Abstract

The data has been compiled from peer-reviewed journals, published books, some organizational reports, and papers from conferences. The major electronic databases that have been utilized for this review, to collect publications that are relevant to the research aims include Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct databases. The keywords used to search were WASH, Hygiene, School, Policy, and Programs. In addition, primary explorations were also steered in the Johns Hopkins Health Resource and US CDC Library, and Ministry of Health and family welfare, India.

Keywords: Hygiene, programmes, sanitation, school, WASH, water

Introduction

School acts as cognitive, creative along with social development center for children where teacher act as a facilitator playing a crucial role in developing the future generations of responsible citizens. Children being more receptive during this age period, good habits can be easily cultivated. So, school Sanitation and Hygiene Education is essential for children as a safe and healthy environment to learn better to challenges in future life. All components of WASH practices, that is, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene are very much dependent on each other. In India, central and state governments have committed to ensure the access to safe WASH facilities for children in schools.[1]

Actually school is the double sword environment as children spend reasonable time of the day there. It can be the forum for learning healthy lifestyle including safe WASH practices, and on the other hand, unfavourable environment can lead to infectious diseases among the innocents. It is also important that children should know the importance of safe WASH practices and risk of unsafe WASH to their health. Role of teachers and children are equally counted as facility providers. WASH is about Attitudinal and Behavioural Change (ABC). However, the mere creation of infrastructure is not sufficient to adopt safe WASH for long term or to the next generation, it requires consistency in practical input and application.

WASH Across Globe

In 1990, a collaborative Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for WASH was launched by WHO and UNICEF.[2] This programme set the global norms to achieve and compare the progress across the countries in WASH sector as well as WASH-related Sustainable Development Goal (targets 6).[3]

The Vision 2030 set the Sustainable Development Goals and for WASH in schools (SDG6) which aims to ‘ensure available and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’ and includes targets 6.1 and 6.2 for universal access to WASH for all by 2030.

Globally, in 2016, 69% schools provided basic drinking water services which includes both improved source of water and availability of water. Worldwide, 66% of schools had a basic sanitation services (single-sex facility and usable), and only half (53%) of the schools had a basic hygiene services (water and soap available).[4]

Indian Scenario

Mahatma Gandhi always promoted sanitation but after independence this social reform got silent unfortunately. Then, in first five-year plan (1951–1956), the concept of drinking water provision in rural areas put forward.[5,6] Later various programmes and activities were planned and conducted for improving the WASH status in rural community.

The Vth and VIth All India Education surveys reported that, in 1986 only 46% of schools had a safe drinking water facility which later dropped to 44% in 1993. All over India, only one out of ten schools had sanitation facilities. Though this is the national average, some districts/states improved better but some are lagging behind much more. This scenario called upon the need to improve the basic infrastructure, that is, safe water drinking water facilities and lavatory provisions.[7]

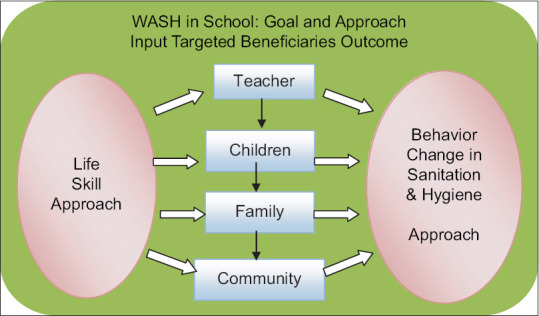

In India, during the survey in 2016, it was observed that 69% of schools provided safe drinking water. Schools having unsafe drinking water facilities in 2010 and 2016 in India were 17% and 9%, respectively. Survey also recorded availability of basic sanitation in 73% and hygiene services in half (54%) of the schools.[4] There was need to improve the policy and programme strategies for safe WASH practices in schools in India. Hence various programme and activities have initiated and still going on as shown in Table 1. Basic sanitation and safe water provision is recommended in primary healthcare services. Health education regarding hygiene is also one of the components of PHC.

Table 1.

