Abstract

PtlC is a member of a set of proteins necessary for the secretion of pertussis toxin (PT) from Bordetella pertussis. Using polyclonal antibodies specific for PtlC, we identified PtlC as a protein with an apparent molecular weight of 85,000 that localizes to the membrane fraction of bacterial cell extracts. We found that a mutant strain of B. pertussis that contains an in-frame deletion in ptlC is unable to secrete PT and that PT secretion is fully restored by expressing ptlC in trans, indicating that PtlC is essential for transport of PT across the bacterial membrane(s). PT secretion was inhibited in wild-type B. pertussis after introduction of a plasmid expressing a mutant ptlC altered in the putative nucleotide-binding region, suggesting that this region of PtlC is essential for proper function. Moreover, the observed dominant negative phenotype suggests that PtlC either functions as a multimer or interacts with some other component(s) necessary for secretion of PT.

Bordetella pertussis, the etiological agent of pertussis (whooping cough), employs a number of cellular products including adhesins and toxins that act as virulence factors. One well-studied virulence factor of B. pertussis is pertussis toxin (PT), which is thought to be essential for the successful establishment and persistence of infection in animal models of the disease (31). PT comprises five polypeptide subunits, S1 through S5, which assemble through noncovalent interactions in a 1:1:1:2:1 ratio, adopting an A-B toxin architecture (28). The B oligomer, a ring-shaped structure made up of S2, S3, S4, and S5, serves to bind to glycoproteins on the host cell surface for delivery of the holotoxin to the interior of the cell (3, 29, 35). The S1 subunit is the enzymatic portion of the toxin that ADP-ribosylates a class of G proteins, resulting in alterations in cellular signal transduction (16, 17).

For PT to exert its effects on eucaryotic cells, it must first be secreted from the bacteria. Recently, the ptl (pertussis toxin liberation) genes were found to be critical for export of the toxin from the bacteria (32). The ptl gene cluster maps to the region directly downstream from the PT structural genes and contains nine open reading frames, ptlA to -I, which are predicted to encode proteins that form a PT secretion apparatus (9, 32). The ptx and ptl genes are cotranscribed from the Bvg-regulated promoter just upstream of ptxS1 (18).

Further support for the formation of a secretion apparatus by Ptl proteins comes from studies that show their relatedness to the gene products from other gram-negative bacteria which encode the transport machinery of conjugal DNA transfer systems (34). In addition, predicted Ptl proteins are closely related to 9 of 11 VirB proteins that are essential for transfer of T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to plant cells (32). Thus, the PT export system has apparently been adapted from the transport phase of conjugal transfer and is grouped with members of type IV secretion systems (6).

We have previously reported (5) that two of the Ptl proteins, PtlC and PtlH, contain putative nucleoside triphosphate (NTP)-binding sites first described by Walker et al. (30). Nucleotide-binding proteins might play several roles in the secretion process, including providing the energy for the transport process or signaling the opening of a gate or channel via kinase activity. In this study, we examined one of these putative nucleotide-binding proteins, PtlC, to determine its importance in PT secretion and the role that the putative NTP-binding site might play in the transport process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The strains of B. pertussis, Bordetella bronchiseptica, and Escherichia coli and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. pertussis and B. bronchiseptica strains were grown at 37°C on Bordet-Gengou (BG) agar containing 15% defibrinated sheep blood, 1.0% glycerol, and 1.5% peptone (Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) or in Stainer-Scholte liquid medium. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C on L agar or in L broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). When required, antibiotics were added to growth media at the following concentrations: for B. pertussis and B. bronchiseptica, gentamicin sulfate at 10 μg/ml, tetracycline at 10 μg/ml, ampicillin at 50 μg/ml, streptomycin at 100 μg/ml, and nalidixic acid at 50 μg/ml; and for E. coli, carbenicillin at 100 μg/ml, gentamicin sulfate at 10 μg/ml, and kanamycin at 30 μg/ml. X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; Promega, Madison, Wis.) was added to media at 40 μg/ml to assess β-galactosidase production.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype, phenotype, or characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169(φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Gibco-BRL |

| SM10λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc:Mu λpirR6K | 25 |

| B. bronchiseptica Bb55 | Avirulent live vaccine strain; hemolytic | ATCC 31437 |

| B. pertussis | ||

| BP536 | Nalr Strr derivative of Tohama I strain BP338 | 27 |

| BP536ΔptlC | Strain BP536 with a 540-bp deletion in the ptlC gene between coordinates 5198 and 5738 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Cloning vector | Gibco-BRL |

| pUFR047 | Broad-host-range (IncW) vector; Gmr, Apr, Mob+, mob(IncP1), LacZα+ | 7 |

