Abstract

Objective

To assess the association between the continuum of care of mothers and the immunization status of their 12–23 months old children.

Study design

A secondary data analysis using the Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey (2015–16) data, a cross-sectional, household-based, nationally representative survey conducted during 2015–2016.

Methods

We included 1669 pairs of mothers and their children in this analysis. We categorized the children into fully immunized and no/not fully immunized children and define a continuum of care (CoC) of the mother if women received antenatal care ≥ four times, delivered with skilled birth attendances, and received postnatal care within 48 h after delivery. We used the multivariable binary logistics regression using STATA version 15.1 with the survey command (svy) and reported the results by adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

The mother's CoC prevalence was 42.5%, and that of fully immunized children was 33.5%. However, only one-fifth of mothers and their children received the continuum of care services altogether. The children of mothers who received CoC were more likely to be fully vaccinated than those who did not (aOR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.21, 2.13, P < 0.001). The child's birth order, employment status, and wealth status of the households are independent predictors of the full immunization of children.

Conclusions

We concluded that receiving the CoC in mothers influenced their children's vaccination status. Hence, integrating maternal health programs and immunization programs is essential to achieving sustainable development goals in Myanmar.

Keywords: Childhood immunization, Continuum of care, Demographic and health survey, Myanmar

1. Introduction

Promoting health along the whole continuum from pregnancy to postnatal is crucial [1]. Nowadays, most maternal and child health programs plan and implement based on the concept of a continuum of care, which has been considered a conceptual framework to integrate reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) services. It is also a continuity of individual care program throughout the lifecycle of reproductive women (adolescence, pregnancy, childbirth, postnatal period, and childhood). Utilizing each level of the continuum of care determines utilization of the next level of care, including immunization status [2]. As of Myanmar 2019 data, 59% of reproductive women had attended four or more antenatal (ANC) visits, 60% had delivered with skilled birth attendances (SBA), and 71% of women had received postnatal care (PNC) within two days of giving birth [3].

Immunization prevents 2–3 million deaths annually, and measles mortality has decreased by 73%. Rates for diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT 3) coverage had risen to 86% in 2018 from 72% in 2000. However, about 19.4 million under-one children had not received the basic vaccinations, and about 13.5 million under-one children did not benefit from any vaccinations [4]. Expanded Program on Immunization factsheet 2019 revealed that diphtheria and pertussis cases were reduced with increasing coverage of the DPT vaccine from 1980 to 2018 in Myanmar. In recent years, measles cases from Myanmar dramatically rose from 122 cases in 2014 to 1330 cases in 2018 [5].

An efflux of measles outbreaks, a highlight of the importance of the immunization program in the South East Asia Region during 2017, reminded timely that hard-won gains can be easily lost even with well-established health systems [6]. Furthermore, Myanmar is still struggling with many challenges in the continuum of care (CoC) for reproductive women and the immunization program for their children. Many Myanmar studies assessed each component of the CoC of the mother and immunization status of the children separately [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Despite an extensive literature search, we found no study evaluating mothers' CoC and its effect on childhood immunization in Myanmar. Hence, we conducted this study to determine the association between the mothers' CoC and their children's immunization status.

2. Methods

We used the Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey (2015–16) (MDHS) data, a cross-sectional and nationally representative survey conducted in 15 States and Regions, including Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, during 2015–2016. The detailed methodology has been published elsewhere [11]. In brief, the survey used a two-stage stratified sampling method. Each state and region were stratified into urban and rural areas. Four hundred forty-two clusters (123 from urban areas and 319 from rural areas) were selected to represent 30 sampling strata from 14 states and regions and Nay Pyi Taw territory. The survey selected 30 households per cluster to get 13,260 households. A total of 12,885 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) from 12,500 households were included in this survey.

We included all women who had 12–23 months aged children for this analysis. The reason for choosing this population was that the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) collected postnatal check-up information only from mothers giving birth to their last child two years preceding the survey to minimize the recall bias. We excluded the children less than 12 months since DHS considered full immunization (receiving all basic vaccination) if the child received BCG, the first dose of measles, and three doses each of the pentavalent and polio vaccines at the age of 12 months. We first excluded 9,302 women who had no live birth five years preceding the survey from 12,885 women and then excluded 1,914 women who had no live birth two years preceding the survey to get 1,669 mothers and their 12–23 months old children for this analysis.

