Abstract

Background

Interventions to reduce harms related to prescription opioids are needed in primary care settings.

Objective

To determine whether a multicomponent intervention, Improving the safety of opioid therapy (ISOT), is efficacious in reducing prescription opioid harms.

Design

Clinician-level, cluster randomized clinical trial. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02791399)

Setting

Eight primary care clinics at 1 Veterans Affairs health care system.

Participants

Thirty-five primary care clinicians and 286 patients who were prescribed long-term opioid therapy (LTOT).

Intervention

All clinicians participated in a 2-hour educational session on patient-centered care surrounding opioid adherence monitoring and were randomly assigned to education only or ISOT. ISOT is a multicomponent intervention that included a one-time consultation by an external clinician to the patient with monitoring and feedback to clinicians over 12 months.

Main Measures

The primary outcomes were changes in risk for prescription opioid misuse (Current Opioid Misuse Measure) and urine drug test results. Secondary outcomes were quality of the clinician-patient relationship, other prescription opioid safety outcomes, changes in clinicians’ opioid prescribing characteristics, and a non-inferiority analysis of changes in pain intensity and functioning.

Key Results

ISOT did not decrease risk for prescription opioid misuse (difference between groups = −1.12, p = 0.097), likelihood of an aberrant urine drug test result (difference between groups = −0.04, p=0.401), or measures of the clinician-patient relationship. Participants allocated to ISOT were more likely to discontinue prescription opioids (20.0% versus 8.1%, p = 0.007). ISOT did not worsen participant-reported scores of pain intensity or function.

Conclusions

ISOT did not impact risk for prescription opioid misuse but did lead to increased likelihood of prescription opioid discontinuation. More intensive interventions may be needed to impact treatment outcomes.

KEY WORDS: long-term opioid therapy, chronic pain, treatment guidelines, adverse effects

INTRODUCTION

Although its use has declined in recent years, long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) remains commonly prescribed for chronic pain. There are, however, substantial risks of adverse events, such as overdose, associated with LTOT for chronic pain1–5 and inadequate support of long-term benefit.6–8

Opioid treatment guidelines have been developed to reduce adverse effects while optimizing potential benefits,9 though adherence to guidelines has been poor.10,11 Attempts to improve adherence to opioid treatment guidelines include systemic changes in primary care to support opioid safety intervention efforts,12,13 risk stratification monitoring and health care system initiatives,14–17 and internal health system mandates.18,19 Individual research teams have also tested strategies for enhancing prescription opioid safety. For example, a cluster-randomized trial found that a multicomponent intervention including nurse care management, registry, academic detailing, and decision support improved documentation of guideline-concordant care.20

Prescription opioid guideline recommendations include routine urine drug testing (UDT), checking prescription drug monitoring databases (PDMPs), reducing high-dose opioid use and polypharmacy, and implementing opioid treatment agreements. Recent data suggest guideline adherence may be associated with fewer adverse effects.21,22 However, it is unclear how interventions focused on improving guideline adherence may impact patient-reported outcomes, especially when they result in opioid dose-reduction or discontinuation.23

This study tests the efficacy of a multicomponent intervention designed to reduce harms related to prescription opioids and improve adherence to prescription opioid guidelines, while also examining the impact of the intervention on patient-reported pain-related outcomes. The improving the safety of opioid therapy (ISOT) intervention is based on the collaborative care model, and includes education and activation, collaboration with a nurse care manager, decision support, and outcomes monitoring. We hypothesized that randomization to ISOT would lead to improvements in prescription opioid safety and not adversely impact patient-reported pain outcomes.

METHODS

Design Overview

This cluster-randomized trial examined the efficacy of a patient-centered approach for improving safety of prescription opioids. The recruitment details and trial protocol have been published.24 Primary care providers (PCPs) were randomly assigned to receive ISOT or education only. Recruitment occurred from June 2016 to October 2018; patients were nested within clinician group assignment. Patients were enrolled for 12 months. Approval was obtained by the local institutional review board and all clinicians and patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Participants

Clinician Participants

Clinicians were recruited from the VA Portland Health Care System, which includes a hospital and eight community-based outpatient clinics and serves over 90,000 patients. All designated PCPs who provide care in this health care system were potentially eligible to participate. PCPs were invited to enroll by email, presentations at primary care staff meetings, and direct contact. Forty-four of 88 (50%) clinicians enrolled.

