Abstract

COVID-19 led to a surge in employees experiencing New Ways of Working (NWW), as many had to work from home supported by ICT. This paper studies how experiencing NWW during COVID-19 affected job-related affective well-being (JAWS) for a sample of employees of the Dutch working population. Hypotheses are tested using Preacher and Hayes' (Behav Res Methods 40 (3):879–891, 2008) bootstrap method, including technostress, need for recovery and work engagement as serial mediators. The results show that higher levels of NWW relate to higher JAWS, to more feelings of positive well-being (PAWS), and less feelings of negative well-being (NAWS). Much of these relations is indirect, via reduced technostress and need for recovery, and increased work engagement. Distinguishing the separate facets of NWW and their relations to PAWS/NAWS, the results show that NWW facets management of output, access to colleagues and access to information directly relate to less negative well-being. However, as the NWW facet time- and location-independent work negatively relates to feelings of positive well-being, NWW as a bundle of facets is not a set-and-forget strategy. Therefore, this study recommends that NWW be supplemented with regular monitoring of employees’ well-being, technostress, need for recovery and work engagement.

Keywords: New ways of working, Employee well-being, COVID-19, Technostress, Need for recovery, Work engagement

1. Introduction

Forced by the COVID-19 outbreak, the adoption of New Ways of Working (NWW) practices has suddenly become more widespread than ever (e.g. Brynjolfsson et al. 2020; Ting et al., 2020). NWW are a bundle of human resource management (HRM) practices that provide employees with more flexibility, autonomy and freedom regarding when, where, how, and how much to work (e.g. Gerards et al., 2021; Peters et al., 2014). Under normal (pre-pandemic) circumstances, NWW are known to relate positively to several employee outcomes such as work engagement (Gerards et al., 2018), informal learning (Gerards et al., 2020) and intrapreneurial behaviour (Gerards et al., 2021). Because our understanding of employee level outcomes of NWW is still considered to be limited (e.g. Gerards et al., 2021), and because NWW have proliferated due to COVID-19, the objective of our study is to contribute to our understanding of employee outcomes of NWW. As NWW rely on intensive use of information and communication technology (ICT) (e.g. Gerards et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2014), which in turn has been related to negative well-being effects on employees (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2020) in the form of (for instance) ‘technostress’ (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2008), we pursue our objective by investigating the relation between NWW and employees' job-related affective well-being (JAWS), accounting for technostress, the need for recovery and work engagement as potential mediators.

Gerards et al. (2018) define NWW as consisting of five facets: (1) time- and location-independent work, (2) management of output, (3) access to organizational knowledge, (4) flexibility in working relations and (5) freely accessible open workplaces. As such, NWW (most notably the first three facets) have much in common with its older sibling concepts of teleworking or telecommuting that also heavily rely on ICT. Although many positive effects of telework and work-related ICT use have been documented (e.g. Anderson et al., 2015; Charalampous et al., 2019; Ipsen et al., 2021; Taser et al., 2022), evidence that teleworking and the increased reliance on work-related ICT (on which NWW depend) can also have adverse effects on aspects of employee well-being is also abundant. For instance, the time spent handling e-mail has been found to increase the feeling of being overloaded (e.g. Barley et al., 2011; Reinke & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2014). Relatedly, the fear of missing out on an email or any information from a peer, a manager, or a client can also affect the use of technology in the workplace or at home, and negatively impacts well-being and motivation (Budnick et al., 2020). This constant feeling of preoccupation with, and urge to reply to work-related messages coming from all types of ICT has been related to lower psychological and physical health (Barber & Santuzzi, 2014; Kotera & Vione, 2020). Similarly, pervasive ICT and the feeling of always being connected are known causes of technostress (e.g. Ayyagari et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2008). The often-paradoxical findings in telework studies led Boell et al. (2016, p. 128) to conclude that it is still undecided whether telework “is ultimately a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ thing”.

As millions of employees started teleworking due to COVID-19 and technology took a leading role in their daily – working – lives (Ting et al., 2020), it didn't take long before studies emerged that specifically link COVID-19 driven teleworking to outcomes such as technostress, work engagement or well-being. For instance (an exhaustive overview is beyond the scope of this paper), studies showing that teleworking during COVID-19 is associated with more, respectively less technostress (Molino et al., 2020; Oksanen et al., 2021, respectively Taser et al., 2022), with lower work engagement (Parent-Lamarche, 2022) or with higher well-being (Parent-Lamarche & Boulet, 2021) and higher flow (Taser et al., 2022).

However, we are not aware of any studies specifically linking NWW during COVID-19 to a validated job-related well-being scale. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to relate NWW during COVID-19 to employee well-being. We do so using a sample of employees from the Dutch working population. Building on the existing empirical literature, we test the relation between NWW and employees’ job-related well-being, while taking into account technostress, the need for recovery and work engagement, respectively, as potential mediators in a serial mediation model. Our study uses well established scales for the main variables in our model: NWW from Gerards et al. (2018; 2020; 2021), Job-related Affective Well-being (JAWS) from Van Katwyk et al. (2000); Technostress from Wang et al. (2008), Need for Recovery (NFR) from Van Veldhoven and Broersen (2003), and the UWES-9 for work engagement (Schaufeli et al., 2006).

Importantly, to account for the possibility that some employees were already more used to NWW prior to COVID-19 than other workers, we control for the change in number of days that employees telework since COVID-19. Crucially, besides the main results that this study will present from the serial mediation analysis using JAWS as total variable, this study will also present results from additional analyses using its separate components ‘positive affect’ (PAWS) and ‘negative affect’ (NAWS). Moreover, in addition to estimating the serial mediation model using NWW as aggregate variable, this study will also present additional estimation results for all combinations of different NWW facets and PAWS and NAWS, to uncover to what extent each NWW facet relates to feelings of positive and negative well-being.

2. Conceptualization and hypotheses development

2.1. New Ways of Working

New Ways of Working (NWW) are a fairly recent phenomenon that bundle several HRM practices to grant employees more autonomy and freedom to work independent of time and place, supported by ICT (e.g. De Leede, 2016; Gerards et al., 2021). We briefly describe the five facets of NWW that Gerards et al. (2018; 2020; 2021) distinguish, and refer to Gerards et al. (2018) for more details.

The first facet, time-and location-independent work, refers to employee autonomy in terms of time and place of work, such as the freedom to work at home if, for example, one needs a more private and calmer environment (Gerards et al., 2018; Halford, 2005). The second facet, management of output, refers to employee autonomy in terms of work process. In absence of (frequent) office presence by employees, managers are mainly focused on results and output, rather than on how employees organized their work to achieve those results (Gerards et al., 2018). The third facet, access to organizational knowledge, refers to the easy access that employees have to organizational knowledge at any time on any device (Baane et al., 2010; Gerards et al., 2018), and to easy and quick methods of connecting, communicating and sharing knowledge with colleagues and superiors (Gerards et al., 2018, 2021). The fourth facet, flexibility in working relations, refers to flexibility of the employment relationship (Baane et al., 2010). This facet expresses the extent to which employees have influence over their work-life balance. For instance, with regard to decreasing or increasing their contractually agreed number of working hours as they prefer depending on their career ambitions or personal circumstances (Gerards et al., 2018, 2021). The fifth and final facet, freely accessible open workplace, refers to the open-plan offices often encountered in organizations using NWW (Gerards et al., 2018).

