Abstract

Objectives

The Ethiopian government had planned to vaccinate the total population and started to deliver the COVID-19 vaccine but, there is limited evidence about vaccine acceptance among pregnant women. Thus, this study aimed to assess COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated factors among pregnant women attending an antenatal care unit clinic in Eastern Ethiopia.

Study design

A facility-based cross-sectional study.

Methods

A study was conducted from June 01 to 30/2021 among systematically selected pregnant women. Data were collected using a pre-tested structured questionnaire, which was adapted from previous studies, through a face-to-face interview. Predictors were assessed using a multivariable logistic regression model and reported using an adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI. Statistical significance was declared at p-value less than 0.05.

Results

In this study, data from 645 pregnant women were used in the analysis. Overall, 62.2% of pregnant women were willing to be vaccinated if the vaccine is approved by the relevant authority. Fear of side effects (62.04%), a lack of information (54.29%), and uncertainty about the vaccine's safety and efficacy (25%) were the most common reasons for refusal to take the COVID-19 vaccine. The odds of unwillingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women were increased significantly among mothers who were able to read and write [AOR = 2.9, 95% CI: (1.16, 7.23)], attain 9-12 grade level [AOR = 4.2, 95% CI: (2.1, 8.5)], lack information [AOR = 2.2, 95% CI: (1.41, 3.57)], and having a history of chronic diseases [AOR = 2.52, 95% CI: (1.34, 4.7)].

Conclusion

Less than two-thirds of pregnant women were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. Extensive public health information dissemination aimed at women with lower educational backgrounds and a history of chronic disease could be critical.

Keywords: COVID- 19 vaccines, Vaccine hesitancy, Pregnancy, Vaccine acceptance, COVID-19

Abbreviations: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease in the year 2019; EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey; HCW, Health Care Workers; USAID, United States Agency for International Development; WHO, World Health Organization

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is causing public health challenges including massive loss of life and poor health outcomes worldwide [1,2]. Although pregnant women are not at increased risk of COVID-19 infection [3], they are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 diseases [4]. COVID-19 increases the risk of delivering a preterm or stillbirth. Moreover, pregnant women infected with COVID-19 had a high rate of cesarean delivery and admission to the ICU [5,6].

To prevent the infection and its consequences, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended the COVID-19 vaccine for pregnant women [7,8]. The use of vaccines to protect pregnant women and their newborns from infectious diseases is a standard part of obstetric practice [8]. When pregnant women are immunized, their newborns gain immunity via trans-placental passage of protective antibodies into the fetal/neonatal circulation and through breast milk [9,10].

After the COVID-19 vaccination program was launched, reproductive-age women were hesitant to accept the vaccine, with the claim of fertility issues [11]. According to a survey in 16 different countries the acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women was 52% [10] whereas in southern Ethiopia 70.7% of pregnant women were willing to accept COVID-19 [12]. Vaccine acceptance during pregnancy is hampered by several factors, including vaccine safety, perceived benefits, a lack of recommendations from healthcare providers, and a lack of trust in healthcare providers and the pharmaceutical industry [13]. Furthermore, educational status, residence, vaccine perception, pregnancy trimester, and type of profession all influence uptake [10,14]. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the impact of media and social media on vaccine uptake, with different findings indicating different directions of this impact, as media platforms may accelerate the infodemic during public health emergencies to the point where healthy decisions cannot be made [5,6].

Even though vaccines are effective interventions to reduce the burden of COVID-19 disease; public vaccine hesitancy is a pressing problem to deliver the vaccine [15,16]. So, evidence-based and tailored information on COVID-19 vaccines should be provided to pregnant women to avoid unfounded concerns about the vaccines and to support population-wide shared decision-making. The government of Ethiopia had planned to vaccinate 20% of the total population and started to deliver the COVID-19 vaccine [17] but, there is limited evidence about the acceptance of the vaccine, particularly among pregnant women. As a result, it is critical to understand the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and reasons for refusal among pregnant women, which will aid in the dissemination and administration of the COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available, as well as the development of a strategy to overcome vaccine hesitancy. Thus, this study aimed to assess the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine and its associated factors among pregnant women attending an antenatal care unit in Eastern Ethiopia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting and period

