Abstract

Background:

Hispanic/Latinx (HL) ethnicity encompasses racially and culturally diverse subgroups. Studies suggest that Puerto Ricans (PR) may bear greater asthma-related morbidity than Mexicans, but these were conducted in children or had limited clinical characterization.

Objective:

To determine whether disparities in asthma morbidity exist among HL adult subgroups

Methods:

Adults with moderate-severe asthma were recruited from US clinics, including Puerto Rico, for the PREPARE trial. Considering the shared heritage between PR and other Caribbean HL (Cubans and Dominicans, C&D), we compared baseline self-reported clinical characteristics between Caribbean HL (PR and C&D: CHL; n=457) and other HLs (Mexicans, Spaniards, Central/South Americans, OHL; n=141), and between CHL subgroups [C&D (n=56) and PR (n=401)]. We compared asthma morbidity measures (self-reported exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids, ER/Urgent care (ER/UC) visits, hospitalizations, healthcare utilization) through negative binomial regression.

Results:

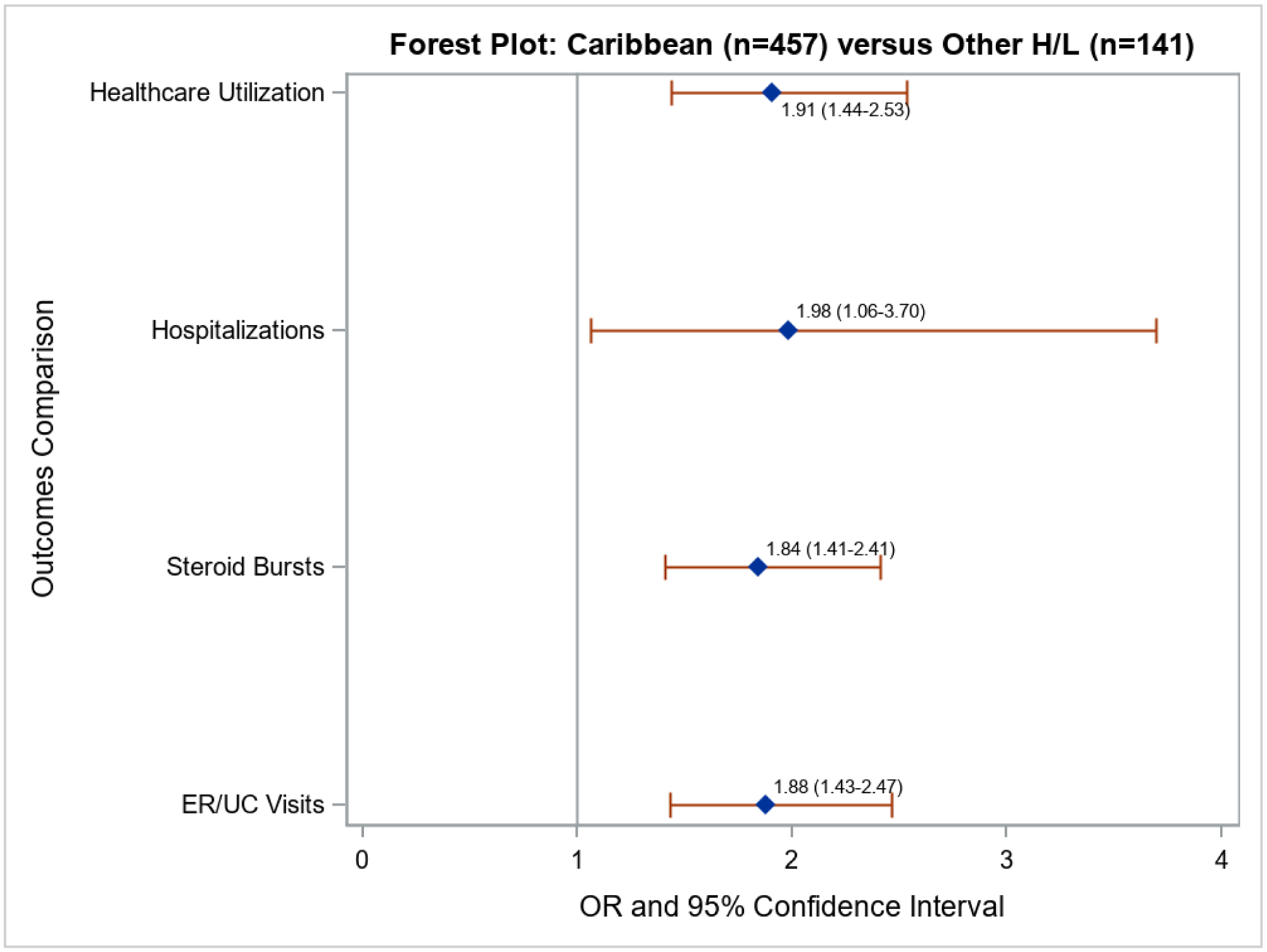

CHL compared to OHL were similar in age, BMI, poverty status, blood eosinophils and FeNO but were prescribed more asthma controller therapies. Relative to OHL, CHL had significantly increased odds of asthma exacerbations (OR=1.84, 95%CI=1.4–2.4), ER/UC visits (OR=1.88, 95%CI=1.4–2.5), hospitalization (OR=1.98, 95%CI=1.06–3.7), and healthcare utilization (OR=1.91, 95%CI=1.44–2.53). Of the CHL subgroups, PR had significantly increased odds of asthma exacerbations, ER/UC visits, hospitalizations, and healthcare utilization compared to OHL, whereas C&D only had increased odds of exacerbations compared to OHL. PR compared to C&D had greater odds of ER/UC and healthcare utilization.

