Abstract

In the present work, cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) were successfully produced from the Pennisetum purpureum (PP) fibers through ammonium persulfate (APS) oxidation. The effect of oxidation temperatures (60, 70, and 80 °C) on the properties of CNCs was characterized. In addition, the influence of CNCs addition (0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 wt%) on the lubrication properties of the base oil SAE 40 lubricant was also investigated. The characteristics of the CNCs were determined by using FT-IR, XRD, TEM, and TGA. The lubrication properties were evaluated using kinematic viscosity and viscosity index measurements. The optimal oxidation temperature was found at 60 °C which resulted in the needle-shaped CNCs particles with high crystallinity (66.56%), an average diameter (15 nm), and an average length (79 nm). The resulting CNCs exhibited higher thermal stability than the PP fibers. Both kinematic viscosity and viscosity index did not significantly change by increasing the CNCs contents. However, a slightly higher viscosity index was exhibited for 0.2 wt% CNCs compared to that of neat base oil SAE 40. The CNCs obtained had high potential as a reinforcing agent of nanocomposites and also as a bio-lubricating additive in engine oil.

Keywords: Pennisetum purpureum fibers, Cellulose nanocrystals, Ammonium persulfate, Lubrication properties

Pennisetum purpureum fibers; Cellulose nanocrystals; Ammonium persulfate; lubrication properties.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, research on the development and fabrication of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) are attracting the attention of many researchers [1, 2, 3, 4]. CNCs are one type of nanomaterials synthesized from cellulose, which has superior characteristics such as nanoscale size, high specific strength and stiffness, high surface area, high crystallinity, renewability, biodegradability, adjustable surface chemistry, non-toxic, enhanced thermal stability, and unique optical behaviors [2, 3, 4]. Because of these unique properties, CNCs have been widely applied in many fields such as reinforcing agents for nanocomposites, enzyme immobilization, drug delivery, biomedical, environmentally friendly catalysis, metallic reaction templates, and bio-lubricant additive [5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Pennisetum purpureum (PP) also referred to as Napier grass, is a species of perennial tropical grass native to the African prairies [10]. PP, which belongs to the Poaceae family, is easy to grow in tropical areas and only requires very few nutritional supplements for growth [11]. P. purpureum is a source of lignocellulosic biomass which is classified as a non-wood cellulose source [12, 13]. PP fiber consists of 46% cellulose, 34% hemicellulose, and 20% lignin [11, 14]. A similar finding was also demonstrated by Nascimento and Rezende [15] where PP fibers were mainly composed of 41.8% cellulose, 24.7% hemicellulose, and 28.0% lignin. Due to the high content of cellulose, PP fibers can be considered for producing CNCs. Studies on CNCs preparation isolated from PP fibers were very limited. Nascimento and Rezende [15] isolated CNCs from PP fibers using sulfuric acid hydrolysis and it was found the CNCs with a 12–16% w/w yield, high crystallinity index (72–77%), and aspect ratios (30–44). Cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) isolated from PP fibers through sulfuric acid hydrolysis assisted by ball milling were demonstrated by previous studies [16] where the optimal concentration of sulfuric acid hydrolysis was obtained at 5.6 M with the highest crystallinity of 70.67% and the best thermal stability. Recently, Sucinda et al. [17] investigated the properties of CNCs fabricated from PP fiber via sulfuric acid hydrolysis under different reaction times. They reported that with increasing reaction time, the crystallinity of the CNCs was increased but the size and thermal resistance of the CNCs were decreased.

To date, the two main approaches used to isolate CNCs from lignocellulosic materials are mechanical and chemical techniques. The high-pressure homogenization [18], high-intensity ultrasonication [19], steam explosion [20], micro fluidization [21], and grinding [22] were examples of mechanical methods whereas the acid hydrolysis [23, 24, 25, 26, 27] and enzymatic hydrolysis methods are chemical method [28]. The most commonly used chemical method is acid hydrolysis using inorganic acids including sulfuric, hydrochloric, and phosphoric acids because of their ease of application and low energy requirements [29]. Nevertheless, acid hydrolysis has some weaknesses including environmental pollution, requiring a lot of water, being highly corrosive, excessive cellulose degradation, the lower thermal resistance of the obtained CNCs, and lower efficiency [30, 31, 32, 33]. Moreover, the acid hydrolysis process requires pre-treatment, so it takes longer and is more expensive [29].

Ammonium persulfate oxidation (APS) is an alternative method to replace acid hydrolysis because it is a simple, one-time process, low toxicity, high solubility, low cost, and without the need for pretreatment to remove non-cellulose and amorphous cellulose components area [25, 27]. In addition, the oxidation of ammonium persulfate (APS) can fabricate carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs–COOH) directly from the cellulose source without any chemical pretreatment as in TEMPO-mediated oxidation, which is often conditioned to CNC sulfate prepared by an acid hydrolysis process [27]. The APS oxidation was extensively applied for the fabrication of CNCs from various natural cellulose resources such as flax, hemp, triticale, microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), Whatman CF1 paper [30], cotton [34, 35], oil palm frond [36], sugarcane bagasse pulp [37], industrial denim waste [38], recycled medium-density fiberboards (MDF) [27], and lemon seeds [25]. So far, no study on the fabrication of CNCs from PP fibers via APS oxidation has been reported.

In recent years, studies on lubricants with nanoparticle additives have received great attention from researchers. This is because the presence of nanoparticle additives in the lubricant has been proven to be effective in reducing friction and wear due to high pressure and temperature [39, 40, 41]. So far, a lot of different types of inorganic nanoparticles including metals (Cu, Fe, Pd), metal oxides (TiO2, SiO2, Al2O3, ZnO) [39, 40, 41], boron-based particles (calcium borate, zinc borate, boric acid) [42, 43], and carbon materials (diamond, graphene, carbon nanotube) in their use as a lubricant additive [44, 45, 46]. However, these inorganic lubricant additives have two drawbacks that limit their application. Firstly, due to their high surface energy, inorganic additives tend to agglomerate which further causes the nanoparticles to be unable to penetrate the contact gaps of the mating surfaces to enhance lubrication properties [47]. The second drawback is the sedimentation of inorganic nanoparticles in the oil due to the higher density of inorganic nanoparticles such as (e.g. Cu 8.9 g/cm3, TiO2 4.2 g/cm3, diamond 3.2 g/cm3) compared to the base oils (0.85–0.95 g/cm3) [48]. Therefore, it needs to substitute inorganic nanoparticles with those from renewable resources due to environmental problems and sustainable development. CNCs are a very potential candidate to substitute inorganic additives in lubricants because of their excellent characteristics including high surface area, colloidal stability, low toxicity, high strength, and high stiffness [49, 50, 51]. To date, there is still little research on the application of CNCs as a lubricant additive. Song et al. [52] reported the lowest viscosity, yield point, and gel strength in the bentonite drilling fluids containing CNCs were found for the smallest CNCs. Ramachandran et al. [53] demonstrated both thermal conductivity and relative viscosity of the ethylene glycol water with nanocellulose were affected strongly by both volume concentration and temperature. Zhang et al. [54] reported that the nanocellulose esters with a high degree of substitution and long-chain substituents produced by the mechanical activation-assisted co-reactant reaction (MACR) technique as eco-friendly additives exhibited better lubricating ability. Recently, Awang et al. [8, 9] studied the effect of adding CNCs into the base oil SAE 40 on the viscosity and tribological properties. They found that the existence of 0.1% CNCs has significantly enhanced the viscosity and tribological performance of the base oil SAE 40.