A study was conducted at public hospitals of Dire Dawa city administration, East and West Hararghe zones of Oromia regional state from June 01 to 30, 2021. Based on the 2007 Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), Dire Dawa is found 515 km from Addis Ababa to the East; has a total population of 395,000 of which females account for 51.6% [18], and currently there are two public hospitals in this city; Dilchora referral hospital and Sabian Primary hospital. The center of East Hararghe is Harar town which has a total population of 3,587,042 [18], and there are five public hospitals in the east Hararghe zone, namely Bisidimo, Deder, Garamuleta, Chelenko, and Haramaya hospital. The center of west Harerghe is Chiro town, which is 326 km far from Addis Ababa to the east. Currently, there are 2,467,364 total population [18]. There are four public Hospitals (Chiro, Geelmso, Asebot, and Hirna hospital).

2.2. Study design

A facility-based cross-sectional study design was used.

2.3. Population and eligibility criteria

The study included pregnant women who received antenatal care in public hospitals of Dire Dawa city, east Hararghe, and west Hararghe zones. Pregnant women who visited public hospitals in the study area but were unable to communicate due to a serious illness during the data collection period were excluded from this study.

2.4. Sample size and sampling procedure

The double population proportion formula was used to determine the sample size which was calculated for some of the associated factors obtained from different literatures by using computer-based Epi info 7 software Stat Cal with the assumptions of 95% confidence level, power = 80%, proportion of exposed to non-exposed 1:1, 10% for non-response rate, and the proportion of nonexposed (no formal education) 18.4% and exposed (had secondary and above educational level) 10.6% [12]. Then, the final sample was 645.

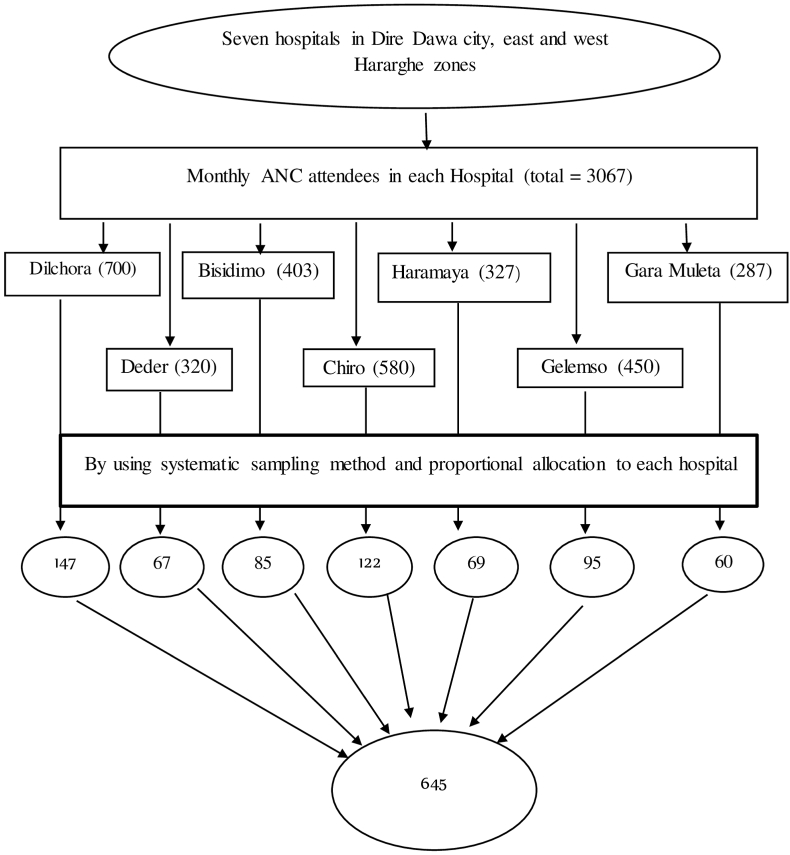

Although there are 11 public hospitals in the study area, four hospitals (Sabian from Dire Dawa, Chelenko from east Hararghe, and Asebot and Hirna from west Hararghe zones) were excluded because they did not provide ANC services and instead served as corona centers (serving COVID-19 ill patients) during the data collection period. The study included seven public hospitals in the study area, namely Dilchora, Bisidimo, Haramaya, Garamuleta, Deder, Chiro, and Gelemso. Based on the client flow one month before the survey, the required sample from each public hospital was allocated proportionally to the size of the client flow. The study subjects were selected using a systematic random sampling technique with every other interval (K N/n) from each hospital's registration book until the predetermined sample size was reached. The first eligible study participant was selected through a lottery system (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sampling procedure for the assessment of acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in eastern Ethiopia, 2021.

