Abstract

Cryptosporidium parvum preferentially infects epithelial cells lining the intestinal mucosa of mammalian hosts. Parasite development and propagation occurs within a unique intracellular but extracytoplasmic parasitophorous vacuole at the apical surface of infected cells. Parasite-induced host cell signaling events and subsequent cytoskeletal remodeling were investigated by using cultured bovine fallopian tube epithelial (BFTE) cells inoculated with C. parvum sporozoites. Indirect-immunofluorescence microscopy detected host tyrosine phosphorylation within 30 s of inoculation. At >30 min postinoculation, actin aggregates were detected at the site of parasite attachment by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin staining as well as by indirect immunolabeling with monoclonal anti-actin. The actin-binding protein villin was also detected in focal aggregates at the site of attachment. Host cytoskeletal rearrangement persisted for the duration of the parasitophorous vacuole and contributed to the formation of long, branched microvilli clustered around the cryptosporidial vacuole. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin significantly inhibited (P < 0.05) C. parvum infection when BFTE cells were pretreated for 60 min at 37°C prior to inoculation. Similarly, treatment of BFTE cells with the protein kinase inhibitors genistein and staurosporine and the cytoskeletally acting compounds 1-(5-iodonaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazapine, cytochalasin D, and 2,3-butanedione monoxime significantly inhibited (P < 0.05) in vitro infection at 24 h postinoculation. These findings demonstrate a prominent role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity during the early C. parvum infection process and suggest that manipulation of host signaling pathways results in actin rearrangement at the site of sporozoite attachment.

Cryptosporidium parvum is a significant opportunistic pathogen in the AIDS patient population. Human infection is characterized by profuse diarrheal illness in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, although the infection is generally self-limited, chronic infection and colonization of the intestinal epithelium is seen in the absence of an appropriate immune response (25, 26). Cryptosporidiosis is acquired from the ingestion of sporulated oocysts, which excyst in the intestinal lumen and release infective sporozoites. The apical surface of epithelial cells lining the small intestine is the preferential site of sporozoite attachment and subsequent infection. Sporozoite attachment results in the formation of a unique intracellular but extracytoplasmic parasitophorous vacuole, and successive developmental intermediates of C. parvum propagate within similarly located vacuoles (25). Parasite numbers are amplified by the repetitive cycling of asexual intermediates (merozoites), which multiply in vacuoles analogous to those formed by sporozoites at the onset of infection. In contrast, other members of the protozoan phylum Apicomplexa typically form an intracytoplasmic parasitophorous vacuole that resides within the host cell cytosol while the parasite undergoes maturation and proliferation.

The early infection dynamics of C. parvum and the factors that regulate the enigmatic residence of the cryptosporidial vacuole are poorly understood. Adherence and invasion by obligate intracellular bacteria induce cytoskeletal rearrangement within the host cell as a prelude to membrane penetration and cytoplasmic intrusion (reviewed in reference 32). Filamentous actin (F-actin) aggregates at the site of bacterial attachment, and in some instances, polymerized actin remains condensed around intracytoplasmic vacuoles, sequestering invading pathogens from host defense mechanisms within infected cells (22). Exploitation of constitutive host cell signaling pathways, in particular the manipulation of protein and phospholipid kinases (17, 27, 29), and subsequent cytoskeletal rearrangement have proven to be successful adaptations by which microbes gain access to their preferred intracellular environments (5, 11, 14, 15).

Morisaki et al. (24) reported the active invasion of mammalian cells by the apicomplexan Toxoplasma gondii, which uses a process independent of cytoskeletal rearrangement or tyrosine kinase activity in the host cell. The polymerization of parasite actin was recently shown to provide the motive force for membrane penetration and intracellular localization of T. gondii (10). Actin-dependent motility has also been assigned a role in Plasmodium spp. invasion (13), as has phosphorylation of host cytoskeletal proteins (6). Despite the apparent phylogenetic relationship of the apicomplexans, the unique microenvironmental niche favored by C. parvum suggests the selective adaptation of alternative pathways that facilitate host cell infection and regulate the retention of the cryptosporidial vacuole at the periphery of the intracellular milieu.

A relationship between sporozoite attachment and subsequent host cell responses, specifically, a role for kinase activity and cytoskeletal remodeling, was investigated in the present study. We report herein the rapid onset of host phospholipid and protein kinase activities following sporozoite attachment. Furthermore, parasite attachment resulted in the focal rearrangement of host cytoskeletal actin at the site of infection and initiation of the parasitophorous vacuole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite propagation and isolation.

Oocysts were maintained by passage in experimentally infected Holstein calves and purified from feces by using discontinuous sucrose and isopycnic Percoll gradients (2). Purified oocysts were stored in potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) at 4°C. Prior to use in cell culture, the oocysts were decontaminated with a 20% (vol/vol) bleach solution (Clorox, 5.25% sodium hypochlorite in stock concentration) for 10 min at 4°C and thoroughly washed with sterile Hanks’ balanced salt solution to remove residual K2Cr2O7 and bleach. Decontaminated oocysts were harvested following centrifugation and resuspended in RPMI 1640 base medium (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah). Sporozoites were prepared from bleach-decontaminated oocysts suspended in RPMI at a concentration of 107 oocysts/ml. The oocyst suspension was aspirated into sterile, prewarmed (37°C for 30 min) syringes and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The resulting mixture of oocysts and sporozoites was passed through a sterile 3-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) under gentle pressure and resuspended in RPMI to a final concentration of 106 sporozoites/ml. Samples of filtered sporozoite suspensions were examined by bright-field microscopy and found to be negative for intact or partially excysted oocysts.

