Abstract

Background

In February 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prioritised enforcement efforts against flavoured prefilled cartridge/pod electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), with the exception of tobacco and menthol. This study examined changes between prepriority enforcement (2018) and early postenforcement (February–June 2020) among adults on: ENDS flavours and devices used most often; location of last purchase of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (covered under the enforcement priority); and smoking and vaping.

Methods

Prevalence estimates came from 1608 adult frequent (≥weekly) ENDS users (current smokers (n=1072), ex-smokers (n=536)) who participated in the 2018 and/or 2020 US ITC Smoking and Vaping Surveys. Transitions between flavours/devices and changes in smoking/vaping were assessed among baseline respondents who were followed up in 2020 (n=360). Respondents self-reported the ENDS device (disposable, cartridge/pod or tank) and the flavor that they used most often: (1) tobacco flavors (tobacco/tobacco-menthol mix) or unflavored; (2) menthol/mint; (3) fruit/other flavors.

Results

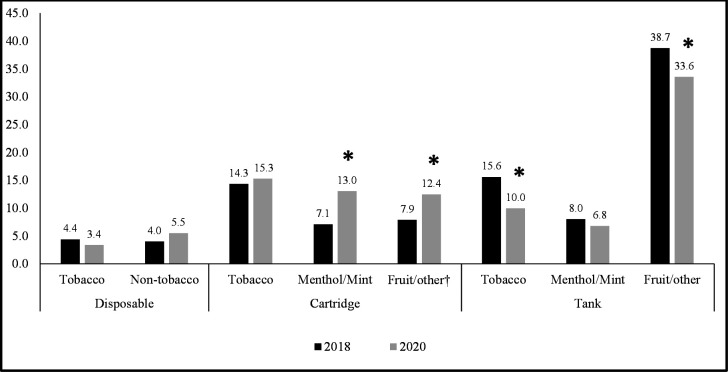

Compared to 2018, in the first 5 months of the 2020 enforcement priority, there were significant increases in the prevalence of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (7.9% to 12.4%,p=0.026) and menthol/mint cartridges (7.1% to 13.0%, p<0.01) and decreases in tobacco-flavoured tanks (15.5% to 10.0%,p=0.002) and fruit/other-flavoured tanks (38.7% to 33.6%,p=0.038). Fewer than 10% of adults used disposables in 2018 and 2020. Among the cohort sample, the most pronounced transitions between flavours/devices occurred among those who used flavoured cartridges covered under the enforcement priority (54.6% switched to a flavour and/or device excluded from enforcement). There was an increase in purchasing fruit/other-flavoured cartridges online and a decrease in retail locations except for vape shops. Overall, there were few changes in smoking and vaping behaviours.

Conclusions

Between 2018 and the early phase of the FDA’s 2020 enforcement priority, prevalence of menthol/mint and fruit/other-flavoured cartridges increased among adults. Half of vapers using cartridge flavours covered in the enforcement switched to other flavours and/or devices that were exempt, with the exception of disposables. The extent to which more comprehensive restrictions may be problematic for adults who prefer a range of ENDS flavours remains uncertain.

Keywords: non-cigarette tobacco products, electronic nicotine delivery devices, nicotine, public policy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Studies in the USA evaluating the impact of local laws restricting sales of flavoured tobacco products and electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) have generated mixed findings, with some showing a decrease in prevalence and sales of restricted flavoured ENDS.

A recent study found that the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) 2020 federal enforcement priority against flavoured cartridges did not reduce use of flavoured ENDS among youth vapers, who appear to have circumvented the flavour restrictions by using device types exempt from the restrictions, most notably disposables.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This is the first cohort study to examine changes in the flavour profile and ENDS devices most often used by adult current and former smokers before and after the US FDA’s 2020 federal enforcement priority, finding that the prevalence of usually using flavoured cartridges targeted by the enforcement priority increased between 2018 and 2020.

Half of adults who were using flavoured cartridges in 2018 (prior to enforcement) switched to flavours and/or devices exempt from the enforcement priority, but there was no shift to disposables.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

The findings indicate that ENDS devices and flavours used by adult current and former smokers are varied and may change over time and with available product offerings.

Policies that would have the greatest positive impact on youth and never-smokers, but little negative impact on adults who vape as a method of quitting smoking, should be a priority for regulation.

Introduction

The United States (USA) is the leading global electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) market.1 The prevalence of ENDS use in the USA has increased over the last decade among both youth2 and adults,3 with the greatest increases among 18–24 years olds.4 The rise in ENDS use is in part because of the availability of a wide variety of flavours and devices that make them appealing to use.5–8

ENDS are popular among US adolescents,9–12 with the most commonly used flavours being fruit (73.1%), mint (55.8%), menthol (37.0%) and other sweet flavours (36.4%).10 Prefilled cartridges/pods are the devices most commonly used among adolescents.10 12 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) became concerned with these trends, and thus prioritised enforcement efforts to reduce ENDS flavours and devices that are most popular among young people.13

Research has consistently demonstrated that flavours play a role among adults in ENDS initiation, continued use7 14–17 and facilitating switching from smoking to vaping.14 Adults use a wide range of flavours and commonly use non-tobacco flavoured ENDS.14–19 However, flavour preferences appear to differ by smoking status, where current smokers (dual users who smoke and vape) prefer tobacco flavours and ex-smokers (exclusive vapers) prefer fruit flavours.15 17 19 Flavour preferences also differ by age, with younger adults preferring fruit, and older adults preferring tobacco flavour.7 17 19 It is unclear whether flavour preferences and patterns of use would change under flavour restrictions; however, reducing access to non-tobacco flavours may discourage some smokers from switching to ENDS.