2.5. Data collection methods

Data collection was undertaken using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was adapted from previous literatures [10,12,19,20]. The questionnaire was first prepared in the English language and then translated into Amharic and Afan Oromo languages, which are used for communication in the local community, and back to English by different language experts to check the consistency of the data. It contains information about socio-demographic characteristics, awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine, health beliefs regarding COVID-19 disease and vaccine, and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. The data were collected by ten trained graduating class nursing and midwifery students and supervised by four BSc holder nurses who were fluent in the local languages “Afan Oromo and Amharic”. A brief introductory orientation was given to the study participants by data collectors about the purpose of the study and the importance of their involvement, and then pregnant mothers were interviewed face-to-face using structured and pre-tested questionnaire.

2.6. Measurements and operational definitions

Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine: was measured using “Yes” or “No” questions. Pregnant mothers were asked “Are you willing to be vaccinated if approved by the concerned agency” pregnant mothers who reply “yes” were given a score of 1, while those who replay “No” response was given a score of 0. As a result, participants who scored 1 were deemed willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine, while those who scored 0 were deemed unwilling to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.

Vaccine hesitancy refers to delaying or refusing vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services [15].

Complacency refers to the low perceived risk of vaccine-preventable diseases, leading to an assumption that vaccines are not needed [21].

Awareness of COVID-19 Vaccine: A mean score (answering strongly agree or agree) will be described as having good knowledge, and a score below the mean will be considered poor knowledge (answering strongly disagree, disagree, or neutral) [16].

2.7. Data quality control

The questionnaire was initially prepared in English and then translated into the local languages by a language expert (Afan Oromo and Amharic language). Then, it was translated back into an English version to ensure its consistency. The data collectors and field supervisors received training on the data collection tool and procedures. Before the actual data collection, the pretest was conducted among 5% of the participants in similar settings. The investigators and experienced field research supervisors provided regular supervision. The data were collected using Kobo Collect (a free toolkit for collecting and managing data) version 2021.3.4.

2.8. Data processing and analysis

The data were coded, cleaned, edited, and then analyzed by SPSS window version 22 software. Descriptive statistical analyses such as simple frequency, mean, and standard deviation were used to describe the characteristics of participants such as socio-demographic characteristics, awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine, and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. The information was presented using frequencies and tables. The primary outcome variable of the study was COVID-19 vaccine acceptance which was assessed by asking the question “Are you willing to be vaccinated if approved by a concerned agency?” then the response was dichotomized as “Yes” coded as ‘1' (willing to be vaccinated COVID-19) or “No” coded as ‘0' (not willing to be vaccinated). Collinearity was checked using VIF and tolerance and the goodness of fit was tested by Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic and Omnibus tests. Bi-variable and multivariable analysis was done to see the association between each independent variable and the outcome variable by using binary logistic regression. All variables with P ≤ 0.25 in the bi-variable analysis were candidates for the final model of multivariable analysis. The direction and strength of statistical association were measured by odds ratio with 95% CI. Adjusted odds ratio along with 95% CI was estimated to identify predictors for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance by using multivariable analysis in the binary logistic regression. Finally, statistical significance was declared at a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

A total of 645 participants were included in the study. Among the total participants, 335 (51.94%) of them were between the age of 19–28 years. The mean (±SD) age of the respondents was 28.92 ± 6.7 years. Regarding the occupation of study participants, 54 (9.66%) were government employees whereas 200 (35.78%) were private employees. Furthermore, about 436(67.60%) pregnant women had no health insurance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women in the health institutions of eastern Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 645).

