Abstract

Interferon (IFN)-γ contributes to the pathogenesis of severe malaria; however, its mechanism remains unclear. Herein, differences in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria were evaluated using qualitative and quantitative (meta-analysis) approaches. The systematic review protocol was registered at PROSPERO (ID: CRD42022315213). The searches for relevant studies were performed in five databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, MEDLINE and Web of Science, between 1 January and 10 July 2022. A meta-analysis was conducted to pool the mean difference (MD) of IFN-γ levels between patients with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria using a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method). Overall, qualitative synthesis indicated that most studies (14, 58.3%) reported no statistically significant difference in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria. Meanwhile, remaining studies (9, 37.5%) reported that IFN-γ levels were significantly higher in patients with severe malaria than those in patients with uncomplicated malaria. Only one study (4.17%) reported that IFN-γ levels were significantly lower in patients with severe malaria than those in patients with uncomplicated malaria. The meta-analysis results indicated that patients with severe malaria had higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria (p < 0.001, MD: 13.63 pg/mL, 95% confidence interval: 6.98–20.29 pg/mL, I2: 99.02%, 14 studies/15 study sites, 652 severe cases/1096 uncomplicated cases). In summary, patients with severe malaria exhibited higher IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria, although the heterogeneity of the outcomes is yet to be elucidated. To confirm whether alteration in IFN-γ levels of patients with malaria may indicate disease severity and/or poor prognosis, further studies are warranted.

Subject terms: Immunology, Diseases

Introduction

Malaria is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, with an estimated 627,000 malaria deaths reported in 20201. The majority of these deaths were reported in children under 5 years of age in six countries of Africa, including Nigeria (27%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%), Uganda (5%), Mozambique (4%), Angola (3%) and Burkina Faso (3%)1. Most malaria deaths were caused by Plasmodium falciparum infection; whereas, a minority were caused by other Plasmodium spp.2–5.

Immune responses to malaria have been described previously6–8. During malaria infection, pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines play a role in protection against infection or disease pathogenesis9. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced by leukocytes such as neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes or other cells such as macrophages, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and mast cells10–14. These pro-inflammatory cytokines are interleukin (IL)-1, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-12 and IL-1815,16. IFN-γ is one of the pro-inflammatory T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines involved in protection against malaria and parasite clearance9. In combination with TNF-α and IL-12, IFN-γ inhibits parasite growth, stimulates phagocytosis and enhances the clearance of parasitised erythrocytes17.

Previous studies have indicated that elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ, contribute to the severity of cerebral malaria18,19 and severe anaemia17,20, while also being associated with an increased likelihood of death21,22. Nevertheless, the role of IFN-γ in malaria severity remains controversial, and previous studies have included only a small number of participants with severe malaria23–26. To date, no meta-analysis has been used to unveil differences in IFN-γ levels among patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria. Therefore, in this study, the differences in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe malaria and uncomplicated malaria were estimated using a meta-analysis. These findings are essential to understanding the pathogenesis of malaria and guiding further studies.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (S1 PRISMA Checklist)27. The systematic review protocol was registered at PROSPERO (ID: CRD42022315213).

Definition of severe and uncomplicated malaria

Severe falciparum malaria is defined as the presence of Plasmodium parasitemia with one or more of the following complications: impaired consciousness, severe malarial anaemia, renal impairment, significant bleeding, acidosis, jaundice, prostration, multiple convulsions, shock, hypoglycaemia and hyperparasitemia. Severe vivax malaria is defined similarly to severe falciparum malaria, but there are no thresholds for parasite density28. Uncomplicated or mild malaria is the presence of Plasmodium parasitemia without the characteristics of severe malaria.

Eligibility criteria

Studies reporting IFN-γ levels in patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria that met the PICO question criteria were included in this systematic review. The exclusion criteria were animal studies, in vitro studies, case reports or case series, review articles, studies with missing article information online, studies for which full-texts were unavailable, conference abstracts without full data, studies for which data of IFN-γ in both groups of patients could not be extracted and studies that reported IFN-γ levels after patients were treated.

Search strategy

The search terms were chosen based on the Medical Subject Headings. A combination of search terms with Boolean operators was used as follows: ‘(interferon OR IFN OR interferon-gamma OR interferon-g OR IFN-g OR interferon-γ OR IFN-γ) AND (severe OR complicated) AND (malaria OR plasmodium)’. The searches were conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Embase, MEDLINE and Web of Science between 1 January and 10 July 2022 without a restriction on the publication date (Table S1). The searches were limited to English language only.

Study selection

Two authors (MK and KUK) independently performed study selection. First, the titles and abstracts were screened for potentially relevant studies. In cases for which information from titles and abstracts was not sufficient for inclusion, the article was retained for full-text examination. Second, the full-texts of relevant studies were examined to find studies that met the eligibility criteria. Finally, disagreement between the two authors in study selection was resolved by discussion to form a consensus.

Data extraction

Two authors (KUK and AM) carried out the data extraction, and data from the included studies were cross-checked by another author (MK). As a result, the following data were extracted to the spreadsheet: the name of the first author, publication year, study location, period of data collection, number of patients, age group, percentage of male participants, data on IFN-γ levels (qualitative data, mean with standard deviation or median with range for meta-analysis), parasite density, the technique used for detecting malaria parasites and technique used for measuring IFN-γ.

Quality of the included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional, prospective observational, and case–control studies29.

Data syntheses

Data syntheses included qualitative and quantitative syntheses. A qualitative synthesis was the narrative synthesis of the difference in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria. A quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was conducted to pool the mean difference (MD) of IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria. The random-effects model was employed to pool the MDs using the DerSimonian and Laird method30. The mean and standard deviation were estimated from the median and range as described previously31. Comparing the mean and standard deviation between groups of participants was carried out using a protocol described previously32. If the standard deviation was unavailable, a value was borrowed from other studies (with the lowest standard deviation) in the same meta-analysis33. The heterogeneity of the estimated effects between studies was assessed using Cochrane Q and I2 tests. A Cochrane Q test result with a significant value (p) less than 0.1 or an I2 result of more than 50% indicated heterogeneity in the estimates of effect between studies. When heterogeneity was revealed, a meta-regression analysis was performed to identify the source(s) of heterogeneity in the effect estimates. Then, a subgroup analysis was performed to determine the differences in the effect estimates between the subgroups of interest. Finally, a sensitivity analysis using the leave-one-out method34 was performed to test whether the meta-analysis was robust. Sensitivity analysis between studies that reported mean/standard deviation and median/range and studies that reported mean without standard deviation was conducted to assess the effect of changing the assumptions made. The sensitivity analysis between studies that reported mean/standard deviation and those with median/range of IFN-γ levels in patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria was conducted using a subgroup analysis. Publication bias was assessed by visually assessing funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s test for small-study effects. If publication bias was found, the trim-and-fill method35 was applied to adjust the pooled effect estimates. The meta-analysis was performed using Stata version 17.0 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, USA).