Programmes in India

| Name | Year of launch |

|---|---|

| Central Rural Sanitation Program | 1986 |

| Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission | 1991 |

| District Primary Education Program | 1994 |

| Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC) | 1999 |

| School Sanitation and Hygiene Education (SSHE) | 2000 |

| School Water and Sanitation Towards Health and Hygiene (SWASTHH) | 2000 |

| Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) | 2001 |

| Janshala Program (Nine-state, South India) | 2002 |

| Nirmal Gram Puraskar | 2003 |

| National Rural Drinking Water Programme-(Jalmani) | 2009 |

| Right to Education Act | 2009 |

| Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan | 2009 |

| Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (Rename of TSC) | 2012 |

| Swachh Bharat Abhiyan/mission (Replaced NBA) | 2014 |

| Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan/campaign | 2014 |

| National Water Policy | 1987, 2002, 2012 |

| Water Aid | 2016 |

| Swachh BharatKosh | 2019 |

Objectives: Through this literature search, we tried to review the various programmes and activities conducting for improving WASH practices in schools of India.

Discussion: In India, to begin with sanitation and hygiene programmes started at community level and then household level. Focus on school sanitation and hygiene is shifted later. These programmes are the examples of integrated approach of various sectors in the society.

Central Rural Sanitation Program – This programme was launched in 1986 with the objectives to improve the quality of life by proper sanitation practices. Therefore, this concept of sanitation was explored to include not only disposal of human excreta or waste but also hygiene, home sanitation and provision of safe drinking water. This was the first programme where initiative was taken to provide privacy and dignity to Indian women.[1,8] A comprehensive baseline survey was conducted during 1996–1997 regarding attitude and practices of drinking water and sanitation in rural settings and it was observed that half of the community was self-motivated for construction of latrines, for convenience and privacy. By keeping in view this observation, CRSP was improved towards ‘demand driven’ approach. This new initiative titled as “Total Sanitation Campaign”.[9,10]

Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC): This programme is started in 250 districts to universalise sanitation facilities particularly in rural and tribal settings. Indian Government introduced TSC in 1999. School sanitation was planned as a primary intervention with following objectives.[1,8,9,10]

Provision of water and sanitation facilities in schools to develop consistent habits among the children.

Promote the use of toilets/urinals, and other hygiene behaviours among school students.

Promote hygiene education to achieve behavioural change at personal and community level.

Build the capacities of stakeholders including teachers, parents and Panchayat Raj Institute to develop institutional systems within the schools for facilities and maintenance.

In 2012, Total Sanitation Campaign then renamed Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (NBA) and in 2014, it is again relaunched as Swachh Bharat Abhiyan.[11,12,13]

The vision of the scheme NBA was to accelerate the usage of proper sanitation in the country through various Gram Panchayats. The NBA scheme also joins Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan through which the school children are educated on relation of sanitation and health, and encourage them for adopting sanitation practices. This mission worked for increasing the awareness about cleanliness and to guide rural people on proper waste management including solid and liquid waste disposal.

School Sanitation and Hygiene Education (SSHE)

The Government of India has launched the programme for schools especially in rural settings called the SSHE. This programme is one of the investment steps in building the children’s future by improving the services for safe drinking water, basic sanitation and hygiene practices.[7,14]

Evolution of SSHE in India – TSC focusses on community-leadership and people-centred initiatives and provided wide services for sanitation. Then, it was identified that the primary education sector is a high potential to inculcate the basic sanitation practices in households, schools and to continue in further life. SSHE is a one of the component of TSC, which focusses on sanitation and hygiene in schools[15,16] and set out following goals should be achieved by 2005–2006.[14]

Provision of water, sanitation and hand washing facilities simultaneously hygiene education in all rural schools

Coverage of all Anganwadi centers by providing toilet facilities

In co-ed schools, separate urinal and toilet facilities for girls

Approach towards Goals – To achieve these goals along with creation of hardware, that is, infrastructure in the schools, hygiene education is also crucial. For this purpose, at least one teacher should be trained in hygiene activities and community mobilization projects which promote behavioural change.[14,17]

In this programme, Central Government, State Government and Parent–Teacher Association is involved. Intersectoral coordination is achieved by involving various departments and ministry, such as Department of Drinking Water Supply, Department of Elementary Education and Literary, Department of Women and Child Development, Ministry of Rural Development, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Ministry of Tribal Affairs.[14,17,18]

