Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to evaluate recovery of participation in post-COVID-19 patients during the first year after intensive care unit (ICU) discharge. The secondary aim was to identify the early determinants associated with recovery of participation.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

COVID-19 post-ICU inpatient rehabilitation in the Netherlands, during the first epidemic wave between April and July 2020, with 1-year follow-up.

Participants

COVID-19 ICU survivors ≥18 years of age needing inpatient rehabilitation.

Main outcome measures

Participation in society was assessed by the ‘Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation’ (USER-P) restrictions scale. Secondary measures of body function impairments (muscle force, pulmonary function, fatigue (Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory), breathlessness (Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale), pain (Numerical Rating Scale)), activity limitations (6-minute walking test, Patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) 8b), personal factors (coping (Utrecht Proactive Coping Scale), anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), post-traumatic stress (Global Psychotrauma Screen—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), cognitive functioning (Checklist for Cognitive Consequences after an ICU-admission)) and social factors were used. Statistical analyses: linear mixed-effects model, with recovery of participation levels as dependent variable. Patient characteristics in domains of body function, activity limitations, personal and social factors were added as independent variables.

Results

This study included 67 COVID-19 ICU survivors (mean age 62 years, 78% male). Mean USER-P restrictions scores increased over time; mean participation levels increasing from 62.0, 76.5 to 86.1 at 1, 3 and 12 months, respectively. After 1 year, 50% had not fully resumed work and restrictions were reported in physical exercise (51%), household duties (46%) and leisure activities (29%). Self-reported complaints of breathlessness and fatigue, more perceived limitations in daily life, as well as personal factors (less proactive coping style and anxiety/depression complaints) were associated with delayed recovery of participation (all p value <0.05).

Conclusions

This study supports the view that an integral vision of health is important when looking at the long-term consequence of post-ICU COVID-19. Personal factors such as having a less proactive coping style or mental impairments early on contribute to delayed recovery.

Keywords: COVID-19, REHABILITATION MEDICINE, Adult intensive & critical care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study only included the most severely affected post-intensive care unit COVID-19 patients referred to inpatient rehabilitation.

This study used physical examination as well as questionnaires, which means that there was a combination of objective and subjective measurements.

Although the sample size is small, a large number of factors were studied for their effect on the course of participation recovery.

Twenty-three patients were not approached in time for consent to participate.

The lockdown and the inability to perform social and outdoor activities may have affected the total Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation score.

Introduction

In the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands about 2% of all confirmed cases needed treatment in an intensive care unit (ICU).1 2 About three-quarters of those admitted to ICU had acute respiratory distress syndrome3 and many patients were recorded as having shock, acute kidney injury, thrombotic complications and/or cardiac injury.3

Survivors of critical illness frequently experience new or worsening physical, cognitive and/or mental impairment, described as postintensive care syndrome (PICS),4 which can have long-term effects on participation and quality of life.5–7 Immediately after ICU admission, patients with COVID-19 display various physical impairments such as exertional hypoxaemia, reduced overall muscle force, shoulder problems, dysphagia and anxiety complaints.8 In the subacute phase (1–3 months after ICU discharge) 90% of the post-ICU COVID-19 patients still experience symptoms affecting at least one of the PICS domains.9 10 Due to the varying impact of severe COVID-19, patients may experience limitations in their participation in daily living, social functioning or work performance.11 12 Restrictions in participation may eventually lead to an increase in (healthcare) costs, since patients need, for example, more professional assistance in their activities of daily living (ADL) or return to work is delayed. Although impairments in various domains of functioning have been identified, any long-term effects on the recovery of participation are unclear. The effect that this new disease may have on participation, combined with the large number of COVID-19 ICU survivors, points to the need to study factors that could delay the recovery in participation of survivors after ICU discharge. Consequently, the aim of this study is to evaluate the recovery of participation of patients with COVID-19 in the first year after ICU discharge followed by inpatient rehabilitation. The secondary aim was to identify early determinants associated with recovery of participation.

Methods

Study design and participants

This prospective cohort study was performed at Adelante Zorggroep, a rehabilitation centre in the South of the Netherlands. Patients with an indication for inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation were transferred to the rehabilitation centre. The indication was determined in the hospital by a consultant in rehabilitation medicine, based on their clinical judgement of the severity of physical, mental and/or cognitive impairments.13 14 All patients (aged 18 or older) referred for inpatient rehabilitation after ICU discharge for COVID-19 were eligible to participate in the study. The exclusion criterion was not speaking or reading the Dutch language fluently. All patients received inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and psychology personalised to patient’s limitations and needs according to the Dutch guideline for post-COVID ICU rehabilitation.13 15 All participants provided written informed consent. Patients were transferred to the rehabilitation centre from seven (two academic and five regional) hospitals in the region. COVID-19 was confirmed with a SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR test.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

