Abstract

Background

Neuroinflammation has been shown to be an important pathophysiological disease mechanism in frontotemporal dementia (FTD). This includes activation of microglia, a process that can be measured in life through assaying different glia‐derived biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid. However, only a few studies so far have taken place in FTD, and even fewer focusing on the genetic forms of FTD.

Methods

We investigated the cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of TREM2, YKL‐40 and chitotriosidase using immunoassays in 183 participants from the Genetic FTD Initiative (GENFI) study: 49 C9orf72 (36 presymptomatic, 13 symptomatic), 49 GRN (37 presymptomatic, 12 symptomatic) and 23 MAPT (16 presymptomatic, 7 symptomatic) mutation carriers and 62 mutation‐negative controls. Concentrations were compared between groups using a linear regression model adjusting for age and sex, with 95% bias‐corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals. Concentrations in each group were correlated with the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) score using non‐parametric partial correlations adjusting for age. Age‐adjusted z‐scores were also created for the concentration of markers in each participant, investigating how many had a value above the 95th percentile of controls.

Results

Only chitotriosidase in symptomatic GRN mutation carriers had a concentration significantly higher than controls. No group had higher TREM2 or YKL‐40 concentrations than controls after adjusting for age and sex. There was a significant negative correlation of chitotriosidase concentration with MMSE in presymptomatic GRN mutation carriers. In the symptomatic groups, for TREM2 31% of C9orf72, 25% of GRN, and 14% of MAPT mutation carriers had a concentration above the 95th percentile of controls. For YKL‐40 this was 8% C9orf72, 8% GRN and 0% MAPT mutation carriers, whilst for chitotriosidase it was 23% C9orf72, 50% GRN, and 29% MAPT mutation carriers.

Conclusions

Although chitotriosidase concentrations in GRN mutation carriers were the only significantly raised glia‐derived biomarker as a group, a subset of mutation carriers in all three groups, particularly for chitotriosidase and TREM2, had elevated concentrations. Further work is required to understand the variability in concentrations and the extent of neuroinflammation across the genetic forms of FTD. However, the current findings suggest limited utility of these measures in forthcoming trials.

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that leads to progressive behavioral, linguistic and motor disturbances, often at a relatively young age. It is genetic in about a third of cases, with mutations in C9orf72, GRN and MAPT being the commonest causes. 1 However, little is known about the underlying pathophysiological processes that occur in FTD. The study of asymptomatic at‐risk genetic FTD family members has provided a unique window into the pathogenesis and evolution of the disorder over time with deeply phenotyped cohort studies such as the Genetic FTD Initiative (GENFI) allowing in vivo analysis of biomarkers indicative of cellular dysfunction. 2 , 3 , 4 An area of recent interest in FTD has been that of chronic neuroinflammation and glial dysfunction and how these processes contribute to disease. 5 , 6

Neuroinflammation is a complex and multistage process involving activation of specific cells such as microglia within the central nervous system and release of a series of pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory factors. Studies in FTD have recently started to focus on measuring microglial activation during life through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers. Such measures include soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), which has been extensively investigated in Alzheimer's disease (AD), 7 , 8 , 9 and the chitinases. This second group includes chitotriosidase (CHIT1) and YKL‐40 (otherwise known as chitinase‐3‐like protein 1 or CHI3L1). Investigation of each of these measures has so far shown mixed results, with some studies reporting higher levels and some suggesting that there are no differences from controls. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 The majority of these studies have examined an undifferentiated FTD cohort, not stratified by genetic or pathological subtype, but in the small studies that have investigated specific forms of FTD, there is some evidence for a particular role of microglial activation in those with progranulin (GRN) mutations 12 , 16 and those with associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). 14

We therefore set out to establish whether levels of glia‐derived biomarkers vary according to the genetic FTD subtype, and also whether levels change presymptomatically in each genetic subtype, using CSF samples from the GENFI cohort.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the international multicentre GENFI study including sites in the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden, Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, France, Portugal, Italy, and Germany. Ethical approval was obtained for the study, and all participants provided informed written consent. Participants underwent a standardised GENFI clinical assessment including a medical history, physical examination, and the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE).

CSF samples were collected from participants at individual GENFI sites and then processed and stored at −80°C at each site according to a standardised GENFI protocol. CSF samples collected from participants at other external GENFI sites were transferred to University College London (UCL) at −80°C and on arrival were immediately stored at −80°C until being thawed on the day of the experiment.

In total, samples from 183 participants were used: 62 mutation‐negative controls and 121 mutation carriers. In the mutation carrier group there were 49 C9orf72 mutation carriers (36 presymptomatic and 13 symptomatic, all with behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD 17 ), except 1 with FTD‐ALS 18 ), 49 GRN mutation carriers (37 presymptomatic and 12 symptomatic, of whom 8 had bvFTD and 4 had primary progressive aphasia 19 ), and 23 MAPT mutation carriers (16 presymptomatic and 7 symptomatic, all with bvFTD).

Immunoassays were used to measure concentrations of soluble TREM2, YKL‐40 and chitotriosidase as per below, with each assay carried out in duplicate by a single experimenter (IW) on all samples on the same day at UCL. Coefficients of variation were less than 10% for each assay.

CSF soluble TREM2 levels were measured using a previously published immunoassay 20 on the Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) platform, with a biotinylated polyclonal goat anti‐human TREM2 capture antibody (0.25 μg/mL; BAF1828, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and monoclonal mouse anti‐human TREM2 detection antibody (1 μg/mL; (B‐3): sc373828, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Texas, USA). The two chitinase proteins were measured as follows: CSF YKL‐40 levels using the commercially available Human YKL‐40 Immunoassay Kit on the MSD platform and CSF chitotriosidase (CHIT1) levels using the commercially available CircuLex Human ELISA Kit (MBL International, Woburn, MA, USA). Coefficients of variation were less than 10% for each assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. Sex and age were compared between groups using chi‐squared and t‐tests, respectively.

Concentrations of each of the glia‐derived biomarkers were compared between groups using a linear regression model adjusting for age and sex, with 95% bias‐corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals with 1000 repetitions (as data was non‐normally distributed).

The association of concentrations of each of the three biomarkers with the MMSE score was investigated in each genetic group by assessing non‐parametric partial correlations (adjusting for age).

Lastly, the association of concentrations of each the three biomarkers with age was assessed by performing a Spearman correlation with each measure in controls as well as looking at the mean and standard deviation concentration in each decade of life from the 20s to the 60s. These values were used to create an age‐adjusted z‐score for each participant in each measure. We then investigated how many individual participants had an abnormal z‐score, defined as being above the 95th centile (z = 1.65) of controls.