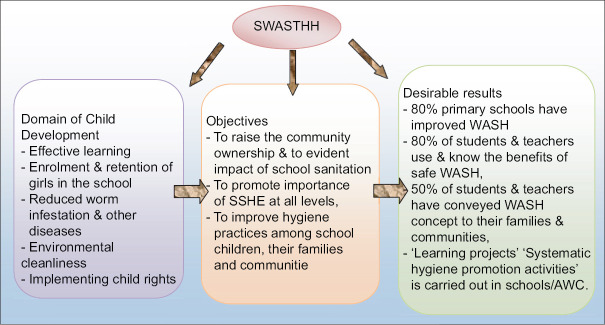

SSHE has an ultimate goal of behaviour change regarding sanitary and hygiene practices in community and implemented route is from Teacher–Children–Family–Community through life skill approach, shown in Figure 1.[17,18]

Figure 1.

WASH in school: Goal and approach

SSHE depends on a process of capacity augmentation of teachers, education administrators, village level heath, water and sanitation committees, public health engineering and rural development departments, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and community-based organizations (CBOs).[17,19]

School Water and Sanitation Towards Health and Hygiene (SWASTHH) – This programme is arise from SSHE through innovation such as collaboration with UNICEF, Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission (RGNDWM) and International Resource Center (IRC) and started in March 2000.

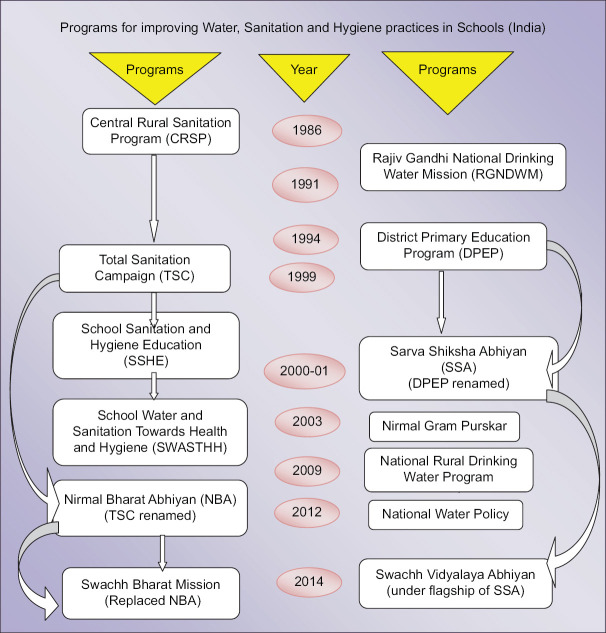

Literal meaning of SWASTHH is ‘health’ in Hindi language and it is one of several government initiatives with goal to improve the education along with quality of life of children through changing the culture and environment of schools in rural settings. In this programme, steps are taken towards provision of safe drinking water and lavatory facilities, but that is beyond this construction programme. This programme focusses on reaching the difficult-to-reach including girls and marginalised communities).[9,17,18] SWASTHH programme focusses on several domain of child development with objectives and outcome as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SWASTHH programme: Domain, objectives, outcome

This programme is started in three states of India (Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand and Karnataka) where five districts were selected in each state. Later on other states also adopted this programme. For better impact, programme convergence through optimal utilization of available resources. Community participation and mobilization in implementation, operation and maintenance is the principle strategy, which needs capacity building of local groups. Hence, resource book is prepared for training of all stakeholders involved in this programme such as Interdisciplinary groups – representatives from Education, ICDS programme, NGOs, health sector, and teachers.[17,18]

Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (NBA) worked to generate attentiveness among people particularly from rural about the importance of sanitation through IEC activities. This mission is to get better quality of life and to educate the rural women for using proper sanitation not only for health or pollution issue but also for safeguard. NBA achieved success in covering more number of rural villages with proper sanitations. This campaign motivates more number of rural families to adopt proper sanitation facilities and practices.[11,12]

Recently, the strategy is adopted to transform rural India into ‘Nirmal Bharat’ by providing financial incentive for individual household construction of toilets and this has been widened to cover all Above the Poverty Line and all Below the Poverty Line households to attain community outcomes.[20]

Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM)

