Abstract

Background

Imprinting disorders, which affect growth, development, metabolism and neoplasia risk, are caused by genetic or epigenetic changes to genes that are expressed from only one parental allele. Disease may result from changes in coding sequences, copy number changes, uniparental disomy or imprinting defects. Some imprinting disorders are clinically heterogeneous, some are associated with more than one imprinted locus, and some patients have alterations affecting multiple loci. Most imprinting disorders are diagnosed by stepwise analysis of gene dosage and methylation of single loci, but some laboratories assay a panel of loci associated with different imprinting disorders. We looked into the experience of several laboratories using single-locus and/or multi-locus diagnostic testing to explore how different testing strategies affect diagnostic outcomes and whether multi-locus testing has the potential to increase the diagnostic efficiency or reveal unforeseen diagnoses.

Results

We collected data from 11 laboratories in seven countries, involving 16,364 individuals and eight imprinting disorders. Among the 4721 individuals tested for the growth restriction disorder Silver–Russell syndrome, 731 had changes on chromosomes 7 and 11 classically associated with the disorder, but 115 had unexpected diagnoses that involved atypical molecular changes, imprinted loci on chromosomes other than 7 or 11 or multi-locus imprinting disorder. In a similar way, the molecular changes detected in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and other imprinting disorders depended on the testing strategies employed by the different laboratories.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, we discuss how multi-locus testing might optimise diagnosis for patients with classical and less familiar clinical imprinting disorders. Additionally, our compiled data reflect the daily life experiences of diagnostic laboratories, with a lower diagnostic yield than in clinically well-characterised cohorts, and illustrate the need for systematising clinical and molecular data.

Keywords: Imprinting disorders, Genetic testing, Multi-locus testing, Unexpected molecular diagnosis, Overlapping phenotypes, Multi-locus imprinting disorder

Introduction

Imprinting disorders have a common aetiology in disturbed expression of imprinted genes, but have heterogeneous clinical features affecting growth, development, metabolism, behaviour and lifetime risk of metabolic or neoplastic disease [1, 2]. Their estimated total incidence is ~ 1:3000 live births, but uncertainty remains about their frequency and presentation. Whereas the prevalences of the well-known Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS), Angelman syndrome (AS) or Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) have been established, the prevalence for others is unknown or estimates vary by several-fold. Some imprinting disorders are recently recognised and awaiting clinical delineation, and some presentations are likely under-recognised and under-diagnosed [2, 3].

The allelic expression of imprinted genes is defined epigenetically according to their parent of origin, under the control of imprinting centres (ICs) that contain differentially methylated regions (DMRs) with parent of origin-specific DNA methylation [1]. Imprinted genes are expressed from one parental allele only, and pathology arises when their expression level is altered, by changes in the coding sequences or copy number variants (CNVs) affecting the expressed allele; or by meiotic/mitotic errors (uniparental disomy, UPD (inheritance of an entire chromosome or part of it from the same parent)) or imprinting disturbances altering the representation of the expressed alleles (imprinting defect, epimutation), as either loss or gain of methylation (LOM, GOM) [2, 4]. In some molecular subgroups of imprinting disorders, multiple imprinted loci are affected. These include paternal uniparental diploidy (inheritance of all chromosomes from the same parent), generally presenting as Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), and multi-locus imprinting disorder (MLID) [5–8]. Because imprinting disorders can arise from genetic or epigenetic errors, molecular testing must include both genetic and epigenetic analysis, sometimes spanning multiple imprinted loci, in order to arrive at a confirmed diagnosis [9–11]. In case of MLID, so-called maternal effect variants have recently been identified as causative. These genetic variants affect genes encoding members of the subcortical maternal complex (SCMC) which is involved in the maintenance of the maternal imprint in the oocyte and the early embryo (for review: [12]).

Current diagnostic testing protocols for imprinting disorders reflect international guidelines (e.g. [9, 10, 13, 14]), and in most laboratories, commercial diagnostic kits are employed. Many laboratories diagnose imprinting disorders using MS-MLPA (methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification), which detects both genetic (CNVs) and epigenetic (DNA methylation) disturbances. While some assays focus on single imprinted loci, others include imprinted loci associated with different imprinting disorders, achieving broader coverage with lower analytic density.

With the increasing use of exome and genome sequencing as first-line investigations for genetic diagnosis, patients with broad categories of clinical features undergo simultaneous testing of relevant genes and the sequencing data are analysed by disease-specific “virtual gene panels”. Such a multi-locus approach for imprinting disorders (simultaneously interrogating multiple imprinted loci) could improve the turnaround, efficiency and cost of diagnosis, but it could potentially detect genetic disturbances at loci analysis of which was not specifically requested by the referring clinician. This could result in incidental and “unforeseen” diagnoses with management or counselling implications that might be welcome, unwelcome, or unclear to the clinician and family. Genome-wide DNA methylation panels have gained recognition as a potentially powerful tool for diagnosing genetic syndromes associated with distinctive genomic DNA methylation patterns (episignatures) [Sadikovic et al. [45], but they are not currently widely adopted for imprinting disorders, perhaps because they are relatively novel, because of cost and accessibility considerations or because of the potential for incidental findings.

Diagnostic laboratories in different nations have different legal and ethical relationships with the clinicians and patients they serve and hence have different approaches to genomic panel testing in general and to multi-locus imprinting testing in particular. We looked at the experience of laboratories using single-gene and multi-locus approaches for molecular diagnosis of imprinting disorders. We aimed to assess whether multi-locus approaches increased diagnostic rate, whether unforeseen diagnoses were made and what issues might result for clinicians and families, and based on this, to propose potential workflows for multi-locus testing of imprinting disorders.

Results and discussion

Eleven diagnostic laboratories provided data for 16,364 affected individuals tested for the eight imprinting disorders molecularly characterised by different (epi)genetic alterations (Table 1). The rates and subtypes of diagnoses varied between disorders, and also between laboratories for individual disorders. These differences probably reflect the (epi)genetic features of the disorders, as well as variations in clinical referral patterns, diagnostic approaches of laboratories and demographic features of referral populations. Furthermore, some laboratories are (national) expert centres for specific diseases, and therefore, some subgroup data might be distorted. As standard diagnostic testing for imprinting disorders in all contributing centres was based on peripheral blood samples, some cases might have escaped detection due to mosaicism and different sensitivities of the applied tests, a feature which is characteristic for the imprinting defects and upd(11)pat in BWSp. Thus, some results might be false negative, but this ratio is currently indeterminable as systematic studies on the relevance of mosaicism in imprinting disorders are not available and are difficult to conduct. However, the relative detection rates for the already known molecular subtypes generally correspond to published data.

Table 1.