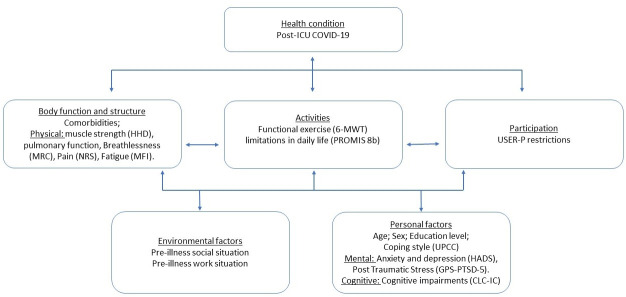

Data collection

Data were collected in the form of baseline information at admission to the rehabilitation centre (T0), through physical examination and self-administered questionnaires after 1 (T1), 3 (T2) and 12 months (T3). Since different domains of functioning can be affected by COVID-19, measurements were chosen based on an integral vision of health and included body function impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions as well as personal and social factors. These factors are derived as main domains in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) that supports the classification of health and health-related conditions and their effect on social participation (figure 1).14

Figure 1.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model and measurement instruments used. CLC-IC, Checklist for Cognitive Consequences after an ICU-admission; GPS-PTSD-5, The Global Psychotrauma Screen—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HHD, handheld dynamometer; ICU, intensive care unit; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; MRC, Medical Research Council; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; UPCC, Utrecht Proactive Coping Scale; USER-P, Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation; 6MWT, 6-minute walking test; PROMIS, Patient reported outcomes measurement information system.

Primary outcome variable

Participation in society was assessed by the ‘Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation (USER-P) restriction subscale’. This subscale consists of 11 items on restrictions in vocational, leisure and social activities. Items are rated from 0 ‘not possible’ to 3 ‘without difficulty’ and a ‘not applicable’ option. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, higher scores indicating fewer restrictions in participation.16 17

Data on age, sex, comorbidities and parameters related to critical illness were collected from the medical transfer letters (T0). Comorbidities were classed into diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, lung disease and psychiatric disorders. Parameters related to severity of the critical illness were length of ICU stay, invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) (yes/no) and duration of invasive IMV. The duration of the inpatient rehabilitation was recorded.

Physical examination

Assessment of muscle strength, functional exercise capacity and pulmonary function were part of physical examination. To measure muscle strength, a handheld dynamometer (HHD) was used18 to assess the following muscle groups: shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, wrist extension, hip flexion and knee extension, all on patient’s dominant side. HHD values were measured in Newtons and percentages of the norm compared with healthy persons of the same sex, age and weight.19 20 Severe muscle weakness was defined as <80% of the norm score. For the clinical assessment of the functional exercise capacity, the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) was used, displayed in metres and percentage of the norm.21 22 To evaluate pulmonary function Quark PFT spirometry (Cosmed, Italy) was used.23 Forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/FVC ratio were included in the analysis, displayed in percentage of the norm.

In addition, self-administered questionnaires were used. Breathlessness was assessed by the Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale, which comprises five statements that range from 0 ‘no trouble with breathlessness’ to 5 ‘I am too breathless to leave the house’.24 The Numerical Rating Scale was used for assessing pain. Patients were asked to rate their mean pain intensities in the last 7 days, ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating ‘no pain’ and 10 indicating ‘the worst imaginable pain’.25 The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) is a 20-item metric for fatigue severity. It has five dimensions: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation and reduced activity. Each item ranges from 1 ‘absence of fatigue’ to 5 ‘severe fatigue’. A total score is calculated as the sum of the subscale scores (20–100). Higher scores indicate higher levels of fatigue.26 The perceived limitations in daily life were assessed using the Patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) physical function shortform 8b. This survey contains eight questions ranging from 1 ‘unable to do’ to 5 ‘without any difficulty’.27 A web-based scoring service was used to calculate T-scores (maximum score 60.1 and mean 50.0, corresponding to the mean in the general population of the USA), whereas a higher scores indicates better physical function.28 Anxiety and depression complaints were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). A score ≥8 on either subscale was considered to be substantial anxiety or depression symptoms.29 Post-traumatic stress was assessed using the Global Psychotrauma Screen—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (GPS-PTSD-5). The regular GPS consists of 22 items, item 1–5 can be used to generate a GPS-PTDS-5 score (range 0–5), score ≥3 indicates PTSD.30 Cognitive functioning was assessed using the Checklist for Cognitive Consequences after ICU-admission (CLC-IC). The CLC-IC consists of 10 items; higher scores indicate more cognitive problems experienced in daily life (range 0–10). The CLC-IC is based on the CLCE-24.31 Proactive coping skills were assessed at T3 with the Utrecht Proactive Coping Scale (UPCC), which is a 21-item questionnaire scored on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘not competent at all’ to ‘competent’. The total score was the average for all item scores (range 1–4), where higher scores indicate higher levels of proactive coping.32 Premorbid social and work situations were collected at T1.

