Abstract

Objectives

Tocilizumab showed trends for improving skin fibrosis and prevented progression of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis (SSc) in randomised controlled clinical trials. We aimed to assess safety and effectiveness of tocilizumab in a real-life setting using the European Scleroderma Trial and Research (EUSTAR) database.

Methods

Patients with SSc fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/EULAR 2013 classification criteria, with baseline and follow-up visits at 12±3 months, receiving tocilizumab or standard of care as the control group, were selected. Propensity score matching was applied. Primary endpoints were the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) and FVC at 12±3 months compared between the groups. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of progressive/regressive patients for skin and lung at 12±3 months.

Results

Ninety-three patients with SSc treated with tocilizumab and 3180 patients with SSc with standard of care fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Comparison between groups did not show significant differences, but favoured tocilizumab across all predefined primary and secondary endpoints: mRSS was lower in the tocilizumab group (difference −1.0, 95% CI −3.7 to 1.8, p=0.48). Similarly, FVC % predicted was higher in the tocilizumab group (difference 1.5 (−6.1 to 9.1), p=0.70). The percentage of progressive/regressive patients favoured tocilizumab over controls. These results were robust regarding the sensitivity analyses. Safety analysis confirmed previously reported adverse event profiles.

Conclusion

Although this large, observational, controlled, real-life EUSTAR study did not show significant effectiveness of tocilizumab on skin and lung fibrosis, the consistency of direction of all predefined endpoints generates hypothesis for potential effectiveness in a broader SSc population.

Keywords: systemic sclerosis, autoimmune diseases, biological therapy

What is already known about this subject?

Two placebo-controlled randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) with tocilizumab have been conducted in systemic sclerosis (SSc). Both RCTs were recruiting a highly enriched population of patients with inflammatory, early, diffuse, skin-progressive SSc. Main messages from these two RCTs were trend for improving skin fibrosis and prevention of worsening of lung fibrosis over placebo.

What does this study add?

No significant effectiveness of tocilizumab was shown in this broader, multicentre, propensity score matched, controlled observational, heterogeneous, non-enriched real-life SSc population from the large European Scleroderma Trial and Research registry.

The consistency of direction in all predefined primary and secondary endpoints generates hypothesis for potential effectiveness in a broader SSc population rather than in highly selective RCT.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

Adds important information from real-life to the existing RCTs with tocilizumab by generating hypothesis that should be confirmed in a prospective RCT with broader SSc population.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare but potentially lethal autoimmune connective tissue disease characterised by inflammation, fibrosis and microvasculopathy.1 It is a multiorgan disease involving the skin and various internal organs.2 3 Mortality is high, especially if lungs, heart or kidneys are involved.4 5 Even though new trials on various disease-modifying drugs have been conducted over the last years, therapy is still mainly based on treatment of organ-specific complications.6–9

Several preclinical and translational studies have shown that interleukin 6 (IL-6) might play an important role in SSc, in particular when inflammation is driving the disease process.10 11 IL-6 serum concentrations in patients with diffuse cutaneous (dc) SSc are significantly higher than in healthy individuals.12 Serum IL-6 levels correlate with disease severity and mortality, and are associated with higher C reactive protein (CRP) levels and platelet counts.12 13 Inhibition of IL-6 prevented the development of inflammation-driven dermal fibrosis induced by bleomycin in mice, but did not show effects in the non-inflammatory TSK-1 model.14 15

Tocilizumab (TCZ) is a humanised monoclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor.16 Two randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials (RCTs) with tocilizumab have been conducted in SSc. In the phase II faSScinate trial, a trend for improving skin fibrosis over placebo was found. Exploratory analysis revealed a possible stabilisation of FVC.17 18 The phase III focuSSced study confirmed the trend on skin fibrosis without reaching statistical significance. Stabilisation of lung fibrosis, this time with FVC as a key secondary endpoint and additional HRCT quantification, was observed.19 Both RCTs were recruiting a highly enriched population of patients with inflammatory, early, diffuse, skin-progressive SSc.

Thus, while these data are promising and have resulted in the approval of tocilizumab for SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) by the FDA, little is known about the effects of tocilizumab in a broader SSc population. Data from large ‘real-life’ registries could better determine the effects of tocilizumab on a more heterogeneous, non-enriched population. The aim of the present study was to estimate the treatment effect and safety of tocilizumab in patients with SSc, as compared with patients not treated with tocilizumab in a large real-life observational cohort study using the European Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database.

Material and methods

Study design

This study was designed as a multicentre, propensity score matched no-treatment controlled observational study. Data for tocilizumab-treated patients were requested from the EUSTAR network using a case report form (CRF) designed by the lead investigators.20–22 The treating physicians made the treatment decision according to their local practice and routine. Requested data included demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment details and adverse events (see online supplemental file for CRF). Queries were sent to centres for missing data and data clarification. The matched control group was formed from patients prospectively registered in the EUSTAR database, not treated with tocilizumab. Database extraction was done on 30 October 2017.

rmdopen-2022-002477supp001.pdf (663.8KB, pdf)

The local ethic committees of the participating centres approved the data collection. All patients signed informed consent forms when required by the local ethics committees. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for good clinical practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and registered at www.drks.de under DRKS00015537, including a predefined detailed statistical analysis plan (provided in online supplemental file).

Inclusion criteria and selection of control patients

Inclusion criteria for the treatment group were definite SSc according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/EULAR 2013 criteria, treatment with tocilizumab and age ≥17 years.23 24 For analysis of primary and secondary outcomes, only patients with at least three applications of tocilizumab and follow-up at 12±3 months were included. Safety data were analysed for all patients. Additional/different inclusion criteria for the control group were absence of tocilizumab therapy, disease duration <35 years to meet the tocilizumab group and date of observations after 1 January 2010 (start of the online EUSTAR database). If multiple visits existed for one control patient, we used the most recent one, and this approach was revisited in the sensitivity analysis.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcomes were the difference at 12±3 months of follow-up between the tocilizumab and the control group in the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) for skin fibrosis and the FVC for pulmonary function compared. Both outcomes were addressed separately, but a single matched set of patient treated-control pairs was used for analysis.