Compounds. (i) Inhibitors of signal transduction.

The nonspecific tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (ICN Biochemicals, Inc., Auroro, Ohio) and the general protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) were initially dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) at stock concentrations of 10 mM. Wortmannin, an irreversible inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K), was initially dissolved in DMSO as a 10 μM stock solution. A 1 mM stock solution of suramin (Sigma), an inhibitor of transmembrane receptor-linked GTPase (G protein) activity, was prepared in RPMI 1640. Stock solutions of these inhibitors were passed through 0.8-μm and 0.2-μm syringe filters (Acrodisc PF; Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, Mich.) and further diluted in RPMI in preparation for evaluation in culture. Working solutions contained <1% (vol/vol) DMSO.

(ii) Inhibitors of cytoskeletal activity.

Cytochalasin D (Sigma), an inhibitor of actin polymerization, was dissolved in DMSO and diluted in RPMI to prepare a 10 mM stock solution. The myosin ATPase inhibitor 2,3-butanedione monoxime (2,3-BDM; Sigma) and the myosin light-chain kinase inhibitor 1-(5-iodonaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-1H-hexhydro-1,4-diazapine (ML-7; Sigma) were initially prepared as 100 mM stock solutions in RPMI. The stock solutions were filter sterilized and further diluted in RPMI as needed.

Preparation of BFTE cell cultures.

A primary culture of bovine fallopian tube epithelial (BFTE) cells was prepared by the method of Yang et al. (36). Briefly, epithelial cells were flushed from the luminal surface of bovine fallopian tubes (E. A. Miller & Sons Packing Co., Hyrum, Utah) with sterile Hanks’ balanced salt solution. The cells were thoroughly washed, concentrated by centrifugation, and grown in 25-cm2 culture flasks containing RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone). Confluent monolayers were trypsinized and seeded onto round glass coverslips in individual wells of 24-well culture plates (Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.) with RPMI without supplementation. The culture plates were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 until confluent monolayers were evident on the coverslips.

Infectivity studies.

To evaluate the effect of the selected compounds on infectivity, 1.0-ml volumes of individual compound dilutions were added to BFTE cell monolayers and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Control groups consisted of cells incubated with an equal volume of RPMI (solvent matched with 1% DMSO when appropriate). Following treatment, the monolayers were rinsed three times with RPMI and inoculated with 250 μl of RPMI containing 106 sporozoites/ml. Inoculated cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Parasite enumeration and data analysis.

BFTE cell monolayers were collected at 24 h postinoculation, rinsed with RPMI to remove residual inoculum, and fixed in absolute methanol at room temperature (25°C). Fixed cells were stained with Giemsa, mounted (inverted) on glass slides with a permanent mounting medium, and examined by bright-field microscopy (oil immersion objective, ×100; total magnification, ×1,000). Parasites were counted under light microscopy as described by Yang et al. (36) in a process involving counting the number of parasites present in a single scan across the diameter of each coverslip. The mean number of parasites counted in each of the treatment groups was expressed as a percentage of the mean number of parasites counted in an infection control group. The difference between the mean values for the treatment and control groups was compared for statistical significance by analysis of variance (Fisher’s protected least significant difference).

Fluorescence microscopy.

BFTE cell monolayers, inoculated with C. parvum sporozoites, were incubated in a 37°C water bath. The cells were sequentially sampled at 30-s intervals for 5 min and further sampled at 5-min intervals for 60 min. Immediately after removal from the water bath, the coverslips were immersed in absolute methanol at room temperature for 10 min to fix the cell monolayers, washed twice with 25 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100–PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The coverslips were washed with PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBST), blocked with 2% normal goat serum (NGS)–PBST, and incubated with mouse monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine (1:500; Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were washed with PBST and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary ligand (1:500; Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were washed thoroughly with PBST and counterstained with Hoescht 33342 (Sigma) at room temperature for 10 min (light protected) to visualize host cell and parasite DNA. The coverslips were mounted (inverted) on glass slides with a 1:1 solution of glycerol-PBS and examined by epifluorescence microscopy.

Cytoskeletal rearrangement was visualized in fixed and permeabilized cells by direct staining with a 1-μg/ml solution of FITC-conjugated phalloidin for 30 min at room temperature. Following staining, the coverslips were washed with PBST, counterstained with Hoescht 33342, mounted on glass slides, and examined by epifluorescence microscopy. Alternatively, cells were labeled for actin or villin by using an indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). Cell monolayers were blocked with 5% NGS–PBST and exposed sequentially to either rabbit anti-actin (1:400; Sigma) or mouse anti-villin (1:100; Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.) and an appropriate anti-species FITC-conjugated secondary ligand (Sigma). The coverslips were counterstained with Hoescht 33342 and mounted and examined as described above. A similar series of experiments was conducted with bleach-decontaminated oocysts (105 in RPMI) as the cell inoculum in place of filter-isolated sporozoites. The alternative inoculum was used to assess the onset of host actin polymerization when sporozoites were excysted directly in culture, thus minimizing the deleterious effects of handling on sporozoite viability.

