Abstract

The most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) subtype is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). It accounts for roughly 30% of all cases of NHL affecting both nodal and extra nodal sites. There are molecular subtypes of DLBCL, germinal centre subtype (GCB), and activated B-cell (ABC), based on gene expression profiling (GEP), in accumulation to distinct morphological and clinicopathological subtypes. To prognosticate patients, the International Prognostication Index (IPI) and its variants are used. In ABC type DLBCL, limited stage disease is treated with a combination of abbreviated systemic chemotherapy (three cycles) and field radiation therapy. Although advanced stage disease is treated with a full course of chemotherapy as well as novel agents (Bortezomib, Ibrutinib, Lenalidomide). In this review study, we looked at the role of multiple aspects of genetic and microenvironment changes which have effects in DLBCL tumours.

Keywords: Activated B-cell, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, germinal centre, rituximab

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the commonest non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) histologic subtype, accounting for roughly 30% of NHL instances.[1] It affects both men and women, with a small male preponderance. DLBCL can strike at any age, it develops from a mature B cell and is made up of cells that look like centroblasts or immunoblasts, two different forms of activated B cells (ABC).[2] DLBCL may arise spontaneously or as a result of the transformation of low-grade B-cell lymphomas, the most common form is B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (e.g., Richter’s transformation). DLBCL is a high-grade lymphoma that may have developed in nodal or extranodal locations, including the gastrointestinal tract, testes, thyroid, skin, breast, bone, or brain. Regardless that cervical and abdominal node involvement is the most common clinical presentation, extranodal involvement affects 40% of patients.[3] Systemic “B” symptoms (fever, weight loss, drenching, and night sweats) are seen in around 30% of patients, which is lower than in Hodgkin’s lymphoma, where “B” symptoms are present in up to 70% of patients. The significance of “B” symptoms in NHL prognosis is less evident, but they are markers of advanced disease, similar to how they are in Hodgkin’s lymphoma, where they are weak prognostic factors.

Subtypes of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

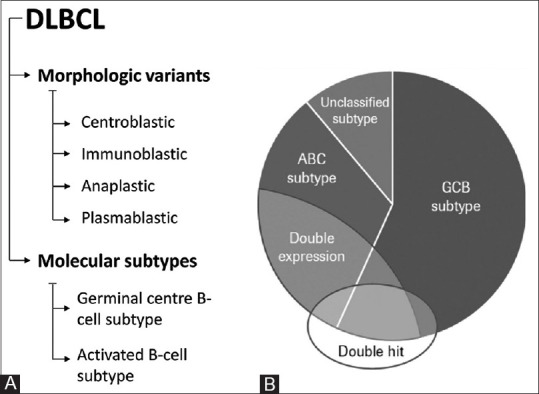

DLBCL is divided into subtypes based on their morphology and clinicopathology. Centroblastic, immunoblastic, and anaplastic morphological subtypes are the most common [Figure 1a]. Immunoblasts are large noncleaved cells with round or oval nuclei and a good prognosis, while centroblasts are also large noncleaved cells with round or oval nuclei and a good prognosis. Plasmablastic lymphoma is a morphological form that varies immunophenotypically from other lymphomas. Instead of the pan B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a) found in standard DLBCL, they express plasma cell markers (CD38, CD138). DLBCL, not otherwise specified (NOS), which are forms that do not fit within any of the four subtypes. Gene expression profiling (GEP) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) algorithms are used to categorize DLBCL into germinal centre B cell (GCB) like, non-GCB, and double hit lymphoma [Figure 1b].

Figure 1.

DLBCL classification. DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ABC: Activated B cell-like; GCB: Germinal centre B-cell; Double hit ≠ double expressors (most “double hit” cases are GCB DLBCL; most double expressors are ABC DLBCL)

Molecular classification is both prognostically and therapeutically useful. GEP or various IHC algorithms can thus divide DLBCLs into GCB like and ABC like subtypes [Table 1], with the ABC group having a substantially worse consequences than the GCB group.[2] Even after the arrival of immunochemotherapy, these molecular subtypes are linked to various outcomes.[3] Table 1 lists the distinguishing characteristics of GCB and ABC DLBCL. In ABC tumours, amplification of 18q21, which contains the BCL2 gene, was more common (18%) than in GCB tumours (5%). Majority of GCB-DLBCL cases with 18q21 amplification also had the translocation t.[14;18].

Table 1.

