Abstract

Smoking is positively associated with multiple cancer types including head and neck cancer (HNC). We sought to confirm the effect of smoking in HNC and subtypes through big data analysis. All data used in this study originated from the Korean National Health Insurance Service database. We analyzed subjects who had undergone health check-ups in 2009 with follow-up until 2018 (n=10,585,852). We collected data on smoking and other variables that could affect the risk of HNC. The overall incidence of HNC was highest in current smokers (HR: 1.822, 95% CI: 1.729-1.920), followed by ex-smokers (HR: 1.242, 95% CI: 1.172-1.317). Laryngeal cancer, hypopharynx cancer, oral cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, and salivary gland cancer showed increasing incidence rates from ex-smokers to current smokers. Smoking duration and amount showed a dose-dependent relationship with the occurrence of HNC. However, the incidence of HNC did not increase significantly when smoking duration was less than 10 years, or when the smoking amount was less than 10 pack-years in ex-smokers. Smoking is associated with the risk of HNC. Smoking cessation before 10 years or 10 pack-years can prevent the development of HNC.

Keywords: Head and neck neoplasms, smoking, epidemiology, Republic of Korea

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is the sixth most common form of cancer worldwide [1]. About 550,000 people are diagnosed with HNC and about 380,000 people die from it every year [2]. Tobacco products cause several types of cancers such as pulmonary, esophageal, gastric, bladder, and pancreatic cancer as well as HNC. Specifically, oral cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx cancer are known to have strong association with smoking [3,4]. Although the incidence of HNC due to human papilloma virus (HPV) is increasing, a 2013 analysis of over 100,000 subjects showed that 66% of HNC diagnoses were tobacco- and alcohol-related [5,6]. Thus, despite the increase in virus-related cancer, tobacco still remains a leading cause of HNC.

The relationship between HNC and smoking and the role of smoking in the development of HNC are well known from many studies. However, given the relative rarity of HNC compared to other cancers, especially when divided by anatomical subsite, previous studies were often not large in scale. Technological innovations combined with automation have created huge amounts of available data, also known as “big data” [7]. Recently, big data has been used in identifying risk factors for diseases to support the clinical decision-making process. Due to the difficulty of selecting optimal treatment modalities and the need for personalized therapy due to different biologic behavior in cancers, big data is a popular tool in oncology research and in HNC specifically [8,9].

The Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) is the public medical insurance system administered by the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs [10]. The National Health Insurance Corporation is a compulsory social insurance system, and about 97% of the total population is enrolled. The remaining 3% of the population are covered by a Medical Aid program. The KNHIS database contains patient demographics and records on diagnosis, interventions, and prescriptions. Therefore, the KNHIS data represent the entire Korean population without selection bias and are used in many epidemiological studies.

The aim of this study was to re-evaluate the effect of smoking in HNC and its subtypes, and to compare the effects of current and previous smoking, smoking amount and period using large-scale data.

Materials and methods

Study population and patient selection

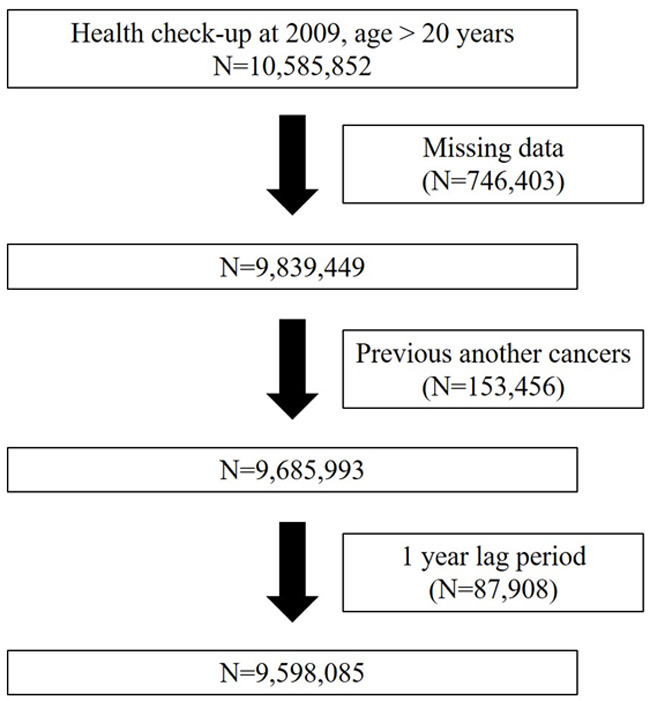

All data used in this study came from the KNHIS database. We selected subjects who were >20 years and who had undergone a health check-up in 2009 (n=10,585,852). We monitored subjects until December 31, 2018. We excluded individuals with missing data (n=746,403) and those with a history of another cancer before health check-up (n=153,456). We also applied a 1-year lag period to minimize detection bias (n=87,908). Finally, 9,598,085 subjects were included in this study from baseline to the date of diagnosis of HNC (Figure 1). Participants were defined as having HNC if they had admission records for HNC in their KNHIS data from 2010 to 2018. Diagnoses were confirmed using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes. HNC was defined according to subsite. We included oral cavity (codes C02, C03, C04, C05, and C06), oropharynx (codes C01, C051, C099, and C103), hypopharynx (codes C12 and C13), larynx (codes C32.0), nasopharynx (code C11), sinonasal cavity (code C10) and salivary gland (codes C07 and C08) cancers. Written informed consent was provided by all participants. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea. Methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of data enrollment.