Statistical analyses

Results are reported as mean and SD or median and IQR depending on distribution. Recovery of participation levels over time were assessed with linear mixed-effects model for repeated measures. Patient characteristics in the domains body function, activity limitations, personal and social factors at T0 and 1 month after admission in the rehabilitation centre (T1) were added to separate models that also included time and the interaction between that covariate and time. Next, for illustrative purposes only, linear mixed-effects model analyses were stratified according to patient characteristics that were significantly associated with the course of recovery of participation levels to visualise different patterns of change over time. A p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics V.26.0 (SPSS).

Results

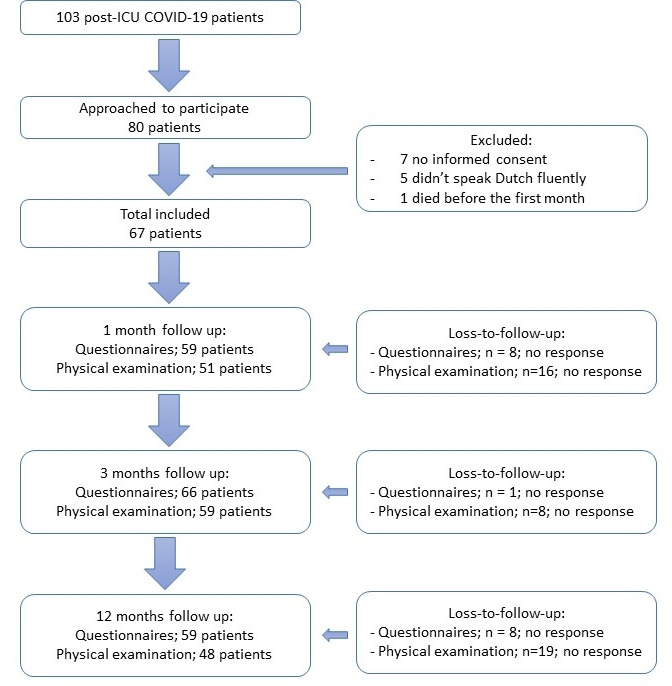

During the first COVID-19 wave between 2 April and 30 June 2020, 103 post-ICU patients were admitted for inpatient rehabilitation. Of these, 23 patients were missed since this study was part of clinical practice in a very dynamic period and 13 patients were excluded for reasons given in figure 2. The study sample consisted of 67 patients (78% male) with a median age of 62 (IQR 57–68) and a median length of stay of 20 (IQR 12-33) days in the ICU and 19 (IQR 11-31) days inpatient rehabilitation (table 1). Overall, an improvement in muscle strength and functional exercise capacity (6MWT) was found, whereas fatigue complaints and perceived limitations in daily life seem to decrease in the first year after ICU discharge (table 1).

Figure 2.

Subject recruitment flowchart. ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Overview of the baseline characteristics (T0) and the physical examination and self-administered questionnaires at T1, T2 and T3

| T0 | One month (T1) | Three months (T2) | Twelve months (T3) | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age, years; n=67; median (IQR) | 62 (57–68) | – | ||

| Sex; n=67; No. (%) | ||||

| Men | 52 (77.6%) | – | ||

| Women | 15 (22.5%) | – | ||

| Highest level of education; n=62; No. (%) | ||||

| Lower education | 42 (67.7%) | – | ||

| Higher education | 20 (32.3%) | – | ||

| Work situation; n=62; No. (%) | – | |||

| Full-time job | 26 (41.9%) | |||

| Part-time job | 10 (16.1%) | – | ||

| Retired | 18 (29.0%) | – | ||

| Not working otherwise | 8 (12.9%) | – | ||

| Comorbidities; n=67; No. (%) | – | |||

| Asthma/bronchitis | 6 (9.0%) | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (6.0%) | – | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome | 12 (17.9%) | – | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (17.9%) | – | ||

| Hypertension | 23 (34.3%) | – | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 21 (31.3%) | – | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (7.4%) | – | ||

| Depression | 4 (6.0%) | – | ||

| None of the above comorbidities | 25 (37.3%) | – | ||

| Parameters related to severity critical illness | – | |||

| Duration intensive care unit, in days; n=59; median (IQR) | 20 (12–33) | |||

| Duration IMV, in days; n=55; median (IQR) | 17 (9–24) | – | ||

| Presence of ICU-acquired weakness, n=61; No. (%) | 45 (73.8%) | – | ||

| Duration inpatient rehabilitation, days; n=67; median (IQR) | 19 (11–31) | |||

| Coping style (UPCC); n=58; mean (SD) | 3.0 (0.2) | |||

| USER-P restriction subscale* | ||||

| Work/education | – | 64.4% | 65.2% | 28.8% |

| Housekeeping | – | 74.6% | 65.2% | 45.8% |

| Mobility | – | 59.3% | 43.9% | 16.9% |

| Physical exercise | – | 79.7% | 60.6% | 50.8% |

| Going out | – | 79.7% | 24.2% | 10.2% |

| Outdoor activities | – | 54.2% | 36.4% | 16.9% |

| Leisure activities | – | 42.4% | 28.8% | 20.3% |

| Partner relationship | – | 28.8% | 24.2% | 16.9% |

| Visits to family/friends | – | 45.8% | 31.8% | 10.2% |

| Visits from family/friend | – | 45.8% | 13.6% | 8.5% |

| Telephone/PC contact | – | 15.3% | 13.6% | 11.9% |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Muscle strength | ||||

