Abstract

MicroRNA miR-29 promotes endothelial function in human arterioles in part by targeting LYPLA1 and increasing nitric oxide production. In addition, miR-29 is a master inhibitor of extracellular matrix gene expression, which may attenuate fibrosis but could also weaken tissue structure. The goal of this study was to test whether miR-29 could be developed as an effective, broad-acting, and safe therapeutic. Substantial accumulation of miR-29b and effective knockdown of Lypla1 in several mouse tissues were achieved using a chitosan-packaged, chemically modified miR-29b mimic (miR-29b-CH-NP) injected systemically at 200 μg/kg body weight. miR-29b-CH-NP, injected once every 3 days, significantly attenuated angiotensin II-induced hypertension. In db/db mice, miR-29b-CH-NP treatment for 12 weeks decreased cardiac and renal fibrosis and urinary albuminuria. In uninephrectomized db/db mice, miR-29b-CH-NP treatment for 20 weeks significantly improved myocardial performance index and attenuated proteinuria. miR-29b-CH-NP did not worsen abdominal aortic aneurysm in ApoE knockout mice treated with angiotensin II. miR-29b-CH-NP caused aortic root fibrotic cap thinning in ApoE knockout mice fed a high-cholesterol and high-fat diet but did not worsen the necrotic zone or mortality. In conclusion, systemic delivery of low-dose miR-29b-CH-NP is an effective therapeutic for several forms of cardiovascular and renal disease in mice.

Keywords: microRNA, fibrosis, therapeutics, hypertension, heart, kidney, diabetic complications, aneurysm, atherosclerosis, albuminuria

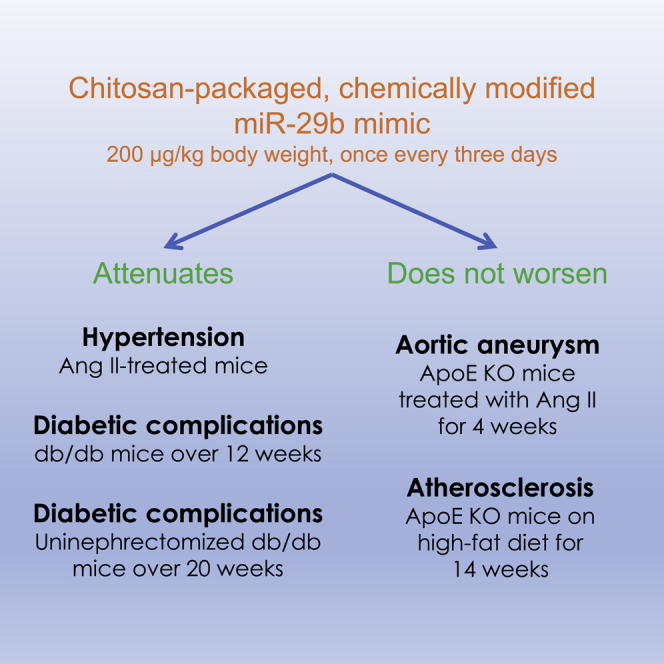

Graphical abstract

Liang and colleagues developed a chitosan-packaged, chemically modified miR-29b mimic (miR-29b-CH-NP). Using five models of disease, they demonstrated that systemic delivery of low-dose miR-29b-CH-NP was an effective, broad-acting, and safe therapeutic for several forms of cardiovascular and renal disease in mice.

Introduction

Cardiovascular and renal diseases, including hypertension and diabetic complications, are among leading causes of death and disease burden worldwide.1,2 Endothelial dysfunction is a common finding in cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and diabetic microvascular complications, and may mechanistically contribute to the development of these diseases.3 Tissue fibrosis is a common pathological feature of these diseases and is associated with adverse disease outcomes. Therapeutics that target endothelial dysfunction and tissue fibrosis simultaneously could have broad relevance and utilities in the treatment of cardiovascular and renal diseases.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, endogenous, non-coding RNAs that mainly function to limit the protein expression of their target genes. miRNAs are attractive therapeutic agents because they may regulate networks of gene targets and multiple pathways that can converge to affect a phenotype or disease.4,5,6,7 A classic example of this is the miR-29 family that includes miR-29a, -29b, and -29c.8

The mechanisms by which miR-29 influences extracellular matrix (ECM) and endothelial function are well-established. We and others have shown that miR-29 directly targets and suppresses at least 16 ECM genes.8 We recently established that miR-29 is critical for endothelial function in humans and rodents as it inhibits its direct target Lypla1 (lysophospholipase 1), a gene that would otherwise decrease nitric oxide (NO) production.9 Consistent with the broad targeting of ECM genes, miR-29 has been shown to be anti-fibrotic in a number of organs including the heart,10 lungs,11 kidneys,12,13 and liver.14 However, inhibition of miR-29 has been reported to lead to less serious formation of atherosclerotic plaques and aneurysm in multiple mouse models, possibly in part because miR-29 may weaken normal or protective ECM structures under these disease conditions.15,16,17

Given these reports, a critical question for the field is whether miR-29 can be developed and delivered as an effective, broad-acting, and safe therapeutic for cardiovascular and renal diseases in vivo. An miR-29b-3p (miR-29b) mimic has been used to treat fibrosis in mouse lungs but the mimic was delivered at a high dose (100 mg/kg body weight).11 Successful delivery of mimics of other miRNA at lower doses (0.2 mg/kg body weight) using chitosan nanoparticles has been reported.18,19

The goal of this study was to test a custom formulation of miR-29 as a broad-acting therapeutic based on known mechanisms of action for miR-29. We developed a chitosan-packaged, chemically modified miR-29b mimic and tested its effect on established mouse models of hypertension, diabetic cardiomyopathy, nephropathy and retinopathy, atherosclerosis, and aortic aneurysm.

Results

miR-29b mimic with custom modifications retains the ability to improve EDVD

We have previously shown that liposome packaged, commercially available miR-29 pre-miRNA mimics improved EDVD in isolated ex vivo arterioles from humans with diabetes and hypertension.9 In this study, we modified a previous design of miR-29b for intravenous injection.11 2′-O-methyl groups were added to some nucleotides on the minor strand to increase stability and to prevent loading into the RNA-induced silencing complex. 2′-F groups were added to some nucleotides on the major strand to protect against exonucleases and increase stability. Mismatches were included on the minor strand to prevent the exogenous minor strand from acting as an anti-miR to endogenous miR-29b-3p. We omitted the conjugated cholesterol on the 3′ end of the minor strand because we planned to use nanoparticle packaging for in vivo administration. We also designed a scramble miRNA mimic containing the same chemical modifications and synthesized both mimics at Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

We determined if our customized miR-29b mimic retains the ability to improve EDVD by transfecting arterioles from SS and SS.13BN rats. SS rats are a widely studied model of endothelial dysfunction,20,21 and SS.13BN rats are frequently used as normal controls for SS.22,23 Arterioles from SS exhibit diminished EDVD that is exacerbated with a 4.0% NaCl diet. Intraluminal transfection of isolated arterioles with the customized miR-29b mimic packaged in Lipofectamine 2000 (35 nM final concentration) restored EDVD to levels comparable to control SS.13BN arterioles at the highest dose of acetylcholine (Ach) (Figure S1A). Vasodilation in these vessels is primarily driven by NO; NO bioavailability in SS arterioles as measured by DAF2-DA fluorescence was also improved with miR-29b transfection to levels seen in SS.13BN arterioles (Figure S1B). These data indicate that the chemically modified miR-29b mimic retains the physiological effect of native miR-29b.

Effective delivery of chitosan-packaged miR-29b mimic in vivo

In our previous studies, delivery of miR-29 pre-miRNA mimics to cultured human dermal endothelial cells (HMVEC-d) was performed at a final concentration of 35 nM using Lipofectamine 2000.9 For a biocompatible system for in vivo delivery, we packaged our customized scramble mimic and miR-29b mimic into chitosan nanoparticles (denoted Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP). Following transfection of Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP, expression of two known targets of miR-29b, LYPLA1 and COL3A1 (collagen type III alpha 1 chain), in HMVEC-d was significantly downregulated by miR-29b-CH-NP (Figure S2). COL3A1 in particular was significantly downregulated at a low concentration of miR-29b (5 nM) using chitosan nanoparticles (Figure S2). Transfection with chitosan-packaged mimics resulted in observably fewer floating cells than transfections carried out with Lipofectamine 2000.

