Abstract

Objective

Penile neoplasia, usually of squamous histogenesis, is currently classified into human papillomavirus (HPV)-related or -dependent and non-HPV-related or -independent. There are distinct morphological differences among the two groups. New research studies on penile cancer from Northern countries showed that the presence of HPV is correlated with a better prognosis than virus negative people, while studies in Southern countries had not confirmed, perhaps due to differences in staging or treatment.

Methods

We focused on the description of the HPV-related carcinomas of the penis. The approach was to describe common clinical features followed by the pathological features of each entity or subtype stressing the characteristics for differential diagnosis, HPV genotypes, and prognostic features of the invasive carcinomas. Similar structure was followed for penile intraepithelial neoplasia, except for prognosis because of the scant evidence available.

Results

Most of HPV-related lesions can be straightforwardly recognized by routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, but in some cases surrogate p16 immunohistochemical staining or molecular methods such as in situ hybridization or polymerase chain reaction can be utilized. Currently, there are eight tumor invasive variants associated with HPV, as follows: basaloid, warty, warty-basaloid, papillary basaloid, clear cell, medullary, lymphoepithelioma-like, and giant condylomas with malignant transformation.

Conclusion

This review presents and describes the heterogeneous clinical, morphological, and genotypic features of the HPV-related subtypes of invasive and non-invasive penile neoplasia.

Keywords: Penile neoplasia, Squamous cell carcinoma, Human papillomavirus, Carcinoma in situ, Penile intraepithelial neoplasia

1. Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the penis is similar to its squamous counterpart arising in other sites, including oral mucosa and vulva. About 60% of all penile tumors are non-papillomatous of the usual or conventional type and are predominantly non-human papillomavirus (HPV)-related. Conversely, SCC variants are predominantly HPV-related. The association of morphology and HPV infection in vulvar and penile cancer was established by the pioneer studies of Park et al. [1,2] and Gregoire et al. [3] in 1991 and 1995, respectively. These authors found a high virus prevalence in carcinomas with basaloid and warty (condylomatous) features. Conversely, HPV was negative or rarely positive in keratinizing SCC variants, such as usual, verrucous, sarcomatoid, and papillary, not otherwise carcinoma. These findings were pivotal for developing the dual pathogenesis hypothesis of HPV-related and non-HPV-related invasive penile carcinoma suggested in a major collaborative international study [4]. Several other studies consistently supported this association. The basaloid cell, present in these neoplasms, was considered the best tissue marker for HPV infection [5,6]. As a result, the 2016 World Health Organization pathological classification of penile carcinomas distinguished penile SCC into HPV-related and non-HPV-related subtypes. The allocation of invasive penile carcinomas in these two groups is not mutually exclusive. Rarely, some usual SCC may be HPV positive, and some bona fide basaloid or warty carcinomas may be HPV negative with available detection techniques [7].

The most frequent HPV-related subtypes are mainly three: basaloid, warty, and warty-basaloid (Fig. 1). Other HPV-related SCC variants were subsequently described. Some of these variants are composed of large, poorly differentiated cells resembling head and neck tumors [8,9]. Seven subtypes of HPV-related penile carcinomas (basaloid, warty, warty-basaloid, papillary basaloid, clear cell, medullary, and lymphoepithelioma-like) and giant condylomas with malignant transformation are currently recognized, each with distinctive clinicopathologic features. These subtypes can be diagnosed with routine staining in most cases. Occasionally, immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be required. p16 is a useful surrogate for HPV detection in penile carcinomas and an easily available immunohistochemical marker [10,11]. Interestingly, we also found some morphological variations in each of these subtypes, which hampered the diagnosis in some cases [12].

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of the most frequent histologic subtypes of penile human papillomavirus-related squamous cell carcinomas. (A) Basaloid carcinoma mainly composed of small, blue cells grouped in solid sheets, or nests with central abrupt keratinization or comedo-like necrosis; (B) Basaloid carcinoma with small, blue cells grouped in solid sheets and trabeculae; (C) Papillary basaloid carcinoma—variant of the basaloid with papillae lined by small, blue cells; (D) Papillary basaloid carcinoma—abrupt keratinization and invasive nests can be seen; (E) Warty carcinoma—papillomatosis and infiltrative nests composed of koilocytes and cells with ample eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm are the hallmark; (F) Warty-basaloid carcinoma—features of warty and basaloid carcinomas are seen in the same specimen.

The purpose of this review was to describe the clinicopathologic and genotypic features of HPV-related carcinomas.

2. HPV-related invasive carcinomas

2.1. Clinical features

Patients with HPV-related carcinomas, especially warty and basaloid carcinomas, are about 10 years younger than those with non-HPV-related neoplasms. There is limited clinical information on patients with rare subtypes. Tumors tend to preferentially affect the glans and extend to the foreskin in about 20% of the cases. The latter can also be a primary site. The shaft is rarely affected. The disease duration can vary from years in giant condyloma and warty carcinoma to a few months in basaloid and medullary carcinoma.