| pSS1129 | Gene replacement vector | 26 |

| pSZH4 | pUC19 containing the ptx-ptl region of B. pertussis | 11 |

| pSZH5 | pUFR047 containing the ptx-ptl region of B. pertussis | 11 |

| pDCNP1.4 | pUC19 containing nucleotides 4322–5738 of the ptl region | This study |

| pDCCH1 | pUC19 containing ptlC | This study |

| pET-CH1 | pET28a containing N-terminal His-tagged ptlC | This study |

| pDMC15 | pUC19 containing the ribosomal binding site from pET-24b followed by ptlC | This study |

| pDMC19 | pUC19 containing ptlC with a deletion from nucleotides 5198–5738 | This study |

| pDMC24 | pSS1129 containing ptlC::tetr | This study |

| pDMC25 | pSS1129 containing ptlC with a deletion from nucleotides 5198–5738 | This study |

| pDMC26 | pUFR047 containing ptlC (nucleotides 4322–6796) | This study |

| pDMC48 | pUFR047 containing ptlC with Lys462→Arg mutation | This study |

Enzymatic manipulation of DNA.

Digestion of plasmid DNA or DNA fragments by restriction endonucleases was carried out as recommended by the manufacturer (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Ligations were performed in reactions using ATP-dependent T4 DNA ligase (Gibco-BRL).

Amplification of B. pertussis DNA by PCR.

Reagents for PCR amplification of B. pertussis DNA were purchased from Perkin-Elmer/Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, N.J. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Lofstrand Labs Limited (Gaithersburg, Md.) or synthesized by the Facility for Biotechnology Resources (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration [CBER, FDA], Bethesda, Md.). B. pertussis Tohama I DNA, kindly provided by Z. M. Li (CBER, FDA), was used as the template. Reactions were performed as previously described (14).

Cloning of ptlC in E. coli.

The ptlC gene was constructed in pUC19 in a stepwise fashion. First, the 5′ end of ptlC between coordinates 4322 and 4709 (Fig. 1) was amplified as a 378-bp NdeI-EcoRI fragment by PCR using the upstream primer (5′-GGCATATGAACCGGCGCGGCGGCCAGACC-3′; NdeI site underlined; ptl nucleotides 4322 to 4345) and downstream primer (5′-CCAGGGTGAGGTAGAATTCGTTCGTCATTGCCTGC-3′; EcoRI site underlined; ptl nucleotides 4709 to 4675). The product was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and cloned into pUC19. Sequencing of this clone confirmed that no PCR-derived nucleotide changes were present. Next, an EcoRI-PstI fragment representing ptlC sequence from coordinates 4691 to 5198 of pSZH4 (Table 1) was added, followed by addition of the adjacent 540-bp PstI fragment of ptlC (coordinates 5198 to 5738) of pSZH4, resulting in pDCNP1.4.

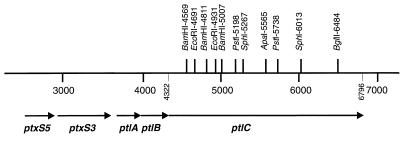

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the ptlC region of the ptx-ptl locus and genetic map of the surrounding region. Nucleotides are numbered as described previously (21).

The 3′ end of ptlC was amplified as a 785-bp SphI-HindIII fragment (coordinates 6013 to 6796 included) by PCR using the upstream primer (5′-ACGGTGCTGCGCATGCCGGCGTCGCT-3′; SphI site underlined; ptl nucleotides 6002 to 6027) and downstream primer (5′-GGAAGCTTTCACCTGAGGCCGGCGCTGGCTTCG-3′; HindIII site underlined; ptl nucleotides 6796 to 6772) and cloned into pUC19. To eliminate PCR-derived DNA from this plasmid, we digested it with SphI and BglII (thereby eliminating ptl sequence between nucleotides 6013 and 6484) and replaced this fragment with the native 477-bp SphI-BglII sequence from pSZH4. The sequence of the region between the BglII site and the TGA stop codon of ptlC was determined to confirm that no errors created by PCR were present. The 790-bp SphI-HindIII fragment from this plasmid was excised and inserted into plasmid pDCNP1.4 which had been digested with SphI and HindIII. Finally, the SphI fragment, containing ptl nucleotides 5267 through 6013 from pSZH4, was ligated into the unique SphI site of this plasmid to reconstitute ptlC in plasmid pDCCH1.

To transfer ptlC to a broad-host-range vector capable of expressing this gene in B. pertussis, the NdeI-HindIII fragment of pDCCH1 containing ptlC was inserted into the pET-24b(+) vector (Novagen Inc., Madison, Wis.) that had been digested with the same enzymes. The XbaI-HindIII fragment of the resulting plasmid, which now contained a ribosomal binding site followed by ptlC, was then cloned into pUC19 to generate pDMC15. The SstI-HindIII fragment from this plasmid was then cloned into the broad-host-range plasmid pUFR047, immediately downstream from the lac promoter found on this vector, to make pDMC26.