Patient Participants

All patients of participating clinicians and currently prescribed LTOT were potentially eligible for enrollment. LTOT was defined as receiving an opioid for three consecutive months or six opioid prescriptions in the last year with a current prescription.25 Patients were excluded if they were under age 18, receiving opioids for a terminal illness, enrolled in an opioid substitution program, receiving tramadol or buprenorphine as their only opioid, had current or past-year cancer diagnoses, or lack of telephone access.

Electronic health record (EHR) data were used to identify potentially eligible patients. Patients were recruited with a personalized letter; a response card with prepaid postage was included where they could indicate interest or decline enrollment. Interested patients were screened via telephone. Those eligible were scheduled for a baseline assessment.

Patient-reported outcomes were collected by research staff who were masked to randomization status. Assessments were conducted at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Patients were paid $50 for each research assessment visit.

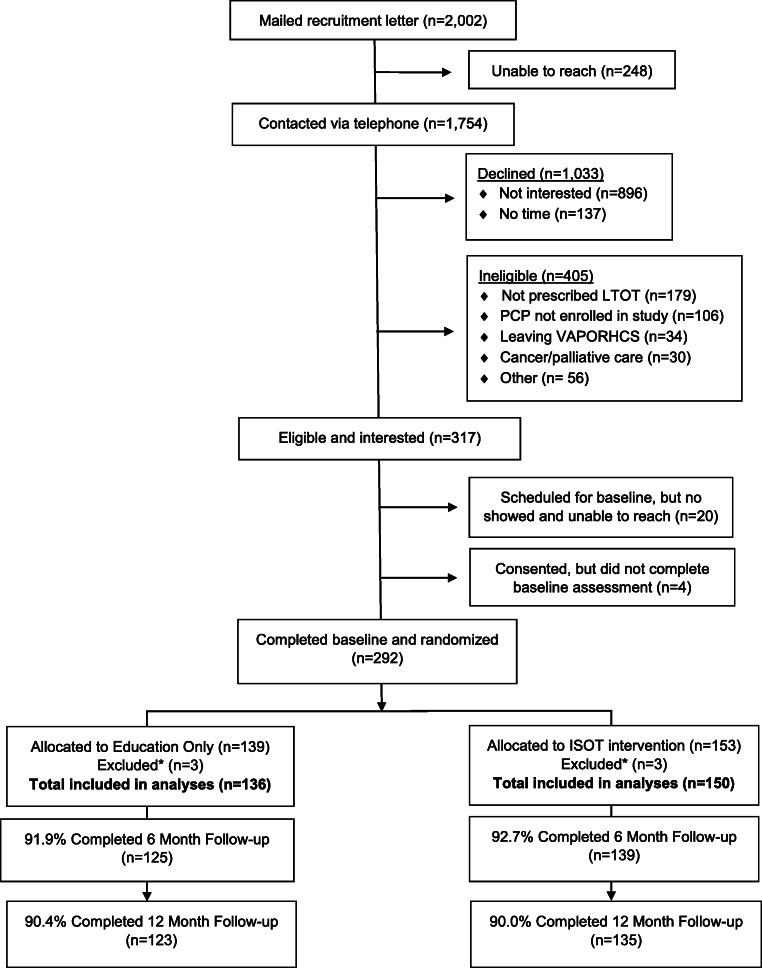

Of 2,002 patients mailed study introduction letters, 1,754 were screened by telephone, 1,033 declined to participate, and 405 were ineligible. Ultimately, 292 patients enrolled in the study (Figure 1). To maintain clusters for analysis, we excluded clinicians who had zero or one patient enrolled, which brought the final sample to 286 participants.

Figure 1.

Recruitment consort diagram. *Participants were excluded due to their assigned PCP having fewer than two patients from their panel enrolled in the study

Randomization

Following the educational session (described below), clinicians were randomized to intervention versus control group by a statistician masked to participant identity using computer-generated permuted block randomization. Clinicians were stratified by professional training (physician or nurse practitioner) and proportion of patients in their panel prescribed opioids (high vs low, based on median). Each clinician received an email from the principal investigator informing them of their randomization status. The principal investigator and study interventionist were the only research team members aware of assignment.

