Abstract

Background:

Persons with hematologic malignancies have a high symptom burden throughout the illness journey. Coping skills interventions effectively reduce fatigue for other cancer patients. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify if coping interventions can reduce fatigue in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Methods:

A search of PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, APA Psych INFO, Scopus, Cochrane, and non-traditional publications was performed in June 2021 for studies introducing coping interventions for adults with hematological cancers within the past 20 years. The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping was used as a framework with the primary outcome as fatigue. The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence Based Practice Appraisal tool was used for quality appraisal.

Results:

Twelve interventional studies met criteria for inclusion. Four studies significantly reduced fatigue, with an additional three showing a reduction in fatigue. Interventions that utilized both problem and emotion-focused coping were more effective at reducing fatigue compared to interventions that only used emotion or problem-focused coping.

Conclusion:

This systematic review found moderate-strength evidence to support that coping interventions can reduce fatigue, with mixed, but mostly beneficial results. Clinicians caring for patients with hematologic malignancies should consider using coping interventions to reduce fatigue.

Keywords: fatigue, hematologic, cancer, coping, intervention, systematic review

Introduction

The number of patients with hematological cancers, ranging from chronic myelogenous leukemias to diffuse large B-cell lymphomas1 is expected to rise due to new therapies lengthening survival.2 Currently, almost 1.3 million persons in the United States have or are a survivor of a hematologic malignancy.3 Persons with hematologic malignancies undergo complex therapies, including hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), resulting in substantial short-and long-term effects.4 This patient population persistently experiences a high level of symptom burden equivalent to patients with advanced metastatic solid tumor cancers.2,5 Fatigue is an especially prevalent symptom, with 30 – 75% of patients reporting fatigue depending on disease stage and diagnosis.6,7

Persons receiving chemotherapy, during the acute phase of HSCT, in remission, and at the end of life report significant fatigue.8–11 Cancer-related fatigue is multifactorial and can be exacerbated by underlying disease, chemotherapy or radiation treatments, anemia, and other factors.6,7 Moreover, fatigue negatively impacts quality of life and adherence to provider recommendations,12 and increases risk of depression and anxiety for patients with hematologic malignancies.13 Patients with hematologic malignancies receiving palliative care report higher rates of clinically-significant tiredness and higher odds of having fatigue than patients with solid cancer tumors.8

Palliative care teams are integral to managing symptoms including fatigue for persons with cancer. Once underlying physiologic causes of fatigue are addressed (such as anemia), current practice includes pharmacologic (e.g. glucocorticoids, psychostimulants) and nonpharmacologic interventions (e.g. exercise).14 Pharmaceuticals such as methylphenidate may be considered,14 however, a recent narrative review of 17 studies using pharmaceuticals to reduce fatigue in palliative cancer patients found weak evidence to support the use of methylphenidate and corticosteroids.16 Fatigue is less responsive to pharmaceuticals than other symptoms associated with cancer,17 presenting an opportunity to further understand the effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on fatigue.14 While, aerobic exercise can significantly reduce fatigue in breast, prostate, and advanced cancer populations,14,15 moderate exercise may not be feasible for some seriously ill patients receiving palliative care. Understanding implications of psychosocial interventions in the hematologic cancer population may critically inform the way palliative care teams choose to manage fatigue.

Psychosocial interventions, like coping, are one way to reduce negative effects of cancer and treatments,18 with coping consisting of cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage stressors.19 Coping is an integral part of the illness process where the individual implements strategies to cope with, adapt to, and be resilient to the stressor. Coping has been categorized as problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, with problem-focused coping aimed at identifying issues, considering solutions, and selecting a solution, while emotion-focused coping attempts to reduce negative emotions associated with stressors.19 Coping can also be grouped into maladaptive strategies, such as avoidance, or adaptive strategies, like problem-solving.20 Maladaptive coping is correlated to poorer psychological outcomes and increased psychopathology among healthy individuals.21 This relationship extends to patients with breast and other cancers: maladaptive coping predicts increased distress, anxiety, depression, and poorer quality of life in patients.22,23

Coping has been extensively studied in solid cancers, with findings demonstrating that adaptive coping skills reduce fatigue.24,25 The effects of coping on fatigue in the smaller, but distinctly different, hematological cancer population, remains under-examined. Though hematologic malignancies are heterogenous depending on disease type, there are many similarities in symptom burden5 and treatment approaches, for instance, use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.26 In effect, fatigue is one of the most common and persistent symptoms for patients with hematologic malignancies throughout their illness journey, impacting their day to day life.6,27 Thus, the aim of this systematic review is to determine if coping skills interventions are effective at reducing fatigue of adult patients with hematological cancers. The secondary aim of this study is to determine which coping interventions may be most effective at reducing fatigue in the adult hematologic cancer population.

Methods

To address the study aims, we conducted a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Narrative synthesis is used due to the heterogeneous nature of the study designs and diverse methodologies28, including mixed method convergent single case experiments29 and pilot randomized controlled trials.30 The review seeks to assess coping skills and fatigue in the adult hematological cancer population. An outline of the review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and was published on the PROSPERO website on July 25th, 2021, under the title: “The Effect of Coping Skills on Symptoms of Patients with Hematological Malignancies.”

Definitions and Framework

The review was guided by the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC) by Lazarus and Folkman as a framework, which also guided study definitions and search terms. First, the definition includes “adaptation” and “resilience” as they both operate in similar ways to coping.31,32 Adaptation refers to management of stressors, while resilience specifically refers to the ability to adapt and grow positively from stressful events. The inclusion of adaptation and resilience aligns with the National Cancer Institute’s definition of coping skills as “methods a person uses to deal with stressful situations.”33 Terms excluded from this review’s coping definition are “self-care” and “self-management.” These typically refer to disease-controlling or health management strategies: While there are similarities between self-care strategies and coping skills, there can be significant differences in their purpose and intention. Coping occurs in reaction to a stressor, while self-care may occur during a healthy, non-stressed state.31 Please see Table 1 for a list of definitions utilized in this review.

Table 1:

Definitions for Terms included in this Review

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Coping | “Constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and / or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, p. 141, 1984) |

| Resilience | “Dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000) |

| Adaptation | Transactional and dynamic process between a person and the environment in managing demands and stressors, especially regarding a chronic condition or illness (Lazarus, 1974) |

| Self-care | The practice of activities that an individual initiates and performs on his or her own behalf to maintain life, health, and well-being (Orem, 2003) |

| Self-management | “Engaging in a health promoting activity such as exercise or is living with a chronic disease such as asthma, he or she is responsible for day-to-day management” and encompasses “behavioral interventions and healthful behaviors” (Lorig & Holman, 2003). |

| Self-efficacy | Perceived capability to enact a certain behavior, part of the self-evaluative cognitive process, derived from Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Benight & Cieslak, 2011) |

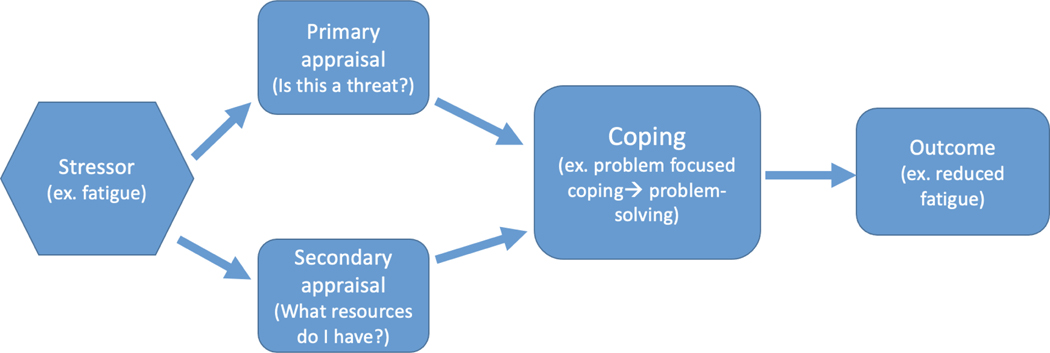

Studies evaluating cancer patients’ coping have also used the TMSC and found cancer diagnoses and treatments are significant stressors.23,34,35 The stressor may encompass the patient’s symptoms, diagnosis, or treatment, followed by the patient’s primary and secondary appraisal of the stressor, and subsequent coping. The reduction, control, or mitigation of fatigue may indicate the efficaciousness of the coping process (See Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Modification of the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping

This framework is modified from Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (1984). Here, the stressor is conceptualized as a symptom, such as fatigue. The individual then uses primary and secondary appraisal to select a coping skill, such as problem solving. The outcome is reduced fatigue.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: an intervention introducing a coping skill; evaluation of fatigue prior to and after the intervention involving participants with primary diagnosis of a hematological malignancy undergoing active treatment, receiving a stem cell transplant, or in survivorship to capture all points in the illness journey. Studies with mixed cancer populations were included if > 50% of participants had a primary diagnosis of hematologic malignancy. Participants needed to be 18 years or older, as coping styles and stressors may change with age.36 Articles published in the English language over the last 20 years were selected. This timeframe reflects advances in treatments and technology. For example, in 2001, the FDA approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), such as imatinib for chronic myelogenous leukemia,37 TKI’s are known to increase the risk of high grade fatigue for patients.38 Similarly, therapies such as thalidomide for multiple myeloma were introduced in 2003,39 which has significant side effects, including fatigue.40

Exclusion Criteria

Observational research, qualitative studies, and published studies at the protocol stage were excluded from this review.

Search Strategy

Two librarians experienced in health science literature searches assisted with developing, revising, and finalizing a search strategy, with common-cancer related symptoms including fatigue. For further details, please see Table 2. The literature search was performed in June 2021, in PubMed, Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, APA Psych INFO, and Scopus using Boolean phrases, MeSH terms, and added other pertinent key words identified through the search process. In total, 1,992 articles were found. The Cochrane Clinical Trials database, ProQuest dissertation database, the American Society of Clinical Oncology abstracts, and American Society of Hematology Abstracts were also searched, yielding an additional 246 articles.

Table 2:

Search Terms and Strategy

| Database | Coping + adaptation + resilience | Symptoms | Hematological malignancies |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Coping behavior” OR “Coping behaviors” OR “Coping behaviour*” OR “Coping mechanism*” OR “Coping strateg*” OR “Coping skill*” OR “Coping Style*” OR “Coping and adaptation” OR “Psychological Adaption” OR “Adaptive behavior*” OR “Adaptation, Psychological”[Mesh] “Resilience” or “Psychological resilience” OR “resilience, psychological” OR “post traumatic growth”) | (“symptom management” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom*” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “pain” OR “diarrhea” OR “mucositis” OR “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) | (“Hematological malignanc*” OR “hematological neoplasms”[Mesh] OR “haematological malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” [mesh]) |

| CINAHL | “Coping” OR “Coping

behavior* OR “Coping behaviour*” OR “coping

mechanism*” OR “Coping strateg*” OR “Coping skill*” OR “Coping style*” Or “Adapt*” OR “Adaptive behavior*” OR “Adaptation, Psychological” OR “Hardiness” OR “post traumatic growth ** CINAHL uses “hardiness” = resilience”* |

“Symptom*” OR “behavioral Symptom*” or “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “diarrhea” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” Or “Depress*” OR “pain” OR “mucositis” “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) | “Hematological malignanc*” OR “hematological neoplasms” OR “haematological malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” |

| SCOPUS | (“Coping behavior*” OR “Coping behaviour*” OR “Coping mechanism*” OR “Coping strateg*” OR “Coping skill*” OR “Coping Style*” OR “Coping and adaptation” OR “Psychological Adaption” OR “Adaptive behavior*” OR “Adaptation, Psychological” “Resilience” or “Psychological resilience” OR “resilience, psychological” OR “post traumatic growth”) | (“symptom management” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom*” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “pain” OR “diarrhea” OR “mucositis” OR “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) | “Hematological malignanc*” OR “hematological neoplasms” OR “haematological malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” |

| EMBASE | “coping behavior” OR

“coping” OR “cope” OR “coping

mechanism” OR “coping strategy” OR “coping

behaviour” OR “psychological adjustment” OR

“adaptation, psychological” Or “emotional

adaptation” OR “emotional adjustment” Or

“psychologic adaptation” OR “psychological

resilience” OR “resilience” OR “post

traumatic growth” Adaptation = “psychological adjustment” |

(“symptomology OR “symptom management” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom*” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “pain” OR “diarrhea” OR “mucositis” OR “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) |

“cell transplantation” OR “Hematological malignanc*” OR “hematological neoplasms” OR “haematological malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” |

| APA Psych INFO | (“Coping behavior” OR “Coping behaviors” OR “Coping behaviour*” OR “Coping mechanism*” OR “Coping strateg*” OR “Coping skill*” OR “Coping Style*” OR “post traumatic growth” or “psychosocial factors” OR “Psychological Adaption” OR “Adaptive behavior*” OR “Adaptation, Psychological” “Resilience” or “Psychological resilience” OR “resilience, psychological” OR “post traumatic growth”) | (“symptom management” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom*” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “pain” OR “diarrhea” OR “mucositis” OR “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) | “Hematologic* malignanc*” OR “hematologic* neoplasms” OR “haematologic* malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” |

| CENTRAL (Cochrane) | (“Coping behavior*” OR “Coping behaviour*” OR “Coping mechanism*” OR “Coping strateg*” OR “Coping skill*” OR “Coping Style*” OR “Coping and adaptation” OR “Psychological Adaption” OR “Adaptive behavior*” OR “Adaptation, Psychological” “Resilience” or “Psychological resilience” OR “resilience, psychological” OR “post traumatic growth”) | (“symptom management” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom*” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “pain” OR “diarrhea” OR “mucositis” OR “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) | “Hematologic malignanc*” OR “hematologic neoplasm*” OR “haematologic* malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” |

| ProQuest dissertation | ((“Coping behavior” OR “Coping behaviors” OR “Coping behaviour*” OR “Coping mechanism*” OR “Coping strateg*” OR “Coping skill*” OR “Coping Style*” OR “post traumatic growth” OR “Psychological Adaption” OR “Adaptive behavior*” OR “Adaptation, Psychological” OR “Resilience” OR “Psychological resilience” OR “resilience, psychological” OR “post traumatic growth” | AND (“symptom management” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom*” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “suffering” OR “wellbeing” OR “discomfort” OR “nausea” OR “constipation” OR “fatigue” OR “distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “pain” OR “diarrhea” OR “mucositis” OR “dry mouth” OR “dysphagia” OR “swelling” OR “swollen”) | AND (“Hematologic* malignanc*” OR “hematologic* neoplasms” OR “haematologic* malignanc*” OR “myeloma” OR “leukemia” OR “lymphoma” OR “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation”)) |

| American Society of Clinical Oncology Abstracts | ** modified search strategy due to

different search engine capabilities ** “cope” 87 of those → 2 relevant abstracts “adapt” / “resilience” - no additional articles found |

||

| American society of hematology | ** modified search strategy due to

different search engine capabilities **

“cope” AND “symptoms” → 52 total results of those, 2 relevant and were added |

||

Screening Process and Data Extraction

All article citations were uploaded to a citation manager (EndNote) and duplicate articles were removed (n=628). Citations were then exported to Rayyan for title and abstract screening. 41All titles and abstracts were independently screened using the outlined inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the title / abstract screening, a total of 91 articles remained. We manually searched and used EndNote to find full texts, and four articles could not be found, with a full text screening on 87 articles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Author L.A. independently evaluated the 87 articles and identified a total of 12 articles that met the criteria and were included in the final review, with n=9 articles from the formal literature search and n=3 from the gray literature. Reasons for exclusion included: no coping intervention, < 50% hematologic cancer, qualitative or observational study, pediatric participants, no fatigue evaluation, study protocol, or not patient focused. Please refer to the PRISMA Diagram, Figure 2, for further details.

