Abstract

Nanocrystals (NCs), a colloidal dispersion system formulated with stabilizers, have attracted widespread interest due to their ability to effectively improve the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. The stabilizer plays a key role because it can affect the physical stability and even the oral bioavailability of NCs. However, how stabilizers affect the bioavailability of NCs remains unknown. In this study, F68, F127, HPMC, and PVP were each used as a stabilizer to formulate naringenin NCs. The NCs formulated with PVP exhibited excellent release behaviors, cellular uptake, permeability, oral bioavailability, and anti-inflammatory effects. The underlying mechanism is that PVP effectively inhibits the formation of naringenin dimer, which in turn improves the physical stability of the supersaturated solution generated when NC is dissolved. This finding provides insights into the effects of stabilizers on the in vivo performances of NCs and supplies valuable knowledge for the development of poorly water-soluble drugs.

Keywords: Nanocrystals, Stabilizers, Bioavailability, Supersaturation maintenance, Dimer

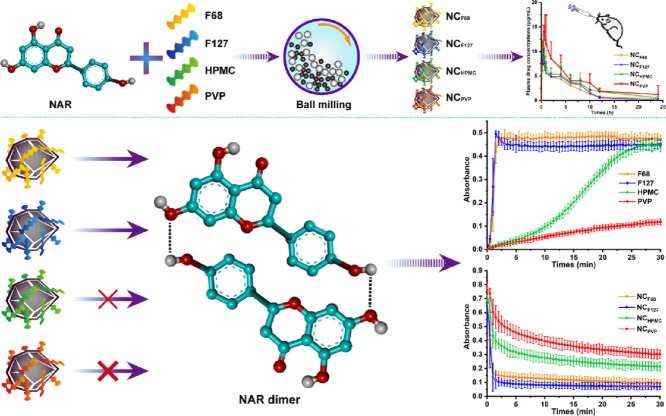

Graphical abstract

Schematic illustration Naringenin nanocrystals formulated with PVP exhibited the best oral bioavailability, because the strong intermolecular interaction between naringenin and PVP prevent the dimerization of naringenin, delay the formation of crystal nuclei and inhibit crystallization.

1. Introduction

Oral administration is one of the most common routes because of its good patient compliance [1]. Regrettably, more than 90% of new active pharmaceutical ingredients are poorly water-soluble [2]. After oral administration, only a small amount of the drug is absorbed into the systemic circulation due to its poor water solubility and low dissolution rate. To solve these problems, several nanotechnologies had been exploited, such as nanoparticles [3], nanoliposomes [4], nanoemulsions [5], nanostructured lipid carriers [6], and nanocrystals (NCs) [7]. Especially, the NCs show unique advantages because of their high drug loading and easy industrialization [8].

To further improve oral bioavailability, critical quality attributes of NCs, such as particle sizes and shapes, were investigated. For example, NCs with smaller particle sizes have faster dissolution rates and greater oral bioavailability than larger NCs [2]. In another case, rod-shaped NCs exhibit faster mucus penetration, stronger transepithelial transport, and higher bioavailability than spherical and platelet-shaped NCs [9]. In addition to these properties, the composition of the NCs is also a key attribute. It has been reported that the choice of a stabilizer is critical in improving the oral bioavailability of the NCs [10]. More importantly, the stabilizers have more pronounced effects on oral bioavailability than the particle sizes [10]. Although the importance of stabilizers has been recognized, few studies have attempted to explore the potential mechanisms. How the stabilizer affects the bioavailability of the NCs is still unknown.

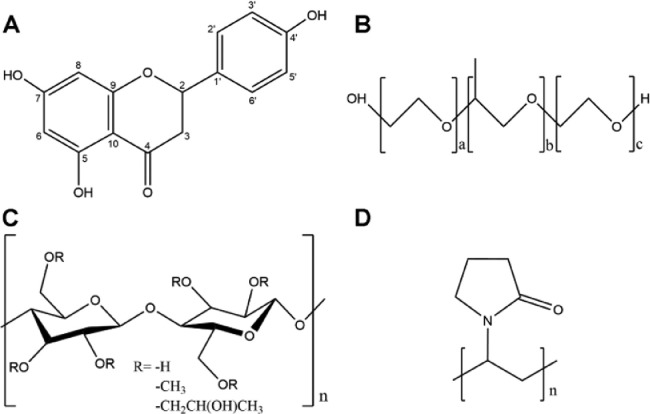

In this study, naringenin (NAR), a water-insoluble substance, was selected as a model drug (Fig. 1). Poloxamer 188 (F68), poloxamer 407 (F127), hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) were each used to formulate NAR NCs as NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP, respectively. The physicochemical properties of NAR NCs were first studied. Dissolution and cell experiments were then performed to investigate the in vitro behaviors of different NCs. Next, pharmacokinetic behaviors and anti-inflammatory effects in rats were investigated to study the in vivo performances of the NCs. Finally, supersaturation maintenance experiments and molecular docking were carried out to explore the mechanisms responsible for the in vitro and in vivo performances of NCs.

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of (A) NAR, (B) F68 and F127, (C) HPMC, and (D) PVP.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

NAR was purchased from Wuhan Yuancheng Gongchuang Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). HPMC was provided by Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). F68, F127, and PVP were supplied by BASF Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Lecithin was purchased from AVT (Shanghai) Pharmaceutical Tech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The Caco-2 cell line and RAW 264.7 cell line were supplied by the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for TNF-α and IL-6 were purchased from ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). A nitric oxide (NO) kit was supplied by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. The preparation of NAR NCs

The NAR NCs were prepared by wet milling. First, NAR (1 g) was suspended in 10 ml of stabilizer solution (10 mg/ml). The suspension was then transferred into a milling bowl filled with zirconium oxide beads (⌀0.5 mm) and grounded using a PM planetary ball mill (Nanjing Chishun Science and Technology Co., Ltd., China). The rotation power was adjusted to 30 Hz with 5 min grinding and 3 min pause for each circulation. The cycle time was determined according to particle sizes and polydispersity indexes (PDIs).

