Abstract

This paper describes a synthetic approach to the synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives from cyclopropenes. The Lewis acid-mediated dimerization of cyclopropenes gives tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives. The subsequent thermal ring-opening reaction under solvent-free conditions gives 1,4-cyclohexadienes bearing quaternary carbons. The novel Br2-mediated oxidative rearrangement of 1,4-cyclohexadienes takes place to give 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives in high to excellent yields.

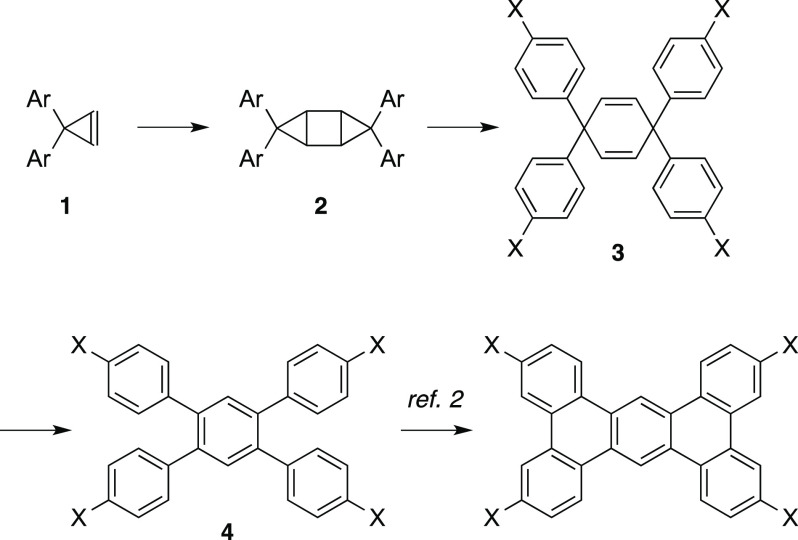

Cyclohexadienes are promising precursors for transition-metal complexes as well as for the synthesis of a benzene core via aromatization.1,2 We attempted to synthesize 1,4-cyclohexadienes bearing quaternary carbons for use in the synthesis of ligands, 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives 4, and the corresponding π-extended molecules via the oxidative rearrangement reaction of 1,4-cyclohexadienes 3, as described in Figure 1.2 A few effective synthetic methods are available for the preparation of 1,4-cyclohexadienes bearing quaternary carbons. The Birch reduction of benzene derivatives or nucleophilic addition to quinone derivatives are typical approaches to the synthesis of 1,4-cyclohexadienes bearing quaternary carbons.3 In this context, we wondered if 1,4-cyclohexadienes 3 would be obtained via the ring-opening reaction of tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives 2, which could be obtained as side products in a several reactions performed with cyclopropenes.4,5 In addition, the photodimerization of cyclopropenes gives tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives in low to moderate yields and selectivities, respectively.6 The present paper describes easy access to 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzenes 4 via the Lewis acid-mediated dimerization of cyclopropenes 1, the thermal ring-opening of tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives 2, and the oxidative rearrangement of 1,4-cyclohexadienes 3.

Figure 1.

Synthetic approach to 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzenes 4.

The screening of Lewis acids for the [2 + 2]-type dimerization of cyclopropenes is shown in Table 1. The reaction of cyclopropene 1a (0.2 mmol) in THF proceeded at room temperature and under reflux conditions in the presence of Me3Al (1 equiv) (entries 1 and 2, respectively). A catalytic amount of Me3Al gave low yields, even with a long reaction time (entries 3 and 4). The decomposition of Me3Al in THF at reflux conditions seems to be inevitable; thus, the present reaction must finish in the shortest time possible. Other Lewis acids or catalysts did not give improved yields (entries 5–16). Therefore, the use of Me3Al (1 equiv) in THF under reflux conditions is suitable for the present [2 + 2]-type dimerization reaction of cyclopropenes. The present reaction might proceed via the activation of a cyclopropene moiety with Me3Al, which would generate a cyclopropylaluminum intermediate (Figure 2).7 Although there is no clear evidence for the mechanism, further reaction with another cyclopropene molecule and the subsequent elimination of Me3Al would generate the desired product. The speculated mechanistic rationale suggests that a catalytic amount of Lewis acid can promote the present reaction, but the experimental results showed that a catalytic amount of Lewis acid was not effective due to the loss of activity during the long reaction time. The dimerization reaction of other alkenes with Me3Al, such as stilbene or acenaphthylene, did not proceed.

Table 1. Screening of Lewis Acids.

| entry | Lewis acid (x) | NMR yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Me3Al (1) | 15 |

| 2 | Me3Al (1) | 92 (87)b |

| 3c | Me3Al (0.5) | 35 |

| 4 | Me3Al (0.05) | 26 |

| 5 | Et3Al (1) | 47 |

| 6 | Me2AlCl (1) | 35 |

| 7 | BF3·OEt2 (1) | messy |

| 8 | Et2Zn (1) | not detected |

| 9 | AlCl3 (0.1) | no reaction |

| 10 | TiCl4 (0.1) | no reaction |

| 11 | Sc(OTf)3 (0.1) | no reaction |

| 12 | Yb(OTf)3 (0.1) | no reaction |

| 13 | NiCl2(dppe) (0.1) | messy |

| 14 | [RhCl(cod)]2 (0.05) | messy |

| 15 | Pd2(dba)3 (0.05) | messy |

| 16 | Al2O3 (0.05) | no reaction |

The reaction was conducted at room temperature for 40 h.

Isolated yield is described in parentheses.

The reaction time was 11 days.

Figure 2.

Speculated mechanism of the [2 + 2]-type reaction.

