Abstract

Immediately downstream from the previously isolated Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 prtB gene coding for a chymotrypsinlike protease activity, an open reading frame, ORF3, was identified which shared significant homology with the highly conserved domains (HCDs) of bacterial methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs). Nucleotide sequencing of this ORF revealed that the gene would code for a protein with a size of approximately 41 kDa. In addition, this sequence contained a domain which was virtually identical to the HCD of a recently characterized MCP, DmcA, of strain 35405. Therefore, this ORF was named dmcB. Northern blot analysis suggested that dmcB was part of an operon structure containing prtB. Insertional inactivation of dmcB utilizing an ermF-ermAM cassette resulted in a mutant with decreased chemoattraction toward nutrient supplements. In addition, the mutant displayed an altered pattern of methylated proteins under conditions of chemotaxis. Inactivation of the dmcB gene also attenuated the methylation of the DmcA protein. These results suggest that the dmcB gene codes for an MCP in T. denticola which may interact with other MCPs in these organisms.

Although a variety of anaerobic microorganisms have been associated with human periodontitis (10), spirochetes are among the most numerous organisms identified in disease sites (17). However, many of these organisms cannot be grown in the laboratory and have yet to be characterized. One of the cultivable spirochetes isolated from diseased tissue is the small spirochete Treponema denticola (6). The presence of these organisms in the oral cavity could be positively correlated with the severity of periodontitis (23). Therefore, these organisms may play a direct role in periodontal inflammation and may also serve as a model organism for characterizing the uncultivable oral spirochetes.

A number of potential virulence properties have been associated with T. denticola, including proteolytic activity, cytotoxicity, immune modulation, and the ability to invade tissue (7). Since the spirochetes are motile organisms and express flagella (5), it is likely that tissue invasion is dependent upon such expression. Likewise, T. denticola displays both positive (13) and negative (4) chemotaxis in vitro, and the former property may play a role in tissue invasion. Motile bacteria normally express mcp and che genes (25) in order to regulate chemotactic behavior. The methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) interact with specific ligands, while the Che proteins relay the appropriate signals from the MCPs to the flagellar motor. Recently, an MCP gene, dmcA, was isolated from T. denticola and characterized (13). This protein was demonstrated to be required for chemotaxis toward nutrients. Moreover, the methylated protein profiles of T. denticola 35405 suggested the presence of other MCPs besides DmcA. The present communication describes the characterization of a second MCP in T. denticola, DmcB, with unique properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

T. denticola ATCC 35405 was maintained and grown in TYGVS broth medium (13) at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Ann Arbor, Mich.) with an 85% N2, 10% H2, and 5% CO2 atmosphere. Escherichia coli JM109 and MCP-deficient RP8611 (13) were utilized as host strains where indicated and were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (19). Plasmid pSA2 containing the dmcB gene (previously named open reading frame [ORF3]) was described earlier (1). T. denticola mutants were grown in TYGVS medium or on agar plates containing the same medium with erythromycin (Erm [40 μg/ml]).

Nucleotide sequencing.

The nucleotide sequence of the dmcB gene was determined by a dideoxynucleotide sequencing strategy (20) with overlapping DNA fragments from the gene subcloned into pUC118, pUC119, or pBluescript II KS+ and KS− (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) (1).

Construction of T. denticola mutants.

A dmcB mutant of strain 35405 was isolated by the strategy recently developed in this laboratory for construction of T. denticola mutants (16). Briefly, an Ermr cassette from plasmid pVA2198 (8) was introduced as a PvuII fragment into the PvuII site of the dmcB gene cloned into plasmid vector pKmOZ18 (21). The resulting plasmid was then linearized with XhoI, and the mixture was electroporated into strain 35405 as recently described (16). Ermr transformants were isolated on TYGVS-Erm agar plates, and purified colonies were selected for further characterization.

A similar strategy was also utilized to construct a prtB mutant (15a).

Expression of the dmcB gene in E. coli.

