Abstract

Immunization with whole-cell pertussis vaccines (WCV) containing heat-killed Bordetella pertussis cells and with acellular vaccines containing genetically or chemically detoxified pertussis toxin (PT) in combination with filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin (Prn), or fimbriae confers protection in humans and animals against B. pertussis infection. In an earlier study we demonstrated that FHA is involved in the adherence of these bacteria to human bronchial epithelial cells. In the present study we investigated whether mouse antibodies directed against B. pertussis FHA, PTg, Prn, and fimbriae, or against two other surface molecules, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the 40-kDa outer membrane porin protein (OMP), that are not involved in bacterial adherence, were able to block adherence of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis to human bronchial epithelial cells. All antibodies studied inhibited the adherence of B. pertussis to these epithelial cells and were equally effective in this respect. Only antibodies against LPS and 40-kDa OMP affected the adherence of B. parapertussis to epithelial cells. We conclude that antibodies which recognize surface structures on B. pertussis or on B. parapertussis can inhibit adherence of the bacteria to bronchial epithelial cells, irrespective whether these structures play a role in adherence of the bacteria to these cells.

Bordetella pertussis is the major causative agent of whooping cough (pertussis), a highly contagious infection of the respiratory tract in humans. To establish efficient colonization of the respiratory tract, this gram-negative coccobacillus produces a variety of virulence factors that contribute to its adherence to the respiratory epithelium. Recently we described a role for the bacterial virulence factors filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) and fimbriae in the adherence of B. pertussis to two kinds of epithelial cells of the human respiratory tract (39). Other virulence factors such as pertussis toxin (PT) and pertactin (Prn) were not involved in the adhesion of B. pertussis to these human epithelial cells (39). Studies in mice have shown that immunization with purified B. pertussis FHA (34, 43), PT (9, 26, 37), fimbriae (16, 18, 35, 41, 43), or Prn (9, 34) protects against an intranasal or aerosol challenge with B. pertussis. In humans, the presence of antibodies against FHA and fimbriae also seems to correlate with protection against B. pertussis infection and the incidence of whooping cough (4, 6, 14, 24). Together, these studies may imply that antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors interfere with adherence of the bacteria to the respiratory tract epithelium.

Bordetella parapertussis, a bacterium closely related to B. pertussis, also causes pertussis-like symptoms in humans (15, 19, 21, 22, 27, 28, 38). B. parapertussis does not produce PT, but most other virulence factors produced by B. parapertussis, including FHA, fimbriae, and Prn, are homologous to those produced by B. pertussis (1). Various clinical studies, however, found that vaccination with whole-cell pertussis vaccines (WCV) or even infection with B. pertussis does not protect against infection with B. parapertussis (7, 10, 18, 19, 27). Thus, despite the high degree of homology of virulence factors between B. pertussis and B. parapertussis, antibodies against B. pertussis do not prevent B. parapertussis colonization. This finding was confirmed by animal studies which showed limited or no cross-protection against B. parapertussis (18, 41).

In most countries, protection against whooping cough is based on the use of WCV containing heat-killed B. pertussis. Alternatively, acellular vaccines with various combinations of purified and detoxified PT and other B. pertussis virulence factors, such as FHA, Prn, and fimbriae, have been developed and in some countries used instead of WCV. However, it is not known how antibodies induced by components of acellular vaccines confer protection and to what extent they also protect against B. parapertussis.

In the present study, we investigated whether antibodies elicited in mice against purified B. pertussis virulence factors affected the adherence of B. pertussis to the human bronchial epithelial cell line NCI-H292; antibodies against WCV served as controls. Furthermore, we studied whether these antibodies cross-reacted with B. parapertussis and affected the adherence of the bacteria to bronchial epithelial cells as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and purified bacterial proteins.

Strains used in this study were B. pertussis Tohama I (36) and B. parapertussis B24 (25), both human clinical isolates. The B. parapertussis isolate is a typical strain as determined by serology at the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (Bilthoven, The Netherlands). Bacteria were cultured for 2 days on Bordet-Gengou agar plates (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 15% sheep blood. Before use, bacteria were harvested and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). The number of bacteria was determined with a spectrophotometer at 600 nm and then adjusted to 108 CFU/ml in HAP medium (PBS containing 3 mM glucose, 150 nM CaCl2, 500 nM MgCl2, 0.3 U of aprotinin per ml, and 0.05% [wt/vol] human serum albumin). The number of bacteria was confirmed by colony counts after plating on Bordet-Gengou agar.

