Abstract

The highest density of microbes resides in human gastrointestinal tract, known as “Gut microbiome”. Of note, the members of the genus Lactobacillus that belong to phyla Firmicutes are the most important probiotic bacteria of the gut microbiome. These gut-residing Lactobacillus species not only communicate with each other but also with the gut epithelial lining to balance the gut barrier integrity, mucosal barrier defence and ameliorate the host immune responses. The human body suffers from several inflammatory diseases affecting the gut, lungs, heart, bone or neural tissues. Mounting evidence supports the significant role of Lactobacillus spp. and their components (such as metabolites, peptidoglycans, and/or surface proteins) in modulatingimmune responses, primarily through exchange of immunological signals between gastrointestinal tract and distant organs. This bidirectional crosstalk which is mediated by Lactobacillus spp. promotes anti-inflammatory response, thereby supporting the improvement of symptoms pertaining to asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), neuroinflammatory diseases (such as multiple sclerosis, alzheimer’s disease, parkinson’s disease), cardiovascular diseases, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and chronic infections in patients. The metabolic disorders, obesity and diabetes are characterized by a low-grade inflammation. Genus Lactobacillus alleviates metabolic disorders by regulating the oxidative stress response and inflammatory pathways. Osteoporosis is also associated with bone inflammation and resorption. The Lactobacillus spp. and their metabolites act as powerful immune cell controllers and exhibit a regulatory role in bone resorption and formation, supporting bone health. Thus, this review demonstrated the mechanisms and summarized the evidence of the benefit of Lactobacillus spp. in alleviating inflammatory diseases pertaining to different organs from animal and clinical trials. The present narrative review explores in detail the complex interactions between the gut-dwelling Lactobacillus spp. and the immune components in distant organs to promote host’s health.

Keywords: lactobacillus, inflammation, gut microbiome, probiotics, gut-lung axis, gutbrain axis, gut-heart axis, gut-bone axis

1 Introduction

The human body is inhabited by trillions of dynamic and diverse microbial communities that potentially regulate the physiology of the host, popularly known as the “Microbiome” (Malard et al., 2021). The human microbiome performs imperative biological functions such as immune system homeostasis, regulation of host metabolism, prevention of pathogens invasion and improvement of the epithelial barrier function (Malard et al., 2021). The highest density of microbes resides in human gastrointestinal tract, known as the “Gut microbiome” (Dwivedi et al., 2021. The predominant bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract are Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, followed by Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria (Rinninella et al., 2019). Of note, the members of the genus Lactobacillus that belong to phyla Firmicutes are the most important probiotic bacteria of the gut microbiome. These gut-residing Lactobacillus species not only communicate with each other but also with the gut epithelial lining to balance the gut barrier integrity, mucosal barrier defence and ameliorate the host immune responses (Martín et al., 2019). In addition, Lactobacillus species exhibit microbial roles by competitively excluding opportunistic pathogens from inhabiting functional niches in the gut, restraining attachment of pathogens on epithelium as well as directly killing pathogens by producing lactic acid, acetic acid, propionic acid, bacteriocins and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Dempsey and Corr, 2022). Besides microbial roles, commensal Lactobacillus species regulate both adaptive and innate immune responses by inducing T cells, Natural Killer (NK) cells, macrophages differentiation, cytokine-production and stimulating toll-like receptors (TLRs). They also manifest immunomodulatory effect by increasing immunoglobulin-A (IgA) producing B cells expression in Peyer’s patches in the lamina propria, where they block pathogens adhesion to the intestinal epithelium (Cristofori et al., 2021). The human body suffers from several inflammatory diseases affecting the gut, lungs or neural tissues. Mounting evidence supports the significant role of Lactobacillus species in suppressing inflammatory responses by downregulating the expression of T-helper17 (Th17) inflammatory cells and their signature cytokines IL-17F, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Numerous works of literature is available that highlights the beneficial role of these commensals in ameliorating symptoms of cardiovascular-related diseases (CVD), osteoporosis, metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity (Zaiss et al., 2019; Archer et al., 2021; Companys et al., 2021). The genus is also reported to regulate cholesterol metabolism as well as gut-derived metabolites production such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and bile acids (BA). Osteoporosis is associated with bone inflammation and resorption (Britton et al., 2014). The Lactobacillus spp. and their metabolites also act as powerful immune cell controllers and exhibit a regulatory role in bone resorption and formation, supporting bone health. (Zaiss et al., 2019).

In view of these considerations, the significant role of Lactobacillus spp. in the alleviation and treatment of human diseases presents attractive therapeutic potential. Thus, the aim of this review is to analyze the current research works implicating the potent use of these microbes and their components in mediating immune responses that affect host health. PubMed was used to search for all of the studies published over the last 15 years using the key words “lactobacillus” or “Gut microbiota” and “inflammation”. More than 550 articles were found, and only those published in English and providing data on aspects related to human diseases were included in the evaluation.

2 Genus Lactobacillus as a member of the gut microbiome

Nowadays, the gut microbiome is a prominent area of scientific research as it holds imperative role in human health and pathology. Of note, the members of genus Lactobacillus are the most important probiotic bacteria. Lactobacillus spp. act by regulation of luminal pH, enhancement of barrier function by increasing mucus production, secretion of antimicrobial peptides, and by changing the gut microbial composition (Dempsey and Corr, 2022). Their cogent functional attributes include improving digestion, maintenance of gastrointestinal-barrier integrity, competition to opportunistic pathogens, neuromodulation, participation in maturation of the immune system in early life and preservation of immune homeostasis during entire life, production of metabolites, vitamins and other components (Dempsey and Corr, 2022).

Detailed taxonomic profiling reveals that the genus Lactobacillus belongs to phylum Firmicutes, class Bacilli, order Lactobacillales and family Lactobacillaceae. They are Gram-positive, catalase-negative, non-spore forming, obligate saccharolytic rods or coccobacilli with low GC (guanine and cytosine) content of the genome (Zheng et al., 2020). Members of the genus Lactobacillus are well-adapted to the hostile environment persisting in oral, gastrointestinal and vaginal tract. In healthy adult’s feces, the concentration of different lactobacilli species accounts for upto 105–108 CFU/g. Among human gut-dwelling microbial species, Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus ultunensis, Ligilactobacillus ruminis, Limosilactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus kalixensis, Lactocaseibacillus casei, Limosilactobacillus gastricus, Limosilactobacillus antri, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Ligilactobacillus salivarius, Limosilactobacillus fermentum, etc. are found to be permanent and form essential part (Zheng et al., 2020). Probiotic supplementation with lactobacilli species assists in altering the gut microbiota composition, thereby reducing dysbiosis and maintaining the microbial balance with a greater abundance of useful bacteria. A probiotic formulation comprising of L. rhamnosus GG, L. acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, and L. delbrueckii when given orally tends to stimulate the other gut microbial species such as Prevotella and Oscillibacter that exhibited anti-inflammatory activity in rats (Zeng et al., 2021).

3 Genus Lactobacillus and human health

As probiotics, lactobacilli play significant roles through various GM-derived metabolites andpossess several health ameliorating attributes common among them are alleviation of chronic diseases, immune system stimulation, pathogen protection, and nutritional physiology.

3.1 Gastrointestinal barrier integrity

When the gut barrier becomes dysfunctional, it leads to several inflammatory conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and obesity. Gut-dwelling Lactobacillus spp. were found to restore gastrointestinal barrier function directly or indirectlyin mice inflammation models (Martín et al., 2019). Indirect mechanisms through which they interact with the immune system involve modulating gut microbiota, regulating intestinal epithelial barrier integrity, viscoelastic mucin layer properties, antagonistic peptides/factors production and competitive exclusion of pathogens (Cristofori et al., 2021).

3.1.1 Gut epithelial barrier

The gut epithelial barrier separates the internal intestinal milieu from the luminal environment, thereby ascertaining the permeability of nutrients and other molecules as well as exerting a protective role by arresting the entry of microbes and toxic compounds. Studies have reported that commensal Lactobacilli spp. maintain gut barrier integrity which depends upon the multi-protein complexes such as tight junctions, gap junctions, adherens and desmosomes (Kocot et al., 2022). These complexes are primarily made up of transmembrane proteins namely, claudin, occludin, and junctional adhesion molecules which interact with adjacent cells via zonula occludens (ZO) and actin fibers. In case of chronic inflammatory diseases or enteric infections, the intestinal barrier integrity is disrupted. Studies have reported increased expression of ZO-1, occludin and claudin proteins by L. rhamnosus CNCM-I in enterohemorrhagic E. coli O 157:H7 infected Caco-2 cell lines (Laval et al., 2015). Similarly, L. casei DN-114 001 up-regulates ZO-1 protein expression via activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 in Caco-2 cells. The TLR-2 binding leads to Protein kinase C (PKC) activation which causes tight junction proteins translocation, thereby enhancing gut barrier function (Kocot et al., 2022).