2.3. The characterization of NAR NCs

2.3.1. Particle sizes, polydispersity indexes, and zeta potentials

The particle sizes, PDIs, and zeta potentials of NAR NCs were determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). All samples were diluted 1000-fold with pure water and measured in triplicate.

2.3.2. Transmission electron microscope

The morphology of the NCs was observed using an HT-7700 instrument (Hitachi, Japan). The NAR NCs were diluted to a drug concentration of 0.1 mg/ml, dropped onto copper grids with 200-mesh carbon membranes (Beijing Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co., Ltd., China), and dried at room temperature.

2.3.3. Differential scanning calorimetry

To characterize the crystallinity, differential scanning calorimetry analysis was performed using a DSC 250 instrument (TA Instruments, USA). The sample (about 5 mg) was sealed in a standard aluminum pan and heated up at a linear heating rate of 10 °C/min over the temperature range of 40–280 °C in an atmosphere of nitrogen.

2.3.4. Powder X-ray diffraction

To further determine the crystalline state, the powder X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out using an X'pert Pro-MPD X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical B.V., Netherlands). The scanning speed was 5°/min over a 2θ range of 5°−50° and the scanning increment was 0.02°

2.4. Dissolution behaviors

Before oral absorption, a drug has to be dissolved in the gastrointestinal tract [11]. Thus, the in vitro dissolution behaviors of NAR NCs were investigated in simulated intestinal fluid using a ZRS-8 G dissolution apparatus (Tianjin Tianda Tianfa Technology Co., Ltd., China). Briefly, NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP (equivalent to 90 mg of NAR) were each placed in 900 ml of the medium at 37 °C. The paddle rotation speed was set to 50 rpm. At the scheduled time points (5, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min), 2 ml medium was withdrawn, and the water was immediately replenished. After filtration and dilution, the concentration of NAR was measured at 289 nm using a UV1102 II ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Shanghai Techcomp Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China).

2.5. Cell studies

2.5.1. Cell culture

Caco-2 cells and Raw 264.7 cells were both grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Dalian Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 supply.

2.5.2. Cellular uptake

To study the cellular uptake of NAR NCs, Caco-2 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well and further cultured for 14 d. On the 15th d, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with 50 µg/ml of NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP, respectively. After 15 min of incubation, the uptake process was stopped and the attached NAR was completely removed by washing the cells 3 times with PBS. Next, the cells were collected and disrupted using a SCIENTZ-IID ultrasonic homogenizer (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

To detect the total content of NAR, 100 µl of samples were treated with β-glucuronidase (20 µl) at 37 °C for 2 h. After incubation, methanol (300 µl) was added and vortexed for 3 min to precipitate proteins. The mixtures were then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was analyzed using the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described in Supplementary materials. The total protein was quantified using a BCA assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., China).

2.5.3. Cell permeability

For cell permeability studies, cell culture inserts 724,001 (NEST Biotechnology, China) were used. In brief, Caco-2 cells were seeded on the inserts (2 × 104 cells/well). On the 21st d, NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP (equivalent to 50 µg NAR) were added to the upper chamber, respectively. The samples (100 µl) were withdrawn from the basolateral at various time intervals (5, 15, 30 and 60 min) and replenished with fresh medium. The samples were treated according to the cellular uptake experiment and analyzed using the HPLC described in Supplementary materials. The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) values were calculated using Eq. 1:

| Papp = dQ/dt × 1/(C0 × A) | (1) |

where dQ/dt is the flux of NAR (µg/s); C0 is the initial concentration in the upper chamber (µg/ml); A is the filter membrane area (cm2).

2.5.4. In vitro anti-inflammation activity

To investigate the in vitro anti-inflammation activity of the NAR NCs, Caco-2 cells were seeded on cell culture inserts as described in 2.5.3. After culturing for 21 d, Raw 264.7 cells were seeded in lower compartments (2 × 105 cells/well) and cultured for 12 h. NAR NCs (equivalent to 50 µg NAR) and LPS (0.5 µg/ml) were then added to the upper chamber and basolateral for 24 h incubation, respectively. The samples in the basolateral compartment were subsequently collected, and the concentration of TNF-α, IL-6, and NO was determined by kits. Next, Raw 264.7 cells were washed thrice with PBS and incubated with DCFH-DA (10 µM) for 30 min. After washing, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) were observed using an IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6. Animal studies

All animal experiments were performed according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [12] and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University.

2.6.1. In vivo pharmacokinetics

To investigate the in vivo pharmacokinetic behavior of NCs, rats were randomly divided into 4 groups (NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP groups) and administered by gavage at a dose of 50 mg/kg. Blood samples were collected and immediately centrifuged at 10 000 g for 3 min, at predetermined time intervals (0.083, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h).

To detect the total content of NAR, β-glucuronidase (50 µl) was added to 100 µl of blood samples and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The samples were then mixed with 50 µg/ml of apigenin (20 µl), 100 µl of methanol-water (1:1, v/v) solution, and 3 ml ethyl acetate. Then, the mixtures were vortexed for 3 min and centrifuged at 3000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream. Next, 100 µl of methanol was added to reconstitute the residues and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was analyzed using the HPLC as described in Supplementary materials.