Secondary outcomes were the percentage of progressive patients for skin fibrosis (increase in mRSS of 5 points and 25%), lung fibrosis (decrease in either FVC ≥10% or FVC ≥5% and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide DLCO ≥15%), and the percentage of regressive patients for skin and for lung (decrease in mRSS of 5 points and 25% or increase in either FVC ≥10% or FVC ≥5% and DLCO ≥15%).25–27 Presence of ILD was defined as evidence for ILD on HRCT or X-ray as judged be the local investigator. Safety measures were assessed as percentage of patients suffering from adverse events.

Subgroup analysis

Predefined subgroup analyses included mRSS ≥10 versus mRSS <10 at baseline and dcSSc versus limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) (for the outcome mRSS) and FVC ≥80% versus FVC <80% at baseline and FVC <80% and X-ray or high-resolution CT (HRCT) positive versus FVC ≥80% and X-ray or HRCT negative (for the outcome FVC).

Exploratory subgroup analysis included disease duration ≤3 years versus disease duration >3 years and C reactive protein (CRP) ≤5 mg/L versus CRP >5 mg/L and HRCT and/or X-ray positive versus HRCT and/or X-ray negative.

Subgroup analyses were preceded by a test for interaction. Subgroup results were only reported if there was evidence for differential treatment effect between subgroups (if p<0.05).

Propensity score matching

Based on expert opinion and considering the published literature, the following variables were identified as confounders in an interdisciplinary team discussion (SJ, OD, SK, UH, KS): age at diagnosis, gender, disease subtype (diffuse or limited), baseline mRSS, FVC, DLCO, co-therapy with immunosuppressive disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (either one of prednisone >10 mg/day, methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil), rituximab within 6 months before baseline, disease duration in years, and year of treatment.

The propensity score was the estimated probability of a patient in the EUSTAR database to receive tocilizumab. To estimate the propensity score, a logistic regression model was fitted to the confounders.28 29 We used a nearest neighbour 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) algorithm.30 Balancing of baseline characteristics before and after matching was assessed with descriptive statistics, the standardised mean difference (SMD) and exploratory p values. If the SMD was smaller than 0.1, the distribution of confounders was assumed to be balanced.31

Handling of missing values

The procedure for handling of missing values of potential control patients and treated patients varied. The following variables were used in the multiple imputation model as predictor variables: age in years (numeric), gender (binary), subtype (binary), prednisone (binary), methotrexate (binary), azathioprine (binary), mycophenolate mofetil (binary), rituximab (biologic) within 6 months before baseline (binary), disease duration in years (numeric), year of treatment (numeric) as well as baseline and follow-up of mRSS, FVC and DLCO (numeric). Age, disease duration in years, baseline and follow-up mRSS, FVC and DLCO were imputed using predictive mean matching. Subtype, prednisone, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and rituximab (biologic) within 6 months before baseline were imputed via logistic regression and co-therapy was passively imputed. Missing data in the primary outcomes (mRSS and FVC) in potential control patients led to listwise exclusion of these patients, whereas none of the patients in the TCZ group were excluded due to missing parameters in the primary outcomes. Covariates with a percentage of missing values of more than 50% were a priori defined to be excluded from the analysis. For the remaining variables, missingness patterns were assessed. As we assumed that data were missing completely at random or missing at random, multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) was used for confounders and outcomes at baseline as well as follow-up. The number of multiply imputed data sets was set to 60 (m=60).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and SD or median and IQR for continuous variables, and number and percentage of total for categorical variables.

The primary outcomes, mRSS and FVC, were compared with linear mixed-effects models to account for the correlation between the matched samples. The results from multiply imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rule. We used a generalised linear mixed model with binomial family with a random intercept accounting for pair membership of matched treated and control patients.

Binary secondary outcomes were compared with ORs and 95% CIs between treatment groups; again, these were corrected for correlation in matched pairs due to matching. Between-group differences for continuous outcomes were estimated and reported with 95% CIs. The effect measures for the binary outcomes are marginal ORs. The significance level for confirmatory p values was set to 0.05.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to address pre-processing decisions (selection of most recent vs random observation for control patients with multiple suitable time intervals), as well as matching algorithm (nearest neighbour vs exact matching) and robustness of the results. For further details and specifications, see the statistical analysis plan (online supplemental file).

All data analyses were conducted using R, V.4.1.2 for Windows32 and the packages tableone, mice, MatchIt, reshape2, dplyr, mitools, lsmeans, VIM, cobalt, ggplot2, lmer and glmer. Results of the study were reported according to the STROBE guidelines.33

Results

Baseline characteristics of tocilizumab and control patients

Data from 109 patients with SSc treated with tocilizumab were collected from 25 EUSTAR centres. Of these 109 patients, 12 were excluded for the effectiveness analysis due to missing follow-up at 12±3 months and 4 due to absence of at least three tocilizumab applications. Route of administration was intravenous in 65 (69.9%), subcutaneous in 13 (14.0%) and no information available in 15 (16.1%).