Construction of an in-frame deletion in ptlC in B. pertussis.

A 540-bp portion of ptlC between coordinates 5198 and 5738 was precisely excised from the chromosome of B. pertussis BP536 by using allelic exchange mutagenesis (26) in the following manner. Plasmid pDCCH1 was digested with NdeI and PstI to remove the region of ptlC between coordinates 4322 and 5738. A DNA fragment containing the vector portion plus the remaining ptlC sequences between coordinates 5738 and 6796 was extracted from agarose and purified for ligation. The region between coordinates 4322 and 5198 (882 bp) was amplified by PCR with the upstream primer 5′-GGCATATGAAGCTTATGAACCGGCGCGGCGGCCAGACC-3′ (NdeI site underlined, HindIII site in boldface; nucleotides 4322 to 4345 of ptlC) and the downstream primer 5′-GCGCTGCCGCTGCAGGTAGGCCAG-3′ (PstI site underlined, nucleotides 5212 to 5189 of ptlC). The gel-purified vector containing nucleotides 5738 to 6796 was ligated with the NdeI-PstI-digested PCR fragment to generate pDMC19.

Next, a 1.3-kb tetracycline resistance (Tetr) cassette flanked by PstI sites was generated by PCR using the vector pALTER (Promega) as the template DNA. This fragment was inserted into the PstI site of pDMC19. This plasmid was restricted with HindIII to release the 3.2-kb ptlC::Tetr fragment, which was cloned into the HindIII site of pSS1129, the suicide vector used for allelic exchange, to generate pDMC24. Likewise, a 1.9-kb HindIII fragment from pDMC19 containing ptlC with a 540-bp deletion between coordinates 5198 to 5738 was cloned into the HindIII site of pSS1129 to construct pDMC25 (Table 1). Each of the plasmids pDMC24 and pDMC25 was transformed into E. coli SM10λpir.

Plasmid pDMC24 was introduced into B. pertussis BP536 by biparental mating. BP536 cells in which pDMC24 had cointegrated at the chromosomal ptlC locus by homologous recombination were selected on BG plates containing nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml) and gentamicin sulfate (10 μg/ml). Next, purified colonies were plated to BG agar containing streptomycin to select for cells that had lost pDMC24 (Sms [streptomycin sensitive]) by homologous recombination between the plasmid-encoded and chromosomal copies of ptlC sequences. Integration of the Tetr gene, a marker for the loss of the 540-bp segment of ptlC, was confirmed by plating Smr colonies onto BG agar containing tetracycline (10 μg/ml). These Smr Tetr colonies were designated BP536ptlC::tet.

To create the in-frame deletion in ptlC, we introduced pDMC25 into strain BP536ptlC::tet by biparental mating. As described above for pDMC24, antibiotic selections were imposed for two homologous recombination events that resulted in exchange the chromosomal region of ptlC marked with Tetr with sequences from pDMC25 containing the precise 540-bp in-frame deletion. Loss of Tetr was used as a marker for the resultant strain, which we designated BP536ΔptlC.

Construction of a point mutation in the sequence encoding amino acids in the putative NTP-binding domain of PtlC.

A point mutation was made in the coding sequence (AAG; nucleotides 5705 to 5707) for the invariant lysine residue (K462) within the Walker-type NTP-binding motif of PtlC (Fig. 2). The coding sequence for K462 (AAG) was mutated to encode arginine (AGG) by amplifying the region of ptlC between restriction sites ApaI and PstI (coordinates 5565 to 5738), using the upstream primer (5′-ATGGCAACCCCTGGGGCCCGGCCCTGA-3′, ApaI site underlined; coordinates 5553 to 5579) and downstream primer (5′-TTTCTGCAGCTGGCAAAGCAGGAAATTGAGCAGCACGGTCCTGCCGCTGCC-3′, PstI site underlined; coordinates 5746 to 5696, which include the codon altering Lys462→Arg). The PCR-derived product was digested with ApaI and PstI, and the 178-bp fragment was ligated into pBluescript KS(−) (Stratagene, Inc.) to generate plasmid pBS-K462R. The point mutation within this region of ptlC was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

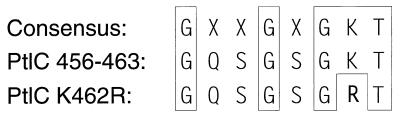

FIG. 2.