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency(n = 645) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Under 18 | 15 | 2.33 |

| 19–28 | 335 | 51.94 | |

| 29–38 | 238 | 36.90 | |

| Above 39 | 57 | 8.84 | |

| Residency | Urban | 364 | 56.43 |

| Rural | 281 | 43.57 | |

| Marital status | Single | 42 | 6.51 |

| Married | 544 | 84.34 | |

| Divorced | 31 | 4.81 | |

| Widowed | 17 | 2.64 | |

| Separated | 11 | 1.71 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 462 | 71.63 |

| Amhara | 130 | 20.16 | |

| Somali | 15 | 2.33 | |

| aOthers | 38 | 5.89 | |

| Educational status | No formal education | 107 | 16.59 |

| Read and write | 61 | 9.46 | |

| Primary education (grade 1–8) | 86 | 13.33 | |

| Secondary education (grade 9–12) | 117 | 18.14 | |

| Collage and above | 274 | 42.48 | |

| Occupational status | Housewife | 195 | 30.23 |

| Farmer | 154 | 23.88 | |

| Private employee | 222 | 34.42 | |

| Government employee | 74 | 11.47 | |

| Family size | 1–2 | 148 | 22.95 |

| 3–5 | 330 | 51.16 | |

| ≥6 | 167 | 25.89 | |

| Monthly income | <5000 ETB | 402 | 62.33 |

| 5000-9999 ETB | 207 | 32.09 | |

| ≥10000 ETB | 36 | 5.58 | |

| Health insurance | Yes | 209 | 32.40 |

| No | 436 | 67.60 |

Others: Sidama, Tigre; ETB: Ethiopian Total Birr.

3.2. Awareness of pregnant women regarding the COVID-19 vaccine and their willingness

More than three-quarters of the participants (77.67%) had heard about the COVID-19 vaccination. Approximately 400 (62.2%) of the total (645) pregnant women were willing to be vaccinated if the vaccine was approved by the relevant agency. Fear of side effects 152 (62.04%) and a lack of information about the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy 133 (54.29%) were the most common reasons for refusal to take the COVID-19 vaccine (Table 2).

Table 2.

Awareness of pregnant women regarding COVID-19 Vaccine and willingness to be vaccinated, 2021 (N = 645).

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency(n = 645) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heard about COVID-19 vaccine | Yes | 501 | 77.67 | |

| No | 144 | 22.33 | ||

| Source of information (N = 501) | Health professionals | 50 | 9.98 | |

| Friends | 80 | 15.97 | ||

| Mas-medias | 371 | 74.05 | ||

| Willingness to be vaccinated if approved by the concerned agency | Yes | 400 | 62.02 | |

| No | 245 | 37.98 | ||

| Reasons for unwillingness to take COVID-19 vaccine (n=245) | ||||

| Fear of side effects | Yes | 152 | 62.04 | |

| No | 93 | 37.96 | ||

| Doubt about the safety and efficacy of Vaccine | Yes | 62 | 25.31 | |

| No | 183 | 74.69 | ||

| Unreliable due to short time of development | Yes | 34 | 13.88 | |

| No | 211 | 86.12 | ||

| Have no enough information | Yes | 133 | 54.29 | |

| No | 112 | 45.71 | ||

| The vaccine will cause COVID 19 | Yes | 7 | 2.86 | |

| No | 238 | 97.14 | ||

| No vaccine is required for COVID 19 | Yes | 13 | 5.31 | |

| No | 232 | 94.69 | ||

| Health status of the respondents | ||||

| Perceived health status | Very good | 410 | 63.57 | |

| Good | 201 | 31.16 | ||

| Fair | 25 | 3.88 | ||

| Poor | 6 | 0.93 | ||

| Very poor | 3 | 0.47 | ||

| History of COVID 19 | Yes | 41 | 6.36 | |

| No | 604 | 93.64 | ||

| Chronic diseases like cancer, DM, CVD | Yes | 60 | 9.30 | |

| No | 585 | 90.70 | ||

| Family members aged above 64 | Yes | 143 | 22.17 | |

| No | 502 | 77.83 | ||

| Family history of chronic diseases | Yes | 97 | 15.04 | |

| No | 548 | 84.96 | ||

DM: Diabetes Mellitus, CVD: Cardiovascular diseases.