Detection rates from the different centres for the imprinting disorders associated with aberrant imprinting marks

| Laboratory | Aachen/DEa | Amsterdam/NL | Essen/DE | Madrid/ES | Milano/IT | Paris/FR | Salisbury/UK | Tokyo, Hamamatsu/JP | Vitoria-Gasteiz/ES | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line test | Molecular diagnosis | ME030/ME032 + ME034 | ME030/ME032 | ME030/ME032; ME034 for research | ME030/ME032 + ME034 + SNParray | ME030/ME032 | ASMM-RT qPCR (IC2, MEST, GRB10, MEG3, IG-DMR} |

ME030/ME032 | MS- pyrosequencing (IC1, IC2, IG-DMR, PEG 10, MEST) |

ME030/ME032;ME034 for research | Total number | ratio of molecular subgroups (resolved + unresolved) in the total cohort |

| SRS | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | 1164 | 546 | 287 | 348 | 586 | 876 | 388 | 455 | 71 | 4721 | ||

| "Expected" molecular diagnoses | IC1 LOM | 158 | 36 | 27 | 44 | 62 | 97 | 27 | 113 | 8 | 572 | 67,6 |

| 11p15CNVs | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | NA | 1 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 2,4 | |

| upd(11)mat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0,6 | |

| upd(7)mat | 37 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 17 | 21 | 10 | 31 | 1 | 134 | 15,8 | |

| Sum "expected" diagnoses | 203 | 43 | 33 | 58 | 81 | 118 | 39 | 147 | 9 | 731 | ||

| % "Expected" positive diagnoses | 17,4 | 7,9 | 11,5 | 16,7 | 13,8 | 13,5 | 8,2 | 32,3 | 12,7 | 15,5 | ||

| Unexpected molecular diagnoses | IC2 LOM | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 1,5 |

| chromosome 7 alterations | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0,9 | |

| 14q32 alterationsb | 10 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 70 | 8,3 | |

| upd(6)mat | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 1 | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 7 | 0,8 | |

| upd(20)mat | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 3 | NA | NA | 6 | NA | 10 | 1,2 | |

| PWS | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 3 | 0,4 | |

| upd(11)pat | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0,5 | |||||||

| Sum "unexpected" diagnoses | 20 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 13 | 32 | 6 | 25 | 1 | 115 | ||

| % total diagnostic yield (expected + unexpected) | 19,2 | 8,4 | 11,5 | 21,0 | 16,0 | 17,1 | 11,6 | 37,8 | 14,1 | 17,9 | ||

| percentage of unexpected finding among the total findings | 9,0 | 6,5 | 0,0 | 20,5 | 13,8 | 21,3 | 13,3 | 14,5 | 10,0 | 13,6 | ||

| MLIDc,d | 10 | 0 | NA | 0 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 29 | 5,1 | ||

| First-line test*** | ME030 + ME034 | ME030 | ME030; ME034 for research | ME030 | ME030; ME034 for research | ASMM-RTqPCR (IC1/IC2/M EST, G RB10 /DLK 1/GTL2) | ME030 | MS-Pyrosequencing H19 IGF2, IG-DMR, PEG10, MEST) | ME030; ME034 if positive in ME030 | Total number | Ratio of molecular subgroups (resolved + unresolved) in the total cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWS | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | 475 | 756 | 400 | 679 | 1028 | 1258 | 269 | 169 | 66 | 5100 | ||

| Expected molecular diagnoses | IC1 GOM | 16 | 16 | 10 | 4 | 17 | 73 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 153 | 11,8 |

| IC2 LOM | 78 | 84 | 60 | 152 | 184 | 201 | 27 | 32 | 15 | 833 | 64,0 | |

| CNVs 11p | 9 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 2,5 | |

| upd(11)pat | 44 | 39 | 20 | 14 | 83 | 0 | 16 | 32 | 6 | 254 | 19,5 | |

| Of these uniparental diploidyd | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 | |||

| Sum "expected" diagnoses | 147 | 144 | 94 | 172 | 291 | 274 | 45 | 81 | 24 | 1272 | ||

| % "expected" positive diagnosee | 30,9 | 19,0 | 23,5 | 25,3 | 28,3 | 27,8 | 16,7 | 47,9 | 36,4 | 24,9 | ||

| unexpected molecular diagnoses | IC1 LOM | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 27 | 2,1 |

| PHP | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 2 | 0,2 | |

| Sum "unexpected" diagnoses | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 29 | ||

| % total diagnostic yield (expected + unexpected) | 31,6 | 19,0 | 23,5 | 27,0 | 28,6 | 22,5 | 16,7 | 49,1 | 37,9 | 25,5 | ||

| Percentage of unexpected findings among the total findings | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 6,0 | 1,0 | 3,2 | 0,0 | 2,4 | 4,0 | 2,2 | ||

| MLIDcd | 21 | 3 | 3 | 20 | 25 | 22 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 107 | 12,8 | |

| Laboratory | Aachen/DE | Amsterdam/NL | Essen/DE | Madrid/ES | Milano/IT | Salisbury/UK | Tokyo, Hamamatsu/JP | Vitoria- Gasteiz/ES | Additional specialist laboratoriesf | Total number | ratio of molecular subgroups in the total cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line test | Molecular diagnosis | disease-specific (MLPA) assays | ||||||||||

| PWSg | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | 33 | 344 | 825 | 218 | 420 | 400 | 260 | 87 | 420 | 3007 | ||

| Molecular diagnoses | SNRPN ID | 4 | 0 | 32 | 2 | 13 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 64 | 10,0 |

| del 15 pat | 6 | 20 | 59 | 9 | 22 | 15 | 18 | 3 | 100 | 252 | 39,4 | |

| upd(15)mat | 1 | 7 | 48 | 13 | 20 | 10 | 49 | 10 | 0 | 158 | 24,7 | |

| dup 15 mat | 0 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 18 | 2 | 29 | 66 | 10,3 | |||

| upd(15)mat/ID unresolved | 0 | 2 | 32 | 0 | 26 | 5 | 35 | 0 | 0 | − 100 | 15,6 | |

| total | 11 | 32 | 177 | 32 | 81 | 49 | 113 | 14 | 131 | 640 | ||

| % positive diagnoses | 33,3 | 9,3 | 21,5 | 14,7 | 19,3 | 12,3 | 43,5 | 16,1 | 3f,2 | 21,3 | ||

| ASg | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | 17 | 103 | 631 | 131 | 630 | 165 | 49 | 87 | NA | 1813 | ||

| Molecular diagnoses | SNRPN ID | 2 | 0 | 77 | 4 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 116 | 232 | 28,5 |

| del 15 mat | 2 | 6 | 31 | 10 | 88 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 160 | 320 | 39,3 | |

| upd(15)pat | 0 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 38 | 76 | 9,3 | |

| dup 15 pat | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 1,5 | |

| UBE3Ah | NA | 3 | 3 | 1 | 52 | NA | 2 | 3 | 64 | 128 | 15,7 | |

| upd(15)paVID unresolved | 0 | 4 | 0 | NA | 6 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 23 | 46 | 5,7 | |

| total | 4 | 18 | 124 | 19 | 179 | 12 | 37 | 14 | 407 | 814 | ||

| % positive diagnosesh | 23,5 | 17,5 | 19,7 | 14,5 | 28,4 | 7,3 | 75,5 | 16,1 | NA | NA | ||

| TS14b,g | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | 144 | 8 | 1 | 73 | 57 | 1 | 284 | |||||

| Molecular diagnoses | upd(14)mat | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 21 | 1 | NA | 40 | 48,8 |

| del(14q32)pat | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | NA | 9 | 11.0 | |

| ID | NA | NA | 9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 0 | NA | 25 | 30,5 | |

| upd(14)mat/ID unresolved | NA | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | NA | 8 | 9,8 | |

| total | 14 | 4 | 1 | 17 | 45 | 1 | 82 | |||||

| % positive diagnoses | 9,7 | 50,0 | 100,0 | 23,3 | 78,9 | 100,0 | 28,9 | |||||

| KOS14g | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | NA | NA | 8 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 76 | 1 | NA | 98 | ||