2.6.2. In vivo anti-inflammation activity

Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model in rats was established as previously reported [13]. Bovine type II collagen and incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Washington DC, USA) were 1:1 (v/v) mixed and emulsified using a T18 electronic homogenizer (IKA, Germany). Two hundred microliters of the emulsion were injected into the tail base of rats for the first immunization. After 7 d, 0.1 ml of the emulsion was injected for booster immunization. On d 21, the CIA rats were divided into 5 groups, and each group was orally administered PBS, NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, or NCPVP every d. The dose of NAR was 50 mg/kg. Rats not treated with the emulsion and NAR were used as blank controls. The hind paw thickness and arthritis scores were recorded every three d for 45 d

2.7. The maintenance of supersaturated solutions

To understand the potential mechanism for stabilizers in the oral bioavailability improvement of NCs, the supersaturated stability during dissolution was studied. To obtain a supersaturated solution, 20 µl of the NAR NCs (100 mg/ml) were added to 50 ml of water which was stirred at 200 rpm. The ultraviolet absorption of the solution was simultaneously detected at both 360 and 500 nm using a USB2000+ fiber optic spectrometer (Ocean Optical, USA). The ultraviolet absorption of free NAR in the solution was calculated using Eq. 2 [14]:

| A = A360 nm - E500 nm | (2) |

where A360 nm represented the absorbance of the NAR at 360 nm. E500 nm represented the extinction value at 500 nm.

The nucleation is the first step for desaturation, and the inhibition of nucleation is critical to the stability of the supersaturated solution. Therefore, the ability of the stabilizer to inhibit nucleation was investigated using the solvent-shift method. In brief, 525 µl of the NAR solution (18.2 mg/ml, methanol) was slowly added to 20 µg/ml of the stabilizer aqueous solution (F68, F127, HPMC or PVP). The formation of the nucleus was monitored by detecting ultraviolet absorption at 500 nm using the USB2000+ fiber optic spectrometer (Ocean Optical, USA).

2.8. Intermolecular hydrogen bonding for supersaturation stability

Hydrogen bonding between the drug and the stabilizer is critical for the stability of supersaturated solutions [15]. Therefore, the NAR-stabilizer hydrogen bonds were investigated by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). Deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide was used as the solvent and 1H NMR was analyzed using a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometer (Bruker Ltd., Switzerland).

The hydrogen bonding between NAR and different stabilizers in an aqueous solution was further investigated using molecular docking techniques. Energy minimization and structure optimization for the chemical structures of NAR and stabilizers were firstly performed using the Sybyl 6.9.1 software. The interaction between NAR and the stabilizer was then simulated using the AutoDock 4.0 software. Finally, the results were analyzed using the Pymol 2.4 software.

2.9. Self-association measurements to test the formation of dimers

To further confirm the formation of NAR dimers, self-association studies were performed by measuring ultraviolet absorption over the concentration range of 0–100 µg/ml. In brief, appropriate amounts of the NAR ethanol solution (50 mg/ml) were slowly added to water, stabilizer aqueous solution (F68, F127, HPMC or PVP, 10 µg/ml), or ethanol solution. And the absorbance of the resultant solutions was recorded using a spectrophotometer at 350 nm. Deviation from the Beer-Lambert law with increasing concentration was positive for the formation of dimers [16].

2.10. Statistical analysis

The differences between the two groups were evaluated for statistical significance using a two-tailed unpaired Students’ t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The preparation of NAR NCs

In this study, four NAR NCs were formulated with F68, F127, HPMC and PVP using the wet-milling method. To understand the stabilizer effects, the same-sized NCs were prepared by adjusting the milling time, because the particle size is a critical quality attribute of NCs [2]. The particle sizes of all NCs decreased with increasing milling times (Fig. S1). However, prolonged milling was detrimental to the monodispersity of NCs, and an increase in PDIs was observed with the prolongation of times. Therefore, NCF68, NCF127, and NCPVP were prepared by milling for 100 min, and NCHPMC was formulated by 125 min milling. The four NAR NCs finally prepared had similar particle sizes of approximately 315 nm, PDIs of 0.12, and zeta potentials of −10.6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The particle sizes, PDIs, and zeta potentials of NAR NCs (data are mean ± SD, n = 3).

| NCF68 | NCF127 | NCHPMC | NCPVP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle sizes (nm) | 323.8 ± 19.9 | 317.3 ± 7.74 | 309.8 ± 9.24 | 318.0 ± 6.53 |

| PDIs | 0.131 ± 0.065 | 0.102 ± 0.057 | 0.126 ± 0.022 | 0.130 ± 0.011 |

| Zeta potentials | −12.6 ± 1.06 | −10.1 ± 0.110 | −8.48 ± 0.520 | −11.4 ± 0.577 |

3.2. The characterization of NAR NCs

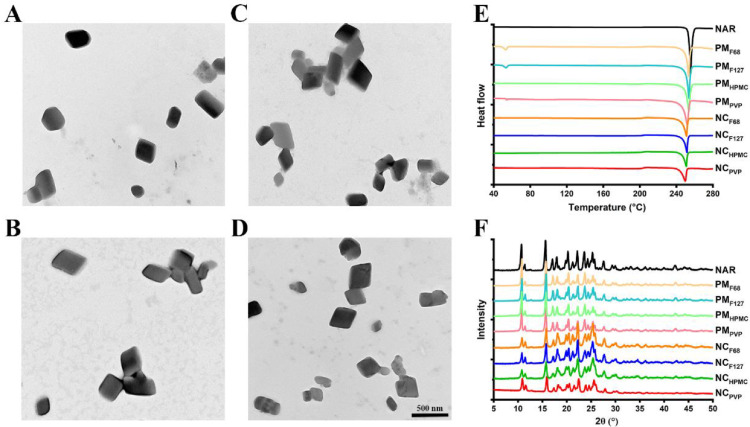

3.2.1. Morphology

It has been reported that the morphology of NCs affects their physicochemical and biological properties [9]. Therefore, the shape of the freshly prepared NAR NCs was observed. As shown in Fig. 2A-2D, the four NAR NCs were all blocky-shaped, indicating that the type of stabilizer did not affect the morphology of the NAR NCs. It also ensured that the shape of the NCs will not affect the studies of stabilizer effects.