Characteristics of germinal center B-cell and activated B-cell-diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

| DLBCL (GCB) | DLBCL (ABC) | |

|---|---|---|

| Postulated normal counterpart | GCB cells | Post GCB cell |

| Clinical result (5-year overall survival) | 59% | 39% |

| Immunophenotype | CD10+, BCL2+, BCL6+, IRF4/MUM1− | CD10−, BCL2±, BCL6±, IRF4/MUM1+ |

| Mechanism of carcinogenesis | REL amplification | Constitutive activation of NF-κB |

| Chromosomal translocation | Gain 12q12 t (14;18) | Trisomy 3 (FOXP1) gain 3q Gain 18q21-q22 (BCL2) Deletion 6q21-q22 (BLIMP1) |

| Treatment | Normal chemoimmunotherapy (RCHOP) has a better result | Standard therapy yielded a poor result. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and ibrutinib should be added to the treatment plan |

ABC: Activated B-cell; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GCB: Germinal centre B-cell; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; OS: Overall survival; R-CHOP: Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisolone

DLBCL Classification: Old and New

An accurate diagnosis of DLBCL necessitates the correct implementation of recent classification criteria and diagnostic techniques. This methodological procedure is detailed by the World Health Organization’s (WHO), and it was codified in the “blue book” of “WHO Tumours Classification of the Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues”.[4] We may now take a pathogenetic method to DLBCL taxonomy thanks to recent developments in our understanding of the immunogenetic molecular pathways of hematopoietic and, in particular, lymphoid neoplasms. Many lymphomas are thought to be unique, with immunophenotypic profiles and recognised genetic modifications that can be recognized using modern laboratory techniques. DLBCL’s biological architecture is similar to that of NHL, an immunohistochemical algorithm distinguishes the GCB type from the ABC/non-GC type, a feature that can influence therapy options.[4,5,6] Furthermore, MYC and BCL2 co-expression establish a new prognostic “subset” (also known as “double-expressor lymphomas”).[7] MYC and BCL2 immunohistochemical co-expression which is physiologically and clinically relevant, distinguishes the category of DLBCL NOS with a bad prognosis from those with double-expressor disease.[8]

NGS studies have recently discovered that different profiles of genetic changes are significant in both GCB and non-GCB/ABC subtypes.[7] A change in histone lysine N-methyltransferase (EZH2), BCL2 translocation, and GNA13 mutation are all basic molecular fingerprints found in GCB. In non-GCB/ACB patients, mutations in genes that activate the BCR and NF-B pathways, such as CD79a, MYD88, CARD11, and TNFAIPA3, are common.[8]

There are now attempts to develop NGS-based classification of DLBCL. Notably, Schmitz et al. classified DLBCL into four categories based on DNA mutations and major fusions.[9] Whole exome sequencing was utilised to form classes of multi-centric Castleman’s disease (MCD) (concomitant presence of MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations), BN2 (BCL6 fusions and NOTCH2 mutations), N1 (NOTCH1 mutations), and EZB (EZH2 mutations and BCL2 translocations). An improved reclassification has been attempted by Wright et al. having a new category called ST2 (SGK1/TET2 mutation-driven).[10]

Novel Insights and Potential Applications in Molecular Pathogenesis

The majority belongs to the GCB subgroup and the fact that GCB DLBCLs have a better prognosis, patients with HGBL-DH/TH have a worse prognosis.[9] RNA-seq has been used to study distinct gene expression profile present in HGBL-DH/TH BCL2.[10,11] Possibility of a double-hit gene signature (DHITsig-pos) has also been looked into. Following the discovery of a genetic characteristic linked to DHITsig status DLBCLs are distinguished by a unique cell of origin with distinct mutational landscape. CD10 staining was uniformly positive in DHITsig-pos tumours, and the rest were MUM1 (IRF4)-negative. The DHITsis-pos tumours had higher expression of genes indicating cell of origin from the germinal centre intermediate region. Along with the predicted enrichment of mutations in MYC and BCL2, DHITsig-pos tumours had more mutations involved in chromatin modification like missense mutation in EZH2, truncating mutation in CREBBP. and TP53, DEAD-box helicase 3 X-linked (DDX3X) and lysine methyltransferase 2D (KMT2D) mutation.[11,12,13]