| Mean muscle force (HHD), mean (SD) | – | 75.7% (15.3) | 93.5% (24.6) | 101.4% (15.3) |

| 6MWT; mean (SD) | – | 467.8 m (91.2) | 518.3 m (102.5) | 531.0 m (86.5) |

| Percentage of predicted | 69.5% (13.7) | 76.9% (13.7) | 79.2% (10.4) | |

| Pulmonary function; mean (SD) | – | |||

| FEV1 | – | 87.5% (15.8) | 93.8% (19.9) | 93.6% (17.7) |

| FVC | – | 85.9% (16.3) | 92.8% (18.7) | 92.2% (15.6) |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 79.6% (9.1) | 77.3% (10.6) | 79.1% (11.2) | |

| Self-administered questionnaires: | ||||

| Breathlessness (MRC); median (IQR) | – | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| Pain (NRS); median (IQR) | – | 2.0 (1.0–3.5) | 2.0 (1.5–5.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) |

| Fatigue (MFI); mean (SD) | – | 58.6 (14.0) | 56.0 (15.3) | 50.8 (17.6) |

| Perceived limitations in daily life (PROMIS 8b); mean (SD) | – | 34.8 (7.4) | 39.2 (6.9) | 44.8 (8.0) |

| Anxiety (HADS-anxiety); median (IQR) | – | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 2.0 (0.5–6.0) |

| Exceeded anxiety cut-off ≥8 | – | 7/57 (12.3%) | 11/66 (16.7%) | 10/59 (16.9 %) |

| Depression (HADS depression); median (IQR) | – | 2.0 (1.5–6.0) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Exceeded depression cut-off ≥8 | – | 10/59 (16.9%) | 13/66 (19.7%) | 10/59 (16.9%) |

| Post-traumatic stress (GPS-PTSD-5); median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | |

| Exceeded PTSD cut-off ≥3 | 5/59 (8.5%) | 8/66 (12.1%) | 3/59 (5.1%) | |

| Cognitive impairments (CLC-IC); median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 4.0 (1.0–7.0) | 2.0 (0.0–7.0) |

Low educational level was determined as ‘primary and secondary education and post-secondary school’. High educational level was determined as ‘bachelor’s degree, master’s degree or doctorate or equivalent’.

*Restriction items values are percentages of patients who are restricted or dissatisfied.

CLC-IC, Checklist for Cognitive Consequences after an ICU-admission; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GPS, The Global Psychotrauma Screen—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HHD, handheld dynamometer; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; MRC, Medical Research Council; 6MWT, 6-minute walking test; n.a., not applicable; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PROMIS, Patient reported outcomes measurement information system; UPCC, Utrecht Proactive Coping Scale; USER-P, Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation.

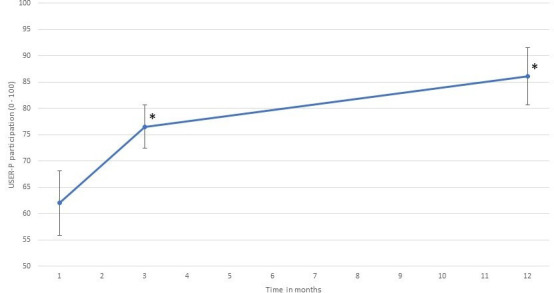

Participation restrictions improved in the first year after ICU discharge due to a COVID-19 infection (figure 3). Mean participation levels increased from 62.0 (95% CI 55.9 to 68.1), 76.5 (95% CI 71.9 to 81.1) to 86.1 (95% CI 80.6 to 91.6) at 1, 3 and 12 months, respectively. One year after ICU discharge, 50.8% of the patients still reported restrictions in physical exercise, 45.8% in performing housekeeping and 28.8% in performing leisure activities. After 1 year work is not applicable in 42.4% of all patients, which is comparable to the premorbid work situation, where 58% of all patients were employed. One year after ICU discharge 28.8% of all patients still reported restrictions in work/education. Taking into account the patients who were not working preillness, means that 50% of the preillness working patients had not fully resumed work after 1 year (table 1).

Figure 3.

The recovery of participation levels (USER-P restriction subscale) in the first year after intensive care unit discharge in post-COVID-19 patients. USER-P, Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation.

