Abstract

Invariant natural killer T cells (iNKTs) are innate-like lipid-reactive T lymphocytes that express an invariant T-cell receptor (TCR). Following engagement of the iTCR, iNKTs rapidly secrete copious amounts of Th1 and Th2 cytokines and promote the functions of several immune cells including NK, T, B and dendritic cells. Accordingly, iNKTs bridge the innate and adaptive immune responses and modulate susceptibility to autoimmunity, infection, allergy and cancer. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is one of the most effective treatments for patients with hematologic malignancies. However, the beneficial graft versus leukemia (GvL) effect mediated by the conventional T cells contained within the allograft is often hampered by the concurrent occurrence of graft versus host disease (GvHD). Thus, developing strategies that can dissociate GvHD from GvL remain clinically challenging. Several preclinical and clinical studies demonstrate that iNKTs significantly attenuate GvHD without abrogating the GvL effect. Besides preserving the GvL activity of the donor graft, iNKTs themselves exert antitumor immune responses via direct and indirect mechanisms. Herein, we review the various mechanisms by which iNKTs provide antitumor immunity and discuss their roles in GvHD suppression. We also highlight the opportunities and obstacles in manipulating iNKTs for use in the cellular therapy of hematologic malignancies.

INTRODUCTION

Invariant natural killer T cells (iNKTs) or type I NKTs are unique innate-like T lymphocytes that express an invariant T-cell receptor (TCR)-α chain, Vα14-Jα18, which often pairs with Vβ8.2, Vβ7 or Vβ2 (Vα24- Jα18, Vβ11 in humans).1,2 This iTCR confers reactivity to glycolipid antigens (Ags), such as the prototypical iNKT agonist, α-galactosylceramide (αGC).3 The less well-characterized, type II NKTs are also CD1d-restricted but exhibit diverse TCRαβ chain usage and recognize sulfatide Ags.1,4,5 The salient features of human and murine iNKTs and the differences between type I and type II NKTs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.1,6–11 iNKTs develop in the thymus from CD1d-restricted CD4+CD8+DP thymocytes that progress through four different stages of maturation: CD24hiCD44loNK1.1− (Stage 0), CD24loCD44loNK1.1− (Stage 1), CD24loCD44hiNK1.1− (Stage 2), and finally CD24loCD44hiNK1.1+ (Stage 3).10 As they go through these developmental stages, iNKTs upregulate NK cell markers (for example, NKG2D and Ly49 receptors), CD69 and CD122, and acquire distinct effector functions12 that are tightly regulated by several transcription factors, signaling molecules, surface receptors and cytokines.1,11,13

Table 1.

Characteristics of mouse and human invariant NKT cells

| Features | Mouse | Human |

|---|---|---|

| Receptors and ligands | ||

| NK cell markers | NK1.1− (immature and mature) NK1.1+ (mature) | CD161− (immature) CD161+ (mature) |

| TCR αβ chain | Vα14 Jα18 Vβ8.2, Vβ7, Vβ2 | Vα24 Jα18 Vβ11 |

| CD1d restricted | Yes | Yes |

| CD4/CD8 expression | CD4+ or CD4−CD8− (DN) | CD4+, CD4− (DN or CD8+) |

| αGC reactivity | Yes | Yes |

| Selecting ligand | Controversial | Controversial |

| Tissue distribution | ||

| Blood | 0.2–0.5% | 0.008–1.176% |

| Thymus | ~0.5% | <0.1% |

| Liver | 20–30% | ~1% |

| Spleen | ~1% | Unknown |

| Functions | ||

| Cytokine production | No clear distinction in cytokine production between CD4+ and DN subsets | CD4+: Th2 (IL-4) CD4−: Th1 (IFN-γ) |

| Cytotoxicity | CD4+ and DN cells are equally cytotoxic against CD1d+ tumors; DN cells more effective in controlling CD1d− tumors | CD4− cells more cytotoxic than CD4+ subset |

Table 2.

Differences and similarities between conventional T and NKT cells

| Features | αβ T | NKT cells |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Type II | ||

| TCR repertoire | Diverse | Vα14 Jα18, Vβ8.2, Vβ7, Vβ2 | Diverse, some have Vα3.2 Jα9, Vα8 Jα9, Vβ8 |

| MHC-restriction | MHC I or MHC II | CD1d | CD1d |

| Selecting cells | TEC | DP | DP |

| TCR ligands | Peptide antigens | Glycolipids (αGC, β-GlcCer, β-ManCer), diacylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol mannoside | Sulfatide, lyso-sulfatide |

| Positive selection | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CD4/CD8 expression | CD4+ or CD8+ | CD4+ or DN | CD4+ or DN |

| Activated Phenotype | After Ag exposure | Yes | Yes |

| SLAM-SAP dependent | No | Yes | Yes |

| PLZF expression | No | Yes | Yes |

| αGC reactivity | No | Yes | No |

| Antitumor response | Direct cytotoxicity perforin, Fas-FasL or TRAIL-mediated | Direct cytotoxicity: (perforin and Fas–FasL) indirect cytotoxicity: (IFN-γ, transactivation of NK, CD8+T and DC) | Suppressive (Th2 cytokines), counter-regulate type I antitumor activities |

| Role in GvHD | Donor T cells mediate and Tregs suppress GvHD | Ameliorate GvHD via IL-4 production and Treg expansion | Attenuate GvHD via both IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion |

Abbreviations: αGC =alpha-galactosylceramide; β-GlcCer= β-glycosylceramide; β-ManCer=β-mannosylceramide; DC=dendritic cell; DN=double negative; DP=double positive; IL-4 =interleukin-4; IFN-γ = Interferon-γ; NK=natural killer; NKT =natural killer T; PLZF=promyelocytic zinc finger; SAP =SLAM-associated protein; SLAM =signaling lymphocytic activation molecule; TCR=T-cell receptor; TEC =thymic epithelial cell; TRAIL = TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; Treg = regulatory T cell. Information presented in this table are for murine NKT cells and are from references 1–5, 10–12, 43, 44, 71, 73, 74 and 76.

Following iTCR engagement, iNKTs rapidly secrete cytokines and upregulate co-stimulatory receptors, which activate other immune cells including dendritic cells (DC), macrophages, NK, B and T cells.10 As a result, activation of iNKTs modulates an array of normal and pathogenic immune responses. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potent curative treatment that is widely used for patients with relapsed or refractory hematological malignancies.14 The donor T cells in the allograft target the leukemia cells to exert a beneficial graft versus leukemia (GvL) effect.14 However, dysregulated activation and proliferation of donor T cells in the allograft leads to immune-mediated destruction of host tissues resulting in graft versus host disease (GvHD), a serious complication of allogeneic HSCT.14 Several studies demonstrate that iNKTs significantly attenuate GvHD,15–18 whereas preserving the GvL effect.19–22 In addition, iNKTs themselves mediate anti-leukemia activity via direct and indirect mechanisms23 and also regulate antiviral, -bacterial and -fungal immune responses.24 Together, these functional properties of iNKTs make them ideal candidates for use in cancer therapy. In this review, we discuss the antitumor activities of iNKTs and their roles in GvHD attenuation.

