Surgical site infection (SSI) following joint replacement surgery, may lead to implant failure, higher morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospitalization and increased costs. 1 Staphylococcus aureus is the leading cause; it is responsible for half of all SSIs following hip or knee arthroplasty. 2 Infection with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is associated with greater morbidity and mortality than methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). 3

S. aureus is a normal skin and mucosal flora and asymptomatically colonizes up to one-third of the population. 4 SSI risk is significantly increased if patients are colonized with S. aureus. 5 Reducing colonization prior to surgery is considered a key measure to reducing SSI incidence. S. aureus screening and decolonization programs are effective in reducing SSI incidence and are widely used. 6

We investigated the contribution of a screening and decolonization protocol prior to hip or knee arthroplasty in reducing the incidence of S. aureus joint infections.

Methods

We identified patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, between January 1, 2012, and July 8, 2016, by extracting data from surveillance data collected by the infection prevention service. SSIs were defined as any wound-site infection involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, and/or deep soft tissue within 90 days of the procedure. 7

Patients scheduled for elective prosthetic hip or knee arthroplasty attended the preadmission clinic for screening groin and nasal swabs. If S. aureus was not detected on screening swabs, no decolonization treatment was prescribed. Patients positive for S. aureus were instructed to apply 2% mupirocin ointment to both nostrils twice daily and to shower each day using 2% chlorhexidine skin cleanser for the 5 days immediately prior to surgery. Emergency patients were not screened or decolonized unless screening had occurred in anticipation of elective surgery.

Patients were given antibiotic prophylaxis prior to surgery with cefazolin (1 g for <80 kg and 2 g for ≥80 kg, commencing within 1 hour of incision, with a repeat dose for surgery >4 hours) or vancomycin (1.5 g intravenously, commencing 30–120 minutes prior to incision).

Results

Cohort

Between January 1, 2012, and July 8, 2016, 1,268 patients underwent hip or knee prosthetic joint surgery (Supplementary Fig. 1). The mean age of this cohort was 71.4 years, and 63% were female.

Colonization

S. aureus colonization was detected in 256 (34%) of 754 screened patients; 242 (32%) were colonized with MSSA and 14 (2%) were colonized with MRSA. Patients undergoing revision surgery (n=128) had a MRSA colonization rate of 3% (n = 4) compared to 1% (n = 10) for those undergoing primary surgery (P = .45).

Surgical-site infections

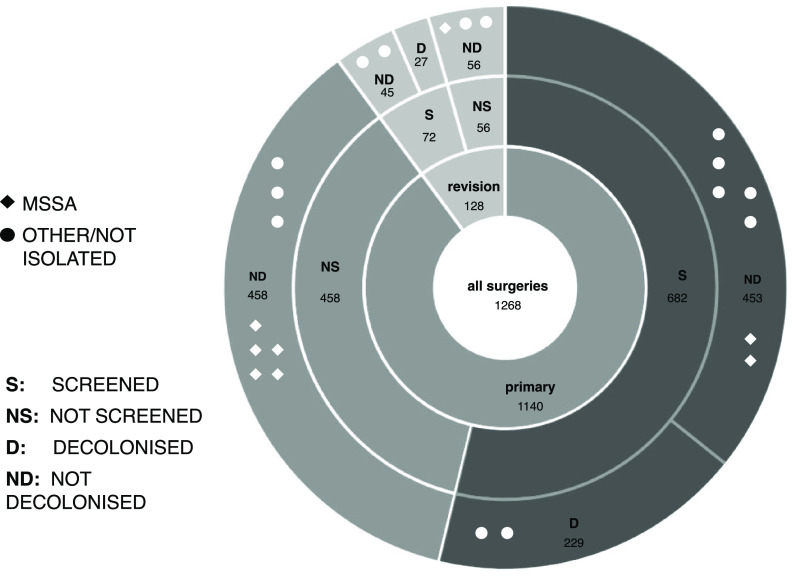

Of 1,268 patients, 22 (2%) developed infections, of whom 8 (36%) had S. aureus (all MSSA) (Supplementary Table 1). Elective revision surgeries had the highest infection rate of any cohort (4.0%, n = 4 of 99), and elective primary surgeries had the lowest infection rate (1.3%, n = 12 of 906; P = .06) (Supplementary Table 1). No patients colonized with S. aureus at screening (and hence prescribed the decolonization protocol) developed infections due to S. aureus (0%), compared to 8 S. aureus infections in the non-decolonized group (0.8%; P = .37) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Incidence of surgical-site infection (SSI) among different cohorts of surgical patients. The symbols represent organisms causing infection: methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA); organisms other than S. aureus or organisms that could not be cultured (other or not isolated). Between the January 1, 2012, and July 8, 2016, 1,268 patients underwent hip or knee prosthetic joint surgery. Of those, 754 were screened and 256 were decolonized. Of 453 patients screened but not decolonized, 7 primary surgical patients went on to develop an SSI (1.5%). The revision surgery group had the highest incidence for infection overall, with 5 patients (3.9%) who developed infection among 128 patients. The decolonized group had the lowest incidence of infection; no infection with S. aureus was observed in the decolonized group. No difference was observed in the frequency of infection due to other species between the decolonized and non-decolonized groups (0.8%; cf, 1.0%).

