Abstract

Background

Rapid increase in information on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has led to an infodemic that exposes older adults to a greater risk of anxiety.

Aims

To develop an animated educational video for COVID-19 prevention and management and evaluate its feasibility and preliminary effectiveness in improving knowledge and anxiety levels among older adults.

Methods

A pilot test of feasibility and preliminary effectiveness was conducted in three phases: expert agreement, content validation, and video creation. An intervention group received an animated educational video, whereas a control group received an educational leaflet. A total of 126 respondents were recruited from 15 community health centers in Indonesia.

Results

Results showed that knowledge of intervention group respondents about COVID-19 misinformation improved, and anxiety levels significantly decreased after watching the video compared to the control group (p<0.001).

Conclusions

The animated educational video on COVID-19 prevention and management based on Indonesian preferences successfully improved knowledge and reduced anxiety levels among older adults.

Keywords: Anxiety, COVID-19, Digital education, Infodemic, Older adults

Introduction

The spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)1 has led to health problems worldwide. Based on the data from the Indonesia's Ministry of Health, there was an increase in the incidence of COVID-19, where a total of 6,358,808 positive cases (+4,563 new positive cases) and 157,566 deaths (2.5%) were recorded during the pandemic as of September 01, 2022.2 This high burden of the pandemic continuously posed challenges for healthcare providers and communities in the country. Since 2020, millions of people have been in social isolation, most of whom have easy and fast access to COVID-19 information through the internet and social media. However, information overload during the ongoing pandemic has posed numerous challenges, creating an alarming infodemic of false information,3 conspiracy theories, and instant cures that can potentially increase anxiety and depression.4 It is important to formulate an effective strategy to educate people about COVID-19 prevention and management, especially to older adults who are vulnerable.

In the past two decades, health education has relied on paper-based education; however, it has now shifted towards digital platforms. Growth of interest in advanced technological studies has made multimedia programs more tailored and relevant compared to paper-based education. Moreover, education aimed at COVID-19 prevention and management is an appropriate public health intervention to improve patient knowledge, awareness, and self-care practices. During the pandemic, the Health Belief Model5 was used to explain that older adults are most likely to take preventive action when they perceive a serious threat of a health risk, are personally susceptible and vulnerable, have limited access, and have lower costs than benefits when engaging in the intervention. Phases of the model are described in five stages: pre-contemplation (no intention to make changes), contemplation (intending changes), preparation (acting with small changes), action (actively engaging and being motivated in the new behavior), and maintenance (sustaining the new behavior over time). It was also discovered that delivering information using an attractive method can encourage older adults to become immersed and enter the stage of contemplation and preparation. Meanwhile, the use of an appropriate media platform that considers cultural preferences of older adults is important when delivering education about COVID-19.

An educational method that can be implemented through an electronic platform is the use of animated videos. Due to limited social gatherings and people staying at home, this method could help deliver video-based COVID-19 education effectively to improve the knowledge and change the behavior, as well as attitudes of target audiences, as described in the Technology Acceptance Model.6 This model has been used in several clinical studies to explain the benefits of technology-enabled interventions.7 Various types of educational videos have been developed for different conditions,8 including diabetes,9 cancer,10 hypertension,11 and asthma.12 A recent study using a diabetic foot care educational video confirmed that traditional language videos enhance patients’ knowledge about diabetic foot care.13 Some Indonesian government websites have also embedded educational videos about COVID-19 to improve information access.14

According to Indonesian population statistics, the number of older adults in the country was expected to be approximately 24 million by 2020 and increase by 20% in 2024.15 As an archipelagic country, Indonesia encompasses diverse ethnicities and cultural preferences,13 which could be a barrier to health literacy among older adults.16 Belief and trust have been confirmed as predictors of vaccine acceptance,17 while language was identified as the main barrier to health literacy;18 , 19Adopting cultural preferences for educational videos could help overcome these issues.13 Although several studies have been conducted on COVID-19 videos,20, 21, 22 no educational videos were reported on COVID-19 prevention and management among older adults that included traditional dialogues and animation. Therefore, this study aimed to develop an animated educational video for COVID-19 prevention and management using traditional Sulawesi preferences and evaluate its feasibility and preliminary effectiveness in improving respondents’ knowledge and anxiety levels. A video platform was selected because of its ease of carrying and ability to demonstrate self-care activities. We hypothesized that older adults exposed to the educational video would have better knowledge and reduced anxiety associated with COVID-19 prevention and management than those exposed to routine care.

Material and Methods

Aim

This study aimed to develop an animated educational video for COVID-19 prevention and management using traditional Sulawesi preferences and evaluate its effectiveness in improving respondents’ knowledge and anxiety levels.