Fig. 2.

In vitro characterizations of NAR NCs. Representative transmission electron microscopy images of (A) NCF68, (B) NCF127, (C) NCHPMC, and (D) NCPVP. The scale bar denotes 500 nm. (E) Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms and (F) powder X-ray diffraction diffractograms of NAR, PMF68, PMF127, PMHPMC, PMPVP, NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP. The PMF68, PMF127, PMHPMC, and PMPVP represent the physical mixture of NAR with F68, F127, HPMC, and PVP, respectively.

3.2.2. Crystallinity

The crystalline state of a drug may affect its dissolution behavior [17], therefore, it is necessary to determine the crystalline state of the prepared NAR NCs. The differential scanning calorimetry thermogram showed a significant endotherm at 255 °C for the crude NAR (Fig. 2E). After milling, the position of the endotherm did not change significantly, indicating that the crystalline state of the four NAR NCs was consistent with that of crude NAR. Powder X-ray diffraction analysis was performed to further confirm the crystalline state (Fig. 2F). All NAR NCs exhibited characteristic diffraction peaks similar to those of NAR at the 2θ angles of 10.68°, 15.64°, 17.04°, 17.96°, 20.24°, 22.18°, 23.62°, 24.30°, 25.28° and 27.60° The results showed that the crystalline state of NAR did not change after milling.

In summary, the four NAR NCs prepared in this study shared similar particle sizes, morphology, and crystallinity. The studies of stabilizer effects in the in vitro and in vivo performances of NCs were not interfered with by these properties.

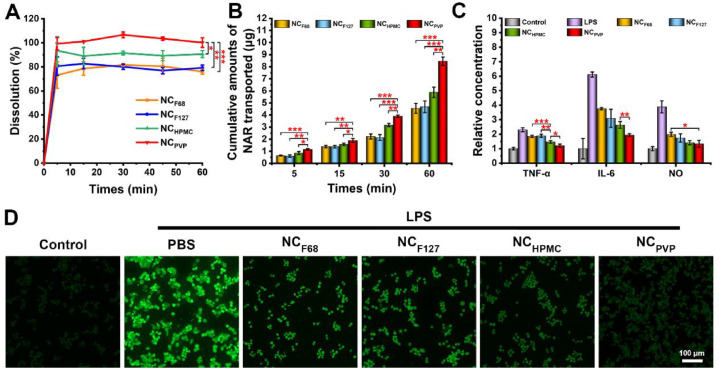

3.3. In vitro dissolution performances

After oral administration, the NCs will first be dissolved and then absorbed by the enterocytes in the molecular state [18]. Therefore, the dissolution process is a prerequisite step for oral absorption. As shown in Fig. 3A, NCF68 and NCF127 had similar dissolution profiles, releasing 76.03% and 79.21% of the NAR at 60 min, respectively. Although NCHPMC showed higher dissolution (approximately 90% at 60 min) than NCF68 and NCF127, it was significantly lower than NCPVP (P < 0.05). The NCPVP released almost 100% NAR at 60 min.

Fig. 3.

(A) Dissolution profiles of NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP in fasted state simulated intestinal fluid. (B) Cumulative transport of NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, and NCPVP across Caco-2 cell monolayers. (C) The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and NO in the supernatant after treatment with different NAR NCs. (D) Fluorescence images of intracellular ROS. Bar: 100 µm. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

3.4. Cellular uptake and permeability

The cellular uptake behaviors of NCs were assessed, and the results are shown in Fig. S2. The level of NAR in NCPVP group was 3001.38 ng/mg protein, which was 1.45-fold, 1.53-fold, and 1.53-fold higher than those of NCHPMC (P < 0.05), NCF68 (P < 0.05), and NCF127 (P < 0.05). In addition, the cell permeability of NAR NCs was investigated using a Caco-2 cell monolayer. As shown in Fig. 3B, all formulations showed time-dependent transport. Notably, the cumulative transport of NCPVP was significantly higher than that of NCF68, NCF127, and NCHPMC at all time points. To further compare the cell permeability of different NAR NCs, the Papp values were calculated (Fig. S3). The Papp values of NCPVP (17.18 ± 0.91 × 10−6 cm/s) were much higher than NCHPMC (11.72 ± 1.16 × 10−6 cm/s, P < 0.05), NCF68 (8.91 ± 0.87 × 10−6 cm/s, P < 0.05), and NCF127 (9.27 ± 1.29 × 10−6 cm/s, P < 0.05). This indicated that NCPVP had superior cell permeability.

3.5. In vitro anti-inflammation activity

To investigate whether stabilizers affect the in vitro anti-inflammatory efficacy of NAR NCs, an inflammation model was established based on Caco-2 and Raw 264.7 cells. As shown in Fig. 3C-3D and Fig. S4, NCF68 and NCF127 had similar anti-inflammatory effects, which were consistent with the cell transport results. For NCHPMC, a significant reduction in TNF-α (⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001 versus NCF68 and ⁎⁎P < 0.01 versus NCF127) and intracellular ROS levels (⁎⁎P < 0.01 versus NCF68 and ⁎⁎⁎⁎P < 0.0001 versus NCF127) was observed, indicating that NCHPMC has a stronger anti-inflammatory effect than NCF68 and NCF127. However, there were no significant differences in IL-6 and NO levels between NCHPMC and NCF127. In contrast, NCPVP exhibited better anti-inflammatory capacity than NCHPMC, as evidenced by lower levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and ROS.