Purified native B. pertussis fimbriae used in this study were kindly provided by A. Robinson (Centre for Applied Microbiology & Research, Porton Down, United Kingdom); purified native B. pertussis FHA and Prn and genetically detoxified PT (PTg) were kindly provided by R. Rappuoli (Biocine SpA, Siena, Italy). WCV and tetanus toxoid (TT) were obtained from the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment.

FITC labeling of bacteria.

B. pertussis and B. parapertussis were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) as described previously (13, 42). Briefly, bacteria (108/ml) were incubated in a solution of 1 mg of FITC per ml, 50 mM sodium carbonate, and 100 mM NaCl (pH 9.0) for 20 min at room temperature, washed four times to remove excess FITC, and resuspended in HAP medium to a final concentration of 108/ml. The bacteria were kept for 30 min at 37°C until use. This procedure had no effect on either the viability of the bacteria or the binding sites of virulence factors involved in adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells (39).

Cells.

The human bronchial epithelial cell line NCI-H292 (CRL-1848; American Tissue Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) (5) was used. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing sodium penicillin G (1,000 U/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco) in uncoated tissue culture flasks (Greiner Labortechnik, Frickenhausen, Germany). Before use in the adherence assay, NCI-H292 cells were detached with 1 mM EDTA in PBS at 37°C for 5 min and washed, and 5 × 103 cells per well in protein-free medium (Ultradoma-PF; Boehringer Ingelheim/Biowhittaker, Verviers, France) supplemented with sodium penicillin G (1,000 U/ml) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) were cultured overnight on Terasaki plates (Greiner Labortechnik).

Preparation of mouse sera against B. pertussis virulence factors.

Specific-pathogen-free mice (BALB/c/RIVM) were used and kept in protective isolators. The mice were routinely checked according to standard operating protocols at the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment for infection with a large number of pathogens, including gram-negative bacteria such as Bordetella bronchiseptica, Klebsiella pneumoniae, members of the family Pasteurellaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella sp., and Yersinia enterocolitica. On days 0 and 28, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 5 μg of purified B. pertussis FHA, PTg, fimbriae, or Prn, each adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (25% Alu-Gel-S; Serva, Heidelberg, Germany), in PBS. Control mice were immunized with TT (5 μg/ml) adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (25% Alu-Gel-S) in PBS or with aluminum hydroxide (25% Alu-Gel-S) in PBS. Two weeks after the second immunization, sera of 10 mice were collected and pooled.

In addition, mice were immunized subcutaneously at days 0 and 14 with 3.2 opacity units of WCV adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (25% Alu-Gel-S) in PBS. Two weeks after the second immunization, serum was collected.

Before use, sera were incubated for 30 min at 56°C to inactivate complement. B. pertussis-specific antibody titers were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described by Willems et al. (40), with modifications. Polysorp 96-well plates (Nalgene Nunc International, Rochester, N.Y.) were coated with 5 μg of B. pertussis antigen FHA, PTg, fimbriae, or Prn per ml or coated with 0.5 opacity units of WCV per ml in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated overnight at 37°C. After washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the plates were incubated with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 h at 37°C to reduce nonspecific binding. Next, serial dilutions of mouse immune sera were added, and the plates were incubated for 90 min at 37°C and then washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. The various immunoglobulin subclasses were determined by incubation for 1 h at 37°C with corresponding peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, or IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc. [SBA], Birmingham, Ala.). Finally, 100 μl of the peroxidase substrate 3,3,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (0.4 mM; Sigma-Aldrich Chemie bv, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) and H2O2 (0.003%) in 110 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) was added and allowed to develop for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 2 M H2SO4 (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and absorbance was determined at an optical density of 450 nm. Values of endpoint titration curves are given as the reciprocal of the highest dilution corresponding with three times the blank value and expressed as −log10.

Concentrations of immunoglobulin subclasses of the antibodies in the mouse sera were determined by ELISA as described above except that the plates were coated overnight with 5 μg of goat anti-mouse IgG, IgA, or IgM (Cappel Research Products, Durham, N.C.) per ml in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 4°C. The various subclasses were detected using corresponding peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgA, or IgM (SBA). The total concentration of immunoglobulin subclasses in mouse sera were determined by using purified IgG, IgA, or IgM (SBA) as the standard.

MAbs.

The following monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against B. pertussis surface proteins were used as ascites fluid: 4-37F3 (IgG1; 6.9 mg/ml) against B. pertussis FHA (31), 36G3 (IgG1, 1.9 mg/ml) against B. pertussis lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (31), and 30E5 (IgG2b, 14.5 mg/ml) against B. pertussis 40-kDa outer membrane porin protein (OMP) (31) (all kindly provided by J. Poolman, National Institute of Public Health and the Environment, The Netherlands). The MAbs were used in a final concentration of 2 μg/ml.