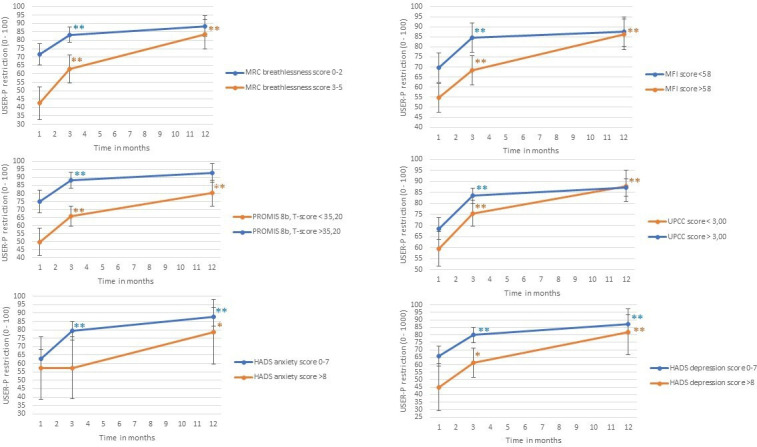

Regarding the second aim, in the ICF domain body functions, breathlessness (MRC breathlessness), regression coefficient: 0.60 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.97; p value <0.01) and fatigue (MFI), regression coefficient: 0.07 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.09; p value <0.01) were the only physical variables that influenced participation recovery over time. For the ICF domain activities, perceived limitations in daily life (PROMIS 8b) showed a different pattern in the recovery of participation restriction levels, regression coefficient: −0.11 (95% CI −0.12 to −0.05; p value <0.01). In addition, personal factors like coping style (UPCC) regression coefficient: −2.39 (95% CI −4.20 to −0.06; p value 0.01), anxiety (HADS anxiety) regression coefficient: 0.17 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.31; p value 0.03) and depression (HADS depression) regression coefficient: 0.19 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.31; p value <0.01) showed different paths in resuming the level of participation over time. Other early determinants show no significant difference in the recovery of participation (table 2).

Table 2.

Linear mixed model for covariates at T0 or T1, as an interaction between covariate and time (1, 3 and 12 months), for the recovery of participation levels

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Age | −0.03 (–0.08 to 0.02) | 0.29 |

| Sex | 0.72 (–0.32 to 1.76) | 0.17 |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.04 (–0.34 to 0.42) | 0.83 |

| Duration of inpatient rehabilitation | 0.03 (–0.00 to 0.06) | 0.07 |

| Coping style (UPCC) | −2.39 (–4.20 to –0.06) | 0.01* |

| ICU-stay specific parameters | ||

| Length of ICU stay | 0.02 (–0.01 to 0.06) | 0.21 |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation | 0.02 (–0.02 to 0.05) | 0.37 |

| ICU-acquired weakness | −0.23 (–1.31 to 0.85) | 0.67 |

| Physical examination | ||

| Muscle strength | ||

| Mean muscle force (HHD) | −0.02 (–0.06 to 0.01) | 0.18 |

| 6MWT | −0.00 (–0.01 to 0.01) | 0.65 |

| Pulmonary function | ||

| FEV1 | −0.02 (–0.06 to 0.01) | 0.16 |

| FVC | −0.03 (–0.06 to 0.00) | 0.07 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.04 (–0.02 to 0.09) | 0.24 |

| Self-administered questionnaires | ||

| Breathlessness (MRC) | 0.60 (0.23 to 0.97) | <0.01* |

| Pain (NRS) | −0.03 (–0.28 to 0.23) | 0.84 |

| Fatigue (MFI) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.09) | <0.01* |

| Perceived limitations in daily life (PROMIS 8b) | −0.11 (–0.12 to –0.05) | <0.01* |

| Anxiety (HADS-anxiety) | 0.17 (0.02 to 0.31) | 0.03* |

| Depression (HADS depression) | 0.19 (0.07 to 0.31) | <0.01* |

| Post-traumatic stress (GPS-PTSD-5) | 0.24 (–0.21 to 0.70) | 0.3 |

| Cognitive impairments (CLC-IC) | 0.09 (–0.07 to 0.24) | 0.27 |

*p<0.05.

CLC-IC, Checklist for Cognitive Consequences after an ICU-admission; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GPS, The Global Psychotrauma Screen—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HHD, handheld dynamometer; ICU, intensive care unit; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; 6MWT, 6-minute walking test; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; UPCC, Utrecht Proactive Coping Scale.

Participation levels increased significantly between 1 and 3 months and between 3 and 12 months in patients who reported more breathlessness, more fatigue or more limitations in daily life and those with a passive coping style. In contrast, patients with less breathlessness, fewer fatigue complaints, fewer restrictions in daily life and a proactive coping style showed no significant increase between 3 and 12 months (figure 4). For patients with HADS anxiety score ≥8, no differences were found in participation levels in the first 3 months, while there was significant difference in recovery of participation levels between 3 and 12 months. However, for patients with fewer anxiety complaints (HADS anxiety score ≤8) participation levels significantly improved between 1 and 3 months and between 3 and 12 months. For depressive symptoms, both groups improved significantly in participation levels between 1 and 3 months and between 3 and 12 months, although a steeper curve is seen in recovery of participation levels at 3–12 months in patients with more depressive symptoms.

Figure 4.