Classification of smoking status, duration and amount

We categorized subject smoking status into never smokers, ex-smokers, or current smokers. The period of smoking was classified into less than 10 years, from 10 to 20 years, and more than 20 years. The amount of smoking was expressed as pack-years (PYs), which was calculated by multiplying the smoking period by the number of packs smoked per day.

Statistical analysis

Variables were compared using the χ2 test and one-way analysis of variance. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between smoking and the risk of HNC. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, income, BMI, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, and hypertension. In addition to the variables in Model 1, adjustment was made in model 2 for hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, HDL level, LDL level, and triglyceride level. All variables that could affect the incidence of HNC were adjusted. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

General characteristics

The general characteristics of the participants according to smoking status are presented in Table 1. A total of 9,598,085 participants were eligible for this study from 2009 to 2019. Among them, 10,732 participants were newly diagnosed with HNC: 2,972 with laryngeal cancer, 2,225 with oral cavity cancer, 1,814 with oropharyngeal cancer, 929 with hypopharyngeal cancer, 1,101 with nasopharyngeal cancer, 539 with sinus cancer, and 1,273 with salivary gland cancer. There were 2,500,271 (26.0%) current smokers, 1,325,452 (13.8%) ex-smokers, and 5,772,362 (60.2%) never smokers. Among current smokers, 94.1% were male; among ex-smokers, 94.8% were male; and among never smokers, 72.1% were female, showing an overwhelmingly male smoking history. Comparing drinking and smoking status, 17.8% of current smokers and 13.4% of ex-smokers were heavy drinkers, whereas only 2.4% of non-smokers were heavy drinkers, and 68.8% of never smokers were non-drinkers.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants according to smoking status

| Parameter | Non-smoker (N=5772362) | Ex-smoker (N=1325452) | Current smoker (N=2500271) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (group) | <.0001 | |||

| <40 | 1560740 (27.04%) | 339396 (25.61%) | 1130062 (45.2%) | |

| 40-64 | 3314168 (57.41%) | 815479 (61.52%) | 1213421(48.53%) | |

| ≥65 | 897454 (15.55%) | 170577 (12.87%) | 156788 (6.27%) | |

| Age (years) | 48.47±14.52 | 48.74±12.9 | 42.7±12.39 | <.0001 |

| Sex | <.0001 | |||

| Male | 1612028 (27.93%) | 1256220 (94.78%) | 2352553 (94.09%) | |

| Female | 4160334 (72.07%) | 69232 (5.22%) | 147718 (5.91%) | |

| Alcohol | <.0001 | |||

| Non | 3971909 (68.81%) | 387874 (29.26%) | 579528 (23.18%) | |

| Mild | 1659414 (28.75%) | 759507 (57.3%) | 1473652 (58.94%) | |

| Heavy | 141039 (2.44%) | 178071 (13.43%) | 447091 (17.88%) | |

| Regular exercise | 969922 (16.8%) | 332694 (25.1%) | 405796 (16.23%) | <.0001 |

| Low income | 1284888 (22.26%) | 181487 (13.69%) | 411541 (16.46%) | <.0001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <.0001 | |||

| <18.5 | 254354 (4.41%) | 22405 (1.69%) | 80711 (3.23%) | |

| <23 | 2427070 (42.05%) | 397607 (30%) | 925389 (37.01%) | |

| <25 | 1359999 (23.56%) | 377572 (28.49%) | 621391 (24.85%) | |

| <30 | 1533879 (26.575) | 483365 (36.47%) | 771930 (30.87%) | |

| ≥30 | 197060 (3.41%) | 44503 (3.36%) | 100850 (4.03%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.47±3.42 | 24.34±2.92 | 23.9±3.75 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 466341 (8.08%) | 147086 (11.1%) | 217212 (8.69%) | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1500895 (26%) | 419576 (31.66%) | 546373 (21.85%) | <.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1085385 (18.8%) | 264361 (19.94%) | 386620 (15.46%) | <.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 436440 (7.56%) | 98814 (7.46%) | 123296 (4.93%) | <.0001 |

| Height (cm) | 159.98±8.55 | 169.09±6.66 | 169.96±7.03 | <.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.21±10.55 | 69.73±10.2 | 69.23±11.43 | <.0001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 78.26±9.55 | 84.05±8.28 | 82.66±8.71 | <.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 121.33±15.53 | 125.15±14.3 | 123.52±14.09 | <.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.35±10.13 | 78.27±9.81 | 77.5±9.8 | <.0001 |

| Glucose level (mM) | 96.14±22.27 | 100.32±25.1 | 98.13±26.39 | <.0001 |

| HDL level (mM) | 58.37±34.65 | 54.03±29.91 | 53.46±29.21 | <.0001 |

| Cholesterol level (mM) | 195.27±41.66 | 196.48±40.93 | 194.91±41.29 | <.0001 |

| LDL level (mM) | 122.08±206.17 | 119.97±191.54 | 116.71±196.97 | <.0001 |

| Triglyceride level (mM) | 101.48 (101.44-101.53) | 126.15 (126.02-126.27) | 135.12 (135.02-135.22) | <.0001 |