Figure 2:

PRISMA Diagram

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers, and other sources

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021 ;372: n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

The following were extracted from the articles: Title, Author(s), Year, Sample, Methods, Design, Intervention, Symptom Outcomes, Additional Outcomes, Limitations, and Findings (Table 3). The primary measured outcome of each study is denoted with an asterisk in the Table of Evidence (Table 3). Studies are also organized by intervention type (Table 4). Authors L.A. and M.M. independently assessed article quality using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence Based Practice (JHNEBP) appraisal tool. The JHNEBP tool uses a two-part grading system based on the study’s evidence and quality.42 The numerical level refers to the study design, with level I for randomized controlled trial (RCT), a systematic review of RCTs, or mixed methods design with a level I quantitative study.42 Level II designates a quasi-experimental study, systematic review of RCTS and quasi-experimental designs or solely quasi-experimental designs, or mixed method design with a level II quantitative study.42 Level III refers to non-experimental studies, which were excluded from this systematic review. Then, quality ratings are given to each study. High quality studies with adequate control, generalizable results, definitive conclusions, sufficient samples sizes receive an “A”.42 Good quality studies with some control, reasonably consistent results, fairly definitive conclusions, and sufficient sample sizes for the study design receive a “B.”42 Studies with major flaws such as inconsistent results, minimal or inadequate control, small sample size, or inconclusive findings receive a “C.”42 Articles were individually assessed using the JHNEBP tool for bias, and discrepancies were verbally discussed between L.A. and M.M. until an agreement was reached.

Table 3:

Table of Evidence

| Title ; Author | Year | Sample | Methods | Design | Intervention | Fatigue outcomes | Additional outcomes | Limitations | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improving Quality of Life in Hematopoietic

Stem Cell Transplantation Survivors Through a Positive Psychology

Intervention ; H. L. Amonoo, C. Kurukulasuriya, K. Chilson, L. Onstad, J. C. Huffman and S. J. Lee |

2020 | N= 29 N=26 completed all pre and post measures Adults > 18 Hx of HSCT in Washington, USA 0.4–39 years post transplantation English-speaking 82.8% Female 89.6% White 79.3% college degree or higher Mean age = 62.3 years Mean time since transplant = 11 years |

Qualitative interviews and self-reported

assessments Assessments given at baseline and at end of intervention Participants recruited by mail, newsletter, and clinic. |

One-arm pilot study design | Group format phone-delivered positive

psychology (PP) intervention to increase resilience

8-session weekly PP intervention, completed weekly exercise on own, then 30 min group call |

Fatigue–PROMIS:

p> 0.05 |

Anxiety–HADS:

p>0.05 Depression–HADS: p> 0.05 Pain–PROMIS: p>0.05 Global Physical–PROMIS: p> 0.05 Happiness ( 0–10 scale): increase in happiness after intervention p<0.001 Optimism (0 −10 scale: increase in optimism after intervention p = 0.008 Resilience–CD-RISC: increase in resilience after intervention p=0.03 Gratitude–GQ-6: p>0.05 Feasibility*: 96% completion of PP sessions; Acceptability*: Participants found exercises easy (7.6/10) & helpful (8.1 / 10) |

Participants largely educated, non-Latino,

white and women, single academic sample Small sample size Varied post-HSCT window Unknown weekly treatment fidelity for self-administered exercises No control group |

No changes noted for all symptom outcomes and

other PROS, with exception of resilience and happiness

Notable that group consisted of participants ranging from 0.4 to 39 years post-transplant |

| A positive psychology intervention to promote

health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the PATH

proof-of-concept trial H. L. Amonoo, A. El-Jawahri, C. M. Celano, L. A. Brown, L. E. Harnedy, R. M. Longley, et al. |

2021 | N=25, final

n=12 Allogenic HSCT adults > 18 years in Massachusetts, USA 95% white 55% female Mean age = 52.6 years |

Convenience

sample Baseline assessment at 100 day post HSCT follow up, then post intervention assessments |

Single arm, proof of concept trial | Positive psychology intervention (PPI)

8 weeks, focusing on gratitude, strength, and meaning 1:1 sessions with HA by phone, then independently completed exercises |

Fatigue-

PROMIS d=0.19 |

Anxiety–HADS:

d=−.031 Depression–HADS: D= −0.29 Feasibility*: 7.98, p value 0.001 Acceptability*: 8.34, p value 0.001 QoL–(FACT-BMT): d=0.14, p> 0.05 Optimism–(LOT-R) d=0.32 Positive affect–(PANAS) D=0.32 Physical Function- PROMIS: d =0.083 |

Poor attrition: 2 deaths; 9 withdrawals d/t

physical symptoms, and 2 lost to follow up Not blinded to study, no control group Baseline QOL and physical function= moderate No reported p values for secondary outcomes |

Small to medium effect size for physical function, quality of life, fatigue, depression, anxiety, positive affect, and optimism, no significant changes |

| The effect of relaxing breathing exercises on

pain, fatigue and leukocyte count in adult patients undergoing

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation *abstract only* ; E. Bayrak and G. Can |

2020 | N = 67 bone marrow transplant patients

N=30 in intervention group (IG) N = 37 in control group (CG) Hospital in Turkey 35.8% Female 49.2% Primary or lower level education |

Pt randomized to IG or CG groups

Unknown when intervention began or when measures were taken |

Two arm randomized post-test control group design | Relaxing breathing intervention taught by

instructor for 20 minute periods / 5 days for one week

Individual exercises |

Fatigue - YIBO:

No statistically significant differences reported in pain between IG and CG |

Discharge time: discharge in IG

shorter than CG with p = 0.04 Pain–BPQ: No significant differences reported in pain between IG and CG |

Unclear how patients received intervention or

HSCT status Limited statistical analysis available Fatigue in CG higher at baseline Unknown when assessments measured |

Limited study showing decrease in discharge time but no effect on pain or fatigue after a relaxing breathing intervention |

| Title | Year | Sample | Methods | Design | Intervention | Symptom related outcomes | Additional outcomes | Limitations | Findings |

| Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in

a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in

patients with lymphoma; L. Cohen, C. Warneke, R. T. Fouladi, M. A. Rodriguez and A. Chaoul-Reich |

2004 | N = 39 N = 20 intervention group (IG) N = 19 wait list control group (CG) Adult patients with lymphoma Receiving CHOP or similar chemo currently or within past year in Texas, USA 66.7% Female Mean age: 51 years 36% Hodgkin’s Lymphoma 76.9% not actively receiving chemotherapy |

TY “Tibetan yoga” or wait list

control group assigned sequentially using minimization

Stratified to group by cancer type status of chemotherapy, age, gender, and baseline anxiety score Baseline measurements, again 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months after intervention |

Quasi experimental study with wait–list control group | Tibetan yoga–meditative technique

“mind body” controlled breathing, visualization,

mindfulness techniques, and postures 7-week program 1x a week class Pt provided with audio tapes and printed materials, encouraged to practice 1x a day |

Fatigue-BFI*:

P value = 0.93, |

Anxiety -State*:

P value > 0.90, Depression–CES-D*: P value =0.56, Intrusion and Avoidance - IES–D: P= 0.92 Sleep Disturbance -PSQI*: Significant improvement in IG between pre and post intervention scores for CG and IG with p = 0.004 |

CES-D and STATE may be less responsive to

subtle changes Floor effect, scores very low at baseline / follow up indicating this group of participants had low levels of anxiety and depression Small sample size, underpowered |

No statistical significance between anxiety, depression, or fatigue, only overall sleep quality |

| When is the best time for psychotherapeutic

intervention following autologous peripheral blood stem cell

transplantation? E. Frick, M. Tyroller, N. Fischer, R. Busch, B. Emmerich and I. Bumeder |

2006 | N = 196 With dropouts, N=60 N = 36 early intervention (EI) N = 24 late intervention (LI) Adult patients undergoing HSCT in Germany 45% Female 21.7% College degree or higher Mean age = 52.8 years |

Pre transplant + transplantation assessments

administered in clinic 6 weeks, three months, six months and 12 months post HSCT assessments |