The intact dmcB gene was isolated by PCR with two primers (5′-GGG GAT CCA AAA ACG GTA GAC GAT TTA-3′, including the sequence immediately upstream from the start codon and containing a BamHI site, as well as 5′-GGG AAT TCT CGT TCA TAC GTC GTT AT-3′, with the sequence immediately upstream of the termination codon, including an EcoRI site) and with plasmid pSA2 as a template under conditions recently described (13). The PCR fragment was then linearized with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into similarly cleaved pUC118. This produced an in-frame fusion between the lacZ′ and dmcB genes under the control of the lac promoter.

Southern blot analysis.

Chromosomal DNA was digested with various restriction enzymes, transferred to nylon membranes, hybridized with the indicated probes, and analyzed as previously described (13) with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) direct labeling and detection systems (Amersham International, Plc., Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Western blot analysis.

For detection of cross-reactive T. denticola proteins with anti-MCP sera, anti-Trg serum (18) (kindly provided by R. Hazelbauer, Washington State University, Pullman) was utilized. This serum recognizes proteins from a broad spectrum of bacteria, including 20 different species. T. denticola or E. coli cell extracts were prepared, run on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels, transferred to Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and analyzed as previously described (13). Equal amounts of sample (micrograms of protein) were loaded in each lane, and the blots were developed with a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-Trg serum.

Northern blot analysis.

RNA was extracted from T. denticola cells by using Trizol LS as described by the supplier (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). Approximately 70 μg of RNA was loaded onto formaldehyde-agarose gels and analyzed as previously described (13) by the ECL system with the indicated probes.

RT-PCR.

RNA from T. denticola was treated with RNase-free DNase (0.2 U of DNase/μg of RNA) in buffer (2) for 2 h at 37°C and extracted with Trizol LS reagent, and the RNA was precipitated with isopropanol. Three to 5 μg of RNA was incubated with random hexamers in PCR buffer-MgCl2-deoxynucleoside triphosphates for 5 min at 42°C. SuperScriptII RT reverse transcriptase (Gibco) was then added, and the mixture was incubated at 42°C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by incubation at 95°C for 5 min, and the mixtures were treated with RNase H at 37°C for 30 min. PCR was then carried out with the indicated primers (denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min and annealing at 64°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min, followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products (10 μl) were loaded onto agarose gels and analyzed as described earlier (12).

Methylation analysis.

Methylation of MCPs in T. denticola was carried out as previously described (13). Cells stimulated with rabbit serum and nutrients were labeled with [3H]methionine, the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the labeled proteins were detected following fluorography.

Chemotaxis assays.

Chemotaxis toward nutrient supplements (serum plus nutrients) was carried out with the two-phase system as previously described (16). Briefly, the top agarose layers containing TYGVS medium and T. denticola cells were overlaid onto the same medium containing serum and glucose. The tubes were incubated at 37°C anaerobically for 7 to 10 days, and migration into the bottom layers was monitored visually.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the dmcB gene has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. U84257.

RESULTS

Characterization of ORF3.