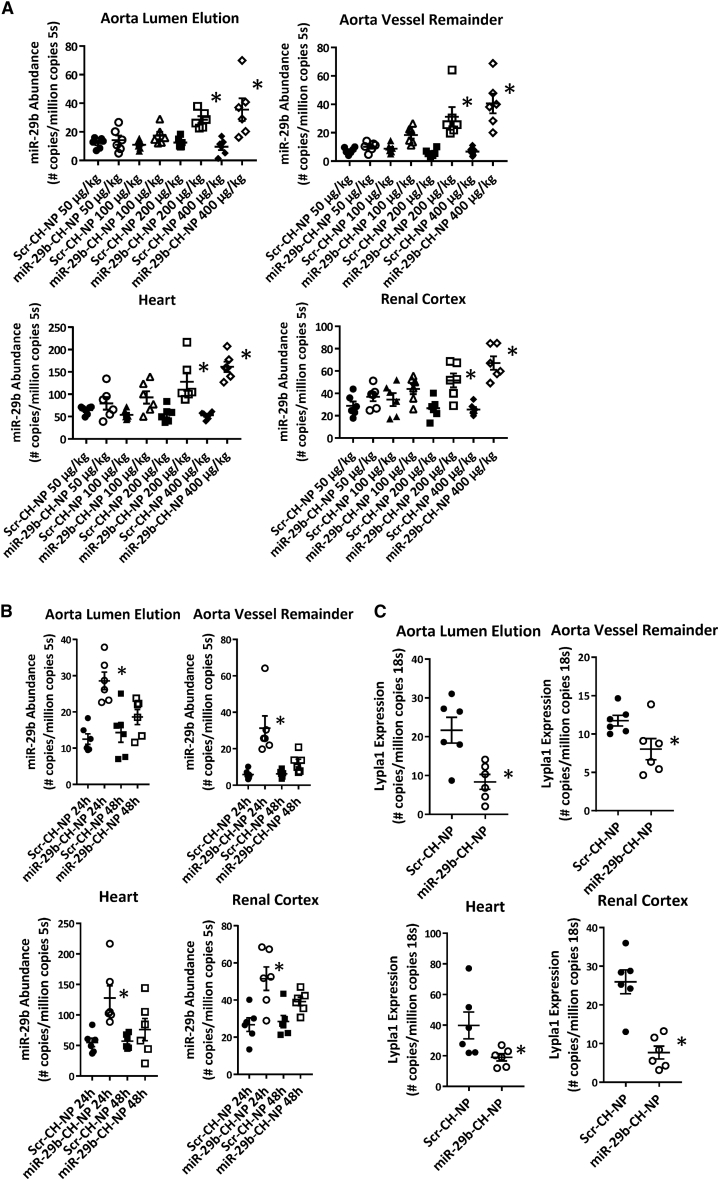

We next determined the in vivo distribution and effectiveness of chitosan-packaged miR-29b delivery. Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected via retro-orbital injection at doses of 50 μg/kg, 100 μg/kg, 200 μg/kg, or 400 μg/kg body weight in C57BL/6J mice. Tissues were collected 24 h later. Doses at or above 200 μg/kg were sufficient to significantly increase miR-29b abundance as measured by real-time RT-PCR in multiple organs of interest to this study: the aorta, the heart, and the kidney (Figure 1A). The increase of miR-29b abundance in the aorta occurred in both the endothelium-enriched fraction and the vessel remainder. Injection of Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP at 200 μg/kg was carried out in additional C57 mice and tissues were collected 48 h post-injection. Although it did not reach statistical significance, mice receiving the miR-29b-CH-NP injection continued to show a trend of greater miR-29b abundance at 48 h (Figure 1B). Lypla1 is a direct target of miR-29 that impacts NO bioavailability.9 Using miR-29b-CH-NP, we were able to decrease Lypla1 mRNA abundance in all tissues examined (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Chitosan packaging allows for robust in vivo delivery of miR-29b mimic with broad tissue distribution

(A) Real-time RT-PCR detection of miR-29b in multiple tissues (aorta lumen elution, aorta vessel remainder, heart, and renal cortex) showed significant increases in miR-29b abundance above a dose of 200 μg/kg body weight at 24 h after the injection. ∗p ≤ 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP at the same dose, Student’s t test. (B) Real-time RT-PCR detection of miR-29b showed increases in miR-29b abundance tended to persist for 24–48 h post-injection in multiple tissues. Mice were injected retro-orbitally at a dose of 200 μg/kg body weight. ∗p ≤ 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP 24 h, 1-way ANOVA. (C) Real-time RT-PCR detection of Lypla1 in multiple tissues collected 24 h post-injection of miR-CH at 200 μg/kg body weight. ∗p ≤ 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, Student’s t test. n = 6 in all experiments. Data are mean ± SEM.

miR-29b-CH-NP attenuates angiotensin II-induced hypertension

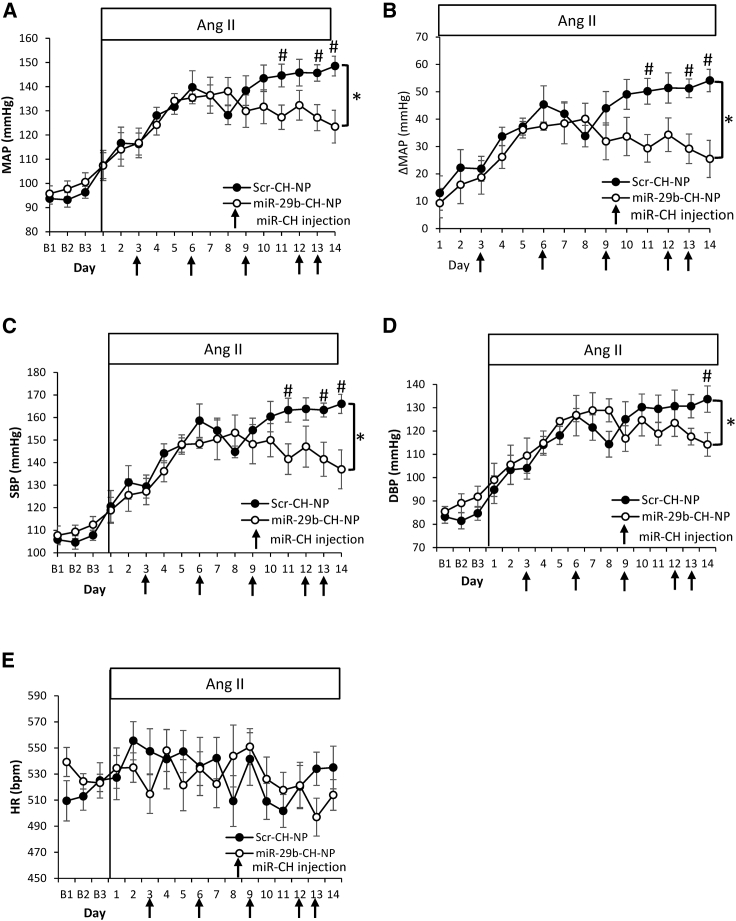

We have previously demonstrated that global knockdown of miR-29a and -29b in rats results in increased blood pressure, which is mediated in part by increasing Lypla1 expression and, in turn, decreasing NO bioavailability.9 We examined whether miR-29b-CH-NP would have therapeutic effects on hypertension. Blood pressure of conscious, freely moving C57 mice was monitored using radio telemetry. After baseline blood pressure recording, an osmotic minipump was implanted to deliver angiotensin II (Ang II) at a rate of 1 μg/kg/min. Administration of chitosan-packaged miRNA at 200 μg/kg began 3 days after the start of Ang II delivery and was repeated every 3 days thereafter via retro-orbital injection.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) reached a maximum average of 123 mm Hg in mice treated with miR-29b-CH-NP and 149 mm Hg in Scr-CH-NP treated mice after 2 weeks of Ang II delivery (Figure 2A). This represents a change of 54 mm Hg above baseline in Scr-CH-NP-treated mice and 25 mm Hg increase above baseline in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice (Figure 2B). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) (Figure 2C) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (Figure 2D) also increased more in Scr-CH-NP-treated mice than in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. Heart rate was not different between treatments (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

miR-29b-CH-NP attenuates hypertension in mice treated with Ang II

Blood pressure was measured by a radio telemeter with a catheter in the left carotid artery. Ang II was delivered at 1 μg/kg body weight/minute via osmotic minipumps. Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight on day 3 of Ang II treatment and every 3 days after via retro-orbital injection. (A) Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was significantly lowered by miR-29b-CH-NP. (B) The increase in MAP from baseline blood pressure (ΔMAP) was significantly attenuated by miR-29b-CH-NP treatment. (C) Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was significantly lowered by miR-29b-CH-NP treatment. (D) Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was significantly lowered by miR-29b-C treatment. (E) No significant difference in heart rate (HR) between treatment groups. n = 7 Scr-CH-NP and 8 miR-29b-CH-NP. ∗p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA; #p < 0.05 on given day, Holm-Sidak test. Data are mean ± SEM.

miR-29b-CH-NP attenuates cardiac and renal fibrosis in diabetic db/db mice

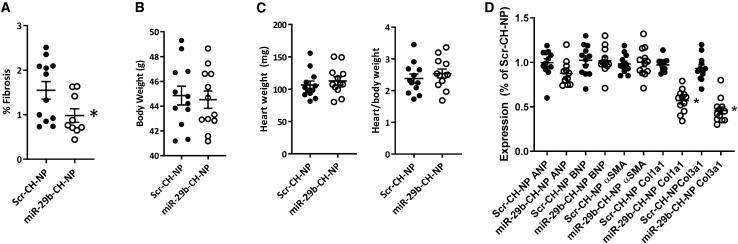

To test the therapeutic effect of miR-29b on diabetic complications, we used db/db mice, a widely used model of type 2 diabetes. Echocardiography and urine collection were performed on alternate weeks for 12 weeks starting at 7 weeks of age (both echo and urine collection were performed during week 12). Chitosan-packaged miRNA was injected into retro-orbital at 200 μg/kg every 3 days.