2.2. New Ways of Working and well-being

NWW represent a significant change in work organization and work environment for employees as compared to traditional methods of work organization and, therefore, can significantly impact employees’ well-being (López-Cabarcos et al., 2020). Following recommendations of López-Cabarcos et al. (2020) and Kotera and Vione (2020), our study contributes to the literature by responding to the need of research on the influence that NWW can have on well-being.

On the one hand, the literature contains findings that the use of ICT (on which NWW heavily relies) can lower the levels of mental health and mental well-being (e.g. Rasmussen et al., 2020), deteriorate the home-work boundary, and increase fatigue and mental workload (Kotera & Vione, 2020). On the other hand, recent literature has mostly found that teleworking can have positive impacts on one's well-being (Anderson et al., 2015; Charalampous et al., 2019; Ipsen et al., 2021) and can improve employees' physical and mental health – sometimes using engagement as a mediator (López-Cabarcos et al., 2020), as we also do. Taken together, we expect that NWW are related to well-being, without a priori formulating expectations regarding the sign of the effect. Therefore, we predict the following:

H1

NWW are related to well-being.

2.3. Technostress as a mediator

‘Technostress’ was first coined in 1984 in the book “Technostress: The Human Cost of the Computer Revolution” (Brod, 1984). Brod defines Technostress as “a modern disease of adaptation caused by an inability to cope with the new computer technologies in a healthy manner.” (Brod, 1984, p.16). This definition has evolved over time and the most recent and widely accepted definition is that technostress is the stress that information and communication technology users experience due to the use of technologies (Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008). Technostress can be broken down into subscales called ‘Technostress Creators’, coined by Tarafdar et al. (2007) as techno-overload, techno-invasion, techno-complexity, techno-insecurity and techno-uncertainty (Tarafdar et al., 2007).

On the one hand, NWW are likely to affect the level of technostress that employees experience through the increased teleworking and reliance on ICT and social media communication to stay in touch with colleagues and supervisors (e.g. Molino et al., 2020; Oksanen et al., 2021; Taser et al., 2022). On the other hand, technostress is known to decrease several work-related employee level outcomes such as productivity and performance (Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008; Tarafdar et al., 2007), work satisfaction (Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008; Tarafdar et al., 2007) and organizational commitment (Hwang & Cha, 2018; Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008; Tarafdar et al., 2007). Furthermore, technostress is considered to lead to increased stress levels (Hwang & Cha, 2018; Molino et al., 2020; Tarafdar et al., 2007). These relations make technostress a likely mediator between NWW and employee well-being. Therefore, we predict:

H2

Technostress mediates the relation between NWW and well-being.

2.4. The need for recovery as a mediator

The need for recovery is defined as “the need to recuperate from work-induced fatigue, experienced after a day of work” (Jansen et al., 2002, p. 322). As technostress has been shown to be a major source of stress, reduced performance, and increased work-home conflict (e.g. Hwang & Cha, 2018; Molino et al., 2020; Tarafdar et al., 2007), it likely leads to an increased need to recover from work-induced fatigue. In turn, a higher need for recovery reduces well-being (e.g. Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006). These relations make the need for recovery a likely mediator between on the one hand NWW and technostress, and on the other hand work engagement and well-being. This leads us to the following prediction:

H3

The need for recovery mediates the relation between NWW and well-being.

2.5. Work engagement as a mediator

Work engagement is defined as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74) and is relevant for employee well-being for several reasons (Sonnentag, 2003). For instance, it has been shown to promote positive work affect (Rothbard, 2001) and to be a significant predictor of JAWS (Adil & Kamal, 2016). Combined with the knowledge that NWW positively relate to work engagement (Gerards et al., 2018), this makes the case for work engagement as potential mediator between NWW and JAWS. Moreover, it is known that day-level recovery is positively related to day-level work engagement the next day (Sonnentag, 2003), suggesting that the need for recovery may be negatively related to work engagement. Therefore, we serially position work engagement in our model after the need for recovery and before JAWS. This leads to the following prediction:

H4

Work engagement positively mediates the relation between NWW and well-being.

2.6. Research model overview

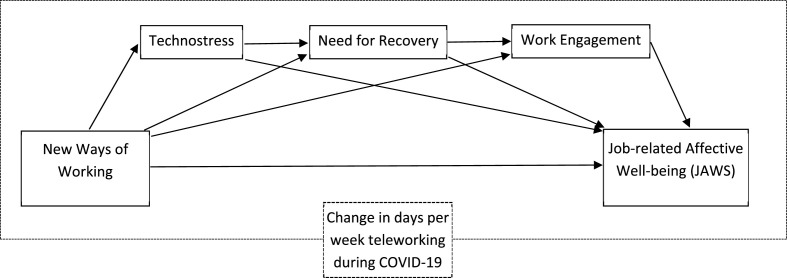

Fig. 1 summarizes our research model, which will be tested including the control variables gender, age, education level, and job type. Crucially, we also control for the change in number of days that employees telework since COVID-19, to account for the possibility that some employees were already more used to NWW prior to COVID-19 than other workers. Section 3.2 discusses the measurement and construction of our variables, including a brief rationale for the inclusion of each of our control variables.

Fig. 1.

Overview of our research model between NWW and Job-related Affective Well-being (JAWS).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data collection and sample

An electronic survey was purpose-built for our study. The survey was conducted in cooperation with Etil Research Group,1 who fielded the survey via an online panel of the Dutch population from late July through early August of 2020. Of the 11,564 members of the panel, 360 responded. Of these, only those in paid employment were routed to continue the survey, resulting in 275 respondents who continued. Excluded from the analyses were 89 respondents whom had missing information on any of the items used to construct the variables for our analyses. Also excluded were three more respondents whose age was above the official retirement age of 67.

The survey included a retrospective question that asks how many days per week respondents on average worked from home before the COVID-19 crisis. We want to compare this to the average number of days per week they responded to work from home in the month before the survey (thus during the COVID-19 crisis). The difference being the increase in days working from home due to the COVID-19 crisis. However, we can only ascribe this difference in days working from home to the COVID-19 crisis if we can exclude those respondents who (1) changed jobs or (2) (re)-started working, in the period between the start of the crisis and the month in which they completed the survey. For the purpose of our study, March 12, 2020 is considered the start of the COVID-19 crisis, as this was the day the Dutch government issued the ‘work-from-home’ directive. Consequently, 9 observations were dropped for whom the total working tenure or tenure in their job was shorter than six respectively seven months, for those who completed the survey in July respectively August. This ensures all remaining respondents have an uninterrupted job and work history at least until before the work-from-home directive.

Our survey also included a simple ‘yes/no’ verification question, asking whether they worked from home more than usual due to COVID-19 in the month before the survey. 4 respondents were dropped who inconsistently answered ‘yes’ to working home more than usual in the month before the survey, while answering ‘0’ average days per week working from home in the month before the survey. Our final sample consists of 170 respondents.

The bottom section of Table 1 shows summary statistics of our sample. The mean age of our sample is 51.8 years, 44% of the sample is female, 58% of the sample is higher educated and 17% holds a management position.

Table 1.

Sample and variable summary statistics.