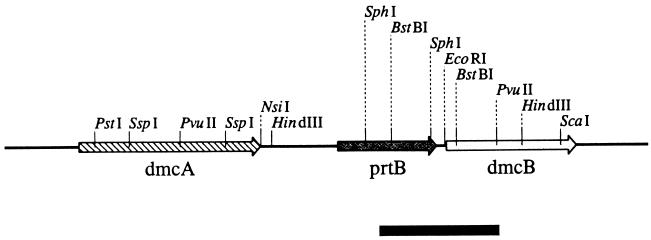

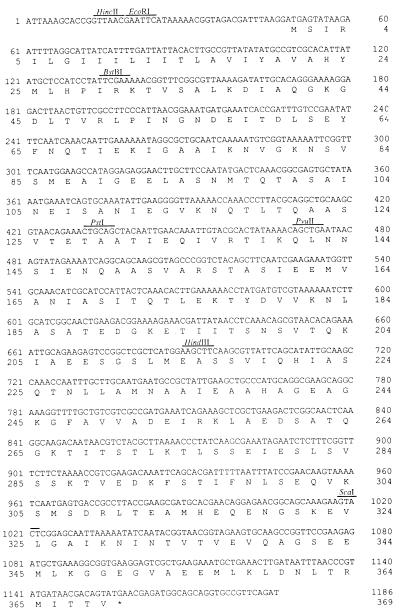

Previously, we isolated a gene, prtB, coding for a chymotrypsinlike protease activity (1) from T. denticola 35405 on plasmid pSA2. Upstream from this gene, another gene, dmcA (Fig. 1), expressing an MCP was identified and characterized (13). Partial sequencing downstream from the prtB gene revealed the presence of another putative gene, ORF3, which has now been completely sequenced (Fig. 2). The gene would code for a protein with an approximate molecular size of 41 kDa. Immediately upstream from the potential start codon, a sequence, AGG, that may act as a ribosome binding site was identified. No sequences corresponding to the consensus promoter sequence of E. coli were identified upstream of the start codon. A Kyte and Doolittle hydropathy plot revealed one significant hydrophobic domain encompassing the N-terminal region of the protein (data not shown). This is in contrast to most bacterial MCPs, which contain two distinct hydrophobic regions (25).

FIG. 1.

Orientation of the dmcA, prtB, and dmcB genes on the T. denticola 35405 chromosome. Bar, 1.0 kb.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the dmcB gene. Major restriction enzyme sites are also indicated. ∗, TGA stop codon.

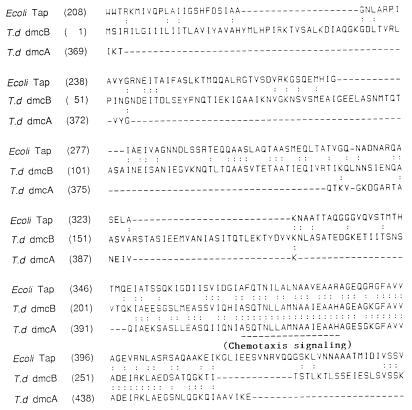

A comparison of the amino acid sequences of ORF3 with sequences in the NBRF database revealed the highest homology with a variety of bacterial MCPs. This homology was confined to the C-terminal chemotaxis signaling regions of these proteins, as exemplified by the E. coli Tap protein (15) (Fig. 3). In addition, this region was highly homologous to a similar domain from the recently characterized T. denticola DmcA MCP. Such similarity suggested the possibility that ORF3 might also code for a protein involved in the chemotactic response of T. denticola. ORF3 also displayed extensive similarity (66% identity at the amino acid level over 348 amino acids) to an uncharacterized ORF (TIGR/TP5582) from the recently released Treponema pallidum genome sequence.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the DmcB protein with those of the E. coli Tap and T. denticola (T.d) DmcA proteins. Conserved amino acid sequences are denoted by the colons. The putative chemotaxis signaling HCD is underlined. The numbers refer to the amino acid positions of each protein.

Expression of ORF3 in E. coli.

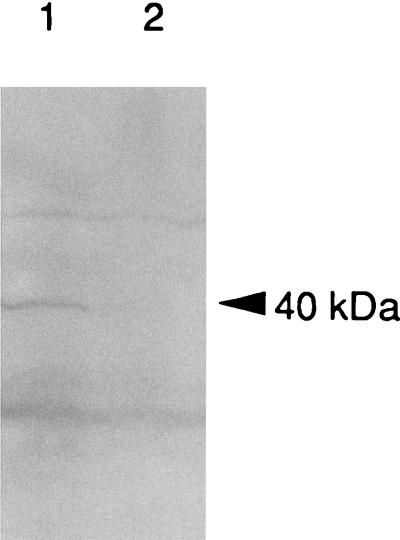

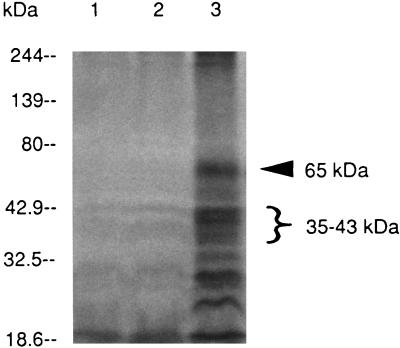

In order to further characterize the ORF3 product, a DNA fragment containing the entire ORF was cloned into the expression vector pUC118. Following induction of ORF3 expression in the presence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), a protein band of approximately 40 kDa was detected following Western blot analysis with antibody against the E. coli Trg protein (Fig. 4), but this band was not detected following protein staining relative to the strain harboring only the vector. A similar-size band was also detected with this antibody from an analysis of proteins expressed from plasmid pSA2 (data not shown). These results suggested that ORF3 codes for a protein with homology to MCPs, such as Trg. Therefore, the ORF was tentatively named dmcB (for denticola MCP B).