iNKTS AND ANTITUMOR IMMUNITY

iNKTs protect against tumors

Several studies demonstrate that iNKTs mediate protection from tumors. In mice heterozygous for mutations in the tumor suppressor p53, loss of iNKTs enhances susceptibility to tumors.25 Moreover, treatment of iNKT-deficient CD1d−/− and Jα18−/− mice with a carcinogen results in increased incidence and earlier onset of tumors when compared with similarly treated wild-type mice.26 Conversely, reconstitution of iNKTs into Jα18−/− mice prevents the growth of chemically induced sarcomas.27 Furthermore, treatment with αGC can attenuate the growth of adoptively transferred,28,29 carcinogen-induced,27,30 or spontaneous tumors31 in mice, largely via an interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-dependent manner. Interestingly, the recently described novel agonist of human and murine iNKTs, β-mannosylceramide, confers protection against tumors via a different mechanism involving production of nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-α.32 Recent studies also show that iNKTs protect against B-cell lymphomas in mice33 and that infection of humanized mice with EBV promotes the generation of cytotoxic iNKTs, which produce IFN-γ and enhance T-cell killing of EBV-positive human tumor cells.34 Finally, generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from mature iNKTs can activate and expand Ag-specific CD8+T cell responses to provide protection against leukemia in mice.35

Data on the antitumor functions of human iNKTs are more indirect. Patients with various types of cancer often exhibit reduced numbers of peripheral blood iNKTs and these cells are often impaired in their functions.36–38 For instance, patients with progressive multiple myeloma have decreased frequency of iNKTs and marked deficiency in αGC-dependent IFN-γ production.39 Conversely, in patients with neuroblastoma,40 colorectal41 and head and neck carcinoma,42 increased numbers of peripheral blood and/or tumor-infiltrating iNKTs are associated with a more favorable response to therapy. Collectively, these data reveal an important role for iNKTs in host immunity against various cancers. In contrast, type II NKTs (Table 2) not only downregulate immune surveillance against tumors and facilitate their growth, but they are also known to counter-regulate the antitumor activity of iNKTs.43,44

Antitumor mechanisms of iNKTs

iNKTs mediate their antitumor activity via multiple mechanisms. Their dominant mode of action involves the activation of other cytolytic effectors such as CD8+T and NK cells.23,45,46 Indeed, αGC or cytokine-stimulated iNKTs robustly produce IFN-γ and upregulate the expression of CD40 ligand. As a result, they promote DC activation and enhance DC-mediated priming of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+T-cell responses.47 iNKT-DC interactions also stimulate DC production of IL-12, which serves to further augment NK- and CD8+T cell lysis of tumors23 (Figure 1a).

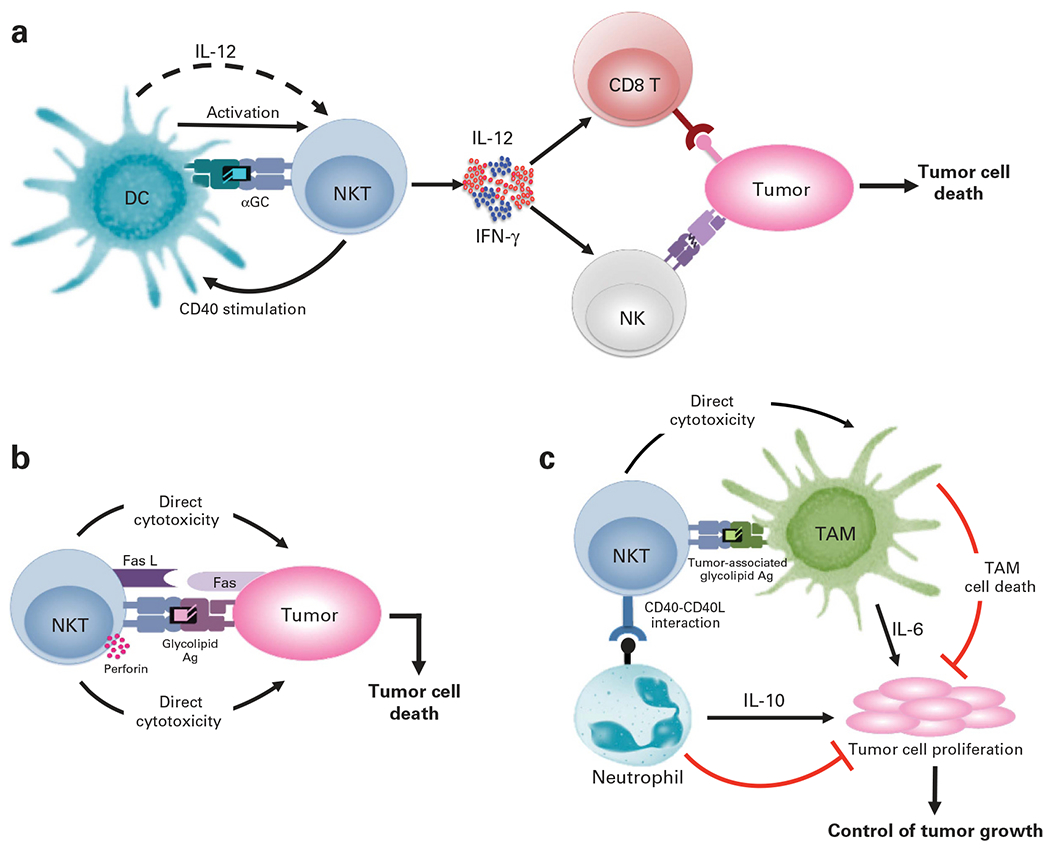

Figure 1.

Antitumor mechanisms of iNKTs. (a) Indirect mechanism of iNKT cytotoxicity. The cross-talk between iNKTs and Ag-presenting cells (such as DCs), presenting a tumor-derived glycolipid, leads to the activation of iNKTs, IFN-γ and CD40 stimulation. This iNKT-derived IFN-γ induces DC production of IL-12, which further augments IFN-γ production by iNKT and NK cells, and serves to stimulate CD8+ T cell- and NK cell-dependent killing of tumor cells. (b) iNKTs recognize glycolipid Ags presented by CD1d on tumor cells and mount direct cytotoxicity via perforin/granzyme exocytosis or Fas–Fas ligand (Fas L) interactions. (c) iNKTs can also limit tumor growth via their interactions with immunosuppressive cells that promote tumor growth such as TAMs and IL-10-producing neutrophils. Although iNKTs can directly kill TAMs, they alleviate the suppressive effect of the neutrophils via CD40–CD40L interactions.