Results

Demographics

The presymptomatic C9orf72, GRN, and MAPT mutation carrier groups were not significantly different in sex or age to the control group, but each of the symptomatic groups contained more men and were older than the controls (p < 0.05 for each comparison).

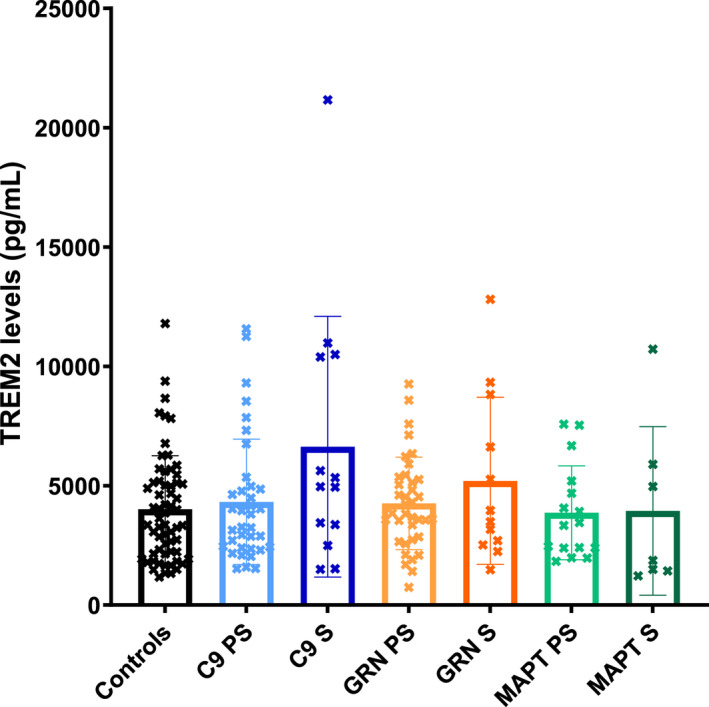

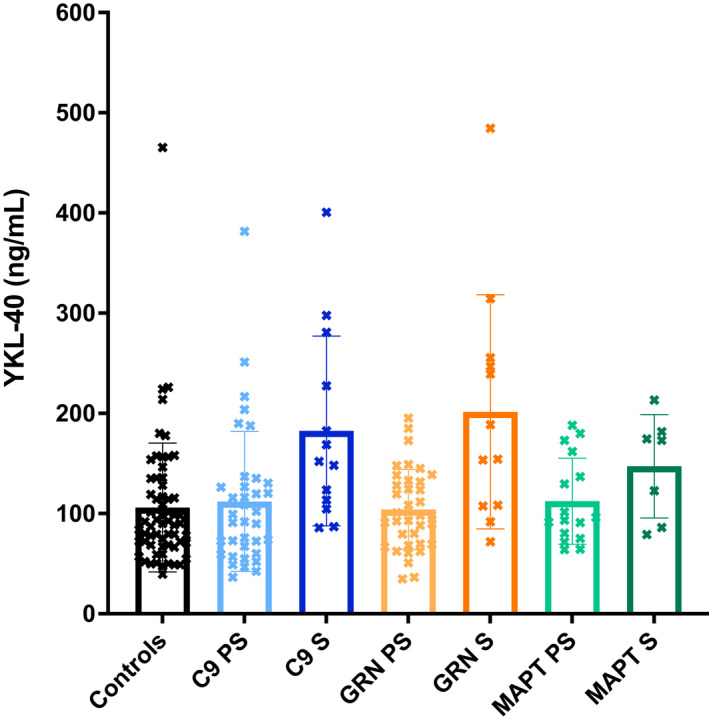

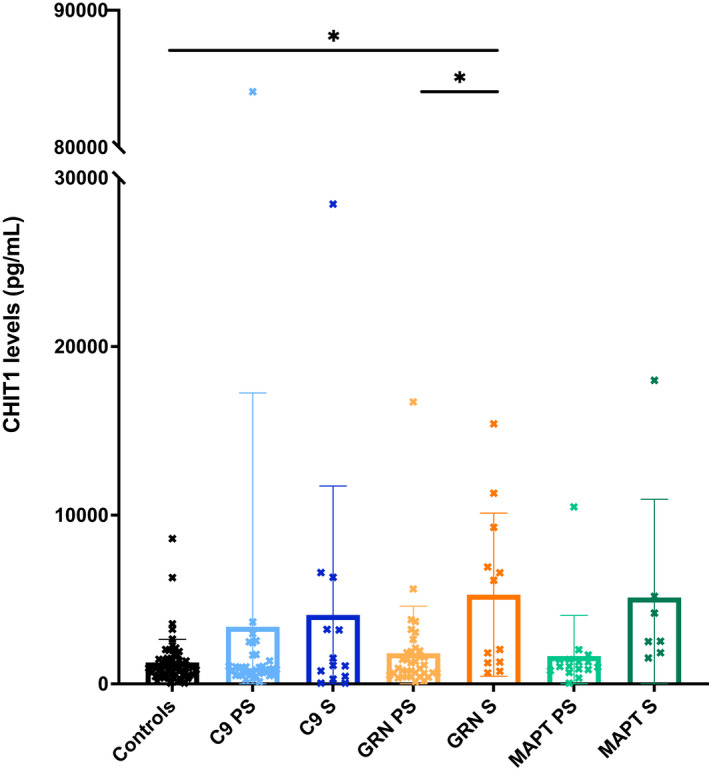

Microglial activation markers in each genetic group

No significant differences were seen between groups for either TREM2 (Table 1; Fig. 1; Table S1A) or YKL‐40 (Table 1; Fig. 2; Table S1B). However, the chitotriosidase concentrations were higher in the symptomatic GRN mutation carriers compared with both the controls (adjusted mean difference 3683.5, 95% confidence intervals 776.5, 6590.5, p = 0.013) and presymptomatic GRN mutation carriers (3203.1, 95% CI 10.3, 6395.8, p = 0.049) (Table 1; Fig. 3; Table S1C).

Table 1.

