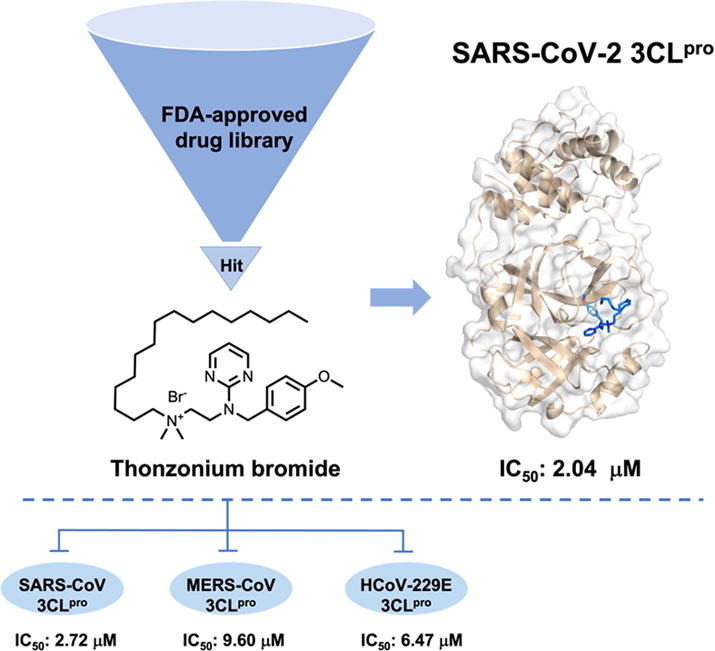

Graphical abstract

Thonzonium bromide was identified as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 2.04 μM from the FDA-approved drug library, which inhibited the activity of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by firmly occupying the catalytic site and inducing conformational change of the protease. In addition, Thonzonium bromide has the broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against 3CLpro of human coronaviruses.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, Thonzonium bromide, Mechanism of action, Broad-spectrum inhibitor

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; 3CLpro, 3C-like protease; nsps, non-structural proteins; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; SAR, structure-activity relationship; CD, circular dichroism; CTRC, human chymotrypsin C; DPP-IV, Dipeptidyl peptidase IV; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PLpro, papain-like protease; VOC, variants of concern

Abstract

Although the effective drugs or vaccines have been developed to prevent the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), their efficacy may be limited for the viral evolution and immune escape. Thus, it is urgently needed to develop the novel broad-spectrum antiviral agents to control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic. The 3C-like protease (3CLpro) is a highly conserved cysteine proteinase that plays a pivotal role in processing the viral polyprotein to create non-structural proteins (nsps) for replication and transcription of SARS-CoV-2, making it an attractive antiviral target for developing broad-spectrum antiviral agents against SARS-CoV-2. In this study, we identified Thonzonium bromide as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 2.04 ± 0.25 μM by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based enzymatic inhibition assay from the FDA-approved drug library. Next, we determined the inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide analogues against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and analyzed their structure–activity relationship (SAR). Interestingly, Thonzonium bromide showed better inhibitory activity than other analogues. Further fluorescence quenching assay, enzyme kinetics analysis, circular dichroism (CD) analysis and molecular docking studies showed that Thonzonium bromide inhibited SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro activity by firmly occupying the catalytic site and inducing conformational changes of the protease. In addition, Thonzonium bromide didn’t exhibit inhibitory activity on human chymotrypsin C (CTRC) and Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), indicating that it had a certain selectivity. Finally, we measured the inhibitory activities of Thonzonium bromide against 3CLpro of SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV-229E and found that it had the broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against the proteases of human coronaviruses. These results provide the possible mechanism of action of Thonzonium bromide, highlighting its potential efficacy against multiple human coronaviruses.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the aetiological agent responsible for the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which caused a global pandemic [1], [2], [3]. Till now, there are three highly pathogenic coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), posing tremendous threats to public health and economic development [4]. In addition, common human coronaviruses, including 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, usually cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold [5]. Currently, vaccines based on the initial SARS-CoV-2 have been widely used to curtail the spread of the disease, however, rapidly spreading SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United Kingdom (B.1.1.7), South Africa (B.1.351), Brazil (B.1.1.248), India (B.1.617), South Africa (B.1.1.529), and elsewhere with multiple mutations in the spike protein may jeopardize newly introduced antibody and vaccine countermeasures [6]. Therefore, it is necessary to update the mAb (monoclonal antibody) cocktails targeting highly conserved regions to enhance the effectiveness of the mAb or adjust the spike sequences of the vaccine to prevent loss of protection in vivo [7], and also raises the unmet urgent need of effective small molecules. Strikingly, first oral antiviral drug Lagevrio (molnupiravir) [8], [9] and later PAXLOVID™ (PF-07321332; ritonavir) showed good therapeutic effects on mild to moderate COVID-19 patients in adults and children with age or weight requirements, and who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19 [10]. Although the vaccines or drugs have been developed to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the viral evolution and immune escape rendering them ineffective remains a possibility [11].

SARS-CoV-2 is one of positive strand, enveloped RNA viruses, which shares 79.6% and about 50% genome sequence identity with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively [12], [13]. The replicase gene of SARS-CoV-2 encodes two polyproteins (pp1a and pp1ab) and four structural proteins [12]. The polyproteins are cleaved by two cysteine proteases, a 3C-like protease (3CLpro) and a papain-like protease (PLpro) at different sites to yield non-structural proteins (nsps) which are essential to viral replication and transcription [14], [15], [16]. Due to its pivotal role in virus replication and transcription, together with the absence of a homologous human protease and variant resistance challenges like spike protein, SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro has become an attractive drug target for the design and development of broad-spectrum antivirals against COVID-19 [17]. To date, potential SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitors with diverse chemical structures have been reported, such as N3 [15], 11b [18], 13b [19], baicalin and baicalein [20], GC-14 [21], etc. In addition, the oral SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitor PF-07321332 demonstrated potent inhibitory activities against 3CLpro from all coronavirus types and was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy adult participants [22]. However, PF-07321332 must be used in combination with ritonavir due to its metabolic instability [23]. More importantly, ritonavir has strong side effects and sometimes fatal drug interactions for the combination therapy with other drugs [24], [25]. Therefore, given the urgency of the COVID-19 global pandemic, there is an enormous unmet need for the development of the novel broad antiviral agents or daily cleaning products to prevent the COVID-19 global pandemic. Repurposed drugs have been considered as a quicker way to identify the new pharmacological role of existing approved drugs to treat the patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [26], [27], [28], [29]. Our previous studies have demonstrated that Vitamin K3 from the FDA-approved drug library is a covalent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro [30].

In the present study, we screened the inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based enzymatic assay and identified another four novel compounds from the FDA-approved drug library. Among of them, Thonzonium bromide showed better inhibitory activity with IC50 of 2.04 μM against the protease. Thonzonium bromide, a cationic surfactant for the treatment of ear infection approved by the FDA, has been proven to have good antibacterial activity in multidrug-resistant filamentous fungi [31]. Moreover, Thonzonium bromide has potential or topical oral treatment, showing anti-caries properties without cytotoxic effect, and having no harmful effects on oral and intestinal tissues in the rodent caries model [32]. Recent studies showed that Thonzonium bromide was identified as a possible active molecule against SARS-CoV-2 main proteinase in silico drug repurposing research [33]. In addition, Thonzonium bromide was effective against SARS-CoV-2 in Huh7-ACE2, HeLa-ACE2 and A549-ACE2 cells in the micromolar range, similar to Remdesivir [34]. However, the specific mechanism of action of Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 has not yet been verified.