3.1.2 Mucus production

Gut epithelium is covered by high molecular weight glycoproteins, mainly mucins which are produced by goblet cells (Wuet al., 2020). The viscoelastic mucin layer provides protection against digestive enzymes, supports food passage and prevents translocation of microbes across lamina propria, thus imparting gut homeostasis (Wu et al., 2020). Studies have reported certain Lactobacillus strains to regulate mucin gene expression thereby changing the mucus layer attributes and indirectly affecting the gut immune responses. Of note, L. rhamnosus CNCM I-3690 regulated Muc2 and Muc3 gene expression in mucus-producing goblet cells in mice inflammation model, thus preventing gut barrier dysfunction and inflammation (Martín et al., 2019).

3.1.3 Anti-microbial peptides/factors

The vital function of lactobacilli strains lies in their ability to prevent pathogenic growth by synergistically inhibiting enteropathogens and stimulating the host immune system. The lactobacilli that showed in vitro antagonistic activity against periodontal and enteric pathogens are L. oris, L. paracasei, L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. salivarius, L. plantarum, L. delbrueckii, L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, and L. fermentum, thereby improving gut homeostasis (NĘdzi-GÓra et al., 2020; Dempsey and Corr, 2022). Among the known factors that contribute to the antimicrobial ability of Lactobacillus spp. is their tendency to produce a wide range of metabolites such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide, SCFAs and bacteriocin that impede the growth of pathogens (Sulijaya et al., 2020). Organic acids, particularly lactic acid is a potent inhibiting factor as it creates acidic cytoplasmic pH as well as permeabilize the outer membrane of Gram-negative microorganisms (Sulijaya et al., 2020). For example, L. acidophilus 4,356 inhibited the growth of H. pylori by abundantly producing lactic acid (Modiri et al., 2021). Nitric oxide (NO) is another inhibitory microbial metabolite. Probiotic lactobacilli can effectively elevate NO synthesis or can stimulate host macrophages for NO production. For example, L. fermentum LF1 produces NO via the NO synthase pathway via oxidation of l-arginine to l-citrulline (Dempsey and Corr, 2022). Some may even ribosomally synthesize short peptides known as bacteriocins which possess broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria. For example, L. plantarum LPL-1 produced 4,347 Da plantaricin LPL-1 (Wang et al., 2018) while curvacin A is from L. curvatus (Ahsan et al., 2022). In the genome of several other lactobacilli species, genes encoding for pediocin and plantaricin are found (Ahsan et al., 2022). The hydrogen peroxide producing lactobacilli also induce growth stagnation in pathogens. L. johnsonii UBLJ01 genome analysis revealed NADH oxidase, lactate oxidase and pyruvate oxidase genes involved in H2O2 synthesis while in vitro test reported their strong antagonistic potential (Ahire et al., 2021). In addition to the synthesis of inhibitory substances, Lactobacilli spp. can decrease the toxicity by degradation of microbial toxins, particularly by impeding toxin expression or by binding to the pathogen’s outer membrane. For example, L. rhamnosus JB3 reduced the infection of H. pylori in the gut by either forming lipid rafts or downregulating the expression of virulent genes (Do et al., 2021).

Recently, literature is available that highlights the ability of lactobacillus spp. in detoxifying mycotoxins that are known to cause carcinogenesis and immune-suppression in the host. Of note, L. coryniformis BCH-4 and L. plantarum MiLAB 393 produced fungicide compounds cyclo (L-Leucyl-L-Prolyl) and 3-phenyllactic acid cyclo (L-Phe-L-Pro)respectively which significantly reduced the viability of aspergillus and candida species (Ström et al., 2002; Salman et al., 2022). Additionally, Sunmola et al., 2019 reported the anti-viral activity of L. plantarum and L. amylovorus AA099 against enteroviruses such as echovirus whose site of primary replication is in the gastrointestinal tract. Similarly, Kawahara et al., 2022 reported the antiviral activity of S-layer proteins from L. crispatus KT-11 strains by suppressing the amplification of rotavirus protein 6 (VP6) expression in human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells. Also, Mousavi et al., 2018 demonstrated that L. crispatus microcolonies formation on the cell surface tends to block the entry of herpes simplex virus-2 particles, thus help in inhibiting the primary infection step. The rotaviruses are among the ones that bring about severe recurrent diarrhea in infants while herpes simplex virus I cause oral herpes in adults (Kawahara et al., 2022). The understanding of the exact mechanisms is still limited but a few of them include the synthesis of sialic acid and bacteriocins, immune stimulation and obstruction in the binding of viruses (Mousavi et al., 2018; Kawahara et al., 2022).

3.2 Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders

Inflammations are physiological responses to tissue injury and/or infections, elicited by pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by monocytes, B cells, T cells, dendritic cells (DC), natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophages. Substantial evidence from colitis-induced murine model studies claims the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory action of Lactobacillus spp. in gut inflammation (Cristofori et al., 2021). These effects largely depend upon cytokine production and immune cells proliferation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8 play important role in the recruitment of immune cells during an inflammatory response. Notably, L. acidophilus can suppress IL-8 production and enhance Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2) expression through the regulation of TLR-2 mediated mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathways and Nuclear Factor kappa-light chain-activated B cells (NF-кB) in inflammatory epithelial cells of the intestine (Li et al., 2021). Likewise, several strains of lactobacillus (such as L. acidophilus CCFM137, L. fermentum CCFM381, L. plantarum CCFM634 and CCFM734) also displayed anti-inflammatory potential by upregulating the expression of TLR-2/TLR-6 heterodimer receptor which act as an inflammatory intracellular signalling network (Ren et al., 2016). Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is systemic disorder that significantly perturbs the intestinal epithelial layer of the gastrointestinal tract causing four pathological conditions, Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), microscopic colitis and pouchitis. Compare et al., 2017 reported L. casei DG lower pro-inflammatory IL-6, IL-8, TLR-4 and IL-1a and increase IL-10 cytokinelevels in the colonic mucosa of post-infectious IBD subjects. Additionally, L. casei and L. bulgaricus significantly lowered the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in colonic mucosal samples from CD patients (De Conno et al., 2022). The Treg cells are another immunological player involved in immune-modulation and tolerance. L. casei M2S01 displayed anti-inflammatory action in diseases, such as CD and microscopic colitis, by enhancing Treg cell activation, IL-10 levels and restoring gut microbial flora (Liu Y et al., 2021). Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is another serious gastrointestinal inflammatory condition affecting particularly premature newborns. An ex-vivo study carried out on human intestinal cells from the ileus of NEC infants when treated with L. rhamnosus HN001 displayed reduced NF-kB inflammatory pathway activation through inhibition of TLR-4 (Good et al., 2014). Furthermore, commensal lactobacillus spp. activates mucosal immunity by increasing IgA antibodies, resulting in the immobilization and agglutination of pathogens. The dose-dependent consumption of lactobacillus particularly, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, L. casei, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, L. rhamnosus accrued the number of IgA-producing immune cells connected with mucosa lamina propria as well as stimulates the immunoglobin receptors present on epithelial cells of the intestine (Chen et al., 2022).

