Abstract

Associations of energy balance components, including physical activity and obesity, with colorectal cancer risk and mortality are well established. However, the gut microbiome has not been investigated as underlying mechanism. We investigated associations of physical activity, BMI, and combinations of physical activity/BMI with gut microbiome diversity and differential abundances among colorectal cancer patients. N=179 patients with colorectal cancer (stages I-IV) were included in the study. Pre-surgery stool samples were used to perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Illumina). Physical activity (MET hrs/wk) during the year before diagnosis was assessed by questionnaire and participants were classified as being active vs. inactive based on guidelines. BMI at baseline was abstracted from medical records. Patients were classified into four combinations of physical activity levels/BMI. Lower gut microbial diversity was observed among ‘inactive’ vs. ‘active’ patients (Shannon: P=0.01, Simpson: P=0.03), ‘obese’ vs. ‘normal weight’ patients (Shannon, Simpson, and Observed species: P=0.02, respectively), and ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ vs. ‘normal weight/active’ patients (Shannon: P=0.02, Observed species: P=0.04). Results differed by sex and tumor site. Two phyla and 12 genera (Actinobacteria and Fusobacteria, Adlercreutzia, Anaerococcus, Clostridium, Eubacterium, Mogibacteriaceae, Olsenella, Peptinophilus, Pyramidobacter, RFN20, Ruminococcus, Succinivibrio, Succiniclasticum) were differentially abundant across physical activity and BMI groups. This is the first evidence for associations of physical activity with gut microbiome diversity and abundances, directly among colorectal cancer patients. Our results indicate that physical activity may offset gut microbiome dysbiosis due to obesity. Alterations in gut microbiota may contribute mechanistically to the energy balance-colorectal cancer link and impact clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, physical activity, obesity, microbiome, energy balance

Introduction

Components of energy balance, such as physical activity and obesity, have been associated both with colorectal cancer risk and outcomes. The underlying biological mechanisms and opportunities for intervention remain under investigation. A possible factor, the gut microbiome, is emerging as a critical area of interest.

Physical activity and BMI have emerged as predictive components of cancer prevention and control [1-4]. Increased physical activity levels throughout the cancer care continuum may reduce the mortality risk by up to 38% among colorectal cancer survivors [1,2]. In contrast, such a linear relationship has not been confirmed with BMI and colorectal cancer survival showing superior survival outcomes for overweight and class I obese patients compared to other BMI categories [3,5]. An emerging question is whether overweight and obese individuals may offset some of their adverse metabolic profile by greater exercise. “Metabolically healthy obese” patients do not present the phenotype characterized by obesity including chronic systemic inflammation and insulin resistance [6,7]. A complete picture of metabolic changes defining metabolically healthy obesity has yet to be established [6,7].

Although multiple biological explanations including inflammation, angiogenesis, oxidative stress, and immune function have been identified as possible mechanistic underpinnings of the energy balance-cancer link [4,8], a possible pathway through the gut microbiome is just at the verge of investigation. Alterations in gut microbial composition have been individually associated with energy balance components and colorectal cancer. As such, Fusobacterium nucleatum, certain strains of Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis have been identified as driver microorganisms residing in the gut that are involved in colorectal cancer promotion [9-11]. Gut microbial characteristics, such as low diversity and increased abundances of Fusobacterium nucleatum and others, have been associated with the efficacy of cancer therapies and colorectal cancer survival [12-15]. In contrast, potential protective effects on colorectal cancer development and progression have been associated with Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and strains of Roseburia [16].

Although physical activity may beneficially impact gut microbial health, studies are sparse and have only been performed in healthy individuals and athletes [17-19]. With respect to obesity, clinical and pre-clinical studies have revealed alterations of gut microbiome diversity and abundances comparing obese vs. lean individuals [8,19-21]. The directionality of the obesity-gut microbiome association remains unclear. Overall, we and others have reported initial associations of energy balance components with the gut microbiome [11,17,22-26]. Yet, it is still unclear whether the gut microbiome is an interface of physical activity, obesity, and colorectal cancer. No one to date has investigated combinations of physical activity and obesity to discern possible differences and risk patterns in gut microbial profiles.

We are addressing this gap, by investigating for the first time alterations in the gut microbiome as mechanistic underpinning of the energy balance-colorectal cancer link in colorectal cancer patients. We further test whether physical activity may prevent or counteract dysbiosis of the gut microbiome due to obesity using combined physical activity and BMI groups.

Methods

Study population

The present study is conducted as part of the prospective ColoCare Study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02328677), an international cohort of newly diagnosed stage I-IV colorectal cancer patients (ICD-10 C18-C20) [27]. The ColoCare Study design has previously been described [27]. All analyses in this manuscript are based on data collected from n=179 patients with stage I-IV colorectal cancer enrolled between October 2010 and March 2018 at the study sites at the National Center for Tumor Diseases and University of Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany) (n=51) and the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) (Utah, USA) (n=128) with available stool samples. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the respective institutions and all patients provided written informed consent.

Processing and sequencing of fecal samples

Stool samples were collected by patients prior to surgery, suspended directly in RNAlater, and immediately frozen [28]. The samples were then processed and stored at -80°C. If patients received neoadjuvant treatment, stool samples were collected at least 2 weeks after completion of treatment. Standardized biospecimen collection questionnaires were used to collect specific quality control data and covariates, including date and time of stool specimen collection, and prior use of antibiotics and NSAIDs [27,28]. Stool samples were excluded if antibiotic use was reported within 4 weeks of biospecimen collection.