2.2. Pathological features

The macroscopic features are heterogeneous, ranging from large, exophytic papillary lesions to small non-papillomatous tumors. Exophytic tumors include giant condyloma with malignant transformation, warty, warty-basaloid, and papillary-basaloid carcinomas. Ulcerative, non-papillomatous tumors include basaloid, medullary, clear cell, and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. Giant condyloma, with or without malignant transformation, can be macroscopically identical to warty carcinomas.

Microscopic features are variable. Carcinomas are composed of three cell types: small basaloid cells, clear cells or koilocytes, and large anaplastic cells. The latter characteristically shows stromal-associated inflammatory cells.

2.2.1. Basaloid carcinoma

The most frequent HPV-related invasive neoplasm has a variable presentation. Typically, it shows a downward proliferation with deeply invasive nests of small uniform basaloid cells, central abrupt keratinization or necrosis, and a comedocarcinoma-like appearance. Cell palisading is inconspicuous. An artefactual clear space around the nests is characteristic. Other features include a downward growth with large solid sheets of basaloid cells, adenoid or pseudoglandular pattern, spindle cells, and salivary production of gland-type membranous stroma (Fig. 2A–D). Mitoses are frequent. Apoptosis with a starry sky pattern may be present [13,14]. Rarely, sarcomatoid transformation can occur. The differential diagnosis includes the nested variant of usual SCC where cells are usually larger and keratinization is gradual instead of abrupt. Occasionally, basaloid carcinoma is solid and composed of small uniform cells or organoid features simulating neuroendocrine tumors. An adenoid pattern may lead to confusion with urethral glandular lesions; within a typical basaloid carcinoma, well defined non-mucinous pseudoglandular features may occur. Tumors originating in Littre glands are usually mucinous. Another entity in the differential diagnosis is basal cell carcinoma; however, it does not occur on the mucosal surface, as typical of most penile SCCs, but arises from the shaft's skin and shows palisading and myxoid changes. Most basaloid carcinomas, primarily those described in series from developing countries, are high-stage, high-grade, and deeply invasive with frequent inguinal nodal metastasis [14].

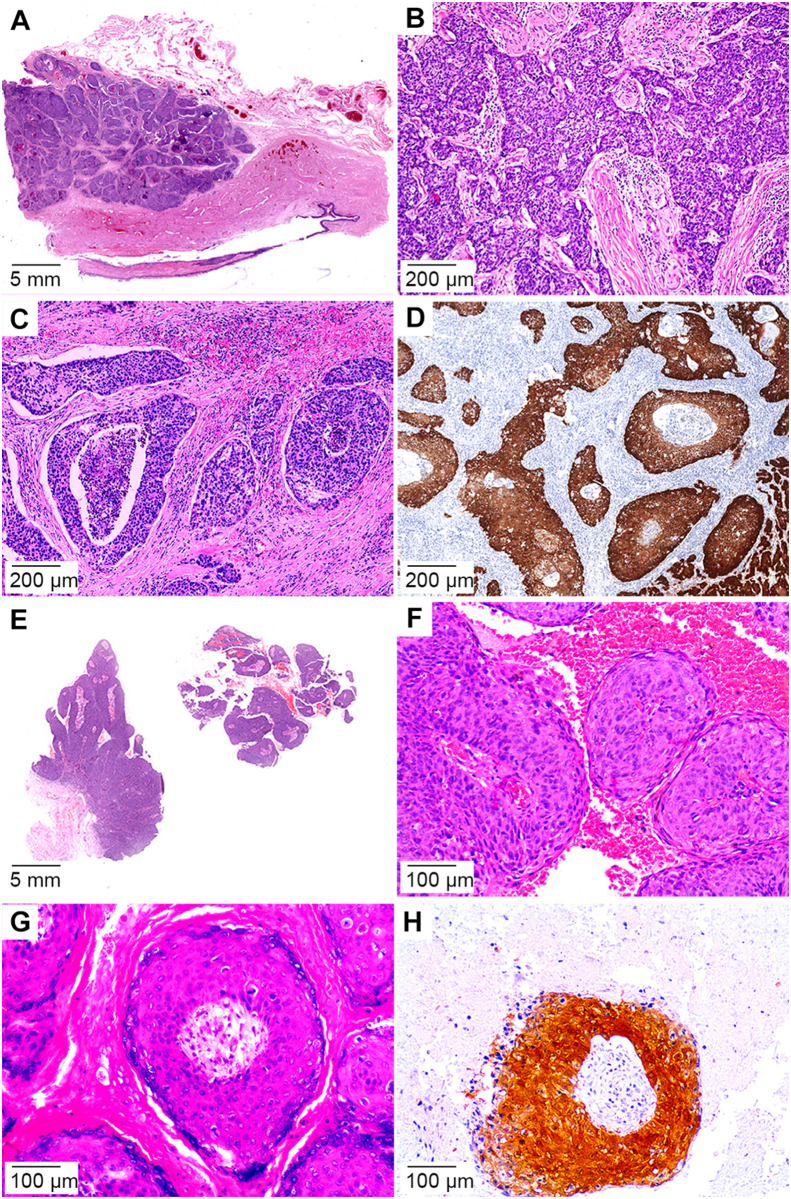

Figure 2.