We found the fibrotic area in the hearts from mice treated with miR-29b-CH-NP was approximately 37% lower than Scr-CH-NP mice (Figure 3A). There was no difference in the total body weight (Figure 3B) or the weight of the heart (Figure 3C) between treatment groups. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) mRNA abundance was not significantly different between Scr-CH-NP- and miR-29b-CH-NP-treated animals (Figure 3D). Collagen 1a1 (Col1a1) and collagen 3a1 (Col3a1) were significantly reduced in animals treated with miR-29b-CH-NP (Figure 3D). We did not detect significant changes in echocardiographic metrics over the 12-week study period in mice treated with Scr-CH-NP or any significant effect for miR-29b-CH-NP.

Figure 3.

miR-29b-CH-NP reduces fibrosis in the hearts of db/db mice

Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight every 3 days via retro-orbital injection starting at 8 weeks of age. Tissues were analyzed when the mice were 20 weeks old. (A) Cardiac fibrosis as % of total heart area was significantly reduced in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. (B) Body weight was not significantly different between treatment groups. (C) Neither heart weight nor heart/body weight ratio was significantly different between treatment groups. (D) ANP, BNP, and αSMA were not significantly different between treatment groups, while Col1a1 and Col3a1 were significantly reduced in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. n = 12 Scr-CH-NP and 9 miR-29b-CH-NP. ∗p < 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, Student’s t test. Data are mean ± SEM.

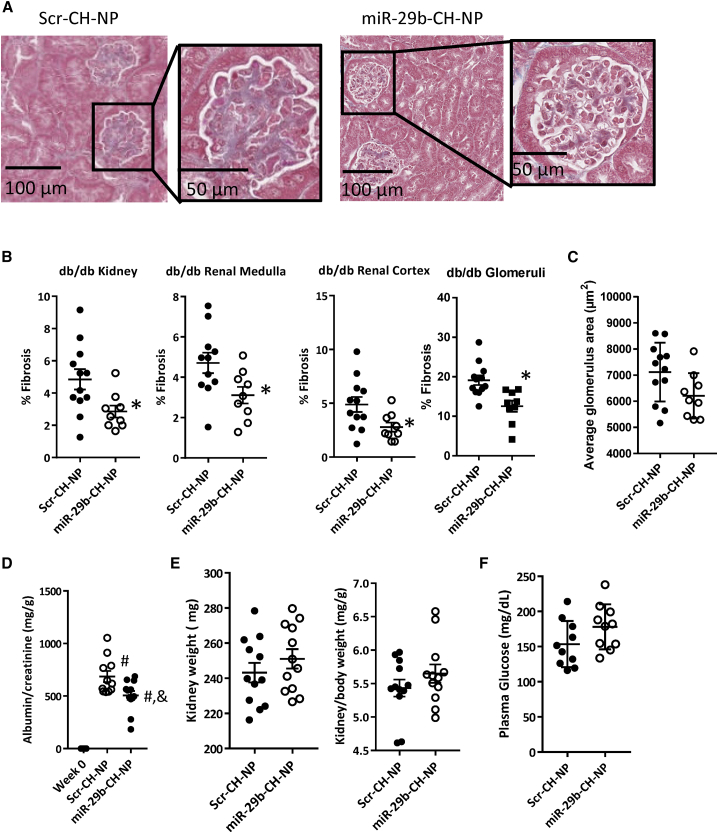

We also assessed fibrosis in the kidney. miR-29b-CH-NP treatment reduced fibrosis by 43% in the renal medulla, 37% in the renal cortex, and 44% in the glomeruli compared with Scr-CH-NP-treated mice (Figures 4A and 4B). Average glomerular area was not significantly affected (Figure 4C). Albuminuria is a key feature of diabetic nephropathy and a strong predictor of adverse outcomes. Compared with Scr-CH-NP-treated mice, miR-29b-CH-NP significantly reduced urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio (Figure 4D). Both Scr-CH-NP and miR-29b-CH-NP had significantly higher urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio compared with baseline week 0 (Figure 4D). No difference was found in kidney weight (Figure 4E) or plasma glucose (Figure 4F) between treatment groups. Plasma creatinine levels were 0.21 ± 0.09 mg/dL and 0.24 ± 0.06 mg/dL in Scr-CH-NP and miR-29b-CH-NP groups (n = 6 and 7, p = 0.75). Plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were 70 ± 23 U/L and 59 ± 31 U/L in the two groups (n = 6 and 8, p = 0.69). The number of samples for these assays was smaller than the whole groups because not all samples had sufficient volumes for both assays.

Figure 4.

miR-29b-CH-NP reduces fibrosis in the kidneys and attenuated albuminuria in db/db mice

Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight every 3 days via retro-orbital injection starting at 8 weeks of age. Tissues were analyzed when the mice were 20 weeks old. (A) Representative Trichrome staining images of the kidney of Scr-CH-NP- or miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice; magnification ×200. (B) Fibrosis was significantly reduced in the whole kidney, renal cortex, renal medulla, and glomeruli with miR-29b-CH-NP treatment. (C) Average glomerular area was not significantly different between treatment groups. (D) Urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio was significantly lowered with miR-29b-CH-NP treatment. (E) Neither kidney weight nor kidney/body weight ratio was significantly different between treatment groups. (F) Plasma glucose was not significantly different between treatment groups. n = 21 Week 0, 12 Scr-CH-NP, and 9 miR-29b-CH-NP. ∗p < 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, Student’s t test. #p < 0.05 versus Week 0, and p < 0.05 versus Scr-NP-CH, one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak test. Data are mean ± SEM.

The thickening of the retina in db/db mice is an indication of diabetic retinopathy. Eyes from the db/db mice were collected and stained with Toluidine blue to visualize the retinal layers. There was no difference in the thickness of the whole retina nor any individual layers between treatment groups.

miR-29b-CH-NP prevents deterioration of myocardial performance and attenuates proteinuria in uninephrectomized db/db mice

We next studied uninephrectomized (Unx) db/db mice, a commonly used model of advanced diabetic nephropathy that also exhibits cardiomyopathy.24,25 Unx db/db mice were studied over 20 weeks starting at 7 weeks of age. Chitosan-packaged miRNA was injected retro-orbitally at 200 μg/kg every 3 days over the 20-week period.

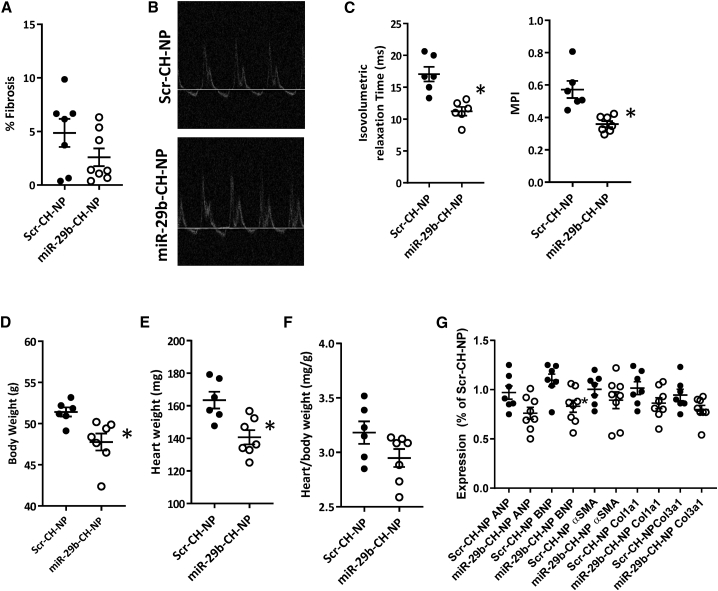

Cardiac fibrosis was substantially greater in both treatment groups in Unx db/db mice compared with non-uninephrectomized db/db mice. miR-29b-CH-NP did not cause a significant reduction compared with Scr-CH-NP (Figure 5A). Most morphological echocardiographic metrics remained similar between treatment groups when short-axis M-mode measurements were examined (Table 1). We used an apical 4-chamber view to perform Doppler ultrasound on the mitral valve to evaluate left ventricular function (Figure 5B). Isovolumetric relaxation time was found to have increased significantly in the Scr-CH-NP-treated animals after 20 weeks of treatment, which was significantly blunted in the miR-29b-CH-NP mice (Figure 5D). This difference led to a significant improvement of the myocardial performance index (MPI) in the miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice compared with Scr-CH-NP-treated mice (Figure 5C). Mitral valve E wave velocity, isovolumetric contraction time, and MPI were all significantly higher in Scr-CH-NP-treated mice compared with baseline week 0 values (Table 1). Although body weight (Figure 5D) and the heart weight (Figure 5E) were significantly lower in the miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice, the difference in heart weights was not significant when normalizing to overall body weight (Figure 5F). ANP tended to be downregulated and BNP was significantly downregulated by the miR-29b-CH-NP treatment (Figure 5G). αSMA, Col1a1, and Col3a1 were not significantly different between treatment groups (Figure 5G).