Study Design

This study comprised three phases. The first focused on content development and performance of educational videos on COVID-19 prevention and management based on expert discussions. The second phase involved the creation and validation of animated videos. knowledge of COVID-19 information and anxiety levels observed before and after viewing the video using a pre- and post-test design were evaluated in the third phase. A feasibility study using a pre- and post-test design was conducted to evaluate the changes in the respondents’ knowledge and anxiety levels regarding COVID-19 prevention and management after watching the video. The hypothesis was that animated videos would improve the respondents’ knowledge about COVID-19 information and reduce their anxiety levels. The respondents were drawn from 15 community health centers in Kendari City, Southeast Sulawesi, Republic of Indonesia, and were randomly allocated into intervention and control groups. After reaching a consensus, an animated educational video on COVID-19 prevention and management in Indonesia was created with the assistance of a multimedia expert. The content was based on the target users’ preferences, cultures, and languages. Sketches were drawn using Articulate Storyline version 2.0 (Articulate Inc, US), while animation and music were embedded in the video. After its creation, six experts (three medical doctors, two nurses, and one epidemiologist) were invited to qualitatively review the video content and features.

Sample Section

Participants

Participants from 15 community health centers, consisting of men and women aged >60 years, were enrolled in this study. During selection and recruitment, baseline information of the participants was assessed by nurses and general practitioners. The participants were asked to explain their history of illness, daily habits, and knowledge of COVID-19. A total of 10 experts, including three medical doctors (one cardiologist, one surgeon, and one psychiatrist), two nurses with expertise in gerontology, two epidemiologists, one clinical pharmacist, and two multimedia designers were invited to discuss content development for the animated educational video on COVID-19 prevention. The experts were required to have a minimum of two years of work experience in gerontology. Written informed consent was obtained from the assistant before the discussion. Literature on the national COVID-19 guidelines was obtained from the Ministry of Health in Indonesia2 to construct the contents and evaluate the performance of video-based COVID-19 education. The Health Belief Model was used to construct the educational content, including health, myths, and beliefs. The experts were sent a questionnaire via email and WhatsApp, containing 20 questions related to the video content and seven video performance-related questions (Facebook Inc., CA, US). Responses were evaluated using a four-point Likert scale, including very irrelevant, irrelevant, relevant, and very relevant. All the experts completed the responses independently and returned their rating scores online. Moreover, all obtained scores on a four-point Likert scale were assessed using the content validity index (CVI) for each item (I-CVI) and were defined as the proportion of experts who rated an item as content valid (relevant or very relevant). The responses were quantified using the content validity index (CVI)23 cutoff of 80% for cumulative “relevant” and “very relevant” responses. Based on this technique, consensus was determined using accepted statements. An I-CVI of 0.80 (80% of the statement's agreement) was considered valid when assessed by ten experts.

Recruitment

General practitioners and nurses at community health centers accompanied the recruitment process. Potential eligible participants were identified using an electronic system database from community health centers. Furthermore, participation was voluntary, the participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time, and there were no adverse events in their medical treatments. Inclusion criteria were as follows: aged 60 years or older, able to communicate without difficulty, pose with a smartphone/tablet/computer and watch videos, and willing to provide consent to participate. Meanwhile, exclusion criteria included presence of serious cognitive impairment, no access to or experience in using technology, and failure to follow research instructions, including how to use a smartphone and how to open a video file. We obtained information on whether the respondents had a history of cognitive impairment or not from the collection of demographic data. The study team provided an explanation on the study and written informed consent was obtained before enrollment. The Declaration of Helsinki's ethical criteria were followed in this study and are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Sample Size

The sample size was estimated using G-Power (version 3.1, Franz Faul, Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel, Germany),24 based on 80% power. The intervention and control groups were assigned using a 1:1 ratio with an anticipated dropout rate of 20% for both groups. A total of 63 participants were required to evaluate differences in their knowledge scores and anxiety levels.

Randomization

The participants were randomized using a computer-generated random sequence software, RANDOM.org. An independent statistician generated a random sequence. After the sequence number appeared, the numbers were placed in sealed opaque envelopes in a secured box. The envelopes were opened in front of the enrolled participants by a research assistant who did not contribute to the process of providing information about the group assignment.

Intervention Group

After the group assignment, an animated COVID-19 educational video was provided for the intervention group, whereas an educational leaflet was provided for the control group. Both resources included similar information, including the definition of COVID-19, its transmission, risk factors, symptoms, mask use, hand washing, physical distancing, and spiritual activities. The video was free to download, and the participants were able to watch it without any time or location restrictions. The assistant helped the respondents to download the video on their computers/tablets/smartphones. To minimize bias, the assistant who helped in the recruitment process was not involved in the delivery of education and outcome measures. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding was not considered in this procedure.