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and papillary basaloid variant. (A) Basaloid carcinoma seen as deeply invasive sheets, nests of interanastomosing trabeculae; (B) Starry night features seen due to this high-grade tumor; (C) Invasive nest with central comedo-like necrosis and characteristic surrounding clear space artifact; (D) p16 immunostain positive nests; (E) Low power view depicting the characteristic architecture of papillary basaloid carcinoma; (F) Papillae composed by a central fibrovascular core lined by small blue cells; (G) Abrupt keratinization and scant koilocytes; (H) p16 immunostain positive nest.

2.2.2. Papillary-basaloid carcinoma is an unusual, albeit distinctive variant of basaloid carcinoma

Unlike basaloid carcinoma (typically non-exophytic and non-papillomatous), the papillary variant shows papillomatosis with condylomatous papillae depicting a prominent central fibrovascular core. The cellular composition of the papillae (unlike warty carcinomas) is characterized by a non-keratinizing, small cell basaloid pattern. Even so, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and superficial koilocytosis, not characteristic of the basaloid pattern, may be present. These papillary basaloid carcinomas can show nesting or solid invasive patterns indistinguishable from the basaloid carcinoma (Fig. 2E–H). Papillary basaloid carcinoma is the only penile papillomatous tumor mainly or entirely composed of small basaloid cells. It is unlikely to be misdiagnosed as other papillary lesions, such as warty carcinoma, non-HPV-related verrucous, or papillary carcinoma [15].

2.2.3. Warty carcinoma

These exophytic tumors are characterized by papillomatous growth. Condylomatous papillae have a central fibrovascular core. Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and pleomorphic clear cell koilocytosis involving the full epithelial thickness, unlike condylomas, are prominent. The tumor-stroma interface is irregular and jagged, at least focally [16,17] (Fig. 3A–D). A regular, broadly-based tumor front similar to verrucous carcinoma or giant condyloma is a less common presentation. Although warty carcinomas are usually moderately differentiated (Grade 2), occasionally, they may be well-differentiated (Grade 1) and need to be distinguished from papillary carcinoma, a non-HPV-related neoplasm. Differential diagnosis may require HPV detection. Other verruciform tumors in the differential diagnosis are verrucous carcinoma and giant condyloma. Verrucous carcinoma is HPV-negative, which does not show condylomatous papillae, koilocytosis, and consistently has a broad-based tumor front. Giant condyloma with malignant transformation may be difficult to differentiate from warty carcinoma. It is often low-grade with a sharply delineated tumor front, and the malignant changes are typically similar to those of usual SCC. Giant condylomas harbor low-risk HPV while warty carcinomas frequently harbor high-risk HPV.

Figure 3.

Warty and warty-basaloid squamous cell carcinoma human papillomavirus-related subtypes. (A) Papillomatous lesions arising from the foreskin; (B) Papillae seen at low power view; (C) The cells with ample eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm; (D) Atypical koilocytes surrounding a central fibrovascular core or arranged in invasive nests seen at higher power; (E) Warty-basaloid tumor with classic warty features on the surface and invasive basaloid nests in the lower left corner; (F) Both cell types (basaloid and warty) seen in the same sheet or nest; (G) Basaloid cells seen closer to the fibrovascular core and warty cells composing the superficial layers; (H) p16 immunostain of the basaloid component in warty-basaloid squamous cell carcinoma.

2.2.4. Warty-basaloid carcinoma

This biphasic neoplasm is composed of warty and basaloid features (Fig. 3E–H). The typical presentation is exophytic, papillomatous warty carcinoma on the surface and a nested, basaloid carcinoma on deeper areas. Less common is a non-exophytic tumor with a nesting growth pattern, in which the nests are composed of a mixed population of small basal cells in the lower half and clear cells with warty features in the lumen [18]. The proportions of both features are variable. At least 90% of either pattern is required to diagnose a pure subtype.

2.2.5. Clear cell carcinoma

This is a morphologically distinctive high-grade rare neoplasm. It may represent an aggressive non-verruciform variant of warty carcinoma. It grows characteristically in a non-papillomatous and infiltrating downward nesting pattern. The nests are either solid or having central necrosis (comedocarcinoma pattern) and are composed of non-keratinizing large cells with anaplastic nuclei and clear cytoplasm (Fig. 4A–D). A solid growth pattern may also be identified. Clear cell carcinoma is a deeply invasive, high-grade tumor with frequent vascular invasion, and regional and systemic spread. Only two series of penile clear cell carcinoma have been published [19,20]. The differential diagnosis includes the nested variant of usual SCC, warty carcinoma, and basaloid carcinoma. Unlike warty carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma is not papillomatous. The nested comedocarcinoma-like growth pattern is similar to basaloid carcinoma, but the cell composition differs, such as no small basaloid cells. This carcinoma could represent a variant of warty carcinoma.

Figure 4.