Conclusion:

CHL adults reported nearly twice the asthma morbidity compared to OHL; these differences are primarily driven by PR. Novel interventions are needed to reduce morbidity in this highly impacted population.

Clinical Implications

Despite a shared heritage with Cubans and Dominicans, Puerto Ricans have greater odds of ER/UC visits relative to Cubans and Dominicans; culture and healthcare access may underlie these differences.

Capsule summary:

Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx adults with moderate-severe asthma exhibit greater asthma morbidity than adults in other Hispanic/Latinx subgroups independently of self-reported race. Within the Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx subgroup Puerto Rican adults have greater healthcare utilization for asthma.

Keywords: Healthcare disparities, severe persistent asthma, healthcare utilization, asthma exacerbations, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans, minority health, ER visits, hospitalizations

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic airway disease that affects nearly 8.4% of the US population(1) with healthcare burdens and economic costs projected to exceed $963 billion over the next 20 years(2). Hispanic/Latinx (HL) ethnicity is a conglomerate of racially and culturally diverse subgroups with a shared language(3). There is marked variability in asthma prevalence among HL subgroups(4), and particularly, studies suggest that Puerto Ricans have greater asthma prevalence relative to Caucasians and Mexicans (5, 6). Multiple reasons have been posited to underlie this healthcare disparity, including different physiologic features and genetic, epigenetic, and environmental exposures(7). For example, Puerto Ricans exhibit less bronchodilator responsiveness(8) and experience more early-life respiratory viral infections than their Mexican counterparts(9). Further, asthma among Puerto Ricans correlates with secondhand smoke exposure, obesity, atopy, pollution, psychosocial risk factors, and exposure to violence, and is often reflected by epigenetic signatures associated with both anxiety and with reduced beta-2 adrenergic and corticosteroid receptor expression(7, 10–15). Importantly, greater proportions of African genetic ancestry among HL are associated with poorer lung function and higher susceptibility to asthma(16). The greater abundance of African ancestral genetics among Puerto Ricans relative to other HL has also been proposed to account for disparities in asthma prevalence and its related morbidity (17). However, most of these studies were conducted in children, focused on asthma prevalence and not asthma morbidity measures (e.g., asthma exacerbations), and did not control for possible socioeconomic confounders such as income or poverty, or investigated differences in clinical features such as asthma severity, asthma controller therapy regimens, peripheral blood eosinophils, or FeNO. Additionally, little is known about asthma-related morbidity among other Caribbean HL (i.e., Cubans and Dominicans) that share a similar racial ancestry to that of Puerto Ricans(18, 19). Finally, few studies have compared asthma-morbidity measures between Puerto Ricans living in the US mainland and those living in Puerto Rico.

We set out to determine whether adult HL subgroups with moderate-severe persistent asthma exhibit different clinical and phenotypic features and disparities in asthma-related morbidity. Considering a shared heritage between Puerto Ricans and Cubans and Dominicans, we hypothesized that Caribbean HL (combined Puerto Ricans and Cubans and Dominicans) adults exhibit greater asthma morbidity compared to other HLs (OHL) (Mexicans, Spaniards, Central and South Americans).

Methods

Adults with moderate-severe persistent asthma were recruited from primary care and specialty clinics across the United States, including Puerto Rico, for the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)-sponsored PeRson EmPowered Asthma RElief (PREPARE) trial. The PREPARE trial is an open-label, pragmatic trial in African American/ and Hispanic Latinx participants that compares usual care to a reliever-triggered inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) strategy called PARTICS (Patient-Activated Reliever-Triggered Inhaled CorticoSteroid). Full details on trial design and methods are published(20). This analysis included 598 HL participants randomized for PREPARE. We examined differences in self-reported baseline clinical and phenotypic characteristics and asthma morbidity measures between HL subgroups: Caribbean HL, OHL, Caribbean HL subgroups (Cubans and Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans) and Puerto Ricans residing in the US mainland or Puerto Rico. Identification with a specific HL subgroup was self-reported. Race was recorded independently of ethnicity and was also self-reported. Number of medical comorbid conditions were recorded; these included heart disease, cancer [excluding non-melanoma skin], stroke, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, COPD, HIV/AIDS, depression, and/or sleep disorders. Participant incomes were recorded as $10,000/year incremental categories, from “less than $10,000/year” to “more than $75,000/year”. We used income and household size in reference to the federal poverty income guidelines to determine poverty status(21). Federal poverty guidelines were established for the 48 contiguous states but normally applied to Puerto Rico(22). Perceived stress was determined using the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale(23). Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 depression screen(24). Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was captured at enrollment using NIOX® devices kindly contributed by Circassia Limited (Morrisville, NC). Peripheral blood eosinophils were either determined at baseline among participants who consented to a blood draw or were assigned a historical value of up to a year prior to enrollment among those who refused blood draws.

We considered self-reported asthma exacerbations in the year prior to enrollment and asthma control survey scores as measures of asthma morbidity. Asthma exacerbations were categorized as outpatient systemic corticosteroid bursts, emergency room (ER) and urgent care (UC) visits, or hospitalizations. We defined ‘healthcare utilization’ as either an ER/UC visit or a hospitalization for asthma(25). We determined baseline asthma control and disease burden based on the Asthma Control Test (ACT®)(26), Asthma Symptom Utility Index (ASUI)(27), and asthma Activities, Persistent triGgers, Asthma medications and Response to therapy (APGAR)(28) surveys.

