Abstract

Background:

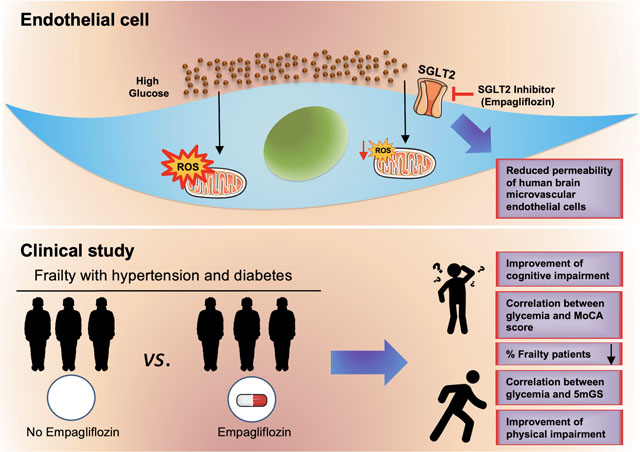

Frailty is a multidimensional condition often diagnosed in older adults with hypertension and diabetes, and both these conditions are associated with endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. We investigated the role of the Sodium GLucose co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin on cognitive frailty in diabetic and hypertensive older adults.

Methods:

We studied the effects of empagliflozin in consecutive hypertensive and diabetic older patients with frailty presenting at the ASL (local health unit of the Italian Ministry of Health) of Avellino, Italy, from March 2021 to January 2022. Moreover, we performed in vitro experiments in human endothelial cells to measure cell viability, permeability, mitochondrial Ca2+, and oxidative stress.

Results:

We evaluated 407 patients; 325 frail elders with diabetes successfully completed the study. We propensity score matched 75 patients treated with empagliflozin and 75 with no empagliflozin. We observed a correlation between glycemia and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score and between glycemia and 5-meter gait speed (5mGS). At 3-month follow up, we detected a significant improvement in the MoCA score and in the 5-meter gait speed in patients receiving empagliflozin compared to non-treated subjects. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that empagliflozin significantly reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and ROS production triggered by high-glucose in human endothelial cells, attenuates cellular permeability, and improves cell viability in response to oxidative stress.

Conclusions:

Taken together, our data indicate that empagliflozin reduces frailty in diabetic and hypertensive patients, most likely by decreasing mitochondrial ROS production in endothelial cells.

Keywords: diabetes, frailty, glifozins, hBMECs, hyperglycemia, mitochondria, mitochondrial Ca2+, occludin, cell permeability, ROS, SGLT2i

Graphical Abstract

Frailty is a multidimensional condition that leads to functional decline with physical and cognitive impairment1–3. Frailty is often diagnosed in older adults with hypertension and diabetes, and both these conditions are associated with endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress4–6.

Our group has recently evidenced the detrimental effects of hyperglycemia in frail hypertensive elders7. Several investigators have shown that hyperglycemia drives inflammation and oxidative stress leading to endothelial dysfunction, with a well-established negative impact on frail patients8–11.

In this scenario, Sodium GLucose co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors — which include the FDA approved drugs canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin12 — are considered among the most promising oral antidiabetic drugs to reach and maintain an optimal glycemic control in older subjects13. The main mechanism of action of these drugs is the blockage of SGLT2 proteins in the renal proximal convoluted tubules in order to reduce the reabsorption of filtered glucose and decrease the renal threshold for glucose, thereby promoting urinary glucose excretion14–17. Empagliflozin is a SGLT2 inhibitor that has been shown to reduce mortality and re-hospitalization for heart failure in diabetic patients18–23. Additional potential benefits of empagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors include improved cardiovascular energetics, reduced vascular tone and blood pressure, decreased renal dysfunction, increased circulating levels of ketone bodies, protection against pulmonary ischemia/reperfusion injury, and overall reduced systemic inflammation24–37.

On these grounds, we investigated the role of empagliflozin on cognitive frailty in diabetic and hypertensive older adults. To mechanistically confirm our results, we evaluated the effects of empagliflozin on mitochondrial oxidative stress and permeabilization in human endothelial cells.

METHODS

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Study Participants

We designed a prospective study to enroll consecutive hypertensive and diabetic older adults presenting at the ASL (local health unit of the Ministry of Health) of Avellino, Italy, from March 2021 to January 2022 with a diagnosis of frailty. Inclusion criteria: Age >65 years, a diagnosis of frailty, presence of diabetes and primary hypertension, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Score <26, Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) <30. Exclusion criteria: age <65 years, history of previous stroke. The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (Campania Nord). All subjects or their legal representatives signed an informed consent. The study had been registered in clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT04962841).

Clinical evaluation and assessment of cognitive and physical impairment

Blood glucose, HbA1c, and creatinine were measured in all patients. Clinical assessment was completed at baseline and after three months. Diabetes was defined according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines38. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg, and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg on repeated measurements, or use of antihypertensive medications39.

Frailty Assessment

A diagnosis of physical frailty was made with at least three out of the five Fried Criteria40, as we previously described41, 42:

Weight loss (unintentional loss ≥4.5 kg in the past year);

Weakness (handgrip strength in the lowest 20% quintile at baseline, adjusted for sex and body mass index);

Exhaustion (poor endurance and energy, self-reported);

Slowness (walking speed under the lowest quintile adjusted for sex and height);

Low physical activity level (lowest quintile of kilocalories of physical activity during the past week).

Additionally, we performed a 5-meter gait speed (5mGS) test43 in all patients. Cognitive function was evaluated by applying the MoCA test (cognitive impairment was defined by values <2641).

Ca2+ imaging

Ca2+ imaging experiments to measure mitochondrial Ca2+ were performed as we previously described described44, 45. Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs, passages 3–7) were plated in glass-bottom dishes using the “Ca2+ imaging solution”, which consists of: 138 mM NaCl, 5.3 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.38, adjusted with NaOH); to this solution we added 5 mM EGTA, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5 or 30 mM glucose, according to the experimental settings. Cells were loaded with Rhod-2 AM (3 μM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; catolog number: R1244) at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by washout and 1 h rest at room temperature for de-esterification: indeed, since Rhod-2 AM has a delocalized positive charge, it preferentially accumulates within the mitochondrial matrix, where it is hydrolyzed and trapped. Fluorescence was detected using a pass-band filter of 545–625 nm in response to excitation at 542 nm.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress

HUVECs were plated on glass bottom culture dishes and treated with different concentrations of glucose and empagliflozin for 24h; mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) were quantified by MitoSOX™ Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalog number: #M36008) as we described7, 46, using MitoTracker™ Green FM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog number: #M7514) to identify mitochondria.