Results

Search results

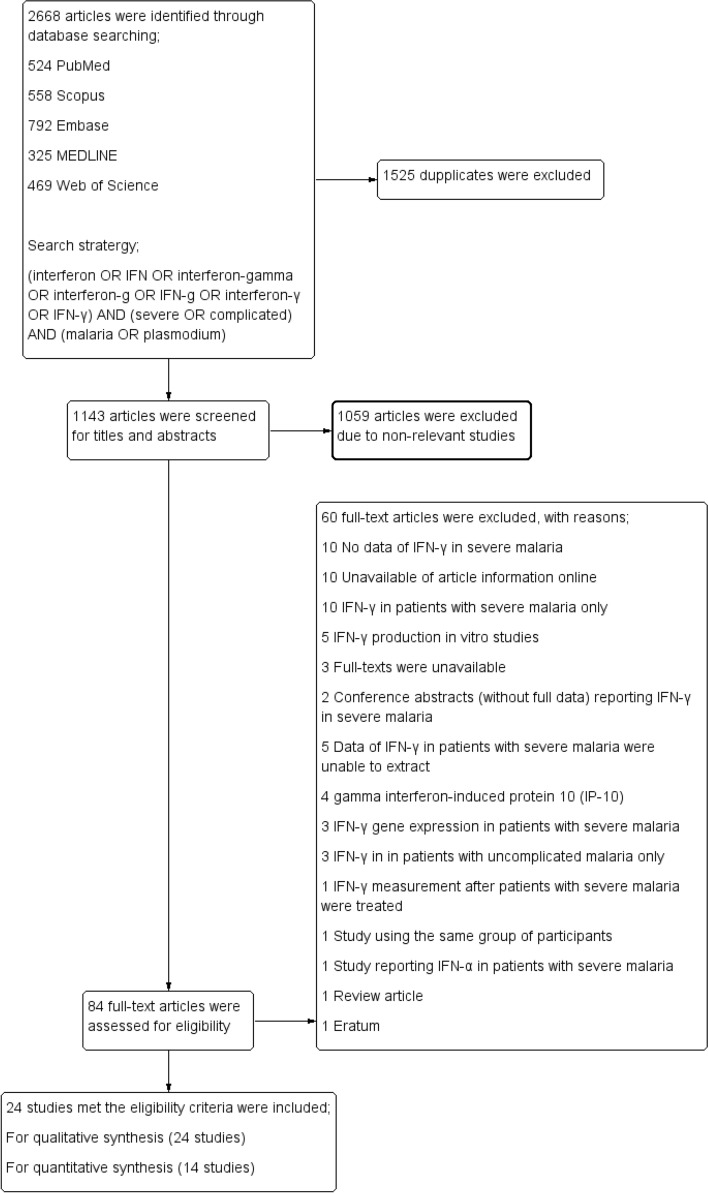

A total of 2668 articles were identified from a database search, including 524 articles from PubMed, 558 from Scopus, 792 from Embase, 325 from MEDLINE and 469 from Web of Science. After study selection, 24 studies that met the eligibility criteria were included in the review (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Characteristics of the included studies

The included studies were published between 1990 and 2000 (3 studies, 12.5%), 2000 and 2010 (10 studies, 41.7%) and 2011 and 2017 (11 studies, 45.8%). The study designs were as follows: case–control (10 studies, 41.7%), prospective observational (9 studies, 37.5%), cross-sectional (3 studies, 12.5%) and prospective cohort (2 studies, 8.33%) studies. The studies were located in Africa (11 studies, 45.8%), Asia (7 studies, 29.2%), South America (3 studies, 12.5%), North America (1 study, 4.17%), Europe (1 study, 4.17%) and both African and Asian countries (1 study, 4.17%). Most of the included studies used only microscopy for identification of malaria parasites (16 studies, 66.7%). Most of the included studies used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure IFN-γ in the blood of participants (15 studies, 62.5%). Other characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. In addition, details of the included studies are provided in Table S2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 24 included studies.

| Characteristics | N | Percentage (%, total = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Publication years | ||

| 1994–2000 | 3 | 12.5 |

| 2000–2010 | 10 | 41.7 |

| 2011–2017 | 11 | 45.8 |

| Study designs | ||

| Case–control studies | 10 | 41.7 |

| Prospective observational studies | 9 | 37.5 |

| Cross-sectional study | 3 | 12.5 |

| Prospective cohort studies | 2 | 8.33 |

| Study locations | ||

| Africa | 11 | 45.8 |

| Asia | 7 | 29.2 |

| South America | 3 | 12.5 |

| North America | 1 | 4.17 |

| Europe | 1 | 4.17 |

| Africa and Asia | 1 | 4.17 |

| Age groups of participants | ||

| Children | 10 | 41.7 |

| Adults | 7 | 29.2 |

| All age groups | 7 | 29.1 |

| Malaria detection methods | ||

| Microscopy | 16 | 66.7 |

| Microscopy/PCR | 3 | 12.5 |

| Microscopy/RDT | 2 | 8.33 |

| Microscopy/PCR/IFA | 1 | 4.17 |

| PCR | 1 | 4.17 |

| Not specified | 1 | 4.17 |

| TNF-α measurement | ||

| ELISA | 15 | 62.5 |

| Bead-based assays | 9 | 37.5 |

Quality of the included studies

The quality of the included studies was determined using the STROBE checklist. The assessment results showed that seven of nine prospective observational studies (77.8%) were of high quality, while three were of moderate quality (22.2%). Eight of the ten case–control studies (70%) were of high quality, while two were of moderate quality (30%). Two prospective cohort studies were of high quality, and one cross-sectional study was of moderate quality (Table S3).