These new molecular insights have enabled rational patient management based on genetic data and on-going work on novel treatment approaches.[6,14,15,16] Controlling chromatin state is critical for mature B cell development and differentiation, and it is being investigated extensively for therapeutic purposes. A change of mutations are seen in genes involved in chromatin control and normal B-cell growth in B-cell tumours.[17,18,19] EP300 and CREBP, in addition to histone methylators like KMT2D, EZH2, and SUZ12 are important acetylation regulators that control gene expression.[17,18,19] In 25–30% of DLBCL cases, these genes are mutated. In human DLBCL, inactivation of CREBBP and EP300 hardly coexists, indicating that the cells need certain level of acetyltransferase activity.[20] CREBBP-mutated B cells thus require EP300’s residual activity, and consequently pharmacologic inactivation of EP300 could be a potential therapeutic approach.[21] Pharmacologic inactivation of EP300 may cause lymphoma cell death. Furthermore, the EP300 polymorphism has been found to affect disease progression by reducing the acetylation/deacetylation balance in the tumour niche.[22]

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and extracellular vesicles are produced by tumour apoptotic cells in patients having solid and haematological malignancies.[23,24,25,26] DLBCL also has cfDNA.[27,28] The existence of somatic mutations representative of tumour biology, which are absent in normal cells, distinguishes circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) from other cfDNA.[29] In DLBCL patients, liquid biopsy has been utilised to genotype and assess limited residual disease.[11,30] Kurtz et al.[13] discovered that ctDNAhigh DLBCL has a prognostically unfavourable prognosis. Liquid biopsy is quickly becoming a tool for predicting prognosis in haematological malignancies.[31,32]

Tumor Microenvironment and Angiogenesis: New Treatment Avenues?

Solid and haematological neoplasms spread and advance in a series of vicious loops that feed into the tumoral environment. As a result of this reciprocal cycle, as well as a number of paracrine and external stimuli, angiogenesis and immunosuppression are described as simultaneous processes.[32] DLBCL and lymphoproliferative disorders are no exception. Clinical studies are essential to confirm the subtypes that would show advantage from anti-angiogenic and milieu-targeting strategies.

There have been numerous pieces of persuasive evidence highlighting the influence of the DLBCL niche fostering a favourable stromal environment for cancer cells.[33,34] However, the occurrence of immunological and inflammatory cells is widely established in haematological malignancies and DLBCL causes tumour growth and invasion to differ.[35,36,37] In assessing the progression of DLBCL, it is vital to look at the tumour microenvironment. In DLBCL, different components of the microenvironment, such as mast cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), are taken into account to create several associations among prognostic importance, stage-related tumour progression, and treatment outcome differences.[38,39]

Angiogenesis is essential in the progression and prognosis of lymphomas, there are more than 40 lymphoproliferative diseases in this group.[40,41]

The current state of knowledge about the critical mechanisms that promote angiogenesis and facilitate immunosuppression during DLBCL growth, development, and drug sensitivity calls for further research.[42,43,44]

High levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and microvessel density (MVD) have long been known as independent indicators of poor treatment response and survival.[45,46] In DLBCL, antiangiogenesis treatment with bevacizumab with R-CHOP in DLBCL was found to be toxic.[47] An agent in advanced clinical testing in DLBCL, Lenalidomide has antiangiogenic activity, due to its property of inhibition of endothelial cell function.[48,49] FDA-approved PDE4 inhibitor, Roflumilast, has been shown to supress microvessel density in the tumor microenvironment in cell line.[50] Decreased VEGF-A secretion is probably responsible for this function.

MicroRNA, VEGF Expression, and Increased Vascularization: Linked to Prognosis

Existence of more undeveloped vessels in DLBCL relative to follicular lymphoma (FL) has been demonstrated.[51] The MVD of ABC DLBCL CD5+ was more than that of GCB DLBCL.[52] In contrast to the CD5- subgroup, MVD was higher in CD5+ DLBCL.[53]

Increased VEGF expression is linked to progression of indolent B-cell lymphoma to aggressive DLBCL, as well as weak prognostic subgroups in DLBCL.[54]

Intensity of VEGF, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 expression in DLBCL cells corresponds with the average MVD.[55] In other DLBCL studies, there was no connection between MVD and VEGF expression.[56]

In a meta-analysis of eight trials including 670 participants, positive VEGF expression in lymph nodes and blood-circulating lymphocytes was linked to shorter survival in newly diagnosed DLBCL patients.[57] A high serum VEGF level was linked to a worse prognosis in another study of 149 newly diagnosed DLBCLs.[58]

Patients who were VEGF-A and VEGFR-1 negative had an improved overall survival rate than those who were VEGF-A and VEGFR-1 positive.[59] The VEGFR-2 gene polymorphism has been connected to a better prognosis in DLBCL patients.[60]