Real time PCR (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green mix as previously described45, 47, 48; GAPDH was used as an internal standard; primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Endothelial permeability assay

Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMECs, passages 3–6) were cultured as we previously described7, 49. In some experiments, cells were treated with empagliflozin (1 μM), adding glucose at 5 or 30 mM, for 48 h. The endothelial permeability assay was performed using fibronectin-coated trans-well filters (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), as we previously reported7, 49, 50.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated in human brain microvascular endothelial cells using the [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, as we previously described44, 51. Briefly, cells were pretreated for 24 h with 1 μM empagliflozin and then incubated with increased doses of H2O2 for 5 h.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as n (%) for categorical data (compared using the χ2 test), mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous data (compared via Student’s t test or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc correction. Normality was verified using the Anderson-Darling test. A propensity score analysis was performed as described52 in order to minimize any selection bias due to the differences in clinical characteristics between the empagliflozin and the no-empagliflozin groups. Briefly, for each patient a propensity score was calculated by the use of a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression, applying the 1:1 nearest neighbor propensity score matching method. Variables that could potentially affect treatment assignment or outcomes were selected, including sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs. We developed a dispersion model using Pearson analysis to assess the correlation between glycemia and MoCA score and between glycemia and 5mGS. In order to adjust for potential confounders (selected a priori based on their clinical significance and possible confounding effect), we performed linear regression analyses with MoCA score or 5mGS test as dependent variables.

Statistical significance was considered based on 2-tailed P<0.05. All calculations were computed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY), and GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad by Dotmatics, Boston, MA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

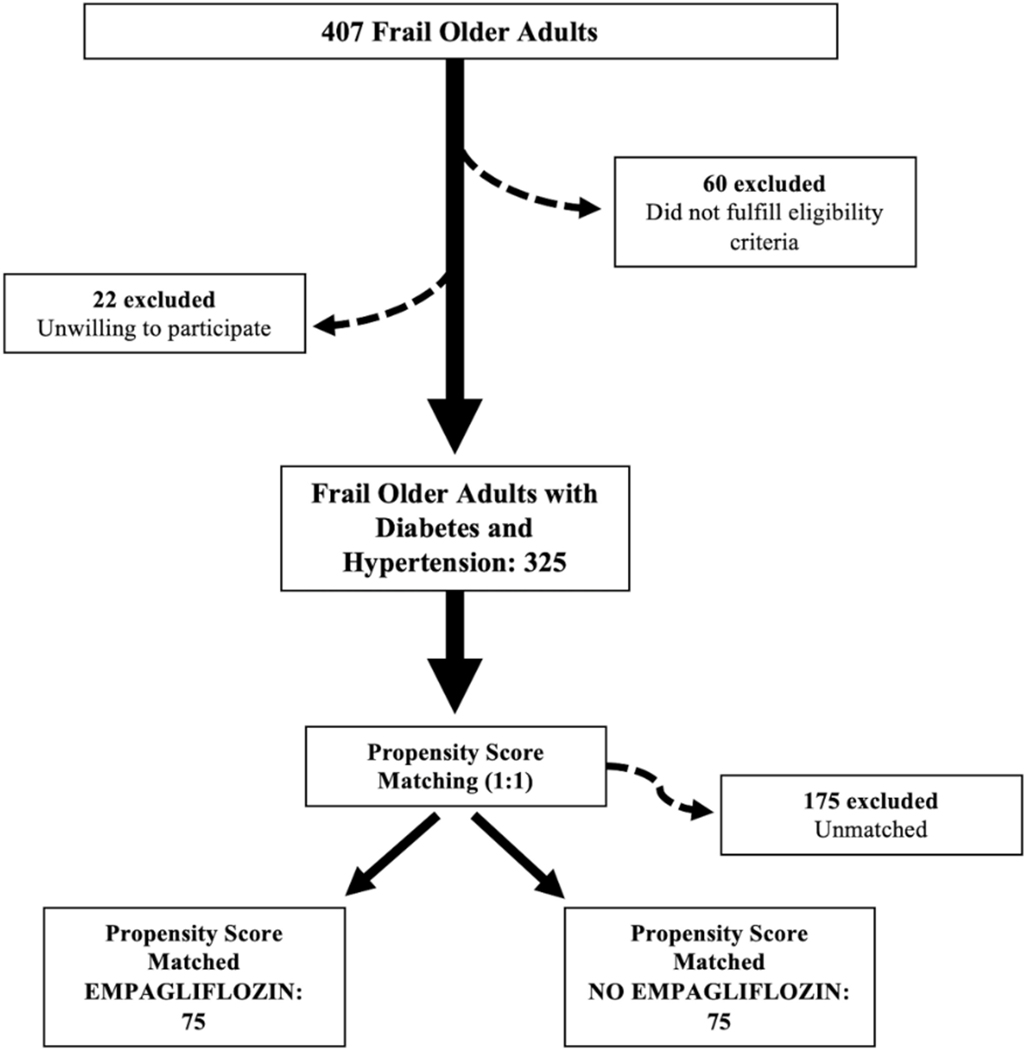

We evaluated 407 patients. Since 22 patients were unwilling to provide clinical information and 60 subjects did not fulfill eligibility criteria, 325 patients were enrolled. To minimize potential selection bias and confounding variables, we propensity-score-matched 150 patients, 75 treated with 10 mg empagliflozin in addition to standard therapy and 75 not receiving empagliflozin (Figure 1). At baseline, there were no significant differences in age, BMI, sex distribution, comorbidities, and laboratory parameters between the two groups (Table 1). Notably, MoCA score and 5mGS were not different among the two study arms at baseline (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of our population.

| Empagliflozin | No Empagliflozin | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 75 | 75 |

| Sex (M/F) | 36/39 | 35/40 |

| Age (years) | 78.05±7.5 | 78.62±6.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7±1.6 | 27.9±1.4 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 121.7±7.3 | 121.0±7.6 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.6±6.5 | 76.4±6.7 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 82.3±9.4 | 82.6±9.0 |

| 5mGS (m/s) | 0.60±0.12 | 0.59±0.13 |

| MoCA score | 20.32±4.2 | 20.35±4.3 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 39 (52.0) | 40 (53.0) |

| COPD | 32 (42.7) | 31 (41.0) |

| CKD | 38 (50.7) | 39 (52.0) |

| Previous Stroke | 12 (16.0) | 11 (15.0) |

| Laboratory analyses | ||

| Plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 153.87±71.6 | 153.36±73.1 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 61±7.5 | 61±6.2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0±0.2 | 1.0±0.2 |

5mGS: 5-meter gait speed; BMI: body mass index; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; HR: heart rate; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Empagliflozin significantly attenuates cognitive and physical impairment