Alteration of the putative nucleotide-binding region of PtlC. The consensus Walker box A region is shown along with the corresponding region from PtlC (amino acids 456 to 463). Shown in boldface is the L462→Arg alteration made by site-specific mutagenesis.

The region between the ApaI and PstI sites containing the mutation was introduced into a wild-type clone of ptlC as follows. A 332-bp PstI-BamHI fragment was isolated from pDMC31B [pGEM-7Zf+ (Promega) containing nucleotides 5267 to 6013 of the ptl region (derived from pSZH4)]. This fragment, which contains the PstI-SphI region (coordinates 5738 to 6013) followed by 52 bp of the polylinker of the vector that contains the BamHI site, was ligated with pBS-K462R that had been digested with PstI and BamHI to construct plasmid pDMC40. A 318-bp ApaI fragment consisting of the 306-bp SphI-ApaI region of ptlC (coordinates 5267 to 5565) and 12 bp of the pDMC31B polylinker that includes an ApaI site was also isolated from pDMC31B. This ApaI fragment was then joined to pDMC40 by ligation to form plasmid pDMC44. Digestion of pDMC44 with SphI released a 752-bp fragment that was cloned into the SphI site of pDMC15 (Table 1), resulting in plasmid pDMC45. Full-length ptlC containing the specific Lys→Arg mutation was excised from pDMC45 by digestion with SstI and HindIII. This fragment was then ligated into pUFR047 to construct pDMC48.

Production and partial purification of recombinant PtlC in E. coli.

We used the pET expression system to overproduce recombinant PtlC. The entire coding sequence for ptlC was removed from pDCCH1 by digestion with NdeI and HindIII. The gel-purified fragment was then cloned into the expression vector pET-28a (Novagen), resulting in plasmid pET-CH1. Expression of ptlC from this plasmid results in the addition of a 2,000-Da N-terminal leader with a hexahistidine tag. Plasmid pET-CH1 was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) by transformation. Overproduction of PtlC in E. coli BL21(DE3)(pET-CH1) was carried out as specified by the manufacturer (Novagen). We determined that the majority of His-tagged PtlC produced in E. coli was present in insoluble inclusion bodies. After induction of E. coli BL21(DE3)(pET-CH1) for ptlC expression, cells were harvested from a 150-ml culture by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 15 min), washed once with 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA, and resuspended in 12.5 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0) containing 300 mM NaCl. Cells were lysed by two passages through a French pressure cell (12,000 to 14,000 lb/in2). The insoluble material was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet containing insoluble material was solubilized in 10 ml of 0.1 M NaH2PO4–0.01 M Tris (pH 8.0) containing 5 mM imidazole and 6 M guanidine-HCl. The solubilized protein mixture was purified by chromatography over Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A portion of the purified preparation was diluted to a protein concentration of 0.3 mg/ml, as determined by the Bradford method (2), and dialyzed against 2 liters of a solution containing 6 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M Tris (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyldimethyl)-1-ammonio]-propanesulfanate (CHAPS) overnight. Further dialysis was carried out with buffered solutions containing 4 M urea and then 2 M urea. Protein aggregates formed in this solution, and the precipitated protein was dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4).

Production of polyclonal antibodies against recombinant PtlC.

Granular material containing His-tagged PtlC was mixed 1:1 (vol/vol) with a 0.65% solution of Alhydrogel (aluminum hydroxide; Superfos a/s, Vedbaek, Denmark) to give a final protein concentration of 125 μg/ml. Five female BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.4 ml of the protein-adjuvant solution (50 μg of protein) per mouse. Booster immunizations were given 2 and 4 weeks after the initial injection. After the second booster immunization, blood was collected from the periorbital artery of each mouse. The serum was collected by centrifugation and stored at −80°C.

Preparation of cell extracts and cellular fractionation.