Next, we determined the inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide analogues against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and analyzed their structure–activity relationship (SAR). We found that their inhibitory activities were related to the cLogP value, carbon chain length and aryl position by SAR analysis. Among these compounds, Thonzonium bromide exhibited better inhibitory activity than other analogues. The mechanism of the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide was analyzed by fluorescence quenching, enzyme kinetics analysis, circular dichrometry (CD) and molecular docking. The results demonstrated that the inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide may be attributed to firmly occupying the catalytic site and inducing conformational changes of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Interestingly, we found that Thonzonium bromide had no effect on the activities of human chymotrypsin C (CTRC) and Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), suggesting that it specifically inhibited SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Finally, we evaluated the inhibitory effects of Thonzonium bromide on SARS-CoV 3CLpro, MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro, and found that it is a broad-spectrum 3CLpro inhibitor with IC50 values ranging 2.04 to 9.60 μM. Thus, our results revealed the mechanism of action of Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and may have the potential for treating multiple coronavirus diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Expression and purification of 3CL proteases

To express SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, the recombinant expression plasmid pET-29a (+) was constructed according to previously reported procedures [30]. The cells were resuspended and lysed by sonication in the buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mg/mL lysozyme, 25 U/mL Super Nuclease), and then centrifuged at 18000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was purified by affinity chromatography using the Ni-NTA agarose (GE Healthcare) and eluted with 300 mM imidazole. The resulting protein was further passed through Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) and stored in a solution (HEPES 25 mM, pH 7.4, NaCl 150 mM, DTT 1 mM).

The expression and purification of the MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro were performed using methods described previously [35], [36]. The DNA fragment coding for MERS-CoV 3CLpro was cloned into pET-28a(+) through NdeI and XhoI restriction sites, while the gene encoding HCoV-229E 3CLpro was cloned into glutathione S-transferase expression vector pGEX 4T-1 via BamHI and SalI restriction sites. The correct constructs were transformed into competent E.coli BL21 (DE3) cells for protein expression. MERS-CoV 3CLpro was purified using Ni-NTA agarose and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP and 200 mM imidazole. The resulting protein solution was dialyzed with buffer (containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol). The HCoV-229E 3CLpro was purified using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (Smart-Lifescience, changzhou, China) and then treated with 50 U thrombin for 16 h to remove the fusion tag. All processes are performed at 4 °C to prevent protein degradation.

2.2. Enzymatic inhibition assay of 3CL proteases

The FRET-based enzymatic inhibition assay was utilized to measure the inhibitory activities of compounds against 3CL proteases. Primary screening was carried out to identify the inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro using an FDA-approved drug library containing an array of 1,018 compounds obtained from Selleck Chemicals (#L1300) [30]. The fluorogenic substrate Dabcyl-KNSTLQSGLRKE-Edans (GenScript, Shanghai, China) was synthesized to measure the protease activity of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro or SARS-CoV 3CLpro according to our previous method [30], [37]. Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans (GenScript, Shanghai, China) was used for enzymatic inhibition assay of MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro as described previously [38], [39]. The enzymatic inhibition assays of different proteases were performed as follows. 120 nM of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro in the reaction buffer (0.1 M PBS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) incubated with varying concentrations of tested compounds for 1 h at 37 °C and then the substrate (final concentration 20 μM) was added to start the reaction. Fluorescence intensity was monitored continuously every 2 min for up to 20 min with an excitation wavelength of 340 nm and emission wavelength of 490 nm by using Spectramax® ID3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, California, USA). For the SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition assay, 860 nM protease was mixed with 40 μM substrate in assay buffer.

To determine the effect of DTT or GSH on the enzymatic inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide, we performed the enzymatic inhibition assay according to the literature [40]. SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was preincubated in reaction buffer with Thonzonium bromide in the presence of 4 mM DTT or 1 mM GSH compared with in the absence of DTT or GSH buffer.

In the MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro enzymatic inhibition assay, the concentration of the proteases was 2 and 1 μM, corresponding to the final substrate concentration of 40 and 20 μM, respectively. The IC50 values were calculated by fitting the curve of normalized inhibition ratio with the different concentration of test compounds.

2.3. Fluorescence quenching assay

The interaction of Thonzonium bromide with SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was verified using fluorescence quenching according to the method previously described [41]. In brief, different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide were titrated into a cuvette containing a final concentration of 3 μM 3CLpro in 0.1 M PBS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. Then, the spectra of the fluorescence emission were obtained by scanning in the range of 300 to 360 nm using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-4500) with a slit width of 5 nm and excited by a wavelength of 280 nm. The fluorescence quenching data were fitted to the Stern-Volmer equation and the static quenching equation by using GraphPad Prism 8. The Stern-Volmer equation is

| (1) |

The static quenching equation is

| (2) |

F0 and F stand for the fluorescence intensity before and after the addition of Thonzonium bromide, respectively; [Q] means the concentration of Thonzonium bromide; τ 0 is of the fluorophore lifetime, which is about 10-8 s for biological macromolecules [42]; Kq and KSV stand for the bimolecular quenching rate constant and the Stern-Volmer quenching constant, KA is the formation constant; and KD is the dissociation constant, respectively.

2.4. Determination of the inhibition constant Ki of Thonzonium bromide for SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro

The fluorogenic peptide substrate was initially prepared as a 10 mM stock solution in 100% DMSO and diluted to a final concentration (5–80 µM) in the reaction buffer (0.1 M PBS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (final concentration 120 nM) was incubated with different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide (0, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C. The enzyme reaction was initiated and continuously monitored for 20 min after adding the fluorogenic substrate. Curves were fitted to the following equations by using GraphPad Prism 8 enzyme kinetics-inhibition module to determine the best-fit inhibition mechanism and kinetic parameters for Thonzonium bromide.

| (3) |

Where v is the reaction rate, Vmax is the maximum rate of the reaction, Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant for the enzyme-substrate interaction, [S] is the concentration of substrate, [I] is the concentration of inhibitor, Ki is the dissociation constant of the inhibitor to the enzyme.

2.5. CD spectroscopy

The influence of Thonzonium bromide on the structural properties of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was determined according to the previously published method [43]. CD spectra of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and Thonzonium bromide in sodium phosphate (50 mM) buffer were recorded on Brighttime Chirascan (Applied Photophysics ltd, UK) at 25 °C under constant flow rate of nitrogen gas. The spectrum was recorded at wavelengths between 200 and 260 nm with sampling points every 0.5 nm in a 0.1 cm path-length cuvette. The concentration of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was 20 μM in all cases with different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide. The spectra represent an average of three corrected scans. The analysis of secondary structure content was performed using CDNN software (version 2.1) [44], which is a tool used to assess the data to determine helix, antiparallel, parallel, beta-turn, and remainder [45].

2.6. In vitro assessment of human protease selectivity by Thonzonium bromide

The inhibition of CTRC by Thonzonium bromide was performed according to our previously described method [30]. The inhibitory effect of Thonzonium bromide on DPP-IV was determined according to the previous method [46]. Briefly, a highly specific fluorescent probe GP-BAN was synthesized to monitor the real activity of DPP-IV and detect the inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide by using human plasma. 2 μL plasma was incubated with the indicated concentrations (0, 1, 10, 100 μM) of Thonzonium bromide in the assay buffer (0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA) for 1 h. Then the reaction was started by adding 100 µM GP-BNA. After that, the fluorescence signal at 430 nm (excitation)/535 nm (emission) was measured immediately using Spectramax® ID3 plate reader for 20 min.

