Abstract

Past researches have found that sense of control and meaning in life can act as a protective factor against fear of COVID-19 pandemic. The current study examined whether the search for meaning and the presence of meaning could mediate the link between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. A total of 312 Iranians who were identified by snowball sampling were recruited as the subjects of the cross-sectional study. The participants gave their consent to complete the Meaning in Life Scale, Flourishing Scale, and Fear of COVID-19 Scale. The findings demonstrated that fear of COVID-19 had a significant direct effect on flourishing. The presence meaning was positively and significantly connected with flourishing and the search for meaning. Both the search for - and the presence - of meaning were negatively and significantly linked with fear of COVID-19. Mediation analysis demonstrated that a presence of meaning is a protective factor for flourishing, but the search for meaning can be detrimental to flourishing. As a result, it may be worthwhile to conduct longitudinal research to track how the effects of the presence of meaning and the search for meaning vary over time. The study calls on mental health providers to take into account how the presence of meaning might lessen the negative impacts of fear in crisis situations and promote flourishing.

Keywords: Fear of COVID-19, Flourishing, Iran, Meaning in life, Presence of meaning, Search for meaning

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people of all ages have continued to live in a state of uncertainty, fear, and worry as a result of the contagious COVID-19 disease and its variants. However, while being confronted with the pandemic crisis, some people were able to change their viewpoint on life or begin to perceive their daily lives, desires, and goals from a new perspectives. The rise of digital behavior such as working-from-home, learning through virtual systems, e-business and, health delivery services related trends could be among the indicators of the changes in people’s beliefs and behaviors during the pandemic outbreak. Thus, despite the unpredictable effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible that people could find ways amid the sufferings and learn how to transform emotionally overwhelming experiences into learning opportunities.

Adaptability to uncertainty and learning to live a more cautious life have become more familiar than the pre-pandemic periods. However, studies tend to focus on the adverse consequences of the COVID-19 on the psychological functioning of the public (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Arpaci et al., 2020) and little is paid attention to the inherent potential of individuals to thrive despite the adversities. In every individual, there is an inherent potential to thrive, not just survive the adversities (Seligman, 2011). By taking control of how they perceive adversity and develop resilience, individuals may be inspired to engage in sense-making even in the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, not everyone has the ability to develop their best selves, endure adversity, and overcome challenges. Some may react to the COVID-19 threat by comprehending the circumstance and acknowledging the loss, while others may continue to be uneasy and worried about the pandemic. By choosing to view and frame uncertainties more meaningfully, other folks may model voluntarism and engage in prosocial activities. While some might look for new meaning and opportunities for growth, others might decide to use spirituality to cope with uncertainty. Individuals who have a clear sense of purpose in life will be better able to make sense of a crisis and deal with adversity (Halama, 2014; Schaefer et al., 2013). In the absence of a clear sense of direction and purpose in life, individuals have to search for meaning.

The process to search for meaning requires individuals to have a deeper understanding of themselves, the world, and a continued effort towards making sense of ongoing experiences (Park et al., 2010). However, during the pandemic, propensities to often pose “what if” scenarios in the lack of definitive responses may heighten anxieties. Worrying more about the future could impair the capacity for reasoned thought, and individuals may engage less in logical behaviors and use coping resources less efficiently (Elemo et al., 2020). In spite of this, individuals do possess an adaptive potential and they can choose to change their psychological responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, it is likely to ask “what motivates individuals to thrive consistently and remain resilient against the adversities during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Even in the face of a crisis situation, individuals can choose how to respond. Beyond the emotional burden of the COVID-19 crisis, individuals can regulate their psychological responses and possess better mental health given that thay have clear sense of purpose and meaning in life (Arslan et al., 2022). The drive to find meaning in life gives hope and personal agency needed to maintain a resilient life (Frankl, 1985). In spite of the hardships, individuals can adopt a positive attitude towards the situation and take part in prosocial activities. It is possible to experience well-being even without positive affect and active participation through meaning, virtue, and spirituality. Thus, despite the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, examining how individuals tend to adopt a healthy mindset and engage in prosocial behavior may support the public in comprehending and overcoming the short- and long-term effects of the COVID-19.