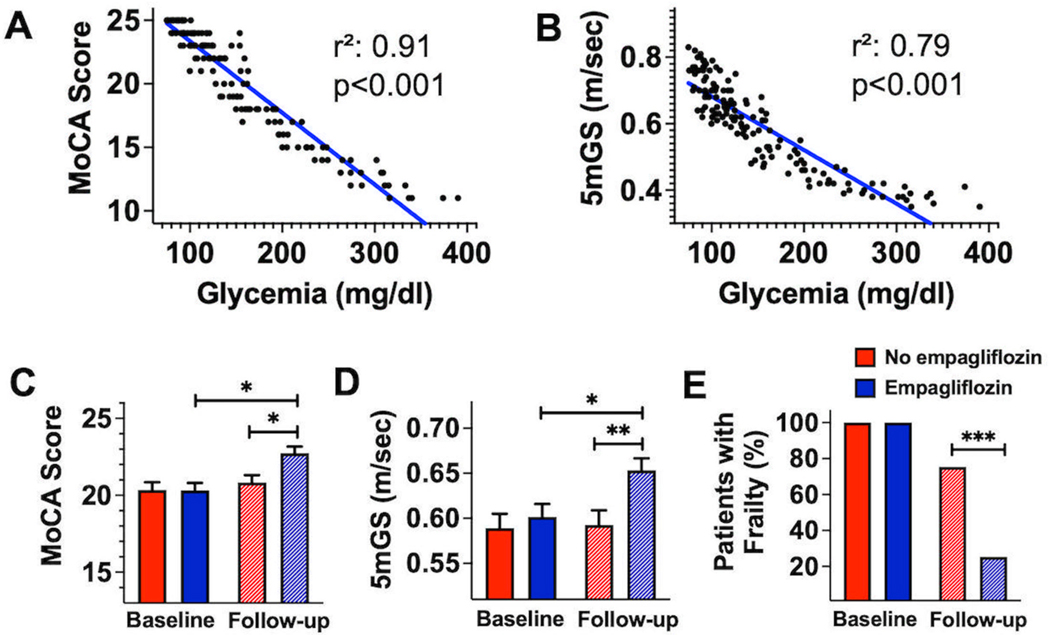

In our population, we observed a strong correlation between glycemia and MoCA score (r2: 0.91; p<0.001) (Figure 2A) and between glycemia and 5mGS (r2: 0.79; p<0.001) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Correlation between MoCA score and glycemia (A, r2: 0.91; p<0.001) and between 5mGS and glycemia (B, r2: 0.79; p<0.001). Differences in Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score (C), 5-meter gait speed (5mGS, D), and frailty (E) at baseline and at 3-month follow-up in empagliflozin treated and not-treated groups (*:p<0.05; **:p<0.01; ***:p<0.001).

We then evaluated the differences in MoCA score (Figure 2C) and 5mGS (Figure 2D) at baseline and at 3-month follow-up in empagliflozin treated and non-treated patients, observing significantly different favorable effects of the empagliflozin treatment.

Lastly, we assessed how many patients in the two study arms still had frailty at 3-month follow-up; the empagliflozin-treated group included only 25.3% of patients with frailty (n: 19), while in the non-empagliflozin group 73.3% of patients (n: 55) had frailty (p<0.001, Figure 2E).

Importantly, the significant correlation linking glycemia with MoCA score (Figure 2C) and 5mGS (Figure 2D) was confirmed after adjusting for potential confounders in multivariable regression analyses with MoCA Score or 5mGS as dependent variable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Linear regression analysis in the empagliflozin group using basal MoCA score (top) or 5mGs (bottom) as dependent variable.

| OR | S.E. | 95% C.I. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Age | −.024 | .019 | −.062 | .014 | .211 |

| BMI | .017 | .062 | −.105 | .139 | .781 |

| SBP | −.009 | .014 | −.036 | .018 | .530 |

| DBP | −.002 | .017 | −.035 | .031 | .903 |

| HR | .022 | .013 | −.004 | .047 | .093 |

| Dyslipidemia | −.099 | .212 | −.518 | .319 | .640 |

| CKD | −.140 | .221 | −.577 | .297 | .527 |

| COPD | .051 | .227 | −.397 | .500 | .821 |

| HbA1c | −.766 | .422 | −1.600 | .069 | .072 |

| Glycemia | −.046 | .005 | −.056 | −.037 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| OR | S.E. | 95% C.I. | p | ||

|

| |||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

|

| |||||

| Age | −.001 | .001 | −.003 | .001 | .418 |

| BMI | .002 | .003 | −.004 | .008 | .451 |

| SBP | .000 | .001 | −.001 | .001 | .739 |

| DBP | .000 | .001 | −.001 | .002 | .620 |

| HR | .001 | .001 | .000 | .002 | .055 |

| Dyslipidemia | −.010 | .010 | −.029 | .010 | .339 |

| CKD | −.001 | .010 | −.021 | .020 | .946 |

| COPD | .004 | .011 | −.017 | .025 | .711 |

| HbA1c | −.002 | .020 | −.041 | .038 | .936 |

| Glycemia | −.002 | .000 | −.002 | −.001 | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; HR: heart rate; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

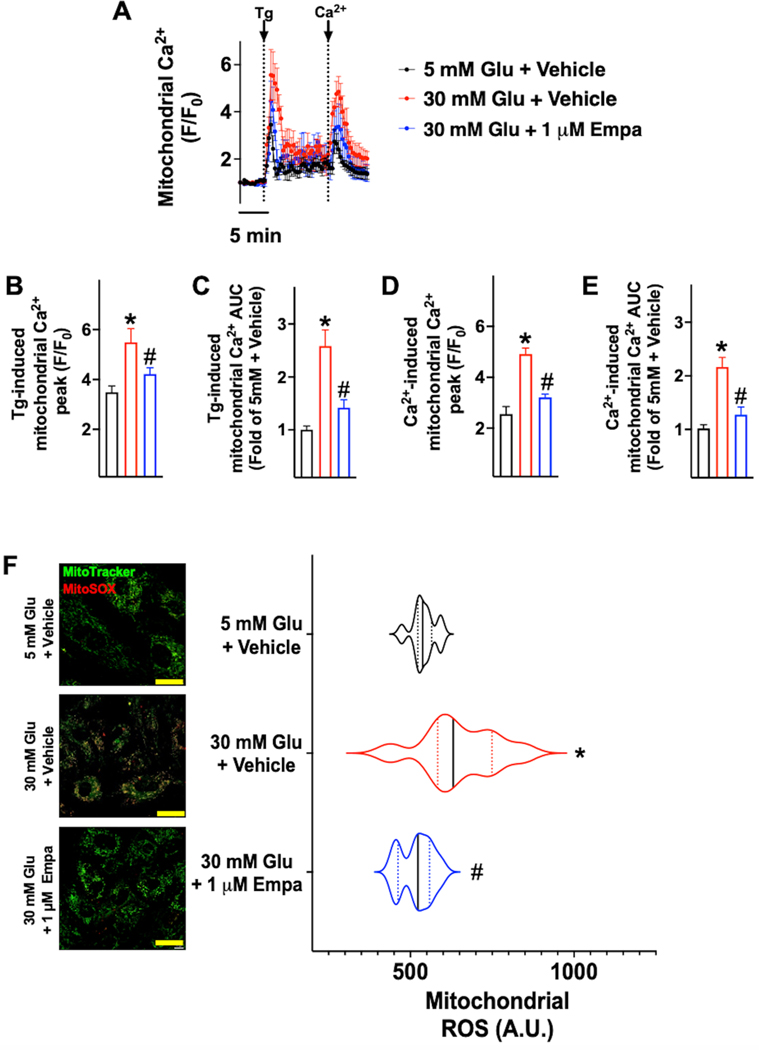

Empagliflozin reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and mitochondrial oxidative stress