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job-related Affective Well-being Scale | ||||

| JAWS total 12 items (higher is more well-being) | 3.7 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 5.0 |

| PAWS positive affect (higher is more well-being) | 3.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| NAWS negative affect (higher is less well-being) | 2.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 4.5 |

| NWW/telework variables | ||||

| NWW average facets 1 through 4 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 5.0 |

| NWW facet 1 Time- and location-independent work | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| NWW facet 2 Management of output | 3.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| NWW facet3a Access to colleagues | 3.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| NWW facet3b Access to information | 3.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| NWW facet 4 Flexibility in working relations | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Average days per week working from home (pre-COVID-19) | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| Average days per week working from home (during-COVID-19) | 2.5 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 7.0 |

| Change in days per week working from home (during minus pre) | 2.0 | 2.0 | −1.0 | 7.0 |

| Mediating variables | ||||

| Technostress-total | 2.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.4 |

| Techno-Overload | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Techno-Invasion | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Techno-Complexity | 2.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Techno-Insecurity | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Techno-Uncertainty | 3.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Need For Recovery | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Work Engagement (UWES-9) | 4.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 7.0 |

| Sample summary statistics | ||||

| Age (in years) | 51.8 | 9.3 | 29 | 67 |

| N | % | |||

| Female | 75 | 44 | ||

| Lower-medium educational level | 72 | 42 | ||

| Higher educational level | 98 | 58 | ||

| Management position | 29 | 17 | ||

| Total N | 170 |

Note: Summary statistics based on unweighted and unstandardized sum-scores for the items of each scale.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Well-being

Well-being is measured with the 12-item Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS) (Schaufeli & van Rhenen, 2006). This is a shortened version of the original 30-item version by Van Katwyk et al. (2000). Compared to other well-being scales, JAWS has the advantage to measure the job-specific affective response while still providing a broad and precise measure of the different affect states (Van Katwyk et al., 2000). Moreover, literature has shown that “the JAWS has sufficient internal consistency reliability and provided some evidence for nomological validity” (Van Katwyk et al., 2000, p. 227). Therefore, it is the appropriate scale to use for an employee panel. Respondents are asked to indicate on a five-point Likert scale how often their job makes them feel the emotions described in the items, such as “angry” or “energetic”. Cronbach's Alpha of the 12-item total JAWS scale in our sample is high (α = 0.91). We recoded negatively phrased items such that higher values of the resulting JAWS total variable mean higher well-being.

Following for instance Anderson et al. (2015), subscales for positive affect (PAWS) and negative affect (NAWS) were constructed, consisting of respectively the positively and negatively phrased items of the total scale. Cronbach's Alphas of the PAWS 6-item subscale (α = 0.90) and NAWS 6-item subscale (α = 0.89) are high. The PAWS subscale is coded such that higher values mean higher well-being, whereas the NAWS subscale is coded such that higher values mean less well-being.

The JAWS, PAWS and NAWS variables each were constructed using a polychoric factor analysis (Holgado-Tello et al., 2010) followed by regression scoring to calculate the total scale score. Moreover, the total scale scores were standardized to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one before our analyses.

3.2.2. New Ways of Working

NWW is measured using the 15-items from Gerards et al. (2021), which is an expansion over the 10-item version developed by Gerards et al. (2018). These 15 items comprise the five NWW subscales that measure the facets of ‘time- and location-independent work’, ‘management of output’, ‘access to organizational knowledge’, ‘flexibility in working relations’, and ‘freely accessible open workplace’. However, only the 13 items from facets 1 through 4 are used, because the fifth facet deals with the physical arrangement of the office-building and is not very meaningful in our context of a government issued work-from-home directive. Table A1 in the appendix shows all the items. Respondents indicated the degree to which each statement applied to their work situation on a five-point Likert scale from “Not at all” to “Very high”. Cronbach's Alpha of this 13-item NWW scale is high (α = 0.92). The aggregate NWW scale has been calculated by means of polychoric factor analysis, regression scoring and subsequent standardization.

Prior to constructing the separate NWW facet subscales, several statistical tests were performed to verify that performing a factor analysis is appropriate. Bartlett's test of sphericity turned out significant (p = 0.000) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy is 0.876, both of which indicate that we can proceed with factor analysis (see Howard (2016) for details on these tests). Next, we performed a principal factors analysis on the 13 items of the NWW scale used for this article, and perform a visual inspection of the resulting scree plot that plots the eigenvalues after each factor. This showed a second kink at the fifth factor, in line with the five factor solution that Gerards et al. (2021) found for the first 13 facets of NWW. As we believe that the NWW facets are correlated, we use an oblique oblimin rotation and factor loading cut-off of 0.35 to obtain the results displayed in Table A2 in the appendix. These results also confirm the five factor solution for these 13 items as found by Gerards et al. (2021). Because our sample size is relatively modest (170 observations) and the criterion for what constitutes ‘excessive’ cross-loadings is still debated (Howard, 2016), we ignore the two relatively small cross-loadings by items 4 and 12 on factor 3. Hence, we base the construction of our separate NWW facets only on the items' primary factor loadings as shown in Table A2.

Thus, we measure the subscale for the first NWW facet (time- and location-independent work) using items 1 through 3 (α = 0.86); the subscale for the second NWW facet (management of output) using items 4 through 6 (α = 0.85); the subscale for NWW facet 3a (access to colleagues) using items 7 through 9 (α = 0.84); the subscale for NWW facet 3b (access to information) using items 10 and 11 (α = 0.90) and the subscale for the fourth NWW facet (flexibility in working relations) using items 12 and 13 (α = 0.78). Each NWW subscale is calculated by means of polychoric factor analysis, regression scoring and subsequent standardization.

3.2.3. Technostress

Following Wang et al. (2008), Technostress is measured using 24-items. These cover the five technostress creators: ‘techno-overload’, ‘techno-invasion’, ‘techno-complexity’, ‘techno-invasion’, and ‘techno-uncertainty’ (see Tarafdar et al., 2007). Example items are ‘I am forced by this technology to work much faster.‘, ‘I often find it too complex for me to understand and use new technologies.‘, and ‘There are constant changes in computer software in our organization.’ Respondents answered the items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. Cronbach's Alpha of the 24-item Technostress scale is high (α = 0.94). The total Technostress scale score was calculated by means of polychoric factor analysis, regression scoring and subsequent standardization.

3.2.4. Need for recovery

The need for recovery was measured using the 11-item ‘Need for Recovery scale’ (see Van Veldhoven and Broersen (2003) for the history, quality and validity of the scale). Respondents had to answer ‘No’ (coded as 0) or ‘Yes’ (coded as 1) to 11 items such as “I find it difficult to relax at the end of a working day” (Van Veldhoven & Broersen, 2003, p. i4). Cronbach's Alpha of this scale is high (α = 0.89). We calculated the average of these 11 dichotomous items and subsequently standardized these before the analyses.

3.2.5. Work engagement

Work engagement was measured using the 9-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Respondents had to indicate how often they experienced each feeling described in the 9 items on a seven-point scale from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’. Example items are ‘When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work’ and ‘I am enthusiastic about my job’. Cronbach's Alpha of the UWES-9 is high (α = 0.96). The total UWES-9 scale score was calculated by means of polychoric factor analysis, regression scoring and subsequent standardization.

3.2.6. Control variables

Several individual level control variables are included in the analyses. First, a gender dummy (1 if female) is included as women are shown to experience slightly lower levels of well-being than men (Wilks & Neto, 2013). Second, as well-being can vary with age (e.g. Mäkikangas et al., 2016; Wilks & Neto, 2013) respondents’ age in years is included. Third, employees are distinguished from managers, as more research about heterogeneous well-being outcomes for employees and managers is a recognized research priority (Ipsen et al., 2021). Therefore, a management dummy variable (1 if in a management job) is included. Fourth, as we observe only few studies that inform the literature on heterogeneous effects of education level on job-related well-being, we control for the education level using a dummy variable (1 if higher educated).