2.1. Variables

2.1.1. Dependent variable

We used the immunization status of the 12–23 months old children as a dependent variable. If the children received one dose of the BCG vaccine, three doses of the DPT vaccine, three doses of the Polio vaccine, and the first dose of the measles vaccine, we categorized them as fully immunized children. In contrast, if they did not receive or miss any of these vaccinations, we categorized them as no/not fully immunized.

2.1.2. Independent variable

We used the CoC of the mother as an independent variable. We recoded CoC based on three criteria, i.e., receiving at least four ANC visits, delivered with SBA (includes doctor, nurses, midwife, and lady health visitor), and taking PNC within 48 h after delivery. If a mother received all these services, we categorized them as received CoC; if not, we classified them as not received CoC.

2.1.3. Covariates

We used the child characteristics (gender and birth order), maternal characteristics (age, education, employment, women's empowerment, desirability of births for current pregnancy, accessibility to mass media and health facility), and household characteristics (types of residence, household wealth status, and geographical zones) as covariates.

We assessed women's empowerment based on decision-making ability regarding the respondent's health, large household purchases, and visits to family and relatives. We scored one if a woman decided by herself or jointly with others for each item and otherwise scored zero. Then, we summed the score and categorized it into three empowerment levels – no empowerment if the score was zero, some empowerment if the score was 1–2, and full empowerment if the score was three. We recoded the desirability of the last birth into a wanted and not wanted child.

We categorized a woman as having no access to mass media if she had no access to newspapers, radio, and television at least once a week. If she had access to any three media, we categorized it as partly accessible to mass media and fully accessible if she had access to all these media at least once a week. The women's accessibility to health facilities was also assessed based on four criteria: 1) getting permission to go for treatment, 2) getting money for treatment, 3) distance to a health facility, and 4) not wanting to go alone. We recoded a woman as having difficulty in access if she had a big problem with any of these criteria and otherwise as not having difficulty in access.

We categorized the types of residence into urban and rural and 15 states and regions into four geographical zones – hilly zone including Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Chin, and Shan; coastal zone including Tanintharyi, Mon, Rakhine; delta zone including Bago, Yangon, Ayeyarwaddy; and central zone including Sagaing, Magway, Mandalay, Naypyitaw. MDHS described wealth status in quintiles (poorest, poor, middle, rich, and richest). For this study, we categorized it into three groups: poor, including the poorest and poor wealth quintiles; middle for middle wealth quintile; and rich, including rich and richest wealth quintiles.

2.1.4. Statistical analysis

We used STATA software (version 15.1) and survey data analysis command (svy) with sampling weight for all analyses to account for the cluster survey design and missing responses. We reported the background characteristics of the study population using frequency tables and described CoC mothers' and children's immunization status prevalence by bar charts. Moreover, we also described the prevalence of overall CoC, i.e., the mother received ANC, delivery care, and PNC, and the child received full immunization. Using the Pearson chi-square test, we accessed the bivariate association between the dependent variable and covariates. We performed the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis to determine the association between the CoC of mothers and the immunization status of their children, adjusting the potential covariates. We included all variables whose P value was less than 0.2 in bivariate analysis in the initial model. Then we used the manual backward deletion method to get the final model. We tested the final model by Hosmer Lemeshow's goodness of fit test and checked the multicollinearity among covariates using the variance inflation factor. We reported the binary logistic regression analysis results using adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A P-value less than 0.05 was set as a statistical significance.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the study population. Among participants in the study, 32.6% are from the delta region, and 23.4% are from the hilly region. Nearly three-fourths of the participants (74.9%) are from rural area. Only a few participants cannot be accessible to health facilities (3.2%). As for maternal characteristics, maternal age at the time of first childbirth is within 20–29 years of age in half of the maternal population (50.2%). In terms of the education status of the mothers, although 31.8% of the population has a secondary education level, 15.8% have no education. See details in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of background characteristics of the study population.