Although no ENDS product had been authorised to be marketed in the USA until October 2021,20 in January 2020, the FDA announced that it would prioritise its enforcement efforts against the manufacture, distribution and sale of flavoured cartridge ENDS products, with the exception of tobacco and menthol flavours.21 Disposable and tank (refillable) devices were excluded from enforcement. Following the implementation of the policy in February 2020, few changes in flavours were observed among youth (fruit remained the most commonly used flavour)10 12; however, there was a decrease in usual use of prefilled cartridge brands, such as JUUL, and a surge in the use of disposable products, particularly Puff Bar.12 To date, we are unaware of any studies that have investigated changes in ENDS flavours and devices used by adults, particularly for products that were targeted by the 2020 federal policy (‘fruit/other-flavoured cartridges’).

This study fills a research gap by examining the usual use of flavoured ENDS among adult current smokers and ex-smokers before and after the 2020 policy shift. Specifically, we examined changes between pre-enforcement (2018) and early postenforcement (February–June 2020) among adults on ENDS flavours, devices, and flavour–device combinations used most often, and location of last purchase of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges in 2018 and 2020. Supplemental analyses examined changes in smoking and vaping between surveys.

Methods

Study design and population

Data are from Wave 2 (22 February 2018–9 July 2018) and Wave 3 (24 February 2020–2 June 2020) of the US arm of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping (ITC 4CV) Survey, a longitudinal cohort survey of adults (≥18 years) from Canada, the USA, England and Australia. Using a stratified sampling design, respondents were recruited from web-based panels as established cigarette smokers (≥monthly, smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime), recent ex-smokers (quit ≤2 years ago) or current ENDS users (vape ≥weekly). Cohort respondents were followed across survey waves, and those lost to attrition were replenished using the same sampling design. The study was reviewed and cleared by research ethics committees in each country, and all respondents provided informed consent. Further details about the methods can be found elsewhere.22–24

Eligible respondents for this study included US residents who were frequent ENDS users (vape≥weekly) who were currently smoking (smoke≥monthly; referred to herein as ‘dual users’) or had quit smoking (<5 years; ‘ex-smokers’) at the time of the survey. Respondents with complete data on ENDS flavour/device use in 2018 and/or 2020 were included in the prevalence analysis. Respondents who completed the 2018 survey and were followed up in 2020 were included in the transition analyses.

At baseline (2018), 919 US frequent ENDS users completed the survey, and 373 (40.6%) were retained in 2020. The resulting sample included 360 eligible respondents (200 dual users and 160 ex-smokers) who had complete ENDS flavour and device data at baseline; four respondents were missing flavour or device data in 2020, leaving 356 for the transition analyses.

Measures

The complete Wave 2 and Wave 3 US surveys can be found on the ITC Project website.25 26 The following variables were used in this study:

ENDS use

“How often, if at all, do you currently use vaping products (ie, vape)?” Response options included: ‘daily’, ‘less than daily, but at least once a week’, ‘less than weekly, but at least once a month’, ‘less than once a month, but occasionally’ or ‘not at all’. Respondents who reported vaping less than weekly were excluded from the analyses.

ENDS flavour

Daily and weekly ENDS users were subsequently asked: “Which of the following e-liquid flavours have you used in the past 30 days? (select all that apply)”: tobacco; mix of tobacco and menthol; menthol or mint; fruit; candy, desserts, sweets; chocolate; clove or other spice; coffee; a non-alcoholic drink (soda, energy drinks or other beverages); an alcoholic drink (wine, whisky, cognac, margarita or other cocktails); and unflavoured e-liquid. Those who selected multiple flavours were asked what flavour they used most often. Respondents were categorised into one of three flavour groups based on the flavour they used most often: (1) tobacco, tobacco–menthol mix and unflavoured; (2) menthol/mint; or (3) fruit/other.

ENDS device

Respondents also reported the type of ENDS device that they used most often: “Which of the following best describes the TYPE of vaping device you currently use most?” Response options included: ‘it is disposable, not refillable (non-rechargeable)’; ‘it uses replaceable pre-filled cartridges or pods (rechargeable)’; or ‘it has a tank that you fill with liquids (rechargeable)’. The three types of devices were categorized as: disposables, cartridges, and tanks.

Flavour–device combinations

Prevalence data were assessed using the following combinations:

Cartridges: tobacco/menthol tobacco mix/unflavoured; menthol/mint; fruit/other.

Tanks: tobacco/menthol tobacco mix/unflavoured; menthol/mint; fruit/other.

Disposables: tobacco/unflavoured; all non-tobacco flavours (disposable ENDS use among adults was low in this study; thus, we were unable to categorise disposables into the three flavour groups and instead consolidated flavours into two groups).

Location of last purchase

“The LAST TIME you purchased cartridges or pods, where did you make this last purchase?” Response options were categorised as: online; vape shop; other retail location (tobacco specialty shop, gas station, supermarket and convenience store); and somewhere else (temporary or mobile sales location, outside the country or don’t remember).

Covariates

Sociodemographic data

Sociodemographic data, including age group, sex, income and education, were collected by commercial panel firms and verified at the time of survey completion (see table 1 for categorical descriptions).