B. bronchiseptica strains were grown on BG plates and resuspended in PBS to give an A550 of 2. B. pertussis strains were grown to an A550 of 1.1 to 1.2 in 40 ml of Stainer-Scholte medium. In certain cases, cells were modulated for Bvg-regulated expression of ptx and ptl genes by growth in the presence of 20 mM MgSO4 and 5 mM nicotinic acid. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g and resuspended in 25 ml of PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Cells were broken by passage through a French pressure cell at 14,000 lb/in2. Samples of the lysates (6 ml of B. bronchiseptica lysate and 25 ml of B. pertussis lysate) were subjected to centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min. A 0.2-ml (B. bronchiseptica) or a 0.4-ml (B. pertussis) sample was taken from the cleared lysate, which represented total cellular protein, and was precipitated with an equal volume of 20% trichloroacetic acid. The resulting protein pellet was resuspended in 0.1 ml of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer. Total membranes were pelleted from the cleared lysate by ultracentrifugation with a 60 Ti rotor at 144,000 × g for 1 h. Proteins in the soluble periplasmic/cytoplasmic fractions were precipitated from 0.2 ml (B. bronchiseptica) or 0.4 ml (B. pertussis) of the supernatant and resuspended in 0.1 ml of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. The B. bronchiseptica membrane pellet was resuspended in PBS (5 ml); a 0.2-ml sample of this preparation was precipitated with an equal volume of 20% trichloroacetic acid, and the resulting protein pellet was suspended in 0.1 ml of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. The B. pertussis membrane pellet was suspended in 0.7 ml of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples of whole-cell extracts, cytoplasmic/periplasmic fractions, and membrane fractions (20 μl of B. bronchiseptica cell fractions and 25 μl of B. pertussis cell fractions) were then subjected to SDS-PAGE. It should be noted that samples of the three types of cell fractions of B. bronchiseptica (whole-cell extract, cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction, and membrane fraction) were derived from approximately equal numbers of cells. However, the B. pertussis membrane fraction was derived from 10 times more cells than was either the B. pertussis whole-cell extract fraction or the cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction.

Immunoblot analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE according to the procedure of Laemmli (20). Immunoblot analyses were performed essentially according to the protocol of Burnette (4). Antiserum raised against His-tagged PtlC was used at a dilution of 1:500 in PBS (pH 7.4) with 0.05% Tween 20. Immunoreactive bands were visualized on nitrocellulose sheets by adding the color substrates 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-1-phosphate (Promega) and nitroblue tetrazolium (Promega) in PBS–0.05% Tween 20.

Determination of biologically active PT.

Bordetella strains were grown on BG agar (Quality Biological) for a period of 48 to 72 h. Cell suspensions were made from these cultures by inoculating Stainer-Scholte medium (40 ml) to an A550 of 0.07. The strains were grown (shaking culture) at 37°C. Density measurements (A550) and viable cell counts (CFU) were determined at various times, and samples were taken for quantification of biologically active PT.

The presence of biologically active PT in cultures of B. pertussis was determined by using the CHO cell bioassay system (12). Bacterial cells from culture samples were collected by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was sterilized by filtration through Millex-GV filters (0.22-μm pore size; Millipore).

Filtered samples and a control preparation of PT (20 ng/ml) were serially diluted (twofold) in 96-well microtiter plates. CHO cells were added, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Cells that showed a clustered morphology were scored as positive.

RESULTS

Detection of PtlC in Bordetella spp.

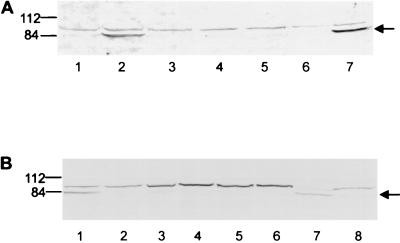

Our first objective was to identify and localize PtlC within Bordetella spp. Using our polyclonal antiserum against recombinant PtlC in immunoblot analysis, we detected an 85-kDa protein species in whole-cell extracts of B. bronchiseptica Bb55(pSZH5) (Fig. 3A). While B. bronchiseptica normally does not produce PT or Ptl, this strain was engineered to produce high levels of both proteins, in a Bvg-regulated manner, by introducing plasmid pSZH5, which contains the entire ptx-ptl operon of B. pertussis (11). As shown in Fig. 3A, the 85-kDa protein was detected neither in extracts from the parent strain nor in extracts from modulated Bb55(pSZH5) which was exposed to MgSO4 and nicotinic acid to inhibit expression of Bvg-regulated virulence factors (13, 19, 33). Also seen in all lanes of this immunoblot is a species that migrates as a 90-kDa protein. Since this band was observed in all lanes, including those representing whole-cell extracts of Bb55 and whole-cell extracts of modulated Bb55(pSZH5) that should not produce PtlC, this band likely represents a B. bronchiseptica protein that cross-reacts with the antibody preparation. Separation of Bb55(pSZH5) cells into soluble and particulate (total membrane) fractions demonstrated that PtlC localizes to the particulate fraction in this strain. We also visualized PtlC in B. pertussis BP536 (Fig. 3B). Since PtlC is produced in much smaller quantities in this strain than in the engineered B. bronchiseptica strain, it was difficult to visualize PtlC in the absence of steps used for partial purification and concentration. However, PtlC was apparent in the total membrane fraction of BP536.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of cell fractions of Bordetella spp. (A) Detection of PtlC in cell fractions of B. bronchiseptica. Lane 1, Bb55 whole-cell extract; lane 2, Bb55(pSZH5) whole-cell extract; lane 3, modulated Bb55(pSZH5) whole-cell extract; lane 4, modulated Bb55(pSZH5) cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction; lane 5, Bb55(pSZH5) cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction; lane 6, modulated Bb55(pSZH5) membrane fraction; lane 7, Bb55(pSZH5) membrane fraction. (B) Detection of PtlC in cell fractions of B. pertussis. Lane 1, Bb55(pSZH5) whole-cell extract; lane 2, modulated Bb55(pSZH5) whole-cell extract; lane 3, BP536 whole-cell extract; lane 4, modulated BP536 whole-cell extract; lane 5, BP536 cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction; lane 6, modulated BP536 cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction; lane 7, BP536 membrane fraction; lane 8, modulated BP536 membrane fraction. Positions of molecular weight markers are indicated at the left in kilodaltons. Arrows indicate protein bands corresponding to PtlC.