In addition to their immune-stimulatory functions, iNKTs also function as cytotoxic effectors (Figure 1b). Consistent with this notion, mature iNKTs basally express cytolytic proteins (perforin and granzymes)12,48,49 and can be induced to upregulate death-promoting molecules such as Fas ligand and TRAIL.49–51 Others and we observe that human and murine iNKTs mount potent cyotoxic responses to numerous CD1d+ tumors in vitro and in vivo.52–55 Furthermore, our studies demonstrate that iNKT-mediated cytotoxicity is critically dependent on CD1d-mediated lipid Ag presentation, functional TCR signaling, the adaptor protein signaling lymphocytic activation molecule-associated protein (SAP) and the tyrosine kinase Fyn (SAP-binding protein) as well as perforin expression; as loss or interference with any of these factors significantly reduced human and murine iNKT antitumor responses.52,55 As several hematological malignancies (including AML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, B-cell CLL, pediatric ALL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma) express CD1d,56 they serve as potential targets for direct iNKT-cell recognition. However, many normal and transformed cells do not express CD1d and are, therefore, not targeted by such iNKT TCR-dependent mechanisms. In this context, recent studies show that human iNKTs kill target cells expressing NKG2D ligands in an NKG2D-dependent and CD1d-independent manner.57 Furthermore, engagement of NKG2D promotes iNKT-cell activation in response to weak TCR agonists, suggesting that NKG2D also functions as a co-stimulatory receptor in these cells.57

iNKTs can also impede tumor growth by killing or inhibiting immunosuppressive cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) that facilitate tumor growth, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (Figure 1c).58,59 Studies have shown that hypoxic signaling within the TME results in sustained activation of TAMs and increased IL-6 production that favors tumor progression.60 Although iNKTs colocalize with IL-6-producing TAMs, the hypoxic conditions within the TME inhibit iNKT activation.58 Interestingly, recent studies show that IL-15 protects iNKTs from hypoxia, such that iNKTs can directly kill the tumor-associated macrophages in a CD1d-dependent manner and provide antitumor immunity.59 Other potential targets of iNKTs within the TME include myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)61 and IL-10 producing neutrophils.62 iNKTs directly interact with these cells in a CD1d and CD40-dependent manner to reverse their suppressive phenotype and restore specific antiviral61 or antitumor responses62 (Figure 1c).

iNKT-based cancer immunotherapy

Several clinical trials have examined whether administration of α GC63 or αGC-loaded DCs with64 or without iNKTs65–67 might prove beneficial in the treatment of cancer. These studies demonstrated that iNKT therapies are well tolerated and induce an objective clinical response in a subset of patients. As discussed above, maximal tumor-directed iNKT responses require tumor cell expression of CD1d. However, many tumors downregulate CD1d and thus evade iNKT recognition.68 Two recent studies demonstrated that iNKTs can mediate antitumor activity in a tumor Ag-specific yet CD1d-independent manner.69,70 In the first study, systemic administration of αGC-loaded soluble CD1d fused with anti-HER2 single-chain Ab Fv fragment significantly reduced lung metastasis of HER2-expressing B16 melanoma cells.69 This antitumor activity of the CD1d–anti-HER2 fusion protein was associated with HER2-specific tumor localization and accumulation of iNKT, NK and T cells at the tumor site. In the second study,70 primary human iNKTs were engineered to express a chimeric Ag receptor (CAR) against GD2, a disialoganglioside that is highly expressed by neuroblastoma cells. These CAR.GD2 iNKTs localized at the tumor site and exhibited robust antitumor activity against neuroblastoma cells.70 Collectively, these studies exemplify how the antitumor activities of iNKTs can be harnessed for clinical application to treat a wider array of cancers that are currently difficult to cure. Finally, as activated iNKTs promote the antitumor functions of NK, T and B cells, future clinical trials involving the co-transfer of tumor-targeted conventional T cells and iNKTs may induce better clinical responses than those obtained using T cells alone.

ROLE OF iNKTS IN GvHD

iNKTs ameliorate GvHD in preclinical models

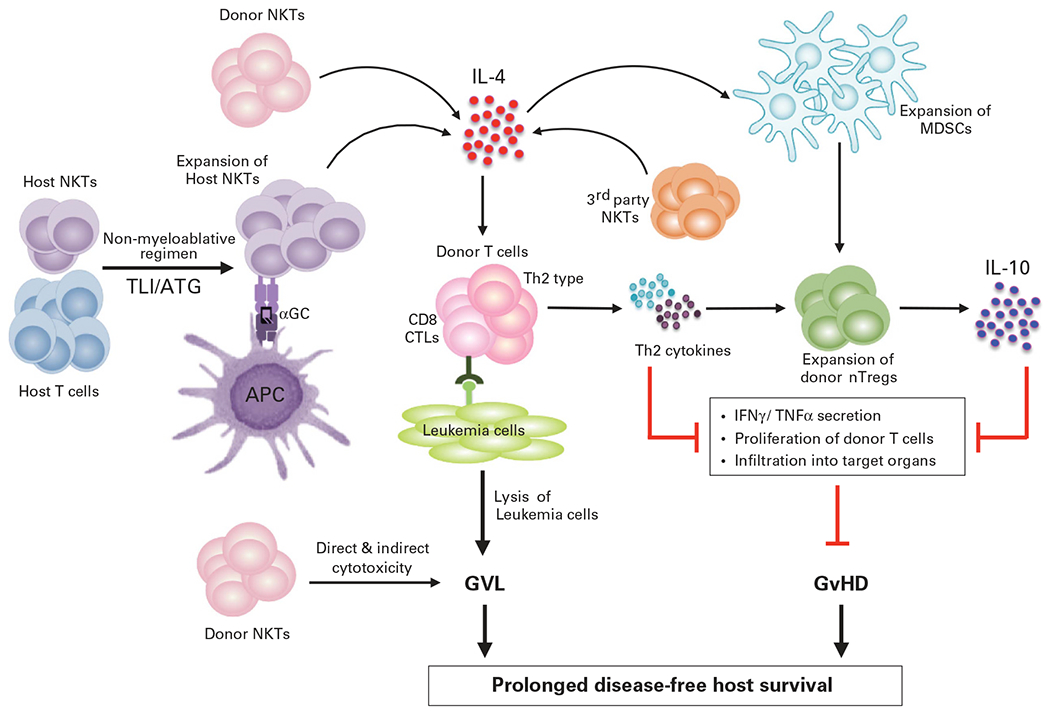

Non-myeloablative host-conditioning markedly reduces early toxicity post transplantation as compared with the myeloablative regimens; however, acute and chronic GvHD remain a significant clinical challenge for both these approaches.71 Early studies demonstrated that non-myeloablative host-conditioning with fractionated total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) prior to transfer of allogeneic bone marrow (BM) cells and splenocytes attenuates GvHD via induction of regulatory ‘natural suppressor’ T cells in the host, which were later identified as iNKTs.16 This increase in host iNKTs is associated with elevated IL-4 secretion and protection against GvHD.16 Consistent with the IL-4-dependent protective role of host iNKTs, IL-4−/−, CD1d−/− and Jα18−/− transplant recipient mice rapidly succumb to GvHD.16–18,72 Furthermore, although host iNKTs promote donor chimerism,16,72 they polarize donor T cells toward a Th2 cytokine pattern and inhibit their early expansion and infiltration into GvHD target organs72 (Figure 2). Importantly, these cells retain the GvL activity of the graft, which is dependent upon donor CD8+ T cells and their production of perforin.19

Figure 2.

iNKTs protect from GvHD but retain the GvL activity. Reduced intensity host-conditioning with TLI and ATG allows host iNKT expansion. Both host and donor iNKTs interact with APCs via CD1d to produce IL-4 that in turn skews donor T cells toward a Th2 cytokine bias. Both host and donor iNKTs also promote nTreg expansion in an IL-4-dependent manner that can inhibit donor T-cell proliferation and migration to GvHD target organs. Recently described, third-party CD4+ iNKTs also inhibit T-cell proliferation, promote Th2-biased cytokine response as well as expansion of donor MDSCs. These donor MDSCs are crucial for nTreg expansion and protection from GvHD lethality. Importantly, iNKTs (host, donor or third party) do not abrogate donor T-cell anti-leukemia activity. Furthermore, iNKTs can also directly kill the leukemia cells and contribute to the GvL effect. Taken together, attenuation of GvHD without loss of the GvL activity decreases tumor burden and improves overall survival of the host.