Prospective longitudinal study with psychotherapeutic intervention with randomization, two armed study | Early intervention (EI) 1–6 months

following HSCT vs. Late intervention (LI) months 6–12 following HSCT Individualized psychodynamic short term psychotherapy–15 sessions (psychiatrist and Jungian analyst) grounded in Desoille’s method for guided imagery, coping and mastery, |

Fatigue- EORTC-QLQ-30*: EI group reported significantly less fatigue compared to the LI group with P = 0.01, d=0.74 |

Global Health-EORTC -QLQ

C30*: EI group reported significantly improved global health compared to LI group P=0.001, d=0.97 Energy Level–POMS: No significant differences in energy found between EI and LI groups with p= 0.319, d= 0.27 Emotional Functioning- EORTC-QLQ C30*: EI group reported significantly improved emotional functioning compared to LI group p=0.047, d=0.56 Social Functioning-EORTC- QLQ C30*: P=0.090 d=0.48 Role Function: EORTC - QLQ C30*: EI group reported significantly improved role function = compared to LI group p = 0.004, d=0.84 |

No control group Poor attrition 60% initially enrolled did not complete due to illness, distance from hospital, no perceived need for therapy, or concerns over psychotherapy All patients received in depth hospital psychotherapy regardless of group Ceiling effect Measures tend to improve w time after HSCT |

After controlling for performance status + remission, global health score, emotional functioning, fatigue, and role function differences between early and late intervention groups remain significant |

| Online-streamed yoga as a non-pharmacologic

symptom management approach in myeloproliferative neoplasms ; J. Huberty, R. Eckert, K. L. Gowin, B. Ginos, H. E. Kosiorek, A. C. Dueck, et al. |

2016 | N = 38 national sample Adult patients with diagnosis of Polycythemia Vera (PV n = 16), Essential thrombocythemia (ET n = 16), and myelofibrosis (MF n=6) nationally distributed sample in USA 89.5% Female 97.3% Caucasian 65.8% Bachelor’s degree or higher Median age = 56 years |

Recruitment via social media, convenience

sample Surveys administered at baseline week 0, midpoint (week 7), post intervention week 12, and follow up week 16 |

Single arm pre-test post-test quasi

experimental intervention Nonrandomized |

60 minute online streamed yoga weekly for 12

weeks Individual, at home Asynchronous Adherence to intervention averaged 50.8 +/− 36.2 min / week One adverse event * irritated large spleen * |

Fatigue–MPN SAF:

Significant improvement in fatigue from pre to post intervention with p = 0.004, d = 0.33 |

Pain–PROMIS:

p>0.05 Anxiety–PROMIS: Significant improvement in anxiety from pre to post intervention with p = 0.002 d = −.67 Depression–PROMIS: Significant improvement in depression from pre to post intervention with p = 0.049 and effect size d= 0.41 Sleep–PROMIS: Significant improvement in sleep from pre to post intervention with p <0.001. d = 0.58 Symptom Burden–MPN SAF: Significant improvement in symptom burden from pre to post intervention with p = 0.004, d = 0.36 Feasibility*: 69% of those who enrolled completed the 12 week intervention Acceptability*: 75% felt it was helpful for coping with MPN related symptoms Sexual Function–PROMIS: p>0.05 Practicality*: 75% felt safe while practicing yoga 1 adverse event (irritated spleen) |

Small sample size Mostly white, well educated, female sample No control group High risk for bias |

Online yoga may be effective for improving MPN

symptom burden with improvements in overall SB, fatigue, anxiety,

depression, and sleep Easy to implement study, home based, online streamed yoga (need mat and streaming capability) |

| Online yoga in myeloproliferative neoplasm

patients: results of a randomized pilot trial to inform future research Huberty, J. Eckert, R., Duek, A., Kosiorek, H., Larkey, L., Gowin, K., Mesa, R. |

2019 | N=48 N= 27 yoga intervention group (IG) N=21 wait list control group (WLCG) Adult patients with MPN disorder 93% Female 93% white 83% college degree or higher Mean age = 56.9 years Diagnosis: Polycythemia Vera = 31% Essential Thrombocythemia = 39% Myelofibrosis 29.2% |

Online recruitment Randomized to yoga or waist list control group Measures at baseline, midpoint, post intervention, and follow up Self-report measures and online web analytic program |

Pilot randomized trial with a wait list control group | 12 weeklong yoga intervention, 60 minutes /

week Yoga incorporated mindfulness; hatha and vinyasa style classes–avoided poses that would irritate enlarged spleens / livers Self-report yoga minutes, patient reported outcomes, and laboratory values noted at change from baseline to each time point |

Fatigue–MPN SAF:

d= 0.02 to −0.56 |

Yoga participation

Per analytic program, averaged 40.8 min / week Total symptom score–MPN SAF d=0.44 to −0.31 Anxiety–NIH PROMIS: d= −0.27 to −0.37 Depression–NIH PROMIS: d= −0.53 to −0.78 Sleep Disturbance–NIH PROMIS: d=−0.26 to −0.61 Pain Intensity–NIH PROMIS: d=−.034 to −0.51 Quality of life–NIH PROMIS d=0.10 to d=0.09 Blood draw feasibility: 92.6% completed initial draw 70.4% completed final draw |

Homogenous sample Did not account for confounding factors Self-reported data Strict exclusion criteria, excluded participants with depression or current yoga practices |

Findings: Yoga and mindfulness intervention

produced small effect sizes for sleep disturbances, pain intensity,

anxiety, and a moderate effect on depression. Minimal differences observed for other measures, including fatigue. |

| Title ; Author | Year | Sample | Methods | Design | Intervention | Symptom related outcomes | Additional outcomes | Limitations | Findings |

| Internet-assisted Cognitive Behavioral

Intervention for Targeted Therapy-related Fatigue; (TTF) Jim, H. Knoop, H. Nelson, A. M. Hyland, K. Hoogland, A. I. Jacobsen, P. B. |

2017 | N = 44 patients N = 29 Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention group (IG) N = 15 wait list control group (CG) Adult patients diagnosed with CML on oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with fatigue (moderate to severe) in Florida, USA 48% female 86% white 55% college degree or higher Mean age = 53years Average of 5.2 years since dx |

Pt approached by phone / in person

Randomized to receive CBT TTF or WLC on 2:1 basis and stratified by sex Measures at baseline and follow up after 18 weeks of therapy |

Pilot randomized trial with a control wait group | CBT TTF certified therapist at in person

session 90 minutes Subsequent via facetime for 45 min at 1–2 week intervals for 18 weeks Fidelity checks between therapists, postdoc fellow, and Dr. Hans Knoop CBT focused on Problem recognition, solution generation, implementation, progress evaluation |

Fatigue–FACIT-F*:

The IG had greater improvement in fatigue severity compared to the CG with p<0.001, d= 1.07 Large effect size improvement in fatigue even w those undergoing active treatment |

Feasibility*: 89% retention rate 79% completion rate QOL - FACT -G: Improvements in IG compared to CG p=0.05, d=1.12 Functional Well -being QOL–FACT-G: improvements in IG compared to CG, p=0.03, d=1.06 Emotional well-being - QOL–FACT-G: improvements in IG compared to CG, p<0.001, d=1.12 Physical Well-being–FACT-G: p = 0.151 Social Well-Being: FACT-G: p= 0.80 |

Small and homogenous

sample Wait list control group instead of time / attention control group |

Tailored to very specific

symptom–fatigue, and was significant in improving fatigue

symptoms 89% in IG had improvement compared to 29% in CG |

| A virtual resiliency program for lymphoma

survivors: helping survivors cope with post-treatment challenges;

Perez, G. K. Walsh, E. A. Quain, K. Abramson, J. S. Park, E. R. |

2020 | N = 30 Adult patients with history of lymphoma within 2 years of completing treatment in Massachusetts, USA 50% female 96% White 73.3% College degree or higher |

Data captured at baseline, post program

completion, and one month post program completion

Treatment completers if > 75% of sessions N=20 completed sessions |

Exploratory mixed methods study with qualitative arm and single arm pilot design | 8-week resiliency group program based on the

Stress management and Resilience Training–Relaxation Response

resilience Program Mindy body program, cognitive behavioral, and positive psychology Delivered via remote sessions telehealth sessions Groups of 4–6 1.5 hours a week, weekly for 8 weeks |