Control Group

The participants in the control group received a COVID-19 educational leaflet. A trained assistant provided standard COVID-19 education and spent approximately 30 minutes explaining the leaflet to the participants. Subsequently, participants were contacted via telephone and asked for feedback about the COVID-19 educational video content. Both groups were provided incentives and souvenirs after completing the questionnaire.

Study Procedure

Before Research

Before conducting the study, a certified health educator trained the research team. A digital-based intervention, involving healthcare providers delivering patient education and counseling during the COVID-19 pandemic, was also evaluated.

Baseline (Time 0)

A research assistant called the participants via telephone before their clinic appointment to reintroduce the study and provide sufficient time to complete the baseline assessment, which lasted approximately 10–15 minutes. During the assessment, the research assistant was able to answer questions and assist participants with reading when necessary. Before randomization, baseline measurements were collected, which included information from medical records, including demographic characteristics, knowledge, and anxiety scores.

Delivering the Intervention

The video and leaflet were delivered to all the participants in both groups for 30 minutes in 15 community health centers and mainly covered the information on COVID-19 prevention and management. The participants were asked to watch different videos and spend approximately 30 minutes watching the series at home for the next seven days.

Follow-Up (Time 1)

After delivering the educational materials to the intervention and control groups, the participants were followed-up for one week, and their knowledge and anxiety scores were assessed using questionnaires to evaluate the effectiveness of digital-based health education for COVID-19. The assistant called the participants via telephone to ensure compliance. After completing the study period, the participants gained benefits such as cash rewards and a certificate of participation.

Measure Outcomes

Geriatric Anxiety Inventory

The primary outcome was anxiety level among older adults. The 20-item Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) was developed by Pachana et al. (2007) to screen for anxiety among older adults. This instrument was commonly used to measure dimensional anxiety and could be a self-reported or health provider-administered measure.25 The Indonesian version of the GAI-20 was used in this study with the University of Queensland's permission, which comprises 20 questions with “agree” or “disagree” as responses. The GAI-20 has no reverse-scored items and each item receives a score of one. The total scores range between 0.0–20.0, with a score of 9.0 indicating the presence of clinically significant anxiety, leading to a higher score on the GAI, which represents greater anxiety. Cronbach's alpha for the original version of the GAI is 0.91. This Indonesian GAI-20 questionnaire was delivered to older adults before and after they had watched the animated video and was required to be completed in 10 minutes. The scale and license for using the GAI are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Coronavirus Knowledge Assessment Form

The COVID-19 knowledge assessment form was developed based on the consensus of 10 experts. Knowledge was measured as secondary outcome, and 17 questions were formulated from the discussion. Furthermore, COVID-19 knowledge was assessed by a research assistant to measure patients’ knowledge before and after the intervention. The assessment form consisted of 17-item questions on COVID-19 prevention rated on a five-point Likert scale, including, “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” The form had reverse-scored items, where some items were considered positive statements, such as item numbers 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 14, while others were considered negative statements, including item numbers 2, 8, 13, 15, 16, and 17. The range of acceptable scores for the positive statements of items 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 14 was 11–22, which was considered a true answer. When the score was >22, it was considered a false answer. The range for the negative statements of items 2, 8, 13, 15, 16, and 17 was 24–30, which was considered a true answer, and when the scores were <24, it was considered a false answer, as presented in Table 1 . The results show a validity value of 0.63 and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.70. The form is provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Table 1.

Interpretation of mean of knowledge.

| Score mean | Interpretation of mean score | Score | Item number | Conclusive interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-22 | Strongly agree, agree (positive statement) | Strongly agree = 1, Agree = 2 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 14 | The older adults responded with strongly agree and agree to X statement |

| 24-30 | Strongly disagree, disagree (negative statement) | Strongly agree = 5, Agree = 4 | 2, 8, 13, 15, 16, and 17 | The older adults responded with strongly disagree and disagree to X statement |