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics and ENDS flavour/device used most often

| 2018, n=919 | 2020, n=689 | Overall, n=1608 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Respondent type | Replenishment | 646 | 70.3 | 366 | 53.1 | 1012 | 62.9 |

| Recontact | 273 | 29.7 | 323 | 46.9 | 596 | 37.1 | |

| Sex | Male | 446 | 48.5 | 362 | 52.5 | 808 | 50.2 |

| Female | 473 | 51.5 | 327 | 47.5 | 800 | 49.8 | |

| Age group | 18–24 years | 298 | 32.4 | 295 | 42.8 | 593 | 36.9 |

| 25–39 years | 183 | 19.9 | 137 | 19.9 | 320 | 19.9 | |

| 40–54 years | 168 | 18.3 | 100 | 14.5 | 268 | 16.7 | |

| 55 years or older | 270 | 29.4 | 157 | 22.8 | 427 | 26.6 | |

| Annual household income | Low (≤ $30 000) | 301 | 32.8 | 210 | 30.5 | 511 | 31.8 |

| Medium ($30 000 to <$60 000) | 262 | 28.5 | 187 | 27.1 | 449 | 27.9 | |

| High (≥ $60 000) | 350 | 38.1 | 288 | 41.8 | 638 | 39.7 | |

| Not stated | 6 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.6 | |

| Education | Low (≤high school) | 280 | 30.5 | 195 | 28.3 | 475 | 29.5 |

| Moderate (college/associate degree) | 430 | 46.8 | 307 | 44.6 | 737 | 45.8 | |

| High (≥bachelor’s degree) | 209 | 22.7 | 187 | 27.1 | 396 | 24.6 | |

| Smoking status | Daily smoker | 420 | 45.7 | 308 | 44.7 | 728 | 45.3 |

| Non-daily smoker | 184 | 20.0 | 160 | 23.2 | 344 | 21.4 | |

| Ex-smoker | 315 | 34.3 | 221 | 32.1 | 536 | 33.3 | |

| ENDS use/smoking status | Daily/daily smoker | 214 | 23.3 | 181 | 26.3 | 395 | 24.6 |

| Daily/non-daily smoker | 109 | 11.9 | 80 | 11.6 | 189 | 11.8 | |

| Daily/ex-smoker | 286 | 31.1 | 186 | 27.0 | 472 | 29.4 | |

| Weekly/daily smoker | 206 | 22.4 | 127 | 18.4 | 333 | 20.7 | |

| Weekly/non-daily smoker | 75 | 8.2 | 80 | 11.6 | 155 | 9.6 | |

| Weekly/ex-smoker | 29 | 3.2 | 35 | 5.1 | 64 | 4.0 | |

| Flavour/device used most often | |||||||

| Cartridge | Tobacco/unflavoured | 124 | 13.8 | 96 | 14.1 | 220 | 13.9 |

| Menthol/mint | 71 | 7.9 | 85 | 12.5 | 156 | 9.9 | |

| Fruit/other | 95 | 10.5 | 101 | 14.9 | 196 | 12.4 | |

| Tank | Tobacco/unflavoured | 117 | 13.0 | 59 | 8.7 | 176 | 11.1 |

| Menthol/mint | 72 | 8.0 | 40 | 5.9 | 112 | 7.1 | |

| Fruit/other | 329 | 36.5 | 183 | 27.0 | 512 | 32.4 | |

| Disposable | Tobacco/unflavoured | 40 | 4.4 | 42 | 6.2 | 82 | 5.2 |

| Non-tobacco flavours | 53 | 5.9 | 73 | 10.8 | 126 | 8.0 | |

Data are unweighted and unadjusted.

ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems.

Time-in-sample

The analyses controlled for time-in-sample, which refers to the number of survey waves the respondent completed.27

Statistical analyses

Unweighted descriptive statistics were used to describe both the cross-sectional and cohort samples. All other analyses were conducted on weighted data. In brief, a raking algorithm28 was used to calibrate the weights on smoking status, geographic region and demographic measures. This calibration for the USA used benchmarks from the 2018 National Health Interview Survey.29

Generalised estimating equations (GEEs) were used to fit multinomial or logistic regression models, which accounted for within-person correlation over time and the complex survey design.30 The predicted marginal standardisation method was used to generate estimates. Statistical significance and CIs were computed at the 95% confidence level. All analyses were conducted in SAS-Callable SUDAAN (V.11).31

Main analyses

Cross-sectional multinomial GEE regression analyses were conducted to estimate prevalence of flavours, devices and flavour–device combinations and tested whether these estimates differed between 2018 and 2020 (n=1608). The analyses adjusted for sex, age group, smoking status (daily, non-daily and ex-smoker) and time-in-sample.

Longitudinal multinomial regression models were conducted to examine transitions between flavour–device combinations among baseline (2018) respondents who were followed up in 2020 (n=356). Due to small sample sizes in some groups, flavour–device combinations were reduced to four groups: (1) tobacco/tobacco-menthol-mix/unflavoured (all devices); (2) menthol/mint (all devices); (3) fruit/other flavoured disposables/tanks; and (4) fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (covered under the enforcement priority). We also provided transition estimates for all respondents who used flavours/devices at baseline that were exempt from enforcement (groups 1–3). The models adjusted for sex, age group, baseline smoking status and time-in-sample.

Next, the transition analyses were stratified by smoking status. Because of difficulty in model convergence with the four-group categorisation, flavour–device combinations were collapsed into three groups: (1) tobacco/unflavoured/menthol/mint (all devices); (2) fruit/other-flavoured disposables/tanks; and (3) fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (covered under the enforcement priority).

The third set of analyses descriptively examined the location of last purchase of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges in 2018 and 2020. Cohort and replenishment samples were included (n=150).

Supplemental analyses

The supplemental analyses included a descriptive examination of changes in smoking and vaping. We were unable to conduct analytical tests due to very small sample sizes, particularly for those using fruit/other-flavoured cartridges.