Based on literature studies, the investigation of CNC production of PP fiber through the APS oxidation technique and its application as a lubricant additive has not yet been studied by previous researchers. In the present study, CNCs were made from PP fibers through the APS oxidation process. The CNCs obtained at different oxidation temperatures were characterized through FT-IR, XRD, TEM, and TGA analysis. In addition, the influence of selected CNCs addition to engine oil SAE 40 on the lubricating properties was characterized by kinematic viscosity and index viscosity.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Napier grass or PP plant used in the present study was Gama Umami PP grass developed by Fahmi et al. [55]. Ammonium persulfate ((NH₄)₂S₂O₈) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (99%) were bought from Merck, USA. CNCs used in this study were isolated from PP fibers using the APS oxidation method as discussed later. Based on our previous studies, it was found the PP fibers consisted of 45.66% cellulose, 33.67% hemicellulose, and 20.60% lignin [56]. This result was comparable with other results demonstrated by Reddy et al. [11] and Haameem et al. [14] where PP fibers were mainly comprised of 46% cellulose, 34% hemicellulose, and 20% lignin. Owing to the high cellulose content and low lignin content, PP fibers were used as cellulose sources for producing CNCs. The SAE 40 engine oil was chosen as the base fluid in this work. SAE 40 had values in kinematic viscosity according to ASTM D445 at 40 and 100 °C were 30.23 and 5.79 mm2/s, respectively. In addition, this lubricant had a viscosity index of 137 (ASTM D2270) and a density of 0.860 g/cm3.

2.2. Extraction of PP fibers

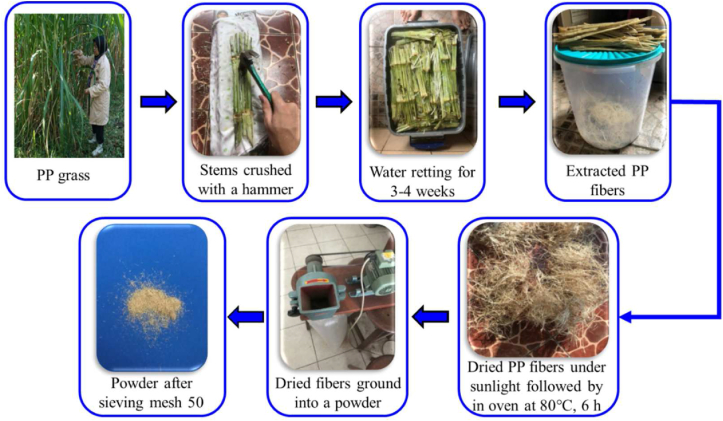

10 kg of PP stems was eliminated from their leaves and roots. The stems were crushed using a hammer so that the deeper stems were exposed and divided into several parts. The crushed stems are then soaked in water by immersion the stems for 3–4 weeks to separate the fibers from the stems more easily. The soaked fibers were cleaned to remove the impurities. The fibers of the PP stems were extracted and sundried for 7 days. The fibers were then dried at 80 °C for 6 h to release the water absorbed in the fiber. The dried fibers were milled and sieved to a size of 50 mesh. The illustration of the extraction process of P. purpureum fibers was presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Extraction process of PP grass fibers.

2.3. Preparation of cellulose nanocrystals

CNCs were produced from the extracted PP fibers by using the APS oxidation method with slight modification according to the previous method [34, 57]. The 1.5 mol/L APS concentration was chosen because our previous studies showed that the 1.5 mol/L APS concentration was the optimal concentration [53]. Concisely, 1 g of PP fiber was put into the 100 mL of 1.5 mol/L APS solution and then stirred using a mechanical stirrer at different oxidation temperatures (60, 70, 80 °C) for 16 h. To stop the reaction, cold distilled water was then added to the reactants. The suspension was mixed with distilled water and then through a centrifugation process with a centrifuge machine at a speed of 4000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was visible after the centrifugation process was complete. The supernatant was then separated from the precipitates. The centrifugation process was repeated until it reached a pH of 4. The CNCs suspension was then homogenized by an ultrasonic homogenizer for 20 min with a power rate of 50%. The suspension was centrifuged again to produce precipitates with a pH of 4. Subsequently, the precipitates were then dialyzed with 1 M NaOH to raise the precipitate pH to 8 for making sure that the suspension did not agglomerate. The suspension was filtrated by a Whatman microfiber filter to separate large cellulose clumps and unreacted fibers. The CNCs suspension was then characterized by TEM. Furthermore, a rotary evaporator was used to reduce the water content in the solution. To produce the dried CNCs powder, the suspension was freeze-dried at −18 °C for 24 h and then characterized by FT-IR, XRD, and TGA. The illustration of the APS oxidation procedure for producing CNCs was presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Preparation of CNCs from PP fibers through APS oxidation method [57].

2.4. Preparation of nano lubricants

Nano lubricants were produced by mixing CNCs with the engine oil (SAE 40) following the procedures reported by Yu and Xie [58] and Awang et al. [8] with a few modifications. The selected CNCs in this study were CNCs obtained from the APS process using an APS concentration of 1.5 mol/L at 70 °C for 16 h, as reported in our previous work [59]. Before use, CNCs were dried at 80 °C for 8 h to release the water absorbed in the CNCs. Nano lubricants were produced by mixing the base oil (SAE 40) with the desired amount of CNCs (0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 wt%). The mixture of oil and CNCs was stirred using a mechanical stirrer at 30 °C for 2 h. This mixture was then homogenized using an ultrasonicator for 2 h to improve the dispersion CNCs within base oil and the stability of the nano lubricant.

2.5. Characterization

2.5.1. Morphological study by SEM/EDS

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JEOL type JSM-6510LA) was used to examine the morphology of the obtained freeze-dried CNCs. The CNCs powder was sputter coated with platinum before observation. The elemental composition of the selected CNC was characterized by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

2.5.2. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis

The morphology and dimensions of CNCs were characterized by a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEM-1400, JEOL Ltd., Japan). 10 μL of CNCs solution was dropped on a copper grid and dried at ambient temperature. The CNCs dimension was measured using the ImageJ software.

2.5.3. Fourier transform-infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

The alteration in the chemical structure of CNCs was evaluated by FT-IR (PerkinElmer, USA) in the spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1.

2.5.4. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

An x-ray diffractometer (Malvern PANalytical, Netherlands) was used to evaluate the crystalline structures of PP fibers and obtained CNCs. The experiment was carried out at a scan speed of 0.1°/min from 10 to 50° with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. The crystallinity index was determined referring to the Segal empirical method [60] as in Eq. (1) below:

| (1) |

where, is the maximum intensity of the (200) lattice diffraction at a 2θ = 22–23° and is the diffraction intensity at a 2θ = 18–19°.

2.5.5. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

A thermogravimetric analyzer (TG/DTA Hitachi STA7300, Japan) was used to evaluate the thermal resistance of the PP fibers and CNCs by recording TG and DTG curves. About 2 mg of CNCs powder was put in an aluminum pan and heated at a uniform heating rate of 10°/min from 30 to 600° under a nitrogen atmosphere.