The influence of early levels of body function impairments, activity limitations and personal factors on the recovery of participation levels (USER-P restriction subscale). HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MRC, Medical Research Council; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; PROMIS, Patient reported outcomes measurement information system; UPCC, Utrecht Proactive Coping Scale; USER-P, Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, recovery of participation during the first year after ICU discharge in COVID-19 ICU survivors who needed inpatient rehabilitation was evaluated and the association between early levels of body function impairments, activity limitations and personal and social factors on recovery were estimated. It is seen that in the first year after ICU discharge patients were able to improve their participation levels. Nevertheless, after 1 year, there are still important limitations in daily life, mainly in resuming work, physical exercise, housekeeping and leisure activities. As early determinants for a delay in the resumption of patient’s habitual level of participation levels over the first year, higher levels of self-experienced breathlessness and fatigue complaints, more perceived limitations in daily life as well as personal factors (having a passive coping style, anxiety complaints or depression complaints) were found.

In previous Dutch studies focusing on overall post-ICU COVID-19 survivors, an average age of 61–63 was found, 69%–72% men, with a median length of stay of 18–20 days in the ICU.33 34 These demographic data seem to correspond with findings of current study, taking into account that in the first COVID-19 wave, 83% of all post-ICU COVID-19 patients were transferred to a rehabilitation centre.34 Heesakkers et al reported that in patients who survived 1 year following ICU treatment for COVID-19, physical, mental or cognitive symptoms were often reported.33 This corresponds with the findings of the current study, whereas various physical, mental and cognitive impairments were seen 1 year after ICU admission. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report differences in the resumption of participation levels in post-ICU COVID-19 patients. Mean participation levels increased to 86.1 1 year after ICU discharge. As a reference, in other patients with non-COVID-19 (ie, stroke, acquired brain injury, progressive neurological diseases, spinal cord injury and acute coronary syndrome), participation levels between 70.6 and 83.5 have been observed.35–37 In all non-COVID patient groups, patients mainly reported restrictions in work/education, housekeeping, physical exercise and performing leisure activities, which is in accordance with restrictions in participation reported in the current study.36 37

Moreover, these results showed that higher scores of self-experienced breathlessness or fatigue and more perceived limitations in daily life in the early phase of rehabilitation were associated with a delayed recovery of participation levels over the first year. Furthermore, patients with a less active coping style, those that were more anxious or reported to perceive more depressive complaints had a delayed recovery of their level of participation over the first year. For all these determinants, participation levels also appeared to be lower in the early phase of rehabilitation. These findings indicate that patients with a higher level of anxiety and those with a higher level of depression had a significantly slower improvement in participation levels during the first months, followed by a more progressive recovery, especially in the last months. In addition, patients with more breathlessness complaints, more fatigue complaints or more perceived limitations in daily life in the early phase of rehabilitation and patients with a passive coping style showed a more progressive recovery of participation levels especially in the last months. Poor baseline situation may also have provided more opportunity to improve. However, with a mean participation restriction level of 86.1 1 year after ICU discharge, the maximum score of 100 of the USER-P restriction subscale has not been reached.

Complaints of fatigue or breathlessness may be due to underlying medical problems or to the contribution of personal factors. Previous study’s showed significant recovery of respiratory function and physical performance in the first year after ICU discharge due to COVID-19. Nevertheless, patients still experience breathlessness and fatigue complaints after 1 year.38 39 Another finding in the current study was that early determinants related to the severity of the COVID-19 infection period itself (such as ICU stay-specific parameters and physical parameters as age, sex, muscle strength, functional exercise capacity and pulmonary function) did not individually explain progress in recovery of participation over time. Contrary to expectations, this may indicate that non-physical factors such as coping style, subjectively experienced physical impairments (including fatigue and breathlessness) and mental health issues (such as anxiety and depressive symptoms) seem more important to determine progress in recovering the level of participation. Previous literature on post-ICU patients indicated that critical care recovery has focused on post-ICU impairments experienced by patients. Whereas the positive aspects of recovery within the rehabilitation phase, including coping style and resilience seems to be ignored.40 41 Resilience refers to the ability to face the challenges and difficulties of life in a positive and adaptive manner, as well as the capacity to recover from an adverse event.42 Higher levels of resilience have been linked to improved mental and physical health.43 It is possible to improve the level of resilience which implies that resilience can be used to improve (emotional) well-being, with the possible consequence of improving participation levels.

Implications for clinical practice and further research

This study underlines the importance of looking at long-term consequence of COVID-19 ICU survivors with an integral vision of health. Whether identical variables can be used to identify a delay in recovery in patients who had a milder infection is currently still unclear. In this study, conclusions can be made for a selected group (with ICU admission) of patients. Extrapolation to other populations needs to be done with caution. Early detection of a passive coping style or mental impairments seems important and should therefore be included in screening during early multidisciplinary rehabilitation. Further research is needed to study the effect of early screening of a patients’ level of coping/resilience during the first months after ICU discharge. As a consequence, an early intervention to increase resilience/strengthen coping on indication could be promising to further strengthen social participation, but needs to be further studied.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is that it only included the most severely affected post-ICU COVID-19 patients referred to inpatient rehabilitation. In addition, this study used physical examination as well as questionnaires, which means there was a combination of objective and subjective measurements. It is notable that even in the most severely affected patients with COVID-19 delayed recovery of participation is associated with self-experienced physical impairments, mental impairments and coping style.