On 2 October 2014, Hon’ble Prime Minister of country launched Swachh Bharat Mission. This was a cleanliness campaign for throughout development of the country with the goal of attaining ‘Open-Defecation Free’ India by 2 October 2019. It was planned to construct over 100 million toilets in rural settings.[21,22]

Objectives of SBM were to create awareness for need of sanitation and its relation with health and to bring the behavioural change for healthy sanitation practices. Along with many components construction of household, community, or public toilets is a major component.[23,24,25]

In this programme, funding is provided for construction of toilets at households and in schools. Funds are also driven from programme Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, Swachh Bharat Kosh, Income-tax Act, Corporate Social Responsibility, etc., There are technological innovations through research and development activities for both toilets and solid liquid waste management.[26]

District Primary Education Program (1994)

This programme was started to attain the universalization of primary education by rejuvenating the primary education system. Under this DPEP scheme civil works is centrally sponsored such as construction and repair of school building. Construction of toilets and provision of water supply were also included but cost for is limited.[27] District Primary Education Program is renamed as Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan in 2000–2001.

Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) – Basically this programme launched by Central Government of India with the aim for universalizing elementary education in 2001 in the partnership with state Governments and Local Self Governments. Civil works is one of the major areas of interventions in SSA. Facilities are planned to create child-friendly environment in the school, such as provision of safe drinking water under Accelerated Rural Water Supply Program and a sanitary provision in schools is under Total sanitation Campaign. This also supports social and gender equity.[28] Challenges in providing safe drinking water facilities and functional clean toilets for girls and boys were observed during starting period.[29,30]

On evaluation of SSA programme in 2010, on an average 82% of the schools had common toilet facilities and 51% of the schools had separate toilets for girls in many states. There was significant improvement in drinking water facilities up to 90%.[31]

Evaluation report of 2019 noted that Swacch Vidyalaya initiative taken in 2014 under the flagship of SSA, All surveyed schools have toilets for both gender, while 96% schools have drinking water facility. Targets for infrastructure regarding provision of drinking water and sanitary facilities by SSA have been achieved more or less. However their functionality especially that of the toilets cleanliness and maintenance is challenging. On sample survey, near about half of the schools failed to maintain these facilities as functional.[32]

Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan – This national campaign was launched in 2014 by the Ministry of Human Resource Development to provide functioning and well maintained WASH facilities in every school in India along with ensuring the development of healthy school environment with hygiene behaviours. The technical improvement and capacity building of workforce were implanted to promote conditions within the school as well practices of children.[28]

Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission (RGNDWM)

Government of India introduced the Accelerated Rural Water Supply Programme (ARWSP) in 1972–1973 with the aim to assist the states and Union Territories for accelerating the coverage of drinking water supply. In 1986, this programme was launched through Technology Mission of Drinking Water and Related Water Management as National Drinking Water Mission (NDWM). In 1991, it was renamed as the Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission (RGNDWM).[33]

The state governments implementing the rural water supply programme under the Minimum Needs Programme. The central government providing assistance to augment efforts of state governments under Accelerated Rural Water Supply Programme.[33,34]

This programme is launched in 1991 in collaboration between UNICEF, RGNDWM and IRC and beginning in three states of country (Jharkhand, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka)[33]

Assessment Survey by Planning commission in 2010 for RGNDWM recommended –

Village Water and Sanitation Committees are non-functional and poor involvement of women, the first step to rejuvenate these committees.

Need to build the capacity of members by engaging the specialist or professional and experienced agencies, by conducting training programmes for Panchayat members including rainwater harvesting structures.

Focussed and sustained IEC campaigns to educate and encourage the communities, including women for enthusiastic participation in all aspects of the programme.

Designing state-specific plans with continuous monitoring and evaluation of water supply and sanitation schemes to ensure effectiveness and long-term sustainability.