Qualitative synthesis

The difference in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria was qualitatively described using the results from individual studies. Overall, nine studies (37.5%) reported that IFN-γ levels were significantly higher in patients with severe malaria than those in patients with uncomplicated malaria18,19,23–25,36–39. Meanwhile, 14 studies (58.3%) reported no statistically significant differences in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria17,20,22,40–51. Only one study (4.17%) reported that IFN-γ levels were significantly lower in patients with severe malaria than those in patients with uncomplicated malaria (Table 2). Among studies that reported significantly higher IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria18,19,23–25,36–39, six studies (66.7%) reported severe P. falciparum infections18,19,23,25,38,39 and three studies (33.3%) reported severe P. vivax infections24,36,37. Meanwhile, 14 studies reported no difference in IFN-γ levels between the two groups17,20,22,40–51, and one study that reported significantly lower IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria17 reported only P. falciparum infection.

Table 2.

Differences in IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria based on qualitative data.

| Studies | Plasmodium species | IFN-γ levels* |

|---|---|---|

| Andrade et al.36 | P. vivax | Significantly higher |

| Mirghani et al.23 | P. falciparum | Significantly higher |

| Munde et al.38 | P. falciparum | Significantly higher |

| Singotamu et al.24 | P. vivax | Significantly higher |

| Tangteerawatana et al.39 | P. falciparum | Significantly higher |

| Wroczyńska et al.25 | Severe P. falciparum vs. uncomplicated P. falciparum/P. vivax/P. ovale/P. malariae | Significantly higher |

| Lopera-Mesa et al.18 | P. falciparum | Significant higher (cerebral malaria), no difference (noncerebral severe malaria) |

| Mandala et al.19 | P. falciparum | Significantly higher (cerebral malaria), no difference (severe malarial anaemia) |

| Mendonça et al.37 | P. vivax | Significantly higher (cerebral malaria) |

| Berg et al.40 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Duarte et al.(Gabon)22 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Duarte et al.,(India)22 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Ghanchi et al.41 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Jain et al.42 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Jakobsen et al.43 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Kwiatkowski et al.44 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Nmorsi et al.45 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Ong’echa et al.20 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Perera et al.48 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Phawong et al.47 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Prakash et al.48 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Rovira-Vallbona et al.49 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Sinha et al.52 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Yamada-Tanaka et al.51 | P. falciparum | No significant difference |

| Oyegue-Liabagui et al.17 | P. falciparum | Significantly lower |

*Results based on the statistical tests by included studies.

Quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis)

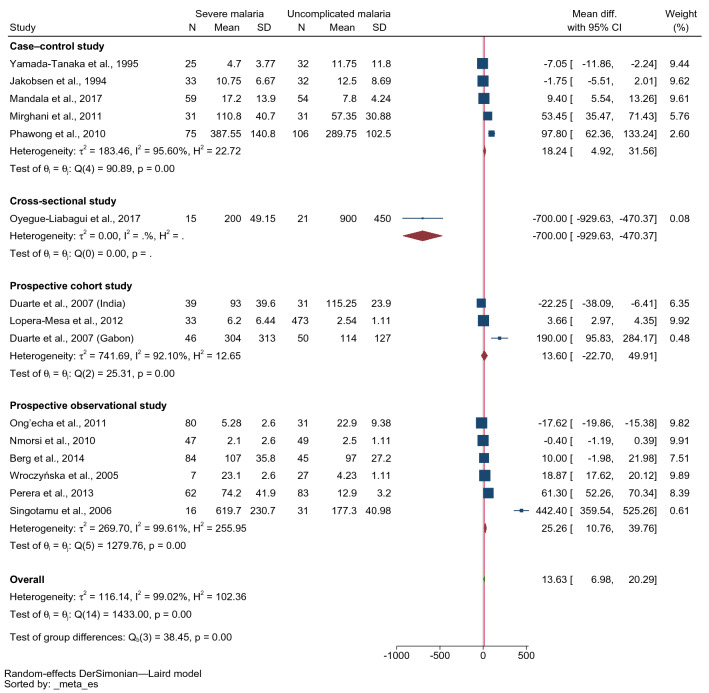

The difference in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria was estimated using 15 studies17–20,22–25,40,43,45–47,51. The lowest MD was identified in the study conducted in Gabonese children (− 700 pg/mL, 95% confidence interval [CI] − 929.63–470.37 pg/mL)17. The highest MD was identified in the study conducted in India (442.40 pg/mL, 95% CI 359.54–552.26 pg/mL)24. Four studies demonstrated that patients with severe malaria had lower mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria17,20,22,51. Two studies demonstrated no difference in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria43,45. Meanwhile, six studies showed that patients with severe malaria had higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria22–25,46,47. Overall, the results demonstrated that patients with severe malaria had higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria (p < 0.001, MD: 13.63 pg/mL, 95% CI 6.98–20.29 pg/mL, I2: 99.02%, 14 studies/15 study sites, 652 severe cases/1096 uncomplicated cases, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot demonstrating the pooled MD of INF-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria. CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation.

Because of the high heterogeneity of the effect estimates among the included studies, a meta-regression analysis incorporating study design, location (continent), age group and technique used to measure the IFN-γ levels was conducted to identify whether these covariates were the source(s) of heterogeneity. The findings showed that study design (p < 0.001), age group (p = 0.001), location (continent, p < 0.001) and technique used to measure the IFN-γ levels (p < 0.009) were sources of heterogeneity in the effect estimates among the included studies. Therefore, subgroup analyses of study design, age group, location (continent) and technique used to measure the IFN-γ levels were performed.

The subgroup analysis by the study design showed that higher mean IFN-γ levels were found in patients with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria in prospective observational studies (MD: 25.26 pg/mL, 95% CI 10.76–39.76 pg/mL, I2: 99.61%, six studies, 296 severe cases/266 uncomplicated cases) and case–control studies (MD: 18.24 pg/mL, 95% CI 4.92–31.56 pg/mL, I2: 95.6%, five studies, 223 severe cases/255 uncomplicated cases). Meanwhile, no difference in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria was identified in prospective cohort studies (MD 13.6 pg/mL, 95% CI − 22.7–49.91 pg/mL, I2: 92.1%, two studies with three study sites, 118 severe cases/554 uncomplicated cases, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot demonstrating the pooled MD of INF-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria stratified by study design. CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation.