3.3. Health beliefs regarding COVID-19 and vaccine

Regarding the belief of participants in COVID-19, 379 (58.7%) participants have a fear of getting COVID-19 in the next few months. Similarly, three-fourths of 508 (78.77%) have a fear of complications from COVID-19. Likewise, regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, 510 (79.15) participants agreed as vaccination is good as it makes them less worried about COVID-19, and 450 (69.8%) were worried about the side effects of the vaccine (Table 3).

Table 3.

Health beliefs regarding COVID-19 disease and vaccine among pregnant women in eastern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Characteristics (n = 645). | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chance of getting COVID-19 in the next few months | 309 (47.9) | 147(22.8) | 189(29.3) |

| Getting COVID-19 is currently possible for me | 343 (53.2) | 107 (16.59) | 195 (30.2) |

| Worrying about the likelihood of getting COVID-19 | 379 (58.7) | 121(18.8) | 145 (22.5) |

| Complications from COVID-19 are serious | 508 (78.77) | 116 (18.0) | 21 (3.3) |

| I will be very sick if I get COVID-19 | 412 (63.8) | 184 (28.5) | 49 (7.6) |

| I am afraid of getting COVID-19 | 422 (65.4) | 75 (11.6) | 148 (22.9) |

| Vaccination is good as it makes me less worried about COVID-19 | 510 (79.1) | 56 (8.7) | 79(13.3) |

| Worrying about side effects of Vaccine | 450 (69.8) | 155 (24.1) | 40 (6.2) |

| Concern about the efficacy of the vaccine | 375 (58.2) | 210 (32.6) | 60 (9.3) |

| Shortcuts are taken in Vaccine development | 300 (46.5) | 283 (43.9) | 62 (9.6) |

| Development too rushed to test safety | 367 (56.9) | 177 (27.4) | 101 (15.7) |

| Vaccination would interfere with my usual activities | 265 (41.1) | 238 (36.9) | 142 (22.0) |

| I will only take the vaccine if adequate information is given | 544 (84.4) | 62 (9.6) | 39 (6.1) |

| I will only take the vaccine if the vaccine is taken by many in the public | 438 (67.9) | 85 (13.2) | 122 (18.9) |

3.4. Factors associated with willingness to be vaccinated among pregnant women

In bi-variable analysis, educational statuses, lack of information exposure, having a history of chronic disease, and having a history of COVID-19 were significantly associated with willingness to be vaccinated. But, in the multivariable logistic regression, educational status, information exposure regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, and history of chronic diseases were significantly associated with willingness to be vaccinated.

During multivariable logistic analysis, educational status was significantly associated with willingness to be vaccinated. Those pregnant women who were able to read and write and completed grades 9–12 were 2.9 and 4.2 times less likely to be vaccinated compared to those pregnant women who completed college and above education level [AOR = 2.9, 95% CI: (1.16, 7.23)] and [AOR = 4.2, 95% CI: (2.1, 8.5)] respectively.

Those pregnant women who don't have information regarding the COVID-19 vaccine were about 2.2 times more likely to be unwilling to be vaccinated compared to those pregnant women who had information exposure [AOR = 2.2, 95% CI: (1.41, 3.57)]. Furthermore, the odds of unwillingness to be vaccinated were 2.52 times higher among pregnant women who had a history of chronic diseases compared to their counterparts [AOR = 2.52, 95% CI: (1.34, 4.7)] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bi-variable and multi-variable analysis to identify factors associated with acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women in eastern Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 645).

