Abstract

KRAS is the most frequently mutated oncogene in solid cancers, and inhibitors that specifically target the KRAS-G12C mutant were recently approved for clinical use. The limited availability of experimental data pertaining to the sensitivity of KRAS-non-G12C mutants towards RAS inhibitors made it difficult to predict the response of KRAS-mutated cancers towards RAS-targeted therapies. The current study aims at evaluating sensitivity profiles of KRAS-non-G12C mutations towards clinically approved sotorasib and adagrasib, and experimental RAS inhibitors based on binding energies derived through molecular docking analysis. Computationally predicted sensitivities of KRAS mutants conformed with the available but limited experimental data, thus validating the usefulness of molecular docking approach in predicting clinical response towards RAS inhibitor treatment. Our results indicate differential sensitivity of KRAS mutants towards both clinical and experimental therapeutics; while certain mutants exhibited broad cross-resistance to most inhibitors, some mutants showed resistance towards specific inhibitors. These results thus suggest the potential of emergence of more resistance mutations in future towards RAS-targeted therapy and points to an urgent need to develop novel classes of inhibitors that are able to overcome both primary and secondary drug resistance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-022-03407-9.

Keywords: KRAS protein, RAS inhibitors, Sotorasib, Adagrasib, Drug sensitivity, Non-G12C mutations

Introduction

Activating mutations in RAS oncogene occurs in about 25–30% of human cancers (Hobbs et al. 2016; Han et al. 2017). Among the three isoforms, KRAS (85%) is the most frequently mutated isoform followed by NRAS (12%) and HRAS (3%) (Simanshu et al. 2017). Individual RAS isoforms show specific association with particular cancer types: KRAS is frequently mutated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (86%), lung adenocarcinomas (32%) and colorectal cancer (41%), while NRAS is predominantly mutated in melanoma (29%), and HRAS mutations are frequently found in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (5%) and bladder cancer (6%) (Moore et al. 2020). Additionally, RAS isoforms also differ in codon-specific as well as substitution-specific mutation frequencies: KRAS harbours 81.5% of its mutations at codon 12 (G12D: 33.4%, G12V: 22.8% and G12C: 11.3%), 14% at codon 13 (G13D:12.4%) and 2.2% at codon 61 (Q61X) (O’Bryan 2019). In contrast, NRAS harbours 62% and 23% of its mutations at codon 61 and codon 12, respectively (O’Bryan 2019). Notably, HRAS shows similar frequencies at all the three codons 12, 13 and 61 (O’Bryan 2019). Targeting KRAS through its nucleotide binding pocket proved difficult because of high cellular concentrations of GTP as well as very high affinity of KRAS for GTP (Nagasaka et al. 2020). Furthermore, lack of additional hydrophobic pockets made KRAS undruggable for a long time, until the recent discovery of Switch-II pocket (S-II pocket), to which inhibitors such as sotorasib and adagrasib bind and form a covalent bond with the cysteine residue of the G12C mutant (McCormick 2020). These drugs were clinically approved for the treatment of KRAS-G12C mutant cancers, but the effect of these inhibitors towards non-G12C mutants of KRAS are largely not determined. More importantly, emergence of secondary mutations resulting in resistance towards RAS inhibitors are increasingly reported suggesting an urgent need to develop new inhibitors that address this clinical challenge (Awad et al. 2021; Tanaka et al. 2021). For example, secondary mutations in KRAS were reported in a subset of sotorasib-treated KRAS-G12C positive patients (Zhao et al. 2021). Thus, this study aims to determine the inhibitor sensitivity profiles of non-G12C mutants of KRAS against both clinically approved and experimental RAS inhibitors using molecular docking analysis to identify their utility in treating non-G12C KRAS-mutated cancers.