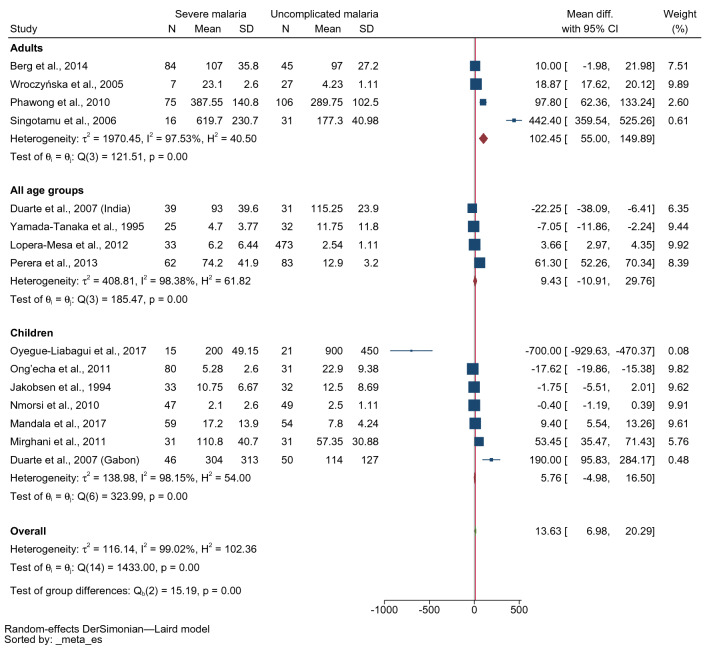

The subgroup analysis by the age of the enrolled patients showed no differences in mean IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria in children (MD 5.76 pg/mL, 95% CI − 4.98–16.5 pg/mL, I2: 98.15%, seven studies, 311 severe cases/268 uncomplicated cases) and all age groups (MD 9.43 pg/mL, 95% CI − 10.91–29.76 pg/mL, I2: 98.38%, four studies, 159 severe cases/619 uncomplicated cases). Meanwhile, higher mean IFN-γ levels were found in adults with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria (MD 102.45 pg/mL, 95% CI 55–149.89 pg/mL, I2: 97.53%, four studies, 182 severe cases/209 uncomplicated cases, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot demonstrating the pooled MD of INF-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria stratified by age group. CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation.

The subgroup analysis by the study location (continent) showed higher mean IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria among studies that were conducted in Asia (MD: 127.85 pg/mL, 95% CI 48.31–207.38 pg/mL, I2: 98.32%, four studies, 192 severe cases/251 uncomplicated cases). However, no differences in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria were found among studies conducted in Africa (MD: 6.35 pg/mL, 95% CI − 3.53–16.23 pg/mL, I2: 97.86%, eight studies, 395 severe cases/313 uncomplicated cases, Fig. 5). Among studies conducted in Africa, there were no differences in mean IFN-γ levels in children with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria among studies that enrolled children (MD: 5.76 pg/mL, 95% CI − 4.98–16.50 pg/mL, I2: 98.15%, seven studies, 311 severe cases/268 uncomplicated cases, Supplementary Fig. S1). Among studies conducted in Asia, no difference in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated was evident in adults (MD 267.98 pg/mL, 95% CI − 69.7–605.66 pg/mL, I2: 98.15%, two studies, 91 severe cases/137 uncomplicated cases) and all age groups (MD 17.79 pg/mL, 95% CI − 62.09–101.66 pg/mL, I2: 98.76%, two studies, 101 severe cases/114 uncomplicated cases, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 5.

Forest plot demonstrating the pooled MD of INF-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria stratified by location (continent). CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation.

The subgroup analysis by the technique for IFN-γ measurement showed higher mean IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria among studies using ELISA for IFN-γ measurement (MD: 26.79 pg/mL, 95% CI 15.26–38.31 pg/mL, I2: 99.05%, ten studies with 11 study sites). However, no differences in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria were found among studies using bead-based assays for IFN-γ measurement (MD: 0.95 pg/mL, 95% CI − 12.29–14.18 pg/mL, I2: 99.10%, four studies, 256 severe cases/603 uncomplicated cases, 396 severe cases/492 uncomplicated cases, Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot demonstrating the pooled MD of INF-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria stratified by methods for INF-γ measurement. CI confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to test whether the meta-analysis results were robust. This inquiry into the sensitivity of the meta-analysis of IFN-γ levels in severe and uncomplicated malaria demonstrated that patients with severe malaria had higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria when the leave-one-out method was applied (p < 0.05, Fig. 7), indicating that the results of the meta-analysis were robust. The sensitivity analysis between studies that reported mean/standard deviation and median/range and studies that reported mean without standard deviation was performed. Results showed that patients with severe malaria had higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria (p < 0.001, MD: 20.12 pg/mL, 95% CI 9.56–30.69 pg/mL, I2: 98.39%, 12 studies/13 study sites, 598 severe cases/1020 uncomplicated cases, Supplementary Fig. S3). The sensitivity analysis between studies that reported mean/standard deviation and those with median/range of IFN-γ levels in patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria was conducted using the subgroup analysis. Results indicated that patients with severe malaria had higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria among studies that reported mean/standard deviation of IFN-γ levels (MD: 38.64 pg/mL, 95% CI 20.53–56.75 pg/mL, I2: 99.57%, five studies, 147 severe cases/211 uncomplicated cases). Meanwhile, no differences in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria were found among studies that reported median/range of IFN-γ levels (MD: 7.74 pg/mL, 95% CI − 1.24–16.71 pg/mL, I2: 97.93%, nine studies with ten study sites, 505 severe cases/885 uncomplicated cases, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 7.

Forest plot demonstrating the sensitivity analysis (leave-one-out method) of the pooled MD of INF-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria. CI confidence interval.