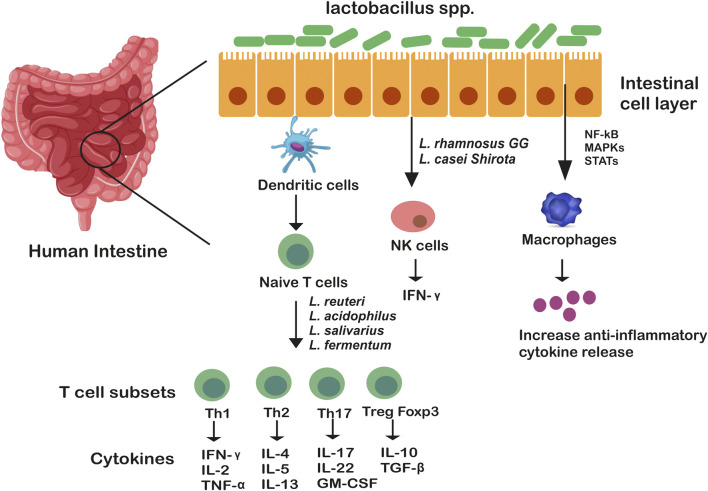

Adhering to the host ileal tract, lactobacilli modulate another important aspect, apoptosis and cancer, both of which are associated with mucositis. For example, L. rhamnosus GG actively induces antiapoptoticAkt/protein kinase B and inhibits pro-apoptotic factors via p36 MAPK pathway while cell wall components of an array of lactobacilli such as lipoteichoic acid tends to stimulate NO synthase, thereby initiating a cascade of events that bring about pathogen-infected cell death (Banna et al., 2017). Important immune events include activation of macrophages through TNF-α cytokine production and NO-mediated upregulation of two surface phagocytosis receptors (FcγRIII and TLR-2). Sun et al., 2020 reported LPS-induced inflammatory response in Caco-2 cells owing to upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines genes (IL10, IL4, transforming growth factor-β3 (TGF–b3 and IFN-y)and downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL6, IL1B, IL8 and TNF-α) along with higher expression of TLR-2 and NOD-like receptor genes. Also, genome analysis unfolds the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway in Caco-2 cells by L. gasseri JM1. Another in vivo study demonstrated induction of innate and adaptive immune responses by L. acidophilus NCFB 1748 and L. paracasei DC412 on BALB/c inbred mice and Fisher-344 inbred rats through polymorphonuclear (PMN) cell recruitment, TNF-α secretion and phagocytosis (Azad et al., 2018). Lactobacilli encode for certain motifs within their genome, such as unmethylated CpG motifs which are recognized by TLRs that are expressed particularly in B cells and macrophages (Xiao et al., 2022). The role of Lactobacillus spp. in modulating immune responses is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Genus Lactobacillus mediated immune modulation in the gut. Genus lactobacillus as whole bacteria or their components communicate through membrane receptors TLR-6 and TLR-2 which are expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells, stimulating T cell subsets differentiation. These T cells (Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg) are considered as the masters of inflammation. Lactobacillus spp. also exert their functions by altering intracellular pathways of immune cells (such as macrophages) through MAP kinases which either activate or suppress transcription factors, STAT, NF-kB, increasing anti-inflammatory cytokine release.

In recent research, studies involving immunomodulating role of lactobacillus spp. in pain management and treating allergic symptoms have gained momentum. To date, few researchers have demonstrated the prowess of Lactobacillus spp. in relieving inflammatory pain by regulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β as well as expression of COX II in the host intestinal epithelium (Santoni et al., 2021). Although the exact pathway and mechanisms involved in inflammatory pain relief are yet not investigated in detail. L. reuteri DSM17938 displayed antinociceptive activity causing relief in children with functional abdominal pain (Jadrešin et al., 2020). The probable mechanism involves the activation of submucosal immune cells that trigger sensitivity in nerve terminals and/or tight junctions. Another randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-centric study by Martoni et al., 2020, reported improvement in abdominal pain and IBS symptoms in adult subjects after the administration of B. lactis UABla-12and L. acidophilus DDS-1 for over 6 weeks. Maixentet al., 2020 also reported the efficacy of the cocktail of two L. acidophilus strains in relieving pain in IBD patients.

3.3 Respiratory inflammatory disorders (gut-lung axis)

Lactobacillus as whole bacteria or their components (such as peptidoglycans, metabolites and surface proteins) have shown to exert an immunomodulating role in treating patients with chronic respiratory disorders. The probable mechanisms by which Lactobacillus modulate lung immunity and promote respiratory health is via the “Gut-Lung axis” which is bidirectional (Du et al., 2022).

In the intestinal mucosa, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs, such as NLRs or TLRs) present on immune cells recognize Lactobacillus species or their components resulting in the activation of innate immune cells which tend to reach pulmonary tissues through lymphatic circulation (Stavropoulou et al., 2021; Du et al., 2022). To elucidate, oral administration of L. paracasei CNCM I-1518 caused innate lymphoid group 3 cells (ILC3s) to migrate from the gut to the lungs where ILC3 provides resistance to pneumonia (Gray et al., 2017). Moreover, L. rhamnosus GG and L. murinus oral supplementation promotes the migration of Treg cell to the lungs, thereby augmenting pulmonary inflammation (Zhang et al., 2018; Han et al., 2021). The Treg cells not only have the potent anti-inflammatory ability but are also found to block Th2 type immune response in the host. In addition to this, Lactobacillus interaction with gastric mucosa results in the secretion of cytokines by immune cells, which through circulation reach lung tissues where they alter the immune response. Kollinget al., 2018 reported oral intake of L. rhamnosus CRL1505 results in higher TNF-α, IFN-β, IFN-α, and IFN-ɣ cytokines levels in the lungs leading to a significant reduction in respiratory inflammations. Of note, certain lactobacillus strains secrete metabolites, particularly short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, butyrate that can regulate host pulmonary immune responses. SCFAs affect immune response in two ways; one is when unmetabolized SCFAs directly migrate to the lungs through circulation and enhance G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) activation or histone deacetylase inhibition (Koh et al., 2016). The other is where SCFAs migrate to bone marrow through circulation where they increase the differentiation of macrophage and dendritic progenitor cells (MDPs) and convert them into Ly6C–monocytes, these in turn reach the lungs and differentiate into anti-inflammatory alternatively activated macrophages (AAMs). These AAMs reduce neutrophiles recruitment and stimulate Treg cells to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), thus lower lung injury and inflammation (Anand and Mande, 2018; Du et al., 2022). Animal studies have reported higher butyrate production leads to an increase in Tregs cells and IL-10 production mediated by GPR109A receptor activation as well as restoration of IL-10 in pulmonary tissues by inhibiting histone deacetylase (Vieira et al., 2019). Spacova et al., 2020 showed that L. rhamnosus GR-1 significantly prevented the severity of airway inflammation and hyperactivity by modulating Th2-mediated immune responses as well as shifting gut microbiome composition in the allergic asthma model, supporting the existence of gut-lung axis. Likewise, Li et al., 2019 investigated the efficacy of six lactobacillus spp. (L. fermentum, L. salivarius, L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. reuteri and L. gasseri) on the gut microbiome and airway inflammation of house dust mite (HDM)-treated asthmatic mice models. Among these, strains of L. reuteri displayed improved airway inflammation with reduced total HDM-IgG1, IgE and Th2-associated pro-inflammatory cytokines with a shift in gut microbial flora. To summarize, members of Lactobacillus spp. or their metabolites have potent anti-inflammatory response, thereby supporting the alleviation of symptoms of asthma, respiratory tract infections and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in patients. The animal and clinical trials associated with Lactobacillus spp. in inflammatory disorders of various organ systems are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Animal and clinical studies of different Lactobacillus strains in alleviating inflammatory diseases pertaining to different organs.

| Lactobacillus | Strain | Diseases | Experimental model | Immunological response | Clinical outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. casei | Lbs2 | Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders | TNBS -induced colitis in mice | Increased Treg levels | Lower gastric inflammation | Thakur et al. (2016) |

| L. plantarum | CCFM634 | Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Stimulated TLR2/TLR6 heterodimer | lower gastric inflammation | Ren et al. (2016) |

| L. plantarum | CCFM734 | |||||

| L. fermentum | CCFM381 | |||||

| L. acidophilus | CCFM137 | |||||

| L. reuteri | LMG P-2748 | Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders | C. difficile induced colitis in mice | Increased IL-10 levels | lower gastric inflammation | Sagheddu et al. (2020) |

| L. fermentum | CECT5716 | Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Decreased IL-1b, IL-12 and TGF-β levels | lower gastric inflammation | Rodríguez-Nogales et al. (2017) |

| L. salivarius | CECT5713 | |||||

| L. rhamnosus | RC007 | Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders | TNBS- induced colitis in mice | Increases IL-10/TNF-α ratio | lower gastric inflammation | Dogi et al. (2016) |

| L. fermentum | CQPC04 | Gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Increases IL-10, decreases TNF-α, IFN-ɣ, IL-1b, IL-6, and IL 12 and Inhibited NF-kBp65, COX-2 | Lower inflammatory pain | Zhou et al. (2019) |

| L. rhamnosus | GG | Respiratory inflammatory disorders | Infant C57BL/6 mice or seven-week-old female BALB/c mice | Increased IL-10 levels | Improvement in survival rate and reduction in lung inflammation | Kumova et al. (2019) |

| L. plantarum | CIRM653 | Respiratory inflammatory disorders | 6-8-week-old C57/BL6J mice | The pulmonary inflammation response is reduced | Vareille-Delarbre et al. (2019) | |

| L. casei | CRL 431 | Respiratory inflammatory disorders | Adult 8-week-old Swiss albino mice and immune-deficient Swiss albino mice | Lung bacterial load is decreased | Lung inflammation is reduced, accelerated weight recovery | Zelaya et al. (2013) |

| L. fermentum | CJL-112 | Respiratory inflammatory disorders | Female, specific pathogen-free (SPF) BALB/c mice | Significant up-regulation of Th1 cytokine and IgA | Improvement in pulmonary inflammation | Yeo et al. (2014) |

| L. kunkeei | YB38 | |||||

| L. murinus | CNCM I-5314 | Respiratory inflammatory disorders | Six-eight-week-old female SPF C57BL/6 mice | Increases lung Th17 and RORγt+ Tregs cells | Reduction in pulmonary inflammation | Bernard-Raichon et al. (2021) |