Methods

A total of ten covalent inhibitors that bind to switch-II-pocket of KRAS were selected to perform molecular docking on wildtype (WT) and eleven KRAS mutants. The PDB 6OIM (Canon et al. 2019) was taken as a template to create wildtype (WT) and mutant KRAS structures with SWISS-MODEL software (Waterhouse et al. 2018). Energy minimization of the wildtype (WT) and mutant KRAS structures was carried out using Swiss-PdbViewer (Guex et al. 2009). The minimized structures were then loading onto the AutoDock 4.2.6 (Morris et al. 2009) to remove water molecules, add hydrogen bonds and gasteiger charges and save as pdbqt files. Covalent RAS inhibitors were extracted from PDBs (6OIM: sotorasib; 6UT0: adagrasib; 6B0V: ARS107; 5F2E: ARS853; 6B0Y: ARS917; 5V9U: ARS1620; 5V9L: 1_AM; 6P8Z: Indole lead 1Amgen; 6N2J: 4Fell; 4LYH: 9OStrem) and then converted to mol2 format using Mercury software. The mol2 files of ligands were then loaded onto AutoDock 4.2.6, and the number of torsions was set to fewest atoms and saved as pdbqt files. The active site residues were taken from the ligand interactions of all the ten covalent inhibitors from co-crystal structures (6OIM, 6UT0, 6B0V, 5F2E, 6B0Y, 5V9U, 5V9L, 6P8Z, 6N2J and 4LYH), and the average of XYZ-coordinates of the active site residues was calculated to obtain the centroid. Each protein pdbqt file was loaded onto Autodock 4.2.6, and the calculated centroid was given to create a grid box and then the file was saved as grid parameter file (.gpf) to run AutoGrid. A set of map files were generated after running AutoGrid. The pdbqt files of both protein and ligand were loaded and the docking parameter file (.dpf) was generated by using genetic algorithm (GA) as a search parameter, and the number of GA runs was set to “50” and number of evaluations to “long” (i.e. 2,50,00,000 times). Molecular docking was carried out by running AutoDock, and the binding energies (kcal/mol) from the best pose for each protein–ligand interaction were collected and analysed.

MDS was performed on the complexes of G12C/A/S mutants with adagrasib and sotorasib using GROMACS v.2020 (GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulation) (Pronk et al. 2013). The ligand-bound complexes were simulated for 100 ns, and the topology of ligand-bound structures was generated with the GROMOS96 43a1 force field. The charge group concept is used by the GROMOS 43a1 force field. The well-balanced GROMOS96 force-field parameter set 43A1 yields excellent results for a wide range of biomolecules (Schuler et al. 2001). The system was solvated in a cubic periodic boundary box of 10.0 × 10.0 × 10.0 nm3, with SPC (single point charge) water models ranging from 6000 to 30,000 depending upon the complexes. The parameters and topology files for the sotorasib and adagrasib atoms were generated by the PRODRG server (Schüttelkopf and van Aalten 2004). Appropriate counter ions (Na+ or Cl−) were added by replacing the water molecules to neutralize the system having a net charge. System energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm to remove the weak van der Waals contacts and optimize the bond lengths, bond angles and torsion angles (Bhardwaj et al. 2020). Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method was applied to study electrostatic interactions. van der Waals interactions were truncated at a default cut-off of 0.9 nm. NPT (number of particles, pressure and temperature) and NVT (number of particles, volume and temperature) canonical ensemble calculations were performed. These were carried out for 50,000 steps. The systems were heated to 300 K using Berendsen thermostat, and for full anisotropic simulations, the Parrinello-Rahman barostat was used with a coupling time of 0.1 ps, and a pressure of 1 bar was maintained during the step. Final MD simulations of 50,000,000 steps (100,000 ps), i.e. 100 ns, were carried out, and results were generated using the embedded packages of GROMACS. Xmgrace was used to visualize the RMSD and RMSF for the protein backbone and side chains.