Figure 5.

miR-29b-CH-NP improves cardiac function in uninephrectomized db/db mice

Db/db mice were uninephrectomized at 7 weeks of age. Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight every 3 days via retro-orbital injection starting at 8 weeks of age. Tissues were analyzed when the mice were 28 weeks old. (A) Cardiac fibrosis was not significantly different between treatment groups. (B) Representative images of apical 4-chamber view Doppler ultrasound recording. (C) Myocardial performance index (MPI) was improved in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice driven by significant decreases in isovolumetric relaxation time. (D) Body weight was decreased in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. (E) Heart weight was decreased in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. (F) Heart/body weight ratio was not significantly different between treatment groups. (G) mRNA abundance of ANP, BNP, αSMA, Col1a1, and Col3a1 was not significantly different between treatment groups. n = 7 Scr-CH-NP, 8 miR-29b-CH-NP. ∗p < 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, Student’s t test. Data are mean ± SEM.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic metrics in uninephrectomized db/db mice

| Variables | Week 0 | Scr-CH-NP | miR-29b-CH-NP | p-value Week 0 versus Scr-CH-NP |

p-value Week 0 versus miR-29b-CH-NP |

p-value Scr-CH-NP versus miR-29b-CH-NP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVID-d (mm) | 3.37 ± 0.10 | 3.81 ± 0.08 | 3.85 ± 0.12 | 0.0386 | 0.0244 | 0.8471 |

| LVID-s (mm) | 2.28 ± 0.08 | 2.42 ± 0.09 | 2.58 ± 0.15 | 0.6431 | 0.1861 | 0.6431 |

| LVPW-d (mm) | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.8042 | 0.6952 | 0.8042 |

| LVPW-s (mm) | 1.09 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 1.16 ± 0.08 | 0.8313 | 0.8313 | 0.9317 |

| LVAW-d (mm) | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.4843 | 0.4843 | 0.9934 |

| LVAW-s (mm) | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.07 | 1.23 ± 0.05 | 0.5262 | 0.5262 | 0.9769 |

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 476 ± 16 | 437 ± 19 | 425 ± 15 | 0.3002 | 0.1622 | 0.6975 |

| Mitral valve E velocity (mm/s) | 739.78 ± 38.09 | 942.40 ± 85.84 | 891.93 ± 35.13 | 0.0459 | 0.0978 | 0.5793 |

| Mitral valve A wave (mm/s) | 442.36 ± 23.89 | 541.65 ± 61.03 | 509.83 ± 18.23 | 0.1772 | 0.3196 | 0.5928 |

| E/A Ratio | 1.69 ± 0.06 | 1.77 ± 0.09 | 1.76 ± 0.10 | 0.8735 | 0.8735 | 0.9568 |

| Isovolumetric contraction time (ms) | 5.57 ± 0.82 | 10.08 ± 1.32 | 6.64 ± 0.97 | 0.0043 | 0.2055 | 0.1015 |

| Isovolumetric relaxation time (ms) | 14.44 ± 1.10 | 17.74 ± 0.80 | 12.40 ± 1.48 | 0.3473 | 0.3473 | 0.1655 |

| Ejection time (ms) | 56.46 ± 2.65 | 49.48 ± 2.83 | 55.71 ± 2.73 | 0.3619 | 0.8648 | 0.4332 |

| MPI | 0.35 ± 0.026 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.0004 | 0.39443 | 0.0015 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 60.20 ± 2.40 | 69.50 ± 3.40 | 59.46 ± 4.01 | 0.1836 | .08712 | 0.1836 |

| Fractional shortening (%) | 31.73 ± 1.75 | 38.91 ± 2.64 | 31.54 ± 2.68 | 0.1409 | 0.9527 | 0.1485 |

N = 15 Week 0, 7 Scr-CH-NP, 8 miR-29b-CH-NP. Data are mean ± SEM. Bold values indicate significance, One-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak test.

LVID-d, left ventricle inner diameter diastole; LVID-s, left ventricle inner diameter systole; LVPW-d, left ventricle posterior wall diastole; LVPW-s, left ventricle posterior wall systole; LVAW-d, left ventricle anterior wall diastole; LVAW-s, left ventricle anterior wall systole; MPI, myocardial performance index.

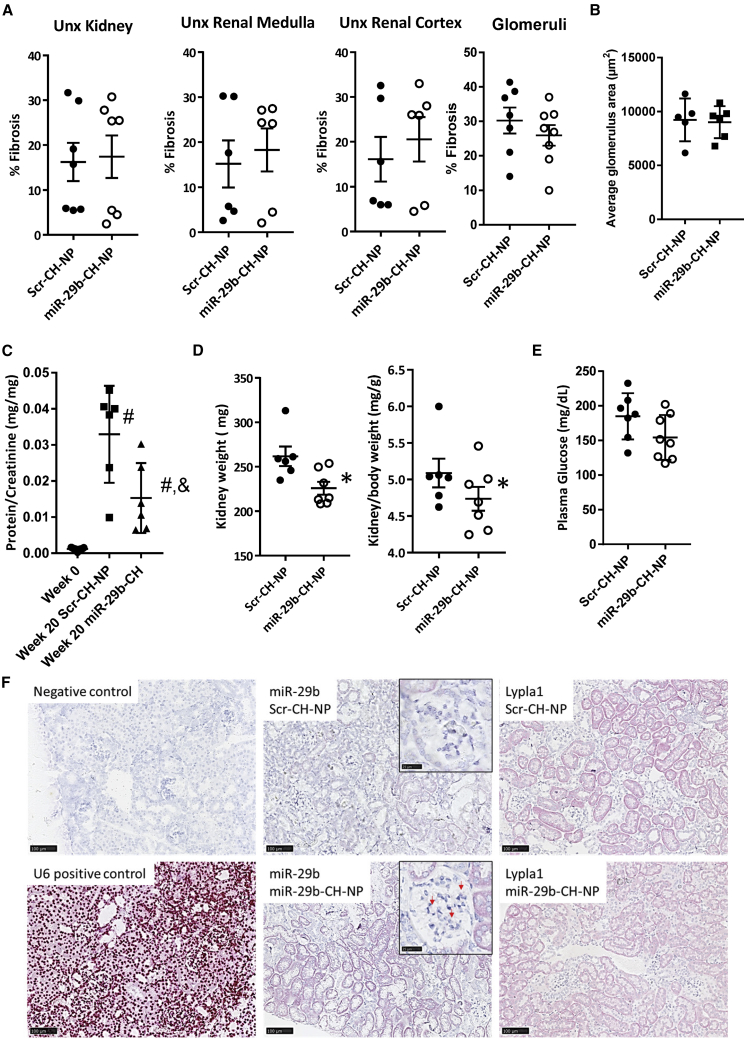

Fibrosis in the kidneys of the Unx db/db mice was nearly three times more prevalent than in non-uninephrectomized db/db mice. Fibrosis was not significantly affected by miR-29-CH treatment in the whole kidney, renal medulla, renal cortex, or glomeruli (Figure 6A). Neither was average glomerular size affected (Figure 6B). Urinary protein/creatinine ratio was significantly lower in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated animals than in Scr-CH-NP-treated animals, although both Scr-CH-NP- and miR-29b-CH-NP-treated animals were significantly elevated compared with baseline week 0 (Figure 6C). Total kidney weight as well as kidney/body weight ratio, an index of renal hypertrophy, were lower in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice (Figure 6D). No difference in plasma glucose was found between treatment groups (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

miR-29b-CH-NP attenuates proteinuria in uninephrectomized db/db mice

Db/db mice were uninephrectomized at 7 weeks of age. Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight every 3 days via retro-orbital injection starting at 8 weeks of age. Tissues were analyzed when the mice were 28 weeks old. (A) Fibrosis was not significantly different in any region of the kidney between treatment groups. (B) Average glomerular size was not significantly different between treatment groups. (C) Urinary protein/creatinine ratio was significantly lower in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. (D) Kidney weight was decreased in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. This difference remained after normalizing to overall body weight. (E) Plasma glucose was not significantly different between treatment groups. (F) miR-29b staining was higher, and Lypla1 was lower, in the kidneys collected at the end of the 20 weeks of miR-29b-CH-NP treatment compared with Scr-CH-NP. Results from miRNAscope and RNAscope analyses are shown. Negative and positive controls were hybridized with a scrambled probe and a U6 probe, respectively. Red arrows point to punctate staining of miR-29 in glomeruli from miR-29b-CH-NP-treated mice. n = 15 Week 0, 7 Scr-CH-NP, 8 miR-29b-CH-NP. ∗p < 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, Student’s t test. #p < 0.05 versus Week 0, & p < 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, one -way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak test. Data are mean ± SEM.