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of the expression of the DmcB protein in E. coli. Lanes: 1, E. coli RP8611 containing pUC118/dmcB; 2, RP8611 containing plasmid vector pUC118. The arrows indicate the 40-kDa protein detected with anti-Trg antibody.

Transcription of dmcB in T. denticola.

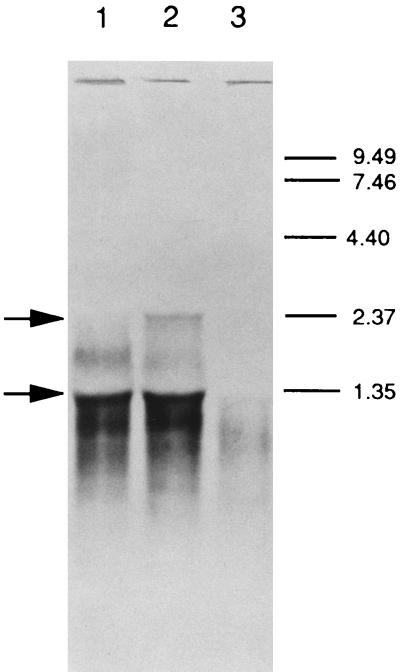

Since an examination of the nucleotide sequence of dmcB and the previously characterized prtB gene did not indicate the presence of a potential promoter sequence upstream of the former gene, it was of interest to determine if the two genes were part of the same polycistronic mRNA. Northern blot analysis (Fig. 5) revealed that strain 35405 expressed a message of approximately 2.3 kb according to a dmcB probe. A similar-size species near 2.0 kb was also indicated for the mRNA detected with the prtB probe (1). An additional positive band at approximately 1.3 kb was also apparent, but its identity is unknown, and it could represent binding of the mRNA to either rRNA or the prtB transcript. Furthermore, RT-PCR analysis using one primer from the prtB gene and another from the dmcB gene revealed a positive band consistent with cotranscription of both genes (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of T. denticola RNA with the dmcB probe. Lanes: 1, dmcB mutant strain HL503; 2, parental strain 35405; 3, prtB mutant strain HL502. Conditions for the analysis are indicated in the text. The arrows indicate the major mRNA species. Molecular size markers (kilobases) are depicted in the right margin.

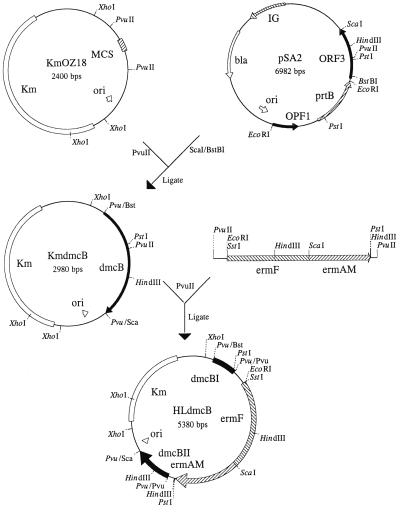

Construction of a dmcB mutant.

