Abstract

Background:

The Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative set a goal to virtually eliminate new HIV infections in the US by 2030. The plan is predicated on the fact that tools exist for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment and the current scientific challenge is how to implement them effectively and with equity. Implementation research (IR) can help identify strategies that support effective implementation of HIV services.

Setting:

NIH funded the Implementation Science Coordination Initiative (ISCI) to support rigorous and actionable IR by providing technical assistance to NIH-funded projects and supporting local implementation knowledge becoming generalizable knowledge.

Methods:

We describe the formation of ISCI, the services it provided to the HIV field, and data it collected from 147 NIH-funded studies. We also provide an overview of this supplement issue as a dissemination strategy for HIV IR.

Conclusion:

Our ability to reach EHE 2030 goals is strengthened by the knowledge compiled in this supplement, the services of ISCI and connected hubs, and a myriad of investigators and implementation partners collaborating to better understand what is needed to effectively implement the many evidence-based HIV interventions at our disposal.

Keywords: Implementation science, implementation research, Ending the HIV Epidemic, research coordination

The Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative, launched in 2019, set a goal to end the HIV epidemic in the United States by the year 2030.1 The idea of achieving this ambitious and unprecedented goal was predicated on decades of scientific discovery delivering the necessary tools: highly sensitive tests to diagnose HIV infection, effective interventions to prevent and treat infection, and cutting-edge technologies to identify outbreaks. While effective interventions are necessary, ultimate success can only be achieved if they are sufficiently implemented in ways that meet individual, community, and health care delivery system needs. Indeed, implementation of these interventions is the major scientific and programmatic challenge to ending the HIV epidemic in the US. The continuum of care provides a salient example of this; despite highly effective HIV treatments only about half (56.8%) of Americans living with HIV were diagnosed, received care, and achieved viral suppression in 2019,2 which both provides life-saving benefits and reduces forward transmission. Testing is the entry to care, and while penetration of testing has been high among adults, it lags considerably among other high-priority populations such as teen men who have sex with men (32% ever tested,3 44.3% are unaware of an HIV positive status4). The most recent data published from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System documents low levels of PreP uptake in the most impacted populations (1% among persons who inject drugs;5 25% MSM;6 0.4% among heterosexuals at increased risk;7 32% among transgender women8).

Over the past decade there has been a growing realization that solutions to these challenges might come from the field of implementation science (IS),9–14 and the conduct of implementation research (IR), which was enshrined as a key component of the multi-agency EHE initiative.1,15 While “implementation” is used in many different ways (e.g., “implementing an intervention”), IR is defined by the National institutes of Health (NIH)16 as the scientific study of the use of strategies to promote the systematic uptake of evidence-based practices into route clinical and public health practice, and is recognized as a distinct component of the translational pipeline17. More broadly, IS is a field of study focused on methods to promote the integration of research findings and evidence into healthcare policy and practice.

This supplemental issue of JAIDS is dedicated to describing the multiagency EHE initiative, reporting results from domestic IR studies to inform EHE efforts, and commenting on some of the anticipated challenges. The supplement issue was organized by the leaders of the NIH-funded Implementation Science Coordination Initiative (ISCI) housed at the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (all co-authors herein). In this article we describe the history and need that led to the formation of ISCI as well as the activities it has undertaken with numerous partners toward its two overarching goals: (1) support rigorous and actionable IR by providing technical assistance from experts on IS designs, frameworks, strategies, measures, and outcomes and (2) create opportunities for local knowledge to become generalizable knowledge by encouraging the use of shared frameworks, harmonization of measures, cross-study collaboration, and synthesis of findings across studies. We next describe future directions of ISCI (e.g., supporting multisite IR) as it evolves to encompass broader opportunities to produce generalizable knowledge from domestic IR toward the ultimate goal of identifying and disseminating effective implementation strategies that will help us reach the end of the HIV epidemic.

Formation of an HIV implementation science coordination initiative

The role of the multi-institute NIH-funded Centers for AIDS Research (CFARs) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded AIDS Research Centers (ARCs) is to form research-practice partnerships with health departments, community organizations, and health systems to study innovations in implementation of HIV services to end the HIV epidemic.1 This approach grew from the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Plan (ECHPP) project.15 ECHHP was a partnership among multiple federal agencies that funded the 12 cities with the highest burden of HIV in order to strategically plan how to best use their prevention and care resources to reduce HIV and reduce health disparities.18 CFARs and ARCs were funded to support research and provide technical assistance to their Departments of Health (DOH) for local program planning and implementation of ECHPP activities, which resulted in these centers forming and enriching partnerships with their local health departments and set the stage for the growth of domestic HIV IS as an NIH-funded area of research (as documented in 3 prior JAIDS supplement issues).19–21

When ECHPP ended, discussions continued among CFAR leaders about how to build on this momentum and build better connections to the emerging field of IS. In 2016, Brian Mustanski, Co-Director of the Third Coast CFAR and Co-Principal Investigator (PI) of the NIDA funded Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology (Ce-PIM) for Drug Abuse and HIV, and Nanette Benbow, Co-Investigator in both Centers, met with CFAR leaders to discuss the formation of an Inter-CFAR working group focused on HIV IS. Alan Greenberg, PI of the Washington DC CFAR and lead of the inter-CFAR ECHPP working group, suggested it could evolve into a working group focused on HIV IS. Recognizing their expertise was in domestic HIV, Benbow and Mustanski invited Stefan Baral (Johns Hopkins University), who has expertise in global HIV, to join as a co-leader of the working group with additional members joining from many CFARs.