Demographic data showing the number of participants as well as the age, sex (percentage males) and education of each group.

| Control | C9orf72 presymptomatic | C9orf72 symptomatic | GRN presymptomatic | GRN symptomatic | MAPT presymptomatic | MAPT symptomatic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 62 | 36 | 13 | 37 | 12 | 16 | 7 |

| Sex (N and % of male in each group) | 27 (43.5) | 15 (41.7) | 10 (76.9) | 18 (48.6) | 6 (50) | 5 (31.3) | 5 (71.4) |

| Age at CSF collection, years, mean (SD) | 46.0 (13.2) | 45.7 (11.2) | 65.3 (8.5) | 47.9 (12.5) | 65.0 (6.1) | 44.2 (10.4) | 58.6 (6.7) |

| CSF TREM2, pg/mL, mean (SD) | 4015.2 (2238.7) | 4323.9 (2630.1) | 6633.5 (5461.5) | 4260.9 (1936.4) | 5203.3 (3499.9) | 3869.6 (1964.0) | 3944.2 (3532.7) |

| CSF YKL‐40, ng/mL, mean (SD) | 106.1 (64.2) | 112.0 (69.8) | 182.5 (94.7) | 104.0 (39.9) | 201.4 (116.9) | 112.4 (43.0) | 147.2 (51.6) |

| CSF CHIT1, pg/mL, mean (SD) | 1268.8 (1367.1) | 3388.9 (13852.8) | 4083.2 (7649.5) | 1811.4 (2792.2) | 5288.2 (4829.6) | 1645.2 (2408.5) | 5113.6 (5828.6) |

Figure 1.

Mean concentrations within each group of TREM2. S = symptomatic, PS = presymptomatic.

Figure 2.

Mean concentrations within each group of YKL‐40. S = symptomatic, PS = presymptomatic.

Figure 3.

Mean concentrations within each group of CHIT1. S = symptomatic, PS = presymptomatic.

Five participants had undetectable levels of chitotriosidase in CSF, including on repeat testing. These were two symptomatic C9orf72 mutation carriers, one asymptomatic MAPT mutation carrier and two controls. Approximately 6% of the population possess a homozygous 24 base pair duplication in exon 10 of the CHIT1 gene, which leads to a complete enzymatic deficiency of chitotriosidase (Boot et al, 1998) and undetectable levels of chitotriosidase in CSF (Abu‐Rumeileh et al, 2019). These five individuals (2.7% cohort) were likely to be carriers of this mutation, given their undetectable levels. A repeat analysis excluding these cases did not affect the main results, with a significant difference still seen between symptomatic GRN mutation carriers and controls (adjusted mean difference 3525.0, 95% confidence intervals 553.6, 6496.3, p = 0.020).

Correlation of microglial markers with cognition

The only significant (negative) correlation of the measures with MMSE was seen with chitotriosidase concentration in the presymptomatic GRN mutation carriers (r = −0.51, p = 0.0016, Table 2; Fig. S1).

Table 2.

Partial correlations (adjusting for age) between microglial activation markers and cognition measured by the Mini‐Mental State Examination. r values are shown with p‐values below; significant correlations are shown in bold.

| Genetic group | Genetic status | TREM2 | YKL‐40 | CHIT1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C9orf72 | Presymptomatic | −0.03 | −0.16 | −0.11 |

| 0.8282 | 0.3439 | 0.5161 | ||

| Symptomatic | 0.09 | −0.22 | −0.16 | |

| 0.7969 | 0.5086 | 0.6849 | ||

| GRN | Presymptomatic | −0.24 | −0.27 | −0.51 |

| 0.1585 | 0.1199 | 0.0016 | ||

| Symptomatic | 0.20 | −0.48 | −0.25 | |

| 0.6332 | 0.2272 | 0.5493 | ||

| MAPT | Presymptomatic | −0.23 | 0.04 | −0.28 |

| 0.4287 | 0.8973 | 0.3484 | ||

| Symptomatic | −0.64 | −0.37 | −0.79 | |

| 0.2438 | 0.5384 | 0.1105 |

Age‐adjusted z‐scores

Mean (standard deviation) concentrations of each of the markers in each of decade of life from 20 to 70 in the controls are shown in Table S2 along with the Spearman correlations of each measure with age: TREM2 r = 0.42, p = 0.0008, YKL‐40 r = 0.71, p < 0.0001, chitotriosidase r = 0.21, p = 0.1013.

In the symptomatic groups, for TREM2, 31% of C9orf72 mutation carriers, 25% of GRN mutation carriers and 14% of MAPT mutation carriers had a concentration above the 95th percentile of controls (Table 3). Fewer presymptomatic participants had a high concentration but for the C9orf72 (14%) and MAPT (13%) mutation groups the percentage of cases was above 5%.

Table 3.

Percentage of participants in each group where the concentration of the microglial activation marker was higher than an age‐adjusted z‐score of 1.65.

| Genetic group | Genetic status | TREM2 | YKL‐40 | CHIT1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C9orf72 | Presymptomatic | 14 | 8 | 8 |

| Symptomatic | 31 | 8 | 23 | |

| GRN | Presymptomatic | 5 | 0 | 11 |

| Symptomatic | 25 | 8 | 50 | |

| MAPT | Presymptomatic | 13 | 19 | 6 |

| Symptomatic | 14 | 0 | 29 |

Only 8% of symptomatic C9orf72 and GRN mutation carriers and none of the symptomatic MAPT mutation carriers had a concentration above the 95% centile for YKL‐40, with variable numbers in the presymptomatic mutation carriers.

However, for chitotriosidase 50% of the symptomatic GRN group, 29% of the MAPT group and 23% of the C9orf72 group had a high concentration. As with the other measures, there were fewer cases with high concentrations in the presymptomatic group with 11% of GRN, 8% of C9orf72, and 6% of MAPT mutation carriers having a chitotriosidase level above the 95th percentile.

Discussion

This study examined levels of three glia‐derived biomarkers, TREM2, YKL‐40 and chitotriosidase, in the CSF of people with genetic FTD due to mutations in GRN, C9orf72, and MAPT. On a group basis only chitotriosidase levels were raised, and only in the symptomatic GRN mutation carrier group. No changes were seen in the presymptomatic groups compared with controls. However in the presymptomatic GRN mutation carrier group there was a significant negative correlation with MMSE suggesting that chitotriosidases levels increase in proximity to symptom onset as cognition starts to become affected. Investigating age‐adjusted individual values of the biomarkers, concentrations are very variable in each presymptomatic and symptomatic genetic group, but there are higher proportions of people than expected with increased levels, particularly of TREM2 and chitotriosidase across all three symptomatic genetic groups.

There have been few other studies of glia‐derived biomarkers in genetic FTD. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 21 An initial small study of CSF chitotriosidase 13 found similar levels in genetic FTD to controls, but cohorts included a smaller number of cases and combined genetic subtypes into one group rather than investigating each subtype. In one further study that investigated specific genetic groups in small cohorts, increased chitotriosidase was seen only in GRN mutation carriers. 16 This current study adds to these prior investigations by showing raised levels of chitotriosidase in GRN mutation carriers as a group but also higher levels in a subset of patients from the other genetic groups as well.