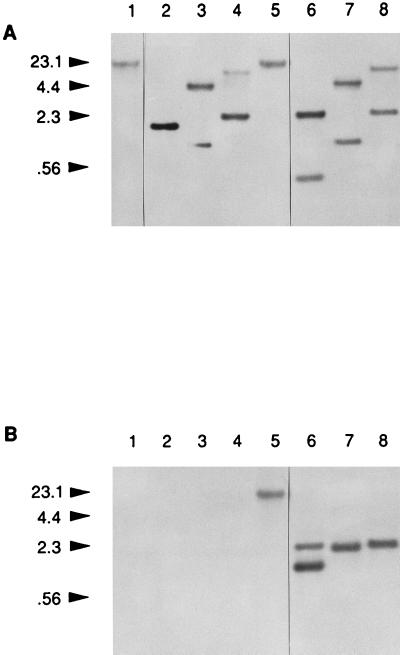

In order to determine the role of the dmcB gene in the physiology of T. denticola, a recently developed gene inactivation system for these spirochetes (16) was utilized to construct a monospecific dmcB mutant (Fig. 6). An Ermr cassette was introduced into the internal PvuII site of the gene, and the linearized plasmid fragment was electroporated into strain 35405. Ermr colonies were isolated, and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 7) confirmed the replacement of the intact dmcB gene with the inactivated copy. Positive bands in one of the selected transformants, HL503, demonstrated the predicted increased sizes when chromosomal DNA was cleaved with several restriction enzymes and examined with a dmcB probe. Likewise, no positive hybridizing bands were detected with the Erm probe in strain 35405, but they were present in mutant HL503. These results confirmed the insertion of the Erm cassette into the dmcB gene in the mutant. In addition, Northern blot analysis of the mutant revealed the disappearance of the 2.3-kb mRNA, but not the 1.3-kb mRNA, following inactivation of the dmcB gene (Fig. 5). Western blot analyses of extracts of the mutants were inconclusive due to the weak cross-reactivity of anti-Trg antibody with the relatively low levels of DmcA and DmcB present in T. denticola.

FIG. 6.

Strategy for constructing the dmcB mutant. The Erm cassette from pVA2198 was introduced into the PvuII site of the dmcB gene (also indicated as ORF3) contained on plasmid pSA2. The resultant plasmid, pHLdmcB, was linearized following XhoI cleavage and utilized to transform strain 35405.

FIG. 7.

Southern blot analysis of the dmcB mutant, HL503. Lanes: 1 to 4, parental 35405; 5 to 8, mutant HL503; 1 and 5, uncut chromosomal DNA; 2 and 6, HindIII cleaved; 3 and 7, PstI cut; 4 and 8, PvuII cleaved. The probe for panel A was the 0.53-kb BstBI-HindIII fragment of the dmcB gene, while that for panel B was the 2.1-kb SstI-PstI fragment from the Erm cassette. The numbers in the left margin indicate the molecular size markers (kilobases).

Properties of the dmcB mutant.

Since the apparent homology of the DmcB protein with MCPs suggested that the protein may play a role in chemotaxis, it was of interest to examine the methylation profiles of mutant HL503. Following stimulation of the parental organism with serum plus nutrients, a number of methylated protein bands were apparent (Fig. 8). A series of bands around 35 to 43 kDa likely represent different methylated forms of DmcB, while the strong band at approximately 65 kDa is the DmcA methylated protein (13). In both the prtB and dmcB mutants, the strong bands in the 40-kDa region were absent, as would be predicted for a role of the DmcB protein in methylation. Interestingly, the DmcA protein was also undermethylated in the mutants. Therefore, inactivation of the dmcB gene attenuated methylation not only of DmcB but also of DmcA. The identities of the other methylated bands are currently unknown. T. denticola may express other MCPs in addition to DmcA and DmcB, as observed in other bacteria (25).

FIG. 8.

Protein methylation patterns of the parental as well as the dmcB and prtB mutants. The cells were prepared and stimulated as described in the text. Lanes: 1, dmcB mutant HL503; 2, prtB mutant HL502; 3, parental strain 35405. The numbers on the left indicate the molecular mass markers. The designations on the right indicate the major proteins which appear to be undermethylated in the mutant strains.

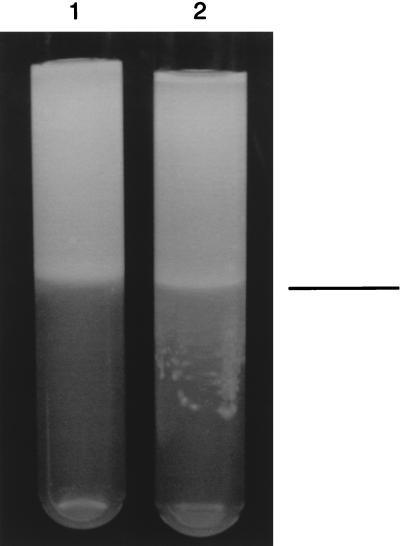

In order to determine if the dmcB gene product plays a role in chemotaxis, mutant HL503 was compared to the parental organism in the agarose-layered chemotaxis system developed in our laboratory (16). Visible migration of parental strain 35405 into the agarose layer containing serum plus nutrients was readily observed (Fig. 9). However, movement of HL503 into this layer was inhibited. These results directly demonstrate that the dmcB gene plays a role in chemotaxis toward nutrients. However, mutant HL503 was not altered in repulsion from agar (16).