| L. casei | CCFM419 | Diabetes | High fat and streptozotocin (HFD/STZ)-induced C57BL/6J mice | Decrease in TNF-α and IL-6, increase GLP-1 and SCFAs levels | Reduced type 2 diabetes, GM modulation | Wang et al. (2017) |

| L. paracasei | NL41 | Diabetes | Eighteen (HFD/STZ)-induced Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats | Decreases insulin resistance, and HbA1c, glucagon, and leptin levels, GM modulation | Zeng et al. (2019) | |

| L. acidophilus | KLDS1.1003 | Diabetes | High fat and streptozotocin (HFD/STZ)-induced C57BL/6J mice | Decrease in IL-8, TNF-α and IL-1β in liver and colon. Downregulated expression of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), fatty 41 acid synthase (FAS) and sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1c 42 (SREBP-1c), up-regulate the expression of protein kinase B (Akt) | Reduced inflammation in colon and liver associated with diabetes, reshape GM | Yan et al. (2019) |

| L. gasseri | LG2055 | Obesity | C57BL/6 mice | Upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes, CCL2 and CCR2. Reduction in hepatic lipogenic genes ACC1, FAS and SREBP1 | Decrease in body weight, epididymal fat tissue mass | Miyoshi et al. (2014) |

| L. brevis | OPK-3 | Obesity | Male C57BL/6 mice | Decrease in TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, serum TG levels | Decrease in body weight, epididymal fat tissue mass | Park et al. (2020) |

| L. fermentum | MTCC:5898 | Cardiovascular diseases | Male Wistar rats | Decrease in TNF-α and IL-6 | Decrease in coronary artery risk index, atherogenic index, hepatic lipids, lipid peroxidation, serum total cholesterol, LDL, triglycerides | Yadav et al. (2019) |

| L. brevis | BCRC 12310 | Cardiovascular diseases | Six -week-old SH rats | Decrease in the COX-1, COX-2, iNOS, and TNF-α levels | Anti-hypertensive effect by blocking LPS-induced NO production and | Chang et al. (2016) |

| L. fermentum | ME-3 | Cardiovascular diseases | Human subjects | Decrease in IL-6 | Decrease in serum total cholesterol, HDL LDL, triglyceride, oxLDL, hsCRP and HB1Ac levels | Kullisaar et al. (2016) |

| L. paracasei | FZU103 | Cardiovascular diseases | HFD-fed BALB/c mice | LXR/inflammatory axis of LPS-stimulated alveolar macrophages, shift in GM | Increase cholesterol metabolism, BAs homeostasis | Lv et al. (2021) |

| L.rhamnosus | GR-1 | Cardiovascular diseases | Eight-week-old ApoE−/− BALB/c mice | Up-regulated NF-κB signaling pathway | Decreased atherosclerotic lesion size, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation | Fang et al. (2019) |

| L. paracasei | DSM13434 | Bone Heath | Six-week-old C57BL/6N female mice | Decrease in TNF-α and IL-1β | Increase in OPG levels, alleviated ovariectomy-induced bone loss and resorption | Ohlsson et al. (2014) |

| L.reuteri | ATCC 6475 | Bone health | Eleven-week old male BALB/c mice | Upregulated Wnt10b signaling, and TNF-α levels | Alleviated glucocorticoid -induced bone loss, shift in GM with reduction in Clostridium | Schepper et al. (2019) |

| L. reuteri | ATCC 6475 | Bone health | Fourteen-week C57BL/6 male mice | Decrease in TNF-α levels, Wnt10b signalling suppression | Alleviated type-I diabetes-induced bone loss | Zhang et al. (2015) |

| L. reuteri | ATCC PTA 6475 | Bone health | Twelve- weeks BALB/c mice | Decrease in Osteoclast markers (Trap5 and RANKL), increase in CD4+ T cells | Alleviated ovariectomy-induced bone loss | Britton et al., 2014 |

| L. plantarum | C88 | Liver injury | Aflatoxin (AFB1) induced 6-week old male ICR mice | Decrease in IL-6, IL-8,IFN- ɣ, TNF-α. Downregulated NF-kB signaling pathway. Decreased levels of Bax and caspase-3, caspase-8 and elevated Bcl-2 levels in liver | Reduced inflammation and apoptosis in liver tissues | Huang et al. (2019) |

| L. plantarum | Gut-resident | Neuroinflammation | Eight-week adult C57BL/6 mice | Blocked TLR4, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP1 in brain regions | Mitigating neuroinflammation | Shukla et al. (2022) |

3.4 Neuroinflammatory and Neurodegenerative disorders (gut-brain axis)

The role of gut-resident Lactobacillus species in human brain development and functions has also been reported. The mechanism involves the exchange of neural, hormonal and immunological signals between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system (CNS), primarily known as the“Gut-Brainaxis”. This bidirectional communication is mediated by tryptophan precursors and microbial metabolites such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), histamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), glutamine, LPS, branched-chain amino acid (BCAAs), bile acids, SCFAs, and catecholamines which regulate potent pathways that are implicated in neuroglial cell function, neurogenesis, myelination, blood–brain barrier function and synaptic pruning (Suganya and Koo, 2020). Of note, human intestinal isolates, lactobacilli were able to produce GABA in the enteric nervous system (ENS). Studies also reported the modulation of the gut microbiota on supplementation with L. rhamnosus JB-1 activated the expression of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors thereby resulting in marked improvement in cognitive responses in mice via the vagus nerve (Breit et al., 2018). Several species of Lactobacillus have shown marked effects as neuromodulators and neurotransmitters (such as monoamines, serotonin, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor) (Suganya and Koo, 2020). The microbial metabolite, such as SCFAs produced primarily by lactobacilli in the gut directly affect brain neurological functions through vagal, endocrine, humoral and immune pathways by either entering circulation or crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB). SCFAs tend to activate Treg cells, endocrine cells and neuronal cells directly in order to increase regulatory cytokines level that maintains brain functions (Silva et al., 2020). LPS induces neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory disease through TLR stimulation, especially TLR4 in the microglial cells and astrocytes. Studies reported that LPS/TLR4 signaling on microglial cells affects the CNS, particularly by enhancing inflammatory cytokines levels in the gut or CNS of Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) patients. Liu et al., 2019 reported oral supplementation of L. plantarum PS128 for 1 month drastically ameliorated ASD-related symptoms as compared with the placebo group in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.

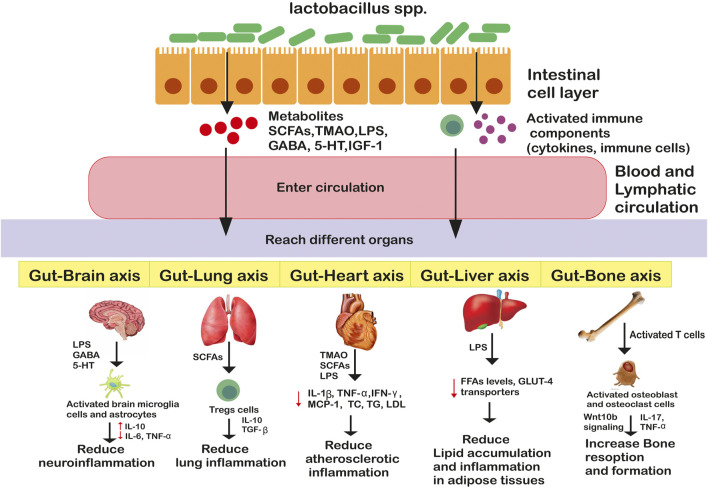

Existing evidence supports the significant role of Lactobacillus species and their beneficial metabolites in alleviating neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders in experimental models or clinical settings. Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neuroinflammatory autoimmune disease that is characterized by myelin sheath degradation and axonal damage (Suganya and Koo, 2020). Kwon et al., 2013 reported that oral administration of L. casei, L. acidophilus, and L. reuteni to experimental mice resulted in delayed MS progression by enhancing Foxp3+ and IL10 + Tregs expression and reducing the pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 polarization in the peripheral immune system and inflammation site. Another similar research showed suppressed MS symptoms on supplementation with L. paracasei DSM 13434 and L. plantarum DSM 15312, particularly mediated by IL-10 producing CD4+CD25+Tregs on mice (Lavasani et al., 2010). In addition to this, human gut isolates L. reuteri NK33, L. mucosae NK41, B. longum NK46, and B. adolescentis NK98 have been reported to reduce stress-induced anxiety/depression in mice. The probable mechanisms involve modulation of gut microbial composition and inflammatory immune responses by blocking the NF-κB pathway and reducing LPS, corticosterone, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in serum (Jang et al., 2019). Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder wherein considerable decline in memory, activities, cognitive ability and thinking is observed in older adults (Suganya and Koo, 2020). Studies showed intake of L. acidophilus, B. bifidum and B. longum in rats for 12 weeks significantly augmented their spatial learning and memory, long-term potentiation (LTP), paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) ratios, and lipid profiles (Rezaei Asl et al., 2019). Further, Castelli et al., 2020 supported the neuroprotective role of Lactobacillus spp. in human neuroblastoma cells, by activating pTrK, P13K/Akt, p-CREB, pERK5 pathways and restoring gut microflora. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is another common neurodegenerative disorder marked by mood deflection, cognitive disturbances, resting tremors, slowness of movement, autonomic dysfunctions, sensory and sleep alternations, involving both the central and peripheral nervous system (Suganya and Koo, 2020). Studies have supported the role of L. acidophilus (LA02) and L. salivarius (LS01) in reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17A) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) thereby relieving Parkinson’ disease (PD)-associated symptoms (Magistrelli et al., 2019). The intricate crosstalk between gut and distant organs is illustrated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Genus Lactobacillus mediated bidirectional crosstalk affecting host’s health. Genus lactobacillus through metabolites and/or activated immune components enter circulation and reach distant organs where they enter different pathways promoting or suppressing inflammatory responses.