The first initiative of the inter-CFAR working group (which included ARCs) was to submit a proposal for a workshop titled, “Catalyzing HIV Implementation Science through Methodological Innovation and Multi-Sector Partnerships,” which was funded as a CFAR supplement. The workshop was planned collaboratively between working group members and federal partners from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and NIH, and held in Chicago in 2018 with participation from representatives of each CFAR/ARC and one or more of their primary implementation stakeholders (e.g., health departments, community-based organizations, health systems) to help assure that service provider perspectives were included from the start. To prepare for the meeting, CFAR/ARC attendees (24% directors, 15% core directors, 61% members) were surveyed, providing data that only 42% of CFAR/ARCs had a core that offers IS services or consultations. Coding of open-ended responses regarding IS challenges indicated there was a lack of faculty with expertise in IS and many expressed a need for training on how to design IR studies and write strong grant proposals. In addition to presentation at the workshop on key HIV IS concepts and exemplar studies (see https://www.thirdcoastcfar.org/imp-sci-april-2018/) attendees participated in structured activities to identify gaps and opportunities in HIV IS. Working group members and federal partners then discussed these outputs and set a charge for the inter-CFAR IS working group, which included the following objectives:

Foster collaborations across CFARs and ARCs that facilitate the development of methodologically strong and cost-effective HIV-related implementation research studies.

Synthesize the state of the art for implementation research methods and prioritize questions in HIV-related implementation science.

Identify challenges and potential solutions to conducting HIV-related implementation research in academic-practice collaborations to address local needs and create generalizable knowledge.

Facilitate and disseminate HIV-related implementation science via an up-to-date list of implementation science trainings and speakers that can support education through conferences, workshops, and a newsletter.

Foster collaborations between CFARs/ARCs and implementation partners to expand implementation research and facilitate multi-site implementation research.

One of the first products of the inter-CFAR IS Working Group was related to goal #2 of synthesizing the state of the field. A mapping review of NIH-funded projects between 2013–2018, found that only a third (36%) of HIV studies that mentioned implementation or IR were actually IR-related. Half of these (18% of total) met the NIH definition of an IR study, that is, they evaluated the effect of implementation strategies. The other half were classified as being in the “implementation preparation” phase as they merely examined implementation barriers and facilitators, identified potential implementation strategies, and/or examined feasibility and acceptability of potential strategies without testing them. Overall, less than 40% of NIH–funded HIV research included in the review was found to be IR-related. Trends in funded HIV IR-related studies during the analysis period showed a small but growing portfolio of NIH-funded research, contributing to our understanding of implementation of HIV interventions.

In FY2019, NIH issued a call for EHE supplements to CFAR and ARC grants for projects that collaborated with community partners to develop locally relevant plans for diagnosing, treating and preventing HIV in areas with high rates of new HIV cases. 65 projects were funded (approximately $11.3 million). As a second output of the inter-CFAR IS working group, the Third Coast CFAR led a collaborative submission to form ISCI with its aims informed by the prior workshop, surveys of CFARs/ARCs, and the scoping review—instantiated as the 3 Cs of Consultation to supplement projects, Coordination of data collection to help local knowledge become generalizable knowledge, and Collaboration across projects so all could quickly benefit from emerging knowledge. The 3 Cs were delivered through several specific activities. In the fall of 2019, we hosted a 2-day summit that included supplement leaders, their primary implementation partners, and representatives from federal agencies responsible for EHE. At the summit, we provided an overview of ISCI services, delivered trainings from experts on key IS concepts relevant to the EHE initiative (e.g., IS frameworks, strategies, outcomes; see http://hivimpsci.northwestern.edu/ for an archive of summit materials and presentations), and initiated coaching to projects on the concepts covered through a network of consultants identified by the inter-CFAR working group. Each project team created an initial Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM) that outlined determinants, strategies, mechanisms, and outcomes.22 Projects were also grouped based on the interventions they were studying to foster collaborations that continued in follow-up virtual meetings throughout the year. The summit model evolved into a National EHE Meeting in subsequent years, with different CFARs taking turns serving as host (Washington DC CFAR in 2021; University of Alabama at Birmingham CFAR in 2022).

Overview of ISCI and IS Hub activities and NIH supported EHE IR studies

The Summit was a kickoff of ISCI but on its own would have been insufficient to provide the learning and teamwork needed to successfully apply IS to the EHE initiative. Early information gathering on the first 65 projects funded in FY2019 indicated few of the HIV researchers reported formal IS training or experience, so there was a great need to provide learning opportunities about models and frameworks, research designs, IS terminology, and measures. In the year following the Summit, ISCI faculty and staff established and curated resources for an online Community of Practice (CoP), through which we continue to disseminate new articles, trainings, webinars, jobs, and funding opportunities. The website has had 4,900+ unique visitors and the newsletter is subscribed to by over 550 HIV researchers and implementers. For example, after an initial inter-CFAR HIV IS reading group was completed, the full curriculum was archived as a tool for universities that may want to initiate their own reading groups. Finally, project teams could request individual coaching sessions from a team of consultants through the CoP on topics such as IS designs, frameworks, implementation strategies, measures, outcomes, and partnership formation.