| Molecular diagnoses | upd(14)pat | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 26 | 0 | NA | 33 | 46,5 |

| del(14q32)mat | NA | NA | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1 | NA | 14 | 19,7 | |

| ID | NA | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | NA | 17 | 23,9 | |

| upd(14)pat/ID unresolved | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | NA | 7 | 9,9 | |

| total | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 54 | 1 | 71 | |||||

| % positive diagnoses | 62,5 | 50,0 | 100,0 | 100,0 | 71,1 | 100,0 | 72,4 | |||||

| PHpg,h | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 335 | 175 | 239 | NA | 753 | |||

| Molecular diagnoses | upd(20)pat | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 4 | 0 | 7 | NA | 12 | 2,5 | |

| del(20)mat | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | NA | 9 | 1,9 | ||

| ID | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 117 | 27 | 58 | NA | 202 | 42,6 | ||

| upd(20)mat/ID unresolved | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 19 | NA | 20 | 4,2 | |||

| STX16 del | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 34 | 36 | 19 | NA | 89 | 18,8 | ||

| GNAS mutations | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 43 | 99 | NA | 142 | 30,0 | |||

| total | 1 | 157 | 125 | 191 | 474 | |||||||

| % positive diagnoses | 25,0 | 46,9 | 71,4 | 79,9 | 62,9 | |||||||

| TNDMg | ||||||||||||

| Referrals (total number) | NA | NA | 12 | 6 | NA | 272 | 6 | 1 | 291 | 588 | ||

| Molecular diagnoses | upd(6)pat | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | NA | 44 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 70 | 34,0 |

| dup(6)pat | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 23 | 1 | 0 | 26 | 52 | 25,2 | ||

| ID | NA | NA | 0 | 2 | NA | 45 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 66 | 32,0 | |

| of these, ZFP5T | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17 | NA | NA | 7 | 24 | ||

| upd(6)pat/ID unresolved | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 18 | 8,7 | |

| total | 2 | 3 | 121 | 6 | 1 | 73 | 206 | |||||

| % positive diagnoses | 16,7 | 50,0 | 44,5 | 100,0 | 100,0 | 25,1 | 35,0 | |||||

(ID imprinting defect (epimutation). NA not assessed/assessable.

athe majority of data from Aachen/DE have already been included in [22]]

bTS14 overlaps with SRS and PWS and does not have strict clinical criteria

cMLID detection rate depends on the tests applied by the laboratory. MLID % given as percentage of individuals with an imprinting anomaly, not as percentage of total referrals.

dnot (systematically) analysed by all laboratories and not in all patients.

ein some laboratories, CDKN1C sequencing is included in first-line testing but results are not listed here.

fadditional specialist centres with expertise in the respective disorders are: Exeter/UK (TNDM); Toulouse/FR (PWS).

gReferral for these disorders is biased, e.g. because samples were forwarded after exclusion of large deletions (e.g. in case of PWS, AS) or other pretesting steps.

hUBE3A and GNAS sequencing analysis have not been performed in all laboratories. Unresolved: Some MS tests do not discriminate the molecular cause of DNA methylation change: for example, MS PCR does not discriminate between CNV, UPD or imprinting defect; MS-MLPA cannot distinguish between UPD and imprinting defects. Discrimination entails additional tests such as microsatellite analysis or SNP array analysis, but these tests require parental DNA samples and/or allow identification only of uniparental isodisomy. In some patients with PWS, AS, TS14, KOS14 and TNDM, parental DNA samples were not available, additional testing was not performed, and therefore, discrimination between UPD and imprinting defects was not possible. These samples are identified as “unresolved”.)

For clarity, observations from different disorders will be considered separately, in descending order of number of referred samples in the study.

Silver–Russell syndrome and Silver–Russell syndrome-related phenotypes

The major molecular findings in SRS are LOM of H19/IGF2:IG-DMR in 11p15 (SRS-11p) and upd(7)mat (SRS-upd(7)mat); therefore, international guidelines recommend testing of the chromosomes 11p15.5 and 7 DMRs [9]. Thus, many laboratories use two MS-MLPA kits (ME030, ME032) which interrogate DMRs on chromosomes 6, 7, 11 and 14.

In total, 4721 patients had been referred for SRS testing. Interrogating the DMRs of chromosomes 7 and 11 only, diagnostic rates varied from 7.9 to 32.3% (average 15.5%), which may reflect whether clinicians referred only the children meeting clinical thresholds, or referred also for diagnoses of exclusion. Among the positively tested patients (expected and unexpected findings), 67.6% and 15.8% represented H19/IGF2:IG-DMR LOM and upd(7)mat, respectively. By first-line testing, CNVs affecting the 11p15.5 DMRs and upd(11)mat were identified as well, but they were rare (2.4% and 0.6%, respectively). Five cases of upd(11)pat were diagnosed, illustrating the occasional challenge of differentiating between lateralised overgrowth (hemihyperplasia) or undergrowth (hemihypoplasia) as a cause of body asymmetry and the value of molecular diagnosis for instituting tumour surveillance [15–17].

Laboratories using the ME032 assay (Table 2) detected further imprinting disturbances in children with SRS features, including LOM of the MEG3:TSS-DMR in 14q32 (molecularly corresponding to TS14, SRS-14q) and GOM of the PLAGL1:alt-TSS-DMR (e.g. [18, 19]). Laboratories testing for TS14 identified 70 SRS individuals (8.3% diagnostic rate), confirming the value of chromosome 14 testing in SRS referrals. Clinical features of TS14 patients overlap with the features of both SRS and PWS, potentially related to both the age of the patient and the genetic lesion involved [18, 20, 21].

Table 2.

Imprinted DMRs which should be addressed in (future) multi-locus assays

| Imprinted DMR | Chromosome | Imprinting disorder in which the DMR is primarily alteredc | Physical position (GRCh38/hg38) | Addressed by MS-MLPA assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLAGL1:alt-TSS-DMR | 6q24.2 | TNDM upd(6)mat | chr6:g.144006941 -144,008,751 | ME032, ME033, ME034 |

| GRB10:alt-TSS-DMR | 7p12.1 | SRSd | chr7:g.50781029 -50,783,615 | ME032, ME034 |

| MEST:alt-TSS-DMR | 7q32.2 | SRSd | chr7:g.130490281 -130,494,547 | ME032, ME034 |

| H19/IGF2:IG-DMR | 11p15.5 | SRS, BWS | chr11:g.1997582 -2,003,510 | ME030, ME034 |

| KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR | BWS | chr11:g.2698718 -2,701,029 | ME030, ME034 | |

| MEG3:TSS-DMRb | 14q32.2 | TS14, KOS14 | chr14:g.100824187 -100,827,641 | ME032, ME034 |

| MEG3/DLK1:IG-DMRa | chr14:100,811,001–100,811,037 | None | ||

| MAGEL2:TSS-DMRb | 15q11.2 | PWS, AS | chr15:g.23647278 -23,648,882 | ME028 |

| SNURF:TSS-DMR | chr15:g.24954857 -24,956,829 | ME028, ME034 | ||

| ZNF597:TSS-DMR | 16p13.3 | upd(16)mat | chr16:g.3442828 -3,444,463 | None |

| PEG3:TSS-DMR | 19q13.43 | chr19:g.56837125 -56,841,903 | ME034 | |

| GNAS-NESP:TSS-DMR | 20q13.32 | PHP upd(20)mat | chr20:g.58838984 -58,843,557 | ME031, ME034 |

| GNAS-AS1:TSS-DMR | chr20:g.58850594 -58,852,978 | ME031, ME034 | ||

| GNAS-XL:Ex1-DMR | chr20:g.58853850 -58,856,408 | ME031, ME034 | ||

| GNAS A/B:TSS-DMR | chr20:g.58888210–58,890,146 | ME031, ME034 |

With the exception of PEG3:TSS-DMR, all are associated with clinical pictures. The physical positions are based on [47] with the exception of MEG3/DLK1:IG-DMR (a) which has been determined by [48]. (bThese DMRs represent secondary DMRs. cIn case an imprinting disorder locus comprises several DMRs, the DMRs might be differentially affected by the molecular subtypes. Just internationally accepted imprinting disorders are listed. dThese DMRs are affected by (segmental) upd(7)mat or CNVs, but isolated IDs have not yet been described.)