Fatigue–FSI:

fatigue decreased, but p > 0.05 |

Anxiety–GAD-7:

anxiety decreased but p = 0.07 Depression–CESD-10: depression decreased but p > 0.05 Feasibility*: 23% eligible patients enrolled and of those, 81% completed treatment Acceptability*: 81% enjoyed program and 76% satisfied Coping- MOCS -A: Overall improvement p = 0.005, d=0.67 Ability to relax at will p=0.01 Being assertive about needs p=0.09 Recognize and manage situations P=0.05 Stress (0 to 10 Likert scale) No significant differences in stress between pre and post intervention measurements (stress increased after intervention) |

No control groups Single academic center Majority white and highly educated small sample size Patients reported technical challenges and scheduling challenges with the telehealth program |

Targeted mind body resilience program for

lymphoma survivors did not improve fatigue or stress but did

significantly impact ability of participants to cope

Clinical levels of anxiety and depression were decreased after intervention |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for

Treatment-Related Fatigue in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients on

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: A Mixed-Method Study; Poort, H. Onghena, P. Abrahams, H. J. G. Jim, H. S. L. Jacobsen, P. B. Blijlevens, N. M. A. Knoop, H. |

2019 | N=5 N = 4 Adult patients with CML and on tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) for 3 months Netherlands Reporting severe fatigue 100% Caucasian 25% Female Mean Age = 49 years Time since diagnosis = 3.5 years |

Single case randomization Each participant randomized to length of phase “A” No treatment baseline for 7–26 weeks for phase A–weekly CIS fatigue measurements Then entered phase “B” with CBT Phase B lasted 26 weeks w/ biweekly sessions and weekly fatigue measurements |

Mixed methods convergent design

Quantitative data through randomized single case experiment (SCE) |

Biweekly CBT sessions for 26 weeks One hour sessions Weekly or biweekly that tapers off as participants start to integrate more into life Treatment goals Reduce severe fatigue and disability Coping strategies, recognizing dysfunctional cognitions, and encouragement of sleep wake cycle, |

Fatigue–CIS*:

No significant changes between phase A and phase B, overall mean difference in fatigue for phase AB was −3.69 with p = 0.18 |

Feasibility*:

4/5 participants completed intervention Acceptability*: Participants rated satisfaction with intervention as 8/10 |

Fatigue as a complex and variable phenomenon

N=(50%) hospitalized in phase B Limited number of participants Homogenous sample size Younger patient population than average CML patient SCE design does not account for with unrelated medical / psychosocial events |

Intervention showed nonsignificant decreases in fatigue and participants qualitatively endorsed better ability to “accept” and cope with fatigue and manage fatigue related disability |

| Relaxation and guided imagery or music therapy

for the reduction of pain during cancer treatment: A controlled clinical

trial; Scholich, S. Hasenbring, M. I. *abstract only* |

2009 | N=63 patients Adult patients undergoing HSCT in Germany 35% Female |

Random assignment to 3 groups:

Relaxation and guided imagery (RI), Music therapy (MT), or Psychological support (PS) Nausea, pain, fatigue assessed using diary from pre-treatment until discharge |

“Controlled clinical trial” | Semiweekly sessions during course of

hospitalization Relaxation combined with Guided imagery (RI) Music therapy (MT) and psychological support (PS) |

Fatigue*:

No significant differences reported |

Outcomes measured “via

diary” Pain intensity*: Patients in RI group had significantly less pain intensity than those in the MT or PS groups Nausea*: No significant differences reported |

Limited information Unknown what specific measures used for pain, fatigue, nausea Unknown treatment fidelity Lacking additional characteristics of patients Unclear what is meant by psychological support |

Pain improved with relaxation and guided imagery intervention, nausea and fatigue not affected |

| An mHealth Pain Coping Skills Training

Intervention for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients:

Development and Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial; Somers, T. J. Kelleher, S. A. Dorfman, C. S. Shelby, R. A. Fisher, H. M. Rowe Nichols, K. Sullivan, K. M. Chao, N. J. Samsa, G. P. Abernethy, A. P. Keefe, F. J. |

2018 | N=36 N= 18 intervention group (IG) N= 18 control group (CG) Adult HSCT patients with pain score of > 3 in the USA 50% female 83% white 56% college or higher degree Mean age= 56 years 83 % autologous HSCT Average time since ca dx = 22 months |

Developed protocol first via focus groups,

user testing, then controlled trial Both IG and CG underwent HSCT prior to filling out baseline assessments Baseline and then post intervention assessments Pt randomized to control / treatment as usual group or intervention group IG given iPad |

Pilot randomized controlled trial | 6, 50 minute sessions delivered over

6–10 weeks One outpatient session and then 5 sessions at home via iPad Videoconferencing Didactic and experiential components Homework on incorporating into daily life Adherence = review homework Positive reinforcement Taught relaxation, cognitive restructuring, activity pacing, planning, imagery, problem solving, and goal setting |

Fatigue–SF-36: IG had significant improvement in fatigue with p = 0.003, ES = 0.94 CG had significant improvement in fatigue with p = 0.004, ES 0.81 |

Pain Severity–BPI:

IG did not have significant improvement CG had nonsignificant improvement in pain severity with p = 0.07 Pain disability–PDI: IG and CG had significant improvements post intervention with p = 0.006, effect size d = 0.79 for IG and p = 0.02, effect size d = 0.69 for CG Feasibility* = 92% enrolled completed study Acceptability*: 100% rated intervention as good to excellent 2 minute walk test–2MWT: d=0.66 vs. 0.41 IG had significant improvement over time p=0.03 Physical Disability - Self-report: IG and CG had significant improvement in physical disability, p=0.005 and p <0.001 respectively |

Relatively low pain level > 3 so may

not be able to demonstrate significant change May not recruit or retain persons with higher levels of pain Required internet Small RCT Short follow up period during HSCT pain may be improving due to increased time from transplant day Single medical center Fairly homogenous sample size and group |

Mobile pain coping skills treatment (PCST) likely to help patients manage their pain compared to control group and significantly improved 2 minute walk test, pain disability and decreased fatigue |

Table 4:

Intervention chart

| Author | Year | Intervention | Intervention type | Interventionist | Delivery format | Individual or group sessions | Session length | Intervention length | Theoretical / conceptual framework | Symptom outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amonoo, et. al | 2020 | Positive psychology

intervention: gratitude, strength, & meaning based, with future planning |

Emotion-focused | Clinical research coordinators, (received training for PPI) | Phone + Self-complete component |

Group | 30 minutes | 8 weeks | Positive psychology conceptual framework | No statistically significant differences in fatigue |

| Amonoo, et. al | 2021 | Positive psychology intervention (same as above) | Emotion-focused | Psychiatrist, MD | Phone with self-complete component | Individual | 15–20 minutes | 8 weeks | Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions | Small–medium effect sizes, no significant differences in fatigue |

| Bayrak & Can | 2020 | Relaxing breathing intervention | Emotion-focused | n/a | In person sessions | Individual | 20 minutes | 5 days / one week | n/a | Fatigue improved |

| Cohen, et. al. | 2004 | Tibetan yoga + meditative mind body techniques | Emotion-focused | Tibetan Yoga Instructor | In person yoga classes once a week

Self-complete component audio tapes + printed materials |

Group yoga class individual self-complete component |

n/a | 7 week program | Tsa Lung and Trul Khor | No statistical significance on a fatigue |

| Frick, et. al. | 2006 | Individualized psychodynamic short term psychotherapy–guided imagery, coping, and mastery | Problem and emotion focused | Psychiatrist and Jungian Analyst | In person | Individual | 1 session every other week | 15 sessions in 6 months (1–6 months vs. 6–12 months post BMT) |