Binding of MAbs to B. pertussis and B. parapertussis was determined by ELISA as described for antibodies in mouse serum except that the plates were coated overnight with 5 × 106 heat-killed B. pertussis or B. parapertussis per ml suspended in a 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 37°C. Values of endpoint titration curves are given as the reciprocal of the highest dilution corresponding with three times the blank value and expressed as −log10.

Adherence assay.

Adherence of the bacteria to the surface of cultured NCI-H292 cells was assessed as described previously (39), with some minor modifications. Overnight cultures on Terasaki plates containing 5 × 103 cells per well were washed three times with warm PBS. Next, 5 × 105 FITC-labeled bacteria in HAP medium were added to each well and incubated in the presence of various polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies for 45 min at 37°C. After five washes with warm PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria, the plates were fixed for 15 min with 0.05% glutaraldehyde (Polyscience Inc., Warrington, Pa.). After two additional washes with PBS at room temperature, the plates were examined with fluorescence microscopy at a magnification of ×400. The number of bacteria adherent to 100 cells was determined. In other experiments, B. pertussis and B. parapertussis were preincubated with 1% mouse immune serum for 30 min at 37°C at 4 rpm. After three washes, the binding of bacteria coated with antiserum to epithelial cells was assessed as described above. All immune sera and MAbs used did not agglutinate the bacteria in the concentrations used in the different assays (data not shown).

Statistical analysis.

Differences between the results of the various experiments were evaluated by means of analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test.

RESULTS

Antibody response against B. pertussis virulence factors or B. pertussis WCV.

Sera of mice immunized with purified B. pertussis virulence factors FHA, PTg, fimbriae, and Prn showed similar titers of antigen-specific antibodies (Table 1); no cross-reacting antibodies were found against the other purified components (data not shown). In sera of mice immunized with WCV, the antibody titer for WCV used as antigen was comparable to the titers of antigen-specific antibodies in sera of mice immunized with purified virulence factors (Table 1). In the sera obtained after WCV vaccination, the antibody titers against FHA, Prn, and fimbriae were −log10 5.8, −log10 5.4, and −log10 4.5, respectively; no antibody against PTg was detected. Sera of immunized mice contained considerably higher amounts of IgG and IgM, but not of IgA, compared to normal mouse serum (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antigen-specific antibody titers and immunoglobulin concentrations in mouse serum against various B. pertussis virulence factors or WCVa

| Sample | Mean antigen-specific antibody titerb (−log10) ± SD | Mean concn (μg/ml) ± SD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgA | IgM | ||

| Normal mouse serum | ND | 196 ± 14 | 21 ± 18 | 335 ± 49 |

| Serum of mice immunized with: | ||||

| FHA | 6.1 ± 0.35 | 3,340 ± 420 | 15 ± 11 | 1,180 ± 28 |

| PTg | 5.7 ± 0.37 | 3,162 ± 354 | 12 ± 10 | 1,190 ± 41 |

| Fimbriae | 6.0 ± 0.89 | 3,162 ± 382 | 9 ± 6 | 795 ± 37 |

| Prn | 6.1 ± 0.85 | 4,639 ± 402 | 8 ± 6 | 1,220 ± 31 |

| WCV | 6.0 ± 0.32c | 3,180 ± 354 | 18 ± 11 | 530 ± 13 |

Mice were immunized as described in Materials and Methods. Pooled serum from 10 mice was used, and antigen-specific antibody titers and concentrations of total immunoglobulins were detected by ELISA.

Specific for homologous antigens in ELISA; reciprocal of the highest dilution corresponding with three times the blank value. ND, not determined.

WCV used as antigen in ELISA.

Inhibition of adherence of B. pertussis to NCI-H292 cells by anti-B. pertussis mouse sera.