A final group of sporozoite-inoculated cells was maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 12 h, washed with RPMI 1640 base medium to remove residual inoculum, and sampled at 12-h intervals for 96 h. These conditions were selected to evaluate host actin polymerization over the course of asexual development of the parasite. Samples from extended incubation intervals were handled in a fashion identical to that described above for visualizing F-actin rearrangement.

Electron microscopy. (i) Transmission electron microscopy.

Neonatal Swiss Webster mice were inoculated with 107 C. parvum oocysts and killed 2 to 6 days postinoculation. Pieces of the small intestine were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in Millong’s phosphate buffer, postfixed in 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide (OsO4), dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Spurr’s epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined under a JEOL 1000CX electron microscope.

(ii) SEM.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of parasitophorous vacuoles was performed as described by Yang et al. (36). In brief, BFTE cell monolayers were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde–0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4) and incubated in 2% tannic acid–2% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 25°C. The cell monolayers were washed overnight in PB and sequentially postfixed in 2% OsO4, 1% tricarbohydrazide, and 1% OsO4. The cells were then dehydrated in ethanol, dried in a critical-point drying apparatus, and sputter coated with gold-palladium. Prepared samples were viewed under a Hitachi S-400 field emission microscope.

RESULTS

PO-Y signal induced by sporozoite attachment.

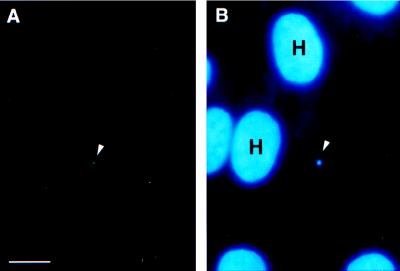

Tyrosine phosphorylation was detected in BFTE cells sampled at ≥30 s postinoculation. Indirect IFA revealed a dense fluorescent label in specific association with the site of sporozoite attachment. Hoescht 33342-stained DNA confirmed the presence of the parasite nucleus in immediate proximity to the immunolabeled phosphotyrosine (PO-Y) signal (Fig. 1). Immunolabeling of PO-Y residues was only observed in inoculated cell monolayers; negative controls, i.e., lacking inoculum, did not exhibit PO-Y labeling. Further, IFA rarely detected PO-Y in cells sampled ≥30 min postinoculation, even though Hoescht 33342 counterstaining confirmed the presence of sporozoite nuclei in the cell monolayers.

FIG. 1.

Indirect immunofluorescent labeling of PO-Y in BFTE cells inoculated with C. parvum sporozoites. At 30 s postinoculation, PO-Y signal (A) was demonstrated by an FITC label (arrowhead). The Hoescht 33342 counterstain (B) indicated the presence of attached sporozoite nuclei (arrow) and host cell DNA. H, host cell nuclei. Bar, 5 μm.

Host cytoskeletal remodeling associated with parasite attachment and infection.