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Place of Residence | ||

| Urban | 419 | 25.1 |

| Rural | 1250 | 74.9 |

| Sex of the Children | ||

| Male | 899 | 53.8 |

| Female | 770 | 46.2 |

| Birth Order of the Children | ||

| 1st birth order | 601 | 36.0 |

| 2nd & 3rd birth order | 726 | 43.5 |

| 4th & above birth order | 342 | 20.5 |

| Maternal age at the time of first childbirth | ||

| Less than 20 years | 443 | 26.5 |

| 20–29 years | 1063 | 63.7 |

| 30–39 years | 159 | 9.5 |

| 40–49 years | 4 | 0.3 |

| Highest Education Level of the mother | ||

| No Education | 264 | 15.8 |

| Primary Education | 730 | 43.8 |

| Secondary Education | 532 | 31.8 |

| Higher Education | 143 | 8.6 |

| Employment Status of the mother in the last 12 months | ||

| Currently Not Working | 870 | 52.1 |

| Currently Working | 799 | 47.9 |

| Empowerment Status of the mother | ||

| No Empowerment | 161 | 9.6 |

| Some Empowerment | 469 | 28.1 |

| Full Empowerment | 1039 | 62.3 |

| Media Use | ||

| Access none of the three media at least once a week | 311 | 18.6 |

| Access one of the three media at least once a week | 1290 | 77.3 |

| Access all three media at least once a week | 68 | 4.1 |

| Wealth Status of the Household | ||

| Poor | 810 | 48.5 |

| Middle | 286 | 17.2 |

| Rich | 573 | 34.3 |

| Access to a health facility | ||

| No difficulty in access to a health facility | 799 | 47.9 |

| Difficulty in access to a health facility | 870 | 52.1 |

| Desire for Children when became pregnant | ||

| Not Wanted the child | 88 | 5.3 |

| Wanted the child | 1581 | 94.7 |

| Total | 1669 | 100.0 |

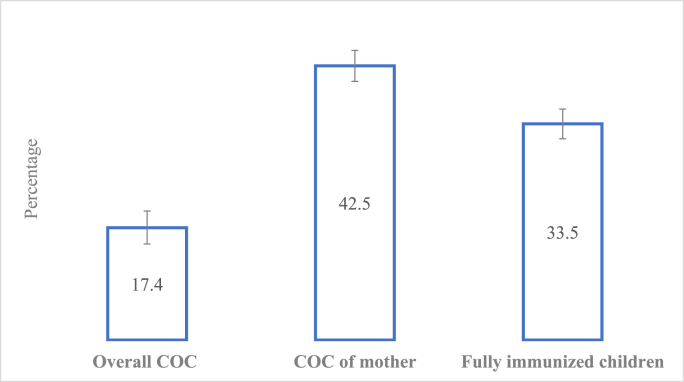

The overall prevalence of the CoC (both mother and children received a continuum of care services) was less than one-fifth of the study population (17.4%, 95% CI: 14.9%, 20.0%). The prevalence of CoC among mothers was 42.5% (95% CI: 40.1%, 44.9%), while that of fully immunized children was 33.5% (95% CI: 31.2%, 35.8%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The prevalence of overall COC, COC of mothers, and fully immunized children.

Table 2 shows the bivariate analysis results between the immunization status of the children and the background characteristics. The percentage of children fully immunized was significantly higher among mothers who received CoC than mothers who did not (40.9% vs. 28.1%). Moreover, household characteristics, i.e., residence, region, wealth status, accessibility to health facility; sex of the children; and mother's characteristics, i.e., education, employment, and media usage, were significant in bivariate analysis.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of immunization status of the children and independent variables.

| Variables | Fully Immunized |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | CI | N | |