Results and discussion

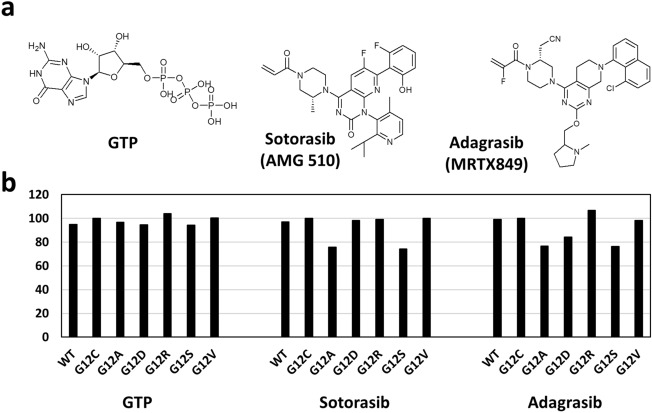

A total of 132 dockings were performed on wildtype (WT) and eleven KRAS mutants with eleven ligands that include GTP, sotorasib, adagrasib and eight RAS inhibitors that are in various stages of clinical trials. Initially, comparative molecular docking analysis was performed on WT and six KRAS-G12X (G12C/A/D/R/S/V) mutants with GTP, sotorasib and adagrasib. The KRAS-G12C mutant displayed higher binding affinity and sensitivity towards GTP, sotorasib and adagrasib when compared to WT (Fig. 1, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 1–3). This observation is in conformity with clinical data, wherein 80.6% of KRAS-G12C positive NSCLC patients (n = 126) displayed disease control with sotorasib (objective response rate: 37.1% and median overall survival: 12.5 months) (Skoulidis et al. 2021), thus validating the utility of molecular docking analysis in predicting drug sensitivity. Among KRAS-non-G12C mutants, KRAS-G12R (BE: – 8.46 kcal/mol) displayed higher binding affinity than both WT (BE: – 7.72 kcal/mol) and KRAS-G12C mutant (BE: – 8.13 kcal/mol) towards GTP. Mutations KRAS-G12D (BE: – 7.68 kcal/mol), KRAS-G12S (BE: – 7.67 kcal/mol) and KRAS-G12A (BE: – 7.87 kcal/mol) displayed binding affinities similar to WT (BE: – 7.72 kcal/mol) towards GTP, while KRAS-G12V (BE: – 8.17 kcal/mol) showed binding affinity comparable to that of KRAS-G12C mutant (Fig. 1, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 1–3).

Fig. 1.

Binding affinities of wildtype and KRAS-G12X mutants towards GTP, sotorasib and adagrasib. a Chemical structures of GTP and clinically approved covalent inhibitors (sotorasib and adagrasib) of KRAS b Drug binding affinities shown in terms of percentage binding affinity as compared to G12C (100%) as reference

Table 1.

Predicted drug sensitivity profiles of wildtype, KRAS-G12X and KRAS-non-G12X mutants towards clinically approved as well as experimental therapeutics

| WT | G12C | G12A | G12D | G12R | G12S | G12V | G13D | Q61H | H95L | H95Q | Y96D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTP | – 7.72 | – 8.13 | – 7.87 | – 7.68 | – 8.46 | – 7.67 | – 8.17 | – 7.12 | – 7.74 | – 7.67 | – 7.78 | – 7.4 |

| Sotorasib | – 8.69 | – 8.96 | – 6.79 | – 8.81 | – 8.87 | – 6.66 | – 8.96 | – 8.66 | – 8.39 | – 8.79 | – 8.68 | – 8.47 |

| Adagrasib | – 9.51 | – 9.58 | – 7.34 | – 8.07 | – 10.23 | – 7.31 | – 9.4 | – 9.7 | – 7.2 | – 9.36 | – 9.49 | – 7.68 |

| ARS– 107 | – 8.09 | – 8.35 | – 7.11 | – 7.8 | – 8.35 | – 7.13 | – 8.26 | – 8.06 | – 7.13 | – 8.1 | – 8.07 | – 7.89 |

| ARS– 853 | – 7.85 | – 8.06 | – 7.2 | – 7.99 | – 8.11 | – 7.55 | – 7.91 | – 7.65 | – 7.59 | – 7.93 | – 7.75 | – 7.92 |

| ARS– 917 | – 8.26 | – 8.35 | – 6.81 | – 8.33 | – 8.3 | – 6.88 | – 8.21 | – 8.01 | – 6.6 | – 8.26 | – 8.2 | – 8.12 |

| ARS– 1620 | – 8.31 | – 8.45 | – 7.35 | – 8.39 | – 8.38 | – 7.33 | – 8.37 | – 8.28 | – 6.6 | – 8.31 | – 8.27 | – 7.7 |

| 1_AM | – 8.37 | – 8.46 | – 7.53 | – 8.54 | – 8.41 | – 7.42 | – 8.61 | – 8.36 | – 7.63 | – 8.43 | – 8.51 | – 7.81 |

| Indole lead 1Amgen | – 8.22 | – 8.36 | – 8.38 | – 8.32 | – 8.37 | – 8.39 | – 8.52 | – 8.13 | – 8.39 | – 8.21 | – 8.2 | – 7.48 |

| 4Fell | – 8.79 | – 8.91 | – 7.01 | – 8.81 | – 8.77 | – 6.91 | – 8.78 | – 8.51 | – 6.22 | – 8.79 | – 8.69 | – 8.03 |

| 9OStrem | – 6.86 | – 6.82 | – 6.29 | – 6.93 | – 6.89 | – 6.31 | – 7.06 | – 6.9 | – 6.41 | – 6.88 | – 6.84 | – 6.76 |

Binding energies (kcal/mol) of KRAS wildtype and mutants towards targeted KRAS inhibitors were shown