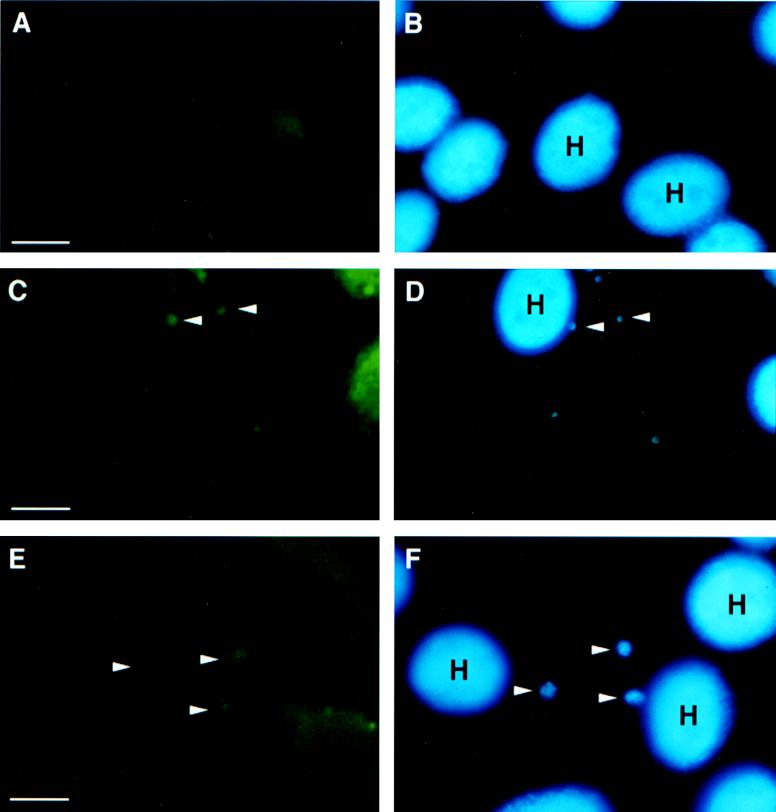

Fluorescence microscopy demonstrated the presence of polymerized actin at the site of sporozoite attachment at ≥30 min postinoculation. FITC-conjugated phalloidin staining showed a dense pattern of fluorescence around the site of parasite attachment. Hoescht 33342 counterstaining confirmed the presence of the parasite nucleus in immediate association with the phalloidin-stained actin microfilaments (Fig. 2). Indirect IFA confirmed the presence of actin aggregates at the site of parasite attachment. As shown in Fig. 3, monoclonal anti-actin antibody was labeled at the site of sporozoite attachment. When cell monolayers were inoculated with oocysts, actin polymerization was detected at 5 min postinoculation, at the point of sporozoite emergence from the oocyst wall (Fig. 3C and D). In contrast to the findings described for PO-Y, fluorescent labeling of actin aggregates was a persistent finding for the duration of the parasitophorous vacuole and was detected in all samples assayed from 12 to 96 h postinoculation range (Fig. 3E). The actin-binding protein, villin, was also detected in aggregates at the site of sporozoite attachment and, subsequently, in immediate proximity to the parasitophorous vacuole (Fig. 3F). Consistent with the detection of polymerized actin, immunolabeling revealed a focal concentration of villin throughout the duration of the parasitophorous vacuole. Controls, consisting of intact oocysts and isolated sporozoites, were phalloidin insensitive and negative for PO-Y and villin by IFA. Monoclonal anti-actin IFA showed a faint, diffuse pattern of fluorescence (data not shown) in sporozoites and an absence of labeling associated with the oocyst wall.

FIG. 2.

FITC-conjugated phalloidin staining of sporozoite-inoculated BFTE cells at 60 min postinoculation. (A) Uninoculated control cells. (B) Hoescht 33342 counterstain, indicating the location of host cell nuclei. (C) Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin aggregates (arrowheads) in inoculated cell monolayer associated with developing parasites. (D) Hoescht 33342-stained DNA indicating the presence of parasite DNA within parasitophorous vacuoles (arrows). (E) FITC-phalloidin-stained monolayers demonstrating F-actin aggregations (arrowheads) around the parasitophorous vacuole at 72 h postinoculation. (F) Hoescht 33342 stain, indicating the DNA of the host cell and developing meronts (arrowheads). H, host cell nuclei. Bars, 5 μm.

FIG. 3.

Indirect immunofluorescent labeling of actin in oocyst-inoculated BFTE cells. (A) Uninoculated control cells showing the typical actin microfilament network detected following immunofluorescent labeling with monoclonal anti-actin. (B) Hoescht 33342 counterstaining of the same field indicating the presence of host cell nuclear DNA. (C) Dense fluorescent label of actin aggregates at the site of a sporozoite emerging from an oocyst (arrowhead). (D) Position of an emerging sporozoite as indicated (arrowhead) by Hoescht 33342 counterstaining, as is the presence of residual sporozoites within the oocyst wall. (E) Immunolabeling of cytoskeletal proteins in BFTE cells 72 h postinoculation, demonstrating a dense fluorescent actin label associated with two meronts and a petechial pattern of smaller actin aggregates surrounding the parasites. (F) Immunolabeling of the actin cross-linking protein villin showing focal concentrations around three parasitophorous vacuoles 48 h postinoculation. Smaller aggregates of villin were observed to radiate from the periphery of the parasitophorous vacuole H, host cell nuclei. Bar, 5 μm.