Less frequent HPV-related carcinomas histologic types. (A) Clear cell SCC with invasive solid sheets or nests; (B) Clear cell SCC nests composed of cells with ample clear cytoplasm and atypical koilocytes, abrupt keratinization and/or comedo-like necrosis; (C) p16 immunostain positive in the viable clear cells; (D) Chromogenic in situ hybridization for high-risk HPV in clear cell SCC; (E) Medullary carcinoma composed of solid nest of large, poorly differentiated cells and inflammatory cell infiltrate; (F) p16 immunostaining of the tumor cell sheets in medullary SCC; (G) Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma showing an inflammatory background with high grade tumor cells isolated or arranged in syncytial trabeculae; (H) p16 immunostain of squamous cells in the lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. HPV, human papillomavirus; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

2.2.6. Medullary and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma

Rarely, some poorly differentiated carcinomas with scant or no keratinization may acquire solid or syncytial medullary (Fig. 4E and F) or lymphoepithelioma-like (Fig. 4G and H) features. Tumor- or stroma-associated inflammatory cells are prominent and include lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. The differential diagnosis includes a poorly differentiated non-HPV-related usual SCC. HPV detection is helpful for the diagnosis. Literature data regarding the clinical features of these unusual neoplasms are limited. These carcinomas are usually deeply invasive, high-grade tumors, and prone to regional spread [8,9].

2.2.7. Mixed carcinoma

These entities represent up to 20% of penile carcinomas. These are difficult to classify into specific subtypes. A typical example is verrucous hybrid carcinoma, a non-HPV-related mixed carcinoma composed of verrucous carcinoma and usual SCC. Well-defined HPV-related carcinomas may also be mixed with non-HPV-related carcinomas. A typical example of the previous situation is warty carcinoma (HPV positive) mixed with usual SCC (HPV negative) in the same specimen. Rarely, complex verruciform tumors may have a combination of condyloma and warty, verrucous, or papillary carcinoma. HPV-related mixed carcinomas, excluding warty-basaloid carcinomas, may show combinations of two or more patterns such as warty carcinoma-clear cell carcinoma, warty carcinoma-medullary carcinoma, or others.

2.2.8. Giant condyloma

In view of their propensity for malignant transformation, if left untreated, special consideration for inclusion within the malignant tumor category should be given to giant condyloma (also referred as tumor of Buschke-Löwenstein). This is an unusual HPV-related tumor, primarily diagnosed in developing countries, harboring low-risk HPV. It is similar to common condylomas, except for its large size and heterogeneous presentation if left untreated for a long time. A seminal study by Schmauz et al. [21] in Africa described six cases with histological features of large typical condyloma, atypical condylomas, and condylomas with malignant transformation. The foreskin and coronal sulcus are the most frequently involved penile compartments [12]. Macroscopically, it is an exophytic, cauliflower-like tumor, 5 cm–10 cm long. Microscopic features resemble typical condylomas, except in cases with malignant transformation in which usual or sarcomatoid carcinoma can be seen. The distinction from warty carcinoma may be difficult in atypical cases. Immunohistochemistry for p16 is negative [12].

2.3. HPV genotypes in invasive carcinomas

There is a considerable correlation between p16 immunohistochemistry and HPV positivity in tumors with morphology attributable to HPV (84%) [10]. Thus, p16 is a useful and nonexpensive surrogate of molecular techniques, such as PCR or in situ hybridization for viral detection [10]. There are 52 HPV predominantly high-risk genotypes reported associated with penile invasive carcinoma [7]. HPV16 is the most prevalent genotype, especially in basaloid carcinomas, but non-HPV16 genotypes are frequent, especially in warty carcinoma (Table 1).

Table 1.

HPV genotypes according to subtypes of invasive carcinoma.

| Subtype | Number | HPV genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basaloid | 104 | 16, 31, 33, 34, 35, 52, 55, 58, 73, 16+6, 16+33, 16+35, 16+56, 16+53, 16+44+52, 16+44+66, 18+52, 51+58 | -Alemany et al. [7], Fernández-Nestosa et al. [44] |

| Warty | 33 | 6, 16, 33, 45, 52, 74, 35, 16+56, 31+33, 31+58, 59+74 | -Alemany et al. [7], Fernández-Nestosa et al. [44] |

| Warty-basaloid | 26 | 16, 18, 35, 53, 59, 73, 16+70 | -Alemany et al. [7], Fernández-Nestosa et al. [44] |

| Papillary basaloid | 11 | 16, 51, 16+45 | -Alemany et al. [7], Fernández-Nestosa et al. [44] |

| Medullary | 12 | 16, 33, 58, 16+66 | -Cañete-Portillo et al. [8] |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 8 | 16 | -Liegl and Regauer [19], Sanchez et al. [20] |

| Lymphoepithelioma-like | 2 | High-risk HPV | -Mentrikoski et al. [9], |

| Mixed | 33 | 16, 18, 26, 33, 39, 45, 52, 53, 58, 59 | Alemany et al. [7], Fernández-Nestosa et al. [44] |

HPV, human papillomavirus.