Total fecal microbial community DNA and RNA were extracted from stool samples using the PowerViral DNA/RNA Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and included 2 minutes of bead-beating at 4°C with a Mini-Beadbeater-16 (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Barcoded Illumina 16S rRNA gene sequencing libraries were then prepared by PCR (in triplicate for each sample) that contained primers with Illumina adapter sequences, barcodes on each primer and sequences targeting the V3 and V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene. The full oligonucleotide sequences used are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Triplicate PCRs from each sample were then combined, cleaned up with AxyPrep MAG PCR beads (Axygen), quantified and evenly multiplexed with other samples as we have previously described [29]. Multiplexed libraries were then sequenced across 2 lanes using an Illumina MiSeq platform at the HCI Genomic and Bioinformatics Shared Resource. Individual sample libraries that did not have enough reads for analysis (due to random sampling of highly multiplexed libraries) were re-sequenced in a second MiSeq run using the previously prepared sample’s library. Sample controls, mock microbial community DNA, and randomization of samples before extraction, preparation, and sequencing were applied as part of quality control. All extractions, library preparation, and sequencing were performed at a single laboratory (Round Lab, University of Utah) to prevent variabilities across different laboratories.

Raw sequences were processed to ASVs (amplicon sequence variants) and taxonomy was assigned as previously described using the QIIME2 (2020.2) framework [30]. Briefly, paired-end sequences were trimmed of primers, joined, then trimmed to 392 nucleotides and denoised with deblur. Taxonomy was assigned to representative sequences of each ASV using the Greengenes reference set (13_8) trimmed to the amplified region. ASVs with less than 0.1% abundance in >50% of samples were excluded from the analyses. Abundances were used to calculate alpha diversity metrics (Shannon index, Simpson index, Observed species) and Bray Cutis dissimilarity.

Physical activity and body mass index (BMI) assessments

Physical activity assessment

Recreational physical activity within the year before surgery was assessed using an adapted version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) questionnaire [31]. The summation of duration (hours) and frequency (per week) of moderate to vigorous activity was calculated in metabolic equivalent tasks hours per week (MET hrs/wk). The assignment of MET values follows the most recent Compendium of Physical Activities [32] and the questionnaire has previously been validated in a large international cohort [33].

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI (kg/m2) at baseline (pre-surgery) was abstracted from medical charts. We conducted a blinded review of a subset of charts (10%, n=250) across sites to ensure quality of the data abstraction.

Statistical analyses

Moderate activity was defined as 3.5 to 6 MET hrs/wk and vigorous activities as ≥6 MET hrs/wk [34]. Thus, at least 8.75 MET hrs/wk meet the guidelines of at least 150 minutes (=2.5 hrs) of moderate to vigorous activity as recommended for cancer survivors [35,36]. Accordingly, patients were categorized into either ‘inactive’ (<8.75 MET hrs/wk) or ‘active’ (≥8.75 MET hrs/wk) based on physical activity levels and into either ‘normal weight’ (BMI: ≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2), ‘overweight (BMI: ≥25 and <30 kg/m2), or obese’ (BMI: ≥30 kg/m2) based on BMI [37]. Combining physical activity and BMI information, patients were further grouped into: 1) ‘normal weight/active’ (≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2, ≥8.75 MET hrs/wk), 2) ‘normal weight/inactive’ (≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2, <8.75 MET hrs/wk), 3) ‘overweight/obese/active’ (≥25 kg/m2, ≥8.75 MET hrs/wk), and 4) ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ (≥25 kg/m2, <8.75 MET hrs/wk).

Mean values and standard deviations for normally distributed continuous variables and interquartile range (IQR) for skewed continuous variables (physical activity and CRP levels), as well as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables to describe patient characteristics were computed. Alpha- and beta-diversity metrics were compared by physical activity and BMI groups using ANCOVA and post-hoc Tukey’s Honest Significance Difference test. Diversity metrics were also compared by clinical characteristics including stage at diagnosis and tumor site. Differential abundances by physical activity and BMI groups were tested using Wald-test. False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was used to rank and correct raw and adjusted p-values for multiple testing using the Benjamin-Hochberg method [38]. Baseline characteristics were tested for potential confounding (sex, age, race, tumor stage and site), neoadjuvant treatment, antibiotic, aspirin and/or NSAID use, study site, and systemic inflammation [C-reactive Protein (CRP) levels, measured in blood samples collected 2-4 weeks prior to surgery, using Meso-Scale Discovery assays] and effect modification (sex, tumor stage and site). Sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding patients who received neoadjuvant treatment (n=50) or who were diagnosed with stage IV (n=15). Robustness of the model and confounding effects were assessed using standard methods, including an evaluation whether risk estimates changed >10% after inclusion of a covariate. The final models included sex, tumor stage, neoadjuvant treatment, and study site. All analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.4) and RStudio (version 1.4.1717) using the ‘Phyloseq’ and ‘DESeq2’ packages [39,40].

Results

Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Patients were on average 62 years old, 61% were male, and 6% Non-White. Most patients were diagnosed with stage II (27%) or stage III (41%) colorectal cancer and 52% of tumors were located in the rectum. Patients reported an average physical activity level of 11.2 MET hrs/wk and 40% were categorized as ‘active’. Most patients were overweight or obese (67%, n=120) and had an average BMI of 27.3 kg/m2. Distributions within the combined physical activity and BMI groups were as follows: n=26 (15%) ‘normal weight/active’, n=33 (18%) ‘normal weight/inactive’, n=46 (26%) ‘overweight/obese/active’, n=74 (41%) ‘overweight/obese/inactive’. Demographic and clinical characteristics by sex and tumor site are presented in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics [n (%) unless stated otherwise]