Lastly yet importantly, we control for the change in number of days that employees telework since COVID-19, to account for the possibility that some employees were already more used to NWW prior to COVID-19 than other workers. This variable is constructed as a difference variable between the average number of days respondents worked from home before and during the COVID-19 crisis (as explained in Section 3.1).

3.3. Variable descriptives and correlations

Table 1 shows summary statistics for the variables in our study. Of note are the high mean values for the NWW facets time- and location-independent work (2.9), management of output (3.6), access to information (3.8) and flexibility in working relations (3.0), as compared to the mean values (respectively 2.2, 3.2, 3.3 and 2.8) that Gerards et al. (2021) found for these facets in another sample of the Dutch population, collected in 2018. This is likely signalling the COVID-19 driven widespread adoption of NWW practices, although we cannot rule out contributions by other factors, such as potentially upward trending popularity of NWW since 2018, or sample differences.

Next, it can be observed that respondents reported working from home on average 0.6 days per week prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This had increased to an average of 2.5 days per week during the pandemic – a difference that is highly significant (p = 0.0000 on a two-sided t-test). The mean change is an increase in 2.0 days working from home.

Table 2 shows the correlations between the variables, displaying only correlations significant at the 1% level. Note the positive correlations between NWW aggregate and JAWS (0.39) and PAWS (0.35), and the negative correlation between NWW aggregate and NAWS (−0.32).

Table 2.

Correlations between main variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. JAWS-Total | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. PAWS | 0.86 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. NAWS | −0.87 | −0.50 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Technostress | 0.31 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. NWW Aggregate (Facets 1–4) | 0.39 | 0.35 | −0.32 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 6. NWW F1 Time & loc.-indep. Work | 0.85 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 7. NWW F2 Management of output | 0.42 | 0.35 | −0.37 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 8. NWW F3a Access to colleagues | 0.43 | 0.34 | −0.40 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 9. NWW F3b Access to information | 0.33 | 0.28 | −0.30 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 10. NWW F4 Flexible. In working relations | 0.35 | 0.32 | −0.28 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 11. Change in days per week telework | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 12. Need for Recovery | −0.49 | −0.36 | 0.49 | 0.29 | −0.22 | −0.21 | −0.25 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 13. Work Engagement | 0.72 | 0.84 | −0.41 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.32 | −0.30 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 14. Age | 0.28 | 0.21 | −0.27 | 0.20 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 15.1 if female | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16.1 if managing position | −0.21 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 17.1 if high educated | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.35 | −0.23 | 1.00 |

Note. Only correlations with p < 0.01 shown.

Similar correlation patterns can be observed for the separate NWW facets, with the exception of the facet time- and location-independent work, which is not significantly correlated to JAWS, PAWS or NAWS. Also, note that all NWW facets are positively related to the change in days per week telework, and that the change in days per week telework is positively correlated with being higher educated.

Regarding our mediators, we observe a positive correlation between technostress and NAWS (0.31), but none between technostress and JAWS, PAWS or any of the NWW variables. Further, technostress is positively correlated with the need for recovery (0.29). In turn, the need for recovery is negatively related to JAWS (−0.49), PAWS (−0.36), NWW aggregate (−0.22) and the facets management of output (−0.21) and access to colleagues (−0.25). The need for recovery is positively related to NAWS (0.49). Next, work engagement is positively related to JAWS (0.72), PAWS (0.84), NWW aggregate (0.36) and the separate facets (except time- and location-independent work). Work engagement is negatively related to NAWS (−0.41) and the need for recovery (−0.30). The signs of these significant correlations are in line with expectations.

Among the control variables, only age appears to be related to well-being – JAWS (0.28), PAWS (0.21), and NAWS (−0.27) – while gender, education, and whether employees are managers were not found to be significantly related to well-being. Education is positively related to the change in days per week telework (0.35) and to most NWW facets.

3.4. Estimation method and a note on potential common method variance

Our hypotheses are tested using the Preacher and Hayes (2008) bootstrap method for mediation analysis, using the PROCESS procedure version 3.5.3 in SPSS (Hayes, 2017). Specifically, we estimated the serial mediation model (number 6) for all the models we report in Section 4. The Preacher and Hayes (2008) method uses OLS regressions to estimate all coefficients, and bootstrapping to determine the confidence intervals for the direct and indirect effects.

Using cross-sectional data could lead to common method variance (CMV) that may bias the correlations between our variables (e.g. Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Following Fuller et al. (2016), a Harman one-factor test was performed to assess if this should concern us. An exploratory factor analysis of all items underlying our subjective measures shows that 22.9% of the variance is explained by the first factor. This is well below the commonly accepted 50% and indicates that there is no reason to worry that CMV might unduly bias our results (Fuller et al., 2016).

4. Results

4.1. Main results on the relation between NWW and JAWS via technostress, need for recovery and work engagement

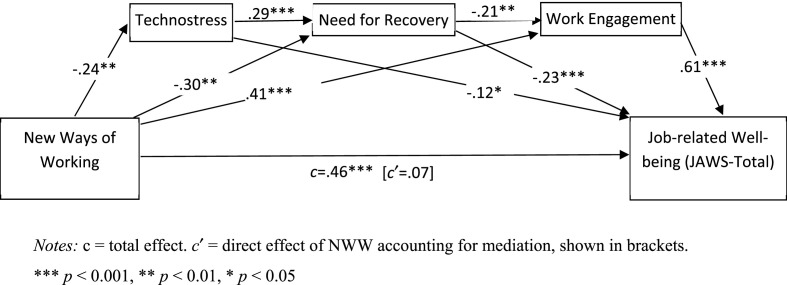

Fig. 2 shows the estimation results of the relation between NWW aggregate and JAWS. NWW are significantly positively related to well-being (c = 0.46), confirming Hypothesis 1. However, the direct effect of NWW on well-being is insignificant and the coefficient (c′ = 0.07) is much smaller than the total effect. This suggest that the relation between NWW and well-being is fully mediated by our hypothesized mediators, which we turn to next.

Fig. 2.

Serial mediation model of direct and indirect effects of NWW on Job-related Well-being (JAWS-Total).

Notes: c = total effect. C′ = direct effect of NWW accounting for mediation, shown in brackets.

∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

With regard to our mediators, we find significant negative relations between NWW and technostress (β = - 0.24) and NWW and the need for recovery (β = - 0.30), as well as a significant positive relation between NWW and work engagement (β = 0.41). In turn, we find significant negative relations between technostress and well-being (β = - 0.12) and the need for recovery and well-being (β = - 0.23), as well as a significant positive relation between work engagement and well-being (β = 0.61). Additionally, we observe a significant positive relation between technostress and the need for recovery and a significant negative relation between the need for recovery and work engagement.

To formally assess which indirect paths are significant in mediating between NWW and well-being, we look at the bootstrapped confidence intervals of the indirect effects (see Table A3 for details). Whenever a confidence interval does not include zero, the respective indirect path is significant. We find significant positive indirect effects of NWW on JAWS via the need for recovery and via work engagement, confirming Hypotheses 3 and 4. Moreover, the indirect paths indicating serial mediation via technostress and need for recovery (path 4 in Table A3), via need for recovery and work engagement (path 6 in Table A3), and via technostress, need for recovery and work engagement (path 7 in Table A3) are all significant. However, no significant indirect relation between NWW and JAWS via only technostress is found. Hence, Hypothesis 2 cannot yet be confirmed based on this model.