3.6. In vivo pharmacokinetics

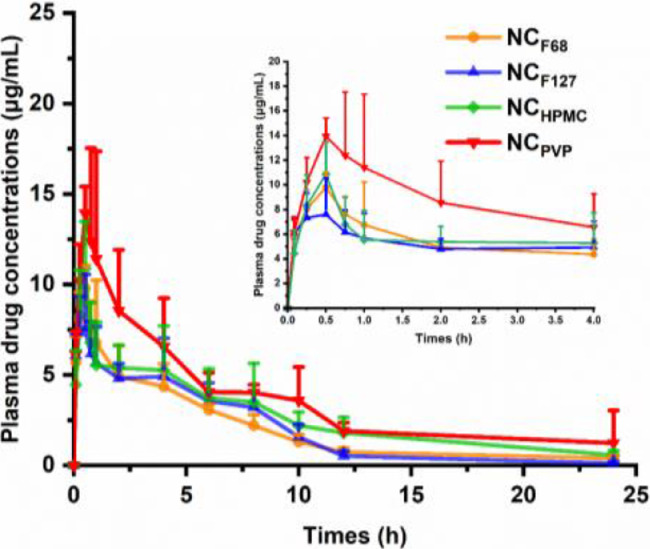

In vivo pharmacokinetic experiments were conducted to investigate the oral bioavailability of NAR NCs formulated with different stabilizers. The results are presented in Fig. 4 and Table 2. The NCF68 group exhibited similar AUC0–24 h values (51.1 ± 6.83 µg·h/ml) to the NCF127 group (47.2 ± 7.50 µg·h/ml), which was consistent with the results of the dissolution and cell experiments. Although the AUC0–24 h of the NCHPMC group was increased compared to the NCF68 and NCF127 groups, it was still significantly lower than that of the NCPVP group (P < 0.05). Similar results were observed in Cmax. The Cmax of NCPVP (15.45 ± 3.77 µg/ml) was 1.44, 1.86, and 1.28 times higher than that of NCF68, NCF127, and NCHPMC, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Plasma drug concentrations of NAR after oral administration of the NCs at a single dose of 50 mg/kg to rats (data are mean ± SD, n = 5).

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of NAR after oral administration of the NCs at a single dose of 50 mg/kg to rats (data are mean ± SD, n = 5).

| Pharmacokinetic parameters | NCF68 | NCF127 | NCHPMC | NCPVP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (µg/ml) | 10.75 ± 1.10* | 8.32 ± 1.89** | 12.08 ± 1.05 | 15.45 ± 3.77 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.60 ± 0.22 | 0.50 ± 0.31 | 0.55 ± 0.11 | 0.55 ± 0.11 |

| T1/2 (h) | 4.80 ± 2.06 | 4.00 ± 1.86 | 5.19 ± 0.92 | 4.97 ± 0.70 |

| AUC0–24 h (µg·h/ml) | 47.6 ± 6.62** | 47.2 ± 7.50** | 63.57 ± 15.37* | 86.71 ± 15.91 |

*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus NCPVP as the control.

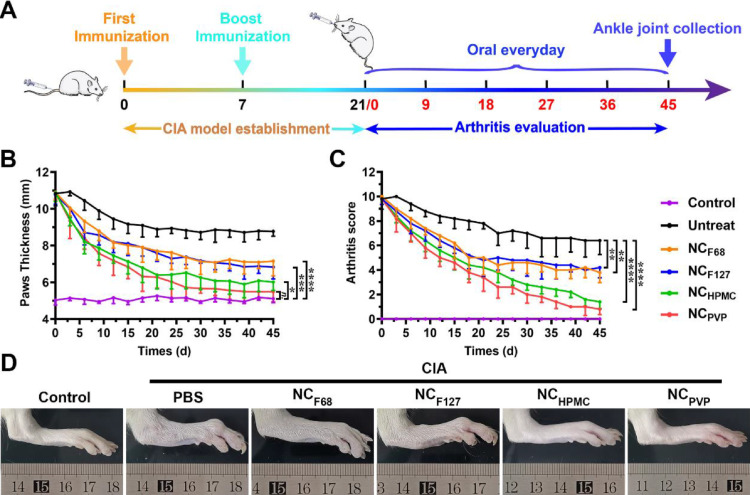

3.7. In vivo anti-inflammatory efficacy

The in vivo anti-inflammatory efficacy of different NAR NCs was investigated by a CIA rat model. The experimental scheme is shown in Fig. 5A, and the results are shown in Fig. 5B-D. The NCF68 and NCF127 groups showed similar therapeutic effects, i.e. the paw thickness decreased after treatment, but it was significantly higher than that of healthy rats (P< 0.001). Although NCHPMC was more efficacious than NCF68 and NCF127, marked paw swelling was still observed compared to healthy rats. The NCPVP had the best therapeutic effects, and there was no statistical difference in paw thickness compared with the control group after the treatment for 39 d. The results were further supported by the arthritis scores. The NCPVP group had the lowest arthritis score of all treatment groups and was significantly lower than the untreated group (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

The therapeutic effects of NAR NCs in the CIA rat model. (A) Schematic diagram of the establishment and treatment process of the CIA rat model. (B) Hind paw thickness and (C) arthritis scores of rats until d 45 were recorded. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. (D) Photographs of rat hind paw following treatment with PBS, NCF68, NCF127, NCHPMC, or NCPVP. Healthy, untreated animals served as the control.