Fear of COVID-19 and Flourishing

A situation of tremendous fear, anxiety, and uncertainty has also been created by the daily rising cases and deaths of COVID-19, which posed a serious threat to the physical health of the world’s population. Fear is necessary for humans because it serves as an adaptive defensive system for survival by inducing reactions to potentially threatening events. However, extreme fear can increase anxiety and stress even in healthy individuals, generating short to long-term psychological repercussions (Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Managing fear and anxiety demands adopting healthy physical and mental lifestyles to reinforce the well-being levels of individuals. Thus, despite the increased fear and uncertainty surrounding the life-threatening COVID-19, emerging studies are exploring how people have buffered such stressful events via self-control and meaning in life (Elemo et al., 2021; Humphrey & Vari, 2021; Schnell & Krampe, 2020). Overall, the studies show that despite the COVID-19 threats, people may adapt to the outbreak and flourish.

Individuals can continue to strive and help to foster their tendency to flourish through different ways, despite the sufferings in the pandemic. Some people could decide to improve their relationships in order to thrive, while others would decide to volunteer and help others as a potent means of improving their health. Seligman (2011) has also made reference to his PERMA model, which stands for positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment, in order to address the central issues of what constitutes and promotes human flourishing. Thus, the sufferings in the midst of the COVID-19 may not necessarily be the opposite of flourishing, and a person can thrive through good times and life struggles. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the link between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing, and determine underlying factors that may enhance better participation in daily activities and improve well-being.

Presence of meaning and search for meaning as mediators

Meaning in life is ‘‘the cognizance of order, coherence, and purpose in one’s existence, the pursuit, and attainment of worthwhile goals, and an accompanying sense of fulfillment’’ (Reker & Wong, 1988, p. 221). Individuals tend to inquire into searching for and achieving meaning in life as a way of understanding life events and bringing them into a coherent whole. They can obtain perspectives on current events, draw lessons and strengths from past experiences, and chart a course for a worthwhile future (Wong, 2011). Love, success, and unavoidable sufferings are just a few of the important factors that make up the subjective notion of what life is all about (Frankl, 1985). When confronted with traumatic situations, individuals may change their beliefs about what provides meaning in life. If meaning is not gained, individuals can make up for it by seeking meaning (Markman et al., 2013). In light of this, meaning in life is an essential psychological resource that promotes greater human functioning.

While there is some variation among the various understandings of how meaning is achieved, there is consensus that meaning in life is a fundamental concern of human life (Reker & Chamberlain, 2000). For instance, Australians and Canadians associate sources of meaning in life with participation in personal relationships and leisure activities, personal growth, and meeting basic needs (Prager, 1996). However, for the Chinese, culturally specific factors are important and people seek meaning in their relations to others (e.g., family, society), and through self-development, being close to nature and authenticity (Lin, 2001). Individuals feel a greater presence of meaning given that they have better awareness of themselves, an understanding of their environment and adapt to the world (Steger et al., 2008). This could be related to the number of functions meaning in life serves in individuals’ lives, which includes providing purpose, furnishing values or standards by which to judge actions, giving a sense of control over the events in life, and providing self-worth (Frankl, 1985).

Meaning in life can be analyzed from two dimensions: the quest for meaning in life and the presence of meaning in life (Park et al., 2010). The search for meaning refers to the idea that individuals are strongly motivated to find meaning in their lives, while the presence of meaning is the sense of having clear direction in life. Having a clear sense of meaning in life can serve as a protective factor that facilitates adaptations in a variety of adverse situations (Brassai et al., 2011; Lew et al., 2020; Steger et al., 2008). When people are unable to find meaning or when they lose the meanings that they once had, they would be more likely to become distressed.

When things are going well, positive emotions might serve to build enduring personal resources (physical, intellectual resources, social and psychological resources) and maintain a high level of wellbeing (Fredrickson, 2001). However, meaning rather than positive emotions becomes more crucial in maintaining some well-being when people go through challenging life events (Wong, 2011). It is undeniable that the COVID-19 pandemic has threatened participants’ core meaning sources (Ekwoyne et al., 2021). However, studies show that having a sense of purpose in life is one of the factors that is associated with life satisfaction during the COVID-19 (Karataş et al., 2021), improved wellbeing and resilience (Fry, 2000), and decreased psychological distress (e.g., Arslan et al., 2022; Chao et al., 2020; Milman et al., 2020). Therefore, despite the COVID-19 vulnerabilities, people can find meaning in their lives and cope with the pandemic’s discomforts more successfully.

When the two dimensions of the meaning in life were separately considered, it was the presence of meaning that was associated with positive mental health outcomes (Linley & Joseph, 2011; Steger et al., 2015), while the search for meaning (actual or prolonged) was associated with negative outcomes (Newman et al., 2022; Park et al., 2010). Therefore, even if there is a great deal of worry and fear related to the COVID-19 threats, having meaning in life may encourage people to concentrate on the improvements people can make rather than dwelling on the losses they suffered as a result of the COVID-19.