Regarding our control variables, positive relations are observed between having a management position and technostress and between the change in number of days teleworking and technostress. Further, being female is positively related to the need for recovery and age is positively related to work engagement. Moreover, positive relations are observed between both age and the change in number of days teleworking and JAWS. This suggests that the larger the difference in number of days teleworking before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the higher total well-being. We find no heterogeneous effects on employee well-being for regular employees versus managers or by education level. Altogether, the estimated model explains 68% of the variance in JAWS and is highly significant (p < 0.001).

4.2. Results of additional analyses differentiating feelings of positive and negative affective well-being

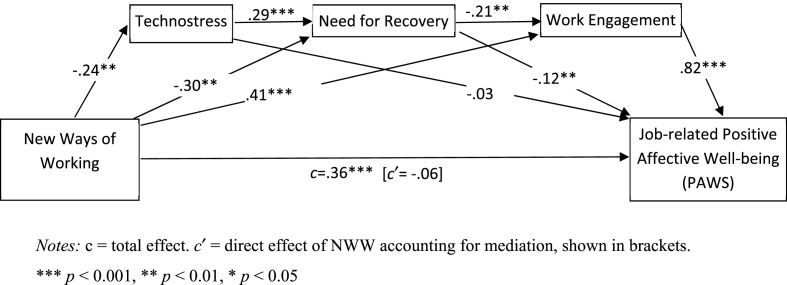

When looking at Fig. 3 (and the corresponding Table A4) – which show the results of the same analysis but with positive affective well-being (PAWS) as dependent variable instead of total well-being (JAWS) – nothing noteworthy different is observed. This model explains 75% of the variance in PAWS and is highly significant (p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Serial mediation model of direct and indirect effects of NWW on Positive Affect (PAWS).

Notes: c = total effect. C′ = direct effect of NWW accounting for mediation, shown in brackets.

∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

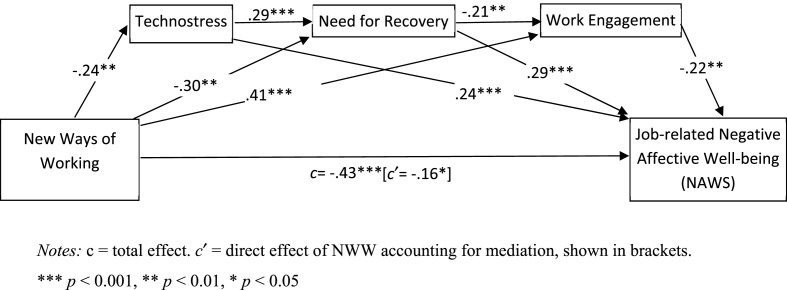

However, Fig. 4 (and the corresponding Table A5) – which use negative affective well-being (NAWS) as dependent variable – show some noteworthy additional outcomes. NWW are significantly negatively related to NAWS (c = −0.43). Moreover, the direct effect of NWW on NAWS remains significant, although the coefficient (c′ = −0.16) is quite a bit smaller than the total effect. This suggest that the relation between NWW and NAWS is only partially mediated. With regard to our mediators, we find significant positive relations between technostress and NAWS (β = 0.24) and the need for recovery and NAWS (β = 0.29), as well as a significant negative relation between work engagement and NAWS (β = - 0.22). A noteworthy finding regarding the indirect effects is that we now also observe a significant mediating effect of only technostress (path 1 in Table A5), confirming Hypothesis 2 when applied to NAWS. This model explains 47% of the variance in NAWS and is highly significant (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Serial mediation model of direct and indirect effects of NWW on Negative Affect (NAWS).

Notes: c = total effect. C′ = direct effect of NWW accounting for mediation, shown in brackets.

∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

4.3. Results of additional analyses differentiating the separate NWW facets, NAWS and PAWS

We performed ten additional analyses, each estimating the same serial mediation model as our main analysis, but with a specific NWW facet as independent and NAWS or PAWS as dependent variable. To facilitate a continuous reading experience we only highlight the most salient results here, and refer to Table A6 in the appendix for details.

The first result that stands out is the negative direct relation between the facet time- and location-independent work and PAWS that seems to be offset by the total indirect effect, resulting in an insignificant total effect of this facet on PAWS. Second, also notable is that the facets management of output, access to colleagues, and access to information each have a significant negative direct relation with NAWS, indicating that higher levels of these facets relate to less feelings of negative well-being, regardless of the presence of the mediators.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key findings

This paper presents a first investigation into the relation between New Ways of Working (during the COVID-19 pandemic) and job-related affective well-being (JAWS), while accounting for the mediating effects of technostress, the need for recovery and work engagement. First, it shows that higher levels of NWW are associated with higher levels of total well-being (JAWS) and positive well-being (PAWS) and with less feelings of negative well-being (NAWS) (H1). Second, it shows that much of these relations are indirect, via the reduced technostress and need for recovery and the increased work engagement that are associated with higher levels of NWW (respectively H2 , H3 , H4). Third, additional analyses show that – after accounting for the effects of the mediators – higher levels of the NWW facets management of output, access to colleagues, and access to information are directly related to less feelings of NAWS, whereas higher levels of the facet time- and location-independent work are directly related to lower levels of PAWS. Lastly, the larger the change (compared to pre-COVID-19) in number of days per week that employees teleworked during the COVID-19 pandemic, the higher is their well-being.

5.2. Contributions to the literature

We investigate the relation between New Ways of Working and employee well-being (JAWS), a recognized research priority (López-Cabarcos et al., 2020; Kotera & Vione, 2020). In doing so, our study achieves its main objective, which is to expand the small but growing body of knowledge on employee outcomes of NWW (e.g. Gerards et al., 2018; Gerards et al., 2020; Gerards et al., 2021; Kotera & Vione, 2020; Peters et al., 2014). Furthermore, our study contributes to the literature on antecedents of employee well-being (e.g. Anderson et al., 2015; Charalampous et al., 2019; Mäkikangas et al., 2016; Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006; Wilks & Neto, 2013). Specifically, both these strands of literature are informed by our results that – overall – NWW are positively related to JAWS (H1) and that technostress, need for recovery and work engagement mediate the relation between NWW and JAWS (respectively H2 , H3 , H4). A more fine-grained contribution stems from this study's additional analyses, which show that the NWW facets management of output, access to colleagues, and access to information relate to less feelings of negative well-being, and that these relations are significant both directly and indirectly through reduced technostress, reduced need for recovery and increased work engagement.

Furthermore, because NWW incorporates teleworking, the abovementioned results are also relevant to the teleworking literature (e.g. Anderson et al., 2015; Boell et al., 2016; Taser et al., 2022). That is, this study's positive relation between NWW and JAWS (H1) concurs with the mostly positive findings in the literature regarding the effect of teleworking on well-being (Anderson et al., 2015; Charalampous et al., 2019; Ipsen et al., 2021). Moreover, the result that the NWW facet time-and location-independent work has a direct negative relation to feelings of positive well-being, is similar with teleworking literature that finds that ICT use (which is crucial for working time-and location-independent) can deteriorate the home-work boundary, and can increase fatigue and mental workload (e.g. Kotera & Vione, 2020; Rasmussen et al., 2020).