Laboratories performing multi-locus testing made additional diagnoses, including upd(6)mat (n = 7), upd(20)mat (n = 10) and PWS (n = 3). PWS in particular is an important diagnosis for intensive targeted management. The rate of 5.1% of MLID among individuals with H19/IGF2:IG-DMR LOM confirmed data from the literature [22], but this number might be an underestimate, as not all patients with H19/IGF2:IG-DMR LOM are routinely tested for MLID.

In total, testing for atypical imprinting disturbances on chromosomes 11, 14, 15,and 20 increased the rate of positive diagnoses by 2.5%, with a range of 0.5–5.5%, probably reflecting the range of additional tests performed by laboratories, and the (epi)genetic and/or phenotypic heterogeneity of clinical referrals. This suggests that diagnosis could be streamlined by a multi-locus approach. Ideally, first-line testing would comprise DNA methylation analysis spanning imprinted loci on chromosomes 6, 7, 11, 14, 15, 16, 20. Clinicians referring SRS patients for first-line testing might receive unexpected diagnoses of PWS, BWS or MLID unless specifically opting out to receive secondary diagnoses.

Of note, coding variants in several genes that can give rise to SRS-like presentations (e.g. IGF2, HMGA2, PLAG1, CDKN1C) are not represented in this survey.

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome/Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome spectrum

BWSp is associated with (epi)genetic defects of two imprinted loci on chr11p15 (H19/IGF2:IG-DMR/IC1, KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR/IC2) which must both be analysed in first-line testing as recommended by the international guidelines [16]. In total, 5,100 individuals were referred for BWS testing, with the majority being analysed by MS-MLPA with the chromosome 11p15 assay (ME030).

The diagnostic rate targeting the 11p15.5 loci was 24.9% (range 10.4–47.9%). The variation in diagnostic rate between laboratories may reflect different referral patterns, from diagnosis of exclusion to adherence to international guidelines, or different thresholds for detection and reporting of molecular mosaicism. Prevalence of different molecular diagnoses were broadly in accord with published data: LOM of KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR (64.0%), upd(11)pat (19.5%) and GOM of H19/IGF2:IG-DMR (11.8%) [10].

The majority of patients have either KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR LOM or upd(11)pat, each of which carries a risk of multi-locus methylation change, either MLID or paternal uniparental diploidy, respectively. Some laboratories tested for MLID in individuals shown to have KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR LOM, either in routine diagnostic workup or on research basis, and 107 had MLID. The overall rate of MLID was 12.7% but multi-locus tests were not conducted in all patients. Among 254 individuals with upd(11)pat, 11 had paternal uniparental diploidy; this detection rate (4.3%) is probably an underestimate reflecting limited adoption of testing among laboratories [22]. Reported individuals with paternal uniparental diploidy show different neoplasia predisposition from the other molecular subtypes of BWSp, but description of further cases would be valuable to guide targeted management [5, 8, 23, 24]. Patients with uniparental diploidy also have an increased risk of rare recessive disorders resulting from homozygosity for recessive pathogenic variants.

Of note, one laboratory molecularly diagnosed PHP in two cases referred for BWS and showing imprinting defects at both 11p15 and chromosome 20 DMRs [25]. Overgrowth is recognised in both disorders, but overlap between them is little recognised and warrants further consideration.

It should be noted that pathogenic variants in CDKN1C significantly contribute to the molecular spectrum of BWS (for review: [10]), but are not considered in this study as CDKN1C sequencing is not performed in the first-line workup.

In summary, the data presented here provide an argument for multi-locus analysis not necessarily as first-line testing, but as a secondary test after positive diagnoses of KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR LOM. As already suggested, patients diagnosed with upd(11)pat have to be tested for paternal uniparental diploidy [10].

Further imprinting disorders associated with single imprinted loci

PWS, AS, TS14, KOS14, PHP, TNDM

For these disorders, multi-locus analysis is not required in the first-line testing, and reflecting this, very limited data are available on MLID or other atypical diagnoses.

PWS/AS, which involve the imprinted SNRPN/UBE3A gene cluster on chromosome 15, were under-represented in this survey compared to their prevalence (both ~ 1:15,000); this may reflect the delivery of PWS/AS diagnostics across many regional centres, compared to the rarer imprinting disorders and national specialist centres audited in this study. As a result, the detection rates for the different molecular subgroups are biased and not representative; in particular, the ratio of 15q11q13 deletions is much lower than expected [26, 27]. Between 5.7 and 15.6% of patients remained without a clear molecular diagnosis in AS and PWS, respectively (designated as “unresolved” in Table 1), due to the lack of parental samples to discriminate between UPD and imprinting defects.

PWS diagnosis is critical for implementing management that transforms clinical outcome [14], and thus, a low clinical threshold is applied for testing, leading to a diagnostic rate of 21.3%. There is some clinical overlap between PWS and TS14 [4], and in one cohort of individuals with PWS features, TS14 was diagnosed as frequently as PWS [21], suggesting that further investigation into a shared diagnostic pathway is warranted. Among patients referred for AS testing, unexpected findings were not commonly observed.

TS14: As discussed above, features of TS14 variably overlap with SRS and PWS, with SRS features (SGA, PNGR, relative macrocephaly, feeding difficulties) being more prevalent in infancy and features reminiscent of PWS (hypotonia, tendency to weight gain) increasingly recognisable in childhood. Therefore, direct referral for TS14 was uncommon in this cohort, and the total number of 284 individuals were likely to represent a cohort of patients with mixed phenotypes. As a result, total detection rate of 28.9% is not easy to interpret. However, our study helps to establish the contribution of the different molecular subgroups to the spectrum of molecular TS14, with upd(14)mat as the major group (48.8%), followed by isolated imprinting defects (30.5%) and paternal deletions affecting 14q32 (11%). These proportions resemble those observed in recent papers [28, 29], whereas in early reports imprinting defects and deletions were considerably less frequent than upd(14)mat [18]. This discrepancy probably reflects an ascertainment bias, as the first TS14 patients were carriers of Robertsonian translocations, whereas imprinting defects and deletions were difficult to detect at that time due to methodological limitations.

KOS14: Classical clinical features of KOS14 are distinctive, severe and life-shortening, but with increasing recognition of the disorder, less severely affected individuals have been identified [30, 31]. Due to its rarity only 98 cases were audited here, but the diagnostic rate approached 73%: among the resolved cases, 46.5% had upd(14)pat, 19.7% had deletions within the maternal allele, and 23.9% imprinting defects.