3.5 Cardiovascular diseases (gut-heart axis)

A plethora of literature is available that documented the role of gut-dwelling Lactobacillus species in alleviating cardiovascular diseases (CVD) that specifically include diseases of the heart and blood vessels such as congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, angina, peripheral vascular disease and aneurysm (Companys et al., 2021). Hypertension and high serum cholesterol are one of the major predisposing factors for CVD. Intestinal Lactobacillus colonies exert protective effect on the heart by regulating atheroinflammatory response, cholesterol metabolism, oxidative stress response, and gut-derived functional metabolites production such as TMAO, SCFAs, LPS, and BA (Companys et al., 2021; Papadopoulos et al., 2022). Of note, researchers also support that lactobacillus interventions could significantly impart a cardioprotective role by regulating the abundance and diversity of selective gut microbial flora (Zhao et al., 2021). To exemplify, L. salivarius Ls-33 supplementation changed gut microbiota composition by escalating the Prevotella-Bacteroides–Porphyromonas group/Firmicutes ratio in obese heart patients (Zhao et al., 2021).

In the human body, high cholesterol level in the blood is considered one of the major predisposing factors for the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the arteries. Lactobacillus in the intestine plays an important role in assimilating cholesterol and the metabolism of triglycerides and fatty acids. The proposed mechanism of action includes: 1) Bile salts degradation through the action of microbial bile salt hydrolase (BSH), making them relatively less soluble and thus reducing their reabsorption by the intestinal epithelial layer and increasing their excretion in feces as observed in L. gasseri LBM220 (Rastogi et al., 2021) and L. mucosae SRV5 and SRV10 (Rastogi et al., 2020) 2) Microbial conversion of cholesterol to relatively soluble form coprostanol which can readily assimilate and excreted out via feces 3) Incorporation of cholesterol by the microbial membrane as observed in strain L. acidophilus ATCC 43121 4) production of short chain fatty acids (SCFA). SCFA can directly impede hepatic cholesterol synthesis by inhibiting 3-hydroxymethyl-3-glutaryl-CoA reductase enzyme in the liver (Amiri et al., 2021). GM analysis revealed that lactobacillus supplementation in mice model, selectively promotes the SCFAs metabolizing commensals, such as Ruminococcus, Eubacterium and Roseburia, thereby facilitating higher levels of fermented SCFAs (Amiri et al., 2021). The study also showed L. fermentum 296 when given to high-fed rat model for 4 weeks, significantly increased HDL and reduced harmful LDL owing to their increased production of SCFA (Cavalcante et al., 2019). Further, certain lactobacillus strains are directly involved in hypercholesterolemia, such as L. plantarum 06CC2 which remarkably reduced serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides (TC), free fatty acid levels, apolipoprotein B and increase apolipoprotein A-I levels in HFD Balb/c mice. At the same time, this strain also targets hepatic tissues for lipid deposition by regulating the expression of enzymes involved in cholesterol metabolism (Yamasaki et al., 2020).

Apart from BAs and SCFAs, increasing evidence demonstrates that gut-derived microbial metabolites, particularly TMAO and LPS are also involved in the progression of CVD. Trimethylamine (TMA) is a metabolic product that is metabolized by gut commensals from dietary choline and l-carnitine which when absorbed reaches the liver where it is oxidized to TMAO. The high TMAO level causes inhibition of cholesterol reverse transport, pro-inflammatory changes in arterial vessel walls, induction of high cholesterol accumulation in macrophages, platelet hyper-responsiveness and arterial thrombosis (Zhao et al., 2021). Studies have shown Lactobacillus species alleviate TMAO-associated CVD risk by restraining the growth of gut microbes that produce key enzymes involved in TMA production. This was evidenced by research work carried out by Qiu et al., 2018, wherein L. plantarum ZDY04 intervention leads to significantly lowered TMAO circulating levels and TMAO-induced atherosclerosis by altering the relative microflora population of the genus Mucispirillum and the families Erysipelotrichaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Bacteroidaceae in the animal model. L. plantarum Dad-13 supplementation in obese adults leads to a higher population of Bacteroidetes and lower Firmicutes flora in the gut (Rahayu et al., 2021). Also, L. plantarum supplementation directly reduced serum TMAO levels as well as circulating inflammatory factors of IL8, IL-12, and leptin in CVD patients. Furthermore, LPS as a bacterial outer membrane component also induces CVD by activating macrophages to secrete pro-atherosclerotic inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α, IL-12, IL-6, IL-8) that accelerated atherosclerosis and heart failure occurrence owing to down-regulation of mitochondrial fatty acids oxidation in cardiomyocytes (Zhao et al., 2021). Also, LPS increases platelet aggregation through TLR4-mediated leukocyte cathepsin G activation causing thrombosis (Zhao et al., 2021). The L. brevis alleviated CVD onset by blocking LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine expression in the host (Chang et al., 2016). Similarly, L. paracasei FZU103 was found to modulate the LPS-induced inflammatory axis and cholesterol metabolism in mice fed with HFD. Metagenomic studies also demonstrated shift in GM, with higher abundance of Alistipes, Ruminococcus, Helicobacter and Pseudoflavonifractor but lower population of Tannerella, Blautia, and Staphylococcos in gut (Lv et al., 2021). In L. plantarum LP91-fed LPS-induced mice, expression of atherosclerotic inflammatory factors, particularly TNF-α and IL-6, vascular cell adhesion molecule, E-selectin was found to be downregulated, thus showing improvement in CVD symptoms (Aparna Sudhakaran et al., 2013).

3.6 Metabolic disorders

Many recent publications have reported the beneficial role of Lactobacillus spp. in assuaging the onset of metabolic disturbances, such as obesity and diabetes mellitus, which are characterized by a low-grade inflammation (Archer et al., 2021).

3.6.1 Obesity

Obesity is a multifaceted metabolic disease associated with changes in adipose tissues (AT), which is a complex endocrine organ involved in energy homeostasis. Usually, AT are subsuming adipocytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells that produce plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1), adiponectin, leptin, vascular regulators angiotensin II and cytokines (Andersen et al., 2016). The onset of obesity leads to dysfunctional AT with physiological changes in vascularization, oxidative stress levels, secreted adipokines and inflammatory state of infiltrated lymphocytes (Jo et al., 2009). In obese patients, a rise in free fatty acids (FFAs) level causes activation of signalling pathways, particularly TLRs which contribute to the pro-inflammatory response by increasing the production of molecules such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL1β, leptin, resistin, and chemokines in cells from lamina propria of gut (Khan et al., 2021). In the gut, activation of TNF-α stimulates apoptosis signalling pathways, FFAs levels and downregulates the expression of GLUT-4 transporters. In the high-fed diet (HFD) mice group, infiltration of CD8+ T cells, TNF-α, IFN-ɣ, and CX3CR1int macrophages in adipose tissues in response to high glucose, FFAs and apoptosis leads to inflammation. Of note, one of the driver for inflammatory alterations and loss of gut epithelial integrity in obesity includes, leakage of bacterial endotoxin LPS (Khan et al., 2021). This leads to an inadequate distribution of lymphocytes, changes in cytokines levels, gut microbiota and immune response to dietary antigens. Much research has been centred on the importance of lactobacillus in treating obesity by alleviating lipid accumulation, oxidative damage, inflammation, and gut dysbiosis. A recent publication reported synergistic effects of L. curvatus HY7601 and L. plantarum KY1032 in lowering excess weight and fat accumulation in the HFD mice group with reduced inflammatory biomarkers (Park et al., 2013). Choi et al., 2020, reported weight loss in HFD-fed mice when treated with L. plantarum LMT1-48 with fewer lipids accumulation, immune cells infiltration in AT and adipocyte size. Notably, multiple strains of lactobacillus-particularly, L. casei IMVB-7280, L. paracasei HII0, L. paracasei CNCM I-4034, L. rhamnosus CGMCC1.3, L. rhamnosus LA68 and L. casei IBS041 have proved positive effects in reducing obesity symptoms, likely, reduced weight gain, lower cholesterol levels, lower adiposity and inflammation (Wiciński et al., 2020). Similarly, L. reuteri GMNL-263 ameliorated symptoms pertaining to obesity in HFD-fed rats by decreasing serum pro-inflammatory factors levels and remodeling white adipose tissue (WAT) energy metabolism (Chen et al., 2018). Besides, Joung et al., 2021 reported lower fat accumulation in AT in HFD-fed mice on L. plantarum administration, which was attributed to altered gut microbiota with reduced Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. Overall, Lactobacillus strains have achieved remarkable results in the treatment of obesity-related symptoms.