A connection was found with improved expression of pro-angio miR-126 and miR130a, as well as anti-angio miR-328, and the non-GCB subtype.[61] Lupino et al. published on overexpressed SPHK1 in DLBCL.[64]

Diagnosis and Staging Workup

DLBCL diagnosis is carried out with morphological interpretation using haematopathology expertise and range of molecular investigations.[62]

For diagnosis of DLBCL the optimal method is excision biopsy which allows for nodal architecture assessment and also provides adequate material for phenotypic and molecular studies. Those in whom a surgical approach is would entail excessive risk or is impractical a Needle-core/endoscopic biopsies should be used. Fine-needle aspirate, however, cannot be used on a sole basis for a diagnosis. Morphological diagnosis has to be confirmed by immunophenotypic investigations. These maybe IHC or flow cytometry or a grouping of both techniques with panels designed to confirm B-cell lineage.[63]

To differentiate between GCB, non-GCB, and double hit lymphomas, an immunophenotyping panel with CD20, CD3, CD5, CD45, BCL2, BCL6, Ki67, IRF4/MUM1, and MYC is recommended. Patients who have MYC expression as well as BCL2 and/or BCL6 should have their MYC rearrangement tested using FISH.[64]

In certain cases, additional markers like CD30, CD138, EBV, HHV8, and ALK1 may help determine the subtype. All differential diagnoses for DLBCL are shown in [Table 2]. Full blood counts, a metabolic profile that involves renal and liver function checks, electrolytes (potassium, phosphate, calcium), uric acid, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are all used to determine a patient’s suitability for cytotoxic chemotherapy, organ reserves/involvement, early indication of tumour lysis, and tumour burden. Patients with proof of BM positive disease on PET/CT may be an exception, as the latter’s sensitivity and precision for evaluating BM involvement reaches 88% and 98%, respectively. Gold standard for staging is now endorsed as fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)/computed tomography (CT) scan.[65]

Table 2.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma differential diagnosis

| Entity | Clinical features | Morphology | Immunophenotype | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | Adult, nodal, often localized | Large cell, prominent nucleoli, basophill cytoplasm | Pan B-cell antigens (CD 19, CD20 CD79a, sIg+CD10±, BCL2±, BCL6±) | BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements common |

| Burkit | Children > Adult Extranodal > nodal Widespread disease | Medium-sized pleomorphic cells, several nucleoli and a starry sky pattern | CD 10+, CD20+, BCL6+, BCL2- | t (8;14), t (2;8), t (8;22), no BCL2 or BCL6 translocations |

| ALCL | ALK+, young age ALK−, older adults | Large cells, horseshoe nuclei, abundant cytoplasm | CD30+, one or more T-cell antige, no B-cell antigen | t (2;5) in ALK+ |

| Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | Extralymphatic involvement, bimodal peak and contiguous involvement | Reed-Sternberg cells and their variants in inflammatory background | CD15+, CD30+, CD20±, CD3−, CD45− | No single cytogenetc abnormality is diagnostic |

| Mantle cell Lymphoma | Middle-aged and elderly, prominent extranodal involvement, widespread disease | Medium-to-large cells, scant cytoplasm | CD5+, CD20+, CD10−, BCL2+, cyclin D1+, sIg+ | t (11;14) |

ALK: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ALCL: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Patients harbouring HIV infection should obtain the same treatment as HIV-negative patients.[62] Patients having hepatitis B who receive entecavir have substantially lower reactivation rates with chemoimmunotherapy. Cerebrospinal fluid tests may be reserved for patients having extra nodal involvement. Involvement of particular sites such as epidural, paranasal, bone/bone marrow, testis, and HIV lymphoma are all linked with high LDH and a high score of International Prognostic Index (IPI). Due to the impending use of anthracyclines, a 2D echo or multi-gated acquisition scan should be performed.

Therapy

DLBCL treatment choices are determined by whether the disease is localised (Ann Arbor Stage I, II) or advanced (Ann Arbor Stage III, IV).

