Abstract

With the increasing prevalence of traumatic brain injury (TBI), the need for reliable and valid methods to evaluate TBI has also increased. The purpose of this study was to establish the validity and reliability of a new comprehensive assessment of TBI, the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) Assessment of TBI (MMA-TBI). The participants in this study were post-deployment, combat exposed veterans. First, MMA-TBI outcomes were compared with those of independently conducted clinical TBI assessments. Next, MMA-TBI outcomes were compared with those of a different validated TBI measure (the Ohio State University TBI Identification method [OSU-TBI-ID]). Next, four TBI subject matter experts independently evaluated 64 potential TBI events based on both clinical judgment and Veterans Administration/Department of Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guidelines. Results of the MMA-TBI algorithm (based on VA/DoD clinical guideline) were compared with those of the subject matter experts. Diagnostic correspondence with independently conducted expert clinical evaluation was 96% for lifetime TBI and 92% for deployment-acquired TBI. Consistency between the MMA-TBI and the OSU-TBI-ID was high (κ = 0.90; Kendall Tau = 0.94). Comparison of MMA-TBI algorithm results with those of subject matter experts was high (κ = 0.97–1.00). The MMA-TBI is the first TBI interview to be validated against an independently conducted clinical TBI assessment. Overall, results demonstrate the MMA-TBI is a highly valid and reliable instrument for determining TBI based on VA/DoD clinical guidelines. These results support the need for application of standardized TBI criteria across all diagnostic contexts.

Keywords: concussion, deployment, structured interview, TBI, veteran

Introduction

History of traumatic brain injury (TBI) has implications for expected outcomes and appropriate treatment for post-deployment service members and veterans. There is amplified need to accurately and consistently measure potential TBI events in both clinical and research settings because of the combination of high prevalence of TBI in recent conflicts and increasing concern regarding the potential long-term outcomes following TBI.1 TBI is a historic event, and the clinical interview is currently considered the gold-standard approach to diagnosing remote TBI.2 Different interview approaches offer various strengths and weaknesses. In research, structured and semistructured interviews are typically used to improve efficiency and standardization of the data gathered.3

The Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury (MMA-TBI) is a semistructured interview designed to assess TBI across the lifespan according to the Veterans Administration/Department of Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (VA/DoD CPG). There are several existing semistructured interviews to evaluate remote TBI (e.g., Ohio State University TBI Identification Method [OSU-TBI-ID],4 Virginia Commonwealth University Retrospective Concussion Diagnostic Interview [VCU-rCDI],5 and Donnelly's Structured Interview for TBI Diagnosis6). However, a shared major weakness of these interviews is that detailed TBI information is only queried for specific time frames or a limited number of injuries.7 The Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) addresses some of these issues. The BAT-L evaluates the entire lifespan of injuries by time period (i.e., pre-military, military, post-military), but specifically focuses on only the three most severe events during each period, limiting the conclusions that can be reached regarding effects of the number of TBIs experienced.8

The MMA-TBI was developed to obtain information about all potentially concussive events, providing a fully comprehensive evaluation of TBI across the lifespan. To improve efficiency, only information relevant to determining if a potentially concussive event resulted in TBI according to the VA/DoD CPG is gathered. Although additional types of information (e.g., additional orthopedic injuries, time to return to work) may provide context or be useful in specific situations, they are not evaluated by the MMA-TBI because they are not relevant to determining if an event meets criteria for TBI. The MMA-TBI is accompanied by an interpretive algorithm developed to standardize diagnostic decisions based on the VA/DoD CPG.9 The purpose of this study was to: (1) establish the validity of the MMA-TBI diagnostic outcomes, and; (2) evaluate the reliability of the algorithm's diagnostic decisions compared with those of experienced clinicians.

Methods

Participants

Data for these analyses were collected as part of an independent Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC) study (Study 34) investigating functional and neurobiological outcomes to combat veterans of experiencing a blast or explosion in Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND). Veterans were initially screened by telephone and then completed an in-person assessment visit for full characterization and confirmation of reported eligibility status before being enrolled in a subsequent imaging visit. Data used in the present analyses were collected at the assessment visit. Informed consent was obtained prior to all study activities. All study procedures were approved by the local institutional review board.

Eligibility criteria for the assessment visit included at least one OEF/OIF/OND deployment that involved combat exposure (defined as any positive response [a score of >17] on the Deployment Risk and Resiliency Inventory-2, Module D10); English fluency; being ≥18 years of age; having the ability to complete study tasks; and having the ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were a history of moderate or severe TBI; any penetrating brain injury; and presence of neurological disorder, severe mental illness, dementia, current substance abuse, or psychotic symptoms. Because this study involved neuroimaging, participants were additionally excluded if they were pregnant or unable to participate in imaging because of an inability to tolerate being in an enclosed space for brain imaging or the presence of ferrous metal other than fillings, including orthodonture or implanted objects known to generate magnetic fields (e.g., prosthetic devices, pacemakers, neurostimulators).