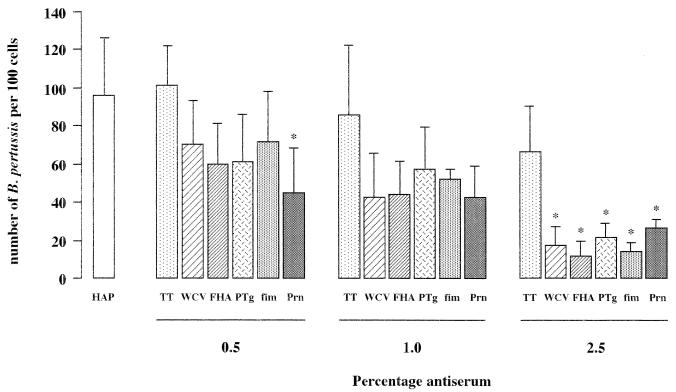

The effect of anti-B. pertussis antibodies on the adherence of B. pertussis to NCI-H292 cells was studied by incubation of bacteria with epithelial cells in the presence of immune sera or anti-TT serum, which served as a control. Immune serum against FHA, PTg, fimbriae, Prn, or WCV reduced the adherence of B. pertussis to NCI-H292 cells (Fig. 1). The inhibition of adherence was concentration dependent and reached significance (P < 0.05) with 2.5% serum in comparison to the same concentration of anti-TT serum. Both anti-TT serum (Fig. 1). and normal mouse serum (data not shown) also reduced adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells, although not significantly.

FIG. 1.

Effects of antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors on adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells. Adherence was determined in the presence of various concentrations of control anti-TT serum (TT), serum with antibodies against WCV, FHA, PTg, fimbriae (fim), or Prn, or HAP medium alone (HAP). Values are the mean ± SD of at least four separate experiments. Difference in adherence of B. pertussis in the presence of various concentrations of antiserum compared to the equivalent concentration of anti-TT serum was determined by ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test: *, P < 0.05 versus anti-TT serum.

For convenience, the effect of antibodies on the adherence of B. pertussis is expressed as the number of B. pertussis to 100 epithelial cells (Fig. 1). However, this value is derived from the change in the percentage of positive epithelial cells and the number of B. pertussis organisms per positive epithelial cell (Table 2). The results showed that in the presence of 2.5% serum containing antibodies against virulence factors, the percentage of positive cells and the number of B. pertussis organisms per positive cell are lower than in the absence of serum (HAP medium) or anti-TT serum.

TABLE 2.

Effects of antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors on adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cellsa

| Condition | Adherenceb

|

% of positive epithelial cells | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of B. pertussis organisms/100 epithelial cellsb | No. of B. pertussis organisms/100 positive epithelial cellsc | ||

| No serum | 96 ± 29 | 259 ± 33 | 36 ± 8 |

| Serum against: | |||

| TT | 67 ± 21 | 264 ± 25 | 23 ± 5 |

| WCV | 17 ± 10b | 152 ± 34b | 10 ± 4b |

| FHA | 11 ± 7b | 135 ± 22b | 8 ± 4b |

| PTg | 21 ± 6b | 180 ± 16b | 10 ± 2b |

| Fimbriae | 14 ± 4b | 168 ± 46b | 9 ± 1b |

| Prn | 26 ± 4b | 205 ± 9 | 12 ± 2b |

Determined in the presence of 2.5% control anti-TT serum, serum with antibodies against WCV, FHA, PTg, fimbriae, or Prn, or HAP medium only; values are means ± SD of at least four separate experiments.

P < 0.05 versus anti-TT antibodies by ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test.

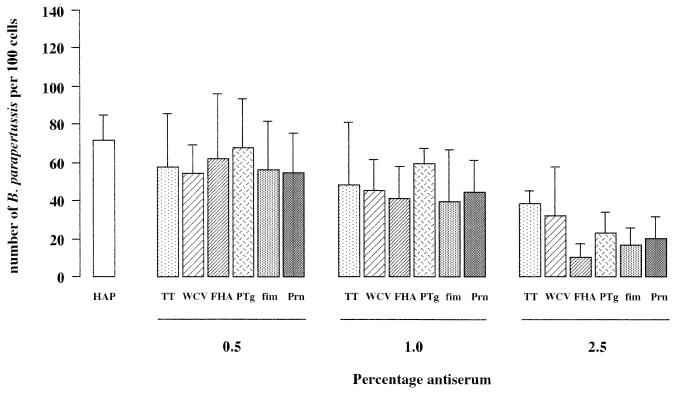

Adherence of B. parapertussis to NCI-H292 cells in the presence anti-B. pertussis mouse sera.

In the absence of serum, adhesion to bronchial epithelial cells of B. parapertussis (Fig. 2) was less than that of B. pertussis (Fig. 1), being 73 ± 13 (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) and 96 ± 29 bacteria/100 epithelial cells, respectively. Antiserum against B. pertussis FHA, PTg, fimbriae, Prn, or WCV did not significantly reduce the adherence of B. parapertussis to the epithelial cells compared to anti-TT serum (Fig. 2). With all mouse sera, including anti-TT serum and normal mouse serum (data not shown), there was a reduced binding of B. parapertussis to NCI-H292 cells, and this effect became greater with increasing concentrations of serum (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effects of antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors on adherence of B. parapertussis to epithelial cells, determined as described for B. pertussis in the legend to Fig. 1.