PHP has relatively specific clinical features, including biochemically measurable abnormalities of calcium, phosphate and parathyroid hormone levels, with variable expressivity of dysmorphisms and bone anomalies [11]. Its prevalence is not known, but it is estimated to be 0.34–1.1 in 100,000 [13]. In our cohort, the total diagnostic rate of 62.9% was lower than the published diagnostic rate which was around 80%, probably because GNAS sequencing was not performed by all laboratories, as recommended by the clinical consensus guidelines for inactivating PTH/PTHrP signalling disorders (iPPSD) [13]. Where GNAS sequencing was performed, it yielded a diagnostic rate of approximately 30%, which coincides with the previous reports [32]. For the group with methylation alterations, in detail, the majority had imprinting defects (42.6%), followed by STX16 deletions, causing a GNAS A/B hypomethylation in cis (18.8%). Paternal upd(20) and larger deletions are rare in PHP.

TNDM has an estimated prevalence of 1:300,000, and as such, limited molecular data are available from centres often offering international diagnostic support. The proportions of different molecular diagnoses were in accord with published data [33]. Importantly, 24 of 66 patients with imprinting defects had MLID with biallelic ZFP57 variants and others had MLID without a ZFP57 variant. Finding of a ZFP57 variant has genetic counselling implications, independent of the management and counselling implications of MLID, and therefore, sequencing of this gene and MLID testing is warranted in patients with imprinting defects.

General discussion

Clinical and molecular overlap between imprinting disorders

As the symptoms of patients with imprinting disorders often overlap, a specific clinical diagnosis is not always possible. As listed in Table 1, molecular findings characteristic for TS14, PWS and BWS were detected in patients referred for SRS. Among patients with clinical BWSp, molecular findings characteristic for SRS and PHP were detectable, and this overlap was also reported for KOS14 [25, 34]. Furthermore, there are molecular and clinical overlaps between TS14 and PWS, and TNDM and BWS.

Up to now, the majority of patients with MLID exhibit symptoms specific for one of the known imprinting disorders (e.g. BWS and SRS), but there is a growing number of reports on cases with overlapping phenotypes and or epigenotypes or even apparently asymptomatic (e.g. [25]). Thus, it is conceivable that MLID patients currently escape detection as they do not show a distinctive MLID phenotype and are therefore not tested.

In summary, the reports of overlapping and even unexpected molecular findings in patients referred for imprinting disorder testing illustrate that only multi-locus tests enable the detection of this heterogeneous pattern of alterations.

Imprinted loci to be addressed by future multi-locus imprinting assays

Though more than 10 imprinting disorders have been identified so far, only eight of them are currently known to be associated with molecular disturbances affecting the respective DMR (TNDM, SRS, BWS, TS14, KOS14, AS, PWS, PHP). Therefore, the majority of (multi-locus) test approaches currently target these DMRs, but in the commercially available MLPA kit ME034 two additional DMRs are covered, the PEG3:TSS-DMR and the MEG3:TSS-DMR. PEG3:TSS-DMR is a germline DMR in 19q13.43 without an obvious clinical correlate, but it has been shown to be hypomethylated in the majority of ZFP57-associated TNDM imprinting defect patients [35], and also contributes to MLID imprinting signatures. The MEG3:TSS-DMR is a secondary (somatic) DMR which is subordinated to the MEG3/DLK1:IG-DMR in 14q32; the molecular features of this DMR make its methylation difficult to measure, but the MEG3:TSS-DMR acts as a reliable proxy, allowing the unambiguous detection of 14q32 alterations in routine diagnostics. The ZNF597:TSS-DMR in 16p13.3 is not targeted in routine testing, but there is increasing evidence suggesting that this DMR is suitable for diagnostic use.

Several studies indicate that further imprinted loci are affected by MLID, but their relevance is currently being discussed (for review: [36]). Thus, future multi-locus tests should comprise flexible formats, but for diagnostic application they should target only imprinted loci for which associations with clinical phenotypes have been established.

Multilocus Imprinting Disturbances (MLID) testing and its relevance

Multi-locus imprinting disturbances (MLID) affect an unknown subset of individuals with DNA methylation anomalies. While a multi-locus testing strategy is potentially warranted for many imprinting disorders, its implementation would inevitably result in increased detection of MLID. Current consensus guidelines do not recommend MLID testing because its clinical consequences remain uncertain, but MLID is increasingly reported with trans acting gene variants in SCMC encoding genes that carry inherent risks of recurrence as well as parental reproductive difficulties [11, 37–39] making a case for testing in families with multiple affected pregnancies [40]. Currently there is insufficient information to confidently establish counselling or management guidelines for MLID, but its intrinsic heterogeneity indicates that information can be gathered only with a concerted international effort.

New imprinting disorders?

With the increasing application of multi-locus tests for research or diagnostic purposes in cohorts of patients with imprinting disorders, maternal UPDs of chromosomes 6 and 16 have been identified in a growing number patients with intrauterine growth retardation and/or short stature.

In laboratories addressing the PLAGL1:alt-TSS-DMR in 6q24 in the patient cohorts, upd(6)mat is a rare but recurring finding, and an association with (intrauterine) growth retardation is meanwhile well established [19]. Thus, identification of upd(6)mat in a patient with a phenotype reminiscent for SRS can be regarded as molecularly diagnosed.

Since its first description in 1993 [41], upd(16)mat has been reported in numerous patients. Carriers of upd(16)mat exhibit a heterogeneous spectrum of features, and therefore, it has been suggested that cell lines with trisomy 16 had an impact on the phenotypic outcome [42]. The recent report on an isolated methylation defect at the ZNF597 locus [43] provides further evidence for the existence of a 16q13.3 associated imprinting disorder. Testing of the ZNF597:TSS-DMR is currently not performed systematically but should be considered in future multi-locus assays.

A third genetic constitution which needs future awareness is paternal UPD of chromosome 7 (upd(7)pat) which has been suggested to be associated with tall stature [44]. The application of multi-locus testing in overgrowth/BWS cohorts will further enlighten the relevance of this alteration.

