Abstract

Background

Finasteride is widely used in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and androgenic alopecia (AGA). Post-finasteride syndrome (PFS) is a spectrum of persistent symptoms reported by some patients after treatment with finasteride for androgenetic alopecia. These patients show many abnormal clinical manifestations, including psychological disorders (depression and anxiety, among others) and sexual dysfunction. However, there is insufficient research on the persistent severe side effects in young male patients with PFS, and the underlying mechanism of PFS has not been fully elucidated. Growing evidence highlights the relevance of genetic variants and their associated responses to drugs. Therefore, we performed next-generation sequencing (NGS) in our study of PFS.

Case Description

Here, we enrolled three young male patients aged 20–30 years with a PFS duration of 1–3 years and analyzed their clinical and genetic information. PFS patients suffered from erectile dysfunction (ED), anxiety, feelings of isolation, and insomnia. Variants in genes, including CA8, VSIG10L2, HLA-B, KRT38 and HLA-DRB1, were detected, and these genes represent potential risk genes.

Conclusions

PFS, commonly observed in young men, has certain clinical manifestations, mainly psychological disorders and abnormal sexual functions. Young men who may take finasteride therapy for hair loss should receive consultation services and be informed of possible future harms. Psychological screening is an important method to reduce the occurrence of PFS. At present, the underlying mechanism of PFS is not very clear, and more research is needed to improve the understanding of the disease. Some genes are abnormal in PFS patients, suggesting that clinical and genetic evaluation might be needed before the prescription of 5α-reductase inhibitors. With research progress, genetic screening may be a promising way to avoid the harmful effects of finasteride in people with related genetic risk factors.

Keywords: Androgenic alopecia (AGA), sexual dysfunction, depression, post-finasteride syndrome (PFS), case report

Introduction

Finasteride is a synthetic 5α-reductase inhibitor that effectively reduces dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the blood and prostate by inhibiting the conversion of testosterone into DHT (1-5). Finasteride is widely used in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and androgenic alopecia (AGA). The effectiveness and safety of finasteride in the treatment of BPH have been extensively studied; however, there is insufficient research on the persistent severe side effects in young male patients with AGA who discontinue the drug (6-16). This study reports three cases of post-finasteride syndrome (PFS) occurring in young men after finasteride was used to treat hair loss. We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-22-92/rc).

Case presentation

PFS patients were recruited from the clinic of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) between Dec 2019 and Nov 2021. The diagnosis of PFS was made by experienced doctors according to the medical history, complaints, and physical and laboratory examination results. Three healthy men aged 22–23 years who reported persistent sexual and mental health side effects after the daily use of finasteride (i.e., Propecia, Proscar, or generic finasteride) for androgenetic alopecia were considered in the case group. An age-matched healthy volunteer was recruited from PUMCH. The patients and healthy volunteer enrolled were all of Han Chinese ethnicity.

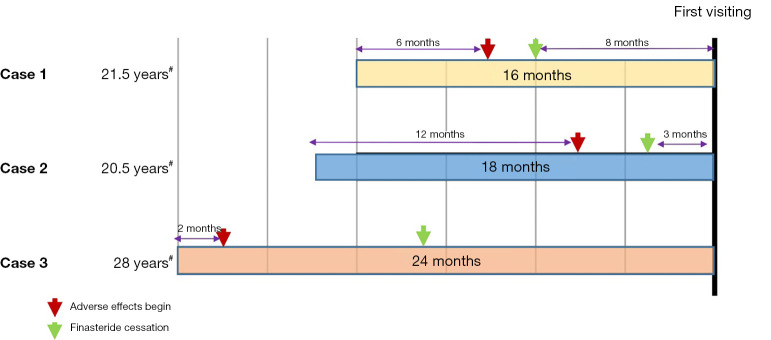

Figure 1 summarizes the history of finasteride use and cessation time. Table 1 presents the clinical manifestations of the patients. All patients began finasteride use between 20 and 28 years of age, and the duration of intermittent finasteride use ranged from 1.5 to 2 years. The specific time of the onset of adverse effects (AEs) ranged from 2 to 12 months. After finasteride cessation, Case 1 and Case 2 experienced symptom improvement for a period of time and then suffered from exacerbated symptoms. All of the patients suffered from erectile dysfunction (ED), anxiety, depression, feelings of isolation, and insomnia. The most frustrating symptoms included insomnia, anxiety, depression, ED, and low libido. Apart from Case 3, who had chronic rhinitis, the other patients had no long-term drug administration history and no baseline medical or psychiatric evaluation prior to finasteride use. None of the patients reported concomitant drug use with finasteride. Physical examination of Case 1 and Case 2 found testicles that were significantly reduced in size.

Figure 1.

History of finasteride use and cessation. #, the ages when patients started to use finasteride.