2.5.6. Kinematic viscosity measurement

Kinematic viscosity measurement of the nano lubricants was performed at 40 and 100 °C following to ASTM D-445 standard. Viscosity was recorded with a temperature-controlled bath of Cannon Instrument Company, USA, Model CT-500 Series II using the Cannon-Fenske Routine Model glass capillary viscometer of Cannon Instrument Company, USA.

2.5.7. Viscosity index measurement

The viscosity of the nano lubricant as a function of the temperature was characterized through the viscosity index (VI) measurement. The value of the VI reference was measured following the ASTM D-2270 standard which referred to the results of the kinematic viscosity measurement. The VI is determined following Eq. (2) below:

| (2) |

where L is the tabulated value, referring to the ASTM D2270, and U and H are the kinematic viscosity of the nano lubricant determined at 40 and 100 °C, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

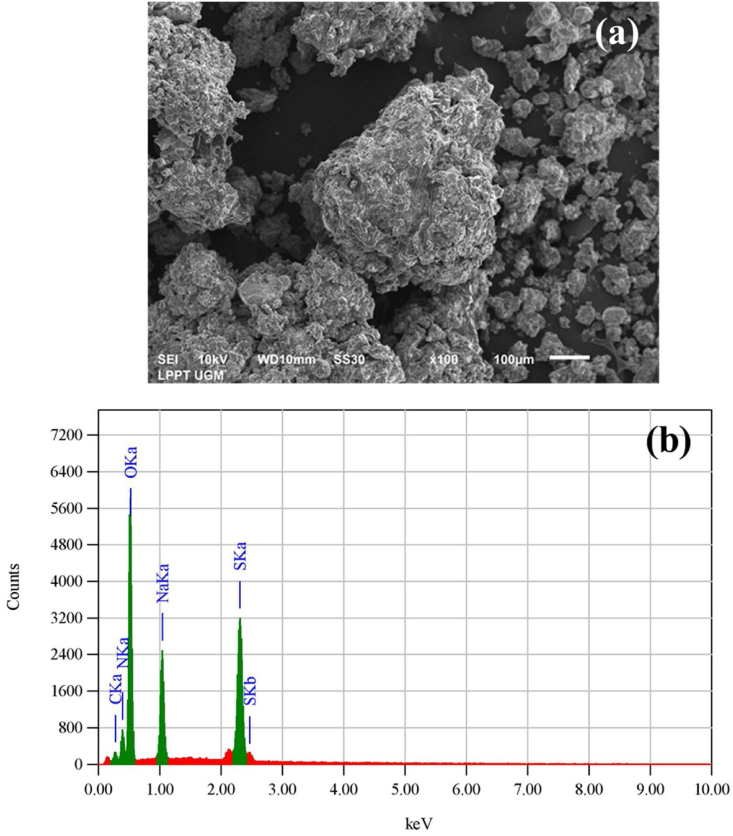

3.1. Morphological analysis by SEM/EDS

Figures 3a and 3b demonstrate the SEM image and its EDS analysis of the selected CNCs, respectively. Figure 3a depicts the SEM micrograph of the CNCs prepared at the oxidation condition of APS concentration of 1.5 mol/L at 70 °C for 16 h. It can be observed that CNCs exhibited irregular forms with various dimensions. The CNCs agglomeration could be observed with big and small sizes. This was attributed to the highly polar surface and hydrophilic nature of the CNCs [61]. The hydrophilic behavior of CNCs was associated with the –OH groups that were located on the CNCs surface [62]. On the other hand, needle-like shapes CNCs that were characteristic of CNCs disappeared. Furthermore, the elemental analysis of the CNCs was performed using EDS diffraction and the results were presented in Table 1. As shown in Figure 3b, the peaks for C, N, O, Na, and S corresponding to their binding energies were observed in the EDS spectrum of CNCs. This result revealed that impurities still existed after the APS oxidation processing. The existence of C and O elements demonstrated the elements present in the CNCs. Furthermore, the presence of N, Na, and S elements was ascribed to residual from the APS oxidation process. This indicated that the APS process has not been carried out perfectly, which was indicated by the presence of N, Na, and S elements. As a result, the characteristic of obtained CNCs was then influenced by the APS oxidation condition.

Figure 3.

(a). SEM image of the selected CNCs (b). EDS diffraction of the CNCs.

Table 1.

Elements present in CNCs.

| Element (wt%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | N | O | Na | S |

| 3.90 | 16.78 | 48.96 | 9.13 | 21.23 |

3.2. TEM analysis

Figure 4 describes the TEM images of the resulting CNCs at various oxidation temperatures. The TEM images of CNCs produced at various temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C were shown in Figures 4a, 4b, and 4c, respectively. All CNCs exhibited a nanometer needle-like shape which was a characteristic feature of CNCs. The diameter and length of the CNCs particles were measured by Image J software from the TEM image (Figure 4) with measurements marked with arrows, and their results were presented in Figure 5. Figures 5a-b show the diameter and length distribution of CNCs produced at 60 °C. Averages of 15 nm in diameter and 79 nm in length were recorded for CNCs prepared at 60 °C. The diameter and length distribution of CNCs fabricated at 70 °C were exhibited in Figure 5c-d and it was obtained at an average of 7.64 nm in diameter and 85 nm in length. Figures 5e-f depict the diameter and length distribution of CNCs made at 80 °C. It was found an average of 6.11 nm in diameter and 86.83 nm in length. From Figure 5, the average diameter of CNCs fabricated at 60, 70, and 80 °C were 15, 7.64, and 6.11 nm, respectively. It is worst interesting to highlight that the average diameter of CNCs was reduced as the oxidation temperature increased. This might be related to the that at higher oxidation temperatures, the oxidation process removed the amorphous regions and some parts of the crystalline regions, which in turn caused a reduction in the diameter of the CNCs [63]. Compared to CNCs prepared at 70 and 80 °C, CNCs produced at 60 °C exhibited the highest average diameter of 15 nm. This was probably attributed to the relatively low oxidation temperature of 60 °C which was relatively incapable of removing amorphous regions such as hemicellulose, lignin, and wax layers which in turn resulted in a relatively larger diameter compared to others.

Figure 4.

TEM images of resulting CNCs at various oxidation temperatures: (a) 60°C (b) 70°C (c) 80°C.

Figure 5.

Diameter and length distribution of resulting CNCs at various oxidation temperatures: (a, b) 60 °C (c, d) 70 °C (e, f) 80 °C.