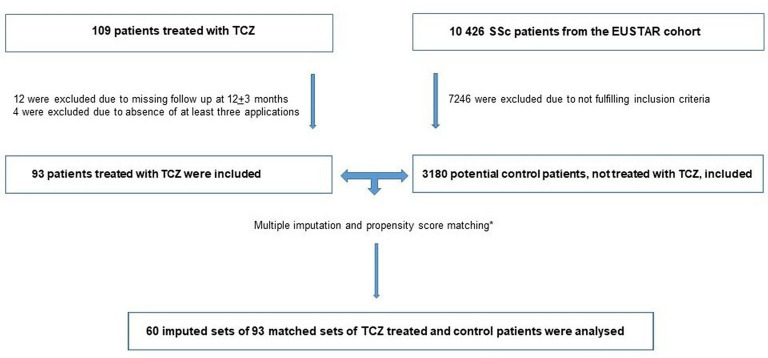

From the EUSTAR database, 3180/10 426 patients were fulfilling the inclusion criteria for the control group. There were 14.0% missing data in baseline mRSS and 40.9% at follow-up. For FVC, the corresponding percentages were 25.8% at baseline and 45.2% at follow-up. Through application of MICE and PSM on these patients, 60 imputed sets of 93 matched sets of treated and control patients were generated (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram. *Matching criteria: age at diagnosis, gender, subtype (limited/diffuse), baseline modified Rodnan skin score, baseline FVC, baseline diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, co-therapy immunosuppressive disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (either one of prednisone >10 mg/day, methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil), rituximab (biologic) within 6 months before baseline, disease duration (years), year of treatment. TCZ, tocilizumab; EUSTAR, European Scleroderma Trial and Research.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the tocilizumab group and the control group before and after multiple imputation and propensity score matching can be found in table 1. As expected, the proportion of patients with the diffuse subtype, the prevalence of increased inflammation markers (CRP/erythrocyte sedimentation rate above normal limits) and patients with arthritis, and overlap to rheumatoid arthritis (online supplemental table S1) was high, reflecting the typical real-life indications for tocilizumab at time of the study. Indeed, the majority of physicians selected tocilizumab as a treatment because of SSc-associated arthritis (table 2). After multiple imputation and propensity score matching, the pooled SMD of baseline covariates between the two groups was <0.1 for all matching variables. Therefore, baseline covariates were considered balanced and further adjustment was not needed (online supplemental table S2). In addition, online supplemental table S4 shows baseline characteristics with SMD and p values for a randomly drawn data set after multiple imputation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics before and after multiple imputation and propensity score matching

| TCZ-treated patients | Patients without TCZ, potential controls | ||||

| Before MICE and PSM | Randomly drawn data set after MICE and PSM | ||||

| N=93 | N=3180 | SMD | N=93 | SMD | |

| Age (mean±SD; years) | 50.9±13.5 | 56.8±13.7 | 0.43 | 48.4±15.1 | 0.18 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (n, %) | 73 (78.5) | 2637 (82.9) | 0.11 | 73 (78.5) | <0.001 |

| Systemic sclerosis subtype | |||||

| Diffuse (n, %) | 49 (57.6.) | 1319 (41.6) | 0.33 | 52 (55.9) | 0.02 |

| Immunosuppressive co-therapy | |||||

| Yes | 70 (80.5) | 882 (29.4) | 1.20 | 75 (80.6) | <0.001 |

| Prednisone ≥10 mg/day (n, %) | 41 (48.8) | 214 (7.5) | 1.04 | 16 (17.2) | 0.68 |

| Cyclophosphamide (n, %) | – | 146 (5.0) | – | 6 (7.2) | – |

| Methotrexate (n, %) | 36 (50.0) | 336 (11.3) | 0.92 | 31 (33.3) | 0.22 |

| Azathioprine (n, %) | 6 (9.2) | 198 (6.7) | 0.09 | 20 (21.5) | 0.45 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil (n, %) | 4 (6.7) | 232 (7.8) | 0.05 | 18 (19.4) | 0.39 |

| D-Penicillamine (n, %) | – | 21 (0.7) | – | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Rituximab within 6 months (n, %) | 1 (1.1) | 42 (1.3) | 0.02 | 1 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Imatinib (n, %) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | – |

| TNF-alpha antagonist (n, %) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (0.3) | 0.08 | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Abatacept (n, %) | 1 (1.1) | – | – | 1 (1.1) | – |

| Disease duration (mean±SD, years) | 6.4±5.4 | 10.6±7.5 | 0.65 | 6.2±4.9 | 0.04 |

| Autoantibodies positive | |||||

| ANA (n, %) | 73 (92.4) | 2789 (95.7) | 0.14 | 78 (96.3) | 0.17 |

| ACA (n, %) | 12 (16.7) | 1054 (38.0) | 0.49 | 10 (13.5) | 0.09 |

| Anti-Scl-70 (n, %) | 54 (65.1) | 1013 (36.3) | 0.60 | 42 (53.8) | 0.23 |

| CRP ≥5 mg/L (n, %) | 49 (56.3) | 250 (8.0) | 1.21 | 11 (12.1) | 1.054 |

| ESR >25 mm/h (n, %) | 38 (54.3) | 867 (30.4) | 0.50 | 29 (34.9) | 0.40 |

| Baseline mRSS (median, IQR) | 14.0 (6.0, 22.2) | 6.0 (2.0, 11.0) | 0.79 | 11.0 (6.0, 21.0) | 0.07 |

| Baseline FVC % predicted (mean±SD) | 84.9±19.6 | 95.8±21.6 | 0.52 | 88.0±22.8 | 0.01 |

| Baseline DLCO % predicted (mean±SD) | 62.2±22.4 | 67.5±19.9 | 0.25 | 65.1 (19.0) | 0.12 |

| HRCT or X-ray positive for ILD (n, %) | 49 (73.1) | 1276 (48.3) | 0.53 | 37 (47.4) | 0.54 |

| Digital ulcers (n, %) | 16 (17.8) | 274 (12.2) | 0.16 | 12 (18.5) | 0.02 |

| Joint synovitis (n, %) | 44 (62.0) | 320 (10.2) | 1.28 | 14 (15.4) | 1.09 |

| Tendon friction rubs (n, %) | 25 (31.2) | 184 (6.0) | 0.69 | 11 (12.1) | 0.48 |

Demographics and clinical characteristics are defined according to EUSTAR criteria.39 The standardised mean difference (SMD) is a measure for assessing balance of distributions, values <0.1 indicate balanced covariates between matched samples.