MMA-TBI interview

The MMA-TBI is a semistructured interview providing a comprehensive evaluation of potentially concussive events across the lifespan. The MMA-TBI gathers information for each event, to provide a determination regarding the presence or absence of TBI according to the VA/DoD CPG.9,11 The MMA-TBI begins with screening questions to ascertain the presence of any potentially concussive events at any point in the life of the interviewee (see Appendix 1; text in italics are instructions or reminders and normal text in quotes are what is asked by the interviewer.). Each potentially concussive event is further evaluated using a standard process (see Appendix 2). First, individuals are asked to provide a narrative description of the event and any effects on functioning. If possible, interviewers make ratings of specific criteria (e.g., loss of consciousness [LOC], alteration of consciousness [AOC]) based on provided information. Structured follow-up questions are then asked to obtain any additional information necessary to complete ratings for all criteria. All potentially concussive events across the lifespan are queried, including the mechanism (e.g., blunt force, blast, acceleration-deceleration) and context (e.g., during military service, during deployment), as well as information on the key VA/DoD CPG for determining the diagnosis of TBI including the presence and duration of LOC, post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), and AOC. Structural neuroimaging and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) results are included in the VA/DoD CPG but are typically unavailable when evaluating TBI in the chronic state, and were not included as criteria evaluated by the MMA-TBI. The presence and duration of post-concussive symptoms (e.g., headache, vision changes, balance problems) immediately following the injury are also evaluated.

Evaluating potentially concussive events across the lifespan may become problematic when an individual has experienced a particularly high number of events. The MMA-TBI addresses this by characterizing multiple similar events with a single representative multiple exposure rating. For example, an individual who routinely participates in boxing matches likely has had many potentially concussive events of a similar nature and outcome. The multiple exposure rating captures details representing a typical event, which can then be applied across all similar events. This process significantly reduces the amount of time required to capture information about many highly similar and repetitive events. For the current study, this process was not used for events involving LOC (i.e., all events involving LOC are evaluated individually, not as part of a multiple exposure rating). Inclusion of this mechanism requires additional training to ensure that this process is applied consistently and accurately across interviewers.

Algorithm

An algorithm was developed to determine whether an event resulted in a TBI as defined by the VA/DoD CPG9 (page 8, Table A-1 in the VA/DoD CPG). These criteria include: (1) any period of LOC, (2) any period of decreased level of consciousness, (3) any alteration in mental state at time of injury (e.g., confusion, disorientation, slowed thinking, AOC), and (4) any period of PTA. The algorithm also provides a determination of TBI severity (mild, moderate, or severe) using the duration of each symptom based on the VA/DoD CPG. The results of this algorithm are used as the outcome variable for the MMA-TBI for all analyses.

Establishing validity of the MMA-TBI

Clinical TBI evaluations

Validity was evaluated by comparing results of the MMA-TBI with an independent clinical assessment by a TBI expert. The VA conducts specialized clinical evaluations of individuals who screen positive for a history of TBI and are currently experiencing associated symptoms. These evaluations are typically conducted by a physician or mid-level provider. These evaluations follow a national template for specific data points that are reported, in addition to a full clinical evaluation. Medical records of all study participants were reviewed to determine if such an evaluation had occurred, and if so, if it concluded that the individual had experienced a TBI. The MMA-TBI is the first TBI interview to compare results with independent clinical assessments.

Potentially concussive events for comparison

From all reported potentially concussive events across the 342 participants who completed the interview visit, 64 potentially concussive events were selected by J.A.R. for review by four raters (R.D.S., H.M.M., R.A.H., J.R.B.) and comparison with the OSU-TBI-ID. No rater was involved in obtaining the data used in the current analyses. Events were selected in the order in which the data were obtained, allowing more than one event to be selected per participant. Events were selected to be balanced across outcome (TBI or no TBI according to VA/DoD CPG determined by J.A.R.) as well as those occurring during deployment or outside of deployment.