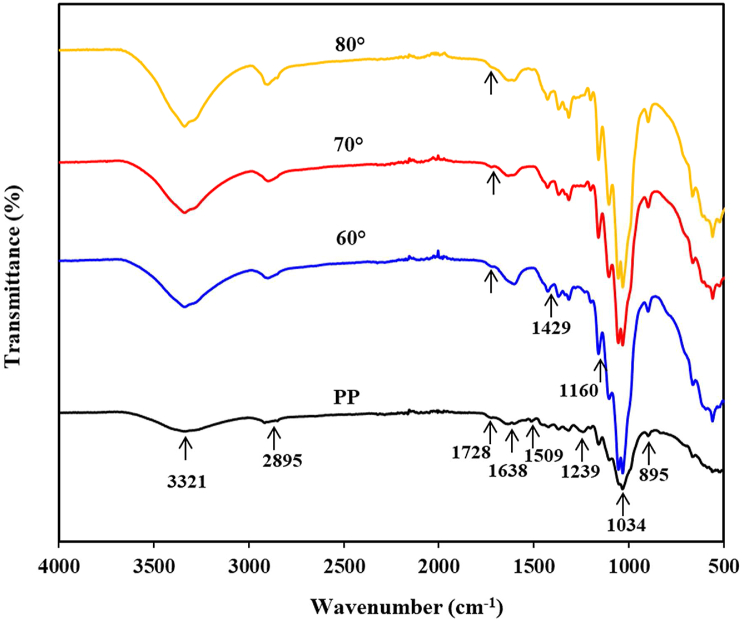

3.3. FT-IR spectroscopy analysis

The FT-IR spectra of PP fibers and CNCs obtained under different oxidation temperatures are depicted in Figure 6. The presence of the stretching vibration of –OH groups in the cellulose was shown by a peak at 3321 cm−1 [35,64,65]. The CH2 symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations was shown a peak at 2895 cm−1 [35,37,64,66,67]. The peak at 1728 cm−1 observed in the PP fibers spectrum corresponded to the stretching vibrations of the C=O groups of acetyl and uronic esters of hemicellulose and ester bonds of carboxyl groups of ferulic and p-coumaric acids of lignin [66, 68, 69]. The peak at 1638 cm−1 presented in PP fibers and CNCs was ascribed to the adsorbed moisture owing to the abundance of hydrophilic hydroxide radicals in the cellulose [70, 71]. The peak at 1509 cm−1 presented in the spectrum of PP fibers was ascribed to the stretching vibrations of the C=C group of aromatic structures in the lignin [72, 73]. The bending vibration of C–O or O–H in the acetyl groups of xylans was indicated by a peak at 1239 cm−1 [74,75]. The three peaks at 1509 and 1239 cm−1 disappeared in the spectra of CNCs indicating that the APS oxidation process successfully removed the amorphous components (hemicellulose and lignin) [76]. The bands at 1034 and 1429 cm−1 were assigned to the C–O–C stretching of pyranose and the CH–bending vibration, respectively [77, 78]. The band that appeared at 1160 cm−1 was ascribed to asymmetric C–O–C bridge stretching [79], respectively. The intensity of the peaks at 1429 and 1160 cm−1 that appeared in the spectra of CNCs was higher after the APS oxidation, suggesting the elimination of amorphous components and then resulting in the increased crystalline cellulose content [27]. As shown in Figure 6, all CNCs exhibited a small peak at 1728 cm−1, indicating the existence of the –COOH groups on the CNCs surfaces because of the carboxylation of cellulose from the oxidative degradation of APS [64]. As shown in Figure 6, all CNCs showed the same spectra indicating no structural changes of the cellulose at various oxidation temperatures. From the FT-IR analysis, it could be resumed that the oxidation temperature had no significant effect on the elimination of amorphous regions in cellulose.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of PP fibers and CNCs obtained with different oxidation temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C.

3.4. XRD analysis

The XRD pattern of PP fibers and all CNCs obtained at various oxidation temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C are depicted in Figure 7. The PP fibers and all CNCs exhibited similar peaks at 2θ = 16, 22, and 35°, indicating the (110), (200), and (004) crystallographic planes of monoclinic cellulose I lattice, respectively [80]. This suggested that the structural characteristics of cellulose I remained unchanged during the APS oxidation process. From Figure 7, it can also be observed that the peak intensity of all CNCs was higher than that of PP fibers. This suggested that all the CNCs had higher crystalline regions than PP fibers, which indicated the elimination of amorphous regions during the APS oxidation. Furthermore, the crystallinity index of CNCs prepared at various temperatures was calculated using the Segal equation (Eq. (1)). The crystallinity index of PP fibers was 40.85% while the crystallinity index of CNCs obtained at various oxidation temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C were 66.56, 63.68, and 65.82%, respectively. This revealed that the crystallinity index of CNCs (63–66%) was higher than that of PP fibers (40.85%). This increase was ascribed to the significant removal of amorphous regions (hemicellulose and lignin) and the decomposition of amorphous regions in PP fibers during the APS oxidation process [35, 37, 64, 67]. This also suggested that the APS oxidation process significantly increased the crystallinity of PP fibers. During APS oxidation, sulfate radical anions (SO42−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydrogen sulfate ions (HSO4−) attacked and infiltrated the more accessible amorphous regions of cellulose, resulting in hydrolytic cleavage of glycosidic bonds and finally producing the individual crystallites [31]. It was further found that the CNCs crystallinity was decreased (from 66.56 to 63.68%) as the oxidation temperature was increased from 60 to 70 °C and then decreased to 65.82% at 80 °C. The highest crystallinity index at 60 °C was ascribed to the most successful elimination of residual amorphous regions within the cellulose exposed to the more crystalline regions of the cellulose fragments for oxidation [27]. The crystallinity of obtained CNCs was higher than those of Khanjanzadeh and Park [27] due to different cellulose resources. All CNCs showed insignificant differences in the crystallinity index values. It was found that the crystallinity index was slightly affected by the oxidation temperature. Under a similar APS oxidation method, the crystallinity of CNCs obtained in this work (66.56%) was higher than that of CNCs isolated from other cellulose resources including oil palm frond (52.4%) [34], balsa (57.6%), and kapok fibers (60.7%) [81], and recycled medium-density fiberboard (63%) [27]. Nevertheless, the crystallinity of obtained CNCs was still lower than that of CNCs isolated from other cellulose resources including bamboo (69.8%) [67], Miscanthus x. Giganteus (70%) [82], lemon seeds (74.4%) [25], sugarcane bagasse (76.5%) [37], and industrial denim waste (83%) [38], and the cotton liner (93.5%) [35]. The resulting CNCs had a higher crystallinity index (66.56%) compared to the TEMPO-mediated oxidation of bagasse (40%) and lemon seeds (66.14%) as demonstrated by other studies [25, 37].

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of PP fibers and CNCs fabricated at various oxidation temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C.

3.5. Thermogravimetry analysis

The TGA and DTG curves of PP fibers and CNCs prepared by the APS oxidation under different temperatures are displayed in Figures 8a and 8b, respectively. The onset (Tonset) and maximum decomposition temperatures (Tmax) and the residual weight values (Wresidue) are presented in Table 2. As shown in Figure 8a, all samples showed similar curves with three degradation steps. In the first step (30–100 °C), the early weight loss (8–20%) was shown by all samples related to the evaporation of the absorbed water [83]. Furthermore, the second degradation step associated with a large weight loss occurred in the temperature ranges of 200–400 °C due to the decomposition of cellulose [27]. The destruction of the cellulose chains by the sequence of cellulose chain depolymerization and dehydration reactions, and the concurrent decomposition of glycosyl unit in the cellulose chains might be believed to be responsible for the large weight loss at temperature ranges of 200–400 °C [84]. All samples exhibited a third degradation step (above 400 °C) which could be ascribed to oxidation and degradation or the breaking of short-chain residues and converting them to lower molecular weight volatile products [85, 86].