Treatment Arms

A 2-hour educational session was held for all participating clinicians. Led by an internist with expertise in chronic pain management and prescription opioid safety, this program provided education on patient-centered care surrounding prescription opioid adherence monitoring. Program objectives included an overview of opioid treatment guidelines, shared decision making, and strategies to balance benefits versus harms of LTOT. A recorded DVD of the educational session and handouts were provided to clinicians unable to attend the training.

Education-Only Arm

Clinicians randomized to education only were encouraged to provide usual care as indicated, which may have included pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment options, as well as more frequent primary care visits. These clinicians had no further contact with the ISOT team. Usual care services provided by the PCP included opportunities to refer to a specialty pain clinic, pharmacy, mental health, orthopedics, or other options for complementary and integrative health interventions.

ISOT Arm

Clinicians and patients randomized to intervention received support from the ISOT intervention team, which included a nurse care manager (NCM), internal medicine physician with expertise in chronic pain treatment in primary care, and psychologist with expertise in treating comorbid pain and substance use disorder. Following comprehensive medical record review, the NCM met with patients for a one-time visit to provide rationale for prescription opioid adherence screening, discuss ways that opioid-related adverse effects could be mitigated, and review methods for preventing opioid misuse. Each meeting was individually tailored with consideration to the patient’s health history, treatment plan, and self-reported goals for care. The NCM solicited input as needed from the ISOT physician and psychologist.

Following the one-time consultation session, the NCM provided tailored recommendations to the PCP about strategies for improving opioid safety. Treatment recommendations focused on reducing adverse events and improving adherence to treatment guidelines. Common recommendations included prescribing naloxone, reducing polypharmacy (particularly benzodiazepines), reducing total opioid dose or opioid tapering when indicated, increasing UDT and PDMP checks, and addressing unexpected UDT or PDMP results.26 Implementation of treatment changes was at PCP discretion.

Ongoing record review by the NCM was conducted on a biweekly basis for 1 year; as-needed recommendations were made to the patient’s care team for study duration. A registry of enrolled patients was maintained by the NCM tracking UDT administrations and results, queries of PDMP databases, contraindicated co-prescriptions, and monitoring aberrant behaviors. If evidence of potential hazardous opioid use was identified, the NCM could collaborate with the consulting physician or psychologist to provide decision support for PCPs. Any resultant issues identified via record review (e.g., lost prescriptions, early refills, evidence of aberrant UDT, overdose) were forwarded by the NCM to the primary care team, along with recommendations for potential intervention.

Primary Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was risk for prescription opioid misuse, assessed with the 17-item Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM).27,28 While only some COMM items directly relate to hazardous opioid use, the COMM has been validated against other measures, has strong psychometric characteristics, and is frequently used to examine hazardous opioid use.27–30 COMM scores range from 0 to 68. Scores of 9 or higher indicate greater risk for misuse.

A second primary outcome was aberrant UDT result. UDT was conducted at each research visit to evaluate for the presence of substances taken, including cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and opioids. Confirmatory testing was conducted for all UDT screens with unexpected results. All UDTs completed for the study were research-administered and not entered into the medical record. Patients may have also completed UDT during their participation in usual clinical care; these results were not analyzed as research outcomes.

Secondary Outcome Measures

The Trust in Physician Scale (TPS) is an 11-item self-report measure assessing trust between patients and their clinicians.31 The Participatory Decision-Making Style (PDM) is a four-item measure that assesses patient involvement in medical decision making.32 The Positive Regard Scale (PRS), a novel six-item self-report measure, was utilized to evaluate patients’ perceptions of their relationship with their PCP.

Pain intensity and function were assessed with the 7-item Chronic Pain Grade (score range 0–100).33 Higher scores indicate more severe pain or impairment in function.

EHR data were abstracted for other opioid-related outcomes. Total prescription opioid dose in morphine equivalent was calculated for each participant on the date of research assessments. Other EHR data were collected at 12 months, to evaluate whether they occurred at any time during the intervention period. These variables included whether the patient had UDT as part of standard care; was evaluated for receiving opioids from multiple prescribers through the state PDMP; experienced a prescription opioid discontinuation (defined as cessation of opioid prescriptions lasting at least 28 days and no subsequent prescriptions during the study period); discontinued benzodiazepines (analyses restricted to those receiving benzodiazepine at baseline); and received naloxone.