OSU-TBI-ID

Outcomes of the MMA-TBI were compared with those of the OSU-TBI-ID following methods used by Fortier and coworkers to develop the BAT-L.8 The OSU-TBI-ID is a semistructured interview evaluating TBI and was the first interview considered to be a validated method of assessing TBI.4 Fortier and coworkers used information obtained during the BAT-L interview to complete the OSU-TBI-ID and calculate a summary score. BAT-L outcomes were converted to a comparable scale for analyses, and inter-rater agreement between the two summary scores was calculated. The same method was applied to the MMA-TBI. Using the rating scales presented by Fortier and coworkers, a study team member was provided with information obtained from the interview for the 64 potentially concussive events (described previously), including the case report forms and notes. Diagnostic conclusions from the interview were not provided. This information was used to calculate the OSU-TBI-ID summary score. The MMA-TBI outcomes were converted to a comparable scale using the criteria presented in Fortier and coworkers with one exception. The criteria presented by Fortier and coworkers for the BAT-L do not allow classification of events with LOC of <5 min. Therefore, the criterion for a rating of 3 was amended from LOC between 5 and 30 min to LOC present for <30 min.

Clinician ratings

Following methods used by Walker and coworkers5 in the development of the VCI-rCDI, an independent review and interpretation of interview data was conducted by a panel of expert clinicians. Clinician raters were diverse and included two board-certified neuropsychologists (H.M.M, R.D.S.) with 6 and 7 years of TBI experience respectively, a board-certified behavioral neurologist (J.R.B.) with 6 years of TBI experience, and a board-certified neuropsychiatrist (R.A.H.] with >25 years of TBI experience. Each rater was provided with information obtained from the 64 potentially concussive events (described previously), including the case report forms and notes. Diagnostic conclusions from the interview were not provided to raters. Raters were instructed to make two determinations. First, “is this event consistent with a TBI based on the provided VA/DoD CPG?” Second, “is this event consistent with a TBI based on your own clinical judgment?” Each rater was provided a separate data file, and raters were blind to responses from other raters as well as to the algorithm classification.

Statistical analysins

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Validity was first assessed by comparing outcomes of the clinical TBI evaluation and the MMA-TBI. Correspondence between a positive clinical TBI evaluation and the MMA-TBI results was calculated. Positive TBI evaluations were selected because the time frame of these evaluations can fluctuate, sometimes reporting only deployment and military events. Therefore, when the clinical evaluation is positive, it is certain that a TBI occurred at some point in the participant's lifetime. However, when the clinical evaluation is negative, it remains possible that a TBI occurred at some point in the individual's life outside of the time frame on which the evaluation focused. It was not possible to contact the evaluating providers for the clinical TBI evaluations to obtain insight into their diagnostic process, as the providers in these positions change over time.

Next, validity was assessed by comparing the MMA-TBI and OSU-TBI-ID summary scores. Following the methods Fortier and coworkers used for the BAT-L, the Cohen kappa and Kendall tau coefficients were calculated between these summary scores.

Finally, reliability and validity of the MMA-TBI algorithm was assessed by calculating simple kappa statistics among raters and the algorithm. Kappa was calculated among raters' clinical judgment and the MMA-TBI algorithm, and then among raters' criteria rating (applying the VA/DoD CPG) and the algorithm. Chi-square analysis was conducted to evaluate the effect of context on outcomes. For each rater, that person's rating (TBI present/absent) was contrasted against the context of the event (deployment/non-deployment).

Results

Clinical TBI evaluations

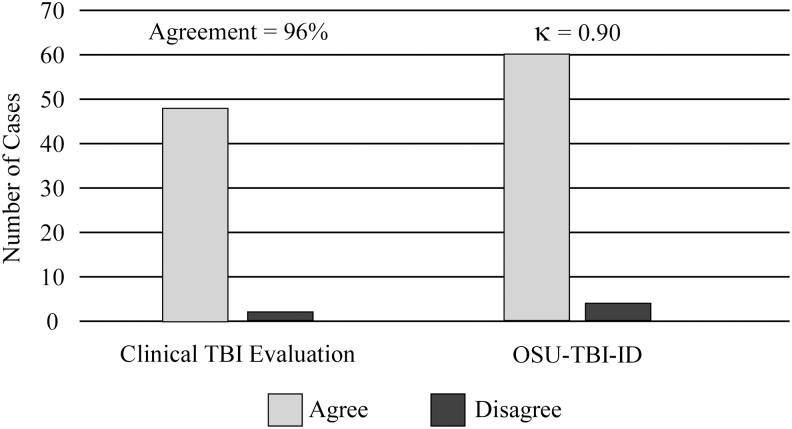

Clinical TBI evaluations were available for 61 participants and positive (i.e., TBI history present) for 51. Demographic information for this sample is presented in Table 1. The high rate of positive outcomes is unsurprising, as patients are screened and only those with a high likelihood of injury are referred for an evaluation. There was 96% (49 consistent/51 participants) agreement between MMA-TBI lifetime outcomes and positive clinical TBI evaluation outcomes, as shown in Figure 1. When using MMA-TBI deployment outcomes, there was 92% (47 consistent/51 participants) agreement with clinical TBI evaluation outcomes. These results demonstrate a high level of consistency between determinations of the MMA-TBI and an independently conducted clinical assessment by a TBI specialist, providing strong evidence for the validity of MMA-TBI diagnostic outcomes.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| |

