Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the awareness, implementation and difficulty of behavioural recommendations and their correlates in officially ordered domestic isolation and quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Online retrospective cohort survey conducted from 12 December 2020 to 6 January 2021 as part of the Cologne–Corona Counselling and Support for Index and Contact Persons During the Quarantine Period study.

Setting

Administrative area of the city of Cologne, Germany.

Participants

3011 infected persons (IPs) and 5822 contacts over 16 years of age who were in officially ordered domestic isolation or quarantine between 28 February 2020 and 9 December 2020. Of these, 60.4% were women.

Outcome measures

Self-developed scores were calculated based on responses about awareness and implementation of 19 behavioural recommendations to determine community-based and household-based adherence. Linear regression analyses were conducted to determine factors influencing adherence.

Results

The average adherence to all recommendations, including staying in a single room, keeping distance and wearing a mask, was 13.8±2.4 out of 15 points for community-based recommendations (CBRs) and 17.2±6.8 out of 25 points for household-based recommendations (HBRs). IPs were significantly more adherent to CBRs (14.3±2.0 points vs 13.7±2.6 points, p<0.001) and HBRs (18.2±6.7 points vs 16.5±6.8 points, p<0.001) than were contact persons. Among other factors, both status as an IP and being informed about the measures positively influenced participants’ adherence. The linear regression analysis explained 6.6% and 14.4% (corr. R²) of the adherence to CBRs and HBRs.

Conclusions

Not all persons under official quarantine were aware of the relevant behavioural recommendations. This was especially true in cases where instructions were given for measures to be taken in one’s own household. Due to the high transmission rates within households, HBRs should be communicated with particular emphasis.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, infection control, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large, homogenous cohort of participants in officially ordered isolation and quarantine, a subgroup for which studies on adherence are lacking.

Detailed consideration of the various recommendations for domestic isolation and quarantine, taking motivation into account.

Limitation to the catchment area of the Cologne Health Department, Germany.

Selection bias due to the online format of the survey.

Non-compliance with officially ordered isolation and quarantine measures is a punishable offence in Germany. Even though the anonymity of participants was explicitly mentioned in our survey, it cannot be ruled out that this led to desired, less honest answers.

Introduction

Alongside vaccination, public health interventions such as restrictions on public life, social distancing and, in particular, isolation of people infected with COVID-19 (infected persons (IPs)) and the quarantine of their close contacts (contact persons (CPs)) continue to constitute a central pillar of COVID-19 control in many countries.1 Therefore, there have been severe penalties if officially ordered quarantine and isolation measures are not followed. In Germany, at the time of the survey, punishment betrayed an income-related fine of over €20 000 or a prison sentence of up to 5 years, which was relatively high by international comparison. In other countries such as Japan or Sweden, no penalties were threatened in cases of disregarding isolation and quarantine recommendations.2

Analyses of adherence to social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, have yielded findings ranging from 87% adherence3 to 92.8% non-adherence4 due to different questionnaire items and assessment criteria. Despite this heterogeneity, it has generally been shown that women, older people, those with higher levels of education or socioeconomic status (SES) and people with no dependent children were more likely to implement the interventions than were men, younger people or those with lower levels of education or SES.3–8 In addition to financial–existential problems such as lost income or social obligations to others and cultural–religious issues such as restrictions on religious practice and psychological factors such as depression and anxiety also seem to have had a negative influence on adherence to COVID-19 protection measures.9–11 Conversely, the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated countermeasures have had adverse effects on mental well-being, particularly on rates of depression and anxiety in the population.12 13

The aforementioned studies mainly address general social distancing measures and self-isolation; adherence to officially ordered isolation and quarantine has been hardly investigated before now. A Norwegian cohort study identified almost 1900 people with positive COVID-19 tests from August to October 2020. Among them, only 79% of men and 91% of women adhered to isolation.14 In a UK cohort study that included 1213 people with COVID-19-suspected symptoms, only 42.5% reported not leaving the house in the 10 days after symptom onset. Verberk et al also examined households’ levels of implementing recommendations in a small study of 34 households, each with an index case. While in most households, staying in the same room with the IP was avoided and ventilation was increased; wearing masks in the household was often not considered useful and was rarely implemented.15

Although COVID-19 vaccination significantly reduces infection rates and the infectivity of those affected, isolation and quarantine measures continue to be highly valued responses to the pandemic in the context of emerging variants of concern and reduced vaccine efficacy against these variants.16 17 It is therefore essential to understand the general level of awareness and implementation of various measures and of possible factors influencing awareness and implementation, especially among persons at risk of transmission, such as IPs, or at risk of disease, such as CPs.

Therefore, within the Cologne–Corona Counselling and Support for Index and Contact Persons During the Quarantine Period (CoCo-Fakt) cohort study,18 IPs and CPs in the area of responsibility of the Cologne Health Department, the largest health department in Germany,17 were retrospectively and anonymously surveyed regarding their adherence to quarantine measures following an officially ordered domestic quarantine. Based on Tong et al,19 the study recorded components of the health belief model, in addition to sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, living or relationship situation, and level of education. This model is intended to capture people’s intentions to take or refrain from taking health measures.20 These include the main constructs perceived benefits, perceived barriers, expected results, psychological characteristics/peer group pressure and cues to action/health knowledge.21 The additional analysis of these variables in the context of quarantine adherence should help to develop effective measures.

Methods

Study design

Beginning in February 2020, trained staff from the Cologne Health Authority contacted IPs and CPs by telephone and questioned them in a standardised interview regarding their symptoms, possible routes of infection, chronic diseases, risk factors and residential and family situations.17 These individuals had been quarantined based on the legal regulations for combating infectious diseases according to the Infectious Diseases Protection Act (in German, Infektionsschutzgesetz), with the usual length of quarantine for IPs being 14 days after symptom onset or a positive test result. The quarantine period for CPs was 10–14 days at the time of this survey, depending on the time of last contact. Until October 2020, this period could be extended, lasting several weeks for families that could not be physically separated. All data were recorded using the Cologne Health Authority’s specially programmed software, the digital contact management system DiKoMa.22

The CoCo-Fakt study integrated all IPs and their relevant CPs, who had been quarantined by Cologne’s local health authorities since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020. Therefore, from 28 February 2020 (the date of the first COVID-19 case in Cologne) to 9 December 2020, all persons who were at least 16 years old, registered in DiKoMa with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test (by quantitative real-time PCR) and whose written informed consent was obtained were integrated into this analysis, along with their relevant CPs.