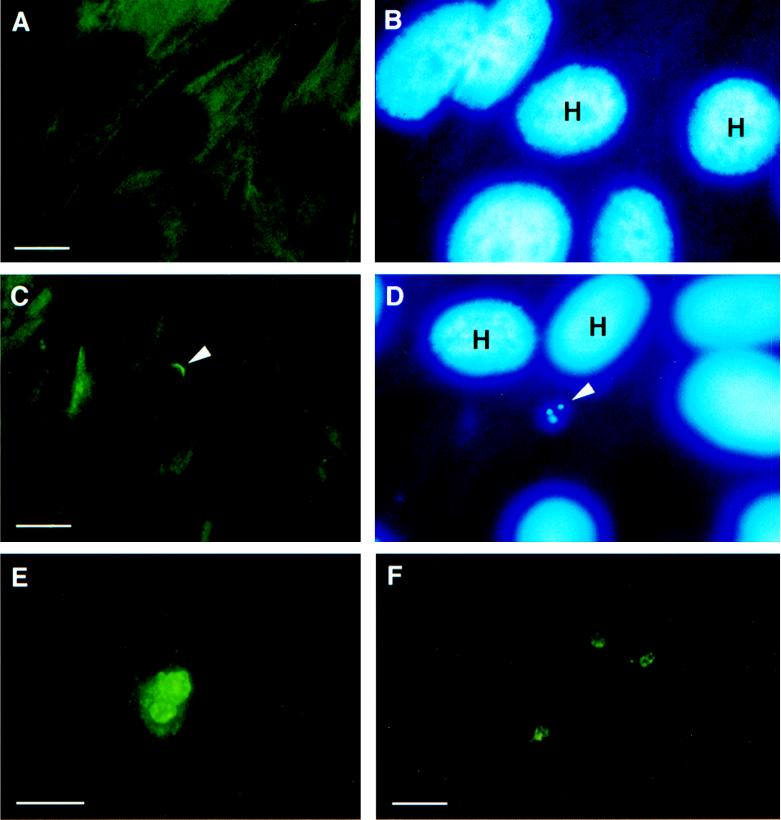

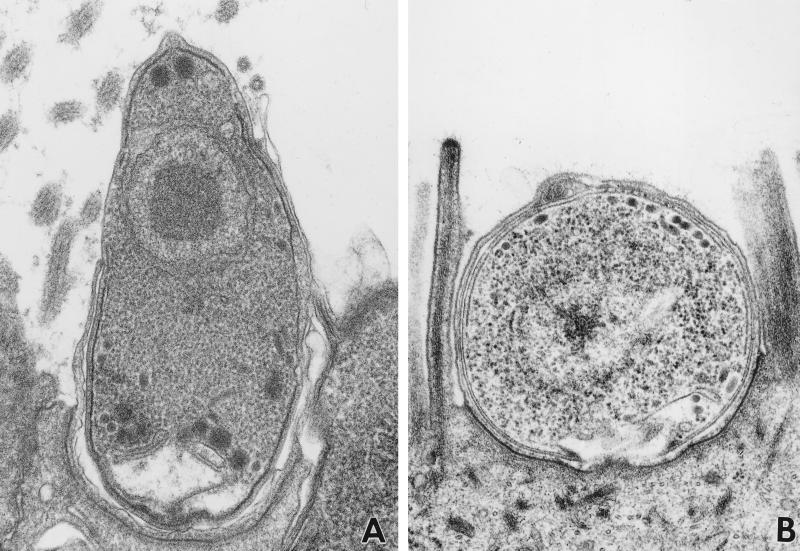

Electron microscopy.

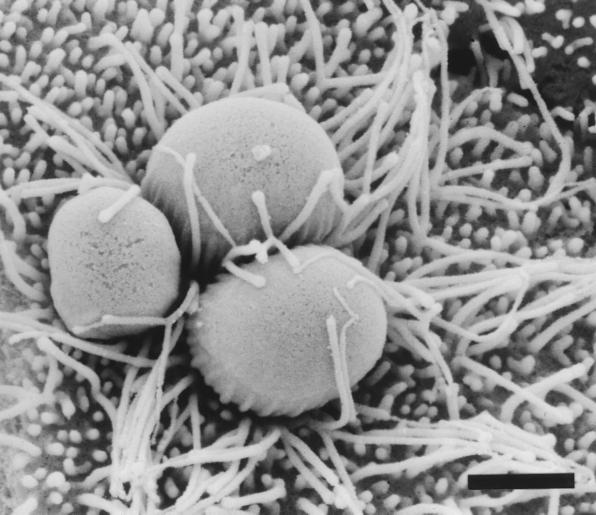

Cytoskeletal remodeling was evident at the ultrastructural level by the presence of microvillous hypertrophy. Elongation and protrusion of host cell microvilli was observed at the site of merozoite attachment during asexual amplification (Fig. 4). Membrane protrusions were observed to extend closely along the body of the attached parasites, suggesting contact association during elongation, invagination of the membrane surface displaced by the attached merozoite, or a combination of microvillous extension and surface invagination in the process of early infection. Following the initial formation of the parasitophorous vacuole, microvilli continued to cluster in long, branched forms around the developing trophozoite stage of the parasite. The microvilli associated with the parasitophorous vacuole were noted to be particularly thick and contained dense bundles of actin filaments with prominent rootlets visible in the terminal web. This persistent hypertrophy was also observed by SEM as long, branched microvilli in the periphery of developing meronts throughout the course of asexual propagation (Fig. 5). The distinct fluted appearance of the membrane surrounding developing meronts, as previously described by Yang et al. (36), is clearly visible.

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron micrograph of C. parvum in mouse ileum 4 days postinfection. (A) Merozoite attached to an epithelial cell. Host membrane extrusion and flow is evident around the attached merozoite, covering approximately 90 and 60% of the merozoite body on the right and left sides, respectively. (B) Trophozoite stage of C. parvum. This is seen as a large, uninuclear form within a parasitophorous vacuole. Long, thick microvilli are evident along both sides of the vacuole.

FIG. 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of parasitophorous vacuoles in BFTE cells 72 h postinoculation. The appearance of long, branched microvilli indicates persistent microvillous hypertrophy around three asexual intermediates of C. parvum. Bar, 1.5 μm.

In vitro inhibitor studies. (i) Kinase/G-protein inhibitors.

BFTE cells were permissive to C. parvum infection and showed numerous asexual intermediate forms at 24 h postinoculation in the infection control group. A similar pattern of infection and development was observed in solvent-matched control groups (1% DMSO). Although the 24-h postinoculation rates in DMSO control groups were slightly reduced, the difference was not statistically significant. Parasite numbers were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in the presence of the PTK inhibitors genistein and staurosporine in a concentration-dependent manner (Table 1). The PI3K inhibitor wortmannin also significantly reduced (P < 0.05) parasite numbers, achieving a significant inhibitory effect at nanomolar levels. Sporozoite attachment, in the absence of further infection or development, was observed in samples pretreated with kinase inhibitors. The G-protein-uncoupling agent suramin did not show a significant inhibitory effect on in vitro infection at 24 h postinoculation relative to mean control values. BFTE cells were particularly sensitive to suramin, and toxicity was apparent at concentrations of >20 μM; toxicity was noted as loss of adherent monolayers with lysis and peeling of cells in the center portions of coverslips.

TABLE 1.