Raised chitotriosidase levels in GRN mutation carriers are consistent with multiple studies showing raised levels of other inflammatory markers in CSF or blood 3 , 22 , 23 , 24 and significant microglial dysfunction and activation in GRN mutation mouse models. 25 , 26 , 27 GRN mutation models also display lipid accumulating microglia with extensive lysosomal dysfunction, 28 , 29 and lysosomal dysfunction is seen in human GRN mutation carriers. 30 , 31 This could alter delivery of proteins to the glial cell membrane or affect release into CSF. CSF chitotriosidase levels are highly elevated in the lysosomal storage disorder Gaucher's disease, 32 where macrophages are chronically activated and lysosomes are overwhelmed by accumulation of the sphingolipid glucocerebroside. Raised chitotriosidase levels in GRN mutation carriers may therefore represent chronic lysosomal failure of microglia due to progranulin insufficiency and lipid mishandling.

Chitotriosidase may be released from glial cells once neurodegeneration develops, as a generalised protective response. Excessively activated or dysfunctional, degenerating (senescent) microglia (due to mutation‐related mechanisms) may lead to a sustained increase in release of these proteins. This is likely to occur presymptomatically in GRN mutation carriers where abnormalities can already be seen in MRI white matter hyperintensities, 33 which are associated with astrocytic and microglial activation and dystrophy. Evidence from the significant negative correlation with cognition suggests a rise in chitotriosidase as symptom onset approaches.

YKL‐40, otherwise known as chitinase‐3‐like protein 1, falls within the same chitinase class of proteins as chitotriosidase. Its levels are raised in multiple acute and chronic neurological disorders including AD. While a small number of studies have shown raised levels in undifferentiated FTD cohorts, 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 there are fewer studies of particular pathogenetic forms. In those that have investigated specific groups, higher concentrations of YKL‐40 are found in those with associated ALS, 14 and in one prior small study from our group, in people with GRN and MAPT mutations. 16 However, in this study we did not find raised levels in any of the three genetic forms of FTD when studied as groups or even a substantially increased number of cases with higher concentrations in the age‐adjusted z‐score analysis. The reason for these differences are unclear, but it is likely that the different pathophysiological forms of FTD have differing neuroinflammatory responses and when an undifferentiated FTD cohort is studied, the presence of a difference between that group and controls will depend on the exact pathological composition of the group. Further work is needed in this area but it suggests that at least for genetic forms of FTD, CSF YKL‐40 is not an ideal candidate for measuring neuroinflammation in clinical trials.

Similarly, TREM2 levels were not raised in the group comparisons for any of the three genotypes. However, a subset of cases in each of the C9orf72, GRN and MAPT mutation groups had high concentrations. As TREM2 normally promotes microglial activation, proliferation, migration, and survival, 34 raised TREM2 levels may be a normal, protective response, supporting microglia during early neurodegeneration, suggesting that the rise in a subset of mutation carriers may be stage‐dependent. Further work is needed to look at what factors might cause raised levels in some cases but not others, and whether there are factors that might even impair sTREM2 release, causing a failure of levels to rise appropriately (and therefore potentially reducing microglial survival and exacerbating neuronal dysfunction further).

In the C9orf72 patient group, levels of all glia‐derived biomarkers were similar to controls as a group but on investigation of individual values a subset of patients had high concentrations. Certainly mouse models of C9orf72 expansions demonstrate florid glial activation. 35 , 36 However, a recent study found that immune dysfunction and microglial activation in a C9orf72 model vary widely according to the mouse gut microbiome. 37 Variants in TMEM106B also modify effects of the C9orf72 expansion by impacting lysosomal function. 38 These mechanisms may underlie the wide variability in glia‐derived biomarker levels in the C9orf72 group. Examination of the impact of environmental and genetic modifiers on neuroinflammatory biomarkers in a larger C9orf72 cohort would be useful to explore this. Intriguingly, CSF chitotriosidase levels in those with C9orf72 expansions and an ALS phenotype have been previously shown to be higher than those with an FTD phenotype 39 and future studies examining the interaction of these features will be important.

Similarly to the C9orf72 group, the symptomatic MAPT mutation carriers showed no differences as a group to controls for any of the three glia‐derived markers. However, for chitotriosidase 29% of symptomatic mutation carriers, and for TREM2 14% of symptomatic mutation carriers, had concentrations above the 95th centile cutoff for controls. Certainly some previous non‐clinical studies have suggested a role for inflammation in MAPT‐associated FTD, 40 , 41 so it will be important to investigate other inflammatory biomarkers and whether the change in MAPT mutations is stage‐specific.

The positive association of TREM2 and YKL‐40 levels with age is consistent with previous studies in sporadic FTD and AD. 10 , 42 , 43 Microglial activity increases with aging, which may augment release of TREM2 by microglia as a protective response to neuronal loss in aging individuals, 34 and this may also be the case for YKL‐40. Chitotriosidase levels were not associated with age in any group, consistent with other studies of AD and FTD. 13 , 14 This suggests that the high CSF chitotriosidase levels in patients with GRN mutations represents excessive microglial activation or dysfunction related to the underlying mutation itself, or neurodegeneration, rather than aging. It also emphasises the importance of adjusting analyses of fluid biomarker levels for age when comparing groups of individuals with large age ranges, particularly when age independently affects the biological function of interest.

Limitations of the study include the small size of the patient subgroups once stratified which may have limited power to detect significant differences between groups. However, this is inherent to a rare disease like genetic FTD. Measurement of chitotriosidase is in part limited by the occurrence of people with undetectable levels (five participants in this cohort), likely due to mutations in CHIT1 and future studies should take this into account. Longitudinal measurements of glia‐derived biomarkers in CSF will be helpful to investigate in the future, including in individuals who convert during the study, allowing analysis of the hypothesis that chitotriosidase levels change in proximity to symptom onset.

In summary, whilst CSF chitotriosidase was the most promising biomarker in this study as a potential in vivo measure of neuroinflammation in genetic FTD, particularly in those with GRN mutations, there is much variability within each genetic group. More work is needed to understand the reasons for that variability e.g. whether it is related to the specific stage of the disease, or whether there are inherent pathophysiological differences in the extent of the neuroinflammatory response in some mutation carriers in comparison to others. This variability may spell problems for their use in clinical trials. Although some mutation carriers have high concentrations, others have levels that overlap with controls i.e. there is little dynamic range for ‘lowering’ of a neuroinflammatory measure in a therapeutic trial when the concentration is already in the control range. Many of the proposed drugs for genetic FTD target neuroinflammation either directly or indirectly but the findings in this study suggest that we have not yet found the ideal measure of this important pathophysiological process for such trials.