Figure 8.

TGA (a) and DTG (b) curves of PP fibers and CNCs at various oxidation temperatures.

Table 2.

Thermal characteristics of PP fibers and CNCs at various oxidation temperatures.

| Sample | Tonset |

Tmax1 |

Tmax2 |

Tmax3 |

Wresidue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (%) | |

| PP fibers | 266.7 | - | - | 330.9 | 19 |

| CNCs 60 °C | 210.0 | 238.3 | 393.5 | 439.0 | 35 |

| CNCs 70 °C | 214.8 | 256.0 | 412.0 | 455.2 | 36 |

| CNCs 80 °C | 208.0 | 236.2 | - | 388.3 | 38 |

As can be seen from Table 2, the onset degradation temperature (Tonset) of PP fibers was 266.7 °C while the Tonset values of CNCs produced under different temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C were 210, 214.8, and 208 °C, respectively. All CNCs showed a lower Tonset compared to PP fibers indicating lower thermal stability. This was ascribed to the influence of the high surface area of the CNCs leading to a longer surface exposure to heat. In addition, the presence of carboxyl groups on the surface could further decrease the thermal resistance of the CNCs [87]. Moreover, the lower Tonset of CNCs compared to that of PP fibers was associated with to decarboxylation of sodium anhydroglucuronate units and the degradation of cellulose [88]. This finding was in good agreement with previous works [89]. From Table 2, it was found that the third peak (Tmax3) of thermal degradation of PP fibers occurred at 330.9 °C, while all CNCs demonstrated Tmax3 range values of 388.3–455.2 °C. This indicated that all CNCs showed higher maximum degradation temperature compared to PP fibers, indicating the higher thermal stability of CNCs. This was related to the tangling effect of flexible CNCs [90] and the removal of both hemicelluloses and lignin, and the higher crystallinity of the CNCs [91, 92]. From Table 2, the CNCs obtained at 70 °C exhibited the highest Tmax3 value among all CNCs. Thus, the best thermal resistance was shown by the CNCs obtained at 70 °C. From Table 2, the final char residue at 600 °C was 19% for PP fibers, 35% for CNC prepared at 60 °C, 36% for CNCs at 70 °C, and 38% for CNCs at 80 °C, respectively. This suggested that all CNCs exhibited much higher residue compared with PP fibers. The higher char residue of all CNCs was attributed to the high crystallinity of the CNCs and the increased portion of added carbon and sodium hydroxide in the APS oxidation. Moreover, the presence of groups of sodium carboxylate on the surfaces of CNCs could act as fire retardants [64, 93, 94]. Similar observations were also found by Khanjanzadeh and Park [27] where all CNCs fabricated by APS oxidation exhibited higher char residue at 600 °C. Based on these studies, it could be concluded the highest thermal stability was obtained at 70 °C.

3.6. Kinematic viscosity

Kinematic viscosity is a measure of the internal resistance of a fluid to flow under the force of gravity. Kinematic viscosity is very important to characterize a lubricant’s ability to effectively lubricate the contact surfaces. The lubricant viscosity is greatly affected by the working temperature. In this study, the kinematic viscosities of the nano lubricant were determined at 40 and 100 °C. Figure 9 displays the variations of the kinematic viscosity with temperatures of 40 and 100 °C at different weight fraction contents of CNCs. As can be seen in Figure 9, it was found that the kinematic viscosity of the nano lubricants was decreased with increasing temperature. This reduction was attributed to the weakening of intermolecular forces of attraction at higher temperatures which allowed faster movement of the suspended particles in the nano-lubricant which further resulted in less resistance overall to movement [95]. This suggested the reduced kinematic viscosity of the nano lubricant when the temperature increased. These were in agreement with previous results demonstrated by Awang et al. [8] where the kinematic viscosity of the nano lubricant based on SAE 40 containing different CNCs was decreased when the temperature increased from 40 to 100 °C. Awang et al. [8] isolated CNCs from the acetate-grade dissolving pulp extracted from the Western Hemlock plant. For all CNCs contents, the kinematic viscosity of the nano lubricant at 40 °C in this study was higher than reported by Awang et al. [8] due to the different CNCs used. From Figure 9, it can also be observed that the kinematic viscosity of all the samples containing CNCs showed a slightly smaller value compared to that of the base oil, SAE 40. This indicated that the presence of CNCs reduced slightly the kinematic viscosity of the lubricant. When a low concentration of CNCs was introduced into the oil, some was deposited between the oil layers which caused to ease of movement of the fluid layers over each other and then a slight reduction in kinematic viscosity [8].

Figure 9.

Kinematic viscosity of base oil SAE 40 and nano lubricant containing different CNCs contents at 40 and 100 °C.

3.7. Viscosity index

The viscosity index was obtained by measuring the kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and 100 °C according to the ASTM D-2270 standard. Table 3 demonstrates the VI value at different contents of CNCs with the base oil, SAE 40. The introduction of CNCs to base oil SAE 40 slightly increased the VI and the highest VI (103.06) was obtained at 0.2% CNCs. Moreover, the VI increased with an increase in the CNCs content. This was associated with the fact that the internal shear stress of the nano lubricant improved with increasing the CNCs content due to an increase in internal friction of the nano lubricant that could resist more against flowing [96]. The enhanced VI of the nano lubricant with an increase in the CNCs concentration was also demonstrated by Awang et al [8] where the highest VI was achieved at 0.1% CNCs content with a VI of 155.32 °C. This revealed that the VI in this study was lower compared with Awang et al. [8] results. This was associated with the difference in the characteristic of base oil used and cellulose resources. Similar results were also presented by Nadooshan et al. [96] where the VI of the nano lubricant was enhanced with an increase in SiO2 multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) nanoparticles. Li et al. [97] also found that adding modified CNCs into the polyalphaolefin (PAO) base oil increased the viscosity and its increase became more and clearer with increasing CNCs concentrations. Viscosity was influenced by several factors such as size, shape, type, and concentrations of nanoparticles, and also nano lubricant preparation [98, 99]. According to Nguyen et al. [100] and Agarwal et al. [101], smaller-size nanoparticles resulted in low viscosity value due to less interface resistance occurring in small-sized particles which is responsible for low viscosity.

Table 3.

Viscosity Index (VI) of base oil SAE 40 and CNCs blended lubricant.

| Sample | SAE 40 | 0.05% CNCs | 0.1% CNCs | 0.2% CNCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity index | 102.16 | 102.85 | 102.62 | 103.06 |

4. Conclusion

CNCs have been successfully isolated from the PP fibers through the APS oxidation technique. The properties of CNCs were affected by the oxidation temperature. The resulting CNCs exhibited much higher crystallinity and thermal stability compared with PP fibers. The optimal oxidation temperature was achieved at 60 °C resulting in the CNCs with a crystallinity of 66.56%, an average diameter of 15 nm, 79 nm in length, and a maximum degradation temperature of 439 °C. The crystallinity index of CNCs did not change with increasing oxidation temperature. The kinematic viscosity of base oil SAE 40 was slightly decreased with increasing the CNCs concentrations and also decreased drastically with increasing temperature. Furthermore, the viscosity index was increased slightly with the increase in CNCs concentrations. It could be concluded that CNCs fabricated with the APS oxidation had a high potential both as a filler for nanocomposite reinforcement and also as an environmentally friendly base oil lubricant additive.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Rajendra Aryasena: Conceived and design the experiments; Performed the experiments.