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 62 (12) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 69 (39) |

| Male | 110 (61) |

| Race | |

| White | 168 (94) |

| Non-White | 11 (6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 176 (98) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| I | 44 (24) |

| II | 48 (27) |

| III | 73 (41) |

| IV | 15 (8) |

| Tumor site | |

| Colon | 86 (48) |

| Rectum | 93 (52) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | |

| Yes | 50 (28) |

| No | 127 (72) |

| Physical activity (MET hrs/wk) | |

| Active (<8.75 MET hrs/wk) | 72 (40) |

| Inactive (≥8.75 MET hrs/wk) | 107 (60) |

| Mean (IQR) | 11.2 (16.23) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Normal weight (≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2) | 59 (32) |

| Overweight (≥25 and <30 kg/m2) | 76 (43) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 44 (25) |

| Mean (SD) | 27.3 (5.43) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoker | 73 (43) |

| Former smoker | 54 (32) |

| Current smoker | 43 (25) |

| Regular NSAID/Aspirin use | |

| Yes | 50 (32) |

| No | 106 (68) |

| Systemic inflammation | |

| C-reactive protein (CRP), mg/L, mean (IQR) | 11.5 (9.20) |

Data are not yet abstracted on n=2 patients for neoadjuvant treatment, and data is missing for n=9 on smoking status, n=23 for NSAID/aspirin use; SD - standard deviation; IQR - interquartile range; MET - metabolic equivalent per tasks.

The gut microbiome of active and normal weight patients is more diverse than that of inactive patients

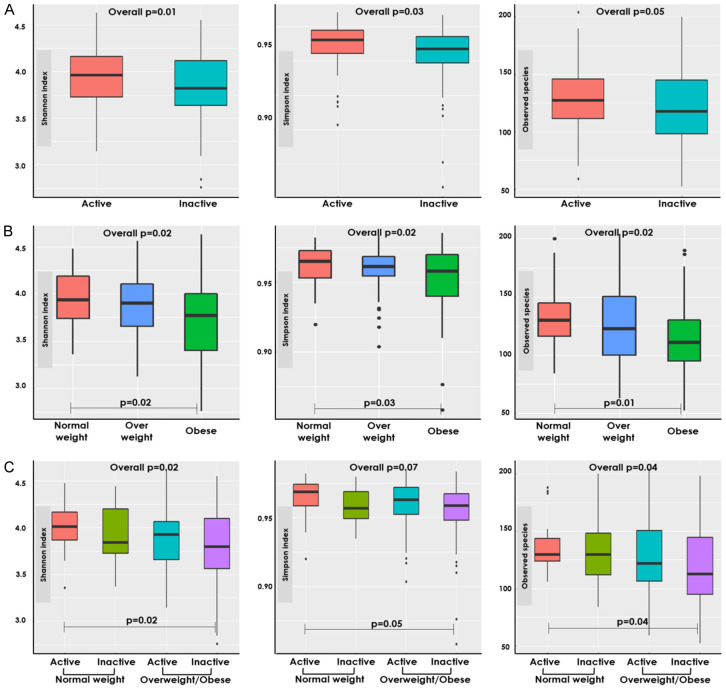

‘Inactive’ patients had a statistically significantly lower alpha diversity as compared to ‘active’ patients (Shannon index: P=0.01, Simpson index: P=0.03, Figure 1A). Associations were slightly stronger among patients diagnosed with stage III cancer, yet effect modification was not statistically significant. Alpha diversity metrics differed significantly by BMI groups (P=0.02, respectively for each metric). Post-hoc analyses revealed that ‘obese’ patients had lower alpha diversity compared to ‘normal weight’ patients (Shannon index: P=0.02, Simpson index: P=0.03, Observed species: P=0.01, Figure 1B). In combination, the gut microbiome of ‘normal weight/active’ patients was more diverse compared with ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ patients (Shannon index: P=0.02, Observed species: P=0.04, Figure 1C). We investigated associations between clinical characteristics, including stage at diagnosis, tumor site, and neoadjuvant treatment, to ensure that these alterations are specifically associated with energy balance components, and exclude confounding. Alpha diversity was not statistically significantly associated with either clinical characteristic (P=0.15-.80). No statistically significant differences were observed with Bray Cutis dissimilarity and physical activity and BMI groups (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Alpha diversity metrics by physical activity and BMI groups. Comparison of alpha diversity indices across: (A) Physical activity groups: active (≥8.75 METs hrs/wk) and inactive (<8.75 METs hrs/wk). (B) BMI groups: normal weight (≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (≥25 kg/m2). (C) Combined physical activity and BMI groups. Alpha metrics are presented from left to right in the following order: Shannon index, Simpson index, Observed species. ANCOVA was used to test overall differences between combined physical activity and BMI groups. Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test was used to adjusted for multiple testing and to test differences between each group. The statistically significant (P<0.05) group comparisons are shown.

Differences were observed by sex and tumor site (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Associations of gut microbiome diversity with physical activity were stronger among men. Alpha diversity was higher among ‘active’ vs. ‘inactive’ men (Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, associations with BMI were stronger among women. ‘Normal weight’ female patients had a significantly lower observed species alpha diversity as compared to ‘obese’ female patients. In combination, physical activity and BMI groups were stronger associated alpha diversity among men. ‘Normal weight/active’ male patients had a more diverse microbiome as compared to ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ male patients. Significantly higher Shannon and observed species alpha diversity metrics were also observed among ‘overweight/obese/active’ as compared to ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ male patients.

Associations between energy balance components and gut microbiome diversity were stronger and statistically significant only in colon cancer patients (Supplementary Figure 3). ‘Normal weight’ patients had a more diverse gut microbiome than ‘obese’ patients among colon cancer patients. Among colon cancer patients, ‘normal weight/active’ patients had an increased alpha diversity as compared to ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ patients. No differences by individual or combined physical activity and BMI groups were observed for patients with rectal cancer. Excluding patients who received neoadjuvant treatment or were diagnosed with stage IV did not substantially impact the results.