ACA, anti-centromere antibodies; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; anti-Scl-70, anti-topoisomerase antibodies; CRP, C reactive protein; DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FVC, forced vital capacity; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MICE, multiple imputation using chained equations; mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score; PSM, propensity score matching; RNA-pol III, anti-polymerase III; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Table 2.

Indication for treatment with TCZ

| n=93 | |

| Joints | 67 (72.0%) |

| Skin | 25 (26.9%) |

| Lung | 20 (21.5%) |

| Myositis | 2 (2.2%) |

| Heart | 1 (1.1%) |

| Tendinitis | 2 (2.2%) |

| Vasculitis | 1 (1.1%) |

| Coexisting Castelman-like disease | 1 (1.1%) |

| Joints only | 50 (53.8%) |

| Joints and skin | 6 (6.5%) |

| Joints and lung | 7 (7.5%) |

| Joints and myositis | 1 (1.1%) |

| Joints, skin and lung | 3 (3.2%) |

| Skin only | 8 (8.6%) |

| Skin and lung | 4 (4.3%) |

| Skin and heart | 1 (1.1%) |

| Skin and tendovaginitis | 2 (2.2%) |

| Skin, lung and myositis | 1 (2.2%) |

| Lung only | 5 (5.4%) |

| Vasculitis only | 1 (1.1%) |

| Coexisting Castelman-like disease only | 1 (1.1%) |

| NA | 3 (3.2%) |

NA, not available; TCZ, tocilizumab.

No covariates had a percentage of missing values >50%; therefore, no covariate needed to be excluded.

Effects of tocilizumab on skin and lung fibrosis

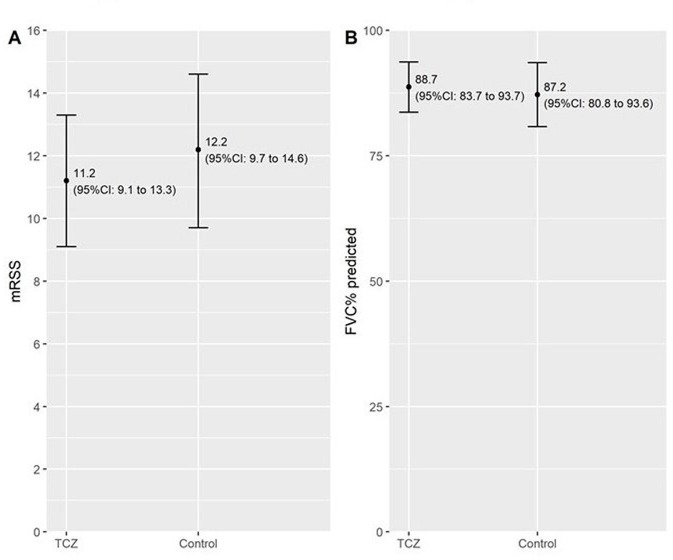

Follow-up mRSS as a measure of skin fibrosis after 12±3 months of therapy was lower in the tocilizumab group (mean estimate of 11.2, 95% CI 9.1 to 13.3) compared with the control group (12.2, 9.7 to 14.6, p=0.48). This effect was stable regardless of the pre-processing decisions and the matching algorithm (see sensitivity analyses).

Similar to skin fibrosis, we could consistently see a tendency towards a benefit of tocilizumab therapy for lung fibrosis as measured by FVC per cent predicted, which did not reach statistical significance. FVC at follow-up was 88.7 (83.7 to 93.7)% predicted in the tocilizumab group versus 87.2 (80.8 to 93.6)% predicted in the control group (p=0.70). Results from the pre-defined main analysis of primary outcomes are shown in table 3 and figure 2. Accordingly, the mean estimated difference (with 95% CI) between groups for skin fibrosis measured by mRSS was lower in TCZ −1.0 (−3.7 to 1.8) and higher in TCZ for lung fibrosis measured by FVC (% predicted) 1.5 (−6.1 to 9.1).

Table 3.

Primary outcomes at follow-up (12±3 months)

| mRSS | FVC (% predicted) | ||

| TCZ, n=93 | Mean estimate (95% CI) | 11.2 (9.1 to 13.3) | 88.7 (83.7 to 93.7) |

| Controls | Mean estimate (95% CI) | 12.2 (9.7 to 14.6) | 87.2 (80.8 to 93.6) |

| Between-group difference | Mean estimate (95% CI) | −1.0 (−3.7 to 1.8) | 1.5 (−6.1 to 9.1) |

| P value | 0.48 | 0.70 |

These results represent our main analysis with a nearest neighbour matching algorithm and selection of most recent observation in control patients with multiple possible baseline observations.

CI, confidence interval; FVC, forced vital capacity; mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Figure 2.

Modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) and FVC at follow-up (12±3) months. (A) Primary outcome mRSS estimate (95% CI) tocilizumab (TCZ) vs control between-group mean difference p=0.48. (B) Primary outcome FVC% predicted estimate (95% CI) TCZ vs control between-group difference p=0.70.

Secondary outcomes

The percentage of progressive patients for skin fibrosis as well as for lung fibrosis (online supplemental table S3) was lower under tocilizumab therapy as compared with the control group without reaching statistical significance. The OR for mRSS was 0.7 (0.1 to 4.8, p=0.74) and 0.8 (0.3 to 2.2, p=0.63) for progression of ILD as measured by decline in FVC.