Interestingly, our results regarding the individual NWW facets’ relations to well-being contribute to unifying these paradoxical findings from the literature, by showing that there are aspects of NWW that negatively affect well-being (time- and location-independent work), but that there are more facets that positively affect well-being (management of output, access to colleagues, and access to information) and when analysed as a whole NWW relate positively to well-being.

A more fine-grained contribution to the teleworking literature is the result that the larger the changes in number of days teleworking due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the higher the well-being. Beyond the scope of this paper, but interesting for future research, is to investigate if this relation is subject to diminishing marginal returns or not. In other words, does adding two days of teleworking lead to twice the increase in well-being as compared to adding one day of teleworking, and does an increase in teleworking with one day lead to the same well-being increase for an employee that was used to zero days teleworking as compared to an employee that was used to three days teleworking?

Next, due to the inclusion of three mediators in our serial mediation model, this study also contributes to the respective literatures on antecedents and consequences of technostress, need for recovery and work engagement, with the novel findings that NWW reduces technostress and the need for recovery and the confirmation that NWW increases work engagement (Gerards et al., 2018). Furthermore, our study confirms that technostress increases the need for recovery (e.g. Barber & Santuzzi, 2014) and reduces work engagement. Our study also confirms the negative relation between the need for recovery and well-being (e.g. Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006).

Finally, our results contribute to the daily expanding literature on employee outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and more specifically to the strand of literature that investigates employee outcomes of COVID-19 induced teleworking (e.g. Molino et al., 2020; Oksanen et al., 2021; Parent-Lamarche, 2022; Parent-Lamarche & Boulet, 2021; Taser et al., 2022). Our contribution herein lies mainly in specifically linking NWW (which encompasses teleworking) during COVID-19 to a validated job-related well-being scale, while accounting for technostress, need for recovery, work engagement and the actual change in days teleworking.

5.3. Practical implications

Our finding that the NWW facets management of output, access to colleagues, and access to information directly relate to less feelings of negative well-being, even when accounting for the mediators, highlights that providing workers with autonomy and connectedness is important to enhance their well-being. However, the finding that – despite the overall positive relation of NWW to well-being – the facet time- and location-independent work directly and negatively relates to feelings of positive well-being, informs HR practitioners that implementation of NWW as a bundle of facets is not a set-and-forget strategy. The ensuing recommendation is that implementation of NWW or of (combinations of) NWW facets is supplemented with regular monitoring of employee well-being and the extent to which employees experience changes to their levels of technostress, need for recovery and work engagement. It is recommend that organizations do so by adding validated scales of these measures into existing employee satisfaction and well-being surveys or by establishing such surveys where they do not yet exist. This need to monitor employees’ well-being, technostress, need for recovery and work engagement becomes especially salient as more (large) organizations (e.g. PwC and Deloitte) announce that they will let their employees work virtually time- and location-independent in perpetuity,2 while evidence regarding long-run effects of such widespread and long-term application of NWW is virtually non-existent.

5.4. Limitations and further research

Although this study finds overall positive employee well-being effects of NWW, these findings are cross-sectional and therewith only inform the reader about short-run outcomes. Furthermore, cross-sectional studies can suffer from common method variance (CMV). However, statistical tests (see section 3.4) did not provide evidence of the presence of CMV. The cross-sectional nature of this study also warrants caution when making causal inferences. That said, the COVID-19 driven sudden and massive adoption of NWW practices is not something employees are likely to have foreseen, thus making the potential for reverse causality of employees with high well-being selecting into firms that offer NWW unlikely.

Future research can overcome the limitations of this study by creating longitudinal study designs to inform academics, practitioners and policymakers about the long-run employee well-being outcomes and mediating mechanisms associated with the widespread and long-term application of NWW.

6. Conclusions

The objective of this study has been to grow the budding body of knowledge regarding employee level outcomes of New Ways of Working. This objective was inspired by the limited extant knowledge of employee level outcomes of NWW, compounded by the COVID-19 driven proliferation of NWW practices. This proliferation of NWW practices suddenly provided many more workers with increased flexibility, autonomy and freedom regarding when, where, how, and how much to work, and also increased the reliance of many workers on intensive use of ICT. Specifically, applying Preacher and Hayes (2008) bootstrap method for serial mediation on a sample of the Dutch working population, this study sheds light on the question how NWW during COVID-19 affect employee well-being via technostress, need for recovery, and work engagement.

This study shows that higher levels of NWW during the pandemic relate to higher levels of total well-being (JAWS) and positive well-being (PAWS) and to less feelings of negative well-being (NAWS) (H1). This study also demonstrates that much of these relations are indirect, via the reduced technostress and need for recovery and the increased work engagement that are associated with higher levels of NWW (respectively H2 , H3 , H4). Moreover, the larger the change in number of days per week that employees teleworked during the COVID-19 pandemic (as compared to pre-COVID-19), the higher is their well-being.

In sum, the novel conclusion from this study is that – overall – NWW adoption during the COVID-19 pandemic relates positively to job-related employee well-being and that reduced technostress, reduced need for recovery and increased work engagement are important mechanisms in this relation. However, because contrary to the overall positive effect, the NWW facet time- and location-independent work negatively relates to well-being, NWW as a bundle of facets is not a set-and-forget strategy. This inspires the recommendation that implementation of NWW be supplemented with regular monitoring of employee well-being, technostress, need for recovery and work engagement.

Credit author statement

Rémi Andrulli, MSc; Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing. Dr. Ruud Gerards, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing, Supervision.

Acknowledgements

We thank Evert Webers and Lia Potma from Etil Research Group for their assistance in the survey design and data collection.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are strictly personal and do not represent the views of the European Parliament.

APPENDIX.

Table A1.

New Ways of Working scale

| Facet 1: time- and location-independent work |

| 1. I am able to set my own working hours |

| 2. I am able to determine where I work |

| 3. I am able to work from home if I want to |

| Facet 2: management of output |

| 4. I am able to determine the way I work |

| 5. My supervisor does not get involved with the way I do my job |

| 6. My supervisor evaluates me on the quality of the work I deliver, not the way I worked |

| Facet 3: access to organizational knowledge |

| 3a. Access to colleagues |

| 7. I am able to reach colleagues within the team quickly |

| 8. I am able to reach managers quickly |

| 9. I am able to reach colleagues outside the team quickly |

| 3b. Access to information |

| 10. I can access all necessary information on my computer, smartphone, and/or tablet |

| 11. I have access to all necessary information everywhere, at any time |

| Facet 4: flexibility in working relations |

| 12. I have the ability to adapt my working scheme to my phase of life and ambitions |

| 13. I have the possibility to work more or fewer hours |

| Facet 5: freely accessible open workplaces |

| 14. The building is arranged so that colleagues are easily accessible |

| 15. The building is arranged so that managers are easily accessible |

Note: Items in italics are not used in our analyses.

Table A2.