Conflicts of Interest

HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Alector, Annexon, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Pinteon Therapeutics, Red Abbey Labs, Passage Bio, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure, Biogen, and Roche, and is a co‐founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

IOCW and JDR contributed to the study design and acquisition and, analysis of the samples. IOCW, JDR, and IS contributed to the statistical interpretation of the data as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. All other authors contributed to the acquisition of data and study coordination as well as helping to critically review and revise the manuscript.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided informed written consent prior to their inclusion.

Supporting information

Table S1 Adjusted mean differences, 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals, and p‐values from the linear regression models (adjusted for age and sex): (A) TREM2, (B) YKL‐40, (C) CHIT1. PS is presymptomatic, S is symptomatic.

Table S2. Mean (standard deviation) concentrations of the microglial activation markers in each decade of life within the controls (excluding the two undetectable concentrations of CHIT1 in controls). Spearman correlation of each measure with age was as follows: TREM2 r = 0.42, p = 0.0008, YKL‐40 r = 0.71, p < 0.0001, CHIT1 r = 0.21, p = 0.1013.

Figure S1. Partial correlations (adjusting for age) of CHIT1 with Mini‐Mental State Examination in GRN mutation carriers (A) presymptomatic and (B) symptomatic.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research participants for their contribution to the study.

List of GENFI consortium authors.

| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Annabel Nelson | Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| Martina Bocchetta | Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| David Cash | Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| David L. Thomas | Neuroimaging Analysis Centre, Department of Brain Repair and Rehabilitation, UCL Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London, UK |

| Emily Todd | Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| Hanya Benotmane | UK Dementia Research Institute at University College London, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| Jennifer Nicholas | Department of Medical Statistics, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK |

| Kiran Samra | Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| Rachelle Shafei | Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, UK |

| Carolyn Timberlake | Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK |

| Thomas Cope | Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK |

| Timothy Rittman | Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK |

| Alberto Benussi | Centre for Neurodegenerative Disorders, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy |

| Enrico Premi | Stroke Unit, ASST Brescia Hospital, Brescia, Italy |

| Roberto Gasparotti | Neuroradiology Unit, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy |

| Silvana Archetti | Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Diagnostics, ASST Brescia Hospital, Brescia, Italy |

| Stefano Gazzina | Neurology, ASST Brescia Hospital, Brescia, Italy |

| Valentina Cantoni | Centre for Neurodegenerative Disorders, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy |

| Andrea Arighi | Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Neurodegenerative Diseases Unit, Milan, Italy; University of Milan, Centro Dino Ferrari, Milan, Italy |

| Chiara Fenoglio | Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Neurodegenerative Diseases Unit, Milan, Italy; University of Milan, Centro Dino Ferrari, Milan, Italy |

| Elio Scarpini | Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Neurodegenerative Diseases Unit, Milan, Italy; University of Milan, Centro Dino Ferrari, Milan, Italy |

| Giorgio Fumagalli | Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Neurodegenerative Diseases Unit, Milan, Italy; University of Milan, Centro Dino Ferrari, Milan, Italy |

| Vittoria Borracci | Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Neurodegenerative Diseases Unit, Milan, Italy; University of Milan, Centro Dino Ferrari, Milan, Italy |

| Giacomina Rossi | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| Giorgio Giaccone | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| Giuseppe Di Fede | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| Paola Caroppo | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| Pietro Tiraboschi | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| Sara Prioni | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| Veronica Redaelli | Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy |

| David Tang‐Wai | The University Health Network, Krembil Research Institute, Toronto, Canada |

| Ekaterina Rogaeva | Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada |

| Miguel Castelo‐Branco | Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

| Morris Freedman | Baycrest Health Sciences, Rotman Research Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada |

| Ron Keren | The University Health Network, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Toronto, Canada |

| Sandra Black | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Sunnybrook Research Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada |

| Sara Mitchell | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Sunnybrook Research Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada |

| Christen Shoesmith | Department of Clinical Neurological Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada |

| Robart Bartha | Department of Medical Biophysics, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada; Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping, Robarts Research Institute, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada |

| Rosa Rademakers | Center for Molecular Neurology, University of Antwerp |

| Jackie Poos | Department of Neurology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Janne M. Papma | Department of Neurology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Lucia Giannini | Department of Neurology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Rick van Minkelen | Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Yolande Pijnenburg | Amsterdam University Medical Centre, Amsterdam VUmc, Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Benedetta Nacmias | Department of Neuroscience, Psychology, Drug Research and Child Health, University of Florence, Florence, Italy |

| Camilla Ferrari | Department of Neuroscience, Psychology, Drug Research and Child Health, University of Florence, Florence, Italy |

| Cristina Polito | Department of Biomedical, Experimental and Clinical Sciences “Mario Serio”, Nuclear Medicine Unit, University of Florence, Florence, Italy |

| Gemma Lombardi | Department of Neuroscience, Psychology, Drug Research and Child Health, University of Florence, Florence, Italy |

| Valentina Bessi | Department of Neuroscience, Psychology, Drug Research and Child Health, University of Florence, Florence, Italy |

| Michele Veldsman | Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK |

| Christin Andersson | Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden |

| Hakan Thonberg | Center for Alzheimer Research, Division of Neurogeriatrics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden |

| Linn Öijerstedt | Center for Alzheimer Research, Division of Neurogeriatrics, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Bioclinicum, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden; Unit for Hereditary Dementias, Theme Aging, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Sweden |

| Vesna Jelic | Division of Clinical Geriatrics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden |

| Paul Thompson | Division of Neuroscience and Experimental Psychology, Wolfson Molecular Imaging Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK |

| Tobias Langheinrich | Division of Neuroscience and Experimental Psychology, Wolfson Molecular Imaging Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; Manchester Centre for Clinical Neurosciences, Department of Neurology, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK |

| Albert Lladó | Alzheimer's disease and Other Cognitive Disorders Unit, Neurology Service, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain |

| Anna Antonell | Alzheimer's disease and Other Cognitive Disorders Unit, Neurology Service, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain |

| Jaume Olives | Alzheimer's disease and Other Cognitive Disorders Unit, Neurology Service, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain |

| Mircea Balasa | Alzheimer's disease and Other Cognitive Disorders Unit, Neurology Service, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain |

| Nuria Bargalló | Imaging Diagnostic Center, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain |

| Sergi Borrego‐Ecija | Alzheimer's disease and Other Cognitive Disorders Unit, Neurology Service, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain |

| Ana Verdelho | Department of Neurosciences and Mental Health, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte – Hospital de Santa Maria & Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal |

| Carolina Maruta | Laboratory of Language Research, Centro de Estudos Egas Moniz, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal |

| Catarina B. Ferreira | Laboratory of Neurosciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal |

| Gabriel Miltenberger | Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal |

| Frederico Simões do Couto | Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Católica Portuguesa |