Nirmal Gram Puraskar, that is, Clean Village Award mandates functional toilets in all schools. The school should have separate toilets for boys and girls.[35]

National Water Policy – Government of India formulated this policy in 1987 and then it is reviewed for achievements in 2002 and revised its objectives in 2012. Water is provided under this policy to rural and urban settings including academic institutions, Water availability is less as compare to current demand hence enhancing the water available for use through various innovative practices such as harvesting and conservation of are the core component of this policy.[36]

National Rural Drinking Water Programme (2009): It was launched under Bharat Nirman by UPA Government to ensure safe drinking water supply through hand-pumps and/or piped water supply to whole communities. This programme was framed after merging the three other programmes on Accelerated Rural Water Supply Programme-ARWSP; National Rural Water Quality Monitoring & Surveillance and Swajaldhara.[36,37,38,39]

Programmes in India though started with small goals of providing infrastructure regarding WASH in the community, but later on their goals and strategies expanded towards holistic approach [Figure 3]. SSHE broadened the focus on hygiene education and involved the other sectors of the society by running community mobilization projects by involving teachers and community leaders. SWASTHH programmes worked for raising the community ownership and focussed on reaching to difficulty to reach population and marginalized sectors to improve WASH practices. Community participation for every step from implementation, and operation up to maintenance needed training of local leaders and hence training manual was prepared. Total sanitation campaign or NBA also widened the attention for women safety along with health. SSA tried to create child-friendly environment in the school regarding safe drinking water and sanitary facilities but many schools failed to maintain the facilities. India undertook an assessment (WaterAid) during 2016, across nine states (453 schools in 34 districts) to take review WASH services which included provision of infrastructure, functionality and utilization and awareness level of hygiene among the school students and staff.[40] About 15% schools were providing unsafe drinking water, 50% were lacking water storage facility and 10% schools reported shortage of water during summer season.

Figure 3.

Programs for improving water, sanitation and hygiene practices in schools (India)

About 95% schools had functional toilets but running water only in 35% schools and 15.2% of students reported that they never use toilets during school hours. Three fourth schools were having separate sanitary facility for boys and girls. Regarding hygiene facilities, 31% of schools were lacking in hand washing stations outside the toilet. 33% of schools were lacking of running water and half did not have soap for hand washing near toilets. Half of the schools were deficient in menstrual hygiene management facility which leads to poor attendance of girls in school.[40] Stakeholders from primary health care system can be involved to promote safe WASH at school level. Currently, school health check-up is done by medical officer and team under the School Health Services. During this check-up PHC team can conduct the awareness programme to promote safe WASH practices. This will be helpful to motivate children from rural communities to adopt healthy WASH practices and to maintain consistency in habits. To assess the impact of WASH intervention in schools, survey conducted in different schools by various research team. It was observed that provision of infrastructure is though satisfactory, consistent utilization of facilities interrupted due to poor maintenance and traditional practices among the community. Whereas increase in school attendance was observed in those schools where WASH practices improved in a better way than previous years.[41,42,43]

Conclusion and Recommendations

WASH secures children safety in health, quality of life, academic performance by improving the attendance. Various steps are taken by Government of India, UNICEF, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare for safe WASH.

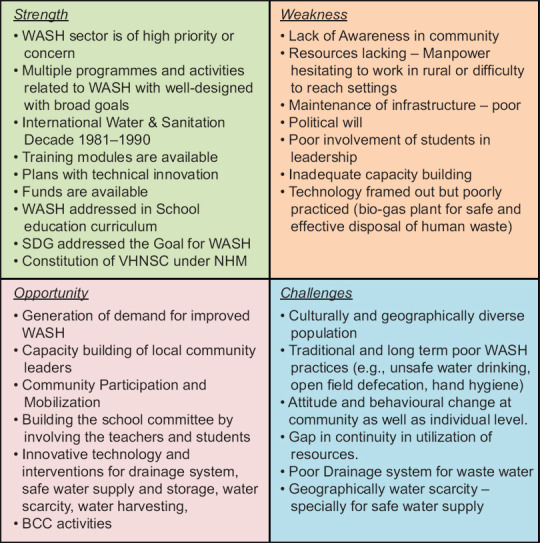

Government of India have committed to ensure the provision as well utilization of safe WASH facilities in all schools. Impact of The Swacch Bharat Mission (SBM) was observed to be a positive in disseminate WASH in schools. Single time provision of technical facilities and human development activities are not sufficient to change the deeply rooted predominant culture or practices within community especially in rural settings. But it requires continuous inspection for providing uninterrupted access to basic facilities, till the community does not feel the importance of such practices. Firstly, breaking of habits in the community for the long term and then only it will be adopted by the younger generation for life long. A person may be more likely to follow hygienic practices when one understands why and how to do it. So, intervention to improve WASH should also include the awareness programme for the community members. However, gaps and challenges should be identified at every step [Figure 4]. It is need to address the key issues identified in programme evaluation.

