Abstract

Background:

Nurses have crucial roles in caring for patients and preventing the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, nurse managers have a prominent role during the pandemic, being responsible for the support and training of the nursing team to ensure quality care. While performing their duties in this time of fear and uncertainty, nurse managers face several challenges.

Aim:

To identify the challenges faced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

It is an integrative literature review whose search for articles was carried out in Medline, PubMed and Scopus. Qualitative content analysis was used.

Results:

Twelve primary research studies were included. Four themes emerged: (1) Workplace demands, (2) Impacts on physical and psychological health, (3) Coping measures and resilience and (4) Recommendations to better support nurse managers in times of crisis. Nurse managers had their roles expanded or completely changed, and they experienced many pressures and stressors in the workplace. Nurse managers also faced physical and psychological health problems. Nurse managers drew on experience; management skills; social media applications; support from family, colleagues and hospital administrators; training, and continuing education to solve the problems that emerged due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Organisations should use collaborative, inclusive and participatory practices for better crisis management.

Conclusions:

Knowing the experiences of nurse managers during the pandemic period may help health institutions and policymakers better prepare for emergencies.

Keywords: COVID-19, emergency plans, leadership, nurse administrators, nursing, pandemics

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) emerged in China in late December 2019 and was declared a pandemic in March 2020 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020a). Today, more than 2 years after its emergence, the disease caused by the Coronavirus of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is still present and continuing to infect people and be a leading cause of death (WHO, 2022). The pandemic, which is a threat to all humanity, has undoubtedly brought greater challenges to healthcare workers, especially nurses who, according to WHO (2020b), represent 59% of healthcare workers in the world.

The physical and psychosocial health of nurses has been threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic due to various reasons such as shortages of human resources and medical supplies, lack of Protective Personal Equipment (PPE) and limited hospital beds (Sun et al., 2020). The wearing of PPE has been a challenge for some nurses leading to skin problems and excess sweat (Hu et al., 2020). Fear, insomnia, stress, anxiety, depression and burnout are reported by nurses in many studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (Galehdar et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Sampaio et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020). Many of the problems experienced by nurses are alleviated by competent nursing management, and with the advent of COVID-19, the role of nurse managers has become even more pivotal. Mainly in the early stages of the pandemic, nurse managers had to support their team members, allowing flexible hours and breaks, correctly managing stocks of medical supplies and PPE, and giving emotional support, thus promoting a positive work environment (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2020; Raso, 2020; Rodrigues and Silva, 2020). Not only frontline nurses but also nurse managers are still facing many challenges due to the pandemic that cause them physical and psychological health problems. In order to have technical and emotional competence, and be able to support their teams, nurse managers need to be well prepared for crisis management (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Raso, 2020).

Roles of nurse managers

A nurse manager like any other administrator has functions such as planning, organising, directing and controlling; using technical, human and conceptual skills. Nurse managers supervise and direct nursing services and units of public and private health institutions. They have roles related to care and administration (Newham and Hewison, 2021). In other words, they have all the knowledge and technical skills required for frontline nurses (Lai et al., 2018), and at the same time administrative skills needed for managers (Newham and Hewison, 2021). Technical skills are necessary for the manager to develop operational and strategic activities. Competence in interpersonal relationships is one of the most important abilities for the manager; therefore, a successful manager is someone who knows how to interact with different types of people (Joshi, 2012). In addition, managers need skills to analyse situations from diverse points of view so that they can make appropriate decisions (Joshi, 2012).

During their daily routine, nurse managers face many challenges, which may be related to leadership styles they adopt, ineffective communication and the emergence of conflicts with professionals from the multidisciplinary team, or with patients and their families (Ferreira et al., 2019; Goktepe et al., 2020).

Nurse managers have roles as mentors, directors and monitors, thus they need to train and manage not only the nursing team but also the support staff while interacting with various employees; it is common for nurse managers to experience interpersonal conflicts (Goktepe et al., 2020). It is important to emphasise that training nurses is a challenge, as the nursing profession requires various skills and effort. Furthermore, the workload of nurses is hard and wages may be not satisfactory (Lai et al., 2018), thus nurses can often leave their jobs due to poor working conditions. Staff shortages and turnover intention are very common in the nursing profession in several countries around the world (McGill University, 2019). Newly hired nursing staff mean a greater workload for the manager, who will have roles in training and supporting them throughout the adaptation process (Goktepe et al., 2020).

The importance of the nursing manager’s tasks became even more evident with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic because in an uncertain and risky scenario they used their care and administrative skills to make quick decisions to protect and support the nursing team, patients and community as a whole (Tan et al., 2020). More flexible working hours were planned, relocation of staff was organised, provision of PPE was controlled, training was developed and emotional support was provided to ensure the physical and mental safety of health care professionals and patients (Labrague and De Los Santos, 2020; Tan et al., 2020). Leading in times of COVID-19 is challenging, especially if the group led is one of the most demanding and exhausted, as is the nursing team. Therefore, special training is required so that nurse managers know how to act in times of crisis.