2.4. Prognostic features

As in other sites such as head and neck, and vulva [22,23], several studies have shown that patients with HPV-related penile carcinoma have a better prognosis than those with non-HPV-related carcinomas [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]]. However, other studies, including studies from developing countries, did not identify such survival advantage [[30], [31], [32], [33], [34]]. A possible explanation for this difference is the higher stage of tumors and different treatment standards in developing countries. However, different SCC subtypes have prognostic differences among the most common HPV-related carcinomas. Warty carcinomas are rarely associated with regional spread, and have lower mortality [35]. Basaloid carcinomas are associated with a high rate of inguinal metastasis and have higher mortality [14,35]. Warty-basaloid carcinomas have an intermediate rate of regional spread and mortality. The favorable prognosis of warty carcinomas is related to their lower histological grade and superficial invasion (into lamina propria or superficial corpus spongiosum). The adverse outcome in basaloid carcinoma is related to its higher histological grade, frequent lymphovascular invasion, and infiltration into deep corpus spongiosum or corpora cavernosa. There are limited clinical and outcome data on other unusual HPV-related tumors.

3. Precancerous lesions

3.1. General features

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN) is the preferred nomenclature, replacing older terminology such as dysplasia, erythroplasia of Queyrat, and Bowen's disease [12]. Paget's disease, melanoma in situ, or urethral carcinoma in situ is not included in the PeIN definition. Lesions usually originate in the squamous mucosal epithelium covering the glans, coronal sulcus, and inner surface of the foreskin. The skin of the shaft is affected less frequently. There is a variable array of precancerous lesions based on the dual pathogenesis hypothesis of penile cancer. Similar to its invasive counterparts, PeIN is classified into non-HPV- and HPV-related [12]. Differential diagnosis is possible using hematoxylin and eosin routine stain for standard histology evaluation in most cases. In complex cases, p16 can be used as a surrogate of HPV infection. In situ hybridization and PCR are other methods for HPV detection. HPV-related PeIN is more common than differentiated PeIN presenting as an isolated lesion in Northern countries, while studies in Southern countries had not confirmed, perhaps due to differences in staging or treatment [36,37]. Conversely, differentiated PeIN is more common in developing countries [[38], [39], [40]]. Warty and basaloid PeINs, either isolated or associated with invasive cancer, were more frequent in a French series [38]. Differentiated PeIN is prevalent in regions with a high incidence of penile cancer in both clinical presentations [38]. The difference may be due to a genuine higher frequency of HPV-related lesions in Northern countries, a higher frequency of HIV infection resulting in more HPV-related PeIN, or the practice of circumcision.

3.2. Clinical features

HPV-related PeIN occurs in patients in their 40s–60s, about 10 years younger than those with invasive tumors and non-HPV-related invasive carcinomas. Most lesions are isolated, but multicentric lesions are not uncommon and occur in about a third of cases. A clinicopathologic syndrome of multicentric PeIN involving glans, foreskin, or the shaft diagnosed in young patients is called bowenoid papulosis [41]. PeIN may affect any mucosal compartment and the shaft's skin, but HPV-positive lesions are more common on the glans. Glans and perimeatal urethral epithelium may be simultaneously involved. PeIN can grow along the urethral length and reach surgical resection margins [42,43].

3.3. Pathologic features

Macroscopically, HPV-related PeIN has a heterogeneous appearance, ranging from flat plaques to slightly elevated, villous micropapillary, or nodular lesions. Color varies from white, reddish to dark pigmented. The boundaries may be sharply demarcated, geographic, or poorly delineated. Microscopically, the features of warty and basaloid may be pure or mixed. At least 90% of either warty or basaloid PeIN is required for a pure lesion. Contiguous but different HPV-related lesions (called hybrid PeIN) or non-HPV-related differentiated PeIN with either warty or basaloid PeIN (called mixed PeIN) may be found in the same specimen. There are three distinctive HPV-related PeIN subtype morphologies.

3.3.1. Basaloid PeIN

As the invasive basaloid counterpart, this is the most common subtype of HPV-related PeIN. It is frequently associated with invasive basaloid carcinoma, less frequently with invasive warty carcinoma, and rarely with non-HPV-related invasive carcinomas. The whole layer of squamous epithelium is replaced by small-to-intermediate-sized immature or undifferentiated basaloid cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 5A and B). Hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with isolated clear koilocytes are typical. Mitoses and apoptotic or necrotic individual cells may be numerous giving a starry sky appearance. Most lesions are flat with an undulating, broad tumor base. Some cases are characterized by slender or pleomorphic and giant cell. The differential diagnosis in these cases is related to the pleomorphic variant of differentiated PeIN. Immunohistochemistry for p16 is usually positive in basaloid PeIN and negative in the pleomorphic variant of differentiated PeIN. Occasionally, there is a papillary configuration with condylomatous papillae containing a central fibrovascular core and a lining epithelium composed of small basaloid cells. These lesions may be mistakenly interpreted as urothelial carcinomas.

Figure 5.

Human papillomavirus-related subtypes of PeIN. (A) Basaloid PeIN. The same cellular features seen in the invasive counterpart were visible in hematoxylin and eosin stains; (B) p16 immunostain of the whole thickness of the epithelium in basaloid PeIN; (C) Warty-PeIN with papillary features; (D) p16 immunostain of basal cells in warty PeIN; (E) Warty PeIN with a flat surface. Note the clear cells corresponding to koilocytes without basaloid blue cells; (F) p16 immunostaining positive but weak of all cells in warty PeIN; (G) Warty-basaloid PeIN. Note the dual composition of this neoplasia, basaloid cells in the lower to mid part of the lesion and condylomatous cells in the surface; (H) p16 immunostaining strongly positive of the small basaloid cells in warty-basaloid PeIN. PeIN, penile intraepithelial neoplasias.