3.6.2 Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, a chronic metabolic disease is characterized by a consistently high serum glycemic index. A study of the Global Burden of Disease 2015 has reported that diabetes is one of the major causes of mortality in urban populations. There has been a significant association between the inflammatory condition and metabolic disturbances among diabetic patients. The postulated mechanism includes raised levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α which inactivates insulin receptor (IRS-I) by phosphorylating serine residue. While other cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β works in a synergistic manner by infiltrating the β-cells of the pancreas, subsequently inducing cellular apoptosis and damage. Thus, higher pro-inflammatory cytokines levels in muscle, liver and adipose tissues are major drivers of diabetes pathology as they inhibit insulin signalling causing insulin resistance (Tsalamandris et al., 2019; Bezirtzoglou et al., 2021). Interestingly, L. plantarum Y44 showed downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes in the liver, intestine and muscle tissues particularly by activating regulatory anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, highlighting their immunomodulatory role (Liu et al., 2020). Likewise, L. casei Shirota strain showed reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rat models (Zarfeshani et al., 2011). Archer et al. (2021) also reported L. fermentum MCC2759 exhibited a reduction in glucose profile and pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10 in the liver, MAT, muscle and intestinal tissues in STZ-induced diabetic rats. This study also proved enhanced insulin sensitivity (GLP-1, GLUT-4, adiponectin), intestinal barrier integrity (ZO-1) and TLR-4 receptor expression. In addition to this, L. casei is reported to reduce serum glucose contents owing to improvement in post-immune responses via suppression of IL-2 and IFN- γ production (Qu et al., 2018). Another study by Park et al. (2015) reported that the anti-hyperglycemic effect on male db/db mice on administration of L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) is associated with increased ER stress and suppressed macrophages, leading to increased insulin sensitivity. Also, alteration in the expression of some diabetes-associated genes plays a role. Probiotic L. rhamnosus NCDC17 has reported to have antidiabetic capacity owing to its ability to upregulate mRNA expression of glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity related genes such as GLUT4 (glucose uptake related genes), pp-1 (glycogen synthesis related genes) and PPAR- γ (insulin sensitivity related genes) and downregulating G6PC (gluconeogenesis related genes) (Singh et al., 2017). Further, consumption of probiotics affects the gut microflora composition which in turn alleviates intestinal epithelium and suppresses the immune response by reducing the TLR4 signalling pathway, ultimately increasing insulin sensitivity (Li et al., 2021). Some other postulated mechanisms include enhanced glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion from intestinal L-cells to inhibit postprandial hyperglycemia by elevating the level of insulin released from pancreatic beta cells and reducing glucotoxicity (Kesika et al., 2019). A study involving L. kafiranofaciens M and L. kefiri K administration was found to stimulate GLP-1 secretion with concomitant rise in glucose metabolism (Kocsis et al., 2020).

3.7 Bone health (gut-bone axis)

Metabolic bone disorder, osteoporosis is characterized by poor bone tissues, deteriorated bone mass and porosity which subsequently lead to weak and brittle bones that are susceptible to fractures (Akkawi and Zmerly, 2018). Notably, Lactobacillus spp. as whole bacteria or their metabolites and/or structural components (such as SCFAs, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), insulin-like growth factor- I (IGF-I), LPS and peptidoglycans, etc) act as powerful immune cells controller and exhibit regulatory role in bone resorption and formation (Zaiss et al., 2019). Thereby, confirming their role as a linker in the “Gut-Bone axis”. Factors namely, IGF-I produced predominately in hepatic cells in response to dietary intake and gut microbes directly mediate the gut-bone axis (Zaiss et al., 2019). The microbial metabolite, H2S acts as a gasotransmitter, is produced by gut-resident Lactobacilli spp. and stimulates bone formation and postnatal skeletal development by activating Wnt signaling (Grassi et al., 2016). In osteoblasts, wnt signaling activation mediates enhanced osteoblastogenesis and arrests osteoblast apoptosis. Moreover, SCFAs have gained tremendous attention for their capacity to diffuse bone tissues and regulate immune responses (Zaiss et al., 2019). SCFA, particularly butyrate and propionate induce the proliferation of mature Treg cells. The maturation of Tregs depends upon GPR109a and GPR43 receptors expressed on dendritic cells (DC). The Treg cells suppress the CD4+ T cells that are present on the endosteal surfaces of the bone by producing immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β; resulting in improved osteoporosis and bone mass density (BMD) by directly increasing osteoblast differentiation and reducing osteoclastogenesis (Smith et al., 2013). Also, activated Tregs cells are required for calciotropic parathyroid hormone–stimulated (PTH-stimulated) bone formation as it induces bone anabolism via Treg/Wnt10b/Wnt signaling pathway (Yu et al., 2018). Dietary supplementation with L. rhamnosus LGG for 4 weeks directly increased circulating and intestinal butyrate levels, confirming its capacity to diffuse from the intestine to distant organs like bone. In bone tissues, the butyrate induces Tregs and improves bone health. This study by Tyagi et al., 2018 further proved that L. rhamnosus LGG also altered gut microbial composition, with a higher Clostridia population that is known to elicit the generation of SCFAs in the gut. Thus, L. rhamnosus LGG substantially mediates the pathway linking SCFAs, Tregs, and bone formation.

To date, multiple studies have utilized animal models to determine lactobacillus efficacy in reducing both primary and secondary osteoporotic bone loss. Oral intake of L. reuteri ATCC 6475 by healthy male mice for 1 month resulted in improved bone mineral content, vertebral and femoral trabecular bone density, trabecular thickness and trabecular number when compared to untreated controls. Increased bone density leads to higher levels of bone formation rate as evidenced by the osteoblast marker osteocalcin. L. reuteri ATCC 6475 acts by systemically suppressing gene expression of pro-osteoclastogenic and pro-inflammatory cytokines in both the bone marrow and the intestine (Nilsson et al., 2018). These anti-inflammatory effects, which are also observed in other species of Lactobacillus tend to directly increase the calcium transport across the intestinal barrier. Immune cell activation largely depends on calcium levels. In case of hypocalcemia, treatment of rats with yogurt-enriched with L. casei, L. reuteri and L. gasseri improved calcium absorption in a PTH-dependent manner. Likewise, L. rhamnosus (HN001) also improved calcium and magnesium retention in rat models (Collins et al., 2017). Ohlsson et al., 2014 treated mice with either a single L. paracasei strain (DSM13434) or a mixture of three strains (L. plantarum DSM 15312, DSM 1531 and L. paracasei DSM13434) in the water for 14 days resulted in increased cortical bone mineral content and decreased levels of urinary fractional excretion of calcium and resorption marker C-terminal telopeptides as compared to control. Different Lactobacillus strains act via distinct and/or overlapping pathways, such as L. helveticus was found to not only increase bone density by elevating calcium uptake, but also secrete bioactive peptides valyl-prolyl-proline (VPP) and isoleucyl-prolyl-proline (IPP) (Parvaneh et al., 2018). Further, conversion of insoluble inorganic salts into soluble forms, protection of intestinal mineral absorption sites, triggering of the modulation of calcium-binding proteins, and minimization of the interaction of minerals with phytic acids are the main actions reported by different strains of Lactobacillus that supported bone health.