Crisis management

Nursing has a crucial mission when global crises affect the healthcare sector. Nurses receive leadership education during undergraduate courses; they are trained in personnel management and operations planning (Hopkinson and Jennings, 2021). Preparing staff for a variety of crises begins with learning about the different types of responses needed, such as in the face of a hurricane, storm or terrorist attack. In many countries, nurses and nursing leaders receive crisis management training through continuing education programmes (Loke et al., 2021). During the training, they are aware of the realistic possibilities of such events, and they learn strategies designed to ensure the safety of patients and professionals (Livornese and Vedder, 2017). Nurses need the minimum knowledge base and skills to respond to emergencies; be able to care directly or provide indirect support during emergencies, prepare the community to act during crises; and be professional, participating in emergency planning and training (Veenema et al., 2016). As there is always thepossibility of disasters or other emergency events, which can range from cardiac arrests to pandemics, floods, hurricanes, earthquakes and terrorist attacks, nurses must always be ready to act in critical moments, so nursing leaders must be prepared to train and evaluate their team members because in a moment of crisis there is no time for training; prompt and appropriate action is required (Livornese and Vedder, 2017).

As much as health professionals are prepared for moments of crisis, the advent of the pandemic showed the need to better prepare the health system for such periods (Baugh et al., 2020). Preparing nursing staff to respond to a pandemic requires extensive training that will extend as the pandemic continues and new needs arise, so training and hence competence acquisition is an ongoing process (Bernhardt and Benoit, 2021). It is emphasised that knowledge in leadership, quality, safety and population health are essential so that nurses can meet the demands that arise during emergencies (Hoffmann et al., 2020).

Determining space for care, training the staff in the use of equipment and supplies, organising the nursing team, coordinating the flow of patients and recognising the team’s emotional needs were some topics that were part of nurse managers’ expertise during crisis management in the pandemic (Hopkinson and Jennings, 2021). Nursing care is provided based on science, holism, humanism and creativity and innovation (Hayes et al., 2021), so nursing leadership needs to consider the collective intelligence, knowledge and needs of the nursing community while planning caring and operational strategies (Rosser et al., 2020). During the pandemic, nursing leaders are being tested in a risky and unknown field, where they do not have books or much evidence to follow (Raso, 2020). Understanding the importance of the topic, this integrative review aimed to identify the challenges faced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

To carry out this integrative review, the five steps described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) were used. This approach was chosen because it presents a modified structure to address specific issues of the integrative review method, such as problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation of results (Whittemore and Knalf, 2005).

Search strategy

The search was conducted in Medline, PubMed and Scopus using the descriptors: (‘nurse manager’ OR ‘nurse administrator’) AND (Covid). The search for original primary research articles was carried out in February 2022 and it was not limited by language or publication date.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Primary research articles related to ‘nurse manager and Covid’ whose full texts were available on the Internet were included in this literature review. Studies that included other participants besides nurse managers; grey literature, systematic or literature reviews, or discussion articles were excluded.

Screening

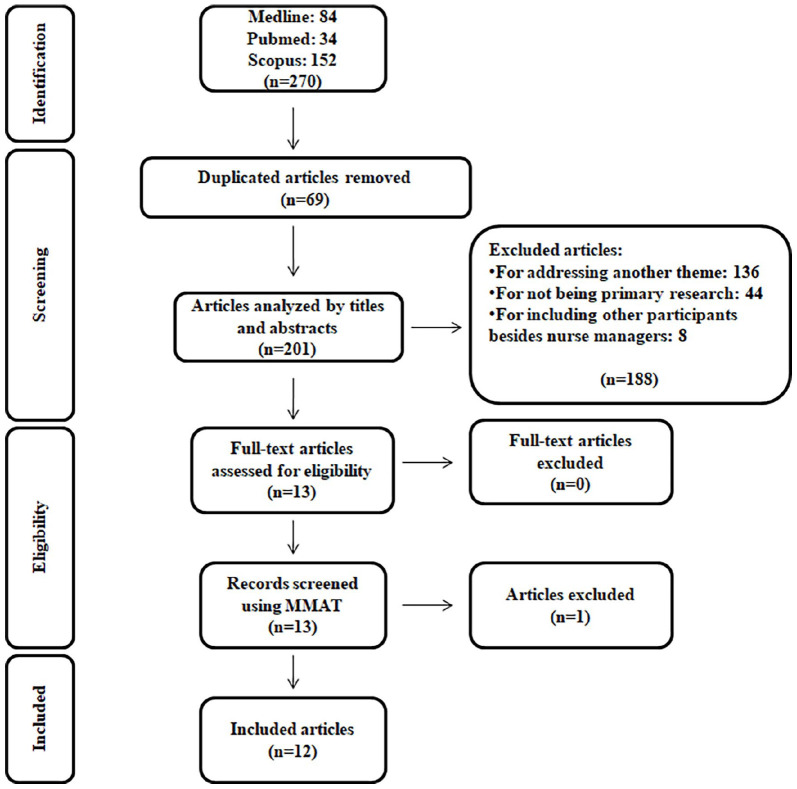

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) was used (Figure 1). A total of 270 articles were found through the electronic databases, 69 duplicated articles were removed. Titles and abstracts of the 201 remaining articles were screened. After that, 188 studies were excluded because they did not match the objective of this review. A total of 13 articles were read and re-read in detail, and all were included in the quality appraisal.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search, screening and selection of articles for the integrative review.