Although miR-29b-CH-NP improved some aspects of renal injury in Unx db/db mice, the improvement was less pronounced than in db/db mice without Unx. We analyzed kidney tissues from Unx db/db mice to confirm that the delivery and effectiveness of miR-29b-CH-NP was sustained through the end of the 20-week treatment protocol. miRNAscope and RNAscope analyses showed higher levels of miR-29b staining and lower levels of Lypla1 staining across the kidney in Unx db/db mice treated with miR-29b-CH-NP compared with Scr-CH-NP (Figure 6F).

Unx db/db mice were euthanized after 20 weeks of study because of a sudden increase in mortality past this time point, possibly due to a compounding failure of the heart and kidneys as both proteinuria and MPI worsened rapidly after 18 weeks of study.

Eyes from the Unx db/db mice were collected and stained with Toluidine blue to visualize the retinal layers. There was no difference in the thickness of the whole retina or any individual layers between treatment groups.

miR-29b-CH-NP does not worsen aortic aneurysm

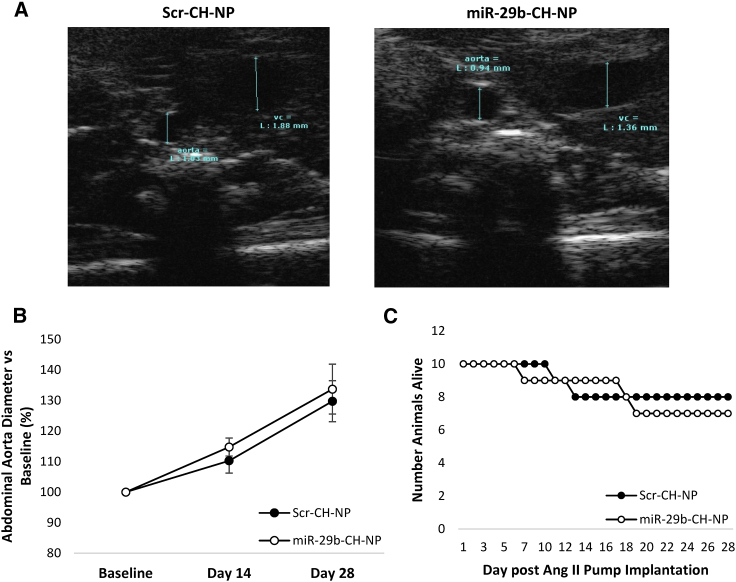

Research performed by other groups has shown that inhibition of miR-29 can be beneficial to aneurysm formation,16,17 which led to the concern that miR-29 mimics could worsen aortic aneurysm. We tested this possibility with our miR-29b formulation in B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J apolipoprotein E knockout mice (ApoE KO) treated with Ang II at 1 μg/kg/min for 4 weeks, a model of aortic aneurysm used in previous studies.16,17 Chitosan-packaged miRNA was injected retro-orbitally every 3 days, similar to what we did in the studies of hypertension and diabetic complications.

The diameter of the suprarenal abdominal aorta was measured using short-axis B-mode ultrasound imaging (Figure 7A). Aortic diameter was not significantly different between treatment groups and increased approximately 40% from baseline in both groups (Figure 7B). Survival was also similar between treatments with a death rate of approximately 25% (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

miR-29b-CH-NP does not affect abdominal aneurysm formation in ApoE KO mice treated with Ang II

Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight every 3 days via retro-orbital injection after Ang II minipump was implanted. (A) Representative images of B-mode ultrasound. (B) Suprarenal abdominal aorta diameter was not significantly changed with miR-29b-CH-NP treatment. (C) Survival rate of aneurysm mice was not different between treatment groups. n = 10 for Baseline. n = 8 Scr-CH-NP, 7 miR-29b-CH-NP at day 28. Data were evaluated with 1-way RM ANOVA. Data are mean ± SEM.

Effect of miR-29b-CH-NP on atherosclerotic plaques

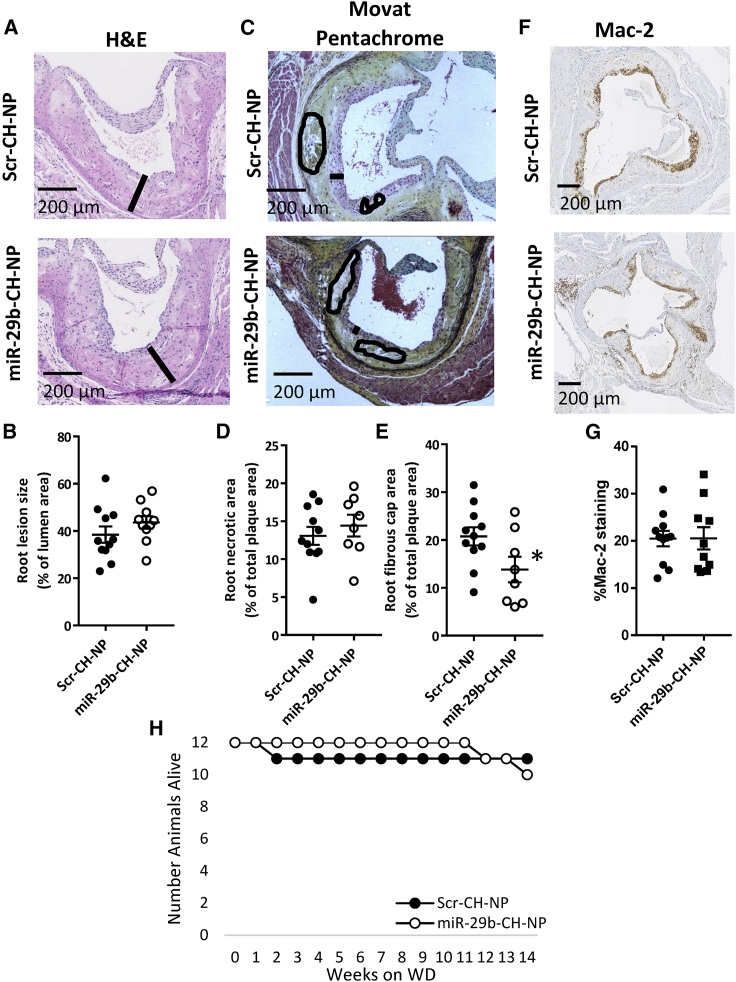

Beneficial effects of chronic down-regulation of miR-29 using LNA anti-miRs have been reported for atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE KO mice.15 We tested the effect of our miR-29b formulation in ApoE KO mice fed a high-cholesterol, high-fat western diet for 14 weeks, a model of atherosclerosis used in the previous study.15 Mice received retro-orbital injections of chitosan-packaged miRNA every 3 days.

Total atherosclerotic burden on the aortic root, determined by staining with H&E (Figure 8A), was not significantly different between treatment groups (Figure 8B). Movat pentachrome staining (Figure 8C) showed that necrotic zone formation also was not significantly affected by the miR-29b-CH-NP treatment (Figure 8D), although the fibrous cap was diminished (Figure 8E). Mac-2 staining was performed (Figure 8F) to evaluate monocyte/macrophage infiltration into the aortic root, which was not significantly different between treatment groups (Figure 8G). No difference in survival rate was observed between Scr-CH-NP- and miR-29b-CH-NP-treated animals (Figure 8H).

Figure 8.

Effects of miR-29b-CH-NP on the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE KO mice fed a western diet

Starting on the day western diet delivery began, Scr-CH-NP or miR-29b-CH-NP was injected at 200 μg/kg body weight every 3 days via retro-orbital injection. (A) Representative images of H&E-stained aortic roots. Black bar represents lesion width. (B) Total lesion size as % of total area was not significantly different between treatment groups. (C) Representative images of Movat pentachrome-stained aortic roots. Black bar represents fibrous cap thickness and circled areas represent necrotic zones. (D) Necrotic zone area as % of total lesion area was not significantly different between treatment groups. (E) Fibrous cap area as % of total lesion area was reduced in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated animals. (F) Representative images of Mac-2 staining. (G) Monocyte/macrophage infiltration into the aortic root was not affected by the miR-29b-CH-NP treatment. (H) Survival rate was not significantly different between treatment groups. n = 12 for Baseline. n = 11 Scr-CH-NP, 10 miR-29b-CH-NP at day 14. ∗p < 0.05 versus Scr-CH-NP, Student’s t test. Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

miRNA therapeutics offer unique benefits with some major challenges. The ability to regulate multiple genes and pathways involved in a disease is an attractive mechanism of miRNAs, but concerns include the delivery, duration of action, and unintended effects.4,5,6,7 While anti-miR therapeutics have advanced toward clinical implementation faster than miRNA mimics, mimics are catching up and have been aided by the advent of nanoparticle packaging.18,19,26,27

The miR-29b-CH-NP that we developed in this study was capable of robust delivery to multiple tissues, suppressed miR-29 target genes Lypla1, Col1a1, and Col3a1 in all examined tissues, and ameliorated hypertension and several aspects of diabetic complications. Of particular interest is the drastic reduction in the dose of miRNA mimic needed, 200 μg/kg body weight in our study compared with doses several hundred fold higher in previous studies. High doses may lead to more unintended effects, and large-scale production of extensively chemically modified oligonucleotides can be prohibitively expensive.