Suggestions

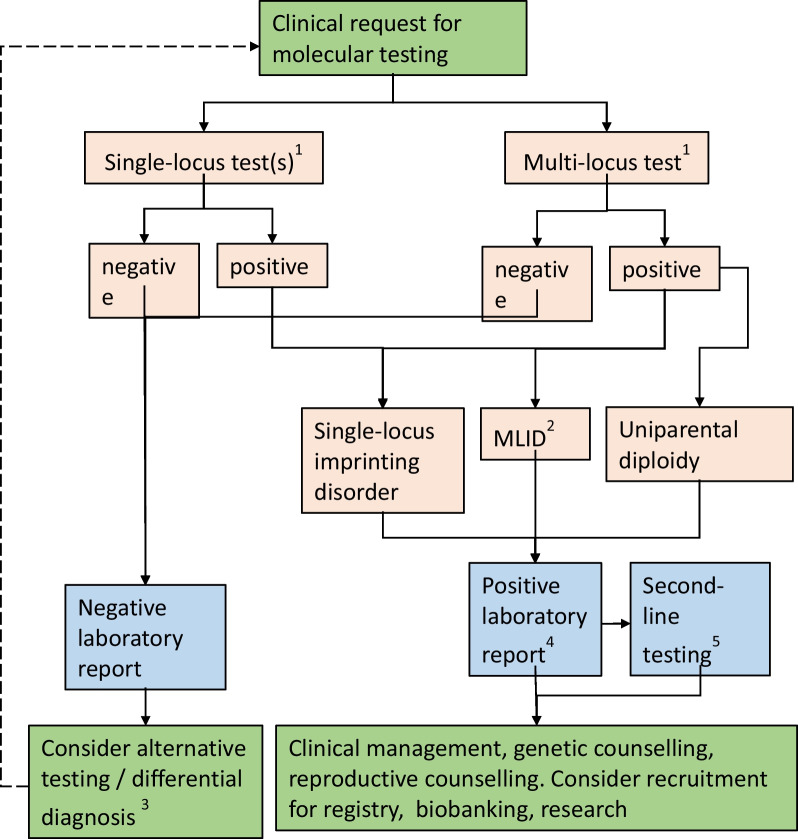

Based on comprehensive datasets from eleven laboratories, our survey shows the evolving nature of imprinting disorder diagnosis. We suggest the following modifications to diagnostic testing for imprinting disorders (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Suggested multi-locus testing algorithm for imprinting disorders. 1The decision on first-line test depends on the clinical phenotype of the patient, consensus guidelines and national regulations. For some disorders and phenotypes, single-locus testing might be preferred; for some clinical indications (e.g. relatively non-specific growth restriction, hypotonia or developmental problems or features characteristic of more than one imprinting disorder) multi-locus testing may be preferred. Reproductive and family history may also be considered. 2MLID testing should be considered in case of clinical features reminiscent for SRS, BWS, TNDM and PHP. 3Differential diagnosis or alternative testing may include NGS-based genomic medicine, microarray, testing of alternative tissues or additional epigenetic analysis, depending on the clinical features of the patient. 4Depending on the disorder, national regulations and clinical consensus guidelines, positive reports may also include recommendations for further action such as additional analyses to identify the underlying molecular cause (e.g. discrimination between UPD and ID, exclusion of a Robertsonian translocation in case of a UPD for PWS, AS, TS14, KOS14) to estimate the recurrence risk, clinical management and counselling. 5Second-line testing may include NGS-based genomic analysis, detection of cis acting SNV or CNV, detection of trans acting variants, or other analyses pursuant to relevant consensus guidelines or the molecular change detected

Development or adoption of a multi-locus imprinting test, capturing DNA methylation and relevant copy number analysis of imprinted loci on chromosomes 6, 7, 11, 14, 15, 16, 20. This could conveniently be compassed on one two-tube MS-MLPA kit, or in a novel test which should be validated in respect to a uniform and standardised coverage of all relevant DMRs and major molecular subtypes.

Multi-locus testing of all individuals referred for growth restricting imprinting disorder testing (i.e. for SRS, TS14). This would efficiently capture known imprinting disorders and MLID, after which SNP array or NGS (next generation sequencing) analysis could be targeted for individuals; (a) with unusual DNA methylation patterns, to seek uniparental diploidy or structural variants, (b) with MLID to investigate trans acting variants in maternal effect genes; (c) without a detected imprinting change to seek variants in genes involved in growth restriction.

Multi-locus testing for individuals with BWS due to upd(11)pat or IC2 LOM. This strategy has already been suggested [10] as it enables identification of paternal uniparental diploidy as the basis for a modified neoplasia surveillance. In patients with KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR LOM patients, it allows detection of MLID. In families where MLID is detected, genetic testing for pathogenic variants in maternal effect genes might be considered.

Multi-locus testing for individuals with TNDM caused by PLAGL1 LOM. This would identify MLID enabling genetic testing for either ZFP57, ZNF445 or variants in maternal effect genes.

Furthermore, we suggest that additional translational studies in a diagnostic setting would be very helpful to resolve several gaps in understanding of imprinting disorders and address unmet needs for counselling and management of affected individuals:

Multi-locus analysis for individuals negatively tested for TS14 and PWS might confirm evolving evidence for molecular and clinical overlaps between TS14 and PWS. In these patients, the clinical overlap should be assessed.

Qualitative study on the ethical acceptability and the significance of multi-locus testing for clinicians and families.

Comprehensive genetic, epigenetic and clinical profiling of individuals with MLID in an international cohort, to improve understanding and clinical management of this condition.

International and national patient registries for rare imprinting disorders and exchange of information, to estimate prevalence, determine clinical history and underpin improvements in diagnosis and management.

Further assessment of comprehensive [36] and genome-wide DNA methylation [45] testing for first-line diagnosis or MLID testing in imprinting disorders, including clinical utility, economic viability and ethical acceptability.

Outcomes

The authors of this study have consented to the following definitions and agreements in the context of multi-locus testing and MLID, as a precursor to future cooperative and international guidelines and research projects:

For the purposes of genomic medicine, MLID is defined as: imprinting defects at two or more of the ICs listed in Table 2. A conservative definition of MLID is preferable for use in clinical service, since it focuses on loci that are well studied and clinically relevant.

However, imprinting is not biologically restricted to clinically relevant ICs, and current research suggests an alternative, expanded definition: MLID comprises imprinting defects at (A) ≥ 1 clinically relevant loci and (B) ≥ 2 additional (germline) ICs. Further research is required to clarify exactly which ICs comprise group B and whether the expanded definition has diagnostic utility.

MLID is a spectrum disorder: its definition is epigenetic, not clinical, and affected individuals are clinically heterogeneous. However, the majority of patients are currently recognised because of a “primary presentation”—clinical features aligning closely with one of the specific imprinting disorders. Though this may reflect ascertainment bias, further studies of patient cohorts with phenotypes that are not currently associated with classical imprinting disorders will provide further insights into epigenotype–phenotype relationships in MLID.

The definition of MLID focuses on ICs rather than on secondary DMRs under their control. An example for MLID is loss of methylation (LOM) of both H19/IGF2:IG-DMR/IC1 and KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR/IC2 in 11p15.5 because they are independent germline ICs.

In principle, imprinting disturbance may be manifested as LOM / GOM in MLID. In practice, at present, LOM is observed in the majority of cases.

Perspectives

The precise identification of (new) genetic and epigenetic pathways offers the potential for new therapeutic regimes as the basis for a more directed and personalised treatment in IDs. A diagnosis may alter clinical management, for example of puberty in TS or cancer surveillance in BWS; or change counselling, e.g. when cis or trans acting genetic variants are identified. On a translational level, new diagnoses of rare disorders such as rare UPDs and MLID will clarify (epi)genotype–phenotype relationships and management.

In the future, methodological progress in methylation specific next and third generation sequencing techniques will allow to target genome-wide genomic alterations (SNVs and CNVs) as well as epigenetic signatures in the same assay (for future perspectives see also [46]). These assays will enable the integrated analyses of genomic and epigenetic data, and in combination with additional omic techniques, the causes of disturbed imprinting and their functional consequences will be determined. These single unified tests will avoid false negative results which are currently obtained by focusing on single loci, and will even make the detection of multiple (epi)genetic pathogenic variants with an impact on the phenotype of a patient possible.

Methods

Eleven diagnostic laboratories from seven countries (Table 1) contributed to this study, providing data from 16,364 patients referred for diagnostic testing for Silver–Russell syndrome (SRS), Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), Angelman syndrome (AS), Temple syndrome (TS14), Kagami–Ogata syndrome (KOS14), Pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP) and Transient Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus (TNDM).