Desoille’s method for guided imagery, coping, and mastery | Early intervention has greater effect on fatigue |

| Huberty, et. al | 2016 | Yoga and breathing / mindfulness | Other | N/a | Online streamed yoga sessions | Individual (at home) | 60 minute weekly sessions | 12 weeks | n/a | Improved fatigue significantly |

| Huberty et al | 2019 | Yoga and breathing / mindfulness | Emotion focused | Videos by trained yoga instructors Yoga videos selected by physician specializing in MPNs, PhD trained researcher/certified yoga instructor, MS trained bio- mechanist/yoga educator | Online streamed yoga sessions | At home / individual | 60 minute weekly sessions | 12 weeks | Hatha and Vinyasa yoga; mindfulness | Small–medium effect in fatigue |

| Jim, et. al. | 2017 | CBT for Targeted Therapy Fatigue (TTF)

Certified therapist Problem recognition, solution generation, implementation |

Problem-focused | Doctoral students in clinical psychology | One on one sessions and Facetime sessions | Individual | 90 minutes initial Then 45 min on facetime |

1–2x a week for 18 weeks | Cognitive behavioral model of therapy r/t fatigue | Clinical and significant improvement in fatigue |

| Perez, et al | 2020 | Stress management and resilience training

relaxation response–(SMART 3RP) - lymphoma Mind / body, cognitive behavioral, and positive psychology |

Problem and emotion focused | n/a | Telehealth sessions (Vidyo platform) | Group (4–6) | 90 minutes | 8 weeks | Stress management and resilience training–relaxation response program; | Non-significant improvement in fatigue |

| Poort, et. al | 2019 | Cognitive behavioral therapy | Problem-focused | Clinical psychologists | n/a | Individual | 60 min | Weekly / biweekly for 26 weeks | Gilissen’s Cognitive behavioral model of cancer r/t fatigue | Improvement in fatigue, but non-significant |

| Scholich & Hasenbring | 2009 | Relaxation and guided imagery

(RI) Music Therapy (MT) Or psychological support (PS) |

Emotion-focused | n/a | In person sessions | Individual | n/a | Semiweekly during hospitalization for BMT | n/a | Fatigue did not change |

| Somers, et. al. | 2018 | Coping skills, relaxation, restructuring, activity pacing, planning, imagery, etc. | Problem and emotion focused | Therapist | One in person, rest videoconferencing via Skype with didactic and experiential components | Individual sessions | 50 minutes | 6 delivered over 6–10 weeks | n/a | Significantly improved fatigue |

Results

A total of twelve studies were included in the final review. Study sample sizes ranged from 429 to 196,43 with a total of 620 participants across all studies. Eight studies were based in the United States. Four of the twelve studies were international, with two taking place in Germany,43,44 one in Turkey, 45 and one in the Netherlands.29 Mean ages of participants ranged from 49 years29 to 62.3 years.46 Most of the United States studies included majority Caucasian participants and international studies provided limited information regarding participant’s race or ethnicity.

Six studies focused on participants undergoing stem cell transplantation or with a history of stem cell transplantation. Two studies included lymphoma patients, two included persons with chronic myeloid leukemia, and two included persons with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN). Recruitment for studies occurred via clinic recruitment, approaching inpatients, or via internet surveys. The retention across studies ranged from 42% 43 to 91.6%.30 Common reasons for attrition included lack of time, no use for psychotherapy, physical decline, or death.

Article Quality

Three of the studies were of IB quality, indicating a randomized controlled trial (level I) with good quality (B).30,47,48 Two studies were of IC quality denoting a randomized controlled trial (level I) with low quality (C).39,45 One study was of IIB quality, indicating a quasi-experimental study (level II) with good quality (B).49 The remaining six studies were of IIC quality, signifying a quasi-experimental study (level II) with low quality (C) 29,43,46,50,51,52 (Table 5).

Table 5:

JHNEBP chart

| Study citation | Evidence | Quality | Final grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Amonoo et al., 2020) | Level II Quasi experimental study one-arm pilot study |

C Small sample size, varied post-HSCT window, unknown fidelity, no control group |

IIC |

| (Amonoo et al., 2021) | Level II Quasi experimental study one arm study |

C Low attrition, no blinding, no control, small sample size, participants had moderate baseline QoL |

IIC |

| (Bayrak & Can, 2020) | Level I Randomized controlled trial |

C Unknown fidelity of intervention when assessments taken, how patients received intervention, etc. |

IC |

| (Cohen et al., 2004) | Level II Quasi experimental with control group |

B Underpowered study, small sample size, potential for ceiling effect |

IIB |

| (Frick et al., 2006) | Level II Quasi experimental two arm study |

C No control group, poor attrition, ceiling effect |

IIC |

| (Huberty, et al., 2016) | Level II Quasi experimental one arm study |

C No control group, homogenous sample, high risk for bias |

IIC |

| (Huberty, et al., 2019) | Level I Randomized controlled trial |

B Smaller and homogenous sample size, wait list control group |

IB |

| (Jim, et al., 2017) | Level I Randomized controlled trial |

B Small sample size, wait list control group |

IB |

| (Perez et al., 2020) | Level II Quasi experimental one arm mixed methods |

C No control group, homogenous sample |

IIC |

| (Poort et al., 2019) | Level II Randomized single case experiment |

C No control group, small sample size, high risk for bias |

IIC |

| (Scholich & Hasenbring, 2009) | Level I Randomized controlled trial |

C Unknown treatment fidelity, no control group, unclear measures, unclear randomization method |

IC |

| (Somers et al., 2018) | Level I Randomized controlled trial |

B Small and fairly homogenous sample size, brief follow up period, single center study |

IB |

Synthesis

Of the twelve studies included in the review, four found significant reductions of fatigue, three demonstrated a nonsignificant reduction in fatigue, and five studies showed no reduction of fatigue. Notably, studies of IB quality all indicated significant or small to medium effect sizes in fatigue reduction.30,47,43 Additional studies that reduced fatigue were of IIC quality.29,43,51,47 Studies that did not reduce fatigue were IC quality, 39,45 IIB quality,49 or IIC quality.46,45 Seven of the twelve studies reduced fatigue, with effect sizes (ES) ranging from small to large. ES for significant reductions of fatigue ranged from small d=0.1945 to large d=0.9430 and d=1.07 43 (Table 6). Interventions that significantly reduced fatigue were guided imagery, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), yoga and breathing exercises, and a multi-faceted coping intervention that included relaxation, guided imagery, and activity pacing. Interventions that non-significantly reduced fatigue included CBT - targeted therapy fatigue, yoga and mindfulness, and a resiliency program. Overall, the coping interventions had a mixed but beneficial effect in reducing fatigue.

Table 6:

Effect Sizes

| Author | Year | Intervention | Effect size on fatigue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amonoo et al | 2021 | Positive psychology

intervention Emotion focused coping |

D=0.19 Compared to baseline fatigue measurements |

| Frick et al | 2006 | Psychodynamic therapy Emotion and problem focused coping |

D= 0.74*

Early intervention group compared to late intervention group |

| Huberty et al. | 2016 | Online streamed yoga Emotion focused coping |

D=0.33*

Compared to baseline fatigue measurements |

| Huberty et al | 2019 | Online streamed yoga Emotion focused coping |

D= −0.02 to −.056

Intervention group compared to control group |

| Jim et al | 2017 | Cognitive behavioral therapy Problem focused coping |

D=1.07 *

Intervention group compared to control group |

| Somers et al | 2018 | Multiple strategies: Problem-solving, guided

imagery, goal setting Problem and emotion focused coping |

D = 0.94*

Intervention group compared to baseline |

denotes significant p value if reported by study at p < 0.05 or less.