Relative abundances of several taxa differ by physical activity and BMI groups

A median of 13,342 reads were generated per sample. The number of reads by individual and combined physical activity and BMI groups are referred to in the respective tables. Overall, 3,072 individual taxa including 9 phyla and 152 genera were identified. Taxonomic classifications of the most dominant phyla and genera are visualized in Supplementary Figure 4.

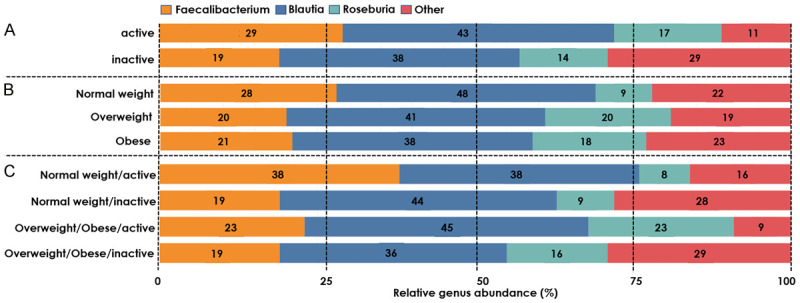

We observed several differences comparing ‘active’ and ‘inactive’ patients. At the phylum level, ‘inactive’ patients had a 0.59 log2-fold change in mean normalized counts of Actinobacteria (P=0.02) (Supplementary Table 2). At the genus level, higher relative abundances of Blautia (43%) and Faecalibacterium (29%) emerged among ‘active’ patients compared to ‘inactive’ patients (38% and 19%, respectively) (Figure 2). Among less dominant genera, decreased abundances of Succinivibrio and Succiniclasticum were observed in ‘inactive’ vs. ‘active’ patients (P=0.05 and P=2.05e-20, respectively) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The relative abundance (%) of genera by physical activity and BMI groups. A. Physical activity groups: active (≥8.75 METs hrs/wk) and inactive (<8.75 METs hrs/wk). B. BMI groups: normal weight (≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (≥25 kg/m2). C. Combined physical activity and BMI groups.

Table 2.

Differential abundance (mean normalized counts) at genus level by individual BMI and physical activity groups

| Physical activity [inactive (n=107) vs. active (n=72)] | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genus | Mean of normalized counts for all samples | Log2 fold change (SE) | Wald test | BH adjusted |

| p-value | p-value | |||

|

| ||||

| Succiniclasticum | 30.4 | -10.2 (2.99) | 0.0006 | 0.05 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -29.3 (3.00) | 1.31e-22 | 2.05e-20 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Overweight (n=76) vs. normal weight (n=59) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genus | Mean of normalized counts for all samples | Log2 fold change (SE) | Wald test | BH adjusted |

| p-value | p-value | |||

|

| ||||

| Olsenella | 0.45 | -24.1 (3.51) | -6.22e-12 | 1.97e-10 |

| Unclassified Mogibacteriaceae | 6.83 | -1.19 (0.36) | 0.0008 | 0.01 |

| Anaerococcus | 0.60 | -29.8 (3.35) | 5.65e-19 | 5.37e-17 |

| Eubacterium | 0.58 | -7.00 (2.29) | 0.002 | 0.03 |

| Clostridium | 0.37 | -25.3 (3.51) | 5.79e-13 | 2.75e-11 |

| Succiniclasticum | 0.32 | -14.1 (2.51) | 0.00006 | 0.001 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -22.4 (3.51) | 1.71e-10 | 4.07e-9 |

|

| ||||

| Obese (n=44) vs. normal weight (n=59) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genus | Mean of normalized counts for all samples | Log2 fold change (SE) | Wald test | BH adjusted |

| p-value | p-value | |||

|

| ||||

| Adlercreutzia | 0.72 | -2.01 (0.58) | 0.0006 | 0.03 |

| Ruminococcus | 44.2 | 1.16 (0.36) | 0.001 | 0.05 |

| Clostridium | 0.37 | -27.2 (4.12) | 4.10e-11 | 6.40e-9 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -22.7 (4.11) | 3.25e-8 | 0.000003 |

All tests were adjusted for sex, stage at diagnosis, neoadjuvant treatment, and study site; SE - Standard error; BH - Benjamin Hochberg; statistically significant: P<0.05. Note: A median of 15,097 reads were generated per sample from ‘active’ patients as compared to a median of 11,252 reads per sample from ‘inactive’ patients. A median of 12,263, 10,229, and 17,491 reads were generated per sample from ‘normal weight’, ‘overweight’, and ‘obese’, respectively. Only statistically significant genera are shown.

No statistically significant differences by BMI groups were observed at the phylum level (Supplementary Table 2). At the genus level, Blautia (48% vs. 38%) and Faecalibacterium (28% vs. 21%) were enriched, while Roseburia (9% vs. 18%) was diminished in ‘normal weight’ patients compared to ‘overweight/obese’ patients (Figure 2). Clostridium and Succinivibrio abundances were lower among both ‘overweight’ [-25.3 (±3.51), P=2.75e-11; -22.4 (±3.51), P=4.07e-9; respectively] and ‘obese’ patients [-27.3 (±4.12), P=6.40e-9; -22.7 (±4.11), P=0.000003; respectively] compared to ‘normal weight’ patients (Table 2). ‘Overweight’ patients had further diminished abundances of Olsenella, unclassified Mogibacteriaceae, Anaerococcus, Eubacterium, Clostridium, and Succiniclasticum (Table 2). Aldercreutzia abundances was decreased, while Rumminococcus abundance was decreased among ‘obese’ patients compared to ‘normal weight’ patients (Table 2).