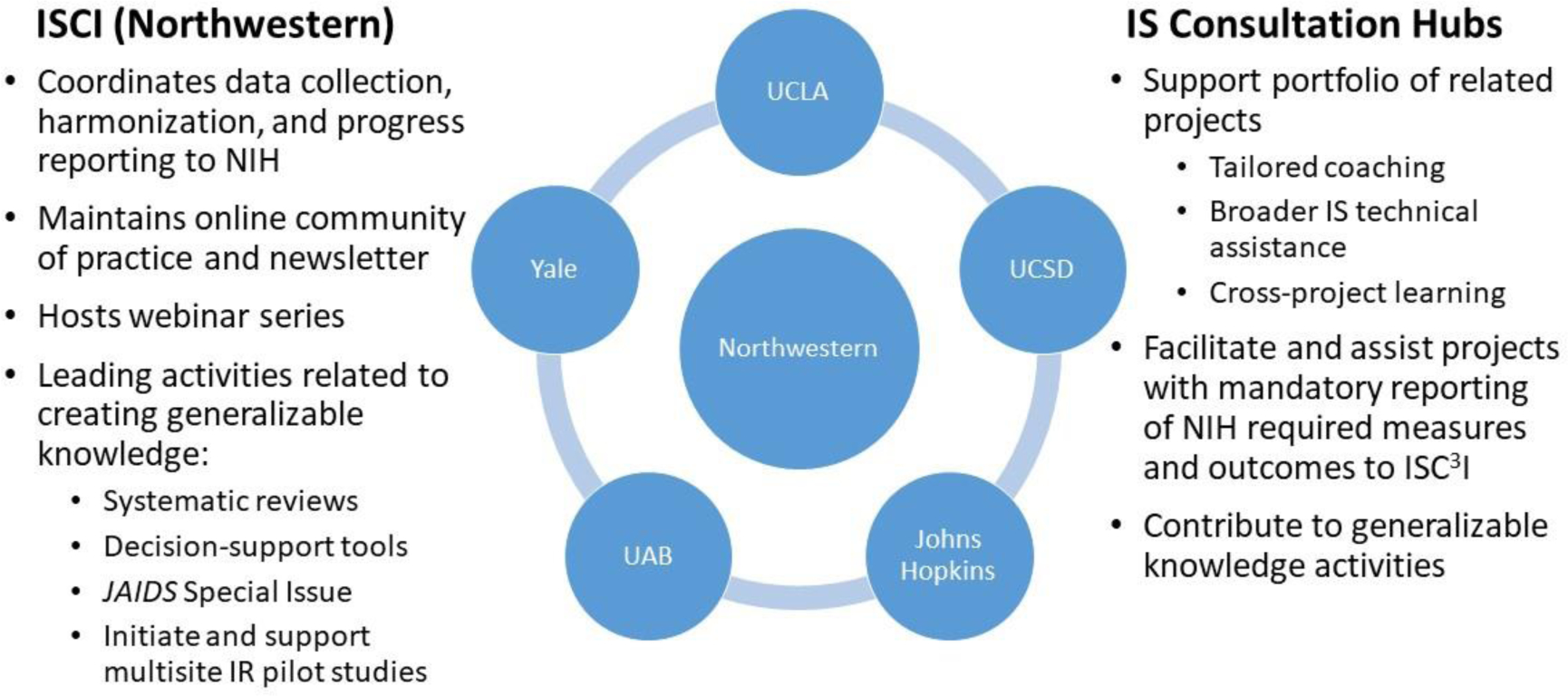

In FY2020, responsibility for the project-facing consultation services shifted to five newly funded IS Hubs that were established at CFARs/ARCs around the US: San Diego CFAR; University of Alabama at Birmingham CFAR; Johns Hopkins University CFAR; the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) at Yale University; and the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) at University of California - Los Angeles. In turn, ISCI was able to focus its efforts more squarely on coordination to further achieve goals #1, 4, and 5 of the inter-CFAR IS working group with the ultimate purpose of creating and disseminating generalizable knowledge to help end the HIV epidemic (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Activities shared across the national coordinating center (ISCI) and the 5 implementation research hubs

Note: ISCI is hosted by the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research at Northwestern University, University of Chicago, and partner organizations. Hubs include: Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) at University of California - Los Angeles; UCSD = San Diego CFAR; Johns Hopkins University CFAR, UAB = University of Alabama at Birmingham CFAR, and the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) at Yale University.