Effect of cell signaling inhibitors on C. parvum infection in cultured BFTE cells

| Compound | Concn | % Infectiona |

|---|---|---|

| PI3K inhibitors | ||

| Infection control (RPMI) | 100b | |

| DMSO-matched control | 1% (vol/vol) | 83 ± 12 |

| Wortmannin | 1 nM | 32 ± 9c |

| 10 nM | 23 ± 6c | |

| 100 nM | 19 ± 9c | |

| PTK | ||

| DMSO control | 1% (vol/vol) | 88 ± 10 |

| Genistein | 2.5 μM | 64 ± 86 |

| 25 μM | 50 ± 10c | |

| 250 μM | 44 ± 7c | |

| Staurosporine | 2.5 μM | 70 ± 11 |

| 5 μM | 45 ± 9c | |

| 25 μM | 38 ± 8c | |

| G-protein-blocking compound | ||

| Suramin | 10 μM | 72 ± 8 |

| 100 μM | 65 ± 9 |

Infection is expressed as a percentage of the solvent-matched control group mean. Values are means ± standard deviations (duplicate samples in three separate experiments).

Infection control (RPMI 1640 base medium only) is assigned a value of 100%. The parasite count (mean ± standard deviation) for the RPMI control samples was 224 ± 28.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from solvent-matched infection control group mean value.

(ii) Cytoskeletally acting compounds.

Treatment groups exposed to cytochalasin D had significantly fewer (P < 0.05) parasites at 24 h postinoculation than did solvent-matched control samples. Inhibition was concentration dependent and was evident at cytochalasin D levels of ≥0.1 μM (Table 2). The myosin light-chain kinase inhibitor ML-7 and the myosin ATPase inhibitor 2,3-BDM both exhibited a significant inhibitory (P < 0.05) effect on infectivity at concentrations ≥10 mM. Sporozoite attachment was not visibly inhibited by these compounds.

TABLE 2.

Effect of cytoskeletal-acting compounds on C. parvum infection in cultured BFTE cells

| Compound | Concn | % Infectiona |

|---|---|---|

| Infection control (RPMI) | 100b | |

| DMSO control | 1% (vol/vol) | 81 ± 12 |

| Cytochalasin D | 0.1 μM | 48 ± 9c |

| 1 μM | 45 ± 11c | |

| 10 μM | 32 ± 8c | |

| 25 μM | 25 ± 7c | |

| ML-7 | 5 mM | 67 ± 9 |

| 10 mM | 42 ± 14c | |

| 20 mM | 46 ± 8c | |

| 2,3-BDM | 5 mM | 78 ± 14 |

| 10 mM | 56 ± 8c | |

| 20 mM | 39 ± 6c |

Infection is expressed as a percentage of the solvent-matched control group mean. Values are means ± standard deviations (duplicate samples in three separate experiments).

Infection control (RPMI 1640 base medium only) is assigned a value of 100%. The parasite count (mean ± standard deviation) for the RPMI control samples was 224 ± 28.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from solvent-matched infection control group mean value.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides substantive evidence for the involvement of host signal transduction events following sporozoite attachment, in particular, protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) and PI3K activity. Further, host cell actin and the actin-binding protein villin aggregated at the site of parasite adhesion and contributed to the initial formation of the parasitophorous vacuole. While kinase activity was observed to be rapidly induced by sporozoite attachment, cytoskeletal remodeling occurred after PI3K activity and persisted for the duration of the parasitophorous vacuole. The suppression of host cell responses by select inhibitors of PTK, PI3K, actin polymerization, and myosin light-chain function had a significant impact on infectivity and suggested a role for signal transduction events in the early parasite-host cell dynamics of C. parvum.

An understanding of the early infection process of C. parvum has been confounded, at least in part, by the enigmatic residence of the parasite within an intramembranous vacuole. Unlike phylogenetic counterparts, C. parvum sporozoites do not actively penetrate host cell membranes and successive intermediate stages develop within the extracytoplasmic domain of the parasitophorous vacuole. Our findings demonstrate that phospholipid-mediated signal pathways play a role in the early infection process of C. parvum. Sporozoite attachment was not blocked by kinase inhibitors or cytoskeletally acting compounds, suggesting that attachment is a prefatory event to host cell responses. These data suggest that at least one downstream effect of attachment-induced PI3K activity is the rearrangement of the cortical actin component of the host cytoskeleton, a critical step in the infection process. Evidence for PI3K involvement during infection is supported by the in vitro inhibitory effects of wortmannin, an irreversible inhibitor of PI3K (18, 31, 35). The involvement of PI3K in C. parvum infection supports a postulated role for phospholipid signaling in regulating the postattachment effects that, collectively, manipulate the intracellular microenvironment of the targeted host cell to accommodate the infecting pathogen.

The manipulation of host cell cultures by repeated washing prior to inoculation was intended to remove residual inhibitors following treatment. It is possible that small quantities of inhibitors remained in the microenvironment to which the sporozoite inoculum was added. The effect of even extremely low levels of kinase inhibitors on C. parvum sporozoites is unknown, and we cannot fully exclude the effect of residual inhibitors on sporozoites.

The short time interval between culture inoculation and the detection of PO-Y signaling strengthens the hypothesis that events in the early infection process proceed quickly following sporozoite attachment. The presence of actin aggregates, in apparent association with the actin-binding protein villin, in the immediate vicinity of adherent sporozoites substantiates previous reports of microvillous hypertrophy during infection (21, 36, 37). One remarkable finding of the present study was the rapid appearance of actin aggregates in the process of sporozoites emerging from oocysts applied directly to BFTE cells (Fig. 3). This particular observation, that interactions occur from the very earliest contact between parasites and host cells, strongly suggests that sporozoites initiate the process of infection immediately after exiting the oocyst.