| Alazne Gabilondo | Cognitive Disorders Unit, Department of Neurology, Donostia University Hospital, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain; Neuroscience Area, Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Ana Gorostidi | Neuroscience Area, Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Jorge Villanua | OSATEK, University of Donostia, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Marta Cañada | CITA Alzheimer, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Mikel Tainta | Neuroscience Area, Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Miren Zulaica | Neuroscience Area, Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Myriam Barandiaran | Cognitive Disorders Unit, Department of Neurology, Donostia University Hospital, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain; Neuroscience Area, Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain |

| Patricia Alves | Neuroscience Area, Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, San Sebastian, Gipuzkoa, Spain; Department of Educational Psychology and Psychobiology, Faculty of Education, International University of La Rioja, Logroño, Spain |

| Benjamin Bender | Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany |

| Carlo Wilke | Department of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Hertie‐Institute for Clinical Brain Research and Center of Neurology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Tübingen, Germany |

| Lisa Graf | Department of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Hertie‐Institute for Clinical Brain Research and Center of Neurology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany |

| Annick Vogels | Department of Human Genetics, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium |

| Mathieu Vandenbulcke | Geriatric Psychiatry Service, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium; Neuropsychiatry, Department of Neurosciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium |

| Philip Van Damme | Neurology Service, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium; Laboratory for Neurobiology, VIB‐KU Leuven Centre for Brain Research, Leuven, Belgium |

| Rose Bruffaerts | Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium; Biomedical Research Institute, Hasselt University, 3500 Hasselt, Belgium |

| Koen Poesen | Laboratory for Molecular Neurobiomarker Research, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium |

| Pedro Rosa‐Neto | Translational Neuroimaging Laboratory, McGill Centre for Studies in Aging, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada |

| Serge Gauthier | Alzheimer Disease Research Unit, McGill Centre for Studies in Aging, Department of Neurology & Neurosurgery, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada |

| Agnès Camuzat | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France |

| Alexis Brice | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN‐RND) |

| Anne Bertrand | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Inria, Aramis project‐team, F‐75013, Paris, France; Centre pour l'Acquisition et le Traitement des Images, Institut du Cerveau et la Moelle, Paris, France |

| Aurélie Funkiewiez | Centre de référence des démences rares ou précoces, IM2A, Département de Neurologie, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France |

| Daisy Rinaldi | Centre de référence des démences rares ou précoces, IM2A, Département de Neurologie, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Département de Neurologie, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France |

| Dario Saracino | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Inria, Aramis project‐team, F‐75013, Paris, France; Centre de référence des démences rares ou précoces, IM2A, Département de Neurologie, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France |

| Olivier Colliot | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Inria, Aramis project‐team, F‐75013, Paris, France; Centre pour l'Acquisition et le Traitement des Images, Institut du Cerveau et la Moelle, Paris, France |

| Sabrina Sayah | Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute – Institut du Cerveau – ICM, Inserm U1127, CNRS UMR 7225, AP‐HP – Hôpital Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France |

| Catharina Prix | Neurologische Klinik, Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München, Munich, Germany |

| Elisabeth Wlasich | Neurologische Klinik, Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München, Munich, Germany |

| Olivia Wagemann | Neurologische Klinik, Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München, Munich, Germany |

| Sandra Loosli | Neurologische Klinik, Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München, Munich, Germany |

| Sonja Schönecker | Neurologische Klinik, Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München, Munich, Germany |

| Tobias Hoegen | Neurologische Klinik, Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München, Munich, Germany |

| Jolina Lombardi | Department of Neurology, University of Ulm, Ulm |

| Sarah Anderl‐Straub | Department of Neurology, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany |

| Adeline Rollin | CHU, CNR‐MAJ, Labex Distalz, LiCEND Lille, France |

| Gregory Kuchcinski | Univ Lille, France; Inserm 1172, Lille, France; CHU, CNR‐MAJ, Labex Distalz, LiCEND Lille, France |

| Maxime Bertoux | Inserm 1172, Lille, France; CHU, CNR‐MAJ, Labex Distalz, LiCEND Lille, France |

| Thibaud Lebouvier | Univ Lille, France; Inserm 1172, Lille, France; CHU, CNR‐MAJ, Labex Distalz, LiCEND Lille, France |

| Vincent Deramecourt | Univ Lille, France; Inserm 1172, Lille, France; CHU, CNR‐MAJ, Labex Distalz, LiCEND Lille, France |

| Beatriz Santiago | Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar e Universitario de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

| Diana Duro | Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

| Maria João Leitão | Centre of Neurosciences and Cell Biology, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

| Maria Rosario Almeida | Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

| Miguel Tábuas‐Pereira | Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar e Universitario de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

| Sónia Afonso | Instituto Ciencias Nucleares Aplicadas a Saude, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal |

[Correction added on 19 October 2022, after first online publication: Genetic FTD Initiative, GENFI was added to the author list.]