Intervention Type

According to Lazarus and Folkman’s original coping distinction, interventions were separated into emotion-focused, problem-focused, and both problem and emotion-focused coping. We categorized interventions based on the article’s description of the interventions (Table 4). Seven of the interventions used emotion-focused coping, including meditation, 49 guided imagery, 39 relaxation and breathing, 45 yoga and mindfulness,42, 51 and positive psychology.41, 45 These studies were of IB quality 47 IC quality,39,45 IIB quality,49 and IIC quality.. 46,45,46 Of these seven emotion-focused interventions, the Huberty et al., 2016 study significantly reduced fatigue with p<0.05,46 and the Huberty et al., 2019 and Amonoo et al., 2021 interventions had small to moderate ES in reducing fatigue.47,45

Two of the interventions were problem-focused, both CBT – targeted therapy fatigue interventions.29, 43 The Jim et al. intervention was effective at significantly reducing fatigue, with a large ES of d=1.07, and was of IB quality.43 However, the Poort et al., intervention showed a nonsignificant reduction in fatigue with p=0.18, and was of IIC quality.29 Of three interventions that included both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, two had significant reductions30,43 and one showed nonsignificant reductions in fatigue. 47 The interventions ranged from a guided imagery and problem-solving intervention of IIC quality43 to a resiliency program with mind/body and CBT components of IIC quality47 to a mobile health program for pain coping that taught relaxation, cognitive restructuring, problem-solving, and goal-setting of IB quality. 30 Of the three different types of interventions, those that combined problem-focused and emotion-focused coping were most effective, while emotion-focused coping interventions were less likely to reduce fatigue.

Intervention Delivery

Interventions were also delivered in many different ways. Eight interventions were given to individuals via one-on-one sessions in person or video telehealth sessions, with four showing significant reduction,30,43,43,46 and two showing nonsignificant reduction in fatigue.29,47 Three interventions were delivered to groups with an unclear effect, with two studies showing no significant reduction,46,49 and one having nonsignificant reduction. 47 Two phone interventions had small ES45 or no reduction in fatigue.46 Of the five in-person interventions, one had a significant reduction in fatigue,43 one showed nonsignificant reduction,29 and three had no reduction in fatigue.39, 45, 49 All in-person interventions were individually delivered, except for the Cohen et al. intervention, which was an in-person, group yoga class.49 Three interventions utilized telehealth: with Skype30 and FaceTime interventions significantly reducing fatigue43 and a telehealth portal, Vidyo, non-significantly reducing fatigue.47 Interestingly, the Jim et al., and Somers et al., studies had an initial in-person appointment before transitioning to telehealth for the remaining sessions. Individual sessions were more effective than group sessions, and video-based telehealth interventions were more effective than telephone interventions.

Intervention Duration

Interventions were delivered over various lengths of time, with most taking place over 8 weeks or longer. One intervention occurred over one week, which did not have any significant reduction in fatigue.45 Another took place semi-weekly over 2 weeks, with no significant reduction in fatigue.39 Three interventions took place weekly over 7 – 8 weeks, with no significant reduction in fatigue46,49 or a small ES.45 Most studies occurred over 8 weeks or longer, with the longest interventions occurring for 24 to 26 weeks.29,43 Four of the seven interventions occurring over 8 weeks or longer showed significant reductions in fatigue.30,43,43,46 The remaining three studies had nonsignificant reductions in fatigue,29,47 or showed small to medium ES in reducing fatigue.47 There is a clear trend that longer interventions (e.g., over 8 weeks) are more effective at reducing fatigue in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Treatment Types

The patients included in this review had different types of hematologic malignancies and were at varying stages of their illness and treatment journey, presenting a challenge for synthesis. However, six of the twelve studies included hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients. Studies that included mostly allogenic or all allogenic patients had no significant reduction in fatigue46 or small ES.45 Of a mixed HSCT population with both allogenic and autologous patients, two interventions did not have an effect on fatigue. 39,45 Notably, studies that included mostly or all autologous HSCT patients did show significant reduction in fatigue.30, 43 Interventions in the allogenic HSCT population were not as effective as those in the autologous HSCT population.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review, that we are aware of, to examine coping skills interventions and fatigue within the adult hematologic malignancy population. The goal of this review was to determine if coping interventions are effective at reducing fatigue of adult patients with hematologic cancer and identify which coping interventions may be most effective at reducing fatigue.

Based on this review, we found coping skills interventions have a varied effect in reducing fatigue among adults with hematologic malignancies. This is despite the fact that fatigue is a major symptom of concern. Indeed, over 50% of patients treated with TKIs, 42% of HSCT survivors, and 18% long-term survivors of hematologic malignancy report profound and significant fatigue 53. The heterogeneity of studies limited our ability to draw conclusions about different disease types. However, there was a difference in the effectiveness of interventions in allogenic HSCT compared to autologous HSCT patients. This may reflect the increased symptom burden present for allogenic HSCT patients compared to autologous patients that persists for months after transplant.54

Fatigue was reduced in seven of the twelve interventions with small to large ES, however only four studies reached significance at p <0.05. Yoga, CBT, guided imagery, relaxation with active coping, and the SMART 3RP resiliency interventions reduced fatigue. Individual interventions were more effective in reducing fatigue compared to group interventions, and video-based remote interventions were more effective in reducing fatigue than telephone based interventions. Other commonalities in studies that reduced fatigue included longer duration of interventions, with interventions longer than 8 weeks more likely to reduce fatigue than shorter term interventions. Our ability to generalize findings is limited due to heterogeneity across the eleven studies included in this review, nevertheless, some of our findings are consistent with those from other studies. For instance, yoga with mindfulness is an effective intervention for fatigue in solid tumor cancer patients as well, with a multi-center RCT finding that yoga was effective in reducing fatigue and sleep disturbances in a diverse cancer patient population.55 A combined exercise and breathing regimen reduced fatigue in HSCT patients,56 highlighting potentially similar benefits obtained from exercise and yoga. Exercise is the only intervention currently “recommended for practice” to reduce fatigue by the Oncology Nursing Society.57 However, not every patient can exercise to reduce fatigue, especially if towards the end of life or with limited mobility.

Patients with hematological malignancies receive less referrals to palliative care,58 experience more aggressive end of life (EOL) care,58 and have higher odds of dying within 24 hours of hospice enrollment than solid tumor patients.59 Research around these disparities has found that hematologic-oncologists are more likely to view palliative care as EOL care compared to solid tumor oncologists, along with other misconceptions.60 Early introduction of palliative care in the illness journey has the potential to enhance symptom management and psychosocial, economic, and spiritual care for patients with hematologic malignancies, even when the patient has curative intentions.61 Findings from this review may be informative for clinicians across palliative care settings caring for adults with hematologic malignancies experiencing fatigue to evaluate the appropriateness and effectiveness of coping interventions and the value of palliative care for these patients and their families.

Coping interventions are a non-pharmacologic and accessible way to combat fatigue. A systematic review investigating the efficacy of medications for cancer-related fatigue demonstrated weak but inconclusive effects for carnitine and donepezil, and only a superior effect for methylphenidate.17 However, pharmacologic interventions are not without risk, with concerns for side effects, polypharmacy, or other contraindications. Notably, patients were able to harness additional benefits from coping interventions, including improved quality of life,43,43 reduced length of hospital stay,45 and increased resilience.46 Furthermore, coping interventions are typically low risk, with minimal harm to patients and families beyond time and potential financial costs. Future areas of research include measuring coping skills using a validated measure prior to and after the intervention. This will further elucidate the relationship between self-care, coping, and fatigue. A large randomized controlled trial could compare the effect of problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and combined problem and emotion-focused coping on fatigue. A rigorous randomized controlled trial would also enhance the quality of the evidence on coping skills, given no IA quality studies were included in this review. Finally, examining the effectiveness of coping interventions on patients receiving new therapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is warranted.

This review has a number of limitations. The studies included in the review used different coping interventions and various measurement approaches, making it difficult to compare and synthesize outcomes. This may be due to a lack of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in a majority of the studies. Though coping interventions were effective in improving active or positive coping skills when evaluated, a majority of studies did not evaluate coping skills prior to or after the intervention. This presented a challenge in evaluating whether the individual’s coping skills or if other factors, such as presence of another person or participant bias, contributed to outcomes. Studies were generally synthesized as having positive or negative findings, with a limitation to this approach as lacking nuance. Furthermore, p values are somewhat arbitrary, and ES may be a better estimate of intervention effectiveness. However, many studies did not report ES, and due to varying measurement tools, using p value of 0.05 as a significance threshold was most straightforward. Notably, some studies were of low quality. However, there is still value in understanding the overall landscape of coping skills interventions in this patient, and the potential benefits of reducing fatigue, a prevalent and difficult to treat symptom.