No significant effectiveness of tocilizumab could be shown for percentage of regressive patients under therapy, with an OR of 1.1 (0.4 to 2.7, p=0.86) for regression of mRSS and 1.5 (0.6 to 3.8, p=0.41) for increase of FVC (table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes: progression/regression of mRSS and decline/increase of FVC

| mRSS | FVC | |||

| Progression | Regression | Decline | Increase | |

| Estimated treatment effect of TCZ with OR (95% CI) | 0.7 (0.1 to 4.8) | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.7) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.2) | 1.5 (0.6 to 3.8) |

| P values | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.41 |

These results represent our main analysis with a nearest neighbour matching algorithm and selection of most recent observation in control patients with multiple possible baseline observations.

CI, confidence interval; FVC, forced vital capacity; mRSS, modified Rodnan skin score; OR, odds ratio; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Interaction tests for differential treatment effects between the subgroups showed no evidence for subgroup effects (online supplemental table S5), suggesting that either the results are not different or the sample size is too small for patients with mRSS ≥10 versus mRSS <10, dcSSc versus lcSSc (for the outcome mRSS) as well as FVC ≥80% versus FVC <80% and FVC ≥80% and X-ray or HRCT positive versus FVC <80% and X-ray or HRCT negative (for the outcome FVC).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis addressed multiple observations in patients with more than one suitable time interval as well as different matching algorithms. The sensitivity analyses were not significant, but showed consistency of direction in the differences between tocilizumab and control observed in the main analysis (summarised in online supplemental tables S6–S9).

Safety of tocilizumab

Safety parameters of all 109 patients were assessed at 0, 3, 6 and 12 months of follow-up. Assessed exposed patient years (PY) were 93.8. A total of 90 adverse events (AEs) (96 per 100 PY) and 17 serious adverse events (SAEs) (18.1 per 100 PY) were registered. SAEs are summarised in table 5. Among the SAEs, there was one death and eight events resulted in discontinuation of tocilizumab.

Table 5.

Summary of serious adverse events over the total follow-up duration

| Patient n | Age years | Report at visit (month) | Event | Discontinuation of tocilizumab | Hospitalisation |

| Patient 5 | 42 | 12 | Severe thrombocytopenia | No | No |

| Patient 39 | 45 | 6 | Toe necrosis and infection | Yes | Yes |

| Patient 39 | 45 | 12 | Pneumonitis (after stop of TCZ) | – | Yes |

| Patient 43 | 68 | 6 | Atrial flutter | Yes | No |

| Patient 49 | 32 | 12 | Digital ulcer with osteomyelitis | No | NA |

| Patient 50 | 41 | 3 | Allergic reaction | Yes | No |

| Patient 50 | 41 | 3 | Influenza | Yes | Yes |

| Patient 69 | 41 | 3 | Renal crisis | Yes | Yes |

| Patient 69 | 41 | 6 | Thrombophlebitis (after stop of TCZ) | – | Yes |

| Patient 70 | 58 | 6 | Acute heart failure | Yes | NA |

| Patient 70 | 58 | 12 | Amputation last phalanx Dig I foot (after stop of TCZ) | – | NA |

| Patient 71 | 76 | 6 | Deep vein thrombosis | No | NA |

| Patient 80 | 56 | 0 | Severe allergic reaction | Yes | NA |

| Patient 83 | 58 | 3 | Bilateral keratitis | Yes | No |

| Patient 92 | 63 | 3 | Pneumonia | No | Yes |

| Patient 92 | 63 | 12 | Pneumonia | No | Yes |

| Patient 97 | 18 | 12 | Sudden cardiac death | – | NA |

–, Information is not applicable; NA, data are not available; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Most frequently observed adverse events were disorders of the blood and lymphatic system like leucopenia and thrombocytopenia (32 events, 34.2 per 100 PY). However, 31 of 32 were mild (leucocytes >1500/µL, thrombocytes >50 000/µL). Twenty-five infections were registered (26.7 per 100 PY). Superinfection of digital ulcers was reported in four patients. Elevated transaminases were reported (18 events, 19.2 per 100 PY), yet only five were >2× upper limit of normal.

Discussion

Our multicentre, propensity score matched, controlled observational study in the EUSTAR database did not show significant effectiveness of tocilizumab on skin and lung fibrosis. Subgroup analysis did not show evidence for differences in effectiveness across subpopulations, although sample sizes might have been too small to detect differences in subgroups. However, a remarkable finding of this study was the consistent, although not significant, point estimates in favour of tocilizumab across all predefined primary and secondary endpoints. Furthermore, additional sensitivity analyses were consistent. The data used in this study were from a large registry including a general population of patients with SSc. Although the estimated effects of tocilizumab were not significant, the results of the study may be seen as hypothesis generating for a potential effectiveness of tocilizumab in broader patient populations than studied in the highly selected and enriched RCT populations. The hypothesis that tocilizumab might also be effective in broader patient populations needs now to be tested in further large prospective RCTs.

Our study has to be interpreted in light of the results from the two RCTs conducted in SSc with a high evidence level.17 19 In both RCTs, there was a consistent trend for the primary endpoint mRSS favouring tocilizumab. Considering that in these RCTs, the study population was strongly enriched for mRSS dynamics, the current confirmation of these results in a much less selected observational real-life cohort is encouraging. Regarding lung fibrosis, both RCTs showed strong effects of tocilizumab on FVC as a secondary or exploratory endpoint. An important result of both trials was the successful enrichment for a strong decline of FVC in the placebo groups using a combination of inclusion criteria such as early dcSSc, increased inflammatory markers and recent progression of skin fibrosis.34 35 The resulting progression of FVC was comparable with that seen in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and allowed demonstrating the strong difference of FVC in the tocilizumab group compared with placebo with a stabilised FVC. This strong difference of FVC would be more difficult to be shown with less enriched patient populations and slower progression of FVC in the placebo/control group such as in the Senscis trial7 or in the present study.