Effect of the ptlC deletion mutation on secretion of PT from B. pertussis.

A 540-bp in-frame deletion was made within the coding sequence of ptlC between coordinates 5198 and 5738 (see Materials and Methods for details), and the mutant was given the strain designation BP536ΔptlC. To verify the deletion within the chromosome of BP536ΔptlC, we performed PCR analysis; the results confirmed that the precise 540-bp deletion was present in the chromosome (data not shown). Assessments of the expression of ptlC in the mutant by immunoblot analysis revealed no detectable PtlC in cell fractions from strain BP536ΔptlC (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of the expression of genes downstream of ptlC confirmed that the ptlC deletion had no effect on the production and/or stability of PtlI, PtlE, PtlF, or PtlG (data not shown).

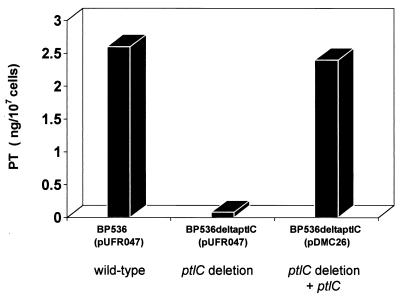

As shown in Fig. 4, the strain containing the ΔptlC mutation secreted much lower levels of PT than did the parent strain. The mutation was complemented in trans by introduction of plasmid pDMC26, which carries a wild-type copy of ptlC and no other portion of the ptl locus. Introduction of the complementing plasmid into the deletion mutant restored secretion to wild-type levels.

FIG. 4.

Secretion of biologically active PT by B. pertussis lacking PtlC. Culture supernatants from strains grown for 35 h to approximately 2 × 109 cells/ml as described in Materials and Methods were prepared. The amounts of biologically active PT found in the culture supernatants of the indicated strains were determined by assessing the ability of serial dilutions of culture supernatants to induce the clustering of CHO cells compared to a purified PT standard of known concentration.

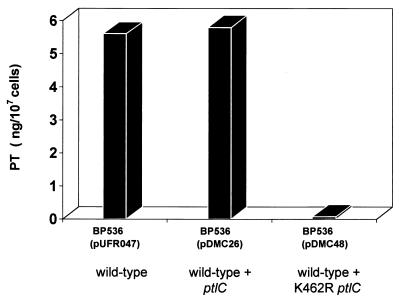

Effect of alteration of the putative NTP-binding region of PtlC.

To determine whether the putative NTP-binding region of PtlC plays a role in the transport process, we used site-specific mutagenesis to specifically alter ptlC such that the encoded Lys462 located in the Walker box A region of the protein would be changed to an Arg residue (Fig. 2). We introduced a plasmid (pDMC48) containing full-length ptlC with that specific mutation into a wild-type strain of B. pertussis (BP536). We then examined the ability of the wild-type strain harboring this plasmid to secrete PT. As shown in Fig. 5, introduction of control plasmids containing either no ptlC or a wild-type copy of ptlC did not affect secretion of PT. In striking contrast, introduction of the plasmid containing the mutated ptlC into BP536 resulted in drastically reduced secretion of PT. Since BP536 contains a wild-type copy of ptlC and normally secretes functional PT, the ptlCK462R mutant exhibits a dominant negative phenotype.

FIG. 5.

Secretion of biologically active PT by B. pertussis harboring plasmids containing mutant ptlC. Culture supernatants from strains grown for 36 h to approximately 5 × 109 cells/ml as described in Materials and Methods were prepared. The amounts of biologically active PT found in the culture supernatants of the indicated strains were determined by assessing the ability of serial dilutions of culture supernatants to induce the clustering of CHO cells compared to a purified PT standard of known concentration.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the role that PtlC plays in the secretion of PT. The apparent molecular weight of 85,000 for PtlC that we obtained by SDS-PAGE correlates well with its predicted molecular weight of 92,637. We found that PtlC is localized to the membrane of B. bronchiseptica Bb55(pSZH5), a strain that expresses a functional Ptl secretion system (11). A more precise localization within the bacterial envelope (i.e., inner versus outer membrane) is technically difficult since methods such as isopycnic centrifugation do not separate Bordetella membranes into distinguishable fractions corresponding to inner and outer membranes (8). Each of the other Ptl proteins that have been examined (PtlI, PtlE, PtlF, and PtlG) have also been localized to the membrane fraction of the cell (9, 14), consistent with the idea that these proteins, together with PtlC, may be part of a secretion apparatus that facilitates transport of PT across at least the outer membrane of B. pertussis.