Adherence of B. pertussis or B. parapertussis preincubated with anti-B. pertussis serum to NCI-H292 cells.

The above-described experiments showed a reduced although not significantly so, adherence of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis to epithelial cells in the presence of anti-TT serum, which was used as a control (Fig. 1 and 2). To examine whether serum factors other than antibodies bound to B. pertussis or B. parapertussis play a role in inhibiting adherence of these bacteria, the bacteria were preincubated with 1% antiserum against B. pertussis FHA, PTg, fimbriae, Prn, WCV, or TT, or with HAP medium lacking serum, and next incubated with NCI-H292 cells. Preincubation of B. pertussis with antiserum against the various B. pertussis virulence factors was found to lead to a 40 to 60% reduction in adherence compared to preincubation with anti-TT serum, which did not affect adherence of bacteria to epithelial cells (Table 3). Preincubation of B. parapertussis with these specific antisera did not affect the adherence of this microorganism (Table 3). These results indicate that the inhibition of binding observed in both immune and anti-TT sera, was not due to binding of serum components other than antibodies to the bacterial surface.

TABLE 3.

Effects of preincubation of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis with antisera against various B. pertussis virulence factors or WCV on the adherence to bronchial epithelial cellsa

| Condition |

B. pertussis

|

B. parapertussis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of bacteria/100 cells | % Inhibitionb | No. of bacteria/100 cells | % Inhibition | |

| No serum | 118 ± 24 | 77 ± 30 | ||

| Serum against: | ||||

| TT | 118 ± 15 | 83 ± 31 | ||

| FHA | 44 ± 17c | 63 | 74 ± 16 | 11 |

| PTg | 64 ± 8c | 46 | 70 ± 18 | 16 |

| Fimbriae | 43 ± 14c | 64 | 84 ± 23 | 0 |

| Prn | 57 ± 26c | 52 | 75 ± 21 | 10 |

| WCV | 75 ± 15c | 36 | 70 ± 5 | 16 |

Bacteria were preincubated with 1% antiserum, after which adherence was determined. Results of a duplicate representative experiment are shown.

Compared to adherence in the presence of anti-TT antibodies.

P < 0.05 versus anti-TT antibodies (control) by ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test.

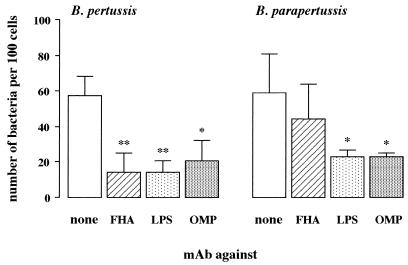

Adherence of B. pertussis or B. parapertussis to NCI-H292 cells in the presence of MAb against B. pertussis FHA, LPS, or 40-kDa OMP.

Antibodies against the various virulence factors of B. pertussis were equally effective in reducing the adherence of these bacteria to epithelial cells. Since these antisera were used in nonagglutinating concentrations (data not shown), the question arose as to whether the observed effect was due either to blocking of the interaction of the adhesin with its receptor or to steric hindrance. Both LPS and the 40-kDa OMP are abundantly present on the surface of virulent- as well as avirulent-phase B. pertussis and B. parapertussis (2, 3, 8, 11, 29), but these surface antigens are not implicated in the adherence of B. pertussis to respiratory epithelial cells (39). Using an ELISA technique, we found that both B. pertussis and B. parapertussis bound MAb against LPS or 40-kDa OMP, whereas B. pertussis but not B. parapertussis bound MAb against FHA (Table 4). Adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells in the presence of MAb against FHA, LPS, or 40-kDa OMP was significantly lower than in the presence of HAP medium; adherence of B. parapertussis in the presence of MAb against LPS or 40-kDa OMP was also significantly reduced, but MAb against FHA had no such effect (Fig. 3).

TABLE 4.

Antibody responses of MAbs against B. pertussis surface antigens to B. pertussis and B. parapertussisa

| MAb against: | Clone | Isotype | Antibody titerb (−log10)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. pertussis | B. parapertussis | |||

| FHA | 37F3 | IgG1 | 5.6 | <LD |

| LPS | 36G3 | IgG1 | 5.8 | 3.5 |

| 40-kDa OMP | 30E5 | IgG2b | 6.5 | 4.9 |

Bacteria were coated onto microtiter plates, and binding of the indicated MAbs was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Reciprocal of the highest dilution corresponding with three times the blank value. <LD, below the level of detection.