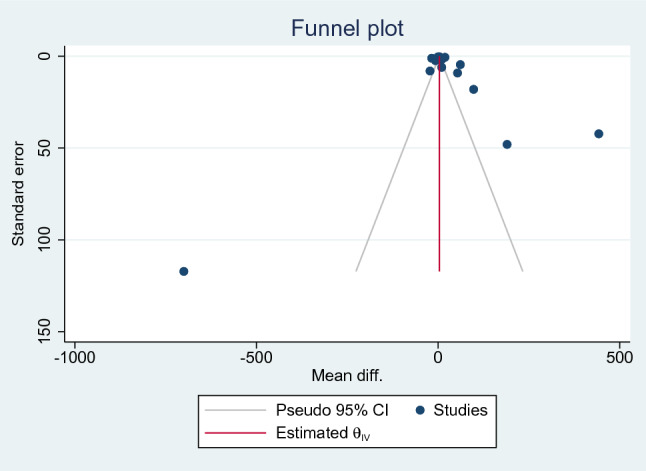

Publication bias

The publication bias of the effect estimates among the included studies was assessed by visualisation of funnel plot symmetry and Egger’s test for small-study effect. In the meta-analysis between IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria, asymmetry of the funnel plot was suspected (Fig. 8), and Egger’s test exhibited a small-study effect (p < 0.001), showing that publication bias was discovered. The trim-and-fill method was applied to adjust the pooled effect estimate, and the rresults showed that the pooled MD of IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria after adjusting for publication bias was 13.634 pg/mL (95% CI 6.979–20.29 pg/mL).

Figure 8.

Funnel plot of the studies included in the meta-analysis between patients with severe malaria and uncomplicated malaria. CI confidence interval.

Discussion

The main feature of this study was the comparison of IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria. The results of the qualitative synthesis demonstrated that most studies that investigated IFN-γ levels in both patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria revealed no statistically significant IFN-γ levels between the two clinical outcomes. Meanwhile, few studies have reported that IFN-γ levels were significantly higher in patients with severe malaria than those in patients with uncomplicated malaria. For quantitative synthesis by meta-analysis, the higher IFN-γ levels were observed in patients with severe malaria than those in patients with uncomplicated malaria. Although a high degree of heterogeneity of the outcome existed, the meta-analysis results implied that IFN-γ levels were associated with malaria severity, i.e. increased levels positively correlated with increased severity.

IFN-γ levels related to malaria severity were observed by in vitro studies52–54. Nevertheless, a study on children with malaria argued that reduced IFN-γ levels were associated with malaria severity55. A discrepancy in IFN-γ levels and malaria severity between studies might be because of differences in the different participants enrolled in each as suggested previously20. Various severe complications among patients, such as anaemia, parasitemia levels or cerebral malaria, might cause the differences in the MD in IFN-γ levels between severe and uncomplicated malaria. A previous study indicated that IFN-γ production was associated with the reduced prevalence of anaemia caused by P. falciparum; hence, IFN-γ was suggested to be an immunity-based protection against severe malarial anaemia17. A previous study found that IFN-γ levels were negatively associated with parasitemia, suggesting that this cytokine has antiparasitic effects46. Increased IFN-γ levels were also related to high malarial parasitemia52. This association may be due to malarial parasitemia caused by the production of IFN-γ by immune cells56. In comparison to severe malarial anaemia, patients with cerebral malaria showed higher levels of pro-inflammatory/Th1 cytokines19, indicating that the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in severe malaria is poorly regulated21.

Although the meta-analysis results exhibited higher mean IFN-γ levels in severe malaria than in uncomplicated malaria, the degree of heterogeneity among studies included in the meta-analysis was extremely high. The meta-regression and subgroup analyses of study design, continents, age groups, and techniques for IFN-γ measurement proposed that these parameters were sources of heterogeneity in the outcome. Considering study design as a source of heterogeneity, prospective observational and case–control studies showed higher mean IFN-γ levels were found in patients with severe malaria compared to those with uncomplicated malaria. Meanwhile, the prospective cohort studies indicated no difference. These results might be because only two prospective cohort studies were included in the subgroup analysis, which might bias the results of the subgroup analysis. Considering the continent as another source of heterogeneity, studies conducted in Asia showed higher mean IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria than those with uncomplicated malaria. However, there was no difference in mean IFN-γ levels among studies performed in Africa, indicating that the different populations investigated may have had various immune responses to malaria. In Africa, where falciparum malaria is endemic, the populations are more exposed to infections; hence, they may have acquired immune responses against malaria infections or severity57–60. Therefore, it is possible that both patients with severe and uncomplicated malaria showed comparable cytokine responses, which causes non-statistical significance between groups in this meta-analysis. In Asia, where falciparum malaria is less endemic, most populations are less exposed to infections; hence, they are non-immune or semi-immune responses to malaria infections61. Therefore, patients with severe malaria in Asian countries might develop a stronger immune response to the infections than those with uncomplicated malaria. For example, Singotamu et al.24 in India indicated that P. vivax infections demonstrated very high mean IFN-γ levels (619.7 pg/mL) in patients with severe malaria compared with uncomplicated malaria (177.3 pg/mL). Additional background histories or co-occurrence with pathogens other than malarial ones in various areas might manifest different immune responses in patients with malaria. The histories of the individuals studied may add a layer of complexity to the findings on the immune response to malaria6.

Considering age groups as another source of heterogeneity in the outcome, no differences in mean IFN-γ levels in children with severe malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria, but adults with severe malaria showed higher mean IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria. This result might be explained by the fact that studies enrolling children with severe malaria were conducted in Africa, where malaria is endemic. Meanwhile, studies enrolling adults with severe malaria were conducted in Asia, where malaria is less endemic. Across sub-Saharan Africa, where the disease is hyper-endemic, most people are almost continuously infected with P. falciparum. Most infected adults rarely experience severe disease because of the acquired immunity against the infection. In areas where malaria is less endemic, such as Asia, a higher risk of severe disease is frequently observed among adults than children as adults develop a stronger immune response to the infection, but infants and children occasionally do not. This reason explained the possible cause of high cytokine response, including IFN-γ response to the infection.