Results of factor analysis of all NWW items

| Factor |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NWW items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Facet 1: time- and location-independent work | |||||

| 1. I am able to set my own working hours | 0.5092 | ||||

| 2. I am able to determine where I work | 0.7608 | ||||

| 3. I am able to work from home if I want to | 0.7295 | ||||

| Facet 2: management of output | |||||

| 4. I am able to determine the way I work | 0.5019 | 0.4473 | |||

| 5. My supervisor does not get involved with the way I do my job | 0.8446 | ||||

| 6. My supervisor evaluates me on the quality of the work I deliver, not the way I worked | 0.7026 | ||||

| Facet 3: access to organizational knowledge | |||||

| 3a. Access to colleagues | |||||

| 7. I am able to reach colleagues within the team quickly | 0.8623 | ||||

| 8. I am able to reach managers quickly | 0.6179 | ||||

| 9. I am able to reach colleagues outside the team quickly | 0.7984 | ||||

| 3b. Access to information | |||||

| 10. I can access all necessary information on my computer, smartphone, and/or tablet | 0.8598 | ||||

| 11. I have access to all necessary information everywhere, at any time | 0.8572 | ||||

| Facet 4: flexibility in working relations | |||||

| 12. I have the ability to adapt my working scheme to my phase of life and ambitions | 0.3680 | 0.4665 | |||

| 13. I have the possibility to work more or fewer hours | 0.3970 | ||||

Note: Rotated results (oblique oblimin). Blanks represent loadings <0.35. Given our sample size of 170 observations, cross-loading in italics are ignored and not taken into account in constructing the facets.

Table A3.

Bootstrap results corresponding to Fig. 2. Serial mediation of the effect of NWW on total well-being via technostress, need for recovery and work engagement.

| 95% Conf. Interval |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Indirect effects: | |||||

| 1. | NWW - > TS - > JAWS total | 0.027 | 0.019 | −0.004 | 0.071 |

| 2. | NWW - > NFR - > JAWS total | 0.067 | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.124 |

| 3. | NWW - > UWES - > JAWS total | 0.248 | 0.061 | 0.130 | 0.367 |

| 4. | NWW - > TS - > NFR - > JAWS total | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.038 |

| 5. | NWW - > TS - > UWES - > JAWS total | −0.014 | 0.013 | −0.042 | 0.010 |

| 6. | NWW - > NFR - > UWES - > JAWS total | 0.039 | 0.020 | 0.008 | 0.084 |

| 7. | NWW - > TS - > NFR - > UWES - > JAWS total | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.023 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.392 | 0.069 | 0.258 | 0.525 | |

Note: 5000 bootstrap samples.

Table A4.

Bootstrap results corresponding to Fig. 3. Serial mediation of the effect of NWW on positive affective well-being via technostress, need for recovery and work engagement.

| 95% Conf. Interval |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | Lower | Upper | |||

| Indirect effects: | ||||||

| 1. | NWW - > TS - > JAWS-POS | −0.007 | 0.013 | −0.039 | 0.015 | |

| 2. | NWW - > NFR - > JAWS-POS | 0.037 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.080 | |

| 3. | NWW - > UWES - > JAWS-POS | 0.335 | 0.077 | 0.179 | 0.485 | |

| 4. | NWW - > TS - > NFR - > JAWS-POS | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.023 | |

| 5. | NWW - > TS - > UWES - > JAWS-POS | −0.019 | 0.017 | −0.056 | 0.013 | |

| 6. | NWW - > NFR - > UWES - > JAWS-POS | 0.052 | 0.025 | 0.011 | 0.108 | |

| 7. | NWW - > TS - > NFR - > UWES - > JAWS-POS | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.030 | |

| Total indirect effect | 0.419 | 0.079 | 0.263 | 0.575 | ||

Note: 5000 bootstrap samples.

Table A5.

Bootstrap results corresponding to Fig. 4. Serial mediation of the effect of NWW on negative affective well-being via technostress, need for recovery and work engagement.

| 95% Conf. Interval |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Indirect effects: | |||||

| 1. | NWW - > TS - > JAWS-NEG | −0.058 | 0.031 | −0.128 | −0.008 |

| 2. | NWW - > NFR - > JAWS-NEG | −0.087 | 0.033 | −0.156 | −0.030 |

| 3. | NWW - > UWES - > JAWS-NEG | −0.091 | 0.034 | −0.165 | −0.032 |

| 4. | NWW - > TS - > NFR - > JAWS-NEG | −0.020 | 0.012 | −0.048 | −0.003 |

| 5. | NWW - > TS - > UWES - > JAWS-NEG | 0.005 | 0.005 | −0.003 | 0.019 |

| 6. | NWW - > NFR - > UWES - > JAWS-NEG | −0.014 | 0.009 | −0.037 | −0.002 |

| 7. | NWW - > TS - > NFR - > UWES - > JAWS-NEG | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.010 | 0.000 |

| Total indirect effect | −0.268 | 0.055 | −0.377 | −0.165 | |

Note: 5000 bootstrap samples.

Table A6.

Serial mediation models of NWW Facets on Positive and Negative Affective Well-being.

| N = 170 | Positive Affective Well-being (PAWS) |

Negative Affective Well-being (NAWS) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

| NWW F1 Time & loc. Indep. Work | NWW F2 Management of output | NWW F3a Access to colleagues | NWW F3b Access to information | NWW F4 Flex. Working relations | NWW F1 Time & loc. Indep. Work | NWW F2 Management of output | NWW F3a Access to colleagues | NWW F3b Access to information | NWW F4 Flex. Working relations | |

| NWW Facet's total effect (c) | .12 | .32∗∗∗ | .32∗∗∗ | .24∗∗ | .29∗∗ | −.06 | −.40∗∗∗ | −.42∗∗∗ | −.33∗∗∗ | −.31∗∗∗ |

| NWW Facet's direct effect (c′) | −.11∗ | −.04 | .03 | −.02 | −.02 | .12 | −.20∗∗ | −.24∗∗∗ | −.16∗ | −.09 |

| Technostress (TS) | .03 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .03 | .27∗∗∗ | .24∗∗∗ | .24∗∗∗ | .25∗∗∗ | .25∗∗∗ |

| Need for Recovery (NFR) | −.12∗∗ | −.12∗∗ | −.11∗ | −.12∗∗ | −.12∗∗ | .32∗∗∗ | .30∗∗∗ | .28∗∗∗ | .30∗∗∗ | .30∗∗∗ |

| Work Engagement (UWES) | .82∗∗∗ | .82∗∗∗ | .80∗∗∗ | .81∗∗∗ | .81∗∗∗ | −.28∗∗∗ | −.21∗∗ | −.20∗∗ | −.24∗∗∗ | −.25∗∗∗ |

| Change in No. Of days p/w telework | .07∗∗ | .05∗ | .04∗ | .05∗ | .05∗ | −.14∗∗∗ | −.08∗ | −.08∗∗ | −.08∗ | −.09∗∗ |

| Age | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | −.02∗∗ | −.02∗∗ | −.03∗∗∗ | −.02∗∗ | −.02∗∗ |

| R-squared of serial mediation model | .76 | .75 | .75 | .75 | .75 | .46 | .48 | .50 | .48 | .46 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||||

| Total indirect effect | .23^ | .35^ | .29^ | .26^ | .31^ | −.18^ | −.21^ | −.18^ | −.17^ | −.22^ |

| 1. NWW→TS→PAWS/NAWS | −.00 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.03 | −.04^ | −.04 | −.04 | −.05^ |

| 2. NWW→NFR→PAWS/NAWS | .02 | .02^ | .03^ | .02^ | .03^ | −.06 | −.06^ | −.06^ | −.06^ | −.06^ |

| 3. NWW→UWES→PAWS/NAWS | .16 | .29^ | .23^ | .19^ | .24^ | −.05 | −.07^ | −.06^ | −.06^ | −.07^ |

| 4. NWW→TS→NFR→PAWS/NAWS | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01^ | −.01 | −.02^ | −.01 | −.01 | −.02^ |

| 5. NWW→TS→UWES→PAWS/NAWS | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.02 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 |

| 6. NWW→NFR→UWES→PAWS/NAWS | .04 | .04^ | .04^ | .04^ | .04^ | −.02 | −.01^ | −.01^ | −.01^ | −.01^ |

| 7. NWW→TS→NFR→UWES→PAWS/NAWS | .01 | .01^ | .01 | .01 | .01^ | −.00 | −.00 | −.00 | −.00 | −.00 |

Notes: c = total effect. C′ = direct effect of NWW accounting for mediation. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05. ^ is used to denote a significant indirect effect (the value ‘0’ is not observed between the bootstrap lower limit and upper limit confidence interval). Control variables for gender, managing position and high education were not significant in any of the models and omitted from the table.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Adil A., Kamal A. Impact of psychological capital and authentic leadership on work engagement and job related affective well-being. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 2016;31(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A.J., Kaplan S.A., Vega R.P. The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology. 2015;24(6):882–897. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari R., Grover V., Purvis R. Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. MIS Quarterly. 2011;35:831–858. [Google Scholar]