Other Variables

Patient demographic information was gathered via self-report at baseline and included age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, employment, socioeconomic status, and disability status. Depressive symptoms were measured with the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire; scores range from 0 to 24. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.34,35

PCPs provided personal data about demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race, provider type (physician or nurse practitioner), and number of years in practice. Administrative data were extracted on PCP panel size and proportion of panel prescribed LTOT.

Statistical Analyses

We examined differences in baseline characteristics by group, using chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. We generated data visualization and calculated averages and dispersion to compare outcomes by group across the 3 time points.

Predicted outcome scores (continuous outcomes) and predicted probability of the outcome (dichotomous outcomes) over time were modeled using mixed-effects models with clustering for patient and provider. Adjusted models included patient age, sex, depression, PCP type (physician or NP), and the percentage of their panel prescribed opioids. Outputs were the estimated averages and probabilities for each group at each time point after accounting for covariates. To aid interpretation, we report the difference in predicted values between baseline and end of follow-up, showing overall change in outcomes over time, for each group.

Pain intensity and function were tested in non-inferiority analyses; we hypothesized that ISOT would lead to improvements in opioid-related safety and not worsen pain or function. One-half standard deviation difference in change was considered the non-inferiority limit. For examining group differences in changes in clinical care outcomes, we performed t-tests and chi-square tests to examine differences between the groups.

RESULTS

A total of 44 clinicians enrolled. Nine clinicians were later excluded because an insufficient number of their patients enrolled in the trial, leaving 35 clinicians in the analyses (ISOT n=19, education only n=16). Of the 292 patients enrolled, 286 were included in the analytic sample (6 were excluded because they were associated with clinicians with only one enrolled participant); 150 were assigned to ISOT and 136 to education only. Follow-up rates were 92.3% at 6 months and 90.2% at 12 months, with no difference in group follow-up rate. During the study, five patients died from causes unrelated to opioid use and seven patients withdrew prior to study completion.

At baseline, there were no differences in clinician or patient characteristics between the ISOT and education-only groups (Table 1). Patients’ mean age was 60.7 (SD=11.2) years, 87.4% were male, and 80.8% reported white race. At the baseline research assessment visit, 11.8% had an aberrant UDT result. The most common aberrant results included cannabis/THC (2.3%), non-prescribed opioid (0.8%), and testing negative for the prescribed opioid (4.6%). The average COMM score was 11.6 (SD=7.4), indicating elevated risk for prescription opioid misuse.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Enrolled Primary Care Providers (PCPs) and Patients at Baseline

| Education only | ISOT | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Providers | (n=16) | (n=19) | |

| Provider type | 0.213 | ||

| Nurse practitioner, % (n) | 6.3% (1) | 21.1% (4) | |

| Physician, % (n) | 93.8% (15) | 79.0% (15) | |

| Male, % (n) | 31.3% (5) | 52.6% (10) | 0.203 |

| White, % (n) | 81.3% (13) | 68.4 (13) | 0.384 |

| Average panel size, M (SD) | 665.9 (±357.3) | 663.9 (±356.9) | 0.982 |

| Proportion of panel prescribed opioids, % (SD) | 9.5 (±4.2) | 9.6 (±6.6) | 0.959 |

| Age, M (SD) | 53.6 (±10.5) | 50.3 (±10.0) | 0.358 |

| Years since completing medical degree, M (SD) | 24.1 (±11.1) | 19.3 (±9.4) | 0.175 |

| Patients | (n=136) | (n=150) | |

| Age | 60.4 (11.8) | 61.2 (0.9) | 0.514 |

| Male | 84.6% (115) | 90.0% (135) | 0.166 |

| White race | 79.4% (108) | 82.0% (123) | 0.579 |

| Marital status | 0.794 | ||

| Single or never married | 5.9% (8) | 6.7% (10) | |

| Widowed | 4.4% (6) | 6.7% (10) | |

| Divorced or separated | 30.9% (42) | 27.3% (41) | |

| Married or living with partner | 58.8% (80) | 59.3% (89) | |

| Education | 0.247 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 20.6% (28) | 14.7% (22) | |