The demographic factors of this survey were based on a modified version of the COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO) questionnaire from the University of Erfurt.23 In addition, items on awareness and implementation of the behavioural recommendations were derived from the official recommendations provided by the WHO, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) and the German Society for General and Family Medicine.24–27

To prevent participants from providing untruthful information in the questionnaire, for fear of prosecution on admitting incompliant behaviour, participants were explicitly informed in the written clarification that the answers would be evaluated anonymously and could not be assigned to specific persons.

The questionnaire was carried out by the online survey software Unipark. Responding to the questionnaire took participants approximately 30 min, and qualitative data were evaluated using MAXQDA software. The survey was conducted from 12 December 2020 to 6 January 2021.

The detailed study design, including the complete questionnaire, was published in advance as a study protocol.18

Patient and public involvement

The research questions and methods were developed based on the literature available at the time of the study’s development in summer 2020. Affected persons from the researchers’ personal environment were first approached and asked to respond to and assess the draft in order to optimise the survey and align it with the research questions. From this collective, 20 additional affected persons were recruited by snowball sampling, and the survey’s feasibility and duration were tested during June and July 2020. The draft questionnaire was adapted and finalised based on feedback from these respondents. Since the online survey was anonymised, no individual results were given to the patients (see Joisten et al18).

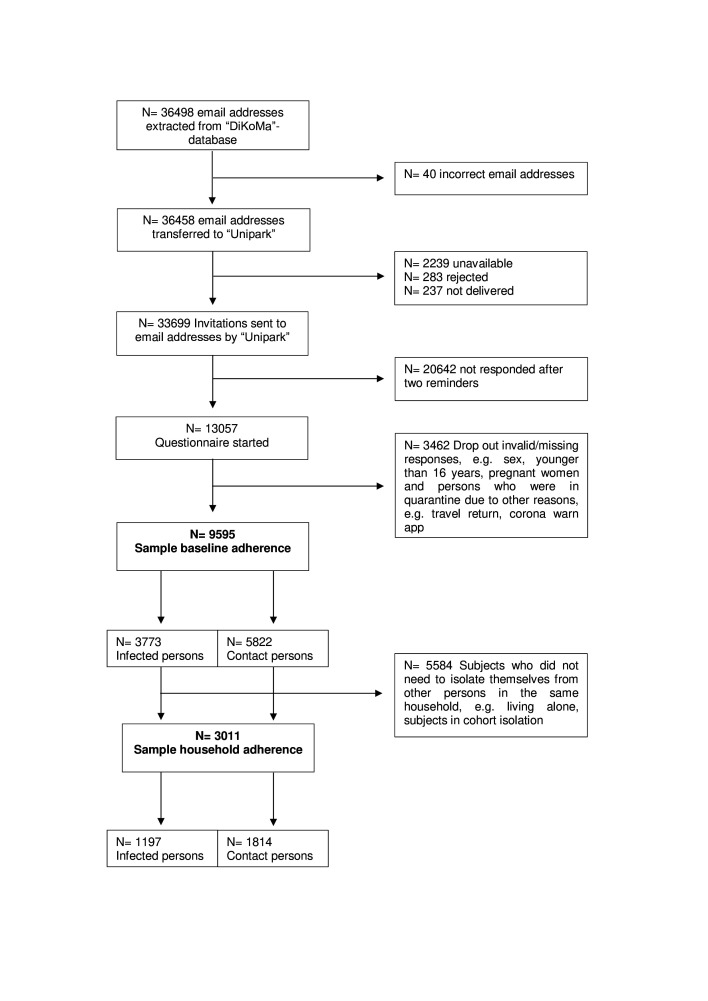

Sampling and study population

A total of 36 498 persons whose email addresses were known were identified in DiKoMa during the period under consideration. Of these, 33 699 persons were sent the questionnaire, and 13 057 clicked on the questionnaire. The study excluded pregnant women who were monitored and advised particularly intensively by the Cologne Health Department during the study period, persons under 16 years of age, subjects with missing or invalid essential information (sex, age, and awareness of quarantine recommendations 1–3) and subjects who could not be assigned to the IP or CP groups (eg, travel returnees) (n=3462). Contacts who tested positive for SARS-CoV-19 during quarantine were included in the infected group. Thus, 9595 subjects (3773 IPs and 5822 CPs) were included in the analysis of adherence to community-based recommendations (CBRs). Household-based recommendations (HBRs) were relevant only for those individuals who needed to isolate themselves from others within a household. Therefore, individuals for whom this did not apply, such as those living alone or in cohort isolation, were not included in the analysis of household-based adherence (n=5584). A total of 3011 subjects (1197 IPs and 1814 CPs) were included in the analysis of household-based adherence (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the participants.

Demographic parameters and personal living situations

Based on the COSMO survey, age, gender, migration background (yes/no), relationship status (single/partnered), chronic illnesses (yes/no), children (yes/no) and their number, living alone (yes/no) and access to a garden or balcony (yes/no) were assessed. SES was determined based on the classifications of the German Health Update 2009.28

Quarantine recommendations: awareness, implementation and difficulties

Recommendations on behaviour in isolation and quarantine from the WHO, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the RKI and the German Society for General and Family Medicine were reviewed.24–27 As a synopsis of all these recommendations, a list with a total of 19 relevant isolation and quarantine recommendations was compiled by the authors (table 1).

Table 1.