Mean (SD), range or n (%) |

Mean (SD), range or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual item Sample (n = 49) | Specialized TBI evaluation Sample (n = 51) | |

| Age (years) | 40.61 (10.01), 26–62 | 38.24 (8.51), 26–58 |

| Education (years) | 14.84 (2.16), 9–20 | 14.41 (1.59), 12–18 |

| Number of deployments | 2.47 (1.49), 1–7 | 2.39 (1.34), 1–7 |

| Male | 42 (85.71%) | 49 (96.08%) |

| Minority | 20 (40.82%) | 16 (31.37%) |

| Branch of service | ||

| Air Force | 4 (8.16%) | 0 |

| Army | 33 (67.35%) | 37 (72.55) |

| Marine Corps | 6 (12.24%) | 12 (23.53) |

| Navy | 6 (12.24) | 2 (3.92) |

| Rated events per person | ||

| One | 39 (79.59%) | N/A |

| Two | 7 (14.29%) | N/A |

| Three | 1 (2.04%) | N/A |

| Four | 2 (4.08%) | N/A |

Individual Item Sample characteristics provided are for the 49 participants from whom the 64 rated potential TBI events were collected. Rated events are the number of rated events per participant. Specialized TBI evaluation sample characteristics are provided for the 51 participants with an evaluation indicating a history of TBI.

SD, standard deviation; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

FIG. 1.

Concordance rates of the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury (MMA-TBI) with independently conducted clinical TBI evaluation and the Ohio State University TBI Identification method (OSU-TBI-ID). These results demonstrate that the MMA-TBI is highly consistent with other methods of identifying TBI, providing strong support for the validity of the MMA-TBI.

Potentially concussive events for comparisons

A total of 64 potentially concussive events were selected from 49 participants. Although most (n = 39, 79.59%) participants only had a single potential concussive event selected for these analyses, 10 participants (20.41%) had up to four events included. Most of the 49 participants were white (59.18%), male (85.71%), and Army veterans (67.35%). Demographic information for the sample is reported in Table 1.

OSU-TBI-ID method

Consistency between the OSU-TBI-ID and the MMA-TBI summary scores was high, indicated by a simple Kappa of 0.90 and Kendall Tau of 0.94, and shown in Figure 1. Disagreements between the instruments occurred for 4/64 ratings. These disagreements occurred because of the OSU-TBI-ID rating any event without LOC as ≤2. In contrast, the MMA-TBI ratings can increase if AOC or PTA is particularly long, as was the case with the four discordant ratings. These results demonstrate a high level of consistency between the MMA-TBI and an existing validated TBI interview, providing strong support for the validity of the MMA-TBI diagnostic outcomes.

Clinician ratings

Classification decisions for presence or absence of TBI based on both clinical judgment and application of VA/DoD CPG by rater are reported in Table 2. Chi-square analyses revealed that neither clinical judgment ratings nor criteria ratings were affected by deployment status (i.e., potential concussion occurring during deployment) for any rater. This suggests that the likelihood of raters classifying potentially concussive events as a TBI was not significantly influenced by deployment status.

Table 2.

Classification of Selected Events (n = 64) by Clinician Raters

| Clinical judgment |

VA/DoD CPG criteria rating |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI | No TBI | TBI | No TBI | |

| Rater 1 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Rater 2 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 31 |

| Rater 3 | 24 | 40 | 32 | 32 |

| Rater 4 | 41 | 23 | 32 | 32 |

Numbers represent the number of the total 64 events classified into each category (traumatic brain injury [TBI] or no TBI), based either on clinical judgment or the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline (VA/DoD CPG) criteria for classification of TBI.

The MMA-TBI algorithm displayed excellent agreement with outcomes when clinicians were asked to apply the VA/DoD CPG, with Kappa scores ranging from 0.97 to 1.0 (see Table 3), disagreeing on only a single event with a single rater. This level of agreement suggests that the algorithm performs as well as expert clinicians in applying the VA/DoD CPG to determine the presence or absence of TBI for a given event. Kappa scores between the algorithm and individual raters based on clinical judgment ranged from 0.72 to 1.0 (see Table 3). This was likely related to the poor agreement among raters when using clinical judgement compared with when asked to apply the VA/DoD CPG.

Table 3.