In terms of coordination efforts, ISCI first created and implemented reporting systems to facilitate systematic data collection on the shared determinants, measures, and outcomes across EHE funded projects. With input from HIV IS expert panels, as well as federal agency leaders, ISCI also developed tools that help the field harmonize data being collected to make them more comparable, and by extension, creating opportunities to produce more generalizable knowledge from the EHE supplement projects and beyond. As new tools have been developed, they have been deployed to the CoP; this included facilitation materials for independently completing an IRLM (e.g., fillable PDFs, worksheets, video training) and a crosswalk of implementation outcomes for different stages of HIV IR with supporting materials (e.g., worksheet, video). The IRLM was required in the EHE CFAR/ARC supplement RFAs starting in the second year, and it also has been added as a required component in recent HRSA and CDC EHE-related funding announcements. Moreover, ISCI and the five IS Hubs piloted the implementation outcomes crosswalk (available at http://HIVimpsci.northwestern.edu/) with projects in the second year, making improvements based on project feedback. In the third year, trainings are being conducted on utilization of the Longitudinal Implementation Strategies Tracking System (LISTS) in order to further standardize data collection in EHE-funded HIV IR.23,24

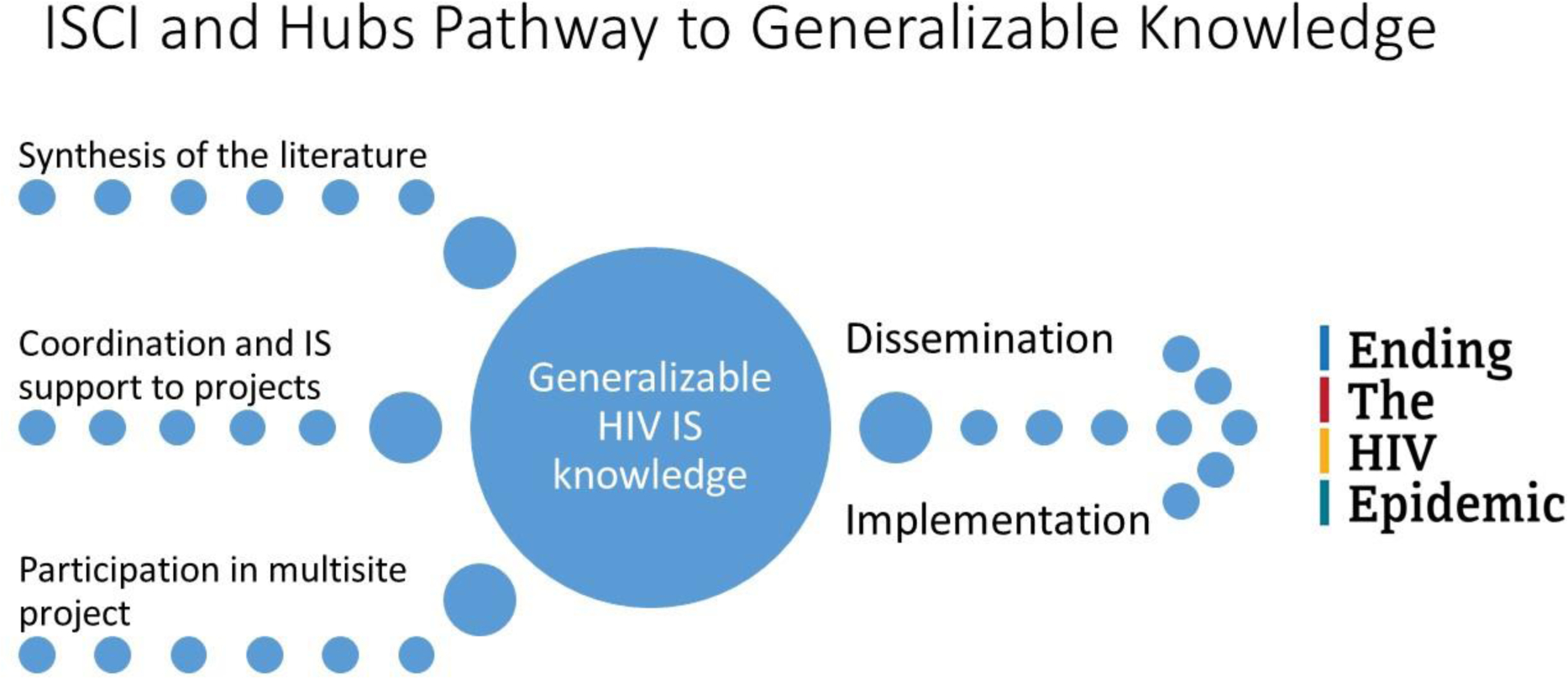

These tools were developed to both facilitate methodologically strong HIV IR and to encourage the collective use of the same measures and outcomes across projects, which created opportunities for cross-project analyses. With support from the IS Hubs, all of these coordination activities have culminated in the development of a model (see figure 2) that identified research pathways that will support generalizable implementation knowledge (i.e., NIH’s role in EHE) and a vision for how to disseminate that knowledge to service providers in collaboration with federal agencies that support service delivery (CDC and HRSA).

Figure 2:

Pathways from ISCI and hub activities to generalizable knowledge to dissemination and implementation of learning to support ending the HIV epidemic.

To further synthesize general and HIV-specific IS knowledge to improve the integration and standardization of IS models and frameworks in HIV research and to identify promising implementation strategies that work in particular settings, we are conducting structured literature reviews and consultations with HIV IS experts and practitioners (Input 1). One example of this is the scoping review of facilitators and barriers to PrEP implementation by Li et al.25 in this JAIDS special issue. Other reviews are being conducted on determinants of HIV testing and treatment implementation as well as implementation strategies for all pillars. The data from these reviews will be made publicly available in a searchable database (see http://hivimpsci.northwestern.edu/). Identification of promising implementation strategies from the literature will serve as an input into a longer-term plan of creating a compendium of effective implementation strategies for EHE interventions.