We found that PtlC is a critical component of the PT secretion system since an in-frame deletion mutant of ptlC exhibited greatly impaired secretion of PT. The fact that this mutation could be complemented by introduction of a plasmid containing a wild-type copy of ptlC confirms that this defect was due to a mutation in ptlC rather than to some polar effect of the mutation.

We examined the importance of the putative nucleotide-binding motif of ptlC by specifically altering the region of ptlC that encodes a Walker box A motif. Alteration of Lys462→Arg had dramatic effects on the transport process. Introduction of a plasmid containing this mutation into a wild-type strain of B. pertussis that normally secretes PT drastically reduced the amount of PT found in the culture supernatant of the strain. The finding of a dominant negative phenotype for this mutation suggests that the altered protein can interfere with the action of the wild-type protein and reveals two important characteristics of PtlC. First, since the mutation is in the putative nucleotide-binding region of PtlC, our results suggest that this region is critical for PtlC action and support the idea that nucleotide binding is an important aspect of PtlC function. Additional work needs to be done to determine whether PtlC functions as an ATPase that can provide the energy for the transport process, whether this protein acts as a kinase to signal the opening of a gate or channel, or whether PtlC works with nucleotides in some other way to facilitate the transport of PT across bacterial membrane barriers. The second characteristic revealed by the dominant negative phenotype is that PtlC apparently interacts with some other component of the secretion system, possibly another molecule of PtlC, another Ptl protein, or PT itself. Very little is known about the architecture of the PT secretion apparatus. This finding provides important information in that we now know that PtlC interacts with itself or other proteins. Further investigations should be initiated to determine the identity of those proteins.

The predicted amino acid sequence of PtlC bears resemblance to sequences of proteins produced by all known members of type IV secretion systems, including VirB4 of A. tumefaciens as well as TraB and TrwK of IncN and IncW plasmids, respectively (15, 23, 34). VirB4 is part of the transport system involved in the export of T-DNA from A. tumefaciens (37), whereas the Tra and Trw systems play a role in conjugal DNA transfer. Perhaps the best studied of these proteins is VirB4, which, like PtlC, possesses a conserved NTP-binding motif that is essential for protein function (1, 10). Recombinant VirB4 produced in E. coli exhibits some ATPase activity (24), although the role of this activity in the transport process remains to be elucidated.

Interestingly, our work indicates that the parallels between PtlC and VirB4 are striking despite the notable differences between the two systems. The Ptl system, which consists of nine proteins, is believed to facilitate the transport of an assembled oligomeric toxin across the outer membrane of B. pertussis. This process is thought to occur in two steps. The first step appears to involve the transport of individual PT subunit polypeptide chains across the inner membrane of the bacterium via a Sec-like pathway, and the second step involves the transport of the assembled holotoxin across the outer membrane via the Ptl system (22, 32). In contrast, the VirB system, which consists of 11 VirB proteins, is believed to transport a large piece of single-stranded DNA of approximately 20 kb (36), which may or may not be coated with protein along its entire length, across both the inner and outer membranes of A. tumefaciens (6). This transport process likely occurs in a single-step process. By understanding the similarities of these systems as well as the differences, we will be better able to eventually dissect the steps involved in these complex transport mechanisms.