2.7. Multiple-Sequence alignment and homology modeling

The protein sequences of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and HCoV-229E 3CLpro were retrieved as FASTA format from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The multiple sequence alignment was performed using BLASTp tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins) and presented by ESpript v3.0 (https://espript.ibcp.fr) web server.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibitor screening against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro

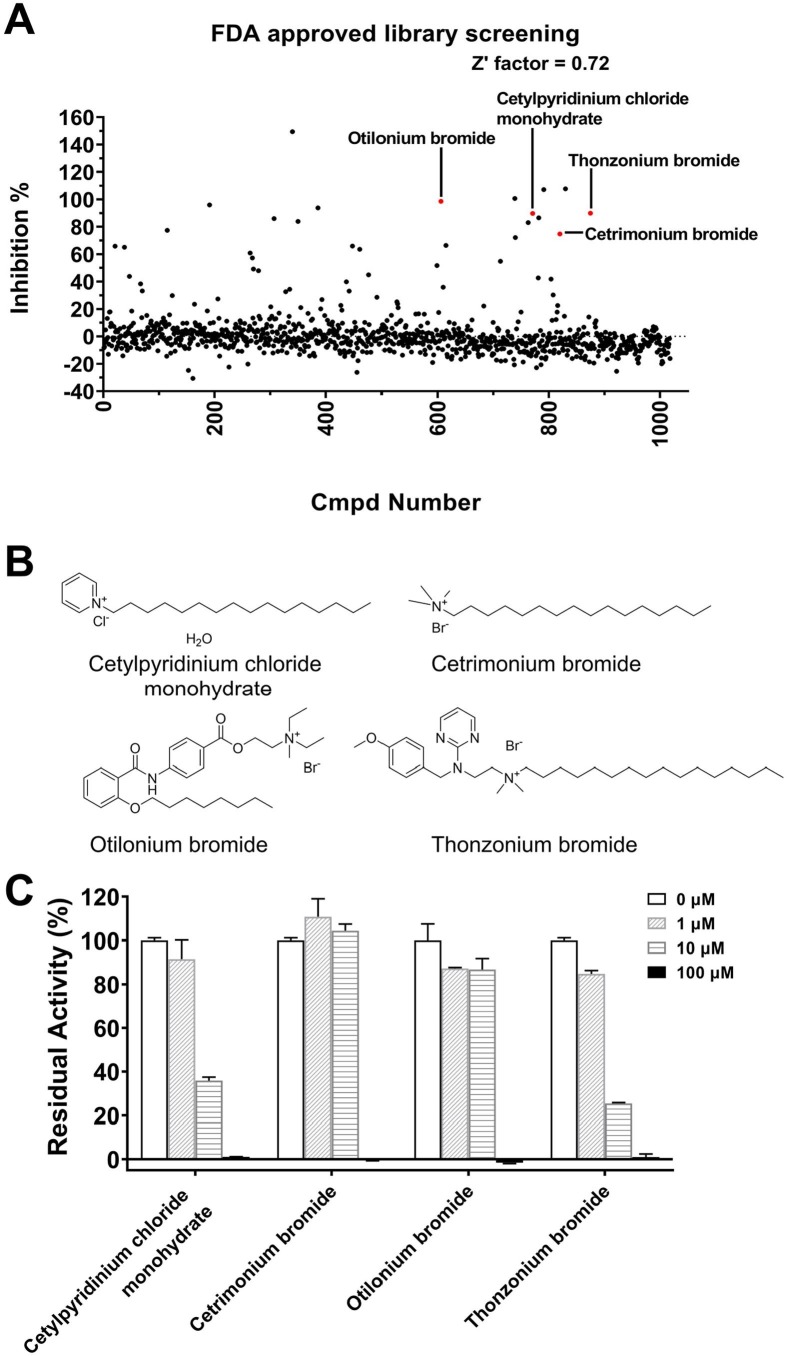

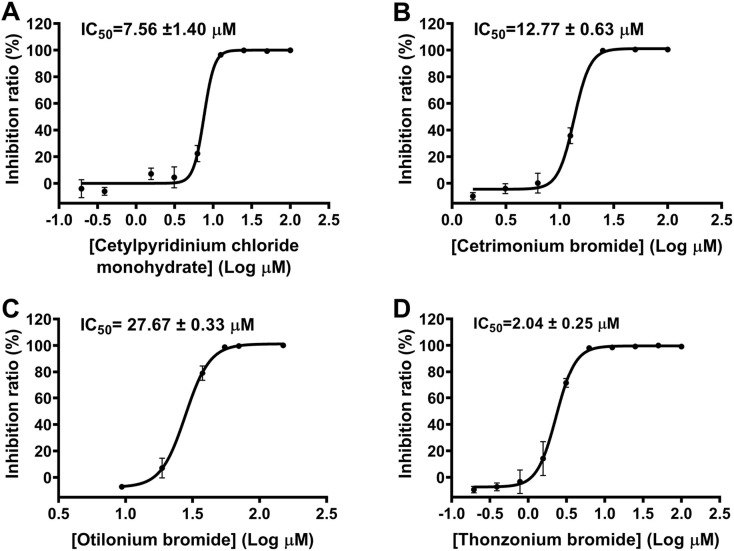

Repurposed drugs with existing clinical data on the effective dose, treatment duration, side effects, and toxicity could be rapidly translated into clinical use for the treatment of COVID-19 patients [47]. We screened the library of FDA-approved drugs for their inhibitory activities against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. It was found that four compounds (Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate, Cetrimonium bromide, Otilonium bromide and Thonzonium bromide, Fig. 1 A-B) with similar long chain structure could significantly inhibit the protease activity at the concentration of 20 μM. For further validation, we examined their inhibitory effects on the protease at four different concentrations (0, 1, 10, 100 μM). These compounds exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (Fig. 1C). We next determined the IC50 values for these compounds against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. The result showed that Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate, Cetrimonium bromide and Thonzonium bromide inhibited the protease activity in a dose-dependent manner with IC50 values of 7.56, 12.77 and 2.04 μM, respectively, while Otilonium bromide exhibited less inhibition with IC50 values of 27.67 μM (Fig. 2 ). Therefore, Thonzonium bromide was the most potent inhibitor in our studies and was selected for further research.

Fig. 1.

Screening of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitors. (A) The chemical structures of Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate, Cetrimonium bromide, Otilonium bromide and Thonzonium bromide. (B) The inhibitory effects of four compounds on SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro at four different concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by four compounds. (A) Representative inhibition curves for Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate, (B) Cetrimonium bromide, (C) Otilonium bromide, and (D) Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

3.2. The inhibitory activities of Thonzonium bromide and its analogues against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro

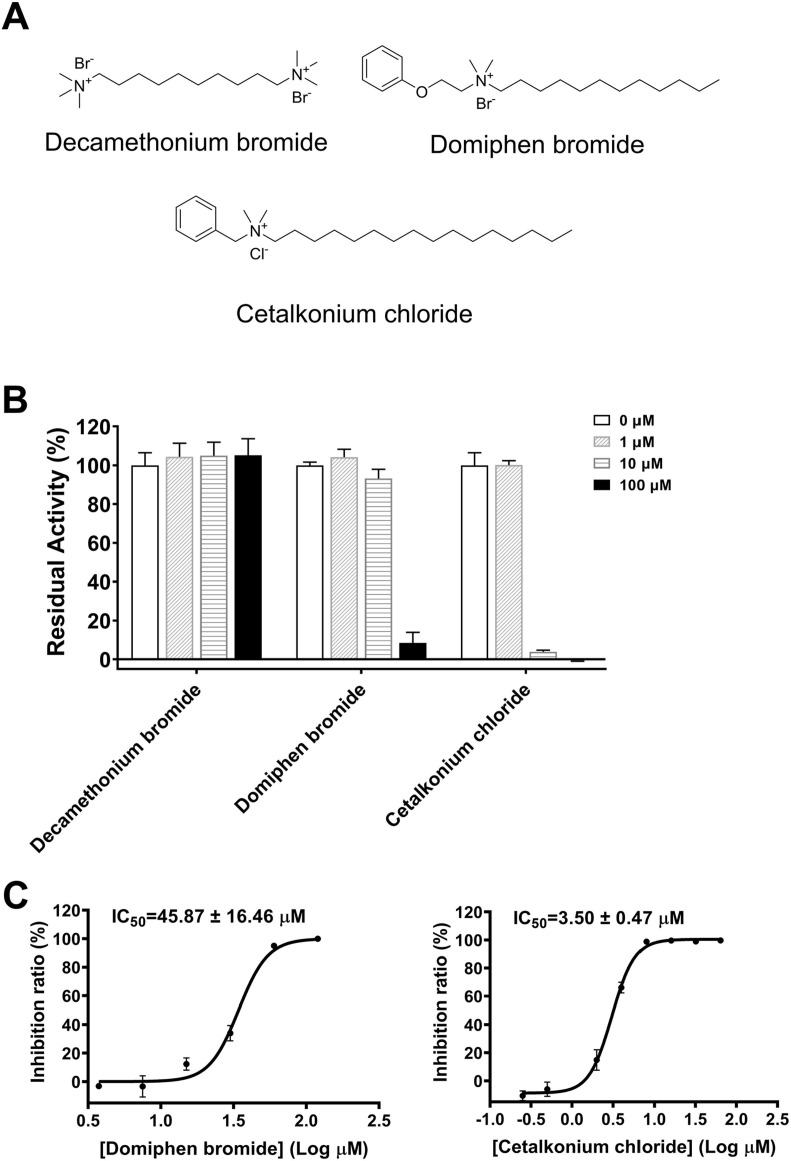

Due to the above four compounds having similar long chain structure and Thonzonium bromide showing the most potent inhibitory activity among them against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, we obtained three Thonzonium bromide analogues from (J&K Scientific and TCI) and determined their inhibitory effects on SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. The preliminary enzymatic inhibition result showed that Domiphen bromide and Cetalkonium chloride displayed > 90% inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro at the concentration of 100 μM (Fig. 3A-B), while no inhibitory activity was observed for Decamethonium bromide. We next measured the IC50 values of Domiphen bromide and Cetalkonium chloride against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro at different concentrations. As shown in Fig. 3C, the activity of Cetalkonium chloride (IC50 = 3.50 ± 0.47 μM) was similar to that of Thonzonium bromide (IC50 = 2.04 ± 0.25 μM), while Domiphen bromide exhibited weaker inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (IC50 = 45.87 ± 16.46 μM). Since Thonzonium bromide and its analogues, as well as the three active compounds in primary screening, are typically surfactants which bear a quaternary ammonium combined with an adjacent long carbon chain, we further compared the correlation of their cLogP and IC50 values. As indicated in Table 1 , cLogP value is correlated with the potency of these compounds, suggesting the compound with the higher cLogP value presenting stronger inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Thonzonium bromide (4) have a cLogP value of 4.92 around the IC50 value of 2 μM. However, clogP is significantly reduced to around 2, it results in 6.26 ∼ 22.49-fold less potent, such as Cetrimonium bromide (12.77 ± 0.63 μM), Otilonium bromide (27.67 ± 0.33 μM) and Domiphen bromide (45.87 ± 16.46 μM). Accordingly, Decamethonium bromide (5) with the cLogP value of −4.87 losses the inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Among the compounds with similar cLogP, carbon chain length of the quaternary ammonium is one of the factors that affects their inhibition potency. Cetrimonium bromide (2) is more potent than Domiphen bromide (6) and Otilonium bromide (3). Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate (1) and Cetalkonium chloride (7) have similar potency to Thonzonium bromide (4) because they have an aryl group adjacent to quaternary ammonium. In conclusion, these results suggest that the inhibitory activities of these compounds against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro are related to the cLogP value, carbon chain length and aryl position. In view of the most potent inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, we chose it for the next mechanism study.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of Decamethonium bromide, Cetalkonium chloride and Domiphen bromide on SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. (A) The chemical structures of Decamethonium bromide, Domiphen bromide and Cetalkonium chloride. (B) The inhibitory effects of three compounds on SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro at four different concentrations. (C) Representative inhibition curves for Domiphen and Cetalkonium chloride bromide against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Table 1.

Structures of seven compounds and their IC50 and clogP values.

| Entry | Compound | Structure | cLogP | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate | 3.47 | 7.56 ± 1.40 | |

| 2 | Cetrimonium bromide | 2.69 | 12.77 ± 0.63 | |

| 3 | Otilonium bromide |  |

2.58 | 27.67 ± 0.33 |

| 4 | Thonzonium bromide | 4.92 | 2.04 ± 0.25 | |

| 5 | Decamethonium bromide | −4.87 | >100 | |

| 6 | Domiphen bromide | 2.55 | 45.87 ± 16.46 | |

| 7 | Cetalkonium chloride | 4.41 | 3.50 ± 0.47 |

3.3. Inhibitory mechanism of Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro

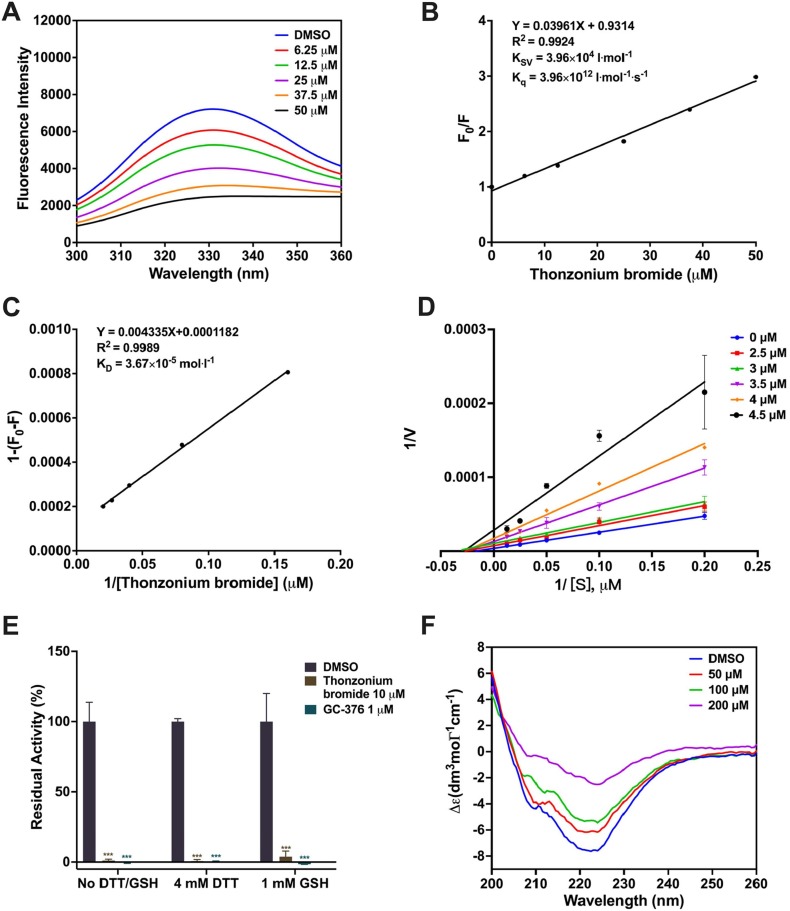

To study the interaction between Thonzonium bromide and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, the fluorescence quenching experiment was carried out. As shown in Fig. 4 A, the fluorescence intensity of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro gradually decreased with an increase of concentration of Thonzonium bromide, demonstrating the interaction between them occurred. Then, the concentration of Thonzonium bromide as the independent variable and F0/F as the dependent variable were fitted to the Stern-Volmer equation. The data showed a good linear relationship (Fig. 4B), and the Ksv value was 3.96 × 104 and Kq value was 3.96 × 1012. For dynamic quenching, the maximum collision quenching constant of various quenchers with biological macromolecules is 2.0 × 1010 lmol-1s−1 [48]. Considering that the rate constant of the quenching procedure of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro initiated by Thonzonium bromide is much greater than 2.0 × 1010 lmol-1s−1 in our experiment, it can be concluded that the quenching is not caused by dynamic quenching, but by the formation of Thonzonium bromide-3CLpro complex. Therefore, the static quenching equation was used to calculate the dissociation constants (KD) derived from the slope of the curve (Fig. 4C), showing the direct binding between Thonzonium bromide and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro.