| Characteristics | Categories | Willingness to accept COVID -19 vaccine |

COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not willing | Willing | ||||

| Residency | Urban | 227 (35.2) | 137 (21.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 173 (26.8) | 108 (16.7) | 1.03(0.75,1.42) | 0.77(0.5,1.25) | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 77 (11.9) | 118 (18.3) | 0.77(0.41, 1.43) | 0.98(0.5,1.93) |

| Farmer | 72 (11.2) | 82 (12.7) | 1.01(0.57, 2.03) | 1.7(0.75, 3.99) | |

| Private employee | 78 (12.1) | 144 (22.3) | 0.63(0.34, 1.16) | 2.1(0.76, 5.65) | |

| Government employee | 34 (5.3) | 40 (6.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Educational status | No formal education | 42 (6.5) | 65 (10.1) | 1.5(0.93, 2.36) | 2.3(0.87, 5.9) |

| Read and write | 28 (4.3) | 33 (5.1) | 1.95(1.11, 3.4) * | 2.9(1.16, 7.23) * | |

| 1-8 grade | 37 (5.7) | 49 (7.6) | 1.74(1.1, 2.86) * | 0.71(0.71, 3.85) | |

| 9-12 grade | 55 (8.5) | 62 (9.6) | 2.04(1.31, 3.18) * | 4.2(2.1, 8.5) * | |

| Collage and above | 83 (12.9) | 191 (29.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| COVID-19 vaccine information exposure | Yes | 334 (51.8) | 167 (25.9) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 66 (10.2) | 78 (12.1) | 2.36(1.6, 3.44) ** | 2.2(1.41, 3.57) * | |

| History of chronic diseases | Yes | 48 (7.4) | 17 (2.6) | 1.82(1.03,3.25) * | 2.52(1.34, 4.7) * |

| No | 352 (54.6) | 228 (35.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| History of COVID-19 diseases | Yes | 32 (5.0) | 9 (1.4) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 368 (57.1) | 236 (36.6) | 2.28(1.07, 4.8) * | 0.63(0.27, 1.5) | |

| Income | <5000 ETB | 164 (25.4) | 238 (36.8) | 1.4(0.67, 2.83) | 1.33(0.60,2.9) |

| 5000-9999 ETB | 69 (10.7) | 138 (21.4) | 1.01(0.47, 2.1) | 0.81(0.37, 1.8) | |

| ≥10000 ETB | 12 (1.9) | 24 (3.7) | 1 | 1 | |

Key: * statistically significant at p-value <0.05, ** statistically significant at p-value <0.01, ETB: Ethiopian birr.

4. Discussion

Covid-19 vaccine hesitation and mistrust are major concerns globally, especially in low-income countries which have limited access and distribution [22]. Ethiopia planned to vaccinate 20% of the population [17], thus identifying pregnant women's willingness to be vaccinated, and factors hindering willingness to vaccination could help to tackle the factors in advance and improve COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. This study revealed that three-fourths of the participants heard about COVID-19 vaccination. Pregnant women were commonly unwilling to take the COVID-19 vaccine due to fear of side effects (62%), belief that the vaccine was unreliable due to short development time (13%), lack of long-term safety data in pregnancy on the fetus/mother (25%), belief that no vaccine is required for COVID-19 (5%), and belief that vaccine will cause COVID-19 infection (2%). This suggests that, before administering COVID-19 to pregnant women, policymakers, healthcare workers, and health extension workers should collaborate to promote the COVID-19 vaccine's safety and effectiveness, thereby increasing vaccine acceptance [12].

According to the findings of this study, 62.2% of pregnant women were willing to be vaccinated if the vaccine is approved by the appropriate agency. This may result in Ethiopia failing to meet its national goal of vaccinating 20% of the total population by the end of March 2022 [17]. The magnitude of willingness to be vaccinated in this study was in line with prior studies from Finland (64%) [23], Thailand (61%) [24], a Multinational study (61%) [19], and Ethiopia (62%) [20]. But higher than studies conducted in Ankara, Turkey (37%), surveys of 16 countries (52%), and southwest Ethiopia (31%) [10,14,25]. This could be due to differences in data collection methods, for instance, the 16-country survey collected data through an online system in which study participants were limited to those who had access to technology and resources, resulting in an overall overestimation of acceptance, a larger sample size used in this study (300 and 412 in Turkey and Ethiopia, respectively), and different timing of study execution and different stage of the pandemic Furthermore, as time passes, more data emerges, and women are more at ease with COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. The finding on the willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine in this study is also lower than studies conducted in India (90%) [26], China (77%) [27], and Ethiopia (71%) [12]. This disparity could be attributed to differences in access to healthcare services, awareness of the seriousness of COVID-19, and study population differences. When the COVID-19 vaccine was available for pregnant women in Ethiopia, the findings of this study highlighted that willingness to be vaccinated is still valuable to be noted. The likelihood of willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly associated with educational status, information exposure, and having a history of chronic diseases. Educated pregnant mothers were more likely to be willing to be vaccinated. The role of maternal education as an important predictor of willingness to COVID-19 vaccine acceptance has also been reported by other studies [12,19]. This could be explained by the fact that more educated mothers have better access to COVID-19 vaccine information and are also able to realize the benefits and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Those pregnant women who have information regarding the COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to be willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. This finding was supported by previous studies [26,27]. This might be elucidated as those pregnant mothers who had better information about the COVID-19 vaccine might understand the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so they will be willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine to curve the effect of the pandemic. The finding from this study also strengthens as 6% of respondents agree to take the vaccine if only adequate information is given to them while 19% agreed/strongly agree to accept the vaccine if the vaccine is taken by many people. This evokes that during the announcement and recommendation of the COVID-19 vaccine, we need to strengthen the broadcasting of appropriate information, to avoid giving missing or worrying information to pregnant mothers.