Nevertheless, some limitations of the current study need to be considered. First, sample size is limited and a number of factors were studied for their effect on the course of participation recovery. The limited sample size contributed to relatively wide CIs. The risk of type II error should therefore be considered while interpreting the data. A post-hoc power calculation revealed however that the study had 90% power to detect an effect size of 0.2 for changes in participation levels over time (alpha=0.05, mean correlation between repeated measures=0.53). Still, p values of the multiple tests of association should be interpreted cautiously, because we cannot exclude erroneous interpretations of statistical significant findings (ie, type I error). However, since our results support a certain pattern, we believe that the main conclusions of this study are solid. Second, number of variables available to describe the acute illness severity were limited. Patients referred for inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation were included in this study. Generalisation of the results to all ICU survivors needs to be performed with caution, and needs further study. Third, due to high workload on the ward, 23 patients were not approached in time for consent to participate. In our opinion, this is unlikely to have led to selection bias, but this cannot be excluded. Finally, the lockdown and the inability to perform social and outdoor activities may have affected the total USER-P score as this scale allows the rating of ‘not applicable’. Since the study and lockdown period were similar for all patients, we expect no difference in the study patients. Although it may have affected the recovery course of participation recovery for the entire patient group, it is not expected to have affected the predictors.

Conclusion

For patients admitted to an ICU for COVID-19, participation levels improves in the first year after ICU discharge. However, at 1 year after discharge, many patients still experience limitations in daily life, mainly in resuming work, physical exercise, housekeeping and leisure activities. Our results indicate that progress of recovery in participation in the first year after discharge is associated with early determinants in coping style, subjectively experienced physical impairments (breathlessness and fatigue) and mental impairments (anxiety and depression) rather than medical variables. This study supports the need for an integral perspective on health to facilitate the identification of factors that delay the recovery trajectory for participation in the first year after ICU discharge. Personal factors such as a passive coping style and more anxiety or depression complaints seem relevant to this. Rehabilitation care needs to anticipate on these topics, starting in the early rehabilitation phase of post-ICU COVID-19 care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all physiotherapist and students for their valuable contribution for collecting all data. We also thank all participants.

Footnotes

Contributors: CW, JV, BH and SJSS were responsible for the study design. The statistical analysis plan was designed by CW, SJSS and SvK. Statistical analysis was done by CW, with control of SJSS and SvK. Practical implication was done by CW, SvS and YvH. The first draft of the paper was written by CW and all coauthors reviewed and approved it for submission. CW and JV are the guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. To guarantee the confidentiality of personal and health information, only the authors have had access to the data during the study. Data are available (anonymised), but the corresponding author must be contacted to request these data. Data will be kept for 15 years.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the local medical ethics committee Zuyderland METC (METCZ20200086). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.RIVM . Actuele informatie over het nieuwe coronavirus (COVID-19). Available: https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/actueel [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- 2.NICE . COVID-19 infecties op de IC’s. Nationale intensive care Evaluatie. Available: https://www.stichting-nice.nl/COVID_rapport.pdf [Accessed 02 Jul 2020].

- 3.Tan E, Song J, Deane AM, et al. Global impact of coronavirus disease 2019 infection requiring admission to the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2021;159:524–36. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:502–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Sedrakyan A, et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: A systematic review of the literature. In: Intensive care medicine. Springer Verlag, 2005: 611–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med 2011;39:371–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtake PJ, Lee AC, Scott JC, et al. Physical impairments associated with post-intensive care syndrome: systematic review based on the world Health organization's International classification of functioning, disability and health framework. Phys Ther 2018;98:631–45. 10.1093/ptj/pzy059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiertz CMH, Vints WAJ, Maas GJCM, et al. COVID-19: patient characteristics in the first phase of Postintensive care rehabilitation. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl 2021;3:100108. 10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martillo MA, Dangayach NS, Tabacof L, et al. Postintensive care syndrome in survivors of critical illness related to coronavirus disease 2019: cohort study from a New York City critical care recovery clinic. Crit Care Med 2021;49:1427–38. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rousseau A-F, Minguet P, Colson C, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome after a critical COVID-19: cohort study from a Belgian follow-up clinic. Ann Intensive Care 2021;11:118. 10.1186/s13613-021-00910-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leite VF, Rampim DB, Jorge VC, et al. Persistent symptoms and disability after COVID-19 hospitalization: data from a comprehensive Telerehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;102:1308–16. 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Veenendaal N, van der Meulen IC, Onrust M, et al. Six-month outcomes in covid-19 ICU patients and their family members: a prospective cohort study. Healthcare 2021;9. 10.3390/healthcare9070865. [Epub ahead of print: 08 07 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FMS . COVID-19, 2022. Available: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/covid-19/startpagina_-_covid-19.html