The investigation of combined physical activity/BMI groups revealed several differentially abundant phyla and genera. At the phylum level, ‘overweight/obese/active’ patients had a lower abundance of Fusobacteria as compared to ‘normal weight/active’ patients (P=0.04, Supplementary Table 3). Conversely, ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ patients had enriched Actinobacteria compared to ‘normal weight/active’ patients (P=0.03, Supplementary Table 3).

At the genus level, ‘normal weight/active’ and ‘overweight/obese/active’ had higher abundances of Faecalibacterium (38% and 23%, respectively) compared to their inactive counterparts (‘normal weight/inactive’: 19%, ‘overweight/obese/inactive’: 19%) (Figure 2). Bifidobacterium was only present among ‘overweight/obese/active’ (7%) and ‘inactive’ (5%) patients. ‘Normal weight/inactive’ and ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ patients had diminished Succiniclasticum and Succinivibrio abundances as compared to their ‘active’ counterparts (Table 3). ‘Normal weight/inactive’ and ‘overweight/obese/active’ patients had diminished Succiniclasticum abundance, while having enriched Pyramidobacter abundance compared to their ‘normal weight/active’ counterpart. Succinivibrio abundance was also lower among ‘overweight/obese/active’ compared to ‘normal weight/active’ patients [-24.7 (±4.50), P=0.000003]. In comparison with ‘normal weight/active’ patients, ‘overweight/obese/active’ patients showed differential abundance of Peptoniphilus [-29.0 (±5.01), P=0.000001] and ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ patients had differentially abundant RFN20 [-29.1 (±4.50), P=9.92e-7]. Excluding patients who received neoadjuvant treatment or were diagnosed with stage IV did not substantially impact the results.

Table 3.

Differential abundance (mean normalized counts) at genus level by combined BMI and physical activity groups

| Normal weight/inactive (n=33) vs. normal weight/active (n=26) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genus | Mean of normalized counts for all samples | Log2 fold change (SE) | Wald test | BH adjusted |

| p-value | p-value | |||

|

| ||||

| Succiniclasticum | 0.26 | -30.0 (5.24) | 1.01e-8 | 0.000002 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -21.0 (5.24) | 0.00006 | 0.005 |

| Pyramidobacter | 0.21 | 18.8 (5.24) | 0.0003 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Overweight/obese/active (n=46) vs. normal weight/active (n=26) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genus | Mean of normalized counts for all samples | Log2 fold change (SE) | Wald test | BH adjusted |

| p-value | p-value | |||

|

| ||||

| Peptoniphilus | 0.12 | -29.0 (5.01) | 6.52e-9 | 0.000001 |

| Succiniclasticum | 0.26 | -18.3 (5.01) | 0.0003 | 0.01 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -21.7 (5.01) | 0.00001 | 0.0004 |

| Pyramidobacter | 0.21 | 18.2 (5.01) | 0.0003 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Overweight/obese/inactive (n=74) vs. normal weight/active (n=26) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genus | Mean of normalized counts for all samples | Log2 fold change (SE) | Wald test | BH adjusted |

| p-value | p-value | |||

|

| ||||

| RFN20 | 0.10 | -29.1 (4.50) | 6.36e-9 | 9.92e-7 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -24.7 (4.50) | 4.02e-8 | 0.000003 |

|

| ||||

| Overweight/obese/inactive (n=74) vs. overweight/obese/active (n=46) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Succiniclasticum | 0.26 | -30.0 (5.22) | 9.05e-9 | 0.000001 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.38 | -21.2 (5.22) | 0.00005 | 0.004 |

All tests were adjusted for sex, stage at diagnosis, neoadjuvant treatment, and study site; BMI - body mass index; SE - Standard error; BH - Benjamin Hochberg. Note: A median of 14,675 reads was generated per sample from ‘nomal weight/active’ patients compared to 10,692 reads from ‘normal weight/inactive’ patients, 15,615 reads from ‘overweight/obese/active’, and 11,808 reads from ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ patients. Only statistically significant genera are shown.

Discussion

Here, we provide the first evidence for an association between higher physical activity levels and greater gut microbiome diversity and differential abundances among colorectal cancer patients. Our results indicate that physical activity may independently be associated with gut microbiome health in colorectal cancer patients. These results underscore the need to further investigate the gut microbiome and its secreted metabolites as molecular mechanism of the energy balance-colorectal cancer link.

Our data indicate that physical activity may beneficially modulate the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer patients. First, we observed that alpha diversity was lower among ‘inactive’ patients and lowest among ‘overweight/obese/inactive’. Alpha diversity describes the number of microbial species relative to its abundance within one sample and has been identified as an indicator of heathy state with higher diversity indicating improved health [41]. As such, lower microbial diversity has been previously identified among colorectal cancer patients compared to healthy controls [10]. Studies in athletes have identified increased alpha diversity among athletes compared to healthy controls (P<0.01) [18,42].

Second, we identified differences in microbial abundances by physical activity. ‘Active’ patients had enriched abundances of multiple dominant genera including Faecalibacterium and Blautia and less dominant genera including Succiniclasticum and Succinivibrio. At the phylum level, ‘active’ patients had lower Actinobacteria abundance. These findings are consistent with studies showing higher abundances of Succinivibrio, Faecalibacterium prausnitztii, Roseburia hominis, and Akkermansia muciniphila in healthy individuals and athletes [19,42]. Faecalibacterium and Succinivibrio have been linked to health-promoting attributes including decreased risk for colorectal cancer [10,43]. Although lower abundance of Actinobacteria has been associated with increased colorectal cancer risk [44], other studies reported cancer-promoting associations of some Actinobacteria-related species [10]. Altered gut microbiome diversity and abundances in ‘active’ patients may, therefore, partially explain the complex biological mechanisms underlying the health benefits of physical activity on colorectal cancer patients. Observed changes in both ‘normal weight/active’ and ‘overweight/obese/active’ patients pointing to physical activity independently being associated with gut microbial compositions. Due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, assumptions about the directionality of the association between physical activity and the gut microbiome cannot be made. However, a recently published longitudinal study testing the effect of a 6 week supervised exercise intervention supports our assumption of physical activity impacting changes in the gut microbiome composition and functionality [17,19].