FIG. 3.

Effects of MAbs against B. pertussis surface antigens FHA, LPS, and the 40-kDa OMP on adherence of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis to epithelial cells. Adherence was determined in the presence of MAb against FHA, LPS, or 40-kDa OMP or of HAP medium alone (none). Values are the mean ± SD of at least five separate experiments. Difference in adherence of bacteria in the presence of various MAbs compared to medium alone was determined by ANOVA and Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 versus HAP medium.

DISCUSSION

The major conclusions of this study are that antibodies against the B. pertussis virulence factors FHA, PTg, fimbriae, and Prn inhibited adherence of B. pertussis but not of B. parapertussis to human bronchial epithelial cells. The adherence of both B. pertussis and B. parapertussis was inhibited by antibodies against LPS and the 40-kDa OMP of B. pertussis.

Various reports have shown in a murine infection model complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in the protection against B. pertussis (23, 30, 33). In these publications, it has been suggested that cell-mediated immunity against intracellular B. pertussis provides optimum protection and rapid elimination of bacteria from the lungs. However, another important function of cellular immunity is the regulation of antibody production by T cells, which is necessary for limiting the infection by preventing initial bacterial adherence to respiratory epithelial cells, neutralization of bacterial toxins, and optimal removal of extracellular bacteria through opsonization (23).

Our results, which showed that antibodies raised against the B. pertussis virulence factors FHA, PTg, fimbriae, and Prn reduced the adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells, are in agreement with the protective role of antibodies for a B. pertussis infection in mice, immunized with either FHA (9, 34, 43), PT (9, 26, 37), fimbriae (16, 17, 35, 41, 43), or Prn (9, 34). In addition, the reduced adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells may indicate that such antibodies present in serum of children vaccinated with WCV or recovered from whooping cough (4, 6, 14, 24) are relevant for the protection against a B. pertussis infection as well.

We found that antisera against individual virulence factors were equally effective in inhibiting adherence of B. pertussis to bronchial epithelial cells. Furthermore, antiserum against WCV, which contains antibodies against, among others, FHA, fimbriae, and Prn, was not more effective in reducing the adherence of B. pertussis to epithelial cells. Analysis of our data showed that not only the number of B. pertussis organisms per positive bronchial epithelial cell but also the percentage of positive epithelial cells was reduced. Since all sera contained comparable antigen-specific antibody titers and the concentrations of total immunoglobulins were similar, our data suggest that the combinations of antibodies against the various factors present in antiserum against WCV act additively in inhibiting adherence.

In another study, we demonstrated that only FHA is involved in the adherence of B. pertussis to bronchial epithelial cells (39). Since antibodies against PTg, Prn, and fimbriae, which are not involved in the adherence of B. pertussis to bronchial epithelial cells (39), and even antibodies against LPS and the 40-kDa OMP reduced the adherence of B. pertussis to these epithelial cells, our results indicate that antibodies against surface structures of B. pertussis other than adhesion factors can interfere with bacterial adherence.

Anti-TT serum or normal mouse serum also reduced the adherence of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis to epithelial cells, which indicates that under the experimental conditions used, serum factors other than antibodies against virulence factors interfere with adherence. Fibronectin, which is a major serum component, may account for this effect, since in a preliminary experiment the adhesion of B. pertussis to bronchial epithelial cells was inhibited about 44% by the presence of fibronectin. An equivalent concentration of collagen had no such effect. Preincubation of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis with anti-TT serum did not reduce the adherence of these bacteria to bronchial epithelial cells, which suggests that fibronectin may block the host receptors and thus prevent adherence of the bacteria. In this regard, it is interesting that fibronectin and fimbriae of B. pertussis can bind to similar receptors and have similar binding specificities (12).

The adherence of B. parapertussis to bronchial epithelial cells was not inhibited by antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors, although a nonsignificant effect was observed in the presence of 2.5% anti-FHA serum. This may explain why mice immunized with purified pertussis toxoid, FHA, or Prn are not protected against infection with B. parapertussis (18), although some protection against B. parapertussis was obtained by immunization with WCV or purified fimbriae (41).

MAbs against B. pertussis LPS and the 40-kDa OMP bound to both B. pertussis and B. parapertussis and inhibited their adherence to epithelial cells. These data suggest that LPS, which contains very conserved regions located at the proximal and intermediate regions near the lipid A part (8, 20), may elicit antibodies that are cross-protective between the two Bordetella species. This is in agreement with the finding that the 40-kDa OMP, which is also very conserved between various Bordetella species (2, 3), can elicit cross-protective antibodies after appropriate presentation (32). However, antiserum from WCV-immunized mice, which most likely also contains antibodies against LPS and 40-kDa OMP, did not reduce adherence of B. parapertussis to epithelial cells, possibly because low titers of antibodies against epitopes of both LPS and 40-kDa OMP were generated in sera of mice immunized with WCV. Similarly, low titers of these antibodies against LPS and 40-kDa OMP may be present in humans vaccinated with WCV, which could explain why immunization with this vaccine failed to protect against B. parapertussis (7, 10, 19, 27).