| Continuum of Care of mothers | P < 0.001 | ||

| COC Absence | 28.1 | (24.8, 31.6) | 959 |

| COC Presence | 40.9 | (36.2, 45.7) | 710 |

| Place of Residence | P = 0.005 | ||

| Urban | 40.5 | (34.9, 46.4) | 419 |

| Rural | 31.2 | (27.9, 34.7) | 1,250 |

| Region of Residence | P = 0.035 | ||

| Hilly region | 30.3 | (24.8, 36.4) | 391 |

| Coastal region | 29.1 | (23.5, 35.3) | 228 |

| Delta region | 31.9 | (26.9, 37.4) | 545 |

| Central region | 39.8 | (34.2, 45.6) | 506 |

| Sex of the Children | P = 0.042 | ||

| Male | 36.1 | (32.3, 40.2) | 899 |

| Female | 30.5 | (26.6, 34.6) | 771 |

| Birth Order of the Children | P = 0.194 | ||

| 1st birth order | 31 | (26.8, 35.6) | 601 |

| 2nd & 3rd birth order | 36.2 | (32.1, 40.5) | 726 |

| 4th & above birth order | 32.2 | (26.6, 38.4) | 343 |

| Maternal age at the time of first childbirth | P = 0.485 | ||

| Less than 20 years | 31.7 | (27.1, 36.7) | 443 |

| 20–29 years | 33.5 | (30.0, 37.2) | 1,063 |

| 30–39 years | 38.7 | (30.0, 48.3) | 159 |

| 40–49 years | 30.3 | (8.0, 68.4) | 4 |

| Highest Education Level of the mother | P = 0.016 | ||

| No Education | 25.7 | (19.3, 33.5) | 264 |

| Primary Education | 34.4 | (30.4, 38.6) | 730 |

| Secondary Education | 33.3 | (29.1, 37.8) | 532 |

| Higher Education | 44.4 | (34.6, 54.6) | 143 |

| Employment Status of the mother in the last 12 months | P = 0.001 | ||

| Currently Not Working | 29.6 | (26.1, 33.2) | 870 |

| Currently Working | 37.9 | (33.8, 42.1) | 799 |

| Empowerment Status of the mother | P = 0.638 | ||

| No Empowerment | 30.7 | (23.0, 39.6) | 161 |

| Some Empowerment | 35.1 | (30.2, 40.4) | 469 |

| Full Empowerment | 33.2 | (29.8, 36.9) | 1,039 |

| Media Use | P = 0.005 | ||

| Access none of three media at least once a week | 23.6 | (17.9, 30.5) | 311 |

| Access one of three media at least once a week | 35.9 | (32.7, 39.1) | 1,290 |

| Access all three media at least once a week | 34.7 | (22.3, 49.7) | 68 |

| Wealth Status of the Household | P < 0.001 | ||

| Poor | 26.9 | (23.3, 30.9) | 810 |

| Middle | 37.6 | (31.4, 44.3) | 286 |

| Rich | 40.8 | (35.8, 46.0) | 573 |

| Access to a health facility | P = 0.009 | ||

| No difficulty in access to a health facility | 37.4 | (33.4, 41.5) | 799 |

| Difficulty in access to a health facility | 30 | (26.2, 34.2) | 870 |

| Desire for Children when became pregnant | P = 0.358 | ||

| Not Wanted the child | 39 | (28.0, 51.2) | 88 |

| Wanted the child | 33.2 | (30.2, 36.4) | 1,581 |

We performed the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis to assess the association between mothers' CoC and immunization status, adjusting the possible confounders. In multivariable analysis, we included the variables - the place of residence, region, gender of the children, birth order, educational and employment status of mothers, media usage, wealth status of households, and access to a health facility as confounders in Model 1. We selected these variables based on the criteria of a P value less than 0.2 in bivariate analysis. We built the final model based on the manual backward deletion method. We found that the children of mothers who received CoC are 1.6 times (95% CI: 1.21, 2.13) more likely to be fully vaccinated than mothers who did not receive CoC, accounting for the potential confounders. Moreover, childbirth order, the mother's working status, and household wealth status were independent predictors of children's immunization status. See details in Table 3.

Table 3.

The association between the children's immunization status and COC of mothers adjusting covariates.

| Variables | Model 1 |

Final Model |

|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Continuum of Care of mothers | ||

| COC Absence | 1 | 1 |

| COC Presence | 1.47** (1.11, 1.96) | 1.60** (1.21, 2.13) |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 1 | |

| Rural | 0.83 (0.60, 1.15) | |

| Region of the residence | ||

| Hilly region | 1 | |

| Coastal region | 1.05 (0.71, 1.54) | |

| Delta region | 0.96 (0.67, 1.36) | |

| Central region | 1.25 (0.87, 1.79) | |

| Gender of the children | ||

| Male | 1 | |

| Female | 0.80 (0.62, 1.03) | |

| Birth Order of the children | ||

| 1st birth order children | 1 | 1 |

| 2nd & 3rd birth order children | 1.35* (1.01, 1.80) | 1.42* (1.08, 1.89) |

| 4th & above birth order children | 1.44* (1.01, 2.07) | 1.44* (1.02, 2.03) |

| Highest Educational Level of the mother | ||

| No education | 1 | |

| Primary Education | 1.23 (0.82, 1.85) | |

| Secondary Education | 0.97 (0.62, 1.52) | |

| Higher Education | 1.20 (0.69, 2.09) | |

| Employment Status of the mothers | ||

| Currently Not Working | 1 | 1 |

| Currently Working | 1.46** (1.16, 1.85) | 1.46** (1.16, 1.84) |

| Media Use | ||

| Access none of three media at least once a week | 1 | |

| Access one of three media at least once a week | 1.43 (0.97, 2.10) | |

| Access all three media at least once a week | 1.16 (0.56, 2.42) | |

| Wealth Status of the Household | ||

| Poor | 1 | 1 |

| Middle | 1.40 (0.98, 2.00) | 1.55* (1.10, 2.18) |

| Rich | 1.44* (1.01, 2.07) | 1.68*** (1.25, 2.28) |

| Access to a health facility | ||

| No difficulty in access to a health facility | 1 | |

| Difficulty in access to a health facility | 0.85 (0.66, 1.11) | |

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

We conducted this study to assess the association between the CoC of mothers and the immunization status of their children. The study found a significant association between mothers' CoC and their children's immunization status. The receiving of CoC among mothers favors the completion of childhood immunization.