Considering safety, our study did not reveal significant new potential threats of tocilizumab. The profile of adverse events was similar to that of other studies investigating safety parameters in patients with tocilizumab.17 36 37 There was a predominance of infections among the SAEs (5/17) and well-known laboratory abnormalities such as thrombocytopenia or elevated transaminases among the AEs (49/90). However, while previous studies suggested that serious infections might be higher in patients with SSc treated with tocilizumab than in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, our study could not confirm this.17 38 Of particular interest are infections of digital ulcers, but with only four infections associated with digital ulcers (two considered serious) observed in 93.8 patient years, application of tocilizumab does not seem to dramatically increase ulcer infections.

Our study has limitations. Despite the relatively large number of patients in the EUSTAR database, there were much less patients available who received treatment with tocilizumab. Therefore, uncertainty increased and the power of the study was not high enough to allow definite conclusions. In general, a higher number of patients is needed to show a treatment effect in observational cohorts than in RCTs because there is more heterogeneity. In addition, the leading indication to treat patients with SSc with tocilizumab was presence of arthritis and/or overlap to rheumatoid arthritis at time of the present study and the associated disease characteristics with, for example, longer disease duration further decrease the likelihood that a significant treatment effect can be observed, at least for mRSS. After publication of the two tocilizumab RCTs, this practice pattern has likely changed and many more patients with SSc-ILD are treated nowadays with tocilizumab. Despite propensity scoring matching for key parameters, some features associated with disease progression, such as increased inflammatory markers and arthritis, were more common in the tocilizumab patients than in controls. However, this should lead to more progression in the tocilizumab group and supports a potential positive effect of tocilizumab in this study. Due to a small number of patients in the subgroups, it was not possible to include all variables into a single imputation model. Therefore, the subgroup results are biased towards null and should be interpreted with caution. Another potential limitation is that we matched for any immunosuppressive treatment, but not for single immunosuppressive drugs. If the immunosuppressive drugs are having very different effects on outcomes than others, this matching would not have been perfect. However, numbers would have been too small for matching of single immunosuppressive drugs and results would have not been meaningful. Moreover, the absolute numbers of AE observed in this trial should be considered with caution, as they were collected retrospectively, are therefore likely underestimated, and a control group for the AE was missing. Finally, it must be strongly emphasised that observational studies can provide important signals, which may be used for hypothesis generation and might contribute to generalisation of trial results to real-life setting, but are never of high enough evidence to prove drug effectiveness. Still, the current study adds important supportive data for effectiveness of tocilizumab in SSc in real-life setting consistent with data from the two RCTs.

Strengths of the study include the robust, predefined and preregistered study protocol (www.drks.de), with a detailed statistical analysis plan involving expert biostatisticians and applying propensity score matching and using optimised matching procedures, while accounting for missing data with a multiple imputation approach. All major decisions regarding methodological approaches were re-evaluated in sensitivity analyses. The results remained stable indicating that the methodology or assumptions did not affect the results of this study. This study reports the largest number of patients with SSc treated with tocilizumab with similar numbers as in the phase III focuSSced study.19 In addition, data were collected from a real-life setting avoiding over-enrichment as in standard RCTs. Controls were derived from the very large, prospectively collected EUSTAR database.

Conclusion

Taken together, in this large, propensity score matched, controlled observational real-life EUSTAR study, we could not show significant effectiveness of tocilizumab for skin and lung fibrosis across all predefined primary and secondary endpoints. However, the consistency of direction of all predefined endpoints generates hypothesis for potential effectiveness in a broader SSc population than the highly selective population included in the RCTs. This hypothesis needs to be confirmed by prospective RCTs with broader patient populations. Safety analysis confirmed previous AE profiles without new signals.

Footnotes

Collaborators: EUSTAR Collaborators: Principal Investigator Affiliation; Ulrich Walker, Basel (Switzerland): Radim Becvar, Prague (Czech Republic); Maurizio Cutolo, Genova (Italy); Patricia E Carreira, Madrid (Spain); László Czirják, Pecs (Hungary); Michele Iudici, Geneva (Switzerland); Eugene J Kucharz, Katowice (Poland); Bernard Coleiro, Balzan (Malta); Dominique Farge Bancel, Paris (France); Roger Hesselstrand, Lund (Sweden); Mislav Radic, Split (Croatia); Raffaele Pellerito, Torino (Italy); Nemanja Damjanov, Belgrade (Serbia); Jörg Henes, Tübingen (Germany); Vera Ortiz-Santamaria, Granollers Barcelona (Spain); Stefan Heitmann, Stuttgart (Germany); Paul Hasler, Aarau (Switzerland); Bojana Stamenkovic, Niska Banja (Serbia); Carlo Francesco Selmi, Rozzano, Milano (Italy); Mohammed Tikly, Johannesburg (South Africa); Lidia P Ananieva, Moscow (Russia); Ulf Müller-Ladner, Bad Nauheim (Germany); Merete Engelhart, Hellerup (Denmark); Carlos de la Puente, Madrid (Spain); Cord Sunderkötter, Münster (Germany); Francesca Ingegnoli, Milano (Italy); Luc Mouthon, Paris (France); Francesco Paolo Cantatore, Foggia (Italy); Susanne Ullman, Copenhagen (Denmark); Maria Rosa Pozzi, Monza (Italy); Piotr Wiland, Wroclaw (Poland); Marie Vanthuyne, Brussels (Belgium); Juan Jose Alegre-Sancho, Valencia (Spain); Brigitte Krummel-Lorenz, Frankfurt (Germany); Kristine Herrmann, Dresden (Germany); Ellen De Langhe, Leuven (Belgium); Branimir Anic, Zagreb (Croatia); Sule Yavuz, Altunizade-Istanbul (Turkey); Carolina de Souza Müller, Curitiba (Brazil); Svetlana Agachi, Chisinau (Republic of Moldova); Thierry Zenone, Valence (France); Simon Stebbings, Dunedin (New Zealand); Alessandra Vacca, Monserrato (CA)(Italy); Lisa Stamp, Christchurch (New Zealand); Kamal Solanki, Hamilton (New Zealand); Douglas Veale, Dublin (Ireland); Esthela Loyo, Santiago (Dominican Republic); Mengtao Li, Beijing (China); Walid Ahmed Abdel Atty Mohamed, Alexandria (Egypt); Edoardo Rosato, Roma (Italy); Cristina-Mihaela Tanaseanu, Bucharest (Romania); Rosario Foti, Catania (Italy); Codrina Ancuta, Iasi (Romania); Britta Maurer, Bern (Switzerland); Paloma García de la Peña Lefebvre, Madrid (Spain); Jean Sibilia, Strasbourg (France); Ira Litinsky, Tel-Aviv (Israel); Francesco Del Galdo, Leeds (UK); Goda Seskute, Vilnius (Lithuania); Lesley Ann Saketkoo, New Orleans (USA); Eduardo Kerzberg, Buenos Aires (Argentina); Doron Rimar, Haifa (Israel); Camillo Ribi, Lausanne (Switzerland); Vivien M. Hsu, New Brunswick (USA); Thierry Martin, Strasbourg (France); Lorinda S Chung, Stanford (USA); Tim Schmeiser, Wuppertal-Elberfeld (Germany); Dominik Majewski, Poznan (Poland); Vera Bernardino, Lisboa (Portugal); Piercarlo Sarzi Puttini, Milano (Italy).