Data extraction

A descriptive instrument was used to organise the general information extracted from the selected articles. The instrument contains the following headings: references, title, journal, country, aim, design, participants and main results (Table 1). Relevant data are also included in the quality appraisal (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of results of the 12 articles included in the review.

| Author (year) | Title/Journal/Country | Aim | Design/Participants | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha (2021) | ‘Experiences of first-line nurse managers during COVID-19: A Jordanian qualitative study’/Journal of Nursing Management/Jordan | ‘To explore the experiences of Jordanian first-line nurse managers during COVID-19.’ | A qualitative study of 16 nurse managers. Data were collected through semi-structured face-to-face interviews. | Themes: ‘Unprecedented pressure, strengthening system and resilience, building a supportive team, and maturity during the crisis.’ |

| Deldar et al. (2021) | ‘Nurse managers’ perceptions and experiences during the COVID-19 crisis: A qualitative study’/Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research/Iran | ‘To elaborate on the nurse managers’ experiences facing the Coronavirus pandemic.’ | A qualitative study of 18 nurse managers. Data were collected via face-to-face semi-structured interviews. | Themes: ‘Facing the personnel’s mental health, managerial and equipment provision challenges, and adaptability and exultation process.’ |

| Gab Allah (2021) | ‘Challenges facing nurse managers during and beyond COVID-19 pandemic in relation to perceived organizational support’/Egypt Nursing Forum | ‘To explore challenges facing nurse managers during and beyond coronavirus disease, 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and its relation to perceived organizational support.’ | A descriptive correlational study of 214 nurse managers. Data were collected using a questionnaire of challenges faced by nurse managers and survey of organisational support. | High level of challenges was found. |

| Holge-Hazelton et al. (2021) | ‘Improving person-centred leadership: A qualitative study of ward managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 crisis’/Risk Management and Healthcare Policy/Denmark | ‘To reflect and learn how person-centred nursing leadership may be strengthened in such situations.’ | A qualitative study of 13 nurse managers. Data were collected by telephone using semi-structured interview guide. | Themes: ‘Leadership beliefs and values, sense of community, balancing different stakeholder needs, involvement in decision-making, and personal development.’ |

| Jackson and Nowell (2021) | ‘The office of disaster management’ nurse managers’ experiences during COVID-19: A qualitative interview study using thematic analysis’/Journal of Nursing Management/Canada and The United States of(US) | ‘To understand the experiences of nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic.’ | A qualitative study of eight nurse managers. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews. | Themes: ‘The COVID context, changing the nurse manager role, managing transitions, nurse manager experiences of COVID-19.’ |

| Jónsdóttir et al. (2022) | ‘There was no panic’—Nurse managers’ organising work for COVID-19 patients in an outpatient clinic: A qualitative study’/Journal of Advanced Nursing/Iceland | ‘To provide insight into the contribution of nursing to the establishment and running of a hospital-based outpatient clinic for COVID-19 infected patients and thereby to inform the development of similar nursing care and healthcare more generally.’ | A qualitative study of five nurse managers. Data were collected through focus group interviews. | Themes: ‘Everyone walked in step, and inspired by extraordinary accomplishments.’ |

| Kagan et al. (2021) | ‘A Mixed-methods study of nurse managers’ managerial and clinical challenges in mental health centers during the COVID-19 pandemic’/Journal of Nursing Scholarship /Israel | ‘To examine the managerial and clinical challenges of nurse managers in mental health centers during the current COVID-19 pandemic.’ | A mixed-methods study of 25 nurse managers. Data were collected via a self-administered questionnaire developed by the researchers and through focus groups. | Challenges regarding the clinical impact of the pandemic were reported. Themes: ‘Management complexity, challenging communication, and bright spots.’ |

| Losty and Bailey (2021) | ‘Leading through chaos perspectives from nurse executives’/Nursing Administration Quarterly/US | ‘To ascertain the essence of nurse executive leadership and innovation during the COVID-19 crisis.’ | A qualitative study of six nurse managers. Data were collected through interviews. | Themes: ‘The importance of communication; the need for leadership presence; and mental toughness.’ |

| Middleton et al. (2021) | ‘The COVID-19 pandemic – A focus on nurse managers’ mental health, coping behaviours and organisational commitment’/Collegian/Australia | ‘To investigate the mental health, coping behaviours, and organisational commitment among Nurse Managers during the COVID-19 pandemic.’ | A cross-sectional study of 59 nurse managers. Data were collected through a demographic questionnaire, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Brief-Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (B-COPE) Inventory, and the organisational commitment questionnaire. | High anxiety scores. More experienced nurse managers had higher scores for adaptive coping strategies and 41% of participants considered leaving their jobs. |

| Moyo et al. (2022) | ‘ Experiences of nurse managers during the COVID-19 outbreak in a selected district hospital in Limpopo province, South Africa’/ Healthcare/South Africa | ‘To explore the experiences of ten nurse managers who were purposively selected from different units of a selected district hospital.’ | A qualitative study of 10 nurse managers. Data were collected through telephonic unstructured interviews. | Themes: ‘Human resource related challenges, material resources during COVID-19 era in the ward, Increased workload, and stigma and discrimination.’ |