Relationship between smoking status and HNC

The incidence of HNC according to smoking status is shown in Table 2. The overall incidence of HNC was highest in current smokers (HR: 1.822, 95% CI: 1.729-1.920), followed by ex-smokers (HR: 1.242, 95% CI: 1.172-1.317). Analysis by subtype showed similar results, with increasing incidence rates from ex-smokers to current smokers. This trend was very strong in laryngeal cancer and hypopharynx cancer, and was clearly shown in oropharynx cancer and oral cavity cancer. However, this trend was not statistically significant in sinonasal cancer or nasopharynx cancer.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios of head and neck cancer and its subtypes according smoking status

| subsites | Smoking status | N | Event | Incidence Rate | Model 1 | P value | Model 2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 4273 | 0.08969 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 2239 | 0.2061 | 1.245 (1.174, 1.319) | 1.242 (1.172, 1.317) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 4220 | 0.20626 | 1.832 (1.739, 1.930) | 1.822 (1.729, 1.92) | |||

| Larynx | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 682 | 0.01431 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 719 | 0.06616 | 1.669 (1.494, 1.866) | 1.658 (1.483, 1.853) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 1571 | 0.07676 | 3.294 (2.980, 3.641) | 3.256 (2.945, 3.599) | |||

| Sinonasal cavity | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 280 | 0.00588 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0755 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0766 | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 94 | 0.00865 | 0.981 (0.748, 1.286) | 0.982 (0.749, 1.288) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 165 | 0.00806 | 1.263 (0.993, 1.606) | 1.264 (0.993, 1.610) | |||

| Hypopharynx | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 271 | 0.00569 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 193 | 0.01776 | 1.150 (0.946, 1.398) | 1.15 (0.946, 1.398) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 465 | 0.02272 | 2.252 (1.903, 2.664) | 2.229 (1.883, 2.638) | |||

| Oropharynx | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 685 | 0.01438 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 418 | 0.03846 | 1.182 (1.033, 1.353) | 1.178 (1.030, 1.348) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 711 | 0.03473 | 1.564 (1.383, 1.769) | 1.555 (1.374, 1.759) | |||

| Oral cavity | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 1172 | 0.0246 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 383 | 0.03524 | 1.085 (0.947, 1.243) | 1.081 (0.944, 1.239) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 670 | 0.03273 | 1.415 (1.254, 1.597) | 1.399 (1.239, 1.580) | |||

| Nasopharynx | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 492 | 0.01033 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0276* | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0269* | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 237 | 0.0218 | 1.175 (0.984, 1.404) | 1.177 (0.985, 1.405) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 372 | 0.01817 | 1.245 (1.058, 1.466) | 1.247 (1.059, 1.469) | |||

| Salivary gland | ||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 733 | 0.01538 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0537 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0485 | |

| Ex-smoker | 1325452 | 220 | 0.02024 | 1.213 (1.011, 1.456) | 1.214 (1.011, 1.457) | |||

| Current smoker | 2500271 | 320 | 0.01563 | 1.201 (1.015, 1.421) | 1.208 (1.020, 1.431) | |||

Incidence rate per 1,000 person-years. Model 1: Age, sex, income, BMI, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, and hypertension. Model 2: Age, sex, income, BMI, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, HDL level, LDL level, and triglyceride level.

Significant at p<0.05.

Relationship between smoking duration and HNC

The incidence of HNC according to smoking duration is shown in Table 3. The overall incidence of HNC increased in proportion to smoking duration in both ex-smokers and current smokers. However, in both groups, the HR did not increase when the duration was less than 10 years (HR: 0.873, 95% CI: 0.758-1.006 for ex-smokers; HR: 0.932, 95% CI: 0.785-1.107 for current smokers).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios of head and neck cancer and its subtypes according to smoking duration

| subsites | Smoking status | Year | N | Event | Incidence Rate | Model 1 | P value | Model 2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 4273 | 0.08969 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 210 | 0.08103 | 0.872 (0.757, 1.004) | 0.873 (0.758, 1.006) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 540 | 0.1387 | 1.126 (1.024, 1.237) | 1.125 (1.024, 1.237) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 1489 | 0.34005 | 1.388 (1.300, 1.483) | 1.384 (1.296, 1.479) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 142 | 0.0475 | 0.931 (0.785, 1.106) | 0.932 (0.785, 1.107) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 503 | 0.06488 | 1.071 (0.968, 1.185) | 1.069 (0.966, 1.182) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 3575 | 0.36788 | 2.061 (1.954, 2.175) | 2.050 (1.943, 2.163) | ||||

| Larynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 682 | 0.01431 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 42 | 0.0162 | 0.878 (0.641, 1.203) | 0.881 (0.643, 1.206) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 120 | 0.03081 | 1.193 (0.978, 1.455) | 1.191 (0.976, 1.453) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 557 | 0.12713 | 1.951 (1.733, 2.196) | 1.933 (1.717, 2.176) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 32 | 0.0107 | 1.449 (1.101, 2.078) | 1.451 (1.012, 2.082) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 105 | 0.01354 | 1.561 (1.253, 1.945) | 1.556 (1.249, 1.939) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 1434 | 0.14747 | 3.532 (3.194, 3.906) | 3.492 (3.157, 3.863) | ||||