The Present Study

In Iran (at the time of writing, September 30, 2021), there had been over 120,000 COVID-19 deaths and over 5.6 million confirmed cases (Worldometer, 2021). In terms of total cases, Iran is ranked eighth among all countries (Worldometer, 2021). As the fifth wave peaks with a sharp spike of the Delta variant of the COVID-19 infection, the number of cities marked “high risk” have increased (Mehdi, 2021) suggesting an increase in physical and psychological problems. Though fear is important to initiate and maintain virus-mitigating behavioral changes, the present study specifically highlights if the presence of meaning or the search for meaning in life can help to reduce the fear of COVID-19 and buffer tendencies of flourishing in individuals. Existing studies indicate that meaning in life and self-control can serve as protective factors against the consequences of fear of COVID-19 (Schnell & Krampe, 2020). However, when examined in terms of its two dimensions of meaning in life, have varying effects on the fear of COVID-19. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the relationship between the presence of meaning and the pursuit of meaning in relation to people’s wellbeing during the coronavirus pandemic. Thus, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1

Fear of COVID-19 will be negatively associated with flourishing.

H2

The association between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing will be mediated by search for meaning and presence of meaning.

Method

Study design and participants

This study used a cross-sectional online survey to examine the association between fear of COVID-19, meaning in life, and flourishing in an Iranian sample. Snowball sampling was used to include a total of 312 individuals in the study. Selection criteria included access to the Internet connection, giving informed consent, being at least 18 years old, and being Iranian. The participants responded to an online survey that asked about their levels of fear of COVID-19, meaning in life, and flourishing. The online survey was prepared using the Google Form and distributed via WhatsApp and Facebook over a month during the post-lockdown (between December 15, 2020 and January 30, 2021). Participants were encouraged to invite their family and friends to participate. All information was kept confidential, participation was voluntarily, anonymous, and confidential, and the return of completed forms signified informed consent. In the Google Form it was made clear to participants that the participants might leave the study whenever they wanted.

The University Ethical Review Board gave the study approval. The 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its following revisions, or equivalent ethical norms, were followed during the study’s procedures. The participants ages ranged from 18 to 78 years and the mean age of the participants was 28.19 years (SD = 10.09) and only 30.13% were females. One out of the four participants were married. Detailed information about the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (N = 312)

| Demographics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 218 | 69.87 |

| Female | 94 | 30.13 | |

| Relationship status | Single | 219 | 70.19 |

| Married | 81 | 25.96 | |

| Widow | 12 | 3.85 | |

| Know a family member or a friend infected with COVID-19 | Yes | 183 | 58.65 |

| No | 129 | 41.35 | |

| Hospitalised due to COVID-19 | Yes | 50 | 16.03 |

| No | 262 | 83.97 | |

Measures

This survey consisted of three measures: Fear of COVID-19 Scale, Flourishing Scale, and Meaning in Life Questionnaire.

Fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19 S)

The FCV-19 S is a unidimensional scale that assesses the fear of COVID-19 and was developed by Ahorsu et al. (2020). The instrument comprises seven items (e.g., “My heart races when I think about getting coronavirus-19”) which are responded to on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scores that can be obtained from the FCVS-19 vary between 7 and 35, and higher scores indicate greater fear of COVID-19. The internal consistency of the FCV-19 S in the current study was 0.87.

Flourishing scale (FS)

The FS is a unidimensional scale that includes eight items that describe important aspects of human functioning, ranging from positive relationships to feelings of competence, to having meaning and purpose in life (Diener et al., 2009). Each item of the FS is answered on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Examples of the items include “I am engaged and interested in my daily activities”. All the items are phrased in a positive direction. The scores obtained range between 8 and 56, and higher scores signify that respondents view themselves in positive terms in important areas of functioning. The internal consistency of the FS in the current study was.96.

Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ)

The MLQ has 10 items that assess the degree to which participants felt their life was meaningful (Steger et al, 2006). It consists of two dimensions: the search for meaning in life and the presence of meaning in life. Items in the presence of meaning dimension (e.g., “I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful”) measure how many respondents feel their lives have meaning. Items in the search for meaning dimension (e.g., “I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful”) measures how much respondents strive to find meaning and understanding in their lives. Each item of the MLQ is answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Absolutely True) to 7 (Absolutely Untrue). The internal consistency of the MLQ in the current study was.92. The internal consistency of the sub-scales: the presence of meaning, and the search for meaning were .84 and .93, respectively.