To facilitate dissemination and use of these findings we will develop decision-support tools, and other dissemination materials aimed at helping HIV researchers select appropriate IS outcomes, frameworks, and strategies for future studies (Input 2). As one example, we will draw from findings from scoping reviews to serve as the empirical backbone for an interactive tool for matching HIV-specific determinants to strategies.

While single site implementation studies can help inform local service delivery knowledge, to complete the pathway to producing generalizable knowledge, multisite HIV IR projects are needed to inform best practices and achieve EHE targets and identify what works where and for whom (input 3). To this end, ISCI and the IS hubs are piloting infrastructure to serve as a platform for multisite HIV IS research that will help address the inter-CFAR IS working group’s final goal of fostering collaborations between CFARs and implementation partners to expand implementation research and facilitate multi-site implementation research. Work is ongoing to pilot a multisite study of determinants and implementation strategies that will serve as a natural laboratory to develop new measures, identify actionable and meaningful common data elements, establish best practices for IR in HIV, with the aim of creating generalizable knowledge.

All of the generalizable knowledge gained by these 3 inputs will not end the HIV epidemic if it “sits on the shelf” so as generalizable implementation knowledge accumulates, dissemination strategies will then need to be onboarded to support awareness and use of effective implementation strategies within practice settings.

Over the past three years of EHE, ISCI and the Hubs have supported 147 supplement projects, starting with 65 one-year planning projects in the first year. In addition to their focusing on at least one of the 57 EHE Phase 1 priority jurisdictions, a key feature of these grants was that they had to have active engagement from an implementation partner in the project. This requirement reflected the importance and necessity of community engagement in implementation research and has been carried through subsequent years. In the second year, 17 of the 65 supplements were funded for an additional 1 or 2 years to move their projects from planning to early implementation. NIH also funded 17 new planning projects, with 13 focused on topics of special interest: cisgender heterosexual women and data-driven communication strategies. In year 3, 36 more one-year projects were funded, one building on a first-year project and 21 of which are addressing social/structural determinants using intersectional frameworks. The article by Quieroz et al. in this special supplement describes the portfolio of 147 supplement grants in further detail.26

Supporting collaboration across these projects stemmed from the perspective that important scientific work to end the HIV epidemic does not happen in isolation. ISCI coordinated consistent monthly meetings with the five IS Hubs, which has enhanced the technical assistance provided each year and led to new, exciting opportunities to conduct research collectively. ISCI and the IS Hubs have also facilitated virtual peer groups of similar projects to allow researchers to come together, share best practices and seek out opportunities to collaborate. From these groups, researchers not only learned from their colleagues but have joined forces in scientific endeavors when possible. For example, one investigator leading an EHE supplement went on to co-author a grant proposal with Hub leaders they met through the peer group. Moreover, the ISCI editorial team was able to encourage researchers working in similar contexts to come together and write multi-study papers together that appear in this supplement. The seeds have been planted for future collaborations that will transition the field toward the production of generalizable lessons that can be applied in practice to improve HIV-related outcomes and achieve the ambitious public health impact laid out in the EHE plan.

Overview of Articles in this JAIDS supplement

Of the articles included in this supplemental issue of JAIDS, 17 showcase findings from the 1-year FY19 CFAR/ARC supplement projects supported by ISCI’s consultation, coordination and collaboration activities. An additional 10 describe other domestic HIV IR studies. The articles represent a significant degree of geographic diversity with 7 sharing results from projects in the Northeast, 5 from the South, 3 from the West, 2 from the Midwest, 3 that combine data coming from multiple regions, and 7 with a nationwide scope. Regarding EHE pillar, 1 project focuses on the Diagnose Pillar, 6 on the Treat Pillar, 8 on the Prevent Pillar, and 12 span multiple pillars. Most projects report research with a general, diverse population of people living with HIV or population at-risk of acquiring HIV; however, a select group focus on priority populations: 1 on adolescents; 3 on men who have sex with men (MSM); 3 on cisgender women, and 5 on racial and ethnic minority populations. In line with the nature of the 1-year pilot funding, 9 articles focus primarily on identifying barriers and facilitators, and 10 report on the identification and/or pilot testing of implementation strategies. It is important to emphasize the domestic HIV IR relevant to EHE goals is still in its early stages, and the relatively small samples and exploratory nature of many of the projects in this JAIDS supplement reflect that phase of science. With the data collected as part of these planning projects, the researchers leading supplements and the field as a whole are now poised to conduct more sophisticated and larger studies needed to test which strategies will be most effective in improving the implementation of effective HIV interventions.