Because non-decolonized patients were more likely to have had emergency surgery and a different risk profile (Supplementary Table 2), we also restricted analysis to the elective primary surgery subgroup in which the decolonized and non-decolonized patient groups had similar risk factors for SSI (Supplementary Table 3). In this group of 906 patients, 10 (1.5%) of 679 non-decolonized patients developed infection (4 with S. aureus, 4 with other organisms, and 2 with no organism isolated) compared to 2 (0.9%) of 227 decolonized patients (no S. aureus but 2 other organisms) (P = .74 for any infection and P = .58 for S. aureus infections only) (Supplementary Table 4 online). Notably, of those who were screened and in whom S. aureus had not been detected (n = 446), there were 2 S. aureus infections.

Discussion

We observed no S. aureus infections among decolonized patients even though they were all previously colonized with S. aureus, a major independent risk factor for S. aureus infections in patients undergoing joint replacement surgery. 6

Studies already support the role of screening followed by decolonization of S. aureus–colonized patients. 6,8 Our results also suggest that a universal S. aureus decolonization program without initial screening should be considered. There are several issues with screening first and decolonizing only those who are S. aureus colonized. First, many patients do not receive screening. In our setting, only 59% of patients underwent screening prior to their arthroplasty procedure. Second, screening is not 100% sensitive for S. aureus carriage and depends on the anatomical sampling site and the timing of sampling. 9 Patients not colonized at the time of screening may be colonized at the time of surgery. Of 498 patients who were screened and in whom S. aureus was not detected, there were 2 subsequent S. aureus infections. Third, screening is resource intensive. Compared to preoperative screening and decolonization, universal decolonization has been shown to be more cost-effective. 10

This study had several limitations. S. aureus–colonized patients were prescribed the decolonization protocol, but we did not collect data on protocol adherence or whether carriage was cleared. However, poor adherence or failure of decolonization would have undermined the effectiveness of the intervention; nevertheless, no S. aureus infections occurred in the decolonized cohort. Our data were from only a single institution, numbers of infections were low, and the study was observational. These results may not be generalizable to other institutions, and we were not able to demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in infection rates.

With this decolonization protocol, no S. aureus infections occurred after arthroplasty, even among previously colonised patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Infection Prevention and Surveillance Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital for collation of data.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2022.315.

click here to view supplementary material

Financial support

S.T. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship (no. 1145033).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1. Whitehouse JD, Friedman ND, Kirkland KB, Richardson WJ, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections following orthopedic surgery at a community hospital and a university hospital: adverse quality of life, excess length of stay, and extra cost. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002;23:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Worth LJ, Bull AL, Spelman T, Brett J, Richards MJ. Diminishing surgical-site infections in Australia: time trends in infection rates, pathogens and antimicrobial resistance using a comprehensive Victorian surveillance program, 2002–2013. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edwards C, Counsell A, Boulton C, Moran CG. Early infection after hip fracture surgery: risk factors, costs, and outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wenzel RP, Perl TM. The significance of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and the incidence of postoperative wound infection. J Hosp Infect 1995;31:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramos N, Stachel A, Phillips M, Vigdorchik J, Slover J, Bosco JA. Prior Staphylococcus Aureus nasal colonization: a risk factor for surgical site infections following decolonization. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016;24:880–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bode LG, Kluytmans JA, Wertheim HF, et al. Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus . N Engl J Med 2010;362:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Healthcare Associated Infection Surveillance (VICNISS). Hospital Acquired Infection Project: Year 2 Report–March 2004. Melbourne: Victorian Government; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Rijen MML, Kluytmans JAJW. New approaches to prevention of staphylococcal infection in surgery. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;21:380–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Bouri K, El-Bouri W. Screening cultures for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a population at high risk for MRSA colonization: identification of optimal combinations of anatomical sites. Libyan J Med 2013;8:22755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stambough JB, Nam D, Warren DK, et al. Decreased hospital costs and surgical site infection incidence with a universal decolonization protocol in primary total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:728–734.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2022.315.

click here to view supplementary material