| Sinonasal cavity | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 280 | 0.005876 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0593 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0641 | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 13 | 0.005015 | 0.949 (0.535, 1.682) | 0.954 (0.538, 1.692) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 23 | 0.005905 | 0.861 (0.549, 1.349) | 0.865 (0.552, 1.356) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 58 | 0.013232 | 1.054 (0.768, 1.447) | 1.052 (0.766, 1.445) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 8 | 0.002676 | 0.830 (0.402, 1.711) | 0.831 (0.403, 1.714) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 26 | 0.003353 | 0.879 (0.565, 1.368) | 0.885 (0.568, 1.378) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 131 | 0.013466 | 1.409 (1.094, 1.814) | 1.409 (1.093, 1.816) | ||||

| Hypopharynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 271 | 0.005687 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 8 | 0.003086 | 0.441 (0.217, 0.894) | 0.444 (0.219, 0.901) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 31 | 0.007959 | 0.826 (0.565, 1.206) | 0.831 (0.568, 1.213) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 154 | 0.035136 | 1.356 (1.102, 1.670) | 1.354 (1.099, 1.667) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 6 | 0.002007 | 0.680 (0.3, 1.542) | 0.681 (0.3, 1.542) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 13 | 0.001677 | 0.5 (0.282, 0.887) | 0.499 (0.281, 0.886) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 446 | 0.045849 | 2.471 (2.089, 2.924) | 2.447 (2.067, 2.897) | ||||

| Oropharynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 685 | 0.014375 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 38 | 0.01466 | 0.783 (0.562, 1.092) | 0.784 (0.562, 1.093) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 121 | 0.031068 | 1.248 (1.019, 1.530) | 1.247 (1.017, 1.528) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 259 | 0.059098 | 1.247 (1.067, 1.456) | 1.241 (1.062, 1.449) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 27 | 0.009031 | 0.861 (0.580, 1.278) | 0.86 (0.58, 1.277) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 93 | 0.011994 | 0.949 (0.749, 1.201) | 0.946 (0.747, 1.198) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 591 | 0.06076 | 1.757 (1.548, 1.993) | 1.748 (1.539, 1.984) | ||||

| Oral cavity | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 1172 | 0.024596 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 47 | 0.018133 | 0.916 (0.678, 1.236) | 0.918 (0.680, 1.239) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 110 | 0.028244 | 1.121 (0.909, 1.382) | 1.118 (0.907, 1.379) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 226 | 0.051565 | 1.124 (0.956, 1.320) | 1.117 (0.951, 1.313) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 28 | 0.009366 | 0.785 (0.535, 1.153) | 0.784 (0.534, 1.151) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 126 | 0.016251 | 1.181 (0.961, 1.451) | 1.171 (0.953, 1.439) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 516 | 0.053048 | 1.548 (1.362, 1.759) | 1.529 (1.345, 1.739) | ||||

| Nasopharynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 492 | 0.010325 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0015* | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0015* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 31 | 0.01196 | 0.913 (0.629, 1.327) | 0.914 (0.629, 1.329) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 71 | 0.018229 | 1.133 (0.87, 1.477) | 1.134 (0.87, 1.478) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 135 | 0.030801 | 1.3 (1.052, 1.607) | 1.302 (1.053, 1.610) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 24 | 0.008028 | 0.853 (0.557, 1.305) | 0.855 (0.559, 1.309) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 83 | 0.010705 | 0.966 (0.745, 1.253) | 0.968 (0.746, 1.257) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 265 | 0.027242 | 1.401 (1.177, 1.669) | 1.404 (1.178, 1.673) | ||||

| Salivary gland | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 733 | 0.015383 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0013* | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0011* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 313103 | 31 | 0.01196 | 1.019 (0.702, 1.479) | 1.017 (0.701, 1.477) | |||

| <20 | 471205 | 70 | 0.017973 | 1.284 (0.983, 1.678) | 1.285 (0.983, 1.679) | ||||

| ≥20 | 541144 | 119 | 0.02715 | 1.260 (1.008, 1.575) | 1.262 (1.009, 1.577) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 361298 | 20 | 0.00669 | 0.790 (0.499, 1.249) | 0.791 (0.5, 1.251) | |||

| <20 | 937530 | 63 | 0.008125 | 0.868 (0.653, 1.155) | 0.873 (0.656, 1.162) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1201443 | 237 | 0.024363 | 1.396 (1.164, 1.675) | 1.407 (1.172, 1.688) | ||||

Incidence rate per 1,000 person-years. Model 1: Age, sex, income, BMI, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, and hypertension. Model 2: Age, sex, income, BMI, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, HDL level, LDL level, and triglyceride level.

Significant at p<0.05.

All subtypes except sinonasal cancer showed a similar trend to HNC overall. HRs increased in proportion to duration, but did not increase when smoking duration was less than 10 years in both ex- and current smokers. However, in the case of larynx cancer, the HR increased in the case of current smokers even if the duration was less than 10 years (HR: 1.451, 95% CI: 1.012-2.082). Larynx cancer (HR: 3.492, 95% CI: 3.157-3.863) and hypopharynx (HR: 2.447, 95% CI: 2.067-2.897) cancer showed very high HRs in current smokers with a smoking duration over 20 years.