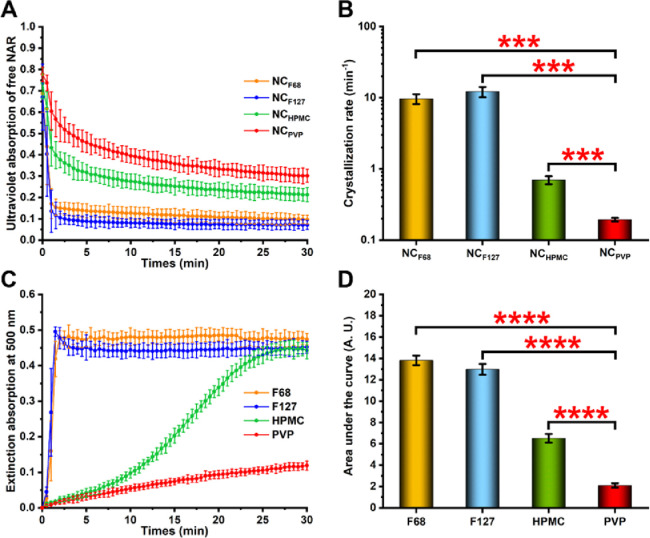

3.8. The maintenance of supersaturated solutions

After administration, NCs dissolve rapidly in the gastrointestinal fluid and produce supersaturated solutions [19]. The stability of the supersaturated solutions is an important factor related to the oral bioavailability of the drug since NCs are mainly absorbed in the molecular state [18]. Therefore, the supersaturation maintenance was examined to explore potential reasons for stabilizers’ effects on the in vitro and in vivo performances of NCs. As shown in Fig. 6A, the absorbance values of all NAR NCs rapidly decreased, possibly due to rapid de-supersaturation caused by the high drug loading. However, among the four NAR NCs, the NCPVP showed the slowest absorbance decrease, and it still had the highest absorbance after 30 min, indicating that PVP had the strongest ability to maintain supersaturation. Despite the absorbance values of NCHPMC being lower than those of NCPVP, they were higher than those of NCF68 and NCF127, suggesting that the HPMC can better sustain supersaturation than F68 and F127. To further quantify the supersaturation stability for different systems, the crystallization rate of NAR was calculated using the exponential decay model (Eq. 3 below), and the results are shown in Fig. 6B. The crystallization rate of NAR in the NCPVP group was 0.19 ± 0.01 min−1, which was significantly lower (P < 0.001) than that of NCF68 (9.67 ± 1.53 min−1), NCF127 (12.17 ± 2.02 min−1), and NCHPMC (0.70 ± 0.09 min−1).

| C = C0 − A(1 − e−Bt) | (3) |

where C is the concentration of NAR (µg/ml); C0 is the initial concentration of NAR (µg/ml); A and B represent the crystallization concentration (µg/ml) and crystallization rate (min−1), respectively; t is the time (min).

Fig. 6.

The maintenance of supersaturated solutions. (A) Ultraviolet absorption curve of free NAR after NCs were dissolved in water. (B) The crystallization rate of NAR after NCs dissolved in water. (C) Extinction absorption curves of NAR in different stabilizer solutions. (D) The area under the curve was calculated based on the data of extinction intensity at 500 nm. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 and **** P < 0.0001.

The supersaturation maintenance includes two aspects: prevention of the formation of crystal nuclei and inhibition of crystal growth. It has been reported that the reduction of nucleation, rather than the inhibition of crystal growth after nucleation, is the main factor for physical stability in stabilizer-mediated supersaturated systems [20]. Therefore, the nucleation inhibition effect of different stabilizers was compared using the solvent-shift method. The nucleus formation was detected by recording the extinction intensity at 500 nm (Fig. 6C) and the area under the curve was calculated (Fig. 6D). As it was shown, NAR rapidly nucleated after dropwise addition to F68 and F127 solutions, indicating that these two stabilizers had a weak effect on inhibiting the formation of nuclei. When HPMC was used as a stabilizer, NAR slowly nucleated within 5 min, but then a large amount of NAR nucleated and precipitated from the solution. However, the slowest nucleation rate of NAR in PVP solution was observed, indicating that PVP had the strongest ability to inhibit nucleus formation.

3.9. Intermolecular hydrogen bonding

The hydrogen bonding between NAR and different stabilizers may contribute to the nucleation inhibition effects. To test this hypothesis, a 1H NMR analysis was carried out (Fig. S5). The peaks at approximately 9.6 and 10.7 ppm were attributed to the H in the OH groups at the 4′ and 7 positions of NAR, respectively. The peaks became smoother after the addition of stabilizers, indicating the formation of hydrogen bonds [21]. The strongest hydrogen bonds formed between NAR and PVP were demonstrated from its smoothest peak.