The optimized reaction conditions for various cyclopropenes gave tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives (Table 2). The reaction of 1a (2 mmol scale) gave the desired product 2a in a 92% yield (entry 1). The reaction of diaryl-substituted cyclopropenes 1b–f gave the desired products 2b–f in moderate to high yields (entries 2–6, respectively). In some cases, the use of an excess amount of Me3Al was effective. Cyclopropenes bearing 2-substituted aryl groups inhibited the Me3Al-mediated reaction. The use of cyclopropenes bearing 3-substituted aryl groups gave the desired products, but a lack of reproducibility was observed. The reaction of dialkyl-substituted cyclopropenes 1g and 1h took place, but the yields were moderate (entries 7 and 8, respectively). The alkyl- and aryl-substituted cyclopropenes 1i–k gave the desired products 2i–k in low yields (entries 9–11, respectively). The stereochemistry of isolated 2i–k would be trans according to the NMR spectra; cis-adducts might be removed during the purification (see the Supporting Information for details). The low yields of 2g–k in the present dimerization reaction might be attributed to the Me3Al-mediated ring opening reaction of cyclopropenes in nonpolar solvents.4,7 We wondered if the ring-opening reaction of the cyclobutane moiety in the tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane architecture would take place via the simple heating of tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives. Typically, the ring-opening reaction of cyclobutane is thermochemically forbidden but photochemically allowed.8 The thermal ring-opening reaction of cyclobutane derivatives takes place via biradical intermediates, where simple cyclobutane requires ca. 1200 K to generate ethylene. In contrast, the ring-opening reaction of vinyl cyclobutanes takes place at ca. 400 K via allylic radical intermediates.9 We found that the thermal reactions of strained molecules 2a–k at their respective temperatures gave the desired 1,4-cyclohexadiene derivatives 3a–k. The thermal ring opening of trans-2i–k would give trans-3i–k, respectively, and the stereocenters at the benzylic positions were untouched during the reaction. The report concerning the Birch reduction of p-terphenyl shows that at room temperature trans-1,4-cyclohexadienes are typically solids and cis-1,4-cyclohexadienes are typically oils.10 The melting points of 3i–k are higher than 140 °C, suggesting the generation of trans-2 and trans-3.

Table 2. Synthesis of 1,4-Cyclohexadienes via Tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexanes.

| entry | R,1 R2 | product 2 (%) | T (°C) | product 3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph (1a) | 2a, 92 | 270 | 3a, 99 |

| 2 | p-MeC6H4– (1b) | 2b, 57 (66)a | 245 | 3b, 98 |

| 3 | p-MeOC6H4– (1c) | 2c, 76 | 245 | 3c, 99 |

| 4 | p-FC6H4– (1d) | 2d, 90 | 258c | 3d, 99 |

| 5 | p-ClC6H4– (1e) | 2e, 80 | 267 | 3e, 99 |

| 6 | p-BrC6H4– (1f) | 2f, 77 | 265 | 3f, 98 |

| 7 | C6H12–, C6H12– (1g) | 2g, 58 | 250c | 3g, 98 |

| 8 | –(CH2)11– (1h) | 2h, 37 | 273 | 3h, 99 |

| 9 | p-MeOC6H4–, Me (1i) | 2i, 6 (14)b | 221 | 3i, 99 |

| 10 | p-ClC6H4–, Me (1j) | 2j, 28 (39)b | 230d | 3j, 98 |

| 11 | 2-naphthyl, Me (1k) | 2k, 40 | 225c | 3k, 99 |

Me3Al (1.1 equiv) was used.

Me3Al (1.4 equiv) was used.

The reaction time was 10 min.

The reaction time was 30 min.

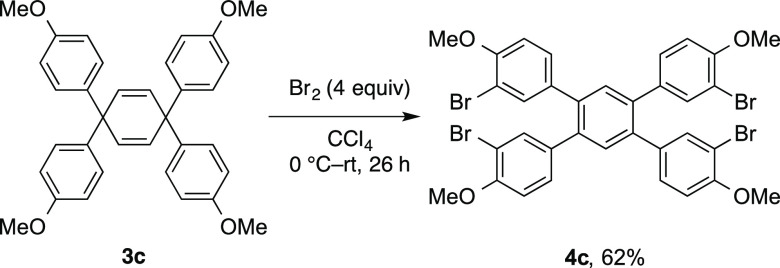

The oxidative rearrangement of cyclohexadienes would be a promising approach to the selective synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives. We considered that the Br2-mediated 1,2-rearrangement of an aryl group in alkenes may be a trigger to achieve the synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives.11,12 In a similar approach, the Br2-mediated oxidation of 1,4-cyclohexadienes was reported by DeBoer.6 We found that treating cyclohexadiene 3a with Br2 (2 equiv) in CCl4 afforded the desired product 4a in a 96% yield. The synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives 4 is shown (Table 3). The reactions of tetraarylcyclohexadienes 4b, 4d, 4e, and 4f using Br2 (2 equiv) in CCl4 from 0 °C to rt gave the desired products in excellent yields (entries 2–5, respectively). However, the reactions of alkyl-substituted cyclohexadienes 3g, 3h, and 3i under similar conditions gave complicated unidentified products (entries 6–8, respectively). In the case of electron-rich cyclohexadiene 3c, oxidative rearrangement and bromination occurred to give tetraarylbenzene 4c in a 62% yield (Scheme 1). Several experiments performed using a stoichiometric amount of Br2 for the present oxidative rearrangement did not exhibit reproducibility. In contrast, the long reaction time for the reaction of 3a in an excess amount of Br2 generated 4f. We wondered if the bromination reaction of tetraarylbenzene derivatives would take place. The reaction of 1,2,4,5-tetra(p-methoxyphenyl)benzene and Br2 in CCl4 did not occur at all, but the simple bromination of tetraphenylbenzene using Br2 (15 equiv) without solvent under dark conditions was described previously.2a The present conditions for oxidative rearrangement require an appropriate amount of Br2 and diluted conditions in CCl4; thus, the subsequent bromination of tetraarylbenzene derivatives under the present reaction conditions would be slow. The reason for the oxidative rearrangement of 3c can give 4c is unclear at the present stage.