Contributors: The manuscript has been seen and approved by all coauthors and contributors. Prof. Dr. med. Oliver Distler is a guarantor and accepts full responibility for the work and the conduct of the study, has access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: Data analysis was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd; Basel, Switzerland.

Disclaimer: Roche did not have any access to primary data, and was not involved in data analysis, data interpretation and writing of this article.

Competing interests: SK, SJ, ME, FC, ES, SR, VC, YB-M, MS, AMG, KR-P, FJL-L; PIN, AG, YS, LB, VS, TS, AG: none. CB reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli-Lilly. Research Grants from Gruppo Italiano Lotta alla Sclerodermia (GILS), Foundation for Research in Rheumatology (FOREUM), European Scleroderma Trial and Research (EUSTAR), New Horizon Fellowship. AMG has received research funding and/or consulting fees from Abbvie, GenevaRompharm, Novartis and Boehringer Ingelheim. SV received consultancy for BI Global and BI Italy spa. PA reports personal fees (consultancies) from Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, non-financial support from CSL Behring, SOBI, Janssen, Roche, Sanofi, Pfizer. NH has received lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Sanofi, Roche. VR has/had personal fees or received research funding from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Corbus, Inventiva, Roche. JJAS reports personal fees and/or research funding from Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, MSD, Corbus, Inventiva, and GSK, outside of the submitted work. IC reports personal fees or research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Roche, Kern, BMS, Sanofi-Aventis, Roche, UCB and BioCAT. MET has had consultancy relationships and/or has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche and Sanofi in the area of potential treatments of scleroderma and its complications. EZ reports speaker honoraria and consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline. CD reports personal fees or research funding from Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, Sanofi-Aventis, Galapagos, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, CSL Behring, Corbus, Acceleron, Horizon, ARXX Therapeutics. RMI had received consultancy and speaker fee from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Roche. JHWD has consultancy relationships with Active Biotech, Anamar, ARXX, AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Galapagos, GSK, Inventiva, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. JHWD has received research funding from Anamar, ARXX, BMS, Bayer Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cantargia, Celgene, CSL Behring, Galapagos, GSK, Inventiva, Kiniksa, Sanofi-Aventis, RedX, UCB. JHWD is stock owner of 4D Science. AMHV has received research funding and/or consulting fees and/or other remuneration from Actelion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Bayer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, ARXX, Lilly, Janssen and Medscape. MK has received grants or personal fees from AbbVie, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Astellas, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Corbus, Eisai, Galapagos, Janssen, Kissei, MBL, Mochida, Nippon Shinyaku, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer and Tanabe-Mitsubishi Pharma. YA has had consultancy relationships and/or has received research funding from Alpine, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche, Medsenic, Menarini and Sanofi in the area of potential treatments of scleroderma and its complications. OD has/had consultancy relationship with and/or has received research funding from and/or has served as a speaker for the following companies in the area of potential treatments for systemic sclerosis and its complications in the last three calendar years: Abbvie, Acceleron, Alcimed, Amgen, AnaMar, Arxx, AstraZeneca, Baecon, Blade, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Corbus, CSL Behring, 4P Science, Galapagos, Glenmark, Horizon, Inventiva, Janssen, Kymera, Lupin, Medscape, Miltenyi Biotec, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Novartis, Prometheus, Roivant, Sanofi and Topadur. Patent issued “mir-29 for the treatment of systemic sclerosis” (US8247389, EP2331143).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

the EUSTAR collaborators:

Radim Becvar, Maurizio Cutolo, Patricia E Carreira, László Czirják, Michele Iudici, Eugene J Kucharz, Bernard Coleiro, Dominique Farge Bancel, Roger Hesselstrand, Mislav Radic, Raffaele Pellerito, Nemanja Damjanov, Jörg Henes, Stefan Heitmann Vera Ortiz-Santamaria, Paul Hasler, Bojana Stamenkovic, Carlo Francesco Selmi, Mohammed Tikly, Lidia P Ananieva, Ulf Müller-Ladner, Merete Engelhart, Carlos de la Puente, Cord Sunderkötter, Francesca Ingegnoli, Luc Mouthon, Francesco Paolo Cantatore, Susanne Ullman, Maria Rosa Pozzi, Piotr Wiland, Marie Vanthuyne, Juan Jose Alegre-Sancho, Brigitte Krummel-Lorenz, Kristine Herrmann, Ellen De Langhe, Branimir Anic, Sule Yavuz, Carolina de Souza Müller, Svetlana Agachi, Thierry Zenone, Simon Stebbings, Alessandra Vacca, Lisa Stamp, Kamal Solanki, Douglas Veale, Esthela Loyo, Mengtao Li, Walid Ahmed Abdel Atty Mohamed, Edoardo Rosato, Cristina-Mihaela Tanaseanu, Rosario Foti, Codrina Ancuta, Britta Maurer, Paloma Garcíadela Peña Lefebvre, Jean Sibilia, Ira Litinsky, Francesco Del Galdo, Goda Seskute, Lesley Ann Saketkoo, Eduardo Kerzberg, Doron Rimar, Camillo Ribi, Vivien M Hsu, Thierry Martin, Lorinda S Chung, Tim Schmeiser, Dominik Majewski, Vera Bernardino, and Piercarlo Sarzi Puttini

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Anonymised data might be available from OD at the Department of Rheumatology, University Hospiztal Zurich, University of Zurich, Switzerland on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the ethic committee of the Canton of Zurich (KEK-ZH), Switzerland (BASEC Nr. 2017-01935).

References

- 1. Varga J, Trojanowska M, Kuwana M. Pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis: recent insights of molecular and cellular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017;2:137–52. 10.5301/jsrd.5000249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMahan ZH, Hummers LK. Systemic sclerosis-challenges for clinical practice. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:90–100. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denton CP. Systemic sclerosis: from pathogenesis to targeted therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:S3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubio-Rivas M, Royo C, Simeón CP, et al. Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:208–19. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elhai M, Meune C, Boubaya M, et al. Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1897–905. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khanna D, Distler JHW, Sandner P, et al. Emerging strategies for treatment of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2016;1:186–93. 10.5301/jsrd.5000207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2518–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1903076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1327–39. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann-Vold A-M, Maher TM, Philpot EE, et al. The identification and management of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: evidence-based European consensus statements. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e71–83. 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30144-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muangchan C, Pope JE. Interleukin 6 in systemic sclerosis and potential implications for targeted therapy. J Rheumatol 2012;39:1120–4. 10.3899/jrheum.111423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muangchant C, Pope JE. The significance of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31:122–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan K, Xu S, Nihtyanova S, et al. Clinical and pathological significance of interleukin 6 overexpression in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1235–42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Lauretis A, Sestini P, Pantelidis P, et al. Serum interleukin 6 is predictive of early functional decline and mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2013;40:435–46. 10.3899/jrheum.120725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Desallais L, Avouac J, Fréchet M, et al. Targeting IL-6 by both passive or active immunization strategies prevents bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R157. 10.1186/ar4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kitaba S, Murota H, Terao M, et al. Blockade of interleukin-6 receptor alleviates disease in mouse model of scleroderma. Am J Pathol 2012;180:165–76. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hashizume M, Tan S-L, Takano J, et al. Tocilizumab, a humanized anti-IL-6R antibody, as an emerging therapeutic option for rheumatoid arthritis: molecular and cellular mechanistic insights. Int Rev Immunol 2015;34:265–79. 10.3109/08830185.2014.938325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khanna D, Denton CP, Jahreis A, et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab in adults with systemic sclerosis (faSScinate): a phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:2630–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00232-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Distler O, Distler JHW. Tocilizumab for systemic sclerosis: implications for future trials. Lancet 2016;387:2580–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00622-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khanna D, Lin CJF, Furst DE, et al. Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:963–74. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30318-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jordan S, Distler JHW, Maurer B, et al. Effects and safety of rituximab in systemic sclerosis: an analysis from the European Scleroderma Trial and Research (EUSTAR) group. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1188–94. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castellví I, Elhai M, Bruni C, et al. Safety and effectiveness of abatacept in systemic sclerosis: the EUSTAR experience. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020;50:1489–93. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elhai M, Boubaya M, Distler O, et al. Outcomes of patients with systemic sclerosis treated with rituximab in contemporary practice: a prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:979–87. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2737–47. 10.1002/art.38098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1747–55. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maurer B, Graf N, Michel BA, et al. Prediction of worsening of skin fibrosis in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis using the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1124–31. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu W, Jordan S, Becker MO, et al. Prediction of progression of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: the SPAR model. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1326–32. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffmann-Vold A-M, Allanore Y, Alves M, et al. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:219–27. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, et al. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:1149–56. 10.1093/aje/kwj149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shadish WR, Clark MH, Steiner PM. Can nonrandomized experiments yield accurate answers? A randomized experiment comparing random and nonrandom assignments. J Am Stat Assoc 2008;103:1334–44. 10.1198/016214508000000733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ho DE, Imai K, King G. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw 2011;42:28. 10.18637/jss.v042.i08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. The R project for statistical computing. Available: https://www.r-project.org

- 33. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu W, Jordan S, Graf N, et al. Progressive skin fibrosis is associated with a decline in lung function and worse survival in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis in the European Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:648–56. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoffmann-Vold A-M, Allanore Y, Alves M, et al. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:219–27. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Zuber Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1110–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Atsumi T, Fujio K, Yamaoka K, et al. Safety and effectiveness of subcutaneous tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a real-world clinical setting. Mod Rheumatol 2018;28:780–8. 10.1080/14397595.2017.1416760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tocilizumab: postmarketing surveillance of 7901 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan. J Rheumatol 2014;41:15–23. 10.3899/jrheum.130466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walker UA, Tyndall A, Czirják L, et al. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials And Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:754–63. 10.1136/ard.2006.062901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2022-002477supp001.pdf (663.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Anonymised data might be available from OD at the Department of Rheumatology, University Hospiztal Zurich, University of Zurich, Switzerland on reasonable request.