Funding Information

The Dementia Research Centre is supported by Alzheimer's Research UK, Alzheimer's Society, Brain Research UK, and The Wolfson Foundation. This work was supported by the NIHR UCL/H Biomedical Research Centre, the Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre (LWENC) Clinical Research Facility, and the UK Dementia Research Institute, which receives its funding from UK DRI Ltd, funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Alzheimer's Society and Alzheimer's Research UK. IOCW was supported by an MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship (MR/M018288/1). JDR is supported by the Miriam Marks Brain Research UK Senior Fellowship and has received funding from an MRC Clinician Scientist Fellowship (MR/M008525/1) and the NIHR Rare Disease Translational Research Collaboration (BRC149/NS/MH). This work was also supported by the MRC UK GENFI grant (MR/M023664/1), the Bluefield Project and the JPND GENFI‐PROX grant (2019‐02248). Several authors of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases – Project ID No 739510. RC/CG are supported by a Frontotemporal Dementia Research Studentships in Memory of David Blechner funded through The National Brain Appeal (RCN 290173). MB is supported by a Fellowship award from the Alzheimer's Society, UK (AS‐JF‐19a‐004‐517). MB's work is also supported by the UK Dementia Research Institute which receives its funding from DRI Ltd, funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Alzheimer's Society and Alzheimer's Research UK. JCVS was supported by the Dioraphte Foundation grant 09‐02‐03‐00, the Association for Frontotemporal Dementias Research Grant 2009, The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) grant HCMI 056‐13‐018, ZonMw Memorabel (Deltaplan Dementie, project number 733 051 042), Alzheimer Nederland and the Bluefield project. FM received funding from the Tau Consortium and the Center for Networked Biomedical Research on Neurodegenerative Disease (CIBERNED). RS‐V has received funding from Fundació Marató de TV3, Spain (grant no. 20143810). CG received funding from JPND‐Prefrontals VR Dnr 529‐2014‐7504, VR 2015‐02926 and 2018‐02754, the Swedish FTD Inititative‐Schörling Foundation, Alzheimer Foundation, Brain Foundation and Stockholm County Council ALF. MM has received funding from a Canadian Institute of Health Research operating grant and the Weston Brain Institute and Ontario Brain Institute. JBR has received funding from the Welcome Trust (220258), the Cambridge University Centre for Frontotemporal Dementia, the Medical Research Council (SUAG/051 G101400) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC‐1215‐20014). EF has received funding from a CIHR grant #327387. DG received support from the EU Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) and the Italian Ministry of Health (PreFrontALS) grant 733051042. RV has received funding from the Mady Browaeys Fund for Research into Frontotemporal Dementia. MO has received funding from BMBF (FTLDc). HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2018‐02532), the European Research Council (#681712), Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG‐720931), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#201809‐2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer's Association (#ADSF‐21‐831376‐C, #ADSF‐21‐831381‐C and #ADSF‐21‐831377‐C), the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling‐Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2019‐0228), the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement No 860197 (MIRIADE), European Union Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders (JPND2021‐00694), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL. JL received funding for this work by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany's Excellence Strategy within the framework of the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (EXC 2145 SyNergy – ID 390857198).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA grant 201809‐2016862; Alzheimer's Association grants ADSF‐21‐831376‐C, ADSF‐21‐831377‐C, and ADSF‐21‐831381‐C; Association for Frontotemporal Dementias Research grant 09‐02‐03‐00; CIHR grant 327387; European Research Council grant 681712; Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders grant JPND2021‐00694; Medical Research Council grant MR/M023664/1; Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) grant HCMI 056‐13‐018; Swedish FTD Inititative‐Schörling Foundation grants 2018‐02754, 529‐2014‐7504, and VR 2015‐02926; Swedish Research Council grant 2018‐02532; ZonMw grant 733 051 042; Alzheimer's Research UK; Alzheimer's Society grant AS‐JF‐19a‐004‐517; Brain Research UK ; The Wolfson Foundation ; Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre (LWENC) Clinical Research Facility; UK Dementia Research Institute ; UK DRI Ltd ; MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship grant MR/M018288/1; MRC Clinician Scientist Fellowship grant MR/M008525/1; NIHR Rare Disease Translational Research Collaboration grant BRC149/NS/MH; MRC UK GENFI; Bluefield Project; JPND GENFI‐PROX grant 2019‐02248; The National Brain Appeal grant RCN 290173; Dioraphte Foundation ; Fundació Marató de TV3, Spain grant 20143810; Weston Brain Institute ; Ontario Brain Institute ; Welcome Trust grant 220258; Cambridge University Centre for Frontotemporal Dementia; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre grant BRC‐1215‐20014; EU Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research ; Italian Ministry of Health grant 733051042; Swedish State Support for Clinical Research grant ALFGBG‐720931; the Olav Thon Foundation ; Erling‐Persson Family Foundation ; Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor ; Hjärnfonden, Sweden grant FO2019‐0228; Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant 860197; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft .

Contributor Information

Jonathan D. Rohrer, Email: j.rohrer@ucl.ac.uk.

the Genetic FTD Initiative, GENFI:

Annabel Nelson, Martina Bocchetta, David Cash, David L. Thomas, Emily Todd, Hanya Benotmane, Jennifer Nicholas, Kiran Samra, Rachelle Shafei, Carolyn Timberlake, Thomas Cope, Timothy Rittman, Alberto Benussi, Enrico Premi, Roberto Gasparotti, Silvana Archetti, Stefano Gazzina, Valentina Cantoni, Andrea Arighi, Chiara Fenoglio, Elio Scarpini, Giorgio Fumagalli, Vittoria Borracci, Giacomina Rossi, Giorgio Giaccone, Giuseppe Di Fede, Paola Caroppo, Sara Prioni, Veronica Redaelli, David Tang‐Wai, Ekaterina Rogaeva, Miguel Castelo‐Branco, Morris Freedman, Ron Keren, Sandra Black, Sara Mitchell, Christen Shoesmith, Robart Bartha, Rosa Rademakers, Jackie Poos, Janne M. Papma, Lucia Giannini, Rick van Minkelen, Yolande Pijnenburg, Benedetta Nacmias, Camilla Ferrari, Cristina Polito, Gemma Lombardi, Valentina Bessi, Michele Veldsman, Christin Andersson, Hakan Thonberg, Linn Öijerstedt, Vesna Jelic, Paul Thompson, Tobias Langheinrich, Albert Lladó, Anna Antonell, Jaume Olives, Mircea Balasa, Nuria Bargalló, Sergi Borrego‐Ecija, Ana Verdelho, Carolina Maruta, Catarina B. Ferreira, Gabriel Miltenberger, Frederico Simões do Couto, Alazne Gabilondo, Ana Gorostidi, Jorge Villanua, Marta Cañada, Mikel Tainta, Miren Zulaica, Myriam Barandiaran, Patricia Alves, Benjamin Bender, Carlo Wilke, Lisa Graf, Annick Vogels, Mathieu Vandenbulcke, Philip Van Damme, Rose Bruffaerts, Koen Poesen, Pedro Rosa‐Neto, Serge Gauthier, Agnès Camuzat, Alexis Brice, Anne Bertrand, Aurélie Funkiewiez, Daisy Rinaldi, Dario Saracino, Olivier Colliot, Sabrina Sayah, Catharina Prix, Elisabeth Wlasich, Olivia Wagemann, Sandra Loosli, Sonja Schönecker, Tobias Hoegen, Jolina Lombardi, Sarah Anderl‐Straub, Adeline Rollin, Gregory Kuchcinski, Maxime Bertoux, Thibaud Lebouvier, Vincent Deramecourt, Beatriz Santiago, Diana Duro, Maria João Leitão, Maria Rosario Almeida, Miguel Tábuas‐Pereira, and Sónia Afonso

Data Availability Statement

Some GENFI data are available on reasonable request through application to the GENFI Data Access Committee.