Demographic questionnaire

This was prepared by researchers and included questions about the participants’ gender, age, region, and their knowledge of someone infected by the virus.

Data Analysis

This study aimed to examine whether the search for meaning and presence of meaning mediate the relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and flourishing in the Iranian sample population. By doing a bivariate correlational analysis with a correlation coefficient below 0.80 to rule out multicollinearity, we could proceed with the analysis assuming relative independence among the variables (Belsley, 1982). Since none of the Mahalanobis values exceeded 15, there was no sign of a problem. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used in this study. In this study, fear of COVID-19, flourishing, presence of meaning, and search for meaning were regarded as latent variables.

In order to evaluate goodness-of-fits of the data to the model, standard criteria were utilized. Accordingly, Tucker-Lewis’s Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) above 0.90; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) below 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.09 (MacCallum et al., 1996) were evaluated. Bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs) of the indirect effects was performed to examine whether search for meaning and presence of meaning mediate the relation between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. Analysis includes age as a covariate variable. The IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and IBM AMOS 24 software packages were utilized for all analyses.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables, as well as their inter correlations. A positive association between flourishing and presence of meaning in life (r = .13, p < .05) was identified. The same pattern was found in the relation between the two sub-dimensions of meaning in life (r = .79, P < .01). Fear of COVID-19 was negatively related to negatively associated with presence of meaning (r = − .22, p < .001) and Search for meaning (r = − .28, p < .001). The values of skewness ranged from − 0.13 to − 1.19 and kurtosis ranged from − 0.43 to 0.82, indicating that they are within the acceptable range and the analyzed variables had a relatively normal distribution.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

| Variable | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Flourishing | 41.38 | 10.64 | -1.19 | 0.82 | — | |||

| 2-Fear of COVID-19 | 20.12 | 5.80 | -0.13 | -0.50 | -0.04 | — | ||

| 3-Presence of Meaning | 21.45 | 6.14 | -0.49 | -0.43 | 0.13* | -0.22*** | — | |

| 4-Search for Meaning | 23.65 | 7.94 | -0.58 | -0.72 | 0.03 | -0.28*** | 0.79*** | — |

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Measurement model

There were four latent constructs (flourishing, fear of COVID-19, presence of meaning, and search for meaning) and thirteen observed variables included in the measurement model. Initially, the fit statistics revealed poor fit indices, however, after item 9 of the presence of meaning and two residual covariance between items (fcpar1 and fcpar2; mil1 and mil4) were removed, the measurement model provided an acceptable goodness-of-fit indices to the data. The ratio of the χ2 to the degrees of freedom (χ2/df = 3.77) and the goodness-of-fit indices (CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, GFI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.09) were within the acceptable range (MacCallum et al., 1996). The composite reliability coefficients were greater than 0.70 (0.89 to 0.93) indicating an acceptable level. The average variance extracted was above 0.50 (0.71 to 0.86) suggesting that each construct possessed high internal consistency. Moreover, based on the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio results, the discriminant validity requirements were also met (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 3 presents detailed information about reliability, averave variance extracted, and heterotrait-monotrait ratio.

Table 3.

Composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

| Variable | CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fear of COVID-19 | 0.887 | 0.823 | 0.1 | 1.473 | ||||

| 2. Flourishing | 0.922 | 0.858 | 0.057 | 1.104 | 0.065 | |||

| 3. Presence of Meaning | 0.908 | 0.713 | 0.725 | 0.92 | 0.316 | 0.272 | ||

| 4. Search for Meaning | 0.928 | 0.721 | 0.725 | 0.935 | 0.359 | 0.035 | 0.835 |

Structural model

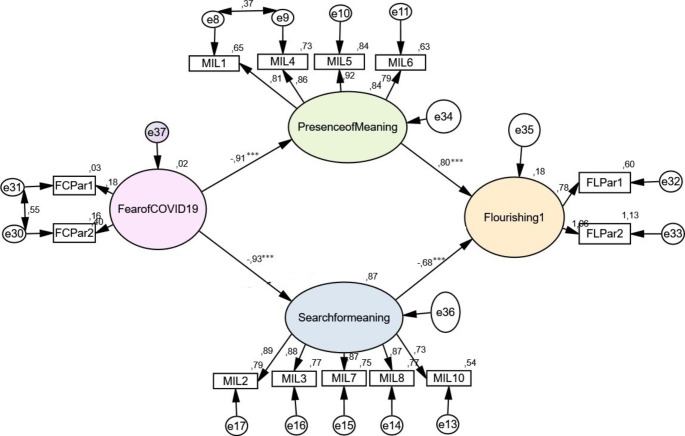

Effects of fear of COVID-19 on flourishing via the presence of meaning and search for meaning was tested. The goodness of fit indices of the study was acceptable (χ2/df = 3.7, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, GFI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.09). Consequently, standardized factor loadings of models were given in Fig. 1.