Table 3. Oxidative Rearrangement of Cyclohexadienes.

| entry | R1, R2 | product 4 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph (3a) | 4a, 98 |

| 2 | p-MeC6H4– (3b) | 4b, 98 |

| 3 | p-FC6H4– (3d) | 4d, 96 |

| 4 | p-ClC6H4– (3e) | 4e, 99 |

| 5 | p-BrC6H4– (3f) | 4f, 96 |

| 6 | C6H12–, C6H12– (3g) | messy |

| 7 | p-ClC6H4–, Me (3h) | messy |

| 8 | 2-naphthyl, Me (3i) | messy |

Scheme 1. Oxidative Rearrangement of 3c.

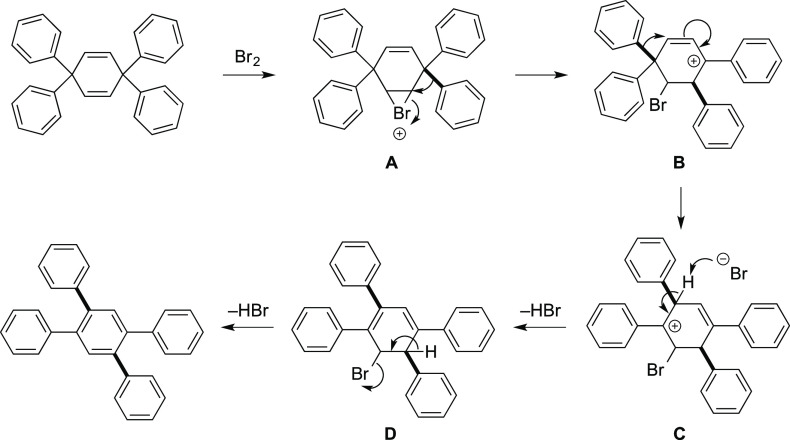

The proposed mechanism for the oxidative rearrangement is shown in Figure 3. The generation of a bromonium intermediate A promotes the rearrangement of an aryl group to give intermediate B, followed by the rearrangement of a second aryl group to give intermediate C. The subsequent dehydrobromination of intermediates C and D resulted in the generation of the desired 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzene derivatives. We performed the reaction of 1,4-cyclohexadiene 3a using TfOH or other Brønsted acids, but a complicated mixture was obtained.13

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism for dehydrogenative rearrangement.

We achieved the sequential transformation of cyclopropenes to 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzenes via a simple operation. The [2 + 2]-type dimerization of cyclopropenes took place in the presence of Me3Al to give tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane derivatives, which were readily converted into 1,4-cyclohexadienes in almost quantitative yields via simple heating. Further novel oxidative rearrangement using Br2 led to the generation of 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzenes. The present approach to the synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetraarylbenzenes contributes to the further synthesis of π-extended molecules.

Experimental Section

General Method

All reactions dealing with air-, moisture-, and light-sensitive compounds were carried out in a dry reaction vessel covered with foil under a positive pressure of argon. All liquids and solutions were transferred via a syringe. The reaction of compounds 1 under heating conditions was carried out using an oil bath. The reaction of compounds 2 was carried out in a crucible using an electric furnace. Analytical thin-layer chromatography was performed on an aluminum plate coated with silica gel containing a fluorescent indicator (Silica Gel 60 F254, Merck). The plates were visualized by exposure to ultraviolet light (254 nm) or by immersion in a basic staining solution of KMnO4, followed by heating with a heat gun. Organic solutions were concentrated using a rotary evaporator. Flash column chromatography was performed using Kanto Silica gel 60N (spherical, neutral). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR, 400 MHz), carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (13C{1H} NMR, 100 MHz), and fluorine nuclear magnetic resonance (19F NMR, 375 MHz) spectra were recorded with JEOL JNM-ECZ400S spectrometers. 1H NMR spectra in CDCl3 were referenced internally to tetramethylsilane (δ 0.00 ppm) as a standard, and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were referenced to the solvent resonance (CDCl3 δ 77.0 ppm). 19F NMR spectra in CDCl3 were referenced externally to trifluoroacetic acid (δ −76.5 ppm) as a standard. Data are presented as follows: chemical shift, spin multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, and m = multiplet), coupling constant in hertz, and signal area integration in natural numbers. Cyclopropenes 1a,14a,14b1b,14a,14b1c,14b1d,14b1e,14a1f,14b1g,14c1h,14d1i,14e1j,14d and 1k(14b,14d) were prepared according to reported procedures. The slow decomposition of some cyclopropenes was observed even in a refrigerator; thus, cyclopropenes should be used up within a few days.

3,3,6,6-Tetraphenyltricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2a)5c

To a solution of 1a (38.0 mg 0.198 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (0.14 mL, 0.196 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in an 87% yield (33.0 mg, 0.086 mmol). For the 2 mmol scale reaction, to a solution of 1a (385 mg, 2 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (1.4 mL, 1.96 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in a 92% yield (354 mg, 0.92 mmol): white solid; mp 264–265 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52–7.50 (m, 4H), 7.40–7.36 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.02 (m, 6H), 6.93–6.91 (m, 4H), 1.99 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.6, 140.6, 130.7, 128.5, 128.2, 127.3, 126.5, 126.2, 55.8, 32.7; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H25+ [M + H]+ 385.1951, found 385.1923.