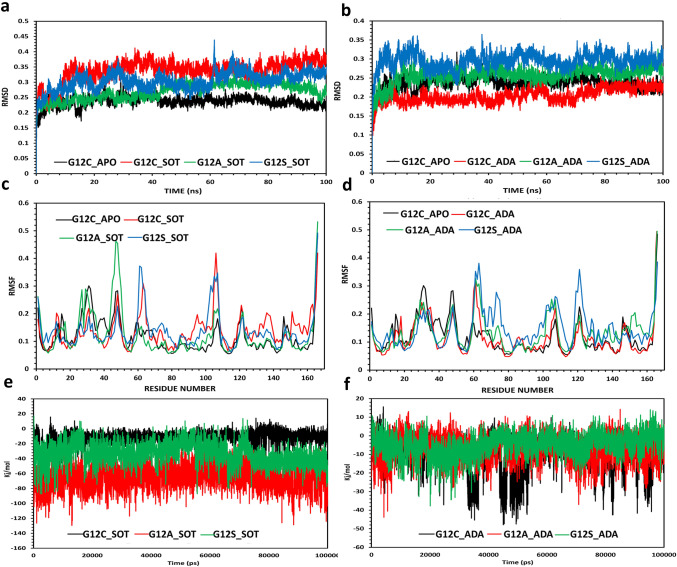

When compared to WT (BE-Sotorasib: – 8.69 kcal/mol; BE-Adagrasib: – 9.51 kcal/mol) and KRAS-G12C mutant (BE-Sotorasib: – 8.96 kcal/mol; BE-Adagrasib: – 9.58 kcal/mol), both KRAS-G12A and KRAS-G12S displayed very high resistance towards sotorasib (BE-G12A: – 6.79 kcal/mol; BE-G12S: – 6.66 kcal/mol) as well as adagrasib (BE-G12A: – 7.34 kcal/mol; BE-G12S: – 7.31 kcal/mol). KRAS-G12V (BE: – 9.4 kcal/mol) and KRAS-G12D (BE: – 8.07 kcal/mol) showed moderate to high resistance towards adagrasib when compared to WT (BE: – 9.51 kcal/mol); interestingly, KRAS-G12R mutant (BE: – 10.23 kcal/mol) displayed higher sensitivity than the KRAS-G12C mutant (BE: – 9.58 kcal/mol) towards adagrasib (Fig. 1, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 1–3). Notably, KRAS-G12D (BE: – 8.81 kcal/mol), KRAS-G12R (BE: – 8.87 kcal/mol) and KRAS-G12V (BE: – 8.96 kcal/mol) mutants showed comparable affinity towards sotorasib with intermediate binding affinities as compared to WT and the KRAS-G12C mutant (Fig. 1, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 1–3). These results thus highlight the heterogeneity in drug sensitivity among the G12X mutations. Molecular dynamic simulations for resistant mutations G12A and G12S revealed that the mutant complexes with sotorasib and adagrasib were stable and differed little from the G12C mutant (Fig. 2a, b). Interestingly, adagrasib induced slightly more changes than the sotorasib in the effector lobe of G12A/S mutants that include both switch I (E31 to D38) and switch II (G60 to E76) regions (Fig. 2c, d). Further mechanistic analysis of KRAS-G12X mutants with sotorasib revealed that the mutants G12D, G12R and G12V displayed similar number of protein–ligand interactions when compared to that of KRAS-G12C, whereas the resistant mutants G12A and G12S showed less number of protein–ligand interactions (Suppl. Fig. no. 2, 3). Specifically, interactions of sotorasib with V9, G60, M72 and D92 residues of G12C mutant were absent in G12A and G12S mutants possibly resulting in reduced binding affinity (Suppl. Fig. no. 2, 3). Similarly, interaction of adagrasib with I100 of G12C were absent in G12A/S mutants (Suppl. Fig. no. 2, 3). These results combined with MD simulations suggest that the slight changes in the inhibitor binding pocket of resistant mutants resulting in reduced number of interactions with key residues lead to resistance of G12A/S mutants. Furthermore, the number of interactions of G12D with sotorasib are similar to that of the G12C mutant, while the number of interactions were significantly reduced for G12D (missing interactions: G60, R68, D92 and H95) with adagrasib as compared to the G12C mutant (Suppl. Fig. no. 2, 3) conforming to sotorasib sensitivity but adagrasib resistance of G12D mutant (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Molecular Dynamic simulations of G12S and G12A mutants. RMSD plots for backbone cα atoms relative to their initial minimized complex structure as a function of time a G12C/A/S mutants in complex with sotorasib b G12C/A/S mutants in complex with adagrasib. RMSF plot for cα atoms relative to their initial minimized complex structure as a function of the amino acid residues in the structure: c G12C/A/S mutant-sotorasib complexes d G12C/A/S mutant-adagrasib complexes. Interaction energies of KRAS mutants G12C/A/S were depicted towards sotorasib e and adagrasib f