The findings from Fig. 1 demonstrated that fear of the COVID-19 strongly and negatively predicted both the presence of meaning (β=-0.91, p < .001) and the search for meaning (β =-0.93, p.001). It was discovered that flourishing was positively impacted by the presence of meaning (β = 0.80, p < .001). The search for meaning significantly and adversely affected flourishing (β =−0.68, p < .001). Fear of COVID-19 = X; Search for meaning = M1; and Presence of meaning = M2; explained 18% of the dependent variable (flourishing).

Fig. 1.

Standardized factor loading for the structural model. Note. N = 312; * p < .05, *** p < .001. FLpar, parcels of Flourishing, FCPar, parcels of fear of COVID-19. The model was tested with age and gender as covariates, and the results (χ2/df = 3.7, CFI = .94, TLI = .92, GFI = .89, SRMR = .08, RMSEA = .09) demonstrated that the effects of these covariates on the model were not statistically significant.

Bootstrapping results

The structural model was tested for significance using a bootstrap sample of 5,000 in the bootstrap estimation procedure. Direct and indirect effects of the model were given in Table 4. Fear of COVID-19 had a significant direct effect on Presence of Meaning (β = -0.92; 95% CI= -1.01, -0.81) and Search for meaning (β = -0.93; 95% CI = -1.03, -0.84). Flourishing was directly affected by the presence of meaning (β = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.58, 1.03) and search for meaning (β = -0.68; 95% CI =-0.87, -0.50). Indirect effect of fear of COVID-19 on flourishing via the presence of meaning was significant 1.76 (95% CI = 1.1, 2.7). Accordingly, higher fear of COVID-19 was associated with lower presence of meaning in life and higher presence of meaning in life was related with higher flourishing. Indirect effect of fear of COVID-19 on flourishing via search for meaning was significant − 2.04 (95% CI = -3.04, -1.26). Accordingly, higher fear of COVID-19 was associated with lower search for meaning and lower levels of search for meaning were related with lower tendencies of flourishing.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects for the structural model

| Model pathways | Estimated | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Direct effect | |||

| Fear of COVID-19 → Presence of Meaning | − 0.915 | -1.011 | − 0.808 |

| Fear of COVID-19 → Search for meaning | − 0.931 | -1.033 | − 0.837 |

| Presence of meaning → Flourishing | 0.805 | 0.576 | 1.027 |

| Search for meaning → Flourishing | − 0.682 | − 0.865 | − 0.496 |

| Indirect effect | |||

| Fear of COVID-19 → Presence of meaning → Flourishing | 1.758 | 1.091 | 2.684 |

| Fear of COVID-19 → Search for meaning → Flourishing | -2.038 | -3.038 | -1.255 |

Discussion

This study explores the importance of meaning in life as a mediator between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing, by considering how meaning in life can promote the mental health of the public during the pandemic. People may tend to cope with adverse events through creating and finding meaning to the different aspects they experienced. Living one’s life as meaningful and feeling that it has meaning and purpose is positively associated with wellbeing (Lee et al., 2018; Park et al., 2008). This study has also revealed that a negative significant relationship was found between participants’ level of fear of COVID-19 and the subscales of meaning in life. Similarly, an inverse relationship was revealed between the fear of COVID-19 and flourishing.

The first hypothesis (H1), which argues that fear of COVID-19 reduces the flourishing of individuals, was tested and confirmed in this study. The higher the levels of fear of COVID-19, the more individuals’ tendency to flourish and engage in daily life activities lowers. This is consistent with the previous findings (Elemo et al., 2021) reporting an inverse relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. However, increased fear of COVID-19 was found to affect flourishing differently by gender. Increased fear of COVID-19 affected flourishing in women than men study participants (Sürücü et al., 2021). Thus, feeling scared, uncertain and anxious during the pandemic, individuals may tend to concentrate less on their daily life activities and experience negative emotions such as fear. Though fear is considered as an adaptive emotion that has functional importance in alerting individuals against threat, when intense it can reduce flourishing.