Statistical analysis

Clinical and phenotypic characteristics were compared between Caribbean HL and OHL and all other subgroups through Chi-square or student’s t-tests. Linear regression was used for all three asthma control surveys. Differences in asthma morbidity measures such as self-reported exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids, ER/UC visits, hospitalizations, and health care utilization (defined as combined ER/UC plus hospitalization) were tested using negative binomial regression. All models were adjusted for variables found to be statistically significantly different between all HL subgroup comparisons at p<0.10, and were built a priori to include adjustment for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and annual household income regardless of statistical significance. All final models were thus adjusted for age, sex, BMI, annual household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression.

Results

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 598 self-identified HL participants in the PREPARE trial. Of the 598 HL participants, 141 self-identified as OHL (Mexicans, Spaniards, Central and South Americans) and 457 were self-identified Caribbean HL (Puerto Ricans, and Cubans and Dominicans). Of the Caribbean HL, 401 identified as Puerto Rican and 56 identified as Cuban and Dominicans (Table 2). Compared with OHL, Caribbean HL were more likely to: be female, prefer Spanish as spoken language, have lower household incomes, be prescribed more asthma controller therapies, have one or more medical comorbidities, not be employed, be a current or former smoker, and be depressed.

Table 1.

Demographics for Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx compared to Other Hispanic/Latinx*

| Overall n=598 |

Hispanic Ethnicity | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean H/L n=457 |

Other H/L n=141 |

|||

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.7 (14.0) | 48.2 (13.7) | 46.3 (15.0) | 0.167 |

|

Gender, n (%) Female Male |

497 (83.1) 101 (16.9) |

388 (84.9) 69 (15.1) |

109 (77.3) 32 (22.7) |

0.035 |

|

Language, n (%) English Spanish |

331 (55.4) 267 (44.6) |

237 (51.9) 220 (48.1) |

94 (66.7) 47 (33.3) |

0.002 |

|

Income, n (%) Low income ($20,000 or less) Not low income Income not disclosed |

260 (43.5) 226 (37.8) 112 (18.7) |

206 (45.1) 159 (34.8) 92 (20.1) |

54 (38.3) 67 (47.5) 20 (14.2) |

0.024 |

|

Poverty status, n (%) Above federal poverty line Below federal poverty line Income not disclosed |

217 (36.3) 269 (45.0) 112 (18.7) |

156 (34.1) 209 (45.7) 92 (20.1) |

61 (43.3) 60 (42.6) 20 (14.2) |

0.141 |

|

Education level, n (%) High school diploma or higher No high school diploma |

491 (82.1) 107 (17.9) |

381 (83.4) 76 (16.6) |

110 (78.0) 31 (22.0) |

0.147 |

|

Employment status, n (%) Employed Unemployed, disabled, retired, other, prefer not to answer |

220 (36.8) 378 (63.2) |

156 (34.1) 301 (65.9) |

64 (45.4) 77 (54.6) |

0.015 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 33.1 (8.1) | 33.4 (8.4) | 32.3 (6.9) | 0.172 |

|

Comorbidity count, n (%) 0 1 2 3 4+ |

206 (34.4) 128 (21.4) 97 (16.2) 92 (15.4) 75 (12.5) |

142 (31.1) 94 (20.6) 76 (16.6) 81 (17.7) 64 (14.0) |

64 (45.4) 34 (24.1) 21 (14.9) 11 (7.8) 11 (7.8) |

0.002 |

| Asthma Control Test score, mean (SD) | 14.3 (4.5) | 14.1 (4.5) | 14.6 (4.4) | 0.242 |

| Asthma Symptom Utility Index score, mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.108 |

| Asthma APGAR score, mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.3 (1.7) | 0.140 |

|

Depression: PHQ-2, n (%) Depressed Not depressed |

195 (32.6) 403 (67.4) |

162 (35.4) 295 (64.6) |

33 (23.4) 108 (76.6) |

0.008 |

|

Health Literacy: BHLS, n (%) High Low |

461 (77.1) 137 (22.9) |

348 (76.1) 109 (23.9) |

113 (80.1) 28 (19.9) |

0.324 |

| Everyday Discrimination Scale score, mean (SD) | 8.6 (4.5) | 8.6 (4.6) | 8.7 (4.1) | 0.717 |

| Perceived Stress Scale score, mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.3) | 5.9 (3.4) | 5.5 (3.0) | 0.187 |

|

Baseline controller medication ICS only ICS plus 1 other controller therapy ICS plus 2+ controller therapies No ICS reported Regimen includes biologic |

103 (17.2) 211 (35.3) 258 (43.1) 1 (0.2) 25 (4.2) |

59 (12.9) 151 (33.0) 227 (49.7) 0 (0) 20 (4.4) |

44 (31.2) 60 (42.6) 31 (22.0) 1 (0.7) 5 (3.5) |

<0.0001 |

| FeNO (ppb), mean (SD) | n=506 28.0 (29.2) |

n=395 27.1 (28.9) |

n=111 31.2 (30.2) |

0.195 |

| Absolute eosinophil count (cells/mcL), mean (SD) | n=523 269.5 (278.4) |

n=407 263.6 (241.5) |

n=116 290.2 (381.3) |

0.365 |

|

Smoking status Current smoker Former smoker Non-smoker |

34 (5.7) 149 (24.9) 415 (69.4) |

33 (7.2) 125 (27.4) 299 (65.4) |

1 (0.7) 24 (17.0) 116 (82.3) |

0.0002 |

|

Smoking environment No Yes |

483 (80.8) 115 (19.2) |

369 (80.7) 88 (19.3) |

114 (80.9) 27 (19.1) |

0.978 |

Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx: Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans; Other Hispanic/Latinx: Mexicans, Central and South Americans, and Spaniards; APGAR: Activities, Persistent, triGGers, Asthma medications, Response to therapy; BHLS: Brief Health Literacy Scale; BMI: body mass index; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; H/L: Hispanic/Latinx; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; PHQ-2: Patient Health Questionnaire-2; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2.