Considering the techniques for measuring IFN-γ as another source of heterogeneity of the outcome, studies using ELISA exhibited higher mean IFN-γ levels in patients with severe malaria than in those with uncomplicated malaria. However, studies using bead-based assays indicated no differences in mean IFN-γ levels between patients with severe and those with uncomplicated malaria. Multiplex bead-based assays provide the means to simultaneously measure multiple proteins in a single reaction compared to ELISA, which measures a single protein in a cone reaction62. A study comparing the overall performance of the two methods for cytokine profiles demonstrated that the ELISA and bead-based assays yielded similar results63. Notably, ELISA was more sensitive in the low concentration range of the standard curve, whereas bead-based assays could detect higher protein concentrations63. Another study that measured IFN-γ levels using both techniques indicated comparable detection of plasma IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, and TNF-α, but the ELISA missed a cytokine such as IL-564. Therefore, no study yet warrants the difference in performance between the two techniques for detecting IFN-γ in the blood. However, the results of the subgroup meta-analysis might guide further studies to examine the difference in the real performance of these techniques.

IFN-γ contributes to the activation and differentiation of B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes and macrophages65–67. The IFN-gamma receptor (R) locations were in lymphoid organs such as the B-cell areas of lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, and in epithelial tissues of the intestinal system, lung, and endometrial mucosa cells68. Studies in mice models indicated that treatment of mice infected with blood-stage P. berghei by anti-IFN-γ antibody failed to control the infection parasites69,70. Additionally, delayed parasite elimination was found among IFN-γ-deficient or IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR)-deficient mice or anti-IFN-γ antibody-treated mice71–73. During Plasmodium infection, γδ T-cells that express CD40 ligand produce IFN-γ in response to infection by enhancement of dendritic cell activation to remove malaria parasites74. In the pathogenesis of severe malaria, many studies have indicated that IFN-γ is vital for developing severe malaria, particularly cerebral malaria, by affecting endothelial integrity70,72,75,76. During cerebral malaria, IFN—producing CD8 + T-cells are recruited to the brain and cause cerebral pathology by destroying the blood–brain barrier in perforin- and granzyme-dependent manner77,78. IFN-γ production is modulated by several cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-18 or broadly reactive antigen receptors79. In the study by Wroczyńska et al.25, increased IFN-γ accompanied by increased IL-18 levels were observed in patients with severe malaria, indicating that excessive production of both cytokines is associated with severe malaria infections. IL-18-dependent IFN-γ overproduction was reported to relate to decreased IL-12 levels25. Therefore, these data suggested that severe malaria is associated with increased IFN-γ and decreased IL-12 levels, indicating the occurrence of immunoregulation in resolving malaria infection25. Furthermore, reduced IL-12 levels were associated with suppression of Th1 cytokine activation by NK cells or CD8 cells56. The previous studies also showed that IFN-γ was associated with IL-10 and IL-6, indicating a balance between these cytokines23,80. IFN-γ and IL-10 were markedly increased in patients with severe malaria48,81.

This study had some limitations. First, the degree of heterogeneity was extreme in the meta-analysis. Although meta-regression and subgroup analyses were conducted to identify the source(s) of heterogeneity, the heterogeneity remained in the subgroup analysis, showing that other factors confound the association between IFN-γ levels and malaria severity. Second, publication bias among the studies included in the meta-analysis was noted. Therefore, the pooled effect estimate (MD of IFN- γ levels) after applying the trim-and-fill method should be considered.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with severe malaria present higher IFN-γ levels than those with uncomplicated malaria, although the heterogeneity of the outcomes is yet to be elucidated. To confirm whether alteration in IFN-γ levels of patients with malaria may indicate disease severity and/or poor prognosis, further studies are warranted.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., K.U.K. and M.K.; methodology, A.M., K.U.K. and M.K.; software, M.K.; validation, F.R.M., P.W., and K.U.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K.; resources, P.W.; data curation, A.M., W.M. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, F.R.M., W.M., P.W..; visualization, M.K.; supervision, P.W.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the Acknowledgements section has been removed. As the funder has no role in the data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

12/9/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-022-25996-4

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-21965-z.

References

- 1.WHO. World Malaria Report 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040496. Accessed 23 Jun 2022.