Figure 4.

SWOC analysis WASH programs in India

India is a nation with diverse population both in culturally and geographically consists of 65% rural population. Open defecation and dependent on open water bodies as a drinking source are predominant practices since long generations. No or poor drainage facilities promote such practices. In such scenario, it is very challenging to provide as well to utilise safe drinking water and sanitation facilities. As far as schools are concerned, such challenges widen its range [Figure 4].

There is enormous gap of understanding among huge rural and some urban people about the health and environmental hazards due to poor sanitation, such as water bodies pollution and soil pollution. Even people are unaware of benefits of sanitation facilities. Diarrheal diseases are highly prevalent in our nation because of such living habits. Due to religious reasons, in India sanitary latrines are socially and at family level are unacceptable. Toilets were constructed through various schemes before successful generation of demand for the same. So focus is needs to shift towards attitude and behavioural change at community as well as individual level.

Improvement of School WASH demands not only technical innovations but also capacity enhancement of school leaders, teachers, school management committees, education administrators, community stakeholders including NGOs and community-based organisations. Teachers can be motivated and trained accordingly as they play a catalytic role in such programmes.

Though construction of toilet is basic steps however, it is not enough. Maintenance of toilets is observed to be very difficult task on various programme evaluation. Provision of funds for construction is not sufficient but regular funding for maintenance of toilets at institutional level such as school is essentially required to continue the use of toilets and to develop the culture among people.

Achieving a basic level of safe WASH practices in all schools of India including rural and marginalised sector will require a robust effort. It is needed to raise not only awareness but also adopting the renewed culture of safe WASH among students, teachers, family, and ultimately in the community. Governments and community stakeholders should recognize the WASH as an essential foundation and integral element of efficient learning environment [Figure 4].

Though building infrastructure for provision of safe WASH is the first step, authorities also have a mandate to ensure its utilization and maintenance. Provision of facilities in the form of quantity such as number of tanks, taps, sinks or toilets in schools is not enough but whatever WASH services provided should meet relevant standards for continuity of its use. Quality of WASH provided in schools should be monitored by the education systems. Efficient monitoring system should be build up at the ground level by community involvement to ensure WASH in schools.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Department of Drinking Water Supply, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India-Central Rural Sanitation Programme, Total Sanitation Campaign. 2001. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 21]. Available from: https://hptsc.nic.in/crsp2001.pdf .

- 2.World Health Organization, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, Drinking-water, sanitation and hygiene monitoring. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/monitoring/coverage/en/

- 3.World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: 2017 update and SDG baselines, WHO/UNICEF, Geneva. 2017. [Last accessed on 2020 Nov 12]. Available from: https://washdata.org/report/jmp-2017-report-final .

- 4.Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Schools: Global Baseline Report 2018. New York: Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization. 2018. [Last accessed on2019 May 20]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/47671/file/JMP-WASH-in-Schools-ENG.pdf .

- 5.The First Five Yeaf Plan, A Draft Outline, Government of India, Planning Comminssion. July 1951. [Last accessed on 2021 Feb 11]. Available from: http://14.139.60.153/bitstream/123456789/7205/1/The%20First%20five%20 year%20plan%20a%20draft%20outline%20Planning%20commission%20July%201951%20CSL-IO016212.pdf .

- 6.Rao VKRV. India's first five-year plan-a descriptive analysis. Pacific Affairs. 1952;25:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.School Sanitation and Hygiene Education Symposium, The way forward construction is not enough. Symposium Porceedings &Framework for action, IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. 2004. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.washinschoolsindex.com/storage/documents/October2018/dy9D0BoyH3nSoZDMnPMt.pdf .

- 8.Guidelines of the Central Rural Sanitation Programme and Total Sanitation Campaign by the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation (2011). India Water Portal, 25 July 2011. [Last accessed on2020 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/guidelines-central-rural-sanitation-programme-and-total-sanitation-campaign-department .