Demographics in Cubans and Dominicans compared to Puerto Ricans

| Cubans and Dominicans n=56 |

Puerto Ricans n=401 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 45.9 (16.4) | 48.5 (13.3) | 0.267 |

|

Gender, n (%)

Female Male |

46 (82.1) 10 (17.9) |

342 (85.3) 59 (14.7) |

0.538 |

|

Language, n (%) English Spanish |

28 (50.0) 28 (50.0) |

209 (52.1) 192 (47.9) |

0.766 |

|

Income, n (%) Low income ($20,000 or less) Not low income Income not disclosed |

17 (30.4) 22 (39.3) 17 (30.4) |

189 (47.1) 137 (34.2) 75 (18.7) |

0.087 |

|

Poverty status, n (%) Above federal poverty line Below federal poverty line Income not disclosed |

17 (30.4) 22 (39.3) 17 (30.4) |

139 (34.7) 187 (46.6) 75 (18.7) |

0.910 |

|

Education level, n (%) High school diploma or higher No high school diploma |

42 (75.0) 14 (25.0) |

339 (84.5) 62 (15.5) |

0.073 |

|

Employment status, n (%) Employed Unemployed, disabled, retired, other, prefer not to answer |

24 (42.9) 32 (57.1) |

132 (32.9) 269 (67.1) |

0.142 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 31.1 (7.7) | 33.7 (8.5) | 0.032 |

|

Comorbidity count, n (%) 0 1 2 3 4+ |

26 (46.4) 11 (19.6) 7 (12.5) 6 (10.7) 6 (10.7) |

116 (28.9) 83 (20.7) 69 (17.2) 75 (18.7) 58 (14.5) |

0.100 |

|

Depression: PHQ-2, n (%) Depressed Not depressed |

18 (32.1) 38 (67.9) |

144 (35.9) 257 (64.1) |

0.581 |

|

Health Literacy: BHLS, n (%) High Low |

41 (73.2) 15 (26.8) |

307 (76.6) 94 (23.4) |

0.582 |

| Everyday Discrimination Scale score, mean (SD) | 8.7 (4.7) | 8.6 (4.6) | 0.807 |

| Perceived Stress Scale score, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.9) | 5.8 (3.4) | 0.088 |

|

Baseline controller medication ICS only ICS plus 1 other controller therapy ICS plus 2+ controller therapies No ICS reported Regimen includes biologic |

9 (16.1) 21 (37.5) 25 (44.6) 0 (0) 1 (1.8) |

50 (12.5) 130 (32.4) 202 (50.4) 0 (0) 19 (4.7) |

0.536 |

| FeNO (ppb), mean (SD) | n=46 40.4 (54.7) |

n=349 25.4 (23.0) |

0.071 |

| Absolute eosinophil count (cells/mcL), mean (SD) | n=42 293.0 (280.1) |

n=365 260.3 (236.9) |

0.407 |

|

Smoking status Current smoker Former smoker Non-smoker |

1 (1.8) 13 (23.2) 42 (75.0) |

32 (8.0) 112 (27.9) 257 (64.1) |

0.142 |

|

Smoking environment No Yes |

48 (85.7) 8 (14.3) |

114 (80.9) 27 (19.1) |

0.314 |

BHLS: Brief Health Literacy Scale; BMI: body mass index; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; H/L: Hispanic/Latinx; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; PHQ-2: Patient Health Questionnaire-2; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 1 shows the results of the multivariable analysis of asthma morbidity measures, which was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression. Compared with OHL, Caribbean HL had increased odds of corticosteroid bursts for asthma exacerbations (OR=1.84, 95% CI=1.41–2.41), ER/UC visits for asthma (OR=1.88, 95% CI=1.43–2.47), hospitalizations (OR=1.98, 95% CI=1.06–3.70) and healthcare utilization (OR=1.91, 95% CI=1.44–2.53). Results were robust to adjustment by FeNO and blood eosinophils which were available in a subset of participants. There were no significant differences in the proportion of subjects with uncontrolled asthma (based on ACT, ASUI and asthma APGAR scores) between Caribbean HL and OHL (Table 3).

Figure 1:

Forest plot comparing Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx (Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans) vs. Other Hispanic/Latinx (Mexicans, Central and South Americans, and Spaniards) using negative binomial regression and controlling for age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression. Values to the right of the vertical line mean greater odds of outcomes for Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx.

Table 3.

ACT, ASUI and Asthma APGAR in Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx compared to other Hispanic/Latinx*

| Overall n=598 |

Hispanic Ethnicity | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean H/L n=457 |

Other H/L n=141 |

|||

| Asthma Control Test score, mean (SD) | 14.3 (4.5) | 14.1 (4.5) | 14.6 (4.4) | 0.242 |

| Asthma Symptom Utility Index score, mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.108 |

| Asthma APGAR score, mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.3 (1.7) | 0.140 |

Caribbean Hispanic/Latinx: Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans; Other Hispanic/Latinx: Mexicans, Central and South Americans, and Spaniards; APGAR: Activities, Persistent, triGGers, Asthma medications, Response to therapy; H/L: Hispanic/Latinx; SD: standard deviation.