- 2.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GJ, Masangkay FR. Prevalence and risk factors related to poor outcome of patients with severe Plasmodium vivax infection: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and analysis of case reports. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:363. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GD, Masangkay FR. Severity and mortality of severe Plasmodium ovale infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0235014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GD, Masangkay FR. Prevalence of severe Plasmodium knowlesi infection and risk factors related to severe complications compared with non-severe P. knowlesi and severe P. falciparum malaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2020;9:106. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00727-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GD, Masangkay FR. Global prevalence and mortality of severe Plasmodium malariae infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar. J. 2020;19:274. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03344-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long CA, Zavala F. Immune responses in malaria. Cold Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017;7:a025577. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez C, Yepes-Perez Y, Hincapie-Escobar N, Diaz-Arevalo D, Patarroyo MA. What is known about the immune response induced by Plasmodium vivax malaria vaccine candidates? Front. Immunol. 2017;8:126. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson MM, Riley EM. Innate immunity to malaria. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:169–180. doi: 10.1038/nri1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angulo I, Fresno M. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of and protection against malaria. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002;9:1145–1152. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.6.1145-1152.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2007;45:27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kany S, Vollrath JT, Relja B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:6008. doi: 10.3390/ijms20236008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukai K, Tsai M, Saito H, Galli SJ. Mast cells as sources of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors. Immunol. Rev. 2018;282:121–150. doi: 10.1111/imr.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:491. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De LKT, Whiting CV, Bland PW. Proinflammatory cytokine synthesis by mucosal fibroblasts from mouse colitis is enhanced by interferon-gamma-mediated up-regulation of CD40 signalling. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007;147:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson CM, Jung JY, Nau GJ. Interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-18 cooperate to control growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Cytokine. 2012;60:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Netea MG, Stuyt RJ, Kim SH, Van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ, Dinarello CA. The role of endogenous interleukin (IL)-18, IL-12, IL-1beta, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the production of interferon-gamma induced by Candida albicans in human whole-blood cultures. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185:963–970. doi: 10.1086/339410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyegue-Liabagui SL, Bouopda-Tuedom AG, Kouna LC, Maghendji-Nzondo S, Nzoughe H, Tchitoula-Makaya N, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in children with malaria in Franceville, Gabon. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017;6:9–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopera-Mesa TM, Mita-Mendoza NK, van de Hoef DL, Doumbia S, Konaté D, Doumbouya M, et al. Plasma uric acid levels correlate with inflammation and disease severity in malian children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandala WL, Msefula CL, Gondwe EN, Drayson MT, Molyneux ME, MacLennan CA. Cytokine profiles in malawian children presenting with uncomplicated malaria, severe malarial anemia, and cerebral malaria. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2017;24:e00533–e616. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00533-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong'echa JM, Davenport GC, Vulule JM, Hittner JB, Perkins DJ. Identification of inflammatory biomarkers for pediatric malarial anemia severity using novel statistical methods. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:4674–4680. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05161-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day NP, Hien TT, Schollaardt T, Loc PP, Chuong LV, Chau TT, et al. The prognostic and pathophysiologic role of pro- and antiinflammatory cytokines in severe malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180:1288–1297. doi: 10.1086/315016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duarte J, Deshpande P, Guiyedi V, Mécheri S, Fesel C, Cazenave PA, et al. Total and functional parasite specific IgE responses in Plasmodium falciparum-infected patients exhibiting different clinical status. Malar. J. 2007;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirghani HA, Eltahir HG, A-elgadir TM, Mirghani YA, Elbashir MI, Adam I. Cytokine profiles in children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria in an area of unstable malaria transmission in central sudan. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2011;57:392–395. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singotamu L, Hemalatha R, Madhusudhanachary P, Seshacharyulu M. Cytokines and micronutrients in Plasmodium vivax infection. J. Med. Sci. 2006;6:962–967. doi: 10.3923/jms.2006.962.967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wroczyńska A, Nahorski W, Bakowska A, Pietkiewicz H. Cytokines and clinical manifestations of malaria in adults with severe and uncomplicated disease. Int. Marit. Health. 2005;56:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deloron P, Dumont N, Nyongabo T, Aubry P, Astagneau P, Ndarugirire F, et al. Immunologic and biochemical alterations in severe falciparum malaria: Relation to neurological symptoms and outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994;19:480–485. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO . WHO Guidelines for Malaria. WHO; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: An update. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2007;28:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ. Statistics with Confidence. 2. BMJ Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins, J. P. T. et al. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021): Cochrane (2021). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 34.Cheng H, Garrick DJ, Fernando RL. Efficient strategies for leave-one-out cross validation for genomic best linear unbiased prediction. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017;8:38. doi: 10.1186/s40104-017-0164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi L, Lin L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: Practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine. 2019;98:e15987. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrade BB, Reis-Filho A, Souza-Neto SM, Clarncio J, Camargo LM, Barral A, et al. Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria exhibits marked inflammatory imbalance. Malar. J. 2010;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendonça VRR, Souza LCL, Garcia GC, Magalhães BML, Gonçalves MS, Lacerda MVG, et al. Associations between hepcidin and immune response in individuals with hyperbilirubinaemia and severe malaria due to Plasmodium vivax infection. Malar J. 2015;14:407. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0930-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munde EO, Okeyo WA, Anyona SB, Raballah E, Konah S, Okumu W, et al. Polymorphisms in the Fc gamma receptor IIIA and Toll-like receptor 9 are associated with protection against severe malarial anemia and changes in circulating gamma interferon levels. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:4435–4443. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00945-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tangteerawatana P, Pichyangkul S, Hayano M, Kalambaheti T, Looareesuwan S, Troye-Blomberg M, et al. Relative levels of IL4 and IFN-gamma in complicated malaria: Association with IL4 polymorphism and peripheral parasitemia. Acta Trop. 2007;101:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg A, Patel S, Gonca M, David C, Otterdal K, Ueland T, et al. Cytokine network in adults with falciparum Malaria and HIV-1: Increased IL-8 and IP-10 levels are associated with disease severity. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghanchi NK, Hasan Z, Islam M, Beg MA. MAD 20 alleles of merozoite surface protein-1 (msp-1) are associated with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Pakistan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2015;48:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain V, Armah HB, Tongren JE, Ned RM, Wilson NO, Crawford S, et al. Plasma IP-10, apoptotic and angiogenic factors associated with fatal cerebral malaria in India. Malar. J. 2008;7:83. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jakobsen PH, Morris-Jones S, Theander TG, Hviid L, Hansen MB, Bendtzen K, et al. Increased plasma levels of soluble IL-2R are associated with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994;96:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwiatkowski D, Hill AV, Sambou I, Twumasi P, Castracane J, Manogue KR, et al. TNF concentration in fatal cerebral, non-fatal cerebral, and uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1990;336:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nmorsi OPG, Isaac C, Ukwandu NCD, Ohaneme BA. Pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines profiles among Nigerian children infected with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2010;3:41–44. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60029-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perera MK, Herath NP, Pathirana SL, Phone-Kyaw M, Alles HK, Mendis KN, et al. Association of high plasma TNF-alpha levels and TNF-alpha/IL-10 ratios with TNF2 allele in severe P. falciparum malaria patients in Sri Lanka. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2013;107:21–29. doi: 10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phawong C, Ouma C, Tangteerawatana P, Thongshoob J, Were T, Mahakunkijcharoen Y, et al. Haplotypes of IL12B promoter polymorphisms condition susceptibility to severe malaria and functional changes in cytokine levels in Thai adults. Immunogenetics. 2010;62:345–356. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0439-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prakash D, Fesel C, Jain R, Cazenave P-A, Mishra GC, Pied S. Clusters of cytokines determine malaria severity in Plasmodium falciparum-infected patients from endemic areas of Central India. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:198–207. doi: 10.1086/504720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rovira-Vallbona E, Moncunill G, Bassat Q, Aguilar R, Machevo S, Puyol L, et al. Low antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum and imbalanced pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with severe malaria in Mozambican children: A case-control study. Malar. J. 2012;11:181. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinha S, Qidwai T, Kanchan K, Jha GN, Anand P, Pati SS, et al. Distinct cytokine profiles define clinical immune response to falciparum malaria in regions of high or low disease transmission. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2010;21:232–240. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2010.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamada-Tanaka MS, De Fatima Ferreira-Da-Cruz M, Das Gracas Alecrim M, Mascarenhas LA, Daniel-Ribeiro CT. Tumor necrosis factor alpha interferon gamma and macrophage stimulating factor in relation to the severity of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Brazilian Amazon. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1995;47:282–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCall MB, Hopman J, Daou M, Maiga B, Dara V, Ploemen I, et al. Early interferon-gamma response against Plasmodium falciparum correlates with interethnic differences in susceptibility to parasitemia between sympatric Fulani and Dogon in Mali. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:142–152. doi: 10.1086/648596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D'Ombrain MC, Robinson LJ, Stanisic DI, Taraika J, Bernard N, Michon P, et al. Association of early interferon-gamma production with immunity to clinical malaria: A longitudinal study among Papua New Guinean children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:1380–1387. doi: 10.1086/592971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dodoo D, Omer FM, Todd J, Akanmori BD, Koram KA, Riley EM. Absolute levels and ratios of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine production in vitro predict clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185:971–979. doi: 10.1086/339408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luty AJ, Perkins DJ, Lell B, Schmidt-Ott R, Lehman LG, Luckner D, et al. Low interleukin-12 activity in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:3909–3915. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.7.3909-3915.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu J, Cao S, Kim S, Chung EY, Homma Y, Guan X, et al. Interleukin-12: an update on its immunological activities, signaling and regulation of gene expression. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2005;1:119–137. doi: 10.2174/1573395054065115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camponovo F, Campo JJ, Le TQ, Oberai A, Hung C, Pablo JV, et al. Proteome-wide analysis of a malaria vaccine study reveals personalized humoral immune profiles in Tanzanian adults. Elife. 2020;9:e53080. doi: 10.7554/eLife.53080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crompton PD, Kayala MA, Traore B, Kayentao K, Ongoiba A, Weiss GE, et al. A prospective analysis of the Ab response to Plasmodium falciparum before and after a malaria season by protein microarray. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6958–6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001323107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiss GE, Traore B, Kayentao K, Ongoiba A, Doumbo S, Doumtabe D, et al. The Plasmodium falciparum-specific human memory B cell compartment expands gradually with repeated malaria infections. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000912. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dent AE, Nakajima R, Liang L, Baum E, Moormann AM, Sumba PO, et al. Plasmodium falciparum protein microarray antibody profiles correlate with protection from symptomatic malaria in Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;212:1429–1438. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doolan DL, Dobano C, Baird JK. Acquired immunity to malaria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22:13–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00025-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Castillo L, MacCallum DM. Cytokine measurement using cytometric bead arrays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;845:425–434. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-539-8_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young SH, Antonini JM, Roberts JR, Erdely AD, Zeidler-Erdely PC. Performance evaluation of cytometric bead assays for the measurement of lung cytokines in two rodent models. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;331:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jimenez R, Ramirez R, Carracedo J, Aguera M, Navarro D, Santamaria R, et al. Cytometric bead array (CBA) for the measurement of cytokines in urine and plasma of patients undergoing renal rejection. Cytokine. 2005;32:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cassatella MA, Bazzoni F, Flynn RM, Dusi S, Trinchieri G, Rossi F. Molecular basis of interferon-gamma and lipopolysaccharide enhancement of phagocyte respiratory burst capability: Studies on the gene expression of several NADPH oxidase components. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:20241–20246. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)30495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bradley LM, Dalton DK, Croft M. A direct role for IFN-gamma in regulation of Th1 cell development. J Immunol. 1996;157:1350–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Snapper CM, Paul WE. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Valente G, Ozmen L, Novelli F, Geuna M, Palestro G, Forni G, et al. Distribution of interferon-gamma receptor in human tissues. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:2403–2412. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoneto T, Yoshimoto T, Wang CR, Takahama Y, Tsuji M, Waki S, et al. Gamma interferon production is critical for protective immunity to infection with blood-stage Plasmodium berghei XAT but neither NO production nor NK cell activation is critical. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:2349–2356. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.5.2349-2356.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoshimoto T, Takahama Y, Wang CR, Yoneto T, Waki S, Nariuchi H. A pathogenic role of IL-12 in blood-stage murine malaria lethal strain Plasmodium berghei NK65 infection. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5500–5505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Favre N, Ryffel B, Bordmann G, Rudin W. The course of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infections in interferon-gamma receptor deficient mice. Parasite Immunol. 1997;19:375–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1997.d01-227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amani V, Vigario AM, Belnoue E, Marussig M, Fonseca L, Mazier D, et al. Involvement of IFN-gamma receptor-medicated signaling in pathology and anti-malarial immunity induced by Plasmodium berghei infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:1646–1655. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1646::AID-IMMU1646>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su Z, Stevenson MM. Central role of endogenous gamma interferon in protective immunity against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:4399–4406. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.8.4399-4406.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Inoue S, Niikura M, Mineo S, Kobayashi F. Roles of IFN-gamma and gammadelta T cells in protective immunity against blood-stage malaria. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:258. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rudin W, Favre N, Bordmann G, Ryffel B. Interferon-gamma is essential for the development of cerebral malaria. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:810–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hunt NH, Ball HJ, Hansen AM, Khaw LT, Guo J, Bakmiwewa S, et al. Cerebral malaria: Gamma-interferon redux. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2014;4:113. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Villegas-Mendez A, Greig R, Shaw TN, de Souza JB, Gwyer Findlay E, Stumhofer JS, et al. IFN-gamma-producing CD4+ T cells promote experimental cerebral malaria by modulating CD8+ T cell accumulation within the brain. J. Immunol. 2012;189:968–979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.King T, Lamb T. Interferon-gamma: The Jekyll and Hyde of malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005118. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ivashkiv LB. IFNgamma: Signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:545–558. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jakobsen PH, McKay V, Morris-Jones SD, McGuire W, van Hensbroek MB, Meisner S, et al. Increased concentrations of interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and decreased concentrations of beta-2-glycoprotein I in Gambian children with cerebral malaria. Infect. Immun. 1994;62:4374–4379. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4374-4379.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maneerat Y, Pongponratn E, Viriyavejakul P, Punpoowong B, Looareesuwan S, Udomsangpetch R. Cytokines associated with pathology in the brain tissue of fatal malaria. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 1999;30:643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.