In addition, the second hypothesis (H2), which anticipated that the association between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing is mediated by the presence of meaning and search for meaning in life, was confirmed. The presence of meaning has served as a protective factor in reducing the effect of fear of COVID-19 and helped to lift the flourishing levels of individuals, while the search for meaning did not weaken the effect of fear of COVID-19 on flourishing. This finding corroborates with the previous findings (Newman et al., 2022; Schnell & Krampe, 2020; Trzebiński et al., 2020) suggest that possessing a clear meaning in life is important in serving as a protective factor against the fear of COVID-19 and in fueling the potential to thrive and experience balanced wellbeing despite the pandemic. In other words, the presence of meaning served to weaken the connection between fear of COVID-19 and flourishing. Striving towards meeting life purposes and making meaning during the COVID-19 pandemic can benefit individuals as they have a sense of direction in life (Trzebiński et al., 2020). Possessing clear life goals and striving to reach them provides one with a sense of engagement, and direction (George & Park, 2016). However, individuals seeking for meaning seem to less likely recover from the discomforts of the COVID-19 pandemic and may experience a crisis of meaning.

People who suffer from increased fear during the COVID-19, despite the desire to search for meaning, might fail to find their lives to be meaningful and may not be able to get a sense of direction, amid the pandemic crisis. Inability to achieve one’s life goals could trigger a sense of despair and meaninglessness (Steger, 2017; Ekwoyne et al., 2021). Particularly, the increased uncertainty and continuously changing situations around the COVID-19 pandemic (lockdowns, restrictions, financial instabilities, closure of businesses, etc.,) have significantly impacted individuals’ financial, career, academic, and other life goals. Thus, even though the crises in the COVID-19 pandemic might help to inspire individuals to make meaning, the increased fear and uncertainty may limit engaging in reflective thinking. Thus, despite the inverse relationship reported in the relation between fear of COVID-19 and search for meaning, engagement in the search for meaning during the COVID-19 did not seem to help to support the potential to strive for better wellbeing. Though individuals have an innate urge to find meaning in their lives, and failure to achieve meaning could lead to psychological distress (Frankl, 1985). The meaning alleviates the stresses and worries people face in the pandemic (Humphrey & Vari, 2021). Thus, people may experience difficulties due to the uncertainty and fear involved in a pandemic. And not having meaning in such periods may adversely affect their wellbeing.

According to the results of the current study, having a clear sense of meaning during the apparently ongoing COVID-19 pandemic protects the tendency to flourish and encourages functionality. This study also allows researchers to gain a better understanding of the two dimensions of meaning in life: the search for meaning and the presence of meaning could be associated with fear of COVID-19 and well-being. Thus, despite the COVID-19 discomforts, providing opportunities in which individuals can experience a sense of meaning and reflect inward may not only help them to maintain balanced wellbeing but also contribute to the wellness of the public as well. This is because fostering people’s sense of meaning and purpose in life can help to make sense of the events in their lives and see how things coherently fit together (Costin & Vignoles, 2020; Martela & Steger, 2016). This in turn has the potential to foster a desire to help others and engage in altruistic behaviors (e.g. volunteerism) because those who find meaning in their life are more likely to feel that they are connected to something greater than themselves (Newman et al., 2022). Thus, fostering people’s sense of meaning and purpose in life could potentially serve to save lives and promote prosocial behaviors. Therefore, it is also important that psychological interventions may consider cultivating a sense of meaning in order to uplift the resilience and wellbeing of the public during the pandemic.

Individuals are likely to feel insecure or socially isolated when it is threatened by unanticipated unpleasant event like COVID-19. Unexpected consequences of the measures taken to stop the coronavirus spread that included an increase in social isolation, an increase in emotional loneliness, and a decline in a sense of community (Wissing et al., 2020) have also worsened the crisis situation. However, despite all the threats, connecting with family, friends, the community, and one’s faith continued to provide Iranians the most significant meaning in their life during the pandemic (Shahhosseini et al., 2022). In this context, finding meaning in the difficulty by reframing the challenge in a constructive way through spiritual and religious coping can help people develop a structured framework for understanding the universe and for imagining various emotional occurrences and circumstances (Hamzehgardeshi et al., 2019; Shoshtariet et al., 2016). Thus, despite the COVID-19 threats, those with a religious outlook might have comprehended the meaning and purpose of life, and in some way guided by their faith to discover the answers to their inquiries about the pandemic crisis to manage their fear.