3.3.2. Warty PeIN

This PeIN subtype is rare as an isolated lesion and is most commonly diagnosed as multicentric PeIN. Warty PeIN is more frequently associated with invasive warty carcinoma, is less frequently found with invasive basaloid carcinomas, and is rarely found with non-HPV-related invasive carcinoma; the epithelial surface is spiky or shows short micropapillae; hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis and pleomorphic koilocytosis are typical (Fig. 5C–F). Unlike basaloid PeIN, cells are large with clear cytoplasm and squamous maturation. The differential diagnosis with flat or micropapillary condylomas, especially atypical condylomas, may be challenging. Any of the following, positivity for p16 or the identification of high-risk HPV, would favor the diagnosis of warty PeIN [44,45].

3.3.3. Warty-basaloid PeIN

This second most common HPV-related PeIN is defined as a lesion with a combination of basaloid and warty features. This is rarely associated with non-HPV-related invasive carcinoma. Microscopic features of both warty and basaloid PeINs must occur in the same lesion, typically a warty pattern in the upper half and a basaloid pattern in the lower half of the epithelium. Two distinctive cell types are typically present, larger keratinized clear and eosinophilic warty cells, and smaller uniform basaloid cells (Fig. 5G and H).

3.4. HPV genotypes in precancerous lesions

As in invasive carcinoma, there is a correlation between p16 positivity and HPV infection in 84% of penile precancerous lesions [44]. We found 48 HPV genotypes in various PeIN subtypes, more frequently high-risk genotypes, and more likely in association with basaloid PeIN. Overall, there were 24 genotypes in various proportions in PeIN types (Table 2). Low-risk genotypes, such as 6, 11, and 44, were infrequent. Usually, one genotype is associated with one lesion, but multiple genotypes are occasionally present, especially in multicentric PeIN [45]. As in invasive carcinomas, most HPV-related PeINs are associated with HPV16, but other genotypes are also present, especially in warty PeIN.

Table 2.

HPV genotypes according to penile intraepithelial neoplasia subtypes.

| Subtype | Number | HPV genotypesa |

|---|---|---|

| Basaloid | 91 | 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 44, 52, 56, 58, 16+54, 16+18+45+53, 16+51, 16+56, 16+53, 6+73, 16+18, 16+31, 16+53+56 |

| Warty-basaloid | 49 | 16, 18, 30, 33, 35, 52, 56, 58, 51+52, 16+18+31, 31+51+53+58+66, 44+51+59 |

| Warty | 29 | 16, 56, 39, 11, 18, 30, 33, 66, 73, 84, 87, 16+52+66, 18+73 |

| Hybrid warty with basaloid | 2 | 16 |

| Mixed | 1 | 16 |

HPV16 is the sole genotype to be found in all PeIN subtypes. In HPV-related PeINs (basaloid, warty, and warty-basaloid PeINs), four common genotypes have been identified (HPV16, HPV56, HPV18, and HPV33). Three genotypes not present in other subtypes of PeIN were found only in warty PeIN (HPV11, HPV84, and HPV87, all low-risk genotypes), and one genotype not present in other subtypes of PeIN was found in basaloid PeIN (HPV61, low-risk genotype) [45].

4. Conclusion

There were eight variants of HPV-related penile neoplasia described in the literature with differences in frequency, clinical presentation, morphology, and patient outcome. Patients with warty carcinoma showed a good prognosis contrary to basaloid and medullary carcinoma, with the worst prognosis. HPV16 is the most common genotype associated with penile invasive carcinomas (more than 60% of the cases), but there are other genotypes present as well. Precancerous lesions, previously described by a diverse and confusing nomenclature, have been unified into PeIN. Like in invasive tumors, there are three main HPV-related morphological variants including basaloid, warty, and warty-basaloid PeINs. In some cases, more than one type can be present in the same specimen, and HPV and non-HPV types may rarely form mixed lesions. Likewise, HPV16 is the most common genotype associated with HPV-related PeIN especially basaloid subtype, but genotypes other than HPV16 may be present as well, especially in warty PeIN which shows a diverse genotypic make-up. There are not enough studies evaluating the natural history or prognosis of patients with PeIN. The knowledge of the variable clinical, morphological, and genotypic characteristics of HPV-related neoplasms is important for the design of therapeutic approaches and vaccination programs.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Antonio L. Cubilla.

Data acquisition: Ingrid M. Rodríguez, Giovanna A. Giannico.

Data analysis: Alcides Chaux, Diego F. Sanchez.

Drafting of manuscript: Antonio L. Cubilla, Alcides Chaux, Diego F. Sanchez, María José Fernández-Nestosa, Sofía Cañete-Portillo.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Antonio L. Cubilla, Alcides Chaux, Diego F. Sanchez, María José Fernández-Nestosa, Sofía Cañete-Portillo, Giovanna A. Giannico.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Tongji University.