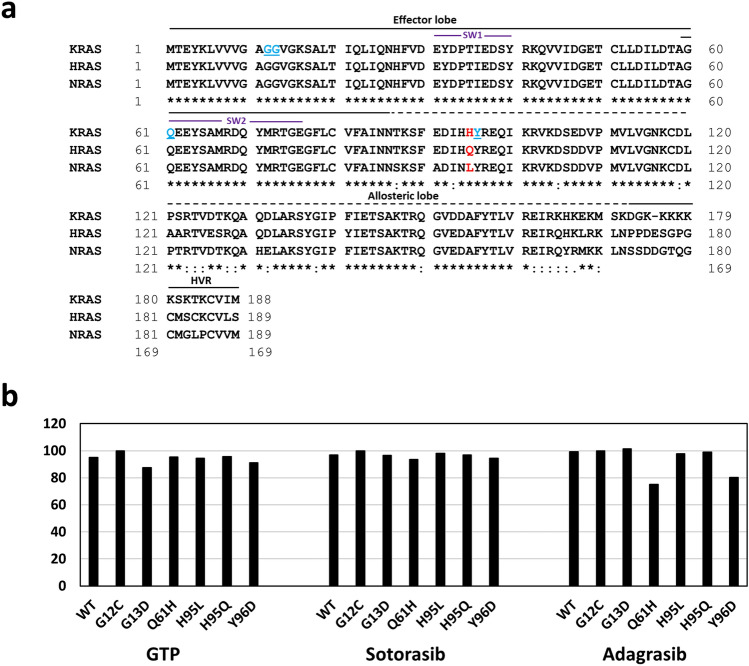

Further, molecular docking analysis was carried out on five additional KRAS non-G12C mutants G13D, Q61H, H95L/Q and Y96D. While G13D and Q61H are frequent non-G12C mutations, H95L/Q was selected because H95 was shown to interact with sotorasib (Canon et al. 2019) and adagrasib (Fell et al. 2020). Moreover, H95 is not conserved among RAS isoforms (Fig. 3a); therefore, we chose H95L/Q substitutions that are specific to NRAS and HRAS, respectively (Fig. 3a). The KRAS-Y96D mutant was selected because it was reported to emerge during secondary drug resistance following the treatment with adagrasib (Tanaka et al. 2021). KRAS-G13D (BE: – 7.12 kcal/mol) and KRAS-Y96D (BE: – 7.4 kcal/mol) showed lower binding affinity, while KRAS-Q61H (BE: – 7.74 kcal/mol), KRAS-H95L (BE: – 7.67 kcal/mol) and KRAS-H95Q (BE: – 7.78 kcal/mol) displayed similar binding affinities towards GTP when compared to WT (BE: – 7.72 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3b, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 1–3). When tested for sotorasib, KRAS-Q61H (BE: -8.39 kcal/mol) and KRAS-Y96D (BE: – 8.47 kcal/mol) displayed moderate resistance, whereas mutants KRAS-G13D (BE: – 8.66 kcal/mol), KRAS-H95L (BE: -8.79 kcal/mol) and KRAS-H95Q (BE: – 8.68 kcal/mol) exhibited binding affinities similar to that of the WT (BE: – 8.69 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3b, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 1–3). Interestingly, KRAS-non-G12X mutants showed variable sensitivities towards adagrasib when compared to WT (BE: – 9.51 kcal/mol) and KRAS-G12C mutant (BE: – 9.58 kcal/mol): KRAS-Q61H (BE: – 7.2 kcal/mol) and KRAS-Y96D (BE: – 7.68 kcal/mol) exhibited high resistance, KRAS-H95L (BE: – 9.36 kcal/mol) displayed moderate resistance, KRAS-H95Q (BE: – 9.49 kcal/mol) showed similar affinity to that of the WT, and KRAS-G13D (BE: – 9.7 kcal/mol) displayed slightly higher sensitivity. MD simulation analysis revealed that there are no significant changes in protein stability in both the resistant mutants Q61H and Y96D (Suppl. Fig. no. 12). Further analysis of ligand-mutant complex revealed reduced number of interactions of sotorasib (missing interactions: K16, D92 and H95) and adagrasib (missing interactions: G60, Q61, E63, D92 and I100) with Y96D mutant as compared to the G12 mutant (Suppl. Fig. no. 2, 3). These observations largely corroborated with available experimental data from recent reports: (a) KRAS-G13D showed lower binding energies towards sotorasib and adagrasib than that of the KRAS-G12R mutant in this study, which is in line with pre-clinical observations using Ba/F3 cell lines (Awad et al. 2021) and (b) KRAS-Y96D displayed moderate to high resistance towards sotorasib and adagrasib in this study, which corroborated with both clinical and experimental data (Tanaka et al. 2021; Koga et al. 2021). Our results indicate the possibility of resistance of several KRAS-non-G12C mutants towards sotorasib and adagrasib as revealed by binding affinity analyses, which also corroborated with available limited clinical and experimental data.