3,3,6,6-Tetra-p-tolyltricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2b)

To a solution of 1b (660 mg, 3.0 mmol) in THF (7.5 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (2.4 mL, 3.3 mmol, 1.1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in a 66% yield (434 mg, 0.983 mmol): white solid; mp 239–240 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.36–7.34 (m, 4H), 7.12–7.10 (m, 4H), 6.89–6.83 (m, 8H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 2.17 (s, 6H), 1.91 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.1, 137.9, 135.7, 135.6, 130.4, 129.1, 128.8, 127.4, 55.2, 32.3, 21.2, 20.9; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C34H33+ [M + H]+ 441.2577, found 441.2580.

3,3,6,6-Tetrakis(4-methoxyphenyl)tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2c)

To a solution of 1c (86.0 mg, 0.341 mmol) in THF (0.85 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (0.25 mL, 0.350 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in a 76% yield (65.0 mg, 0.129 mmol): white solid; mp 234–235 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39–7.36 (m, 4H), 6.89–6.82 (m, 8H), 6.64–6.62 (m, 4H), 3.80 (s, 6H), 3.67 (s, 6H), 1.87 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 158.1, 157.8, 136.4, 133.3, 131.4, 128.2, 113.9, 113.5, 55.30, 55.27, 54.3, 32.5; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C34H33O4+ [M + H]+ 505.2373, found 505.2402.

3,3,6,6-Tetrakis(4-fluorophenyl)tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2d)

To a solution of 1d (256 mg, 1.12 mmol) in THF (2.8 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (0.8 mL, 1.12 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in a 90% yield (230 mg, 0.50 mmol): white solid; mp 240–241 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45–7.41 (m, 4H), 7.09–7.03 (m, 4H), 6.83–6.79 (m, 8H), 1.89 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.5 (JC–F = 245 Hz), 161.3 (JC–F = 244 Hz), 138.8 (JC–F = 29.0 Hz), 135.9 (JC–F = 28.0 Hz), 131.8 (JC–F = 7.6 Hz), 128.5 (JC–F = 8.7 Hz), 115.6 (JC–F = 21.1 Hz), 115.1 (JC–F = 21.1 Hz), 54.4, 32.7; 19F NMR (375 MHz, CDCl3) δ −115.7, −116.3; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H21F4+ [M + H]+ 457.1574, found 457.1597.

3,3,6,6-Tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2e)

To a solution of 1e (52.0 mg, 0.2 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (0.14 mL, 0.196 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in an 80% yield (42.0 mg, 0.08 mmol): white solid; mp 262–263 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39–7.33 (m, 8H), 7.08–7.06 (m, 4H), 6.77–6.75 (m, 4H) 1.91 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.1, 138.3, 132.7, 132.3, 131.9, 129.0, 128.5, 128.3, 54.7, 32.8; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H20Cl4+ [M]+ 520.0314, found 520.0321.

3,3,6,6-Tetrakis(4-bromophenyl)tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2f)

To a solution of 1f (273 mg, 0.78 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (0.56 mL, 0.78 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. The residue was treated with hexane to give a white solid, which was collected by vacuum filtration in a 77% yield (210 mg, 0.30 mmol): white solid; mp 259–260 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52–7.50 (m, 4H), 7.34–7.32 (m, 4H), 7.25–7.23 (m, 4H), 6.72–6.71 (m, 4H), 1.92 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.5, 138.7, 132.2, 131.9, 131.4, 128.7, 120.9, 120.4, 54.9, 32.8; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H20Br4+ [M]+ 695.8293, found 695.8299.

3,3,6,6-Tetracyclohexyltricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2g)

To a solution of 1g (447 mg, 2.19 mmol) in THF (5.5 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (1.56 mL, 2.19 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Recrystallization in CHCl3 and hexane gave a desired product in a 58% yield (260 mg, 0.64 mmol): white solid; mp 239–240 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3); δ 1.79–0.80 (m, 48H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 53.1, 37.9, 32.6, 31.7, 29.7, 27.7, 27.0, 26.8, 26.4 (1C overlapping); HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H49+ [M + H]+ 409.3829, found 409.3847.

Dispiro[cyclododecane-1,3′-tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane-6′,1″-cyclododecane] (2h)

To a solution of 1h (414 mg, 2.15 mmol) in THF (5.4 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (1.54 mL, 2.15 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Recrystallization in CHCl3 and hexane gave a desired product in a 37% yield (151 mg, 0.393 mmol): white solid; mp 222–223 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.62–1.55 (m, 12H), 1.48–1.25 (m, 28H), 1.10 (s, 4H), 1.03–1.00 (m, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 43.8, 30.4, 26.8, 26.5, 26.45, 26.41, 22.3, 22.2, 21.8, 21.4 (3C overlapping); HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C28H49+ [M + H]+ 385.3829, Found 385.3821.

3,6-Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)-3,6-dimethyltricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2i)

To a solution of 1i (152 mg, 0.95 mmol) in THF (3.3 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (0.95 mL, 1.33 mmol, 1.4 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using CHCl3 as an eluent gave a desired product in a 14% yield (21.3 mg, 0.0666 mmol): white solid; mp 205–206 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.20–7.17 (m, 4 H), 6.83–6.81 (m, 4 H), 3.78 (s, 6 H), 1.77 (s, 4H), 1.55 (s, 6 H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.9, 137.9, 128.8, 113.7, 55.3, 44.3, 28.4, 17.0; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C22H25O2+ [M + H]+ 321.1849, found 321.1841.