Donor iNKTs also attenuate GvHD in an IL-4-dependent manner.15 Recent elegant studies using luciferase-expressing donor T and iNKTs lend insights into the migration, proliferation and suppressive effect of donor CD4+iNKTs in a MHC mismatch preclinical model of GvHD.20,22 In these studies, donor CD4+iNKTs robustly expanded in secondary lymphoid organs and migrated to GvHD target organs, as did the donor T cells.20 However, adoptive transfer of low numbers of donor CD4+ iNKTs ameliorated GvHD pathology and prolonged survival by inhibiting donor T-cell proliferation and activation, promoting a Th2-biased cytokine pattern22 and significantly downregulating IFN-γ and TNF-α production by donor T cells.20,22 Consistent with prior studies,15 donor CD4+ iNKTs attenuated GvHD in an IL-4-dependent manner, without abrogating the GvL effect.22 Other recent studies show that low numbers of ‘third party’ iNKTs also protect from lethal GvHD with the same effectiveness as donor CD4+iNKTs without abrogating the GvL effect.21 Type II NKTs also has a protective role in GvHD,73,74 via production of both IFN-γ and IL-4; IFN-γ-producing BM type II NKTs induce Fas-dependent apoptosis of donor CD4+ and CD8+T cells, whereas the IL-4-producing cells skew the immune response toward a Th2 phenotype.74

iNKTs mediate protection from GvHD via Tregs

Minimal intensity conditioning with TLI/ATG promotes IL-10-producing donor Treg proliferation in wild type (WT) but not NKT cell-deficient hosts.18 Interestingly, adoptive transfer of WT but not IL-4−/− NKTs into Jα18−/− hosts restored Treg proliferation and protection from GvHD,18 suggesting that host iNKTs augment Treg expansion in an IL-4-dependent manner and this prevents donor T-cell expansion and induction of GvHD (Figure 2). Consistent with their protective role against GvHD, donor CD4+iNKTs promotes expansion of functional natural Tregs (nTregs) from the allograft.22 Depletion of Tregs from the graft is associated with abrogation of donor Treg expansion and loss of protection against GvHD, highlighting a critical role of donor Tregs in the regulation of GvHD pathogenesis.22 Besides Tregs, MDSCs also have immunoregulatory roles in allogeneic HSCT.75 Interestingly, ‘third party’ CD4+iNKTs that protect against GvHD also promote expansion of both donor nTregs and MDSCs.21 In the same study, depletion of MDSCs abrogated donor nTreg expansion and protection from GvHD, suggesting that the cross-talk between MDSCs and nTregs is crucial for iNKT cell-mediated protection against GvHD.21 Although both iNKTs and Tregs have important regulatory roles in GvHD,71,76,77 there are certain advantages of using iNKTs over Tregs in allogeneic HSCT as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Advantages of using iNKTs versus Tregs in allogeneic HSCT

| • Can be readily expanded from PBMCs or iPSCs to generate very large numbers for infusion during HSCT |

| • Easily identifiable by surface markers (iTCR, CD1d-tetramer reactivity) as opposed to Tregs that require intracellular staining for nuclear transcription factors (Foxp3 and Ikaros) |

| • MHC incompatibility not an issue owing to limited polymorphism of CD1d |

| • Very few iNKTs are required to mediate GvHD suppression; also persist longer than Tregs in vivo |

| • Both host and donor iNKTs can mediate protection from GvHD, whereas only donor but not host Tregs can do so |

| • iNKTs promote expansion of the few natural Tregs present in the allograft |

| • As CD1d is expressed on several hematological malignancies, they can be direct target for iNKT-cell recognition and cytotoxicity |

| • Although both iNKTs and Tregs can effectively separate the GvHD and GvL effects, only iNKTs have an inherent ability to contribute to the GvL effect via direct and indirect antitumor mechanisms |

| • iNKTs can provide protection from infections during the post-transplantation recovery period, as they can mediate antiviral, -fungal and -bacterial activities |

| • iNKTs contribute to hematopoiesis through secretion of GM-CSF and IL-3, as well as via direct recognition of CD1d expressed on hematopoietic progenitors |

Role of human iNKTs in clinical GvHD

Several clinical studies highlight a protective role for human iNKTs against GvHD. First, non-myeloablative conditioning with TLI/ATG prior to HSCT decreases the incidence of acute78,79 and chronic79 GvHD. This lower incidence of GvHD is associated with a higher iNKT/T cell ratio, increased IL-4 production and marked reduction in donor T-cell proliferation.78 Importantly, the TLI/ATG regimen does not abrogate the GvL effect, as evidenced by the high incidence of sustained complete remission (CR) among patients with active disease at the time of transplantation.79 Second, both CD4+ and CD4− subsets of iNKTs (Table 1) are reduced in patients with acute GvHD.80 Third, enhanced iNKT reconstitution post transplantation has been shown to be a predictive factor for an improved overall survival associated with reduction in GvHD without abrogation of the GvL effect.81 Fourth, lower numbers of CD4−iNKTs in the donor graft is associated with clinically significant GvHD in patients undergoing HLA-identical allogeneic HSCT.82 Last, in a recent study, the frequency of iNKTs in pediatric HSCT patients was significantly reduced in the relapsed but not the non-relapsing patient cohort.83 In the same study, there was no difference in the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells between the groups, suggesting that only the frequency of iNKTs correlates with a remission state after HSCT.83 Thus, in a clinical setting, increasing iNKT numbers in donor grafts with very few iNKTs (by adding back in vitro expanded iNKTs55,84–86 (Figure 3)), or adoptively transferring iNKTs into leukemia patients that fail to reconstitute the iNKT compartment early after allogeneic HSCT might provide an attractive strategy for suppressing GvHD and preventing leukemia relapse.