The miR-29b-CH-NP treatment has a considerable anti-hypertensive effect. The ability of miR-29 to relieve Lypla1’s post-translational inhibition of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) likely contributed to this reduction in blood pressure, as we showed previously.9 miR-29a/b1-deficient mice developed systemic hypertension.28 Hypertension was also exacerbated in Mir29b1/a−/− mutant rats generated on the SS.13BN rat background.9 The blood pressure-lowering effect of miR-29b-CH-NP in the current study became apparent after the administration of three doses. It suggests that miR-29b-CH-NP might need to accumulate to reach effective levels, or pathways influenced by miR-29b-CH-NP might become more important as the development of hypertension progresses.

The attenuation of fibrosis in db/db mice by miR-29b-CH-NP may be attributed in part to miR-29’s broad inhibition of ECM gene expression.8,29 In addition, increasing NO bioavailability may also contribute to reducing fibrosis in db/db mice.30 Furthermore, miR-29b-CH-NP may attenuate hypertension in db/db mice, which could contribute to the attenuation of renal injury. Cardiac and renal fibrosis was substantially more severe in Unx db/db mice than in db/db mice,31 which might have overwhelmed the anti-fibrotic effects of miR-29b-CH-NP in these organs. It is possible that miR-29b-CH-NP at a higher dose could attenuate cardiac and renal fibrosis in Unx db/db mice. The beneficial effect of miR-29 on endothelial and possibly tubular function might explain the reduced proteinuria observed in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated Unx db/db mice despite fibrosis not being significantly attenuated.9 eNOS deficiency has been shown to exacerbate podocyte injury and proteinuria in db/db mice.32,33 The miR-29b-CH-NP treatment did not influence the thickness of the retina, suggesting that miR-29b-CH-NP, as used, might not attenuate diabetic retinopathy. miR-29b-CH-NP was injected retro-orbitally, but we did not assess the level of miR-29 in the retina.

MPI measurement is a useful, non-invasive tool for assessing left ventricular function.34 An increased MPI, indicating a worsening of left ventricular function, has been used to detect preclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy in the absence of coronary artery disease or hypertension, and correlates well with diabetic nephropathy and albuminuria.35,36 The lower MPI in miR-29b-CH-NP-treated Unx db/db mice suggests a preservation of systolic function and is consistent with reports of miR-29a/b1-deficient mice developing heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.28

Underlying the role of the miR-29 family as broad ECM suppressors, miR-29 inhibition has been reported to be beneficial for atherosclerotic plaques and aneurysm formation in mouse models.15,16,17 Locked nucleic acid anti-miRs and lentiviral overexpression constructs used in these studies likely result in sustained inhibition or elevation of target miRNAs. Levels of miR-29b tended to return to baseline after 48 h post-injection following the treatment regimen used in the present study. The more transient and pulsatile increase in miR-29b abundance may help to avoid the worsening of aneurysm, atherosclerotic plaque formation, or mortality, except for a thinning of the fibrous cap.

The three members of the miR-29 family, miR-29a, miR-29b, and miR-29c, share a common seed region and thus have broad overlap in predicted targets including Lypla1 and several collagen genes, but there is evidence of isomer-specific functions that do not apply to the whole family.8 For example, we have found that miR-29b uniquely affects nuclear morphology and interacts with proteins that miR-29a and miR-29c do not.37 The shared targeting of Lypla1 and collagen genes suggests the three isoforms might have similar therapeutic effects on hypertension and diabetic complications, but that remains to be tested.

There are conflicting reports of miR-29’s effects on the core diabetic phenotype of hyperglycemia and glucose handling. We did not find any significant effect of miR-29b-CH-NP on non-fasting plasma glucose in db/db or Unx db/db mice, although we did observe a reduction in body weight in Unx db/db mice. A decreased body weight may represent a beneficial or harmful effect of miR-29 in this model of diabetes and obesity.

The study had limitations. Despite our effort to test multiple disease models, each model tested likely recapitulates only some aspects of the human disease. One should be cautious in extrapolating findings in one model to the human disease in general. We used retro-orbital injection because it allowed reliable and consistent delivery in mice. However, this method of delivery is not directly translatable to humans. The administration regimen that we used was effective in treating several conditions. It is likely that optimal administration regimens vary between conditions and would need additional testing. Finally, targeting of Lypla1 and collagen genes provides a plausible explanation for the observed therapeutic effect. However, other pathways may be involved and could be examined in additional mechanistic studies.

In summary, we have demonstrated that chitosan packaging of a custom modified miR-29b allows therapeutic effects in several forms of hypertension and diabetic complications in mouse models while avoiding substantial adverse effects on other cardiovascular conditions tested. The preclinical findings in this study provide a strong basis for developing studies to test the therapeutic effect of miR-29b in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Materials and methods

Animals

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical College of Wisconsin approved all the animal protocols used in this study. All mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories at 7 weeks of age (C57BL/6J JAX #: 000,664; ApoE KO JAX #: 002,052; and B6.BKS(D)-Leprdb/J JAX #: 000,697). All animals had free access to food and water under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Mice were maintained on the AIN-76A containing 0.4% NaCl diet (Dyets, Bethlehem, PA). ApoE KO mice used for atherosclerotic studies were fed a western diet (D12108C, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) containing 1.2% cholesterol and 40% kcal from fat. Male salt-sensitive SS/JrHsdMcwi (SS) rats and consomic SS.13BN rats were obtained from colonies at the Medical College of Wisconsin and maintained on a 0.4% NaCl diet (Dyets).38 Rats were fed a 4.0% NaCl diet for 3 days prior to isolation of arterioles.

Gluteal arteriole isolation and assessment of endothelial function

Rat gluteal arterioles were isolated and vasodilation in response to acetylcholine (Ach) was performed as previously described.9 NO levels were measured in intact arterioles using 4,5-Diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA) fluorescent dye.9

Chitosan packaging of miRNA

Scramble and miR-29b mimics were synthesized and chemically modified by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO), as previously described by Montgomery et al. but the conjugated cholesterol was omitted.11 Chitosan (CH; product number 448869, MW 50–190 kDa, deacetylation ≥75%) and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Scramble and miR-29b mimics were packaged in CH as previously described.19,27,39,40,41 Briefly, miRNA/CH nanoparticles were prepared based on ionic gelation of cationic CH with anionic TPP and miRNA. miRNA/CH nanoparticles were spontaneously generated by the addition of TPP (0.25% w/v) and miRNA (1 μg/μL) to CH solution (2 mg/mL in 0.25% acetic acid) under constant stirring at room temperature. After incubating the miRNA-TPP/CH complex at 4°C for 40 min, CH/miR nanoparticles were collected after spinning at 14,000 rpm fse. or 40 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed three times, dissolved in water (1 μg/μL) and stored at 4°C until used. This protocol produces nanoparticles that are approximately 200 nm in diameter and a ζ potential of approximately 50 mV and broadly distributed to the liver, kidney, spleen, lung, heart, and brain following a retro-orbital injection, as previously reported.27,41

Endothelial cell culture

Human dermal endothelial cells (HMVEC-d) obtained from Lonza (Switzerland) were cultured as previously described.9,42,43 All transfection experiments were carried out when cells were approximately 80% confluent and no older than passage 5.

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol method and real-time RT-PCR performed as previously described.37,44

Separation of endothelium-enriched fractions and vessel remainders from mouse aorta

In mice aortas, endothelium-enriched fractions were extracted as described previously with some modifications.9,45,46 Aortas were mounted on a 22-G needle and secured with suture thread. The lumen was flushed with ice-cold PBS for 10 s, then QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagne Cat. # 79,306) for 10 s, followed by a 10-s pause and a second 10-s elution. Approximately 200 μL of elute was collected and immediately placed on ice after the addition of 1 mL Trizol. Aorta vessel remainders, hearts, and kidney fractions were homogenized in a Rescht TissueLyser II set to 30 shakes per second for 6 min after the addition of 1 mL Trizol. RNA was dissolved in 100 μL DEPC water per heart or kidney sample, 50 μL DEPC water for aortic vessel remainder, and 10 μL DEPC water for aorta lumen elutions.