3,6-Bis(4-chlorophenyl)-3,6-dimethyltricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2j)

To a solution of 1j (278 mg, 1.69 mmol) in THF (6.0 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (1.7 mL, 2.38 mmol, 1.4 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using CHCl3 as an eluent gave a desired product in a 39% yield (109 mg, 0.33 mmol): white solid; mp 170–171 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3) δ 7.25–7.23 (m, 4H), 7.19–7.17 (m, 4H), 1.80 (s, 4H), 1.58 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.9, 131.9, 128.9, 128.4, 44.3, 28.7, 16.5; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C20H19Cl2+ [M + H]+ 329.0858, found 329.0872.

3,6-Dimethyl-3,6-di(napthalen-2-yl)tricyclo[3.1.0.02,4]hexane (2k)

To a solution of 1k (324 mg, 1.80 mmol) in THF (4.5 mL) was added 1.4 M Me3Al in hexane (1.28 mL, 1.80 mmol, 1 equiv) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 d. The reaction was stopped with 1 M HCl aq. The aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Recrystallization in CHCl3 and hexane gave a desired product in a 40% yield (128 mg, 0.36 mmol): white solid; mp 216–217 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.81–7.74 (m, 8H), 7.47–7.41 (m, 6H), 2.01 (s, 4H), 1.72 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.0, 133.5, 132.2, 127.9, 127.8, 127.6, 126.4, 126.0, 125.5, 45.1, 28.7, 16.7 (1C overlapping); HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C28H25+ [M + H] + 361.1951, found 361.1976.

1′,4′-Diphenyl-1′,4′-dihydro-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl (3a)

2a (59.0 mg, 0.154 mmol) was heated at 270 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (58.7 mg, 0.152 mmol): yellow solid; mp 235–236 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.19 (m, 20H), 6.15 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 147.2, 131.0, 128.4, 128.2, 126.3, 50.1; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H25+ [M + H]+ 385.1951, found 385.1928.

4,4″-Dimethyl-4′,4′-di-p-tolyl-4′H-1,1′:1′,1″-terphenyl (3b)

2b (99.8 mg, 0.226 mmol) was heated at 245 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 98% yield (97.8 mg, 0.222 mmol): yellow solid; mp 262–263 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.02 (broad s, 16H), 6.00 (s, 4H), 2.25 (s, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.5, 135.8, 130.9, 129.0, 128.1, 49.4, 21.1; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C34H33+ [M + H]+, 441.2577, found 441.2557.

4,4″-Dimethoxy-4′,4′-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)-4′H-1,1′:1′-1″-terphenyl (3c)

2c (98.7 mg, 0.196 mmol) was heated at 245 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (98.0 mg, 0.194 mmol): yellow solid; mp 183–184 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.14–7.12 (m, 8H), 6.83–6.79 (m, 8H), 6.05 (s, 4H), 3.79 (s, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.9, 139.6, 130.9, 129.1, 113.7, 55.3, 48.6; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C34H33O4+ [M + H]+ 505.2373, found 505.2370.

4,4″-Difluoro-4′,4′-bis(4-fluorophenyl)-4′H-1,1′:1′,1″-terphenyl (3d)

2d (71.6 mg, 0.157 mmol) as heated at 258 °C for 10 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (71.1 mg, 0.156 mmol): yellow solid; mp 220–221 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.14–7.11 (m, 8H), 6.98–6.95 (m, 8H), 6.08 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.5 (JC–F = 245 Hz), 142.4 (JC–F = 27 Hz), 130.9, 129.5 (JC–F = 7.7 Hz), 115.3 (JC–F = 21.2 Hz), 48.8; 19F NMR (375 MHz, CDCl3) δ −116.2; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H21F4+ [M + H]+ 457.1574, found 457.1577.

4,4″-Dichloro-4′,4′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)-4′H-1,1′:1′,1″-terphenyl (3e)

2e (52.5 mg, 0.101 mmol) was heated at 267 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (52.3 mg, 0.100 mmol): yellow solid; mp 267–268 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.25–7.24 (m, 8H), 7.09–7.06 (m, 8H), 6.06 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.8, 132.6, 130.8, 129.3, 128.8, 49.2; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H20Cl4+ [M]+ 520.0314, found 520.0334.

4,4″-Dibromo-4′,4′-bis(4-bromophenyl)-4′H-1,1′:1′,1″-terphenyl (3f)

2f (70.3 mg, 0.101 mmol) was heated at 265 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 98% yield (69.6 mg, 0.099 mmol): yellow solid; mp 301–302 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42–7.39 (m, 8H), 7.02–7.00 (m, 8H), 6.05 (s, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.3, 131.8, 130.7, 129.7, 120.9, 49.3; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H20Br4+ [M]+ 695.8293, found 695.8299.

1′,4′-Dicyclohexyl-[1,1′:4′,1″-tercyclohexane]-2′,5′-diene (3g)

2g (39.7 mg, 0.097 mmol) was heated at 250 °C for 10 min to give the desired product in a 98% yield (39.0 mg, 0.096 mmol): yellow solid; mp 153–154 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.50 (s, 4H), 1.86–0.90 (m, 44H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 131.7, 45.5, 44.7, 28.9, 27.5, 26.9; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H49+ [M + H]+ 409.3829, found 409.3814.

Dispiro[11.2.1115.212]octacosa-13,27-diene (3h)

2h (12.1 mg, 0.031 mmol) was heated at 273 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (11.9 mg, 0.031 mmol): white solid; mp 223–224 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.50 (s, 4H), 1.49–1.23 (m, 44H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 131.4, 38.6, 35.7, 26.9, 26.2, 22.8, 22.3, 18.9; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C28H49+ [M + H]+ 385.3829, found 385.3851.