In our study, less than half of the study population had received the mothers' continuum of care, and it was not in an acceptable condition. However, it was higher than the findings of Nepal (26.7%) [12] and Indian studies (19%) [13]. This finding might be due to the differences in the study population and the study period being different. Both these studies used a similar methodology in assessing the receiving CoC. Both studies used women of reproductive age as the study population. Moreover, the Indian study considered the number of ANC and the components of ANC (the tetanus toxoid injection and iron-folic acid supplementation of the mothers) for the CoC of mothers using the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) conducted in 2015–16. However, the Nepal study determined the use of postpartum family planning as an outcome variable using Nepal Demographic and Health Survey Data (2011).

The full immunization status of the 12–23 months old children was only in nearly one-third of the children. It was lower than the study performed in the East District of Yangon Region (84.3%) from May 2017 to April 2018 [7]. But this study was conducted only in peri-urban townships of the Yangon Region. So, this study represented only for Yangon Region, but our findings represent nationally. The study timeline and population differences may be responsible for the inconsistency.

Our study found a significant association between mothers' CoC and their children's immunization status. The presence of the CoC in the mothers favored getting their children's full immunization status, similar to the study performed in India [13]. About three-fourths of the children from the mothers with CoC had received the full immunization status in the India study. In our research, less than half of the children from the mothers with CoC had received the full immunization status, but the finding was statistically significant. The service utilization in each step of maternal health care favored the subsequent service level utilization of the mothers to the immunization service utilization of the children [14,15].

Children from currently working mothers had more chance of getting fully immunization status than those from currently not working mothers, similar to the finding from the other studies [7,8,13,16]. The mother's employment status was an important factor in improving the immunization status of the children. Moreover, the household's wealth status favored the full immunization of the children. This finding was similar to the other studies [7,8,13,[16], [17], [18]]. Children from rich families have more opportunities to access health services than low-income families. Hence, improving the socioeconomic status of the households might alleviate the inequity in health access, thereby leading to the overall health development of the nation.

Since we conducted secondary data analysis, we could not assess the quality of maternal health services. However, we have a variable of access to a health facility in MDHS. Hence, we used this variable as a proxy indicator for the accessibility of CoC and adjusted it in data analysis. In our study, accessibility to health services was significant only in bivariate analysis. The favorable condition for the health services accessibility may contribute to receiving the CoC of the mothers leading to the next step to the immunization status of the children. The promising initial perception of the health care service utilization of the mothers might affect the maternal health services as the continuum, thereby favoring their children's immunization status. Mothers with CoC may also have a good awareness of the immunization services for their children. They have frequent contact with the health care personnel, and more health information about the immunization benefits may receive from the health personnel compared with the mothers without the CoC, leading to the full immunization status of the children. These results suggest the importance of maternal and child health care services in implementing the immunization program mainly to serve as the continuum of care.

Although the CoC of the mothers was nearly half of the study population and the full immunization status of the children was about one-third of the study population, the overall prevalence of the continuum of care was only less than one-fifth of the study population. This finding pointed out the lack of integration between maternal and child health services at the operational level in Myanmar. Therefore, program implementers must emphasize integrating maternal health and immunization services as the continuum of care to reach sustainable development goals.

Our study has some limitations. Since we conducted the study using the data from 2015 to 16, the prevalence we estimated may not accurately represent the current situation. Due to the data limitation in MDHS (2015–16), some variables from the literature review could not be included in the analysis to adjust the confounding and might affect the study findings. However, the study's finding that receiving CoC among mothers favors their children's immunization status supported that the continuum of care concept to improve mother and child health status is not avoidable. Since we used cross-sectional data, the association found in our study might not be causal.

Hence, policymakers and implementers should emphasize integrating maternal and child health services at the central and operational levels during planning and implementation. Further research should be carried out using a mixed-method approach to explore the barriers, challenges, and influencing factors for integrating the health services at the operational level to achieve the continuum of care for both mothers and children.