Fig. 3.

Binding affinities of KRAS-non-G12X mutants towards GTP, sotorasib and adagrasib. a Multiple sequence alignment of RAS isoforms; KRAS mutants taken in the study are highlighted in blue and red. b Drug binding affinities measured in terms of percentage binding affinity as compared to G12C (100%) mutant. SW1: Switch-I region, SW2: Switch-II region, HVR: Hypervariable region

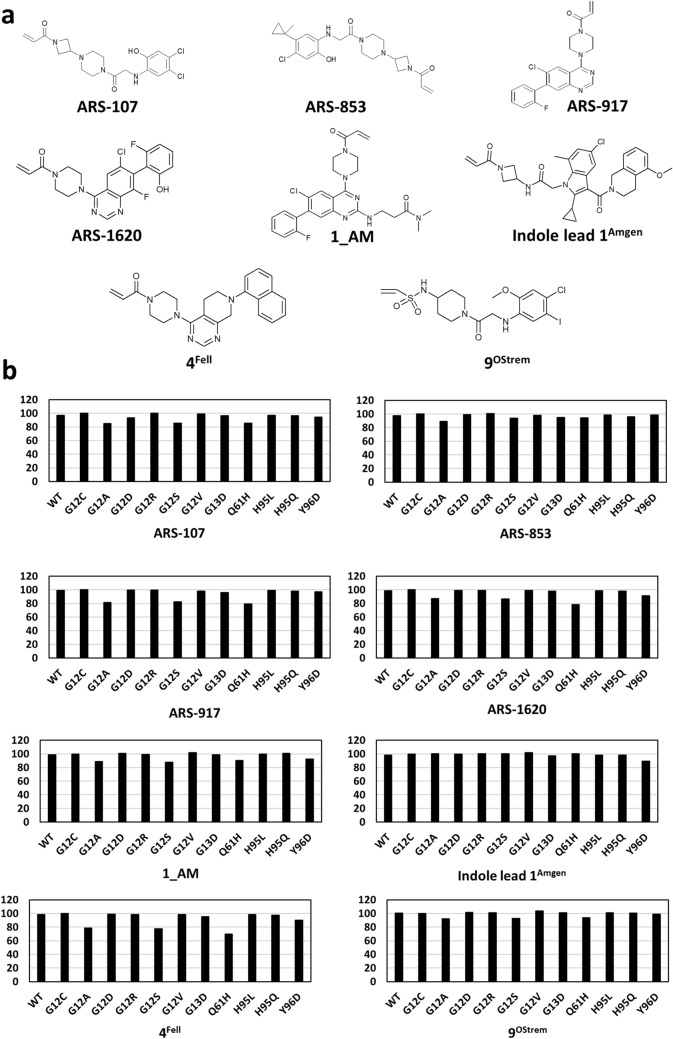

While sotorasib and adagrasib are approved for treating RAS-G12C cancers, emerging reports (Awad et al. 2021; Koga et al. 2021) of acquired resistance to these inhibitors posed significant clinical challenge. There is thus an urgent need to develop new KRAS-specific inhibitors as well as to test available experimental inhibitors. Therefore, we performed molecular docking analysis to test the efficacy of eight additional inhibitors towards all the ten non-G12C KRAS mutants. Mutants KRAS-G12A, KRAS-G12S and KRAS-Q61H displayed moderate to high resistance towards all inhibitors except for Indole lead 1Amgen when compared to WT and KRAS-G12C mutant (Fig. 4, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 4–11). KRAS-G12D showed affinities similar to that of KRAS-G12C mutant towards all inhibitors but displayed moderate resistance towards ARS-107 (Fig. 4, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 4–11). Importantly, KRAS-G12R, KRAS-G12V and KRAS-H95L/Q mutants displayed sensitivities similar to that of the KRAS-G12C mutant towards all the eight inhibitors (Fig. 4, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 4–11). KRAS-G13D showed high resistance towards ARS-853, ARS-917 and 4Fell when compared to KRAS-G12C and exhibited affinities similar to that of the WT and KRAS-G12C towards remaining five inhibitors (Fig. 4, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 4–11). KRAS-Y96D displayed moderate to high resistance towards all inhibitors except for ARS-853 and 9OStrem (Fig. 4, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. no. 4–11). KRAS-Y96D was recently reported to cause resistance to ARS-1620 in vitro (Tanaka et al. 2021); our analysis also showed that this mutant (Table 1) exhibited high resistance towards ARS-1620 further confirming with the experimental data. These results revealed differential binding affinities of various RAS inhibitors towards KRAS-non-G12C mutants thus indicating the possibility of mutation-dependent primary resistance towards RAS inhibitor treatment.