The involvement of villin, a unique cross-linking protein that stabilizes F-actin bundles in microvilli, strengthens the association of microvillous extrusion during early infection. The persistence of long, protruding microvilli clustered at the site of initial attachment and the subsequent development of the parasitophorous vacuole suggest active manipulation of host membrane structure by the developing parasite. The inhibitory effects of ML-7 and 2,3-BDM offer strong initial evidence that myosin motor activity, putatively in association with microvilli extension, is involved in the formation of the parasitophorous vacuole around the attached C. parvum sporozoite. A model proposed by Mitchison and Cramer (23) for protrusion of membranous structures illustrates the prominent involvement of myosin proteins in the movement of actin filaments toward the apical surface of membranous extensions.

PI3K activity has been implicated in an array of cellular processes including survival (1, 7), membrane ruffling (9, 34), production of phospholipid second messengers (8, 31), protein and membrane trafficking (8), linkage to mitogen-activated protein kinase activation (20), fusion of endocytic vacuoles (3), response to stress (12), and dynamic rearrangement of F-actin (17–18, 33). Phosphoinositide-mediated actin polymerization accounts for the rapid rearrangement of cytoplasmic actin in activated platelets (14, 16, 28). Short fragments of F-actin are capped at their barbed (growing) end in the resting state. Uncapping leads to dynamic growth and polymerization of elongated F-actin microfilaments. Phosphatidylinositol(4)P, phosphatidylinositol(4,5)P2, and phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)P3 mediate the aggregation of F-actin by facilitating the uncapping process (28) and are activated by ligand binding to transmembrane integrin receptors (4, 30). Cytoskeletal rearrangement following C. parvum sporozoite attachment may reflect the downstream effect of PI3K activity, specifically the involvement of phospholipid signaling in the uncapping of F-actin fragments.

The present study demonstrated that PI3K activity is necessary for sporozoite infection. Furthermore, we have shown that PI3K activity is apparently modulated by a non-G-protein-dependent pathway, evidenced by the lack of an inhibitory response following treatment of BFTE cells with suramin. These data suggest that the parasite-induced responses we observed may be linked to the activation of PI3K activity via tyrosine kinase growth factor receptors. Since PI3Ks can be activated by G-protein transmembrane receptors or by tyrosine growth factor receptors, this is a significant finding. A specific signal transduction pathway appears to be activated following sporozoite attachment and suggests a direction for future study. The effects observed when host cells were treated with wortmannin are consistent with this interpretation.

The persistence of polymerized actin at the site of infection may serve to anchor the parasitophorous vacuole and contribute to the retention of the vacuole within the host cell membrane by antagonizing further endocytotic movement. One potential explanation for cytoskeletal rearrangement is that this restructuring provides a network for vesicle trafficking that facilitates the movement of nutrients and other essential factors between the host cell and the parasitophorous vacuole. Emerging paradigms for membrane trafficking between intracellular parasites and their hosts will be of particular interest in future studies of vesicle movement in parasitized cells (19). It is unlikely that cytoskeletal involvement during C. parvum infection is limited to focal rearrangement of actin and villin. The remarkable alteration of membrane structure and distribution of intramembranous particles reported by other investigators supports the notion that cytoskeletal remodeling during cryptosporidial infection involves additional structural and associative proteins at the site of infection (21, 37).

The findings of the present study illustrate a critical aspect of C. parvum infection and suggest a preliminary model of the early infection process. Confining the present focus to demonstrable host cell responses following attachment enabled a prefatory description of host signaling events during infection. We acknowledge that parasite signaling and cytoskeletal reorganization are likely to be involved in establishing infection. As reported for the protozoan parasite Theileria parva, signal transduction processes within both host lymphocytes and sporozoites were required for infection (29). Studies of the role of cryptosporidial kinases and cytoskeletal rearrangement within the parasite are needed to more fully define the integration of parasite-host cell biology that regulate the maturation, development, and proliferative processes of successful infection.

Fundamental differences in the localization of the parasitophorous vacuoles and the relatively restrictive host cell ranges of C. parvum compared with other apicomplexans prompted our hypothesis that infection, particularly in the absence of membrane penetration, involves the manipulation of host cell pathways to accommodate the cryptosporidial sporozoite. Stimulation of host PI3K activity following attachment of C. parvum sporozoites facilitates infection in the absence of membrane penetration and intracytoplasmic invasion. The interactions detected between C. parvum sporozoites and permissive host cells appear to be directed toward evoking responses that contribute to the structural integrity of the developing parasitophorous vacuole. The exploitation of host signal pathways following attachment is evidence of successful adaptation by the parasite to a highly refined host cell niche and suggests a prominent role for host PI3K activity and F-actin remodeling in the cell biology of C. parvum infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Chunwei Du and Kehe Huang. Appreciation is further extended to Harley Moon (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Ames, Iowa) for donating the original strain of oocysts used in this study.