| Vázquez-Calatayud et al. (2022) | ‘Experiences of frontline nurse managers during the COVID-19: A qualitative study’/Journal of Nursing Management/ Spain | ‘To explore experiences of frontline nurse managers during COVID-19.’ | A qualitative study of 10 nurse managers. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews. | Themes: ‘Constant adaptation to change, participation in decision-making, management of uncertainty, prioritization of the biopsychosocial well-being of the staff, preservation of humanized care and one for all.’ |

| White (2021) | ‘A phenomenological study of nurse managers’ and assistant nurse managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States’/ Journal of Nursing Management/US | ‘To understand the experiences of hospital nurse managers and assistant nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.’ | A qualitative study of 13 nurse managers. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews. | Themes: ‘Being there for everyone; leadership challenges; struggles, support and coping; and strengthening my role.’ |

Table 2.

Evaluation of the quality of articles according to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). a

| Reference | Screen questions | 1. Qualitative studies | 2. Randomised controlled trials | 3. Nonrandomised studies | 4. Quantitative descriptive studies | 5. Mixed-methods studies | Decision | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria b | S1 | S2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Carter and Turner (2021) | Y | Y | CT | N | CT | Y | CT | E | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Deldar et al. (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gab Allah (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Holge-Hazelton et al. (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Jackson and Nowell (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Jónsdóttir et al. (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kagan et al. (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||

| Losty and Bailey (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Middleton et al. (2021) | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Moyo et al. (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vázquez-Calatayud et al. (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| White (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | I | ||||||||||||||||||||

MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) is a critical appraisal tool developed for the appraisal of quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies included in systematic mixed-studies reviews.

Criteria: Screening questions: (S1) Are there clear research questions? (S2) Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? Qualitative questions: (1.1) Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? (1.2) Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? (1.3) Are the findings adequately derived from the data? (1.4) Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? (1.5) Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? Randomised controlled trials: (2.1) Is randomisation appropriately performed? (2.2) Are the groups comparable at baseline? (2.3) Are there complete outcome data? (2.4) Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? (2.5) Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? Nonrandomised studies: (3.1) Are the participants representative of the target population? (3.2) Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? (3.3) Are there complete outcome data? (3.4) Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? (3.5) During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? Quantitative descriptive studies: (4.1) Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? (4.2) Is the sample representative of the target population? (4.3) Are the measurements appropriate? (4.4) Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? (4.5) Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? Mixed-methods studies: (5.1) Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed-methods design to address the research question? (5.2) Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? (5.3) Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? (5.4) Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? (5.5.) Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? CT, cannot tell; E, excluded; I, Included; N, no; Y, yes.

Quality appraisal

The articles were assessed using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). Using the MMAT is possible to appraise the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies, which makes it suitable for evaluating different studies included in integrative reviews (Hong et al., 2018). MMAT is a tool that allows a classification of criteria, not using a general score to refer to the quality of the articles. After quality assessment, one article was excluded due to the small sample size and lack of information on sampling strategy, measurements and adequate statistical analysis. Regarding the methodological quality of the included studies, the most common weakness found in quantitative studies was the use of self-report questionnaires, which is considered a limitation due to the possibility of providing invalid answers (Demetriou et al., 2015). The most common weakness found in qualitative studies was related to the duration of interviews, as some lasted less than 30 minutes. The results of the quality assessment are shown in Table 2. In total, 12 articles were included in this review.

Analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used. This type of analysis is used in integrative reviews to summarise evidence and offer new knowledge based on the synthesis of varied original studies (Mikkonen and Kaariainen, 2020). Similar information extracted from the included studies was organised into codes and themes by the author using grammatical methods (Saldana, 2013). Four themes emerged: (1) Workplace demands, (2) Impacts on physical and psychological health, (3) Coping measures and resilience and (4) Recommendations to better support nurse managers in times of crisis.

Results

The 12 included articles are from 9 different journals. Nine (75%) studies are from 2021. The number of participants varied from 5 to 214 nurse managers. Studies were carried out in the United States (n = 2), Australia (n = 1), Canada and the United States (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), Iceland (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), Jordan (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1) and Spain (n = 1). In eight studies, the majority of participants were female; in three studies, gender was not mentioned (Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2021; Losty and Bailey, 2021), and in one study, the majority of participants were male (Deldar et al., 2021). Concerning methodology; nine (75%) studies were qualitative, two (16.67%) studies were quantitative (Gab Allah, 2021; Middleton et al., 2021) and one (8.33%) was a mixed-methods study (Kagan et al., 2021). The 12 articles included in this review had objectives related to experiences, challenges or perspectives of nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In all of them, challenges faced by nurse managers were identified. Results are discussed into four themes: (1) Workplace demands, (2) Impacts on physical and psychological health, (3) Coping measures and resilience and (4) Recommendations to better support nurse managers in times of crisis.