Kappa Scores among Raters for Both Clinical Judgment and VA/DoD CPG Criteria Ratings (n = 64 Events)

| Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Rater 3 | Rater 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical judgment | ||||

| Rater 1 | — | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| Rater 2 | 0.97 | — | 0.72 | 0.75 |

| Rater 3 | 0.75 | 0.72 | — | 0.50 |

| Rater 4 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.50 | — |

| Algorithm | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| VA/DoD CPG criteria rating | ||||

| Rater 1 | — | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.97 | — | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Rater 3 | 1.00 | 0.97 | — | 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | — |

| Algorithm | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Reported numbers are kappa outcomes between raters. Clinical judgment allowed raters to utilize the same criteria that they would use in clinic to determine if an event should be considered to have resulted in traumatic brain injury (TBI). Criteria rating instructed raters to only utilize the provided Veterans Administration/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline (VA/DoD CPG) criteria for definition of a TBI. Algorithm refers to the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) Assessment of TBI (MMA-TBI) algorithm based on VA/DoD CPG criteria.

Post-hoc analyses

Debriefing interviews with raters identified that Rater 4 applied the updated 2016 VA/DoD CPG when making clinical judgments. The resulting clinical categorizations were discrepant from Rater 4's research criteria ratings and algorithm results. To explore this, the algorithm was updated to reflect the 2016 VA/DoD CPG11 by including relevant post-concussive/soft-sign symptoms captured by the interview. The kappa statistic between this updated algorithm and the clinical judgment of Rater 4 was 1.0. This demonstrates that the interview successfully captures enough data to permit the algorithm to be adapted to changes in diagnostic criteria. This also demonstrates excellent reliability of TBI classification among clinicians when defined and operationalized definitions are available.

Discussion

This study presents a new semistructured interview for comprehensively evaluating TBI across the lifespan according to established VA/DoD CPG.9,11 The MMA-TBI performed well when compared with outcomes of independent clinical evaluations, TBI subject matter experts, and an existing validated interview. Overall, these results provide strong support for the validity and reliability of the MMA-TBI as an instrument to accurately and precisely determine the presence or absence of TBI according to VA/DoD CPG.

The MMA-TBI is the first TBI interview to be validated against independently conducted clinical assessments by TBI experts. The MMA-TBI was highly consistent with results of a specialized clinical TBI evaluation conducted in the VA, suggesting that this instrument has strong criterion validity. The consistency was highest when using lifetime results of the MMA-TBI; however, results were also strong when using only deployment events identified by the MMA-TBI. No other TBI interview has been validated against independently conducted clinical evaluations, which are currently considered the gold-standard method of TBI diagnosis.

Following the methods used to validate the BAT-L, a direct comparison was conducted between the MMA-TBI and the OSU-TBI-ID, demonstrating a high level of consistency between the interviews. Differences were present for only 4 out of 64 events and were primarily related to the classification algorithms used by each instrument. The OSU-TBI-ID was developed based on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definition of TBI, which relies heavily on LOC to differentiate severity. In contrast, the MMA-TBI was designed to follow VA/DoD CPG, which incorporate duration of AOC and PTA into severity ratings. The four discrepant cases all had extended AOC or PTA in the absence of LOC. Even with these differences in TBI definition, the overall results between the measures were highly consistent, further supporting the validity of the MMA-TBI.

Following the methods used to validate the VCI-rCDI, the MMA-TBI algorithm results were compared with the ratings of four board-certified clinician raters with expertise in TBI. Raters' determination if events met VA/DoD CPG criteria for TBI were contrasted against algorithm results. Agreements were near perfect, with disagreement on one event with one rater (Table 3). This demonstrates that the algorithm applies VA/DoD CPG as well as subject matter experts, providing further support for the validity and reliability of the MMA-TBI.

High variability was seen among raters when applying their own clinical judgement to determine the presence of TBI, with kappa scores ranging from 0.50 to 0.97. Typically, kappa scores <0.90 are considered unacceptable in a research study. This outcome is consistent with previous findings demonstrating variability in clinician consensus.5 In contrast, when raters were asked to apply the VA/DoD CPG specifically, kappa scores increased to be in the near perfect range (all >0.90), which was a significant improvement over clinical judgment. These results highlight variability in clinical judgement among raters, which is likely caused by variability in clinical training and/or application of various diagnostic criteria (e.g., VA/DoD CPG, American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine12). This is supported by the increase in reliability following application of standardized criteria (VA/DoD CPG). Accurate and reliable identification of TBI events is imperative in research contexts to provide replicable and generalizable results. The MMA-TBI may be particularly useful when less experienced or non-clinical research staff are administering a protocol, as this instrument is relatively easy to use, and training on the measure was quickly achieved across numerous study staff for the parent study.