- Baane R., Houtkamp P., Knotter M. Koninklijke Van Gorcum; Assen: 2010. Het Nieuwe Werken ontrafeld – over Bricks, Bytes en Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Barber L.K., Santuzzi A.M. Please respond ASAP: Workplace telepressure and employee recovery. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2014;20(2):172–189. doi: 10.1037/a0038278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barley S.R., Meyerson D.E., Grodal S. E-Mail as a source and symbol of stress. Organization Science. 2011;22(4):887–906. [Google Scholar]

- Boell S.K., Cecez-Kecmanovic D., Campbell J. Telework paradoxes and practices: The importance of the nature of work. New Technology, Work and Employment. 2016;31(2):114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Brod C. Addison-Wesley; Reading, Mass: 1984. Technostress: The human Cost of the computer revolution. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson E., Horton J.J., Ozimek A., Rock D., Sharma G., TuYe H.Y. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data. NBER Working Paper No. 27344. [Google Scholar]

- Budnick C.J., Rogers A.P., Barber L.K. The fear of missing out at work: Examining costs and benefits to employee health and motivation. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;104 [Google Scholar]

- Charalampous M., Grant C.A., Tramontano C., Michailidis E. Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology. 2019;28(1):51–73. [Google Scholar]

- De Leede J. Emerald Group Publishing; Bingley: 2016. New ways of working practices: Antecedents and outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C.M., Simmering M.J., Atinc G., Atinc Y., Babin B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69(8):3192–3198. [Google Scholar]

- Gerards R., De Grip A., Baudewijns C. Do new ways of working increase work engagement? Personnel Review. 2018;47(2):517–534. [Google Scholar]

- Gerards R., De Grip A., Weustink A. Do New Ways of Working increase informal learning at work? Personnel Review. 2020;50(4):1200–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Gerards R., Van Wetten S., Van Sambeek S. New ways of working and intrapreneurial behaviour: The mediating role of transformational leadership and social interaction. Review of Managerial Science. 2021;15(4):2075–2110. [Google Scholar]

- Halford S. Hybrid workspace: Re‐spatialisations of work, organisation and management. New Technology, Work and Employment. 2005;20(1):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. A regression-based approach. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; New York: 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Holgado-Tello F.P., Chacón-Moscoso S., Barbero-García I., Vila-Abad E. Polychoric versus Pearson correlations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables. Quality and Quantity. 2010;44(1):153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Howard M.C. A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: What we are doing and how can we improve? International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. 2016;32(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I., Cha O. Examining technostress creators and role stress as potential threats to employees' information security compliance. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;81:282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsen C., van Veldhoven M., Kirchner K., Hansen J.P. Six key advantages and disadvantages of working from home in Europe during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1826. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen N., Kant I., van den Brandt P. Need for recovery in the working population: Description and associations with fatigue and psychological distress. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;9(4):322–340. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0904_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotera Y., Vione K.C. Psychological impacts of the new ways of working (NWW): A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(14):5080. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-K., Chang C.-T., Lin Y., Cheng Z.-H. The dark side of smartphone usage: Psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:373–383. 0. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cabarcos M.Á., López-Carballeira A., Ferro-Soto C. New ways of working and public healthcare professionals' well-being: The response to face the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2020;12(19):8087. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkikangas A., Kinnunen U., Feldt T., Schaufeli W. The longitudinal development of employee well-being: A systematic review. Work & Stress. 2016;30(1):46–70. [Google Scholar]

- Molino M., Ingusci E., Signore F., Manuti A., Giancaspro M.L., Russo V., Cortese C.G. Wellbeing costs of technology use during Covid-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability. 2020;12(15):5911. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen A., Oksa R., Savela N., Mantere E., Savolainen I., Kaakinen M. COVID-19 crisis and digital stressors at work: A longitudinal study on the Finnish working population. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021;122 doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Lamarche A. Teleworking, work engagement, and intention to quit during the COVID-19 pandemic: Same storm, different boats? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(3):1267. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Lamarche A., Boulet M. Employee well-being in the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of teleworking during the first lockdown in the province of Quebec, Canada. Work. 2021;70(3):763–775. doi: 10.3233/WOR-205311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters P., Poutsma E., Van der Heijden B.I., Bakker A.B., Bruijn T.D. Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM-process approach to study flow. Human Resource Management. 2014;53(2):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragu-Nathan T.S., Tarafdar M., Ragu-Nathan B.S., Tu Q. The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Information Systems Research. 2008;19(4):417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen E.E., Punyanunt-Carter N., LaFreniere J.R., Norman M.S., Kimball T.G. The serially mediated relationship between emerging adults' social media use and mental well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;102:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke K., Chamorro-Premuzic T. When email use gets out of control: Understanding the relationship between personality and email overload and their impact on burnout and work engagement. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;36:502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard N.P. Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2001;46(4):655–684. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Bakker A.B., Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2006;66(4):701–716. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Salanova M., Gonzalez-Roma V., Bakker A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2002;3(1):71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., van Rhenen W. Over de rol van positieve en negatieve emoties bij het welbevinden van managers: Een studie met de Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS) Gedrag en Organisatie. 2006;19(4):323–344. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(3):518. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag S., Zijlstra F.R. Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(2):330. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarafdar M., Tu Q., Ragu-Nathan B.S., Ragu-Nathan T.S. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2007;24(1):301–328. [Google Scholar]

- Taser D., Aydin E., Torgaloz A.O., Rofcanin Y. An examination of remote e-working and flow experience: The role of technostress and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior. 2022;127 [Google Scholar]

- Ting D.S.W., Carin L., Dzau V., Wong T.Y. Digital technology and COVID-19. Nature Medicine. 2020;26:458–464. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0824-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Katwyk P.T., Fox S., Spector P.E., Kelloway E.K. Using the job-related affective well-being scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5(2):219–230. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veldhoven M.J.P.M., Broersen S. Measurement quality and validity of the “need for recovery scale”. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;60(suppl 1):i3–i9. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Shu Q., Qiang T. Technostress under different organizational environments: An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008;24:3002–3013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Tan S.C., Li L. Technostress in university students' technology-enhanced learning: An investigation from multidimensional person-environment misfit. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;105:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilks D.W., Neto F. Workplace well-being, gender and age: Examining the ‘double jeopardy’ effect. Social Indicators Research. 2013;114:875–890. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.