| Some college or technical school | 51.5% (70) | 60.7% (91) | |

| College graduate or above | 27.9% (38) | 24.7% (37) | |

| Income* | 0.314 | ||

| Less than $30,000 | 35.6% (47) | 30.2% (45) | |

| $30,000 to $60,000 | 38.6% (51) | 47.7% (71) | |

| Greater than $60,000 | 25.8% (34) | 22.2% (33) | |

| Pain intensity | 65.8 (15.5) | 67.0 (14.5) | 0.502 |

| Pain function | 53.6 (28.0) | 58.7 (28.1) | 0.156 |

| Depression severity (PHQ-8) | 10.8 (6.1) | 12.0 (5.6) | 0.074 |

| Opioid dose in MED | 37.3 (65.3) | 46.8 (51.0) | 0.167 |

| COMM score | 11.3 (8.0) | 11.9 (6.8) | 0.493 |

| Current benzodiazepine prescription | 7.4% (10) | 11.3% (17) | 0.250 |

| Aberrant UDT result** | 12.8% (16) | 10.9% (15) | 0.628 |

Note. Numbers represent mean (SD) for linear variables and % (n) for categorical variables. *5 patients had missing data on income. **23 patients had missing baseline urine drug test (UDT) results. PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire, a measure of depression severity; MED, morphine equivalent dose; COMM, Current Opioid Misuse Measure, a measure of risk for prescription opioid misuse; UDT, urine drug test

The study NCM met with all participants assigned to ISOT (n=150) at baseline and provided recommendations to PCPs. Two or more recommendations were provided regarding 80% (n=120) of participants over the 1-year study period. The average total number of times the NCM contacted a participant’s PCP was 3.8 (SD=2.6; range=1–12).

Mean scores from the primary and secondary outcomes are presented in Table 2. At the 12-month follow-up, the ISOT intervention did not result in significant changes in the total COMM score (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients who were maintained on opioids for the study duration, there remained no difference between groups in COMM score change (p=0.089).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes of Enrolled Patients

| Education only | ISOT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=136) | 6-month (n=125) | 12-month (n=123) | Baseline (n=150) | 6-month (n=139) | 12-month (n=135) | |

| COMM score | 11.3 (8.0) | 9.4 (6.4) | 9.3 (6.5) | 11.9 (6.8) | 9.5 (6.7) | 8.6 (5.7) |

| Any aberrant UDT result* | 12.8% (16) | 7.0% (8) | 16.2% (17) | 10.9% (15) | 14.0% (16) | 10.2% (11) |

| Pain intensity score | 65.8 (15.5) | 65.3 (17.0) | 62.1 (18.0) | 67.0 (14.5) | 64.9 (16.3) | 64.9 (16.5) |

| Pain interference score | 54.0 (28.0) | 53.3 (28.9) | 48.2 (28.9) | 58.7 (28.1) | 55.6 (28.6) | 53.4 (28.7) |

| Trust in Physicians Scale | 66.3 (18.6) | 68.0 (18.6) | 68.1 (18.0) | 66.8 (20.2) | 66.5 (21.9) | 65.9 (21.2) |

| Participatory Decision-Making Style | 50.3 (32.4) | 57.6 (31.9) | 54.3 (33.5) | 50.4 (35.7) | 51.9 (36.9) | 55.1 (34.9) |

| Positive Regard Scale | 71.1 (17.2) | 73.2 (16.4) | 73.7 (17.1) | 71.8 (17.6) | 71.3 (20.6) | 71.2 (18.7) |

Note. Numbers reported are M (SD) and % (n) for categorical variables

*Smaller n due to missing values; results presented as predicted proportions due to dichotomous outcome

Table 3.

Predicted Change in Group Scores Between Baseline and End of Follow-up

| Education only (n= 136) | ISOT (n= 150) | Difference between groups | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMM score | −1.26 (−2.22, −0.30) | −2.38 (−3.31, −1.46) | −1.12 (−2.45, 0.20) | 0.097 |

| Any aberrant UDT result* | 0.05 (−0.03, 0.13) | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.07) | −0.04 (−0.15, 0.06) | 0.401 |

| Trust in Physicians Scale | 0.74 (−2.05, 3.53) | −1.25 (−3.93, 1.43) | −1.99 (−5.83, 1.85) | 0.309 |

| Participatory Decision-Making Style | 3.69 (−1.96, 9.34) | 4.72 (−0.68, 10.13) | 1.03 (−6.73, 8.80) | 0.794 |

| Positive Regard Scale | 1.71 (−0.87, 4.29) | −0.87 (−3.34, 1.60) | −2.58 (−6.12, 0.96) | 0.154 |

| Pain intensity score | −2.17 (−4.50, 0.16) | −0.72 (−2.96, 1.52) | 1.45 (−1.76, 4.66) | 0.377 |

| Pain interference score | −2.79 (−7.40, 1.81) | −1.54 (−5.95, 2.88) | 1.26 (−5.09, 7.61) | 0.698 |