4,4″-Dimethoxy-1′,4′-dimethyl-1′,4′-dihydro-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl (3i)

2i (21.3 mg, 0.067 mmol) was heated at 221 °C for 6 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (21.2 mg, 0.066 mmol): yellow solid; mp 163–164 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34–7.31 (m, 4H), 6.89–6.86 (m, 4H), 5.65 (s, 4H), 3.80 (s, 6 H), 1.54 (s, 6 H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.9, 139.8, 131.8, 127.7, 113.7, 55.4, 39.8, 27.8; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C22H25O2+ [M + H+] 321.1849, found 321.1831.

4,4″-Dichloro-1′,4′-dimethyl-1′,4′-dihydro-1,1′:4′,1″-terphenyl (3j)

2j (32.4 mg, 0.099 mmol) was heated at 230 °C for 30 min to give the desired products in a 98% yield (31.8 mg, 0.097 mmol): yellow solid; mp 144–145 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.54–7.16 (m, 8H), 5.65 (s, 4H), 1.53 (s, 6 H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.9, 132.1, 131.7, 128.5, 128.1, 40.2, 27.6; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, negative) calcd for C20H17Cl2– [M – H–] 327.0713, found 327.0700.

3,6-Dimethyl-3,6-di(napthalen-2-yl)cyclohexa-1,4-diene (3k)

2k (36.0 mg, 0.100 mmol) was heated at 225 °C for 10 min to give the desired product in a 99% yield (35.7 mg, 0.099 mmol): yellow solid; mp 201–202 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.85–7.80 (m, 8H), 7.60–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.45 (m, 4H), 5.81 (s, 4H), 1.73 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.8, 133.6, 132.1, 131.9, 128.1, 127.9, 127.6, 126.13, 126.07, 125.7, 124.3, 40.8, 27.7; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C28H25+ [M + H] + 361.1951, found 361.1950.

4,5′-Diphenyl-1,1′:2′,1″-terphenyl (4a)2b

To a mixture of 3a (38.9 mg, 0.101 mmol) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) was added Br2 (10 μL, 0.194 mmol, 2 equiv) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) at 0 °C. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at that temperature for 26 h. Then, to the mixture was added aq Na2S2O3. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using chloroform as an eluent gave a solid, which was washed with a minimum amount of EtOAc. The product was obtained in a 98% yield (37.7 mg, 0.098 mmol): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51 (s, 2H), 7.25–7.21 (m, 20H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.0, 139.7, 133.1, 129.9, 128.0, 126.7; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C30H23+ [M + H] + 383.1794, found 383.1773.

4,4″-Dimethyl-4′,5′-bis(4-methylphenyl)-1,1′:2′,1″-terphenyl (4b)2b

To a mixture of 3b (44.0 mg, 0.100 mmol) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) was added Br2 (10 μL, 0.194 mmol, 2 equiv) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) at 0 °C. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at that temperature for 26 h. Then, to the reaction mixture was added aq Na2S2O3. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using chloroform as an eluent gave a solid, which was washed with a minimum amount of EtOAc. The product was obtained in a 98% yield (43.1 mg, 0.098 mmol): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39 (s, 2H), 7.05–6.95 (m, 16H), 2.24 (s, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.2, 138.2, 136.1, 133.0, 129.7, 128.7, 21.1; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C34H30+ [M] + 438.2342, found 438.2335.

3,3″-Dibromo-4′,5′-bis(3-bromo-4-methoxyphenyl)-4,4″-dimethoxy-1,1′:2′,1″-terphenyl (4c)

To a mixture of 3c (51.0 mg, 0.101 mmol) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) was added Br2 (20 μL, 0.388 mmol, 4 equiv) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) at 0 °C. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at that temperature for 26 h. Then, to the reaction mixture was added aq Na2S2O3. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using chloroform as an eluent gave a solid, which was washed with a minimum amount of EtOAc. The product was obtained in a 62% yield (51.0 mg, 0.063 mmol): white solid; mp 257–258 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.49–7.48 (m, 4H), 7.37 (s, 2 H), 7.00–6.97 (m, 4H), 6.76–6.74 (m, 4H), 3.87 (s, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.9, 137.9, 134.19, 134.15, 132.6, 130.1, 111.4, 111.3, 56.2; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd for C34H26Br4O4+ [M + H]+ 814.8637, found 814.8641.

4,4″-Difluoro-4′,5′-bis(4-fluorophenyl)-1,1′:2′,1″-terphenyl (4d)2b

To a mixture of 3d (45.9 mg, 0.100 mmol) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) was added Br2 (10 μL, 0.194 mmol, 2 equiv) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) at 0 °C. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at that temperature for 26 h. Then, to the reaction mixture was added aq Na2S2O3. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using chloroform as an eluent gave a solid, which was washed with a minimum amount of EtOAc. The product was obtained in a 96% yield (43.7 mg, 0.096 mmol): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42 (s, 2H), 7.16–7.12 (m, 8H), 6.96–6.92 (m, 8H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.9 (d, JC–F = 246 Hz), 138.8, 136.5 (d, JC–F = 3.8 Hz), 132.8, 131.3 (d, JC–F = 7.7 Hz), 115.1 (d, JC–F = 21 Hz); 19F NMR (375 MHz, CDCl3) δ −115.4; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd. for C30H18F4+ [M]+ 454.1339, found 454.1331.