Fig. 4.

Binding affinities of KRAS-non-G12C mutants towards eight additional inhibitors a Chemical structures of RAS inhibitors b Drug sensitivity profiles of KRAS-G12X and KRAS-non-G12X mutants towards eight experimental RAS inhibitors

In conclusion, the current study established predicted sensitivity profiles towards both clinically approved sotorasib and adagrasib as well as experimental RAS inhibitors for KRAS-non-G12C mutants. Importantly, KRAS -G12A and KRAS-G12S were resistant to sotorasib and adagrasib due to altered binding pocket resulting in the reduced number of crucial mutant-inhibitor interactions. Among non-G12X mutations, KRAS-Y96D is resistant to sotorasib and adagrasib due to reduced number of interactions as compared to that of the KRAS-G12C mutant, which is in line with the previously reported pre-clinical and clinical data. These data help to predict the response of a specific KRAS-non-G12C mutant cancer towards inhibitor treatment. This is especially important in the context that the experimental data for KRAS-non-G12C mutants are scant. However, the conformity of molecular docking results with the available limited experimental data suggests the utility of computational drug sensitivity profiles in predicting clinical response in KRAS-non-G12C-mutated cancers. Furthermore, the observation that some mutants still remain resistant to available drugs suggests the possibility of emergence of these mutants to cause secondary drug resistance in KRAS-G12C-mutated cancers. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel inhibitors that specifically target resistant mutations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

RKK acknowledges funding from ICMR-Ad-hoc grant (F.No. 58/31/2020/PHA/BMS) and DST-PURSE grant (C-DST-PURSE-II/102/2020). BVLS gratefully acknowledges the Indian Government funding agencies, DST-SERB-CRG, ICMR-ISRM and DST-NSM for their resource support through the project grants. BVLS acknowledges PARAM Yukti Facility under the National Supercomputing Mission (NSM), Government of India, at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR), Bangalore. SA acknowledges fellowship (Senior Research Fellowship: 2019-6060/CMS-BMS) from ICMR, India. SCM acknowledges research assistant fellowship (F.No. 58/31/2020/PHA/BMS) from ICMR, India. PSS acknowledges DST-NSM for the fellowship.

Author contributions

SCM, PSS, VRA, RS and VM performed the work. SA, BVLS and RKK designed the work, contributed the expertise and analysed the data. SCM, PSS, VRA, BVLS and RKK wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors agree that they will make freely available any of the organisms, viruses, cells, nucleic acids, antibodies, reagents, data and associated protocols that were used in the reported research that are not available commercially, to colleagues for academic research without preconditions.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

SCM, SA, PSS, VRA, RS, VM, BVLS and RKK declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Not applicable.

Research involving human and animal rights

The research does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Footnotes

Sai Charitha Mullaguri and Sravani Akula have equally first author contribution.