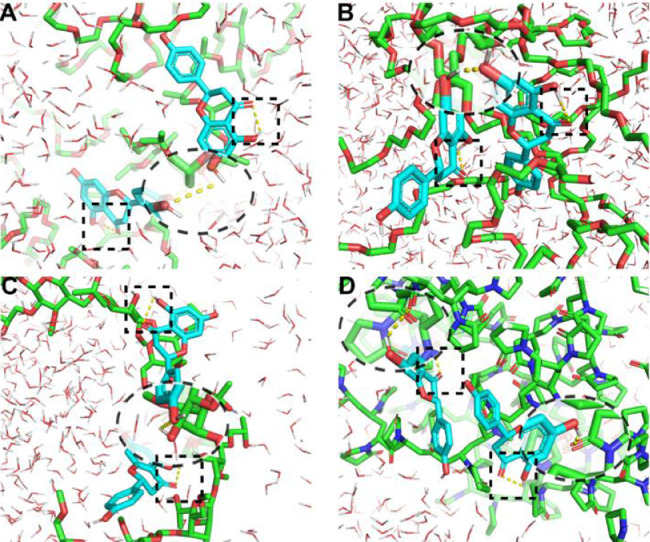

To better understand the roles of stabilizers in the inhibition of nucleation, molecular docking experiments were conducted. As shown in Fig. 7, similar intramolecular hydrogen bonds (the square virtual frame) were observed in NAR for all groups, but intermolecular hydrogen bonds (the elliptic virtual frame) were different. Both F68 and F127 can not form any hydrogen bond with NAR due to only ether bonds in their monomers, instead, the NAR molecules formed dimers through hydroxyl‑hydroxyl hydrogen bonds (Fig. 7A and 7B). On the contrary, both HPMC and PVP formed intermolecular hydrogen bonds with NAR. Compared with NAR-HPMC interactions (Fig. 7C), the intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the PVP and NAR (Fig. 7D) were much stronger. As it was shown, the hydroxyl groups in NAR interacted with the carbonyl groups (strong acceptors) in PVP, and stable NAR-PVP interactions were thus formed. Binding energies were calculated to compare the interaction strength between NAR and the stabilizers. As shown in Table S1, the PVP had the lowest binding energy (−4.33 kcal/mol), which was 1.98 times that of the F68, 1.37 times that of the F127, and 1.1 times that of the HPMC, confirming the strongest interaction between NAR and PVP.

Fig. 7.

Molecular docking of NAR with different stabilizers: (A) F68, (B) F127, (C) HPMC, and (D) PVP. The square and elliptic virtual frame represent the intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bond, respectively.

To further confirm the formation of NAR dimers, self-association studies were performed. Ethanol solution was used as a control due to its good solubility for NAR. As shown in Fig. S6, the absorbance and concentration of NAR in ethanol solution are linearly related. However, when pure water was used as the medium, the increase in absorbance gradually slowed down with increasing concentration, indicating the formation of NAR dimers [16]. A reduction in dimer formation was observed in F68, F127, and HPMC solutions, but a small amount of dimer was still detected. However, the PVP solution showed similar results to the ethanol solution, indicating that it has the strongest dimer inhibition effect among the four stabilizers.

For the supersaturation systems, drug molecules are self-assembled and nucleated through molecular interactions, such as π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding [22]. In this study, the NAR dimers were formed through the self-assembly of intermolecular hydrogen bonds during the initial stage of nucleation, and these dimers were then further aggregated and formed crystal nuclei. However, the addition of HPMC or PVP provided H-acceptors for hydrogen bond formation and inhibited the dimer formation. The nucleation process was thus delayed and even prevented, and the supersaturation was maintained [23].

In addition to NAR [24], dimer formation has also been reported during the crystallization of indomethacin [25], ibuprofen [26], tolfenamic acid [16], and mannitol [27]. For example, Mattei et al. found that tolfenamic acid dimers in its supersaturated solution, which further formed the nucleus [16]. In addition, the amount of tolfenamic acid dimer increased with its concentration elevated. This phenomenon was also found in supersaturated solutions of mannitol [27]. Further research found that the structures of mannitol dimers are also different at different supersaturation levels, more importantly, the types of dimers determine the nucleation and ultimately lead to different crystalline forms of mannitol [27]. Therefore, the formation of drug dimers is crucial for the nucleation of supersaturated systems, and prevention of the dimer formation by the addition of effective polymers is beneficial for supersaturation maintenance.

In summary, the strong intermolecular interaction between the drug and the stabilizer can prevent the self-aggregation of the drug molecules, delay the formation of crystal nuclei, and inhibit the crystallization, thereby improving the stability of the supersaturated solution and finally improving the oral bioavailability. Therefore, the choice of stabilizer is critical in the formulation of drug NCs.

4. Conclusion

In this study, four NAR NCs were formulated with F68, F127, HPMC, and PVP as stabilizers, respectively. The characterization results showed that the four NCs had similar particle sizes, morphology, and crystalline state. However, NCPVP exhibited the best dissolution behaviors, cellular uptake, permeability, oral bioavailability, and in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory effects. The mechanism is that the stabilizer inhibits the formation of the nucleus by preventing the dimerization of the NAR, thereby improving the stability of the supersaturated solution upon the dissolution of the NCs. This finding is of great significance for understanding the roles of stabilizers in the NCs and provides a deeper insight into the development of poorly water-soluble drugs.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82173765), the Science Foundation for Outstanding Youth of Liaoning Province (2021-YQ-08), Ningxia Key Research and Invention Program (No. 2021BEG02039), Basic Research Projects of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (2020LFW01), the Career Development Program for Young Teachers in Shenyang Pharmaceutical University (ZQN2019003), the Outstanding Youth Lifting Program in Shenyang Pharmaceutical University (YQ202115), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2020-MS-074), and Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Biotechnology and Bioresources Utilization (Dalian Minzu University), Ministry of Education (KF2022005), China.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ajps.2022.09.001.

Contributor Information

Ning Li, Email: ninger2003@163.com.

Mingming Zhao, Email: zhaomingming1127@163.com.