Together, our data imply that the present pertussis vaccines may not be effective against B. parapertussis. However, cross-protection can be improved by incorporating surface molecules such as the 40-kDa OMP in these vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to Rob Willems for helpful discussions.

This work was financially supported by Preaventie Fonds grant 2825450.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arico B, Gross R, Smida J, Rappuoli R. Evolutionary relationships in the genus Bordetella. Mol Microbiol. 1987;1:301–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong S K, Parker C D. Heat-modifiable envelope proteins of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1986;54:109–117. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.109-117.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong S K, Parker C D. Surface proteins of Bordetella pertussis: comparison of virulent strains and effects of phenotypic modulation. Infect Immun. 1986;54:308–314. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.308-314.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashworth L A E, Robinson A, Irons L I, Morgan C P, Isaacs D. Antigens in whooping cough vaccine and antibody levels induced by vaccination of children. Lancet. 1983;ii:878–881. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90869-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks-Schlegel S P, Gazdar A F, Harris C C. Intermediate filament and cross-linked envelope expression in human lung tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1187–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumberg D A, Pineda E, Cherry J D, Caruso A, Scott J V. The agglutinin response to whole-cell and acellular pertussis vaccines is Bordetella pertussis-strain dependent. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:1148–1150. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160220034016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borska K, Simkovicova M. Studies on the circulation of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis in populations of children. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1972;16:159–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodeur B R, Martin D, Hamel J, Shahin R D, Laferrière C. Antigenic analysis of the saccharide moiety of the lipooligosaccharide of Bordetella pertussis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1993;15:205–215. doi: 10.1007/BF00201101. . (Review.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capiau C, Carr S A, Hemling M E, Plainchamp D, Conrath K, Hausser P, Simoen E, Comberbach M, Roelants P, Desmons P, Permanne P, Pétre J O. Purification, characterization, and immunological evaluation of the 69-kDa outer membrane protein of Bordetella pertussis. In: Manclark C R, editor. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Pertussis. DHHS publication no. (FDA) 90-1164. Bethesda, Md: Department of Health and Human Services; 1990. pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donchev D, Stoyanova M. The epidemiological significance of the differentiation of pertussis and parapertussis. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1961;5:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank D W, Parker C D. Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to Bordetella pertussis. J Biol Stand. 1984;12:353–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-1157(84)80060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geuijen C A W, Willems R J L, Bongaerts M, Top J, Gielen H, Mooi F R. Role of the Bordetella pertussis minor fimbrial subunit, FimD, in colonization of the mouse respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4222–4228. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4222-4228.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazenbos W L W, van den Berg B M, van’t Wout J W, Mooi F R, van Furth R. Virulence factors determine attachment and ingestion of nonopsonized and opsonized Bordetella pertussis by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4818–4824. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4818-4824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Q, Viljanen M K, Olander R, Bogaerts H, De Grave D, Ruuskanen O, Mertsola J. Antibodies to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis and protection against whooping cough in schoolchildren. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:705–708. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heininger U, Stehr K, Schmitt-Grohe S, Lorenz C, Rost R, Christenson P D, Uberall M, Cherry J D. Clinical characteristics of illness caused by Bordetella parapertussis compared with illness caused by Bordetella pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:306–309. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones D H, McBride B W, Jeffery H, O’Hagan D T, Robinson A, Farrar G H. Protection of mice from Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection using microencapsulated pertussis fimbriae. Vaccine. 1995;13:675–681. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)99876-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones D H, McBride B W, Thornton C, O’Hagan D T, Robinson A, Farrar G H. Orally administered microencapsulated Bordetella pertussis fimbriae protect mice from B. pertussis respiratory infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:489–494. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.489-494.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khelef N, Danve B, Quentin-Millet M-J, Guiso N. Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis: two immunologically distinct species. Infect Immun. 1993;61:486–490. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.486-490.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lautrop H. Epidemics of parapertussis: 20 years’ observations in Denmark. Lancet. 1971;i:1195–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Blay K, Caroff M, Blanchard F, Perry M B, Chaby R. Epitopes of Bordetella pertussis lipopolysaccharides as potential markers for typing of isolates with monoclonal antibodies. Microbiology. 1996;142:971–978. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linnenman C C, Jr, Perry E B. Bordetella parapertussis: recent experience and a review of the literature. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:560–563. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120180074014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mertsola J. Mixed outbreak of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis infection in Finland. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1985;4:123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02013576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills K H G, Ryan M, Ryan E, Mahon B P. A murine model in which protection correlates with pertussis vaccine efficacy in children reveals complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection against Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:594–602. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.594-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mink C M, O’Brien C H, Wassilak S, Deforest A, Meade B D. Isotype and antigen specificity of pertussis agglutinins following whole-cell pertussis vaccination and infection with Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1118–1120. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1118-1120.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mooi F R, van der Heide H G J, ter Avest A R, Welinder K G, Livey I, van der Zeijst B A M, Gaastra W. Characterization of fimbrial subunits from Bordetella species. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:473–484. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morokuma K, Ginnaga A, Nishihara T, Shunsei T, Furukawa M, Aihara K, Sakoh M. Comparison of the protective effects of the pertussis acellular vaccine with the component vaccine which have different amounts of fimbriae, against the experimental aerosol infection of mice with Bordetella pertussis. Dev Biol Stand. 1990;73:223–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neimark F M, Lugovaya L V, Belova N D. Bordetella parapertussis and its significance in the incidence of pertussis. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1961;32:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novotny P. Pathogenesis in Bordetella species. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:581–582. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parton R, Wardlaw A C. Cell-envelope proteins of Bordetella pertussis. J Med Microbiol. 1975;8:47–57. doi: 10.1099/00222615-8-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen J W, Andersen P, Ibsen P H, Capiau C, Wachmann C H, Hasløv K, Heron I. Proliferative responses to purified and fractionated Bordetella pertussis antigens in mice immunized with whole-cell pertussis vaccine. Vaccine. 1993;11:463–472. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90289-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poolman J T, Kuipers B, Vogel M L, Hamstra H-J, Nagel J. Description of a hybridoma bank towards Bordetella pertussis toxin and surface antigens. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:377–382. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90024-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poolman J T, Hamstra H J, Barlow A K, Kuipers B, Loggen H, Nagel J. Outer membrane vesicles of Bordetella pertussis are protective antigens in the mouse intracerebral challenge model. In: Manclark C R, editor. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Pertussis. DHHS publication no. (FDA) 90-1164. Bethesda: Department of Health and Human Services; 1990. pp. 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redhead K, Watkins J, Barnard A, Mills K H. Effective immunization against Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in mice is dependent on induction of cell-mediated immunity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3190–3198. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3190-3198.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts M, Cropley I, Chatfield S, Dougan G. Protection of mice against respiratory Bordetella pertussis infection by intranasal immunization with P.69 and FHA. Vaccine. 1993;11:866–872. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson A, Gorringe A R, Funnel S G P, Fernandez M. Serospecific protection of mice against intranasal infection with Bordetella pertussis. Vaccine. 1989;7:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(89)90193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato Y, Aria H. Leukocytosis-promoting factor of Bordetella pertussis. I. Purification and characterization. Infect Immun. 1972;6:899–904. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.6.899-904.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahin R D, Witvliet M H, Manclark C R. Mechanism of pertussis toxin B oligomer-mediated protection against Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58:4063–4068. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4063-4068.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taranger J, Trollfors B, Lagergard T, Zackrisson G. Parapertussis infection followed by pertussis infection. Lancet. 1994;344:1703. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Berg B M, Beekhuizen H, Willems R J L, Mooi F R, van Furth R. Role of Bordetella pertussis virulence factors in adherence to epithelial cell lines derived from the human respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1056–1062. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1056-1062.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willems R, Paul A, van der Heide H G J, ter Avest A R, Mooi F R. Fimbrial phase variation in Bordetella pertussis: a novel mechanism for transcriptional regulation. EMBO J. 1990;9:2803–2809. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willems R J L, Kamerbeek J, Geuijen C A W, Top J, Gielen H, Gaastra W, Mooi F R. The efficacy of a whole cell pertussis vaccine and fimbriae against Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis infections in a respiratory mouse model. Vaccine. 1998;16:410–416. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)80919-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright S D, Jong M T C. Adhesion-promoting receptors on human macrophages recognize Escherichia coli by binding to lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1986;164:1876–1888. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.6.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J M, Cowell J L, Steven A C, Manclark C R. Purification of serotype 2 fimbriae of Bordetella pertussis and their identification as a mouse protective antigen. Dev Biol Stand. 1985;61:173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]