Relationship between smoking amount and HNC

The incidence of HNC according to smoking amount is shown in Table 4. Like smoking duration, the overall incidence of HNC increased in proportion to smoking amount in both ex-smokers and current smokers; for the same smoking amount, current smokers had a higher HR than ex-smokers. As seen for smoking duration, when the smoking amount was 10 PYs or less in ex-smokers, the HR was not increased (HR: 1.068, 95% CI: 0.933-1.223).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios of head and neck cancer and its subtypes according to smoking amount

| subsites | Smoking status | Pack-year | N | Event | Incidence Rate | Model 1 | P value | Model 2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 4273 | 0.08969 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 229 | 0.1451 | 1.066 (0.931, 1.221) | 1.068 (0.933, 1.223) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 704 | 0.16201 | 1.098 (1.008, 1.195) | 1.098 (1.008, 1.195) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 1306 | 0.26438 | 1.405 (1.312, 1.504) | 1.4 (1.307, 1.499) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 360 | 0.16111 | 1.410 (1.262, 1.574) | 1.408 (1.261, 1.573) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 1392 | 0.15911 | 1.607 (1.502, 1.720) | 1.603 (1.497, 1.715) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 2468 | 0.26043 | 2.129 (2.007, 2.259) | 2.115 (1.993, 2.244) | ||||

| Larynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 682 | 0.01431 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 54 | 0.0342 | 1.066 (0.806, 1.409) | 1.066 (0.806, 1.41) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 201 | 0.04624 | 1.352 (1.150, 1.590) | 1.347 (1.145, 1.584) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 464 | 0.09388 | 2.032 (1.795, 2.300) | 2.013 (1.778, 2.279) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 125 | 0.05593 | 2.138 (1.761, 2.596) | 2.129 (1.753, 2.585) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 474 | 0.05416 | 2.712 (2.393, 3.075) | 2.693 (2.375, 3.053) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 972 | 0.10252 | 4.121 (3.694, 4.597) | 4.064 (3.642, 4.535) | ||||

| Sinonasal cavity | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 280 | 0.005876 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.1104 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.1104 | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 8 | 0.005066 | 0.698 (0.342, 1.425) | 0.701 (0.344, 1.432) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 27 | 0.00621 | 0.788 (0.518, 1.198) | 0.791 (0.52, 1.203) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 59 | 0.011934 | 1.194 (0.872, 1.636) | 1.192 (0.87, 1.634) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 15 | 0.00671 | 1.065 (0.625, 1.814) | 1.067 (0.626, 1.818) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 59 | 0.006741 | 1.199 (0.874, 1.646) | 1.203 (0.876, 1.652) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 91 | 0.009595 | 1.371 (1.034, 1.819) | 1.372 (1.033, 1.822) | ||||

| Hypopharynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 271 | 0.005687 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 14 | 0.008866 | 0.699 (0.407, 1.2) | 0.704 (0.410, 1.208) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 46 | 0.010581 | 0.799 (0.581, 1.1) | 0.803 (0.583, 1.105) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 133 | 0.026904 | 1.493 (1.201, 1.855) | 1.488 (1.197, 1.85) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 46 | 0.020578 | 1.776 (1.291, 2.443) | 1.768 (1.285, 2.432) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 127 | 0.01451 | 1.693 (1.353, 2.118) | 1.682 (1.344, 2.106) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 292 | 0.030791 | 2.855 (2.370, 3.439) | 2.82 (2.34, 3.4) | ||||

| Oropharynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 685 | 0.014375 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 45 | 0.028501 | 1.076 (0.792, 1.462) | 1.077 (0.792, 1.463) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 142 | 0.032665 | 1.111 (0.919, 1.344) | 1.109 (0.917, 1.342) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 231 | 0.046731 | 1.263 (1.076, 1.483) | 1.256 (1.07, 1.475) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 60 | 0.026842 | 1.239 (0.946, 1.622) | 1.237 (0.945, 1.62) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 263 | 0.030051 | 1.516 (1.297, 1.773) | 1.511 (1.292, 1.768) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 388 | 0.040916 | 1.681 (1.459, 1.938) | 1.669 (1.448, 1.924) | ||||

| Oral cavity | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 1172 | 0.024596 | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | 1 (Ref.) | <.0001* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 49 | 0.031035 | 1.121 (0.836, 1.503) | 1.123 (0.838, 1.506) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 143 | 0.032895 | 1.117 (0.925, 1.349) | 1.116 (0.924, 1.348) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 191 | 0.038638 | 1.067 (0.9, 1.265) | 1.06 (0.894, 1.257) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 61 | 0.027289 | 1.143 (0.878, 1.489) | 1.138 (0.874, 1.482) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 234 | 0.026737 | 1.288 (1.099, 1.511) | 1.278 (1.089, 1.499) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 375 | 0.039545 | 1.598 (1.387, 1.84) | 1.575 (1.367, 1.85) | ||||

| Nasopharynx | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 492 | 0.010325 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0449* | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0449* | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 30 | 0.019 | 1.216 (0.834, 1.773) | 1.221 (0.837, 1.779) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 81 | 0.018632 | 1.065 (0.829, 1.369) | 1.069 (0.832, 1.374) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 126 | 0.025488 | 1.255 (1.012, 1.556) | 1.254 (1.011, 1.556) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 33 | 0.014763 | 1.094 (0.763, 1.569) | 1.098 (0.765, 1.575) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 134 | 0.01531 | 1.124 (0.908, 1.390) | 1.128 (0.912, 1.396) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 205 | 0.021617 | 1.380 (1.142, 1.667) | 1.38 (1.141, 1.668) | ||||