- 9.India@70: India's First Nationwide Sanitation Programme In 1986 Focused on Improving Rural Sanitation. NDTV, BANEGA SWASTH INDIA. [Last accessed on2020 Dec 19]. Available from: https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/india70-indias-first-nationwide-sanitation-programme-in-1986-focused-on-improving-rural-sanitation-10640/

- 10.Guidelines of the Central Rural Sanitation Programme and Total Sanitation Campaign by the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation December, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India 2007. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://jalshakti-ddws.gov.in/sites/default/files/TSCGuidelin2007_0.pdf .

- 11.Pradhan Mantri Yojana. Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 29]. Available from: https://www.pradhanmantriyojana.co.in/nirmal-bharat-abhiyan/

- 12.Transition from Nirmal Bharat to Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 29]. Available from: https://iasscore.in/national-issues/transition-from-nirmal-bharat-to-swachh-bharat-abhiyan .

- 13.Claudia Irigoyen. India's Total Sanitation Campaign, Case Study. Center for Public Impact. August 25. 2017. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/case-study/total-sanitation-campaign-india/#stakeholder-engagement .

- 14.Towards Better Programming A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene UNICEF. Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series-No 5, September 1998. [Last accessed on2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/wash/files/Sch_e.pdf .

- 15.School Sanitation and Hygiene Education in India, Investment in Building Children's Future. 2004. [Last accessed on2020 Mar 21]. Available from: https://jalshakti-ddws.gov.in/sites/default/files/SSHE_in_India_Paper_2004.pdf .

- 16.Snel M. Thematic Overview Paper, School Sanitation and Hygiene Education. IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. 2003. [Last accessed on2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://sswm.info/sites/default/files/reference_attachments/IRC%202003%20School%20Sanitation%20and%20Hygiene%20Education. pdf .

- 17.Snel M, Ganguly S, Shordt K. School Sanitation and Hygiene Education – India, Resource Book. UNICEF and IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. 2002. [Last accessed on2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.susana.org/_resources/documents/default/2-423-snel-et-al-2002-sshe-resource-book-irc-en. pdf .

- 18.Snel M, Ganguly S, Shordt K. School Sanitation and Hygiene Education –India: Handbook for Teachers. Delft, The Netherlands: IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre. 2002. [Last accessed on2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.susana.org/_resources/documents/default/2-423-2-422-snel-et-al-2002-sshe-handbook-teachers-irc-en.pdf .

- 19.Snel M. The Worth of School Sanitation and Hygiene Education (SSHE) Case studies, IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, Delft, the Netherlands. 2004. [Last accessed on2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.joinforwater.ngo/sites/default/files/library_assets/W_VOR_E1_school_hygiene. pdf .

- 20.Renewed Focus on the Achievement of Sanitation Outcomes, Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan. Swajal Nirmal Bharat. 2012;1 Available from: https://jalshakti-ddws.gov.in/sites/default/files/swajal_nirmal_bharat_enewsletter_0.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 21.PMINDIA, Major Initiatives, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 29]. Available from: https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/major_initiatives/swachh-bharat-abhiyan/

- 22.Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin, Department of Drinking water & Sanitation, Ministry of Jal Shakti, Solid Liquid Waste Management, Government of India. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 29]. Available from: https://swachhbharatmission.gov.in/SBMCMS/slwm.htm .

- 23.Choudhary MP, Gupta H. Swachh Bharat Mission: A Step towards Environmental Protection. Conference: National Seminar on Recent Advancements in Protection of Environment and its Management Issues (NSRAPEM-2015) February 2015. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279201808_Swachh_Bharat_Mission_A_Step_towards_Environmental_Protection .

- 24.Khan MH. Swachh Bharat Abhiyan: The Clean India Mission (April 9 2017) Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2949372 . doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2949372.

- 25.Aijaz R. Swachh Bharat Mission: Achievements and challenges. Event Report, Observer Research Foundation. 19 July 2017. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.orfonline.org/research/swachh-bharat-mission-achievements-challenges/

- 26.Jangra B, Majra JP, Singh M. Swachh bharat abhiyan (clean India mission): SWOT analysis. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:3285–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development. District Primary Education Program Guidelines, India May 1995. [Last acessed on 2021 Feb 04]. Available from: http://14.139.60.153/bitstream/123456789/59/1/DPEP%20guidelines.pdf .