We then compared baseline demographics and clinical features between Caribbean HL subgroups (Puerto Ricans and Cubans & Dominicans) and OHL. Puerto Ricans, compared to OHL, were more likely to: be female, prefer Spanish as spoken language, have lower household incomes, not be employed, have more medical comorbidities, be prescribed more controller therapies, be current or former smokers, and be depressed (Supplementary tables 1 and 2). Figure 2 shows the results of the multivariable analysis comparing Puerto Ricans vs. OHL on asthma morbidity after adjustment for the above differences and a priori adjustments defined in the methods section. Compared with OHL, Puerto Ricans (n=401) had increased odds of corticosteroid bursts (OR=1.89, 95% CI=1.44–2.49), ER/UC visits (OR=2.01, 95% CI=2.53–2.66), hospitalizations (OR=2.04, 95% CI=1.53–2.71) and healthcare utilization (OR=2.04, 95% CI=1.53–2.71).

Figure 2:

Forest plot comparing Puerto Ricans vs. Other Hispanic/Latinx (Mexicans, Central and South Americans, and Spaniards) using negative binomial regression controlling for age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression. Values to the right of the vertical line mean greater odds of outcomes for Puerto Ricans.

Cubans and Dominicans, compared to OHL, were more likely to prefer Spanish as spoken language, be prescribed more controller therapies, and have higher perceived stress (Supplementary tables 3 and 4). Multivariate analysis, after adjustment for the same covariates noted above for Caribbean HL vs. OHL, shows that Cubans & Dominicans (n=56) compared to OHL had increased odds of corticosteroid bursts (OR=1.64, 95% CI=1.12–2.4), but no significant differences were found in other morbidity measures such as ER/UC visits, hospitalizations, or healthcare utilization after adjustment for the above differences and a priori adjustments defined in the methods section (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Cubans and Dominicans vs. Other Hispanic/Latinx (Mexicans, Central and South Americans, and Spaniards) using negative binomial regression controlling for age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression. Values to the right of the vertical line mean greater odds of outcomes for Cubans and Dominicans.

We then compared baseline demographics and clinical features between Caribbean HL subgroups (Puerto Ricans and Cubans & Dominicans). Puerto Ricans compared to Cubans and Dominicans were more likely to have higher BMIs (Table 2 and Supplementary table 5). In multivariate analysis, compared with Cubans & Dominicans, Puerto Ricans had increased odds of ER/UC visits (OR=1.55, 95% CI=1.10–2.20, p=0.02) and healthcare utilization (OR=1.47, 95% CI=1.02–2.12) after adjustment for the above differences and a priori adjustments defined in the methods section (Figure 4). There were no significant differences in corticosteroid bursts or hospitalizations.

Figure 4:

Puerto Ricans vs. Cubans and Dominicans using negative binomial regression controlling for age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression. Values to the right of the vertical line mean greater odds of outcomes for Puerto Ricans.

Additional comparisons were made between Puerto Ricans residing in the US mainland (n=300) and those residing in the island (n=101), which showed mainland Puerto Ricans were more likely to: have English as primary spoken language, have lower education level attained, not be employed, have more medical comorbidities, have higher BMI, have lower health literacy, be current or former smokers, have higher perceived stress, have lower FeNO and lower peripheral blood eosinophils (Supplementary Table 6). Puerto Ricans residing in the US mainland were more likely to have worse asthma control (lower ACT scores) and worse preference-based quality of life (lower ASUI scores) (Supplementary table 7). Despite these differences, there were no significant differences in any asthma morbidity measure between mainland and island Puerto Ricans in multivariable analysis after adjustment for the above differences and a priori adjustments defined in the methods section (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

Mainland Puerto Ricans vs. island Puerto Ricans using negative binomial regression controlling for age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, and depression. Values to the right of the vertical line mean greater odds of outcomes for mainland Puerto Ricans.

Lastly, since Caribbean HL have a greater abundance of African ancestral genetics relative to other HL, we sought to determine whether self-reported race also associated with worse asthma morbidity. We compared self-identified Black HL (n=146) vs. non-Black HL (n=462). Black HL were more likely: to be younger, have higher educational attainment levels, be current smokers, and experience increased perceived discrimination (Supplementary tables 8 and 9). However, multivariate analysis showed no significant differences between these two groups in terms of corticosteroid bursts, ER/UC visits, hospitalizations, and healthcare utilization for asthma after adjustment for the above differences and a priori adjustments defined in the methods section (Supplementary figure 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare clinical and phenotypic features (FeNO, peripheral blood eosinophils) and several measures of asthma morbidity in adults across HL subgroups with moderate to severe persistent asthma. We report several novel findings including first, that Caribbean HL adults experience greater asthma morbidity than OHL; second, that Puerto Ricans bear a greater share of this burden relative to other Caribbean HL adults, particularly for ER/UC visits and healthcare utilization; and third, that among Puerto Rican adults, residence in the mainland US or in Puerto Rico was not associated with having more asthma exacerbations.

In a recent U.S. nationwide study of HL adults, the adjusted prevalence of current asthma was highest in Puerto Ricans and lowest in Mexicans and other HL subgroups (including Dominicans and Central/South Americans), with intermediate values in Cubans (29). Puerto Ricans have also been shown to have higher age-adjusted mortality rates from asthma than Cubans, Mexicans, OHL, and Caucasian Americans (30), though those findings have to be interpreted with caution because they were based on death certificates and thus susceptible to potential misclassification of HL subgroup or asthma. Among HL adults with asthma, Puerto Ricans have been shown to have worse lung function than OHL (31).

Consistent with and expanding on prior results for prevalence, lung function, and mortality, we show that Puerto Rican adults with moderate/severe asthma have greater disease morbidity than OHL with moderate to severe persistent asthma. Although a previous analysis of data from the 2001–2009 National Health Interview Survey showed that Puerto Ricans had a higher prevalence of ER/UC visits for asthma than Caucasian and OHL, that study included subjects with self-reported asthma (and thus all degrees of asthma severity) and lacked data on specific HL subgroups or other indicators of asthma morbidity (e.g., corticosteroids bursts) and asthma control (32).