Workplace demands

The literature identified that nurse managers experienced several pressures and stressors due to the unprecedented context of the pandemic (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Gab Allah, 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021). Nurse managers’ roles have been expanded or completely changed by the pandemic (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Kagan et al., 2021; Moyo et al., 2022; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021). Becoming ordinary nurses rather than managers due to understaffing (Kagan et al., 2021; Moyo et al., 2022; White, 2021), screening for all workers and visitors (Moyo et al., 2022) and managing protective equipment and ventilators all the time (White, 2021) were identified as new roles for nursing managers during the pandemic. Increased workload (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Gab Allah, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Middleton et al., 2021; Moyo et al., 2022; White, 2021) with longer shifts (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; White, 2021), no breaks (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021) and a lot of administrative work such as filling out government documents and counselling staff members (Moyo et al., 2022) were some challenges reported by nurse managers.

Shortages of human resources (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021 Middleton et al., 2021; Moyo et al., 2022), especially lack of trained nurses (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022), dealing with infected staff (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Moyo et al., 2022; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022), changing shifts due to special cases such as pregnant staff, lactating mothers and personnel with underlying diseases (Deldar, et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021), leading new teams (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022), managing unfamiliar clinics (Jackson and Nowell, 2021), weakened multidisciplinary team work (Kagan et al., 2021), ensuring staff safety (Gab Allah, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021), facing nurses’ worries, fears (Deldar et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; White, 2021), anxiety (Deldar et al., 2021; Middleton et al., 2021; White, 2021) and burnout (Deldar et al., 2021) were some of the staff-related pressures and stressors that nurse managers faced in the workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nurse managers also reported shortages of medical supplies (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Middleton et al., 2021; Moyo et al., 2022), lack of PPE (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Kagan et al., 2021; Moyo et al., 2022), limited hospital beds (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021), visitor restrictions (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Kagan et al., 2021; Losty and Bailey, 2021) and unclear guidance (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Kagan et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022) as difficulties that threatened nursing management during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The need to protect patients from infection, lack of adequate communication with patients (Kagan et al., 2021), and being a bridge between patients and their families (Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022) were also pressure triggers for nurse managers. In addition, in some cases working from home and leading from a distance (Jackson and Nowell, 2021), in others being always present for their staff (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; White, 2021), concerns related to personnel morale (Gab Allah, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021), making difficult decisions, family factors (Gab Allah, 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022), lack of training and monetary rewards, violence (Gab Allah, 2021), communication issues (Gab Allah, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021) and community image (Gab Allah, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021) were pointed out by nurse managers as challenges faced by them in this crisis period.

Political views were addressed in different ways. In one study, messages from political leaders were reported as barriers to nursing managers as they prevented hospital administrators from responding to COVID-19 because some decisions were not evidence-based but made according to the political climate (Jackson and Nowell, 2021). On the other hand, a study emphasised that the cohesion and consistency of civil servants were important points to solve the problems that emerged (Jónsdóttir et al., 2022).

Impacts on physical and psychological health

Nurse managers working during the COVID-19 pandemic were threatened physically and psychologically. They emphasised that concerns related to staff nurses and patients were grounds for substantial emotional labour (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022). So that some of them wanted to leave their jobs (Middleton et al., 2021). Tiredness (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; White, 2021), fatigue, exhaustion, muscle weakness, aching muscles, loss of appetite (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021), weight gain and insomnia (White, 2021) were pointed out by nurse managers as impacts on their health. In addition, wearing PPE for long hours was a physical challenge for nurse managers, as the equipment was heavy, making them sweat and limiting their movements (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021).

Fear of infecting others or getting infected and dying (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Gab Allah, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021), stress (Gab Allah, 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Moyo et al., 2022; White, 2021), anxiety (Gab Allah, 2021; Middleton et al., 2021; White, 2021), depression (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; White, 2021), worrying, distress, frustration (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021), loneliness (Kagan et al., 2021; White, 2021), burnout (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Kagan et al., 2021), stigma and discrimination (Moyo et al., 2022), lack of understanding, (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021) powerlessness and lack of recognition (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021) were some of the psychological problems faced by nurse managers.

Coping measures and resilience

Studies included in this review identified nurse managers’ coping measures and resilience methods. The literature reported how nurse managers acted to compensate for the lack of materials and shortages of human resources (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022). Nurse managers relied on evidence, creativity (Jackson and Nowell, 2021), decision-making abilities, planning skills and autonomy to maintain the quality of care (Jónsdóttir et al., 2022) and ensure staff safety (Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022).

Nurse managers used guidelines (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022); modified emergency plans (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2021) such as distributing the experienced staff among different hospital shifts (Deldar et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022); they also organised training (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022), workshops, virtual seminars and continuing education (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Deldar et al., 2021); used social media for acquiring and transmitting knowledge (Deldar et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2021; Losty and Bailey, 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021), and telehealth to support the community (Jónsdóttir et al., 2022).

Training and continuing education, including topics such as new procedures, use of ventilators and PPE (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021), policies of infection control and how to interact with COVID-19 patients (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Losty and Bailey, 2021) and their relatives (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021) were used by nurse managers for better prepare their teams. Nurse managers were more professional than emotional (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021), but they also encouraged the staff’s religious resilience (Deldar et al., 2021).

Studies pointed out the importance of the support provided by administrative members (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Gab Allah, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021). Motivation, rewards, logistical support, transparent management (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021), and open communication were reported by nurse managers as pivotal measures for coping with challenges that emerged due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021).