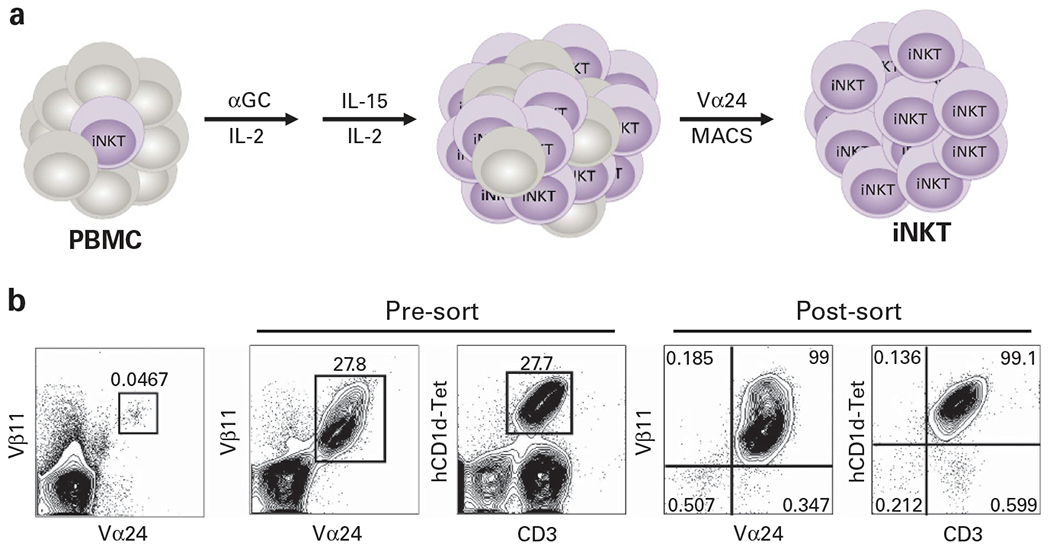

Figure 3.

In vitro expansion and isolation of human iNKTs. (a) Human PBMC are cultured in complete medium (Aim-V, 10% fetal calf serum; recombinant human (rh) IL-2 (50 U/mL)) and αGC (500 ng/mL)). After 4 days, cultures are supplemented with rhIL-15 (10 ng/mL) and rh IL-2 (10 U/mL) and 4–5 days later, iNKTs are purified by MACS sorting, based on expression of Vα24, the α-chain of the iNKT TCR. Using this approach, we observe that iNKTs can be expanded 500–1000-fold and it is therefore very feasible to obtain the large number of cells within a week. (b) Representative FACS plots demonstrate how iNKTs can be successfully expanded from the blood and isolated to >99% purity. Alternatively, iNKTs can be first isolated from PBMCs by MACS or high-speed cell sorting and then expanded in vitro in the presence of αGC and cytokines (IL-2, IL-7 and IL-15). For long-term cultures, iNKTs can be restimulated every 8–12 days with αGC-pulsed, irradiated autologous PBMC in the presence of cytokines.

Information on the graft composition of iNKTs in BM, PBSCs and CB is limited. There is only one study82 that has examined the frequencies of total as well as CD4+ and CD4− iNKTs in donor PBSC grafts. In a previous study,80 there was a significant difference in the number of reconstituted iNKTs in patients who received BMT and PBSC. The only variable associated with the number of iNKTs was the stem cell source (peripheral blood or BM). In PBSC recipients, the number of iNKTs was in the normal range within 1 month, whereas in the patients who received BMT, the iNKTs were not reconstituted within the first year post transplant. In another study, iNKT cells were reconstituted within a month after umbilical cord blood transplantation (UCBT).87 Taken together, these studies indicate that the graft composition of iNKT cells in BM, PBSC and CB are different, which may impact the kinetics of iNKT-cell reconstitution as well as their repertoire in the transplant recipients.

Another factor that may impact iNKT-cell reconstitution and function in patients is the use of the immunosuppressive drug to prevent GvHD. However, studies have shown that the administration of cyclosporine with short-term methotrexate does not significantly affect iNKT numbers or donor chimerism in BMT or PBSC recipients.80,81 Conversely, UCBT patients that received cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil had phenotypically and functionally immature iNKTs initially post engraftment but displayed rapid effector functions, including cytokine production and cytolytic activity within 3–6 months post-UCBT.87 Given that iNKT cell profiles are similar in CB and early after UCBT, these observations indicate that administration of the immunosuppressive drugs may only transiently impact iNKT-cell functions in the immediate post-transplant period, if at all.

Specific human iNKT subsets regulate the opposing pro-GvL and anti-GvHD effects

In transplant recipients, CD4− iNKTs reconstitute faster and attain functional maturity more rapidly than their CD4+ counterparts.83 Importantly, the CD4− iNKTs have a Th1 bias; they secrete higher amounts of IFN-γ than IL-4 and preferentially express perforin.8 Human CD4− (but not CD4+) iNKTs express innate immune recognition receptors such NKG2D, CD94 and NKG2A.8,57 Accordingly, human CD4− iNKTs kill target cells expressing NKG2D ligands in an NKG2D-dependent and CD1d-independent manner.57 It is thought that CD4− iNKTs not only promote GvL but also suppress GvHD. In support of this notion, in vitro studies demonstrated that CD4− iNKTs display direct cytotoxicity against CD1d-expressing mature myeloid DCs.82 In an allogeneic setting, alloreactivity of iNKTs depends on TCR-CD1d interactions as well as those involving activating killer Ig receptors (KIRs).88 Consistently, recent studies demonstrate that human iNKTs express KIRs including KIRDL4, KIR3DL2 and KIR2DL1.88 Thus, it is possible that donor CD4− iNKT cells downregulate GvHD by killing of host APCs (cells which perpetuate GvHD in secondary lymphoid organs) in a TCR-CD1d and KIR-dependent manner. On the other hand, CD4+ iNKT cells can ameliorate GvHD by their provision of IL-4,8,81 which can polarize the pathogenic donor T cells toward an anti-inflammatory Th2 response as well promote expansion of the regulatory T cells.18,89 We therefore favor the interpretation that the opposing pro-GvL and anti-GvHD effects are likely being mediated by distinct iNKT subsets that are each endowed with distinct cytokine profiles, resulting in a collectively beneficial effector response for transplant recipients.