Previous studies suggest that potential explanations for the high asthma burden among Puerto Ricans include psychosocial stressors such as poverty and depression (13), obesity, and medical comorbidities (7). Since our results were robust to adjustment for multiple covariates (age, sex, BMI, household income, preferred language, asthma controller therapy, medical comorbidities, perceived stress, employment, education, smoking status, depression, FeNO and peripheral blood eosinophil levels), other risk factors such as prematurity, diet, or air pollutants, with controller medications may help explain the high asthma burden among Puerto Ricans(4).

We grouped Puerto Ricans with Cuban & Dominicans because of their similar cultural and ancestral heritage (18, 19), yet asthma morbidity in Cuban & Dominicans was lower than that in Puerto Ricans. Our findings for discrepant asthma morbidity among Caribbean HL subgroups are consistent with prior reports for asthma prevalence in children and adults(29, 33). In a study of HL children and adults living in the same buildings in New York City, asthma prevalence was lower in Dominicans (5.3%) than in Puerto Ricans (13.2%), and this difference remained significant after adjustment for household size, education status, use of home remedies, and country where education was attained(33). Similarly, Puerto Rican adults have been previously shown to have a higher asthma prevalence than Cubans(29). In the current study, Puerto Ricans had higher odds of healthcare utilization and ER/UC visits than Cuban & Dominicans. We found only increased corticosteroid bursts in Cuban & Dominicans compared to OHL. However, some of the observed differences could be partly explained by regional variability in asthma morbidity, as Puerto Ricans and Cuban & Dominicans tended to be recruited from the same regions and we could not adjust for recruitment region due to co-linearity with self-identified ethnicity. We speculate that differences in respiratory viral infection patterns (34), healthcare utilization rates in urban vs rural centers (35), or other unknown confounders may underlie any US regional variability in asthma morbidity measures observed.

In contrast to our findings for asthma morbidity, baseline asthma control was similar between Caribbean HL and OHL, likely reflecting participant selection for uncontrolled asthma according to the PREPARE trial eligibility criteria. Of note, however, we show that Puerto Ricans residing in the US mainland had worse asthma control—but not asthma morbidity measures—than those residing in Puerto Rico. These results are consistent with those from a study that reported greater asthma severity among Puerto Rican children living in Rhode Island than in those living in Puerto Rico (36). Yet another study showed that Puerto Rican children living in Puerto Rico had a higher prevalence of lifetime asthma and lifetime asthma hospitalizations than those living in the US mainland(37).

Our study has several limitations. First, data on asthma exacerbations were self-reported and retrospectively assessed, and thus susceptible to recall bias. However, any recall bias is likely non-differential across HL ethnic subgroups. Second, many patients may not easily distinguish between an ER or UC visits or hospitalizations, which adds imprecision to our ascertainment, especially since they were based on self-report. However, our results are supported by our healthcare utilization data(38–40), which merged ER/UC visits with hospitalizations and tracked well with the ER/UC visit results. Healthcare utilization accounts for a quarter of direct asthma costs in the US, which further validates investigating this outcome. Third, we did not capture genetic data for the PREPARE pragmatic trial. Therefore, our results showing no difference in asthma morbidity measures between Black and non-Black HL are possibly due to imprecision in self-reported race. Given structural racism and colorism, Black racial self-identification among HL is likely underreported. Fourth, the baseline data used in our analyses does not account for differences in factors such as adherence to controller therapy regimens and inhaler technique, which are associated with worse asthma-related morbidity(41), and justify the parent PREPARE trial. Fifth, we lacked data on potential confounders of the relation between HL subgroup and asthma morbidity or control, including diet, and pollutants. Sixth, our cross-sectional study design does not allow us to establish causality between HL subgroups and asthma morbidity measures. Seventh, our cohort was disproportionately represented by women (83%), which we suspect may be due to clinical trial recruitment selection biases within our population; our findings may not be generalizable to men. Finally, our cohort was composed of patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma, and therefore the generalizability of our findings may be limited among Latinx populations with milder asthma.

In conclusion, our results suggest that Caribbean Hispanic Latinx adults with moderate to severe persistent asthma, particularly Puerto Ricans, have worse asthma morbidity than OHL. Novel preventive strategies are needed to reduce healthcare utilization in this highly impacted population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all study participants and their families for trusting us with their time and dedication.