Ethical consideration

We conducted a secondary data analysis using the MDHS data from a publicly available website. The MDHS protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee on Medical Research, including Human Subjects in the Department of Medical Research, Ministry of Health and Sports, and by the ICF Institutional Review Board, respectively. Moreover, we obtained Ethical approval for this study from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Public Health (UPH-IRB (2020/MPH/12)).

Data statement

We used the data from the publicly available Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) website (https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/). You can get access to MDHS data with a reasonable request.

Contributors

PP, ATK, and KSM conceptualized the study. PP and KSM analyzed and interpreted the data. PP drafted the manuscript. ATK, ASM, and KSM revised it critically. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

I want to give special thanks to the ICF for granting permission to use the MDHS data set for this study. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude to everyone who helped and guided me in this current study.

References

- 1.UNFPA. Maternal health [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 24]. Available from: https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/node/15199.

- 2.Hill J., Hoyt J., van Eijk A.M., D'Mello-Guyett L., ter Kuile F.O., Steketee R., et al. Factors affecting the delivery, access, and use of interventions to prevent malaria in pregnancy in sub-saharan africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med [Internet. 2013 Jul 23;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001488. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001488 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNICEF Myanmar country profile [internet] https://data.unicef.org/country/mmr/ [cited 2022 Sep 25]. Available from:

- 4.UNICEF Immunization [internet] https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/immunization/ [cited 2022 Sep 25]. Available from:

- 5.WHO Measles supplementary immunization [internet] 2019. http://www.searo.who.int/myanmar [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from:

- 6.WHO Immunization today and in the next decade [Internet] 2018. http://apps.who.int/ [cited 2020 May 31]. Available from:

- 7.Tin-Thitsar-Lwin . Yangon Region; East District: 2018. Gaps of Immunization Coverage Among 12-23 Months Old Children in Four Peri-Urban Townships. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nozaki I., Hachiya M., Kitamura T. Factors influencing basic vaccination coverage in Myanmar: secondary analysis of 2015 Myanmar demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2019 Feb 28;19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6548-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6394082/ [cited 2020 May 29]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okawa S., Win H.H., Leslie H.H., Nanishi K., Shibanuma A., Aye P.P., et al. Quality gap in maternal and newborn healthcare: a cross-sectional study in Myanmar. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019 Mar 1;4(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001078. https://gh.bmj.com/content/4/2/e001078 [Internet]. Available from: [cited 2022 Feb 10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mon A.S., Phyu M.K., Thinkhamrop W., Thinkhamrop B. Utilization of full postnatal care services among rural Myanmar women and its determinants: a cross-sectional study. F1000Research. 2018 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15561.1. https://f1000research.com/articles/7-1167 [Internet]. 2018 Aug 1 [cited 2022 Feb 10];7:1167. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) and ICF . Nay Pyi Taw; Myanmar, and Rockville, Maryland USA: 2017. Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. Ministry of Health and Sports and ICF. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babu R., Komal K., Dulal P., Pandey K.P. vol. 133. 2017. (Continuum of Maternal Health Care and the Use of Postpartum Family Planning in Nepal). DHS Working Papers No. 133. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Usman M., Anand E., Siddiqui L., Unisa S. Continuum of maternal health care services and its impact on child immunization in India: an application of the propensity score matching approach. J Biosoc Sci. 2020;53(5):643–662. doi: 10.1017/S0021932020000450. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/continuum-of-maternal-health-care-services-and-its-impact-on-child-immunization-in-india-an-application-of-the-propensity-score-matching-approach/0DBCFFA60CD13CA0CC4992E682E9D3F8 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 23]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Graft-Johnson J., Kerber K., Tinker A., Otchere S., Narayanan I., Shoo R., et al. 2020. Opportunities for Africa's Newborns 23 the Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Continuum of Care. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owili P.O., Muga M.A., Chou Y.-J., Hsu Y.-H.E., Huang N., Chien L.-Y. Associations in the continuum of care for maternal, newborn and child health: a population-based study of 12 sub-Saharan Africa countries. BMC Publ. Health. 2016 Dec 17;16(1):414. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3075-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4869316/ [Internet]. Available from: [cited 2020 May 30] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bbaale E. Factors influencing childhood immunization in Uganda. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2013;31(1):118–127. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v31i1.14756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdou M., Mbengue S., Sarr M., Faye A., Badiane O., Bintou F., et al. vols. 1–9. 2017. (Determinants of Complete Immunization Among Senegalese Children Aged 12 – 23 Months : Evidence from the Demographic and Health Survey). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew J.L. Inequity in childhood immunization in India. Syst. Rev. 2012;49(3):203–223. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]