In summary, we have localized PtlC to the membrane of Bordetella and shown that it plays a critical role in the transport process. Moreover, PtlC is likely a nucleotide-binding protein that interacts with other members of the secretion system to facilitate transport of PT across the bacterial membrane.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger B R, Christie P J. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB4 gene product is an essential virulence protein requiring an intact nucleoside triphosphate-binding domain. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1723–1734. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1723-1734.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan M J, David J L, Kenimer J G, Manclark C R. Lectin-like binding of pertussis toxin to a 165-kilodalton Chinese hamster cell glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4895–4899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnette W N. “Western blotting”: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns D L. Transport of pertussis toxin across bacterial and eukaryotic membranes. In: Rothman S, editor. Membrane transport proteins. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press; 1995. pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christie P J. Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-complex transport apparatus: a paradigm for a new family of multifunctional transporters in eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3085–3094. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3085-3094.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFeyter R, Yang Y, Gabriel D W. Gene-for-genes interactions between cotton R genes and Xanthomonas campestris pv. malvacearum avr genes. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:225–237. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-6-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezzel J W, Dobrogosz W J, Kloos W E, Manclark C R. Phase shift markers in Bordetella: alterations in envelope proteins. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:562–569. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farizo K M, Cafarella T G, Burns D L. Evidence for a ninth gene, ptlI, in the locus encoding the pertussis toxin secretion system of Bordetella pertussis and formation of a PtlI-PtlF complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31643–31649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullner K J, Stephens K M, Nester E W. An essential virulence protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, VirB4, requires an intact mononucleotide binding domain to function in transfer of T-DNA. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:704–715. doi: 10.1007/BF00297277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausman S Z, Cherry J D, Heininger U, Wirsing von Konig C H, Burns D L. Analysis of proteins encoded by the ptx and ptl genes of Bordetella bronchiseptica and Bordetella parapertussis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4020–4026. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4020-4026.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewlett E L, Sauer K T, Myers G A, Cowell J L, Guerrant R L. Induction of a novel morphological response in Chinese hamster ovary cells by pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1983;40:1198–1203. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.3.1198-1203.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Idigbe E O, Parton R, Wardlaw A C. Rapidity of antigenic modulation of Bordetella pertussis in modified Hornibrook medium. J Med Microbiol. 1981;14:409–418. doi: 10.1099/00222615-14-4-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson F D, Burns D L. Detection and subcellular localization of three Ptl proteins involved in the secretion of pertussis toxin from Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5350–5356. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5350-5356.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kado C I. Promiscuous DNA transfer system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: role of the virB operon in sex pilus assembly and synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katada T, Tamura M, Ui M. The A protomer of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, as an active peptide catalyzing ADP-ribosylation of a membrane protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:290–298. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katada T, Ui M. Direct modification of the membrane adenylate cyclase system by islet-activating protein due to ADP-ribosylation of a membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3129–3133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotob S I, Hausman S Z, Burns D L. Localization of the promoter for the ptl genes of Bordetella pertussis, which encode proteins essential for secretion of pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3227–3230. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3227-3230.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacey B W. Antigenic modulation of Bordetella pertussis. J Hyg. 1960;58:57–93. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400038134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicosia A, Perugini M, Franzini C, Casagli M C, Borri M G, Antoni G, Almoni M, Neri P, Ratti G, Rappuoli R. Cloning and sequencing of the pertussis toxin genes: operon structure and gene duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4631–4635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pizza M, Bugnoli M, Manetti R, Covacci A, Rappuoli R. The subunit S1 is important for pertussis toxin secretion. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17759–17763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohlman R F, Genetti H D, Winans S C. Common ancestry between IncN conjugal transfer genes and macromolecular export systems of plant and animal pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:655–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirasu K, Koukolikova-Nicola Z, Hohn B, Kado C I. An inner-membrane-associated virulence protein essential for T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to plants exhibits ATPase activity and similarities to conjugative transfer genes. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–790. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stibitz S. Use of conditionally counterselectable suicide vectors for allelic exchange. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:458–465. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stibitz S, Yang M-S. Subcellular localization and immunochemical detection of proteins encoded by the vir locus of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4288–4296. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4288-4296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura M, Nogimori K, Murai S, Yajima M, Ito K, Katada T, Ui M, Ishii S. Subunit structure of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, in conformity with the A-B model. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5516–5522. doi: 10.1021/bi00265a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura M, Nogimori K, Yajima M, Ase K, Ui M. A role of the B oligomer moiety of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, in development of the biological effects on intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6756–6761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker M E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the alpha and beta subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss A A, Hewlett E L, Myers G A, Falkow S. Pertussis toxin and extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase as virulence factors in Bordetella pertussis. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:219–222. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss A A, Johnson F D, Burns D L. Molecular characterization of an operon required for pertussis toxin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2970–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss A A, Melton A R, Walker K E, Andraos-Selim C, Meidl J J. Use of the promoter fusion transposon Tn5 lac to identify mutations in Bordetella pertussis vir-regulated genes. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2674–2682. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2674-2682.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winans S C, Burns D L, Christie P J. Adaptation of a conjugal transfer system for the export of pathogenic macromolecules. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:64–68. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81513-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witvliet M H, Burns D L, Brennan M J, Poolman J T, Manclark C R. Binding of pertussis toxin to eucaryotic cells and glycoproteins. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3324–3330. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3324-3330.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambryski P. Basic processes underlying Agrobacterium-mediated DNA transfer to plant cells. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zambryski P. Chronicles from the Agrobacterium-plant cell DNA transfer story. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:465–490. [Google Scholar]