We report that ‘overweight’ and ‘obese’ patients have lower microbial diversity, reduced abundances of Faecalibacterium, Olsenella, Mogibacteriaceae, Eubacterium, Adlercreutzia, Succinivibrio, Succiniclasticum, and higher abundance of Ruminococcus as compared to ‘normal weight/active’ patients. Consistent with our findings, lower gut microbiome diversity, greater abundances of Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, Mollicutes and Lactobacillus and lower abundances of Faecalibacterium, Succinivibrio, and Bacteroidetes have been observed in pre- and clinical studies comparing overweight/obese vs. healthy state [43,45-47]. A recent meta-analysis assessing the mitigating effect of the gut microbiome on the obesity-colorectal cancer link yielded inconclusive results suggesting a weak mitigation by cancer-associated taxa [22]. Overall, our results support the existing evidence indicating negative effects of BMI on gut microbiome among colorectal cancer patients indicating alterations in the gut microbiome as an interface of the obesity-colorectal cancer link.

A key question of energy balance research is the investigation of “metabolically healthy obese” and combinations of activity and obesity. A proportion of obese individuals do not represent the obesity-characterized phenotype of chronic systemic inflammation and insulin resistance [6,7]. Our results indicate that increased physical activity may counteract obesity-induced dysbiosis of the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer patients. For example, gut microbiome diversity was lowest among ‘overweight/obese/inactive’ as compared to ‘normal weight/active’ patients. In addition, Faecalibacterium was enriched in ‘active’ patients regardless of BMI and Succinivibrio abundance was diminished among ‘overweight/obese’ patients, but, even lower in ‘inactive/overweight/obese’ patients. Taken together, physical activity may benefit obese patients by counteracting obesity-induced metabolic effects in colorectal cancer patients.

We observed differences in gut microbiome diversity by individual physical activity groups and combined physical activity and BMI groups among male patients. In contrast, alpha diversity metrics by individual BMI groups were significantly different among female, but not among male patients. Sex-dependent differences in the gut microbiome have previously been reported [48-50]. Higher diversity has been detected in females as compared to male individuals [49]. Other results indicate an association between the gut microbiome and the regulation of sex hormones through the control of signaling pathways such as the toll-like receptor and flavin monooxygenase signaling [48,50]. Our results indicate that physical activity may have stronger associations with gut microbiome diversity among males, perhaps attributable to their lower baseline diversity. On the other hand, differences in body composition by sex including adipose tissue and muscle mass distributions may explain the observed difference in gut microbiome diversity by BMI groups in female, but not male patients.

We further observed different effect sizes by tumor site. Among colon cancer patients, microbiome diversity significantly differed by individual and combined physical activity and BMI groups [47,48,51,52]. This is consistent with the prior literature demonstrating that physical activity and BMI are more strongly associated with colon than rectum cancer risk and survival [51,52]. Further, microbial composition and diversity differ by anatomical location in healthy individuals, as well as colorectal cancer patients [10,53].

This study has several strengths and limitations. To date, this is the first study investigating the gut microbiome in the physical activity-colorectal cancer link. It is further the first investigation testing whether greater recreational physical activity levels may counteract some of the negative effects of excess body weight on gut microbiome dysbiosis in colorectal cancer patients. Gut microbiome abundances and diversities were measured following state-of-the-art standardized protocols for biospecimen collection, processing, storage, and analyses. Quality controls were implemented in our laboratory protocols and methods to account for measurement errors such as batch-effects and multiple testing were applied at the analyses stage. Factors including antibiotic use and systemic inflammation that may influence the composition of the gut microbiome were assessed at the time of the stool collection. Another strength is the geographical variability in our study population which broadens the range of exposures. To account for potential systematic differences by geography (e.g., diet), all analyses were adjusted for study site (without substantial impact on results).

16S rRNA gene sequencing provides a valuable, yet limited, microbiome assessment, as it may lack accuracy in classifying taxa on the species-level and has a low detection rate for low abundant species. For example, colorectal cancer-specific species such as Fusobacterium nucleatum and Escherichia coli could not be identified. However, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has been a valuable method for detecting initial targets that can be further explored in metagenomic sequencing studies. Although metabolic pathways can be imputed and inferred [54]. they cannot be measured directly using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Future studies should expand on our findings by using more comprehensive assessments including metagenomics and metatranscriptomics sequencing to elaborate on the observed association on the species level, as well as the functionality and dynamic changes within microbial communities. Further, a future study among cancer-free individuals would add further information on generalizability of the associations observed beyond colorectal cancer patients. Mediation analyses on the association between energy balance components and colorectal cancer survival have to be conducted to identify the gut microbiome as an underlying mechanism. The self-reported nature of the physical activity assessment may have resulted in misclassification. Any misclassification would be non-differential and, therefore, any observed effects can be assumed to be lower than the actual effect. Future studies should further incorporate measurements of other microbiome-associated factors such as detailed dietary assessments.