Limited stage disease (Ann Arbor Stage I or II)

Limited stage DLBCL is characterised as a type of cancer that can be limited within a single irradiation area and accounts for 30–40% of DLBCL patients. Most of the patients achieve cure within six to eight cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) chemotherapy. Primary refractory disease is found in as many as 10–15%. Additionally, 20–30% of patients relapse.[66] This has led to work constantly on the bettering of the therapy. FLYER clinical trial data advocate sparing of two cycles of CHOP, with Rituximab continued over six cycles. This abbreviated therapy was found to have excellent clinical outcomes comparable to the standard six cycles of R-CHOP. In this trial, 592 patients having “low risk” stage I/II DLBCL, four cycles of CHOP had progression-free survival of 96% compared to 94% seen with six cycles of CHOP. The overall survival was also higher.[67] For limited stage disease, the dose-dense “R-CHOP-14” was not found to be superior over “R-CHOP-21”.[68]

Patients with bulky (>10 cm) Stage II disease have a prognosis comparable to patients with advanced (Stage III or IV) disease and should be treated similarly. Despite this aggressive approach, survival rates for patients having bulky disease remain inferior to patients without bulky disease, indicating the need for trials aimed specifically at this group.[69]

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, advanced stage (Ann Arbor Stage III or IV)

Advanced stage DLBCL patients account for 60–70% of DLBCL instances. The treatment of these should be custom-made to their subtypes. In the preceding two decades, the standard upfront treatment of advanced-stage DLBCL has continued to be R-CHOP. With a cure rate of up to 60% in de novo DLBCL.[70] GCB DLBCL, as defined by GEP and IHC algorithms, is known to have a robust prognosis after standard RCHOP treatment. Those with ABC type DLBCL or double hit DLBCL have deplorably high relapse rates and consistently have poor survival post treatment. Hence, multiple attempts have been made to improve the R-CHOP backbone. This includes testing a higher dose intensity administered every 14 days as compared to the traditional 21-day cycle; other by adding type II CD20 monoclonal antibodies like Obinutuzumab or dose-dense rituximab.[71,72,73] But so far no effort translated better patient outcomes, especially for those with relapsing or non-responders.

Patients with double-hit DLBCL are candidates for more severe chemotherapy regimens (e.g., dose adjusted (DA) EPOCH-R (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab)) due to high rates of relapse and poor survival following standard RCHOP treatment. According to recent studies DA-EPOCH-R group had a longer progression-free survival (PFS) than RCHOP but no overall survival (OS) advantage was reported.[74]

Relapsed/Refractory Disease

Patients with chemotherapy-sensitive relapsed aggressive NHL, one multicentre randomised trial (PARMA randomised controlled trial) compared autologous HDT/ASCR with consolidation chemotherapy.[74] Autologous hematopoietic cell transplant resulted in substantially higher rates of event-free survival (46% vs. 12%, P = 0.001) and overall survival (53% vs. 32%, P = 0.038) in follow-up of 5 years. When rituximab is given to second-line chemotherapy, full response rates are suggestively higher than in previous studies using second-line chemotherapy without rituximab.[74]

In chemo-sensitive patients, an international randomised intergroup study compared R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) to R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin) followed by ASCT and found no major differences in the outcome (CORAL study).[75] In patients experiencing relapse a year after diagnosis, event-free survival is not affected by prior rituximab treatment. Those with early relapses after rituximab-containing first-line therapy are having no difference with R-ICE and R-DHAP and have a poor prognosis.

Angiogenesis and VEGF Expression: Response to Therapy

In immunodeficient mice implanted with human DLBCL, treatment with human anti-VEGFR-1, reduced the tumour mass by 50%. While human VEGFR-2 inhibition had no antitumor effect.[75] DLBCL patients given anthracycline-based chemotherapy, had no link between augmented MVD and expression of VEGF in tumour cells. Furthermore, patients with DLBCL expressing higher levels of VEGF and VEGFR-1 had an improved survival rate and longer progression free survival.

In DLBCL patients high serum VEGF levels were linked to poor prognosis.[76] Furthermore, high MVD predicts weak prognosis in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. In untreated DLBCL, bevacizumab prevents tumour development when used alone or in conjunction with chemotherapy.[47] Angiogenesis can be more common in violent subtypes of B-cell lymphomas than in indolent subtypes. Nevertheless, lot of patients do not respond or reap only minor benefits. These new results, however, could be exploited therapeutically for relapsed/refractory patients and in extra nodal dissemination in the future.