First, an adjusted logistic regression model was used to estimate continued abstinence from smoking or relapse back to smoking in 2020 among baseline ENDS users who were ex-smokers in 2018 (n=160). Next, a multinomial regression analysis was used to estimate smoking and vaping status at follow-up among baseline dual users (n=200). The outcomes included: (1) remained a smoker and frequent ENDS user; (2) remained a smoker and reduced/quit vaping; (3) quit smoking and remained a frequent ENDS user; and (4) quit smoking and reduced/quit vaping. Outcomes 1 and 2 were combined to create an overall rate of continued smoking and outcomes 3 and 4 were combined to create an overall rate of having quit smoking.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline sample characteristics for respondents who participated in the 2018 and/or 2020 surveys, and online supplemental table 1 presents baseline cohort sample characteristics for those who participated in 2018 and were followed up in 2020.

tobaccocontrol-2022-057445supp001.pdf (154.9KB, pdf)

Prevalence of ENDS flavour and device type used most often

Between 2018 and the first 5 months of the 2020 policy, the prevalence of tobacco/unflavoured ENDS significantly decreased (33.1% to 26.0%, p=0.01) and fruit flavours increased (30.0% to 36.4%, p=0.03). There was no significant change for menthol/mint (16.3% to 19.5%, p=0.19) or other flavours (20.5% to 18.2%, p=0.36). The use of cartridges increased (29.1% to 39.6%, p=0.001) and tanks decreased (62.8% to 51.5%, p<0.001). There was no change in the use of disposables (8.1% to 8.9%, p=0.64) (see table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of flavour and device type used most often by adult ENDS users

| 2018 | 2020 | Difference between 2018 and 2020 | |

| Weighted % (n) | P value* | ||

| ENDS flavour used most often | |||

| Tobacco/unflavoured | 33.1 (281) | 26.0 (197) | 0.01 |

| Menthol/mint | 16.3 (159) | 19.5 (144) | 0.19 |

| Fruit | 30.0 (258) | 36.4 (205) | 0.03 |

| Other flavours | 20.5 (203) | 18.2 (133) | 0.36 |

| ENDS device used most often | |||

| Disposable | 8.1 (95) | 8.9 (118) | 0.64 |

| Cartridge (prefilled) | 29.1 (296) | 39.6 (285) | 0.0001 |

| Tank (refillable) | 62.8 (522) | 51.5 (285) | <0.0001 |

Data are weighted and adjusted for sex, age group, smoking status (daily, non-daily and ex-smoker) and time-in-sample. Data are from all 1608 frequent (≥weekly) ENDS users who participated in the 2018 and/or 2020 surveys.

ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems.

Changes in prevalence of ENDS flavour–device combinations used most often

Figure 1 presents the prevalence estimates of flavour/device combinations at each survey wave. In 2018 and 2020, fruit/other-flavoured tanks were most prevalent (2018: 38.7%, 2020: 33.6%) and disposables in tobacco (2018: 4.4%, 2020: 3.4%) and non-tobacco (2018: 4.0%, 2020: 5.5%) flavours were least prevalent. Between 2018 and 2020, there were significant increases in fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (7.9% to 12.4%, p=0.026) and menthol/mint-flavoured cartridges (7.1% to 13.0%, p<0.01), and decreases in tobacco-flavoured tanks (15.6% to 10.0%, p=0.002) and fruit/other-flavoured tanks (38.7% to 33.6%, p=0.038).

Figure 1.

Prevalence (weighted %) of current ENDS flavour–device combination used most often by adults in 2018 and in 2020 (n=1608). Data are weighted and adjusted for sex, age group, smoking status (daily, non-daily and ex-smoker) and time-in-sample. Data are for adult ENDS users who vape daily or weekly. Respondents who completed the 2018 and/or 2020 survey(s) were included (cohort and replenishment samples). Asterisks (*) indicates a significant change (p≤0.05) in prevalence between 2018 and 2020. †Flavour–device combination enforced under the 2020 federal policy. Non-tobacco flavours (menthol/mint and fruit/other) were combined for disposable devices due to small sample sizes.

Transitions between ENDS flavours/devices between 2018 and 2020

Table 3 presents the overall transitions between flavours/devices among all baseline respondents who were followed up in 2020 (n=356). Table 4 shows the transitions by smoking status. Similar to changes in prevalence estimates in figure 1, we found a slight increase in the use of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges among the cohort sample, where 8.9% of respondents used this combination in 2018 and 10.8% in 2020.

Table 3.

Transitions between flavours/devices used most often among 2018 frequent adult ENDS users who were followed up in 2020

| 2020 flavour and device | ||||||

| 2018 flavour and device | Tobacco: all devices | Menthol/mint: all devices | Fruit/other flavours: disposable/tank | Fruit/other flavours: cartridge | Reduced or quit vaping | Cumulative row % |

| Flavours/devices exempt from the enforcement priority | ||||||

| Tobacco: all devices (n=108) | 51.4 | 11.7 | 6.0 | 13.1 | 17.8 | 100.0 |

| Menthol/mint: all devices (n=76) | 11.2 | 50.3 | 10.8 | 3.0 | 24.6 | 100.0 |

| Fruit/other flavours: disposable/tank (n=139) | 2.3 | 5.7 | 61.8 | 2.9 | 27.3 | 100.0 |

| All flavours/devices exempt from the enforcement priority (n=323) | 21.0 | 15.2 | 35.1 | 6.2 | 22.6 | 100.0 |

| Fruit/other flavours: cartridge (n=33), covered under the enforcement priority | 24.3 | 16.6 | 13.7 | 29.0 | 16.4 | 100.0 |

N=356. Data are weighted and adjusted for: sex, age, time-in-sample and baseline smoking status (daily, non-daily and ex-smoker). Four smokers were missing ENDS flavour or device data at follow-up and were excluded. Light gray shading: respondents using a flavour/device exempt from the 2020 enforcement priority. Dark gray shading: respondents using a flavour/device not exempt from the 2020 enforcement priority. Bolded estimates: respondents who reported using the same ENDS flavour/device in 2018 and 2020.

ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems.

Table 4.