FIG. 9.

Chemotactic behavior of the dmcB mutant. Following inoculation of the top layer (TYGVS-agarose) with the bacteria, the migration of the cells into the bottom layer (TYGVS-agarose containing serum and nutrients) was monitored. Tube 1, dmcB mutant strain HL503; tube 2, parental strain 35405. The line in the right margin represents the boundary between the top and bottom layers.

DISCUSSION

The demonstration that oral spirochetes can penetrate oral tissue in inflamed sites (17) suggested that these organisms may contain the chemotaxis genes present in other motile bacteria (25). Previously, it was demonstrated that, at least for one oral spirochete, T. denticola, chemotaxis away from inhibitory agar media could be demonstrated (4). Furthermore, with an adaptation of the latter in vitro assay system, chemotaxis of strain 35405 toward nutrients was confirmed (13). Therefore, it was reasonable to predict that mcp and che genes would be present in these organisms.

The recent isolation and characterization of a chemotaxis gene, dmcA, from strain 35405 suggested the presence of a chemotaxis system in T. denticola (13). The same gene was also recently isolated from a strain 35405 lambda phage clone bank (9). Inactivation of the dmcA gene indicated that this gene was required for chemotaxis toward nutrients, but not for negative chemotaxis relative to inhibitory agar. The present investigation documents the presence of a second chemotaxis gene, dmcB, on the chromosome of strain 35405. This gene is not present within the same operon as dmcA, but it is cotranscribed with the prtB gene, which codes for a chymotrypsinlike protease. However, the latter gene is distinct from the prtP gene, which appears to code for the major cell surface chymotrypsinlike protease in T. denticola (11). Interestingly, the prtB gene is flanked by both the dmcA and dmcB genes. Since genes of similar function are normally clustered together, this arrangement suggests that the prtB gene could play a role in chemotaxis, but this has yet to be established.

One putative domain of the DmcB protein shares extensive homology with the highly conserved domains (HCDs) of many bacterial MCPs. In addition, the HCD of DmcB is virtually identical in amino acid sequence to the same domain in DmcA. The molecular mass of DmcB, approximately 41 kDa, is significantly smaller than that of DmcA, with a revised molecular mass of 70 kDa, as well as those of most other bacterial MCPs (25). However, lower molecular masses have also been suggested for MCPs in other spirochetes (18). It is of interest that a homologous protein of this approximate molecular size has also been detected on the T. pallidum genome. These smaller MCPs may therefore be characteristic of members of the Treponema and other spirochete genera.

Unlike most MCPs, which exhibit two characteristic hydrophobic domains which are believed to span the cytoplasmic membrane (25), the DmcB protein contains only a single hydrophobic domain capable of such orientation. Therefore, it will be of interest to determine how the latter protein is localized in T. denticola relative to the cytoplasmic membrane. Recently, it has been suggested that another MCP, McpA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, also contains only a single large hydrophobic domain (26).

Another unusual feature of the DmcB protein is that inactivation of the corresponding gene also affected the methylation of the DmcA protein. However, the mechanism of such interactions remains to be determined. In addition, these results could indicate that transmethylation between the two proteins may occur in T. denticola. Such interaction between distinct MCPs has also been suggested to occur in Bacillus subtilis (3). The alternative explanation, that inactivation of the dmcB gene somehow affects the expression of the dmcA gene, is suggested by the weak DmcA protein bands observed on Western blots of the dmcB mutant (data not shown). Therefore, it is not clear if the chemotaxis defects displayed by the dmcB mutant resulted directly from an alteration of this gene product or were the result of methylation attenuation of the DmcA protein. Interestingly, inactivation of the dmcA gene does not appear to affect the methylation of the DmcB proteins (13). These results suggest that DmcB may play a unique role as an intermediate in the methylation and regulation of the expression of DmcA or other MCPs. Confirmation of this hypothesis will require additional approaches.