Debriefing interviews with raters revealed that Rater 4 applied the updated 2016 VA/DoD CPG11 to make clinical judgement ratings, which include additional neurological soft signs when making a diagnosis. When the algorithm was updated post hoc to reflect the 2016 VA/DoD CPG, the agreement between the algorithm and Rater 4 was perfect. This demonstrates how the MMA-TBI can be updated to reflect changes in diagnostic criteria and that the interview is sufficiently comprehensive and flexible to remain current by adapting to changing clinical criteria. Overall, near perfect kappa scores between raters and the algorithm from both 2009 and 2016 VA/DoD CPG supports the use of operationalized definitions of TBI for consistent diagnostic outcomes when using the MMA-TBI.

The MMA-TBI has several notable strengths. The ability to comprehensively evaluate potential TBI events across the lifespan is an improvement over existing measures that record information about only the most severe events (e.g., BAT-L records the total number of TBIs but only records details from the three most severe incidences; VCU-rCDI only records the worst event; OSU-TBI-ID asks about repeated concussions, but does not document the number). Other interviews also typically gather information that is technically unnecessary to determine if a TBI occurred. For example, the BAT-L and VCU-rCDI gather information about medical care and activity restriction following an event. In contrast, the MMA-TBI is concise and only gathers the information necessary to determine the presence or absence of TBI resulting from an event, making it appealing in both research and clinical contexts. This allows the MMA-TBI to be used in a targeted manner for a specific purpose, giving researchers the option to decide if additional information about events is necessary for the specific project. The interview also offers flexibility and consistency, as the algorithm for TBI was easily and successfully adapted from the 2009 VA/DoD CPG to the 2016 criteria.

The present study included limitations common to all TBI studies. TBI events were recalled retrospectively, introducing the possibility of reporter and memory biases. Collateral information was not available, and details about TBI events could not be validated beyond participant report. Comparison with clinical evaluations suggests the interview was able to elicit information consistent with those evaluations, even though they may have occurred years apart. Additionally, given the exclusion criteria, the interview was validated predominantly against milder injuries; moderate and severe injuries were not fully evaluated in this initial study. Finally, inter-rater reliabilities were calculated on the rating process, not the interview administration, consistent with previous work. The use of retrospective report is consistent with clinical practice, and results were demonstrated to be highly consistent with those obtained clinically.

Conclusion

The present study established the validity and reliability of the MMA-TBI, a new standardized, semistructured instrument for the assessment of TBI across the lifetime using VA/DoD CPG. Results were highly consistent with an independently conducted clinical TBI assessment, the OSU-TBI-ID method, and subject matter experts in TBI. The MMA-TBI represents a focused approach to comprehensively evaluate TBI across the lifespan according to VA/DoD CPG.

Acknowledgments

We thank the veterans and service members who contributed their time and effort to this research. We also thank Mary Peoples, David J. Curry, MSW, Christine Sortino, MS, and Alana M. Higgins, MA, for their contributions to this project.

The views, opinions and/or findings contained in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official Veterans Affairs or Department of Defense position, policy or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation.

APPENDIX 1

Screener:

This initial question is to introduce individuals to the types of events that are most often associated with concussions / brain injuries. It would be the very rare person who has never had exposure to a potentially injurious situation. A positive response to this question is expected for the majority of individuals, but a positive response does not imply the occurrence of a concussion / TBI.

“Most people at some point in their life have experienced events involving a blow to the head or some force acting on their head. I'm going to list several incidents during which this could happen, please say yes if any of them have happened to you: a vehicle accident, an assault or fight, a fall, a recreational or occupational accident, a sports injury involving the head, or a blast or explosion occurring nearby.” YES/NO

A) Loss of consciousness (LOC) should be differentiated from amnesia. During LOC a person is unresponsive and does not exhibit any volitional behaviors (speaking, walking, etc). If a person is exhibiting volitional behaviors but has no recollection of doing so, that should be coded as amnesia below.

“During any of these events, were you ever knocked out, or did you black out, or did you lose consciousness, even for as little as a second?” YES / NO

B) Alteration of consciousness (AOC) should be differentiated from being startled or shocked by a sudden and unexpected event, such as a car accident or assault. AOC should be a clear decrease in the level of consciousness such as a feeling of grogginess, wooziness or tiredness that is difficult to overcome. AOC may also manifest as confusion or disorientation about events or surrounding people. AOC can also be a change in an individual's ability to think clearly or work through problems.

“Sometimes, instead of losing consciousness, people will become dazed, disoriented, or confused. Others may become woozy, groggy, or tired. Have you ever experienced anything like this following one of these events?” YES / NO

C) Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) caused by a brain injury is a disruption in an individual's ability to encode new memories for a certain period of time. The window of amnesia can span prior to and following the event. Amnesia should be differentiated from LOC. During amnesia an individual's level of consciousness may not appear altered to an observer, they can often still perform volitional behaviors (speaking, walking). Often a person is unaware that this has occurred until they are told by someone else.