To test whether empagliflozin could attenuate mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and ROS production, we cultured human endothelial cells in normal glucose (5 mM), high-glucose (30 mM), and high-glucose plus empagliflozin for 24h. High-glucose condition produced mitochondrial Ca2+ overload (Figure 3AE) and significantly augmented ROS production in these organelles (Figure 3F), while empagliflozin significantly attenuated these responses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of mitochondrial Ca2+ (A-E) and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (F-G) in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs, passages 3–7) treated for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of glucose (Glu) and empagliflozin (Empa). Mitochondrial Ca2+ (A-E) was measured in at least 30 cells per group, in triplicate independent biological replicates, in response to thapsigargin (Tg, 1 μM) or after the addition of 1.8 mM Ca2+. To assess the production of mitochondrial ROS, cells were stained with MitoTracker Green and mitoSOX Red (F, representative images from quadruplicate experiments; dimensional bar: 20 μm), and these assays have been quantified in the panel on the right; in the violin plot, median (solid line) and quartiles (dotted lines) are indicated; *: p<0.05 vs. 5 mM Glu + vehicle; #: p<0.05 vs. 30 mM Glu + Vehicle.

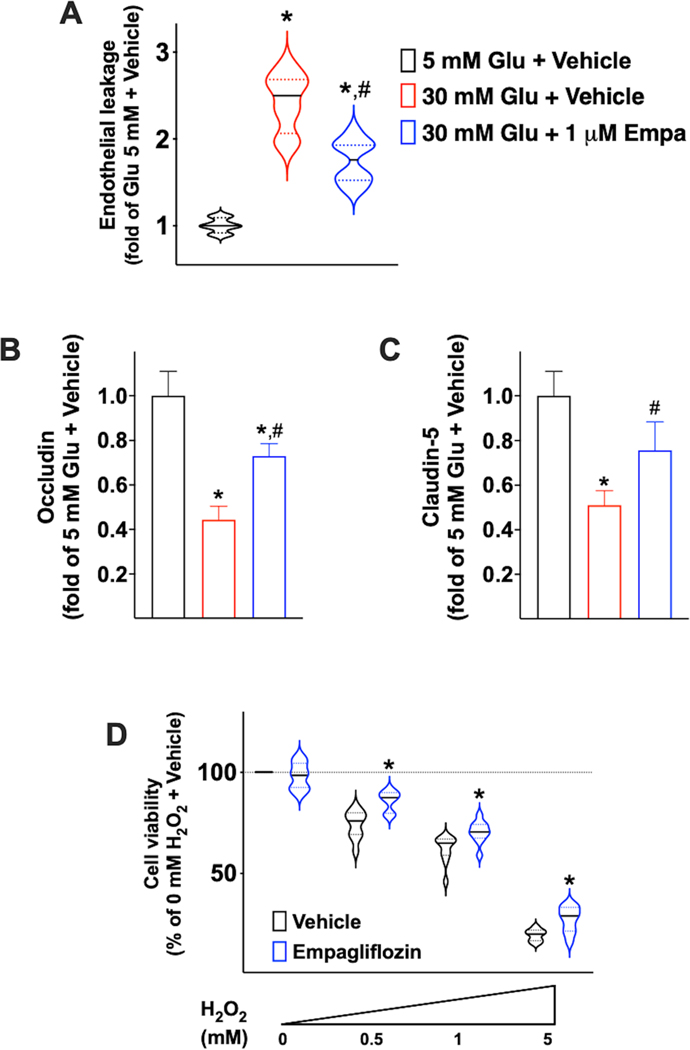

SGLT2 inhibition mitigates glucose-induced endothelial permeabilization

Hyperglycemia has been linked to an augmented vascular permeability53, 54 and endothelial leakage has been associated to cognitive decline and frailty55–60. Therefore, we sought to test whether inhibiting SGLT2 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells could attenuate endothelial leakage elicited by high-glucose concentrations. We observed that empagliflozin significantly attenuated the endothelial permeability induced by high-glucose (Figure 4A). To further confirm the effects of empagliflozin on endothelial leakage, we measured the expression levels of mRNA encoding for established junctional proteins (i.e. Claudin-5, Occludin) and we found that high-glucose concentrations significantly reduced the mRNA levels of both Claudin-5 (Figure 4B) and Occludin (Figure 4C), and these reductions were mitigated by empagliflozin (Figure 4BC).

Figure 4.

Effects of empagliflozin on cell permeability assessed in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (A) and mRNA levels of Occludin (B) and Claudin-5 (C); in the violin plot, median (solid line) and quartiles (dotted lines) are indicated; *: p<0.05 vs. 5 mM Glu + vehicle; #: p<0.05 vs. 30 mM Glu + vehicle. Effects of empagliflozin (1 μM) on cell viability (D) assessed in human brain microvascular endothelial cells in response to increasing doses of H2O2; the solid line indicates the median, whereas the dotted lines indicate the quartiles; *: p<0.05 vs. vehicle.

SGLT2 inhibition protects human endothelial cells from oxidative stress

Since we demonstrated in HUVECs that empagliflozin attenuates oxidative stress induced by high-glucose concentrations, we sought to confirm in human brain microvascular endothelial cells that inhibiting SGLT2 could improve cell viability in response to oxidative stress. Therefore, we pretreated human brain microvascular endothelial cells with empagliflozin and then we treated them with increasing concentrations of H2O2; after 5h, we observed that cell viability was significantly improved by empagliflozin (Figure 4D).

DISCUSSION

The compelling combination of clinical data and in vitro assays provided in the present study indicates that SGLT2 inhibition significantly improves cognitive and physical impairment in diabetic and hypertensive patients, most likely reducing oxidative stress in endothelial cells (Graphical Abstract).

Oxidative stress is known to be a common pathogenic substrate in hypertension61, diabetes62, and frailty63, 64. Specifically, a dysregulated mitochondrial fitness has been proposed as a potential root of age-related frailty65, and mitochondrial free radicals are crucial players in endothelial dysfunction66, 67. Henceforth, we sought to determine whether the favorable effects detected in the clinical setting could be attributable to an action on mitochondrial ROS generation at the endothelial level.

Our findings are in agreement with previous reports showing that hyperglycemia causes an augmented generation of mitochondrial ROS68, 69; in fact, mitochondrial ROS are recognized as a major cause of clinical complications associated with diabetes70, 71.

Hyperglycemia, alongside its actions on endothelial function, has been also associated with memory disturbances and a potential role in the development of cognitive impairment has been proposed72, 73. Thus, a stable glycemic control is seen as imperative to reduce the incidence of functional decline and to avoid complications74–78. Herein, we demonstrate that empagliflozin significantly improves cognitive impairment, assessed via MoCA, and physical decline, evaluated via 5mGS test, and we prove that these parameters, which we had previously shown to correlate with each other79, independently correlate with blood glucose levels. Remarkably, our data also indicate a direct effect of empagliflozin on endothelial cells, which goes beyond its actions merely attributable to a reduction of blood glucose80–82 or to the offsetting of insulin resistance83–86. Specifically, we show that SGLT2 inhibition significantly attenuates mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and the subsequent increase in ROS production in human endothelial cells.