Conclusion

DLBCL, with its numerous morphological and clinicopathological subtypes, is the most common NHL. For molecular risk assessment, GEP and IHC algorithms are used to classify DLBCL into GCB DLBCL and nongerminal centre B cell lymphoma, as well as to identify double hit DLBCL. This molecular classification not only predicts prognosis but also directs a doctor in guiding the treatment plan. New emerging classifications may add a spin to grim tale of DLBCL treatment. Addition of immunotherapy in treatment of DLBCL has defined a new standard of care. Integrating these agents early on, when patient has a more preserved immune health and using improved strategies to pick up suboptimal treatment responses may meaningfully transform the approach to upfront management. These new findings could hint to DLBCL’s weaker point, which could be utilised therapeutically in the relapsed/refractory context and in extranodal dissemination in the future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sehn LH, Scott DW, Chhanabhai M, Berry B, Ruskova A, Berkahn L, et al. Impact of concordant and discordant bone marrow involvement on outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1452–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, Fisher RI, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1937–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenz G, Wright G, Dave S, Xiao W, Powell J, Zhao H, et al. Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2313–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjö LD, Poulsen CB, Hansen M, Møller MB, Ralfkiaer E. Profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry: Identification of prognostic subgroups. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:501–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solimando AG, Ribatti D, Vacca A, Einsele H. Targeting B-cell non Hodgkin lymphoma: New and old tricks. Leuk Res. 2016;42:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reagan PM, Davies A. Current treatment of double hit and double expressor lymphoma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017:295–7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitz R, Wright GW, Huang DW, Johnson CA, Phelan JD, Wang JQ, et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;12:1396–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright GW, Phelan JD, Coulibaly ZA, Roulland S, Young RM, Wang JQ, et al. A probabilistic classification tool for genetic subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma with therapeutic implications. Cancer cell. 2020;13:551–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson L. CtDNA—Identifying cancer before it is clinically detectable. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:372. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi D, Diop F, Spaccarotella E, Monti S, Zanni M, Rasi S, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma genotyping on the liquid biopsy. Blood. 2017;129:1947–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-719641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtz DM, Scherer F, Jin MC, Soo J, Craig AF, Esfahani MS, et al. Circulating tumor DNA measurements as early outcome predictors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2845–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheah C, Fowler N, Wang M. Breakthrough therapies in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:778–87. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilly H, Da Silva MG, Vitolo U, Jack A, Meignan M, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v116–25. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayyappan S, Maddocks K. Novel and emerging therapies for B cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasqualucci L, Trifonov V, Fabbri G, Ma J, Rossi D, Chiarenza A, et al. Analysis of the coding genome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:830–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasqualucci L, Dominguez-Sola D, Chiarenza A, Fabbri G, Grunn A, Trifonov V, et al. Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2011;471:189–95. doi: 10.1038/nature09730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R. Genetics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;131:2307–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-764332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer SN, Scuoppo C, Vlasevska S, Bal E, Holmes AB, Holloman M, et al. Unique and shared epigenetic programs of the CREBBP and EP300 acetyltransferases in germinal center B cells reveal targetable dependencies in lymphoma. Immunity. 2019;51:535–47.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Ding N, Wang X, Mi L, Ping L, Jin X, et al. EP300 single nucleotide polymorphism rs20551 correlates with prolonged overall survival in diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowley E, Di Nicolantonio F, Loupakis F, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsy: Monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:472–84. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russano M, Napolitano A, Ribelli G, Iuliani M, Simonetti S, Citarella F, et al. Liquid biopsy and tumor heterogeneity in metastatic solid tumors: The potentiality of blood samples. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01601-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krebs M, Solimando AG, Kalogirou C, Marquardt A, Frank T, Sokolakis I, et al. miR-221-3p regulates VEGFR2 expression in high-risk prostate cancer and represents an escape mechanism from sunitinib in vitro. J Clin Med. 2020;9:670. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pantel K, Alix-Panabières C. Liquid biopsy and minimal residual disease—latest advances and implications for cure. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:409–24. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Lernia G, Leone P, Solimando AG, Buonavoglia A, Saltarella I, Ria R, et al. Bortezomib treatment modulates autophagy in multiple myeloma. J Clin Med. 2020;9:552. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leone P, Buonavoglia A, Fasano R, Solimando AG, De Re V, Cicco S, et al. Insights into the regulation of tumor angiogenesis by micro-RNAs. J Clin Med. 2019;8:2030. doi: 10.3390/jcm8122030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larrabeiti-Etxebarria A, Lopez-Santillan M, Santos-Zorrozua B, Lopez-Lopez E, Garcia-Orad A. Systematic review of the potential of MicroRNAs in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:144. doi: 10.3390/cancers11020144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder M, Kircher M, Hill A, Daza R, Shendure J. Cell-free DNA comprises an in vivo nucleosome footprint that informs its tissues-of-origin. Cell. 2016;164:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K, Goodman S, Li M, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14:985–90. doi: 10.1038/nm.