We also acknowledge the several stakeholders listed below who were active in developing the study design and implementation of this study, offering expert advice throughout this project. Patient Partner Stakeholders: Alex Colon Moya; Aracelis Diaz; Bridget Hickson; Margarita Lorenzi; Suzanne Madison; Kathy Monteiro; Wilfredo Morales-Cosme; Alexander Muniz Ruiz; Addie Perez; Richard Redond; Dennis Reid; Marsha Santiago; Opal Thompson; Joyce Wade and Mary White. Professional Society Stakeholders: Rubin Cohen, MD, MSc, FACP, FCCP, FCCM; Tamera Coyne-Beasley, MD, MPH, FAAP, FSAHM; Patricia Finn, MD; Michael Foggs, MD; Robert Lemanske, MD; Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP. Expert Scientific Advisors: Michelle M. Cloutier, MD; Giselle Mosnaim, MD; Wanda Phipatanakul, MD, MS; Cynthia S. Rand, PhD; Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc. Health Policy Experts: Sarah Alwardt, PhD; Tangita Daramola, MD, CFMM; Gretchen Hammer, MPH; Arif M. Khan, MD; Troy Trygstad, MD, CCNC. Study Site Investigators: Andrea J. Apter, MD; Paula J. Busse, MD; Rafael A. Calderon-Candelario, MD, MSc; Thomas B. Casale, MD; Ku-Lang Chang, MD, FAAFP; Geoffrey Chupp, MD; Laura P. Hurley, MD, MPH; Sunit Jariwal, MD; Elina Jerscow, MD; David C. Kaelber, MD, PhD, MPH; Sybille M. Liautaud, MD; M. Diane McKee, MD, MS; Sylvette Nazario, MD; Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD; Isaretta L. Riley, MD, MPH; Paul M. Stranges, PharmD; Hazel Tapp, PhD; Jennifer Trevor, MD; Juan P. Wisnivesky, MD, DrPH); Study Sites Staff: Tiffany Bendelow, MPH, CCRP; Lauren Bielick; Michelle Campbell Hayes; Erika M. Coleman, BS; Jose Diarte Ortiz, MPH; Lynn Fukushima, RN, MSN; Nicole P. Grant, MS, CCRP; Hernidia Guerra, BA; Hilde Heyn; Renita Holmes; Bryonna Jackson, MS; Mary Jo Day, LPN; Sylvia Johnson; Tiffani Kaage, CCRC; Claudia Lechuga, MS; Carese Lee; ; Brianna M. McQuade, PharmD, BCACP, MHPE; Kathleen Mottus, PhD; Melissa Navarro, RN; Grace Ndicu; Angela Nuñez, MA; Pamela Pak; Luzmercy Perez; Matias E. Pollevick, BS; Walter Ramos-Amador, MPH, MS; Patricia Rebolledo; Jennifer Rees, RN, CPF, CRN; Sarah B. Romain, BA, BSN; Benjamin Joseph Rooks, MS; Jasmin Sanchez; Catherine R. Smith, CMA (AAMA), CCRC; Lindsay E. Shade, MHS, PA-C; Jeremy Thomas; Zinnia Valdes. Coordinators from the American Academy of Family Physicians: Alicia Brooks-Greisen, BA; Ileana Cepeda, MP; Angie Lanigan, MPA, RD, LD; Cory Lutgen, BA; Elizabeth Staton, MSTC; Carolyn Valdez, BSN, RN. DartNet Institute Data Support: Shaddai Amolitos, BS; Gabriela Gaona Villarreal, MPH. Medical writer, Julia Harder PharmD.

Funding information:

This work was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Project Program Award (PCS-1504-30283) (Dr. Israel). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. Additionally, this work was supported by grant UL1TR002489 (Dr. Hernandez), K23AI125785 from NIAID and the ALA/AAAAI Allergic Respiratory Diseases Award (AI-835475) to Dr. Cardet, and the Gloria M. and Anthony C. Simboli Distinguished Chair in Asthma Research award to Dr. Israel. Dr. Celedón’s contribution was supported by grants HL152475, HL117191, and MD011764 from the U.S. NIH.

Summary conflict of interest statements:

Dr. Cardet reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, GSK, and Genentech for work in advisory boards. Dr. Shenoy reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca and Genentech for working in advisory boards. Dr. Celedón reports receiving research materials from Pharmavite (vitamin D and placebo capsules) and GSK and Merck (inhaled steroids) to provide medications free of cost to participants in NIH-funded studies, unrelated to the current work. Dr. Pinto-Plata reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim for work in advisory boards. Dr. Fuhlbrigge is an unpaid consultant to AstraZeneca for the development of outcome measures for asthma and COPD clinical trials and a consultant to Novartis on epidemiologic analyses related to asthma control. Dr. Pace has received research grants from and is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and a research grant from AstraZeneca. Dr. Wechsler received grants or fees from Novartis, Sanofi, Regeneron, Genentech, Sentien, Restorbio, Equillium, Genzyme, Cohero Health, Teva, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, GSK, Cytoreason, Cerecor, Sound biologic, Incyte, Kinaset. Dr. Israel received support from AstraZeneca, Avillion Mandala/Denali, Gossamer Bio, NIH, Novartis, paid royalty or license from Wolters Kluwer, consulting fees from AB Science, Allergy and Asthma Network, Amgen, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Avillion, Biometry, Equillium, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, NHLBI, Novartis, Pneuma Respiratory, PPS Health, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, TEVA and Cowen. The rest of the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- ACT®

Asthma Control Test

- AA/B

African American/Black

- APGAR

Activities, Persistent, triGGers, Asthma medications, Response to therapy

- ASUI

Asthma Symptom Utility Index

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- C&D

Cubans and Dominicans

- CHL

Caribbean Hispanic Latinx (Puerto Rican, Cubans and Dominicans)

- ER

Emergency room

- FeNO

Fractional Exhaled nitric oxide

- HL

Hispanic/Latinx

- ICS

Inhaled corticosteroid

- OHL

Other Hispanic Latinx (Mexicans, Spaniards, Central/South Americans)

- PARTICS

Patient-Activated Reliever-Triggered Inhaled CorticoSteroid

- PCORI

Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute

- PR

Puerto Ricans

- PREPARE

PeRson EmPowered Asthma RElief

- SABA

Short acting beta agonist

- UC

Urgent care

- US

United States

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT02995733

References:

- 1.El Burai Félix S, Bailey CM, Zahran HS. Asthma prevalence among Hispanic adults in Puerto Rico and Hispanic adults of Puerto Rican descent in the United States – results from two national surveys. Journal of Asthma. 2015;52(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yaghoubi M, Adibi A, Safari A, FitzGerald JM, Sadatsafavi M. The Projected Economic and Health Burden of Uncontrolled Asthma in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(9):1102–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salari K, Burchard EG. Latino populations: a unique opportunity for epidemiological research of asthma. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21 Suppl 3:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosser FJ, Forno E, Cooper PJ, Celedón JC. Asthma in Hispanics. An 8-year update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(11):1316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunninghake GM, Weiss ST, Celedón JC. Asthma in Hispanics. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;173(2):143–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose D, Mannino DM, Leaderer BP. Asthma prevalence among US adults, 1998–2000: role of Puerto Rican ethnicity and behavioral and geographic factors. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):880–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szentpetery SE, Forno E, Canino G, Celedon JC. Asthma in Puerto Ricans: Lessons from a high-risk population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1556–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchard EG, Avila PC, Nazario S, Casal J, Torres A, Rodriguez-Santana JR, et al. Lower bronchodilator responsiveness in Puerto Rican than in Mexican subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wohlford EM, Borrell LN, Elhawary JR, Plotkin B, Oh SS, Nuckton TJ, et al. Differential asthma odds following respiratory infection in children from three minority populations. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0231782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Boutaoui N, Brehm JM, Han YY, Schmitz C, Cressley A, et al. ADCYAP1R1 and asthma in Puerto Rican children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(6):584–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Q, Forno E, Cardenas A, Qi C, Han YY, Acosta-Perez E, et al. Exposure to violence, chronic stress, nasal DNA methylation, and atopic asthma in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(7):1896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landeo-Gutierrez J, Han YY, Forno E, Rosser FJ, Acosta-Perez E, Canino G, et al. Risk factors for atopic and nonatopic asthma in Puerto Rican children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(9):2246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han YY, Forno E, Canino G, Celedon JC. Psychosocial risk factors and asthma among adults in Puerto Rico. J Asthma. 2019;56(6):653–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramratnam SK, Han YY, Rosas-Salazar C, Forno E, Brehm JM, Rosser F, et al. Exposure to gun violence and asthma among children in Puerto Rico. Respir Med. 2015;109(8):975–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller GE, Chen E. Life stress and diminished expression of genes encoding glucocorticoid receptor and beta2-adrenergic receptor in children with asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(14):5496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pino-Yanes M, Thakur N, Gignoux CR, Galanter JM, Roth LA, Eng C, et al. Genetic ancestry influences asthma susceptibility and lung function among Latinos. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vergara C, Caraballo L, Mercado D, Jimenez S, Rojas W, Rafaels N, et al. African ancestry is associated with risk of asthma and high total serum IgE in a population from the Caribbean Coast of Colombia. Human Genetics. 2009;125(5–6):565–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(1):37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortes-Lima C, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Marin-Padron LC, Gomez-Cabezas EJ, Baekvad-Hansen M, Hansen CS, et al. Exploring Cuba’s population structure and demographic history using genome-wide data. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israel E, Cardet JC, Carroll JK, Fuhlbrigge AL, Pace WD, Maher NE, et al. A randomized, open-label, pragmatic study to assess reliever-triggered inhaled corticosteroid in African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults with asthma: Design and methods of the PREPARE trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;101:106246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ASPE Poverty Guidelines [Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

- 22.Health Resources & Services Administration--Federal Poverty Guidelines.

- 23.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, Albers FC. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revicki DA, Leidy NK, Brennan-Diemer F, Sorensen S, Togias A. Integrating patient preferences into health outcomes assessment: the multiattribute Asthma Symptom Utility Index. Chest. 1998;114(4):998–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rank MA, Bertram S, Wollan P, Yawn RA, Yawn BP. Comparing the Asthma APGAR system and the Asthma Control Test in a multicenter primary care sample. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(7):917–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Y-Y, Jerschow E, Forno E, Hua S, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Perreira KM, et al. Dietary Patterns, Asthma, and Lung Function in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2020;17(3):293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homa DM, Mannino DM, Lara M. Asthma mortality in U.S. Hispanics of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban heritage, 1990–1995. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):504–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaVange L, Davis SM, Hankinson J, Enright P, Wilson R, Barr RG, et al. Spirometry Reference Equations from the HCHS/SOL (Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(8):993–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Law HZ, Oraka E, Mannino DM. The role of income in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in emergency room and urgent care center visits for asthma-United States, 2001–2009. J Asthma. 2011;48(4):405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asthma and Latino cultures: different prevalence reported among groups sharing the same environment. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(6):929–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/nrevss/hmpv/region.html, accessed 2/8/2022

- 35.Bleecker ER, Gandhi H, Gilbert I, Murphy KR, Chupp GL. Mapping geographic variability of severe uncontrolled asthma in the United States: Management implications. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022. Jan;128(1):78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.09.025. Epub 2021 Oct 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esteban CA, Klein RB, McQuaid EL, Fritz GK, Seifer R, Kopel SJ, et al. Conundrums in childhood asthma severity, control, and health care use: Puerto Rico versus Rhode Island. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(2):238–44, 44 e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen RT, Canino GJ, Bird HR, Shen S, Rosner BA, Celedo’N JC. Area of Residence, Birthplace, and Asthma in Puerto Rican Children. Chest. 2007;131(5):1331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yancey SW, Ortega HG, Keene ON, Mayer B, Gunsoy NB, Brightling CE, et al. Meta-analysis of asthma-related hospitalization in mepolizumab studies of severe eosinophilic asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017;139(4):1167–75.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, D’Onofrio G, Pines JM, Ross JS, et al. Use of Hospital-Based Acute Care Among Patients Recently Discharged From the Hospital. JAMA. 2013;309(4):364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, Albers FC. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2017;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vervloet M, van Dijk L, Spreeuwenberg P, Price D, Chisholm A, Van Ganse E, et al. The Relationship Between Real-World Inhaled Corticosteroid Adherence and Asthma Outcomes: A Multilevel Approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):626–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.