Fig. 4.

(A) Fluorescence quenching spectrum SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (3 μM) in the presence of different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 37.5, 50 μM). (B) The Stern-Volmer plots for the fluorescence quenching of 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide. (C) The static quenching plots for the fluorescence quenching of 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide. (D) Lineweaver–Burk plots of kinetic data were fitted to obtain the Ki value of 2.62 μM. (E) The inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide in the presence or absence of DTT and GSH. (F) CD spectra of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (20 μM) in the presence of different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide (0, 50, 100, 200 μM).

To determine the inhibitory activity and mechanism of Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, we performed enzyme kinetics analysis. As shown in Fig. 4D, the slopes of the reciprocal Lineweaver-Burk plot elevated with an increase of the concentration of Thonzonium bromide, and the intersection of each trend line on the X-axis indicated that it was a non-competitive inhibitor. The inhibition constant Ki was determined to be 2.62 μM, which is very close to the IC50 value above.

To examine the specific enzymatic inhibition by Thonzonium bromide towards SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, DTT or glutathione (GSH) was added in the enzymatic assay to ensure the enzyme in the active form and prevent nonspecific covalent modification due to thiol reactive compounds [40]. As shown in Fig. 4E, Thonzonium bromide at 10 μM still exhibited potent inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro in the presence of 4 mM DTT or 1 mM GSH, similar to that of a positive control GC-376. Consequently, the inhibition by Thonzonium bromide was not affected by the reducing agent DTT or GSH.

To further explore the inhibitory mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide, CD spectra was measured to detect secondary structure changes of the protease. As shown in Fig. 4F, the CD spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro showed two characteristic negative peaks with a typical spectrum for α-helix proteins at 208 and 222 nm, which is consistent with the far-UV CD result reported previously [43]. The increase in the concentration of Thonzonium bromide results in an increment the Δε values at 208 and 222 nm, indicating the decrease of the α-helical content. To estimate the secondary structure composition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro under different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide, the spectra were analyzed using CDNN software (version 2.1) [44]. As shown in Table 2 , the content of α-helix and antiparallel structure of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro without Thonzonium bromide was 30.80% and 14.50%, respectively. However, the content of α-helix was found to be reduced by 18.5% after Thonzonium bromide at 200 μM was added under the same conditions, demonstrating a more unstable structure. At the same time, the content of antiparallel structure, β-turn and random coil was also increased with the increase in the concentration of Thonzonium bromide in SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Therefore, the result suggested that the secondary structure of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was changed by Thonzonium bromide, which inhibited the activity of the protease.

Table 2.

The fractional content of the secondary structure of the complexes of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro with different concentrations of Thonzonium bromide was calculated by CDNN software.

| Thonzonium bromide concentration (μM) | α-helix (%) | Antiparallel (%) | Parallel (%) | β-turn (%) | Random coil (%) | Total sum (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30.80 | 14.50 | 6.20 | 14.20 | 29.70 | 95.30 |

| 50 | 25.50 | 18.60 | 6.30 | 14.20 | 30.70 | 95.40 |

| 100 | 20.20 | 22.00 | 6.20 | 15.50 | 32.20 | 96.10 |

| 200 | 12.30 | 33.60 | 6.30 | 15.90 | 34.00 | 102.10 |

In order to predict the binding mode of Thonzonium bromide with SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, molecular docking was performed. The result showed that Thonzonium bromide formed hydrogen bonds with the oxyanion hole (residues 143–145) of the catalytic site to prevent efficient cleavage of the substrate by SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Thonzonium bromide formed electrostatic interactions with both Cys145 and His41 via Pi-sulfur and Pi-cation (Fig. S1A-C). What’s more, the pyrimidine and benzene ring of Thonzonium bromide nipped Cys145 from two opposite sides, which might totally inactivate SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (Fig. S1B). The molecular docking result suggested that Thonzonium bromide could firmly occupy the catalytic site and bound with Cys145 in the destructive way. Interestingly, the previous in silico study for drug repurposing also confirmed that Thonzonium Bromide was a potential inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro [33], but the authors did not carry out further experiments.

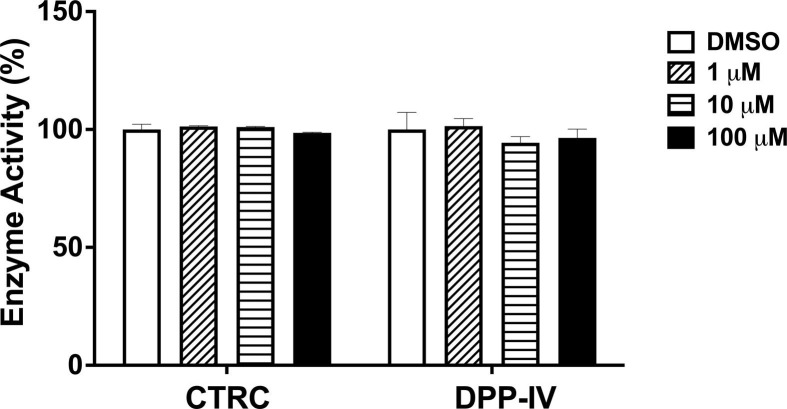

3.4. Selectivity evaluation of human proteases by Thonzonium bromide

To further study the target selectivity over human host proteases, the inhibitory effect of Thonzonium bromide on CTRC or DPP-IV was measured. Encouragingly, Thonzonium bromide did not show measurable activity towards CTRC and DPP-IV (Fig. 5 ). The preliminary studies make Thonzonium bromide an attractive compound, which selectively inhibits SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro.

Fig. 5.

Enzymatic activity of Thonzonium bromide at a concentration of 0, 1, 10, 100 μM towards CTRC or DPP-IV.

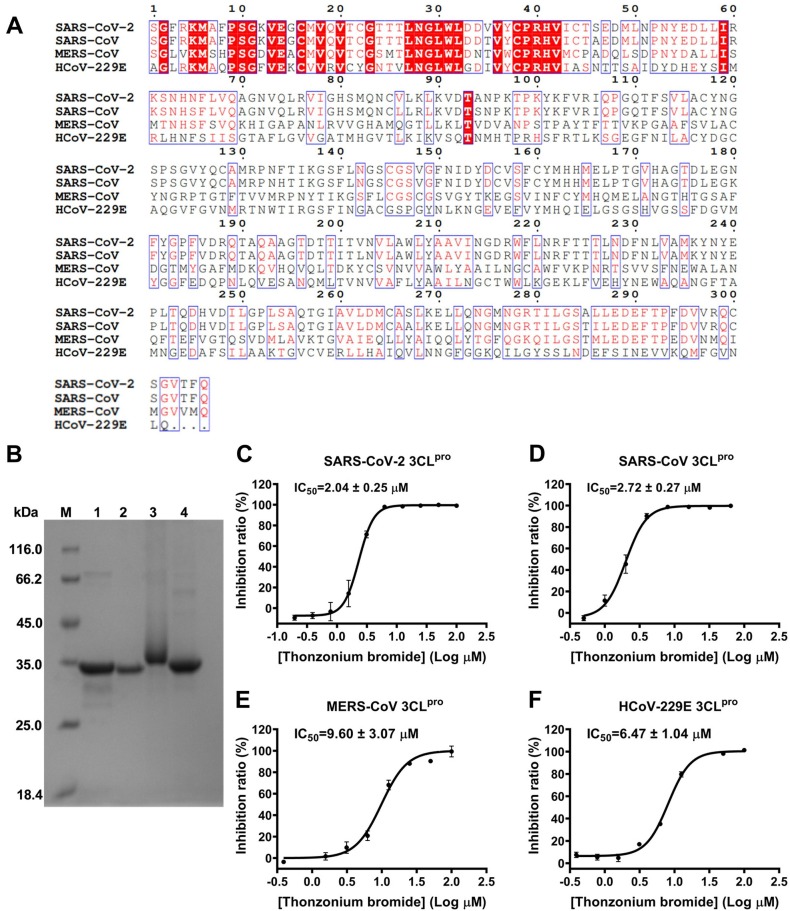

3.5. Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro, MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide

Based on the above results, we speculated that Thonzonium bromide may have inhibitory effect on proteases with similar structures. The multiple-sequence alignment for 3CLpro sequences of clinically relevant coronavirus strains (SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV-229E) is portrayed in Fig. 6 A. The result reveals that SARS-CoV 3CLpro shares 96% amino acid sequence identity as the closest strain to SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, while 3CLpro of MERS-CoV and HCoV-229E shares 51% and 41% sequence identity, respectively. Due to the similarity of protein sequences of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and SARS-CoV 3CLpro, MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro, we expressed and purified these four proteases (Fig. 6B). The enzyme inhibition assay was used to determine the inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide. As shown in Fig. 6C-F, Thonzonium bromide dose-dependently inhibited the activities of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, SARS-CoV 3CLpro, MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro, with IC50 values of 2.04, 2.72, 9.60, and 6.47 μM, respectively. Taken together, our results show that Thonzonium bromide has the broad-spectrum inhibitory activities against the proteases of human coronaviruses.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro, MERS-CoV 3CLpro and HCoV-229E 3CLpro by Thonzonium bromide. (A) Multiple-sequence alignment results of 3CLpro sequences of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV-229E. (B) Purification of four proteases analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Lane M: protein ladder; lane 1: SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro; lane 2: SARS-CoV 3CLpro; lane 3: MERS-CoV 3CLpro; lane 4: HCoV-229E 3CLpro. Representative inhibition curves for Thonzonium bromide against (C) SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, (D) SARS-CoV 3CLpro, (E) MERS-CoV 3CLpro, and (F) HCoV-229E 3CLpro. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

4. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 continues to ravage the world and has impacted the quality of life and caused hundreds of millions of infections and millions of deaths worldwide [49]. While some treatments for COVID-19 have been approved, they exhibited insufficient clinical efficacy or required delivery within a narrow therapeutic window [50], [51], [52]. Recent genetic epidemiological surveillance has identified that SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOC) are circulating globally, especially, omicron (B.1.1.529) with high transmission, showing the ability to break through natural and vaccine-induced immunity; although early reports suggest that it is less severe [53]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel treatments to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants. To date, SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro is considered one of the most important pharmacological targets and the FDA has authorized the emergency use of PAXLOVID (PF-07321332 + ritonavir) for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults and children on December 22, 2021 because of 89% effectiveness in patients at risk of serious illness [10]. PF-07321332 as the first oral SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitor was successfully launched, suggesting that the protease is the effective antiviral drug target.

In this study, we have identified Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate, Cetrimonium bromide, Otilonium bromide and Thonzonium bromide from the library of FDA-approved drugs as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro with IC50 values of 2.04 to 27.67 μM by FRET-based enzymatic inhibition assay (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). There are three approved antiseptics: Cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate, Cetrimonium bromide and Thonzonium bromide [54], [55]. The four compounds are structurally related, as each consisting of a quaternary amine bound to two methyl groups and a long alkyl chain [56]. Thonzonium bromide was approved by the FDA in 1962 and used as an additive in ear and nasal drops due to its surfactant and detergent property [57], [58]. Recent research has reported that Thonzonium bromide exhibited the antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in three cell lines [34]. However, the specific mechanism of action of Thonzonium bromide against SARS-CoV-2 has not yet been verified. Interestingly, we found that Thonzonium bromide displayed stronger inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro than other compounds with IC50 of 2.04 ± 0.25 μM (Fig. 2). To analyze SAR of Thonzonium bromide as well as its similar compounds with aliphatic long-chain, the inhibitory activities of Decamethonium bromide, Cetalkonium chloride and Domiphen bromide were measured and quantified by their IC50 values. Among them, Cetalkonium chloride displayed stronger inhibitory activity (IC50 = 3.50 ± 0.47 μM) compared to Domiphen bromide (IC50 = 45.87 ± 16.46 μM). However, Decamethonium bromide showed no inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro even under the highest concentration of 100 μM (Fig. 3). Although the seven compounds have the similar structures with the quaternary amine and the long alkyl chain, there is still a significant difference in their inhibitory activities (Table 1). Through comparing the relation between the cLogP and IC50 values, we speculate that the inhibitory activities of these compounds against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro are related to the cLogP value, carbon chain length and aryl position, which suggests that these compounds with the quaternary amine and the long alkyl chain have the potential to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. To further study the inhibitory mechanism of this class of compounds on SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, we chose Thonzonium bromide with the strongest inhibitory effect on the protease for the next study. The fluorescence quenching results showed the interaction between Thonzonium bromide and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, indicating that the action mode was static quenching (Fig. 4A-C). Further enzyme kinetics analysis showed that Thonzonium bromide is a noncompetitive inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro with the Ki of 2.62 μM (Fig. 4D). Meanwhile, Thonzonium bromide keeps the good inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro in the presence or absence of DTT or GSH, which proves its specific inhibition (Fig. 4E). CD spectroscopy analysis result showed that Thonzonium bromide can destroy the secondary structure of the protease (Fig. 4F). We also evaluated the effects of Thonzonium bromide over human proteases including CTRC and DPP-IV. Interestingly, Thonzonium bromide does not inhibit the activities of CTRC and DPP-IV (Fig. 5). Due to the similarity of 3CLpro in SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV-229E, the inhibitory activity of Thonzonium bromide against four proteases was determined, respectively. It was shown that Thonzonium bromide has the broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against the proteases of human coronaviruses (Fig. 6).