The participating centres followed the international diagnosis guidelines when available [9, 10, 13, 14]. While the majority of participating institutions used disease-specific MS-MLPA assays as first-line tests, manufactured by MRC Holland (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) (Table 2): ME028 for PWS/AS, ME030 for BWS/SRS, ME031 for PHP, ME032 for TNDM, TS14, KOS14 and SRS (upd(7)mat), some used other test systems (such as MS pyrosequencing; allele-specific methylated multiplex real-time quantitative PCR (ASMM-RT qPCR)). The diagnostic testing was mainly based on peripheral blood samples; in single cases, buccal swab DNA was analysed.

Many laboratories used further methods (e.g. SNP array analysis, microsatellite analysis/short tandem repeat typing, Sanger sequencing) to confirm the positive findings and/or to further discriminate molecular subgroups. Some centres applied a multi-locus test, e.g. MS-MLPA (ME034), MS pyrosequencing or ASMM-RT qPCR to confirm positive results of first-line testing and/or to identify further molecular changes and MLID. Some laboratories used multi-locus testing routinely for all the referred individuals (Aachen/Germany; Madrid/Spain; Tokyo, Hamamatsu/Japan).

The clinical reasons for referral varied between centres, depending on national practice and (scientific) focus. In some centres/countries, patients with even discrete features of the respective imprinting disorders were referred for testing, while others had relatively strict criteria. Some (national) expert diagnostic centres performed a restricted range of testing for a specified subset of clinical presentations and/or disease loci.

The authors want to emphasise the use of the recently suggested nomenclature of DMRs based on the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) guidelines (Table 2)[47].

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ASMM-RT qPCR

Allele-specific methylated multiplex real-time quantitative PCR

- BWS

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome

- BWSp

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome spectrum

- CNV

Copy number variant

- DMR

Differentially methylated region

- GNAS

GNAS-NESP:TSS-DMR; GNAS-XL:Ex1-DMR;GNAS A/B:TSS-DMR; GNAS-AS1:TSS-DMR (20q13)