Table 1. Symptoms of patients.

| Parameter | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual symptoms | |||

| Abnormal ejaculation | × | √ | × |

| ED | √ | √ | √ |

| Orgasmic disorders | √ | × | × |

| Genital numbness | × | × | × |

| Genital shrinkage | √ | √ | × |

| Low libido | √ | × | × |

| Testicular pain | √ | × | × |

| Penile curvature | × | × | × |

| Psychiatric symptoms | |||

| Aggression | × | × | × |

| Anxiety | √ | √ | √ |

| Brain fog | × | × | × |

| Depression | √ | × | × |

| Feelings of isolation/disconnection | √ | √ | √ |

| Memory loss/cognitive changes | √ | × | √ |

| Panic attacks | × | × | × |

| Suicidal ideation | √ | × | × |

| Other symptoms | |||

| Dizziness | √ | × | × |

| Fatigue | √ | √ | × |

| Insomnia | √ | √ | √ |

| Weight loss | × | × | × |

| Gynecomastia/breast enlargement | × | √ | × |

| Breast pain | × | × | × |

| Breast tenderness | × | × | × |

| Breast discharge | × | × | × |

| Self-harm | × | × | × |

| Muscular tremor | √ | √ | × |

×, no; √, yes. ED, erectile dysfunction.

Semen samples were obtained by means of masturbation and analyzed according to the criteria published by the World Health Organization (WHO). Sperm motility and concentration assessments were performed using computer-assisted sperm analysis systems (Suiplus SSA-II, Suiplus Software Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). All sex hormones were measured using an automated chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer (Beckman Coulter UniCel DXI 800, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Case 1 had a low level of total testosterone (TT) (2.78 ng/mL) after the discontinuation of finasteride for 7 months. Detailed laboratory test results are recorded in Table 2 and Table 3. After the presence of persistent AEs in sexuality, emotion, etc., all of the patients took medications to relieve symptoms. Case 1 took Sabal fruit extract soft capsules, Wu Ling capsule, letrozole, HCG + HMG injections, and 11-ketotestosterone. Case 2 took tadalafil, Wu Ling capsule, Bushen Yinao pill, zopiclone, and clomiphene citrate. Case 3 took sildenafil, zopiclone, Wu Ling capsule, and Bushen Yinao pill. ED, testicle shrinkage, and sex hormone imbalance could be improved through drug administration, while lack of libido and psychological and neurological disorders were difficult to treat.

Table 2. Laboratory findings when patients first visited the outpatient department.

| Parameter | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood-RT | |||

| LY% | – | 14.9 | 37.6 |

| MONO% | – | 7.6 | 5.4 |

| NEUT% | – | 76.3 | 47.1 |

| EOS% | – | 0.8 | 8.5 |

| BASO% | – | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| Urine-RT | – | GLU 5.5 mmol/L | Normal |

| Stool-RT | – | Normal | Normal |

| TT, ng/mL | 2.78 | 5.63 | 3.31 |

| E2, pg/mL | – | 24 | 20 |

| PRL, ng/mL | 7.72 | 8.59 | 11.9 |

| LH, IU/L | 5.57 | 5.53 | 3.36 |

| FSH, IU/L | 5.47 | 5.48 | 3.45 |

| Sperm parameters | |||

| pH | – | 7.2 | 7.0 |

| Concentration (×106) | – | 15.12 | 204.07 |

| Motility | |||

| A (%) | – | 4.25 | 10.06 |

| A + B (%) | – | 28.78 | 38.68 |

| A + B + C (%) | – | 29.25 | 47.80 |

| Volume, mL | – | 5.5 | 1.6 |

| T-PSA, ng/mL | – | 1.980 | 0.462 |

| 3-MN, nmol/L | – | 0.15 | – |

| 3-MT, nmol/L | – | 0.012 | – |

| 3-NMN, nmol/L | – | 0.45 | – |

–, missing data. RT, routine test; LY, lymphocyte; MONO, monocyte; NEUT, neutrophil; EOS, eosinophil; BASO, basophilicgranulocyte; TT, total testosterone; E2, estradiol; LH, luteinizing hormone; PRL, prolactin; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; T-PSA, total prostate specific antigen; 3-MN, 3-metanephrine; 3-MT, 3-methoxytyramine; 3-NMN, 3-normetanephrine.

Table 3. Annotation of potential risk genes.

| Gene | Function |

|---|---|

| CA8 | Encodes carbonic anhydrase-related protein |

| VSIG10L2 | Cell adhesion molecule binding |

| HLA-B | Chaperone binding; peptide antigen binding; signaling receptor binding; TAP binding |

| KRT38 | Keratin, type I cuticular Ha8 |

| HLA-DRB1 | CD4 receptor binding; MHC class II protein complex binding; MHC class II receptor activity; peptide antigen binding; polysaccharide binding; structural constituent of cytoskeleton; T-cell receptor binding |

MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Blood samples from PFS patients and the healthy volunteer were stored at −80 ℃ for NGS profiling. Genomic DNA was isolated using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction method. BWA software was used to compare clean reads with the reference genome. After quantity control, we performed basic data and map comparison statistical analyses. Based on the comparison results, GATK software was used to annotate SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) and InDels (insertions and deletions). After filtration based on functional site variations, destructive mutations and gene frequency (Asian population frequency <5%), we obtained 5 potential risk genes, including CA8, VSIG10L2, HLA-B, KRT38 and HLA-DRB1 (Table 3).