Injection of chitosan-packaged miRNA mimics

Due to the challenge of reliably identifying the injection into the tail vein of mice, chitosan-packaged miRNAs were delivered via retro-orbital injection using a 0.5-mL insulin syringe equipped with a 0.5-inch 27-G needle (Terumo U-100, Terumo, Japan).47 Syringes were filled with chitosan-packaged miRNA with care taken to ensure no air was in the syringe or needle. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane. Mice were transferred to a clean, 37°C surgical table and oriented prone in the nose cone. With care not to damage the eye, the needle was inserted bevel side down at approximately a 30° angle into the medial canthus. The injectate was injected slowly and smoothly and once complete, the needle was slowly removed.

Telemetry surgery and blood pressure recording

C57 mice had radio telemeters implanted in a carotid artery and blood pressure was measured in conscious, freely moving mice as previously described with some modifications.48,49,50 Blood pressure was measured from 9 AM to noon daily.

Angiotensin II minipump preparation and implantation

Alzet osmotic minipumps (Alzet, Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) were used to chronically deliver Ang II (Millipore-Sigma, A9525) as previously described with some modifications.49,50 ApoE KO mice used for aneurysm studies were implanted with an Alzet model 1004 pump (28 days duration), while C57 mice used for blood pressure studies were implanted with an Alzet model 1002 pump (14 days’ duration). Pumps delivered 1 μg Ang II/kg body weight/minute.

Urine collection and analysis

Db/db and Unx db/db mice were housed in metabolic cages for 24-h periods for urine collection. Mice had free access to food and water. Urine was weighed and aliquoted into two tubes and frozen at −80°C. Urine samples were only thawed once before undergoing analysis as described.49,51

Plasma biochemical assays

Blood was collected from the left ventricle with a 16-G needle on a 1-mL syringe. Blood was transferred to a heparinized 1.7-mL tube and placed on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min to isolate plasma. Plasma was stored at −80°C until testing. Plasma glucose was measured using a glucose colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Item No: 10,009,582, Michigan, USA). Plasma levels of creatinine and ALT were measured on an ACE ALERA Clinical Chemistry System using reagent products SA1012 and SA1052 from Alfa Wassermann following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Echocardiographic measurements

All echocardiography was performed under light isoflurane anesthesia with spontaneous respiration on a Vevo 770 Ultrasound System (Fujifilm, Japan). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. Mice were secured supine on a heated imaging platform by taping paws to the platform. B-mode was used for orientation to the short-axis (transverse plane) mid-papillary level. Parasternal 2-dimensional M-mode recordings were saved and used for analysis of morphology of the heart. Within M-mode, measurements were taken from three cardiac cycles and averaged. For Doppler measurement of mitral valve flow, we used the apical four-chamber view. The table and probe were rotated such that the probe pointed at the apex of the heart with B-mode imaging used for orientation. The ultrasound was changed to Doppler mode and fine adjustments of the imaging platform were made until the E and A waves could be clearly visualized. Doppler measurements were averaged across three cardiac cycles.52

For assessing aortic diameter in ApoE KO mice, B-mode was used for orientation. Short-axis and long-axis views were recorded at three separate locations along the suprarenal abdominal aorta and averaged together. Measurements were taken at the point in the cardiac cycle when the aorta reached maximum diameter.16,17

Cardiac, renal, and optical morphological analysis

Hearts and kidneys were collected and immediately fixed for at least 48 h in 10% formalin. Organs were paraffin embedded, grossed, cut into 4-μm sections, and stained by National Society for Histology certified staff at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Histology Core. Heart and kidney slides from db/db and Unx db/db mice were stained with Masson trichrome for fibrosis analysis. Slides were scanned with a Nikon CoolScan scanner (Nikon, Japan). Quantification of fibrosis was done using an identical color threshold for each image. Eyes from db/db and Unx db/db mice were stained with Toluidine blue O to examine retinal layers. Retinal layers were measured using the line draw tool. Each layer of each slide was measured at five locations that were averaged. Hearts from atherosclerotic ApoE KO mice were sectioned from the apex of the heart up to the aortic root and stained with H&E to assess total atherosclerotic burden, Movat pentachrome to assess necrotic zones and fibrous cap thickness, and Mac-2 stain to assess monocyte/macrophage infiltration. Lines were manually drawn to encompass relevant features and exported as total pixel counts that were used to calculate percentages. All image analysis was performed in MetaMorph 6.1 software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). Approximately 12 fields were examined across each slide to identify representative images.12,49,50,51

Uninephrectomy surgical procedure

Following anesthetization, db/db mice had their right flank shaved and sterilized with betadine first, followed by 70% ethanol. A small incision was made in the left flank and blunt probes were used to part the underlying fat tissue and isolate the kidney. The renal artery and vein were ligated with sterile size 5.0 suture thread tied three times. The kidney was removed by cutting above the tie. The muscle layer was sutured with 5.0 absorbable silk and the skin of the incision site was sutured with 6.0 absorbable silk and antibiotic ointment was applied.

miRNAscope and RNAscope

In situ hybridization analysis of miR-29b and Lypla1 in formalin-fixed kidney tissues was performed using miRNAscope and RNAscope, respectively, following the manufacturer’s instructions and as we described previously.53

Statistics

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical tests are described in figure legends. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL121233, HL125409, GM066730, HL116264, and HL149620, and the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment. We thank Dr. Cristian Rodriguez-Aguayo for valuable input for the study.