Kusmono: Analyzed and interpreted data; Wrote the paper.

Nafiatul Umami: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Universitas Gadjah Mada (14543/UN1.FTK/SK/HK/2021).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Lim Wei-Lun, Gunny A.A.N., Kasim F.H., Gopinath S.C.B., Kamaludin N.H.I., Arbain D. Cellulose nanocrystals from bleached rice straw pulp: acidic deep eutectic solvent versus sulphuric acid hydrolyses. Cellulose. 2021;28:6183–6199. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habibi Y., Lucia L.A., Rojas O.J. Cellulose nanocrystals: chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:3479–3500. doi: 10.1021/cr900339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moon R.J., Martini A., Nairn J., Simonsen J., Youngblood J. Cellulose nanomaterials review: structure, properties and nanocomposites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:3941–3994. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00108b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csiszar E., Kalic P., Kobol A., Eduardo de Paulo F. The effect of low frequency ultrasound on the production and properties of nanocrystalline cellulose suspensions and films. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;31:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klemm D., Kramer F., Moritz S., Lindstrom T., Ankerfors M., Gray D., Dorris A. Nanocelluloses: a new family of nature-based materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50(24):5438–5466. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng B.L., Dhar N., Liu H.L., Tam K.C. Chemistry and applications of nanocrystalline cellulose and its derivatives: a nanotechnology perspective. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2011;89(5):1191–1206. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin N., Huang J., Dufresne A. Preparation, properties and applications of polysaccharide nanocrystals in advanced functional nanomaterials: a review. Nanoscale. 2012;4(11):3274–3294. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30260h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awang N.W., Ramasamy D., Kadirgama K., Samykano M., Najafi G., Sidik N.A.C. An experimental study on characterization and properties of nano lubricant containing cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2019;130:1163–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Awang N.W., Ramasamy D., Kadirgama K., Najafi G., Sidik N.A.C. Study on friction and wear of cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) nanoparticle as lubricating additive in engine oil. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2019;131:1196–1204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakar N.A.A., Sultana M.T.H., Aznic M.E., Hazwan M.H., Ariffina A.H. Extraction and surface characterization of novel bast fibers extracted from the Pennisetum Purpureum plant for composite application. Mater. Today Proc. 2018;5:21926–21935. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy K.O., Maheswari C.U., Shukla M., Rajulu A.V. Chemical composition and structural characterization of napier grass fibers. Mater. Lett. 2012;67:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revati R., Abdul Majid M.S., Ridzuan M.J.M., Normahira M., Mohd Nasir N.F., Cheng E.M. Biodegradation of PLA-Pennisetum purpureum based biocomposite scaffold. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017;908(1) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revati R., Majid M.S.A., Ridzuan M.J.M., Basaruddin K.S., Rahman Y.M.N., Cheng E.M., Gibson A.G. Vitro degradation of a 3D porous Pennisetum purpureum/PLA biocomposite scaffold. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017;74:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haameem M., Majid M.S.A., Afendi M., Marzuki H.F.A., Hilmi E.A., Fahmi I., Gibson A.G. Effects of water absorption on Napier grass fibre/polyester composites. Compos. Struct. 2016;144:138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nascimento S.A., Rezende C.A. Combined approaches to obtain cellulose nanocrystals, nanofibrils and fermentable sugars from elephant grass. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;180:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majid R.M.S.A., Jamir M.R.M., Jawaid M., Sultan M.T.H., Tahir M.F.M. Structural, Morphological and thermal properties of cellulose nanofibers from Napier fiber (Pennisetum purpureum) Materials. 2020;13:4125. doi: 10.3390/ma13184125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sucinda E.F., Abdul Majid M.S., Ridzuan M.J.M., Sultan M.T.H., Gibson A.G. Analysis and physicochemical properties of cellulose nanowhiskers from Pennisetum purpureum via different acid hydrolysis reaction time. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;155:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonoobi M., Oladi R., Davoudpour Y., Oksman K., Dufresne A., Hamzeh Y., Davoodi R. Different preparation methods and properties of nanostructured cellulose from various natural resources and residues: a review. Cellulose. 2015;22(2):935–969. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W., Yue J.Q., Liu S.X. Preparation of nanocrystalline cellulose via ultrasound and its reinforcement capability for poly(vinyl alcohol) composites. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19(3):479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherian B.M., Leão A.L., de Souza S.F., Thomas S., Pothan L.A., Kottaisamy M. Isolation of nanocellulose from pineapple leaf fibres by steam explosion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010;81(3):720–725. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan A., Vu K.D., Chauve G., Bouchard J., Riedl B., Lacroix M. Optimization of microfluidization for the homogeneous distribution of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) in biopolymeric matrix. Cellulose. 2014;21:3457–3468. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavoine N., Desloges I., Dufresne A., Bras J. Microfibrillated cellulose-Its barrier properties and applications in cellulosic materials: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;90:735–764. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai H., Ou S., Huang Y., Huang H. Utilization of pineapple peel for production of nanocellulose and film application. Cellulose. 2018;25:1743–1756. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusmono, Listyanda R., Wildan M.W., Ilman M.N. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystal extracted from ramie fibers by sulfuric acid hydrolysis. Heliyon. 2020;6(11) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Chen Y., Wang S., Ma L., Yu Y., Dai H., Zhang Y. Extraction and comparison of cellulose nanocrystals from lemon (Citrus limon) seeds using sulfuric acid hydrolysis and oxidation methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;238 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon G., Lee K., Kim D., Jeon Y., Kim Ung-Jin, You J. Cellulose nanocrystal-coated TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofiber films for high performance all-cellulose nanocomposites. J. Hazard Mater. 2020;398 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khanjanzadeh H. Byung-Dae Park, Optimum oxidation for direct and efficient extraction of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals from recycled MDF fibers by ammonium persulfate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribeiro R.S.A., Pohlmann B.C., Calado V., Bojorge N., Pereira N., Jr. Production of nanocellulose by enzymatic hydrolysis: trends and challenges. Eng. Life Sci. 2019;19:279–291. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201800158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espino E., Cakir M., Domenek S., Romaán-Gutieárrez A.D., Belgacem N., Bras J. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from industrial by-products of Agave tequilana and barley. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014;62:552–559. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung A.C.W., Hrapovic S., Lam E., Liu Y., Male K.B., Mahmoud K.A., Luong J.H.T. Characteristics and properties of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals prepared from a novel one-step procedure. Small. 2011;7(3):302–305. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du H., Liu C., Mu X., Gong W., Lv D., Hong Y., Si C., Li B. Preparation and characterization of thermally stable cellulose nanocrystals via a sustainable approach of FeCl3-catalyzed formic acid hydrolysis. Cellulose. 2016;23:2389–2407. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bashar M.M., Zhu H., Yamamoto S., Mitsuishi M. Highly carboxylated and crystalline cellulose nanocrystals from jute fiber by facile ammonium persulfate oxidation. Cellulose. 2019;26:3671–3684. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji H., Xiang Z., Qi H., Han T., Pranovich A., Song T. Strategy towards one-step preparation of carboxylic cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibrils with high yield, carboxylation and highly stable dispersibility using innocuous citric acid. Green Chem. 2019;21:1956–1964. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mascheroni E., Rampazzo R., Ortenzi M.A., Piva G., Bonetti S., Piergiovanni L. Comparison of cellulose nanocrystals obtained by sulfuric acid hydrolysis and ammonium persulfate, to be used as coating on flexible food-packaging materials. Cellulose. 2016;23:779–793. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oun A.A., Rhim Jong-Whan. Characterization of carboxymethyl cellulose-based nanocomposite films reinforced with oxidized nanocellulose isolated using ammonium persulfate method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;174:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaini L.H., Febrianto F., Wisata N.J., Maulana M.M.I., Lee S.H., Kim N.H. Effect of ammonium persulfate concentration on characteristics of cellulose nanocrystals from oil palm frond. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2019;47(5):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang K., Sun P., Liu H., Shang S., Song J., Wang D. Extraction and comparison of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals from bleached sugarcane bagasse pulp using two different oxidation methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;138:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culsum N.T.U., Melinda C., Leman I., Wibowo A., Budhi Y.W. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) from industrial denim waste using ammonium persulfate. Mater. Today Commun. 2021;26 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang H., Li Z.Y., Kao M.J., Huang K.D., Wu H.M. Tribological property of TiO2 nano lubricant on piston and cylinder surfaces. J. Alloys Compd. 2010;495(2):481–484. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo T., Wei X., Huang X., Huang L., Yang F. Tribological properties of Al2O3 nanoparticles as lubricating oil additives. Ceram. Int. 2014;40(5):7143–7149. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohamad A.T., Kaur J., Sidik N.A.C., Rahman S. Nanoparticles: a review on their synthesis, characterization and physicochemical properties for energy technology industry. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2018;46(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao G., Zhao Q., Li W., Wang X., Liu W. Tribological properties of nanocalcium borate as lithium grease additive. Lubric. Sci. 2014;26(1):43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao C., Jiao Y., Chen Y.K., Ren G. The tribological properties of zinc borate ultrafine powder as a lubricant additive in sunflower oil. Tribol. Trans. 2014;57(3):425–434. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Z., Liu Y.H., Luo J.B. Superlubricity of nanodiamonds glycerol colloidal solution between steel surfaces. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016;489:400–406. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin J.S., Wang L.W., Chen G.H. Modification of graphene platelets and their tribological properties as a lubricant additive. Tribol. Lett. 2011;41(1):209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afrand M., Najafabadi K.N., Akbari M. Effects of temperature and solid volume fraction on viscosity of SiO2-MWCNTs/SAE40 hybrid nanofluid as a coolant and lubricant in heat engines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016;102:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalin M., Kogovsek J., Remskar M. Mechanisms and improvements in the friction and wear behavior using MoS2 nanotubes as potential oil additives. Wear. 2012;280:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gulzar M., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Varman M., Zulkifli N.W.M., Mufti R.A., Zahid R., Yunus R. Dispersion stability and tribological characteristics of TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite-enriched biobased lubricant. Tribol. Trans. 2017;60(4):670–680. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pei A., Zhou Q., Berglund L.A. Functionalized cellulose nanocrystals as biobased nucleation agents in poly(l-lactide) (PLLA) – crystallization and mechanical property effects. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010;70(5):815–821. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klemm D., Kramer F., Moritz S., Lindström T., Ankerfors M., Gray D., Dorris A. Nanocelluloses: a new family of nature-based materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50(24):5438–5466. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goikuria U., Larrañaga A., Vilas J.L., Lizundia E. Thermal stability increase in metallic nanoparticles-loaded cellulose nanocrystal nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;171:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song K., Wu Q., Li Mei-Chun, Wojtanowicz A.K., Dong L., Zhang X., Ren S., Lei T. Performance of low solid bentonite drilling fluids modified by cellulose nanoparticles. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016;34:1403–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramachandran K., Kadirgama K., Ramasamy D., Azmi W.H., Tarlochan F. Investigation on effective thermal conductivity and relative viscosity of cellulose nanocrystal as a nanofluidic thermal transport through a combined experimental-Statistical approach by using Response Surface Methodology. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017;122:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y., Wei L., Hu H., Zhao Z., Huang Z., Huang A., Shen F., Liang J., Qin Y. Tribological properties of nano cellulose fatty acid esters as ecofriendly and effective lubricant additives. Cellulose. 2018;25(5):3091–3103. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fahmi M., Utomo R., Suhartanto B., Astutid A., Umami N. Chemical quality and digestibility value in silage of Pennisetum purpuphoides and Pennisetum purpureum Gamma with different levels of molasses supplementation. Key Eng. Mater. 2021;884:204–211. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aryasena R. Universitas Gadjah Mada; 2021. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC) from Pennisetum Purpureum Stems via Ammonium Persulfate Oxidation Method. Master Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Indirasetyo N.L., Kusmono Isolation and properties of cellulose nanocrystals fabricated by ammonium persulfate oxidation from Sansevieria trifasciata fibers. Fibers. 2022;10(61):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu W., Xie H. A review on nanofluids: preparation, stability mechanisms, and applications. J. Nanomater. 2012;2012 [Google Scholar]