The mean scores for the positive and negative statements were 5.5 and 15, which indicated strong agreement and disagreement, respectively. An interpretation was considered knowledgeable, and consisting of positive and negative statements when the respondents had scores of 11–22 and 24–30, respectively. An interpretation was considered non-knowledgeable, and consisting of positive and negative statements when the respondents’ scores were >22 and <24, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of the numbers, percentages (%), means, and standard deviations were conducted to measure the baseline characteristics of the participants and experts. The CVI was used to evaluate each video content and performance item in the first round, which satisfied the cutoff of CVI >80%.13 Subsequently, paired, and independent t-tests were used to compare the participants’ knowledge on COVID-19 and their anxiety scores before and after the intervention. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Mac (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A single imputation method was used to handle multiple scale items that were blank due to unintentional negligence of the older adults.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the ten experts who participated in the discussions conducted between May and June 2021 are presented in Table 2 . Based on the COVID-19 guidelines, the video contents included definition, virus information, causes, transmission, symptoms, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), virus incubation period, vulnerable populations, general hand washing techniques, duration of hand washing, step-by-step hand washing technique, mask use, physical distancing measures, call centers for emergency conditions, vitamin supplies, herbal supplements, anxiety reduction techniques, and spiritual activities conducted during the pandemic. The video performance components covered language (comprehension and style), use of brief sentences, familiar dialogue and phrases, clear and friendly voices, explanations of complex concepts, and communication. This content was compiled and sent to experts to measure its relevance using a Likert scale. The cumulative threshold for agreement was set at ≥80%;13 therefore, COVID-19 content that achieved a percentage of ≥80% was included based on the agreement result, indicating the cumulative relevant and very relevant items, as well as the CVI, as presented in Table 3 .

Table 2.

The demographic characteristics of the experts (N = 10).

| Characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) (years) | 37.5 (3.75) |

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Male | 6 (60) |

| Female | 4 (40) |

| Level of education | |

| Undergraduate | 4 (40) |

| Postgraduate | 6 (60) |

| Institution | |

| Education | 6 (60) |

| Hospital | 2 (20) |

| Health community center | 2 (20) |

Demographic characteristics of the experts

Table 3.

Content validity index for the development of animated educational COVID-19 video.

| No | Elements | Likert scale (%) |

Cumulative agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very irrelevant | Irrelevant | Relevant | Very relevant | |||

| Video contents | ||||||

| 1 | COVID-19 definition | 30 | 70 | 100 | ||

| 2 | COVID-19 virus | 60 | 40 | 100 | ||

| 3 | COVID-19 causes | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| 4 | COVID-19 transmission | 30 | 70 | 100 | ||

| 5 | COVID-19 symptoms | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| 6 | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 90 | 10 | 100 | ||

| 7 | Virus incubation period | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| 8 | Vulnerable population | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| 9 | Hand washing technique | 20 | 80 | 100 | ||

| 10 | Duration of hand washing | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| 11 | Step by step of hand washing technique | 10 | 40 | 50 | 90 | |

| 12 | Using a mask | 20 | 80 | 100 | ||

| 13 | Physical distancing | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| 14 | How to do physical distancing | 30 | 70 | 100 | ||

| 15 | Physical distancing measures | 10 | 40 | 50 | 90 | |

| 16 | Emergency call centres | 30 | 60 | 10 | 70 | |

| 17 | Vitamin for immune booster | 10 | 70 | 20 | 90 | |

| 18 | Herbs supplements | 30 | 60 | 10 | 70 | |

| 19 | How to reduce anxiety | 10 | 60 | 30 | 90 | |

| 20 | Spiritual activities during the pandemic | 20 | 50 | 30 | 80 | |

| Video performance | ||||||

| 1 | Using simple, national language | 20 | 80 | 100 | ||

| 2 | Using brief sentences | 10 | 20 | 70 | 90 | |

| 3 | Using familiar sentences | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| 4 | Using clear voice | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| 5 | Explaining complex things | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| 6 | Using friendly language and cultural habits | 30 | 70 | 100 | ||

| 7 | Communicative | 30 | 70 | 100 | ||

The Content Validity Index (CVI)