4,4″-Dichloro-4′,5′-bis(4-chlorophenyl)-1,1′:2′,1″-terphenyl (4e)2b

To a mixture of 3e (52.3 mg, 0.101 mmol) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) was added Br2 (10 μL, 0.194 mmol, 2 equiv) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) at 0 °C. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at that temperature for 26 h. Then, to the reaction mixture was added aq Na2S2O3. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using chloroform as an eluent gave a solid, which was washed with a minimum amount of EtOAc. The product was obtained in a 99% yield (51.9 mg, 0.100 mmol): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42 (s, 2H), 7.25–7.22 (m, 8H), 7.12–7.10 (m, 8H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.8, 138.7, 133.2, 132.7, 131.0, 128.5; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd. for C30H18Cl4+ [M]+ 518.0157, found 518.0152.

4,4″-Dibromo-4′,5′-bis(4-bromophenyl)-1,1′:2′,1″-terphenyl (4f)2a

To a mixture of 3f (70.0 mg, 0.100 mmol) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) was added Br2 (10 μL, 0.194 mmol, 2 equiv) in CCl4 (0.1 mL) at 0 °C. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at that temperature for 26 h. Then, to the reaction mixture was added aq Na2S2O3. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by silica gel column chromatography using chloroform as an eluent gave a solid, which was washed with a minimum amount of EtOAc. The product was obtained in a 96% yield (66.9 mg, 0.096 mmol): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.41–7.38 (m, 10H), 7.06–7.04 (m, 8H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.2, 138.9, 132.8, 131.5, 131.4, 121.5; HRMS-APCI-TOF (m/z, positive) calcd. for C30H19Br4+ [M + H]+ 694.8215, found 694.8201.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS (21K05076).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.2c01261.