| Salivary gland | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 5772362 | 733 | 0.015383 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0701 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0701 | ||

| Ex-smoker | <10 | 192061 | 31 | 0.019634 | 1.336 (0.923, 1.935) | 1.337 (0.923, 1.936) | |||

| <20 | 527968 | 72 | 0.016562 | 1.077 (0.827, 1.402) | 1.079 (0.829, 1.405) | ||||

| ≥20 | 605423 | 117 | 0.023668 | 1.3 (1.04, 1.625) | 1.3 (1.04, 1.626) | ||||

| Current smoker | <10 | 274587 | 27 | 0.012078 | 0.916 (0.619, 1.357) | 0.921 (0.622, 1.364) | |||

| <20 | 1065782 | 120 | 0.013711 | 1.152 (0.924, 1.437) | 1.16 (0.93, 1.447) | ||||

| ≥20 | 1159902 | 173 | 0.018242 | 1.323 (1.082, 1.617) | 1.331 (1.088, 1.629) | ||||

Incidence rate per 1,000 person-years. Model 1: Age, sex, income, BMI, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, and hypertension. Model 2: Age, sex, income, BMI, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, HDL level, LDL level, and triglyceride level.

Significant at p<0.05.

HR significantly increased according to smoking amount in all subtypes except sinonasal and salivary cancers. In particular, larynx (HR: 4.64, 95% CI: 3.642-4.535) and hypopharynx (HR: 2.820, 95% CI: 2.340-3.400) cancer showed very high HRs in current smokers with over 20 PYs.

Discussion

Cigarette smoke is a potent carcinogen that is strongly associated with many cancers. HNC is one of many cancers that are closely related to tobacco use. According to Hashibe et al. who identified independent associations of tobacco and alcohol with HSC, cigarette smoking was associated with an increased risk of HNC (HR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.52-2.98) [11]. The recent understanding of the harmful effects of smoking has created a pathway towards education and regulatory efforts aimed at reducing tobacco use [12,13]. As a result of this effort, the smoking ratio has been gradually decreasing. In addition, recently, as the incidence of cancer caused by HPV has gradually increased, the influence of traditional risk factors such as smoking and alcohol on cancer development has gradually decreased. However, while HPV-induced HNC is rising in incidence, a 2013 analysis of over 100,000 subjects showed that 66% of HNC diagnoses were tobacco- and alcohol-related [5]. Thus, tobacco remains a prominent cause of HNC.

Although many studies have already explored HNC and smoking, we looked into the association in more detail using big data, and examined the association by subtype and by smoking status, duration and amount. The strengths of our study are that the results were from cohort data including more than 9.5 million participants over 10 years. Therefore, we investigated the association between smoking and HNC subtype with sufficient power.

As mentioned earlier, the HR of developing HNC in current smokers compared to never smokers was approximately 2.13 [11]. Our data showed similar results. The HR of current smokers was 1.822 (95% CI: 1.729-1.920, P<0.0001). Smoking cessation, however, lowers the likelihood of occurrence of HNC to some extent. Because the period after cessation was not analyzed separately in this study, it is not known how long after cessation can be free from HNC. According to previous studies, while cessation does certainly lower risk, it is unclear whether risk returns to that of a never smoker [14,15]. Some data suggest that the risk returns to that of a never smoker after about 20 years of cessation [16]. When the correlation between smoking and cancer incidence was divided by subtype, larynx cancer, hypopharynx cancer, oropharynx cancer, oral cavity cancer, and nasopharynx cancer showed a significant association with smoking status, but sinonasal cancer and salivary gland cancer did not. In particular, larynx cancer and hypopharynx cancer had a very high HR in current smokers compared to other subtypes. The mucosal lining of the upper aerodigestive tract receives considerable exposure to tobacco smoke as it is transmitted from the lips to the lungs. Because of this direct contact with the smoke, a strong association with smoking was expected. Sinonasal cavities and salivary glands not in direct contact with smoke did not show a significant association with smoking status. Nasopharynx cancer and oropharynx cancer showed a relatively low association compared to the larynx and hypopharynx. This is probably because, unlike other subtypes, virus-related cancers account for a higher proportion of disease (Epstein-Barr virus for nasopharynx cancer and HPV for oropharynx cancer).

Smoking duration and amount showed a dose-dependent relationship with the occurrence of HNC [17-20]. However, the incidence of HNC did not increase significantly when the smoking duration was less than 10 years, or when the smoking amount was less than 10 PYs in ex-smokers. In the case of current smokers, the incidence of HNC was slightly increased when the smoking amount was 10 PYs. This is an important implication, and can be the basis for strongly recommending quitting smoking to smokers who have not smoked for a long time, as much as abstaining from smoking altogether to prevent HNC. Similarly, cancer incidence rate according to subtype did not increase significantly when the smoking duration was less than 10 years, and when the smoking amount was less than 10 PYs in ex-smokers. Unlike other subtypes, in the case of larynx cancer, even if smoking duration was less than 10 years, the cancer incidence rate was significantly higher for current smokers; thus, smoking cessation is recommended for the prevention of larynx cancer.