Nurse managers also pointed out that feeling safe and not alone was important for them to alleviate the pressures in the workplace (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021). Support from family (White, 2021) and colleagues (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021), besides mutual respect and teamwork (Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022) were key points for nurse managers to develop resilience in times of COVID-19.

Some nurse managers faced the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity for developing self-awareness (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021), improving teamwork and collaboration (Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022), increasing management abilities and leadership competencies, such as decision-making, problem-solving, critical thinking, communication skills (Abu Mansour and Abu Shosha, 2021) and delegating (White, 2021). Nurse managers also reported that being valued (Jónsdóttir et al., 2022) and feeling proud of their roles were sources of resilience (Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2021). In addition, nurse managers emphasised their educational management training (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022) and experience (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jónsdóttir et al., 2022; Middleton et al., 2021) helped them solve problems that arose during the pandemic.

Recommendations to better support nurse managers in times of crisis

Nurse managers pointed out the need to be better prepared for crises (Kagan et al., 2021). It was reported that if a crisis is managed properly and sufficient support strategies are taken, threats can turn into opportunities to empower nurse managers and staff (Deldar et al., 2021; Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Losty and Bailey, 2021). Continuing education on disaster management, ethical decision-making and leadership within daily practices will help nurse managers to build necessary skills and better lead their teams in times of crisis (Gab Allah, 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; Middleton et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022). In addition, the need for organised systems to support nurse managers due to the emotional exhaustion caused by the pandemic and related factors, such as social isolation was identified (White, 2021).

Organisations should replace their hierarchical practices with collaborative, inclusive and participatory practices (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021). In a crisis like the current one, nurse administrators from all levels should participate in the decisions made in health institutions and also the other members of the nursing team should be heard (Holge-Hazelton et al., 2021; Jackson and Nowell, 2021; White, 2021).

Discussion

This integrative review was conducted to identify the challenges faced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies highlighted that nurse managers are facing many challenges due to the pandemic. Nurse leaders had their roles expanded or completely changed, and they experienced many pressures and stressors in the workplace, such as shortages of human resources and medical supplies, work overload, lack of understanding due to unclear guidance or miscommunication, concern for patients and staff, and decisions of political leaders. Nurse managers faced physical and psychological health problems. Experience, management skills; social media applications; support from family, colleagues and hospital administrators; training, and continuing education were pivotal for nurse managers to solve the problems that emerged with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse managers emphasised the need to be better prepared for emergencies, and that organisations should use collaborative, inclusive and participatory practices for better crisis management.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 and all the uncertainties surrounding the disease have represented and still represent challenges for nurse managers (Hopkinson and Jennings, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic showed that health systems need to be better prepared for emergencies (Bernhardt and Benoit, 2021). One of the most important roles of nurse managers during the pandemic was to train staff, especially in the use of PPE, and plan the stock of medical supplies (Hopkinson and Jennings, 2021). Nevertheless, with the increase in the number of infected patients, the planning of human and medical resources has become increasingly a challenge (Sun et al., 2020).

Bed expansion, identification of nursing teams, training, emotional support and internal patient flow are some strategies that are part of nurse managers’ emergency plans (Hopkinson and Jennings, 2021). However, lack of detailed information, limited hospital beds, shortages of human resources and medical supplies, lack of PPE (Raso, 2020) and nurses’ psychosocial experiences (Galehdar et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020) are pointed out as factors that hinder the success of these plans. Protocols that changed all the time, lack of adequate communication and unclear guidelines may lead to confusion and be barriers for nurse managers when leading their teams as such problems can threaten the quality of care as well as the safety of healthcare workers (Rodrigues and Silva, 2020, WHO, 2020c).

Similar situations happened during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Kim, 2018) and Ebola (Kollie et al., 2017) outbreaks, when the lack of understanding, limited equipment, (Kollie et al., 2017), shortages of human resources and lack of guidelines (Kim, 2018) were reported by nurses and midwives. Also, loneliness (Kim, 2018), anxiety, (Kollie et al., 2017) and fear (Kim, 2018; Kollie et al., 2017) were identified in healthcare workers during other outbreaks.

Regarding all the changes that emerged due to the COVID-19 pandemic, nurse managers had to adapt quickly, rethink the system of care, the distribution of personnel and train staff in record time (Raso, 2020). In addition, COVID-19 identified the need to integrate technologies and health care (Hoffmann et al., 2020). All these pressures and stressors impacted the physical and psychological health of nurse managers. Results of studies conducted with healthcare workers are in line with the results of this review as they identified physical health impacts, especially due to the use of PPE (Hu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020), and psychological problems such as fear, anxiety, stress, insomnia and others, among caregivers working during the COVID-19 pandemic (Galehdar et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Sampaio et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020).