Behavioural recommendations in domestic quarantine and isolation

| No | Recommendation | |

| 1 | Do not leave your home. | CBR |

| 2 | Do not receive visitors. | |

| 3 | Avoid personal contact with postal and delivery workers and instruct them to leave deliveries outside the house or flat entrance. | |

| 4 | Stay apart from other household members in a single room. | HBR |

| 5 | Sleep separately from other household members in a single room. | |

| 6 | Have contact with other household members only when you need their help. | |

| 7 | Keep at least a 1.5 m distance when in contact with other household members. | |

| 8 | Wear a mouth–nose mask when in contact with other household members. | |

| 9 | Take your meals in a different room from other household members. | |

| 10 | Use the bathroom, hallway, kitchen and other common areas only when absolutely necessary. | |

| 11 | Use only one toilet. The rest of the household members should not use this toilet. | |

| 12 | The bathroom you use should be cleaned at least once a day. | |

| 13 | Surfaces you frequently touch (bedside table, door handles, smartphone, work surfaces, etc) should be cleaned once a day. | |

| 14 | Air all rooms regularly. | |

| 15 | Sneeze into the crook of your elbow or a disposable handkerchief. | |

| 16 | Wash your hands regularly for at least 20 s, especially after blowing your nose or sneezing. | |

| 17 | Collect tissues, gloves and other rubbish in a lidded bin in your room. | |

| 18 | After washing your hands, use paper towels or a towel that only you use, and change it daily. | |

| 19 | Wash your clothes at a minimum of 60° and separately from the laundry of other household members. |

The evaluations of recommendations 1–4, 7, 8, 14 and 16 (bold), which the authors consider particularly relevant, are addressed in the paper and included in the calculation.

CBR, community-based recommendation; HBR, household-based recommendation.

Of these, three recommendations (do not receive visitors, stay at home, and have no contact with delivery or postal workers) relate to seclusion from the public, are relevant for all persons in quarantine and were classified as CBRs. The other 16 recommendations relate to seclusion within a household and are relevant only to people who needed to isolate themselves from other household members but not to people living alone or to index people in cohort isolation; these were classified as HBRs. To identify subjects for whom HBRs were relevant, the item ‘Did you have to isolate yourself from other household members during your quarantine? (yes/no)’ was included in the questionnaire.

CBRs 1–3 were presented to all participants. The HBRs were presented only to subjects who indicated that they had had to isolate themselves from other household members. Recommendation 11 (use of a separate toilet) was also presented only to subjects who had previously reported living in a household with more than one toilet. For each recommendation presented, the respondents were first asked whether the respective recommendation was known (yes=1, no=2). If the recommendation was known, they were also asked to what extent it had been implemented and how difficult it was to implement. The survey was carried out using a six-part interval scale with endpoints: 1, I have not implemented at all; 6, I have fully implemented; 1, I have found this very difficult; and 6, I have not found this difficult at all.

Whereas at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, droplet and smear infection were considered the main transmission routes, inhalation of virus-containing particles in the form of aerosols has since been identified as the most important transmission route in the further course of the pandemic.29 The present paper considers in more detail the CBRs on staying in a single room, having regular ventilation, wearing a mouth–nose covering, keeping a distance of 1.5 m from other persons and practising hand hygiene, which are considered particularly relevant for the prevention of aerosol transmission and have been promoted in an extensive public campaign by the German Federal Ministry of Health.30 To enable comparability of adherence in our study population with other cohorts, we recorded behaviour in isolation and quarantine for these 19 recommendations in the finest detail possible. Definitions of adherence that, for example, only consider not leaving home31 32 or only selected WHO recommendations31 could thus also be recreated from our dataset. Evaluations of other recommendations can be found in online supplemental tables S1–S3.

bmjopen-2022-063358supp001.pdf (154.3KB, pdf)

Adherence scores

Baseline adherence score

A self-developed baseline adherence score was calculated to map individual adherence and examine influencing factors. The basis for this baseline adherence score was the awareness and implementation of the particularly important CBRs 1–3.

According to the answers on the six-part scale for the implementation of the recommendations, each respondent received points from 0 (not implemented at all) to 5 (fully implemented) for each of the three recommendations. If the respondent was unaware of the recommendation or did not provide information on implementation, 0 point was awarded. With three recommendations scored, the maximum possible score was 15, corresponding to a baseline adherence score of 100%.

Household adherence score

Following the same procedure, a self-developed household adherence score was calculated, including HBRs 4, 7, 8, 14 and 16 for all subjects who had to isolate themselves from other household members. Missing answers, as well as the answer ‘I did not implement at all’, were weighted with 0 points. With five recommendations scored, the maximum possible score was 25, corresponding to a household adherence score of 100%.

Items of the health belief model

To capture in detail the factors influencing health-related behaviour under the health belief model (perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, expected result, psychological characteristics/peer group pressure and cues to action/health knowledge), we developed 11 statements or questions with hypothetical influence on adherence, with isolation and quarantine measures based on Tong et al and Al-Sabbagh et al rose11 19 20

-

Perceived severity/perceived susceptibility.

‘I think COVID-19 is dangerous’.

-

Perceived benefits.

‘When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting myself’.

‘When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting other members of my household’.

‘When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting our society from the further spread of the COVID-19’.

-

Perceived barriers.

‘I experienced difficulties in obtaining everyday necessities during isolation/quarantine’.

‘I suffered financial losses due to the isolation/quarantine’.

-

Expected result.

‘I think the isolation/quarantine measures are too strict’.

‘I think the quarantine measures are too lax’.

-

Psychological characteristics/peer group pressure.

‘People in my professional and social environment have expected me to implement the quarantine measures’.

-

Cues to action/health knowledge.

‘I have been given clear information about the reason for the isolation/quarantine’.

‘It was explained to me in an understandable way how to behave in isolation/quarantine’.

Respondents’ agreement with each statement was determined using a six-item endpoint-named interval scale (strongly disagree–strongly agree). For the question regarding financial losses due to quarantine, the answer was binary (yes/no) (online supplemental table S4).

Data analysis

Descriptive and inductive data analyses were conducted using the programme SPSS V.28.0. χ2 tests and t-tests were conducted to assess the differences between IPs and CPs.

Linear backward regression analyses were conducted to determine the influence of age (in years), quarantine as an IP (1) or CP (2), gender (female=1, male=2), being in a partnership (no=1, yes=2), living situation with balcony or garden (yes=0, no=1), migration background (no=1, yes=2), SES (high=1, middle and low=2), comorbidity (yes=1, no=2), presence of children in the household (yes=1, no=2), as well as the hypothetical factors influencing the baseline and household adherence scores listed previously (online supplemental table S4) (agree=1, disagree=2). Non-significant factors were excluded during stepwise regression. A p value below 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic parameters and personal life situation

Among the study participants, 60.4% were women (see table 2). The proportion of women among the CPs was 63.0%, which was significantly higher than the proportion of women among the index persons at 56.5% (p<0.001). The participants in the study were, on average, 40.9±14.2 years old. Index participants were, on average, 41.9±14.3 years old, slightly older than contacts with an average age of 40.3±14.1 years (p<0.001). Of the study participants, 5.4% had a migration background; here, too, there was a significant difference between 7.2% of the index persons and 4.2% of the CPs (p<0.001).