Qiang Fu, Email: graham_pharm@aliyun.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Elz A.S., Trevaskis N.L., Porter C.J.H., Bowen J.M., Prestidge C.A. Smart design approaches for orally administered lipophilic prodrugs to promote lymphatic transport. J Control Release. 2022;341:676–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalepu S., Nekkanti V. Insoluble drug delivery strategies: review of recent advances and business prospects. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5(5):442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homayouni A., Amini M., Sohrabi M., Varshosaz J., Nokhodchi A. Curcumin nanoparticles containing poloxamer or soluplus tailored by high pressure homogenization using antisolvent crystallization. Int J Pharm. 2019;562:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subramani T., Ganapathyswamy H. An overview of liposomal nano-encapsulation techniques and its applications in food and nutraceutical. J Food Sci Technol-Mysore. 2020;57(10):3545–3555. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04360-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naseema A., Kovooru L., Behera A.K., Kumar K.P.P., Srivastava P. A critical review of synthesis procedures, applications and future potential of nanoemulsions. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;287 doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirchandani Y., Patravale V.B., Brijesh S. Solid lipid nanoparticles for hydrophilic drugs. J Control Release. 2021;335:457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor R., Pathak S., Najmi A.K., Aeri V., Panda B.P. Processing of soy functional food using high pressure homogenization for improved nutritional and therapeutic benefits. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2014;26:490–497. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn K., Gullapalli R.P., Merisko-Liversidge E., Goldbach E., Wong A., Liversidge G.G., et al. A formulation strategy for gamma secretase inhibitor ELND006, a BCS class II compound: development of a nanosuspension formulation with improved oral bioavailability and reduced food effects in dogs. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(4):1462–1474. doi: 10.1002/jps.23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo M.R., Wei M.D., Li W., Guo M.C., Guo C.L., Ma M.C., et al. Impacts of particle shapes on the oral delivery of drug nanocrystals: mucus permeation, transepithelial transport and bioavailability. J Control Release. 2019;307:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma M.C., Zhang G.S., Li W., Li M., Fu Q., He Z.G. A carbohydrate polymer is a critical variable in the formulation of drug nanocrystals: a case study of idebenone. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16(12):1403–1411. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2019.1682546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orrego-Lagaron N., Martinez-Huelamo M., Vallverdu-Queralt A., Lamuela-Raventos R.M., Escribano-Ferrer E. High gastrointestinal permeability and local metabolism of naringenin: influence of antibiotic treatment on absorption and metabolism. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(2):169–180. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couto M., Cates C. Laboratory guidelines for animal care. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1920:407–430. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9009-2_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang G., Sun G., Guan H., Li M., Liu Y., Tian B., et al. Naringenin nanocrystals for improving anti-rheumatoid arthritis activity. Asian J Pharmaceut Sci. 2021;16(6):816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W., Song J., Li J., Li M., Tian B., He Z., et al. Co-amorphization of atorvastatin by lisinopril as a co-former for solubility improvement. Int J Pharm. 2021;607 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegiel L.A., Mauer L.J., Edgar K.J., Taylor L.S. Crystallization of amorphous solid dispersions of resveratrol during preparation and storage-impact of different polymers. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102(1):171–184. doi: 10.1002/jps.23358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattei A., Li T.L. Polymorph formation and nucleation mechanism of tolfenamic acid in solution: an investigation of pre-nucleation solute association. Pharm. Res. 2012;29(2):460–470. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purohit H.S., Trasi N.S., Sun D.J.D., Chow E.C.Y., Wen H., Zhang X.Y., et al. Investigating the impact of drug crystallinity in amorphous tacrolimus capsules on pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence using discriminatory in vitro dissolution testing and physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation. J Pharm Sci. 2018;107(5):1330–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang G., Wang Y., Zhang Z., He Z., Liu Y., Fu Q. FRET imaging revealed that nanocrystals enhanced drug oral absorption by dissolution rather than endocytosis: a case study of coumarin 6. J Control Release. 2021;332:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochi M., Kawachi T., Toita E., Hashimoto I., Yuminoki K., Onoue S., et al. Development of nanocrystal formulation of meloxicam with improved dissolution and pharmacokinetic behaviors. Int J Pharm. 2014;474(1–2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao P., Hu G., Chen H., Li M., Wang Y., Sun N., et al. Revealing the roles of polymers in supersaturation stabilization from the perspective of crystallization behaviors: a case of nimodipine. Int J Pharm. 2022;616 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Z.L., Wang P., Lu Y.C., Jia Z., Qu S.X., Yang W. A versatile hydrogel network-repairing strategy achieved by the covalent-like hydrogen bond interaction. Sci Adv. 2022;8(8) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui P.L., Zhang X.W., Yin Q.X., Gong J.B. Evidence of hydrogen-bond formation during crystallization of cefodizime sodium from induction-time measurements and in situ raman spectroscopy. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2012;51(42):13663–13669. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wegiel L.A., Mauer L.J., Edgar K.J., Taylor L.S. Mid-infrared spectroscopy as a polymer selection tool for formulating amorphous solid dispersions. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;66(2):244–255. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nesterov V.V., Zakharov L.N., Nesterov V.N., Calderon J.G., Longo A., Zaman K., et al. 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chroman-4-one (naringenin): x-ray diffraction structures of the naringenin enantiomers and DFT evaluation of the preferred ground-state structures and thermodynamics for racemization. J Mol Struct. 2017;1130:994–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto T., Zografi G. Physical properties of solid molecular dispersions of indomethacin with poly(vinylpyrrolidone) and poly(vinylpyrrolidone-co-vinyl-acetate) in relation to indomethacin crystallization. Pharm. Res. 1999;16(11):1722–1728. doi: 10.1023/a:1018906132279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terebetski J.L., Michniak-Kohn B. Combining ibuprofen sodium with cellulosic polymers: a deep dive into mechanisms of prolonged supersaturation. Int J Pharm. 2014;475(1–2):536–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su W.Y., Zhang Y., Liu J.M., Ma M.Q., Guo P., Liu X., et al. Molecular dynamic simulation of d-mannitol polymorphs in solid state and in solution relating with spontaneous nucleation. J Pharm Sci. 2020;109(4):1537–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.