Transitions between flavours/devices used most often among 2018 frequent adult ENDS users who were followed up in 2020, by smoking status (n=356)

| 2018 Flavour and device | 2018 smoking status | 2020 flavour and device | ||||||||||

| Tobacco/menthol/mint (all devices) |

Non-tobacco/menthol flavours (disposables and tanks) | Fruit/other flavoured cartridge* | Reduced or quit vaping | Cumulative row % | Switched flavour/device† | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | % | ||

| Tobacco/menthol/mint: all devices | Dual users | 53 | 50.9 | 8 | 7.7 | 6 | 10.9 | 42 | 30.5 | 109 | 100.0 | 18.6 |

| Ex-smokers | 57 | 75.8 | 4 | 6.6 | 1 | 7.6 | 13 | 10.1 | 75 | 100.0 | 14.2 | |

| Fruit/other flavours: disposables and tanks | Dual users | 5 | 5.6 | 29 | 49.0 | 4 | 2.9 | 29 | 42.5 | 67 | 100.0 | 8.5 |

| Ex-smokers | 6 | 9.8 | 54 | 74.1 | 3 | 3.1 | 9 | 13.1 | 72 | 100.0 | 12.9 | |

| Fruit/other flavour: cartridges* | Dual users | 7 | 46.0 | 4 | 11.2 | 2 | 11.7 | 9 | 31.1 | 22 | 100.0 | 57.2 |

| Ex-smokers | 3 | 36.4 | 2 | 15.2 | 6 | 48.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 100.0 | 51.6 | |

Data are weighted and adjusted for sex, age, time-in-sample and baseline smoking status (daily, non-daily and ex-smoker). Four smokers were missing ENDS flavour or device data at follow-up and were excluded.

*Flavour–device combination enforced under the 2020 federal policy. Light grey shading: respondents using a flavour/device exempt from the 2020 enforcement priority. Dark grey shading: respondents using a flavour/device not exempt from the 2020 enforcement priority.

†Respondents who continued to vape but switched to another flavour/device between 2018 and 2020. Bolded estimates: those who continued to use the same ENDS flavour/device. Due to small sample sizes, data should be interpreted with caution.

ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems.

With regard to continued use or switching between flavours/devices, the highest proportion of continued use was for fruit/other-flavoured tanks (61.8%), followed by tobacco (any device) (51.4%), menthol/mint (any device) (50.3%) and fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (29.0%). Overall, 54.6% of baseline fruit/other-flavoured cartridge users switched to a flavour/device excluded from the enforcement priority: 24.3% switched to tobacco flavoured cartridges, 16.6% switched to menthol/mint-flavoured cartridges and 13.7% switched to fruit/other-flavoured disposable or tank devices. By contrast, 6.2% of baseline respondents who used any flavour/device exempt from enforcement switched to fruit/other-flavoured cartridges covered under the enforcement priority.

The highest rate of reducing/stopping ENDS use was among baseline users of fruit/other-flavoured disposables/tanks (27.3%), followed by menthol/mint (any device) (24.6%), tobacco (any device) (17.8%) and fruit/other-flavoured cartridges (16.4%).

There were differences by smoking status (see table 4), where a higher proportion of ex-smokers continued to use fruit/other cartridges (48.5%) relative to dual users (11.7%). A higher proportion of dual users switched to tobacco or menthol/mint devices (46.0%) relative to ex-smokers (36.4%). There was little difference in switching to fruit/other-flavoured disposables and tanks (11.7% vs 15.2%, respectively).

Location of last purchase of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges

In 2020, more fruit/other-flavoured cartridge ENDS users purchased online (38.2%) than in 2018 (25.0%), and fewer purchased from retail outlets, with the exception of vape shops (rates did not change). Data are presented in table 5.

Table 5.

Location of last purchase among frequent adult ENDS users using fruit/other-flavoured cartridges in 2018 and 2020

| Location of purchase | 2018 (n=66) | 2020 (n=84) |

| Weighted % (95% CI) | ||

| Internet | 25.0 (12.7 to 43.3) | 38.2 (2.8 to 56.4) |

| Vape shop | 22.5 (11.5 to 39.5) | 23.4 (12.1 to 40.4) |

| Other retail location | 42.7 (27.2 to 59.7) | 25.7 (13.4 to 43.5) |

| Somewhere else/don’t know | 9.9 (3.4 to 25.6) | 12.7 (4.0 to 33.5) |

Data are weighted and adjusted for sex, age group, smoking status (daily, non-daily and ex-smoker) and time-in-sample. Other retail locations included: tobacco specialty shop, gas station, supermarket and convenience store. Somewhere else included: temporary or mobile sales location, outside the country and don’t know/remember. Statistical comparisons were not made due to low sample sizes.

ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems.

Supplemental analyses

Changes in smoking and vaping among ex-smokers are presented in online supplemental table 2 and among dual users in online supplemental table 3.

In brief, 90.2% of all ex-smokers remained abstinent from smoking in 2020. Among those who were using fruit/other-flavoured cartridges at baseline, 95.2% remained abstinent from smoking, and 4.8% reported having returned to smoking.

Among all dual users, 77.5% continued smoking in 2020. Among those who were using fruit/other-flavoured cartridges at baseline, 78.5% continued to smoke and 21.6% quit smoking (14.9% quit smoking and remained frequent ENDS users and 7.6% quit smoking and reduced or stopped ENDS use).

Discussion

In January 2020, the FDA announced that it would prioritise enforcement efforts against ENDS flavoured prefilled cartridges/pods, with the exception of tobacco and menthol flavours. The enforcement priority came into effect in February 2020. This pre–post evaluation study examined changes between pre-enforcement (2018) and early postenforcement (the first 5 months, February–June) among adult current and ex-smokers on their usual ENDS flavour and device type and transitions between flavours/devices before and after the 2020 policy shift. Overall, we found that between 2018 and the early phase of the 2020 enforcement priority, there was an increase in the prevalence of usual use of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges among adult frequent ENDS users; however, half of adults who were using fruit/other flavoured ENDS cartridges at baseline switched to flavours and/or devices exempt from enforcement. There were few changes in smoking and vaping behaviours between surveys. Nearly all ex-smokers remained quit (90%), and among dual users, 78% continued to smoke (of those, 52% also continued to vape at least weekly).