While some of the international studies did not report race or education of participants, those that did, especially in the United States, typically had higher participation of white, female, and college educated persons. The homogeneity of the participants reflects an ongoing issue with diversity in research in the United States.62 Additionally, the discrepancy reflects improving but still prevalent disparities, in HSCT among persons with lower socioeconomic status, higher comorbidities, Medicare insurance, and of Black, Hispanic, or nonwhite races.63 Research is needed to identify coping mechanisms with diverse cancer populations, especially as they may be diagnosed at later stages with a higher symptom burden. Many of the studies also had risk of bias present, with no control group, lack of fidelity measures to assess participation in the intervention, and issues retaining participants due to loss of follow up, withdrawal due to symptom burden, or death.

This review introduces a unique focus on fatigue within coping literature. This review’s strengths include the design of an in-depth systematic review with an extensive search. Another strength is the breadth of the coping definition, which allowed for a variety of studies to be included. A majority of the studies included in the review had small sample sizes, which increases the strength of the significant findings despite small sample sizes.

Conclusions

This systematic review found moderate strength of evidence for coping skills interventions in reducing fatigue in adult patients with hematologic malignancies throughout the illness trajectory. A combination of both problem and emotion-focused coping skills were found to be most effective compared to interventions that were solely emotion-focused. Clinicians that care for adults with hematologic malignancies should discuss benefits of coping interventions and integrate use of coping interventions with patients as a way to manage fatigue.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge Penn librarians, Richard James and Maylene Qiu for their guidance.

Funding Statement:

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Lucy Andersen and Molly McHugh are both predoctoral students funded by the University of Pennsylvania. Molly McHugh is supported by a NINR Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA training grant [T32NR009365]. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32NR009356. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosure:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Olsen M, Zitella L. Hematologic Malignancies in Adults. Oncology Nursing Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerlach C, Alt-Epping B, Oechsle K. Specific challenges in end-of-life care for patients with hematological malignancies. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. Dec 2019;13(4):369–379. doi: 10.1097/spc.0000000000000470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LLS LLS. Facts and Statistics Overview.

- 4.Bugos KG. Issues in Adult Blood Cancer Survivorship Care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2015/02/01/ 2015;31(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manitta V, Zordan R, Cole-Sinclair M, Nandurkar H, Philip J. The Symptom Burden of Patients with Hematological Malignancy: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011/09/01/ 2011;42(3):432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XS. Clinical Factors Associated With Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients Being Treated for Leukemia and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(5):1319–1328. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.5.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goklemez S, Saligan LN, Pirsl F, et al. Clinical characterization and cytokine profile of fatigue in hematologic malignancy patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2021/08/25 2021;doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01419-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochman MJ, Yu Y, Wolf SP, Samsa GP, Kamal AH, LeBlanc TW. Comparing the Palliative Care Needs of Patients With Hematologic and Solid Malignancies. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2018/01/01/ 2018;55(1):82–88.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Immanuel A, Hunt J, McCarthy H, van Teijlingen E, Sheppard ZA. Quality of life in survivors of adult haematological malignancy. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2019;28(4):e13067. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsenthaler C, Gao W, Siegert RJ, et al. Symptoms and anxiety predict declining health-related quality of life in multiple myeloma: A prospective, multi-centre longitudinal study. Palliative Medicine. 2019;33(5):541–551. doi: 10.1177/0269216319833588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White LL, Kupzyk KA, Berger AM, Cohen MZ, Bierman PJ. Self-efficacy for symptom management in the acute phase of hematopoietic stem cell transplant: A pilot study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2019/10/01/ 2019;42:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nes LS, Ehlers SL, Patten CA, Gastineau DA. Self-regulatory fatigue in hematologic malignancies: Impact on quality of life, coping, and adherence to medical recommendations. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. Mar 2013 2020–09-17 2013;20(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9194-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniëls LA, Oerlemans S, Krol ADG, Creutzberg CL, van de Poll-Franse LV. Chronic fatigue in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors and associations with anxiety, depression and comorbidity. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(4):868–874. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henson LA, Maddocks M, Evans C, Davidson M, Hicks S, Higginson IJ. Palliative Care and the Management of Common Distressing Symptoms in Advanced Cancer: Pain, Breathlessness, Nausea and Vomiting, and Fatigue. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020/03/20 2020;38(9):905–914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyszora A, Budzyński J, Wójcik A, Prokop A, Krajnik M. Physiotherapy programme reduces fatigue in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: randomized controlled trial. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017/09/01 2017;25(9):2899–2908. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3742-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klasson C, Helde Frankling M, Lundh Hagelin C, Björkhem-Bergman L. Fatigue in Cancer Patients in Palliative Care—A Review on Pharmacological Interventions. Cancers. 2021;13(5)doi: 10.3390/cancers13050985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mücke M, Mochamat, Cuhls H, et al. Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated with palliative care: executive summary of a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7(1):23–27. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Arndt LA, Pasnau RO. Critical Review of Psychosocial Interventions in Cancer Care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(2):100–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950140018003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ampudia MS, Gastaminza X, Quiles I, et al. Psicopatología y modos de afrontamiento en un grupo de padres de niños enfermos crónicos. Psychopathology and coping among parents with chronically ill children. Revista de Psiquiatría Infanto-Juvenil. 1995 2021–04-26 1995;2:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson RJ, Mata J, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Gotlib IH. Maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms: variations across age and depressive state. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(6):459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng CT, Ho SMY, Liu WK, et al. Cancer-coping profile predicts long-term psychological functions and quality of life in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. Mar 2019;27(3):933–941. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4382-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sumpio C, Jeon S, Northouse LL, Knobf MT. Optimism, Symptom Distress, Illness Appraisal, and Coping in Patients With Advanced-Stage Cancer Diagnoses Undergoing Chemotherapy Treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. May 1 2017;44(3):384–392. doi: 10.1188/17.Onf.384-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SK, O’Donnell JD, Abernethy AP, MacDermott K, Staley T, Samsa GP. Evaluation of Pillars4life: a virtual coping skills program for cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(11):1407–1415. doi: 10.1002/pon.3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Somers TJ, Abernethy AP, Edmond SN, et al. A Pilot Study of a Mobile Health Pain Coping Skills Training Protocol for Patients With Persistent Cancer Pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2015/10/01/ 2015;50(4):553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Society AC. Types of Stem Cell and Bone Marrow Transplants American Cancer Society. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zordan R, Manitta V, Nandurkar H, Cole-Sinclair M, Philip J. Prevalence and predictors of fatigue in haemo-oncological patients. 10.1111/imj.12517. Intern Med J. 2014/10/01 2014;44(10):1013–1017. doi: 10.1111/imj.12517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siddaway A, Wood A, Hedges L. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Anlayses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annual Review Psychology. 2019;70:747–770. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poort H, Onghena P, Abrahams HJG, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Treatment-Related Fatigue in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients on Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: a Mixed-Method Study. Journal: Article in Press. Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings. 2019;doi: 10.1007/s10880-019-09607-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Somers TJ, Kelleher SA, Dorfman CS, et al. An mHealth pain coping skills training intervention for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients: Development and pilot randomized controlled trial. Article. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018;6(3)e66. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Audulv A, Packer T, Hutchinson S, Roger KS, Kephart G. Coping, adaptive, or self managing - what is the difference? A concept review based on the neurological literature. JAN. 2016;72(11):2629–2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Association AP. APA Dictionary of Psychology. “Resilience”. 2021;2021 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute NC. Coping with Cancer. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bigatti SM, Steiner JL, Miller KD. Cognitive appraisals, coping and depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients. Stress Health. 2012;28(5):355–361. doi: 10.1002/smi.2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paek MS, Ip EH, Levine B, Avis NE. Longitudinal Reciprocal Relationships Between Quality of Life and Coping Strategies Among Women with Breast Cancer. Ann Behav Med. Oct 2016;50(5):775–783. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9803-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldwin CM, Sutton KJ, Chiara G, Spiro A 3rd., Age differences in stress, coping, and appraisal: findings from the Normative Aging Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Jul 1996;51(4):P179–88. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.p179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]