There are some limitations that need to be considered while interpreting the findings of the present study. First, the current study looked at the mediating role of two dimensions of meaning in life using cross-sectional data. Therefore, drawing conclusions about the causes of the variables is difficult. Therefore, it is important to think about conducting longitudinal research to track changes in the presence of meaning and the search for meaning through time. Second, the variations indicated in the percentages of male and female participants are expected given that this study used snowball sampling, which is susceptible to sampling bias; yet, there is a sizable amount of male participants. Future research are therefore recommended to close the gender gap. Finally, this study is based on online survey. Due to the pandemic, access to the study participants was possible online through social media platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Twitter. There is also a wide usage of social media (88.5%) in Iran (Chegeni et al., 2022). During the pandemic the use of technology and social platforms in Iran served the public to cope with the impact of the pandemic and the social distance instituted in response to the pandemic (Ezumah, 2013).

In conclusion, despite the limitations, this study provides important contributions about the role of the presence of meaning in life. In brief, this study findings indicate that the presence of meaning might minimize the adverse affects of fear in crisis situations and foster flourishing.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aman Sado Elemo, Email: aselemo@gelisim.edu.tr.

Ergün Kara, Email: ergunpdr@hotmail.com.

Mehran Rostamzadeh, Email: mrostamzadeh@gelisim.edu.tr.

References

- Arslan Gökmen, Yıldırım Murat, Karataş Zeynep, Kabasakal Zekavet, Kılınç Mustafa. Meaningful Living to Promote Complete Mental Health Among University Students in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2022;20(2):930–942. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00416-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsley DA. Assessing the presence of harmful collinearity and other forms of weak data through a test for signal-to-noise. Journal of Econometrics. 1982;20(2):211–253. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(82)90020-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brassai L, Piko BF, Steger MF. Meaning in life: is it a protective factor for adolescents’ psychological health? International journal of behavioral medicine. 2011;18(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao, M., Chen, X., Liu, T., Yang, H., & Hall, B. J. (2020). Psychological distress and state boredom during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: the role of meaning in life and media use. European journal of psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1769379. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1769379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chegeni Maryam, Nakhaee Nouzar, Shahrbabaki Mahin Eslami, Mangolian Shahrbabaki Parvin, Javadi Sara, Haghdoost AliAkbar, Dettori Marco. Prevalence and Motives of Social Media Use among the Iranian Population. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2022;2022:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2022/1490227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costin V, Vignoles VL. Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2020;118(4):864–884. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwoyne AU, Ezumah BA, Nwosisi N. Meaning in life and impact of COVID-19 pandemic on African immigrants in the United States. Wellbeing Space and Society. 2021;2:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wss.2021.100033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elemo, A. S., Ahmed, A. H., Kara, E., & Zerkeshi, M. K. (2021). The Fear of COVID-19 and Flourishing: Assessing the Mediating Role of Sense of Control in International Students. International journal of mental health and addiction, 1–11. 10.1007/s11469-021-00522-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elemo, A. S., Satici, S. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Ethiopian Amharic Version. International journal of mental health and addiction, 1–12. 10.1007/s11469-020-00448-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ezumah, B. A. (2013). College students’ use of social media: Site preferences, uses and gratifications theory revisited. International journal of business and social science, 4(5).

- Fornell Claes, Larcker David F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39. doi: 10.2307/3151312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning. New York: Simon and Schuster Publishers; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry PS. Religious involvement, spirituality and personal meaning for life: Existential predictors of psychological wellbeing in community-residing and institutional care elders. Aging & Mental Health. 2000;4(4):375–387. doi: 10.1080/713649965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One 15:e0231924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- George Login S., Park Crystal L. Meaning in Life as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering: Toward Integration and New Research Questions. Review of General Psychology. 2016;20(3):205–220. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halama P. “Meaning in life and coping: sense of meaning as a buffer against stress”. In: Batthyany A, editor. Meaning in positive and existential psychology. New York, NY: Russo-Netzer; 2014. pp. 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey A, Vari O. Meaning Matters: Self-Perceived Meaning in Life, Its Predictors and Psychological Stressors Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral sciences (Basel Switzerland) 2021;11(4):50. doi: 10.3390/bs11040050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karataş Zeynep, Uzun Kıvanç, Tagay Özlem. Relationships Between the Life Satisfaction, Meaning in Life, Hope and COVID-19 Fear for Turkish Adults During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:633384. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Ready EA, Davis EN, Doyle PC. Purposefulness as a critical factor in functioning, disability and health. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2017;31(8):1005–1018. doi: 10.1177/0269215516672274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew Bob, Chistopolskaya Ksenia, Osman Augustine, Huen Jenny Mei Yiu, Abu Talib Mansor, Leung Angel Nga Man. Meaning in life as a protective factor against suicidal tendencies in Chinese University students. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, A. (2001). Exploring sources of life meaning among Chinese. Unpublished Master’s thesis. Langley, Canada: Trinity Western University.

- Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2011). Meaning in life and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16(2), 150–159. 10.1080/15325024.2010.519287

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological methods. 1996;1(2):130. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markman, K. D., Proulx, T., & Lindberg, M. J. (Eds.). (2013). The psychology of meaning. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14040-000

- Martela F, Steger MF. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2016;11:531–545. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdi, S. Z. (2021, July 3). Delta variant of COVID-19 Spreading Fast In Iran. Anadolu Agency News, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/latest-on-coronavirus-outbreak/delta-variant-of-covid-19-spreading-fast-in-iran/2293488

- Milman Evgenia, Lee Sherman A., Neimeyer Robert A., Mathis Amanda A., Jobe Mary C. Modeling pandemic depression and anxiety: The mediational role of core beliefs and meaning making. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2020;2:100023. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman David B., Schneider Stefan, Stone Arthur A. Contrasting Effects of Finding Meaning and Searching for Meaning, and Political Orientation and Religiosity, on Feelings and Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2022;48(6):923–936. doi: 10.1177/01461672211030383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Malone MR, Suresh DP, Bliss D, Rosen RI. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Park M, Peterson C. When is the search for meaning related to life satisfaction? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2010;2(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01024.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prager E. Exploring personal meaning in an age-differentiated Australian sample: Another look at the Sources of Meaning Profile (SOMP) Journal of Aging Studies. 1996;10(2):117–136. doi: 10.1016/S0890-4065(96)90009-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reker G. T., Wong P. T. P. (1988). Aging as an individual process: Toward a theory of personal meaning. In Birren J. E., Bengtson V. L. (Eds.), Emergent theories of aging (pp. 214-246). New York, NY: Springer.

- Reker, G. T., & Chamberlain, K. (Eds.) (2000). Exploring existential meaning: Optimizing human development across the life span. SAGE Publications, Inc., 10.4135/9781452233703

- Schaefer SM, Boylan M, van Reekum J, Lapate CM, Norris RC, Ryff CJ, Davidson RJ. Purpose in life predicts better emotional recovery from negative stimuli. PloS one. 2013;8(11):e80329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell T, Krampe H. Meaning in Life and Self-Control Buffer Stress in Times of COVID-19: Moderating and Mediating Effects With Regard to Mental Distress. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2020;11:582352. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.582352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Shahhosseini Z, Azizi M, Marzband R, Ghaffari SF, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Personal Meaning Profile in Iran. Journal of religion and health. 2022;61(4):3443–3457. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshtari LT, Monadi M, Ashkezari MK, Khamesan A. Identifying students’ meaning in life: A phenomenological study. Biannual Journal of Applied Counseling. 2016;6(1):59–76. doi: 10.22055/jac.2016.12568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Fitch-Martin AR, Donnelly J, Rickard KM. Meaning in life and health: Proactive health orientation links meaning in life to health variables among American undergraduates. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2015;16(3):583–597. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9523-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Kashdan TB, Sullivan BA, Lorentz D. Understanding the search for meaning in life: personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of personality. 2008;76(2):199–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M. F. (2017). Meaning in life and wellbeing. Recovery and mental health. In M. Slade, L. Oades, & A. Jarden (Eds.), Wellbeing, recovery and mental health (pp. 75–85). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781316339275.004

- Steger Michael F., Frazier Patricia, Oishi Shigehiro, Kaler Matthew. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sürücü Lütfi, Ertan Şenay Sahil, Bağlarbaşı Evren, Maslakçı Ahmet. COVID-19 and human flourishing: The moderating role of gender. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;183:111111. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzebiński Jerzy, Cabański Maciej, Czarnecka Jolanta Zuzanna. Reaction to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Meaning in Life, Life Satisfaction, and Assumptions on World Orderliness and Positivity. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2020;25(6-7):544–557. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1765098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Cuiyan, Pan Riyu, Wan Xiaoyang, Tan Yilin, Xu Linkang, Ho Cyrus S., Ho Roger C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissing, M. P., Wilson Fadiji, A., Schutte, L., Chigeza, S., Schutte, W. D., & Temane, Q. M. (2020). Motivations for Relationships as Sources of Meaning: Ghanaian and South African Experiences. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 2019. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wong PTP. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology. 2011;52(2):69–81. doi: 10.1037/a0022511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worldometer (2021). (n.d.). Iran Coronavirus Cases. Retrieved September 29, from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/iran/