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solimando AG, Da Vià MC, Cicco S, Leone P, Di Lernia G, Giannico D, et al. High-risk multiple myeloma: Integrated clinical and omics approach dissects the neoplastic clone and the tumor microenvironment. J Clin Med. 2019;8:997. doi: 10.3390/jcm8070997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruan J, Leonard JP. Targeting angiogenesis: A novel, rational therapeutic approach for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:679–81. doi: 10.1080/10428190902893835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciavarella S, Vegliante M, Fabbri M, De Summa S, Melle F, Motta G, et al. Dissection of DLBCL microenvironment provides a gene expression-based predictor of survival applicable to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2363–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinugasa Y, Matsui T, Takakura N. CD44 expressed on cancer-associated fibroblasts is a functional molecule supporting the stemness and drug resistance of malignant cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment. Stem Cells. 2014;32:145–56. doi: 10.1002/stem.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frassanito MA, Desantis V, Di Marzo L, Craparotta I, Beltrame L, Marchini S, et al. Bone marrow fibroblasts overexpress miR-27b and miR-214 in step with multiple myeloma progression, dependent on tumour cell-derived exosomes. J Pathol. 2019;247:241–53. doi: 10.1002/path.5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicholas NS, Apollonio B, Ramsay AG. Tumor microenvironment (TME)-driven immune suppression in B cell malignancy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2016;1863:471–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedström G, Berglund M, Molin D, Fischer M, Nilsson G, Thunberg U, et al. Mast cell infiltration is a favourable prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:68–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai Q-C, Liao H, Lin S-X, Xia Y, Wang X-X, Gao Y, et al. High expression of tumor-infiltrating macrophages correlates with poor prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2317–22. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kini AR. Angiogenesis in leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2004;121:221–38. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-7920-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribatti D, Nico B, Ranieri G, Specchia G, Vacca A. The role of angiogenesis in human non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Neoplasia. 2013;15:231–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.121962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shain K, Dalton W, Tao J. The tumor microenvironment shapes hallmarks of mature B-cell malignancies. Oncogene. 2015;34:4673–82. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buggy JJ, Elias L. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and its role in B-cell malignancy. Int Rev Immunol. 2012;31:119–32. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.664797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fornecker L-M, Muller L, Bertrand F, Paul N, Pichot A, Herbrecht R, et al. Multi-omics dataset to decipher the complexity of drug resistance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37273-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyer PN, Fu K, Greiner T, Smith L, Delabie J, Gascoyne R, et al. The stromal cell marker SPARC predicts for survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:54–61. doi: 10.1309/AJCPJX4BJV9NLQHY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stopeck AT, Unger JM, Rimsza LM, LeBlanc M, Farnsworth B, Iannone M, et al. A phase 2 trial of standard-dose cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) and rituximab plus bevacizumab for patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: SWOG 0515. Blood. 2012;120:1210–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seymour JF, Pfreundschuh M, Trnĕný M, Sehn LH, Catalano J, Csinady E, et al. R-CHOP with or without bevacizumab in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Final MAIN study outcomes. Haematologica. 2014;99:1343–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.100818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nowakowski GS, Chiappella A, Witzig TE, Spina M, Gascoyne RD, Zhang L, et al. ROBUST: Lenalidomide-R-CHOP versus placebo-R-CHOP in previously untreated ABC-type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2016;12:1553–63. doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu L, Payvandi F, Wu L, Zhang L-H, Hariri RJ, Man H-W, et al. The anti-cancer drug lenalidomide inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis via multiple inhibitory effects on endothelial cell function in normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suhasini AN, Wang L, Holder KN, Lin A-P, Bhatnagar H, Kim S-W, et al. A phosphodiesterase 4B-dependent interplay between tumor cells and the microenvironment regulates angiogenesis in B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2016;30:617–26. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Passalidou E, Stewart M, Trivella M, Steers G, Pillai G, Dogan A, et al. Vascular patterns in reactive lymphoid tissue and in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:553–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gratzinger D, Zhao S, Tibshirani RJ, Hsi ED, Hans CP, Pohlman B, et al. Prognostic significance of VEGF, VEGF receptors, and microvessel density in diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Lab Invest. 2008;88:38–47. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woźnialis N, Gierej B, Popławska L, Ziarkiewicz M, Wolińska E, Kulczycka E, et al. Angiogenesis in CD5-positive diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A morphometric analysis. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2016;25:1149–55. doi: 10.17219/acem/61427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, Weng AP, Kutok JL, Aguiar RC, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2002;8:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gratzinger D, Zhao S, Tibshirani RJ, Hsi ED, Hans CP, Pohlman B, et al. Prognostic significance of VEGF, VEGF receptors, and microvessel density in diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Blood. 