References

- 1.Park J.S., Jones R.W., McLean M.R., Currie J.L., Woodruff J.D., Shah K.V., et al. Possible etiologic heterogeneity of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. A correlation of pathologic characteristics with human papillomavirus detection by in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Cancer. 1991;67:1599–1607. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910315)67:6<1599::aid-cncr2820670622>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J.S., Rader J.S., Wu T.C., Laimins L.A., Currie J.L., Kurman R.J., et al. HPV-16 viral transcripts in vulvar neoplasia: preliminary studies. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;42:250–255. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregoire L., Cubilla A.L., Reuter V.E., Haas G.P., Lancaster W.D. Preferential association of human papillomavirus with high-grade histologic variants of penile-invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1705–1709. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.22.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin M.A., Kleter B., Zhou M., Ayala G., Cubilla A.L., Quint W.G.V., et al. Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in penile carcinoma evidence for multiple independent pathways of penile carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubilla A.L., Lloveras B., Alejo M., Clavero O., Chaux A., Kasamatsu E., et al. The basaloid cell is the best tissue marker for human papillomavirus in invasive penile squamous cell carcinoma: a study of 202 cases from Paraguay. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:104–114. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c76a49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olesen T.B., Sand F.L., Rasmussen C.L., Albieri V., Toft B.G., Norrild B., et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus DNA and p16INK4a in penile cancer and penile intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;20:145–158. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30682-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alemany L., Cubilla A., Halec G., Kasamatsu E., Quirós B., Masferrer E., et al. Role of human papillomavirus in penile carcinomas worldwide. Eur Urol. 2016;69:953–961. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cañete-Portillo S., Clavero O., Sanchez D.F., Silvero A., Abed F., Rodriguez I.M., et al. Medullary carcinoma of the penis: a distinctive HPV-related neoplasm: a report of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:535–540. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mentrikoski M.J., Frierson H.F., Stelow E.B., Cathro H.P. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the penis: association with human papilloma virus infection. Histopathology. 2014;64:312–315. doi: 10.1111/his.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cubilla A.L., Lloveras B., Alejo M., Clavero O., Chaux A., Kasamatsu E., et al. Value of p16INK4a in the pathology of invasive penile squamous cell carcinomas: a report of 202 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:253–261. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318203cdba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canete-Portillo S., Velazquez E.F., Kristiansen G., Egevad L., Grignon D., Chaux A., et al. Report from the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consultation conference on molecular pathology of urogenital cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:e80–e86. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cubilla A.L. In: Tumors of the prostate gland, seminal vesicles, penis, and scrotum. 5th ed. Epstein J.I., Magi-Galluzzi C., Zhou M., Cubilla A.L., editors. American Registry of Pathology; Arlington, Virginia: 2020. Tumors of the penis; pp. 405–612. (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP)). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cubilla A.L., Reuter V.E., Gregoire L., Ayala G., Ocampos S., Lancaster W.D., et al. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma: a distinctive human papilloma virus-related penile neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:755–761. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarado-Cabrero I., Sanchez D.F., Piedras D., Rodriguez-Gómez A., Rodriguez I.M., Fernandez-Nestosa M.J., et al. The variable morphological spectrum of penile basaloid carcinomas: differential diagnosis, prognostic factors and outcome report in 27 cases classified as classic and mixed variants. Appl Cancer Res. 2017;37:3. doi: 10.1186/s41241-017-0010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cubilla A.L., Lloveras B., Alemany L., Alejo M., Vidal A., Kasamatsu E., et al. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the penis with papillary features: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:869–875. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318249c6f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cubilla A.L., Velazques E.F., Reuter V.E., Oliva E., Mihm M.C., Young R.H. Warty (condylomatous) squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: a report of 11 cases and proposed classification of “verruciform” penile tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:505–512. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manipadam M.T., Bhagat S.K., Gopalakrishnan G., Kekre N.S., Chacko N.K., Prasanna S. Warty carcinoma of the penis: a clinicopathological study from South India. Indian J Urol. 2013;29:282–287. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.120106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaux A., Tamboli P., Ayala A., Soares F., Rodriguez I., Barreto J., et al. Warty-basaloid carcinoma: clinicopathological features of a distinctive penile neoplasm. Report of 45 cases. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:896–904. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liegl B., Regauer S. Penile clear cell carcinoma: a report of 5 cases of a distinct entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1513–1517. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000141405.64462.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez D.F., Rodriguez I.M., Piris A., Cañete S., Lezcano C., Velazquez E.F., et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the penis: an HPV-related variant of squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:917–922. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmauz R., Findlay M., Lalwak A., Katsumbira N., Buxton E. Variation in the appearance of giant condyloma in an Ugandan series of cases of carcinoma of the penis. Cancer. 1977;40:1686–1696. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4<1686::aid-cncr2820400444>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan S., Baird A.M., O'Regan E., Sheils O. The role of human papilloma virus in dictating outcomes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.677900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julia C.J., Hoang L.N. A review of prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: evidence from the last decade. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2020;38:37–49. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohanty S.K., Mishra S.K., Bhardwaj N., Sardana R., Jaiswal S., Pattnaik N., et al. p53 and p16ink4a as predictive and prognostic biomarkers for Nodal metastasis and survival in a contemporary cohort of penile squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2021;19:510–520. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2021.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eich M.L., Del Carmen Rodriguez Pena M., Schwartz L., Granada C.P., Rais-Bahrami S., Giannico G., et al. Morphology, p16, HPV, and outcomes in squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: a multi-institutional study. Hum Pathol. 2020;96:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zargar-Shoshtari K., Spiess P.E., Berglund A.E., Sharma P., Powsang J.M., Giuliano A., et al. Clinical significance of p53 and p16INK4a status in a contemporary North American penile carcinoma cohort. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2016;14:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J., Zhang H., Xiu Y., Cheng H., Gu M., Song N. Prognostic significance of p16INK4a expression in penile squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/8345893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu C., Chen K., Tan X., Lu J., Yang Y., Zhang Y., et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and implication on survival in Chinese penile cancer. Virchows Arch. 2020;477:667–675. doi: 10.1007/s00428-020-02831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sand F.L., Rasmussen C.L., Frederiksen M.H., Andersen K.K., Kjær S.K. Prognostic significance of HPV and p16 status in men diagnosed with penile cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:1123–1132. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bezerra A.L.R., Lopes A., Santiago G.H., Ribeiro K.C.B., Latorre M.R.D.O., Villa L.L. Human papillomavirus as a prognostic factor in carcinoma of the penis. Cancer. 2001;91:2315–2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bezerra S.M., Chaux A., Ball M.W., Faraj S.F., Munari E., Gonzalez-Roibon N., et al. Human papillomavirus infection and immunohistochemical p16INK4a expression as predictors of outcome in penile squamous cell carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:532–540. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinestel J., Ghazal A.A., Arndt A., Schnoeller T.J., Schrader A.J., Moeller P., et al. The role of histologic subtype, p16INK4a expression, and presence of human papillomavirus DNA in penile squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:220. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1268-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Fonseca A.G., Soares F.A., Burbano R.R., Silvestre R.V., Pinto L.O.A.D. Human papilloma virus: prevalence, distribution and predictive value to lymphatic metastasis in penile carcinoma. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39:542–550. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.04.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheiner M.A., Campos M.M., Ornellas A.A., Chin E.W., Ornellas M.H., Andrada-Serpa M.J. Human papillomavirus and penile cancers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: HPV typing and clinical features. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:467–476. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guimaraes G.C., Cunha I.W., Soares F.A., Lopes A., Torres J., Chaux A., et al. Penile squamous cell carcinoma clinicopathological features, nodal metastasis and outcome in 333 cases. J Urol. 2009;182:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kravvas G., Ge L., Ng J., Shim T.N., Doiron P.R., Watchorn R., et al. The management of penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN): clinical and histological features and treatment of 345 patients and a review of the literature. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1047–1062. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1800574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashley S., Shanks J.H., Oliveira P., Lucky M., Parnham A., Lau M., et al. Human papilloma virus (HPV) status may impact treatment outcomes in patients with precancerous penile lesions (an eUROGEN study) Int J Impot Res. 2021;33:620–626. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soskin A., Vieillefond A., Carlotti A., Plantier F., Chaux A., Ayala G., et al. Warty/basaloid penile intraepithelial neoplasia is more prevalent than differentiated penile intraepithelial neoplasia in nonendemic regions for penile cancer when compared with endemic areas: a comparative study between pathologic series from Paris and Paraguay. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaux A., Velazquez E.F., Amin A., Soskin A., Pfannl R., Rodriguez I.M., et al. Distribution and characterization of subtypes of penile intraepithelial neoplasia and their association with invasive carcinomas: a pathological study of 139 lesions in 121 patients. Hum Pathol. 2012 1;43:1020–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oertell J., Caballero C., Iglesias M., Chaux A., Amat L., Ayala E., et al. Differentiated precursor lesions and low-grade variants of squamous cell carcinomas are frequent findings in foreskins of patients from a region of high penile cancer incidence. Histopathology. 2011;58:925–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singhal R.R., Patel T.M., Pariath K.A., Vora R.V. Premalignant male genital dermatoses. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2019;40:97–104. doi: 10.4103/ijstd.IJSTD_106_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velazquez E.F., Soskin A., Bock A., Codas R., Barreto J.E., Cubilla A.L. Positive resection margins in partial penectomies: sites of involvement and proposal of local routes of spread of penile squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:384–389. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaux A., Reuter V., Lezcano C., Velazquez E.F., Torres J., Cubilla A.L. Comparison of morphologic features and outcome of resected recurrent and nonrecurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: a study of 81 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1299–1306. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a418ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernández-Nestosa M.J., Guimerà N., Sanchez D.F., Cañete-Portillo S., Velazquez E.F., Jenkins D., et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes in condylomas, intraepithelial neoplasia, and invasive carcinoma of the penis using laser capture microdissection (LCM)-PCR: a study of 191 lesions in 43 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:820–832. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernández-Nestosa M.J., Guimerà N., Sanchez D.F., Cañete-Portillo S., Lobatti A., Velazquez E.F., et al. Comparison of human papillomavirus genotypes in penile intraepithelial neoplasia and associated lesions: LCM-PCR study of 87 lesions in 8 patients. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:265–272. doi: 10.1177/1066896919887802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]