Lessons learned from the first 3 years of HIV IR relevant to EHE

Our collective efforts to coordinate, consult, and support collaboration among the supplement projects have already made inroads towards EHE goals. We have observed growth in IS competencies among researchers; sustained engagement with our online community of practice/resource repository; and increasing use of our coordination tools in proposals, papers, and other products. Readers will see, for example, a number of articles in this special supplement that present their IRLM. Findings from the projects about determinants of implementation for various HIV interventions are starting to appear in the published literature, including in this special supplement, which will help inform the implementation strategies needed to achieve reductions in HIV transmission and acquisition in different contexts. However, there are also many limitations to the current model of research funding and support. The time (1 year for most, 2 years for some) and resource constraints of the supplements limit the extent to which actual implementation can be studied in multiple sites, often making it infeasible to evaluate implementation strategies or assess important implementation outcomes, such as adoption and reach across a jurisdiction or system. Additionally, even among projects that have similar intervention or population foci, variation in methods, strategies, and/or contexts limits what can be definitively concluded from the synthesis of data and/or findings. To truly identify the best approaches for putting evidence-based HIV interventions into practice in specific contexts, we need to expand the size and scope of coordination and collaborative IR activities to develop generalizable knowledge using rigorous IS methods.

Future Directions

The articles in this special supplement attest to the scientific advances in HIV IR happening in the US, but critical challenges remain to ending the HIV epidemic. As has been noted recently, the interventions needed to end the transmission of HIV are available; yet, their implementation, with equity,27–30 is now the pressing scientific and practical challenge.13,31 While funding for HIV implementation research by the NIH has grown since 2013, it pales in comparison to the continued, tremendous investment in discovery and testing of new HIV prevention, treatment, and testing interventions: Less than 5% of all NIH-funded HIV research is related to IR, and only half of that research formally tests implementation strategies.13 As the field of HIV IS continues to mature, investigators will need to coordinate efforts and utilize rigorous methods to create generalizable knowledge regarding effective implementation strategies for specific delivery contexts and populations affected by the HIV epidemic. Developing generalizable knowledge regarding implementation solutions requires moving beyond simply assessing and understanding determinants of implementation toward a greater focus on the development, selection, and testing of implementation strategies.

To facilitate the generation of research evidence that can contribute to generalizable knowledge, HIV implementation scientists are moving toward the use of common data elements (sets of assessments that experts organized based on subject-specific and topic driven data elements) and shared definitions of implementation process metrics and outcomes. Tools are being developed to assist researchers in the selection and operationalization of outcomes (e.g., the HIV Implementation Outcomes Crosswalk; available on ISCI website) and to formalize data collection on implementation strategy use and modification (the Longitudinal Implementation Strategies Tracking System (LISTS),23,24 among others. The ultimate goal of these efforts is the synthesis of IR evidence, which is currently a nearly impossible task given the fragmentation of the entire field of IS that persists into HIV IS. Synthesis requires both common data elements, or at least comparable assessment methods and operationalization of outcomes and constructs, but also processes to support data sharing across research projects. Data sharing in IR is complicated by the nature of the data we collect (e.g., reliance on qualitative data) and potential concerns from implementation partners regarding proprietary data (e.g., operational or cost/economic data). Formal research consortia, multisite projects with shared study protocols, and national coordinating centers, with compulsory participation by investigators, are structures that can facilitate data sharing and common data elements. However, these are not always feasible or available and investigators will need the guidance, tools, and incentives to contribute to the science in the same way outside of such formal structures.

While the aforementioned tools, processes, and structures will surely address some of the challenges of coordinated HIV IR, the pace of research needs to speed up to meet the ambitious goal to end the HIV epidemic in the United States by the year 2030. As shown in the analysis of data velocity in this issue by Schwartz et al.,32 the standard cycle of 5-year R01s will not be capable of producing IR evidence at the necessary pace. National coordinating efforts should consider focusing on providing an infrastructure to support rapid cycle research and perform cumulative designs, which are a formal method of planning to conduct and then combine distinct implementation studies, potentially funded through different mechanisms and by different research teams, to increase power, achieve representativeness of sites/populations, and obtain sufficient data to draw valid conclusions.33

Along with the expected growth in the emphasis on IR in the field of HIV comes a need to develop the workforce. On the heels of the NIH sunsetting the Training Institute in Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health (TIDIRH), where many HIV investigators received training in IR, an inter-CFAR IS Fellowship for early-stage investigators housed at Johns Hopkins University was launched in 2019 with support from the EHE initiative. Across the first two years of the fellowship, 51 of 108 applicants were admitted to the program. Within one year of Cohort 1 finishing the fellowship, 22 of the 27 fellows (81%) had submitted a HIV IR grant, 13 of which were awarded to 10 different fellows.34. ISCI provided formal training to supplement awardees beginning with a two-day workshop in Chicago in 2019 and followed by webinars and individual consultation sessions in the years since. Preliminary evaluation data about ISCI and hub services suggest they are effective in improving the quality of IR proposed: for every unit increase in engagement in ISCI activities (coaching, webinars, peer groups, etc.), FY19 projects were twice as likely to receive additional NIH funding in FY20 (p=.047).26 Informed by a national advisory panel of HIV service providers and community representatives, ISCI is currently in the process of deploying compendiums of training materials and live workshops on HIV IR designed specifically for HIV service providers and funders so that they can effectively partner with researchers and consume findings from high quality HIV IR.