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this case report and. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Concerns have emerged about the AEs of finasteride, the indications for which are male-pattern baldness (androgenetic alopecia) and BPH. Reports of suicidality and psychological and physical AEs related to finasteride have led to the term PFS and the creation of organizations such as the Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation. Currently, potential AEs have been identified by health authorities in many countries. PFS is a rare but serious condition, and it mainly occurs in young men, causing great harm to their reproductive health. Abnormal psychological states are often found in PFS patients, while there is still a lack of baseline psychological data. Whether patients with PFS have abnormal emotions before finasteride use still lacks objective evaluation. However, young men who may take finasteride therapy for hair loss should receive consultation services and be informed of possible future harms. Psychological screening is an important method to reduce the occurrence of PFS.

There is a plausible biological basis between the use of finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, and the occurrence of depression and anxiety. Some reports suggest that men with depression have lower levels of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, which is produced by the 5α-reductase enzyme and has antidepressant and anxiolytic effects. However, this association is not commonly observed in broader clinical practice. Many population-based studies have found an increased risk of depression associated with finasteride use in patients with BPH. Most of these studies relied on claims data, and few of them used a validated screening tool for depression. Abnormalities in neurobiological circuitry and neurosteroid alterations include lowered dihydroprogesterone (a ligand for the GABA receptor), progesterone, pregnenolone, and tetrahydroprogesterone and higher testosterone and 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol, which might explain the persistent long-term physical, psychological, and sexual AEs (11-14). At present, the underlying mechanism of PFS is not very clear, and more research is needed to improve the understanding of the disease. Functional analysis of genes indicated that cell junction and connection, immune system, and inflammation pathways may be associated with the occurrence of persistent syndromes. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Andrade et al. (11). Although 5 potential risk genes were identified in three PFS patients, it is difficult to draw an accurate conclusion about whether genetic factors play a causal role in the pathogenesis.

This study has some limitations. The sample number was small, and another control group in which patients who used finasteride without side effects needed to be enrolled. The genetic variants identified could have been preexisting rather than caused by finasteride. A more definitive study would be prospective, with baseline genomic studies repeated periodically and the findings compared with those of patients with and without PFS symptoms. With research progress, genetic screening may be a promising way to avoid the harmful effects of finasteride in people with related genetic risk factors.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFE0207300) and Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z211100002521021).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-22-92/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-22-92/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-22-92/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Gur S, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJ. Effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors on erectile function, sexual desire and ejaculation. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2013;12:81-90. 10.1517/14740338.2013.742885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang JJ, Shi X, Wu T, et al. Sexual, physical, and overall adverse effects in patients treated with 5α-reductase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Androl 2022;24:390-7. 10.4103/aja202171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Low P, Li KD, Hakam N, et al. 5-Alpha reductase inhibitor related litigation: A legal database review. Andrology 2022;10:470-6. 10.1111/andr.13145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pompili M, Magistri C, Maddalena S, et al. Risk of Depression Associated With Finasteride Treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2021;41:304-9. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng T, Duan X, He Z, et al. Association Between 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitor Use and The Risk of Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Urol J 2020;18:144-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen DD, Herzog P, Cone EB, et al. Disproportional signal of sexual dysfunction reports associated with finasteride use in young men with androgenetic alopecia: A pharmacovigilance analysis of VigiBase. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: . 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta AK, Talukder M. Topical finasteride for male and female pattern hair loss: Is it a safe and effective alternative? J Cosmet Dermatol 2022;21:1841-8. 10.1111/jocd.14895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz-Oral D, Onder A, Kaya-Sezginer E, et al. Restorative effects of red onion (Allium cepa L.) juice on erectile function after-treatment with 5α-reductase inhibitor in rats. Int J Impot Res 2022;34:269-76. 10.1038/s41443-021-00421-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diviccaro S, Melcangi RC, Giatti S. Post-finasteride syndrome: An emerging clinical problem. Neurobiol Stress 2019;12:100209. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung HH, Yu J, Kang SJ, et al. Persistent Erectile Dysfunction after Discontinuation of 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitor Therapy in Rats Depending on the Duration of Treatment. World J Mens Health 2019;37:240-8. 10.5534/wjmh.180082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrade C. Why Odds Ratios Can Be Tricky Statistics: The Case of Finasteride, Dutasteride, and Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry 2018;79:18f12641. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Melcangi RC, Santi D, Spezzano R, et al. Neuroactive steroid levels and psychiatric and andrological features in post-finasteride patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017;171:229-35. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Talukder M, et al. Finasteride for hair loss: a review. J Dermatolog Treat 2022;33:1938-46. 10.1080/09546634.2021.1959506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fertig R, Shapiro J, Bergfeld W, et al. Investigation of the Plausibility of 5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitor Syndrome. Skin Appendage Disord 2017;2:120-9. 10.1159/000450617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saengmearnuparp T, Lojanapiwat B, Chattipakorn N, et al. The connection of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors to the development of depression. Biomed Pharmacother 2021;143:112100. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldessarini RJ, Pompili M. Further Studies of Effects of Finasteride on Mood and Suicidal Risk. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2021;41:687-8. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as