Table 2.

General characteristics of participants, total and by status as IP or CP

| Variable | Total N (%) |

IPs n (%) |

CPs n (%) |

P value |

| Sample | 9595 (100) | 3773 (39.3) | 5822 (60.7) | |

| Sex | 9595 (100) | |||

| Male | 3797 (39.6) | 1643 (43.5) | 2154 (37.0) | <0.001* |

| Female | 5798 (60.4) | 2130 (56.5) | 3668 (63.0) | |

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 40.9 (14.2) | 41.9 (14.3) | 40.3 (14.1) | <0.001† |

| Age groups (years) | 9595 (100) | |||

| 16–29 | 2580 (26.9) | 925 (24.5) | 1655 (28.4) | <0.001* |

| 30–39 | 2260 (23.6) | 853 (22.6) | 1407 (24.2) | |

| 40–49 | 1771 (18.5) | 731 (19.4) | 1040 (17.9) | |

| 50–59 | 1953 (20.4) | 812 (21.5) | 1141 (19.6) | |

| 60–69 | 789 (8.2) | 339 (9.0) | 450 (7.7) | |

| 70+ | 242 (2.5) | 113 (3.0) | 129 (2.2) | |

| Migration background | 9427 (100) | |||

| No | 8919 (94.6) | 3421 (92.8) | 5498 (95.8) | <0.001* |

| Yes | 508 (5.4) | 265 (7.2) | 243 (4.2) | |

| Socioeconomic status | 9522 (100) | |||

| High | 7644 (80.3) | 2964 (79.2) | 4680 (80.9) | 0.007* |

| Middle | 1790 (18.8) | 731 (19.5) | 1059 (18.3) | |

| Low | 88 (0.9) | 47 (1.3) | 41 (0.7) | |

| Married/living in a relationship | 9383 (100) | |||

| No | 2650 (28.2) | 1012 (27.5) | 1638 (28.7) | 0.186* |

| Yes | 6733 (71.8) | 2671 (72.5) | 4062 (71.3) | |

| Having children | 9553 (100) | |||

| No | 5419 (56.7) | 2070 (55.2) | 3349 (57.7) | 0.013* |

| Yes | 4134 (43.3) | 1683 (44.8) | 2451 (42.3) | |

| Living alone | 9545 (100) | |||

| No | 6767 (70.9) | 2656 (70.8) | 4111 (70.9) | 0.905* |

| Yes | 2778 (29.1) | 1094 (29.2) | 1684 (29.1) | |

| Access to balcony or garden | 9557 (100) | |||

| No | 1443 (15.1) | 530 (14.1) | 913 (15.7) | 0.030* |

| Yes | 8114 (84.9) | 3226 (85.9) | 4888 (84.3) | |

| Comorbidity | 9264 (100) | |||

| No | 7212 (77.8) | 2768 (76.2) | 4444 (78.9) | 0.003* |

| Yes | 2052 (22.2) | 863 (23.8) | 1189 (21.1) |

*χ2 test.

†Unpaired t-test.

CP, contact person; IP, infected person.

Awareness of the recommendations

Results showed that 88.8% of all respondents, 92.2% of IPs and 86.6% of CPs were aware of all three CBRs (stay at home, do not receive visitors and have no contact with delivery or postal workers). On average, 2.9±0.3 of the CBRs were known to the IPs, and 2.8±0.4 were known to the CPs (p<0.001). While 98.7% of respondents were aware of the recommendation not to receive visitors and 98.3% were aware of the recommendation not to leave home, only 90.1% were aware of the recommendation not to have contact with delivery or postal workers.

The awareness of the 16 HBRs varied more markedly. On average, 10.7±4.0 of the 16 HBRs were known to all subjects, 11.2±3.8 to the IPs and 10.3±4.0 to the CPs (p<0.001). For example, only 33.2% of respondents were aware of the recommendation to wash laundry separately and at 60°C, and only 41.1% knew about the recommendation to dispose of waste in a separate waste bin. On the other hand, 97.7% and 95.1% of the respondents stated that they were aware of the recommendations on coughing and sneezing etiquette and regular hand hygiene, respectively. While the recommendations of staying in a single room, having regular ventilation and keeping a distance of 1.5 m were also widely known, the recommendation to wear a mouth–nose covering inside their house or flat was less well known, especially among CPs (p<0.001) (online supplemental table S1).

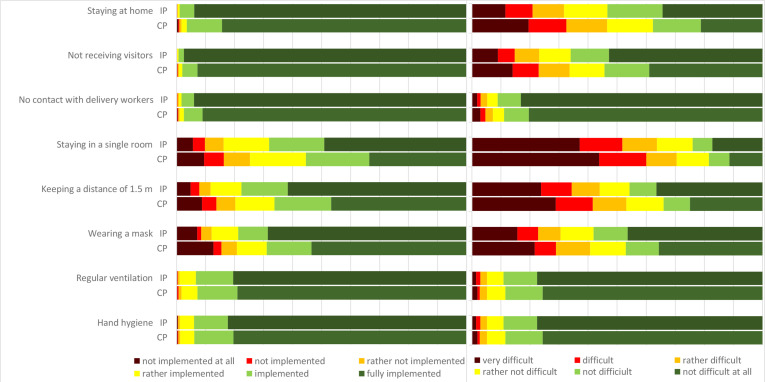

Implementation of the recommendations

On the six-item endpoint-named interval scale for implementation of interventions, the three CBRs ‘Do not leave your home’ (IP: mean=5.9±0.4, CP: mean=5.8±0.7), ‘Do not receive visitors’ (IP: mean=6.0±0.3, CP: mean=5.9±0.5) and ‘Avoid personal contact with postal and delivery workers’ (IP: mean=5.9±0.4, CP: mean=5.9±0.5) achieved very high rates of implementation. CPs implemented the HBRs to a somewhat lesser degree (p<0.001). The HBRs on regular ventilation (IP: mean=5.7±0.7, CP: mean=5.7±0.7) and hand washing (IP: mean=5.7±0.7, CP: mean=5.7±0.7) were quite well implemented, with no appreciable differences between IPs and CPs here (p=0.275 and p=0.363). Comparatively worse was the implementation of the HBRs on staying in a single room (IP: mean=4.9±1.5 and CP: mean=4.4±1.6), keeping a distance of 1.5 m (IP: mean=5.2±1.4, CP: mean=4.7±1.6) and wearing a mouth–nose mask (IP: mean=5.2±1.5, CP: mean=4.7±1.8). These recommendations, which involve distancing oneself from other household members, were implemented significantly better by the IPs than by the CPs (p<0.001) (see figure 2 and online supplemental table S2).