Finally, as depicted in Figure 2, the findings of synthesized, generalizable knowledge in IR must reach those that are expected to put it into practice. Unlike the typical dissemination target of effective interventions (clinicians and other service deliverers), the audience for IR is clinic managers, program funders, and policy makers who need to learn strategies for implementing effective interventions. Not only does this different target for dissemination require that generated knowledge be readily actionable, the data provided must be meaningful and relevant. This means going beyond effect sizes of the interventions to providing budget impact analyses on the costs to the agency to implement, the resources required, and expected return on investment, to name a few. We as a field need to work with potential implementers to understand the metrics that are meaningful to informing decisions to adopt and sustain implementation of effective HIV interventions,35,36 and we also need to incentivize the collection and reporting of these data in peer-reviewed journals and other non-scientific outlets. Finally, funders of HIV services need to mandate, incentivize, or otherwise ensure that evidence-based implementation strategies are being used to implement effective HIV interventions. More research is needed to inform precisely what these strategies should be.

While significant challenges remain to ensure the best available research is used in the prevention and treatment of HIV, implementation science has produced some noteworthy impacts on health and healthcare in the United States. In HIV, the CDC’s Disseminating Evidence-Based Interventions (DEBI) program has disseminated 29 effective interventions to more than 11,000 agencies, affecting the lives of untold numbers of Americans.37 Kilbourne, Glasgow, & Chambers38 also note the significant impact and expanded reach of IR on patient safety checklists for surgery and other procedures,39 the Diabetes Prevention Program,40 and the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program.41 These exemplars, among a handful of others, clearly chart a path for the NIH’s IR efforts within EHE.

A core tenant of IS is that the context where services are implemented matters, and similarly in striving to advance IS in support of EHE goals, we must acknowledge that there is debate about where and to what extent IS fits in NIH’s portfolio. For example, recently in discussing the country’s mental health crisis, the former director of NIMH, Thomas Insel, stated that good mental health treatments exist, but it is not the job of scientists to provide services.42 He went on to argue that the NIH funding scientists to address implementation problems is like “…asking for French food from an Italian restaurant.” Around the same time, in an interview about his departure as NIH Director, Francis Collins described his chief regret as not investing more in behavioral science to understand COVID vaccine hesitancy.43 In IS parlance, this could be studied and addressed with approaches such as consumer engagement strategies and understanding the characteristics of the vaccine that would render it more acceptable. We agree with Insel it should not be NIH’s role to provide services, but like Collins we agree that more investment by NIH in the science of how to successfully implement effective interventions (like COVID vaccines, HIV interventions, etc.) is the domain of the scientific enterprise that merits NIH support. Otherwise—harkening back to Insel’s analogy—NIH runs the risk of becoming a kitchen that prepares exquisite dishes that are never enjoyed by the public who paid for their preparation. With the knowledge compiled in this supplement, wide-spread IS support, and a myriad of investigators and implementation partners collaborating to better understand what is needed to effectively implement the many evidence-based HIV interventions at our disposal, our ability to reach EHE 2030 goals is greatly strengthened. Underlying all the efforts is a strong and on-going commitment from NIH, CDC, HRSA and other federal agencies to fund and support activities that collectively help produce generalizable knowledge that is crucial to ending the HIV epidemic.

Acknowledgements:

This work was made possible through a supplement grant to the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded center (P30 AI117943). We acknowledge the support of all of the staff of the Implementation Science Coordination Initiatives, the collaboration with all of the implementation research hubs and federal agency staff involved in the EHE initiatives, and for all of the implementation research projects that we had the opportunity to work with.

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA. Feb 7 2019;doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2019. In: HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, 2021. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html Accessed: 3/3/2022

- 3.Mustanski B, Moskowitz DA, Moran KO, Rendina HJ, Newcomb ME, Macapagal K. Factors Associated With HIV Testing in Teenage Men Who Have Sex With Men. Pediatrics. Mar 2020;145(3)doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. Accessed June 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-26-1.pdf

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Infection Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors among Persons Who Inject Drugs—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: Injection Drug Use. HIV Surveillance Special Report. 2020;23(24) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Infection Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors among Men Who Have Sex with Men - National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 23 U.S. Cities, 2017. Updated February 2019. 22. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Infection, Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors Among Heterosexually Active Adults at Increased Risk for HIV Infection–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 23 U.S. Cities, 2019. 2021.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Infection, Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors Among Transgender Women-National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 7 U.S. Cities, 2019-2020. 2021.