Understanding the barriers of vaccine acceptance is enormously vital, mainly in a pandemic situation, as vaccinating the majority of the people is considered very important in ending the pandemic. This could have an impact on logistical planning, and communications strategies and to development of context-specific measures to overcome any barriers. Therefore, it is significant in ensuring the effective implementation of vaccination programs. So, accepting and refusing the COVID-19 vaccine can be anticipated to change over time as new information were available and likely deviations in the epidemiological condition updates will be crucial.

4.1. Strengths and limitations of the study

Since this study was conducted in multiple health facilities in eastern Ethiopia and used face-to-face interviews rather than an online survey, it has the chance to be more representative and gather the opinion of participants at the grass-roots level and helps to produce a mechanism to improve the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant mothers. As a limitation, the causal relationship is not possible to determine in epidemiological studies like the nature of our study design. The data was not supported by qualitative findings.

5. Conclusion

In general, the findings from this study revealed that less than two-thirds of pregnant women had willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine if the safety and efficacy of the vaccine were approved by the concerned bodies. The most commonly reported reasons for unwillingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine were fear of side effects on the mother/fetus, belief that the vaccine was unreliable due to short development time, lack of long-term safety data during pregnancy on the fetus/mother, and think that no vaccine is required for COVID-19. Pregnant mothers' willingness to vaccine acceptance was significantly associated with educational status, information exposure regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, and having a history of chronic diseases. Thus, before commencing the COVID-19 vaccination program among pregnant women, the Ethiopian federal ministry of health and other concerned agencies needs to launch extensive public health information dissemination that could improve communities' awareness of the vaccine by tackling the existing distortion and mistrust about the vaccine. Besides, future public health intervention programs will better to emphasizes women with lower educational attainment backgrounds and those who had a history of chronic illness.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was secured from Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) (ref. no. IHRERC/069/2021). Informed, voluntary, written, and signed consent was obtained from each study participant before the interview, and their right to refuse or discontinue the interview at any time. They were also informed as the information obtained from them was treated with complete confidentiality.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Pertinent data were presented in this manuscript. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contribution statement

The authors (TG, BB, AE, AD, SN, BE, HB, AA, YD) made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to Haramaya University, College of health and medical sciences for allowing us to conduct this study. Our appreciation also goes to the data collectors, study participants, and data managers.

Contributor Information

Tamirat Getachew, Email: tamirget@gmail.com.

Bikila Balis, Email: bik.balis2008@gmail.com.

Addis Eyeberu, Email: addiseyeberu@gmail.com.

Adera Debella, Email: aksanadera62@gmail.com.

Shambel Nigussie, Email: shambelpharm02@gmail.com.

Sisay Habte, Email: sisayhabtem@yahoo.com.

Bajrond Eshetu, Email: bajeshetu@gmail.com.

Habtamu Bekele, Email: habti.bekele@gmail.com.

Addisu Alemu, Email: alemuadisu789@gmail.com.

Yadeta Dessie, Email: yad_de2005@yahoo.co.