Figure 2.

Relative distribution of implementation (left) and difficulty (right) of selected recommendations in domestic isolation and quarantine, separated for IPs and their CPs. CP, contact person; IP, infected person.

Baseline adherence score

The mean baseline adherence score was 13.8±2.4 out of 15 points (=100%), equivalent to an adherence rate of 92.8%. Only 0.7% (n=68) of respondents did not observe any of the CBRs, obtaining a score of 0 points. Of the respondents, 70.8% fully implemented the included recommendations, corresponding to a baseline adherence score of 15 points. IPs achieved significantly higher adherence scores than did CPs (14.3±2.0 points vs 13.7±2.6 points, p<0.001), representing a baseline adherence of 95.3% (IPs) vs 91.2% (CPs). In total, 64.9% of contacts and 80.0% of index persons achieved a baseline adherence score of 15 points or 100%. The detailed distribution of the baseline adherence score is shown in online supplemental table S5.

Household adherence score

The mean household adherence score was 17.2±6.8 out of 25 points (=100%), equivalent to an adherence rate of 68.8%. Of the respondents, 2.2% (n=67) did not observe any of the HBRs, obtaining a score of 0 points, whereas 18.2% fully implemented all included recommendations, corresponding to a household adherence score of 25 points. IPs achieved a significantly higher adherence score than did CPs (18.2±6.7 points vs 16.5±6.8 points, p<0.001), representing a household adherence of 72.9% (IPs) vs 66.0% (CPs). In total, 22.8% of IPs and 15.1% of CPs achieved a household adherence score of 25 points. The detailed distribution of the household adherence score is shown in online supplemental table S6.

Difficulties of implementation

The greatest implementation difficulties were found for the recommendations requiring distancing from familiar people. The most problematic was the implementation of seclusion in a single room (IP: mean=2.9±1.9, CP: mean=2.6±1.8; 1=very difficult, 6=not difficult at all). The recommendation to wear a mouth–nose covering when in contact with other household members (IP: mean=4.4±1.9, CP: mean=3.9±2.0), to keep a distance of 1.5 m (IP: mean=3.8±2.0, CP: mean=3.4±2.0), to avoid visitors (IP: mean=4.7±1.7, CP: mean=4.2±1.8) and to stay at home (IP: 4.2, CP: 3.6) were also comparatively difficult to implement. In contrast, the recommendations on regular hand washing (IP: mean=5.6±0.9, CP: mean=5.6±0.9), airing (IP: mean=5.6±1.0, CP: mean=5.5±1.0) and avoiding contact with delivery and postal workers (IP: mean=5.6±1.0, CP: mean=5.5±1.1) were easy to implement. While there were no significant differences in the perceived difficulty of implementing the recommendations on airing and hand washing between IPs and CPs (p=0.483 and p=0.219), the implementation of the other recommendations mentioned previously was perceived as more difficult by CPs than by IPs (p<0.001) (see figure 2 and online supplemental table S3).

Views on isolation and quarantine for COVID-19

Perceived severity and perceived susceptibility

On the six-point Likert scale, both IPs and CPs considered COVID-19 relatively dangerous (IP: mean=5.4±1.1, CP: mean=5.5±0.9). CPs perceived COVID-19 as significantly more dangerous than IPs (p<0.001).

Perceived benefits

While the statement that isolation/quarantine protects oneself received comparatively low agreement among both IPs and CPs (IP: mean=3.7±2.1, CP: mean=3.9±2.0), the statement that isolation/quarantine protects other household members (IP: mean=4.6±1.8, CP: mean=4.4±1.9), as well as society, from the further spread of COVID-19 (IP: mean=5.8±0.7, CP: mean=5.8±0.7) received high or very high agreement.

Perceived barriers

Supply shortages for everyday necessities (IP: mean=2.4±1.7, CP: mean=2.3±1.7), as well as financial losses (IP: mean=1.8±0.4, CP: mean=1.8±0.4; 1=yes, 2=no), did not seem to have existed to any great extent for participants during isolation/quarantine. There was no significant difference between IPs and CPs in this regard (p=0.061 and p=0.271).

Expected results

There was also low agreement with the statements that the isolation/quarantine measures were too strict (IP: mean=2.2±1.7, CP: mean=2.5±1.7) or too lax (IP: mean=2.4±1.7, CP: mean=2.4±1.6).

Psychological characteristics/peer group pressure

Many respondents seemed to feel social pressure to implement the recommendations (IP: mean=5.5±1.2, CP: mean=5.3±1.3). IPs were significantly more likely to report having felt social pressure (p<0.001).

Health knowledge/cue to action

IPs, in particular, showed a high level of agreement with the statements that they had been informed about the recommended behavioural measures of isolation/quarantine and the reason for these measures (IP: mean=5.3±1.3; CP: mean=4.8±1.7) (see online supplemental table S4).

Factors influencing adherence during isolation and quarantine

Regression analysis was used to determine factors influencing baseline adherence scores. The baseline models are shown in the supplement (online supplemental table S7). The final models are shown in table 3. A total of 7173 subjects were included in the regression analysis of the baseline adherence score. Factors correlating with higher baseline scores included status as an IP (β=−0.102, p<0.001), older age (β=0.055, p<0.001), presence of children in the household (β=−0.037, p=0.008) and agreement with the following statements: ‘It was explained to me in an understandable way how to behave in quarantine’ (β=0.136, p<0.001); ‘When I isolate quarantine myself, I am protecting other members of my household’ (β=0. 046, p<0.001); ‘When I isolate quarantine myself, I am protecting our society from the further spread of COVID-19’ (β=0.049, p<0.001); and ‘People in my professional and social environment have expected me to implement the quarantine measures’ (β=0.069, p<0.001). Agreement with the statements that the isolation/quarantine measures were too strict (β=−0.049, p<0.001) or too lax (β=−0.033, p=0.004) or that there were supply difficulties during isolation/quarantine (β=−0.042, p<0.001) was associated with a lower baseline adherence score. The model explained 6.6% (corr. R²) of the variance.