Author contributions

D.M.J. and M.L. designed the study. Experiments were performed mostly by D.M.J. and P.H. L.S.M. and G.L.-B. prepared miRNA-CH nanoparticles. A.K.S., J.L., A.J.K., K.U., and M.E.K. provided substantive input for study design or advice and assistance with experiments. D.M.J. and M.L. wrote the paper. Several authors edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.08.007.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotchen T.A., Cowley A.W., Jr., Liang M. Ushering hypertension into a new era of precision medicine. JAMA. 2016;315:343–344. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widlansky M.E., Gokce N., Keaney J.F., Jr., Vita J.A. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42:1149–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang M. MicroRNA: a new entrance to the broad paradigm of systems molecular medicine. Physiol. Genomics. 2009;38:113–115. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00080.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty C., Sharma A.R., Sharma G., Doss C.G.P., Lee S.S. Therapeutic miRNA and siRNA: moving from bench to clinic as next generation medicine. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rupaimoole R., Slack F.J. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:203–222. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rooij E., Olson E.N. MicroRNAs: powerful new regulators of heart disease and provocative therapeutic targets. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2369–2376. doi: 10.1172/JCI33099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kriegel A.J., Liu Y., Fang Y., Ding X., Liang M. The miR-29 family: genomics, cell biology, and relevance to renal and cardiovascular injury. Physiol. Genomics. 2012;44:237–244. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00141.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widlansky M.E., Jensen D.M., Wang J., Liu Y., Geurts A.M., Kriegel A.J., Liu P., Ying R., Zhang G., Casati M., et al. miR-29 contributes to normal endothelial function and can restore it in cardiometabolic disorders. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018;10:e8046. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201708046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rooij E., Sutherland L.B., Thatcher J.E., DiMaio J.M., Naseem R.H., Marshall W.S., Hill J.A., Olson E.N. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:13027–13032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montgomery R.L., Yu G., Latimer P.A., Stack C., Robinson K., Dalby C.M., Kaminski N., van Rooij E. MicroRNA mimicry blocks pulmonary fibrosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014;6:1347–1356. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201303604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue H., Zhang G., Geurts A.M., Usa K., Jensen D.M., Liu Y., Widlansky M.E., Liang M. Tissue-specific effects of targeted mutation of Mir29b1 in rats. EBioMedicine. 2018;35:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Taylor N.E., Lu L., Usa K., Cowley A.W., Jr., Ferreri N.R., Yeo N.C., Liang M. Renal medullary microRNAs in Dahl salt-sensitive rats: miR-29b regulates several collagens and related genes. Hypertension. 2010;55:974–982. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roderburg C., Urban G.W., Bettermann K., Vucur M., Zimmermann H., Schmidt S., Janssen J., Koppe C., Knolle P., Castoldi M., et al. Micro-RNA profiling reveals a role for miR-29 in human and murine liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2011;53:209–218. doi: 10.1002/hep.23922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulrich V., Rotllan N., Araldi E., Luciano A., Skroblin P., Abonnenc M., Perrotta P., Yin X., Bauer A., Leslie K.L., et al. Chronic miR-29 antagonism promotes favorable plaque remodeling in atherosclerotic mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:643–653. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201506031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maegdefessel L., Azuma J., Toh R., Merk D.R., Deng A., Chin J.T., Raaz U., Schoelmerich A.M., Raiesdana A., Leeper N.J., et al. Inhibition of microRNA-29b reduces murine abdominal aortic aneurysm development. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:497–506. doi: 10.1172/JCI61598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merk D.R., Chin J.T., Dake B.A., Maegdefessel L., Miller M.O., Kimura N., Tsao P.S., Iosef C., Berry G.J., Mohr F.W., et al. miR-29b participates in early aneurysm development in Marfan syndrome. Circ. Res. 2012;110:312–324. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krzeszinski J.Y., Wei W., Huynh H., Jin Z., Wang X., Chang T.C., Xie X.J., He L., Mangala L.S., Lopez-Berestein G., et al. miR-34a blocks osteoporosis and bone metastasis by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and Tgif2. Nature. 2014;512:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Pecot C.V., Rupaimoole R., Yang D., Akbani R., Ivan C., Lu C., Wu S., Han H.D., Shah M.Y., Rodriguez-Aguayo C., et al. Tumour angiogenesis regulation by the miR-200 family. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2427. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowley A.W., Jr., Liang M., Roman R.J., Greene A.S., Jacob H.J. Consomic rat model systems for physiological genomics. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2004;181:585–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotchen T.A., Cowley A.W., Jr., Frohlich E.D. Salt in health and disease--a delicate balance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2531–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1305326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drenjancevic-Peric I., Frisbee J.C., Lombard J.H. Skeletal muscle arteriolar reactivity in SS.BN13 consomic rats and Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2003;41:1012–1015. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000067061.26899.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowley A.W., Jr., Roman R.J., Kaldunski M.L., Dumas P., Dickhout J.G., Greene A.S., Jacob H.J. Brown Norway chromosome 13 confers protection from high salt to consomic Dahl S rat. Hypertension. 2001;37:456–461. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayyed S.G., Gaikwad A.B., Lichtnekert J., Kulkarni O., Eulberg D., Klussmann S., Tikoo K., Anders H.J. Progressive glomerulosclerosis in type 2 diabetes is associated with renal histone H3K9 and H3K23 acetylation, H3K4 dimethylation and phosphorylation at serine 10. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2010;25:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaikwad A.B., Sayyed S.G., Lichtnekert J., Tikoo K., Anders H.J. Renal failure increases cardiac histone h3 acetylation, dimethylation, and phosphorylation and the induction of cardiomyopathy-related genes in type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;176:1079–1083. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain K., Kumar R.S., Sood S., Dhyanandhan G. Betaxolol hydrochloride loaded chitosan nanoparticles for ocular delivery and their anti-glaucoma efficacy. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2013;10:493–499. doi: 10.2174/1567201811310050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han H.D., Mangala L.S., Lee J.W., Shahzad M.M.K., Kim H.S., Shen D., Nam E.J., Mora E.M., Stone R.L., Lu C., et al. Targeted gene silencing using RGD-labeled chitosan nanoparticles. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:3910–3922. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caravia X.M., Fanjul V., Oliver E., Roiz-Valle D., Morán-Álvarez A., Desdín-Micó G., Mittelbrunn M., Cabo R., Vega J.A., Rodríguez F., et al. The microRNA-29/PGC1alpha regulatory axis is critical for metabolic control of cardiac function. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2006247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H.Y., Zhong X., Huang X.R., Meng X.M., You Y., Chung A.C., Lan H.Y. MicroRNA-29b inhibits diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:842–853. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khaidar A., Marx M., Lubec B., Lubec G. L-arginine reduces heart collagen accumulation in the diabetic db/db mouse. Circulation. 1994;90:479–483. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin W., Chung A.C.K., Huang X.R., Meng X.M., Hui D.S.C., Yu C.M., Sung J.J.Y., Lan H.Y. TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling promotes renal fibrosis by inhibiting miR-29. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;22:1462–1474. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao H.J., Wang S., Cheng H., Zhang M.Z., Takahashi T., Fogo A.B., Breyer M.D., Harris R.C. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:2664–2669. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuen D.A., Stead B.E., Zhang Y., White K.E., Kabir M.G., Thai K., Advani S.L., Connelly K.A., Takano T., Zhu L., et al. eNOS deficiency predisposes podocytes to injury in diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012;23:1810–1823. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnlöv J., Ingelsson E., Risérus U., Andrén B., Lind L. Myocardial performance index, a Doppler-derived index of global left ventricular function, predicts congestive heart failure in elderly men. Eur. Heart J. 2004;25:2220–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruch C., Schmermund A., Marin D., Katz M., Bartel T., Schaar J., Erbel R. Tei-index in patients with mild-to-moderate congestive heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2000;21:1888–1895. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goroshi M., Chand D. Myocardial Performance Index (Tei Index): a simple tool to identify cardiac dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kriegel A.J., Terhune S.S., Greene A.S., Noon K.R., Pereckas M.S., Liang M. Isomer-specific effect of microRNA miR-29b on nuclear morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:14080–14088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian Z., Greene A.S., Usa K., Matus I.R., Bauwens J., Pietrusz J.L., Cowley A.W., Jr., Liang M. Renal regional proteomes in young Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:899–904. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.109173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard K.A., Rahbek U.L., Liu X., Damgaard C.K., Glud S.Z., Andersen M.Ø., Hovgaard M.B., Schmitz A., Nyengaard J.R., Besenbacher F., Kjems J. RNA interference in vitro and in vivo using a novel chitosan/siRNA nanoparticle system. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaur S., Wen Y., Song J.H., Parikh N.U., Mangala L.S., Blessing A.M., Ivan C., Wu S.Y., Varkaris A., Shi Y., et al. Chitosan nanoparticle-mediated delivery of miRNA-34a decreases prostate tumor growth in the bone and its expression induces non-canonical autophagy. Oncotarget. 2015;6:29161–29177. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu C., Han H.D., Mangala L.S., Ali-Fehmi R., Newton C.S., Ozbun L., Armaiz-Pena G.N., Hu W., Stone R.L., Munkarah A., et al. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by EZH2. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kriegel A.J., Baker M.A., Liu Y., Liu P., Cowley A.W., Jr., Liang M. Endogenous microRNAs in human microvascular endothelial cells regulate mRNAs encoded by hypertension-related genes. Hypertension. 2015;66:793–799. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang M., Pietrusz J.L. Thiol-related genes in diabetic complications: a novel protective role for endogenous thioredoxin 2. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:77–83. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251006.54632.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu P., Liu Y., Liu H., Pan X., Li Y., Usa K., Mishra M.K., Nie J., Liang M. Role of DNA De Novo (De)Methylation in the kidney in salt-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;72:1160–1171. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun X., He S., Wara A.K.M., Icli B., Shvartz E., Tesmenitsky Y., Belkin N., Li D., Blackwell T.S., Sukhova G.K., et al. Systemic delivery of microRNA-181b inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circ. Res. 2014;114:32–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun X., Icli B., Wara A.K., Belkin N., He S., Kobzik L., Hunninghake G.M., Vera M.P., MICU Registry. Blackwell T.S., Baron R.M., Feinberg M.W. MicroRNA-181b regulates NF-kappaB-mediated vascular inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:1973–1990. doi: 10.1172/JCI61495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yardeni T., Eckhaus M., Morris H.D., Huizing M., Hoogstraten-Miller S. Retro-orbital injections in mice. Lab Anim. 2011;40:155–160. doi: 10.1038/laban0511-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y., Usa K., Wang F., Liu P., Geurts A.M., Li J., Williams A.M., Regner K.R., Kong Y., Liu H., et al. MicroRNA-214-3p in the kidney contributes to the development of hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018;29:2518–2528. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018020117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker M.A., Wang F., Liu Y., Kriegel A.J., Geurts A.M., Usa K., Xue H., Wang D., Kong Y., Liang M. MiR-192-5p in the kidney protects against the development of hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:399–406. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng Y., Wang D., Wang F., Liu J., Huang B., Baker M.A., Yin J., Wu R., Liu X., Regner K.R., et al. Endogenous miR-204 protects the kidney against chronic injury in hypertension and diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020;31:1539–1554. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019101100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mladinov D., Liu Y., Mattson D.L., Liang M. MicroRNAs contribute to the maintenance of cell-type-specific physiological characteristics: miR-192 targets Na+/K+-ATPase beta1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1273–1283. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broberg C.S., Pantely G.A., Barber B.J., Mack G.K., Lee K., Thigpen T., Davis L.E., Sahn D., Hohimer A.R. Validation of the myocardial performance index by echocardiography in mice: a noninvasive measure of left ventricular function. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2003;16:814–823. doi: 10.1067/S0894-7317(03)00399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams A.M., Jensen D.M., Pan X., Liu P., Liu J., Huls S., Regner K.R., Iczkowski K.A., Wang F., Li J., et al. Histologically resolved small RNA maps in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis indicate progressive changes within glomerular and tubulointerstitial regions. Kidney Int. 2022;101:766–778. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.