- 14.WHO . The international Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health - ICF, 2001. Available: https://www.who.int/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

- 15.de Graaf J, Brouwers M, Post M. Behandelprogramma COVID-19 post-IC in de Medisch Specialistische Revalidatie (De Hoogstraat). Utrecht: The Netherlands; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Post MWM, van der Zee CH, Hennink J, et al. Validity of the utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:478–85. 10.3109/09638288.2011.608148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Zee CH, Visser-Meily JMA, Lindeman E, et al. Participation in the chronic phase of stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2013;20:52–61. 10.1310/tsr2001-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanpee G, Segers J, Van Mechelen H, et al. The interobserver agreement of handheld dynamometry for muscle strength assessment in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1929–34. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821f050b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews AW, Thomas MW, Bohannon RW. Normative values for isometric muscle force measurements obtained with hand-held dynamometers. Phys Ther 1996;76:248–59. 10.1093/ptj/76.3.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohannon RW. Reference values for extremity muscle strength obtained by hand-held dynamometry from adults aged 20 to 79 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:26–32. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan KS, Pfoh ER, Denehy L, et al. Construct validity and minimal important difference of 6-minute walk distance in survivors of acute respiratory failure. Chest 2015;147:1316–26. 10.1378/chest.14-1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Six minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjects. Eur Respir J 1999;14:270–4. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b06.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American thoracic Society and European respiratory Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:e70–88. 10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenton C. The MRC breathlessness scale. Occup Med 2008;58:226–7. 10.1093/occmed/kqm162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:798–804. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 1995;39:315–25. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng D, Laurel F, Castille D, et al. Reliability, construct validity, and measurement invariance of the PROMIS physical function 8b-Adult short form v2.0. Qual Life Res 2020;29:3397–406. 10.1007/s11136-020-02603-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.HealthMeasures scoring service powered by assessment CenterSM. Available: https://www.assessmentcenter.net/ac_scoringservice [Accessed 20 Feb 2021].

- 29.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77. 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olff M, Bakker A, 2016. Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS); User guide september 2021. Available: https://nl.global-psychotrauma.net/gps [Accessed 02 Feb 2022].

- 31.van Heugten C, Rasquin S, Winkens I, et al. Checklist for cognitive and emotional consequences following stroke (CLCE-24): development, usability and quality of the self-report version. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2007;109:257–62. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bode C, Thoolen B, Ridder D. Het meten van proactieve copingvaardigheden: Psychometrische eigenschappen van de Utrechtse Proactieve coping Competentie lijst (UPCC). Psychol en Gezondh 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heesakkers H, van der Hoeven JG, Corsten S, et al. Clinical outcomes among patients with 1-year survival following intensive care unit treatment for COVID-19. JAMA 2022;327:559. 10.1001/jama.2022.0040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Gassel RJJ, Bels JLM, Raafs A, et al. High prevalence of pulmonary sequelae at 3 months after hospital discharge in mechanically ventilated survivors of COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:371–4. 10.1164/rccm.202010-3823LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Mierlo ML, van Heugten CM, Post MWM, et al. Quality of life during the first two years post stroke: the Restore4Stroke cohort study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;41:19–26. 10.1159/000441197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Graaf JA, van Mierlo ML, Post MWM, et al. Long-term restrictions in participation in stroke survivors under and over 70 years of age. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:637–45. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1271466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mol TI, van Bennekom CA, Schepers VP, et al. Differences in societal participation across diagnostic groups: secondary analyses of 8 studies using the Utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;102:1735–45. 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Prediletto I, et al. Health-related quality of life profiles, trajectories, persistent symptoms and pulmonary function one year after ICU discharge in invasively ventilated COVID-19 patients, a prospective follow-up study. Respir Med 2021;189:106665. 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bels JLM, van Gassel RJJ, Timmerman L. One year respiratory and functional outcomes of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 survivors: a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206:777–80. 10.1164/rccm.202112-2789LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maley JH, Brewster I, Mayoral I, et al. Resilience in survivors of critical illness in the context of the survivors' experience and recovery. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:1351–60. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-782OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haines KJ, Hibbert E, Leggett N, et al. Transitions of care after critical Illness-challenges to recovery and adaptive problem solving. Crit Care Med 2021;49:1923–31. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinhardt M, Dolbier C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J Am Coll Health 2008;56:445–53. 10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schure MB, Odden M, Goins RT. The association of resilience with mental and physical health among older American Indians: the native elder care study. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 2013;20:27–41. 10.5820/aian.2002.2013.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. To guarantee the confidentiality of personal and health information, only the authors have had access to the data during the study. Data are available (anonymised), but the corresponding author must be contacted to request these data. Data will be kept for 15 years.