4 Future prospects

An exponential advancement in sequencing processing, genome assembly and annotation technologies, has resulted in thousands of publicly available genomes of Lactobacillus spp. Access to these data has revolutionized the molecular view of probiotic bacteria, significantly accelerating the research deciphering the complexity associated with interactions between resident microbiota and the mucosal immune system. Notably, advancements in genomic tools, particularly functional genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and secretomics have helped in understanding the intricate dynamic host-microbe crosstalk that extends far beyond gastrointestinal health. To exemplify, studies on the bi-directional crosstalk between the GIT and the brain (gut-brain axis) are revealing the neurochemical importance of gut homeostasis. Similarly, studies involving the GIT and the lungs crosstalk (gut-lung axis) highlight the significance of microbial metabolites in regulating host’s immune responses. In addition this, Lactobacillus spp. modulate mucosal immunity through the interaction of proteinacious microorganism-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells and macrophages. Recently, the proteomic and genomic profiles of several lactobacilli were bioinformatically screened to create a secretome database cataloging the various extracellular proteins. For example, a proteomic-based method was used to identify S-layer associated proteins (SLAPs) in L. acidophilus. After extraction, the SLAPs were identified through mass spectrometry and referenced to the secretome database. The mutational analysis of SLAPs showed immunomodulatory phenotype using in vitro bacterial-DC co-incubation assays (Huang et al., 2021). However, it is important to note that the transcriptional networks induced by each probiotic were unique to each strain studied and that they show distinct metabolic and immunogenic profiles in the host. Thus, there is a growing need for human clinical trials with experimental designs, reflecting the future progress that has been made in the field of probiotics and GIT microbiome research.

5 Conclusion

Taken together, the intestinal microbial species, particularly Lactobacilli spp., within gut are identified as potential and talented players in restoring gastrointestinal barrier function, immune stimulation and gut microbial flora. So far, we have highlighted the intricate crosstalk between gut-dwelling Lactobacilli spp., or their metabolites and the immune components in distant organs to promote host’s health. The healthy balance in the intestinal ecosystem is preserved by the circuitry of monitoring mechanisms between potentially pro-inflammatory cell [Th cells secreting IFN-y, Th17 cells that secrete interleukin IL-17, and IL-22], and anti-inflammatory Foxp3+ receptor Tcells. Certain strains of lactobacilli stimulate the anti-inflammatory fork of the adaptive immune system by controlling Treg maturation or by driving IL-10 and IL-12 production. Given the current epidemic of inflammatory disorders plaguing present society, a call is necessary for feasible, available, and safe treatments to prevent and fight against it. Even though inflammatory and metabolic disorders pathogenesis is multifactorial and highly complexed, yet recent literature suggests modulation of gut microbial flora and immune responses using probiotics as the primary therapeutic intervention. Consequently, gut microbiome modulation to preserve a stable, consistent metabolic environment may be helpful in preventing and as additional treatment in affected patients. In future, far more in-depth clinical studies will be required to substantiate the therapeutic approaches with lactobacillus in directly maintaining gut microbiota homeostasis and regulate functional metabolites (such as TMAO, SCFAs, BAs, and LPS) which further lower risks associated with immune inflammation, high lipid cholesterol and oxidative stress. From author’s viewpoint, those looking to ameliorate their overall health by improving their gastrointestinal microbial complexity might find it more beneficial to target on consuming a fermented diet (such as yoghurt, kimchi, miso, sauerkraut) rich in Lactobacillus spp. To conclude, therapy with Lactobacillus spp. still provides a potential frontier in the treatment and prevention of inflammatory diseases.