In conclusion, our study reveals the gut microbiome associated with the energy balance-colorectal cancer link, with strongest differences observed for patients who are physically active vs. inactive. Our results further suggest that increased physical activity may prevent or counteract dysbiosis of the gut microbiome due to obesity. Intervention studies testing the effect of exercise on the gut microbiome in cancer patients will be critical to provide further mechanistic insights. Studies should further investigate different effect sizes by exercise type, intensity, and body composition using more comprehensive measurements.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01 CA206110, R01 CA189184, R01 CA207371, R01 CA211705, R01 CA254108, T32 HG008962, KL2TR002539), Stiftung LebensBlicke, German Consortium of Translational Cancer Research, (DKTK), German Cancer Research Center, Matthias Lackas Stiftung, Claussen-Simon Stiftung, Huntsman Cancer Foundation, Immunology, Inflammation, and Infectious Disease Initiative, and Cancer Control and Population Health Sciences (CCPS) at the University of Utah, ERA-NET, and the JTC 2012 call on Translational Cancer Research (TRANSCAN).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Chan AT, Chan JA, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:3527–3534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Blarigan EL, Meyerhardt JA. Role of physical activity and diet after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:1825–1834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JC, Meyerhardt JA. Obesity and energy balance in GI cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:4217–4224. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.8699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulrich CM, Himbert C, Holowatyj AN, Hursting SD. Energy balance and gastrointestinal cancer: risk, interventions, outcomes and mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:683–698. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caan BJ, Meyerhardt JA, Kroenke CH, Alexeeff S, Xiao J, Weltzien E, Feliciano EC, Castillo AL, Quesenberry CP, Kwan ML, Prado CM. Explaining the obesity paradox: the association between body composition and colorectal cancer survival (C-SCANS Study) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1008–1015. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacobini C, Pugliese G, Blasetti Fantauzzi C, Federici M, Menini S. Metabolically healthy versus metabolically unhealthy obesity. Metabolism. 2019;92:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blüher M. Metabolically healthy obesity. Endocr Rev. 2020;41:bnaa004. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedenreich CM, Ryder-Burbidge C, McNeil J. Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behavior in cancer etiology: epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:790–800. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wirbel J, Pyl PT, Kartal E, Zych K, Kashani A, Milanese A, Fleck JS, Voigt AY, Palleja A, Ponnudurai R, Sunagawa S, Coelho LP, Schrotz-King P, Vogtmann E, Habermann N, Niméus E, Thomas AM, Manghi P, Gandini S, Serrano D, Mizutani S, Shiroma H, Shiba S, Shibata T, Yachida S, Yamada T, Waldron L, Naccarati A, Segata N, Sinha R, Ulrich CM, Brenner H, Arumugam M, Bork P, Zeller G. Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2019;25:679–689. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, Amiot A, Böhm J, Brunetti F, Habermann N, Hercog R, Koch M, Luciani A, Mende DR, Schneider MA, Schrotz-King P, Tournigand C, Tran Van Nhieu J, Yamada T, Zimmermann J, Benes V, Kloor M, Ulrich CM, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Sobhani I, Bork P. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:766. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temraz S, Nassar F, Nasr R, Charafeddine M, Mukherji D, Shamseddine A. Gut microbiome: a promising biomarker for immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4155. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebersek M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1325. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09054-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi Y, Shen L, Shi W, Xia F, Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang Y, Sun X, Zhang Z, Zou W, Yang W, Zhang L, Zhu J, Goel A, Ma Y, Zhang Z. Gut microbiome components predict response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:1329–1340. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Cao Y, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Song M, Kostic AD, Giannakis M, Bullman S, Milner DA, Baba H, Giovannucci EL, Garraway LA, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C, Meyerson M, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut. 2016;65:1973–1980. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konstantinov SR, Kuipers EJ, Peppelenbosch MP. Functional genomic analyses of the gut microbiota for CRC screening. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mailing LJ, Allen JM, Buford TW, Fields CJ, Woods JA. Exercise and the gut microbiome: a review of the evidence, potential mechanisms, and implications for human health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2019;47:75–85. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Sullivan O, Cronin O, Clarke SF, Murphy EF, Molloy MG, Shanahan F, Cotter PD. Exercise and the microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2015;6:131–136. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1011875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen JM, Mailing LJ, Niemiro GM, Moore R, Cook MD, White BA, Holscher HD, Woods JA. Exercise alters gut microbiota composition and function in lean and obese humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50:747–757. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song M, Chan AT, Sun J. Influence of the gut microbiome, diet, and environment on risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:322–340. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott AJ, Alexander JL, Merrifield CA, Cunningham D, Jobin C, Brown R, Alverdy J, O’Keefe SJ, Gaskins HR, Teare J, Yu J, Hughes DJ, Verstraelen H, Burton J, O’Toole PW, Rosenberg DW, Marchesi JR, Kinross JM. International Cancer Microbiome Consortium consensus statement on the role of the human microbiome in carcinogenesis. Gut. 2019;68:1624–1632. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greathouse KL, White JR, Padgett RN, Perrotta BG, Jenkins GD, Chia N, Chen J. Gut microbiome meta-analysis reveals dysbiosis is independent of body mass index in predicting risk of obesity-associated CRC. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6:e000247. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bullman S, Pedamallu CS, Sicinska E, Clancy TE, Zhang X, Cai D, Neuberg D, Huang K, Guevara F, Nelson T, Chipashvili O, Hagan T, Walker M, Ramachandran A, Diosdado B, Serna G, Mulet N, Landolfi S, Ramon YCS, Fasani R, Aguirre AJ, Ng K, Élez E, Ogino S, Tabernero J, Fuchs CS, Hahn WC, Nuciforo P, Meyerson M. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science. 2017;358:1443–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.aal5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H, Stadlmayr A, Tang L, Lan Z, Zhang D, Xia H, Xu X, Jie Z, Su L, Li X, Li X, Li J, Xiao L, Huber-Schönauer U, Niederseer D, Xu X, Al-Aama JY, Yang H, Wang J, Kristiansen K, Arumugam M, Tilg H, Datz C, Wang J. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6528. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baxter NT, Ruffin MT 4th, Rogers MA, Schloss PD. Microbiota-based model improves the sensitivity of fecal immunochemical test for detecting colonic lesions. Genome Med. 2016;8:37. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogtmann E, Hua X, Zeller G, Sunagawa S, Voigt AY, Hercog R, Goedert JJ, Shi J, Bork P, Sinha R. Colorectal cancer and the human gut microbiome: reproducibility with whole-genome shotgun sequencing. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulrich CM, Gigic B, Böhm J, Ose J, Viskochil R, Schneider M, Colditz GA, Figueiredo JC, Grady WM, Li CI, Shibata D, Siegel EM, Toriola AT, Ulrich A. The colocare study: a paradigm of transdisciplinary science in colorectal cancer outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28:591–601. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisele Y, Mallea PM, Gigic B, Stephens WZ, Warby CA, Buhrke K, Lin T, Boehm J, Schrotz-King P, Hardikar S, Huang LC, Pickron TB, Scaife CL, Viskochil R, Koelsch T, Peoples AR, Pletneva MA, Bronner M, Schneider M, Ulrich AB, Swanson EA, Toriola AT, Shibata D, Li CI, Siegel EM, Figueiredo J, Janssen KP, Hauner H, Round J, Ulrich CM, Holowatyj AN, Ose J. Fusobacterium nucleatum and clinicopathologic features of colorectal cancer: results from the ColoCare Study. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2021;20:e165–e172. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kubinak JL, Petersen C, Stephens WZ, Soto R, Bake E, O’Connell RM, Round JL. MyD88 signaling in T cells directs IgA-mediated control of the microbiota to promote health. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephens WZ, Kubinak JL, Ghazaryan A, Bauer KM, Bell R, Buhrke K, Chiaro TR, Weis AM, Tang WW, Monts JK, Soto R, Ekiz HA, O’Connell RM, Round JL. Epithelial-myeloid exchange of MHC class II constrains immunity and microbiota composition. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109916. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Littman AJ, White E, Kristal AR, Patterson RE, Satia-Abouta J, Potter JD. Assessment of a one-page questionnaire on long-term recreational physical activity. Epidemiology. 2004;15:105–113. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000091604.32542.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt-Glover MC, Leon AS. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, Macera CA, Castaneda-Sceppa C. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1435–1445. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, Irwin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Gruenigen VE, Schwartz AL. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Body Mass Index - BMI. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi.