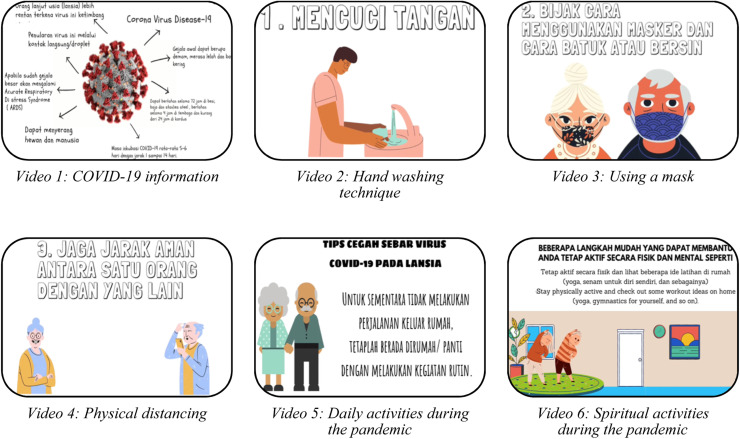

Animated Educational Video

After an agreement, the 18 contents were considered relevant and very relevant for COVID-19 prevention and management, including COVID-19 definition, the virus, causes, transmission, symptoms, acute respiratory distress syndrome, virus incubation period, vulnerable population, hand washing technique, duration of hand washing, step-by-step approach of hand washing, use of a mask, physical distancing, physical distancing, a vitamin for immune booster, reduction of anxiety, and spiritual activities during the pandemic. Screenshots of an educational video created using animation and cartoon characters representing older adults are shown in Fig. 1 . The video was created in July 2021 in the MP4 file (.mp4) format and its properties were a size of 74.1 MB, length of 5.49 minutes, frame width of 1920 pixels, frame height of 1,080 pixels, data rate of 1,642 kbps, audio bit rate of 127 kbps, and an audio sample rate of 44.100 kHz. The qualitative feedback for the COVID-19 video performance is presented in Table 4 . Six experts with diverse expertise reviewed the video performance and provided feedback on aspects, such as duration, animation, audio and music, material, layout and intonation.

Fig. 1.

Video content.

Table 4.

Qualitative feedback for the COVID-19 video performance.

| No. | Reviewers | Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Physicians (Dr. R, Dr. E, Dr. S) |

|

| 2 | Nurses (P, A) |

|

| 3 | Public health expert (S) |

|

Qualitative feedback

Outcomes

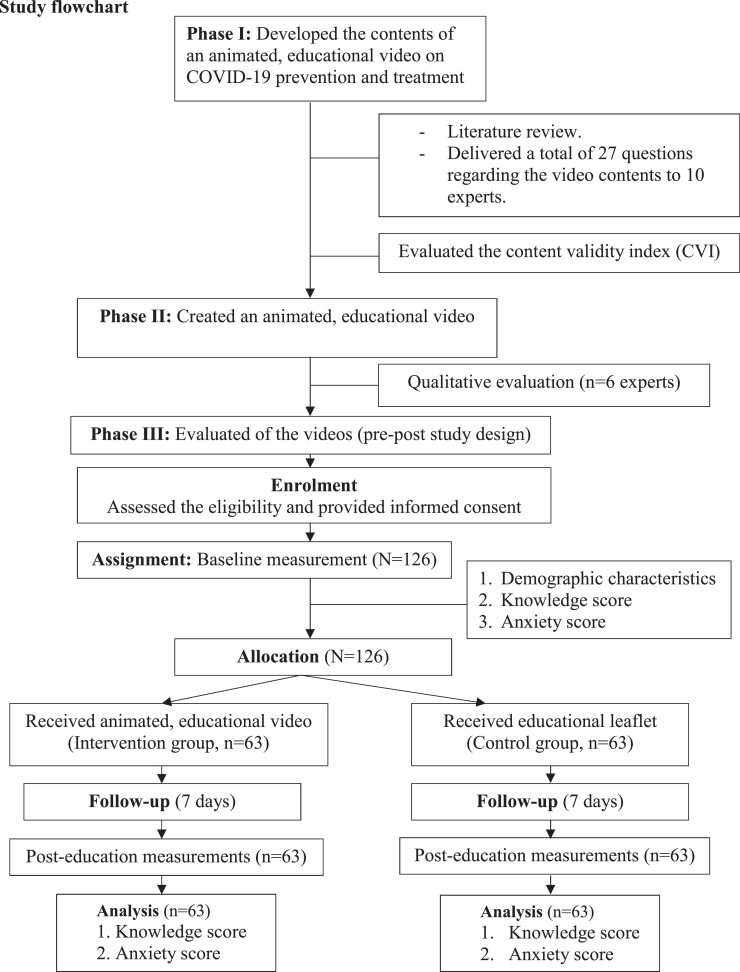

Fig. 2 illustrates the flowchart of the study. A pilot study was conducted from August to September 2021, and the baseline characteristics of the older adults in both groups are shown in Table 5 . A total of 126 respondents were recruited and allocated to the intervention and control groups after obtaining their informed consent. Each group comprised older adults aged between 65–67 years old, and 80% of the respondents had completed their education. The changes in respondents’ knowledge scores for COVID-19 information and anxiety are presented in Table 6 . Compared to the control group, the intervention group's knowledge about COVID-19 misinformation and mean score of anxiety significantly decreased from 44.05 (±8.26) to 38 (±5.89) and 9.27 (±4.40) to 3.59 (±1.92), respectively, after watching the animated video (p<0.001). Treatment fidelity was evaluated by monitoring the delivery of animated videos to older adults, as noted in Table 7 . The two aspects that must be considered, included delivery and receipt.26 For delivery of treatment, this study addressed four goals, namely control for health care professional differences, decreasing differences within treatment, ensuring adherence to treatment protocol, and reducing contamination between situations. Three goals that were emphasized to monitor the receipt of treatment included ensuring older adults’ comprehension, ability to apply their cognitive skills, and performing behavioral skills.

Fig. 2.

Study flowchart.