2007;110:53. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jørgensen JM, Sørensen FB, Bendix K, Nielsen J, Olsen M, Funder A, et al. Angiogenesis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Clinico-pathological correlations and prognostic significance in specific subtypes. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:584–95. doi: 10.1080/10428190601083241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang L, Sun JH, Quan L-N, Tian Y-Y, Jia C-M, Liu Z-Q, et al. Abnormal vascular endothelial growth factor protein expression may be correlated with poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12:605–11. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.146086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoon K-A, Kim MK, Eom H-S, Lee H, Park WS, Sohn JY, et al. Adverse prognostic impact of vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:2677–82. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2017.1300893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganjoo KN, Moore AM, Orazi A, Sen JA, Johnson CS, An CS. The importance of angiogenesis markers in the outcome of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A retrospective study of 97 patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:381–7. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim MK, Suh C, Chi HS, Cho HS, Bae YK, Lee KH, et al. VEGFA and VEGFR2 genetic polymorphisms and survival in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borges NM, do Vale Elias M, Fook-Alves VL, Andrade TA, de Conti ML, Macedo MP, et al. Angiomirs expression profiling in diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4806. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miyazaki K. Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2016;56:79–88. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.56.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ott G, Ziepert M, Klapper W, Horn H, Szczepanowski M, Bernd HW, et al. Immunoblastic morphology but not the immunohistochemical GCB/nonGCB classifier predicts outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the RICOVER-60 trial of the DSHNHL. Blood. 2010;116:4916–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lupino L, Perry T, Margielewska S, Hollows R, Ibrahim M, Care M, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signalling drives an angiogenic transcriptional programme in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2019;33:2884–97. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0478-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Müeller SP, et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: Consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3048–58. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Susanibar-Adaniya S, Barta SK. 2021 Update on diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A review of current data and potential applications on risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:617–29. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poeschel V, Held G, Ziepert M, Witzens-Harig M, Holte H, Thurner L, et al. Four versus six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy in combination with six applications of rituximab in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma with favourable prognosis (FLYER): A randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;394:2271–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lamy T, Damaj G, Soubeyran P, Gyan E, Cartron G, Bouabdallah K, et al. R-CHOP 14 with or without radiotherapy in nonbulky limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;131:174–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-793984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfreundschuh M, Murawski N, Ziepert M, Altmann B, Dreyling MH, Borchmann P, et al. Radiotherapy (RT) to bulky (B) and extralymphatic (E) disease in combination with 6xR-CHOP-14 or R-CHOP-21 in young good-prognosis DLBCL patients: Results of the 2×2 randomized UNFOLDER trial of the DSHNHL/GLA. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:7574. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: A study by the Groupe d’ Etudes des Lymphomes de l’ Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cunningham D, Hawkes EA, Jack A, Qian W, Smith P, Mouncey P, et al. Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone in patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A phase 3 comparison of dose intensification with 14-day versus 21-day cycles. Lancet. 2013;381:1817–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60313-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sehn LH, Martelli M, Trněný M, Liu W, Bolen CR, Knapp A, et al. A randomized, open-label, Phase III study of obinutuzumab or rituximab plus CHOP in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma: Final analysis of GOYA. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00900-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ohmachi K, Kinoshita T, Tobinai K, Ogawa G, Mizutani T, Yamauchi N, et al. A randomized phase 2/3 study of R-CHOP vs CHOP combined with dose-dense rituximab for DLBCL: The JCOG0601 trial. Blood Adv. 2021;5:984–93. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kewalramani T, Zelenetz AD, Nimer SD, Portlock C, Straus D, Noy A, et al. Rituximab and ICE as second-line therapy before autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed or primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2004;103:3684–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thieblemont C, Briere J, Mounier N, Voelker H-U, Cuccuini W, Hirchaud E, et al. The germinal center/activated B-cell subclassification has a prognostic impact for response to salvage therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A bio-CORAL study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4079–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aref S, Mabed M, Zalata K, Sakrana M, El Askalany H. The interplay between c-Myc oncogene expression and circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (sVEGF), its antagonist receptor, soluble Flt-1 in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Relationship to patient outcome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:499–506. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001607151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]