References

- Awad MM, Liu S, Rybkin II, Arbour KC, Dilly J, Zhu VW, Johnson ML, Heist RS, Patil T, Riely GJ, Jacobson JO, Yang X, Persky NS, Root DE, Lowder KE, Feng H, Zhang SS, Haigis KM, Hung YP, Sholl LM, Wolpin BM, Wiese J, Christiansen J, Lee J, Schrock AB, Lim LP, Garg K, Li M, Engstrom LD, Waters L, Lawson JD, Olson P, Lito P, Ou SI, Christensen JG, Jänne PA, Aguirre AJ. Acquired resistance to KRASG12C inhibition in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2382–2393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj VK, Singh R, Sharma J, Das P, Purohit R. Structural based study to identify new potential inhibitors for dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;194:105494. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke K, Bagal D, Gaida K, Holt T, Knutson CG, Koppada N, Lanman BA, Werner J, Rapaport AS, San Miguel T, Ortiz R, Osgood T, Sun JR, Zhu X, McCarter JD, Volak LP, Houk BE, Fakih MG, O'Neil BH, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Desai J, Kuo J, Govindan R, Hong DS, Ouyang W, Henary H, Arvedson T, Cee VJ, Lipford JR. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575:217–223. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell JB, Fischer JP, Baer BR, Blake JF, Bouhana K, Briere DM, Brown KD, Burgess LE, Burns AC, Burkard MR, Chiang H, Chicarelli MJ, Cook AW, Gaudino JJ, Hallin J, Hanson L, Hartley DP, Hicken EJ, Hingorani GP, Hinklin RJ, Mejia MJ, Olson P, Otten JN, Rhodes SP, Rodriguez ME, Savechenkov P, Smith DJ, Sudhakar N, Sullivan FX, Tang TP, Vigers GP, Wollenberg L, Christensen JG, Marx MA. Identification of the clinical development candidate MRTX849, a Covalent KRASG12C inhibitor for the treatment of cancer. J Med Chem. 2020;63:6679–6693. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: A historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:S162–S173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CW, Jeong MS, Jang SB. Structure, signaling and the drug discovery of the Ras oncogene protein. BMB Rep. 2017;50:355–360. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.7.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs GA, Der CJ, Rossman KL. RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:1287–1292. doi: 10.1242/jcs.182873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T, Suda K, Fujino T, Ohara S, Hamada A, Nishino M, Chiba M, Shimoji M, Takemoto T, Arita T, Gmachl M, Hofmann MH, Soh J, Mitsudomi T. KRAS secondary mutations that confer acquired resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitors, sotorasib and adagrasib, and overcoming strategies: insights from in vitro experiments. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:1321–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick F. Sticking it to KRAS: covalent inhibitors enter the clinic. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AR, Rosenberg SC, McCormick F, Malek S. RAS-targeted therapies: is the undruggable drugged? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:533–552. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaka M, Li Y, Sukari A, Ou SI, Al-Hallak MN, Azmi AS. KRAS G12C Game of Thrones, which direct KRAS inhibitor will claim the iron throne? Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;84:101974. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.101974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bryan JP. Pharmacological targeting of RAS: Recent success with direct inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2019;139:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk S, Páll S, Schulz R, Larsson P, Bjelkmar P, Apostolov R, Shirts MR, Smith JC, Kasson PM, van der Spoel D, Hess B, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler LD, Daura X, Van Gunsteren WF. An improved GROMOS96 force field for aliphatic hydrocarbons in the condensed phase. J Comput Chem. 2001;22:1205–1218. doi: 10.1002/jcc.1078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schüttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, Italiano A, Schuler M, Borghaei H, Barlesi F, Kato T, Curioni-Fontecedro A, Sacher A, Spira A, Ramalingam SS, Takahashi T, Besse B, Anderson A, Ang A, Tran Q, Mather O, Henary H, Ngarmchamnanrith G, Friberg G, Velcheti V, Govindan R. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p. G12C Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2371–2381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Lin JJ, Li C, Ryan MB, Zhang J, Kiedrowski LA, Michel AG, Syed MU, Fella KA, Sakhi M, Baiev I, Juric D, Gainor JF, Klempner SJ, Lennerz JK, Siravegna G, Bar-Peled L, Hata AN, Heist RS, Corcoran RB. Clinical Acquired Resistance to KRASG12C Inhibition through a Novel KRAS Switch-II Pocket Mutation and Polyclonal Alterations Converging on RAS–MAPK Reactivation. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1913–1922. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-21-0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, Heer FT, de Beer TAP, Rempfer C, Bordoli L, Lepore R, Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Murciano-Goroff YR, Xue JY, Ang A, Lucas J, Mai TT, Da Cruz Paula AF, Saiki AY, Mohn D, Achanta P, Sisk AE, Arora KS, Roy RS, Kim D, Li C, Lim LP, Li M, Bahr A, Loomis BR, de Stanchina E, Reis-Filho JS, Weigelt B, Berger M, Riely G, Arbour KC, Lipford JR, Li BT, Lito P. Diverse alterations associated with resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature. 2021;599:679–683. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04065-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors agree that they will make freely available any of the organisms, viruses, cells, nucleic acids, antibodies, reagents, data and associated protocols that were used in the reported research that are not available commercially, to colleagues for academic research without preconditions.