- 28.Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. A Programme for Universal Elementary Education, Manual for Planning and Appraisal, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of Elementary Education & Literacy April 2004. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 29]. Available from: https://seshagun.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-05/Manual_Planning_and_Apprisal.pdf .

- 29.Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA): A Critical Review of SSA 2014. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://socialissuesindia.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/ssa-report-2014.pdf .

- 30.Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan-Critical analysis. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://abhipedia.abhimanu.com/Article/IAS/MzgwNQEEQQVVEEQQVV/Sarva-Shiksha-Abhiyan---Critical-Analysis-Social-Issues-IAS .

- 31.Government of India, Planning Commission, Evaluation Report on Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Programme Evaluation Organisation. May 2010. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 20]. Available from: http://14.139.60.153/bitstream/123456789/1048/1/Evaluation%20Report%20on%20Sarva%20Shiksha%20Abhiyan.pdf .

- 32.Evaluation of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) Final Report. New Delhi: Datamation Consultants Pvt Ltd; 2019. [Last accessed on2021 Jan 20]. Available from: http://globalforum.items-int.com/gf/gf-content/uploads/2019/06/ssaevaluationreportmarch2019.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 33.Planning Commission, Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission – Report of an evaluation study by the Planning Commission (2010). India Water Portal 23 August 2011. [Last accessed on2020 Dec 01]. Available from: https://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/rajiv-gandhi-national-drinking-water-mission-report-evaluation-study-planning-commission .

- 34.Mundal P. Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 01]. Available from: https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/essay/rajiv-gandhi-national-drinking-water-mission/35001 .

- 35.Government of India, Ministry of Water Resources. National Water Policy (2012) [Last accessed on2020 Dec 03]. Available from: http://jalshakti-dowr.gov.in/sites/default/files/NWP2012Eng6495132651_1.pdf .

- 36.National Rural Drinking Water Programme, CAG Audit Report Summary, PRS LEGISLATIVE RESEARCH 30 August 2018. [Last accessed on 2021 Feb 08]. Available from: https://www.prsindia.org/content/national-rural-drinking-water-programme-22 .

- 37.Paliath S. National Rural Drinking Water Programme ‘Failed’ to Achieve Targets: Government Auditor. Here's Why?26 Nov 2018. India Spend. [Last accessed on2021 Feb 08]. Available from: https://www.indiaspend.com/national-rural-drinking-water-programme-failed-to-achieve-targets-government-auditor-heres-why/

- 38.National Rural Drinking Water Program (NRDWP). Gram Vikas Snastha (GVS), Department of Drinking Water &Sanitaion. 2015. [Last accessed on2021 Feb 08]. Available from: http://www.gvsngo.com/Pro_WaterShad_NationalRuralDrinking.php .

- 39.Jal Jeevan Mission, Department of Drinking Water &Sanitaion, Ministry of Jalshakti. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 01]. Available from: https://ejalshakti.gov.in/IMISReports/NRDWP_MIS_NationalRuralDrinkingWaterProgramme.html .

- 40.WaterAid. An assessment of School WASH infrastructure and hygiene behaviours in nine states. Status of School WASH two years after the Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan. WaterAid India. 2016. [Last accessed on2020 Dec 03]. Available from: https://www.wateraidindia.in/sites/g/files/jkxoof336/files/an-assessment-of-school-wash-infrastructure-and-hygiene-behaviours-in-nine-states.pdf .

- 41.Pandey DK, Pandey M, Dwivedi RK, Shrivastava AK. Impact assessment of WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) interventions in schools. Indian J Sci Technol. 2020;13:3315–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chard AN, Garn JV, Chang HH, Clasen T, Freeman MC. Impact of a school-based water, sanitation, and hygiene intervention on school absence, diarrhea, respiratory infection, and soil-transmitted helminths: Results from the WASH HELPS cluster-randomized trial. J Global Health. 2019;9:020402. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020402. doi: 10.7189/jogh. 09.020402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarder MA. Better WASH interventions impacted to increase school attendance in Bangladesh. SSRN. 2019. [Last accessed on2020 Dec 01]. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3319673 .