The demonstration of the presence of at least two MCPs in T. denticola, as well as recent reports of the presence of che genes in these organisms (22, 24), suggests that these organisms may contain the same basic complement of chemotaxis proteins which are present in other motile bacteria. The recent development of a gene transfer system for these organisms (16) now makes it possible to determine the role of these genes in chemotaxis as well as in the virulence of these periodontopathic bacteria by utilizing animal model systems (14).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the contribution of M. Kataoka in constructing the lacZ′:dmcB fusion construct.

This investigation was supported in part by grant DE09821 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa S, Kuramitsu H K. Cloning and sequence analysis of a chymotrypsinlike protease from Treponema denticola. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3424–3433. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3424-3433.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer P, Rolfs A, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Hildebrandt A, Fleck E. Use of manganese in RT-PCR eliminates PCR artifacts resulting from DNaseI digestion. BioTechniques. 1997;22:1128–1132. doi: 10.2144/97226st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedale W A, Nettleton D O, Sopata C S, Thoelke M S, Ordal G W. Evidence for methyl group transfer between the methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:223–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.223-227.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan E C S, Qui Y-S, Siboo R, Noble P. Evidence for two distinct locomotory phenotypes of Treponema denticola. ATCC 35405. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10:122–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1995.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charon N W, Greenberg E P, Koopman M B H, Limberger R J. Spirochete chemotaxis, motility, and the structure of the spirochetal periplasmic flagella. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:597–603. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng S-L, Siboo R, Chin Quee T, Johnson J L, Mayberry W R, Chan E C S. Comparative study of six random oral spirochete isolates. Serological heterogeneity of Treponema denticola. J Periodontal Res. 1985;18:602–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1985.tb00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenno J C, McBride B C. Virulence factors of oral treponemes. Anaerobe. 1998;4:1–17. doi: 10.1006/anae.1997.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher H M, Schenkein H A, Morgan R M, Bailey K A, Berry C R, Macrina F L. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the prtH gene. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1521-1528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene S R, Stamm L V. Identification, sequence, and expression of Treponema denticola mcpA, a putative chemoreceptor gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffajee A D, Socransky S S. Microbial etiological agents of destructive periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:78–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishihara K, Miura T, Kuramitsu H K, Okuda K. Characterization of the Treponema denticola prtP gene encoding a prolyl-phenylalanine-specific protease (dentilisin) Infect Immun. 1996;64:5178–5186. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5178-5186.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karunakaran T, Madden T, Kuramitsu H. Isolation and characterization of a hemin-regulated gene, hemR, from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1898–1908. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1898-1908.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kataoka M, Li H, Arakawa S, Kuramitsu H. Characterization of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein gene, dmcA, from the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4011–4016. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4011-4016.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kesavalu L, Walker S G, Holt S C, Crawley R R, Ebersole J L. Virulence characteristics of oral treponemes in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5096–5102. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5096-5102.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krikos A, Mutoh N, Boyd A, Simon M I. Sensory transducers of Escherichia coli are composed of discrete structural and functional domains. Cell. 1983;33:615–622. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Li, H., and H. Kuramitsu. Unpublished data.

- 16.Li H, Ruby J, Charon N, Kuramitsu H. Gene inactivation in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola: construction of an flgE mutant. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3664–3667. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3664-3667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loesche W J. The role of spirochetes in periodontal disease. Adv Dent Res. 1988;2:275–283. doi: 10.1177/08959374880020021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan D G, Baumgartner J W, Hazelbauer G L. Proteins antigenically related to methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins of Escherichia coli detected in a wide range of bacterial species. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:133–140. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.133-140.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato Y, Yamamoto Y, Suzuki R, Kizaki H, Kuramitsu H K. Construction of scrA:lacZ gene fusions to investigate regulation of the sucrose PTS of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;79:339–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi, W. Personal communication.

- 23.Simonson L G, Goodman C H, Bial J J, Morton H E. Quantitative relationship of Treponema denticola to severity of periodontal disease. Infect Immun. 1988;56:726–728. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.726-728.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamm, L. V. Personal communication.

- 25.Stock J B, Lukat G S, Stock A M. Bacterial chemotaxis and the molecular logic of intracellular signal transduction networks. Annu Rev Biophys Chem. 1991;20:109–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward M J, Harrison D M, Ebner M J, Armitage J P. Identification of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]