Author contributions

SR collected literature data, wrote the manuscript, drew the figure, and tabulated the table. AS reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ahire J. J., Sahoo S., Kashikar M. S., Heerekar A., Lakshmi S. G., Madempudi R. S. (2021). In vitro assessment of lactobacillus crispatus UBLCp01, lactobacillus gasseri UBLG36, and lactobacillus johnsonii UBLJ01 as a potential vaginal probiotic candidate. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 10.1007/s12602-021-09838-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan A., Mazhar B., Khan M. K., Mustafa M., Hammad M., Ali N. M. (2022). Bacteriocin-mediated inhibition of some common pathogens by wild and mutant Lactobacillus species and in vitro amplification of bacteriocin encoding genes. ADMET DMPK 10, 75–87. 10.5599/admet.1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkawi I., Zmerly H. (2018). Osteoporosis: Current concepts. Joints 6, 122–127. 10.1055/s-0038-1660790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri P., Hosseini S. A., Ghaffari S., Tutunchi H., Ghaffari S., Mosharkesh E., et al. (2021). Role of butyrate, a gut microbiota derived metabolite, in cardiovascular diseases: A comprehensive narrative review. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 837509. 10.3389/fphar.2021.837509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand S., Mande S. S. (2018). Diet, microbiota and gut-lung connection. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2147. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen C. J., Murphy K. E., Fernandez M. L. (2016). Impact of obesity and metabolic syndrome on immunity. Adv. Nutr. 7, 66–75. 10.3945/an.115.010207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparna Sudhakaran V., Panwar H., Chauhan R., Duary R. K., Rathore R. K., Batish V. K., et al. (2013). Modulation of anti-inflammatory response in lipopolysaccharide stimulated human THP-1 cell line and mouse model at gene expression level with indigenous putative probiotic lactobacilli. Genes. Nutr. 8, 637–648. 10.1007/s12263-013-0347-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer A. C., Muthukumar S. P., Halami P. M. (2021). Lactobacillus fermentum MCC2759 and MCC2760 alleviate inflammation and intestinal function in high-fat diet-fed and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 13, 1068–1080. 10.1007/s12602-021-09744-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad M. A. K., Sarker M., Wan D. (2018). Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics on cytokine profiles. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 8063647. 10.1155/2018/8063647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banna G. L., Torino F., Marletta F., Santagati M., Salemi R., Cannarozzo E., et al. (2017). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: An overview to explore the rationale of its use in cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 603. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Raichon L., Colom A., Monard S. C., Namouchi A., Cescato M., Garnier H., et al. (2021). A pulmonary lactobacillus murinus strain induces Th17 and RORγt+ regulatory T cells and reduces lung inflammation in tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 207, 1857–1870. 10.4049/jimmunol.2001044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezirtzoglou E., Stavropoulou E., Kantartzi K., Tsigalou C., Voidarou C., Mitropoulou G., et al. (2021). Maintaining digestive health in diabetes: The role of the gut microbiome and the challenge of functional foods. Microorganisms 9, 516. 10.3390/microorganisms9030516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breit S., Kupferberg A., Rogler G., Hasler G. (2018). Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain–gut Axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Front. Psychiatry 9, 44. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton R.A., Irwin R., Quach D., Schaefer L., Zhang J., Lee T., et al. (2014). Probiotic L. reuteri treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. J. Cell. Physiol 229, 1822–1830. 10.1002/jcp.24636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli V., d’Angelo M., Lombardi F., Alfonsetti M., Antonosante A., Catanesi M., et al. (2020). Effects of the probiotic formulation SLAB51 in in vitro and in vivo Parkinson’s disease models. Aging (Albany NY) 12, 4641–4659. 10.18632/aging.102927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante R. G. S., de Albuquerque T. M. R., de Luna Freire M. O., Ferreira G. A. H., Carneiro Dos Santos L. A., Magnani M., et al. (2019). The probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum 296 attenuates cardiometabolic disorders in high fat diet-treated rats. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 29, 1408–1417. 10.1016/j.numecd.2019.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang V. H.-S., Chiu T.-H., Fu S.-C. (2016). In vitro anti-inflammatory properties of fermented pepino (Solanum muricatum) milk by γ-aminobutyric acid-producing Lactobacillus brevis and an in vivo animal model for evaluating its effects on hypertension. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 192–198. 10.1002/jsfa.7081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.-H., Chen Y.-H., Cheng K.-C., Chien T.-Y., Chan C.-H., Tsao S.-P., et al. (2018). Antiobesity effect of Lactobacillus reuteri 263 associated with energy metabolism remodeling of white adipose tissue in high-energy-diet-fed rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 54, 87–94. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Chen W., Ci W., Zheng Y., Han X., Huang J., et al. (2022). Effects of dietary supplementation with lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus subtilis on mucosal immunity and intestinal barrier are associated with its modulation of gut metabolites and microbiota in late-phase laying hens. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 10.1007/s12602-022-09923-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. J., Dong H. J., Jeong H. U., Ryu D. W., Song S. M., Kim Y. R., et al. (2020). Lactobacillus plantarum LMT1-48 exerts anti-obesity effect in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by regulating expression of lipogenic genes. Sci. Rep. 10, 869. 10.1038/s41598-020-57615-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. L., Rios-Arce N. D., Schepper J. D., Parameswaran N., McCabe L. R. (2017). The potential of probiotics as a therapy for osteoporosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 5. BAD-0015–2016. 10.1128/microbiolspec.BAD-0015-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Companys J., Pedret A., Valls R. M., Solà R., Pascual V. (2021). Fermented dairy foods rich in probiotics and cardiometabolic risk factors: A narrative review from prospective cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61, 1966–1975. 10.1080/10408398.2020.1768045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compare D., Rocco A., Coccoli P., Angrisani D., Sgamato C., Iovine B., et al. (2017). Lactobacillus casei DG and its postbiotic reduce the inflammatory mucosal response: An ex-vivo organ culture model of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 17, 53. 10.1186/s12876-017-0605-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofori F., Dargenio V. N., Dargenio C., Miniello V. L., Barone M., Francavilla R. (2021). Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in gut inflammation: A door to the body. Front. Immunol. 12, 578386. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.578386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Conno B., Pesce M., Chiurazzi M., Andreozzi M., Rurgo S., Corpetti C., et al. (2022). Nutraceuticals and diet supplements in Crohn’s disease: A general overview of the most promising approaches in the clinic. Foods 11, 1044. 10.3390/foods11071044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey E., Corr S. C. (2022). Lactobacillus spp. for gastrointestinal health: Current and future perspectives. Front. Immunol. 13, 840245. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.840245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do A. D., Chang C.-C., Su C.-H., Hsu Y.-M. (2021). Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB3 inhibits Helicobacter pylori infection through multiple molecular actions. Helicobacter 26, e12806. 10.1111/hel.12806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogi C., García G., De Moreno de LeBlanc A., Greco C., Cavaglieri L. (2016). Lactobacillus rhamnosus RC007 intended for feed additive: Immune-stimulatory properties and ameliorating effects on TNBS-induced colitis. Benef. Microbes 7, 539–547. 10.3920/BM2015.0147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du T., Lei A., Zhang N., Zhu C. (2022). The beneficial role of probiotic lactobacillus in respiratory diseases. Front. Immunol. 13, 908010. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.908010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi M., Powali S., Rastogi S., Singh A., Gupta D. (2021). Microbial community in human gut: a therapeutic prospect and implication in health and diseases. Lett. Appl. Microbiol 73, 553–568. 10.1111/lam.13549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Chen H.-Q., Zhang X., Zhang H., Xia J., Ding K., et al. (2019). Probiotic administration of lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 attenuates atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE-/- mice fed with a high-fat diet. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 3533–3541. 10.26355/eurrev_201904_17722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good M., Sodhi C. P., Ozolek J. A., Buck R. H., Goehring K. C., Thomas D. L., et al. (2014). Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 decreases the severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonatal mice and preterm piglets: Evidence in mice for a role of TLR9. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306, G1021–G1032. 10.1152/ajpgi.00452.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi F., Tyagi A. M., Calvert J. W., Gambari L., Walker L. D., Yu M., et al. (2016). Hydrogen sulfide is a novel regulator of bone formation implicated in the bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency. J. Bone Min. Res. 31, 949–963. 10.1002/jbmr.2757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J., Oehrle K., Worthen G., Alenghat T., Whitsett J., Deshmukh H. (2017). Intestinal commensal bacteria mediate lung mucosal immunity and promote resistance of newborn mice to infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaaf9412. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Tang C., Baba S., Hamada T., Shimazu T., Iwakura Y. (2021). Ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation is ameliorated in dectin-1-deficient mice, in which pulmonary regulatory T cells are expanded through modification of intestinal commensal bacteria. J. Immunol. 206, 1991–2000. 10.4049/jimmunol.2001337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Zhao Z., Duan C., Wang C., Zhao Y., Yang G., et al. (2021). Lactobacillus plantarum C88 protects against aflatoxin B1-induced liver injury in mice via inhibition of NF-κB–mediated inflammatory responses and excessive apoptosis. BMC Microbiol. 19, 170. 10.1186/s12866-019-1525-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Zhou X., Stanton C., Ross R. P., Zhao J., Zhang H., et al. (2021). Comparative genomics and specific functional characteristics analysis of lactobacillus acidophilus . Microorganisms 9, 1992. 10.3390/microorganisms9091992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadrešin O., Sila S., Trivić I., Mišak Z., Kolaček S., Hojsak I. (2020). Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 is effective in the treatment of functional abdominal pain in children: Results of the double-blind randomized study. Clin. Nutr. 39, 3645–3651. 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H.-M., Lee K.-E., Kim D.-H. (2019). The preventive and curative effects of lactobacillus reuteri NK33 and bifidobacterium adolescentis NK98 on immobilization stress-induced anxiety/depression and colitis in mice. Nutrients 11, E819. 10.3390/nu11040819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., Gavrilova O., Pack S., Jou W., Mullen S., Sumner A. E., et al. (2009). Hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia: Dynamics of adipose tissue growth. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000324. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung H., Chu J., Kim B.-K., Choi I.-S., Kim W., Park T.-S. (2021). Probiotics ameliorate chronic low-grade inflammation and fat accumulation with gut microbiota composition change in diet-induced obese mice models. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105, 1203–1213. 10.1007/s00253-020-11060-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara T., Shimizu I., Tanaka Y., Tobita K., Tomokiyo M., Watanabe I. (2022). Lactobacillus crispatus strain KT-11 S-layer protein inhibits rotavirus infection. Front. Microbiol. 13, 783879. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.783879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesika P., Sivamaruthi B. S., Chaiyasut C. (2019). Do probiotics improve the health status of individuals with diabetes mellitus? A review on outcomes of clinical trials. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 1531567. 10.1155/2019/1531567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S., Luck H., Winer S., Winer D. A. (2021). Emerging concepts in intestinal immune control of obesity-related metabolic disease. Nat. Commun. 12, 2598. 10.1038/s41467-021-22727-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocot A. M., Jarocka-Cyrta E., Drabińska N. (2022). Overview of the importance of biotics in gut barrier integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2896. 10.3390/ijms23052896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis T., Molnár B., Németh D., Hegyi P., Szakács Z., Bálint A., et al. (2020). Probiotics have beneficial metabolic effects in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 10, 11787. 10.1038/s41598-020-68440-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh A., De Vadder F., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., Bäckhed F. (2016). From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 165, 1332–1345. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolling Y., Salva S., Villena J., Alvarez S. (2018). Are the immunomodulatory properties of Lactobacillus rhamnosus CRL1505 peptidoglycan common for all Lactobacilli during respiratory infection in malnourished mice? PLoS One 13, e0194034. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullisaar T., Zilmer K., Salum T., Rehema A., Zilmer M. (2016). The use of probiotic L fermentum ME-3 containing Reg’Activ cholesterol supplement for 4 weeks has a positive influence on blood lipoprotein profiles and inflammatory cytokines: An open-label preliminary study. Nutr. J. 15, 93. 10.1186/s12937-016-0213-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumova O. K., Fike A. J., Thayer J. L., Nguyen L. T., Mell J. C., Pascasio J., et al. (2019). Lung transcriptional unresponsiveness and loss of early influenza virus control in infected neonates is prevented by intranasal Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1008072. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H.-K., Kim G.-C., Kim Y., Hwang W., Jash A., Sahoo A., et al. (2013). Amelioration of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by probiotic mixture is mediated by a shift in T helper cell immune response. Clin. Immunol. 146, 217–227. 10.1016/j.clim.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavasani S., Dzhambazov B., Nouri M., Fåk F., Buske S., Molin G., et al. (2010). A novel probiotic mixture exerts a therapeutic effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mediated by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells. PLoS One 5, e9009. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laval L., Martin R., Natividad J. N., Chain F., Miquel S., Desclée de Maredsous C., et al. (2015). Lactobacillus rhamnosus CNCM I-3690 and the commensal bacterium Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii A2-165 exhibit similar protective effects to induced barrier hyper-permeability in mice. Gut Microbes 6, 1–9. 10.4161/19490976.2014.990784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.-Y., Zhou D.-D., Gan R.-Y., Huang S.-Y., Zhao C.-N., Shang A., et al. (2021). Effects and mechanisms of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics on metabolic diseases targeting gut microbiota: A narrative review. Nutrients 13, 3211. 10.3390/nu13093211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Fang Z., Liu X., Hu W., Lu W., Lee Y., et al. (2019). Lactobacillus reuteri attenuated allergic inflammation induced by HDM in the mouse and modulated gut microbes. PLoS One 15, e0231865. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.-C., Hsu W.-F., Chang J.-S., Shih C.-K. (2019). Combination of lactobacillus acidophilus and bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis shows a stronger anti-inflammatory effect than individual strains in HT-29 cells. Nutrients 11, E969. 10.3390/nu11050969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-W., Liong M. T., Chung Y.-C. E., Huang H.-Y., Peng W.-S., Cheng Y.-F., et al. (2019). Effects of lactobacillus plantarum PS128 on children with autism spectrum disorder in taiwan: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 11, 820. 10.3390/nu11040820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Gao Y., Ma F., Sun M., Mu G., Tuo Y. (2020). The ameliorative effect of Lactobacillus plantarum Y44 oral administration on inflammation and lipid metabolism in obese mice fed with a high fat diet. Food Funct. 11, 5024–5039. 10.1039/d0fo00439a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Li Y., Yu X., Yu L., Tian F., Zhao J., et al. (2021). Physiological characteristics of lactobacillus casei strains and their alleviation effects against inflammatory bowel disease. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31, 92–103. 10.4014/jmb.2003.03041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]