Some US studies have examined changes in ENDS use and/or smoking and vaping behaviours among youth and/or adults after implementing laws restricting flavoured ENDS, with some finding similar results to ours.12 32–38 For example, our study found that prevalence of usual use of fruit flavours had increased between 2018 and the first 5 months postenforcement, while tobacco flavours decreased, but the use of menthol/mint and other non-tobacco flavours did not change. We also found an increase in the prevalence of the flavour–device combination that was covered in the 2020 enforcement priority (eg, fruit/other-flavoured cartridges). In contrast to our findings, Yang et al 32 found a decrease in the prevalence of all non-tobacco flavoured ENDS after they were banned in San Francisco, but similar to our findings, many young adults continued to use restricted flavours (39% of those aged 18–24 years and 27% of those aged 25–34 years), there was no change in menthol-flavoured ENDS, and use of tobacco-flavoured ENDS decreased (but only among younger respondents). A study by Ali et al 33 found that statewide restrictions on non-tobacco ENDS flavours (in Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island and Washington) were associated with a reduction of 25%–31% in total ENDS sales compared with states without restrictions, which was attributed primarily to decreases in non-tobacco-flavoured ENDS sales. In contrast, a recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that following the FDA’s flavour 2020 enforcement priority, total ENDS sales in the US increased by 46.3%.38 Non-tobacco flavoured ENDS accounted for 73.7% of the US ENDS market. There was also an increase in disposable ENDS sales in 2020. Our data did not show that adults increased their use of disposables (and indicated that few use them), suggesting that youth (and possibly never-smokers) accounted for the greatest increase in the market share of disposables. The CDC also found that the market share of menthol-flavoured cartridges increased in 2020. Our data also showed an increase in this flavour–device combination, suggesting that some ENDS users who prefer prefilled cartridges shifted their flavour rather than their device. Also in contrast to our study, the CDC reported that total sales of cartridges decreased, whereas we found an increase in the use of cartridges. These differences likely reflect that national US sales data do not include vape shops or online retailers. Since many ENDS users purchased from these sources, Nielsen sales estimates, very likely underestimate the ENDS product market. Finally, a recent study by Hammond et al that examined the impact of the 2020 enforcement policy on adolescents (ages 16–19 years) found that usual flavours used by youth in the USA were unchanged before versus after 2020, and 78% of youth in the USA reported using a flavour prohibited in cartridges after the policy was implemented.12 However, the authors also noted that ‘youth vapers in the US appear to have circumvented the flavor restrictions by using device types exempt from the restrictions, illustrated in the rapid rise of disposable e-cigarette brands’.

The continued use of flavoured cartridges targeted by FDA’s enforcement efforts appears to demonstrate that these products were still widely available at the time of our survey. For example, we found an increase in online purchasing of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges. Yang et al 32 also found that internet purchases of restricted flavours increased, from 16% to 27%, after the non-tobacco flavour ban in San Francisco. As sales restrictions remain largely unenforced on the internet, it is no surprise that many ENDS users who use restricted products shifted to online purchases. In contrast, we found a decrease in purchasing restricted flavoured cartridges from retail locations other than vape shops, such as convenience stores and gas stations. The lack of change in vape shop purchases of ENDS covered under the 2020 enforcement may suggest non-compliance during the early phase of the enforcement priority change.

With regard to transitions between flavours and devices, our data showed that the most pronounced transitions occurred among those who were using fruit or other flavoured cartridges that were covered in the enforcement priority. About half of respondents who were using fruit/other flavour cartridges in 2018 switched to another flavour and/or device that was excluded from the enforcement priority, whereas respondents using other flavour–device combinations were more stable between surveys. There were also some marked differences in transitions between flavours/devices by smoking status. For example, relative to baseline dual users, ex-smokers had higher rates of continued use of their baseline flavour, and dual users had higher rates of reducing or quitting ENDS use by follow-up. Among ex-smokers who were using fruit/other-flavoured cartridges in 2018, half reported continued using of this combination in 2020, whereas one-tenth of dual users continued using fruit/other-flavoured cartridges. This may suggest that dual users are less stable in their flavour–device choices and more willing to switch flavours, where ex-smokers who have switched to vaping are not.

Implications for tobacco regulatory policy

Our postevaluation data were collected in the early phase of the 2020 enforcement policy, thus the timing may have implications for our early observations. For example, some respondents may have stockpiled their flavoured cartridges prior to the enforcement. It is also likely that this type of policy change may take a significant amount of time to actually enforce the removal of ENDS products from the US market. However, even in the early phase of the enforcement priority, we found a large shift from restricted ENDS to other flavours and/or devices exempt from enforcement, which similarly has been found among youth.10 12 The extent to which more comprehensive restrictions would be more effective for youth, or possibly problematic for adults, remains uncertain. Notably, because disposables are used by few adults (<10% in this study), but are used by many youth (37% in August 2020),12 implementing and enforcing flavour restrictions for disposables may be the kind of policy approach that could help reduce ENDS use among youth without affecting adults.

At this early stage of the enforcement priority, the ways ENDS users may have responded to FDA’s enforcement efforts are unclear. It could be that ENDS users would be affected through two mechanisms of the enforcement priority. First, ENDS users of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges could be directly impacted through changes in the availability of products, and/or second, they could have been indirectly impacted through communication by the FDA and/or media coverage that this enforcement priority would more strictly regulate specific flavoured cartridges. Notably, since October 2021, the FDA has authorised the sale of 15 tobacco-flavoured tank and cartridge ENDS.39 No other ENDS products have received approval through the Premarket Tobacco Product Application pathway. Studies are needed to examine whether the FDA’s further regulatory actions will have an impact on smoking and vaping behaviours among both youth and adults.

Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. First, this study included frequent (at least weekly) adult ENDS users, and thus, changes in ENDS flavours and devices used by less frequent users and/or those experimenting with vaping are unknown. As well, this study is only generalisable to adult current and former smokers. In order to estimate population-level changes, data on both youth and adults, smokers and non-smokers should be considered. Second, our data were collected in the early phase of the enforcement policy. ENDS use at the time of this study may look very different across time. Third, there were other major changes in the ENDS market after 2018, but prior to the 2020 policy that could have contributed to changes in ENDS flavour/devices. For example, JUUL, the most popular ENDS brand in the USA halted sales of all cartridge flavours in 2019, with the exception of tobacco and menthol.40 Some JUUL users may have already switched flavours and/or devices prior to 2020. Fourth, sample sizes were small for cohort respondents; thus, we could not assess statistical differences in changes in smoking and vaping behaviours. Estimates should be interpreted with caution. Fifth, ‘mint’ flavour was not exempt from the 2020 policy; however, in our survey, we asked respondents if they used menthol or mint, so it is uncertain which specific flavour respondents were using. Finally, our survey was conducted during the early phase of the pandemic, so the increase in online sales may have also been related to stay-at-home orders that were in place to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.41

Conclusions

Between 2018 and the early phase following the FDA’s 2020 ENDS enforcement priority, prevalence of fruit/other-flavoured cartridges increased among adults. The most pronounced transitions between flavours/devices occurred among adults who were using ENDS products targeted by the enforcement priority, where half switched to flavours and/or devices that were exempt. However, unlike youth, there was no significant increase in the prevalence or shift to disposable devices. The extent to which more comprehensive restrictions would be more effective for limiting youth use, or possibly problematic for adults who vape as a method of quitting smoking or to remain abstinent from smoking, remains uncertain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all those who contributed to the International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey (ITC 4CV) Survey: all study investigators and collaborators, and the project staff at their respective institutions.

Footnotes

Twitter: @gfong570

Contributors: Conceptualisation: KAK, SG, GM and DH; methodology: KAK, SG, GM, DH and GTF; validation: GM and SG; formal analysis: GM; investigation: SG, GM, KAK, DH, AH, KMC and GTF; writing—original draft preparation: SG; writing—review and editing: all authors; supervision: GTF, KMC, AH and DH; funding acquisition: KMC, GTF, and KAK; SG, GM, and KAK accept full responsibility for the finished work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. All authors contributed to data interpretation, participated in manuscript revisions, and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The ITC 4CV study is supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute (P01 CA200512), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148477) and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP 1106451). Additional support to GTF was provided by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and the Canadian Cancer Society O. Harold Warwick Prize. Additional support to AH was provided by a Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science US National Cancer Institute grant (U54CA238110). Funding for this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health and FDA Center for Tobacco Products under Award Number R21DA053614.

Disclaimer: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the FDA Center for Tobacco Products.

Competing interests: KMC has served as paid expert witness in litigation filed against cigarette manufacturers. GTF and DH have served as expert witnesses or consultants on behalf of governments defending their country’s policies or regulations in litigation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. In each country participating in the international Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project, the data are jointly owned by the lead researcher(s) in that country and the ITC Project at the University of Waterloo. Data from the ITC Project are available to approved researchers 2 years after the date of issuance of cleaned data sets by the ITC Data Management Centre. Researchers interested in using ITC data are required to apply for approval by submitting an International Tobacco Control Data Repository (ITCDR) request application and subsequently to sign an ITCDR Data Usage Agreement. The criteria for data usage approval and the contents of the Data Usage Agreement are described online (http://www.itcproject.org).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Study questionnaires and materials were reviewed and provided clearance by Research Ethics Committees at the following institutions: University of Waterloo (Canada, REB#20803/30570, REB#21609/30878), Cancer Council Victoria, Australia (HREC1603) and the Medical University of South Carolina (waived due to minimal risk). All participants provided consent to participate. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Stastitica . University of Waterloo. e-cigarettes. Available: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/tobacco-products/e-cigarettes/worldwide

- 2. Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. E-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA 2019;322:2095–103. 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Uddin SMI, et al. Trends in e-cigarette use in adults in the United States, 2016-2018. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1394–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dai H, Leventhal AM. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA 2019;322:1824–7. 10.1001/jama.2019.15331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ranjit A, McCutchan G, Brain K, et al. "That's the whole thing about vaping, it's custom tasty goodness": a meta-ethnography of young adults' perceptions and experiences of e-cigarette use. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2021;16:85. 10.1186/s13011-021-00416-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhu S-H, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control 2014;23 Suppl 3:iii3–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zare S, Nemati M, Zheng Y. A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: flavor, nicotine strength, and type. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194145. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Landry RL, Groom AL, Vu T-HT, et al. The role of flavors in vaping initiation and satisfaction among U.S. adults. Addict Behav 2019;99:106077. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Creamer MR, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ 2019;68:1–22. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6812a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, et al. E-cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1310–2. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Simpson KA, et al. A review of the use and appeal of flavored electronic cigarettes. Curr Addict Rep 2019;6:98–113. 10.1007/s40429-019-00244-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hammond D, Reid J, Burkhalter R. E-Cigarette flavors, devices and brands used by youth before and after partial flavor restrictions in the US: findings from the ITC youth tobacco and Vaping surveys in Canada, England, and the US, 2017-2020. Am J Public Health. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . FDA takes new steps to address epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, including a historic action against more than 1,300 retailers and 5 major manufacturers for their roles perpetuating youth access, 2018. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-new-steps-address-epidemic-youth-e-cigarette-use-including-historic-action-against-more