Table 3.

Factors influencing the baseline and household adherence scores

| Final models | Non-standardised coefficients | Standardised coefficients | Sig. | 95% CI | ||

| Regression coefficient (B) | SE | Beta | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||

| Baseline adherence score | ||||||

| IPs (1) versus CPs (2) | −0.030 | 0.003 | −0.102 | <0.001 | −0.037 | −0.024 |

| Age (years) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.055 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Having children (yes=1, no=2) | −0.011 | 0.004 | −0.037 | 0.008 | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting other members of my household.* | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.046 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.022 |

| When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting our society from the further spread of COVID-19.* | 0.049 | 0.013 | 0.045 | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.073 |

| I experienced difficulties in obtaining everyday necessities during isolation/quarantine.* | −0.014 | 0.004 | −0.042 | <0.001 | −0.022 | −0.006 |

| I think the isolation/quarantine measures are too strict.* | −0.016 | 0.004 | −0.049 | <0.001 | −0.024 | −0.009 |

| I think the isolation/quarantine measures are too lax.* | −0.011 | 0.004 | −0.033 | 0.004 | −0.019 | −0.004 |

| People in my professional and social environment have expected me to implement the quarantine measures.* | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.069 | <0.001 | 0.025 | 0.049 |

| It was explained to me in an understandable way how to behave in quarantine.* | 0.051 | 0.004 | 0.136 | <0.001 | 0.043 | 0.060 |

| Household adherence score | ||||||

| IPs (1) versus CPs (2) | −0.052 | 0.010 | −0.103 | <0.001 | −0.072 | −0.032 |

| Age (years) | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.108 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Sex (female=1, male=2) | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.043 | 0.030 | 0.002 | 0.042 |

| Migration background (no=1, yes=2) | 0.064 | 0.022 | 0.058 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.107 |

| Socioeconomic status (high=1, middle and low=2) | −0.028 | 0.012 | −0.045 | 0.025 | −0.052 | −0.004 |

| Married/living in a relationship (no=1, yes=2) | 0.062 | 0.014 | 0.099 | <0.001 | 0.035 | 0.090 |

| Having children (yes=1, no=2) | −0.029 | 0.013 | −0.058 | 0.028 | −0.054 | −0.003 |

| I think COVID-19 is dangerous.* | 0.059 | 0.023 | 0.052 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.104 |

| I have been given clear information about the reason for the isolation/quarantine.* | 0.042 | 0.017 | 0.060 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.076 |

| It was explained to me in an understandable way how to behave in quarantine.* | 0.031 | 0.016 | 0.047 | 0.051 | <0.001 | 0.063 |

| When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting other members of my household.* | 0.145 | 0.012 | 0.240 | <0.001 | 0.121 | 0.169 |

| When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting our society from the further spread of COVID-19.* | 0.074 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.072 | −0.007 | 0.154 |

| I suffered financial losses due to the isolation/quarantine (yes=1, no=2). | −0.021 | 0.012 | −0.034 | 0.090 | −0.045 | 0.003 |

*Final models of linear backward regression analyses (disagree=1, agree=2).

CP, contact person; IP, infected person.

Factors influencing household adherence scores were analysed analogously (see online supplemental table S7 and table 3). A total of 2227 subjects were included in the regression analysis of the household adherence score. Here, factors correlating with higher household adherence scores included IP status (β=−0.103, p<0.001), older age (β=0.108, p<0.001), male gender (β=0.043, p=0.030), migration background (β=0.058, p=0.004), lower SES (β=−0.045, p=0.025), living in a relationship (β=0.099, p<0.001), having children in the household (β=−0.058, p=0.028), considering COVID-19 dangerous (β=0.052, p=0.011), and agreement with the following statements: ‘I have been given clear information about the reason for the isolation/quarantine’ (β=0. 060, p=0.014), ‘It was explained in an understandable way how to behave in isolation/quarantine’ (β=0.047, p=0.051), ‘When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting other members of my household’ (β=0.240, p<0.001) and ‘When I isolate/quarantine myself, I am protecting our society from the further spread of COVID-19’ (β=0.037, p=0.072). In addition, there was a positive association between financial losses due to quarantine and household adherence (β=−0.034, p=0.090). The model explained 14.4% (corr. R²) of the variance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first studies in Germany of adherence to recommendations while in official domestic isolation or quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study showed that the measures for seclusion from the public were especially well implemented (92.8% adherence). Adherence to measures requiring distancing from other household members reached only 68.8%. The measures calling for seclusion in a single room and keeping a distance of 1.5 m from other household members were both particularly difficult to implement. By contrast, regular airing and washing of hands, as well as avoiding contact with delivery and postal workers, were easier. The lower adherence to measures of separating from other household members aligns with the results of a study by Broichhaus et al on COVID-19 transmission routes conducted at about the same time in Cologne, according to which a large proportion of infections occurred within the same household.32

In the present study, men were more adherent than women; older people were more adherent than younger people; and IPs were more adherent than CPs. The higher adherence of IPs could be due to their knowledge of acute contagiousness and a more direct benefit from the behavioural measures. However, the extent to which the higher adherence of IPs can also be attributed to symptom-related immobility remains speculative. It is evident that CPs, in particular, must be informed about the meaning and benefits of quarantine, especially if they are unvaccinated.

Al-Hanawi et al, Al Zabadi et al and Park et al also found higher adherence among older people in survey studies on the implementation of social distancing measures in the general population, as did Smith et al in a study on self-isolation at the onset of COVID-19 symptoms in a British cohort.3 33–35 However, in all four studies, women were more likely to implement the relevant measures. Why men performed better on HBRs in our study can only be speculated here. As the Mannheim–Corona study by Cornesse et al suggests, women (still) feel more obliged to take on household tasks, even during quarantine.36 Smith et al showed lower adherence in their study among subjects with younger children in the household. However, the only criterion for adherent behaviour in their study was whether the subjects left their home.35 Our study found a positive correlation between the presence of children in the household and greater adherence, accounting for all relevant isolation/quarantine recommendations. Subjects with children in the household implemented the HBRs significantly better than did subjects without children at home. The reason for this could be the high motivation of many parents to protect their children from infection. However, the extent to which psychosocial reasons played a role here, such as the feeling of loneliness or existential hardship, can only be speculated at this point.