Taken together, Thonzonium bromide exerts the antiviral effect against SARS-CoV-2 possibly by targeting 3CLpro, which represents a potential broad-spectrum 3CLpro inhibitor for future studies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (ZD2021CY001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82141203), Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (ZY (2021-2023 )-0103).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2022.106264.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S.M., Lau E.H.Y., Wong J.Y., Xing X., Xiang N., Wu Y., Li C., Chen Q., Li D., Liu T., Zhao J., Liu M., Tu W., Chen C., Jin L., Yang R., Wang Q., Zhou S., Wang R., Liu H., Luo Y., Liu Y., Shao G., Li H., Tao Z., Yang Y., Deng Z., Liu B., Ma Z., Zhang Y., Shi G., Lam T.T.Y., Wu J.T., Gao G.F., Cowling B.J., Yang B., Leung G.M., Feng Z. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szcześniak D., Gładka A., Misiak B., Cyran A., Rymaszewska J. The SARS-CoV-2 and mental health: From biological mechanisms to social consequences. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021;104:110046. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Z., Lian X., Su X., Wu W., Marraro G.A., Zeng Y. From SARS and MERS to COVID-19: a brief summary and comparison of severe acute respiratory infections caused by three highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Respir. Res. 2020;21(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01479-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong M., Su H., Zhao W., Xie H., Shao Q., Xu Y. What coronavirus 3C-like protease tells us: From structure, substrate selectivity, to inhibitor design. Med. Res. Rev. 2021;41(4):1965–1998. doi: 10.1002/med.21783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao K., Tzou P.L., Nouhin J., Gupta R.K., de Oliveira T., Kosakovsky Pond S.L., Fera D., Shafer R.W. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021;22(12):757–773. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen R.E., Zhang X., Case J.B., Winkler E.S., Liu Y., VanBlargan L.A., Liu J., Errico J.M., Xie X., Suryadevara N., Gilchuk P., Zost S.J., Tahan S., Droit L., Turner J.S., Kim W., Schmitz A.J., Thapa M., Wang D., Boon A.C.M., Presti R.M., O'Halloran J.A., Kim A.H.J., Deepak P., Pinto D., Fremont D.H., Crowe J.E., Jr., Corti D., Virgin H.W., Ellebedy A.H., Shi P.Y., Diamond M.S. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat. Med. 2021;27(4):717–726. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01294-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahase E. Covid-19: UK becomes first country to authorise antiviral molnupiravir. BMJ. 2021;375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahase E. Covid-19: Molnupiravir reduces risk of hospital admission or death by 50% in patients at risk. MSD reports, Bmj. 2021;375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahase E. Covid-19: Pfizer's paxlovid is 89% effective in patients at risk of serious illness, company reports. BMJ. 2021;375 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrareze P.A.G., Franceschi V.B., Mayer A.M., Caldana G.D., Zimerman R.A., Thompson C.E. E484K as an innovative phylogenetic event for viral evolution: Genomic analysis of the E484K spike mutation in SARS-CoV-2 lineages from Brazil. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., Chen H.D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.D., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shen X.R., Wang X., Zheng X.S., Zhao K., Chen Q.J., Deng F., Liu L.L., Yan B., Zhan F.X., Wang Y.Y., Xiao G.F., Shi Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., Bi Y., Ma X., Zhan F., Wang L., Hu T., Zhou H., Hu Z., Zhou W., Zhao L., Chen J., Meng Y., Wang J., Lin Y., Yuan J., Xie Z., Ma J., Liu W.J., Wang D., Xu W., Holmes E.C., Gao G.F., Wu G., Chen W., Shi W., Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillaiyar T., Manickam M., Namasivayam V., Hayashi Y., Jung S.H. An Overview of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL Protease Inhibitors: Peptidomimetics and Small Molecule Chemotherapy. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59(14):6595–6628. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L.W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegyi A., Ziebuhr J. Conservation of substrate specificities among coronavirus main proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83(Pt 3):595–599. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kneller D.W., Phillips G., O'Neill H.M., Jedrzejczak R., Stols L., Langan P., Joachimiak A., Coates L., Kovalevsky A. Structural plasticity of SARS-CoV-2 3CL M(pro) active site cavity revealed by room temperature X-ray crystallography. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):3202. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16954-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai W., Zhang B., Jiang X., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Peng J., Liu F., Li C., Li Y., Bai F., Wang H., Cheng X., Cen X., Hu S., Yang X., Wang J., Liu X., Xiao G., Jiang H., Rao Z., Zhang L., Xu Y., Yang H., Liu H. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science (New York N.Y.) 2020;368:1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368(6489):409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su H., Yao S., Zhao W., Li M., Liu J., Shang W., Xie H., Ke C., Hu H., Gao M., Yu K., Liu H., Shen J., Tang W., Zhang L., Xiao G., Ni L., Wang D., Zuo J., Jiang H., Bai F., Wu Y., Ye Y., Xu Y. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities in vitro of Shuanghuanglian preparations and bioactive ingredients. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41(9):1167–1177. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0483-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao S., Sylvester K., Song L., Claff T., Jing L., Woodson M., Weiße R.H., Cheng Y., Schäkel L., Petry M., Gütschow M., Schiedel A.C., Sträter N., Kang D., Xu S., Toth K., Tavis J., Tollefson A.E., Müller C.E., Liu X., Zhan P. Discovery and Crystallographic Studies of Trisubstituted Piperazine Derivatives as Non-Covalent SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors with High Target Specificity and Low Toxicity. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65(19):13343–13364. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen D.R., Allerton C.M.N., Anderson A.S., Aschenbrenner L., Avery M., Berritt S., Boras B., Cardin R.D., Carlo A., Coffman K.J., Dantonio A., Di L., Eng H., Ferre R., Gajiwala K.S., Gibson S.A., Greasley S.E., Hurst B.L., Kadar E.P., Kalgutkar A.S., Lee J.C., Lee J., Liu W., Mason S.W., Noell S., Novak J.J., Obach R.S., Ogilvie K., Patel N.C., Pettersson M., Rai D.K., Reese M.R., Sammons M.F., Sathish J.G., Singh R.S.P., Steppan C.M., Stewart A.E., Tuttle J.B., Updyke L., Verhoest P.R., Wei L., Yang Q., Zhu Y. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021;374(6575):1586–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alugubelli Y.R., Geng Z.Z., Yang K.S., Shaabani N., Khatua K., Ma X.R., Vatansever E.C., Cho C.C., Ma Y., Xiao J., Blankenship L.R., Yu G., Sankaran B., Li P., Allen R., Ji H., Xu S., Liu W.R. A systematic exploration of boceprevir-based main protease inhibitors as SARS-CoV-2 antivirals. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022;240 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry J.A., Hill I.R. Fatal interaction between ritonavir and MDMA. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1751–1752. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79824-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansuri Z., Shah B., Adnan M., Chaudhari G., Jolly T. Ritonavir/Lopinavir and Its Potential Interactions With Psychiatric Medications: A COVID-19 Perspective. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22(3):20com02677. doi: 10.4088/PCC.20com02677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y., Zhang J., Duan Z., Wang N., Sun X., Zhang Y., Fu L., Liu K., Yang Y., Pan S., Shi Y., Zeng H., Guo G., Lai R., Zou Q. High-throughput screening and evaluation of repurposed drugs targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2021;6(1):356. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkar A., Mandal K. Repurposing an Antiviral Drug against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021;60(44):23492–23494. doi: 10.1002/anie.202107481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao S., Huang T., Song L., Xu S., Cheng Y., Cherukupalli S., Kang D., Zhao T., Sun L., Zhang J., Zhan P., Liu X. Medicinal chemistry strategies towards the development of effective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022;12(2):581–599. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang T., Sun L., Kang D., Poongavanam V., Liu X., Zhan P., Menéndez-Arias L. Search, Identification, and Design of Effective Antiviral Drugs Against Pandemic Human Coronaviruses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021;1322:219–260. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-0267-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang R., Hu Q., Wang H., Zhu G., Wang M., Zhang Q., Zhao Y., Li C., Zhang Y., Ge G., Chen H., Chen L. Identification of Vitamin K3 and its analogues as covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CL(pro) Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;183:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yousfi H., Ranque S., Cassagne C., Rolain J.M., Bittar F. Identification of repositionable drugs with novel antimycotic activity by screening the Prestwick Chemical Library against emerging invasive moulds. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020;21:314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon-Soro A., Kim D., Li Y., Liu Y., Ito T., Sims K.R., Jr., Benoit D.S.W., Bittinger K., Koo H. Impact of the repurposed drug thonzonium bromide on host oral-gut microbiomes. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2021;7(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41522-020-00181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maffucci I., Contini A. In Silico Drug Repurposing for SARS-CoV-2 Main Proteinase and Spike Proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2020;19(11):4637–4648. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murer L., Volle R., Andriasyan V., Petkidis A., Gomez-Gonzalez A., Yang L., Meili N., Suomalainen M., Bauer M., Policarpo Sequeira D., Olszewski D., Georgi F., Kuttler F., Turcatti G., Greber U.F. Identification of broad anti-coronavirus chemical agents for repurposing against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Curr. Res. Virol. Sci. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.crviro.2022.100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho B.L., Cheng S.C., Shi L., Wang T.Y., Ho K.I., Chou C.Y. Critical Assessment of the Important Residues Involved in the Dimerization and Catalysis of MERS Coronavirus Main Protease. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L., Gui C., Luo X., Yang Q., Günther S., Scandella E., Drosten C., Bai D., He X., Ludewig B., Chen J., Luo H., Yang Y., Yang Y., Zou J., Thiel V., Chen K., Shen J., Shen X., Jiang H. Cinanserin is an inhibitor of the 3C-like proteinase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and strongly reduces virus replication in vitro. J. Virol. 2005;79(11):7095–7103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7095-7103.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L., Li J., Luo C., Liu H., Xu W., Chen G., Liew O.W., Zhu W., Puah C.M., Shen X., Jiang H. Binding interaction of quercetin-3-beta-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CL(pro): structure-activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14(24):8295–8306. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galasiti Kankanamalage A.C., Kim Y., Damalanka V.C., Rathnayake A.D., Fehr A.R., Mehzabeen N., Battaile K.P., Lovell S., Lushington G.H., Perlman S., Chang K.O., Groutas W.C. Structure-guided design of potent and permeable inhibitors of MERS coronavirus 3CL protease that utilize a piperidine moiety as a novel design element. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;150:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee C.C., Kuo C.J., Ko T.P., Hsu M.F., Tsui Y.C., Chang S.C., Yang S., Chen S.J., Chen H.C., Hsu M.C., Shih S.R., Liang P.H., Wang A.H. Structural basis of inhibition specificities of 3C and 3C-like proteases by zinc-coordinating and peptidomimetic compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(12):7646–7655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807947200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma C., Hu Y., Townsend J.A., Lagarias P.I., Marty M.T., Kolocouris A., Wang J. Ebselen, Disulfiram, Carmofur, PX-12, Tideglusib, and Shikonin Are Nonspecific Promiscuous SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020;3(6):1265–1277. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J., Zhang Y., Pang H., Li S.J. Heparin interacts with the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and inhibits its activity. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022;267(Pt 2) doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2021.120595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lakowicz J.R., Weber G. Quenching of fluorescence by oxygen. A probe for structural fluctuations in macromolecules. Biochemistry. 1973;12(21):4161–4170. doi: 10.1021/bi00745a020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abian O., Ortega-Alarcon D., Jimenez-Alesanco A., Ceballos-Laita L., Vega S., Reyburn H.T., Rizzuti B., Velazquez-Campoy A. Structural stability of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and identification of quercetin as an inhibitor by experimental screening. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;164:1693–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Böhm G., Muhr R., Jaenicke R. Quantitative analysis of protein far UV circular dichroism spectra by neural networks. Protein Eng. 1992;5(3):191–195. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenfield N.J. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1(6):2876–2890. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou L.W., Wang P., Qian X.K., Feng L., Yu Y., Wang D.D., Jin Q., Hou J., Liu Z.H., Ge G.B., Yang L. A highly specific ratiometric two-photon fluorescent probe to detect dipeptidyl peptidase IV in plasma and living systems. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017;90:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.11.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drayman N., DeMarco J.K., Jones K.A., Azizi S.A., Froggatt H.M., Tan K., Maltseva N.I., Chen S., Nicolaescu V., Dvorkin S., Furlong K., Kathayat R.S., Firpo M.R., Mastrodomenico V., Bruce E.A., Schmidt M.M., Jedrzejczak R., Muñoz-Alía M., Schuster B., Nair V., Han K.Y., O'Brien A., Tomatsidou A., Meyer B., Vignuzzi M., Missiakas D., Botten J.W., Brooke C.B., Lee H., Baker S.C., Mounce B.C., Heaton N.S., Severson W.E., Palmer K.E., Dickinson B.C., Joachimiak A., Randall G., Tay S. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2021;373(6557):931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ware W.R. Oxygen quenching of fluorescence in solution: an experimental study of the diffusion process. J. Phys. Chem. 1962;66(3):455–458. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karges J., Kalaj M., Gembicky M., Cohen S.M. Re(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes as Coordinate Covalent Inhibitors for the SARS-CoV-2 Main Cysteine Protease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021;60(19):10716–10723. doi: 10.1002/anie.202016768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., Du R., Zhao J., Jin Y., Fu S., Gao L., Cheng Z., Lu Q., Hu Y., Luo G., Wang K., Lu Y., Li H., Wang S., Ruan S., Yang C., Mei C., Wang Y., Ding D., Wu F., Tang X., Ye X., Ye Y., Liu B., Yang J., Yin W., Wang A., Fan G., Zhou F., Liu Z., Gu X., Xu J., Shang L., Zhang Y., Cao L., Guo T., Wan Y., Qin H., Jiang Y., Jaki T., Hayden F.G., Horby P.W., Cao B., Wang C. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iketani S., Forouhar F., Liu H., Hong S.J., Lin F.Y., Nair M.S., Zask A., Huang Y., Xing L., Stockwell B.R., Chavez A., Ho D.D. Lead compounds for the development of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):2016. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Declercq J., Van Damme K.F.A., De Leeuw E., Maes B., Bosteels C., Tavernier S.J., De Buyser S., Colman R., Hites M., Verschelden G., Fivez T., Moerman F., Demedts I.K., Dauby N., De Schryver N., Govaerts E., Vandecasteele S.J., Van Laethem J., Anguille S., van der Hilst J., Misset B., Slabbynck H., Wittebole X., Liénart F., Legrand C., Buyse M., Stevens D., Bauters F., Seys L.J.M., Aegerter H., Smole U., Bosteels V., Hoste L., Naesens L., Haerynck F., Vandekerckhove L., Depuydt P., van Braeckel E., Rottey S., Peene I., Van Der Straeten C., Hulstaert F., Lambrecht B.N. Effect of anti-interleukin drugs in patients with COVID-19 and signs of cytokine release syndrome (COV-AID): a factorial, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9(12):1427–1438. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00377-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dejnirattisai W., Shaw R.H., Supasa P., Liu C., Stuart A.S.V., Pollard A.J., Liu X., Lambe T., Crook D., Stuart D.I., Mongkolsapaya J., Nguyen-Van-Tam J.S., Snape M.D., Screaton G.R. Reduced neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 omicron B.1.1.529 variant by post-immunisation serum. The Lancet. 2022;399(10321):234–236. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02844-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z.R., Zhang H.Q., Li X.D., Deng C.L., Wang Z., Li J.Q., Li N., Zhang Q.Y., Zhang H.L., Zhang B., Ye H.Q. Generation and characterization of Japanese encephalitis virus expressing GFP reporter gene for high throughput drug screening. Antiviral Res. 2020;182 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niu H., Ma C., Cui P., Shi W., Zhang S., Feng J., Sullivan D., Zhu B., Zhang W., Zhang Y. Identification of drug candidates that enhance pyrazinamide activity from a clinical compound library. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2017;6(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/emi.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayes M.P., Soto-Velasquez M., Fowler C.A., Watts V.J., Roman D.L. Identification of FDA-Approved Small Molecules Capable of Disrupting the Calmodulin-Adenylyl Cyclase 8 Interaction through Direct Binding to Calmodulin. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018;9(2):346–357. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vitaku E., Smith D.T., Njardarson J.T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57(24):10257–10274. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu C., El Qaidi S., McDonald P., Roy A., Hardwidge P.R. YM155 Inhibits NleB and SseK Arginine Glycosyltransferase Activity. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):253. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.