Note. Results presented as predicted change in the outcome (for continuous variables) or predicted change in the proportion with the outcome (for dichotomous variables), after adjustment for age, gender, depression severity, pain intensity, provider type (NP vs physician), and provider proportion of panel with opioid prescription

*Smaller sample size due to missing values

In adjusted analyses, the predicted proportion of patients with an aberrant research-administered UDT result did not differ between baseline and end of follow-up for either group (control: 0.05, 95% CI: −0.03, 0.13; intervention: <0.001, 95% CI: −0.06, 0.07), nor was the difference between groups significant (p=0.401). As reported in Tables 2 and 3, none of the change in measures of patient-clinician relationship quality significantly differed between groups.

Pain intensity decreased over time in both groups (control: −2.17, 95% CI: −4.50, 0.16; intervention: −0.72, 95% CI: −2.96, 1.52), and there was no significant difference in change between groups (group comparison p=0.377). Similarly, pain interference decreased over time, but not significantly (control: −2.79, 95% CI: −7.40, 1.81; intervention: −1.54, 95% CI: −5.95, 2.88) and there was no significant difference in change between groups (p=0.698). These results met our non-inferiority assumption, demonstrating that ISOT was not meaningfully worse in pain intensity or function than the education-only arm. Among participants in the intervention group who discontinued LTOT, pain intensity and function scores did not significantly change following discontinuation.

Other outcomes of prescription opioid safety are reported in Table 4. Twenty percent of ISOT participants discontinued their opioid prescriptions compared with 8.1% in the comparison group (p=0.007), and 55.6% of participants in the intervention group versus 29.3% in the comparison group received naloxone (p<0.001). There were no differences between groups in total prescription opioid dose in morphine equivalents or the proportion of patients who discontinued co-occurring benzodiazepine prescriptions.

Table 4.

Other Prescription Opioid Safety Outcomes Evaluated

| Education only | ISOT | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription opioid dose in mg morphine equivalents at final visit | 33.6 (42.2) | 34.4 (34.8) | 0.57 |

| Proportion with a prescription opioid discontinuation | 8.1% (10) | 20.0% (27) | 0.007 |

| Proportion who discontinued co-occurring benzodiazepine prescription* | 37.5% (3) | 37.5% (6) | 1.000 |

| Proportion prescribed Naloxone | 29.3% (36) | 55.6% (75) | <0.001 |

Note. Numbers represent M (SD) for linear variables and % (n) for categorical variables. *Restricted to participants who had a co-occurring benzodiazepine prescription at baseline and were still in the study at the end of follow-up (n=8 in education-only group; n=16 in ISOT group)

In secondary analyses, we explored impacts of treatment assignment on clinician opioid-related practice patterns. Clinicians in both groups had reductions in the proportion of their overall panels prescribed LTOT and increases in the proportion of patients prescribed LTOT who received a past-year UDT and PDMP check (Figure 2). There was no significant change in the proportion of patients on clinical panels prescribed LTOT with co-occurring benzodiazepine prescription or proportion with an early opioid refill for providers in either group.

Figure 2.

Changes in primary care providers’ opioid prescribing characteristics. Note. LTOT, long-term opioid therapy; UDT, urine drug test; PDMP, prescription drug monitoring program; SUD, substance use disorder

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to target the most essential elements of prescription opioid monitoring and safety among patients prescribed LTOT. The intervention was based on the collaborative care model, which is a multicomponent intervention and includes activation, decision support, and outcomes monitoring.36 The collaborative care model has demonstrated support for improving other chronic medical conditions, including pain.37–41 However, ISOT did not result in significant changes in risk for prescription opioid misuse, improvements in the clinician-patient relationship, or prescription opioid safety monitoring.