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics of older adults.

| Characteristics | Intervention group (n=63) | Control group (n=63) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||

| Mean (±SD) | 66.6 (±7.5) | 65.3 (±5.3) |

| Sex (n, %) | ||

| Male | 30 (47.6) | 34 (54.0) |

| Female | 33 (52.4) | 29 (46.0) |

| Level of education (n, %) | ||

| Educated | 50 (82.5) | 49 (77.8) |

| Uneducated | 13 (17.5) | 14 (22.2) |

| Income/month ($USD) | ||

| Mean (±SD) | 111.76 (±181.64) | 94.25 (±76.95) |

Baseline characteristic of older adults (N=126)

Table 6.

Changes in the respondents’ knowledge on the COVID-19 misinformation and anxiety.

| Variables | Pre Mean (±SD) | Post Mean (±SD) |

Mean Difference | t | df | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | |||||||

| Knowledge | 44.05 (±8.26) | 38 (±5.89) | 6.048 | 4.730 | 124 | 3.52 – 8.58 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 9.27 (±4.40) | 3.59 (±1.92) | 5.683 | 9.393 | 124 | 4.49 – 6.88 | <0.001 |

| Control group | |||||||

| Knowledge | 44.49 (±6.78) | 41.83 (±4.85) | 2.667 | 2.540 | 124 | 0.59 – 4.75 | 0.012 |

| Anxiety | 5.89 (±4.69) | 4.48 (±4.59) | 1.413 | 1.709 | 124 | -0.22 – 3.05 | 0.090 |

Measures of the knowledge and anxiety level

Table 7.

Treatment fidelity strategies for monitoring delivery of animated video for older adults.

| Goal | Description | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring delivery | ||

| Control for provider differences | Providers should control the potential effect of subject perception. | Before conducting the study, research assistants who delivered the video and assessed the outcomes got a training from the researchers to improve their communication with older adults. Research assistants also encouraged the participants to fill the questionnaire by their selves (self-report questionnaire). |

| Reduce differences within treatment | Providers should ensure that their information were same to both groups. | Research assistants were trained by a certified nurse in the same room. When delivering the information, research assistants carried a checklist of information that they should deliver and should be able to record their presentation in a short video. A checklist and a video presentation were checked by a certified nurse (supervisor) to ensure that both groups received the same information from the same providers. |

| Ensure adherence to treatment protocol | Providers should adhere to treatment protocol. | Before conducting the study, a certified nurse discussed with research assistants regarding each action to ensure that all research members adhere to treatment protocol. After delivering the information, a nurse called the research assistants to collect their feedback and check for any errors or the next follow-up to participants. |

| Minimize contamination between condition | Providers should ensure the minimal contamination across two groups. | We randomized the participants into two groups using a random generator software with the involvement of a statistician (not considered as the research team to minimize the contamination). All presentation materials were printed for the control group and ensured that it consisted of the same information with the intervention group (checked by another nurse in the research team). Both groups were taught in the separate day and location. A certified nurse supervised the research assistants’ works frequently (2 times in a week). |

| Monitoring receipt | ||

| Ensure participant comprehension | Providers should ensure the participants to understand the information presented in the animated video due to their low level of education and no ability to speak in English. | A pre- and posttest technique and knowledge measures were assessed. All participants in the intervention group received the video and a research assistant accompanied them to watch the video for the first time. A research assistant called the participants once after 1 week of the intervention to ensure that participants watched the video (intervention group) and read the booklet (control group) for 1 week, and understand the information. |

| Ensure participant ability to use cognitive skills | Providers should ensure the participants to apply the cognitive skills delivered in the animated video (preparing for high-risk situation of COVID-19 pandemic). | This video was created with the involvement of an expert panel and it was reviewed by the experts. We provided a knowledge assessment form for the participants and collect their feedback regarding physical distancing and avoiding the crowd situation. |

| Ensure participant ability to perform behavioral skills | Providers should ensure the participants to perform the behavioral skills taught in the animated video (physical distancing, wear a mask, use hand sanitizers, etc). | A research assistant accompanied the participants to perform the ability to wash their hands, wear a mask, use hand sanitizers, do a relaxation, do a social interaction using a digital platform (a videoconference or a message system). The researchers assessed their anxiety level using a questionnaire. |

Discussion

This study aimed to develop an animated educational video on COVID-19 information in three phases: expert discussion, video production, and validation using a pre-and post-test method. This aim was motivated by the need for COVID-19 education among older adults to change their behavior, reduce the effects of the infodemic, and decrease anxiety levels regarding transmission of the virus. The questionnaires were distributed online via Google Forms, and discussions were conducted using the WhatsApp application, a method used in video-based interventions in several studies.13 , 27 Using the Abrar et al. (2020) method, 18 relevant topics on COVID-19 prevention and management were identified.