References

- 1. Greaves CV, Rohrer JD. An update on genetic frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol. 2019;266(8):2075‐2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rohrer JD, Nicholas JM, Cash DM, et al. Presymptomatic cognitive and neuroanatomical changes in genetic frontotemporal dementia in the Genetic frontotemporal dementia Initiative (GENFI) study: a cross‐sectional analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(3):253‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heller C, Foiani MS, Moore K, et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein is raised in progranulin‐associated frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(3):263‐270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilke C, Reich S, van Swieten JC, et al. Stratifying the Presymptomatic phase of Genetic frontotemporal dementia by serum NfL and pNfH: a longitudinal multicentre study. Ann Neurol. 2022;91(1):33‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bright F, Werry EL, Dobson‐Stone C, et al. Neuroinflammation in frontotemporal dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(9):540‐555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swift IJ, Sogorb‐Esteve A, Heller C, et al. Fluid biomarkers in frontotemporal dementia: past, present and future. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(2):204‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heslegrave A, Heywood W, Paterson R, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 concentration in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suárez‐Calvet M, Kleinberger G, Araque Caballero MÁ, et al. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker for microglia activity in early‐stage Alzheimer's disease and associate with neuronal injury markers. EMBO mol Med. 2016;8(5):466‐476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suárez‐Calvet M, Morenas‐Rodríguez E, Kleinberger G, et al. Early increase of CSF sTREM2 in Alzheimer's disease is associated with tau related‐neurodegeneration but not with amyloid‐beta pathology. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alcolea D, Vilaplana E, Suárez‐Calvet M, et al. CSF sAPPbeta, YKL‐40, and neurofilament light in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2017;89(2):178‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Illán‐Gala I, Alcolea D, Montal V, et al. CSF sAPPbeta, YKL‐40, and NfL along the ALS‐FTD spectrum. Neurology. 2018;91(17):e1619‐e1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woollacott IOC, Nicholas JM, Heslegrave A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 levels in frontotemporal dementia differ by genetic and pathological subgroup. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oeckl P, Weydt P, Steinacker P, et al. Different neuroinflammatory profile in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia is linked to the clinical phase. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(1):4‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abu‐Rumeileh S, Steinacker P, Polischi B, et al. CSF biomarkers of neuroinflammation in distinct forms and subtypes of neurodegenerative dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;12(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Antonell A, Tort‐Merino A, Ríos J, et al. Synaptic, axonal damage and inflammatory cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in neurodegenerative dementias. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(2):262‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woollacott IOC, Nicholas JM, Heller C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid YKL‐40 and chitotriosidase levels in FrontotemporalDementia vary by clinical, Genetic and pathological subtype. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2020;49(1):56‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456‐2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strong MJ, Abrahams S, Goldstein LH, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS‐FTSD): revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2017;18(3–4):153‐174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorno‐Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006‐1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Banerjee G, Ambler G, Keshavan A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;74(4):1189‐1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Ende EL, Morenas‐Rodriguez E, McMillan C, et al. CSF sTREM2 is elevated in a subset in GRN‐related frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;103:158.e1‐158.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bossù P, Salani F, Alberici A, et al. Loss of function mutations in the progranulin gene are related to pro‐inflammatory cytokine dysregulation in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller ZA, Rankin KP, Graff‐Radford NR, et al. TDP‐43 frontotemporal lobar degeneration and autoimmune disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(9):956‐962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Galimberti D, Bonsi R, Fenoglio C, et al. Inflammatory molecules in frontotemporal dementia: cerebrospinal fluid signature of progranulin mutation carriers. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:182‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martens LH, Zhang J, Barmada SJ, et al. Progranulin deficiency promotes neuroinflammation and neuron loss following toxin‐induced injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):3955‐3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tanaka Y, Matsuwaki T, Yamanouchi K, Nishihara M. Exacerbated inflammatory responses related to activated microglia after traumatic brain injury in progranulin‐deficient mice. Neuroscience. 2013;231:49‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lui H, Zhang J, Makinson SR, et al. Progranulin deficiency promotes circuit‐specific synaptic pruning by microglia via complement activation. Cell. 2016;165(4):921‐935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evers BM, Rodriguez‐Navas C, Tesla RJ, et al. Lipidomic and transcriptomic basis of lysosomal dysfunction in progranulin deficiency. Cell Rep. 2017;20(11):2565‐2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marschallinger J, Iram T, Zardeneta M, et al. Lipid‐droplet‐accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(2):194‐208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Götzl JK, Mori K, Damme M, et al. Common pathobiochemical hallmarks of progranulin‐associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(6):845‐860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ward ME, Chen R, Huang HY, et al. Individuals with progranulin haploinsufficiency exhibit features of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(385):eaah5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim S, Whitley CB, Jarnes JR. Chitotriosidase as a biomarker for gangliosidoses. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2021;29:100803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sudre CH, Bocchetta M, Cash D, et al. White matter hyperintensities are seen only in GRN mutation carriers in the GENFI cohort. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;15:171‐180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhong L, Xu Y, Zhuo R, et al. Soluble TREM2 ameliorates pathological phenotypes by modulating microglial functions in an Alzheimer's disease model. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burberry A, Suzuki N, Wang JY, et al. Loss‐of‐function mutations in the C9ORF72 mouse ortholog cause fatal autoimmune disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(347):347ra93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Rourke JG, Bogdanik L, Yáñez A, et al. C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science. 2016;351(6279):1324‐1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burberry A, Wells MF, Limone F, et al. C9orf72 suppresses systemic and neural inflammation induced by gut bacteria. Nature. 2020;582(7810):89‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Busch JI, Unger TL, Jain N, Tyler Skrinak R, Charan RA, Chen‐Plotkin AS. Increased expression of the frontotemporal dementia risk factor TMEM106B causes C9orf72‐dependent alterations in lysosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(13):2681‐2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barschke P, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Different CSF protein profiles in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia with C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(5):503‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lant SB, Robinson AC, Thompson JC, et al. Patterns of microglial cell activation in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2014;40(6):686‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Olst L, Verhaege D, Franssen M, et al. Microglial activation arises after aggregation of phosphorylated‐tau in a neuron‐specific P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;89:89‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teunissen CE, Elias N, Koel‐Simmelink MJ, et al. Novel diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for pathologic subtypes of frontotemporal dementia identified by proteomics. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;2:86‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Del Campo M, Galimberti D, Elias N, et al. Novel CSF biomarkers to discriminate FTLD and its pathological subtypes. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(10):1163‐1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Adjusted mean differences, 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals, and p‐values from the linear regression models (adjusted for age and sex): (A) TREM2, (B) YKL‐40, (C) CHIT1. PS is presymptomatic, S is symptomatic.

Table S2. Mean (standard deviation) concentrations of the microglial activation markers in each decade of life within the controls (excluding the two undetectable concentrations of CHIT1 in controls). Spearman correlation of each measure with age was as follows: TREM2 r = 0.42, p = 0.0008, YKL‐40 r = 0.71, p < 0.0001, CHIT1 r = 0.21, p = 0.1013.

Figure S1. Partial correlations (adjusting for age) of CHIT1 with Mini‐Mental State Examination in GRN mutation carriers (A) presymptomatic and (B) symptomatic.

Data Availability Statement

Some GENFI data are available on reasonable request through application to the GENFI Data Access Committee.