This study has several limitations. First, most of the participants were Korean, so the results may not be generalizable to other Asians. Another limitation is that we used the PY method when expressing smoking amount. The use of PYs to summarize smoking history has been criticized as inconsistent with epidemiologic and molecular models of cancer [21]. PYs or drink-years (the multiplication of a frequency times a duration measure) cannot distinguish between low frequency use for a long time period and high-frequency use for a short period. Second, the effects of HPV on oropharyngeal cancer were not included. Because the diagnosis in the Korea NHIS is based on the International Classification of Diseases, we cannot distinguish between oropharynx cancer related to HPV status. Another limitation is that the effects of alcohol could not be excluded. Smoking and alcohol have a synergistic effect in cancer development, so in order to see the pure effect of smoking, the effects of alcohol should be excluded, which was not done in this study.

In conclusion, despite these limitations, this study is meaningful because it analyzed the effects of smoking on the occurrence of HNC in depth using big data, and separately for each subtype. In addition, this study provided a basis for recommending smoking cessation in patients who have already started smoking by revealing that smoking cessation within 10 years and before reaching 10 PYs could help mitigate the risk of HNC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (The Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (Project Number: 202011D15).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- HNC

Head and neck cancer

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- HR

Hazard ratio

- KNHIS

Korean National Health Insurance Service

- PYs

Pack-years

References

- 1.Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2008;371:1695–1709. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60728-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, Dicker DJ, Chimed-Orchir O, Dandona R, Dandona L, Fleming T, Forouzanfar MH, Hancock J, Hay RJ, Hunter-Merrill R, Huynh C, Hosgood HD, Johnson CO, Jonas JB, Khubchandani J, Kumar GA, Kutz M, Lan Q, Larson HJ, Liang X, Lim SS, Lopez AD, MacIntyre MF, Marczak L, Marquez N, Mokdad AH, Pinho C, Pourmalek F, Salomon JA, Sanabria JR, Sandar L, Sartorius B, Schwartz SM, Shackelford KA, Shibuya K, Stanaway J, Steiner C, Sun J, Takahashi K, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wagner JA, Wang H, Westerman R, Zeeb H, Zoeckler L, Abd-Allah F, Ahmed MB, Alabed S, Alam NK, Aldhahri SF, Alem G, Alemayohu MA, Ali R, Al-Raddadi R, Amare A, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Asayesh H, Atnafu N, Awasthi A, Saleem HB, Barac A, Bedi N, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bernabe E, Betsu B, Binagwaho A, Boneya D, Campos-Nonato I, Castaneda-Orjuela C, Catala-Lopez F, Chiang P, Chibueze C, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Damtew S, das Neves J, Dey S, Dharmaratne S, Dhillon P, Ding E, Driscoll T, Ekwueme D, Endries AY, Farvid M, Farzadfar F, Fernandes J, Fischer F, G/Hiwot TT, Gebru A, Gopalani S, Hailu A, Horino M, Horita N, Husseini A, Huybrechts I, Inoue M, Islami F, Jakovljevic M, James S, Javanbakht M, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Kedir MS, Khader YS, Khang YH, Kim D, Leigh J, Linn S, Lunevicius R, El Razek HMA, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Marcenes W, Markos D, Melaku YA, Meles KG, Mendoza W, Mengiste DT, Meretoja TJ, Miller TR, Mohammad KA, Mohammadi A, Mohammed S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nand D, Le Nguyen Q, Nolte S, Ogbo FA, Oladimeji KE, Oren E, Pa M, Park EK, Pereira DM, Plass D, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Rafay A, Rahman M, Rana SM, Soreide K, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou SG, Shaikh MA, She J, Shiue I, Shore HR, Shrime MG, So S, Soneji S, Stathopoulou V, Stroumpoulis K, Sufiyan MB, Sykes BL, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Tadese F, Tedla BA, Tessema GA, Thakur JS, Tran BX, Ukwaja KN, Uzochukwu BSC, Vlassov VV, Weiderpass E, Wubshet Terefe M, Yebyo HG, Yimam HH, Yonemoto N, Younis MZ, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zaki MES, Zenebe ZM, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phua ZJ, MacInnis RJ, Jayasekara H. Cigarette smoking and risk of second primary cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022;78:102160. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2022.102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyss A, Hashibe M, Chuang SC, Lee YC, Zhang ZF, Yu GP, Winn DM, Wei Q, Talamini R, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Sturgis EM, Smith E, Shangina O, Schwartz SM, Schantz S, Rudnai P, Purdue MP, Eluf-Neto J, Muscat J, Morgenstern H, Michaluart P Jr, Menezes A, Matos E, Mates IN, Lissowska J, Levi F, Lazarus P, La Vecchia C, Koifman S, Herrero R, Hayes RB, Franceschi S, Wunsch-Filho V, Fernandez L, Fabianova E, Daudt AW, Dal Maso L, Curado MP, Chen C, Castellsague X, de Carvalho MB, Cadoni G, Boccia S, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Olshan AF. Cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking and the risk of head and neck cancers: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:679–690. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashibe M, Hunt J, Wei M, Buys S, Gren L, Lee YC. Tobacco, alcohol, body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of head and neck cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian (PLCO) cohort. Head Neck. 2013;35:914–922. doi: 10.1002/hed.23052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarter K, Baker AL, Wolfenden L, Wratten C, Bauer J, Beck AK, Forbes E, Carter G, Leigh L, Oldmeadow C, Britton B. Smoking and other health factors in patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022;79:102202. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2022.102202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Kang L, Zhao XM. A survey on evolutionary algorithm based hybrid intelligence in bioinformatics. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:362738. doi: 10.1155/2014/362738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavalieri S, De Cecco L, Brakenhoff RH, Serafini MS, Canevari S, Rossi S, Lanfranco D, Hoebers FJP, Wesseling FWR, Keek S, Scheckenbach K, Mattavelli D, Hoffmann T, Lopez Perez L, Fico G, Bologna M, Nauta I, Leemans CR, Trama A, Klausch T, Berkhof JH, Tountopoulos V, Shefi R, Mainardi L, Mercalli F, Poli T, Licitra L BD2Decide Consortium. Development of a multiomics database for personalized prognostic forecasting in head and neck cancer: The Big Data to Decide EU Project. Head Neck. 2021;43:601–612. doi: 10.1002/hed.26515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resteghini C, Trama A, Borgonovi E, Hosni H, Corrao G, Orlandi E, Calareso G, De Cecco L, Piazza C, Mainardi L, Licitra L. Big data in head and neck cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:62. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0585-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DS. Introduction: health of the health care system in Korea. Soc Work Public Health. 2010;25:127–141. doi: 10.1080/19371910903070333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, Castellsague X, Chen C, Curado MP, Dal Maso L, Daudt AW, Fabianova E, Fernandez L, Wunsch-Filho V, Franceschi S, Hayes RB, Herrero R, Koifman S, La Vecchia C, Lazarus P, Levi F, Mates D, Matos E, Menezes A, Muscat J, Eluf-Neto J, Olshan AF, Rudnai P, Schwartz SM, Smith E, Sturgis EM, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Talamini R, Wei Q, Winn DM, Zaridze D, Zatonski W, Zhang ZF, Berthiller J, Boffetta P. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jethwa AR, Khariwala SS. Tobacco-related carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017;36:411–423. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9689-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pacek LR, Villanti AC, McClernon FJ. Not quite the rule, but no longer the exception: multiple tobacco product use and implications for treatment, research, and regulation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22:2114–2117. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day GL, Blot WJ, Shore RE, McLaughlin JK, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Liff JM, Preston-Martin S, Sarkar S, Schoenberg JB, et al. Second cancers following oral and pharyngeal cancers: role of tobacco and alcohol. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:131–137. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gislon LC, Curado MP, Lopez RVM, de Oliveira JC, Vasconcelos de Podesta JR, Ventorin von Zeidler S, Brennan P, Kowalski LP. Risk factors associated with head and neck cancer in former smokers: a Brazilian multicentric study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022;78:102143. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2022.102143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winn DM, Lee YC, Hashibe M, Boffetta P INHANCE consortium. The INHANCE consortium: toward a better understanding of the causes and mechanisms of head and neck cancer. Oral Dis. 2015;21:685–693. doi: 10.1111/odi.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyal N, Hennessy M, Lehman E, Lin W, Agudo A, Ahrens W, Boccia S, Brennan P, Brenner H, Cadoni G, Canova C, Chen C, Conway D, Curado MP, Dal Maso L, Daudt AW, Edefonti V, Fabianova E, Fernandez L, Franceschi S, Garavello W, Gillison M, Hayes RB, Healy C, Herrero R, Holcatova I, Kanda JL, Kelsey K, Hansen BT, Koifman R, Lagiou P, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Li G, Lissowska J, Mendoza Lopez R, Luce D, Macfarlane G, Mates D, Matsuo K, McClean M, Menezes A, Menvielle G, Morgenstern H, Moysich K, Negri E, Olshan AF, Pandics T, Polesel J, Purdue M, Radoi L, Ramroth H, Richiardi L, Schantz S, Schwartz SM, Serraino D, Shangina O, Smith E, Sturgis EM, Swiatkowska B, Thomson P, Vaughan TL, Vilensky M, Winn DM, Wunsch-Filho V, Yu GP, Zevallos JP, Zhang ZF, Zheng T, Znaor A, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, Lee YA, Muscat JE. Risk factors for head and neck cancer in more and less developed countries: analysis from the INHANCE consortium. Oral Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1111/odi.14196. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menvielle G, Luce D, Goldberg P, Bugel I, Leclerc A. Smoking, alcohol drinking and cancer risk for various sites of the larynx and hypopharynx. A case-control study in France. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:165–172. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000130017.93310.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelucchi C, Gallus S, Garavello W, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C. Alcohol and tobacco use, and cancer risk for upper aerodigestive tract and liver. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:340–344. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo Y, Shin DW, Han K, Kim D, Kim TH, Chun S, Jeong SM, Song YM. Smoking, alcohol consumption, and the risk of thyroid cancer: a population-based Korean cohort study of 10 million people. Thyroid. 2022;32:440–448. doi: 10.1089/thy.2021.0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peto J. That the effects of smoking should be measured in pack-years: misconceptions 4. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:406–407. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]