These speculations are supported by the results from the health belief model. Thus, the measures were predominately perceived as appropriate and not too strict. In addition to the perceived risks associated with a given disease, the assumed costs and benefits of different behaviours also influence the extent of behavioural change.20

Subjects who stated that they had been clearly informed about both the reason for their isolation or quarantine and the scope of the measures mandated showed greater adherence to the measures, in accordance to the construct ‘health knowledge/ cues to action’, in the health belief model. Adherence was also positively influenced by the assessment of the measures as appropriate, as well as by the perception of social pressure in relation to their implementation, which can be attributed to the constructs expected results and psychological characteristics/peer group pressure. The construct perceived severity and susceptibility reflected the perception that COVID-19 is dangerous and had a further positive influence on household adherence. In cross-sectional studies of perceptions of COVID-19 and social distancing measures, Hills and Eraso and Al-Sabbagh et al found that the perceived dangerousness of infection and identifying oneself as belonging to a risk group were both associated with higher adherence.4 11 Results are contradictory with regard to the construct of perceived barriers. While Al-Sabbagh et al also found that a perceived financial disadvantage related to social distancing measures correlated with lower adherence, the present study associated higher expenditures or financial losses due to isolation or quarantine with higher household adherence.11 This fact could be explained by a certain retrospective aspect of our study: those who adhered more strictly to the measures may, as a result, have had higher costs (eg, for hygiene items or delivery services).

Strengths and limitations

A particular strength of this survey was its large, homogeneous cohort and its detailed consideration of the various recommendations, taking quarantine reason (IP or CP) and motivation into account. Even though this survey was limited to the catchment area of the largest health department in Germany, the measures were largely uniform across Germany, and the approaches taken by the various health departments were comparable. This makes it quite likely that the findings can be transferred reliably to other urban regions. It must be particularly emphasised that this was a full census, taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, mainly people with higher SES and without a migration background participated, making it difficult to transfer the findings to other target groups. Psychological, cultural–religious factors and coping strategies, which possibly also influenced adherence, were not taken into account. One further limitation, however, was the online format, which could have prevented older participants, particularly those who are less computer-literate, from participating. However, the average age of the study participants, at 40.9 years, is 13 months below the average age of the Cologne population.37 Furthermore, when interpreting the results, it must be taken into account that citizens placed under isolation/quarantine orders were informed that non-compliance with certain measures, especially leaving one’s own home, could be punished. Even though the anonymity of participation was explicitly mentioned in our survey, it cannot be ruled out that the threat of subsequent punishment led to desired and less honest answers.

Moreover, it is plausible that more of those who complied with the prescribed measures took part in the survey.

Conclusions

In summary, adherence was quite high overall, especially with regard to the general isolation/quarantine rules. However, with high infection rates in households with an index case in the past and the comparatively lower adherence to isolation and quarantine within one household found in this study, it still seems sensible to develop more strategies for increasing adherence, particularly within households.38 The pandemic has been ongoing for more than 2 years, and with the emergence of new viral variants such as Omicron and its subtypes, associated weakened vaccine effectiveness and a still-significant number of unvaccinated people, the importance of non-drug measures is clear. As Telenti et al have indicated, responsible management of COVID-19 will continue to be relevant in the future.39 Thus, to support staff in health offices in their care of citizens, adequate education on the benefits of quarantine measures should be implemented in the public sphere. This might also lead to increased adherence, especially within a household. The approach to successful risk communication outlined by Loss et al, which includes credible messages, acknowledgement of uncertainties and a balance of reassurance and alarm, combined with continuous monitoring and evaluation, could be used as a guide to preventing fatigue in future pandemics and in the ongoing development of COVID-19.40

Key messages and implications

Measures of seclusion from other household members are followed more weakly overall than are measures of seclusion from the public.

Not only uninfluenceable demographic factors such as age, gender, education level or index-person status but also the personal views and beliefs of those affected influence adherence to quarantine and isolation.

Responsible health authorities can increase the adherence of citizens in isolation and quarantine by providing comprehensible information about the reason, benefits and scope of the recommended behavioural measures.

Particular attention should be paid to contact persons and those who must isolate themselves from others within the same household.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nikola Schmidt for her support with the programming of the online survey. Additionally, they also thank everyone who helped with the pretest and participated in the survey.

Footnotes

CJ and AK contributed equally.