Pharmacological manipulation of iNKTs for use in allogeneic HSCT Given the protective role of iNKTs in allogeneic HSCT, the use of αGC provides an attractive pharmacological approach to effectively separate the GvHD and GvL effects. Indeed, donor iNKTs expanded in vitro by stimulation with αGC attenuate GvHD.90,91 Furthermore, in vivo injection of αGC or OCH (a homologue of αGC) attenuates GvHD severity via host iNKT production of IL-4 and Th2 polarization of donor T cells.89 However, contradictory to these favorable observations, another study92 reported that the administration of αGC (but not its N-acyl variant, C20:2) induces hyper-acute GvHD and rapid mortality in mice. Exacerbation of GvHD in this study was associated with profound iNKT activation and IL-12 secretion by host DCs, resulting in NK- and T-cell activation and increased serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.92 Studies have shown that aqueous αGC when presented by DCs activates iNKTs, whereas liposomal αGC that is usually presented by B cells triggers IL-10 production by iNKT and B cells, resulting in expansion of tolerogenic DCs and generation of Tregs.93,94 In line with these observations, administration of the liposomal formulation of αGC (RGI-2001) prevents GvHD in mice (via expansion of nTregs) but retains the GvL effect.95 The safety and efficacy of this pharmacological approach is currently under investigation in HSCT patients with hematologic malignancies in a multi-center phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT013729209). In addition, progenipoietin-1, a chimeric cytokine that stimulates both G-CSF and Flt-3 L, has been shown to suppress GvHD96 but promote iNKT-mediated anti-leukemia response.97 Interestingly, in a recent study low doses of αGC and β-mannosylceramide acted synergistically to modulate iNKT responses in a preclinical tumor model.32 Whether this strategy can suppress GvHD, remains to be determined. Previously, it was shown that lenalidomide, a thalidomide analog enhances αGC-induced iNKT expansion and IFN-γ production in both healthy donors and patients with MM,98 suggesting that combining iNKT ligands with lenalidomide may provide a viable approach to enhance the efficacy of either therapy against human cancer. However, in two separate clinical trials,99,100 treatment with lenalidomide after allogeneic HSCT induced severe GvHD in the MM patients99 and those with advanced MDS or AML.100 Thus, while pharmacological manipulation of iNKTs holds significant promise, it is critical to understand the mechanisms by which these agents modulate various immune cell functions and to ensure that injections of these agonists into cancer patients will not induce anergy or hyper-activation of iNKT or other immune cells.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In conclusion, we document several preclinical and clinical studies that support the development of innovative iNKT-based therapies for the treatment of cancers. Given that several hematological malignancies express CD1d, they can serve as direct targets for iNKT recognition and attack. Furthermore, by virtue of their DC-priming capabilities and robust cytokine production, iNKTs hold great potential to modulate the anti-leukemia effects of other cytolytic effectors and confer protection from infections; advantages not provided by conventional T-cell-based therapies. Importantly, limited polymorphism of the human CD1d gene and lack of CD1d incompatibility between donors and recipients renders transfer of mature iNKTs a more applicable approach than the infusion of conventional T cells. However, rational use of these cells in cancer immunotherapy awaits better understanding of iNKT reconstitution, effector functions and survival properties in humans. Furthermore, given the heterogeneous nature of iNKTs, the challenge remains in understanding how to manipulate the different subsets of human iNKTs to induce favorable clinical response with no or limited adverse side-effects. Thus, future studies to identify the molecular pathways involved in the differentiation of iNKT subsets and their skewing toward specific effector functions as well as their regulation of other immune cells is highly warranted. These studies will hopefully allow us to fully understand and exploit the therapeutic potential of iNKTs for the treatment of cancers or other immune disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, SAS Foundation for Cancer Research and Foerderer Award (RD), and Clinical Immunology Society & Talecris Biotherapeutics (HB) and the National Institutes of Health (RD, HB, KEN). We thank Dr Hariharan Subramanian for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7: 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science 1997; 278: 1626–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4: 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy KC, Maricic I, Khurana A, Smith TR, Halder RC, Kumar V. Involvement of secretory and endosomal compartments in presentation of an exogenous self-glycolipid to type II NKT cells. J Immunol 2008; 180: 2942–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, Kyparissoudis K, Keating R, Pellicci DG et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond KJ, Pelikan SB, Crowe NY, Randle-Barrett E, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M et al. NKT cells are phenotypically and functionally diverse. Eur J Immunol 1999; 29: 3768–3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J Exp Med 2002; 195: 625–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human V(alpha)24 natural killer T cells. J Exp Med 2002; 195: 637–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2007; 25: 297–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das R, Sant’Angelo DB, Nichols KE. Transcriptional control of invariant NKT cell development. Immunol Rev 2010; 238: 195–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuda JL, Zhang Q, Ndonye R, Richardson SK, Howell AR, Gapin L. T-bet concomitantly controls migration, survival, and effector functions during the development of Valpha14i NKT cells. Blood 2006; 107: 2797–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borowski C, Bendelac A. Signaling for NKT cell development: the SAP-FynT connection. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 833–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrara JL, Reddy P. Pathophysiology of graft-versus-host disease. Semin Hematol 2006; 43: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng D, Lewis D, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Lan F, Garcia-Ojeda M, Sibley R et al. Bone marrow NK1.1(−) and NK1.1(+) T cells reciprocally regulate acute graft versus host disease. J Exp Med 1999; 189: 1073–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lan F, Zeng D, Higuchi M, Huie P, Higgins JP, Strober S. Predominance of NK1.1+TCR alpha beta+ or DX5+TCR alpha beta+ T cells in mice conditioned with fractionated lymphoid irradiation protects against graft-versus-host disease: “natural suppressor” cells. J Immunol 2001; 167: 2087–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haraguchi K, Takahashi T, Matsumoto A, Asai T, Kanda Y, Kurokawa M et al. Host-residual invariant NK T cells attenuate graft-versus-host immunity. J Immunol 2005; 175: 1320–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Strober S. Host natural killer T cells induce an interleukin-4-dependent expansion of donor CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells that protects against graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2009; 113: 4458–4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Teo P, Strober S. Host NKT cells can prevent graft-versus-host disease and permit graft antitumor activity after bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol 2007; 178: 6242–6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leveson-Gower DB, Olson JA, Sega EI, Luong RH, Baker J, Zeiser R et al. Low doses of natural killer T cells provide protection from acute graft-versus-host disease via an IL-4-dependent mechanism. Blood 2011; 117: 3220–3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneidawind D, Baker J, Pierini A, Buechele C, Luong RH, Meyer EH et al. Third-party CD4+ invariant natural killer T cells protect from murine GVHD lethality. Blood 2015; 125: 3491–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneidawind D, Pierini A, Alvarez M, Pan Y, Baker J, Buechele C et al. CD4+ invariant natural killer T cells protect from murine GVHD lethality through expansion of donor CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Blood 2014; 124: 3320–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. The role of NKT cells in tumor immunity. Adv Cancer Res 2008; 101: 277–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. The immunoregulatory role of type I and type II NKT cells in cancer and other diseases. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2014; 63: 199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swann JB, Uldrich AP, van Dommelen S, Sharkey J, Murray WK, Godfrey DI et al. Type I natural killer T cells suppress tumors caused by p53 loss in mice. Blood 2009; 113: 6382–6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth MJ, Thia KY, Street SE, Cretney E, Trapani JA, Taniguchi M et al. Differential tumor surveillance by natural killer (NK) and NKT cells. J Exp Med 2000; 191: 661–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowe NY, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A critical role for natural killer T cells in immunosurveillance of methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J Exp Med 2002; 196: 119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakagawa R, Motoki K, Nakamura H, Ueno H, Iijima R, Yamauchi A et al. Antitumor activity of alpha-galactosylceramide, KRN7000, in mice with EL-4 hepatic metastasis and its cytokine production. Oncol Res 1998; 10: 561–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakagawa R, Motoki K, Ueno H, Iijima R, Nakamura H, Kobayashi E et al. Treatment of hepatic metastasis of the colon26 adenocarcinoma with an alpha-galactosylceramide, KRN7000. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 1202–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayakawa Y, Rovero S, Forni G, Smyth MJ. Alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) suppression of chemical- and oncogene-dependent carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 9464–9469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellone M, Ceccon M, Grioni M, Jachetti E, Calcinotto A, Napolitano A et al. iNKT cells control mouse spontaneous carcinoma independently of tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e8646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Konek JJ, Illarionov P, Khursigara DS, Ambrosino E, Izhak L, Castillo BF 2nd et al. Mouse and human iNKT cell agonist beta-mannosylceramide reveals a distinct mechanism of tumor immunity. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 683–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renukaradhya GJ, Khan MA, Vieira M, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Brutkiewicz RR. Type I NKT cells protect (and type II NKT cells suppress) the host’s innate antitumor immune response to a B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2008; 111: 5637–5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuling H, Ruijing X, Li L, Xiang J, Rui Z, Yujuan W et al. EBV-induced human CD8+ NKT cells suppress tumorigenesis by EBV-associated malignancies. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 7935–7944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watarai H, Fujii S, Yamada D, Rybouchkin A, Sakata S, Nagata Y et al. Murine induced pluripotent stem cells can be derived from and differentiate into natural killer T cells. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 2610–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tahir SM, Cheng O, Shaulov A, Koezuka Y, Bubley GJ, Wilson SB et al. Loss of IFN-gamma production by invariant NK T cells in advanced cancer. J Immunol 2001; 167: 4046–4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molling JW, Kolgen W, van der Vliet HJ, Boomsma MF, Kruizenga H, Smorenburg CH et al. Peripheral blood IFN-gamma-secreting Valpha24+Vbeta11 + NKT cell numbers are decreased in cancer patients independent of tumor type or tumor load. Int J Cancer 2005; 116: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoneda K, Morii T, Nieda M, Tsukaguchi N, Amano I, Tanaka H et al. The peripheral blood Valpha24+ NKT cell numbers decrease in patients with haematopoietic malignancy. Leuk Res 2005; 29: 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii S, Dhodapkar KM et al. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med 2003; 197: 1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metelitsa LS, Wu HW, Wang H, Yang Y, Warsi Z, Asgharzadeh S et al. Natural killer T cells infiltrate neuroblastomas expressing the chemokine CCL2. J Exp Med 2004; 199: 1213–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tachibana T, Onodera H, Tsuruyama T, Mori A, Nagayama S, Hiai H et al. Increased intratumor Valpha24-positive natural killer T cells: a prognostic factor for primary colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 7322–7327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneiders FL, de Bruin RC, van den Eertwegh AJ, Scheper RJ, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH et al. Circulating invariant natural killer T-cell numbers predict outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: updated analysis with 10-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 567–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, Peng J, Takaku S, Miyake S et al. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol 2007; 179: 5126–5136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terabe M, Swann J, Ambrosino E, Sinha P, Takaku S, Hayakawa Y et al. A nonclassical non-Valpha14Jalpha18 CD1d-restricted (type II) NKT cell is sufficient for down-regulation of tumor immunosurveillance. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 1627–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smyth MJ, Crowe NY, Godfrey DI. NK cells and NKT cells collaborate in host protection from methylcholanthrene-induced fibrosarcoma. Int Immunol 2001; 13: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swann J, Crowe NY, Hayakawa Y, Godfrey DI, Smyth MJ. Regulation of antitumour immunity by CD1d-restricted NKT cells. Immunol Cell Biol 2004; 82: 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med 2003; 198: 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dao T, Mehal WZ, Crispe IN. IL-18 augments perforin-dependent cytotoxicity of liver NK-T cells. J Immunol 1998; 161: 2217–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawamura T, Takeda K, Mendiratta SK, Kawamura H, Van Kaer L, Yagita H et al. Critical role of NK1+ T cells in IL-12-induced immune responses in vivo. J Immunol 1998; 160: 16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nieda M, Nicol A, Koezuka Y, Kikuchi A, Lapteva N, Tanaka Y et al. TRAIL expression by activated human CD4(+)V alpha 24NKT cells induces in vitro and in vivo apoptosis of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood 2001; 97: 2067–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wingender G, Krebs P, Beutler B, Kronenberg M. Antigen-specific cytotoxicity by invariant NKT cells in vivo is CD95/CD178-dependent and is correlated with antigenic potency. J Immunol 2010; 185: 2721–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bassiri H, Das R, Guan P, Barrett DM, Brennan PJ, Banerjee PP et al. iNKT cell cytotoxic responses control T-lymphoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2: 59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Sato H et al. Natural killer-like nonspecific tumor cell lysis mediated by specific ligand-activated Valpha14 NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 5690–5693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawano T, Nakayama T, Kamada N, Kaneko Y, Harada M, Ogura N et al. Antitumor cytotoxicity mediated by ligand-activated human V alpha24 NKT cells. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 5102–5105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Das R, Bassiri H, Guan P, Wiener S, Banerjee PP, Zhong MC et al. The adaptor molecule SAP plays essential roles during invariant NKT cell cytotoxicity and lytic synapse formation. Blood 2013; 121: 3386–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dellabona P, Casorati G, de Lalla C, Montagna D, Locatelli F. On the use of donor-derived iNKT cells for adoptive immunotherapy to prevent leukemia recurrence in pediatric recipients of HLA haploidentical HSCT for hematological malignancies. Clin Immunol 2011; 140: 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuylenstierna C, Bjorkstrom NK, Andersson SK, Sahlstrom P, Bosnjak L, Paquin-Proulx D et al. NKG2D performs two functions in invariant NKT cells: direct TCR-independent activation of NK-like cytolysis and co-stimulation of activation by CD1d. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41: 1913–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, Engell K, Wu HW, Sposto R et al. Valpha24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 1524–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu D, Song L, Wei J, Courtney AN, Gao X, Marinova E et al. IL-15 protects NKT cells from inhibition by tumor-associated macrophages and enhances antimetastatic activity. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 2221–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation and cancer. Cell 2010; 140: 883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Santo C, Salio M, Masri SH, Lee LY, Dong T, Speak AO et al. Invariant NKT cells reduce the immunosuppressive activity of influenza A virus-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice and humans. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 4036–4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Santo C, Arscott R, Booth S, Karydis I, Jones M, Asher R et al. Invariant NKT cells modulate the suppressive activity of IL-10-secreting neutrophils differentiated with serum amyloid A. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giaccone G, Punt CJ, Ando Y, Ruijter R, Nishi N, Peters M et al. A phase I study of the natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kunii N, Horiguchi S, Motohashi S, Yamamoto H, Ueno N, Yamamoto S et al. Combination therapy of in vitro-expanded natural killer T cells and alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells in patients with recurrent head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang DH, Osman K, Connolly J, Kukreja A, Krasovsky J, Pack M et al. Sustained expansion of NKT cells and antigen-specific T cells after injection of alpha-galactosyl-ceramide loaded mature dendritic cells in cancer patients. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 1503–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ishikawa A, Motohashi S, Ishikawa E, Fuchida H, Higashino K, Otsuji M et al. A phase I study of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000)-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 1910–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Motohashi S, Nagato K, Kunii N, Yamamoto H, Yamasaki K, Okita K et al. A phase I-II study of alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed IL-2/GM-CSF-cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunol 2009; 182: 2492–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. The contrasting roles of NKT cells in tumor immunity. Curr Mol Med 2009; 9: 667–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stirnemann K, Romero JF, Baldi L, Robert B, Cesson V, Besra GS et al. Sustained activation and tumor targeting of NKT cells using a CD1d-anti-HER2-scFv fusion protein induce antitumor effects in mice. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 994–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heczey A, Liu D, Tian G, Courtney AN, Wei J, Marinova E et al. Invariant NKT cells with chimeric antigen receptor provide a novel platform for safe and effective cancer immunotherapy. Blood 2014; 124: 2824–2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schneidawind D, Pierini A, Negrin RS. Regulatory T cells and natural killer T cells for modulation of GVHD following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2013; 122: 3116–3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lan F, Zeng D, Higuchi M, Higgins JP, Strober S. Host conditioning with total lymphoid irradiation and antithymocyte globulin prevents graft-versus-host disease: the role of CD1-reactive natural killer T cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2003; 9: 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ellison CA, Taniguchi M, Fischer JM, Hayglass KT, Gartner JG. Graft-versus-host disease in recipients of grafts from natural killer T cell-deficient (Jalpha281 (−/−)) donors. Immunology 2006; 119: 338–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim JH, Choi EY, Chung DH. Donor bone marrow type II (non-Valpha14Jalpha18 CD1d-restricted) NKT cells suppress graft-versus-host disease by producing IFN-gamma and IL-4. J Immunol 2007; 179: 6579–6587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang D, Yu Y, Haarberg K, Fu J, Kaosaard K, Nagaraj S et al. Dynamic change and impact of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in mice. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013; 19: 692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Negrin RS. Role of regulatory T cell populations in controlling graft versus host disease. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2011; 24: 453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kohrt HE, Pillai AB, Lowsky R, Strober S. NKT cells, Treg, and their interactions in bone marrow transplantation. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40: 1862–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lowsky R, Takahashi T, Liu YP, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Grumet FC, Shizuru JA et al. Protective conditioning for acute graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kohrt HE, Turnbull BB, Heydari K, Shizuru JA, Laport GG, Miklos DB et al. TLI and ATG conditioning with low risk of graft-versus-host disease retains antitumor reactions after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Blood 2009; 114: 1099–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haraguchi K, Takahashi T, Hiruma K, Kanda Y, Tanaka Y, Ogawa S et al. Recovery of Valpha24+ NKT cells after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004; 34: 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rubio MT, Moreira-Teixeira L, Bachy E, Bouillie M, Milpied P, Coman T et al. Early posttransplantation donor-derived invariant natural killer T-cell recovery predicts the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease and overall survival. Blood 2012; 120: 2144–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chaidos A, Patterson S, Szydlo R, Chaudhry MS, Dazzi F, Kanfer E et al. Graft invariant natural killer T-cell dose predicts risk of acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2012; 119: 5030–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Lalla C, Rinaldi A, Montagna D, Azzimonti L, Bernardo ME, Sangalli LM et al. Invariant NKT cell reconstitution in pediatric leukemia patients given HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation defines distinct CD4+ and CD4− subset dynamics and correlates with remission state. J Immunol 2011; 186: 4490–4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rogers PR, Matsumoto A, Naidenko O, Kronenberg M, Mikayama T, Kato S. Expansion of human Valpha24+ NKT cells by repeated stimulation with KRN7000. J Immunol Methods 2004; 285: 197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Watarai H, Nakagawa R, Omori-Miyake M, Dashtsoodol N, Taniguchi M. Methods for detection, isolation and culture of mouse and human invariant NKT cells. Nat Protoc 2008; 3: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van der Vliet HJ, Nishi N, Koezuka Y, von Blomberg BM, van den Eertwegh AJ, Porcelli SA et al. Potent expansion of human natural killer T cells using alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000)-loaded monocyte-derived dendritic cells, cultured in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15. J Immunol Methods 2001; 247: 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beziat V, Nguyen S, Exley M, Achour A, Simon T, Chevallier P et al. Shaping of iNKT cell repertoire after unrelated cord blood transplantation. Clin Immunol 2010; 135: 364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Patterson S, Chaidos A, Neville DC, Poggi A, Butters TD, Roberts IA et al. Human invariant NKT cells display alloreactivity instructed by invariant TCR-CD1d interaction and killer Ig receptors. J Immunol 2008; 181: 3268–3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hashimoto D, Asakura S, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Van Kaer L, Liu C et al. Stimulation of host NKT cells by synthetic glycolipid regulates acute graft-versus-host disease by inducing Th2 polarization of donor T cells. J Immunol 2005; 174: 551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kuwatani M, Ikarashi Y, Iizuka A, Kawakami C, Quinn G, Heike Y et al. Modulation of acute graft-versus-host disease and chimerism after adoptive transfer of in vitro-expanded invariant Valpha14 natural killer T cells. Immunol Lett 2006; 106: 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang J, Gao L, Liu Y, Ren Y, Xie R, Fan H et al. Adoptive therapy by transfusing expanded donor murine natural killer T cells can suppress acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Transfusion 2010; 50: 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuns RD, Morris ES, Macdonald KP, Markey KA, Morris HM, Raffelt NC et al. Invariant natural killer T cell-natural killer cell interactions dictate transplantation outcome after alpha-galactosylceramide administration. Blood 2009; 113: 5999–6010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tamura Y, Teng A, Nozawa R, Takamoto-Matsui Y, Ishii Y. Characterization of the immature dendritic cells and cytotoxic cells both expanded after activation of invariant NKT cells with alpha-galactosylceramide in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008; 369: 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ishii Y, Nozawa R, Takamoto-Matsui Y, Teng A, Katagiri-Matsumura H, Nishikawa H et al. Alpha-galactosylceramide-driven immunotherapy for allergy. Front Biosci 2008; 13: 6214–6228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Duramad O, Laysang A, Li J, Ishii Y, Namikawa R. Pharmacologic expansion of donor-derived, naturally occurring CD4(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells reduces acute graft-versus-host disease lethality without abrogating the graft-versus-leukemia effect in murine models. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17: 1154–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.MacDonald KP, Rowe V, Filippich C, Thomas R, Clouston AD, Welply JK et al. Donor pretreatment with progenipoietin-1 is superior to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in preventing graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2003; 101: 2033–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morris ES, MacDonald KP, Rowe V, Banovic T, Kuns RD, Don AL et al. NKT cell-dependent leukemia eradication following stem cell mobilization with potent G-CSF analogs. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 3093–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang DH, Liu N, Klimek V, Hassoun H, Mazumder A, Nimer SD et al. Enhancement of ligand-dependent activation of human natural killer T cells by lenalidomide: therapeutic implications. Blood 2006; 108: 618–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kneppers E, van der Holt B, Kersten MJ, Zweegman S, Meijer E, Huls G et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma is not feasible: results of the HOVON 76 trial. Blood 2011; 118: 2413–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sockel K, Bornhaeuser M, Mischak-Weissinger E, Trenschel R, Wermke M, Unzicker C et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after allogeneic HSCT seems to trigger acute graft-versus-host disease in patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukemia and del(5q): results of the LENAMAINT trial. Haematologica 2012; 97: e34–e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]