China Earth Sci. 63, 615–625 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters J., Lebrasseur O., Deng H., Larson G., Holocene cultural history of red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus) and its domestic descendant in East Asia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 142, 102–119 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbon-14 Laboratory, Department of Archaeology, Peking University, Carbon dating report (10). Cultural Relics (Wenwu) 6, 91–95 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbon-14 Laboratory, Department of Archaeology, Peking University, Carbon dating report (10). Cultural Relics (Wenwu) 11, 91–95 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbon-14 Laboratory, Department of Archaeology, Peking University, Carbon dating report (6). Cultural Relics (Wenwu) 4, 92–96 (1984). [Google Scholar]