Contributors: CJ, AK, JN and GAW conducted the study on behalf of the Cologne–Corona Counselling and Support for Index and Contact Persons During the Quarantine Period study group. JB conducted the questions regarding the quarantine recommendations. CJ and JB conducted the statistical analyses. AK, CJ and JB contributed to interpreting the results. JB wrote the original draft of the manuscript. AK, CJ, GAW, BG, LB and JN provided comments and inputs to revise the manuscript. CJ is acting as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the Rheinisch–Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen Human Ethics Research Committee (351/20). The participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;9:CD013574. 10.1002/14651858.CD013574.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel J, Fernandes G, Sridhar D. How can we improve self-isolation and quarantine for covid-19? BMJ 2021;372:n625. 10.1136/bmj.n625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hanawi MK, Angawi K, Alshareef N, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among the public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2020;8:217. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hills S, Eraso Y. Factors associated with non-adherence to social distancing rules during the COVID-19 pandemic: a logistic regression analysis. BMC Public Health 2021;21:352. 10.1186/s12889-021-10379-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark C, Davila A, Regis M, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: an international investigation. Glob Transit 2020;2:76–82. 10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane MA, Shermock KM, Omer SB, et al. Change in reported adherence to Nonpharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic, April-November 2020. JAMA 2021;325:883–5. 10.1001/jama.2021.0286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lüdecke D, von dem Knesebeck O. Protective behavior in course of the COVID-19 Outbreak-Survey results from Germany. Front Public Health 2020;8:572561. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.572561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szwarcwald CL, Souza Júnior PRBde, Malta DC, et al. Adherence to physical contact restriction measures and the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil. Epidemiol Serv Saude 2020;29:e2020432. 10.1590/S1679-49742020000500018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomou I, Constantinidou F. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:4924. 10.3390/ijerph17144924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Sabbagh MQ, Al-Ani A, Mafrachi B, et al. Predictors of adherence with home quarantine during COVID-19 crisis: the case of health belief model. Psychol Health Med 2022;27:215–27. 10.1080/13548506.2021.1871770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunzler AM, Röthke N, Günthner L, et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analyses. Global Health 2021;17:34. 10.1186/s12992-021-00670-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;52:102066. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trogstad LA, Carlsen E, Caspersen IH, et al. Public adherence to governmental recommendations regarding quarantine and testing for COVID-19 in two Norwegian cohorts. MedRxiv 2020:2020.12.18.20248405. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verberk JDM, Anthierens SA, Tonkin-Crine S, et al. Experiences and needs of persons living with a household member infected with SARS-CoV-2: a mixed method study. PLoS One 2021;16:e0249391. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1532–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa2119451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu L, Grüne B, Buess M, et al. COVID-19 Breakthrough Infections and Transmission Risk: Real-World Data Analyses from Germany’s Largest Public Health Department (Cologne). Vaccines 2021;9:1267. 10.3390/vaccines9111267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joisten C, Kossow A, Book J, et al. How to manage quarantine-adherence, psychosocial consequences, coping strategies and lifestyle of patients with COVID-19 and their confirmed contacts: study protocol of the CoCo-Fakt surveillance study, Cologne, Germany. BMJ Open 2021;11:e048001. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong KK, Chen JH, Yu EW-Y, et al. Adherence to COVID-19 precautionary measures: applying the health belief model and generalised social beliefs to a probability community sample. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2020;12:1205–23. 10.1111/aphw.12230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr 1974;2:354–86. 10.1177/109019817400200405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter CJ. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun 2010;25:661–9. 10.1080/10410236.2010.521906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuhann F, Buess M, Wolff A, et al. Entwicklung einer software Zur Unterstützung Der Prozesse Im Gesundheitsamt Der Stadt köln in Der SARS-CoV-2-Pandemie, Digitales Kontaktmanagement (DiKoMa). Epidemiologisches Bulletin 2020;2020:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betsch C, Wieler L, Bosnjak M, et al. Germany COVID-19 snapshot monitoring (COSMO Germany): monitoring knowledge risk perceptions preventive behaviours and public trust in the current coronavirus outbreak in Germany. PsychArchives 2020. 10.23668/psycharchives.2776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . Home care for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and management of their contacts, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/home-care-for-patients-with-suspected-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-presenting-with-mild-symptoms-and-management-of-contacts [Accessed 17 Sep 2022].

- 25.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Infection prevention and control in the household management of people with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19), 2020. Available: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Home-care-of-COVID-19-patients-2020-03-31.pdf [Accessed 17 Sep 2022].

- 26.Robert Koch-Institut . Häusliche Isolierung bei bestätigter COVID-19-Erkrankung, 2021. Available: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Flyer_Patienten.pdf?__blob=publicationFile [Accessed 17 Sep 2022].

- 27.Kaduszkiewicz H, Kochen M, Pömsl J. Handlungsempfehlung Häusliche Isolierung von CoViD-19-Fällen MIT leichtem Krankheitsbild und Verdachtsfällen, 2020. Available: https://www.degam.de/files/Inhalte/Leitlinien-Inhalte/Dokumente/DEGAM-S1-Handlungsempfehlung/053-054%20SARS-CoV-2%20und%20Covid-19/Publikationsdokumente%20Archiv/053-054_Empfehlungen%20Haeusliche_Isolierung.pdf [Accessed 17 Sep 2022].

- 28.Lange C, Jentsch F, Allen J, et al. Data Resource Profile: German Health Update (GEDA)--the health interview survey for adults in Germany. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:442–50. 10.1093/ije/dyv067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang CC, Prather KA, Sznitman J, et al. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science 2021;373:eabd9149. 10.1126/science.abd9149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.German Federal Ministry of Health, Public Relations Division . Together against corona: how to protect ourselves against the coronavirus, 2021. Available: https://assets.zusammengegencorona.de/eaae45wp4t29/59kagmqA8AWs87Jo2VgpTf/f826234fc4d8d58a891c9d159d2627aa/BMG_Infoflyer_kurz_Corona_English.pdf [Accessed 17 Sep 2022].

- 31.Lin Y, Hu Z, Alias H, et al. Quarantine for the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan City: support, understanding, compliance and psychological impact among lay public. J Psychosom Res 2021;144:110420. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broichhaus L, Book J, Feddern S, et al. Where is the greatest risk of COVID-19 infection? Findings from Germany's largest public health department, Cologne. PLoS One 2022;17:e0273496. 10.1371/journal.pone.0273496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Zabadi H, Yaseen N, Alhroub T, et al. Assessment of quarantine understanding and adherence to Lockdown measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in Palestine: community experience and evidence for action. Front Public Health 2021;9:570242. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.570242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park CL, Russell BS, Fendrich M, et al. Americans' COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:2296–303. 10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith LE, Potts HWW, Amlôt R, et al. Adherence to the test, trace, and isolate system in the UK: results from 37 nationally representative surveys. BMJ 2021;372:n608. 10.1136/bmj.n608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornesse C, Gonzalez Ocanto M, Fikel M, et al. Measurement instruments for fast and frequent data collection during the early phase of COVID-19 in Germany: reflections on the Mannheim corona study. Meas Instrum Soc Sci 2022;4:2. 10.1186/s42409-022-00030-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stadt Köln - Amt für Stadtentwicklung und Statistik . Kölner Zahlenspiegel, 2020. Available: https://www.stadt-koeln.de/mediaasset/content/pdf15/statistik-standardinformationen/k%C3%B6lner_zahlenspiegel_2020_deutsch.pdf [Accessed 17 Sep 2022].

- 38.Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2031756. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Telenti A, Arvin A, Corey L, et al. After the pandemic: perspectives on the future trajectory of COVID-19. Nature 2021;596:495–504. 10.1038/s41586-021-03792-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loss J, Boklage E, Jordan S, et al. Risikokommunikation bei Der Eindämmung Der COVID-19-Pandemie: Herausforderungen und Erfolg versprechende Ansätze. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2021;64:294–303. 10.1007/s00103-021-03283-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-063358supp001.pdf (154.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.