“Sometimes people have trouble remembering parts of an event. They may have trouble remembering things that happened immediately before or after the event as well. Did this ever happen to you?” “Sometimes people are told they did or said things after an event, yet have no personal memory of doing so, did this ever happen to you?” YES / NO

D) There are many symptoms that can occur immediately following a brain injury. These symptoms should have rapid onset following the injury, and if present before the injury, should increase significantly following the injury. For headaches, this should not be a sore spot or laceration on the scalp where a person was struck by an object, but rather a true headache.

“Please indicate if you have experienced any of the following symptoms after an event: nausea or vomiting, becoming dizzy, balance problems, a headache, difficulty performing normal activities or communicating properly, difficulty with vision or hearing. Sometimes people don't know they are acting differently, but someone else tells them. Have you ever experienced anything like this following one of these events?” YES / NO

If the participant answered ‘YES’ to A, B, C, or D complete questions #1–7 for each event. If the participant answered ‘NO’ to A, B, C, and D the interview is complete.

Individual Events:

This section begins by obtaining an estimate of the total number of lifetime injuries. It may be necessary to remind the individual that both a force acting on the head AND one of the symptom clusters noted above should be present in order to count an event for this question. Some people may have trouble estimating, and it is fine for a person to guess at this point. The purpose of this question is so the interviewer has a general idea of how many events will need to be evaluated. If a large number of events are reported (>10) you should query if several took place in a specified period of time. For example, a boxer or football player who is concussed several times in a season. If this is the case, you can use the multiple exposure rating item and only record data for the most severe injury during that time period.

“Okay, I'd like to ask some questions about times when (event(s) involving LOC, AOC, PTA, post-concussive syndrome [PCS]) happened. First, about how many times in your life do you think you have experienced these kinds of symptoms following some kind of force acting on your head?” ____

Start with the most recent event and work backwards in time until all events are recorded:

“I'm going to ask you several questions about the event(s). [Let's start with the most recent event,] when did that happen?”

Use the Individual Event form from this point forward.

APPENDIX 2

Individual Events:

Complete the following questions for each event:

1. Date of the event: ___/___/___

2. Obtain a description of the event: Have the participant provide a brief description of the event. Try to elicit as much detail as possible on the possible effects on brain functioning (LOC, AOC, PTA, PCS). “Briefly tell me what happened?” “How did you feel afterwards?” “How did that affect you?” “Were you okay?” “Did anyone see what happened, what did they tell you?” “How long did that last?” “Did you feel normal afterwards?” _____________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Answer the following questions based on the individual's description. Ask follow-up or clarifications only as necessary.

a) Type of exposure(s) (circle all that apply): blunt force/blast/acceleration-deceleration/penetrating/ Other:____________________

b) Did it happen during deployment? YES / NO

c) Did it happen while active duty military? YES / NO

3. Loss of consciousness, LOC: LOC should be differentiated from amnesia. During LOC a person is unresponsive and does not exhibit any volitional behaviors (speaking, walking). If a person is exhibiting volitional behaviors but has no recollection of doing so, that should be coded as amnesia below.

Use words from the participant's description: “After (event), did you lose consciousness, black out, or were you knocked out?” YES / NO

“How long were you unconscious?” ____ minutes

4. Alteration of consciousness (AOC): AOC should be differentiated from being startled or shocked by a sudden and unexpected event, such as a car accident or assault. AOC should be a clear decrease in the level of consciousness such as a feeling of grogginess, wooziness, or tiredness that is difficult to overcome, it may feel like they are about to pass out. AOC may also manifest as confusion or disorientation about events or surrounding people. Including not being sure where you are, who is around you, or not being properly oriented [person/place/time]. AOC can also be a change in an individual's ability to think clearly or work through problems.

Use words from the participant's description:

“After (event) did you feel dazed, disoriented, or confused, or feel you were unable to think normally or clearly?” YES / NO

“Did you become groggy or very tired immediately after (event), or feel that you might pass out?” YES / NO

“Was anything odd about your behavior immediately following (event)?” “Did anyone tell you your behavior was odd or different immediately following (event)?” YES / NO

“How long did you feel that way?”___ minutes

5. Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA): Amnesia caused by a brain injury is a disruption in an individual's ability to encode new memories for a certain period of time. The window of amnesia can span prior to and following the event. Amnesia should be differentiated from LOC. During amnesia an individual's level of consciousness may not appear altered to an observer, they can often still perform volitional behaviors (speaking, walking).