NMR spectra and stereochemistry predictions for 2i–k (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For chiral 1,4-cyclohexadienes for transition metals, see:; a Nagamoto M.; Nishimura T. Asymmetric Transformations under Iridium/Chiral Diene Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 833–847. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Aromatization from 1,4-cyclohexadienes is one of the promising route to cycloparaphenylene derivatives, see:; b Martí-Centelles V.; Pandey M. D.; Burguete M. I.; Luis S. V. Macrocyclization Reactions: The Importance of Conformational, Configurational, and Template-Induced Preorganization. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8736–8834. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kim J.; Teo H. T.; Hong Y.; Oh J.; Kim H.; Chi C.; Kim D. Multiexcitonic Triplet Pair Generation in Oligoacene Dendrimers as Amorphous Solid-State Miniatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20956–20964. 10.1002/anie.202008533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kumar S.; Huang D.-C.; Venkateswarlu S.; Tao Y.-T. Nonlinear Polyfused Aromatics with Extended π-Conjugation from Phenanthrotriphenylene, Tetracene, and Pentacene: Syntheses, Crystal Packings, and Properties. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 11614–11622. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Steiner A.-K.; Amsharov K. Y. The Rolling-Up of Oligophenylenes to Nanographenes by a HF-Zipping Approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14732–14736. 10.1002/anie.201707272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Liu J.; Ma J.; Zhang K.; Ravat P.; Machata P.; Avdoshenko S.; Hennersdorf F.; Komber H.; Pisula W.; Weigand J. J.; Popov A. A.; Berger R.; Müllen K.; Feng X. π-Extended and Curved Antiaromatic Polycyclic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7513–7521. 10.1021/jacs.7b01619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For the synthesis of 1,4-cyclohexadienes, see:; a Fedyushin P. A.; Peshkov R. Y.; Panteleeva E. V.; Tretyakov E. V.; Beregovaya I. V.; Gatilov Y. V.; Shteingarts V. D. Purposeful regioselectivity control of the Birch reductive alkylation of biphenyl-4-carbonitrile. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 842–851. 10.1016/j.tet.2017.12.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pogula V. D.; Wang T.; Hoye T. R. Intramolecular [4 + 2] Trapping of a Hexadehydro-Diels-Alder (HDDA) Benzyne by Tethered Arenes. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 856–859. 10.1021/ol5037024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Bennett N. J.; Elliott M. C.; Hewitt N. L.; Kariuki B. M.; Morton C. A.; Raw S. A.; Tomasi S. Diastereoselective alkylation reactions of 1-methylcyclohexa-2,5-diene-1-carboxylic acid. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3859–3865. 10.1039/c2ob25211b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bramborg A.; Linker T. Regioselective Synthesis of Alkylarenes by Two-Step ipso-Substitution of Aromatic Dicarboxylic Acids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 5552–5563. 10.1002/ejoc.201200823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Iwasaki H.; Tsutsui N.; Eguchi T.; Ohno H.; Yamashita M.; Tanaka T. A novel samarium(II)-mediated tandem spirocyclization onto an aromatic ring. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1770–1772. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Bramborg A.; Linker T. Selective Synthesis of 1,4-Dialkylbenzenes from Terephthalic Acid. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2195–2199. 10.1002/adsc.201000322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Ohno H.; Okumura M.; Maeda S.; Iwasaki H.; Wakayama R.; Tanaka T. Samarium(II)-Promoted Radical Spirocyclization onto an Aromatic Ring. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7722–7732. 10.1021/jo034767w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Kiwus R.; Schwarz W.; Roßnagel I.; Musso H. Hydrogenolyse kleiner Kohlenstoffringe, XV über die Hydrierung von Dispiro[2.2.2.2]deca-4,9-dien. Chem. Ber. 1987, 120, 435–438. 10.1002/cber.19871200330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Kraakman P. A.; Nibbering E. T. J.; De Wolf W. H.; Bickelhaupt F. Flash vacuum thermolysis of dispiro[2.2.n.2]alkadienes. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 5109–5124. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87687-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Nakano T.; Endo K.; Ukaji Y. Silver-Catalyzed Allylation of Ketones and Intramolecular Cyclization through Carbene Intermediates from Cyclopropenes Under Ambient Conditions. Chem. Asian. J. 2016, 11, 713–721. 10.1002/asia.201501196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nakano T.; Endo K.; Ukaji Y. Copper(I)-Catalyzed Carbometalation of Nonfunctionalized Cyclopropenes Using Organozinc and Grignard Reagents. Synlett 2015, 26, 671–675. 10.1055/s-0034-1379959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Nakano T.; Endo K.; Ukaji Y. Catalytic Tandem C–C Bond Formation/Cleavage of Cyclopropene for Allylzincation of Aldehydes or Aldimine Using Organozinc Reagents. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 1418–1421. 10.1021/ol500208r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Endo K.; Nakano T.; Fujinami S.; Ukaji Y. Chemoselective Carbozincation of Cyclopropene for C–C Bond Formation and Cleavage in a Single Operation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 6514–6518. 10.1002/ejoc.201301026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Sherrill W. M.; Rubin M. Rhodium-Catalyzed Hydroformylation of Cyclopropenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13804–13809. 10.1021/ja805059f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peganova T. A.; Petrovskii P. V.; Isaeva L. S.; Kravtsov D. N.; Furman D. B.; Kudryashev A. V.; Ivanov A. O.; Zotova S. V.; Bragin O. V. Bis(triphenylphosphine)-5-nickela-3,3,7,7-tetramethyl-trans-tricyclo[4.1.0.02,4]heptane. J. Organomet. Chem. 1985, 282, 283–289. 10.1016/0022-328X(85)87179-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Binger P.; McMeeking J.; Schäfer H. Reaktionen der Cyclopropene, VI. Nickel(0)-katalysierte [2 + 1]-Cycloadditionen von 3,3-Diorganylcyclopropenen mit elektronenarmen Olefinen. Chem. Ber. 1984, 117, 1551–1560. 10.1002/cber.19841170423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer C. D.; Wadsworth D. H.; Perkins W. C. Photodimerization of Some Cyclopropenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 861–869. 10.1021/ja00784a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Smith M. A.; Richey H. G. Jr. Reactions of Cyclopropenes with Organoaluminum Compounds and Other Organometallic Compounds: Formation of Ring-Opened Products. Organometallics 2007, 26, 609–616. 10.1021/om060766t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Richey H. G. Jr.; Kubala B.; Smith M. A. Evidence for a carbonium ion rearrangement in the reaction of triisobutylaluminum and 1,3,3-trimethylcyclopropene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 3471–3474. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)81934-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Binger P.; Schäfer H. Lewissäure-katalysierte cyclodimerisation von 3,3-dimethylcyclopropen. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 4673–4676. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91049-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Liese J.; Hampp N. Thermal [2 + 2] Cycloreversion of a Cyclobutane Moiety via a Biradical Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 2927–2932. 10.1021/jp111577j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Beadle P. C.; Golden D. M.; King K. D.; Benson S. W. Pyrolysis of cyclobutane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 2943–2947. 10.1021/ja00764a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trecker D. J.; Henry J. P. Cumulative Effects in Small Ring Cleavage Reactions. A Novel Cyclobutane Rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 902–905. 10.1021/ja01059a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R. G.; Lindow D. F.; Rabideau P. W. Metal-Ammonia Reduction. XIII. Regiospecificity of Reduction and Reductive Methylation in the Terphenyl Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 5412–5420. 10.1021/ja00770a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Taşkesenlioǧlu S.; Daştan A.; Dalkılıç E.; Güney M.; Abbasoǧlu R. Low and high temperature bromination of 2,3-dicarbomethoxy and 2,3-dicyano benzobarrelene: unexpected substituent effect on bromination. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 141–150. 10.1039/B9NJ00372J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Garcia-Garibay M.; Scheffer J. R.; Trotter J.; Wireko F. Addition of bromine gas to crystalline dibenzobarrelene: An enantioselective carbocation rearrangement in the solid state. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1485–1488. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)80331-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciganek E.; Calabrese J. C. β-Iodo Ketones by Prévost Reaction of Vinyl Carbinols. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 4439–4443. 10.1021/jo00119a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajaz A.; McLaughlin E. C.; Skraba S. L.; Thamatam R.; Johnson R. P. Phenyl Shifts in Substituted Arenes via Ipso Arenium Ions. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9487–9495. 10.1021/jo301848g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Guo P.; Sun W.; Liu Y.; Li Y.-X.; Loh T.-P.; Jiang Y. Stereoselective Synthesis of Vinylcyclopropa[b]indolines via a Rh-Migration Strategy. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5978–5983. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li H.; Zhang M.; Mehfooz H.; Zhu D.; Zhao J.; Zhang Q. Highly convergent modular access to poly-carbon substituted cyclopropanes via Cu(I)-catalyzed three-component cyclopropene carboallylation. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 3387–3391. 10.1039/C9QO00902G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Shintani R.; Iino R.; Nozaki K. Rhodium-Catalyzed Polymerization of 3,3-Diarylcyclopropenes Involving a 1,4-Rhodium Migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7849–7852. 10.1021/ja5032002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Young P. C.; Hadfield M. S.; Arrowsmith L.; Macleod K. M.; Mudd R. J.; Jordan-Hore J. A.; Lee A.-L. Divergent Outcomes of Gold(I)-Catalyzed Indole Additions to 3,3-Disubstituted Cyclopropenes. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 898–901. 10.1021/ol203418u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sherrill W. M.; Kim R.; Rubin M. Improved preparative route toward 3-arylcyclopropenes. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 8610–8617. 10.1016/j.tet.2008.06.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.