After using a CVI that involved experts, the objectives of the educational video were explained to the respondents through a step-by-step approach explained from the beginning to end of the video, including a proper hand washing technique, mask use, and physical distancing techniques, which older adults could implement. Qualitative feedback from six experts indicated that the videos needed to engage older adults with diverse beliefs and literacy skills, be attractive, educational, clear, and communicative, and the content needed to be easily understood by the audience. The animation must represent older adults in Indonesia for greater relatability. Techniques related to hand washing, mask use, physical distancing, maintenance of well-being, and mental health must be continually delivered. Moreover, educating older adults about issues associated with COVID-19 is pivotal because of their vulnerable health status, comorbidities, lack of education, and rapid increase in misinformation on social media.

The results of the pre- and post-test studies revealed that after watching the educational video, knowledge on COVID-19 improved and anxiety symptoms reduced in the intervention group compared with the control group, showing effectiveness of the animated educational video on COVID-19. This was in line with a previous report, which stated that video-based education could better facilitate patients’ knowledge and attitudes than paper-based education.28 It was also reported that educational videos are one of the best tools for improving knowledge using a simple platform and have garnered a high level of satisfaction within various areas of healthcare.29 The pre-test assessment of anxiety levels in the control group revealed a score of <9.0, indicating that the participants in the control group were less anxious than those in the intervention group.

Strengths

The novelty of this study lies in the development of an animated educational video for older adults using the expert consensus of individuals working in clinical and public health roles in various Indonesian provinces. It also involved obtaining information from the literature on COVID-19 guidelines, which encompassed national needs and health care perspectives. The educational video considered cultural preferences, especially the cultural practices of South-East Sulawesi, to overcome barriers, beliefs, and myths regarding COVID-19-related topics. Evidence shows that patients’ knowledge increases after receiving health education based on their cultural preferences. The use of cultural preferences has been recommended for health education,30 as they facilitate comprehension in older adults and enhance knowledge transfer.

Limitations

This study has few limitations. First, vaccination information was not included to overcome participants’ vaccine hesitancy. Second, a subgroup analysis of participants with comorbidities was not performed, making it difficult to determine the effect on knowledge transfer. Moreover, the sustainable behavior of self-management practices was not evaluated when conducting new normal activities among the participants. This has led to ambiguity regarding the long-term effectiveness of animated educational videos on knowledge and attitude improvements. It was discovered that the participants intended to engage in and practice living a new normal life after watching the video. Finally, this study focused on older adults, and the use of such health education videos in other demographics needs to be examined in future investigations.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Further Research

The results can be used by physicians, nurses, healthcare providers, and community members to help older adults follow best practices for COVID-19 prevention and management. This is because animated videos can be used to engage older adults and decrease the burden of paper-based education, which includes lack of attractive content and attention. In future investigations, these videos can be used as interventions in clinical trials to evaluate behavioral changes related to COVID-19 prevention and management among older adults, including live demonstrations of proper handwashing techniques, mask use, and physical distancing. Vaccination information can also be embedded in a video to reduce vaccine hesitancy and enhance the motivation to be vaccinated.

Conclusion

An animated educational video on COVID-19 prevention using cultural adaptation was developed to overcome communication barriers during knowledge transfer and reduce anxiety regarding COVID-19 among older adults. The results showed that the video effectively improved the respondents’ knowledge on COVID-19 misinformation and reduced anxiety among older adults. Therefore, animated videos can be used as efficient tools to deliver health education during future disease outbreaks or pandemics.

Contribution ship

SS, and AS contributed to the literature search and conceptualization of the manuscript. SS, AS, IS, and SK contributed to data collection, data analysis, and visualization. SS and AS wrote the original draft. IS, JS, DA, SK, BD, and SH contributed to validation and review of the manuscript. SS, AS, dan IS, BD contributed to editing and supervision. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all experts, multimedia designers, and statisticians who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.10.015.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Satuan Tugas Penanganan COVID-19. Peta Sebaran Jakarta. 2021 https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran 2021Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2021). Infeksi emerging. Retrieved from https://infeksiemerging.kemkes.go.id/