The new 2022 guidelines on the management of heart failure87 of the American-Heart-Association, the American-College-of-Cardiology, and the Heart-Failure-Society-of-America, recommend SGLT2-inhibitors as Class 1A in HFrEF and Class 2A in HFmrEF and HFpEF (conditions in which ARNI and MRA have weaker recommendations: Class 2B). These recommendations are mainly based on the protective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes, independent of the glucose-lowering effects, revealed by recent clinical trials: the DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure)88, the EMPEROR-HF (Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction)89, and the EMPEROR-PRESERVED (Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction)21 trials. However, the exact mechanism underlying these beneficial effects on cardiovascular outcomes have remained hitherto elusive.

Our results are consistent with a pilot study testing the acute effects of dapagliflozin in 16 diabetic patients, showing a marked reduction of urinary isoprostanes, a surrogate of systemic oxidative stress 48 hours after administration compared to baseline values90. In our study, we also proved that empagliflozin counteracts the increased endothelial permeability induced by high-glucose, by regulating the expression of Occludin and Claudin-5 at the transcriptional level, tight junction proteins that have been shown to partake in cognitive impairment91–93. Claudin-5 levels were also shown to be reduced in the nuclus accumbens of patients with depression94, 95. Additionally, empagliflozin significantly prevented the death of cerebral endothelial cells induced by oxidative stress, and these data are particularly relevant when considering that oxidative stress is fundamental in process like senescence and aging96–100. Therefore, our findings are highly suggestive for a potential role of SGLT2 inhibitors in preventing neurodegenerative disorders.

Strengths of our study include its prospective nature, the analysis of a real-world homogeneous population of elderly patients with diabetes and hypertension, the integration of clinical and in vitro data, and the consistency of the beneficial effects of empagliflozin in two different types of human endothelial cells, namely cells obtained from the umbilical vein and brain microvascular endothelial cells. Nevertheless, our study is not exempt from limitations, including the relatively brief follow-up, having tested the effects of only one SGLT2 inhibitor, and having enrolled only Caucasian patients.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Relevance.

What Is New?

The Sodium GLucose co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor Empagliflozin improves both cognitive and physical impairment in frail patients with hypertension and diabetes.

Empagliflozin ameliorates endothelial dysfunction induced by high-glucose.

Empagliflozin reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and oxidative stress in endothelial cells.

What Is Relevant?

SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to have beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system but the underlying mechanisms were not fully understood.

This work indicates that SGLT2 inhibitors have favorable effects on different types of human endothelial cells, i.e. umbilical and brain microvascular endothelial cells.

Clinical/Pathophysiological Implications?

The management of frailty in older adults should consider the expected benefits given by the treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors especially taking into account the pathophysiological rationale provided by this study, in terms of improvement of endothelial function and reduced oxidative stress.

Perspectives.

Based on our results and on the emerging pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors26, we speculate that SGLT2 inhibitors may be considered as an anti-frailty drug. This view is strongly supported by the beneficial effects of empagliflozin on endothelial cells, in terms of mitigated mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, reduced oxidative stress, and improved cell viability.

Sources of Funding:

The Santulli’s Lab is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH: R01-DK123259, R01-DK033823, R01-HL146691, R01-HL159062, R56-AG066431, T32-HL144456, and R00-DK107895, to G.S.), by the Irma T. Hirschl and Monique Weill-Caulier Trusts (to G.S.), by the Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation (to G.S.), and by the American Heart Association (AHA-22POST915561 to F.V. and AHA-21POST836407 to S.J.J.).