Open communication between staff nurses and managers (Hoffmann et al., 2020), quick thinking, decision-making skills, flexibility (Raso, 2020), and caring relationships are important points for providing a positive work environment in health institutions (Moore, 2020). In addition, nursing managers must be role models for their team members, strengthening ethical behaviour in nursing (Markey et al., 2021). In many studies, the approach of nurse managers is identified as having an important impact on the work environment and the quality of care (Galehdar et al., 2021; Sampaio et al., 2021). Nurse managers need to support their teams through training and policies that empower and motivate their nurses (Galehdar et al., 2021; Sampaio et al., 2021). Nursing professionals are pivotal for the control of healthcare crises; and especially nurses who took education in leadership are better prepared to develop responses to COVID-19 (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Therefore, nurse managers also need to be taught, trained and supported to act in crises. Studies identified the importance of better preparing nurse managers for emergencies (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Moore, 2020; Udod et al., 2021). It is important to highlight that crises can also be seen as opportune moments for nurse managers to develop administrative competence, awareness and job satisfaction (Moore, 2020). The importance of good leadership is highlighted as being essential for the success of any activity. During the COVID-19 pandemic, much is said about the important role of the nursing team in facing the crisis; quality nursing care cannot be provided if there is no competent leadership. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the situation of nurse managers and support them at critical moments.

Limitations

This integrative review has some limitations. Only three databases were used and relevant databases were left out, so important studies may not have been included. Although the search was not limited by the language of publication, only literature published in English was included in this review, therefore, relevant studies published in other languages may have been missed either by the search restricted to the three databases or due to the descriptors used.

Conclusion

Nurse managers are facing many challenges since COVID-19 emerged and they need to be better prepared for times of crisis. They experience several problems in the workplace, which impact their physical and psychological health. Management skills, training, support from colleagues, and especially support from hospital administrators help nurse managers to deal with COVID-19. When nursing managers are heard and participate in organisational decisions, the results achieved are more efficient and effective. Therefore, knowing the experiences of nurse managers during the pandemic period may help health institutions and policymakers better prepare for emergencies. Further research conducted through broader search criteria should be done to explore additional sources related to the challenges experienced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research.

Nurse managers experienced many pressures and stressors in the workplace due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Experience, management skills; social media applications; support from family, colleagues, and hospital administrators; training, and continuing education were pivotal for nurse managers to solve the problems that emerged with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nurse managers emphasised the need to be better prepared for emergencies.

Health institutions should use collaborative, inclusive, and participatory practices for better crisis management.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrn-10.1177_17449871221124968 for Challenges faced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review by Ana Luiza Ferreira Aydogdu in Journal of Research in Nursing

Biography

Ana Luiza Ferreira Aydogdu is a Registered Nurse with an interest in cross-cultural nursing, nursing management and leadership. She is a Postgraduate in Public Health Nursing, a Master in Hospital and Health Institution Administration and a PhD in Nursing Management. She currently works as an Assistant Professor at Istanbul Health and Technology University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The ethical aspects of the study were guaranteed through the legitimacy of information and authorship of the researched articles, which were cited and referenced properly according to the referencing system rules. As it is an integrative review, there was no need to acquire ethical permissions.

ORCID iD: Ana Luiza Ferreira Aydogdu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0411-0886

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0411-0886

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Abu Mansour SI, Abu Shosha GM. (2021) Experiences of first-line nurse managers during COVID-19: A Jordanian qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management 2021: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh JJ, Yun BJ, Searle E, et al. (2020) Creating a COVID-19 surge clinic to offload the emergency department. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 38: 1535–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt JM, Benoit EB. (2021) Perceptions of clinical leaders’ abilities to lead COVID-19 clinics. Nursing Management 52: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M, Turner KM. (2021) Enhancing nurse manager resilience in a pandemic. Nurse Leader 19: 622–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deldar K, Froutan R, Ebadi A. (2021) Nurse managers’ perceptions and experiences during the COVID-19 crisis: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 26: 238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou C, Ozer BU, Essau CA. (2015) Self-report questionnaires. In: Cautin RL, Lilienfeld SO. (eds) The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira VHS, Teixeira VM, Giacomini A, et al. (2019) Contributions and challenges of hospital nursing management: Scientific evidence. Revista Gaucha de Enfermagem 40: e20180291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gab Allah AR. (2021) Challenges facing nurse managers during and beyond COVID-19 pandemic in relation to perceived organizational support. Nursing Forum 56: 539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galehdar N, Toulabi T, Kamran A, et al. (2021) Exploring nurses’ perception of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A qualitative study. Nursing Open 8: 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goktepe N, Turkmen E, Kebapci A, et al. (2020) Executive nurses’ views about nursing work environment: A qualitative study. Saglik ve Hemsirelik Yonetimi Dergisi (Journal of Health and Nursing Management) 7: 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes C, Wood LJ, Gaden NW, et al. (2021) The dual epidemics of 2020 nursing leaders? reflections in the context of whole person/whole systems. Nursing Administration Quarterly 45: 243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann RL, Battaglia A. (2020) The clinical nurse leader and COVID-19: leadership and quality at the point of care. Journal of Professional Nursing 36: 178–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holge-Hazelton B, Kjerholt M, Rosted E, et al. (2021) Improving person-centred leadership: A qualitative study of ward managers’ experiences during the covid-19 crisis. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 14: 1401–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. (2018) Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Canadian Intellectual Property Office. Canada. Available at: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteriamanual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed 19 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson SG, Jennings BM. (2021) Nurse leader expertise for pandemic management: Highlighting the essentials. Military Medicine 186: 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Kong Y, Wengang L, et al. (2020) Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine 24: 100424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILO (Organización Internacional del Trabajo – OIT) (2020) Cinco Formas de Proteger al Personal de Salud Durante la Crisis del COVID-19. Geneva: OIT. Spanish. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_740405/lang–es/index.htm (accessed 19 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Nowell L. (2021) ‘The office of disaster management’ nurse managers’ experiences during COVID-19: A qualitative interview study using thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Management 29: 2392–2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jónsdóttir H, Sverrisdóttir SH, Hafberg A, et al. (2022) “There was no panic”—Nurse managers’ organising work for COVID-19 patients in an outpatient clinic: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 78: 1731–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi M. (2012) Administration Skills.In Ebook. https://www.academia.edu/2584515/Administration_Skills (accessed 19 July 2022).