References

- 1.Yue L., Han L., Li Q., Zhong M., Wang J., Wan Z., et al. MedRxiv; 2020. Anaesthesia and Infection Control in a Cesarean Section of Pregnant Women with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. World Health organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): vaccines. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines2020 Dec 12.

- 3.WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Postnatal Period. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blakeway H., Prasad S., Kalafat E., Heath P.T., Ladhani S.N., Le Doare K., et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022 Feb;226(2):236. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. e1-.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sculli M.A., Formoso G., Sciacca L. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant and lactating diabetic women. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021;31(7):2151–2155. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adhikari E.H., Spong C.Y. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant and lactating women. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1039–1040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray K.J., Bordt E.A., Atyeo C., Deriso E., Akinwunmi B., Young N., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;225(3):303. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riley L.E., Jamieson D.J. American College of Physicians; 2021. Inclusion of Pregnant and Lactating Persons in COVID-19 Vaccination Efforts; pp. 701–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Elimat T., AbuAlSamen M.M., Almomani B.A., Al-Sawalha N.A., Alali F.Q. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skjefte M., Ngirbabul M., Akeju O., Escudero D., Hernandez-Diaz S., Wyszynski D.F., et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021 Feb;36(2):197–211. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Male V. Are COVID-19 vaccines safe in pregnancy? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021 Apr;21(4):200–201. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00525-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mose A., Yeshaneh A. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in southwest Ethiopia: institutional-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021;14:2385. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S314346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson R.J., Paterson P., Jarrett C., Larson H.J. Understanding factors influencing vaccination acceptance during pregnancy globally: a literature review. Vaccine. 2015;33(47):6420–6429. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hailemariam S., Mekonnen B., Shifera N., Endalkachew B., Asnake M., Assefa A., et al. Predictors of pregnant women's intention to vaccinate against coronavirus disease 2019: a facility-based cross-sectional study in southwest Ethiopia. SAGE open medicine. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/20503121211038454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik A.A., McFadden S.M., Elharake J., Omer S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. Clin. Med. 2020;26 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dereje N., Tesfaye A., Tamene B., Alemshet D., Abe H., Tesfa N., et al. medRxiv; 2021. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Mixed-Methods Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ethiopia plans to vaccinate 20% population in 2022. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/ethiopia-plans-to-vaccinate-20-population-in-2021/21333462021.

- 18.CSA. Statistical report of the population and housing Census of west wollega. Ethiopia. 2007 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceulemans M., Foulon V., Panchaud A., Winterfeld U., Pomar L., Lambelet V., et al. Vaccine willingness and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's perinatal experiences and practices-A multinational, cross-sectional study covering the first wave of the pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021 Mar 24;(7):18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taye E.B., Taye Z.W., Muche H.A., Tsega N.T., Haile T.T., Tiguh A.E. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated factors among women attending antenatal and postnatal care in Central Gondar Zone public hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Clinical Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2022 Mar-Apr;14 doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2022.100993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Organization W.H. 2020. World Health Organization Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geoghegan S., O'Callaghan K.P., Offit P.A. Vaccine safety: myths and misinformation. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:372. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer C.C., Cristea V., Dub T., Sivelä J. High but slightly declining COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and reasons for vaccine acceptance, Finland April to December 2020. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021 May 11;149:e123. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821001114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pairat K., Phaloprakarn C. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy among Thai pregnant women and their spouses: a prospective survey. Reprod. Health. 2022 Mar 24;19(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goncu Ayhan S., Oluklu D., Atalay A., Menekse Beser D., Tanacan A., Moraloglu Tekin O., et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in pregnant women. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet.: Off. Organ Int. Federat. Gynaecol. Obst. 2021 Aug;154(2):291–296. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumari A., Mahey R., Kachhawa G., Kumari R., Bhatla N. Knowledge, attitude, perceptions, and concerns of pregnant and lactating women regarding COVID-19 vaccination: a cross-sectional survey of 313 participants from a tertiary care center of North India. Diabetes Metabol. Syndr. 2022 Mar;16(3) doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao L., Wang R., Han N., Liu J., Yuan C., Deng L., et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021 Aug 3;17(8):2378–2388. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1892432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Pertinent data were presented in this manuscript. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.