Participants assigned to ISOT were more likely to have prescription opioids discontinued and naloxone prescribed. These prescribing practices are associated with decreased likelihood of adverse opioid-related consequences,42 though some data suggest potential increased risk of death by suicide or overdose among those discontinuing opioid therapy.43 Despite increased rates of opioid discontinuation among those assigned to ISOT, the intervention was not associated with worsening of pain or function, consistent with other findings that opioid discontinuation may not change patient-reported pain intensity.44–46 NCM decision support may have activated clinicians to consider alternative pain management procedures, though more work is needed to understand decision-making behind opioid discontinuation.

Other collaborative care trials examining strategies to improve prescription opioid-related outcomes have also had mixed results. A multicomponent intervention led to improvements in guideline-concordant care, but did not impact early opioid renewals.20 Similarly, collaborative care with motivational interviewing did not impact risk for prescription opioid misuse among patients with high-risk prescription opioid use.47 Alternatively, collaborative care helped primary care patients with opioid and alcohol use disorders engage in care and achieve early abstinence.48 Thus, while collaborative care models have demonstrated efficacy for improving health outcomes, their viability for reducing risk for prescription opioid misuse may be more limited. Other psychosocial interventions have demonstrated support in reducing hazardous prescription opioid behaviors.49,50 Treatment approaches that have demonstrated the greatest efficacy in altering patient behaviors appear to involve more intensive interventions and sustained interactions with patients over weeks to months.

External factors may have limited the effectiveness of this intervention relative to the control. Several initiatives were launched within the Department of Veterans Affairs around the time this study was conducted, including release of updated opioid treatment guidelines and the VA Opioid Safety Initiative.9,51 These efforts led to changes in opioid prescribing practices.18,52,53 It would appear the current intervention, in which the main treatment component includes a NCM who provides recommendations, but is not part of the clinical team, does not meaningfully affect prescription opioid risk monitoring practices above and beyond the impacts of general mandates. Future research may test how the composition of the clinical team impacts risk-monitoring practices.

This study had several limitations. Randomization occurred at the clinician level, rather than with patients, and it is unclear how this may have impacted findings. Second, it was conducted within a single VA Medical Center and demographic characteristics of patients likely differed from other settings. Third, a portion of the clinicians enrolled had roles in research and education, and the intervention may have a different impact for clinicians devoted exclusively to clinical practice. Fourth, due to intervention complexity, clinicians and patients were unblinded (though study assessors were masked). Finally, as described, systemic factors likely impacted opioid prescribing practices for all clinicians, potentially limiting the impact of the intervention.

Overall, this study found that a multicomponent intervention was not associated with significant reductions in risk for prescription opioid misuse, rate of aberrant UDT results, or improvements in the patient-clinician relationship. The intervention was associated with higher rates of opioid discontinuation, which occurred without adverse effects on pain intensity or function. Efforts to improve opioid safety, among patients prescribed LTOT for chronic pain, may need more intensive and sustained interventions.

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by grant 1I01HX001583 from VA Health Services Research & Development. The work was also supported by resources from the VA Health Services Research and Development–funded Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care at the VA Portland Health Care System (CIN 13-404). No author reports having any potential conflict of interest with this study. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Trials Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02791399