“Sometimes people have trouble remembering an event. Sometimes they have trouble remembering things that happened immediately before or after the event as well. This is different than being knocked out, you would still be able to move or speak, but you would not actually remember the things you did.” YES / NO

Sometime people are told about things they did or said immediately following an event, but don't remember doing or saying. Did this happen to you following (event)?” YES / NO

“How long did that last?”______ minutes

6. Post-concussive Symptoms: There are many symptoms that can occur immediately following a brain injury. These symptoms should have rapid onset following the injury, and if present before the injury, should increase significantly following the injury. The duration of symptoms can be as little as a few seconds or last for days. The purpose is to determine if the event disrupted brain functioning in any way.

| “Immediately following (event) did you”: | Duration | |

| a) experience nausea or vomiting? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| b) have a headache? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| c) feel dizzy, have difficulty standing, or have balance problems? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| d) have difficulty hearing or understanding what others were saying? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| e) have problems with your vision (blurry vision, double vision, tunnel vision)? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| f) see stars? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| g) have difficulty speaking clearly or did others have difficulty understanding you? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| h) have difficulty performing normal movements or behaviors? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| i) have increased sensitivity to bright lights or loud noises? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| j) Check here if no postconcussive symptoms ____ |

7. Multiple Exposures: Is this a multiple exposure rating? YES / NO

Notes: _____________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________

-

i)

Starting date: ___ /___ /___

-

i

i) Ending date: ___ /___ /___

-

i

ii) “How many events do you estimate occurred during this time period?” _____

-

i

v) “How many events involved exposure to blasts?” _____

-

v)

“How many events involved exposure to blasts only?”

(no blunt force or acceleration/deceleration) _____

-

v

i) Estimate how many involved AOC for longer than 24 h:_____

-

v

ii) Estimate how many involved PTA for longer than 24 h:_____

| “Immediately following (event) did you”: | Duration | |

| a) experience nausea or vomiting? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| b) have a headache? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| c) feel dizzy, have difficulty standing, or have balance problems? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| d) have difficulty hearing or understanding what others were saying? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| e) have problems with your vision (blurry vision, double vision, tunnel vision)? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| f) see stars? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| g) have difficulty speaking clearly or did others have difficulty understanding you? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| h) have difficulty performing normal movements or behaviors? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| i) have increased sensitivity to bright lights or loud noises? | YES / NO | _______ h/min/sec |

| j) Check here if no postconcussive symptoms ____ |

Funding Information

This work was supported by grant funding from Department of Defense, Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC) Award W81XWH-13-2-0095 and Department of Veterans Affairs CENC Award I01 CX001135. This research was also supported by the Salisbury VA Medical Center, Mid-Atlantic (VISN 6) Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) and the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Program in Mental Illness, Research, and Treatment.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Davenport, N.D. (2016). The chaos of combat: an overview of challenges in military mild traumatic brain injury research. Front. Psychiatry 7, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (2019). Evaluation of the Disability Determination Process for Traumatic Brain Injury in Veterans. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mueller, A.E., and Segal, D.L. (2015). Structured versus semistructured versus unstructured interviews, in: The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. R.L. Cautin and S.O. Lilienfeld (eds.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom; Malden, MA, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corrigan, J.D., and Bogner, J. (2007). Initial reliability and validity of the Ohio State University TBI Identification Method. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 22, 318–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker, W.C., Cifu, D.X., Hudak, A.M., Goldberg, G., Kunz, R.D., and Sima, A.P. (2015). Structured interview for mild traumatic brain injury after military blast: inter-rater agreement and development of diagnostic algorithm. J. Neurotrauma 32, 464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donnelly, K.T., Donnelly, J.P., Dunnam, M., Warner, G.C., Kittleson, C.J., Constance, J.E., Bradshaw, C.B., and Alt, M. (2011). Reliability, sensitivity, and specificity of the VA traumatic brain injury screening tool. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 26, 439–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanderploeg, R.D., Groer, S., and Belanger, H.G. (2012). Initial developmental process of a VA semistructured clinical interview for TBI identification. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 49, 545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fortier, C.B., Amick, M.M., Grande, L., McGlynn, S., Kenna, A., Morra, L., Clark, A., Milberg, W.P., and McGlinchey, R.E. (2014). The Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) semistructured interview: evidence of research utility and validity. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 29, 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group (2009). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI). J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 46, CP1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vogt, D., Smith, B.N., King, L.A., King, D.W., Knight, J., and Vasterling, J.J. (2013). Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory-2 (DRRI-2): an updated tool for assessing psychosocial risk and resilience factors among service members and veterans. J Trauma Stress 26, 710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group (2016). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/mTBI. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi (Last accessed April 22, 2020).

- 12. Kay, T., Harrington, D.E., Adams, R., Anderson, T., Berrol, S., Cicerone, K., Dahlberg, C., Gerber, D., Goka, R., Harley, P., hilt, J., Horn, J., Horn, L., Lehmkuhl, D., and Malec, J. (1993). Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 8, 74–85. [Google Scholar]