This research was supported, in part, by the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Journal paper no. 7060 of the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson P. Kinase cascades regulating entry into apoptosis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:33–46. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.33-46.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrowood M J, Sterling C R. Isolation of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites using discontinuous sucrose and isopycnic Percoll gradients. J Parasitol. 1987;73:314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araki N, Johnson M T, Swanson J A. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the completion of macropinocytosis and phagocytosis by macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1249–1260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banfic H, Tang X, Batty I H, Downes C P, Chen C, Rittenhouse S E. A novel integrin-activated pathway forms PKB/Akt-stimulatory phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate via phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in platelets. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beverley S M. Hijacking the cell: parasites in the driver’s seat. Cell. 1996;87:787–789. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81984-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chishti A H, Maalouf G J, Marfatia S, Palek J, Wang W, Fisher D, Liu S C. Phosphorylation of protein 4.1 in Plasmodium falciparum-infected human red blood cells. Blood. 1994;83:3339–3345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta S R, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg M E. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Camilli P, Emr S D, McPerson P S, Novick P. Phosphoinositides as regulators in membrane traffic. Science. 1996;271:1533–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharmawardhane S, Sanders L C, Martin S S, Daniels R H, Bokoch G M. Localization of p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) to pinocytic vesicles and cortical actin structures in stimulated cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1265–1278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobrowolski J M, Sibley L D. Toxoplasma invasion of mammalian cells is powered by the actin cytoskeleton of the parasite. Cell. 1996;84:933–939. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donelli G, Fabri A, Fiorentini C. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces cytoskeletal changes and surface blebbing in HT-29 cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:113–119. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.113-119.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dove S K, Cooke F T, Douglas M R, Sayers L G, Parker P J, Michell R H. Osmotic stress activates phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate synthesis. Nature. 1997;390:187–192. doi: 10.1038/36613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field S J, Pinder J C, Clough B, Dluzewski A R, Wilson R J M, Gratzer W B. Actin in the merozoite of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1993;25:43–48. doi: 10.1002/cm.970250106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukami K, Endo T, Imamura M. α-Actinin and vinculin are PIP2-binding proteins involved in signaling by tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1518–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grassmé H U C, Ireland R M, Van Putten J P M. Gonococcal opacity protein promotes bacterial entry-associated rearrangements of the epithelial cell actin cytoskeleton. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1621–1630. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1621-1630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartwig J H, Bokoch G M, Carpenter C L, Janmey P A, Taylor L A, Toker A, Stossel T P. Thrombin receptor ligation and activated Rac uncap actin filament barbed ends through phosphoinositide synthesis in permeabilized human platelets. Cell. 1995;82:643–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinzen R A, Hayes S F, Peacock M G, Hackstadt T. Directional actin polymerization associated with spotted fever group Rickettsia infection of Vero cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1926–1935. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1926-1935.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ireton K, Payrastre B, Chap H, Ogawa W, Sakaue H, Kasuga M, Cassart P. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in bacterial invasion. Science. 1996;274:780–782. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauer S A, Rathod P K, Ghori N, Haldar K. A membrane network for nutrient import in red cells infected with the malaria parasite. Science. 1997;276:1122–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez-Ilasaca M, Cresop P, Pellici P F, Gutkind J S, Wetzker R. Linkage of G protein-coupled receptors to the MAPK signaling pathway through PI 3-kinase γ. Science. 1997;275:394–397. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcial M A, Madara J L. Cryptosporidium: cellular localization, structural analysis of absorptive cell-parasite membrane-membrane interactions in guinea pigs, and suggestion of protozoan transport by M cells. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:583–594. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)91112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miliotis M D, Tall B D, Gray R H. Adherence to and invasion of tissue culture cells by Vibrio hollisae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4959–4963. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4959-4963.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchison T P, Cramer L P. Actin-based cell motility and cell locomotion. Cell. 1996;84:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morisaki J H, Heuser J E, Sibley L D. Invasion of Toxoplasma gondii occurs by active penetration of the host cell. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2457–2464. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Donoghue P J. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis in man and animals. Int J Parasitol. 1995;25:139–195. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)e0059-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen C. Cryptosporidiosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:903–909. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenshine I, Duronio V, Finlay B B. Tyrosine protein kinase inhibitors block invasin-promoted bacterial uptake by epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2211–2217. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2211-2217.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schafer D A, Jennings P B, Cooper J A. Dynamics of capping protein and actin assembly in vitro: uncapping barbed ends by phosphoinositides. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw M K. Theileria parva sporozoite entry into bovine lymphocytes involves both parasite and host cell signal transduction processes. Exp Parasitol. 1996;84:344–354. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu Y, Mobley J L, Finkelstein L D, Chan A S. A role for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the regulation of beta 1 integrin activity by the CD2 antigen. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1867–1880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephens L R, Jackson T R, Hawkins P T. Agonist-stimulated synthesis of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate: a new intracellular signaling system? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1179:27–75. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90072-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theriot J A. The cell biology of infection by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanhaesebroeck B, Leevers S J, Panayotou G, Waterfield M D. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases: a conserved family of signal transducers. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wennström S, Hawkins P, Cooke F, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Kasuga M, Jackson T, Claesson-Welsh L, Stephens L. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase is required for PDGF-stimulated membrane ruffling. Curr Biol. 1994;4:385–393. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wymann M P, Bulgarelli-Leva G, Zvelebil M J, Pirola L, Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield M D, Panayotou G. Wortmannin inactivates phosphoinositide 3-kinase by covalent modification of Lys-802, a residue involved in the phosphate transfer reaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1722–1733. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang S, Healey M C, Du C, Zhang J. Complete development of Cryptosporidium parvum in bovine fallopian tube epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:349–354. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.349-354.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikawa H, Iseki M. Freeze-fracture study of the site of attachment of Cryptosporidium muris in gastric glands. J Protozool. 1992;39:539–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb04848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]