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Puustinen J, Nurminen J, Lopponen M, et al. Use of CNS medications and cognitive decline in the aged: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Geriatrics. 2011;11:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders KW, Dunn KM, Merrill JO, et al. Relationship of opioid use and dosage levels to fractures in older chronic pain patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:310–315. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:686–691. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spooner L, Fernandes K, Martins D, et al. High-dose opioid prescribing and opioid-related hospitalization: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5051):1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness of and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276–286. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renthal W. Seeking balance between pain relief and safety: CDC issues new opioid-prescribing guidelines. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:513–514. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: The SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:872–882. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Dobscha SK. Adherence to clinical guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic pain in patients with substance use disorder. J Gen Int Med. 2011;26:965–971. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1734-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starrels JL, Becker WC, Weiner MG, Li X, Heo M, Turner BJ. Low use of opioid risk reduction strategies in primary care even for high risk patients with chronic pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:958–964. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parchman ML, Penfold RB, Ike B, et al. Team-based clinic redesign of opioid medication management in primary care: Effect on opioid prescribing. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17:319–325. doi: 10.1370/afm.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quanbeck A, Brown RT, Zgierska AE, et al. A randomized matched-pairs study of feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of systems consultation: a novel implementation strategy for adopting clinical guidelines for opioid prescribing in primary care. Implementation Sci. 2018;13:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parchman ML, Von Korff M, Baldwin LM, et al. Primary care clinic re-design for prescription opioid management. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:44–51. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Korff M, Saunders K, Dublin S, et al. Impact of chronic opioid therapy risk reduction initiatives on opioid overdose. J Pain. 2019;20:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakral M, Walker RL, Saunders K, et al. Impact of opioid dose reduction and risk mitigation initiatives on chronic opioid therapy patients at higher risk for opioid-related adverse outcomes. Pain med. 2018;19:2450–2458. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minegishi T, Frakt AB, Garrido MM, et al. Randomized program evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM): A research and clinical operations partnership to examine effectiveness. Subst Abus. 2019;40:14–19. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1540376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin L, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833–839. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders KW, Shortreed S, Thielke S, et al. Evaluation of health plan interventions to influence chronic opioid therapy prescribing. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:820–829. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, et al. Improving adherence to long-term opioid therapy guidelines to reduce opioid misuse in primary care: A cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2017;177:1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan PL, Del Re AC, Henderson PT, Trafton JA. Heathcare system-wide implementation of opioid-safety guideline recommendations: The case of urine drug screening and opioid-patient suicide- and overdose-related events in the Veterans Health Administration. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6:605–612. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0423-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Im JJ, Shachter R, Oliva EM, et al. Association of care practices with suicide attempts in US Veterans prescribed opioid medications for chronic pain management. J Gen Int Med. 2015;30:979–991. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3220-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darnall BD, Juurlink D, Kerns RD, et al. International stakeholder community of pain experts and leaders call for an urgent action on forced opioid tapering. Pain Med. 2019;20:429–433. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morasco BJ, Adams MH, Maloy PE, et al. Research methods and baseline findings of the improving the safety of opioid therapy (ISOT) cluster-randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;90:105957. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.105957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Korff M, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, et al. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:521–527. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318169d03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morasco BJ, Krebs EE, Adams MH, Hyde S, Zamudio J, Dobscha SK. Clinician response to aberrant urine drug test results of patients prescribed opioid therapy for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2019;35:1–6. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, Jamison RN. Cross-validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:770–776. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f195ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: Diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) Pain. 2011;152:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashrafioun L, Bohnert ASB, Jannausch M, Ilgen MA. Evaluation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure among substance use disorder treatment patients. J Sub Abuse Treat. 2015;55:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the Trust in Physician Scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67:1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodenheimer T, Wagner E, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prevent Med. 2012;42:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD009531. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009531.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The pathways study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction. 2016;111:1177–1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliva EM, Bowe T, Manhapra A, et al. Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: Observational evaluation. BMJ. 2020;368:m283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McPherson S, Lederhos Smith C, Dobscha SK, et al. Changes in pain intensity after discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Pain. 2018;159:2097–2104. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes CJ, Krebs EE, Brown J, Li C, Hudson T, Martin BC. Association between pain intensity and discontinuing opioid therapy or transitioning to intermittent opioid therapy after initial long-term opioid therapy: a retrospective cohort study. J Pain. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Frank JW, Carey E, Nolan C, Hale A, Nugent S, Krebs EE. Association between opioid dose reduction against patients’ wishes and change in pain severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:910–917. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borsari B, Li Y, Tighe J, et al. A pilot trial of collaborative care with motivational interviewing to reduce opioid risk and improve chronic pain management. Addiction, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1480–1488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jamison RN, Ross EL, Michna E, Chen LQ, Holcomb C, Wasan AD. Substance misuse treatment for high-risk chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2010;150:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garland EL, Hanley AW, Riquino MR, et al. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement reduces opioid misuse risk via analgesic and positive psychological mechanisms: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87:927–940. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg JM, Bilka BM, Wilson SM, Spevak C. Opioid therapy for chronic pain: Overview of the 2017 US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Pain Med. 2018;19:928–941. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldstick JE, Guy GP, Losby JL, Baldwin G, Myers M, Bohnert ASB. Changes in initial opioid prescribing practices after the 2016 release of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2116860. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandbrink F, Oliva EM, McMullen TL, et al. Opioid prescribing and opioid risk mitigation strategies in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Int Med. 2020;35:927–934. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06258-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]