- 3.Mheidly N., Fares J. Leveraging media and health communication strategies to overcome the COVID-19 infodemic. J Public Health Policy. 2020;41(4):410–420. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00247-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathore F.A., Farooq F. Information overload and infodemic in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(Suppl 3):S162–S1s5. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.38. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alagili DE, Bamashmous M. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework for COVID-19 prevention practices. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(10):1398–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winter S.J., Sheats J.L., King A.C. The use of behavior change techniques and theory in technologies for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment in adults: A comprehensive review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(6):605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J., Park H.A. Development of a health information technology acceptance model using consumers' health behavior intention. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e133. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winston K., Grendarova P., Rabi D. Video-based patient decision aids: A scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(4):558–578. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Litvinova M., Liang Y., Wang Y., Wang W., Zhao S., Yu H. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;368(6498):1481–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf P.G., Manero J., Harold K.B., Chojnacki M., Kaczmarek J., Liguori C., Arthur A. Educational video intervention improves knowledge and self-efficacy in identifying malnutrition among healthcare providers in a cancer center: A pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(2):683–689. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04850-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahyuni A.S., Amelia R., Nababan I.F.F., Pallysater D., Lubis N.K. The difference of educational effectiveness using presentation slide method with video about prevention of hypertension on increasing knowledge and attitude in people with the hypertension risk in amplas health center. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(20):3478–3482. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleath B., Carpenter D., Davis S.A., Lee C., Garcia N., Reuland D.S., …Loughlin C.E. The impact of a question prompt list and video intervention on teen asthma control and quality-of-life one year later: Results of a randomized trial. J Asthma. 2020;57(9):1029–1038. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1633542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrar E.A., Yusuf S., Sjattar E.L., Rachmawaty R. Development and evaluation educational videos of diabetic foot care in traditional languages to enhance knowledge of patients diagnosed with diabetes and risk for diabetic foot ulcers. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(2):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2021). COVID-19 situation. Retrieved from: https://www.kemkes.go.id/

- 15.Badan Pusat Statistik. (2021). Hasil Sensus penduduk 2021 Retrieved from https://www.bps.go.id/website/images/se2016/indo/sensus-penduduk-2020.jpeg.

- 16.Indrayana S., Guo S.E., Lin C.L., Fang S.Y. Illness perception as a predictor of foot care behavior among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Indonesia. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(1):17–25. doi: 10.1177/1043659618772347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullah I., Khan K.S., Tahir M.J., Ahmed A., Harapan H. Myths and conspiracy theories on vaccines and COVID-19: Potential effect on global vaccine refusals. Vacunas. 2021;22(2):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vacun.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson J.K., Guzman S.J., Maryniuk M.D., O'Brian C.A., Kadohiro J.K., Jackson R.A, Funnell M.M. The use of language in diabetes care and education. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(6):551–564. doi: 10.1177/0145721717735535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vida Estacio E., McKinley R.K., Saidy-Khan S., Karic T., Clark L., Kurth J. Health literacy: Why it matters to South Asian men with diabetes. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(2):214–218. doi: 10.1017/S1463423614000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy N.R., Steinberg A., Arnold R.M., Doshi A.A., White D.B., DeLair W., Elmer J. Perspectives on telephone and video communication in the intensive care unit during COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(5):838–847. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-729OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negro A., Mucci M., Beccaria P., Borghi G., Capocasa T., Cardinali M…, Zangrillo A. Introducing the video call to facilitate the communication between health care providers and families of patients in the intensive care unit during COVID-19 pandemia. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;60 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viswanathan R., Myers M.F., Fanous A.H. Support groups and individual mental health care via video conferencing for frontline clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(5):538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almanasreh E., Moles R., Chen T.F. The medication discrepancy taxonomy (MedTax): The development and validation of a classification system for medication discrepancies identified through medication reconciliation. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(2):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faul E., Buchner Lang. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1. Test Correlat Regress Anal. 2009 doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pachana N.A., Byrne G.J., Siddle H., Koloski N., Harley E., Arnold E. Development and validation of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory. Int Psychogeriat. 2007;19(1):103–114. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellg AJ., Borrelli B., Resnick B., Hecht J., Minicucci DS., Ory M., et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change ConsortiumHealth. Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caro-Bautista J., Martín-Santos F.J., Villa-Estrada F., Morilla-Herrera J.C., Cuevas-Fernández-Gallego M., Morales-Asencio J.M. Using qualitative methods in developing an instrument to identify barriers to self-care among persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(7-8):1024–1037. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpenter D.M., Alexander D.S., Elio A., DeWalt D., Lee C., Sleath B.L. Using tailored videos to teach inhaler technique to children with asthma: Results from a school nurse-led pilot study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(4):380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suarez Mora A., Madrigal J.M., Jordan L., Patel A. Effectiveness of an educational intervention to increase human papillomavirus knowledge in high-risk minority women. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22(4):288–294. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latif S., Ahmed I., Amin M.S., Syed I., Ahmed N. Exploring the potential impact of health promotion videos as a low cost intervention to reduce health inequalities: A pilot before and after study on Bangladeshis in inner-city London. London J Prim Care (Abingdon) 2016;8(4):66–71. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2016.1208382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.