- 38.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: a bioconductor package for handling and analysis of high-throughput phylogenetic sequence data. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2012:235–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clarke SF, Murphy EF, Sullivan O, Lucey AJ, Humphreys M, Hogan A, Hayes P, Reilly M, Jeffery IB, Wood-Martin R, Kerins DM, Quigley E, Ross RP, Toole PW, Molloy MG, Falvey E, Shanahan F, Cotter PD. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut. 2014;63:1913. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verdam FJ, Fuentes S, de Jonge C, Zoetendal EG, Erbil R, Greve JW, Buurman WA, de Vos WM, Rensen SS. Human intestinal microbiota composition is associated with local and systemic inflammation in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:E607–615. doi: 10.1002/oby.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou YJ, Zhao DD, Liu H, Chen HT, Li JJ, Mu XQ, Liu Z, Li X, Tang L, Zhao ZY, Wu JH, Cai YX, Huang YZ, Wang PG, Jia YY, Liang PQ, Peng X, Chen SY, Yue ZL, Yuan XY, Lu T, Yao BQ, Li YG, Liu GR, Liu SL. Cancer killers in the human gut microbiota: diverse phylogeny and broad spectra. Oncotarget. 2017;8:49574–49591. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crovesy L, Masterson D, Rosado EL. Profile of the gut microbiota of adults with obesity: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:1251–1262. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobhani I, Bergsten E, Couffin S, Amiot A, Nebbad B, Barau C, de’Angelis N, Rabot S, Canoui-Poitrine F, Mestivier D, Pédron T, Khazaie K, Sansonetti PJ. Colorectal cancer-associated microbiota contributes to oncogenic epigenetic signatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:24285–24295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912129116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, McDowell A, Kim EK, Seo H, Lee WH, Moon CM, Kym SM, Lee DH, Park YS, Jee YK, Kim YK. Development of a colorectal cancer diagnostic model and dietary risk assessment through gut microbiome analysis. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0313-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, von Bergen M, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Danska JS. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science. 2013;339:1084–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.1233521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de la Cuesta-Zuluaga J, Kelley ST, Chen Y, Escobar JS, Mueller NT, Ley RE, McDonald D, Huang S, Swafford AD, Knight R, Thackray VG, Baranzini S. Age- and sex-dependent patterns of gut microbial diversity in human adults. mSystems. 2019;4:e00261-19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00261-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin JH, Park YH, Sim M, Kim SA, Joung H, Shin DM. Serum level of sex steroid hormone is associated with diversity and profiles of human gut microbiome. Res Microbiol. 2019;170:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clague J, Bernstein L. Physical activity and cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:550–558. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jayasekara H, English DR, Haydon A, Hodge AM, Lynch BM, Rosty C, Williamson EJ, Clendenning M, Southey MC, Jenkins MA, Room R, Hopper JL, Milne RL, Buchanan DD, Giles GG, MacInnis RJ. Associations of alcohol intake, smoking, physical activity and obesity with survival following colorectal cancer diagnosis by stage, anatomic site and tumor molecular subtype. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:238–250. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaga S, Lee S, Ji B, Andreasson A, Talley NJ, Agréus L, Bidkhori G, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Park J, Lee D, Proctor G, Ehrlich SD, Nielsen J, Engstrand L, Shoaie S. Compositional and functional differences of the mucosal microbiota along the intestine of healthy individuals. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14977. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71939-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langille MG, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Vega Thurber RL, Knight R, Beiko RG, Huttenhower C. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.