- 59.R. Aryasena, Kusmono, Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) from Pennisetum purpureum stems via ammonium persulfate oxidation, International Conference on Communication, Economics, Education, Law, Social, Science and Technology, 23 September 2021, Pekanbaru, Indonesia.

- 60.Segal L., Creely J.J., Martin A.E., Conrad C.M. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-Ray Diffractometer. Textil. Res. J. 1959;29:786–794. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eichhorn S.J., Dufresne A., Aranguren M., Marcovich N.E., Capadona J.R., Rowan S.J., Weder C., Thielemans W., Roman M., Renneckar S., Gindl W., Veigel S., Keckes J., Yano H., Abe K., Nogi M., Nakagaito A.N., Mangalam A., Simonsen J., Benight A.S., Bismarck A., Berglund L.A., Peijs T. Review: current international research into cellulose nanofibres and nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci. 2010;45(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu W., Chen S., Xu Q., Wang H. Solvent-free acetylation of bacterial cellulose under moderate conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011;83(4):1575–1581. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Dulaimi A.A., Wanrosli W.D. Isolation and characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose from totally chlorine free oil palm empty fruit bunch pulp. J. Polym. Environ. 2017;25:192–202. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng M., Qin Z., Liu Y., Qin Y., Li T., Chen L., Zhu M. Efficient extraction of carboxylated spherical cellulose nanocrystals with narrow distribution through hydrolysis of lyocell fibers by using ammonium persulfate as an oxidant. J. Mater. Chem. 2014;2:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robles E., Urruzola I., Labidi J., Serrano L. Surface-modified nano-cellulose as reinforcement in poly(lactic acid) to conform new composites. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015;71:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goh K.Y., Ching Y.C., Chuah C.H., Abdullah L.C., Liou N.S. Individualization of microfibrillated celluloses from oil palm empty fruit bunch: comparative studies between acid hydrolysis and ammonium persulfate oxidation. Cellulose. 2016;23(1):379–390. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu Y., Tang L., Lu Q., Wang S., Chen X., Huang B. Preparation of cellulose nanocrystals and carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals from borer powder of bamboo. Cellulose. 2014;21(3):1611–1618. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fortunati E., Benincasa P., Balestra G.M., Luzi F., Mazzaglia A., Del Buono D., Pugliaa D., Torre L. Revalorization of barley straw and husk as precursors for cellulose nanocrystals extraction and their effect on PVA_CH nanocomposites. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016;92:201–217. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hafemann E., Battisti R., Marangoni C., Machado R.A.F. Valorization of royal palm tree agroindustrial waste by isolating cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;218(2019):188–198. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang J., Han C.R., Xu F., Sun R.C. Simple approach to reinforce hydrogels with cellulose nanocrystals. Nanoscale. 2014;6:5934–5943. doi: 10.1039/c4nr01214c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luzi F., Puglia D., Sarasini F., Tirill`o J., Maffei G., Zuorro A., Lavecchia R., Kenny J.M., Torre L. Valorization and extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from North African grass: mpelodesmos mauritanicus (Diss) Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;209:328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gelbrich J., Mai C., Militz H. Evaluation of bacterial wood degradation by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) measurements. J. Cult. Herit. 2012;13(3):S135–S138. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moosavinejad S.M., Madhoushi M., Vakili M., Rasouli D. Evaluation of degradation in chemical compounds of wood in historical buildings using FT-IR and FT-Raman vibrational spectroscopy. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2019;21(3):381–392. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peng F., Ren J.L., Xu F., Bian J., Peng P., Sun R.C. Comparative study of hemicelluloses obtained by graded ethanol precipitation from sugarcane bagasse. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57(14):6305–6317. doi: 10.1021/jf900986b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun D., Sun S.C., Wang B., Sun S.F., Shi Q., Zheng L., Wang Shuang-Fei, Lieu Shi-Jie, Lia Ming-Fei, Cao Xue-Fei, Sun Shao-Ni. Run-Cang Sun, Effect of various pretreatments on improving cellulose enzymatic digestibility of tobacco stalk and the structural features of co-produced hemicelluloses. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;297 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaffashsaie E., Yousefi H., Nishino T., Matsumoto T., Mashkour M., Madhoushi M., Kawaguchi H. Direct conversion of raw wood to TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;262 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu Y., Liu L., Wang K., Zhang H., Yuan Y., Wei H.X., Wang X., Duan Y., Zhuo L., Zhang J. Modified ammonium persulfate oxidations for efficient preparation of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;229 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Y.W., Lee H.V., Juan J.C., Phang Siew-Moi. Production of new cellulose nanomaterial from red algae marine biomass Gelidium elegans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;151:1210–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poletto M., Pistor V., Zeni M., Zattera A.J. Crystalline properties and decomposition kinetics of cellulose fibers in wood pulp obtained by two pulping processes. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2011;96(4):679–685. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun X., Wu Q., Ren S., Lei T. Comparison of highly transparent all-cellulose nanopaper prepared using sulfuric acid and TEMPO-mediated oxidation methods. Cellulose. 2015;22:1123–1133. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marwanto M., Maulana M.I., Febrianto F., Wistara N.J., Nikmatin S., Masruchin N., Zaini L.H., Lee S.H., Kim N.H. Effect of oxidation time on the properties of cellulose nanocrystals prepared from Balsa and Kapok fibers using ammonium persulfate. Polymers. 2021;13(11):1894. doi: 10.3390/polym13111894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang H., Zhang Y., Kato R., Rowan S.J. Preparation of cellulose nanofibers from Miscanthus x. Giganteus by ammonium persulfate oxidation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;212:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khanjanzadeh H., Behrooz R., Bahramifar N., Gindl-Altmutter W., Bacher M., Edler M., Griessere T. Surface chemical functionalization of cellulose nanocrystals by 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;106:1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roman M., Winter W.T. Effect of sulfate groups from sulfuric acid hydrolysis on the thermal degradation behavior of bacterial cellulose. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(5):1671–1677. doi: 10.1021/bm034519+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Devi R.R., Dhar P., Kalamdhad A., Katiyar V. Fabrication of cellulose nanocrystals from agricultural compost. Compost Sci. Util. 2015;23(2):104–116. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khanjanzadeh H., Behrooz R., Bahramifar N., Pinkl S., Gindl-Altmutter W. Application of surface chemical functionalized cellulose nanocrystals to improve the performance of UF adhesives used in wood-based composites-MDF type. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;206:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pacheco C.M., Bustos C.A., Reyes G. Cellulose nanocrystals from blueberry pruning residues isolated by ionic liquids and TEMPO-oxidation combined with mechanical disintegration. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2020;41(11):1731–1741. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhong T., Dhandapani R., Liang D., Wang J., Wolcott M.P., Fossen D.V., Liu H. Nanocellulose from recycled indigo-dyed denim fabric and its application in composite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;240 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tanpichaia S., Wimolmala E. Facile single-step preparation of cellulose nanofibers by TEMPO-mediated oxidation and their nanocomposites. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maiti S., Jayaramudu J., Das K., Reddy S.M., Sadiku R., Ray S.S., Liu D. Preparation and characterization of nano-cellulose with new shape from different precursor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;98(1):562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sain M., Panthapulakkal S. Bioprocess preparation of wheat fiber and characterization. Industrial Crop Production. 2006;23:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alemdar A., Sain M. Isolation and Characterization of nanofibers from agricultural residues-wheat straw and soy hulls. Bioresour. Technol. 2008;99:1664–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jiang H., Wu Y., Han B., Zhang Y. Effect of oxidation time on the properties of cellulose nanocrystals from hybrid poplar residues using the ammonium persulfate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;174:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oun A.A., Rhim Jong-Whan. Preparation of multifunctional carboxymethyl cellulose-based films incorporated with chitin nanocrystal and grapefruit seed extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;152:1038–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Abdolbaqi M.K., Azmi W.H., Mamat R., Sharma K.V., Najafi G. Experimental investigation of thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity of Bio Glycolwater mixture based Al2O3 nanofluid. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016;102:932–941. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nadooshan A.A., Hemmat Esfe M., Afrand M. Evaluation of rheological behavior of 10W40 lubricant containing hybrid nanomaterial by measuring dynamic viscosity. Phys. E Low-Dimension. Syst. Nanostruct. 2017;92:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li K., Zhang X., Du C., Yang J., Wu B., Guo Z., Dong C., Lin N., Yuan C. Friction reduction and viscosity modification of cellulose nanocrystals as biolubricant additives in polyalphaolefin oil. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;220:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Timofeeva E.V., Moravek M.R., Singh D. Improving the heat transfer efficiency of synthetic oil with silica nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;364(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wei B., Zou C., Yuan X., Li X. Thermo-physical property evaluation of diathermic oil-based hybrid nanofluids for heat transfer applications. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2017;107:281–287. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nguyen C.T., Desgranges F., Roy G., Galanis N., Maré T., Boucher S., Mintsa H.A. Temperature and particle-size dependent viscosity data for water-based nanofluids-hysteresis phenomenon. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 2007;28(6):1492–1506. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Agarwal D.K., Vaidyanathan A., Kumar S.S. Synthesis and characterization of kerosene–alumina nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013;60:275–284. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.