- GOM

Gain of methylation

- IC

Imprinting centre

- ID

Imprinting defect

- iPPSD

Inactivating PTH/PTHrP signalling disorder

- KOS14

Kagami–Ogata syndrome

- LOM

Loss of methylation

- MLID

Multi-locus imprinting disturbance

- MLPA

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- MS

Methylation-specific

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- PHP

Pseudohypoparathyroidism

- PNGR

Post-natal growth retardation

- SCMC

Subcortical maternal complex

- SGA

Small for gestational age

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SNV

Single-nucleotide variant

- SRS

Silver–Russell syndrome

- TNDM

Transient neonatal diabetes mellitus

- TS14

Temple syndrome

- UPD

Uniparental disomy

Author contributions

DJM and TE compiled the data. All coauthors contributed data and checked the compiled dataset. All authors commented to the draft, and DJM and TE prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors significantly contributed their expertise and additional information from own published data. All the authors read and approved the paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors are supported by the following grants: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to TE: EG 115/13-1). Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIIII) of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain) (to GPdN and AP: PI20/00950), co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund. 2019 research unit grant from ESPE (to GdPN). Instituto de Salud Carlos III of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain) (to PL: grants # FIS 20/01053, IMPACT project 20/IMP00009). Italian Ministry of Health RC 08C724, 08C502 (to SR and PT). Wellcome Trust (WT098395/Z/12/Z, to EdF). IKT is supported in part by the Southampton NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, UK (2017-2022, IS-BRC-1215-20004). ERM thanks the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre for research support. The University of Cambridge has received salary support for ERM from the NHS in the East of England through the Clinical Academic Reserve. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS or Department of Health (ERM and IKT). EDF is a Diabetes UK RD Lawrence Fellow (19/005971). MK and TO are funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (20ek0109373h0003, 22ek0109587).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty of the RWTH Aachen University (EK303-18).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Monk D, Mackay DJG, Eggermann T, Maher ER, Riccio A. Genomic imprinting disorders: lessons on how genome, epigenome and environment interact. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(4):235–248. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soellner L, Begemann M, Mackay DJ, Gronskov K, Tumer Z, Maher ER, et al. Recent advances in imprinting disorders. Clin Genet. 2017;91(1):3–13. doi: 10.1111/cge.12827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yakoreva M, Kahre T, Zordania R, Reinson K, Teek R, Tillmann V, et al. A retrospective analysis of the prevalence of imprinting disorders in Estonia from 1998 to 2016. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27(11):1649–1658. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0446-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggermann T, Davies JH, Tauber M, van den Akker E, Hokken-Koelega A, Johansson G, et al. Growth restriction and genomic imprinting-overlapping phenotypes support the concept of an imprinting network. Genes (Basel) 2021;12(4):585. doi: 10.3390/genes12040585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inbar-Feigenberg M, Choufani S, Cytrynbaum C, Chen YA, Steele L, Shuman C, et al. Mosaicism for genome-wide paternal uniparental disomy with features of multiple imprinting disorders: diagnostic and management issues. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masunaga Y, Kagami M, Kato F, Usui T, Yonemoto T, Mishima K, et al. Parthenogenetic mosaicism: generation via second polar body retention and unmasking of a likely causative PER2 variant for hypersomnia. Clin Epigenet. 2021;13(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01062-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Delgado M, Riccio A, Eggermann T, Maher ER, Lapunzina P, Mackay D, et al. Causes and consequences of multi-locus imprinting disturbances in humans. Trends Genet. 2016;32(7):444–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalish JM, Conlin LK, Bhatti TR, Dubbs HA, Harris MC, Izumi K, et al. Clinical features of three girls with mosaic genome-wide paternal uniparental isodisomy. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(8):1929–1939. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakeling EL, Brioude F, Lokulo-Sodipe O, O'Connell SM, Salem J, Bliek J, et al. Diagnosis and management of Silver–Russell syndrome: first international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(2):105–124. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brioude F, Kalish JM, Mussa A, Foster AC, Bliek J, Ferrero GB, et al. Expert consensus document: clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: an international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):229–249. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani G, Bastepe M, Monk D, de Sanctis L, Thiele S, Ahmed SF, et al. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of pseudohypoparathyroidism and related disorders: an updated practical tool for physicians and patients. Horm Res Paediatr. 2020;93(3):182–196. doi: 10.1159/000508985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monk D, Sanchez-Delgado M, Fisher R. NLRPs, the subcortical maternal complex and genomic imprinting. Reproduction. 2017;154(6):R161–R170. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantovani G, Bastepe M, Monk D, de Sanctis L, Thiele S, Usardi A, et al. Diagnosis and management of pseudohypoparathyroidism and related disorders: first international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(8):476–500. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beygo J, Buiting K, Ramsden SC, Ellis R, Clayton-Smith J, Kanber D. Update of the EMQN/ACGS best practice guidelines for molecular analysis of Prader–Willi and Angelman syndromes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27(9):1326–1340. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0435-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackay DJG, Bliek J, Lombardi MP, Russo S, Calzari L, Guzzetti S, et al. Discrepant molecular and clinical diagnoses in Beckwith–Wiedemann and Silver–Russell syndromes. Genetics Research. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Brioude F, Kalish JM, Mussa A, Foster AC, Bliek J, Ferrero GB, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: an international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):229–249. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalish JM, Biesecker LG, Brioude F, Deardorff MA, Di Cesare-Merlone A, Druley T, et al. Nomenclature and definition in asymmetric regional body overgrowth. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(7):1735–1738. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kagami M, Nagasaki K, Kosaki R, Horikawa R, Naiki Y, Saitoh S, et al. Temple syndrome: comprehensive molecular and clinical findings in 32 Japanese patients. Genet Med. 2017;19(12):1356–1366. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggermann T, Oehl-Jaschkowitz B, Dicks S, Thomas W, Kanber D, Albrecht B, et al. The maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 6 (upd(6)mat) "phenotype": result of placental trisomy 6 mosaicism? Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5(6):668–677. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geoffron S, Habib WA, Chantot-Bastaraud S, Harbison M, Salem J, Brioude F, et al. Diagnosis of silver-russell syndrome in patients with chromosome 14q32.2 imprinted region disruption: phenotypic and molecular analysis. Hormone Res Paediatr. 2018;90(Supplement 1):121–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lande A, Kroken M, Rabben K, Retterstol L. Temple syndrome as a differential diagnosis to Prader–Willi syndrome: identifying three new patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(1):175–180. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eggermann T, Bruck J, Knopp C, Fekete G, Kratz C, Tasic V, et al. Need for a precise molecular diagnosis in Beckwith–Wiedemann and Silver–Russell syndrome: what has to be considered and why it is important. J Mol Med (Berl) 2020;98(10):1447–1455. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-01966-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postema FAM, Bliek J, van Noesel CJM, van Zutven LJCM, Oosterwijk JC, Hopman SMJ, et al. Multiple tumors due to mosaic genome-wide paternal uniparental disomy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(6):e27715. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheppard SE, Lalonde E, Adzick NS, Beck AE, Bhatti T, De Leon DD, et al. Androgenetic chimerism as an etiology for Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: diagnosis and management. Genet Med: Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2019;21(11):2644–2649. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0551-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sano S, Matsubara K, Nagasaki K, Kikuchi T, Nakabayashi K, Hata K, et al. Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib in a patient with multilocus imprinting disturbance: a female-dominant phenomenon? J Hum Genet. 2016;61(8):765–769. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buiting K, Cassidy SB, Driscoll DJ, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Kanber D, Tauber M, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Prader–Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(9):1153–1153. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buiting K, Clayton-Smith J, Driscoll DJ, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Kanber D, Schwinger E, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Angelman Syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(2):3–3. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geoffron S, Abi Habib W, Chantot-Bastaraud S, Dubern B, Steunou V, Azzi S, et al. Chromosome 14q32.2 imprinted region disruption as an alternative molecular diagnosis of Silver–Russell syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(7):2436–2446. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruck J, Begemann M, Dey D, Elbracht M, Eggermann T. Molecular characterization of temple syndrome families with 14q32 epimutations. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63(12):104077. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2020.104077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kagami M, Kurosawa K, Miyazaki O, Ishino F, Matsuoka K, Ogata T. Comprehensive clinical studies in 34 patients with molecularly defined UPD(14)pat and related conditions (Kagami–Ogata syndrome) Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(11):1488–1498. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogata T, Kagami M. Kagami–Ogata syndrome: a clinically recognizable upd (14)pat and related disorder affecting the chromosome 14q32.2 imprinted region. J Human Genet. 2016;61(2):87–94. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elli FM, Linglart A, Garin I, de Sanctis L, Bordogna P, Grybek V, et al. The prevalence of GNAS deficiency-related diseases in a large cohort of patients characterized by the EuroPHP network. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(10):3657–3668. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Docherty LE, Kabwama S, Lehmann A, Hawke E, Harrison L, Flanagan SE, et al. Clinical presentation of 6q24 transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (6q24 TNDM) and genotype-phenotype correlation in an international cohort of patients. Diabetologia. 2013;56(4):758–762. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2832-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altmann J, Horn D, Korinth D, Eggermann T, Henrich W, Verlohren S. Kagami–Ogata syndrome: an important differential diagnosis to Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Clin Ultrasound. 2020;48(4):240–243. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackay DJ, Callaway JL, Marks SM, White HE, Acerini CL, Boonen SE, et al. Hypomethylation of multiple imprinted loci in individuals with transient neonatal diabetes is associated with mutations in ZFP57. Nat Genet. 2008;40(8):949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochoa E, Lee S, Lan-Leung B, Dias RP, Ong KK, Radley JA, et al. ImprintSeq, a novel tool to interrogate DNA methylation at human imprinted regions and diagnose multilocus imprinting disturbance. Genet Med. 2021;24(2):463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Docherty LE, Rezwan FI, Poole RL, Turner CLS, Kivuva E, Maher ER, et al. Mutations in NLRP5 are associated with reproductive wastage and multilocus imprinting disorders in humans. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8086. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Begemann M, Rezwan FI, Beygo J, Docherty LE, Kolarova J, Schroeder C, et al. Maternal variants in NLRP and other maternal effect proteins are associated with multilocus imprinting disturbance in offspring. J Med Genet. 2018;55(7):497–504. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eggermann T, Kadgien G, Begemann M, Elbracht M. Biallelic PADI6 variants cause multilocus imprinting disturbances and miscarriages in the same family. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021;29(4):575–580. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-00762-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elbracht M, Mackay D, Begemann M, Kagan KO, Eggermann T. Disturbed genomic imprinting and its relevance for human reproduction: causes and clinical consequences. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26(2):197–213. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalousek DK, Langlois S, Barrett I, Yam I, Wilson DR, Howard-Peebles PN, et al. Uniparental disomy for chromosome 16 in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52(1):8–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheuvens R, Begemann M, Soellner L, Meschede D, Raabe-Meyer G, Elbracht M, et al. Maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 16 [upd(16)mat]: clinical features are rather caused by (hidden) trisomy 16 mosaicism than by upd(16)mat itself. Clin Genet. 2017;92(1):45–51. doi: 10.1111/cge.12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamazawa K, Inoue T, Sakemi Y, Nakashima T, Yamashita H, Khono K, et al. Loss of imprinting of the human-specific imprinted gene ZNF597 causes prenatal growth retardation and dysmorphic features: implications for phenotypic overlap with Silver–Russell syndrome. J Med Genet. 2020;58(6):427–432. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakamura A, Muroya K, Ogata-Kawata H, Nakabayashi K, Matsubara K, Ogata T, et al. A case of paternal uniparental isodisomy for chromosome 7 associated with overgrowth. J Med Genet. 2018;55(8):567–570. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadikovic B, Levy MA, Kerkhof J, Aref-Eshghi E, Schenkel L, Stuart A, et al. Clinical epigenomics: genome-wide DNA methylation analysis for the diagnosis of Mendelian disorders. Genet Med. 2021;23(6):1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-01096-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Kaay DCM, Rochtus A, Binder G, Kurth I, Prawitt D, Netchine I, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing approaches as the basis for personalized management of growth disturbances: current status and perspectives. Endocr Connect. 2022;11(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Monk D, Morales J, den Dunnen JT, Russo S, Court F, Prawitt D, et al. Recommendations for a nomenclature system for reporting methylation aberrations in imprinted domains. Epigenetics. 2018;13(2):117–121. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1264561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beygo J, Elbracht M, de Groot K, Begemann M, Kanber D, Platzer K, et al. Novel deletions affecting the MEG3-DMR provide further evidence for a hierarchical regulation of imprinting in 14q32. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(2):180–188. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.