- Kagan I, Shor R, Ben Aharon I, et al. (2021) A mixed-methods study of nurse managers’ managerial and clinical challenges in mental health centers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 53(6): 663–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. (2018) Nurses’ experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control 46: 781–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollie ES, Winslow BJ, Pothier P, Gaede D. (2017) Deciding to work during the Ebola outbreak: The voices and experiences of nurses and midwives in Liberia. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences 7: 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L J, De Los Santos JA. (2020) COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management 28: 1653–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai FY, Lu SC, Lin CC, et al. (2018) The doctrine of the mean: Workplace relationships and turnover intention. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration 36: 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu YE, Zhai ZC, Han YH, et al. (2020) Experiences of front-line nurses combating coronavirus disease-2019 in China: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nursing 37: 757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livornese K, Vedder J. (2017) The emotional well-being of nurses and nurse leaders in crisis. Nursing Administration Quarterly 41: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke AY, Guo C, Molassiotis A. (2021) Development of disaster nursing education and training programs in the past 20 years (2000–2019): A systematic review. Nurse Education Today 99: 104809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losty LS, Bailey KD. (2021) Leading through Chaos: Perspectives from Nurse Executives. Nursing Administration Quarterly 45: 118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey K, Ventura CAA, Donnell CO, et al. (2021) Cultivating ethical leadership in the recovery of COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Management 29: 351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill University (2019) Global shortage of nurses. Ingram School of Nursing, November 1–24. Available at: https://www.mcgill.ca/nursing/files/nursing/nurse_shortages.pdf (accessed 19 July 2022).

- Middleton R, Loveday C, Hobbs C, et al. (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic – A focus on nurse managers’ mental health, coping behaviours and organisational commitment. Collegian 28: 703–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkonen K, Kaariainen M. (2020) Content analysis in systematic reviews. In: Kyngäs H, Mikkonen M, Kääriäinen M. (eds) The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research. Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. (2020) Nurse leadership during a crisis: Ideas to support you and your team. Nursing Times 116: 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo I, Mgolozeli SE, Risenga PR, et al. (2022) Experiences of nurse managers during the COVID-19 outbreak in a selected district hospital in Limpopo province, South Africa. Healthcare (Switzerland) 10: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newham R, Hewison A. (2021) COVID-19, ethical nursing management and codes of conduct: An analysis. Nursing Ethics 28: 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raso R. (2020) Leadership in a pandemic: Pressing the reset button. Nursing Management 51: 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues NH, Silva LGA. (2020) Gestão da pandemia Coronavírus em um hospital: Relato de Experiência (Management of the coronavirus pandemic in a hospital: Professional experience report). Journal of Nursing and Health 10: e20104004. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser E, Westcott L, Ali PA, et al. (2020) The need for visible nursing leadership during COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 52: 459–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. (2013) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 2nd edn. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio F, Sequeira C, Teixeira L. (2021) Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on nurses’ mental health: A prospective cohort study. Environmental Research 194: 110620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Wei L, Shi S, et al. (2020) A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control 48: 592−598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R, Yu T, Luo K, et al. (2020) Experiences of clinical first-line nurses treating patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management 28: 1381–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udod S, MacPhee M, Baxter P. (2021) Rethinking resilience: Nurses and nurse leaders emerging from the post-COVID-19 environment. The Journal of Nursing Administration 51: 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Calatayud M, Regaira-Martínez E, Rumeu-Casares C, et al. (2022) Experiences of frontline nurse managers during the COVID-19: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management 30: 79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema TG, Griffin A, Gable AR, et al. (2016) Nurses as leaders in disaster preparedness and response-A call to action. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 48: 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JH. (2021) A Phenomenological study of nurse managers’ and assistant nurse managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Journal of Nursing Management 29: 1525–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. (2005) The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020. a) Timeline of WHO’s response to COVID-19. Switzerland, Geneva: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline (accessed 19 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020. b) State of the world’s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. Switzerland, Geneva: WHO. https://www.icn.ch/system/files/2021-07/WHO-SoWN-English%20Report-0402-W:-LOW%20RES_2020.pdf (accessed 19 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020. c) Communicating and managing uncertainty in the COVID-19 pandemic: A quick guide. Switzerland, Geneva: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/whe/coronavirus19/managing-uncertainty-in-covid-19-a-quick-guide.pdf (accessed 19 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2022) WHO Coronavirus (COVID-91) dashboard. Switzerland, Geneva: WHO. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 19 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrn-10.1177_17449871221124968 for Challenges faced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review by Ana Luiza Ferreira Aydogdu in Journal of Research in Nursing