- 9.Underhill K, Operario D, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer MR, Mayer KH. Implementation science of pre-exposure prophylaxis: preparing for public use. Review. Current HIV/AIDS reports. Nov 2010;7(4):210–9. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0062-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phanuphak P, Lo YR. Implementing early diagnosis and treatment: programmatic considerations. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. Jan 2015;10(1):69–75. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasgow RE, Eckstein ET, Elzarrad MK. Implementation science perspectives and opportunities for HIV/AIDS research: Integrating science, practice, and policy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Jun 1 2013;63 Suppl 1:S26–31. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker JD, Wei C, Pendse R, Lo Y-R. HIV self-testing among key populations: an implementation science approach to evaluating self-testing. Journal of virus eradication. 2015;1(1):38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JD, Li DH, Hirschhorn LR, et al. Landscape of HIV Implementation Research Funded by the National Institutes of Health: A Mapping Review of Project Abstracts. AIDS Behav. Jun 2020;24(6):1903–1911. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02764-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shangani S, Bhaskar N, Richmond N, Operario D, van den Berg JJ. A systematic review of early adoption of implementation science for HIV prevention or treatment in the United States. AIDS. Feb 2 2021;35(2):177–191. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purcell D, Namkung Lee A, Dempsey A, et al. Fostering program science collaboration in HIV prevention and treatment through enhanced federal collaborations. JAIDS. 2022;In Press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health (R01 Clinical Trial Optional) (US Department of Health and Human Services; ) (2019). Washington D.C. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-19-274.html Accessed 6/10/2021 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, et al. An Overview of Research and Evaluation Designs for Dissemination and Implementation. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2017;38:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell DW, Flores SA, Koenig LJ, Cleveland JC, Mermin J. Enhancing HIV Prevention and Care Through CAPUS and Other Demonstration Projects Aimed at Achieving National HIV/AIDS Strategy Goals, 2010–2018. Public Health Rep. Nov/Dec 2018;133(2_suppl):6S–9S. doi: 10.1177/0033354918800024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg AE, Purcell DW, Gordon CM, et al. NIH Support of Centers for AIDS Research and Department of Health Collaborative Public Health Research: Advancing CDC’s Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. November 1, 2013. 2013;64:S1–S6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a99bc1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg AE, Purcell DW, Gordon CM, Barasky RJ, del Rio C. Addressing the Challenges of the HIV Continuum of Care in High-Prevalence Cities in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. May 1, 2015. 2015;69:S1–S7. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000000569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg AE, Gordon CM, Purcell DW. Promotion of research on the HIV continuum of care in the United States: the CFAR HIV Continuum of Care/ECHPP Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Synd. 2017;74(Suppl 2):S75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. The implementation research logic model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implementation science : IS. 2020 2020;15:84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith JD, Norton W, Battestilli W, et al. Usability and Initial Findings of the Longitudinal Implementation Strategy Tracking System (LISTS) in the IMPACT Consortium. Presented at: 14th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation; 2021; Washington, D.C (virtual) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith JD, Norton W, DiMartino L, et al. A Longitudinal Implementation Strategies Tracking System (LISTS): Development and Initial Acceptability. 2020. Presented at: 13th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation; 2020; Washington, D.C. (virtual) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li DH, Benbow N, Keiser B, et al. Determinants of implementation for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis based on an updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: A systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Synd. 2022;(in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Queiroz AA, Mongrella M, Keiser B, Li DH, Benbow N. Implementing an End to the HIV Epidemic: Profile of NIH-funded Projects Supported by the Implementation Science Coordination Initiative (ISCI). J Acquir Immune Defic Synd. 2022;(In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNulty M, Smith JD, Villamar J, et al. Implementation research methodologies for achieving scientific equity and health equity. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 1):83–92. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelton RC, Adsul P, Oh A, Moise N, Griffith DM. Application of an antiracism lens in the field of implementation science (IS): Recommendations for reframing implementation research with a focus on justice and racial equity. Implementation Research and Practice. 2021;2:26334895211049482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownson RC, Kumanyika SK, Kreuter MW, Haire-Joshu D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implementation science: IS. 2021/03/19 2021;16(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helfrich CD, Hartmann CW, Parikh TJ, Au DH. Promoting health equity through de-implementation research. Ethnicity & Disease. 2019;29(Suppl 1):93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geng EH, Holmes CB, Moshabela M, Sikazwe I, Petersen ML. Personalized public health: an implementation research agenda for the HIV response and beyond. PLoS medicine. 2019;16(12):e1003020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz S, Ortiz JC, Smith JD, et al. Data Velocity in HIV-related Implementation Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022;(In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curran GM, Smith JD, Landsverk J, et al. Design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Research to Practice (3 ed). New York: Oxford University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz SR, Smith J, Hoffmann C, et al. Implementing Implementation Research: Teaching Implementation Research to HIV Researchers. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2021;18(3):186–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bannister J, Hardill I. Knowledge mobilisation and the social sciences: dancing with new partners in an age of austerity. Contempor Soc Sci. 2013;8(3):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vindrola-Padros C, Pape T, Utley M, Fulop NJ. The role of embedded research in quality improvement: a narrative review. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2017;26(1):70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins CB Jr, Sapiano TN. Lessons learned from dissemination of evidence-based interventions for HIV prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):S140–S147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilbourne AM, Glasgow RE, Chambers DA. What can implementation science do for you? key success stories from the field. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birkmeyer JD. Strategies for improving surgical quality—checklists and beyond. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(20):1963–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nhim K, Gruss SM, Porterfield DS, et al. Using a RE-AIM framework to identify promising practices in National Diabetes Prevention Program implementation. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ory MG, Smith ML, Patton K, Lorig K, Zenker W, Whitelaw N. Self-management at the tipping point: reaching 100,000 Americans with evidence-based programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(5):821–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barry E. The ‘Nation’s Psychiatrist’ Takes Stock, With Frustration. New York Times. 2022. Feb 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/22/us/thomas-insel-book.html Accessed 3/3/2022 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiland N, Kolata G. N.I.H.’s Longtime Leader, and Guide in Pandemic, Is Stepping Down. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/05/us/politics/francis-collins-nih.html Accessed: 3/4/2022