- 14. Russell C, McKeganey N, Dickson T, et al. Changing patterns of first e-cigarette flavor used and current flavors used by 20,836 adult frequent e-cigarette users in the USA. Harm Reduct J 2018;15:33. 10.1186/s12954-018-0238-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gravely S, Cummings KM, Hammond D, et al. The association of e-cigarette flavors with satisfaction, enjoyment, and trying to quit or stay abstinent from smoking among regular adult Vapers from Canada and the United States: findings from the 2018 ITC four country smoking and Vaping survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:1831–41. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schneller LM, Bansal-Travers M, Goniewicz ML, et al. Use of flavored e-cigarettes and the type of e-cigarette devices used among adults and youth in the US—Results from wave 3 of the population assessment of tobacco and health study (2015–2016). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2991. 10.3390/ijerph16162991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Du P, Bascom R, Fan T, et al. Changes in flavor preference in a cohort of long-term electronic cigarette users. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;17:573–81. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201906-472OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kasza KA, Goniewicz ML, Edwards KC, et al. E-Cigarette flavors and frequency of e-cigarette use among adult dual users who attempt to quit cigarette smoking in the United States: longitudinal findings from the PATH study 2015/16-2016/17. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:4373. 10.3390/ijerph18084373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rest EC, Brikmanis KN, Mermelstein RJ. Preferred flavors and tobacco use patterns in adult dual users of cigarettes and ends. Addict Behav 2022;125:107168. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA permits marketing of e-cigarette products, marking first authorization of its kind by the agency, 2021. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-marketing-e-cigarette-products-marking-first-authorization-its-kind-agency

- 21. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint, 2020. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- 22. Thompson ME, Fong GT, Boudreau C, et al. Methods of the ITC four country smoking and Vaping survey, wave 1 (2016). Addiction 2019;114 Suppl 1:6–14. 10.1111/add.14528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ITC Project . ITC four country smoking and Vaping survey, wave 2 (2018) technical report. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, United States; Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the University of Queensland, Australia; King’s College London, London, United Kingdom, 2020. https://itcproject.org/methods/technical-reports/itc-four-country-smoking-and-vaping-survey-wave-2-4cv2-technical-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 24. ITC Project . ITC four country smoking and Vaping survey, wave 3 (4CV3, 2020) technical report. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, United States; Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the University of Queensland, Australia; King’s College London, London, United Kingdom, 2021. https://itcproject.org/methods/technical-reports/july-23-2021-itc-4cv-wave-3-2020-technical-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 25. ITC Project . 4CV3-US. Available: https://itcproject.org/surveys/united-states-america/4c3-us/

- 26. ITC Project . 4CV2-US. Available: https://itcproject.org/surveys/united-states-america/4cv2-us/

- 27. Thompson ME. Using longitudinal complex survey data. Annu Rev Stat Appl 2015;2:305–20. 10.1146/annurev-statistics-010814-020403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolenikov S. Calibrating survey data using iterative proportional fitting (Raking). Stata J 2014;14:22–59. 10.1177/1536867X1401400104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . National Center for Health Statistics. National health interview survey (NHIS). Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm

- 30. Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:962–70. 10.1093/ije/dyu029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. RTI International . SUDAAN® statistical software for analyzing correlated data. Available: https://www.rti.org/impact/sudaan-statistical-software-analyzing-correlated-data

- 32. Yang Y, Lindblom EN, Salloum RG, et al. The impact of a comprehensive tobacco product flavor ban in San Francisco among young adults. Addict Behav Rep 2020;11:100273. 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ali FRM, Vallone D, Seaman EL, et al. Evaluation of statewide restrictions on flavored e-cigarette sales in the US from 2014 to 2020. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2147813. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Katchmar A, Gunawan A, Siegel M. Effect of Massachusetts house bill No. 4196 on electronic cigarette use: a mixed-methods study. Harm Reduct J 2021;18:50. 10.1186/s12954-021-00498-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedman AS. A Difference-in-Differences analysis of youth smoking and a ban on sales of flavored tobacco products in San Francisco, California. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:863–5. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hawkins SS, Kruzik C, O'Brien M, et al. Flavoured tobacco product restrictions in Massachusetts associated with reductions in adolescent cigarette and e-cigarette use. Tob Control 2022;31:576–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rogers T, Brown EM, Siegel-Reamer L, et al. A comprehensive qualitative review of studies evaluating the impact of local US laws restricting the sale of flavored and menthol tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res 2022;24:433–43. 10.1093/ntr/ntab188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Monitoring U.S. e-cigarette sales: national trends, 2021. Available: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/National-E-CigaretteSales-DataBrief-2021-Mar21?inline

- 39. FDA. Available: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/premarket-tobacco-product-applications/premarket-tobacco-product-marketing-granted-orders

- 40. CNN News . Juul to stop selling several flavored products in the United States, 2019. Available: https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/17/health/juul-stop-selling-flavor-bn/index.html

- 41. Moreland A, Herlihy C, Tynan MA, et al. Timing of State and Territorial COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Orders and Changes in Population Movement - United States, March 1-May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1198–203. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tobaccocontrol-2022-057445supp001.pdf (154.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. In each country participating in the international Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project, the data are jointly owned by the lead researcher(s) in that country and the ITC Project at the University of Waterloo. Data from the ITC Project are available to approved researchers 2 years after the date of issuance of cleaned data sets by the ITC Data Management Centre. Researchers interested in using ITC data are required to apply for approval by submitting an International Tobacco Control Data Repository (ITCDR) request application and subsequently to sign an ITCDR Data Usage Agreement. The criteria for data usage approval and the contents of the Data Usage Agreement are described online (http://www.itcproject.org).