Nonstandard abbreviations

- 5mGS

5-meter Gait Speed

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- Ca2+

Calcium

- CKD

Chronic Kidney Disease

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- HbA1c

Glycated Hemoglobin

- hBMECs

Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells

- HR

Heart Rate

- HUVECs

Human Umbilical Vascular Endothelial Cells

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- SGLT2

Sodium GLucose co-Transporter 2

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsui A, Searle SD, Bowden H, Hoffmann K, Hornby J, Goslett A, Weston-Clarke M, Howes LH, Street R, Perera R, Taee K, Kustermann C, Chitalu P, Razavi B, Magni F, Das D, Kim S, Chaturvedi N, Sampson EL, Rockwood K, Cunningham C, Ely EW, Richardson SJ, Brayne C, Terrera GM, Tieges Z, MacLullich A and Davis D. The effect of baseline cognition and delirium on long-term cognitive impairment and mortality: a prospective population-based study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3:e232–e241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Promislow D, Anderson RM, Scheffer M, Crespi B, DeGregori J, Harris K, Horowitz BN, Levine ME, Riolo MA, Schneider DS, Spencer SL, Valenzano DR and Hochberg ME. Resilience integrates concepts in aging research. iScience. 2022;25:104199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marinus N, Vigorito C, Giallauria F, Dendale P, Meesen R, Bokken K, Haenen L, Jansegers T, Vandenheuvel Y, Scherrenberg M, Spildooren J and Hansen D. Frailty Test Battery Development including Physical, Socio-Psychological and Cognitive Domains for Cardiovascular Disease Patients: A Preliminary Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kremer KM, Braisch U, Rothenbacher D, Denkinger M, Dallmeier D and Acti FESG. Systolic Blood Pressure and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Frailty as an Effect Modifier. Hypertension. 2022;79:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouch L, Rolland Y, Hanon O, Vidal JS, Cestac P, Sallerin B, Andrieu S, Vellas B, Barreto PS and Group MD. Blood pressure, antihypertensive drugs, and incident frailty: The Multidomain Alzheimer Preventive Trial (MAPT). Maturitas. 2022;162:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott ML, Caspi A, Houts RM, Ambler A, Broadbent JM, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Hogan S, Keenan R, Knodt A, Leung JH, Melzer TR, Purdy SC, Ramrakha S, Richmond-Rakerd LS, Righarts A, Sugden K, Thomson WM, Thorne PR, Williams BS, Wilson G, Hariri AR, Poulton R and Moffitt TE. Disparities in the pace of biological aging among midlife adults of the same chronological age have implications for future frailty risk and policy. Nat Aging. 2021;1:295–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mone P, Gambardella J, Pansini A, de Donato A, Martinelli G, Boccalone E, Matarese A, Frullone S and Santulli G. Cognitive Impairment in Frail Hypertensive Elderly Patients: Role of Hyperglycemia. Cells. 2021;10:2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Prior JC, Leslie WD, Thabane L, Papaioannou A, Josse RG, Kaiser SM, Kovacs CS, Anastassiades T, Towheed T, Davison KS, Levine M, Goltzman D, Adachi JD and CaMos Research G. Frailty and Risk of Fractures in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ida S, Kaneko R, Imataka K and Murata K. Relationship between frailty and mortality, hospitalization, and cardiovascular diseases in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odegaard AO, Jacobs DR Jr., Sanchez OA, Goff DC Jr., Reiner AP and Gross MD. Oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clegg A and Hassan-Smith Z. Frailty and the endocrine system. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teo YN, Ting AZH, Teo YH, Chong EY, Tan JTA, Syn NL, Chia AZQ, Ong HT, Cheong AJY, Li TY, Poh KK, Yeo TC, Chan MY, Wong RCC, Chai P and Sia CH. Effects of Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors and Combined SGLT1/2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Renal, and Safety Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes: A Network Meta-Analysis of 111 Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2022;22:299–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, Benson G, Brown FM, Freeman R, Green J, Huang E, Isaacs D, Kahan S, Leon J, Lyons SK, Peters AL, Prahalad P, Reusch JEB and Young-Hyman D. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S195–S207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagasu H, Yano Y, Kanegae H, Heerspink HJL, Nangaku M, Hirakawa Y, Sugawara Y, Nakagawa N, Tani Y, Wada J, Sugiyama H, Tsuruya K, Nakano T, Maruyama S, Wada T, Yamagata K, Narita I, Tamura K, Yanagita M, Terada Y, Shigematsu T, Sofue T, Ito T, Okada H, Nakashima N, Kataoka H, Ohe K, Okada M, Itano S, Nishiyama A, Kanda E, Ueki K and Kashihara N. Kidney Outcomes Associated With SGLT2 Inhibitors Versus Other Glucose-Lowering Drugs in Real-world Clinical Practice: The Japan Chronic Kidney Disease Database. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2542–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsuno K, Fujimori Y, Takemura Y, Hiratochi M, Itoh F, Komatsu Y, Fujikura H and Isaji M. Sergliflozin, a novel selective inhibitor of low-affinity sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT2), validates the critical role of SGLT2 in renal glucose reabsorption and modulates plasma glucose level. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuen BL, Young T, Heerspink HJL, Neal B, Perkovic V, Billot L, Mahaffey KW, Charytan DM, Wheeler DC, Arnott C, Bompoint S, Levin A and Jardine MJ. SGLT2 inhibitors for the prevention of kidney failure in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giorgino F, Vora J, Fenici P and Solini A. Renoprotection with SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes over a spectrum of cardiovascular and renal risk. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei W, Liu J, Chen S, Xu X, Guo D, He Y, Huang Z, Wang B, Huang H, Li Q, Chen J, Chen H, Tan N and Liu Y. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter Type 2 Inhibitors Improve Cardiorenal Outcome of Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:850836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y, Yang P, Fu L, Sun L, Shen W and Wu Q. Comparative Cardiovascular Outcomes of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:802992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braunwald E. SGLT2 inhibitors: the statins of the 21st century. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:1029–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Bohm M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure-Valenzuela E, Giannetti N, Gomez-Mesa JE, Janssens S, Januzzi JL, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone SV, Pina IL, Ponikowski P, Senni M, Sim D, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Tsutsui H, Verma S, Vinereanu D, Zhang J, Carson P, Lam CSP, Marx N, Zeller C, Sattar N, Jamal W, Schnaidt S, Schnee JM, Brueckmann M, Pocock SJ, Zannad F, Packer M and Investigators EM-PT. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1451–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos-Gallego CG, Vargas-Delgado AP, Requena-Ibanez JA, Garcia-Ropero A, Mancini D, Pinney S, Macaluso F, Sartori S, Roque M, Sabatel-Perez F, Rodriguez-Cordero A, Zafar MU, Fergus I, Atallah-Lajam F, Contreras JP, Varley C, Moreno PR, Abascal VM, Lala A, Tamler R, Sanz J, Fuster V, Badimon JJ and Investigators E-T. Randomized Trial of Empagliflozin in Nondiabetic Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE and Investigators E-RO. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sciannameo V, Berchialla P, Avogaro A, Fadini GP and Network D-TD. Transposition of cardiovascular outcome trial effects to the real-world population of patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang CT, Peng ZY, Chen YC, Ou HT and Kuo S. Cardiovascular Benefits With Favorable Renal, Amputation and Hypoglycemic Outcomes of SGLT-2 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes From the Asian Perspective: A Population-Based Cohort Study and Systematic Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:836365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarafidis P, Papadopoulos CE, Kamperidis V, Giannakoulas G and Doumas M. Cardiovascular Protection With Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors and Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Milestone Achieved. Hypertension. 2021;77:1442–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jun S, Aon MA and Paolocci N. Empagliflozin and HFrEF: Known and Possible Benefits of NHE1 Inhibition. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4:841–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen J, Omar M, Kistorp C, Tuxen C, Gustafsson I, Kober L, Gustafsson F, Faber J, Malik ME, Fosbol EL, Bruun NE, Forman JL, Jensen LT, Moller JE and Schou M. Effects of empagliflozin on estimated extracellular volume, estimated plasma volume, and measured glomerular filtration rate in patients with heart failure (Empire HF Renal): a prespecified substudy of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prattichizzo F, De Nigris V, Micheloni S, La Sala L and Ceriello A. Increases in circulating levels of ketone bodies and cardiovascular protection with SGLT2 inhibitors: Is low-grade inflammation the neglected component? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2515–2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang A, Luo X, Meng H, Kang J, Qin G, Chen Y and Zhang X. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors Reduce the Risk of Heart Failure Hospitalization in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:604250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang D, Ju F, Du L, Liu T, Zuo Y, Abbott GW and Hu Z. Empagliflozin Protects against Pulmonary Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury via an Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases 1 and 2-Dependent Mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2022;380:230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capolongo G, Capasso G and Viggiano D. A Shared Nephroprotective Mechanism for Renin-Angiotensin-System Inhibitors, Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors, and Vasopressin Receptor Antagonists: Immunology Meets Hemodynamics. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Stefano A, Tesauro M, Di Daniele N, Vizioli G, Schinzari F and Cardillo C. Mechanisms of SGLT2 (Sodium-Glucose Transporter Type 2) Inhibition-Induced Relaxation in Arteries From Human Visceral Adipose Tissue. Hypertension. 2021;77:729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verma S, Mazer CD, Yan AT, Mason T, Garg V, Teoh H, Zuo F, Quan A, Farkouh ME, Fitchett DH, Goodman SG, Goldenberg RM, Al-Omran M, Gilbert RE, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, Juni P, Zinman B and Connelly KA. Effect of Empagliflozin on Left Ventricular Mass in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Coronary Artery Disease: The EMPA-HEART CardioLink-6 Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2019;140:1693–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oshima H, Miki T, Kuno A, Mizuno M, Sato T, Tanno M, Yano T, Nakata K, Kimura Y, Abe K, Ohwada W and Miura T. Empagliflozin, an SGLT2 Inhibitor, Reduced the Mortality Rate after Acute Myocardial Infarction with Modification of Cardiac Metabolomes and Antioxidants in Diabetic Rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;368:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvatore T, Galiero R, Caturano A, Rinaldi L, Di Martino A, Albanese G, Di Salvo J, Epifani R, Marfella R, Docimo G, Lettieri M, Sardu C and Sasso FC. An Overview of the Cardiorenal Protective Mechanisms of SGLT2 Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pietschner R, Kolwelter J, Bosch A, Striepe K, Jung S, Kannenkeril D, Ott C, Schiffer M, Achenbach S and Schmieder RE. Effect of empagliflozin on ketone bodies in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Diabetes A. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:S11–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, Khan NA, Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Ramirez A, Schlaich M, Stergiou GS, Tomaszewski M, Wainford RD, Williams B and Schutte AE. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA and Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research G. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mone P, Lombardi A, Gambardella J, Pansini A, Macina G, Morgante M, Frullone S and Santulli G. Empagliflozin improves cognitive impairment in frail older adults with type 2 diabetes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:1247–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pansini A, Lombardi A, Morgante M, Frullone S, Marro A, Rizzo M, Martinelli G, Boccalone E, De Luca A, Santulli G and Mone P. Hyperglycemia and Physical Impairment in Frail Hypertensive Older Adults. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:831556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, Maurer MS, Green P, Allen LA, Popma JJ, Ferrucci L and Forman DE. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:747–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lombardi A, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G and Santulli G. Impaired mitochondrial calcium uptake caused by tacrolimus underlies beta-cell failure. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lombardi A, Gambardella J, Du XL, Sorriento D, Mauro M, Iaccarino G, Trimarco B and Santulli G. Sirolimus induces depletion of intracellular calcium stores and mitochondrial dysfunction in pancreatic beta cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santulli G, Xie W, Reiken SR and Marks AR. Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11389–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morelli MB, Shu J, Sardu C, Matarese A and Santulli G. Cardiosomal microRNAs Are Essential in Post-Infarction Myofibroblast Phenoconversion. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan Q, Chen Z, Santulli G, Gu L, Yang ZG, Yuan ZQ, Zhao YT, Xin HB, Deng KY, Wang SQ and Ji G. Functional role of Calstabin2 in age-related cardiac alterations. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mone P, Gambardella J, Wang X, Jankauskas SS, Matarese A and Santulli G. miR-24 Targets the Transmembrane Glycoprotein Neuropilin-1 in Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Noncoding RNA. 2021;7:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gambardella J, Sorriento D, Bova M, Rusciano M, Loffredo S, Wang X, Petraroli A, Carucci L, Mormile I, Oliveti M, Bruno Morelli M, Fiordelisi A, Spadaro G, Campiglia P, Sala M, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G, Santulli G and Ciccarelli M. Role of Endothelial G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase 2 in Angioedema. Hypertension. 2020;76:1625–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Vitis S, Sonia Treglia A, Ulianich L, Turco S, Terrazzano G, Lombardi A, Miele C, Garbi C, Beguinot F and Di Jeso B. Tyr phosphatase-mediated P-ERK inhibition suppresses senescence in EIA + v-raf transformed cells, which, paradoxically, are apoptosis-protected in a MEK-dependent manner. Neoplasia. 2011;13:120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mone P, Gambardella J, Minicucci F, Lombardi A, Mauro C and Santulli G. Hyperglycemia Drives Stent Restenosis in STEMI Patients. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:e192–e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aronson D and Rayfield EJ. How hyperglycemia promotes atherosclerosis: molecular mechanisms. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2002;1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clemmer JS, Xiang L, Lu S, Mittwede PN and Hester RL. Hyperglycemia-Mediated Oxidative Stress Increases Pulmonary Vascular Permeability. Microcirculation. 2016;23:221–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Montgolfier O, Pincon A, Pouliot P, Gillis MA, Bishop J, Sled JG, Villeneuve L, Ferland G, Levy BI, Lesage F, Thorin-Trescases N and Thorin E. High Systolic Blood Pressure Induces Cerebral Microvascular Endothelial Dysfunction, Neurovascular Unit Damage, and Cognitive Decline in Mice. Hypertension. 2019;73:217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen YC, Lu BZ, Shu YC and Sun YT. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Cerebral Vascular Permeability in Type 2 Diabetes-Related Cerebral Microangiopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:805637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rajeev V, Fann DY, Dinh QN, Kim HA, De Silva TM, Lai MKP, Chen CL, Drummond GR, Sobey CG and Arumugam TV. Pathophysiology of blood brain barrier dysfunction during chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in vascular cognitive impairment. Theranostics. 2022;12:1639–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adamski MG, Sternak M, Mohaissen T, Kaczor D, Wieronska JM, Malinowska M, Czaban I, Byk K, Lyngso KS, Przyborowski K, Hansen PBL, Wilczynski G and Chlopicki S. Vascular Cognitive Impairment Linked to Brain Endothelium Inflammation in Early Stages of Heart Failure in Mice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li M, Li Y, Zuo L, Hu W and Jiang T. Increase of blood-brain barrier leakage is related to cognitive decline in vascular mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurol. 2021;21:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang F, Cao Y, Ma L, Pei H, Rausch WD and Li H. Dysfunction of Cerebrovascular Endothelial Cells: Prelude to Vascular Dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guzik TJ and Touyz RM. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Vascular Aging in Hypertension. Hypertension. 2017;70:660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vaidya AR, Wolska N, Vara D, Mailer RK, Schroder K and Pula G. Diabetes and Thrombosis: A Central Role for Vascular Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alabadi B, Civera M, De la Rosa A, Martinez-Hervas S, Gomez-Cabrera MC and Real JT. Frailty Is Associated with Oxidative Stress in Older Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2021;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernabeu-Wittel M, Gomez-Diaz R, Gonzalez-Molina A, Vidal-Serrano S, Diez-Manglano J, Salgado F, Soto-Martin M, Ollero-Baturone M and On Behalf Of The Proteo R. Oxidative Stress, Telomere Shortening, and Apoptosis Associated to Sarcopenia and Frailty in Patients with Multimorbidity. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferrucci L and Zampino M. A mitochondrial root to accelerated ageing and frailty. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:133–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shenouda SM, Widlansky ME, Chen K, Xu G, Holbrook M, Tabit CE, Hamburg NM, Frame AA, Caiano TL, Kluge MA, Duess MA, Levit A, Kim B, Hartman ML, Joseph L, Shirihai OS and Vita JA. Altered mitochondrial dynamics contributes to endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;124:444–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Widlansky ME and Gutterman DD. Regulation of endothelial function by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1517–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang H, Shen Y, Kim IM, Weintraub NL and Tang Y. The Impaired Bioenergetics of Diabetic Cardiac Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:642857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki K, Olah G, Modis K, Coletta C, Kulp G, Gero D, Szoleczky P, Chang T, Zhou Z, Wu L, Wang R, Papapetropoulos A and Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide replacement therapy protects the vascular endothelium in hyperglycemia by preserving mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13829–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaludercic N and Di Lisa F. Mitochondrial ROS Formation in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nishikawa T and Araki E. Impact of mitochondrial ROS production in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kerti L, Witte AV, Winkler A, Grittner U, Rujescu D and Floel A. Higher glucose levels associated with lower memory and reduced hippocampal microstructure. Neurology. 2013;81:1746–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rom S, Zuluaga-Ramirez V, Gajghate S, Seliga A, Winfield M, Heldt NA, Kolpakov MA, Bashkirova YV, Sabri AK and Persidsky Y. Hyperglycemia-Driven Neuroinflammation Compromises BBB Leading to Memory Loss in Both Diabetes Mellitus (DM) Type 1 and Type 2 Mouse Models. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:1883–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.ADA. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S168–S179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laiteerapong N, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Sudore R, Schillinger D, John PM and Huang ES. Correlates of quality of life in older adults with diabetes: the diabetes & aging study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1749–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shaw KM. Overcoming the hurdles to achieving glycemic control. Metabolism. 2006;55:S6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zaslavsky O, Walker RL, Crane PK, Gray SL and Larson EB. Glucose Levels and Risk of Frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:1223–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tamura Y, Omura T, Toyoshima K and Araki A. Nutrition Management in Older Adults with Diabetes: A Review on the Importance of Shifting Prevention Strategies from Metabolic Syndrome to Frailty. Nutrients. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mone P, Gambardella J, Lombardi A, Pansini A, De Gennaro S, Leo AL, Famiglietti M, Marro A, Morgante M, Frullone S, De Luca A and Santulli G. Correlation of physical and cognitive impairment in diabetic and hypertensive frail older adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vallon V, Gerasimova M, Rose MA, Masuda T, Satriano J, Mayoux E, Koepsell H, Thomson SC and Rieg T. SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin reduces renal growth and albuminuria in proportion to hyperglycemia and prevents glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetic Akita mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M and Pagano G. A novel approach to control hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: sodium glucose co-transport (SGLT) inhibitors: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Med. 2012;44:375–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Brien TP, Jenkins EC, Estes SK, Castaneda AV, Ueta K, Farmer TD, Puglisi AE, Swift LL, Printz RL and Shiota M. Correcting Postprandial Hyperglycemia in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats With an SGLT2 Inhibitor Restores Glucose Effectiveness in the Liver and Reduces Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle. Diabetes. 2017;66:1172–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Al-Wakeel DE, El-Kashef DH and Nader MA. Renoprotective effect of empagliflozin in cafeteria diet-induced insulin resistance in rats: Modulation of HMGB-1/TLR-4/NF-kappaB axis. Life Sci. 2022;301:120633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kullmann S, Hummel J, Wagner R, Dannecker C, Vosseler A, Fritsche L, Veit R, Kantartzis K, Machann J, Birkenfeld AL, Stefan N, Haring HU, Peter A, Preissl H, Fritsche A and Heni M. Empagliflozin Improves Insulin Sensitivity of the Hypothalamus in Humans With Prediabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu L, Nagata N, Chen G, Nagashimada M, Zhuge F, Ni Y, Sakai Y, Kaneko S and Ota T. Empagliflozin reverses obesity and insulin resistance through fat browning and alternative macrophage activation in mice fed a high-fat diet. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2019;7:e000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, Santulli G, Gallinoro E, Cesaro A, Gragnano F, Sardu C, Mileva N, Foa A, Armillotta M, Sansonetti A, Amicone S, Impellizzeri A, Casella G, Mauro C, Vassilev D, Marfella R, Calabro P, Barbato E and Pizzi C. Infarct size, inflammatory burden, and admission hyperglycemia in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with SGLT2-inhibitors: a multicenter international registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Santulli G, Wang X and Mone P. Updated ACC/AHA/HFSA 2022 guidelines on heart failure: what’s new? from epidemiology to clinical management. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2022;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Belohlavek J, Bohm M, Chiang CE, Chopra VK, de Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukat A, Ge J, Howlett JG, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman CEA, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O’Meara E, Petrie MC, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Held C, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Bengtsson O, Sjostrand M, Langkilde AM, Committees D-HT and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Kimura K, Schnee J, Zeller C, Cotton D, Bocchi E, Bohm M, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure E, Giannetti N, Janssens S, Zhang J, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Kaul S, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone S, Pina I, Ponikowski P, Sattar N, Senni M, Seronde MF, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Wanner C, Zannad F and Investigators EM-RT. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Solini A, Giannini L, Seghieri M, Vitolo E, Taddei S, Ghiadoni L and Bruno RM. Dapagliflozin acutely improves endothelial dysfunction, reduces aortic stiffness and renal resistive index in type 2 diabetic patients: a pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamazaki Y, Shinohara M, Shinohara M, Yamazaki A, Murray ME, Liesinger AM, Heckman MG, Lesser ER, Parisi JE, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Kanekiyo T and Bu G. Selective loss of cortical endothelial tight junction proteins during Alzheimer’s disease progression. Brain. 2019;142:1077–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Greene C, Hanley N and Campbell M. Claudin-5: gatekeeper of neurological function. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2019;16:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hussain B, Fang C and Chang J. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown: An Emerging Biomarker of Cognitive Impairment in Normal Aging and Dementia. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:688090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Menard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE, Kana V, Wang VX, Bouchard S, Takahashi A, Flanigan ME, Aleyasin H, LeClair KB, Janssen WG, Labonte B, Parise EM, Lorsch ZS, Golden SA, Heshmati M, Tamminga C, Turecki G, Campbell M, Fayad ZA, Tang CY, Merad M and Russo SJ. Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1752–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dudek KA, Dion-Albert L, Lebel M, LeClair K, Labrecque S, Tuck E, Ferrer Perez C, Golden SA, Tamminga C, Turecki G, Mechawar N, Russo SJ and Menard C. Molecular adaptations of the blood-brain barrier promote stress resilience vs. depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:3326–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reskiawan AKR, Alwjwaj M, Ahmad Othman O, Rakkar K, Sprigg N, Bath PM and Bayraktutan U. Inhibition of oxidative stress delays senescence and augments functional capacity of endothelial progenitor cells. Brain Res. 2022;1787:147925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chandrasekaran A, Idelchik M and Melendez JA. Redox control of senescence and age-related disease. Redox Biol. 2017;11:91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kiss T, Tarantini S, Csipo T, Balasubramanian P, Nyul-Toth A, Yabluchanskiy A, Wren JD, Garman L, Huffman DM, Csiszar A and Ungvari Z. Circulating anti-geronic factors from heterochonic parabionts promote vascular rejuvenation in aged mice: transcriptional footprint of mitochondrial protection, attenuation of oxidative stress, and rescue of endothelial function by young blood. Geroscience. 2020;42:727–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Valeri A, Chiricosta L, Calcaterra V, Biasin M, Cappelletti G, Carelli S, Zuccotti GV, Bramanti P, Pelizzo G, Mazzon E and Gugliandolo A. Transcriptomic Analysis of HCN-2 Cells Suggests Connection among Oxidative Stress, Senescence, and Neuron Death after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cells. 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liguori I, Russo G, Curcio F, Bulli G, Aran L, Della-Morte D, Gargiulo G, Testa G, Cacciatore F, Bonaduce D and Abete P. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:757–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.